1 Introduction

The endowment effect, a term coined by Thaler (1980), is a well-documented phenomenon in the research field of judgment and decision making, which refers to a tendency that individuals overvalue items belonging to them relative to those not regarded as their endowments. Subsequent research has found that the effect cannot be explained away by income effect and is inconsistent with the Coase theorem – one of basic principles in the standard economic theories (Reference CoaseCoase, 1960; Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and ThalerKahneman, Knetsch & Thaler, 1990). The endowment effect is important in several fields, such as policy, economics, marketing, law, and psychology (Reference Morewedge and GiblinMorewedge & Giblin, 2015).

The main paradigms used in research on the endowment effect are the exchange paradigm and the valuation paradigm (Reference Morewedge and GiblinMorewedge & Giblin, 2015). In the exchange paradigm (Reference KnetschKnetsch, 1989), subjects were endowed with one of two items randomly and allowed to exchange with each other. The exchanging rate, which is usually lower than 50%, reveals the existence of the endowment effect. In the valuation paradigm (Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and ThalerKahneman et al., 1990), each subject was assigned a role as either a buyer or a seller and is asked to offer prices for items, i.e., willingness-to-pay (WTP) and willingness-to-accept (WTA). The endowment effect is manifest by WTA exceeding WTP (Reference Ericson, Fuster, Arrow and BresnahanEricson & Fuster, 2014). The discrepancy between WTA and WTP can be used as an index of individual differences in the effect (Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and ThalerKahneman et al., 1990).

The endowment effect is one of the most robust findings in the area of decision-making. Various kinds of items have been used in laboratory experiments, e.g., coffee mugs, candy bars and lotteries (Reference Bar-Hillel and NeterBar-Hillel & Neter, 1996; Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and ThalerKahneman et al., 1990; Reference Kleber, Dickert and BetschKleber, Dickert & Betsch, 2013; Reference KnetschKnetsch, 1989; Reference Pachur and ScheibehennePachur & Scheibehenne, 2012). Several theories were used to explain this phenomenon, such as status quo bias (Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and ThalerKahneman, Knetsch & Thaler, 1991; Reference Samuelson and ZeckhauserSamuelson & Zeckhauser, 1988), loss aversion (Reference Kahneman and TverskyKahneman & Tversky, 1979; Reference Tversky and KahnemanTversky & Kahneman, 1991), psychological ownership (Reference Morewedge, Shu, Gilbert and WilsonMorewedge, Shu, Gilbert & Wilson, 2009; Reference Reb and ConnollyReb & Connolly, 2007), biased information processing (Reference Ashby, Dickert and GlocknerAshby, Dickert & Glockner, 2012) and so on (Reference Morewedge and GiblinMorewedge & Giblin, 2015).

It is well established that dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) can catalyze the conversion of dopamine (DA) to norepinephrine (NE) (Reference Zabetian, Anderson, Buxbaum, Elston, Ichinose, Nagatsu and …CubellsZabetian et al., 2001). DBH localized in catecholamine-containing vesicles of adrenergic and noradrenergic neurons in human brain stem, including medulla and pons (concentrated in nucleus locus coeruleus and nucleus subcoeruleus; Reference Kemper, Oconnor and WestlundKemper, Oconnor & Westlund, 1987). DBH activity levels, measured in human plasma, vary widely among people (Reference Weinshilboum, Raymond, Elveback and WeidmanWeinshilboum, Raymond, Elveback & Weidman, 1973) and were partially determined by genetics (Reference Oxenstierna, Edman, Iselius, Oreland, Ross and SedvallOxenstierna et al., 1986; Reference Ross, Wetterberg and MyrhedRoss, Wetterberg & Myrhed, 1973; Reference Weinshilboum, Raymond, Elveback and WeidmanWeinshilboum et al., 1973). The DBH gene, located on chromosome 9q34 (Reference Craig, Buckle, Lamouroux, Mallet and CraigCraig, Buckle, Lamouroux, Mallet & Craig, 1988), is composed of 12 exons and comprises approximately 23 kb (Reference Kobayashi, Kurosawa, Fujita and NagatsuKobayashi, Kurosawa, Fujita & Nagatsu, 1989). The rs1611115(–1021C/T or C–1021T) of DBH gene is a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), locating 1,021 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site in the 5’-flanking region, and accounts for 35%–52% of the total variation in DBH activity in samples from African American, European American, and Japanese populations (Reference Zabetian, Anderson, Buxbaum, Elston, Ichinose, Nagatsu and …CubellsZabetian et al., 2001). According to previous studies, the homozygote of T allele is associated with the lowest DBH enzymatic activity, CT with intermediate activity, and CC genotype with the highest activity (Reference Zabetian, Anderson, Buxbaum, Elston, Ichinose, Nagatsu and …CubellsZabetian et al., 2001).

In a study on the relation between rs1611115 and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Barrie and colleagues have found that T-carriers showed higher Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) social scores and Restrictive/Repetitive Behavior scores (Reference Barrie, Pinsonneault, Sadee, Hollway, Handen, Smith and …AmanBarrie et al., 2018). This study suggests that T-carriers may have difficulty in interacting with others and making a change, which may result in a stronger tendency of avoiding trading and attaching to the status quo, and thus a stronger endowment effect.

Taken together, compared with people with a CC genotype, individuals with a T allele in DBH rs1611115 polymorphism are associated with ASD, having difficulty in social interaction and being unwilling to make a change. This may cause these T carriers to have a stronger tendency to avoid trading and a stronger attachment to the status quo, and thus to exhibit stronger endowment effects.

2 Methods and materials

2.1 Subjects

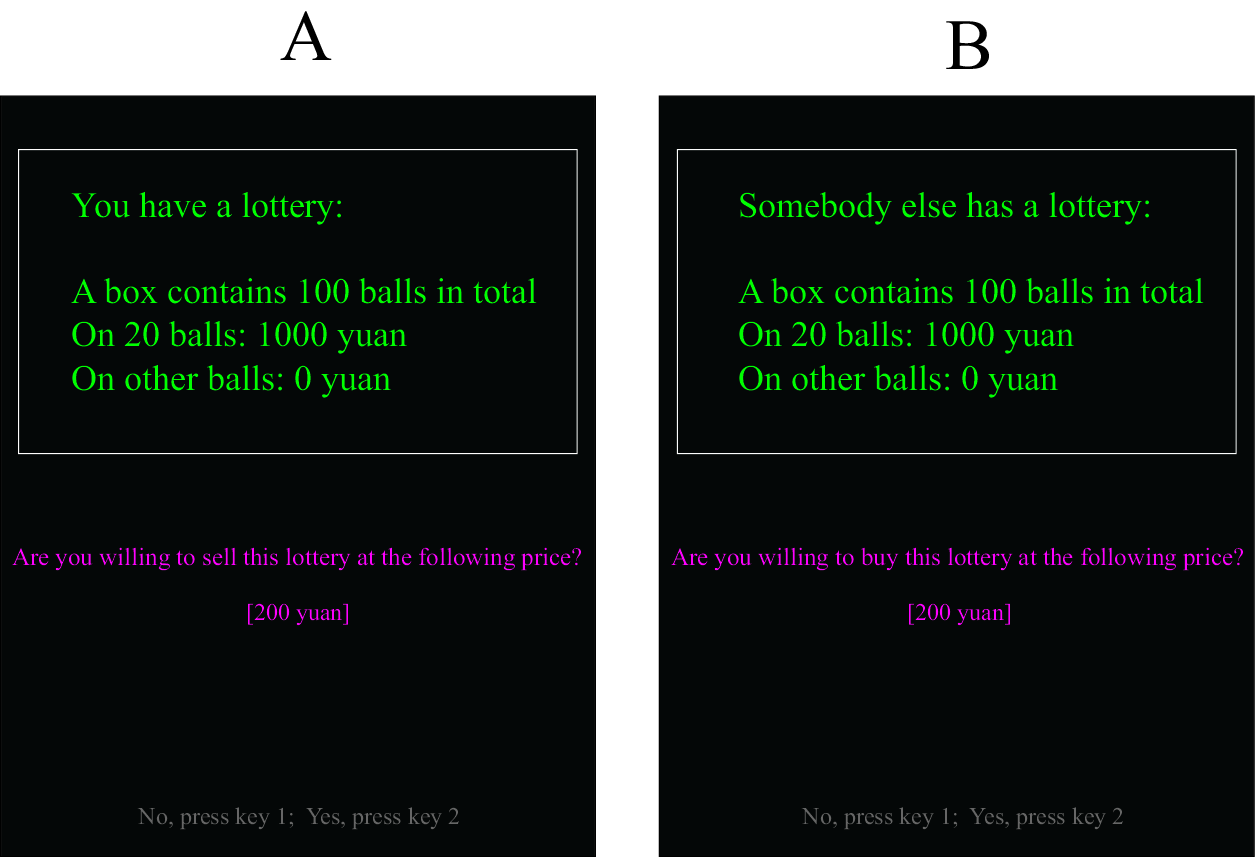

In total, 369 healthy undergraduates (113 males, 256 females; Mean age = 19.77, SD = 1.01) both completed an experimental task of endowment effect and were successfully genotyped for the rs1611115 polymorphism of DBH gene. They all provided written informed consent and were paid for their participation. The subjects were Han Chinese undergraduates (not majoring in arts, music, sports or psychology) at Southwest University in Chongqing City, China. The experimental materials presented to them were in Chinese, but were translated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A question in a selling trial (A) and a question in a buying trial (B).

To acquire data of high quality, the subjects were run in small groups consisting of up to 9 subjects. For obtaining saliva, we asked each of them to wash their mouths two hours ahead of saliva providing and neither eat food nor drink water during these two hours. This was to ensure that there were enough their own cells in their saliva.

2.2 Genotyping

For the rs1611115, the genotypes were determined by the Mass Array system (Agena iPLEX assay, San Diego, United States). First, approximately 10-20ng of genomic DNA was isolated from saliva samples. The polymerize chain reaction (PCR) primers used in the study were: ACGTTGGATGAAGCAGAATGTCCTGAAGGC and ACGTTGGATGTCAGTCTCACCACGGCACCT. The sample DNA was amplified by a multiplex PCR reaction, then the obtained products were used for locus-specific single-base extension reaction. Unextended primers used in the study were gtaCTCCTGTCCTCTCCC. At last, the resulting products were desalted and transferred to a 384-element SpectroCHIP array. The alleles were discriminated by mass spectrometry (Agena, San Diego, United States). rs1611115 genotype was coded as a categorical variable (C/C, C/T and T/T) for the subsequent analysis.

2.3 Experimental task

This experiment contained 3 stages in order: instructions, practice and formal sections. At the end of the instructions, the subjects could choose to move on or to re-read the instructions. At the end of the practice, the subjects could choose to move on or to re-read the instruction and re-do the practice. This design was to ensure that the subjects really understood the task before entering the formal section.

The practice and formal section respectively contained 2 and 22 trials, which all had the same structure. The practice contained a buying trial and a selling trial. In the formal section, the trials were composed in the following way: 2 roles (buyer vs seller) × 11 probabilities of winning 1000 yuan (1%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 99%). Therefore, each trial was about selling or buying a lottery with some probability. The order of these 22 trials was randomized for each subject. At the beginning of each trial, a screen reminded that a new trial was starting.

Each trial contained 6 questions. Questions within a trial involved the same lottery but different prices. Subjects were asked whether they would like to sell or buy the same lottery at a price and then another price. They could take as much time as they liked to answer each question. Figure 1 illustrates a question in a selling trial and a question in a buying trial. The prices within a trial were set in the following way. The 1st price was the expected value of the lottery in this trial, i.e., the probability × 1000 yuan. Each subject had to indicate whether he rejected or accepted this price by pressing 1 or 2 with his index or middle finger of his right hand. The next price was the average of the best rejected price and the worst accepted price up to that moment. The average price was rounded to an integer for presentation to subjects and further computer calculation. The initial best rejected price and worst accepted price were respectively set as 0 and 1000 yuan in selling trials, and 1000 and 0 yuan in buying trials.

Subjects got only a plain fee for their participation.Footnote 1 The outcomes were not revealed to the subjects lest the revealed outcomes influenced the responses to the next trials. Nevertheless, we instructed each subject to imagine that he encountered these questions in reality, and to earnestly and honestly answer questions throughout.

After a subject finished 6 questions within a trial, the best rejected price and the worst accepted price became quite close. The computer calculated the average of these two prices as the equivalent price of that lottery. In this way, for each subject, we could get equivalent prices for each lottery in selling and buying conditions. In other words, we could get buying price (WTP) and selling price (WTA) for each of 11 lotteries.

3 Results

3.1 Genotype frequencies

Among 369 subjects, 261 (70.73%) were C allele homozygotes (C/C), 99 (26.83%) were heterozygotes (C/T) and 9 (2.44%) were homozygotes of the T allele (T/T). The genotype frequencies did not deviate from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (χ2 = 0.01, p = .92). Given that the sample size of T/T genotype was too small (9 subjects), we omitted this genotype from further analysis and focused on the more reliable contrast between CC and CT. We therefore still had 360 subjects.

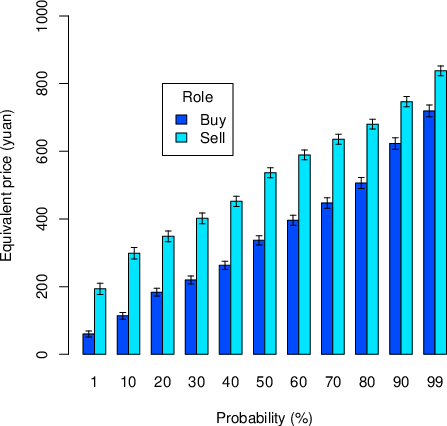

3.2 Behavioral results

Figure 2 presents the average equivalent price for each probability and role. We performed a repeated-measurement ANOVA with the dependent variable being the equivalent price, and the independent variables being role (buyer vs seller) and probability (from 1% to 99%). The main effect of probability was significant: F(10, 359) = 565.29, p < .0001, η2 = .61. The main effect of role was significant: F(1, 359) = 134.57, p < .0001, η2 = .27. The probability × role interaction was also significant: F(10, 359) = 3.38, p = .001, η2 = .01.

Figure 2: The equivalent price (EP) for each probability and role. Please note that EP for selling is WTA and EP for buying is WTP. Error bars represents ± 2 SE.

3.3 The influence of rs1611115 on the endowment effect

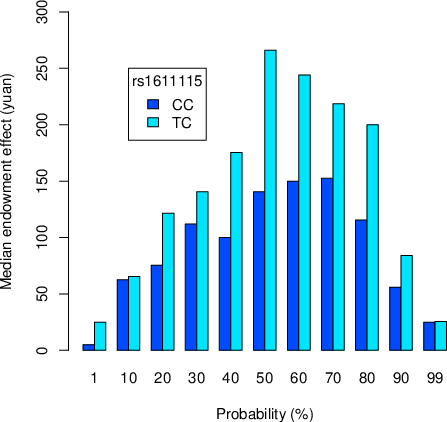

According to the definition of the endowment effect, we calculated the effect as WTA−WTP at each probability for each subject. Figure 3 and Figure 4 respectively present the median and mean endowment effect for each probability and genotype.

Figure 3: Median endowment effect at each probability for each genotype.

Figure 4: Mean endowment effect at each probability for each genotype.

To avoid excessive effects of extreme subjects, we compared subjects’ medians rather than their means. We firstly calculated each subject’s endowment effect as the average of his endowment effects at all probabilities. We then performed an independent-sample median test with the dependent variable being each subject’s endowment effect and independent variable being genotype. A significant effect of DBH rs1611115 polymorphism on the endowment effect was found (χ2(1) = 6.74, p = .009, n = 360). The grand median (GM) = 136.32. For the CC genotype, 119/142 subjects had endowment effects higher/lower than GM; for the CT genotype, 61/38 subjects had endowment effects higher/lower than GM.Footnote 2

We also performed a repeated-measurement ANOVA with the dependent variable being each subject’s endowment effect at each probability, and the independent variables being genotype (CC vs CT) and probability (from 1% to 99%). The main effect of genotype was significant (F(1, 358) = 4.46, p = .035). The main effect of probability was significant (F(10, 358) = 2.93, p = .003). The probability × genotype interaction was not significant (F(10, 358) = .89, p > .05).Footnote 3

4 Discussion

In our behavioral results, we observed the existence of the endowment effect: The selling prices were significantly higher than buying prices, showing the discrepancy between WTA and WTP. It is consistent with previous findings that the endowment effect is a robust phenomenon (Reference Ericson, Fuster, Arrow and BresnahanEricson & Fuster, 2014; Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and ThalerKahneman et al., 1990; Reference ThalerThaler, 1980). We expected that the endowment effect can be influenced by DBH rs1611115. This expectation was supported by the gene results: T-carriers (i.e., subjects with CT genotype in this study) demonstrated greater endowment effect, compared with CC-genotype subjects.

Previous research revealed that compared with the CC genotype, the T allele in DBH rs1611115 polymorphism is associated with ASD, difficulty in social interaction behaviors (Reference Barrie, Pinsonneault, Sadee, Hollway, Handen, Smith and …AmanBarrie et al., 2018) and unwillingness to make a change. Therefore, these T carriers may be more inclined to resist trading and more attached to the status quo, and thus to exhibit a stronger endowment effect.

An alternative explanation involves empathy. First, a study on the relation between rs1611115 and empathy found that subjects with CC genotype showed greater empathetic ability than T-carriers (Reference Gong, Liu, Li and ZhouGong, Liu, Li & Zhou, 2014). Second, given that empathy is an ability of perspective-taking (Reference O’Brien, Konrath, Gruehn and HagenO’Brien, Konrath, Gruehn & Hagen, 2013), subjects with CC genotype, as a buyer or a seller, can therefore better understand the perspective of the other role, relative to CT-carriers. Further, according to biased information processing, the endowment effect stems from different perspectives of buyers and sellers, for example, sellers focus more on positive features while buyers focus more on negative features of trading items (Reference Morewedge and GiblinMorewedge & Giblin, 2015). Therefore, relative to CT carriers, CC carriers, having higher empathetic ability, could better put themselves in the shoes of the other role, thus reducing the discrepancy between two roles in the information processing, and showing a weaker endowment effect.

Another alternative explanation involves loss aversion. (1) Relative to other genotypes, CC genotype of rs1611115 is associated with higher DBH enzymatic activity and thus higher norepinephrine level. Actually, CC-carriers of rs1611115 had heart rates statistically higher than T-carriers (Reference Isaza M, Valencia C, Ríos G, López B, Giraldo O and Quiceno GIsaza M et al., 2015). (2) The following observation and studies suggest a relation between higher norepinephrine level and lower loss sensitivity: (a) Urgency situations (e.g., one sees a poisonous snake near him), can increase norepinephrine, and decrease loss sensitivity (e.g., he may throw away any valuable objects in his hands and run away). (b) On the one hand, in response to physical or psychological stress, human can have a rapid release of norepinephrine through the sympathetic nervous system to restore homeostasis (Reference Margittai, Nave, Van Wingerden, Schnitzler, Schwabe and KalenscherMargittai et al., 2018). On the other hand, some studies have reported that stress leads to decreased loss sensitivity (Reference Pabst, Brand and WolfPabst, Brand & Wolf, 2013a, 2013b). (3) One theory of endowment effect is loss aversion (Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and ThalerKahneman et al., 1991), implying that lower loss aversion relates to a lower endowment effect. Taken together, it is comprehensible that CC genotype of rs1611115 is associated with a lower endowment effect, as revealed in this study.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study provides the first direct evidence for a gene contribution to the endowment effect. Our findings suggest that even a single-nucleotide polymorphism can remarkably influence complex human market activities. Our findings also suggest that the endowment effect origins at least partially from nature rather than completely from nurture. However, we still do not know exactly how DBH rs1611115 polymorphism influences the endowment effect, which calls for further investigation in the future.