What process of change can come from a people who do not know who they are, or where they come from? If they do not know who they are, how can they know what they deserve to be?Footnote 1

In 1976, after being imprisoned and forced into exile from his home country, Uruguay, Eduardo Galeano defiantly wrote “Defensa De La Palabra” (In Defense of the Word). In it, he argued that denying people access to their histories obstructs their vision of themselves as a people connected across time, and therefore restricts their ability to envision change for their future. He believed contributions to the revelation of the past depended on “the intensity level of the writer's responsiveness to his or her people—their roots, their vicissitudes, their destiny.”Footnote 2 Forty-four years later, Galeano's reflections remain timely and methodologically instructive for those working at the nexus of history and education:

Our authentic collective identity is born out of the past and nourished by it—our feet tread where others trod before us; the steps we take were prefigured—but this identity is not frozen in nostalgia. … We are what we do, especially what we do to change what we are: our identity resides in action and in struggle [emphasis in original].Footnote 3

This is where we enter the conversation about methodology in educational history. We are deeply indebted to those who have come before us in the struggle to recover hidden histories and challenge the distortions about Communities of Color in “official” narratives.Footnote 4 Such critical revisionist excavations enable us to see more of ourselves across time and place and offer insight about how we might contribute with our work to change our collective future.

As a PhD in US history and a PhD in education we are aware that most doctoral programs in education do not train students to apply a historical lens in their work, and few history programs offer education courses as part of the PhD curriculum. Our training reflected this pattern.Footnote 5 Over the last few decades, scholars have called on the field of educational history to more fully account for the perspectives of women and People of Color, and to connect history to contemporary educational research and policy.Footnote 6 While a number of scholars answered these calls with important contributions, few have offered a methodological roadmap on how to make these connections. Useful guides exist for initiating a history research project generally, for conducting oral history interviews, and for engaging in qualitative inquiry.Footnote 7 However, to our knowledge, there is no similar guide for conducting archival research in educational history, especially for students pursuing questions about Communities of Color.

This article offers some pragmatic suggestions for conducting archival research, with a focus on education, using examples from our coauthored publications in the Harvard Educational Review; the History of Education Quarterly; a coauthored manuscript in progress; and David G. García's sole-authored book, Strategies of Segregation: Race, Residence, and the Struggle for Educational Equality.Footnote 8 We ground these critical revisionist narratives in our theoretical understanding that People of Color possess and utilize an array of knowledges, skills, abilities, and networks to survive and resist racism and other forms of oppression.Footnote 9 We work to recover the histories of Communities of Color from this theoretical stance. It is indeed a myth that historians do not use theory in their work. Everyone theorizes, but often when writing a narrative some historians feel a separate section or explicit description of theory may take away from the story they are constructing.Footnote 10 Theory is manifest in who we study, what research questions we ask, what sources we utilize, and the narrative that we write and present.

Our transdisciplinary methodology is akin to creating a “bricolage” in qualitative inquiry, because we sift through archival data looking for patterns and themes, but we focus on putting together a narrative.Footnote 11 If we find a piece of evidence from one decade that resonates with something from another era, we may try to identify whether these represent continuities, contestations, or contradictions across time. During this organic process, we engage in due diligence, immersing ourselves in multiple literatures and reaching out to solicit feedback from colleagues, who often suggest additional readings and resources. This intentional dialogue and consideration of an array of scholarly lines of inquiry helps us further develop our theoretical and conceptual lenses and our historiographical knowledge.

History Detectives Working in the Archives

From 2003 to 2013, PBS television produced a series called History Detectives, which often began with an artifact of unknown origin in someone's personal collection.Footnote 12 Across eleven seasons, each episode presented the journey of uncovering the story of the artifact, including following the hosts through their process of archival research, oral history interviews, and analysis of secondary sources. We appreciate the metaphor of history being a mystery requiring a skilled detective who meticulously searches for clues to a more complete story precisely because the process is similar to archival research. We too begin with a research question, or a piece of evidence we want to know more about, and we search for possible archives. For example, a series of internet keyword searches may lead us to identify a finding aid for a specific collection within an archive.

For People of Color, and as Galeano argues, it is not coincidental or accidental that attempts have been made to keep our histories hidden. Official, institutional archives have not always viewed the records of People of Color as worthy of preservation.Footnote 13 Protocols within many institutional archives add to their mystification. Some places required us to use white gloves to handle documents. In contrast, some archives permitted browsing through stacks of original photographs without restriction. Increasingly, collections are being digitized, but many materials we found were only available on microfilm or noncirculating paper copies. Certain locations had strict rules that included a waiting period when requesting original documents according to their location by box and folder numbers, while other places required only a conversation with an individual archivist who facilitated the identification of sources. We have learned to be prepared with options for documenting the materials (i.e., portable scanner, digital camera, and multiple forms of payment for printing and copying).

Many of our students pursuing educational research express a tentativeness about working in an archive. At the end of this article, we offer a working model that we use to visually walk through our initial conversations when we ask students to consider how history methods, and specifically archival research, might add another layer of analysis to their existing research.Footnote 14 Often, once they take on this challenge, they are so excited about what they uncover, we cannot get them out of the archives, and they credit the experience for reenvisioning their projects altogether. Indeed, working with primary sources can lead to new questions and interpretations of our projects.

As the collection of our documents expanded in each of our research projects, we needed to develop a system for organizing and management. We initially organized the hard copies and digitized materials by collection. We found it useful to take detailed notes about the specific references and permissions for use of those records while in the archives. This made it easier to later reorganize the documents chronologically or thematically.

Critical Analysis of Primary Sources

Working in the archives can be exciting, time-consuming, and not always fruitful. For example, in our research about the history of education in Oxnard, California, we searched and sifted through at least a dozen institutional archives and collections over the course of a few years, looking for references to Mexicans, Blacks, Asians, segregation, and schooling.Footnote 15 We examined school board and city trustees’ meeting minutes, photographs, maps, local business directories, unpublished manuscripts and reports, flyers, pamphlets, correspondence, and government records, including census data, property deeds, original court filings, affidavits, depositions, and interrogatories. We also explored English- and Spanish-language newspaper archives, both local and regional, and newspaper clippings within several collections.

We analyze these primary sources critically, as evidence, and also as a form of information constructed by individuals with their own sets of values and purposes. Not surprisingly, in the first half of the twentieth century, voices of White men dominated the local archives. In the Oxnard school board minutes throughout the 1930s, for instance, we identified practices of strategic silence and actions of disregard that effectively omitted Mexican American perspectives, even when these children made up the numerical majority in the schools.

Newspapers

The Oxnard English-language newspaper rarely reported on the Mexican community; it also rendered Mexican women almost completely invisible. At the same time, the alleged criminal actions of Mexican men made headlines.Footnote 16 Newspapers, however, facilitated our ability to follow a chronology of local events and to consider this reporting in relation to national press coverage. Recognizing the need to be critical of this source, we analyzed the article contents, headlines and subheadings, photographs and captions. As we look at whose perspectives are featured, the tone of the piece, and the metaphors invoked, we also consider the article's framing and placement. For example, we found reports about the start of federally mandated busing in Oxnard framed by multiple articles about violent protests against busing in other cities. We study newspapers (e.g., articles, editorials, photographs, political cartoons, and advertisements) similar to media scholars to understand how they reflect and/or reproduce ideological perspectives and what social function they serve within a particular historical moment.Footnote 17 We ask ourselves the following types of questions: Is this article part of a local, regional, or national pattern of reporting on race and schooling? Do the perspectives, images, or metaphors in a given article contribute to a continuity of representation or do they contradict or directly contest a narrative of that time period, or over time? Does a pattern surface when we quantify the number of times a certain phrase appears in the reporting of that time, or perhaps do we see a reverberation of certain wording from a different era? When was the issue of segregation or desegregation considered front page news? What can we surmise from continued misspelling of Spanish surnames?

Legal Cases

The legal case materials posed unanticipated challenges. For example, García sought to understand what led to the Soria v. Oxnard School Board of Trustees desegregation case, which grew out of struggles for justice in the fields and factories for generations of predominantly Mexican agricultural workers.Footnote 18 The case itself was housed at the National Archives in three different cities as well as at the Oxnard School District archives. Tracking down and piecing back together these materials required learning legal terms and court filing processes. Some portions of the case remain missing, but even within the hundreds of pages of documents García recovered, he was frustrated to find a paucity of Mexican American perspectives.

Beyond the initial filings in February 1970 from the parents of the ten Mexican American and African American plaintiffs, the affidavits in support of the integration order were all from Black or White residents, and the trial testimony focused on White school trustees and administrators. The district court's opinion highlighted the trustees’ plans to segregate Mexican children dating back to the 1930s, but the case materials did not capture Mexican American voices from any decade. García followed in the critical tradition of triangulation to recover these missing perspectives. Sociologist Norman K. Denzin explains the process of triangulation as a “combination of multiple methodological practices, empirical materials, perspectives, and observers in a single study [that] is best understood as a strategy that adds rigor, breadth, complexity, richness, and depth to any inquiry.”Footnote 19

A few years later, we applied these methodological insights to our project, which began with our request for a file titled “Galarza, Karla, case” while researching the Soria case in the NAACP collections at the National Archives. We eventually learned that the case was about Karla protesting her expulsion from a segregated Black vocational school in the District of Columbia in 1947. We confirmed that her father, Dr. Ernesto Galarza—recognized as a prolific scholar and trailblazing labor organizer—contributed to a collaborative, interracial effort to end school segregation in the nation's capital. We sifted through ten months of correspondence among legal organizations but found no evidence of Karla's firsthand account. We were also perplexed that even Ernesto Galarza's research memos seemed almost ignored in the legal documents that the different civil rights organizations put forward. Even though we had uncovered quite a compelling narrative, we were driven to more fully account for the ambiguities and silences of this family's story. We collected additional archival sources and conducted oral interviews, including with Karla Galarza's daughter, who shared family photographs and other personal documents. By weaving this evidence together, we were able to construct a more complex, nuanced story. Still, gaps remain in the historical record of the Galarza case, and various lines of inquiry remain unresolved.

This particular archival experience reminded us that school desegregation cases like Soria and Galarza emerge from confrontations between individuals and institutions in a particular time and place. Often, the perspectives of those wanting to dismantle segregation are almost completely omitted from the official records, despite their having inspired the legal intervention. We work to find additional sources that can add depth and breadth to the story and reassert the human experiences of that legal intervention. As we interpret the silences of the archives, we recognize that narratives about race, schooling, and equality are complex, sometimes contradictory, and never complete.

Emerging Lines of Inquiry

Our approach to critical triangulation developed over time and across research projects. For instance, our project on the segregation of Mexican children in Oxnard, California, led us to consider sociopolitical contexts that extended well beyond the city and the local schools. In our collaborative article, “A Few of the Brightest Cleanest Mexican Children,” we focused on school board meeting minutes, oral accounts, and photographs from personal collections. As we continued studying the minutes, we found the trustees repeatedly making geographical references in their plans to segregate Mexican children by readjusting enrollments and neighborhood boundaries. This led us to a new research question of whether the trustees had a vested interest in housing segregation. We made a list of each of the names we saw in the minutes and began with those names at the county deed and recorder. These records revealed numerous school and city officials, and local newspaper publishers, held restrictive covenants on their personal properties. Some burdened entire tracts with long-term, automatically renewable clauses extending racial restrictions well into the 1970s. We returned to the archives to study city maps dating back to Oxnard's founding. Our coauthored piece “Strictly in the Capacity of Servant,” emerged from this process, where we unearthed a purposeful interconnection between school and residential segregation.

Oral Accounts and Personal Collections

García's book expanded on sources we analyzed from our previous articles on Oxnard. He collected additional primary documents and conducted and examined over sixty oral accounts that shed much light on the daily complexities of navigating schools shaped by race, class, gender, and space in ways archival sources could never fully capture. Indeed, these voices reveal the human experiences of segregation omitted in the board minutes, dismissed by the newspapers, or unintentionally silenced in the legal case files. Historian Vicki L. Ruiz notes that oral histories are “not a question of ‘giving’ voice, but of providing the space for people to express their thoughts and feelings in their words and on their own terms.”Footnote 20 Similarly, we work to center respect and reciprocity in the process of conducting oral history interviews. In many ways, we see the participants as collaborators, cocreating knowledge by sharing their precious memories.Footnote 21

The interview protocol focuses on questions about educational experiences but follows a dynamic semi-structured oral history process. Because we sometimes formulate questions from the primary sources, we can generate dialogue between the archives and those who lived during that time and place. Our inquiries about each person's educational trajectories led them to recount stories about segregation well beyond schools, including in housing, jobs, and their daily navigation throughout the city. Very often, our study presented the first opportunity for individuals to grant an oral account of their educational experiences to an academic, and they and their family members were eager to participate as we gathered around their dinner table. This enthusiasm contributed to an intergenerational dialogue within families, who were sometimes learning the painful details of their parents’ or grandparents’ experiences of segregation for the first time.

In the Oxnard project in particular, because the institutional archives have almost erased Mexican American women, García sought to recover a range of women's voices. His careful attention to address this omission led to revelations of distinct elements of gendered racism that girls and boys endured in schools and experiences coming of age in a community segregated by race and class. He also strove to include voices of African American women and men and to identify where parallel and shared narratives may exist with their Mexican American neighbors. His purposeful consideration of race as intersectional and relational in Oxnard benefited our analysis in the Galarza case, where we identified interracial collaborations among friends and colleagues, shaping the legal arguments against school segregation.Footnote 22

We have been honored that many of our interviewees shared documents from their personal collections, such as classroom and family photographs, correspondence, yearbooks, obituaries, report cards, and newspaper clippings. These documents provided a useful resource for visualizing the narratives. With permission and as appropriate, García also utilized these sources during the interview process. For example, participants helped in identifying former classmates and teachers in elementary school photographs. García then tracked their names in newspaper accounts and yearbooks from 1939 and 1943 to chronicle enrollment and graduation patterns.

We provided opportunities for our interviewees to review and correct the transcript, or the part of the manuscript where they were identified and quoted. Most often, they indicated that they stood by what they said and were not interested in reviewing material in progress. We recognize all our interviewees in our publications, whether they are quoted or not, and we follow up by giving each person a copy of the article and/or book.

Presenting oral accounts alongside the archival research also poses methodological questions. How do we present complex narratives within the confines of a professional conference or talk? For one presentation, García abbreviated his talk to include a panel of participants and an exhibit of photographs, turning a book signing into a community event. When technology permits, we feature multiple photographs, maps, and documents, and include audio excerpts of the oral accounts within the PowerPoint slides; in other spaces, we ask for volunteers from the audience to read the quotes. In these ways, we aim to foster intergenerational dialogue and allow the audience an opportunity to engage with the narratives.

Constructing a Narrative from Archival Sources and Oral Accounts

We are intentional about analyzing oral accounts and personal collections alongside and against institutional archive sources. Through our critically reflective process, we sift through the transcripts, looking for themes and patterns of experience, while maintaining our focus on the recovery of a historical narrative. Focusing on the specifics of people's experiences helps reveal everyday forms of protest, self-determination, and community organizing. We also pay attention to where the details of the local story may connect with narratives of race, segregation, and schooling across the region, state, and nation. We are looking to better understand the continuities and contradictions of segregation and resistance spanning time and place. For us, and as Galeano suggests, these considerations reflect our efforts to be responsive to “their roots, their vicissitudes, their destiny,” and to avoid being nostalgic or essentialist, or freezing their experiences in time. We affirm that the collective memory of a community is valid and valuable to the narrative.

Decisions about constructing the narrative also means making difficult editing choices, working to stay within page limits, within the time period of the narrative, or other constraints. When choosing quotes, we are deliberate about recovering and centering women's voices, and at a minimum, explaining that their voices may be missing from the institutional archives. We often open with an excerpt from the archival sources or from an oral account, and as we move across article subsections or chapters of the book, we aim to balance the voices we are featuring to capture the multifaceted story. We may ask: Whose voice introduces us to this book/article/chapter? How do we position women's and men's voices to ensure a family's story is well developed? We go through a similar systematic process with photographs and captions, with the intention to contribute to a more nuanced portrayal of children, families, and communities rather than to replicate a deficit or a one-dimensional framing or description of the visual archives.Footnote 23

Most women in primary sources were referred to by Mrs. or Miss, their first names rarely documented. For his book, whenever possible, García tracked down their first names and decided to initially refer to the women with their maiden surnames, and including their married surname in parenthesis, knowing the maiden name was how the records identified them as schoolchildren. He referred to all his interviewees by their full name, with middle initial, and thereafter by their first name, to convey he was more familiar with them and to remind readers that these were once children navigating schools.

In our interviews, we begin by asking our participants to introduce themselves, and in our write-ups, we respect the ways they self-identify in terms of gender, race, and ethnicity. For example, our participants identify as Mexican, Mexican American, Chicana, and Chicano, often using the terms interchangeably; this is also the case with interviewees who identify as Black and African American. We have sometimes had to insist that these terms not be changed, and we have been asked to justify why we want particular terms capitalized (e.g. “Black students,” “White architects”) regardless of the suggested practices in any given manual of style.

Indeed, we have had to negotiate with journal and press representatives to ensure that the narratives we had painstakingly carved out remained intact during publication. We have pushed back on editorial decisions that we view as diminishing the dignity of the interviewees or that somehow decontextualize or distort the narrative. García also questioned the art department's mock-up of his book cover image because he did not want archival text laid over the faces of the schoolchildren.

On the other hand, our work has been strengthened by editorial feedback and suggestions that have led us to engage in further due diligence. We found dialogue with colleagues extremely useful in the publication process for logistical issues, negotiating editorial concerns, as well guidance on considering bodies of literature we may not have otherwise utilized.

Discussion

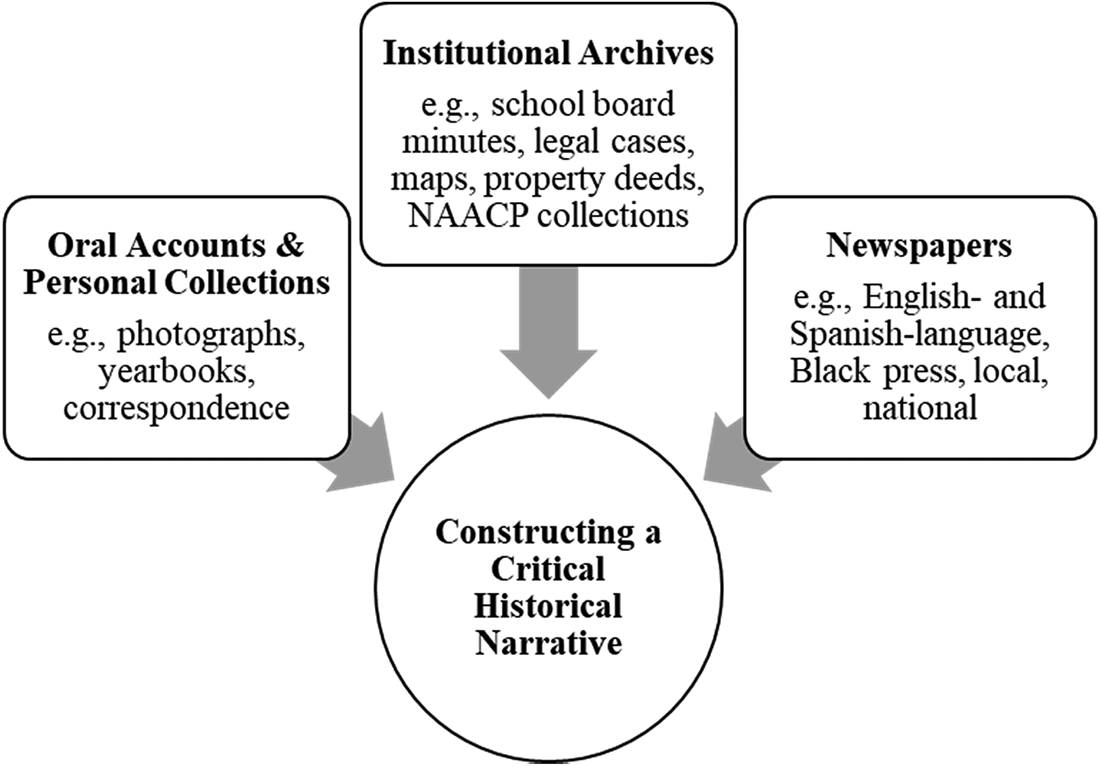

We end this article with a working model we use to begin conversations with students about archival research. We created it thinking about how a good detective film portrays the complexities of solving a mystery with images of multiple notecards, photos, and news clippings tacked to a wall with strings showing the interconnectivity of people, time frames, events, and questions generated by the evidence. While the model may appear static and does not include the actual primary documents themselves, we hope that, along with this article, it can serve as a pragmatic guide for those embarking on the dynamic, organic process of constructing a critical historical narrative.

Figure 1. A working model of sources considered in constructing a critical historical narrative.

Finding archival evidence generates new interpretations and research questions, and ultimately enables us to construct a more nuanced narrative. Newspapers provide us a sense of chronology and lead us to ask multiple questions about how the local and national press contribute to narratives seeking to justify racial segregation. Close critical analysis of local editorial pages, Spanish-language newspapers, and the Black press also reveal protests against school segregation and housing discrimination reverberating across time and place. Oral accounts bring tremendous depth to our understandings of the human experiences of segregation. Evidence from personal collections, especially photographs, help us to visually bear witness to some of the patterns of disparate treatment of Mexican and Black children in US schools. These sources further complicate our narrative, guide our pursuit of additional archival evidence, and sometimes leave unresolved questions. Archival research challenges us to delve into transdisciplinary literatures and methods as well as to find new ways to map educational histories. Investigating evidence that Mexican Americans were restricted to living in certain areas, for example, pushed us to spatially analyze relationships of race, gender, labor, and privilege within and beyond schools. We also studied legal cases across time, looking for when arguments and rationales represented continuities or contestations of court decisions and legislation.

As we engage these time-intensive investigations, we consider it a privilege and responsibility to work with the next generation of scholars seeking to bridge history and education. Inspired by Galeano and so many others who have labored in the struggle to recover our collective past, we recommit ourselves to the work of reclaiming a complex vision of who and what we can be.