The development of new scientific domains arises from the interaction of specific inquiry communities, the construction of research objects, and the consequent stabilization through academic associations, teaching institutions, and publishing journals. This process was described by authors with very different approaches, such as Hall’s account of the development of modern science,Footnote 1 or Kuhn’s seminal work on the historical development of a scientific discipline.Footnote 2 Bourdieu’s description of a scientific field also sheds light on such developments,Footnote 3 showing how the social structuring of scientific communities and the consequent power relationships help shape the scientific endeavors. Knorr-Cetina’s concept of transepistemic arenas as the basic sociological unit of the scientific enterprise builds upon the work of the preceding authors (especially Kuhn and Bourdieu) and provides a key support for the analysis of that development, as it proposes that “science” and “politics” are never completely apart and that the production of knowledge includes elements and interactions that extrapolate the closed walls of laboratories.Footnote 4 This is even more relevant when one considers an area with such broad interface with general human affairs, such as public health.

This chapter is an attempt to show some of the threads that were woven into an intricate tapestry over a considerable time span, involving many actors, both individuals and institutions, in order to develop a new, interdisciplinary approach to public health in specific institutional Brazilian settings, even under adverse social and political conditions. Saúde coletiva (collective health) arose from particular historical conditions, as both an intellectual enterprise that drew from traditional social medicine and part of the political resistance to a dictatorial regime, giving it a unique aspect in the global panorama of social medicine.

As Vieira-da-Silva stated in a work that provided much of the background for this text, “one can say that saúde coletiva was born in Bahia, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.”Footnote 5 Here I will focus more on Rio de Janeiro, more specifically using the historical development of a particular research/teaching institution, the Instituto de Medicina Social Hesio Cordeiro (Hesio Cordeiro Institute of Social Medicine, IMS). Part of the Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ, Rio de Janeiro State University), IMS is highlighted throughout the text as a paradigmatic example of the institutional trajectories that took place in the general process. The reference to Rio de Janeiro as a state can be considered as a sort of metonymy; previously to 1975, the key institutions discussed here existed at first at the city with the same name, which was a capital of the country for a large part of its history, becoming a city/state (Guanabara State) in 1960 and later the capital of the recreated Rio de Janeiro State in 1975. Having been the country’s capital, the city concentrated a number of institutions and agencies that played a major role in the development of the field, such as several federal hospitals, one of the larger and most relevant medical research institutions in the country (Fundação Oswaldo Cruz) and three different public universities, all of them with university hospitals and medical schools which provided a Foucaultian surface of emergence for the transformations in traditional public health.

This chapter relies heavily on the in-depth historical works done by colleagues, mostly Brazilian, but also on personal memories of the author as a participant observer of the latter part of the unfolding history of this arena. I opted to keep the term “saúde coletiva” in Portuguese throughout the text, in order to emphasize its specific Brazilian origin.

Political and Historical Background

So as to make sense of the development of saúde coletiva in Brazil, one has to consider the unfolding historical and political context in which it occurred. During the first decades of the twentieth century, there was an incipient organization of workers, in many ways connected to the massive immigration influx from Europe at the final decades of the previous century. This led to the emergence of self-funded forms of social security, initially geared toward pensions and retirement funds, but which included in varying degrees some ways of helping with medical assistance.

Workers’ rights were gradually enshrined into laws, sometimes through paradoxical means. As an example, the creation of the first rudiment of a public social security system was coded into law by a representative who, in 1917, was ahead of public security in the State of São Paulo and violently repressed a general strike. A body of laws encoding several workers’ protections, such as paid vacations, limited working hours, and so forth, was created during the Vargas dictatorship (1930–45), inspired by the Italian fascist Carta del Lavoro (Charter of Labor, 1927). Social security was granted to formally employed workers, through institutions (Institutos de Aposentadoria e Pensão –Institutes for Retirement and Pensions, IAPs) organized according to economic sectors (bank workers, industry workers, sales people, and so on).Footnote 6 Under pressure from their affiliates, those institutes implemented different ways to provide healthcare, ranging from creating their own hospitals and clinics to purchasing care from extant private organizations.

The Vargas dictatorship was responsible for the creation of the Ministry of Health in 1930 (originally as Ministry of Education and Public Health, being split in 1953). Healthcare outside the IAPs was provided by the public sector only for destitute people and was organized along programs geared toward specific conditions, such as tuberculosis or mental disorders. The public sector was in charge of preventive measures as well, especially vaccines.

The construction of the Volta Redonda steel mill in 1942 with US support as part of the negotiation that led to Brazil entering the Second World War on the Allied side is an important milestone in the industrialization of the country. Strategically situated halfway between the then capital, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo, the capital city of the homonymous state, it would play a major role in the development of industrial plants in both areas, a movement which would gain momentum in the following decade, culminating with the introduction of an economic development policy known as import substitution industrialization,Footnote 7 which would have the beginning of a Brazilian auto industry in the late 1950s as a hallmark.

With industrialization came the creation of an urban working class, in contrast with the agricultural workforce that had previously predominated and a massive migration from the fields to larger urban centers, especially the two aforementioned cities. In the span of a generation Brazil went from a majority agrarian population to an urban concentration in the late 1960s, with the consequent problems of increasing substandard housing, overcrowding, and a lack of adequate sanitation infrastructure.Footnote 8 Such conditions favored the emergence of non-communicable chronic diseases in the poor population, which still had to struggle with traditionally poverty-related infectious diseases.

The emergence of an urban working class led to a slow organization of workers and a more active political claiming of better livings conditions, with progressive, left-wing parties playing a major role. Among those, the Partido Comunista Brasileiro (Brazilian Communist Party, PCB), albeit being founded in 1922, was forced into clandestine operation for most of the period. Up to the 1960s, slow progress in social protections, including measures related to health in general, were then a result of workers’ pressure through strikes and organization in unions and ruling elites concessions, even through the dictatorship that marked that period. During this period, a number of workers’ rights were secured, such as a minimum wage, limits to working hours, paid vacancies, and maternity leave, among others.

The combination of social demands and political action created a favorable ground for the emergence of a critical approach to social theory, with a noticeable Marxist influence, which would provide one of the mainstays for the development of Brazilian social medicine. Brazilian social sciences were boosted by the creation in 1934 of the Universidade de São Paulo (São Paulo State University, USP), which hired eminent European professors, such as French scholars Claude Lévi-Strauss, an anthropologist, and Roger Bastide, a sociologist, to kickstart its courses. Some of the most relevant Brazilian intellectuals arose from that university, like Caio Prado Junior (1907–90), a trailblazing Marxist historian, or Florestan Fernandes (1920–95), a pioneering sociologist who played a major role in modernizing Brazilian sociology. This academic lineage would later intersect with the origins of saúde coletiva, by means of the seminal work of Maria Cecília Ferro Donnangelo, as described further on.

The democratic development of the country was halted by yet another military coup d’état that took place in 1964. Detailing all the events that led to and resulted from that coup d’état would go far beyond the scope of this chapter. Suffice to say it marked a clear rupture with the progressive gains of the working class in the previous years. Despite (arguable) economic growth, wages were depressed and the general living conditions deteriorated for the poorer population, with a consequent decline in the overall health of that segment. A hardening of the military regime took place in 1968 (described by many as a “coup within the coup”), leading to a “dirty war” against urban guerrilla groups which never represented a real threat to the dictatorship but served as an excuse for heightened repression, including torture and the “disappearing” of many individuals.Footnote 9

The IAPs were consolidated into a single institution in 1966, the Instituto Nacional de Previdência Social (National Institute for Social Security, INPS). The different IAPs had varying models for providing healthcare for its associates, ranging from fully owned medical facilities to purchase of services provided by the private sector, which were in many cases of poor quality.Footnote 10 The model adopted by the INPS for providing healthcare was for the most part based on the latter, which was facilitated by the resulting large budget derived from worker’s mandatory contributions over their wages now concentrated in one single institution. This model was rife with corruption, as denounced by one of stauncher critics of the public policies in the health sector that were then in place, Dr. Carlos Gentile de Mello (1918–82), who characterized that model as a privatization of profit and socialization of deficits.

Important population movements, such as the migration to cities, coupled with low wages, a lack of investment in infrastructure, and a wholly dysfunctional healthcare system created the perfect storm in terms of challenges to public health. Social disparities became even larger, healthcare was ineffective, expensive, and had many barriers to access.Footnote 11

Healthcare reform became a rallying cry and a spearhead for the struggle for democracy, which resulted in the organization of the Movimento de Reforma Sanitária (Health Reform Movement, MRS), which would become a focal point for both the formulation of public policies and academic development.Footnote 12 This is one of the main axis of articulation of saúde coletiva as a transepistemic arena. The political (or “non-technical”) aspect of the MRS had an immediate policy goal – healthcare reform – as part of a broader alliance that sought the end of the dictatorship. At the same time, the intellectual actors that were part of the movement were active academics, who proposed pertinent “technical” research programs that were at the same time drivers of and driven by the political platform, in close co-production of those aspects and multiple ramifications within the academic world and society at large.

A period of distension began in 1975, leading to a criticized amnesty in 1979 that nevertheless allowed for the return of many prominent political figures who were in exile. The cracks in the dictatorship began to widen as the economy deteriorated, especially after the Mexican default in 1982, in a scenario of economic crisis all over Latin America, which was aggravated by the so-called Structural Adjustment Programs sponsored by the World Bank and the IMF, which further impacted negatively the health of the less affluent strata of the Brazilian population.

In 1982, direct elections for state governors and representatives took place for the first time since 1965, and key opposition politicians were elected in some of the most important states, such as Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio Grande do Sul, a political development that would become very important in the development of the healthcare sector reform that would take place later on.

The opposition to the dictatorship gained momentum at the beginning of the 1980s, with a growing popular pressure to reinstate direct elections for president. The military dictatorship created an indirect system of election, previously unheard in the country’s history, in order to assure a semblance of formal democracy but with a very manipulated electoral college that basically rubberstamped whatever general was chosen by the armed forces, especially the army, to be the next president. The movement to regain the right to the full popular vote was known as Diretas Já (literally, “direct [elections] now”), which peaked with huge rallies in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, having all the main opposition leaders, including the recently elected state governors, and massive popular participation (over a million people were estimated to attend each of those events).

The manipulated election system was put in place by a revised constitution imposed by the military in 1967 and returning to the previous system required a constitutional amendment. Despite gaining a majority of votes, the proposed amendment failed to reach the necessary two-third majority and was rejected. The writing was on the wall for the dictatorship, however, and it would end in the last indirect election in the following year, 1985, which was won by a candidate of the then main opposition party, Tancredo Neves, with a running mate from a split faction of the then ruling party. The latter, José Sarney, would end up as president, after the death of Neves soon before the inauguration, in another bizarre turn of events that punctuate Brazil’s story.

Despite his conservative origin, Sarney had to govern with an elected Congress that had many progressive representatives, and the new Speaker of the House was Ulysses Guimarães, one of the most prominent figures in the resistance against dictatorship, who played a major role in the Diretas Já movement.

A milestone in the return of democracy was the elaboration and approval of a new constitution to replace the authoritarian version imposed by the military. This task was undertaken by the newly elected Congress, led by Guimarães. The struggle for including in the new Constitution advances in social protections, including the health of the population, the important participation of the Movimento de Reforma Sanitária. This resulted in the effective adoption of many of the propositions of that movement in the final text.Footnote 13 Once again, this political achievement was heavily influenced by academic works, showing the hybrid nature of saúde coletiva. A document elaborated by IMS professors was at the same time the basis for a political platform that seeded those policies and the result of accumulated reflection within the academic circles.

The 1988 Constitution, Article 196, states: “Health is a right of everyone and a duty of the State, warranted through social and economic policies that aim to reduce the risks of diseases and other offenses to health and to provide universal and equal access to the actions and services for its promotion, protection, and recuperation.”Footnote 14

This provided the institutional platform for the development of the Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), the Brazilian National Health System, as proposed by the Movimento de Reforma Sanitária. This development will be further explored.

The Development of Public Health

Traditional Brazilian Public Health has a longer history, with remote antecedents that can be traced back to the colonial period,Footnote 15 and even more so after a major historical milestone, when the Portuguese Royal Court, escaping from the Napoleonic invasion, moved to Brazil in 1808, effectively making the colony the seat of the Portuguese Empire. During that year, many key institutions were created on Brazilian soil, in particular the first medical schools, providing among its graduates the first local intellectuals who would concern themselves with the health of the population, albeit from a very conservative and racist point of view, concerned with the “Brazilian race” and the purported negative impacts of miscegenation with the large population of enslaved people of African origin.Footnote 16

This school of thought gained even more traction after Brazil’s independence in 1822. Many of the theses produced by the graduating physicians by the end of the nineteenth century were concerned with one of the key pillars of traditional public health, the hygiene of populations, conceived in a broad sense that encompassed the aforementioned racist theories and normative views on families and upbringing children, including, but not limited to, elementary school curricula and furniture.Footnote 17

The arguments about the health of the population, especially in the (then) capital city of Rio de Janeiro had an important economic component, given that it was the most significant port, playing a key role in the economy of the young nation. The poor sanitary conditions of port cities was a cause of distress throughout the Americas and a motivating factor for the creation of the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO),Footnote 18 which would have an important role in the development of public health in Brazil, with a long tradition of partnerships and support for various governmental and academic initiatives. A Brazilian physician, educated in modern microbiology at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, played a crucial role in the sanitization of the city: Oswaldo Cruz (1872–1917).Footnote 19 With good reason, he is considered a kind of patron saint of Brazilian public health and was the founder of one of the most prestigious Brazilian research institutions in health, the Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Fiocruz), which bears his name for obvious reasons. Cruz introduced new, science-based practices in the management of the health of population, having as one of his greatest accomplishments the eradication of yellow fever in the country’s capital at the beginning of the twentieth century. This, however, was achieved with somewhat forceful means which included the forced eviction of poor people from substandard housing and the tearing down of considerable areas in the city, acting jointly with its mayor, Francisco Pereira Passos (1836–1913), a policy that became popularly known as bota abaixo (loosely translated, “tear it down”). This was met with resistance from the population, translated, for example, in riots against the mandatory smallpox vaccination in 1904.Footnote 20

The early years of the twentieth century (1910s–30s) were also marked by the activities of the Rockefeller Foundation, especially in the State of São Paulo, where it helped to create what became later (1945) one of the most relevant teaching and research institutions in public health in the country, the Faculdade de Saúde Pública (Faculty of Public Health).Footnote 21

The deterioration of health conditions for a large part of the Latin American population during the late 1960s and 1970s was the background for the development of a local critical approach, inspired by nineteenth-century social medicine and with a strong Marxist influence, the so-called Latin American social medicine.Footnote 22 Social medicine was in a sense a development following the traditional Public Health, but developed against it as well. The critique of the latter was based on its de-politicization of the health status of the population, narrow focus on the biomedical aspects of disease, and disregard for social context.Footnote 23

A key figure in articulating people and institutions in this period was the Argentinian physician and social scientist Juan Cesar Garcia (1932–84),Footnote 24 who, working with the PAHO, was instrumental in fostering several initiatives in the continent, including the creation of the first graduate programs in Social Medicine in the early 1970s in Mexico and Brazil. The graduate programs that were created in Brazil will get more consideration further on in the chapter. Garcia “developed from 1966 to its his death in 1984 important research and analysis on of medical education, social sciences in medicine, the social class determinants in the health-disease process and the ideological bases of anti-Hispanic discrimination.”Footnote 25 Garcia’s role in the origin of saúde coletiva cannot be overestimated. At its inception, the group of intellectuals who would develop both the political and scientific aspects of the field were potential targets of the military regime, at a time where opposing the dictatorship presented serious risks for those involved. The international connections that were developed through his work, as well as the academic nature of the research program that was being nucleated at different sites in Brazil, provided some degree of protection to the field’s founding figures, such as many of those named here. Once again, the intertwining of the political and the academic characterized the transepistemic nature of the emerging field.

The strong Marxist influence was, however, only part of the theoretical kaleidoscope that was forming. The cooperation between a UN organ geared toward economic development (United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America) and the PAHO resulted in a very influential health-planning program,Footnote 26 with a strong Keynesian influence and French philosophers, most notably Michel Foucault, also had a role in the development of this arena, at least in Brazil.Footnote 27

Social medicine in Brazil had among its pioneers a handful of young physicians, among them Guilherme Rodrigues da Silva (1928–2006), Sebastião Loureiro (1938–2021), Hesio de Albuquerque Cordeiro (1942–2020), and Antonio Sergio da Silva Arouca (1941–2003), who played relevant roles both in the establishment of an academic field and the political organization of the public health sector from the early 1970s onward, taking part in the resistance to the dictatorship and subsequently in the rebuilding of democratic institutions.Footnote 28 Rodrigues da Silva created the embryo of what would later become the Instituto de Saúde Coletiva at Universidade Federal da Bahia (ISC/UFBA), and later was at the head of the department of preventive medicine at the medical school of Universidade de São Paulo (USP). Loureiro was one of the key leaderships in the creation of ISC/UFBA; and Arouca was a leader both in the theoretical development of saúde coletiva and in the political arena. With the exception of Arouca, the other three were at some point presidents of the main saúde coletiva academic association, Associação Brasileira de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Coletiva (Brazilian Association of Graduate Collective Health Programs, Abrasco).

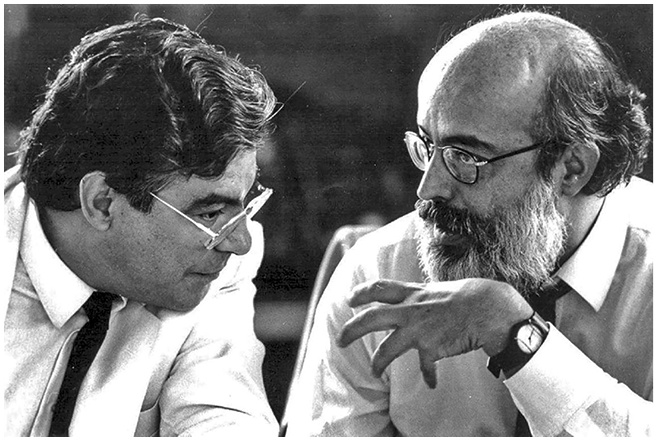

Hesio Cordeiro (Figure 11.1), along with Moyses Szklo (who would later have a stellar career at the Johns Hopkins University) and Nina Vivina Pereira Nunes, all physicians, graduated from the medical school (Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, FCM) of the (then) Universidade do Estado da Guanabara (UEG, later Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro State University, UERJ), under the guidance of Professor Americo Piquet Carneiro, a respected leadership, physician, and professor of that same school, were tasked with the reorganization of what was then the Medical Hygiene discipline at the FCM. This resulted in the creation in 1970 (approximately, there are controversies about the date) of the Instituto de Medicina Social (Social Medicine Institute, IMS, since 2021 Instituto de Medicina Social Hesio Cordeiro, again for rather obvious reasons), as an offshoot of the medical school (although it would take decades for it to acquire its full independence).

Figure 11.1 Sérgio Arouca and Hésio Cordeiro.

The first director of the IMS (1971–8) was a very respected traditional Public Health professor, Nelson Luiz de Araújo Moraes, who had developed a method for the quick assessment of a population’s health status based on its graphic representation of proportional mortality in key age strata. During his tenure as director, Moraes also held the second position in the hierarchy of the Ministry of Health, covering the hardest period of the dictatorship. Given his national prestige, he sheltered the young progressive IMS professors – who had connections to political organizations forced into the underground, such as the Brazilian Communist Party – from the repressive regime.Footnote 29

The pioneering IMS physicians were very critical of the traditional medical approach and were originally intent on reforming medical education and practice. With the guidance of Juan Cesar Garcia, Cordeiro complemented his studies in the US and returned to Brazil to continue his career. His Master’s thesis as well as his doctoral dissertation were both published as books,Footnote 30 and had a seminal role in the field. He was one of the first Brazilian authors, if not the first, to develop the concept of the medical-industrial complex as a critical tool.

A key feature of the budding field was its intense interdisciplinary dialogue. The aforementioned physicians started a nucleation process that aggregated researchers from other areas, notably from the social sciences. An important pioneer was Maria Cecília Ferro Donnangelo (1940–83), a professor at USP’s Department of Preventive Medicine, whose Master’s and doctoral works explored the connections between living and working conditions and the health–disease processes with a Marxist perspective.Footnote 31

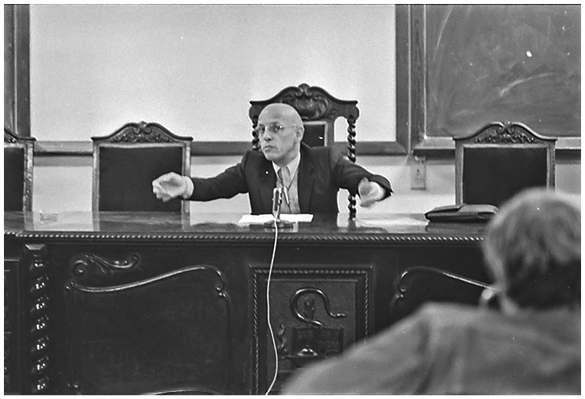

In the early 1970s, the first graduate programs in Public Health were created, mostly at the Master’s level, with the IMS beginning its Master’s program in Social Medicine – the second in Latin America – in 1974. The beginning of the program was marked by a series of lectures given by none other than Foucault himself (Figure 11.2). This program had international support (funding from the Kellogg Foundation and the PAHO) and, paradoxically, from Brazilian government agencies, despite the authoritarian nature of the regime and the inherently critical approach of the research program.Footnote 32

Figure 11.2 Michel Foucault lecturing at the Instituto de Medicina Social.

The newcomers to the field with a background in social sciences and humanities were responsible for the introduction of the work of important French authors, such as Pierre Bourdieu and Foucault. In the case of the IMS, a key role was played by Roberto Machado (1942–2021) a prominent philosopher who worked there from 1974 to 1978. Machado was a disciple and friend of Foucault as well as the translator of his books to Portuguese. He was responsible for the invitation that resulted in the aforementioned series of conferences. The IMS counted in its origins with other relevant intellectuals who had a founding role for the whole field, as, for instance, Maria Andrea Loyolla, an anthropologist; Madel Luz, a sociologist and philosopher; and Jurandir Freire Costa, physician, psychoanalyst, and philosopher. All of them had strong ties with French-speaking institutions and were responsible for introducing those authors to the fledgling saúde coletiva field. Luz, in particular, after obtaining her Master’s degree in Louvain, Belgium, went on to a doctorate in Political Science at USP, with a doctoral dissertation that dissected the origins of the IAPs, with a theoretical approach that connected Gramsci and Foucault. Soon after it was published as a book, it became a classic reference.Footnote 33 The infusion of diverse theoretical approaches was in general well received and integrated into the body of knowledge that was being formed.

By the late 1970s, a discomfort with the “Social Medicine” moniker became prevalent; it was perceived as excluding from the field all the other researchers who were not physicians. The name “saúde coletiva” (collective health) emerged and was slowly adopted in the field, with a formalization at a meeting of graduate programs that occurred in 1978.Footnote 34

The creation of institutions that congregated researchers in the field was an important milestone of that period, with the Centro Brasileiro de Estudos de Saúde (Brazilian Center of Health Studies, CEBES) arising in 1976 and the Associação Brasileira de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Coletiva (Brazilian Association of Graduate Collective Health Programs, Abrasco, later just Associação Brasileira de Saúde Coletiva for greater inclusiveness), founded in 1978, became important focal points for the development of knowledge and political action.Footnote 35

The role of progressive physicians in the creation of what would later be saúde coletiva meant that healthcare was from the start an integral component of the field, marking one important distinction from a more traditional conception of Public Health and arguably even Social Medicine at large. The development of a network of primary care facilities in Montes Claros, a medium-sized city in the State of Minas Gerais, in 1975 is considered a milestone of the development of healthcare models that contemplated both the managerial and service delivery aspects, serving as the prototype for a countrywide program to further extend primary care to a wider share of the population.Footnote 36 This program was coordinated by Francisco de Assis Machado, yet another physician with a relevant participation in the constitution of the field. The connection with the medical profession had repercussions in the development of community and family medicine in Brazil. As an example, in the specific case of UERJ, which has had a seminal role in that area,Footnote 37 the key leaders of its development, such as Ricardo Donato Rodrigues and Maria Inez Padula Anderson, obtained their Master’s and PhDs at IMS/UERJ.Footnote 38

The implementation of graduate courses in the area that would later be termed “saúde coletiva” began in 1971 and until 1989, counted only with 5 programs. In 2018, however, it had been expanded to a total of 93 programs, albeit with a skewed distribution in the national territory, with a great concentration in the most affluent parts of the country.

In the early (pre-1990s) years, given the scarcity of doctoral programs in the country, many individuals sought those in other countries, especially the US and the UK, to complement their academic development, bringing diverse collaborations with other researchers from all over the world.

The overall field tended to coalesce along three main axes: Epidemiology, Social Sciences and Humanities in Health, and Health Planning and Management, with different traditions in terms of methods, priorities, and publishing patterns, sometimes threatening the integrity of the field as a joint enterprise and its interdisciplinary character.

This expansion shows the academic mainstreaming of the field, which consolidated its position as a scientific domain, although this has brought some trade-offs as well, linked to how academic hierarchies are established in Brazil.

Graduate programs in Brazil are strictly regulated by the Ministry of Education, specifically by the Comissão de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Commission for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, CAPES), which holds regular evaluations of all the graduate programs (Master’s and doctoral) in the country. The evaluation process relies heavily on numeric indicators and those related to scientific publishing have great weight in the final result. This means that those who publish more tend to be better evaluated and this somewhat skewed the better grades toward the epidemiologists, creating resentment among the other subdomains and further threatening the unity of the field.Footnote 39

The greater academic emphasis may have dulled the political edge of the field as a whole, which lost some of the political capital that it held during the struggle for healthcare reform.

In the case of the IMS, the original Master’s in Preventive and Social Medicine, which was for institutional reasons grouped with other Master’s programs in Medicine, was replaced by a Master’s in saúde coletiva in 1987.Footnote 40 Whereas the previous program only admitted physicians, the new one was open to all kinds of undergraduate studies, which were more in-line with the interdisciplinary nature of its faculty, which included sociologists, anthropologists, philosophers, economists, psychoanalysts, and demographers, among others. In 1991, a doctoral program in the same area was created, showing the maturity of the institution.Footnote 41 In the same year, the IMS started a regular journal, Physis, which is still going strong.Footnote 42

The first generation of IMS professors was very active in the political scene; aside form Hesio Cordeiro’s tenure at the helm of INAMPS (and later president of the university), Nina Pereira Nunes was subsecretary of the State Health Department in the first freely elected state government in Rio de Janeiro after the 1964 coup; José Carvalho de Noronha was secretary of the State Health Department at a later date; Reinaldo Guimarães headed a research funding agency, Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (Funding Authority for Studies and Projects, FINEP); and Maria Andrea Loyolla was president of CAPES. As the academic aspect of the institution gained more weight though, there was a considerable reflux in the participation of its professors in the general political arena, despite some participation in several Abrasco administrations, including a recent presidency (Gulnar Azevedo e Silva, 2018–21).

The Sistema Único de Saúde – Brazilian National Health System

As stated before, throughout the military dictatorship, as the field itself self-organized and matured, saúde coletiva actors played a significant role in the opposition to the regime, with systematic criticism of the overall health status of the population and the proposal of alternatives for prevention and healthcare functioning as a spearhead in the struggle for democracy. The CEBES, as previously stated, was one of the focal points of that process, publishing books by many of the relevant organic intellectuals of the movement and, since 1977, its own journal, Saúde em Debate (Health in Debate), which still runs today.

In 1980, a position paper, titled “A Questão Democrática na Área da Saúde” (The Democratic Issue in the Domain of Health) was published in Saúde em Debate in the name of the organization – its authors were not disclosed until much later: Hésio Cordeiro, José Luis Fiori, and Reinaldo Guimarães,Footnote 43 all of them IMS professors. That document consolidated the critiques and proposals of the Movimento de Refoma Sanitária and the field of saúde coletiva in general, becoming a kind of blueprint for many of the discussions that came afterwards. It contained a scathing – and accurate – critical assessment of the Brazilian populations’ living standards: infant mortality was increasing, as were several chronic conditions, work-related accidents, and traditional endemic diseases. At the same time, public sanitation was deteriorating, environmental pollution was becoming worse, and nutritional levels were alarming, linked to what was dubbed “absolute [economic] misery.” It pointed to the need to reformulate the economic model, to buttress social security, and to provide government-backed health protection and care for the whole population.

The ideas contained in that document were instrumental in shaping the discussions of the 8th National Health Conference, which took place soon after the end of the dictatorship, in 1986. The National Health Conferences (Conferências Nacionais de Saúde) were huge assemblies with representatives from health professionals, civillian society, and government organizations, having as their objective formulate political guidelines for the public health sector. They continued to be held during the dictatorship but mostly as political theater, with no actual consequences. The 8th Conference, however, reflected the overall drive of the previous years, with effective popular participation, having Antonio Sérgio Arouca, then president of Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, as its president and counting relevant contributions from Hesio Cordeiro, among others. With the new government, Hesio Cordeiro was installed as the president of the Instituto de Assistência Médica da Previdência Social (National Health Care Institute of the Social Security, INAMPS), the arm of the National Social Security that dealt with healthcare, at that point only for those who were formally employed. One of his first measures as president was opening the doors of the INAMPS-funded care to all Brazilians, regardless of the occupational status. This implemented in practice one of the main tenets of the Movimento de Reforma Sanitária: that access to healthcare should be universal, for all citizens. Other proposals were to have a unified system instead of complexity.Footnote 44

The political directive for the SUS was given by the 1988 Constitution, but the actual implementation began in 1990 with the drafting and approval of laws that would provide the legal infrastructure for its operation.Footnote 45 Despite its shortcomings, mainly related to its chronic underfunding (which worsened in recent years),Footnote 46 it is the largest public healthcare system in the world, in terms of the population that it covers, and has provided in the intervening years a research and testing ground for saúde coletiva practitioners and researchers. It has developed one of the largest and most comprehensive immunization programs and has provided healthcare for millions of Brazilians who would otherwise be destitute. It is still plagued by problems of inequality of access, in high-cost interventions, but has enormously expanded access to care via the Family Health program since the 1990s, with demonstrable impacts on the population’s health.Footnote 47

The SUS is, arguably, the greatest achievement of Brazilian saúde coletiva. Despite being chronically underfunded and threatened in its basic principles by the 2019–2022 administration,Footnote 48 it has provided services for a large part of the Brazilian population that would not have otherwise access to healthcare and prevention, especially during the Covid pandemic, despite the erratic response from the federal government.Footnote 49

What is “Saúde Coletiva,” After All?

Important scholars in the field made valiant attempts to provide a formal definition of saúde coletiva.Footnote 50 As many philosophical problems, finding a single, definite solution has proven elusive, beginning with a key component of the name itself – what is health, for starters? As the French philosopher of Medicine Georges Canguilhem pointed out,Footnote 51 it might not be possible to come up with a definitive conceptual definition but the process of discussing it is, in itself, an important endeavor.

Vieira-da-Silva, whose work was a key reference for this chapter,Footnote 52 took a different approach to this question, relying on a sociohistorical perspective to describe and analyze the constitution of what she defined as a field, borrowing from the conceptual framework created by Bourdieu. According to her, that field had components in academia, politics, and governmental bureaucracy, with the former having a more relevant role in its structuring, which nevertheless had relevant participation from all of those sectors – including actors who transited between them, such as Antonio Sergio Arouca and Hesio Cordeiro.

The hybrid aspect described by Vieira-da-Silva is even better characterized as a transepistemic arena, following Knorr-Cetina.Footnote 53 It encompasses the production of knowledge about the health of populations (but individuals as well), human resources training at various levels and capacities for working in the public health sector, and providing direct intervention in healthcare and prevention. It includes a wide gamut of theoretical perspectives, from epidemiological and biological analyses of the health–disease process to philosophical critiques and analyses of that same approach, and is very inclusive in terms of the professional trajectories of its participants, after an initial development nucleated by physicians pushing forward the traditional boundaries of public health and clinical medicine.

This is reflected in the structuring along the three sub-areas or subdomains previously cited, taken as a canonical organization by the majority of the actors in the arena, with some other themes, such as environmental or workers’ health drawing from the three main subdomains. Whether this characterizes multi/inter/transdisciplinarity is another (quite likely endless) discussion in itself, with different views expressed by different authors. It can be said, though, that that this rich mix of theoretical and professional perspectives has over time experienced a certain degree of fragmentation and many opportunities for true interdisciplinary work have been missed as a result. The variety of theoretical approaches adopted in the area is not without its own contradictions; Marxist and Foucaultian approaches, for instance, can be at odds with each other. This essential tension (paraphrasing Kuhn), however, can be – and has been – very productive in terms of the development of critical approaches that continuously challenge established views about how to solve the health problems of diverse populations, providing innovative solutions for them.

It values a critical, reflexive approach to the problems within its domain and has a strong ethical/political commitment to social justice and equity. As an academic–bureaucratic–political arena, it has provided important services for the Brazilian population, especially among those for the design and implementation, always ongoing, of the SUS, despite the numerous setbacks it has faced, especially in recent years. The connection with the provision of healthcare on the one hand, and with organized segments of the civil society (such as the Movimento de Reforma Sanitária) on the other, is arguably the major distinctive trait of saúde coletiva as it developed in Brazil.

The term “saúde coletiva” originated in Brazil, has spread to other Latin American countries, especially Argentina, where it was adopted (as “Salud Colectiva”) in graduate programs which have professors who had part of their own studies in Brazilian institutions.

The creation of IMS in 1970 as an offshoot of the medical school of the same university, the beginning of its graduate program in 1974 and later expansion, and the participation of many of its professors in major health-related political events is singular but at the same time representative of the institutional trajectories in saúde coletiva.

The previous pages barely scratched the surface of a rich and complex history; many important actors were not mentioned and relevant developments related to the area, such as psychiatric reform or the national AIDS program, were not included in the narrative. Nevertheless, they provide an overview of the development of a complex network of individual and institutional actors, who have deeply impacted the country’s health policies.