Introduction and Motivation

In her work, “Black ethnics: Race, immigration, and the pursuit of the American dream” Greer (Reference Greer2013) argues that Black immigrants in the United States may experience discrimination that has nothing to do with their immigration status but rather their racial identity. Meanwhile, existing research shows that although Black Americans may experience discrimination because of their racial identity (Feagin and Bennefield Reference Feagin and Bennefield2014), African immigrants living in the United States may experience discrimination not only because of their race but also because they are foreigners (Yi and Museus Reference Yi and Museus2015). This presupposes that racial minorities living in America may experience discrimination that intersects their racial identity as well as their nationalities of origin. Using intersectional analysis, this paper investigates the experiences of Nigerian immigrants in the United States to understand how structural and social integration in the country produces intersecting experiences of discrimination.

The study is relevant to current discourses on race/ethnicity and nationalities of origin because the Nigerian diaspora in the United States is one of the fastest-growing immigrant groups of African origin (MPI 2015). Studies have shown that the Nigerian diaspora is arguably the largest sub-Saharan African population in the United States (Anderson Reference Anderson2017) with a population of 390,000 in 2019 (Oyebamiji and Adekoye Reference Oyebamiji and Adekoye2019), compared with 25,000 in 1980 (Camarota and Zeigler Reference Camarota and Zeigler2021, November 2). In addition to their large population, the Nigerian diaspora occupies a unique position within the racialized American society, where they are viewed as a “model minority” because their educational and professional achievements exceed those of other ethno-racial groups, including Whites (Ajobaju Reference Ajobaju2021; Hsu Reference Hsu2015).Footnote 1 , Footnote 2 Nevertheless, Nigerian immigrants in the United States continue to experience anti-Black xenophobia despite their seemingly successful profiles in the country (Ndubuizu Reference Ndubuizu2022; Oguntola Reference Oguntola2022).

While many factors can explain experiences of discrimination by the immigrant population (Patten Reference Patten2016), research reveals that Black immigrants in the United States encounter discrimination that intersects their racial identity and immigration status (Hersch Reference Hersch2008). Racial discrimination, defined as the unjust treatment of individuals based on their race or skin color, has particularly emerged as a pressing human rights issue in the United States, which overlaps with immigration concerns (Human Rights Watch 2023). Intersectionality is a term that was discovered by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 and is a central concept in Black scholarship. It recognizes how multiple identities and oppressions intersect to create unique forms of oppression experienced by individuals with intersecting identities (Runyan Reference Runyan2018). For Black immigrants in the United States, intersectionality refers to how race and nationalities of origin produce distinct forms of discrimination and marginalization. Moreover, intersectionality acknowledges that systemic oppression cannot be understood or effectively challenged by examining just one form of identity. Instead, it considers the interactions between various systems of oppression and privilege, which contribute to a more nuanced understanding of discrimination (Potter et al. Reference Potter, Zawadzki, Eccleston, Cook, Snipes, Sliwinski and Smyth2019).

Given this premise, this study shows that Nigerian immigrants in the United States experience multiple forms of discrimination that comprise racial discrimination, employment-based discrimination, and discrimination based on nationality of origin. The research asks two important questions: (1) How do structural and social integration in the United States affect the experiences of Nigerian immigrants with racial and workplace discrimination? (2) How do national identity and social networks explain the perceptions of discrimination among this population? Findings from the study show that structural and social integration intersects with national identity and social networks to influence the experiences of Nigerian immigrants in the United States. Moreover, these factors play important roles in shaping their understanding of perceptions of discrimination.

The study makes important contributions to literature and policy discussions on understanding the integration challenges faced by immigrant minorities in their pursuit of the American dream (Conerly et al. Reference Conerly, Holmes and Tamang2021). It highlights the unique experiences of Nigerian immigrants within the broader context of the African diaspora in the United States. The study also contributes to the migration literature by showing that many Nigerian immigrants experience psychological trauma due to discriminatory acts of White supervisors or neighbors. Experiences of psychological trauma can hinder immigrants’ successful integration into their host society (Close et al. Reference Close, Kouvonen, Bosqui, Patel, O’Reilly and Donnelly2016). Furthermore, this research shows that Nigerian immigrants in the United States experience social exclusion, especially when they are forced to downplay their intellect for fear of being targeted for social or racial injustices. It also contributes to our understanding of how multiple forms of discrimination can intersect to create barriers for migrant integration and social cohesion in the receiving country.

In my research on the experiences of Nigerian immigrants in the United States regarding discrimination and the impact of structural and social integration, several critical gaps in the existing literature have been identified. Firstly, many studies tend to generalize findings across diverse immigrant groups, neglecting the unique challenges faced by Nigerian immigrants (Brettell Reference Brettell2011; Jasinskaja-Lahti et al. Reference Jasinskaja-Lahti, Liebkind and Perhoniemi2006; Showers Reference Showers2015). To understand their specific experiences, research explicitly focusing on this group is essential. Additionally, existing literature often overlooks the intersectionality of factors like race/ethnicity, nationalities of origin, social network, and socioeconomic status in shaping immigrant experiences, necessitating an investigation into how these factors intersect with structural and social integration for a more nuanced understanding.

Moreover, some studies heavily rely on quantitative data, thus lacking in-depth qualitative exploration of individual narratives (Liebkind and Jasinskaja-Lahti Reference Liebkind and Jasinskaja-Lahti2000; Krings et al. Reference Krings, Johnston, Binggeli and Maggiori2014). Given the deeply personal nature of experiences of discrimination, a solely quantitative approach may miss the nuanced context that qualitative methods can provide. While structural integration is frequently examined (Lewin-Epstein et al. Reference Lewin-Epstein, Semyonov, Kogan and Wanner2003; Misra et al. Reference Misra, Kwon, Abraído-Lanza, Chebli, Trinh-Shevrin and Yi2021), there is a gap in understanding how social integration specifically influences discriminatory experiences, highlighting the need to explore the social dynamics contributing to or mitigating discrimination for a holistic understanding.

Furthermore, instances of discrimination are sometimes reported without sufficient contextualization within broader social and structural factors. Recognizing that discrimination is not isolated but influenced by the sociocultural and institutional context emphasizes the necessity for a more contextualized approach to fully grasp its impact on Nigerian immigrants. Additionally, the literature may not adequately address the experiences of immigrants with a dual identity, combining aspects of their home and host countries. Acknowledging and understanding this dual identity is crucial for comprehending coping strategies and integration experiences.

Identifying these gaps underscores the importance of my research, contributing nuanced insights to the field and specifically addressing the unique experiences of Nigerian immigrants in the United States concerning discrimination and integration.

I began this study by reviewing previous literature discussing how integration in the United States can impact experiences of discrimination among immigrants and how national identity and social networks interact to facilitate or hinder immigrants’ perceptions of discrimination. This was followed by discussing the research design and methodology. Afterward, I discussed the findings from my quantitative and qualitative analysis to show how these findings can help us understand the depth and breadth of experiences of Nigerian immigrants. Finally, I discussed these findings and provided policy implications for both the United States and Nigeria.

Integration of Immigrant Minorities

Heath and Schneider (Reference Heath and Schneider2021) observe that the integration of immigrant minorities is a major concern for diverse societies—with major implications for the well-being of those affected, social cohesion, group relations, and economic and social progress. Scholars who study various integration experiences of immigrants have explained the various processes of adaptation into receiving societies, including the factors that may affect these processes. For instance, earlier scholars maintain that immigrants lose their identity as they assimilate into the host society (Dustmann Reference Dustmann1996). In America, this assimilation process occurs when the immigrant completely loses their identity over time and takes on the identity of the mainstream (White) society.Footnote 3

Unfortunately, not all immigrants are able to experience complete assimilation due to the differences in sociocultural backgrounds and racial and cultural identities, among others. Since the enactment of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the United States has increasingly admitted immigrants of diverse social, racial, and cultural backgrounds,Footnote 4 thus creating unique identities of individuals that would otherwise be lost due to complete assimilation. As a result of these differences in identity, newer assimilation theorists acknowledge the discrete identities and cultural differences that exist in multicultural western societies such as the United States. These scholars raise important questions about non-ethnic forms of identity, nationalities of origin, differences in migration patterns, and shared ethnic or racial identities to explain the shortcomings of previous theories that failed to take these nuances into account (Alba and Nee Reference Alba and Nee1997; Reference Alba and Nee2012; Dahinden Reference Dahinden, Messer, Schroeder and Wodak2012; Kivisto Reference Kivisto2015). They also explain why immigrants from these different sociocultural backgrounds experience a lack of socioeconomic mobility because of their minority backgrounds. For example, Portes and Rivas (Reference Portes and Rivas2011) postulate that there are different trajectories for migrant incorporation into American society, including becoming part of the mainstream (White) society and experiencing upward mobility, remaining ethnic, or becoming part of the underclass and experiencing downward mobility (p. 221). Similarly, Levitt (Reference Levitt1998) observes that although “newer immigrants” can achieve socioeconomic parity with the native-born, the ideas of race and ethnicity matter (p. 130). This means that race and ethnicity can constitute a barrier to achieving socioeconomic parity with the native-born. Waters and Kasinitz (Reference Waters and Kasinitz2021) also observe that race and ethnicity may not be the only determinants of socioeconomic mobility among immigrants but that these variables may intersect with legal status to exacerbate an immigrant’s socioeconomic condition in the receiving society (p. 120).

In the case of Nigerian immigrants living in the United States, the article “Coming to America: The Social and Economic Mobility of African Immigrants in the United States” explains why Nigerian immigrants in the United States experience difficulty in achieving higher socioeconomic success. The author found that many Nigerians experience social and economic stagnation due to structural, cultural, and socioeconomic barriers (Afolayan Reference Afolayan2011).

These studies illustrate the complexities of immigrant integration in diverse western societies, emphasizing the importance of considering social, racial, and cultural factors. They provide a foundation for understanding the challenges faced by Nigerian immigrants in the United States. Based on these studies, I proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Structural integration affects the experiences of Nigerian immigrants with racial and workplace discrimination. Greater structural integration is associated with reduced experiences of discrimination.

Hypothesis 2: Social integration affects the experiences of Nigerian immigrants with racial and workplace discrimination. Greater social integration is associated with reduced experiences of discrimination.

The Roles of National Identity and Social Networks in Migrant Integration

Marschelke (Reference Marschelke, Sellers and Kirste2021) discusses the concept of national identity, describing it as a collective feeling or understanding that can be incorporated into individuals’ personal identities, influencing their sense of belonging. He notes, however, that analyzing “national identity” presents three challenges. Firstly, the constituent terms “nation” and “identity” are broad, transdisciplinary, and controversial, often linked with complex concepts like nationalism, ethnicity, and culture. Secondly, “national identity” is not confined to academic discourse but is also used in political and everyday discussions, requiring attention to its multifaceted nature. Thirdly, nationalistic ideas have demonstrated adaptability, gaining support across various ideologies and movements, such as liberals, conservatives, Marxists, fascists, racists, and anti-colonialists, highlighting the complexity and evolving nature of this concept over time.

Nevertheless, the integration of immigrants is profoundly shaped by national identity, influencing their sense of belonging and inclusion. Successful integration is closely tied to immigrants’ connection to the host country’s identity, encompassing cultural adherence, values, and language proficiency (Johnson and Hing Reference Johnson and Hing2005). Where a robust national identity motivates immigrants to engage in civic activities, with educational institutions playing a role in transmitting this identity to younger generations; positive perceptions of national identity within the host society foster a welcoming environment, with multicultural policies celebrating diversity and government policies either facilitating or hindering integration. Meanwhile, media portrayal significantly influences public opinion on immigrants (Haynes et al. Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016).

Some immigrants maintain a dual identity, blending aspects of their home and host countries, and acknowledging and respecting this duality contribute to successful integration (Gocłowska and Crisp Reference Gocłowska and Crisp2014). National identity, therefore, is foundational to the integration process, impacting various aspects of immigrants’ lives and interactions, and recognizing diversity within this shared identity promotes inclusivity.

Additionally, social identity (sometimes used interchangeably with national identity) is a crucial factor influencing successful integration (Vinney Reference Vinney2019). Despite being homogenized, considerations such as national origin, migration patterns, and generational distinctions are essential among Black immigrants. Social identity theory, developed by Tajfel and Turner in 1979, explains how individuals define themselves within groups and perceive social, sometimes leading to intergroup prejudice and conflict (Harwood Reference Harwood2020; Trepte and Loy Reference Trepte and Loy2017; van Dick and Kerschreiter Reference van Dick and Kerschreiter2016). Studies connect social identity to racial discrimination (Chen and Mengel Reference Chen and Mengel2016), highlighting the complex strategies employed by Black immigrants to navigate evolving Black subjectivity. Notions of national identity and social identity are instrumental in understanding how Nigerian immigrants perceive discrimination in the United States.

Meanwhile, Revenston and Lepore (Reference Revenston TA & Lepore2012) maintain that social networks influence the availability and effectiveness of social support, ultimately impacting individuals’ health and well-being. He identifies two key dimensions: structural characteristics, encompassing quantitative indicators like network size and social integration, and functional characteristics, which focus on the resources provided by the network, including emotional and material aid. Lepore emphasizes that social support relies on the combination of having a social network and the provision of specific resources through that network.

Social networks play a pivotal role in the immigrant experience, influencing various aspects of integration. These networks, comprising relationships and connections within a community, can significantly shape the trajectory of immigrants in their new environment. Research shows that immigrants often form diverse social networks, ranging from family and friends to community organizations and fellow immigrants (Bankston Reference Bankston2014; Ryan Reference Ryan2011). These networks include formal categories such as organizations, support groups, and institutions, which are designed to assist immigrants (Kloosterman et al. Reference Kloosterman, Van Der Leun and Rath1999). Informal networks, on the other hand, consist of personal relationships and connections forged through daily interactions (Leslie Reference Leslie1992). Social support networks are crucial for immigrants as they navigate the challenges of adapting to a new culture and society. Emotional support, practical assistance, and guidance provided by these networks contribute significantly to an immigrant’s well-being. Whether helping with language acquisition, job searches, or cultural acclimatization, social support networks serve as valuable resources.

It is essential to recognize that not all social networks are equally beneficial. Some immigrants may face challenges if their networks are limited or if they encounter discrimination within specific communities. Additionally, the diversity of social networks within immigrant populations reflects the varied experiences and needs of individuals, emphasizing the importance of understanding and addressing these differences. Given that social networks are integral to the immigrant experience, serving as a support system that significantly influences the success of integration, recognizing the diverse types of networks, understanding their importance, and addressing challenges within these connections are essential aspects of fostering a welcoming and supportive environment for immigrants. Based on these studies, I proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: National identity explains the perceptions of discrimination among Nigerian immigrants. Stronger identification with a Nigerian national identity is associated with a heightened perception of discrimination.

Hypothesis 4: Social networks play a role in explaining the perceptions of discrimination among Nigerian immigrants. Stronger social networks within the Nigerian immigrant community are associated with lower perceptions of discrimination.

Research Design and Methodology

The research design for this study encompasses data collection, sampling methods, and data analysis. The study employs both quantitative and qualitative research methods to gain a comprehensive understanding of the research objectives. Understanding the experiences of Nigerian immigrants facing discrimination in the United States necessitates a comprehensive and nuanced approach.

The use of mixed research methods combining both quantitative and qualitative approaches proves crucial in unraveling the intricate layers of structural and social integration and their effects on discriminatory experiences (Trahan Reference Trahan2011). Quantitative methods offer statistical insights into the prevalence and patterns of discrimination, identifying trends and correlations (Forman et al. Reference Forman, Williams, Jackson and Gardner1997). On the other hand, qualitative methods delve deeper into individual narratives, providing context, nuance, and personal perspectives that quantitative data might overlook (Elliot and Timulak Reference Elliot, Timulak, Miles J and Gilbert P2005; Merriam and Tisdell Reference Merriam and Tisdell2015). The integration of both approaches aims to offer a synergistic understanding of the complexities surrounding discrimination within the Nigerian immigrant community in the United States.

Sampling

The quantitative study engaged 183 Nigerian immigrants in the United States. Out of these, 22 participants underwent follow-up interviews to gain more in-depth insights into their experiences for the qualitative section. Only immigrants who were 18 years old and above were allowed to participate in the study. The demographics of all participants include 48% males and 44% females, while 8% did not indicate their gender. Age groups were distributed as 27.9% (18–24 years), 51% (25–44 years), and 13.7% (45 years and above). All participants were confirmed Nigerian immigrants by asking about their place of birth and region of origin in Nigeria, namely, North, North-Central, South-East, South-South, and South-West geopolitical zones. This study focused on first-generation immigrants (composed of individuals who are foreign-born, including naturalized citizens, lawful permanent residents, protracted temporary residents, and humanitarian migrants such as refugees and asyleesFootnote 5 ; see also Gonzales Reference Gonzales2016), while second-generation immigrants (individuals born and raised in the United States with one or both parents from Nigeria (Suro and Passel Reference Suro and Passel2003)) were excluded due to their low representation.

The study employed snowball sampling, a chain-referral technique, to collect data. Initial contacts included personal connections, and further referrals were obtained from friends, colleagues, family, and acquaintances. Additionally, Nigerian organizations in the United States, such as the Nigerian Community of Merrimack Valley (NCMV), Berom Community North America (BCNA), Plateau State Association USA (PSA), African Christian Fellowship (ACF), and International Family Church (IFC), were engaged to connect with their Nigerian members. Snowball sampling was chosen due to the convenience of reaching widely dispersed Nigerian immigrants in the United States (Savin-Baden and Major Reference Savin-Baden and Major2013).

Data Collection

The survey was created using Qualtrics, an online survey platform, and distributed via email, Facebook, Homeis, LinkedIn, and WhatsApp. Using social media to collect data has several advantages. One advantage lies in one’s ability to quickly contact people without worrying about how to obtain their email addresses for survey distribution (Mirabeau et al. Reference Mirabeau, Mignerat and Grange2013). Moreover, multiple reminders were sent to enhance the response rate (Pedersen and Nielsen Reference Pedersen and Nielsen2016).

Furthermore, the interview protocol was created with open-ended questions to allow participants to express their understanding of the questions asked. The interviews were conducted between the summer of 2020 and 2021, via Zoom to ensure compliance with coronavirus disease 2019 guidelines (Cetron and Landwirth Reference Cetron and Landwirth2005). All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded in NVivo. To maintain confidentiality and anonymity, names of participants were removed, and pseudonyms were assigned to participants.

Operationalizing the Dependent and Independent Variables

Two dependent variables in this study represent two forms of discrimination. The first is “racially motivated discrimination.” The concept of racially motivated discrimination refers to the type of discrimination that occurs purely because of one’s racial identity or skin color (Monk Reference Monk2015). This variable was initially measured on a four-point ordinal scale, where I asked respondents if they had ever experienced discrimination because of their skin color. The variable “racial discrimination” was measured on a re-coded four-point scale (0–2) where 0 represents no discrimination and 2 indicates experiencing discrimination based on skin color. The nuanced responses to this variable are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A graphic presentation of racial discrimination experienced by Nigerians in the United States (N = 183)

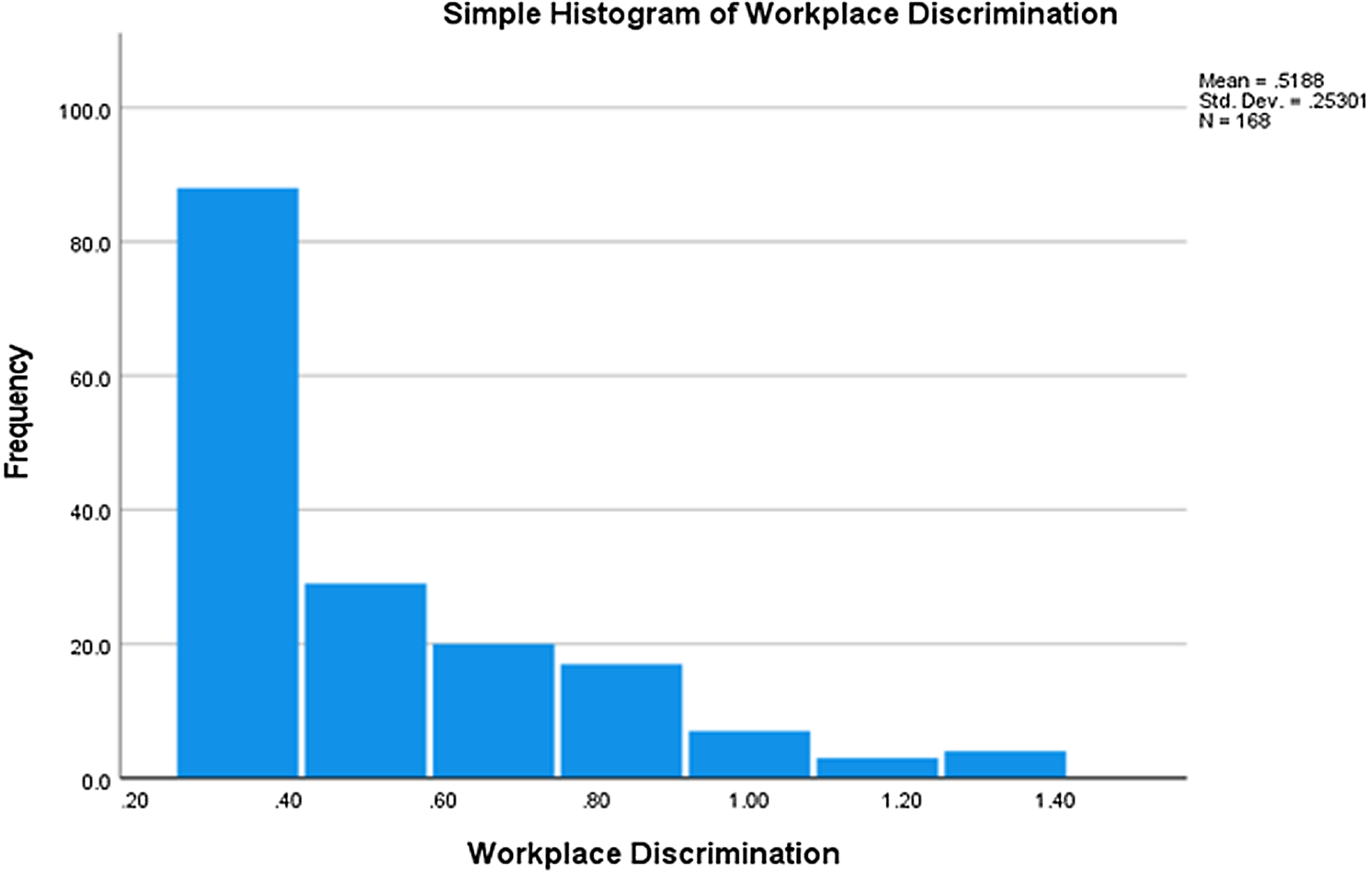

The second dependent variable is “workplace discrimination” defined as the various kinds of prejudice that immigrants experience in the labor market of their receiving societies (Wassermann et al. Reference Wassermann, Fujishiro and Hoppe2017). Previous studies have used several indicators to show how immigrants experience discrimination at their places of work, including blocked promotion, bullying and harassment, and poor wages, among others (Canache et al. Reference Canache, Hayes, Mondak and Seligson2014). Workplace discrimination was assessed using various indicators, including underemployment, inadequate pay, blocked promotion, poor work conditions, bullying, and harassment from managers or co-workers. These were combined into a reliable scale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.741). The intricate array of responses to inquiries about workplace discrimination is vividly depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. A graphic presentation of workplace discrimination experienced by Nigerians in the United States (N = 168)

In this study, I measured two sets of independent variables—structural and social integration. Heath and Schneider (Reference Heath and Schneider2021) (following Jonsson et al. Reference Jonsson, Kalter, van Tubergen, Kalter, Jonsson, van Tubergen and Heath2018) distinguished between five dimensions of migrant integration—structural, social, cultural, political, and civic integration. They view structural integration as achieving parity with the dominant group in terms of the socioeconomic positioning of the individual in society based on employment and occupation. Similarly, De Haas and Fokkema (Reference De Haas and Fokkema2011) described structural integration as the acquisition of rights and status (including employment, housing, education, and political and citizenship rights) within the core institutions of the receiving countries. Drawing from these studies, I conceptualize structural integration as the extent to which Nigerian immigrants in the United States become integrated into the societal structures of their host country. I measured the concept “structural integration” by participants’ satisfaction with life, jobs, and neighborhoods on a scale of 1–5, with 5 indicating higher integration.

Social integration has been described as the social blending of members of majority and minority groups together on equal terms. De Haas and Fokkema (Reference De Haas and Fokkema2011) combined the elements of social and cultural integration to describe the cognitive, behavioral, and attitudinal changes in conformity to the dominant norms of the receiving society. They further sub-categorized sociocultural integration into interactive integration, which is indicated by social intercourse, friendship, marriage, membership into various organizations of the receiving country, and identification integration characterized by feelings of belonging that are expressed in terms of loyalty to ethnic, regional, local, and national identity (pp. 763). Drawing from this study, I conceptualize “social integration” as the degree to which Nigerian immigrants are embraced and accepted within the social fabric of American society. It considers elements like social interactions, community engagement, and cultural assimilation. Social integration was measured through responses to statements about social interactions, such as “Americans often seek my company, I often feel like an outside at social gatherings,” and feelings of belonging, such as “I often feel like an outside in social settings,” both rated on a scale of 1–5, with 5 indicating the higher rating.

National identity is a person’s identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or one or more nations (Ashmore et al. Reference Ashmore, Jussim and Wilder2001). It may refer to the subjective feeling one shares with a group of people about a nation, regardless of one’s legal citizenship status (Guibernau Reference Guibernau2004). Drawing from these studies, I conceptualize “national identity” as the extent to which Nigerian immigrants identify with their home country (Nigeria). It encompasses feelings of belonging, attachment, and cultural allegiance. National identity measured participants’ assessment of the importance of their national identity on a scale of 1–5, with 5 being the highest rating.

According to Repke and Benet-Martínez (Reference Repke and Benet-Martínez2017), social networks are composed of nodes (representing actors like individuals, groups, or organizations) and ties (indicating the connections or social relations between these actors). While sociocentric network studies concentrate on complete networks, analyzing relationships within an entire group, personal social network studies take the perspective of a specific actor, examining the connections surrounding that individual. Drawing from this study, I conceptualized “social networks” as the interpersonal relationships and connections that Nigerian immigrants have within their immigrant community, as well as with members of other ethnic and racial groups in the United States (Maundeni Reference Maundeni2001). In this study, social networks are determined by the importance of social networks to participants on a scale of 1–5, with 5 being the higher rating. Responses ranged from 1, “social network is not important to me,” to 5, “all my friends are Americans.”

In addition to the main variables, this paper controls for several variables identified in the literature as potential predictors of discrimination. These include the following: education, participants’ highest level of education, ranging from high school to Ph.D.; employment, a dichotomous variable (employed/unemployed) based on a five-point scale; citizenship, a categorical variable (non-resident alien, permanent resident, and US citizen); income, participants’ yearly income before taxes on a scale from less than $10,000 to more than $150,000; age, categorized as younger (18–24 years), mid-age (25–44 years), and older (45 years and above); and gender, represented by dummy variables (male and not male). I present the full descriptive statistics of the data in Table 1 in the appendix.

Table 1. Descriptive analysis of demographic data and variables (N = 183)

Table 2. Showing a Regression model of racial and workplace discrimination (N = 183)

Note: ***p<.001, **p<.010, *p<.050, ∼ p<.100.

Data Analysis and Results

The study aimed to examine the relationship between various factors, including structural integration, social integration, national identity, social network, and demographic controls, with both racial and workplace discrimination among Nigerian immigrants in the United States. The study employs descriptive and interpretive approaches to analyze both quantitative and qualitative data. In the quantitative section, the dependent and independent variables are analyzed using appropriate statistical methods to understand the relationship between discrimination and its determinants. Similarly, the qualitative study draws insights from the interview narratives. The findings from the multivariate regression analysis are presented and discussed first, followed by the findings and discussions on the interview analysis (Table 2).

In the quantitative study, the first hypothesis investigated the impact of “structural and social integration” on “racial and workplace discrimination.” The results indicate the following.

Structural Integration

The study found a negative relationship between “satisfied with life in the United States” and both racial and workplace discrimination (p<.01 and p<.001, respectively), as shown in Table 1. This suggests that Nigerian immigrants who are satisfied with their lives in the United States are less likely to experience racial and workplace discrimination.

The study also found a negative relationship between “satisfied with job” and “workplace discrimination” (p<.1), implying that satisfaction with one’s job is associated with a lower likelihood of workplace discrimination. This finding, however, does not affect racial discrimination.

Social Integration

The study found a positive relationship between “Americans often seek my company” and workplace discrimination, and “I often feel like an outsider in social gatherings” and both racial and workplace discrimination (p<.1 and p<.001, respectively), as shown in Table 1. These results indicate that having close relationships with Americans is associated with workplace discrimination, while feeling like an outsider in social gatherings is related to both racial and workplace discrimination. One possible explanation of having a close relationship with Americans and experiencing workplace discrimination could be due to implicit or unconscious biases or stereotypes about certain groups of people, including non-Americans, which may influence workplace interactions. Close relationships with Americans may not necessarily eliminate such biases and could, in some cases, exacerbate them.

National Identity and Social Network

The second hypothesis aimed to establish a positive relationship between national identity and social network with both racial and workplace discrimination. However, the results found a positive relationship between social network and workplace discrimination (p<.1), as shown in Table 1. This suggests that Nigerian immigrants who have established social networks among the native population are more likely to report workplace discrimination.

Although the third hypothesis proposed a positive relationship between “national identity” and both “racial and workplace discrimination,” no significant result was observed. Meanwhile, the fourth hypothesis proposed a negative relationship between “social networks” and both racial and workplace discrimination. The result revealed a positive relationship between social networks and racial discrimination (p<.01), which can be seen in Table 1. This suggests that as Nigerian immigrants engage more with the mainstream American society through social networks, they may uncover racial discrimination that may not be obvious from a distance (Foner Reference Foner2016). This finding underscores the significance of proximity to the native population in identifying nuanced forms of discrimination.

Among the control variables, a positive relationship was found between current age and racial discrimination, indicating that older Nigerian immigrants are more likely to experience racial discrimination. This could be attributed to their lengthy exposure to potential racism and cultural nuances, which they may interpret as discriminatory (Nkimbeng et al. Reference Nkimbeng, Taylor, Roberts, Winch, Commodore-Mensah, Thorpe, Haan and Szanton2021). Also, a positive relationship was found between being employed and workplace discrimination (p<.1). This aligns with existing literature where immigrants are shown to face workplace discrimination due to their migration status (Esses Reference Esses2021). Finally, a positive relationship was observed between higher income and racial discrimination (p<.1), which can be seen in Table 1. This finding is consistent with the literature, highlighting how immigrants of color, regardless of their socioeconomic status, experience discrimination in the United States (Afolayan Reference Afolayan2011).

Overall Findings

In summary, the regression model reveals that variations in the reported experiences of discrimination among Nigerian immigrants in the US structural integration, social integration, social networks, age, employment, and income all influence the likelihood of experiencing racial and workplace discrimination. These findings contribute to the understanding of the nuanced relationships between integration, social networks, and discrimination among Nigerian immigrants in the United States.

The results of the study highlight the importance of considering factors related to structural and social integration, as well as social networks, when examining the experiences of discrimination among immigrant populations. It also suggests that older immigrants may be more sensitive to discrimination due to their longer exposure to it and that social networks play a significant role in uncovering subtle forms of discrimination.

Further research and policy considerations may be needed to address the specific challenges faced by Nigerian immigrants in the United States and to develop interventions that promote greater integration and reduce the likelihood of experiencing discrimination.

Interview Analysis and Results

The interview analysis explored multiple facets of discrimination, encompassing racial discrimination, workplace discrimination, structural and social integration, Nigerian identity, and social networks. The subsequent discussion organizes the findings according to distinct dimensions of discrimination and immigrant experiences.

Structural and Social Integration

The findings from the qualitative analysis show that immigrants feel more structurally integrated into the United States, as they often have better living conditions and job opportunities compared with their home country. This suggests that despite the presence of racial and workplace discrimination, the United States provides opportunities for immigrants to thrive. For instance, Victor appreciates his life in the United States in the following narrative: “All I can say is that I love my life here in the US. This is because I have discovered that this country helps bring out the best in you. If you have an interest and you want to pursue it, they give you the opportunity to do that. Also, there is good security here. Which helps you to feel at home and focus on what you want to do without any fear.” While the United States may provide the necessary conditions for immigrants to thrive and advance, experiences of discrimination may prolong the process of successful integration.

Social integration can be more challenging for immigrants, as they may perceive Americans as individualistic, missing the communal life they were used to in Nigeria. Some respondents reported difficulties in forming close relationships in American society, as seen in this excerpt from Maimuna: “I just accepted the fact that that is how the American society is. They are individualistic with no communal living like the one we had in Nigeria. So, I just had to accept that and live with it. I have adjusted to society the way it is. I do not expect my neighbor to greet me or respond to my greetings.”

Nuanced Experiences of Racial Discrimination

Nigerian immigrants face racial discrimination intertwined with workplace discrimination, impacting mental health and well-being. Several respondents indicated that they experienced different nuances of racial discrimination including the following:

Interconnected Discrimination: Sarah recounts experiencing mistreatment at work due to her skin color. She says, “I remember crying for several nights, especially at my place of work. I had spoken with my supervisor at one time, telling her, ‘I am sorry that I am the way that I am (meaning that she is Black). Nevertheless, look at the job I do instead of how I look. I cannot change who I am, but I can change how I do my job. If you are not satisfied with my performance, then know that I am trainable. But I cannot change the way I look. I am grateful to God because that is what he gave me. It is a gift that I cannot reject. So, just work with me with regards to the job’.” Sarah was not the only person who encountered racial discrimination. Becky’s mother also confronted racial insults at a post office, while visiting from Nigeria. According to Becky, “When my mom came to visit me here (in the US), we went to the post office together, where a young man came up to my mum and told her that she looked ugly like a monkey. And that she should return to Africa where she came from. My mom turned to me and asked what the boy had said (since she doesn’t understand English), and I told her. My mom asked me to tell the boy that… ‘yes, I may be ugly or look like a monkey, but I did not make myself. This is how God made me’. Then she said to ask him, ‘can you create an ugly one like me?’ On hearing what she said, the young man got up and left.” Becky’s mother responded with dignity and self-assurance, challenging the derogatory comments and ultimately causing the person who insulted her to leave the scene. Unfortunately, not everyone is able to respond as she did.

Racial Profiling: Paul is another respondent that recalls experiencing racial profiling in a predominantly White neighborhood where he works. According to Paul, “About three years ago, I went to a primarily White area to see a patient. I could not find the direction to the place, so I called the owner of the foster home where the patient lives, and then I parked my car on the side of the road. There was a young boy that was mowing a lawn. The boy called the owner of the house, who came out and told me to leave. I told him that my car was parked at the side of the road, so I would not leave. Then he threatened to call the police if I did not leave. I told him to call the police, ‘How can you see me park a car by the side of the road and behave like this?’ I asked. So, he waited a few minutes until the owner of the foster home came to get me, then he left.”

Paul also recalls a similar incident in a different, White-populated area, where he had gone to work. He claims that as soon as he arrived in the area, a White man threatened to shoot him if he does not leave the area. Although Paul is a medical professional, he views that threat as occurring because of his skin color. These findings show how Nigerian immigrants who live or work in predominantly White neighborhoods encounter microaggressions and racial profiling, based on stereotypes that depict them as potential criminals.

Church Discrimination: Nigerian immigrants experience racial discrimination that extends to places of worship. Chundung, who lived in the United States for over 20 years, narrates her experience with discrimination at a predominantly White church. According to Chundung, “White churchgoers would pull away when we tried to get close to them. Only the pastor and his wife were accepting. Even my young daughter also faced rejection from White children. The racism within the church, along with difficulties making friends with White individuals outside the church, led me to prefer sticking with my own community, Nigerian people.”

Subtle Racism: Unlike Chundung, who experienced an overt form of racism, Martha experiences subtle racism in a predominantly White church, where positive stereotyping turns to surprise when she expresses intelligence. In her own words, Martha says, “I worship with a predominantly White church where… I have observed two kinds of discrimination among White people. One is outright dislike, you know. The other one is very subtle, where the individual appears extra nice. They assume you are not intelligent enough because you came from a developing country. So, they try to be extra nice. But whenever you say something intelligent, then they become surprised. I find that very irritating.”

Interracial Relationships: Danladi faces harassment in interracial relationships, revealing deep-seated prejudices and challenges in cross-race relationships. Although he was ignorant of interracial issues in the United States when he first arrived in the country, Danladi says, “When I first arrived in the US, I began a relationship with a White woman. Initially, I didn’t realize the significance of race issues on campus, but soon faced harassment from both the Black community and the police due to our interracial relationship. The police would often stop us, claiming there had been a robbery involving a Black man and a White woman[…] The realization of the historical racial tensions in America, including violence against Black men for associating with White women, made me fearful and more aware of the racial dynamics at play.” The above narratives are relevant to literature on experiences of African immigrants in the United States (Asante et al. Reference Asante, Sekimoto and Brown2016).

Collective Racism: Funke describes collective racism in addressing educational disparities, fostering solidarity among Black students. In her narrative, she described how experiencing collective racism led to putting up a united front to confront institutional discrimination that was deeply rooted in systemic injustices. In an excerpt from an interview, Funke says, “When I was a young undergraduate student at a predominantly White campus, I did not experience racism directly, but witnessed what I call ‘collective racism’. I joined other Black students, many of whom were American born, in various struggles against tuition hikes, political integration, tenure for Black professors, and affirmative action. Our collective effort aimed at addressing disparities in education opportunities for Black students.”

Stereotyping: Prince faces skepticism about his abilities due to his Nigerian accent but proves himself through writing. Stereotyping often plays a role, with immigrants being underestimated or facing skepticism about their abilities, especially when they do not have a typical American accent. Prince says, “I faced challenges in American English classes as some students underestimated my abilities due to my Nigerian accent. However, I proved my skills through writing, often outperforming my peers.”

Nuanced Experiences of Workplace Discrimination

Immigrants may downplay their abilities to avoid workplace discrimination, facing challenges even in areas where they excel. Hadiza, who experienced discrimination in the workplace, faced hostility from her colleagues and supervisors and challenges due to cultural differences. According to Hadiza, “Of course, as a Black person in this country…I have experienced a lot of discrimination. For example, at my previous job, my supervisor hated me for no reason. So, I assumed it is either because of the color of my skin or because I came from another country. As a Nurse in Nigeria, my training included having interactive relations with my patients. But when I interacted with my patients here, they loved it. Unfortunately, that made me a target among my colleagues, who often reported me to my bosses for little to no offense… So, that makes the work very challenging.”

Skills Underutilization and Job Market Underqualification and Overqualification: Nigerian immigrants may experience challenges in the workplace, with skills being either underutilized or overqualified, leading to wage gaps (Cornelissen and Turcotte Reference Cornelissen and Turcotte2020). Davou who experienced both underqualification and overqualification says, “I faced discrimination while job hunting in the US, being told that I was either underqualified or overqualified for positions. I eventually settled for a job as a technician with unequal pay compared to my qualifications.” This narrative is consistent with existing research, which shows that migrant skills are often underutilized because of discrimination (Reitz Reference Reitz2001).

Some immigrants face challenges and rely on themselves in a new work environment, overcoming obstacles but not receiving due recognition. Philip had to train himself for a job where he improves machines but faces chastisement instead of promotion, highlighting challenges and confusions. According to Philip, “I was hired as a design engineer and immediately began upgrading the firm’s outdated systems. I encountered issues at work related to my mechanical manufacturing background. I was supposed to collaborate with another engineer with an electrical control background, but my colleague wasn’t fulfilling his own part of the work. I learned to do the electrical work myself and improved the machines. However, when I expected a promotion, the human resource (HR) manager asked me to take it easy, leaving my feeling surprised and confused.”

These themes collectively reflect the complex and multifaceted experiences of Nigerian immigrants in the United States, encompassing structural and social integration and racial and workplace discriminations.

Discrimination Based on National Identity and Immigration Status

Instances of discrimination based on national identity and immigration status were found in my study, where Nigerian immigrants faced discrimination from both White and Black Americans in the United States. These experiences originate from the immigrants not being American nationals.

Findings from the study show evidence of discrimination within minority groups, where native-born Black Americans discriminate against African immigrant due to positive stereotypes and success. Adamu says, “Discrimination by some White individuals creates divisions among Black immigrants and African Americans by reinforcing stereotypes, leading to strained relationships.” This occurs when White Americans praise foreign-born African immigrants for being smart, hardworking, and successful to disparage African Americans, which is consistent with the model minority literature (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Block and Yu2021). Contrastingly, African immigrants face discrimination rooted in their identity, as illustrated by Badung, a college professor, who recounts his challenges both as a graduate student and in the pursuit of a professorial position.

“Initially, … I encountered culture shock yet found solace in having a professor who shared my background. Out of the three Black individuals in my department, one returned to Nigeria due to feeling more accepted there as a Muslim. Unfortunately, two white professors and a technician exhibited discrimination, consistently ignoring me, and withholding respect. Overcoming racism in college required proving my capabilities. Subsequent job applications to several universities revealed persistent discrimination based on my name and accent. Despite these challenges, I hold onto the belief that what is meant for me cannot be obstructed. The experience taught me that, regardless of location, people vary in kindness, and I focus on connecting with those who uplift rather than dwelling on negativity” (Badung).

Additionally, discrimination often intersects based on both race and immigration status, contributing to unique challenges for Nigerian immigrants. Tolu perceives discrimination due to being a Black immigrant, facing preconceived notions and harsh judgment in an academic setting. According to Tolu, “I believe I face discrimination for two main reasons. First, it is because I am Black, and second, it is because I am a Black immigrant. I feel that people expect me to be less knowledgeable in an academic setting due to my race and immigrant status. I think that preconceived notions about Black immigrants lead to unfair treatment, and while White individuals make similar mistakes, they aren’t judged as harshly. So, I believe that my skin color is the primary reason for differential treatment, but my migrant status also plays a role.” Scholars have examined the intersections that exist between multiple forms of discrimination in society. Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw2016) observes that it is important to develop frames through which we can understand how different forms of discrimination intersect to create different forms of oppression in society. My study found evidence of intersecting discrimination experienced by Nigerian immigrants in the United States.

Discussions of Research Findings and Conclusions

The qualitative results reveal that in a paradoxical scenario for Nigerian immigrants in the United States, while they report feeling structurally integrated due to improved living conditions and job opportunities, social integration remains challenging. Victor’s positive sentiments about life in the United States emphasize opportunities and security. However, Maimuna’s experience highlights the struggle to adapt to American individualism, missing the communal life from Nigeria. This suggests that despite structural opportunities, the social fabric poses significant hurdles for immigrants (Constant et al. Reference Constant, Kahanec and Zimmermann2009).

The findings from the study paint a stark picture of racial and workplace discrimination faced by Nigerian immigrants in the United States. Interconnected discrimination, exemplified by Sarah’s mistreatment at work, showcases the complex challenges immigrants encounter. Becky’s mother’s dignified response to racial insults contrasts with Paul’s experiences of racial profiling in predominantly White neighborhoods. The narratives highlight not only workplace discrimination but also incidents in public spaces, places of worship, and interracial relationships. These instances underscore the pervasive nature of racial discrimination, encompassing various aspects of immigrants’ lives.

The study unveils discrimination based on national identity and immigration status. Adamu notes the creation of divisions within minority groups, as African immigrants’ success is used to disparage African Americans (Yu Reference Yu2006). Tolu’s perspective on discrimination acknowledges the intersectionality of race and immigration status, resulting in unique challenges for Black immigrants. Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality is particularly relevant here, providing a framework to understand the interconnected nature of multiple forms of discrimination faced by Nigerian immigrants (Runyan Reference Runyan2018).

The workplace becomes a battleground for immigrants who, despite excelling, may face discrimination. Hadiza’s experience reflects challenges in nursing due to cultural differences and preconceived notions. Job market discrimination, as illustrated by Davou’s struggle with underqualification and overqualification, aligns with existing research indicating underutilization of migrant skills (Livingstone Reference Livingstone2017). The workplace discrimination theme underscores systemic challenges that hinder immigrants’ professional growth and equitable employment opportunities (Bradley-Geist and Schmidtke Reference Bradley-Geist, Schmidtke, Colella and King2018).

Skill underutilization and self-reliance emerge as prevalent challenges for Nigerian immigrants in the workplace. Philip’s narrative exemplifies the struggle to navigate a role requiring collaboration, showcasing the need for self-reliance. The HR manager’s response to Philip’s expectations of promotion highlights the disconnect between immigrants’ efforts and organizational recognition. These challenges underscore the need for organizations to address biases and create inclusive environments that acknowledge and reward immigrant contributions.

In summary, the research findings shed light on the multifaceted experiences of Nigerian immigrants in the United States, emphasizing the intricate interplay between structural opportunities, social integration challenges, and various forms of discrimination. The study contributes valuable insights to discussions on immigration, discrimination, and the need for more inclusive and supportive structures.

In conclusion, this research provides a comprehensive understanding of the discrimination experiences of Nigerian immigrants in the United States. It highlights the nuanced relationship between structural and social integration and the different forms of discrimination faced by immigrants. The findings emphasize that successful integration can contribute to strong, inclusive communities, while discrimination can hinder immigrants from contributing meaningfully to their receiving society. This research has important implications for policy initiatives aimed at improving the coexistence of immigrant communities within the United States. It also contributes to the broader literature on race relations and ethnicity.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2024.7.

Data availability

I am open to sharing my data for replication purposes should anyone express interest in reproducing the study.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful for the enriching experience of presenting my work at the Global Studies Department, University of Massachusetts, Lowell, where invaluable insights and constructive feedback from the audience have significantly enhanced my project. I extend special thanks to my mentors, Professors John Wooding, Angelica Duran-Martinez, Mona Kleinberg, and Jenifer Whitten-Woodring, for their instrumental guidance and discerning feedback. The contributions of three anonymous reviewers have played a pivotal role in refining my research, elevating its quality and scholarly merit. Additionally, I extend sincere appreciation to my dedicated copy editor, Alison Avery, whose meticulous attention to detail and editorial expertise have been indispensable in ensuring the accuracy and polish of the final work. Reflecting on these collaborative efforts, I am sincerely thankful for the collective support and encouragement, which has significantly strengthened and shaped this research endeavor.

Funding statement

This research was conducted without external funding. The project was self-funded, and resources were provided through personal means and institutional support.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests or conflicts of interest associated with this research.

Ethical statement

This research strictly adheres to institutional and local requirements for human subject research compliance, following Spradley’s (Reference Spradley1979) ethical perspective on unobtrusive ethnographic research. Emphasizing participant confidentiality, informed consent was obtained for audio and visual interview recordings, ensuring anonymity in reporting results. The University of Massachusetts, Lowell, Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 20-021-WOO-EXM) approved the study, and ethical standards were rigorously maintained throughout, with explicit participant consent and pseudonym usage to safeguard anonymity during analysis.