1. Introduction

Given today's general bias towards euphemisms (cf. Arif, Reference Arif2015), the topic of this paper may seem embarrassing and ill-chosen. However, it makes sense to find out to what extent the spoken language of dialects in former centuries correlated with one of the dark sides of everyday reality. In Britain up to the second half of the 19th century, traditional dialect was the common linguistic medium of the large majority of people (the lower and middle classes), just before the norm of ‘King's English’ and, in linguistics, of système, started playing a dominant role.Footnote 2 We may assume that the English dialects of the Late Modern English (LModE) period (1700–1900) were a correlative of people's everyday life.Footnote 3

This paper focuses on the linguistic expression of ‘dirt’, here provisionally used as a cover term and in the literal, that is physical sense of the word. Dirt mattered as an almost ubiquitous factor of everyday life. While it was, for example in the hyponym mud, not necessarily a bad thing, it was certainly considered bad by many people in urban surroundings and under many circumstances, not the least in view of the hygienic repercussions involved. However, most English history books and works of social or cultural history have disregarded the issue of the hygienic conditions of life in Britain's past (see, for example, George, Reference George1925; Halliday, Reference Halliday1981; Knowles, Reference Knowles1997; Tombs, Reference Tombs2014; Trevelyan, Reference Trevelyan1944;) or marginalized it (Briggs, Reference Briggs1983: 213–4 on pollution, and 253–77 on Victorianism). There are, however, a few specific investigations on dirty environments in England since 1500, to which I will refer below.

As regards the linguistic state of the art, research has generally bypassed many disagreeable sides of life as serious issues, as well as the ‘dirty language’ referring to them. There are a few exceptions. Battistella (Reference Battistella2005) discusses the motivation of ‘bad’ language and its main subtypes. The book shows that linguistic ‘badness is a much more complex phenomenon than it first appears to be’ (2005: 21). The Social History of English by Leith (Reference Leith1983) contains many inspiring observations concerning developments in historical everyday English, but given that the complete history of the English language is at issue and that the book is a textbook for teaching purposes, it does not provide an analysis of LModE dialects. Other contributions available are equally introductory, aiming to provide surveys (Millar, Reference Millar2012) or very specified research results (Kastovsky & Mettinger, Reference Kastovsky and Mettinger2000).Footnote 4 Fischer (Reference Fischer, Kay, Hough and Wotherspoon2004), in a paper on the expressions used in Old English within the lexical field of toilet, paved the way for similar studies, but there have not been many.Footnote 5

Beyond the rules and patterns of the standardized language elaborated in the 20th century and after, it might well be time for linguistics to take into consideration the mechanisms of traditional dialects and of spoken language. As Battistella (Reference Battistella2005: 7) suggested, ‘The idea that dialect and informal speech are organized systems with rules is an important one.’ This approach implies giving up the usual top-down viewpoint in favour of a bottom-up perspective of the intricate interactions between language and society. This paper tries to do so by illuminating the correlation between daily circumstances and daily language within a narrow topical domain. Wright's English Dialect Dictionary, published from 1898 to 1905, is an ideal tool for answering the questions here at issue, on condition that it is used in its digitized version EDD Online 3.0 (2019). As the best and most comprehensive dialect dictionary ever, Wright's EDD provides access not only to written texts as linguistic evidence for the LModE period (the method suggested by Hickey, Reference Hickey2010), but also to the spoken language, including the blacklisted parts of it, from words labelled informal or vulgar to slang.Footnote 6 Given its substantiality (4,500 pages), it is, as Wright himself put it, ‘a ‘storehouse’ of information for the general reader, and an invaluable work to the present and all future generations of students of our mother tongue’ (EDD, Preface, V). The online version, with its elaborated interface and the time covered (1700 to 1900), is an optimal tool for dealing with English dialects of the 18th and 19th centuries and needs no evidential support by any other source.Footnote 7

Using this excellent tool (https://eddonline-proj.uibk.ac.at), the present paper is not only a means to the end of studying the ‘lexis of dirt,’ but also methodologically ambitious in that it demonstrates – in the wake of Markus Reference Markus2020 – a new, synthetic type of dialectology that implies quantification of results and aims at an approximately ‘dialectometrical’ analysis.

2. Dirt, muck, and waste as dominant factors in Victorian life

Dirt, muck, and waste are only three of the many terms used for the physical leftovers of daily life. Unlike in our present ‘plastic age,’ the main environmental problem was not yet a global one of air and water pollution and of the unbalancing of our entire planet. Yet on a personal level, the Victorians were extremely affected by environmental recklessness and the resulting misery.

Up to the middle of the 19th century, before the general installation of WCs and the building of sewer networks, the conditions of personal hygiene were literally breathtaking, particularly in the cities of the United Kingdom. Such were the collateral damages of industrialisation. In her book Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth (2014), Jackson describes the details of how pollution and dirt dominated Victorian life in London.

. . . household rubbish went uncollected, cesspools brimmed with ‘night soil,’ graveyards teemed with rotting corpses, the air itself was choked with smoke.Footnote 8

Stone (Reference Stone1977: 62–3), in his informative book The Family, Sex and Marriage in England 1500–1800, has this to say:

In towns in the eighteenth century, the city ditches, then often filled with stagnant water, were commonly used as latrines; butchers killed animals in their shops and threw the offal of the carcases into the streets; dead animals were left to decay and fester where they lay; latrine pits were dug close to wells, thus contaminating the water supply. Decomposing bodies of the rich in burial vaults beneath the church often stank out parson and congregation.

Things did not improve in the first half of the 19th century. On the contrary, because of demographic growth, industrialisation and poverty, the hygiene of living conditions deteriorated. The invention of WCs helped keep households cleaner but resulted in an excess of sewage in and on the embankments of the Thames. The book The Great Stink of London (in 1858) informs us that this general practice of routing sewage into the Thames, combined with extraordinary heat that summer, brought about a political crisis which later prompted a sewerage scheme to be implemented.Footnote 9 Meanwhile the horses used in London traffic ‘produced approximately 1,000 tons of dung a day’ (Jackson, Reference Jackson2014: 75). Muckheaps had been common in earlier centuries, not only in villages, but also in towns (see Cockayne, Reference Cockayne2007: 20–21, 188). However, by the 18th and 19th centuries, they were, in England as elsewhere, much more than a hill of dung, namely

a stinking morass of human and animal waste, rotten timber, friable plaster, rubble, carcasses, cinders and ashes, broken glass and crockery, clay pipes (. . .) straw, weeds, eel skins, fish heads, peelings, etc. (Cockayne, Reference Cockayne2007: 188).

One does not need further evidence of the hygienic conditions of daily life in towns and cities to envisage the full picture. The countryside was naturally better off in some respects, but worse as regards pigs and other animals, liquid manure pits, and so on.

Some recent scholars have noticed how the vernacular of ‘common people’ reflected their living conditions. Sorensen (Strange Vernaculars, Reference Sorensen2017), for example, has provided a survey of 18th-century collections of slang and cant, provincial dialects, and sailors’ jargon. While all these vernaculars are non-standard, they differ fundamentally: only provincial dialects are primarily place-based; the other vernaculars are class-based. Sorensen's book, like a few others published simultaneously and concerned with the vernacular English culture of the 18th century (such as DeWhispelare, Reference DeWhispelare2017; McDowell, Reference McDowell2017), attest to the increased interest of recent scholars in marginal varieties and text genres of LModE, but they all mainly deal with the era's history and culture. By contrast, the present paper suggests taking the historical circumstances sketched above for granted, focusing on the geographical distribution and other characteristics of dialect lexis concerning ‘dirt’ as represented by the EDD.

3. Quantitative survey of the lexis of dirt in EDD Online

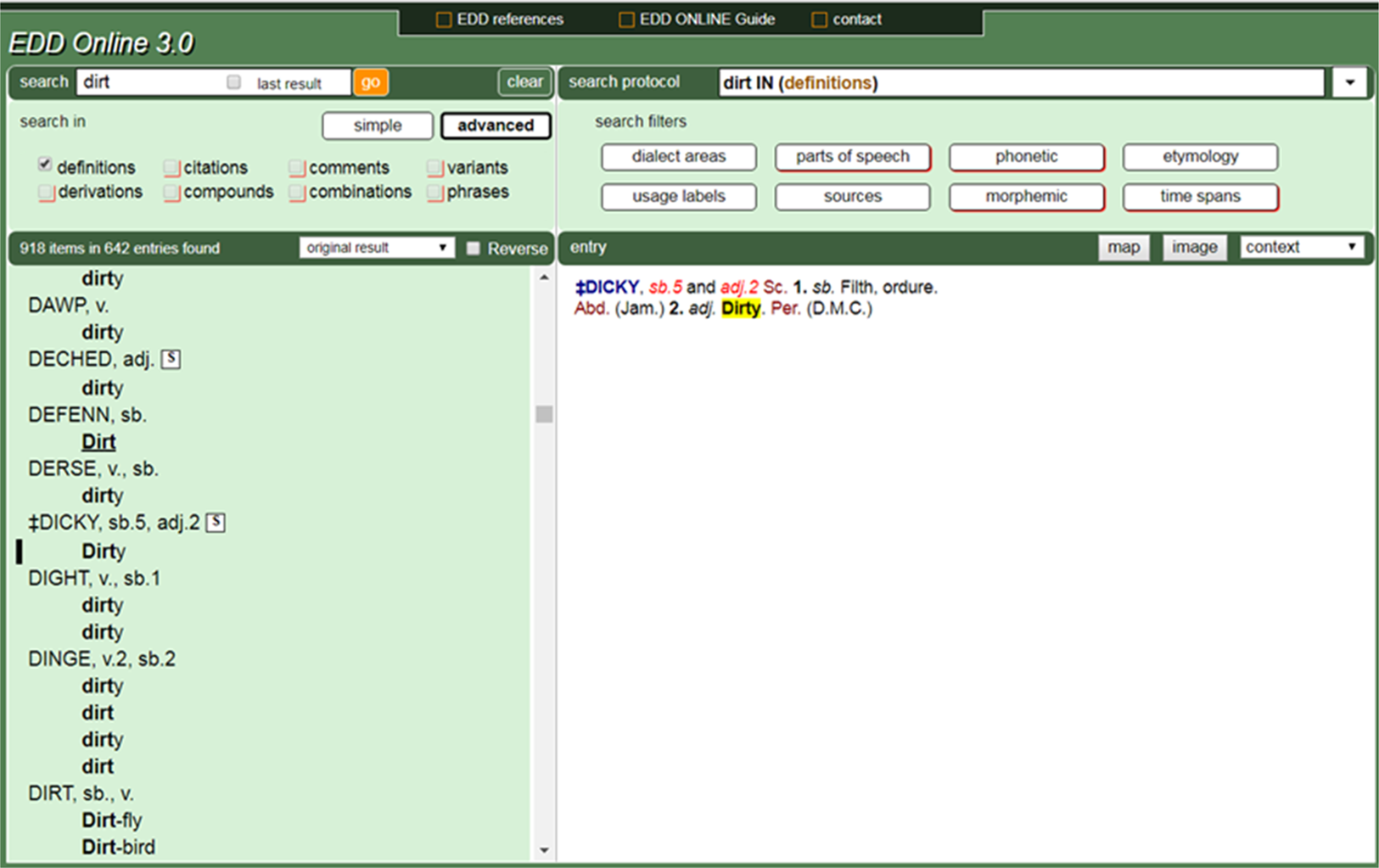

Joseph Wright used a great many dialect words for the lexical field of dirt. Good candidates are ordure (25 matches), dung (237), manure (197), filth (107), rubbish (216), dust (253), and mire (80). If we focus on the three top terms of definition (dirt, waste, and mud), the lists of retrieved dialect lemmas amount to 996, 330 and 645, respectively.Footnote 10 Ignoring the rare cases of overlaps, we would thus have access to nearly 2,000 relevant words. Such a quantification, based on (automatically) truncated strings, rightly includes the adjectives dirty, wasteful, and muddy, as well as other derivations (such as dirtily) and compounds (such as dirty-looking), as they are all part of the lexical field at issue. Figure 1 demonstrates the basic mode of the presentation of retrievals, which provides the headwords involved and, hierarchically subordinated, the targeted string.

Figure 1. Search for dirt (implicitly truncated) as a term of definition in EDD Online

The headword example opened in Figure 1 (DICKY) is typical in that the term of definition (dirty) refers to the headword itself. Unfortunately, as the following discussion will explain, this is not always the case. Also, the sample DICKY is untypical in that it is marked by two signs: a double dagger, which in the EDD stands for lemmas ‘insufficiently authorised’, and the ‘S’ in the white box following the word classes, which marks the entry as part of the EDD's Supplement. Having said this and in the face of a recent investigation of the value of both the Supplement and the double daggers (Markus, Reference Markus2018), users of EDD Online can rest assured that the entries concerned are still worth being included in retrievals.

There is, however, another factor that really affects the reliability of the automatic findings of a search. This is the truncation of the search string itself. Users are in a dilemma here. If, in the case of mud, they switch off the truncation (triggered by double quotation marks), they exclude the (frequent) adjective muddy. This exclusion would not make sense. If they switch the truncation on, the retrieved terms of definition misleadingly include strings such as curmudgeon and muddle. To illustrate this, Figure 2 presents the results of a search for mud in the convenient column 2 counted mode (see the white box above the retrieval list). Column here refers to the different hierarchical levels of the lists of query results, with headwords always figuring highest (as Figure 1 has demonstrated). Figure 2, with its alphabetised list of ‘mud-words,’ allows for an easy exclusion of the invalid findings. The problem of truncation causing unreliable results should thus be solved.

Figure 2. Rearrangement of the matches for mud as a defining term, in the column-2-counted mode

The ambiguity of the string mud, however, is exceptional. The sorting routine column 2 counted for dirt provides the evidence that all defining keywords, unlike those for mud, are valid. The same holds true for waste (with rare exceptions), ordure, dung, manure, filth, rubbish, and dust. Muck, on the other hand, is less easy to isolate as a string because it is part of other strings such as smuck (‘smart’) and muckle (‘big’).

Despite this risk of producing unprecise retrieval results due to the ambiguity of some of the strings used for queries, we can still hypothetically argue that the lexical field of dirt has been proved to be densely filled with dialect words in the LModE period. There is neither a need nor the time to check the nearly 2,000 dirt passages for their validity here. To obtain full evidence, however, we will first be looking at the level of form, investigating aspects of word formation and of the variance of the dialect words at issue. In a second step, our focus will be on the semantic issue of what exactly dialect terms of the lexical field of dirt have as referents.

4. Formal evidence

Dirt and waste as such, like the other keywords of definition mentioned above, are, of course, not dialect words. Yet the EDD has rightly lemmatized them because part of their integration into the language system was non-standard. The major formal aspect to be studied here is that of word formation, under the inclusion of phraseology. The question is to what extent and in what way formations with the monemes dirt and waste were productive in the English dialects as described by Wright for the time from 1700 to 1904.Footnote 11

4a. Word formation

In the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (DCE; 6/2016), the entry for dirt includes about a dozen compounds and phrases, such as dirtbag, an informal, especially American English expresssion for ‘someone who is very unpleasant and immoral.’ An example of the phrases is to treat sb like dirt. Waste, again according to the DCE, is slightly more productive in Present-day English, both in the literal and the figurative sense of the word.

Dirt and waste, then, are good candidates for checking the readiness of English for compounding and for building idiomatic phrases.Footnote 12 Waste, in particular, reflects recent industrial developments in combining lexemes such as waste disposal unit (for AE garbage disposal), as well as the growth of environmental awareness in collocations such as recycle waste. However, the productivity of both words in English dialects, as documented in the EDD, was remarkably higher. Moreover, it is not only the quantity, but also the quality/type of word formation which should deserve our interest.

EDD Online provides 43 matches for dirt as part of a combined lexeme (compound, combination, derivation) and nine matches for phrases. In compounds, dirt is used as both a determinatum of compounds and a determinant.Footnote 13 Under CAT we find cat-dirt (‘a species of limestone’), under CLEAN clean-dirt (‘earth or mud, in contradistinction to anything foul or offensive’). The column 2 counted mode makes it easy for users to find the other compounds with dirt as a determinant (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Formations with the string dirt in EDD Online

The retrieval list at its bottom includes nine compounds with dirt as determinatum, from dog-dirt down to top-dirt, moreover, at the first glimpse, three derivations, dirten (dirtin), dirtenly and dirtrie. The major part of the list consists of compounds with dirt as determinant (such as dirt-bee) and of idiomatic phrases such as dirty butter, which is the type Wright has mostly referred to as ‘combinations.’ In addition, EDD Online allows for the retrieval of dirt-phrases proper, nine in number. One of them is to give a person the dirty kick out, which is more visual than what it stands for (‘to jilt sb.’)

The meanings are, however, of secondary interest here. Instead we should pay attention to some of the patterns involved in our findings. The derivations dirten and dirtrie make use of old suffixes -en/-in and -ry/-rie respectively. -en/-in is a suffix of the past participle of many strong verbs (see OED, -en, suffix 6), as in Present-day English spoken, also of adjectives, as in earthen. In the case of dirten, the Standard equivalent would be dirtied. The form dirtin in dirtin-gab (‘a person with a foul mouth’) is a variant of dirten and, according to the EDD sources, attributable to the Scottish county of Berwickshire. Like dirten, dirtrie makes use of an old (nominal) suffix that still survives today in a relatively small number of words, such as parsonry and peasantry, and, according to the OED, expresses among other senses ‘things or activities of a certain type collectively.’ The form with -rie, as both the OED and the EDD confirm, corresponds to Scottish usage in the 17th century and after (see the OED in its ‘advanced search’). The suffix, in whichever form, early merged with the suffix -erie stemming from ME, with French -erie and other Romanic languages in the background (from Lat. -aria).

The derivations in our retrieval list of Figure 3, then, give evidence of the dialectal productivity of old suffixes, no matter whether of Germanic (-en) or French (-rie) origin. These are suffixes that had obviously lost ground in the history of (Standard) English. As we noted in passing, both suffixal forms could be attributed to Scotland, and -in in dirtin-gab (= variant of dirten-gab) specifically to Berwickshire. In order to avoid this possibly coincidental attribution to Scotland, users of EDD Online may easily check the two suffixes as to their general occurrence beyond dirtin-gab and dirtrie. This can be achieved by narrowing the search for the strings at issue, combining them with the filter parts of speech/keyword adjective in the case of -en, thus avoiding participle forms, and keyword noun in the case of -rie. Figure 4 shows us the results for the adjectival suffix -en.

Figure 4. Search for derivations with -en as adjectives, arranged dialect-wise (column 3 with 2)

Figure 4 shows that a large number of the findings, such as muckeren (highlighted in the entry window), are from English counties. There is also an example from Pembrokeshire (in Wales), which indicates that our initial attribution of the suffix to Scotland was premature. However, Pembrokeshire, being part of ‘Little England Beyond Wales’ for its historical affinity to England, is an outlier. In terms of time, the OED shows that since the 16th century there has been a tendency, except in south-western dialects, to discard the adjectives with this suffix in favour of the attributive use of the corresponding noun: gold watch instead of golden watch (-en, suffix4). The OED goes on to say that, apart from such local survivals and a few exceptional cases (such as wooden and woollen), the suffix was only used ‘metaphorically, or with rhetorical emphasis’ (see golden). This semantic/stylistic restriction would, thus, be another niche, in addition to the dialectal/regional and temporal ones, where adjectival -en survived.

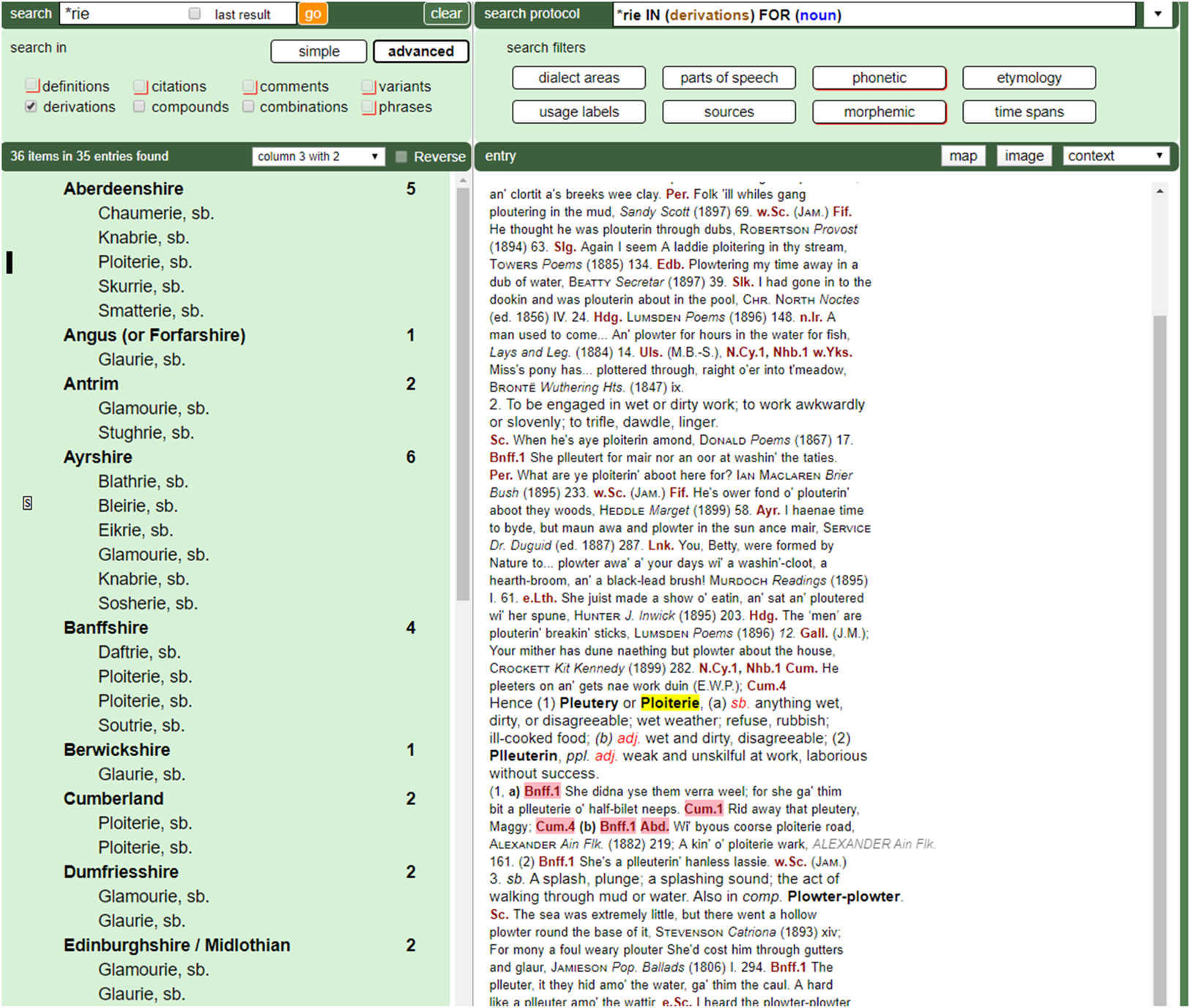

In the case of -rie, however, the initial assumptive attribution of the findings to Scotland widely holds, as is suggested by the beginning of the retrieval list in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Retrieval of derivations (nouns) ending in -rie, with the automatically activated areal distribution, presented in the column 3 with 2 mode

The retrieval window in Figure 5 does not, of course, present the full picture of the 36 derivations. Users may, however, get quick surveys by using the different sorting modes. The column 2 counted mode, for example, would provide the derivations themselves. We could thus easily find out that some of the matches belong to our lexical field dirt, namely chaffrie (see chaff), gilreverie (‘wasteful conduct’), glaurie (‘soft mud’), plorie (‘any piece of ground which is converted into mud by treading or otherwise’), spleutterie (‘dirty mass’), and ploiterie (‘anything dirty’). This enhances our hypothesis of the large role of references to dirty matters in the language of LModE dialects.

However, the sorting mode presented in Figure 5, with dialect areas ranked highest, encourages another presentation mode apt to provide a survey of the geographical distribution. The button above the entry window (map) prompts a multi-colour map of the retrieved quantities of Figure 5, with normalisation working in the background (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Mapping of the results of Figure 5 concerning -rie

The map, which includes references to counties, but also to areas and ‘nations’ (Scotland, Ireland), reveals that the morpheme at issue is clearly attributable to Scotland and Ireland, with some visible impact on Yorkshire and the English border counties Cumberland and Northumberland. Though the absolute numbers are relatively low (only two occurrences for the Irish county Antrim), the map allows for recognising a pattern: the nominal suffix -rie, with a relatively high frequency in the Shetland Islands and a lower frequency in the rest of Scotland, as well as in Ireland and northern parts of England, was so common that it also had an impact on common-and-garden words such as dirt, thus forming dirtrie.

The string dirt, which is what we started from at the beginning of this section, has also found its way into phrases, such as lost in dirt and cheap's dirt. The latter phrase is reflected in the OED entry dirt-cheap, which is not labeled there as dialectal and based on five sources from 1821 to 1891. The last one, from 1891, is also the one that Wright used (Thomas Hardy). There is no need here to follow up on the track of all the other ones. They all raise questions of their own. One of the nine phrases, worse than dirty butter, is quoted twice, under worse and under butter, and thus slightly disturbs the statistics. Another one, marry come up, my dirty cousin, is originally an interjectional oath, calling the Virgin Mary as a witness, thus inviting the issue of the combination of dirt with originally religious terms.

The cumulative evidence provided in this section allows for the conclusion that the lexeme dirt was formally most productive in prompting further words and phrases based on it. The fact that some of these, such as dirt-cheap (a reduced cheap as dirt), can now also be found in the DCE and are not marked for dialect in the OED, is no argument against the assumption that they were used in dialect first. The DCE at least marks dirt-cheap as ‘informal.’ The OED has the comment that the entry ‘has not yet been fully updated’ and that it is based on the first publication of 1896. In sum, it is clear that the productivity of dirt for the formation of combined lexemes and phrases mainly came from the language of dialects rather than from the standard variety of English.

4b. Formal variance

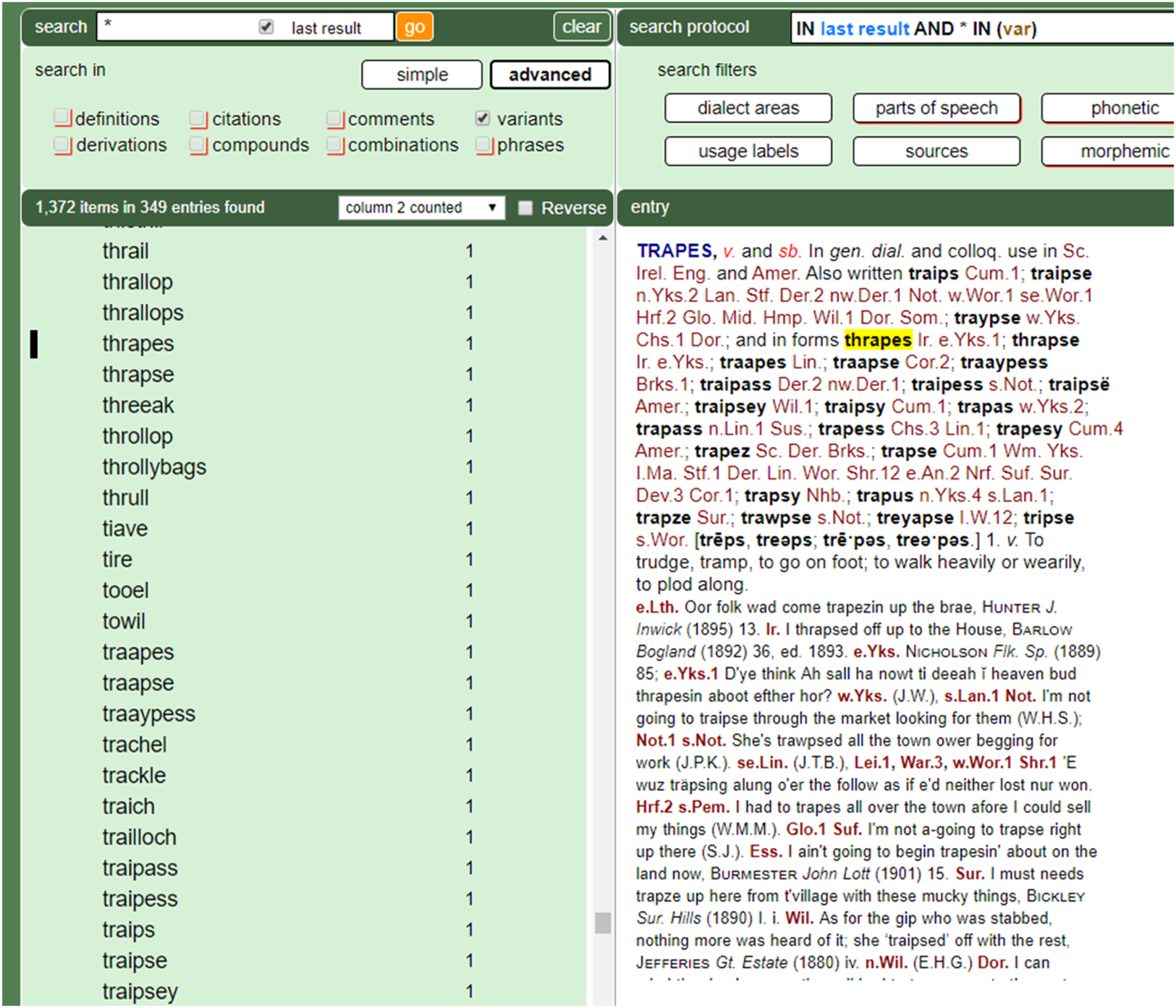

Given the general fluctuation of dialect spellings, a formal analysis of the string dirt in dialect words also has to include the (spelling) variation of the headwords concerned. EDD Online allows a kind of piggy-back search (so-called last result, see this button in the search box). Dirt as a headword string provides eleven variants (such as durt, dotty [for ‘dirty’]). If we widen the query to include all entries with the truncated string dirt* in their definitions (rather than in the headwords), the output is much higher. The last-result mode means that, subsequently to the query for definitions, we search for all variants of the headwords delivered in the first place. Figure 7 presents the result:

Figure 7. Last-result search for all variants of lexical items semantically associated with dirt, with the results arranged in the column-2-counted mode

Figure 7 shows that we are dealing here with no less than 1,372 variants in 349 entries. Thrapes, the example opened in the figure for the sake of demonstration, is a good example of the complexity of the information provided by EDD Online. The great number of variants just for one lexeme and the huge number of the list's figures both reveal that dialect forms referring to ‘daily dirt’ in some way or another were very common. As dialectal pronunciation mainly affects frequent words, i.e., function words and frequent content words, an extreme formal dispersion of a dialect word, such as trapes in Figure 7, attests to its everyday relevance. Trapes, for example, in one of its senses of dirt, is associated or connotes with wool and sheep. Another high-frequency example in our retrieval list is the entry for cow, which does not come as a surprise, given the relevance of cows in people's lives.

The spelling and phonetic variation of dialect words such as TRAPES in Figure 7 is an important factor that scholars of LModE dialect corpora (before the EDD) must consider. The full relevance of a word's usage can only be weighed if the variants are included in the analysis.

A lexeme's productivity, however, goes well beyond its formal creativity in word formation and in developing variants. Its main field can be traced in semantics. In the following, we will, therefore, raise the question of what the dialectal terms denoting or connoting dirt refer to.

5. Semasiological approach

In the 642 entries that contain dirt or dirty as a defining term, the semantic references to dirt are, naturally, most variable. The same holds true for the 286 entries checked for waste and the 466 entries for mud. The reference to the keyword may be very general or most specific; it may be a central part of the definition of a dialect word, or a very peripheral or merely connotative feature, for example, when mention is made of a tool used to remove dirt. Finally, dirt/waste/mud may be used as defining terms in a literal or figurative sense. The semantic diversity is higher with verbs and adjectives, whereas the nominal findings (458 in the case of dirt) generally imply a more direct reference to the keyword.

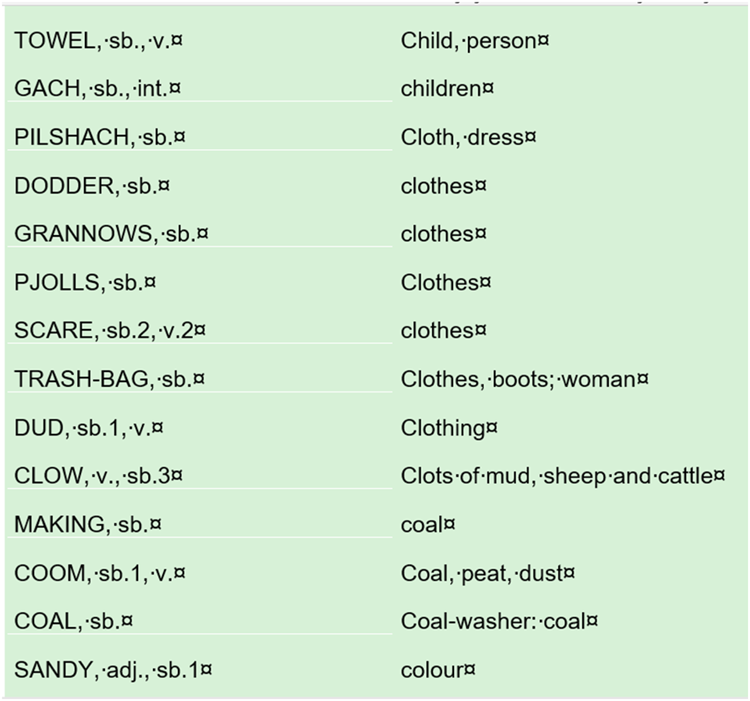

Given this complex picture, we will limit the analysis to the 458 nominal findings of the keyword dirt only. Even so there is a great deal of ambiguity left in the definitions. To counter it, I manually created a working table of the headwords concerned, which I then equipped with the main catchwords of what dirt refers to in the respective entries. After an alphabetical rearrangement of the table according to the column of the catchwords, the data were ready for an interpretative analysis. Figure 8 presents an extract of the rearranged table, which is too long to be printed out here in full.

Figure 8. Extract from a manually created table of 458 lines listing the headwords of all entries in EDD Online containing the defining string dirt, with their referents

A cut-and-dried typology of the referents of dirt is more than can be included here. Given the significant role of polysemy and homophony in dialect words, we are confronted with a great many multi-referential definitions. The first observation to be made therefore is that, in the sphere of everyday dirt, there is a remarkable lack of denotative precision.

Nevertheless, the table allows some favourite types. Dirt is associated or collocated with:

- animals (sometimes in combination with children):

grub, ashiepattle, ashypet, smulk, aulin (bird), sty (pigs)

- anything dirty or sticky:

labber, lobber, dicky, mawk, muckment, clat, gorroch, dag, foul, fouse, fussock, graum, greet, heal, ket, hack, mudgin, nast, muck, muckson, mudge, offal, orrack, overall, paddle, pakes, pash, pick, pie, pig, piggery, plid, plouter, pound, pudge, reap, rogue, rusty, scriog, seugh, shovelling, slabber, saldder, slart, slat, slodder, slubber, slutch, smitch, smudge, splash, splatch, splatchin, stilt, tave, udder, verg, wally-draigle, willy, defenn, morge, flath, grammer, rubble, grub, mess, mawks

- body:

grout, cobweb (eye)

- boots/shoes:

trammel, slap

- children:

urchin, grub, towel, gash, brat, mud-lark, taggle, urf, scrub, punky

- cloth/clothes/textiles:

pilshach, doder, pjolls, scare, dud, lag, pelt, walgan, trailach, skut-civwe, trapes, trash, rauk, drent, pell, lorrach

- coal/soot:

coom, coll(e)y, blatch

- condition (= dirt):

messment, slatter, myrtyr, aggle

- cow:

trolley-bags, tittle (also sheep), slurry

- dung:

mouse, scarn, sew, mucklesaur

- earth/soil:

clob, logger, dit

- excrement:

keech, dreik

- face:

brook, poison, sharn

- fellow/man:

fust, sloit, slubber-de-gullion, trubagully, sliving, old

- female/woman:

trolly-mog, mundle-dirt, slatch, targle, tarloch, toosht, molly, picking, mucky heap, traik, trollop, mally, assypod, bum, callet, clam, cleeshach, dage, dawgos, dawkin, dollop, dough, draw, fruggan, hag, huisk, leverock, maulmas and many others

- fingers/hands:

plout, dinge, reeang, crowls (wrinkles of the hand)

- floor:

patter, clunker

- food/eating:

flight, slaich, slairg, sloch, slairy, souse, spleutter, slag(g), pouse, sludder

- girl:

clay, streel

- grease/grime:

swarth, kell, grout

- heap:

binkart, binker, cob(b), hob-gob

- housework:

blackguard

- liquid/wet place:

glaur, graith, slipslush, stabble, spark, scummer, gault, lytrie, lollypop, trachle

- manner/behaviour/state:

slare, slobber, slur, smough, splutter, slotter, steerach, traik, trollop, bummerjakes, modge, mucker, shape, stroll, puxy, strush

- mark/spot/stain:

slake, smud, blatch, blad, spattle, sulch, smit, swelsh,

- mass:

atteril, filchan, kaarm, lefty, mammock

- mud:

dung, fen, dub, dubble, glutters, posh, jaup, clobber, soil, blather, drabble, scruffin, gor(e), slake, batter, guzzen-dirt, slurry, soss

- person/people:

grease-horn, flutter-grub, pickle (grown-up person), Jack a lent, lurt, rabble-rash, ax-waddle, blossom, blutter, broom, bruz(z), dabby-nointer, dallack, drazil, feague, flotch, gampsheet, hound, howlet, huckmuck, hudderon, lutter-pooch, podge, pot, puddle, pug, ramscallion, shab-rag, shaffle, shallock, skelp and many more

- place:

draig, smithy, jaw-hole, midden, auction

- smoke:

smush, smutch, smeech, reech

- something sticky:

bawd, cab, clabber

- tool against dirt:

limp, claut

- water:

beau-trap, gubben, clart (half-liquid), slorach (half-liquid), jaup, blots, cundy, sink, slosh, sullage, cist-pool

- wetness:

slather, slot, sess, draggle

- sheep/wool:

dag, moor, brands, clinker, tag, dock, dod(d), locks, purlock, round, tailin(g), corvins, burl, dress

- work:

gutter-grub, gur(r), clorach, clutter, glorg, guddle, jotteral, jottery, pegil, poach, scuffle, scutch, scutter, slaister, sludgery, slug, swine, scodgy (in kitchen), sloiter, sotter, sluther, clypach, clype

I have somewhat normalized the terms of definition for this list and eliminated very special cases (hapaxes, such as GRANNOWS, only found in one source for Shropshire). Also, the list does not document the many polysemic definitions. The general references to dirt (here listed under ‘anything dirty or sticky’) as well as the references to women are so frequent that they are only selectively quoted to keep the complete list in moderate length. Even so, we may draw the following conclusions.

First, the above statement that references to dirt are tendentially marked by the lack of denotative precision is confirmed. The fuzzy references to dirt in general are predominant, the obvious reason being that, in emotional utterances, dirt simply stands for something disagreeable or negative. This semantic fuzziness or even emptiness in favour of a mainly expressive pragmatic function is known from vulgar terms and swearing in Present-day English.Footnote 14 Second, dirt is associated with diverse everyday ‘referents’ (from animals to work), as could be expected. However, the references to people (also see person, fellow, girl and female/woman) have turned out to be surprisingly frequent. A reason for this could be that the reference to people rather than ‘dirty’ things implies a higher degree of emotional involvement, which may have given rise to linguistic creativity. In connection with this creativity, the reference to dirt in the human sphere is often marked by a figurative rather than literal understanding of dirt. This tendency towards emotionality and figurativeness in dirt references within the human sphere is the third point of observation to be made here. To prove it in the following, it seems advisable to focus the questions at issue on one of the referents listed above, women.

Of the altogether 41 references to ‘dirty’ females or women, with the list alphabetically arranged, the very first one, ASHYPET, is already typical. The definition goes: ‘An idle or slatternly woman, a ‘Cinderella,’ engaged in dirty kitchen work. Occas. applied to a man.’ The definition of ASSYPOD, the next headword on the list, sounds similar: ‘A dirty, slatternly woman.’ The typicality of the two cases lies in the correlation, carried by sexist prejudice, of a term of description (dirty) with a term of judgement (slatternly). In one of the next samples, BUM, the definition makes it explicitly clear that we are not talking here about descriptive terms, but terms of scornful judgement. BUM is defined as a ‘term of contempt applied to a dirty, lazy woman.’ BLOSSOM, otherwise used for ‘an extremely dirty person or thing,’ is also used ‘ironically [as] a mild term of reproach to a woman, a hussy.’ CALLET is a Scottish and northern English term for ‘A prostitute, trull; a drab, dirty woman.’ CLAM is a ‘very dirty woman, slut.’ CLART is defined as a ‘dirty slovenly woman.’ Finally, CLEESHACH is a Banffshire term for a ‘stout, unhealthy, dirty-looking woman.’

It would be unfair to fault Joseph Wright or the author of this paper for having traced such passages. True, the terms of definition are Wright's. Many of them (like slattern) would not be cited today without a signal of distance, such as vulgar or taboo, or at least informal. However, Wright is simply describing dialect use in the vernacular of his time. Rather than raising a sardonic eyebrow, we may interpret the dialect use just analysed for what it is: a testament to a deeply rooted cultural belief that women in general are ‘dirty’. The LModE language of dialect simply follows track. This indulgence in permanently referring to the ‘dirt’ of women is, of course, a pathological prejudice. The few examples quoted – we have only reached the letter C going through the alphabetical list – may suffice to show that the attribute of dirt, even when superficially used in the physical sense, is nevertheless also intended in the figurative sense, standing for women's allegedly ‘dirty’ behaviour or character.

These observations may be seen within the wider context of other lexical fields negatively relating to women, for which Hughes (Reference Hughes1991: 206–235) has provided a survey. He describes the whole ‘male-derived system of chauvinist bias’ (p. 206) in its evolution from Old English to the 20th century. Tracing the deeper motives of the concept, he mainly focuses on sexuality, but also refers to the stereotype of women in terms of ‘filth, slut, slattern and so on’ as one of the long-lived abusive images.

This is not the place to discuss the theological background (the Madonna-whore dichotomy in Christianity) or the state-of-the-art of publications on sexism in language (for which see, for example, Caldas–Coulthard, Reference Caldas–Coulthard2020). However, in the face of the pattern of perception just described, many seemingly harmless expressions such as DAG (for ‘dew/dewdrops’) and dagged (‘damped’) can be identified on closer inspection to confirm the significance of the pattern. Thus, DAG has prompted sexist senses in compounds: dagged is first defined as ‘splashed with dirt,’ but has, via this association of dirt, developed dagged-ass (‘slatternly woman’), dagged-skirted (‘slatternly’) and dag-tail (‘a slattern, slut’). Similarly, DRABBLE has given rise to the formation of compounds of the same sort (see Drabble-tail).

The extremely high frequency of references to ‘dirty women’ is, as Hughes’ (Reference Hughes1991: 30, 206) suggested, part of a more general semantic derogation of women. Women in dialect, according to EDD Online, are also pushed into other ‘dirty’ roles. The word FRUGGAN, literally a tool for handling the ashes in an oven, has been transferred to a ‘dirty woman’, with the connotation hag (see Hughes’ witch/hag/virago complex [Reference Hughes1991: 224]). HAG itself was used for a ‘violent, ill-tempered’ or ‘ugly’ woman. Other attributes are unwieldiness (HUISK), corpulence (‘fat woman’: MAULMAS, PULT, FLOTCH, HUDDERON), carelessness/impudence (SNICKET), wearing dull and unfashionable clothes (Trully, under TRULL).

Such are cases of male chauvinism, with women thoughtlessly or designedly victimized. The attitude is misogynistic, but its broader basis seems to be general disrespect of others: men, ‘people’ and ‘persons’ are occasionally also targeted (see the list provided above). However, as mentioned earlier, the language of dialects less aims at denotational clarity, but tends to be pragmatically expressive, i.e., the speakers’ attitude is as important as to what or to whom they refer.

The polysemy resulting from this basic emotional function of dialect speech is occasionally marked by labels of the figurative sense of an utterance. In our first sample in the list above, the last-result query for dirt in combination with person as defining terms provided ATTERMITE. This Lakeland term meant a ‘water-spider,’ but in Lincolnshire it was used metaphorically for ‘a very small person’ and ‘a dirty child.’ The exact route of the metaphorical transfer is of no interest here, though one could imagine that the running nose of a poor and dirty child could be the basis of the association with the water-spider so that the semantic transfer from the child to the very small person generally could be the second step of the metaphorical development. However, the implicit emotionality is made explicit when Wright then adds the label ‘Used derisively’. Equally, BLOSSOM is used for a woman or extremely dirty person ‘ironically’. HOUND is ‘a term of reproach’ applied to ‘a dirty, idle person,’ Howlet (='small owl’), referring to a ‘fool’ or ‘noisy or dirty person,’ has the same label. And SNOTTY (Wright: ‘having the nose running with mucus’) is transferred to a ‘dirty, mean, despicable person...as a term of contempt.’ Finally, SPITTLE is labelled as a ‘term of supreme contempt or loathing.’

Labelled or not, the reference to ‘dirty’ persons, where dirt is a correlative of all kinds of external or social nonconformity, is even more common than the reference to ‘dirty women’. People are given the names of dirty or otherwise inferior animals or are associated with dirty things. In either case, the attitude of contempt or looking down on other people is most striking. The entries on DOG, PIG and SOW may illustrate the former type (animals), the entries on BROOM, CAB (Webster's 1989: ‘a horse-drawn vehicle’) and DOUGH the latter (things).

6. Conclusion and outlook

The ubiquity of environmental pollution in the British Isles and Ireland of the 19th century was our first concern. The description was sufficiently detailed to bring home to the reader that this side of European history has unfairly been neglected and also to make plausible why the vernacular of ‘the people,’ equally disregarded by many scholars of English varieties today, was so much burdened by issues and expressions pivoting around dirt, muck, and waste.

This paper – unlike many previous ones in English dialectology – is not a study of a certain regional dialect, nor does it focus on a clearly defined linguistic item, as would be dirt qua lexeme or semanteme. Rather, the concept of dialectology suggested here, in line with theories of quantification in ‘dialectometry’ (Goebl & Smečka, Reference Goebl, Smečka, Kelih, Knight, Mačuntek and Wilson2016, with references to previous literature), is that it makes sense to trace the theoretical construct of the ‘ideal’ dialect speaker, similar to the ‘ideal native speaker’ in Noam Chomsky's sense, behind the diversity of language patterns. This ‘synthetic’ approach implies that we can find features of similarity between individual (English) dialects if we manage to get an overview. The surface presents strings, which can be lexemes, morphemes, phonemes, and so on, and whose historical usage can be attributed to specific geographical areas. Unquantified observations tend to produce fragments of often irrelevant or misleading knowledge on the part of dialectologists.

The synthesis is possible with the help of the computer. EDD Online allows for transparency of LModE dialect data. This paper is meant as a test case for a new kind of quantitative dialectology. The evidence was first based on frequency figures concerning the role of dirt as a defining term and concerning some of its synonyms in the whole EDD. The initial suspicion that many words were available to denote or connote dirt was further fuelled by the analysis of the dialect words themselves. Given their huge number, the investigation focused on dirt alone as part of combined lexemes and phrases. The results proved the productivity of the term dirt in all sections of word formation and phraseology. We selected the derivations for a detailed discussion, finding out that the productive suffix -rie was a linguistic relic, spread in Scotland and Ireland, with some overlapping into the north of England. In other parts of England, it played an only marginal role in the literary standard. It survived within the language of the people in regional ‘niches,’ nourished by the ubiquity of pollution. The other suffix discussed, adjectival -en, turned out to be more generally distributed in dialects, though with a tendency towards rural ones. Given its diminished role in Present-day English and its increasing semantic and stylistic restrictions though, it could be called a dialectal as well as historical relic, with dirten being a typical example.Footnote 15

The formal analysis also included a study of the variants of terms denoting dirt. The high degree of variation was interpreted as a correlation to the high frequency of the everyday issues involved (connected with dirt).

In its main section, the paper concerned itself with semantic aspects of dirt by raising the semasiological question of the ‘referents’ (that is, the objects of reference). As could be expected, dirt is an issue either generally or specifically, and in the latter case refers to both people (their appearance and behaviour) and things. Many aspects could have been discussed in this section, given the huge amount of material. A comprehensive analysis was not possible nor intended in this paper. After selecting a few examples, we focused on sexist and partly figurative references to women, and on the pragmatic function of self-expression to be found in many ‘dirt terms.’ Calling somebody a ‘sow’ is, pragmatically, like swearing: letting off steam through the choice of words. Women were the main victims of this (male) chauvinism, but seeing them in terms of dirt was a linguistic specificity conditioned, among other things, by the ubiquity of dirt.

The by-effect of this paper was a methodological one: to remove dialectology from the usual focus on individual linguistic items (sounds, words, and geographical areas). This neogrammarian method disregards the social and cultural contextuality of language and of dialects. Dictionaries, with their alphabetical arrangement of words, have tendentially encouraged this kind of narrow analytical approach. With the availability of EDD Online, as with that of the OED in its digitized form, scholars’ interest in words can, now more than in the past, encompass the embeddedness of words in structures of word formation, semantics, and other linguistic domains as well as in the socio-cultural environment.

MANFRED MARKUS is a Full Professor Emeritus of English linguistics and mediaeval English literature at the University of Innsbruck. He has over 100 publications on his record, among these Mittelenglisches Studienbuch (1990), Middle and Modern English Corpus Linguistics (as co-editor, 2012), and English Dialect Dictionary Online: A New Departure in English Dialectology (CUP, 2021). With a background in English and American literature, he has, for the last 30 years, focused on contrastive linguistics, historical English, corpus linguistics, and English dialectology. He has compiled several corpora, among these the Innsbruck Corpus of Middle English Prose and the Innsbruck Letter Corpus 1386 to 1699. In 2019, he launched a digitised version (3.0) of Joseph Wright's English Dialect Dictionary, EDD Online, which is based on 12 years’ project work supported by the Austrian Science Fund. Email: [email protected]

MANFRED MARKUS is a Full Professor Emeritus of English linguistics and mediaeval English literature at the University of Innsbruck. He has over 100 publications on his record, among these Mittelenglisches Studienbuch (1990), Middle and Modern English Corpus Linguistics (as co-editor, 2012), and English Dialect Dictionary Online: A New Departure in English Dialectology (CUP, 2021). With a background in English and American literature, he has, for the last 30 years, focused on contrastive linguistics, historical English, corpus linguistics, and English dialectology. He has compiled several corpora, among these the Innsbruck Corpus of Middle English Prose and the Innsbruck Letter Corpus 1386 to 1699. In 2019, he launched a digitised version (3.0) of Joseph Wright's English Dialect Dictionary, EDD Online, which is based on 12 years’ project work supported by the Austrian Science Fund. Email: [email protected]