Introduction

One of the most puzzling political facts of the last few years has been the enduring and consistent support for personalistic populist leaders. Salient examples span the globe, including developed and developing countries alike. For example, Donald Trump in the United States and Viktor Orbán in Hungary were able to maintain substantial support despite unrelenting media criticism, controversy, and the most severe public health crisis in a century.Footnote 1 What is most puzzling is not that some of their citizens support them, but rather, that despite all the aforementioned concerns their support has been stable over time. The stability in levels of public support towards contemporary populists is markedly different from that of most national leaders, whose popularity usually vacillate substantially because of their actions in office.

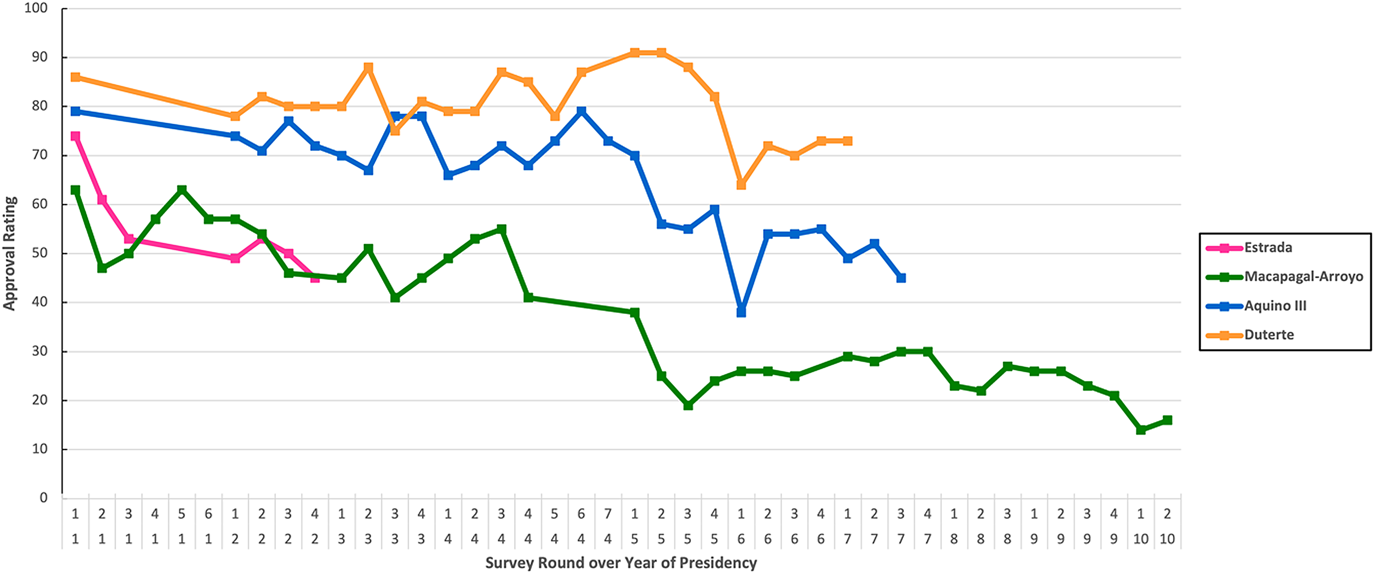

Nowhere has this been truer than in the Philippines under the Presidency of Rodrigo Duterte. Duterte won in convincing fashion the 2016 election, besting his opponents by more than 15 percentage points. But even with that victory, there were reasons to question Duterte's ability to earn and keep the support of most of the public. First, in a multi-candidate race Duterte won with far less than a majority—capturing only 39 percent of the votes for president. Second, the history of Philippines presidents (and politicians more generally) is that public support tends to wane over course of the president's term in office. Figure 1 displays the support for the last four presidents across their terms, as measured by Pulse Asia, a leading Philippine survey firm. While we see the familiar peaks and valleys associated with various successes, failures, and scandals of any given presidency, across all prior presidents we witness a secular decline in their support over time, regardless of the level at which they started. Duterte stands out as the surprising exception. His support starts high and has remained so throughout his term. What explains this enduring level of support, despite numerous setbacks and scandals? This paper tackles this puzzle.

Figure 1. Approval rating of Philippine presidents

Note: This figure charts the approval ratings of the last four Philippine presidents. The first row on the x-axis is the survey round in a given year. The second row on the x-axis is the year of the president in office.

Given the pressing nature of the question and the large body of work on the causes of populism more generally, surprisingly little has been done to examine the stability of public opinion for populists once they are in office. Existing studies offer a variety of theories on the emergence of populism. Economic explanations such as the loss of jobs due to globalization and increasing economic inequality (Guriev Reference Guriev2018@ Rodrik Reference Rodrik2018), cultural explanations such as the desire to preserve traditional values and ways of living (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), or institutional explanations such as the erosion of the legitimacy of a country's governing institutions (De la Torre Reference De la Torre2016; Doyle Reference Doyle2011) have all been posited as reasons for the rise and success of populist politicians. These are structural conditions that help induce voters to sweep populists into power. But once in power, even populists must rule. And as rulers, they are subject to the whims of public opinion.

We know a lot about the conditions that lead to populist rule, but much less about the nature of their support, and how they maintain it after they take office. Existing work has (understandably) focused on the ways in which some populists work to undermine or circumvent accountability mechanisms once in power, which makes it more difficult for the opposition to challenge them (Diamond Reference Diamond2015; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019). This is certainly an important part of the populist story in many countries, but it is not the entire story. Populists are, after all, genuinely popular, at least with some segments of the electorate. Once they come to power some are able to maintain those high levels of popularity, while others are not.Footnote 2 As such, an open question remains: why do some populist politicians maintain stable levels of public support after they have been elected?

Our explanation for Duterte's enduring support focuses on role of ethnicity. We argue that Duterte and his campaign should be viewed through an ethnopopulist lens. Drawing on the existing literature we define an ethnopopulist campaign as one that fuses inclusive ethnic appeals with populist mobilization strategies (Madrid Reference Madrid2008; Cheeseman and Larmer Reference Cheeseman and Larmer2015).Footnote 3 The inclusiveness of such appeals is a key part of our definition. Unlike exclusionary ethnic parties, which are often focused on defending, protecting, or recovering the privileges of historically dominant groups perceived by some to be under threat (e.g. the AfD in Germany) inclusive ethnopopulists emphasize securing privileges and benefits for neglected groups, while making common cause with non-co-ethnics through populist appeals. We can distinguish ethnopopulists from both exclusionary ethnic parties, which mobilize on the basis of narrow, group-specific appeals, and ordinary populists, which do not include appeals to ethnic identities in their mobilization rhetoric.Footnote 4

We argue that the combination of inclusive ethnic appeals and populist rhetoric helps account for strength and stability of support for Duterte. In contexts with low levels of ethnic polarization and relatively fluid ethnolinguistic boundaries, populists can strategically engage in rhetoric that unifies diverse ethnic bases into a larger coalition against a minority insider elite. These broad coalitions, and hence public support, are stable because while ethnic identities are constructed and somewhat malleable, ethnic divisions, once salient, tend to endure. Moreover, since ethnopopulism taps into a core identity of many citizens, it produces such deep affinity among its supporters that they tend to provide overwhelmingly intense support. As such, public approval among supporters is hard to move.

Duterte's ethnic appeal has not gone unacknowledged by scholars and commentators (Cook and Salazar Reference Cook and Salazar2016; Maboloc Reference Maboloc2019; Escalona Reference Escalona2018). The fact that he is a Bisaya speaker from Mindanao is a core part of his political identity. However, when existing work invokes Duterte's ethnicity it is often seen as a marker of his outsider status, rather than as an explanatory variable in its own right. By contrast, we argue that ethnicity is core to Duterte's enduring appeal, and that ethnic divisions exert an independent effect on public evaluations of the president that is distinct from the more familiar insider vs. outsider or people vs. elite divide.

To empirically test the argument, we first demonstrate that Duterte did indeed marry populist rhetoric with clear and unambiguous ethnic appeals. We then show the effect of those appeals via a novel and nationally representative repeated cross-sectional dataset, combining 15 rounds of public opinion on Duterte's support with a variety of demographic questions. We obtained this data from Pulse Asia, one of the leading political polling firms in the Philippines. We operationalize ethnicity by identifying a respondent as being either of Tagalog or non-Tagalog ethnicity. Tagalog is the national language of the Philippines, but it is not the primary language of most Filipinos. Moreover, it is the primary language of the elites and the lingua franca of the national government. We conduct regression analysis with support for Duterte as the dependent variable and use a variety of potential explanatory variables, such as ethnicity, age (youth voters), income, gender, education, and urban versus rural voters, as independent variables.

Our results are consistent with the argument. First, we show that belonging to a non-Tagalog ethnicity leads to 8 percent greater support for Duterte. This result is significantly larger than any other explanatory factor in explaining support for Duterte. Second, we test the argument that ethnopopulism is associated with strong (versus mild) support. Consistent with our hypothesis we find that strong supporters are 19 percent more likely to be non-Tagalog ethnicity than weak supporters. Moreover, the coefficient on the ethnicity dummy is at least twice as large as any other potential explanation. We also show that the positive relationship between non-Tagalog ethnicity and Duterte support is consistent across time. Our results show this positive link is present in 14 of the 15 survey rounds. We then show that support is not being driven by all non-Tagalog languages; indeed, the ethnolinguistic dimension of Duterte support is driven most strongly by Bisaya ethnicity. This result implies that it is specifically Duterte's ethnopopulist appeal, and not some general insider–outsider dynamic, that is driving our results. We also argue that Duterte's high and robust levels of support are likely not being driven by social desirability bias or voters heavily weighting policy issues. Finally, we show that ethnic support does not drive the popularity of Noynoy Aquino, the president before Duterte, further corroborating our claim that the support dynamics we see are driven by Duterte's ethnopopulist appeal.

Our article adds to several diverse strands of literature. Most directly, we add to the literature on ethnopopulism (and populism more broadly) (Madrid Reference Madrid2008; Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Bieber Reference Bieber2018). Most of the literature on populism focuses on either conceptual definitions of populism or the factors that lead to the emergence of populist parties and leaders. This is true for the literature on populism in general and of ethnopopulism in particular. Our contribution is to use the ethnopopulist framework to build a theory of enduring populist support once they already hold office. In other words, we move from emergence to persistence. Furthermore, we also contribute the conceptual argument that the stickiness of ethnic identity makes populist support more stable than other forms of insider–outsider rhetoric that can be manipulated, supported, or undermined by policy. Finally, we add to the extant literature on Duterte's populism and the nature of populism in the Philippines (Arguelles Reference Arguelles2019; Arguelles Reference Arguelles2021; Curato Reference Curato2016; Curato Reference Curato2017; Kusaka Reference Kusaka2017; Maboloc Reference Maboloc2019).

Argument

In this section, we sketch an argument that links ethnopopulism with the robustness of support for populists and outline our scope conditions. The crux of the argument is simple—the ethnic component of populism is responsible for the enduring support of populists. By enduring and robust support we mean that public opinion for ethnopopulists remains stable over time. This sets ethnopopulists apart from other democratically elected leaders, whose support, in terms of public opinion polling, tends to go down throughout their tenure. The argument also distinguishes ethnopopulists from populists who make economic appeals. Since their popularity is primarily a function of economic benefits, populists who rely on economic appeals need to make economic concessions to their base to maintain their level of popularity. Ethnopopulists, as a function of their identity-based appeal, do not need to make such concessions. The argument fills a crucial gap in the literature—while a panoply of theories have been proposed to explain the rise of populism, theories of how populists persist in spite (or because of) their policy choices remain few and far between.

We begin by defining our terms. To begin with, we adopt what has become the standard definition of populism, as devised by Mudde (Reference Mudde2004). Populism is “an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite,’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the … general will of the people.” (Mudde Reference Mudde2004, 544). As other scholars have noted, populism is a thin ideology without clear policy implications (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Elchardus and Spruyt Reference Elchardus and Spruyt2016). As a result, it is often melded on to other ideologies in practice. In the case of ethnopopulism, traditional populist rhetoric is fused with ethnic appeals. This can take the form of exclusive nationalism—with populists combining the demagoguing of elites with the demagoguing of national outgroups (Jenne Reference Jenne2018). However, ethnopopulism can also take a more inclusive form, where parties and leaders seek to represent or give voice to the interests of certain ethnic groups, particularly those who have been historically disadvantaged, while avoiding overtly exclusionary rhetoric (Madrid Reference Madrid2008).

Ethnopopulist appeals have proven to be effective electoral strategies, particularly when populists are able to articulate “shared narratives of exclusion” that bind together those with a variety of different grievances (e.g. identity-based and economic) (Cheeseman and Larmer Reference Cheeseman and Larmer2015, 23).Footnote 5 Working in Latin America, Madrid (Reference Madrid2008) finds that ethnic appeals provide ethnopopulists with an advantage over economic populist leaders when it comes to garnering support. More important for our purposes, ethnopopulist appeals appear to be more durable than other forms of populism, as they are less likely to rely on fragile, personalistic linkages that are tied to the fate of a particular leader, or on the whims of the economy (Madrid Reference Madrid2008).

We build on this literature to construct an argument about the durability of ethnopopulist leaders and the nature of that durability. To begin with, we assume that identity politics is important enough to some voters such that they become the single issue voters base on, in this case, ethnicity, when such options are available on the ballot. The extant literature supports this assertion and suggests that at least for some voters, social identity drives political behavior, including how people respond to information and how they cast their votes (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Gottlieb, Kramon and McClendon2017). The importance of ethnic identity for at least some class of voters, gives ethnopopulists a stable base to build on. Where there are low levels of ethnic polarization and ethnic based parties rely on inclusive appeals, it is also possible for ethnonationalist leaders and parties to expand their support to people from outside a single ethnic category, even as their political entrepreneurship boosts the political salience of ethnic identities (Madrid Reference Madrid2008).

These broad coalitions, and hence public support, tend to be stable because ethnic identities, once salient, tend to endure over the short to medium term (Rosenthal and Feldman Reference Rosenthal and Shirley Feldman1992; Syed, Azmitia, and Phinney Reference Syed, Azmitia and Phinney2007). Citizens who support the ethnopopulist are less likely to withdraw their support based on economic or political events that may happen after the populist is elected. Since ethnopopulism taps into a core identity of many citizens, it produces such deep affinity among its supporters that they tend to provide overwhelmingly intense support. As such, public support among supporters remains deep and hard to move.

We do not mean to suggest that the ethnic affinities are the sole reason people support ethnopopulist leaders. Again, especially where ethnopopulists are inclusive, ethnically motivated voters may be joined by a coalition of other voters who are drawn in by other facets of populist rhetoric or the policy promises of ethnopopulists. Nor do we argue for a one-to-one mapping of ethnicity to political support. Not all members of an ethnic out-group will give the same weight to ethnic identity when deciding who to support. For some, identity appeals will have little or no salience, and they will instead base their votes on dimensions other than ethnicity. What we do argue is that the ethnic supporters are the strongest component of support for ethnopopulists and that their support is particularly durable. Thus, for a subset of voters, ethnic identity forms the basis of support. Because ethnic identity is relatively stable and is a core dimension that underpins political support, voters who support the populist because of shared ethnicity are not likely not to renege on their support regardless of what the populist does once in power.

Our ethnopopulist approach represents a novel contribution to the literature on Duterte and electoral politics in the Philippines. Existing work frames Philippines’ electoral politics through one of three common lenses: families, money politics, and populism. The first of these sees electoral politics as a battle among families, clans, and dynasties. At the local level families compete for office in barangay and municipal races, while family-based oligarchies vie for regional and national power.Footnote 6 The money politics approach focuses on the distribution of individual, household, and collective benefits by candidates in an effort to mobilize electoral support.Footnote 7 Finally, a number of scholars have looked at the role of populism in Philippine presidential politics, with some drawing a contrast between populist candidates/presidents (Joseph Estrada, Fernando Po Jr., Rodrigo Duterte) and “reformists” (Fidel Ramos, Noynoy Aquino, Leni Robredo).Footnote 8

Our account does not so much supplant as supplement these existing approaches. A focus on families and dynasties still helps us understand elections in many localities, and understand Duterte's path to power, but it can't explain why this politician from Davao appealed to voters in Cebu or Northern Luzon. Money politics (vote buying, patronage politics, etc.) remains the foundation of local and House contests, but it is generally not an effective strategy for national contests (president, vice-president, senate) (Hicken, Aspinall, and Weiss Reference Hicken, Aspinall and Weiss2019; Ravanilla and Hicken Reference Ravanilla and Hicken2022), and, unlike his predecessors, Duterte has notably “eschewed patronage-based political party building” and mobilization (Kasuya and Teehankee Reference Kasuya and Teehankee2020a, 69; Reference Kasuya and Teehankee2002b). Finally, we agree that Duterte's populism is an important part of his appeal—it helped him assemble a winning political coalition as we explain below. But populist appeals were not the only weapon in Duterte's arsenal. Inclusive ethnic appeals built the foundation of his support coalition and that ethnic foundation has proved incredibly stable.

It is, moreover, somewhat ironic that although Duterte has railed against the “oligarchy” and fashioned himself a true outsider, he is also a product of a generations-long political dynasty. His father was a mayor in the Visayas and a governor in Davao province. His cousin was mayor of Cebu city, one of the major cities in the Philippines. Moreover, many of his policies have been criticized as being inconsistent with the proclaimed goal of redistributing power away from the elites and towards the people. His most notorious policy, the Drug War, apart from being criticized on fundamental moral grounds, was also criticized for focusing on street level drug dealers and users, while letting drug suppliers roam free. A particularly egregious example of this occurred when Duterte's Department of Justice dropped drug charges against several high-profile suspected drug dealers, prompting sharp backlash among opposition and the media.Footnote 9 As is the case for many populists, there seems to be a gap between Duterte's rhetoric and assertions and the empirical reality. Still, while it seems obvious that Duterte has acted in ways consistent with the favoritism/clientelism that is the common explainer of Philippine political phenomena, these actions cannot explain high and enduring voter support.

Our argument yields a number of testable implications:

1. Ethnic appeals should be part of Duterte's appeals to voters.

2. Support for ethnopopulists should be more stable over time than support for other types of leaders, including other populists.

3. Ethnic affinities should predict support for ethnopopulists and should be stable over time.

4. Among the supporters of ethnopopulists, support should be strongest among ethnic voters.

It is important to outline the scope conditions of our argument. First, this is an argument about ethnopopulism, not populism more generally. Second, similar to that of Madrid (Reference Madrid2008), our argument applies to contexts where ethnicity is not a polarized issue and where ethnic identities are somewhat fluid. This opens the door for the types of ethnically based, but nonetheless inclusive appeals that enable the creation of broad, enduring ethnopopulist coalitions. Where there is ethnic polarization, we would expect to see more exclusive forms of ethnonationalism (Jenne Reference Jenne2018), which limit the appeal of the party/leader to voters outside of the ethnic group in question.

It is possible, of course, that we are wrong, that Durterte did not employ ethnic appeals, that support for ethnopopulists is not especially stable, or that the source of that stability does not lie with ethnically aligned voters, as we have hypothesized. If so, we would expect to find no evidence of ethnic rhetoric in his speeches, and to see null results in our empirical tests.

The first step in examining our theory is to establish that Duterte was indeed an ethnopopulist. If not, it is possible that it is not ethnic appeals in particular but appeals to political outsiders more generally that explains his enduring support. To make the case for Duterte as an ethnopopulist we turn now to a discussion of ethnicity and populism in the Philippines.

The case for Duterte as an ethnopopulist

Ethnicity, language, and region in the Philippines

The Philippines is home to a diversity of languages apart from Tagalog, its national language. The Americans made Tagalog the national language of the country at the onset of US colonization. However, native Tagalog speakers (and people thus people who identify as Tagalog) are minority in the Philippines—only 28.1 percent of the population. Non-Tagalog regional languages are still widely used today across the country.Footnote 10 These include Ilocano, mainly spoken in Northern Luzon; Kapampangan and Pangasinense, spoken in the Central Luzon; Bicolano, spoken in Southern Luzon; and finally Ilonggo (Hiligaynon), Waray and Cebuano, collectively referred to as Visayan or Bisaya, which are spoken in the Visayas and Mindanao regions (Blake Reference Blake1905). The fact that ethnic and language differences substantially overlap with regional divides means that regional identity is also a part of ethnic identity for many Filipinos.Footnote 11

As we will place a good deal of emphasis on the ethnic identity of Bisaya speakers, it is useful to say a bit more about this group. As mentioned, Bisaya encompasses several different related languages, the largest of which is Cebuano, which is spoken throughout the central (Visayas) and southern (Mindanao) regions of the Philippines. Colloquially, when people refer to the Bisaya language they are referring to Cebuano. With ~26 percent of the population Cebuano is second only to Tagalog (~32 percent) in the number of native speakers.Footnote 12 While Bisaya/Cebuano and Tagalog are related and share some cognates, they are not mutually intelligible. Despite their similar numbers, Tagalog speakers have generally been in a politically, economically and socially advantageous position relative to Bisaya speakers.

With such a diverse array of geographically concentrated languages in the Philippines, it is no surprise that Filipinos’ ethno-linguistic identities play a role in shaping political preferences and behavior. But while ethno-linguistic divisions are a salient feature of Philippines social and political life, the country has largely managed to avoid ethnic polarization. In part, this is due to the fact that most ethnic divisions are cross-cut by religion—86 percent of Filipinos are Catholics (Grzymala-Busse and Slater Reference Grzymala-Busse and Slater2018; Steinberg Reference Steinberg2018). But whatever the reason, while political polarization has been a recurring feature of Philippines politics, this polarization has not been based in or driven by ethnic divides (or religious, social, or class divides for that matter) (Arugay and Slater Reference Arugay and Slater2019). Thus, the Philippines corresponds nicely to what scholars argue is the ideal context for the development and success of inclusive ethnic appeals: namely, a lack of ethnic polarization. With low levels of ethnic polarization it is possible to strategically use ethnic appeals in ways that does not alienate, but rather unifies diverse ethnic bases into a larger coalition against a minority insider elite.Footnote 13

Duterte's ethnic appeals

How important were ethnic appeals to Duterte's mobilization strategy? If our argument is correct we should see evidence of the use of ethnic appeals in his rhetoric. But his strategic deployment of ethnic appeals has often been overshadowed by his flamboyant and controversial populist rhetoric as well as the framing of Duterte as an “outsider.” That said, we are certainly not the first to make note of Duterte's home region or his regular use of Bisaya on the campaign trail. But while these aforementioned logics are almost always mentioned as part of the profile of Duterte, explanations for his rise and success almost always avoid giving much role to ethnicity. For example, scholars attribute Duterte's success to his mobilization of an urban rural divide (Cook and Salazar Reference Cook and Salazar2016), his skillful populist rhetoric in the face of democratic disillusionment (Curato Reference Curato2017), his ability to appeal to the vulnerable, overlooked, or oppressed (Arguelles Reference Arguelles2019; Kusaka Reference Kusaka2017), his promise to bring law and order (Curato Reference Curato2016), or his ability to manage (or manufacture) crises (Arguelles Reference Arguelles2021). Maboloc (Reference Maboloc2019) and Escalona (Reference Escalona2018) are notable exceptions—each places ethnicity front and center in their narratives describing the rise of Duterte. Maboloc (Reference Maboloc2019) argues that Duterte's style is symbolic of Bisaya resistance to traditional centers of power, while Escalona (Reference Escalona2018) notes that Bisaya speakers, accustomed to being looked-down-upon, responded positively to his open use of the language in public.

In fact, Duterte is not fluent in the official language of the Philippines, Filipino (a form of Tagalog). He grew up in the city of Davao, located in the Mindanao Region, speaking Cebuano. On the campaign trail and as president, Duterte has given his speeches and interviews in a mixture of languages, relying heavily on Cebuano. For example, when Durterte administered the oath of allegiance (“Panaghiusa para sa Kalinaw,” which translates to “Unity for Peace” in Cebuano) to 700 former rebels in 2017, his speech was mostly Cebuano, with sprinklings of English and Tagalog.Footnote 14 His regular use of Cebuano sets him apart from previous Presidents, who conducted their speeches in either Tagalog or English. The fact that Duterte appealed to voters in his native tongue, we argue, was one of the main reasons why many Filipinos who spoke Cebuano and other Bisaya languages in the Visayas and Mindanao regions supported him.

One might reasonably counter that just because Duterte was Visayan and regularly used the language on the campaign trail doesn't necessarily mean he was using ethnic appeals. Perhaps Bisaya is merely the language he was most comfortable speaking and no more. Why should we believe that he intended to send an ethnic signal, and why should we think voters perceived his rhetoric as an ethnic appeal? To begin with, we can look at how his use of Bisayan was interpreted by his audiences. Escalona's analysis underscores the ethnic appeals inherent in his rhetorical strategy.

He chooses to speak the gutter Bisaya because he is targeting the Bisaya which now represents the masses. His gutter language is offensive, but it is effective … One of the reasons why he is loved by the Bisaya is that his accent represents the people who, through the language they speak and the accent they possess, are being mocked by non-speakers. Duterte speaking in Binisaya even in national TV is making a statement for the Bisaya people. (Escalona Reference Escalona2018)

We also have more direct evidence Duterte's explicit ethnic appeals. For example, in his first visit to the Visayas after declaring his candidacy for the 2016 election Duterte had this to say to a large crowd gathered in Cebu. In the speech he switches back and forth between English and Bisaya.

I am a Filipino. I love the Philippines because it is the land of my birth. It is the home of my people. The thing that ruins it is that, for the longest time, the government has been held by the Tagalogs. It's true! The way they look at their life, their dimensions, is Tagalog. It's always Manila. [The Visayas] haven't tasted except for Garcia who became president, that was a long time ago. Even in the distribution of famous Filipinos we're at a loss. And to think that there was someone here, a very brave warrior, who killed the first colonials. The one who killed the foreigner who wanted to steal our land, the idiot Magellan … The one who killed the first foreigner who bullied us, Magellan, is Lapu-Lapu. [But] look at these Manileños, [lists several famous Tagalog-speaking historical figures who are celebrated with national holidays]. Our own hero, the bravest and the strongest, the one who killed Magellan, doesn't even have a spot to honor Lapu-Lapu … That's why if I become president we will have a Lapu-Lapu day … It is a very great injustice.Footnote 15

Throughout the speech he repeatedly referenced his Visayan heritage, noting “[m]y roots are here” and “every time I am asked of my lineage, I tell them that I am Visayan.”Footnote 16 In a return to trip to Cebu in 2019 he tied his victory directly to his ability to win ethnic votes, stating:

As I have said before, the presidency is a gift from God. That opportunity shouldn't be wasted because not all Filipinos can be president. I never believed that I would win but you voted for me because I am Bisaya. That's the truth there.Footnote 17

Note that Duterte's rhetoric, while sometimes critical of Tagalogs’ dominance of government, was not exclusionary. He called for Visayans to take their deserved place at the table but did not dismiss other groups as legitimate actors in the political system nor advocate for their political exclusion. Duterte's relatively inclusive style of ethnopopulism allowed him to make inroads among other ethno-linguistic groups outside of Mindanao and the Visayas.Footnote 18 Some of these supporters may have found his status as an outsider, embodied by his language and ethnicity, as the central appeal. Others were attracted by his populist rhetoric or promises to bring law and order to the Philippines. Still others came to Duterte via more standard political alliances—for example, he did well among voters in the Ilocos region in Northern Luzon, where his history of support for Ferdinand Marcos won him supporters in the former dictator's homeland.Footnote 19 Still, there were limits to his appeal. For example, Duterte did not fare as well among Kapampangan speakers.

Duterte's populist appeal

We have endeavored to demonstrate that Duterte made explicit use of ethnic appeals, including his use of Bisaya, and these appeals played a crucial role in mobilizing supporters. But Duterte did more than just appeal to ethnicity. He fused his ethnic appeals with a populist rhetoric. There is wide consensus that Rodrigo Duterte is a populist president. This is most evident in Duterte's “anti-elite, pro-common people” rhetorical style. He has regularly threatened to dismantle the “elite.” For example, at a press conference in the first year of his Presidency, he stated: “The only way for deliverance of this country is to remove it from the clutches of the few people who hold the power and money.” At the same press conference he noted, with characteristic ebullience: “`If I die, if my plane crashes … I am very happy. You know why? … I dismantled the oligarchy that controls the economy of the Filipino people.”Footnote 20 While such assertions may be overstated, Duterte has indeed engaged in actions that can be construed as an attempt dismantle the established elite. The most glaring example of this is when he ordered the shutdown of news station ABS-CBN, the most viewed station in the country, which is also owned by the powerful Lopez political dynasty and some of his most powerful political opponents.

Duterte also excels at the “flaunting of the low,” a rhetorical strategy identified by Ostiguy (Reference Ostiguy2009) as a strategy of many populists. Rather than speaking in a careful, polished manner, he speaks in a way that sets him apart from the elite and portrays him as relatable to the people. He revels in combining coarse language with verbal belligerence. His language is colorful and often crude. His opponents are derided in combative and sometimes explicit terms, and include everyone from drug users to opponent politicians to the Pope. In short, he uses his language to help draw a line between the elite and the people, with himself as the leader.

His background and the circumstances under which he ran also bolster his populist bona fides. Duterte has fashioned himself as a political outsider, a mayor from Davao city in the Southern Philippines, a region often neglected by the national government. In a press conference early in his Presidency, he asserted as much: “You Manila people, don't be so judgmental … I am really dyed-in-the-wool from the province … they think Davao is a farm … the Manila people never invite me, they even say I know nothing about economics.”Footnote 21 This anti-elite rhetoric reflects an underlying truth: the interests of many people (and politicians) from the Southern Philippines have often been neglected and pushed aside in favor of the preferences of citizens in the capital city of Manila and its surrounding areas.

Finally, Duterte's claims to being a populist outsider are further supported by the results of the 2016 election that swept him to power and the institutional changes he put in place once in office. Although he won the Presidency with a plurality of 39 percent of the national vote, he is the only president in the post-Marcos era (1986 onwards) to have done so with practically no representation in the legislature and almost no allies among local mayors (Ravanilla, Sexton, and Haim Reference Ravanilla, Sexton and Haim2020). Moreover, once president, he appointed his allies from the Southern Philippines to top positions in the government, shifting government control from “Manila insiders” to “outsiders from the South.” To give two concrete examples—Carlos Dominguez, the Secretary of Finance and Duterte's former high school classmate, is a Davao businessman. Ronald Dela Rosa, formerly Davao's police chief, was appointed by Duterte as Chief of the entire Philippine National Police.

To summarize, as an ethnopopulist, Duterte has married inclusive ethnic appeals with the traditional rhetoric of populist politicians. The inclusive element of this brand of ethnopopulism is centered around four points: First, he frequently used ethnic appeals, including speaking in Bisaya, the major language of both the central and Southern Philippines, in a bid to build support among co-ethnics throughout the country. Second, Duterte framed himself as a “Son of the South” which encouraged citizens from the Southern Philippines (and other neglected regions) to rally around him. Third, in his populist rhetoric he juxtaposed himself against the Manila-insiders, making the rhetorical outgroup relatively small—confined to the capital and perhaps its surrounding regions. Finally, he used plainspoken language to make these points, often cursing and telling jokes, even during the president's State of the Union Address, usually an occasion of high formality.

It is clear, then, that Duterte relied on ethnic appeals in campaigning. But does ethnicity help explain his enduring support? To evaluate this question we now turn to the analysis of our public opinion data.

Sampling and variables

Sampling

The data used in this article comes from 15 rounds of nationally representative surveys conducted by Pulse Asia, a leading Philippine survey firm. Pulse Asia's quarterly surveys employ a multi-stage probability sampling. The first stage involves a decision on the sub-national areas and the distribution of the total sample for each of these areas. Across most of the quarterly surveys, the sub-national areas are the National Capital Region, the Balance of Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao.

In the second stage, the team randomly selects cities/municipalities in each of these sub-national areas. For the National Capital Region, all the cities and the single municipality are covered in the survey. For the other sub-national areas, a total of 15 cities/municipalities were allocated to the regions in proportion to household population size. Sample cities/municipalities were selected without replacement and with probability proportional to household population size.

At the third stage, the survey team randomly selects barangays (villages) in the probabilistically identified cities/municipalities. The allocated number of barangays were distributed among the sample cities/municipalities in such a way that each city/municipality was assigned a number of barangays roughly proportional to its household population size. However, each city/municipality was assigned at least one sample barangay. Sample barangays within each sample city/municipality were randomly selected without replacement.

For the fourth stage, within each sample barangay, five households were selected using interval sampling. In sample urban barangays, a random corner was identified, a random start generated, and every sixth household was sampled. In rural barangays, the designated starting point could be a school, the barangay captain's house, a church/chapel, or a barangay/municipal hall and every other household was sampled.

For the last stage, in each selected household, a respondent was randomly chosen from among household members who were 18 years of age and older, using a probability selection table. To ensure that half of the respondents were male and half were female, only male family members were pre-listed in the probability selection table of odd-numbered questionnaires while only female members were pre-listed for even-numbered questionnaires. In cases where there was no qualified respondent of a given gender, the interval sampling of households was continued until five sample respondents were identified.

Key dependent variables

Our main dependent variable is Support for Duterte. We code this variable equal as 1 if the respondent either strongly supports or somewhat supports Duterte, and 0 otherwise. The latter includes those who are uncertain or indifferent, or strongly or somewhat oppose him. Seventy-four percent of the sample across all surveys support Duterte.

We also use two alternative dependent variables. First, we create a Strong Support dummy variable equal to 1 if the respondent strongly supports Duterte, and 0 if the respondent somewhat supports Duterte. Second, we create an Oppose Duterte variable equal to 1 if the respondent either somewhat opposes or strongly opposes Duterte, and 0 otherwise. Note that this is not simply the inverse of the Support Duterte variable, since both strong support and somewhat support for Duterte, as well as undecided and indifferent respondents are coded as 0.

Key independent variables

The main independent variable of interest is our measure of ethnic identity. We use primary language spoken as our measure of ethnic identity. This measure—Non-Tagalog Primary Language—is equal to 1 if the respondent identifies a language other than Tagalog as his/her primary language, and 0 if the respondent's primary language is Tagalog. Roughly 60 percent of the sample identify a language other than Tagalog in the Non-Tagalog Primary Language category. To create this variable we draw on the variable in the Pulse Asia survey which identifies whether the respondent speaks one of the eight major Philippine languages—Tagalog, Ilocano, Pangasinense, Kapampangan, Bicolano, Illongo, Cebuano, Waray—as well as “Other Primary Language,” a catch-all term that encompasses many of the languages in the Southern Philippines, where Duterte was previously mayor.

The ethnolinguistic groups included in the survey are the recognized major language groups by the Commission on Philippine Languages. The only other major ethno-linguistic group (which is in reality still divided into many languages) that is not covered in the survey are the language groups of Muslim Mindanao.

Other independent variables

We include a variety of other independent variables that potentially explain Duterte support (and populist support more broadly). First, we include a gender variable equal to 1 if the respondent is male and 0 if the respondent is female. Conceptually, while gender is not necessarily related to populism, the cultural and social contexts under which populists operate may lead them to espouse either progressive or traditionalist views towards women, leading to either a defense of the (patriarchal) status quo or a more gender inclusive populist rhetoric (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2015). Specific to the Philippines, Duterte's rhetoric is highly patriarchal, and he often engages in blatant sexism towards women (Cabato Reference Cabato2019). Thus, gender differences may play a substantive role in support for Duterte.

Second, we include a dummy variable for young voters equal to 1 if the respondent is between the age of 18–24, and 0 otherwise. As with gender, the relationship between age and populist support is theoretically ambiguous. Still, in practice, the relationship between young voters and populism is particularly interesting. In some cases the youth may drive populist sentiment. Youth support for the left-wing Latin American populism of recent decades may be driven by their disappointment with the economic performance of their democratic regimes (Seligson Reference Seligson2007). In other cases, as in the United States, younger voters are more likely to oppose populists. The Duterte case is a priori ambiguous. On the one hand, youth support for Duterte has been institutionalized in the form of the “Duterte Youth.” The organization even won a seat in the House of Representatives.Footnote 22 On the other hand, students from the Philippines’ elite universities have openly protested various elements of the Duterte administration.Footnote 23

Third, we include a dummy variable for high-income earners equal to 1 if the respondent belongs to socioeconomic classes A, B, or C (which captures wealthy and middle-class voters) and 0 otherwise. These socioeconomic classes, in turn, are determined by an index. The index is a function of various measures of socioeconomic status, such as characteristics of the respondents’ home (for example the facilities they have) as well as household income.Footnote 24 The literature on the economic precursors of populism motivates the inclusion of the socioeconomic class variable. More specifically, poorer citizens who are “left behind” may feel compelled to support for a populist leader to counter the status quo that has failed to elevate them economically (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2016). There are also plausible reasons why income may be correlated with Duterte support. On the one hand, the victims of the War on Drugs were mostly the urban poor. In this sense, high income may be positively correlated with Duterte support as the poor are driven away by the War on Drugs. On the other hand, Duterte's plainspoken language and outsider status may appeal to lower income citizens.

Fourth, we include a dummy for educational attainment equal to 1 if the respondent is a college graduate and above, and 0 otherwise. The link between levels of education and support for populism is not well-studied. But in the case of the Philippines, local news usually reports students protesting against the administration. As stated previously, students at elite universities have openly dissented against Duterte's policies. Moreover, there is a large literature in social science that argues that education instils democratic ideas. According to Lipset, education “enables [citizens] to understand the need for norms of tolerance, restrains them from adhering to extremist and monistic doctrines, and increases their capacity to make rational electoral choices.” (Reference Lipset1959, 79) Regardless of the ultimate relationship between high levels of education and populism, enough qualitative evidence suggests that education needs to be adequately controlled for.Footnote 25

Fifth, we include a dummy equal to 1 if the respondent is from an urban municipality, and 0 if the respondent is from a rural municipality. Like the previous variables, the extant literature on the relationship between urbanization and populism is mixed. For example, Argentina's Kirchner had populist appeal with urban voters as a result of his export-promotion policies (Richardson Reference Richardson2009). On the other hand, rural voters were a significant base for the election of Donald Trump (Monnat and Brown Reference Monnat and Brown2017). Duterte's appeal with urban or rural voters has been less explored, and it is worth considering here.

Main results

This section empirically tests our central hypothesis: identity is a fundamental factor underlying Duterte's public support. In particular, we test whether respondents who identify with a non-Tagalog ethnicity are significantly more likely to support Duterte than respondents who claim a Tagalog ethnicity. We conduct a series of linear probability models to test our theory. The empirical specification is as follows:

Where Support it is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the respondent supports Duterte, and 0 otherwise. NonTagalog it is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the respondent's ethnicity is not Tagalog, and 0 if it is Tagalog. X it is a vector of demographic variables which represent competing potential explanations for Duterte's populist support—gender, age, education, class/income, and whether the respondent lives in an urban or rural area. ![]() $\varepsilon _{it}\;$is unobserved heterogeneity. All regressions use robust standard errors.

$\varepsilon _{it}\;$is unobserved heterogeneity. All regressions use robust standard errors.

The empirical result supports our first testable implication—β 1 is positive and statistically significant, which means that being from a non-Tagalog ethnicity is associated with a higher likelihood of supporting Duterte. Figure 2 presents coefficient plots on the full regression, including the main ethnicity variable and the other demographic variables. The results are with our argument. Being from a non-Tagalog ethnicity leads to, on average, an 8.1 percent marginal increase in support for Duterte. This result is significant at 99 percent confidence. The implication is straightforward—ethnicity plays a substantial role in Duterte support.

Figure 2. Determinants of support for Duterte

Note: The figure displays coefficient plots of a regression of support for President Duterte on various determinants of presidential support. Standard errors are calculated at 95 percent confidence.

The coefficient plots displayed in Figure 2 highlight the large substantive impact of ethnicity on Duterte support. The size of the Ethnicity coefficient is about 2.5 times larger than the second largest coefficient—whether the respondent is a youth voter or not. Of the control variables young voters, gender, and income are significantly different than zero—young voters and men are each more likely to support Duterte compared to older voters or women. High-income voters are also less likely to support Duterte. The remaining variables are not statistically significant and furthermore have small coefficient sizes. Overall, these results imply that other potential explanations for Duterte's high approval ratings: his appeal to older/more conservative voters, richer voters, or more highly educated voters do not have the same empirical support.

One potential concern is that the coefficient on ethnicity might hide high variation in how ethnic identity affects Duterte's public support. In other words, his support as a function of ethnicity may be changing over time. To address this concern we plot each coefficient, again using the above multivariate regression, for each survey round. Figure 3 presents the results. We see that, with the exception of a couple of rounds, ethnic identity is a strong predictor of Duterte's public support and is consistently so over time. Furthermore, across survey rounds, none of the other potential explanatory variables is consistently significant. A potential caveat is that the relationship between non-Tagalog identity and support is no longer significant in the very last survey, taken in September 2020. This is because Duterte's approval rating was at an all-time high of 91 percent, and thus there was not enough statistical variation in the data (too few respondents opposed Duterte) to generate a significant result.

Figure 3. Non-Tagalog ethnicity and Duterte support by survey

Note: The figure displays coefficient plots of a regression of support for President Duterte on non-Tagalog ethnicity for each survey round. The regression includes the other potential explanatory variables but they are not reported here. Standard errors are calculated at 95 percent confidence.

Intensive margin: Strong versus mild support

Our third testable implication posits that Duterte's ethnopopulism is exacerbated if we look at the degree (strong versus moderate) of support among his supports. That is, ethnic identity also correlates with a propensity to strongly support Duterte, as opposed to mild support. Put more plainly, strong support is associated with ethnic identity affiliation.

To test this implication we restrict our sample only to Duterte supporters, and employ the following empirical specification:

Where StrongSupport itis a variable equal to 1 if the respondent strongly supports Duterte, and 0 if the respondent mildly supports Duterte. The rest of the variables are similar to equation Y.

Figure 4 presents coefficient plots on the full regression, including the main ethnicity variable and the other demographic variables. The results are consistent with our argument. Being of a non-Tagalog ethnicity leads to, on average, a 19 percent marginal increase in strong support for Duterte. This result is significant at 99 percent confidence. This result is substantially larger than the previous result on the full sample, implying that identity plays an even larger role when we consider the degree of support, as supposed to support versus opposition, for Duterte.

Figure 4. Determinants of strong support for Duterte

Note: The figure displays coefficient plots of a regression of support for President Duterte on various determinants of strong presidential support. Standard errors are calculated at 95 percent confidence.

As with the previous result, we may again be concerned that the repeated cross-sectional results mask variation across different survey rounds. To address this concern we once again plot each coefficient, again using the above multivariate regression, for each survey round. Figure 5 presents the results. We see that, with the exception of a couple of rounds, ethnic identity is a very robust predictor of Duterte's strong support and is consistently so over time. The same caveat regarding the September 2020 result applies.

Figure 5. Non-Tagalog language and strong Duterte support by survey

Note: The figure displays coefficient plots of a regression of strong support for President Duterte on non-Tagalog ethnicity for each survey round. The regression includes the other potential explanatory variables but they are not reported here. Standard errors are calculated at 95 percent confidence.

Figure 6. Ethnicity breakdown of Duterte support

Note: The figure displays coefficient plots of a regression of support for President Duterte by various major ethnolinguistic groups. Standard errors are calculated at 95 percent confidence.

Refining the ethnic identity argument

In this section we provide further supporting evidence for our identity populism argument. A natural counterargument would be that not all “non-Tagalog ethnics” are alike. Indeed, subsuming all non-Tagalogs into a groups masks important variation that may help support our argument.

As our argument posits that citizens of non-Tagalog ethnicity identify with Duterte and consider him “one of them” as a result a result of his explicit and implicit ethnic appeals, we expect that the ethnic groups from the Central and Southern Philippines will be driving support for Duterte. Ethnic minorities from the Northern Philippines will not be driving the support for Duterte because, while they are ethnic minorities, they do not speak the language that Duterte speaks nor do they come from the same part of the country that Duterte comes from. Specifically, we expect support for Duterte to be driven by the Illongo, Cebuano, Waray, and “Other ethnicity,” corresponding to the major ethnic group in the Central and Southern Philippines.

Examining the results from Figure 5, this is exactly what we see. Duterte support is positively and significantly related to identifying as Illongo, Cebuano, Waray, or “Other Ethnicity.” Moreover, many of the minority ethnic groups from the North—Bicolano, Kapampangan—actually are negatively related to Duterte support. The coefficient on Pangasinense, another ethnic group from the North, is positive but not statistically significant. This further corroborates the argument that ethnic attachment to Duterte, not in-group/out-group dynamics more generally, are the relevant explanation for our results.Footnote 26

Finally, in order to better distinguish the power of ethnicity versus purely regional appeals we examine within regional variation by language. Of course, when we divide the sample population by region we lose a lot of power (for example there are not enough Tagalog speakers in the Visayas for us to be able to get any empirical leverage). However, the sample from Luzon provides us with a sufficient number of Bisaya speakers to conduct an analysis, although the number of respondents is still below what would be ideal. Even so, we rerun the main model looking at the differences in support for Duterte between Tagalog and Bisaya speakers within Luzon. Not surprisingly, the smaller sample increases our standard errors, but the main findings not only still hold but are strongly supported. Bisaya speakers in Luzon are much more likely to support Duterte compared to non-Bisaya speakers—significant at the 99 percent confidence level (see the Appendix Figure 1 for the full results). This finding suggests that ethnic identity, over and above purely regional appeals, is driving our results.

Alternative explanations

In this section we explore potential alternative explanations for Duterte's populist support. Three alternative explanations stand out. First, there is the possibility that the patterns we see in the data do not reflect sincere preferences, but, rather, reflect some sort of preference falsification or social desirability bias. A second possible alternative is that support may simply be a function of the rational policy considerations of respondents. Duterte may have a high and steady approval rating because people approve of his policies. Third, perhaps it is the case that co-ethnic/co-linguistic voting is simply be endemic to Philippine politics—meaning what we describe as unique to Duterte is merely part and parcel of Philippine politics. We assess the plausibility of each of these alternatives below.

Social desirability bias

A potential alternative explanation for our findings is that they are driven by social desirability bias (SDB)—respondents may report answers that they deem are socially acceptable (as opposed to their true beliefs), leading to the over-reporting of desirable behaviors and the under-reporting of undesirable behaviors (Bradburn et al. Reference Bradburn, Sudman, Blair and Stocking1978). In the context of this paper social desirability may confound our results int two ways. First, it may lead to over-reporting of support for Duterte, as respondents who privately do not support Duterte respond in the survey that they support him in order to appear socially acceptable. Second, SDB may affect different subgroups of the sample in different ways. For example, SDB may lead to greater levels of over-reporting of Duterte support among ethnicities where he is relatively popular, such as Cebuano speakers, and lead to lower levels of over-reporting among ethnicities where he is relatively unpopular, such as Kapampangan and Bicolano. The effect of this type of SDB would be to exaggerate the difference in levels of support between ethnicities, such that the difference between subgroups appears larger than it is.

So how serious a problem is SDB? A recent working paper by Kasuya, Miwa, and Holmes (Reference Kasuya, Miwa and Holmes2022) suggests SDB could be a significant challenge. Based on a 2021 survey experiment, they argue that SDB could be inflating survey estimates of Duterte support by as much as 39 percentage points. However, this incredibly high estimate falls to 4 to 15 percentage points once the likelihood of non-strategic misreporting is taken into account via a “placebo” list experiment. This seems to us like a much more plausible number and, if accurate, would still place Duterte's approval at a level far above any of his predecessor's, and would still leave us with the question of why that approval rating (SDB adjusted or no) has remained so stable over time.Footnote 27

There are other reasons to be sanguine about the issue of SDB. First, if we believed SDB was driving a large number of respondents to feign support for Duterte, we would expect the prevalence of SDB to increase over Duterte's presidency as he settles into office, consolidates his power, and proves willing and able to attack his opponents. However, looking across Pulse Asia surveys, the rate of non-response, which tends to be correlated with SDB, has remained virtually unchanged over Duterte's presidency (Kasuya, Miwa, and Holmes Reference Kasuya, Miwa and Holmes2022). Second, we are reassured that while Kasuya and colleagues find some evidence of SDB, they do not find any evidence that SDB is driven by fear or intimidation, nor is it correlated with social media use. Instead, the best predictors of SDB are neighborhood band-wagoning effects—anti-Duterte individuals in pro-Duterte areas seem more likely to prevaricate when asked if they support Duterte (ibid.). But there is little reason to expect that such effects would be unique to Duterte, so they can't account for why his approval has been higher than previous presidents, nor does it explain why that approval has remained so steady.

We also note that it is individuals who are opposed to Duterte who should feel the greatest pressure to be untruthful, and that should make it more difficult to detect differences between supporters and non-supporters, biasing against our results. In addition, the gaps between ethnic groups and between supporters and non-supporters are so large that the level of SDB would need to be extremely large in order to wash away the effects we observe. For example, the marginal difference in SDB between Cebuano and Bicolano would have to be over 30 percentage points to nullify the statistically higher support for Duterte from Cebuanos over Bicolanos. In other words, the SDB leading to inflated support for Duterte among Cebuanos would have to be substantially larger than the SDB leading to over-reporting of Duterte support among Bicolanos. This is a very unlikely outcome, and there does not seem, to us, to be a logic that can justify such a large gap. Finally, Kasuya, Miwa, and Holmes find no evidence of SDB among respondents from the A, B and C classes. When we confine our analysis to just these voters (Appendix Table 2), our main results hold, and ethnicity is still a significant factor in explaining Duterte support. In short, while some degree of SDB may indeed be present, we believe that it does not override our main findings.

Policy considerations

A second alternative explanation is that Duterte's support is driven by policy considerations. This alternative logic is straightforward: respondents consistently support his policies, and as such, always support him. While theoretically plausible, there are reasons to believe that this is not the case.Footnote 28 First, Duterte's popularity reached a new high of 91 percent in September 2020, in spite of both a global pandemic and a recession. Indeed, the surge in his popularity coincided with a contraction of –16.9 percent and –11.5 percent in the second and third quarters of 2020, respectively.Footnote 29 Furthermore, his Presidency presided over a massive corruption scandal involving PhilHealth, the country's public health insurance provider. The scandal centered around an alleged misuse of almost 300 million USD worth of funds.Footnote 30

In addition to a public health crisis, a recession, and corruption allegations, the Duterte government has also been criticized for attacks on the press and his political opponents. For example, Duterte's administration blocked the franchise renewal of ABS-CBN, the country's largest broadcast network,Footnote 31 and filed a case against Rappler, an opposition news and opinion outlet, and its CEO Maria Ressa on the grounds of cyberlibel.Footnote 32 He also imprisoned opposition Senator Leila de Lima for allegedly abetting the illegal drug trade.Footnote 33 The selective attack on political opponents underscores the political nature of the persecution.

Furthermore, to test if policy considerations are driving our main results, we run a similar analysis, including a variable that asks respondents whether they approve of Duterte's management of the economy. If we expect policy considerations to be driving our results, then we should expect the coefficient on ethnicity to no longer be significant. This is not the case. Indeed, the coefficient on non-Tagalog ethnicity (displayed in Appendix Table 3) remains positive and significant.

Ethnic populism as central to Philippine politics

Another potential alternative explanation is that co-ethnic/co-linguistic voting may simply be endemic to Philippine politics. In other words, voting along co-ethnic lines may be the pattern for every president, not just Duterte. Duterte would then be the norm and not the exception. This goes against our argument, which claims that it is Duterte's ethnopopulist appeal that leads to ethnicity-based voting. To test this alternative theory we analyze the determinants of support for the previous President Noynoy Aquino. President Aquino is a relevant case to consider because his tenure immediately preceded Duterte's. Thus, if ethnic differences are endemic to Philippine politics (or are a product of more recent Philippine events), and not specific to Duterte, then we should find that ethnic differences are a relevant predictor of Aquino support as well. By contrast, if our theory is correct, we should see no statistical correlation between ethnicity and support for President Aquino. More precisely, the Aquinos are Tagalogs from Tarlac; therefore, to corroborate the argument that ethnic populism is not central to Philippine politics, but rather a particular artifact of Duterte's ethnopopulist appeal, we should find no statistical relationship between a Tagalog ethnicity and support for Noynoy Aquino. And in fact, this is what we see. Appendix Figure 4 displays the results. Identifying as having a non-Tagalog ethnicity does not lead to higher (or lower) levels of support for President Aquino. The converse is also true: identifying as Tagalog does not lead to more support for the president. This result is therefore consistent with a prediction of our theory: Duterte is unique among Philippine presidents and it is his ethnopopulist appeal that drives our core results.

Conclusion

This article attempts to explain why ethnopopulist support is strong and stable across time, distinguishing such populists from both their non-populist counterparts and populists who rely on economic appeals, as both tend to lose support over time. We explore this question by examining the support of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte. We claim that Duterte's strong and stable support is in part a product of his ethnopopulist appeal. Consistent with this argument we find that a) Duterte relied on ethnic appeals, and b) that identifying as having a non-Tagalog ethnicity is a positive and significant determinant of support for Duterte. The latter is true even when accounting for other potential factors, such as income, urban–rural divides, gender, and education. Moreover, this result is nationally representative and consistent over time. We also show that this result is unique to Duterte. Former Philippine President Noynoy Aquino did not have similar ethnic bases of support.

The results of this study lead naturally to future research. Most directly, it would be interesting to examine whether we see similar dynamics in other settings. To what extent and under what conditions does our claim—that the support for ethnopopulists tends to be more stable over time—travel? With respect to the Philippines, it would also be interesting to consider whether ethnopopulist appeal can be inherited or transferred. Duterte's daughter, Sara, successfully ran as vice-president in 2022, running on a ticket with Bongbong Marcos. Is her appeal also based on ethnic affinities? To what extent does ethnically based support transfer to her running mate? Continued work on such issues will shed further light on the dynamics of support for populist leader.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare none.

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1. Determinants of Support for Duterte (Bisaya Speakers)

Note: The figure displays coefficient plots of a regression of support for President Duterte on various determinants of presidential support. The sample is restricted to respondents from Luzon. Standard errors are calculated at 95 percent confidence.

Appendix Figure 2. Determinants of Support for Duterte (Class ABC Only)

Note: The figure displays coefficient plots of a regression of support for President Duterte on various determinants of presidential support. The sample is restricted to income brackets A, B, and C. Standard errors are calculated at 95 percent confidence.

Appendix Figure 3. Determinants of Support for Duterte (Including Approval of the Economy Variable)

Note: The figure displays coefficient plots of a regression of support for President Duterte on various determinants of presidential support. Standard errors are calculated at 95 percent confidence.

Appendix Figure 4. Determinants of Support for Aquino

Note: The figure displays coefficient plots of a regression of support for President Aquino on various determinants of strong presidential support. Standard errors are calculated at 95 percent confidence.