Introduction

Over the past several years, an increasing number of studies have observed an increase in individual firm lobbying and a relative decline in business associational lobbying in the European Union (EU). What explains this observation? Why are firms on the rise in EU lobbying and associations in decline? Existing works on the politics of interest representation in the EU have largely overlooked this important question.Footnote 1 The literature seeking to explain the construction and development of interest group communities has not focused on explaining the increasing role of firms.Footnote 2 What is more, micro-level studies on firm lobbying in the EU have focused almost exclusively on individual firms’ lobbying behavior—namely, whether and under what conditions they lobby alone or do not lobby—without comparing it to associational lobbying.Footnote 3

The relative neglect of the question why firms have become more politically active vis-à-vis business associations in Europe is surprising for at least two reasons. First, we know that firms play a key role within EU lobbying communities since they are now the most active lobby organizations, estimated to constitute more than 40 percent of all lobby activity in Europe.Footnote 4 Moreover, their relative weight has been consistently growing over the past ten years, at the expense of business associational lobbying,Footnote 5 mirroring dynamics that have been observed within EU countries,Footnote 6 in the United States,Footnote 7 and in international political systems such as the World Trade Organization.Footnote 8

Second, the rise of firms’ direct lobbying efforts, and the concomitant decline of associational lobbying, raises major normative concerns. Business associations tend to moderate the positions of firms with a keen eye on long-term stability and focus on the broader business community, while firms may be more inclined to defend narrow and self-oriented interests that are key for survival of their business.Footnote 9 Existing empirical work supports earlier concerns that these dynamics may end up reinforcing political systems’ tendency to develop policies that are collectively inefficient.Footnote 10 For instance, by engaging in direct lobbying, US firms have been able to obtain greater regulatory leniency,Footnote 11 lower effective tax rates,Footnote 12 and higher than average profitsFootnote 13 and financial performance.Footnote 14 Moving to the EU context, Chalmers and Macedo similarly find that the more firms spend on lobbying, the more policy returns on this investment they get.Footnote 15

Therefore, we seek to fill the gap in the literature by advancing an explanation that stresses how economic globalization stimulates firms’ direct lobbying at the expense of associational lobbying in the EU. To do so, we build on earlier works regarding firms’ motives to engage in direct lobbying by the degree of conflict or disagreement that exists between firms over a certain policy issue.Footnote 16 These works’ underlying logic is plausible and straightforward: interfirm disagreements over the merits of policies make it more difficult for business associations to find common ground that satisfies all firms, which should, in turn, incentivize firms to rely on direct, rather than associational, lobbying. Inspired by these works, we advance an argument that views economic globalization as a key underlying root cause of the interfirm disagreements that are found to motivate firms to rely on direct, rather than associational, lobbying in the EU.

We advance an original argument that stresses how economic globalization stimulates firm-level lobbying at three different levels. First, we demonstrate that the relative shares of direct firm lobbying and business associational lobbying vary across sectors: the more globalized economic sectors—that is, the sectors with higher levels of multinational corporations (MNC) activity—exhibit higher levels of direct lobbying by firms. Second, at the country level, we show that there is substantial variation in the extent to which firms lobby directly or through business associations: firms originating in countries that are more deeply integrated into the global economy through trade and investment ties display higher levels of firm-level lobbying. Third, we show that there is much variation in firm versus associational lobbying depending on the geographical origin of these organizations: firms from outside the EU engage in direct lobbying more often than firms operating within the EU. Combined, our arguments and findings underscore that increased economic globalization contributes to systematically increasing individual firm lobbying within the EU, and hence to a fracturing of the EU's system of interest representation.

The article proceeds as follows: First, we take stock of the state of the art of existing work on firm-level lobbying in the EU to define the landscape of the scholarship within which our contribution is situated. Second, we develop our argument by specifying the mechanisms linking globalization with firm-level lobbying at the country, sector, and firm levels. Third, we subject our arguments to empirical scrutiny using on an original dataset of lobbying contacts between interest organizations and European Commission (EC) officials. This dataset covers almost 14,000 lobby contacts between interest groups and EC senior staff, allowing for a rigorous test to explain variation in individual firm and associational lobbying. We conclude by summarizing the findings of the article, acknowledging the limitations of our contribution, and suggesting avenues for further research.

State of the art

Studies of the construction and development of interest group populations have a long history. Already in the 1980s, American scholars had constructed samples of US interest group populations, noting a sharp skewedness toward business interests.Footnote 17 This scholarly field became even more central with the pioneering work of Gray and Lowery,Footnote 18 which sought to explain the development of American interest group populations from a population ecological perspective. This research agenda spilled over to Europe and spurred many students to map and explain interest group community dynamics across EU institutional contexts.Footnote 19

In the EU specifically, because of the widespread reliance on definitions of interest groups based on membership characteristics,Footnote 20 most macro-level studies of EU lobbying communities have excluded firms from their analyses. Rather, these studies have focused exclusively on business associational lobbying or on comparisons between business associations and other types of interest groups, in particular NGOs.Footnote 21

However, the few macro-level studies of EU lobbying communities that do include firms within the scope of their investigation observe that firms have become the most active lobby organizations in Europe.Footnote 22 For instance, Berkhout et al. compare three sources to map the EU interest group populations.Footnote 23 The authors find that firms constitute 30 to 40 percent of the interest group organizations in the EU, depending on the source used. Moreover, Hanegraaff and Poletti take a longitudinal perspective and show that over the past ten years, the EU has witnessed an estimated growth of 16 percentage points in individual firm lobbying (from 26 percent in 2008 to 41 percent in 2018), while business associational lobbying has decreased (from 49 percent to 33 percent) during the same period.Footnote 24 Surprisingly, however, none of these studies have asked why firms are increasingly populating interest group communities in the EU.

Similarly, existing micro-level studies focused on the political activity of firms in the EU have also largely overlooked this question. For instance, Bernhagen and Mitchell,Footnote 25 who rely on Forbes Global 2000 firm data, and Dellis and Sondermann,Footnote 26 who rely on EC Transparency Register data combined with the AMADEUS database, are the two most prominent studies to date in the EU. Their findings suggest that larger and more productive firms, as well as firms that are more exposed to government use of either coercive powers or distributive policies, are more likely to lobby in the EU. Yet, because these works have focused exclusively on individual firms’ lobbying behavior—that is, whether they lobby alone or do not lobby—they remain silent about the motives driving firms’ decision to lobby alone rather than through business associations. To put it differently, we have explanations for why some firms lobby alone and others do not, but why firms have become the most dominant lobby organizations in the EU, at the expense of associations, remains unanswered.

In the next section, we develop an argument that specifies how globalization affects lobbying patterns in the EU by stimulating firms to lobby alone rather than through business associations.

The argument

In order to develop our argument, we build on scholarly work that has examined firms’ motives to explore interest representation beyond the business association and engage in direct lobbying. These studies contend that firms’ decision to lobby alone, rather than doing so through a business association, is ultimately a function of the degree of conflict or disagreement that exists between firms over a certain policy issue.Footnote 27 The argument is straightforward: interfirm disagreement over the merits of policies makes it more difficult for business associations to find common ground that satisfies all firms, which should, in turn, incentivize firms to rely on direct lobbying. Business associations seek to balance the policy preferences of their members and develop an acceptable lobby strategy which is representative of the wishes of most their members.Footnote 28 This effort becomes easier when there is little disagreement among members about the desired policy outcomes. If, however, members disagree strongly about the direction of policies, it will become increasingly difficult for associations to represent all members and keep them satisfied.

Moreover, because of the internationalization and liberalization of markets, corporations may see less need to realize their interests through business associations.Footnote 29 That is, these trends force corporations to focus on the realization of self-interest,Footnote 30 rather than principles of cooperation through associations and can put strain on the relationships between corporations and their business associations.Footnote 31 Should interest associations find themselves unable to adapt to such changes and sufficiently represent the interests of their members, corporations have the option to “exit”Footnote 32 and realize interest representation through other modes, such as going alone.

While this line of argumentation is eminently plausible, it begs the obvious question of under what conditions we should expect the degree of interfirm conflict or disagreement over the merits of policies likely to be high or low. Inspired by these works, we advance an argument that views globalization as a key underlying root cause of interfirm disagreements that motivate firms to rely on direct, rather than associational, lobbying in the EU. In line with Drezner, we define globalization as “the cluster of technological, economic and political innovations that have drastically reduced barriers to economic, political, and cultural exchanges.”Footnote 33 In our view, globalization has systematically increased interfirm policy preference heterogeneity, which, in turn, translates into higher incentives for firms to lobby alone rather than to rely on business associational lobbying. As we explain in the rest of this section, this should be true at the sector, country, and firm levels.

First, we expect that the more globalized economic sectors—that is, the sectors with higher levels of MNC activity—should exhibit higher levels of firms’ direct lobbying. To develop our argument, we rely on the logic that underpins the “new” new trade theory (NNTT), also known as heterogeneous firm theory. Building on the seminal work of Melitz (Reference Melitz2003), a wide array of political-economy works have shown how global market integration generates stark distributional conflicts between firms operating in the same sector.Footnote 34 In a nutshell, NNTT posits, and offers evidence to show, that only a subset of firms within in a sector reap the lion's share of the gains stemming from global market integration: the benefits of trade opening accrue only to the largest and most productive firms, while middle- and low-productivity firms decrease their sales or are forced to exit the market altogether. This approach challenges the conventional wisdom that market opening engenders distributional consequences of running along industryFootnote 35 and, in doing so, provides a theoretical foundation to account for varying patterns of firm-centric lobbying. If firms’ fortunes are no longer tied to the sector in which they operate, interfirm disagreements over the merits of trade policies are likely to increase, which, in turn, makes it more difficult for sectoral associations to coherently represent their interests and incentivizes firms to lobby on their own.

Drawing on these theoretical insights, we derive the expectation that direct firm lobbying should be higher in EU economic sectors displaying higher levels of MNC activity. MNCs represent one of the key economic drivers of processes of global market integration, particularly within global value chains. MNCs integrate various production lines across countries into a coherent corporate structure. This includes “vertical integration,” whereby firms own certain supply chain partners and internalize the production of parts and components, and “horizontal integration,” through which global firms copy the entire production process, but at different locations.Footnote 36 In the EU, MNCs have grown in importance over time. Many of them have organized production within the boundaries of the EU, while others have established production networks that have a global reach. For instance, EU MNCs in 2014 received the largest amount of income from foreign activities of partner enterprises operating under their corporate structure, standing at USD 7.5 trillion in output and taking up half the entire OECD share.Footnote 37

There are good reasons to expect the degree of policy-related conflict or disagreement across firms to be higher in the EU economic sectors that are characterized by high levels of MNC activity. To begin with, such an expectation is coherent with the logic underpinning NNTT. Indeed, MNCs are usually the largest and most productive firms within a given industry.Footnote 38 This is so because the managerial capacity and resources required to undertake the construction of an effective global production network are available only to the largest and most productive firms.Footnote 39

In line with NNTT's intuition that differences in productivity across firms drive intra-industry preference heterogeneity, it is therefore plausible to expect that the degree of interfirm disagreements over the merits of policies within a given sector should become more prominent as the number of MNCs operating within a sector increases. The political-economy literature provides strong support for this view, showing that MNCs hold starkly different policy preferences than domestic firms operating in the same sector across a wide range of policy areas. For instance, many studies have documented this preference heterogeneity with respect to several trade policy and trade-related regulatory issues.Footnote 40 However, these observations extend to other policy areas as well. For instance, Atikcan and Chalmers show that firms’ preferences on the adoption of the General Data Protection Regulation of the EU varied depending on the degree of internationalization of their activities.Footnote 41 Similarly, Van den Broek carried out an analysis of 43 directives and 27 regulations across 112 policy issues in the EU and showed that MNC signatories to the United Nations Global Compact held policy preferences that were consistently different from those of other firms.Footnote 42

And it is important to note that, in addition to being more likely to hold policy preferences that diverge from those of domestic firms operating in the same sector, MNCs are also more likely to dispose of the necessary resources to engage in direct lobbying. Indeed, the findings of the literature on firms’’ direct lobbying, in both the United States and the EU, consistently show that more resourceful firms such as MNCs—that is, larger and more competitive ones—are more likely to engage in individual lobbying.Footnote 43

In this context, it is important to make a distinction between MNCs that have organized production within the boundaries of the EU and those that have established production networks outside of it. We expect that the degree of conflict or disagreement over the merits of policies across firms should be higher in the latter case, because MNCs in the former case operate within a single market with a common external tariff and largely uniform regulatory burdens and therefore should have preferences that are similar, if not identical, to those of domestic firms that have not internationalized production. Altogether, these arguments lead us to formulate the following hypothesis:

H1: Economic sectors displaying higher levels of MNC activity outside the EU are more likely to display higher levels of direct lobbying, compared to associational lobbying.

Second, we expect that the relative share of firms’ direct lobbying should be higher if the firm's country of origin is more globalized—that is, it is more deeply integrated into the global economy through trade and investment ties. In making our case, we broadly extend to the level of countries as a whole, following the logic of the arguments developed previously, and include additional elements for consideration. As the degree of integration of an EU member state's economy into the global market increases, we expect that there will be more sectors characterized by stark internal divisions between different firms’ policy preferences, which should, in turn, translate into a higher degree of interfirm preference heterogeneity in the country as a whole. Indeed, the increasingly diverging preferences of firms with regard to trade and regulatory policies at the level of sectors should reverberate at the country level: the more a country is integrated into the global economy, the more sectors will display interfirm preference heterogeneity, and the more the relative share of firms’ direct lobbying will be observable in that country.

But a country's integration into the global economy does not simply foster firms’ direct lobbying as a result of this logic of reverberation of sectoral processes into national systems of interest representation. There is also a direct effect linking the level of globalization of an economy and patterns of firms’ lobbying. Broadly speaking, global market integration implies that more firms that previously operated exclusively in EU member states’ domestic markets have become entangled in complex trading, production, and investment relationships with the rest of the world. Moreover, it means that, in addition to many EU firms investing abroad to locate part of their production in low-cost countries, a growing number of foreign investors have a presence in EU companies. The more a country is entangled in these complex webs of production, distribution, investments, and trade, the more we can expect firms’ preferences to diverge not only with respect to policy choices that directly affect their sectoral interests, but also with their country's core macroeconomic policy choices with cross-sectoral implications.

Traditionally, firms have channeled their preferences on such core macroeconomic policy choices by lobbying through industry-wide organizations, which have often been instrumental to the creation of the cross-sector business alliances needed to weigh on choices with direct country-wide, cross-sectoral effects. The presence of institutional mechanisms enabling coordination among the key stakeholders in the domestic political-economy certainly plays a role in shaping firms’ ability to engage in such forms of coordinated lobbying.Footnote 44 But such an ability is also affected by the degree of preference heterogeneity that exists between firms operating in the economy. The globalization of a country's economy, therefore, has a direct bearing on the extent to which firms’ preferences diverge with respect to policy issues that have a broad, cross-sectoral scope. Existing works support this view, showing that, indeed, the globalization of a country's economy—that is, the increase of its trade and investment ties with the rest of world—systematically increases the degree of interfirm preference heterogeneity with respect to countries’ core macroeconomic policy choices, such as fiscal,Footnote 45 monetary,Footnote 46 financial,Footnote 47 and investment and industrialFootnote 48 policies. The implication of this line of argument is that the increase in the level of globalization of an economy should go hand in hand with an increase in the level of interfirm preference heterogeneity both within and across sectors. Both sets of arguments lead us to formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: Countries that are more globalized are more likely to display higher levels of direct lobbying, compared to associational lobbying.

Finally, we expect to observe significant differences in the propensity to engage in direct, rather than associational, lobbying depending on whether a firm geographically originates in the EU or not. As shown by Rasmussen and Alexandrova, many interest groups that are active in Brussels stem from non-EU countries, including many firms and business associations.Footnote 49 The growing presence of non-EU interest groups within the EU lobbying community is a phenomenon that is clearly connected to the increased level of globalization of the EU's economy. Such a process has been driven both by European firms’ decision to internationalize their production and by an increased presence of foreign firms investing and producing directly in the EU or trading with EU firms. In addition to changing the lobbying incentives for EU firms that we have discussed so far, the globalization of the EU's economy has also brought about stronger incentives for non-EU firms to try to influence EU policies that increasingly have a direct bearing on their activities. Indeed, the growing presence of non-EU firms in the EU market implies policy decisions adopted by the EU, more or less directly, affect an increasing number of firms located in foreign countries.

We develop the expectation that non-EU firms should be more likely to engage in direct lobbying than EU firms. Our starting point is the work of Bernhagen and Mitchell, who found that non-EU firms engage in direct lobbying more than EU firms because they cannot easily trust the governments of EU member states to defend their interests across European institutions.Footnote 50 A similar logic can be used to address the question of whether firms may opt to lobby by themselves. Non-EU firms not only do not dispose of a government patron, they also cannot rely on the option of pursuing interest representation through national business associations. Therefore, we should expect that for firms that cannot rely on national channels of interest representation, their likelihood of engaging in direct lobbying should be higher.

Moreover, again, since the resources required to commence the construction of an effective global production network are available only to the largest and most productive firms,Footnote 51 it seems reasonable to expect that non-EU firms that are able to operate in the EU market are usually very large and very productive firms. Many studies underscore that size and productivity correlate positively with the probability of direct lobbying,Footnote 52 which suggests that non-EU firms are likely to dispose of sufficient amounts of resources to devote to lobbying. Hence, firms originating outside the EU not only cannot rely on national channels of interest representation, they also tend to dispose of a large degree of resources to lobby directly with a view toward achieving preferred policies in the EU. This leads us to formulate the final hypothesis:

H3: Non-EU firms are more likely to engage in direct lobbying, compared to associational lobbying.

Research design

To test our hypotheses, we rely on a database of lobbying contacts across interest organizations and senior staff of the European Commission between 2014 and 2019. The data is stored at the EU Transparency Portal, but it is not easily retrievable. However, Lobbyfacts (a website hosted by the Corporate Europe Observatory and LobbyControl) made the data available in a format that is easily accessible, and we rely on this input. In total, the database consists of 22,000 contacts between EC senior staff and interest group staff across firms, business associations, and NGOs.

The data consists of a reference to the concerning organization and the name and affiliation of the Directorate-General (DG) staff. This comprehensive dataset provides a unique insight into the lobby contacts between DG staff and various types of interest organizations. We coded all organizations based on their group type, distinguishing between business organizations, NGOs, and labor unions.Footnote 53 In this article, we focus only on business organizations, making a distinction between for-profit firms and not-for-profit business associations, which are associations that have firms as members. In total, there are 13,928 organizations in our dataset, of which 7,6378 are firms and 6,290 are business associations.

We matched each of these organizations to a particular economic sector, relying on the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) Revision 4 codes. More specifically, we coded organizations at the ISIC two-digit level. For instance, this includes—in no particular order—sectors such as fishing and aquaculture (code 03), extraction of crude petroleum and natural gas (06), manufacture of basic metals (24), construction of buildings (41), telecommunication (61), and advertising and market research (73). The two-digit ISIC codes serve to identify variation across economic sectors in how the firms are integrated into GVCs. It is important to mention that firms can be active in more than one sector. We dealt with this in the following way: if firms are active in more sectors listed in two-, three-, or four-digit ISIC codes, we coded these one level higher—that is, at the two-digit code or the industry code (e.g., C = manufacturing). Finally, organizations that are very broadly organized, such as BusinessEurope, could not be linked to one particular sector. These types of organizations were excluded from the analyses. It is important to note that this applies to only 8.4 percent of the population.

Our dependent variable is operationalized as whether an individual firm or a business association has interacted with EC staff; therefore, it is measured as a binary variable. As this is a dichotomous dependent variable, logistic regression statistical models are employed in the analysis (see empirical section for more details on the statistical models).

The model included in the study has three main independent variables. First, we rely on aggregate firm-level data from the Orbis database provided by Bureau Van Dijk to capture a sector's degree of economic globalization. We checked whether firms are active in jurisdictions outside the EU based on the geocodes of branches and subsidiaries, and if so, we treated these firms as MNCs. We then counted the number of MNCs in each two-digit ISIC sector and divided by the total number of firms in this sector. Second, we rely on the most widely used indicator for economic globalization across countries to capture a country's degree of economic globalization: the KOF Globalization Index, focusing specifically on the indicator for economic globalization.Footnote 54, Footnote 55 Third, we distinguish between firms that have their headquarters in the EU and firms that do not: 11,536 organizations have their headquarters in the EU and 2,392 organizations are located outside the EU.

The study controls for various potential confounders. To start with, at the country level, we control for the size of the country's economy (Marshall & Bernhagen Reference Marshall and Bernhagen2017), since countries with a large gross domestic product (GDP) such as Germany or France tend to have larger interest communities active in the EU. We rely on data provided by the OECD. Moreover, we single out Brussels as a headquarters location, as many associations have a Brussels office, while a larger share of the firms do not. We did not want this to interfere with the results, so we added a dummy for the organizations that have a Brussels office. Moreover, as the EC is located in Brussels, it makes sense that organizations that have a Brussel office lobby the EC more frequently, an effect for which we want to control. In total, 4,221 organizations have a headquarters in Brussels and 9,707 organizations had their headquarters in another country.

At the sector level, we control for the size of an economic sector because the extant literature suggests that this is one of the most important factors driving firms’ direct lobbying.Footnote 56 To do so, we rely on the added value of a sector from the TiVA database. Second, we account for market concentration by adding the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) of market concentration to the regression model. This way, we control for the possibility that our results are (only) driven by market structure and firm size rather than global engagement. For each two-digit ISIC sector, we calculated the HHI based on turnover data from more than 200,000 firms active in the EU. Data come from Orbis.Footnote 57 Third, we use the World Input-Output Database (WIOD) to measure the sectors’ reliance on foreign inputs in the production process (Timmer et al., 2015). More specifically, for each EU member state, we take the sectoral consumption of foreign (i.e., extra-EU) intermediate inputs, sum across all member states, and calculate the sectors’ foreign intermediate consumption as a percentage of their total output in the EU.Footnote 58

Finally, we control for variation across Directorates-Generals. It may be that there are varying incentives provided by different DGs for firms to start lobbying. This may be the capacity of the DG to interact with more (or a larger variety of) interest groups. It may also be that firms are triggered by the attention of actors, such as NGOs targeting a particular DG. Such effects are independent of the economic sectors in which firms and associations operate, and therefore we want to control for them. First, we control for the size of different DGs (see Berkhout et al. Reference Berkhout, Carroll, Braun, Chalmers, Destrooper, Lowery and Rasmussen2015). To do so, we use the number of staff working at each DG, drawing on data collected by the DG Human Resources and Security. More precisely, we rely on the statistical bulletin that summarizes the personnel of the ’EC. We also control for the overall competition for attention by policymakers. On the one hand, we include the overall density of groups active in a DG, using a simple count of organizations that have had contact with EC staff at a particular DG. On the other hand, we control for the salience of a particular DG, since individual firms may shy away from engaging in direct lobbying when DGs are subject to intense public scrutiny. We rely on a proxy for this, namely the share of NGOs lobbying in each DG, since NGOs disproportionally lobby on issues that attract much media attention

Empirical analysis

Before we systematically test our hypotheses, we first present some descriptive statistics to illustrate the variation in firm and associational lobbying in the EU. Overall, our dataset consists of 11,894 business organizations that were in contact with personnel working at any of the DGs between 2015 and 2019. Of this group, 5,769 are associations and 6,125 are firms. This means that over 53 percent of the business organizations that have lobbied senior EC staff are firms, while roughly 47 percent are associations.

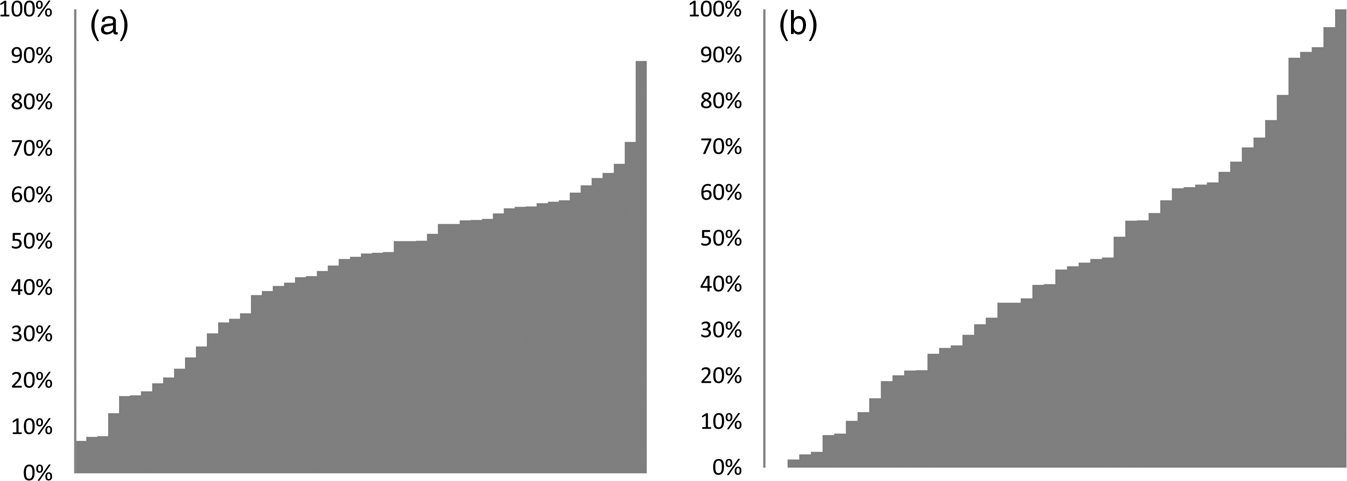

Of all the DGs, the DG for Digital Economy and Society was lobbied the most. No fewer than 2,854 of the active organizations lobbied in this venue. The second most lobbied institution was DG GROW (DG for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs), which was targeted by 1,733 organizations during the period we analyzed. The distribution among firms and associations across the various DGs is displayed in Figure 1a, which shows that the relative shares of firms’ direct and associational lobbying vary considerably across DGs. Some DGs are only targeted by associations, while at other DGs, hardly any associations are active.

Figure 1. (a) Share of firms across DGs. (b) Share of firms across sectors.

Note: Figures present the percentages of firms (out of total) that have been active in a DG (left) or operate in certain economic sectors (ISIC codes, right). The results have been sorted in ascending order.

As far as economic sectors are concerned, the energy (1,518), banking (1,376), transportation (1,131), and telecommunication (1,074) sectors account for the majority of contacts between interest groups and EC staff. As in the case of DGs, the relative shares of firms’ contacts vary significantly across sectors. Figure 1b summarizes the results, showing that while some sectors hardly feature any firm contacts (see the left part of figure), in other sectors, they account for the vast majority of contacts between EC staff and interest groups. The sectors featuring the lowest levels of firms’ direct lobbying include the clothing, real estate, advertising and marketing, and agricultural sectors. Those displaying the highest levels of firms’ direct lobbying include the computer and electrical equipment, mining, motor vehicles, and banking sectors. Overall, these descriptive numbers highlight the variation in firm and associational lobbying within the EU.

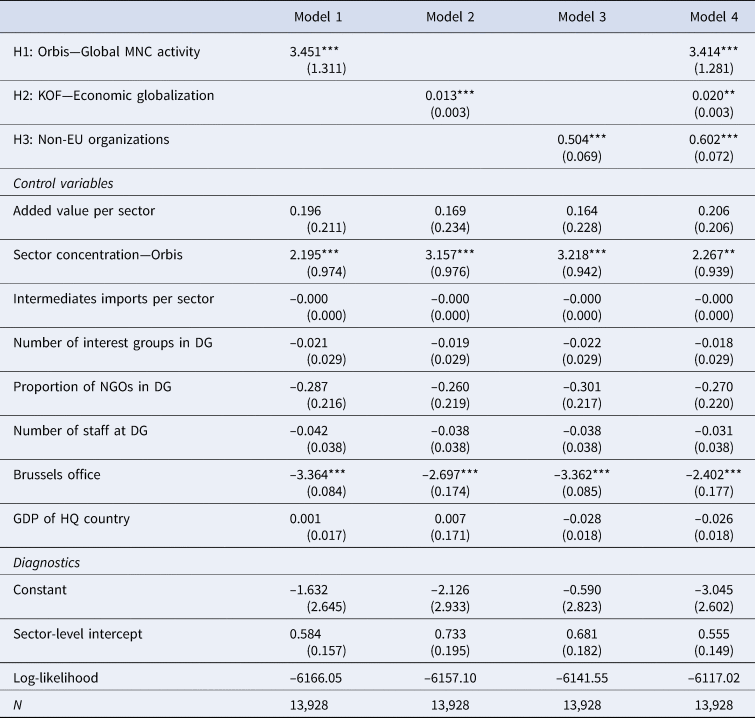

This brings us to the multivariate analysis. More specifically, our explanatory focus is (1) the level of activity of MNCs that have established production networks outside the EU (Orbis); (2) variation across countries in terms of their level of economic globalization (KOF); and (3) whether an organization is foreign (i.e., non-EU). We present four models in which we test the three hypotheses independently of each other, while Model 4 includes all the independent variables. To account for the strong variation in business activity across sectors, we present mixed-effects models at the level of the economic sector. To make sure our results are robust, we run a series of alternative models. First, we use different specifications—namely, a regular logit model (see Appendix 1), a model in which we use fixed effects for sectors (see Appendix 2), and a model in which we rely on fixed effects for the DGs (see Appendix 3). Finally, as we have potential hierarchical data in which sectors can be nested into countries, we also run a multilevel using two levels: sectors nested in countries (see Appendix 4). Each model points to the same results as the main analysis.

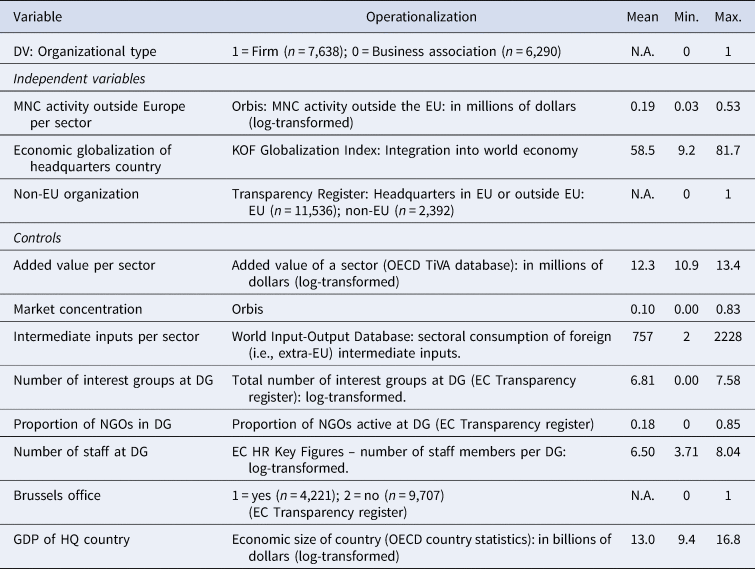

Table 1. Summary table.

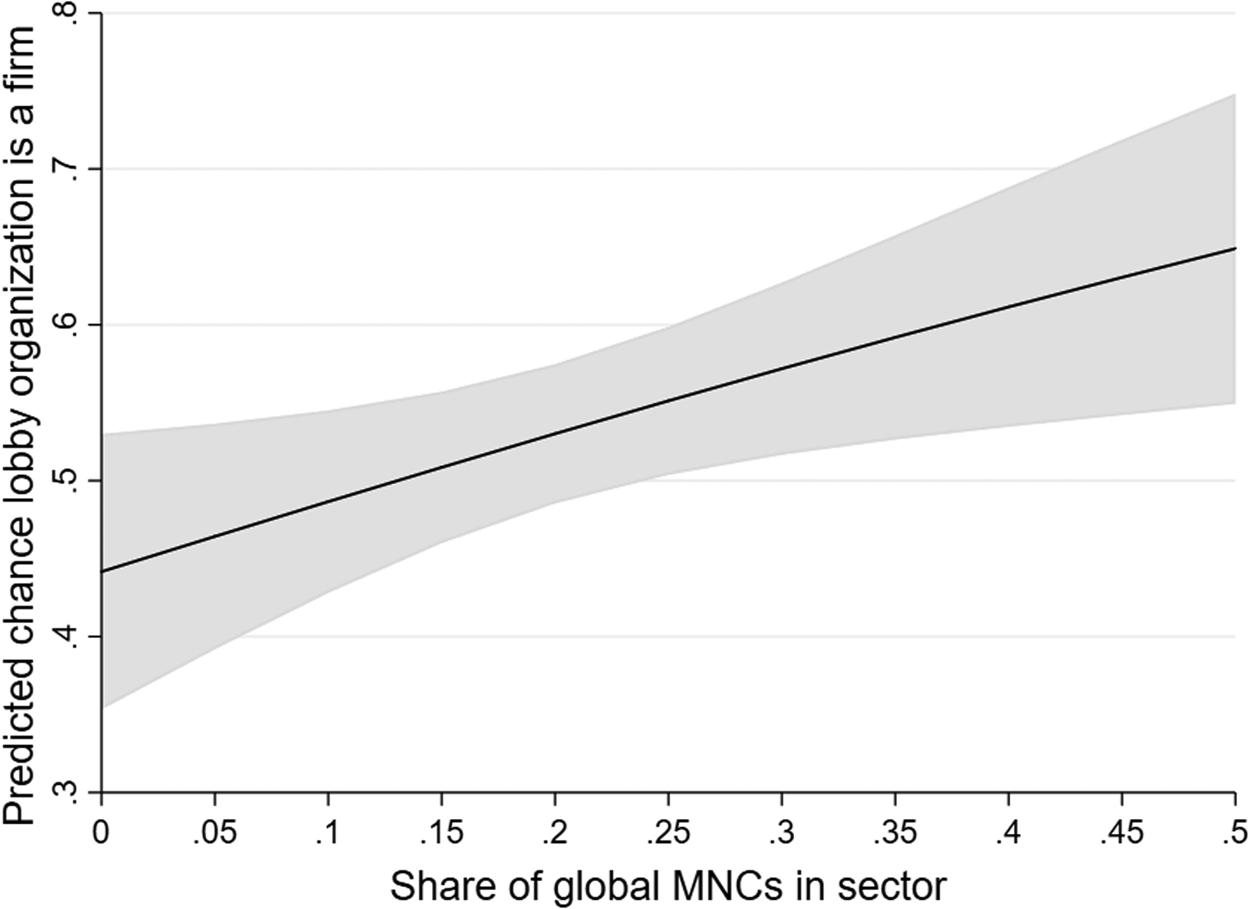

The first part of our discussion focuses on the differences across sectors in levels of activity of MNCs that have established production networks outside the EU. In Model 1 and Model 4 in Table 2, we observe that there is a positive and significant relationship between sectoral MNCs’ global activity and firms’ direct lobbying (p < .001). To grasp the effects more tangibly, we plotted the predicted probabilities for firms’ direct lobbying (y-axis) against various levels of MNCs’ global (extra-EU) turnover (x-axis). Figure 2 clearly supports our second hypothesis, showing that the probability that firms engage in direct lobbying is more than twice as large in the sectors characterized by the highest levels of activity of MNCs that have established production networks outside of the EU compared to the sectors with the lowest level of MNC activity. Again, the effects are quite substantial: in sectors that host limited global MNCs, the predicted share of firms lobbying is around 42 percent. This rises to a predicted share of 65 percent for sectors that include more global MNCs. Overall, this means we find support for H2: the more globalized an economic sector is, the more likely it is that individual firms are lobbying the EC.

Figure 2. Predicted chance that firm or association is lobbying in the EC, by level of global activity by MNCs outside the EU in an economic sector.

Notes: Based on full model (4). A higher score means that the chance of a firm lobbying within a sector in the EC is higher. Significance is presented with alpha = 0.05.

Table 2. Predicted chance that a firm or association is lobbying at the EC.

Notes: The model is a mixed-effects logistic regression that estimates a random intercept for each economic sector. The dependent variable is whether a firm or an association is lobbying the EC. Standard errors are presented in parentheses. Significance: * 0.05; ** 0.01; *** 0.001.

To make sure our results are robust, we also run two additional analyses. First, we use an alternative measure of economic globalization: the OECD's Activity of Multinational Enterprises (AMNE) database. More precise, we rely on the MNCs’ global (extra-EU) turnover per sector. The results are presented in Appendix 5. They remain similar: in more globalized sectors (here based on global turnover by EU MNCs), we see relatively more firm lobbying. Second, our reasoning for this hypothesis is based on the logic that EU-level business associations find it more difficult to represent firms that are active across the globe. This means that we should find an effect only if MNC activity is higher at a global scale, not within the EU. At this level, EU associations still have a strong mandate to represent these organizations. To test whether it is indeed economic globalization, not Europeanization of firm activity, we run a model with only EU-level MNC activity in an economic sector, rather than the global activity of firms (see Appendix 6). The results confirm our reasoning: the effect of the Europeanization of EU firms is not significant. This indicates that economic globalization is indeed the driver of individual firm lobbying, in line with our argument that, for these sectors, EU-level business associations have become less important for firms (in contrast with sectors in which most MNC activity is still in the EU). This further corroborates H2.

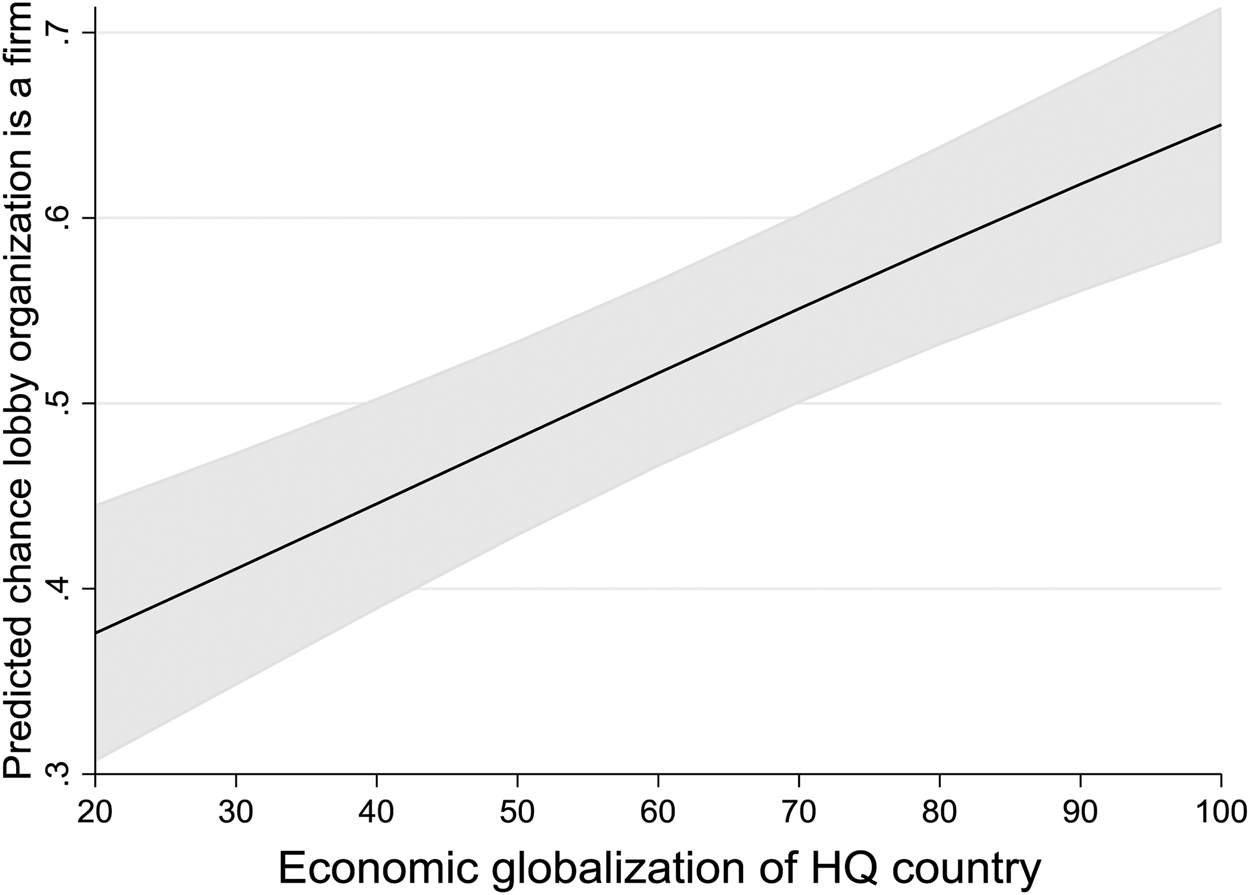

The second part of our analysis focuses on the globalization of countries and its effect on the distribution across firm and associational lobbying. Our hypothesis is that more economically globalized EU member states should display higher probabilities of firm-level lobbying compared to less economically globalized ones. The results are presented in Model 1 and Model 4. Overall, the results confirm our expectations as both the partial and full model yield significant results (p < .000). To visualize the effect, we plot the predicted probability that the observed organization that is lobbying is a firm based on the level of economic globalization of the country in which the headquarters is located (see Figure 3). In Figure 3, we observe a rising predicted line, indicating that more globalized economies display higher levels of individual firm lobbying. The effects are also very substantial as the predicted level of firm lobbying in countries with more limited integration in the world economy is lower than 40 percent, while this rises to well over 65 percent for countries that are more economically globalized. Overall, the results support H1: if organizations originate from countries that are more economically globalized, it is more likely that a firm is lobbying at the EC instead of a business association from this country.

Figure 3. Predicted chance that firm or association is lobbying in the EC, by level of economic globalization of a country.

Notes: Based on full model (4). A higher score means that the chance of a firm lobbying within a sector in the EC is higher. Significance is presented with alpha = 0.05.

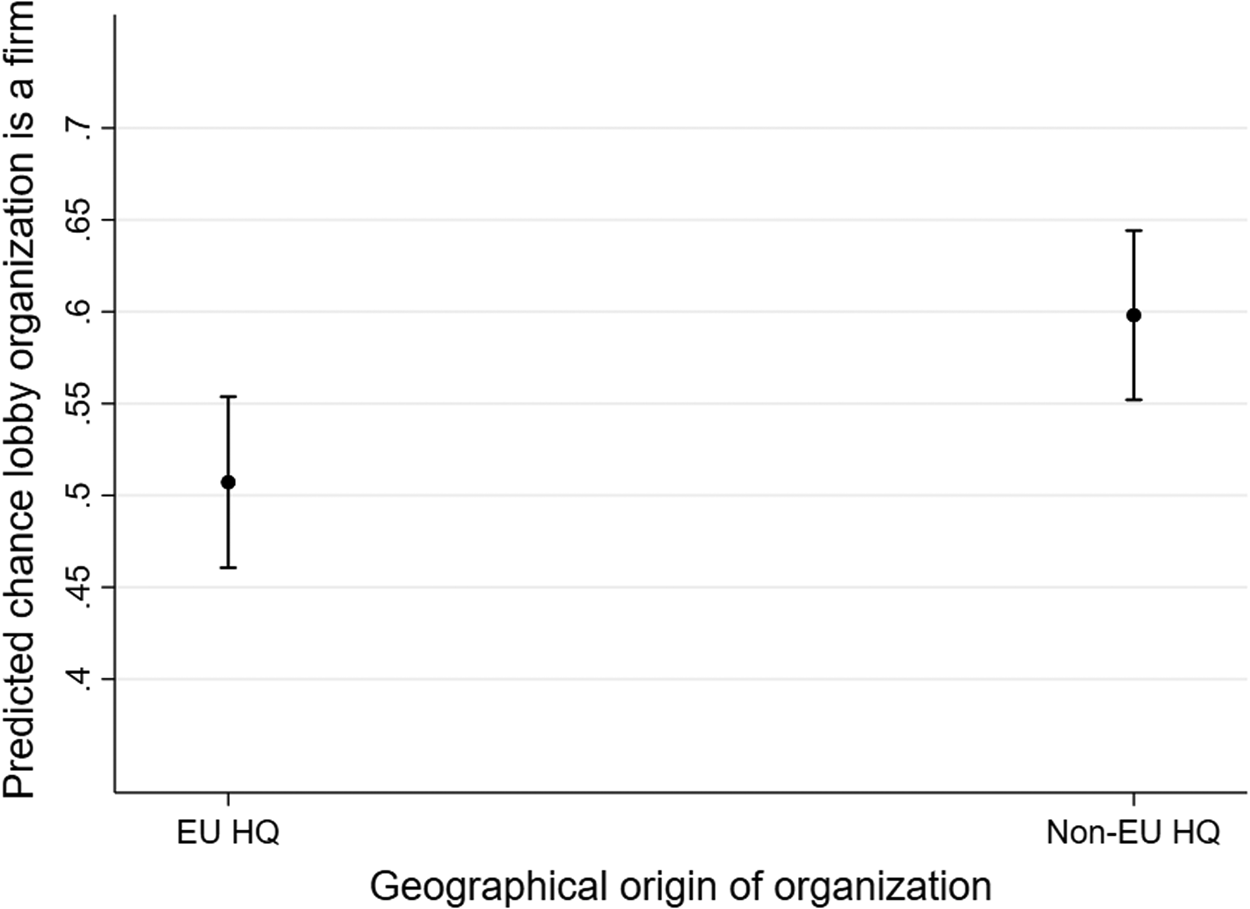

The final section of our analysis focuses on the geographical origin of business organizations that are active in the EU. Our hypothesis is that firms that have a headquarters outside the EU are more likely to lobby themselves compared to firms that have a headquarters in the EU. The results are presented in Model 3 and Model 4. Again, in both models, the correlation coefficient is significant (p < .000). To understand the effect better, we plot the predicted probability that a firm is lobbying based on whether an organization stems from the EU or not. We see that among the non-EU organizations, the predicted share of firms lobbying at the EC is 60 percent. For EU organizations, the predicted share is 50 percent. This, again, supports our reasoning and confirms H3: non-EU firms are more likely to lobby themselves than EU firms.

Figure 4. Predicted chance that firm or association is lobbying in the EC, by geographical origin of headquarters.

Notes: Based on full model (4). A higher score means that the chance of a firm lobbying within a sector in the EC is higher. Significance is presented with alpha = 0.05.

The control variables yield some interesting results. First, and in line with the extant literature, we find that individual firm lobbying trumps associational lobbying in more concentrated sectors.Footnote 59 This makes a lot of sense. If it is true that firms’ direct lobbying is a function of the large resources that MNCs with a global reach dispose of, then their collective action capacity should be even stronger as the size of the sector in which they operate decreases.Footnote 60 Second, we do not find much support for any of the institutional explanations since we find no evidence that the probability of firms’ direct lobbying correlates with factors such as the size of DGs, the overall amount of lobbying in DGs, and the share of NGOs’ activity in DGs. These results are in line with other studies claiming that the economic context is more important than the institutional context when it comes to accounting for the structure of interest group communities.Footnote 61

Conclusion

In this article, we aimed to deepen our knowledge regarding the politics of interest representation in the EU by analyzing the contextual level factors that stimulate firms to start lobbying themselves, either in conjunction with or against business associations. We expected to observe a higher share of firms’ direct lobbying in countries that are more economically globalized, in economic sectors that are more economically globalized, and when organizations outside the EU lobby the EC. Relying on data on lobbying contacts between interest organizations and EC officials, we find support for our argument on all three accounts.

Our findings have important implications. Our study indicates that the rise of firm lobbying in the EU reflects the structural transformation of the EU economy resulting from its growing integration in global markets. These transformations are making it harder for associations to unite firm preferences under the umbrella of sectoral or peak business associations. As a response, business associations can do two things. They can choose to represent some (more powerful) members more than others, though this can bring about significant costs in terms of loss of legitimacy and power vis-à-vis policymakers and other internal members. Alternatively, they can take a step back whenever conflicts with firms arise and remain active whenever lobbying alongside firms is possible. In both cases, business associations seem to be bound to a relative decline within lobbying communities.

There are also some limitations to our study. First, we focus on the difference between associations and firms, we could not include any specific indicators of firms. This may include firms that have more resources or firms that have foreign (i.e., non-EU) ownership. The latter especially may be relevant considering the logic of our argument on increased globalization. Foreign-owned firms may be less incentivized to find political consensus with EU firms, and therefore they may lobby alone more frequently. Second, we need to know the exact consequences for political decision-making in the EU. Does the increase in firm lobbying lead to policies for which the gains are more concentrated? Does increased firm lobbying lead to increasing policy outcomes benefiting MNCs? Finally, how do business associations respond to their diminishing role in EU politics? Will they adjust and adhere more to some member firms than othersFootnote 62 or maintain their role as mediators within the business community? And what are the consequences of such decisions? Such questions are critical for a proper understanding of how the EU interest group systems functions and what its effects are.

More broadly, our results highlight that one of the most important changes in the structure of the world economy over the past decade has important implications for the nature of EU lobbying. While we cannot directly link changes over time due to our cross-sectional design, these results strongly suggest that the rise of firm lobbying in the EU is not a fluke, but a permanent feature of EU policymaking. The next obvious question is, what consequences will this trend have? Will it lead to more concentrated distributional gains, as we have seen in the US context?Footnote 63 How will business associations cope with a potential decline of their standing within EU lobbying communities? Considering this phenomenon's potential to yield huge and worrying normative implications, we hope our study will trigger more research into the role and consequences of firms vis-à-vis business associations in the EU and beyond.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2023.15