Introduction

Hemis National Park of the Indian Trans-Himalayas is known for its rugged terrain, aridity and relative inaccessibility to people other than adventure enthusiasts and indigenous populations. Within the Park there is a dynamic between wildlife and the community of mostly Buddhist famers. This National Park is one of the largest federally-protected areas in the region and supports a high density of Vulnerable snow leopards Panthera uncia (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Sinha, Chundawat and Das1991). However, despite its prominence for wildlife conservation, the Park's rural economy has traditionally been driven by agro- and nomadic pastoralism, which requires the import of large numbers of livestock, supported by occasional hunting of native wildlife (Namgail et al., Reference Namgail, Bhatnagar, Mishra and Bagchi2007a). The Park has become home to increasing numbers of livestock, especially sheep, as a result of the ever-growing demand for pashmina wool (Bhatnagar et al., Reference Bhatnagar, Stakrey and Jackson2000). For similar reasons, the livestock population on the broader Changthang Plateau doubled over a 20-year period following the Indo–Chinese war in 1962, and has continued to increase (Bhatnagar et al., Reference Bhatnagar, Wangchuk, Prins, Van Wieren and Mishra2006).

Not only has the snow leopard's range contracted as a result of human and livestock expansion, but there have been reductions in its natural prey from overhunting (Bagchi & Mishra, Reference Bagchi and Mishra2006). Some prey species, such as the Tibetan gazelle Procapra picticaudata, have undergone a dramatic range reduction in the nearby Ladakh region, and this will impact natural predators (Namgail et al., Reference Namgail, Bhatnagar, Mishra and Bagchi2007a). Prior to the region's development, snow leopards relied on stealth and surprise to take exposed or weakened small- to medium-sized prey (Anwar et al., Reference Anwar, Jackson, Nadeem, Janečka, Hussain and Beg2011), including the Asiatic ibex Capra ibex sibirica, Ladakh urial Ovis vignei vignei, bharal Pseudois nayaur and Tibetan argali Ovis ammon hodgsoni (Mallon, Reference Mallon1991). However, with fewer natural prey available, snow leopards have found alternative sustenance from local livestock (Bagchi & Mishra, Reference Bagchi and Mishra2006), including larger animals such as cattle and horses (Sangay & Vernes, Reference Sangay and Vernes2008).

Although livestock, particularly small- to medium-sized animals, comprise the majority of the diet of most carnivores in the Trans-Himalayan region (Mallon, Reference Mallon1991; Chundawat & Rawat, Reference Chundawat, Rawat, Fox and Jizeng1994; Bagchi & Mishra, Reference Bagchi and Mishra2006), they have been implicated in up to 70% of the snow leopards’ diet (Anwar et al., Reference Anwar, Jackson, Nadeem, Janečka, Hussain and Beg2011). Across the Trans-Himalaya, with few alternative vocations, pastoralism is the norm, and livestock are abundant. Therefore, despite its status as a flagship species for conservation in Asia (Buzzard et al., Reference Buzzard, Li and Bleisch2017), the snow leopard has become one of the most persecuted large felids globally (Bagchi & Mishra, Reference Bagchi and Mishra2006).

Despite the presence of carnivores in this region such as the Tibetan wolf Canis lupus filchneri, lynx Lynx isabellina, wild dog Cuon alpinus and red fox Vulpes vulpes (Namgail et al., Reference Namgail, Fox and Bhatnagar2007b), the snow leopard has traditionally been implicated in the majority of livestock depredation (Bhatnagar et al., Reference Bhatnagar, Stakrey and Jackson2000). This is probably because it is the predator that most commonly enters corrals and night-time holding pens (Bhatnagar et al., Reference Bhatnagar, Stakrey and Jackson2000). Pens have typically been comprised of low-lying rock walls intended to retain livestock, with little regard for keeping predators out. Once inside such a pen, a snow leopard may slaughter many livestock in a single attack. These losses result in emotional distress and financial loss for herders, and often ends in retaliatory killing of snow leopards (Mallon, Reference Mallon1991). Reprisals against carnivores usually include trapping and meat poisoning (Mallon, Reference Mallon1991), and some incidents have resulted in five snow leopards killed for each livestock lost (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Bhatnagar and Mishra2015). These illicit retaliatory events are one of the primary threats to wildlife conservation in the region (Jackson & Wangchuk, Reference Jackson and Wangchuk2004).

Since the end of the Indo-Chinese war there has been an increase of 300,000 livestock in Hemis National Park, with numbers as high as 1,500 livestock per km2. Even the remotest pasture is now being utilized for livestock grazing (Bhatnagar et al., Reference Bhatnagar, Stakrey and Jackson2000). However, although there are more livestock than formerly, grazing a larger portion of the land, they are collectively owned by a greater number of people. Thus, the individual family unit does not necessarily own more animals, and individual families can be devastated by a single loss (Bhatnagar et al., Reference Bhatnagar, Stakrey and Jackson2000)

In 1992 the local government enacted a compensation scheme to help protect pastoralists and wildlife. Yet, in 2000, the compensation only amounted to 10% of the value of the livestock lost, and also required villagers to make long treks to file a report (Bhatnagar et al., Reference Bhatnagar, Stakrey and Jackson2000). In other regions, where cash crops are grown in some pastures, to provide additional income, compensation schemes have been more welcome (Bagchi & Mishra, Reference Bagchi and Mishra2006). In Hemis National Park, however, in the absence of other sources of income for farmers, the first 10 years of the compensation scheme were only marginally effective in lowering the number of livestock killed and the residents’ tolerance of their losses.

As a result of the poor reception of the compensation scheme, alternative strategies to reduce depredation events and retaliatory killings were sought. Corrals were formerly designed to keep stock in rather than to keep predators out (Mishra, Reference Mishra1997; Bhatnagar et al., Reference Bhatnagar, Stakrey and Jackson2000), and > 100 kills can occur in a single event inside a single holding pen (Jackson & Wangchuck, Reference Jackson and Wangchuk2001). A pilot project was therefore initiated in 2002 to enhance predator-proofing of night-time livestock holding pens (Jackson & Wangchuk, Reference Jackson and Wangchuk2004). Concurrently, in 2002, the Himalayan Homestay programme was introduced (Jackson, Reference Jackson and Squires2012), offering training in cooking, hygiene, English, and hospitality and management, while providing loans and start-up funds for renovations (Peaty, Reference Peaty2009). Not only did this programme encourage alternative careers, but the presence and international appeal of the snow leopard led directly to additional income. The holding pen programme was intended to reduce the number of livestock kills, and the Homestay programme was intended to lessen the number of retaliatory kills while also providing alternative jobs in eco- and adventure tourism. These programmes were implemented while hunting was being more tightly regulated.

These programmes are potentially promising for improving the perception of conservation among famers, either on their own or synergistically, and baseline data are needed on the trends and extent of depredation by snow leopards to quantify the success of these initiatives (Bhatnagar et al., Reference Bhatnagar, Stakrey and Jackson2000). Here, we quantify the number of reported depredation events and mass kills in the first 22 years of the compensation scheme, focusing on the 11-year periods before and after 2002, and identify the species and life-stage of prey reported as consumed (Mishra, Reference Mishra1997). In addition, we examine whether depredation events varied with metrics that have not changed over 22 years, such as elevation, ground cover and distance to nearest water sources.

Study area

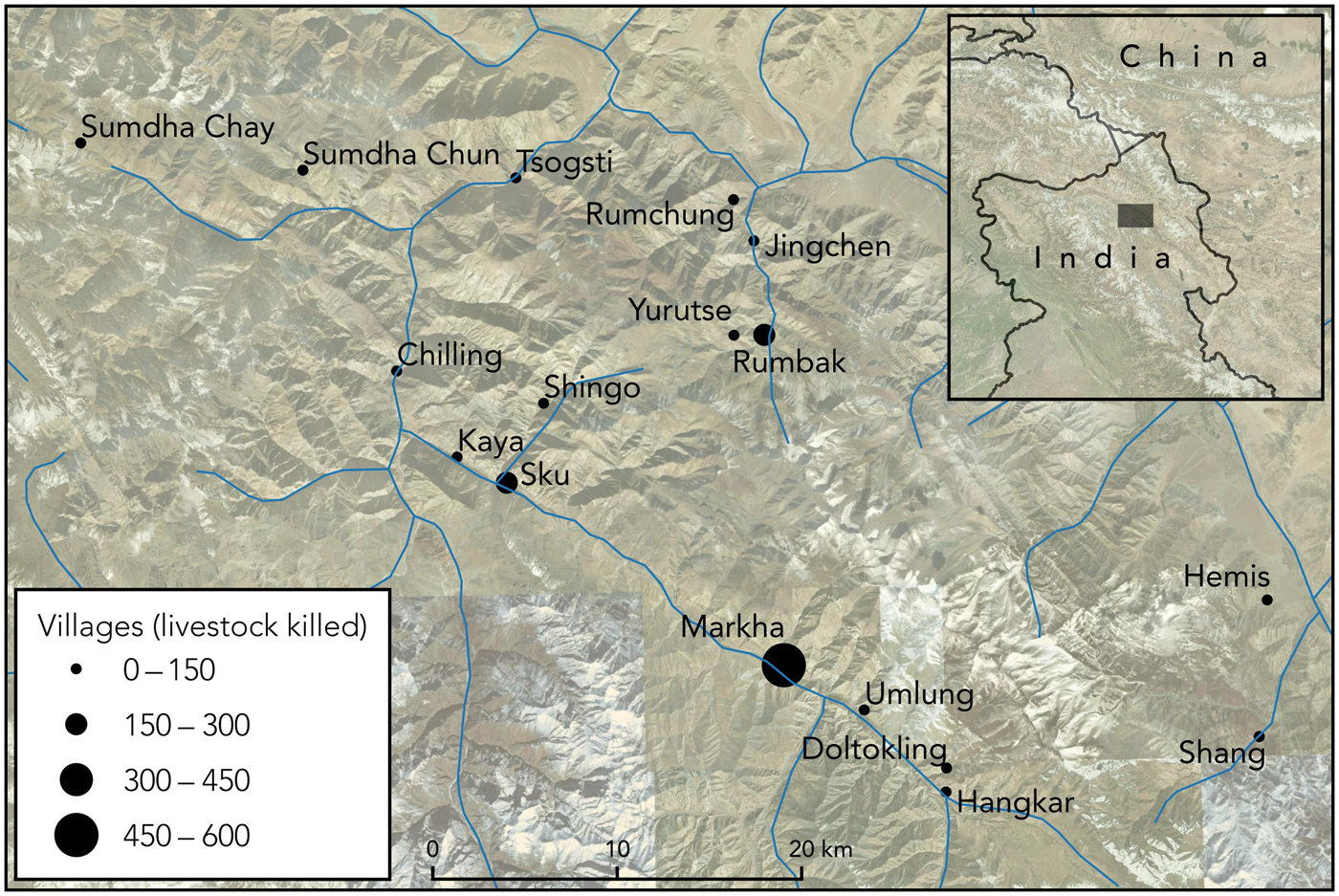

The 4,450 km2 Hemis National Park (Fig. 1) lies at 3,200–6,400 m altitude in Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir, India. In the rain shadow of the Himalayas, this arid region receives < 160.5 mm precipitation per year. Summer temperature highs range from 4 °C in the shade to 30 °C in the sun, and can drop at night to −20 °C, with a mean of 0 °C during daylight hours. High winter snowfall typically leads to the closure of access roads into the area. Vegetation includes riverine scrub Salix–Myricaria–Hippophae, scrub-steppe (Artemisia, Caragana, Juniperus and Lonicera) on gentle slopes, herbaceous and grassy meadow species (Potentilla, Festuca—Stipa, Carex and Kobresia) along valley bottoms in clay soil, and Draba, Rhodiola, Christolea and Saussurea spp. in arid alpine pastures above 4,800 m. The snow leopard Panthera uncia and Tibetan wolf Canis lupus filchneri are the main carnivores, with the lynx Lynx isabellina, wild dog Cuon alpinus and red fox Vulpes vulpes occasionally reported (Namgail et al., Reference Namgail, Bhatnagar, Mishra and Bagchi2007a,Reference Namgail, Fox and Bhatnagarb). There are few cash crops, and livestock are utilized for wool, dairy and meat. The primary livestock are sheep and goats, with some yaks, yak hybrids (dzo, male; dzomo, female) and horses. Almost all livestock are grazed in pastures at higher elevations in the summer, lower elevations in the winter and retained in holding pens at night (Bhatnagar et al., Reference Bhatnagar, Stakrey and Jackson2000). The snow leopard is the only carnivore routinely reported under the compensation scheme.

Fig. 1 Hemis National Park and associated villages, with the total number of depredation events by snow leopards Panthera uncia, as reported per village during 1992–2013 (circle size is proportional to the number of events).

Methods

We obtained records of depredation events and remunerations through the Department of Wildlife Protection, Jammu and Kashmir. We assessed 565 logged entries that included year, name, village, latitude, longitude, type and life stage (adult/juvenile) of animal. The data were collected from Department of Wildlife Protection remuneration surveys administered during January–October 2015 by 15 researchers and 9 wildlife guards who went door to door in 17 villages (Fig. 1). Because of the importance of each kill, and the residents’ ability to maintain records of their losses, this data remains available within each village and family unit. We used data from 1992 onwards because that is when the compensation scheme was initiated.

We used the Kruskal Wallis test (with Minitab v. 17, State College, USA) to examine differences between number of kills, and number of mass killings (defined as ≥ 5 animals killed at one time), before and after the additional initiatives of 2002. We also examined the influence of elevation, landcover and streams on depredation of livestock, using ArcGIS 10 (ESRI, Redlands, USA). DIVA-GIS v. 7.5 (Hijmans et al., Reference Hijmans, Guarino, Bussink, Mathur, Cruz, Barrentes and Rojas2004) was used to extract elevation data from SRTM 90 m digital elevation data (Gorokhovich & Voustianiouk, Reference Gorokhovich and Voustianiouk2006). Land use and land cover data were converted to raster formats, and data for locations of streams were extracted after processing of the Digital Elevation Model.

Results

During the first 22 years of the compensation scheme (1992–2013) a total of 1,624 livestock were depredated from 339 kill-sites. There was a significant difference between the periods prior to and following the additional initiatives of 2002, with a mean of 41 and 3.5 kills per year in the 11 years before and after the initiatives (H(2) = 14.13, P < 0.001; Fig. 2), and also a significant difference in the number of mass killings per year before (5.5) and after (0.5) (H(2) = 11.76, P < 0.001). There were no clusters of kills with elevation, land cover or proximity to streams.

Fig. 2 Total number of reported depredation events, and total number of annual kills (some events included loss of multiple animals) of livestock by snow leopards in Hemis National Park (Fig. 1) during 1992–2013.

Approximately USD 15,000 was paid as compensation over the 22 years. The majority of livestock losses (Table 1) were of goats and sheep (57%), with horses accounting for an additional 13% of all losses. No other livestock species accounted for more than 7%. Juveniles accounted for 4.5% of all losses. More than half of all kills (50.4%; Supplementary Table 1) were reported in January–March, and the fewest kills (11.1%) were reported in October–December.

Table 1 Livestock species/type and life stage (adult or juvenile) for each reported depredation event over a 22-year period (1992–2013) by the snow leopard Panthera uncia in Hemis National Park during 1992–2013.

Among the 17 villages (Fig. 1) there was one hotspot of kills, in the central valley, in the villages of Markha and Sku, where almost half of all kills took place (Supplementary Table 2). During 2012–2013, the numbers of reported kills rose slightly, and goats were replaced by sheep as the prey most often reported consumed (data not shown).

Discussion

We report here a striking reduction in reported depredation of livestock by the snow leopard following initiatives in 2002 that were intended to support the compensation scheme. Reports of the numbers of livestock depredated in the preceding decade, compared to the decade following these initiatives, differed by an order of magnitude. Almost 89% of all kills occurred prior to the 2002 initiatives, with only two mass killings reported since.

Data on the extent of retaliatory killing are unavailable. There is a moratorium on killing carnivores, and thus any individuals reporting this information would either indict themselves or be complicit in the possible prosecution of other pastoralists (Mallon, Reference Mallon1991). However, it is reasonable to conclude that as fewer depredation events occur, public perception regarding conservation will improve, and there will be fewer retaliations against the snow leopard. Thus, the 2002 initiatives appear to have been successful in reducing the numbers of killings whilst also protecting the economic interest of indigenous communities and the welfare of their livestock (Jackson & Wangchuk, Reference Jackson and Wangchuk2004).

Although the success of the initiatives could be attributed to improvements of the night-time holding pens, our measure was animals reported as depredated for compensation purposes. Thus, as simultaneously there was increased income from the Homestay programme, it is possible that more livestock were killed than were reported. For example, villagers may not wish to publicize a depredation event for fear of encouraging retaliatory killing of a species that is now generating income.

Additionally, we do not know how the stricter regulations controlling hunting of snow leopard prey influenced depredation. For instance, the relationship between the numbers of wild ungulates and intensity of predation can be complex: increased populations of wild ungulates may initially result in an increase, and later a stabilization, of populations of snow leopards (Suryawanshi et al., Reference Suryawanshi, Redpath, Bhatnagar, Ramakrishnan, Chaturvedi, Smout and Mishra2017).

We were initially surprised that the majority of livestock reported consumed were adults, because, like most leopards, snow leopards prefer smaller prey (Lyngdoh et al., Reference Lyngdoh, Shrotriya, Goyal, Clements, Hayward and Habib2014). However, killing of juveniles receives less compensation than killing of adults, and thus many killings may have gone unreported. The shift in species depredated during 2012–13 may have been related to a shift in the number and types of livestock. For example, there may now be fewer sheep available as farmers move to larger pack animals to support adventure tourism, and goats are the next smallest potential prey available.

The data we have summarised here appear to support the overall strategic approach of reducing hunting of snow leopard wild prey and retaliatory killing of snow leopards through a combination of improved regulations and night-time holding pens, and the Homestay Programme. However, other factors such as numbers of livestock, species composition of flocks, variation in numbers of natural snow leopard prey, levels of illicit hunting, and tourism pressure may also have influenced our findings. Future research could seek to disambiguate these factors as well as carrying out more in-depth socio-ecological studies to provide additional context for our findings.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Department of Wildlife Protection, Jammu and Kashmir, for permission to conduct this study and for field support, Prameek M. Kannan of Pace University for his valuable support, and Yash Veer Bhatnagar and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions. This project was self-funded by the authors. Amir Javaid of the Institute of Space Technology, Pakistan, and Faith E. Parsons of Columbia University, USA provided GIS services. All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

PSJ and JT designed the study and collected all data. MHP analyzed the data and wrote the article.

Data

The data are available at https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.883303

Biographical sketches

The authors are an international group of conservation biologists working for the Department of Wildlife Protection, Jammu and Kashmir, India, and Fordham University, USA, with a vested interest in exploring, documenting, and conserving nature in under-documented, but critically important, landscapes such as the Western Himalayas. All authors are particularly interested in promoting land use by the rural and traditional communities while positively influencing human–wildlife dynamics.