Introduction

The main objective of the EU state aid regime is to ensure the functioning of the internal market (European Commission 2016). In order to do this, the Commission has been attributed far-reaching competences to see to the correct application of state aid rules by member states in order to prevent the distortion of competition. Its assessment of member states’ state aid plans is often presented as being objective, expertise-driven, and insulated from political pressure, a mode of governance often referred to as ‘technocratic’ (e.g. Radaelli Reference Radaelli1999; Majone Reference Majone2002; Rauh Reference Rauh2016).

However, this technocratic model does not always seem to correspond with the everyday functioning of the regime. For example, the impact of its own priorities may lead the Commission to take a stricter enforcement approach, as was the case in the Commission’s initiative to start in-depth investigations on beneficial tax treatments to multinational corporations in 2014 (European Commission 2020a). In other situations, such as the 2008 financial crisis and the current COVID-19 crisis, the need to secure member state support induced the Commission to adopt a more lenient enforcement in approving the bailing out of financial institutions and other undertakings (Botta Reference Botta2016; European Commission 2020b).

This alternative view is also brought forward in in the political science literature on state aid in which it is argued that the development and functioning of the regime is not guided by technocratic standards alone. Several authors have pointed at the relevance of political factors, including member state characteristics, in the development of the regime (Doleys Reference Doley2013; Kassim and Lyons Reference Kassim and Lyons2013; Aydin Reference Aydin2014) and in the enforcement of state aid rules in individual cases (Thielemann Reference Thielemann1999; Featherstone and Papadimitriou Reference Featherstone and Papadimitriou2007; Finke Reference Finke2020). However, other studies have concluded that the impact of political considerations on enforcement in individual cases was limited to substantive policy preferences of the Commission, and that enforcement outcomes were mostly dependent upon managerial factors (Van Druenen and Zwaan Reference Van Druenen and Zwaan2021; Van Druenen et al. Reference Van Druenen, Zwaan and Mastenbroek2021). The impact of these managerial factors on variation in enforcement outcomes supports a more technocratic view. In sum, it remains unknown what exact role political factors play in enforcement or how this effect is conditioned by technocratic factors.

This question about the interaction of political and technocratic factors in determining outcomes not only touches upon debates in EU studies about different modes of Commission enforcement in policy-specific procedures (see e.g. Schmälzer Reference Schmälter2018; van der Veer and Haverland Reference Van der Veer and Haverland2018), but also, more broadly, upon core questions about the nature of policy-making; whereas we do know that policy-making processes cannot be portrayed as being either merely rational or political, our understanding of how these modes interact remains limited.

In order to improve our understanding of this interaction, this study examines what combination of technocratic and political conditions affect the (non-)approval of state aid to national airlines. Aid to national airlines in difficulties constitutes a most likely policy domain for the impact of political conditions on Commission’s decisions in the state aid regime. The survival of national airlines, also referred to as ‘flag carriers’ and characterised by being (previously) publicly owned undertakings, is considered to be crucial to national economies and is associated with significant public attention as these airlines often provide employment to a large number of employees, both directly and indirectly. This makes it unlikely that member states will easily accept Commission attempts to prevent state intervention. On the other hand, the Commission will not easily back down as these state aids can be highly distortive for competition on the European aviation market.

This political nature of state aid to national airlines became strikingly apparent from the 1990s onwards, when liberalisation of the EU air transport sector led to a radical transformation of the EU aviation market’s structure. Whereas this market was traditionally dominated by publicly owned national airlines, liberalisation has enabled the rise of low-cost carriers such as Ryanair and EasyJet (Jones and Sufrin Reference Jones and Sufrin2016: 176). As national airlines started to experience serious financial problems due to these changing market conditions in the 1990s, member state governments decided to step in by granting state aid to these airlines to avoid their bankruptcy. The Commission decided to approve most of these interventions. However, in doing so, it was criticised for not basing these decisions on objective standards, but ‘on the basis of what looks very much like national pressure’ (Cini and McGowan Reference Cini and McGowan2009: 188).

State aid to national airlines in difficulties has become a controversial issue ever since. The financial crisis of 2008 further deteriorated the financial position of some national airlines and, during the COVID-19 crisis, member state governments decided to massively support national airlines, in order to prevent them from going bankrupt. The decisions to spend billions of public money on ‘flag carriers’, such as Lufthansa, KLM and Air France, were heavily criticised for these aids being disproportionally generous and for a lack of strict economic and sustainability conditions attached (Larger et al. Reference Larger, Saeed and Posaner2020; Posaner Reference Posaner2020).

Because of the contested nature of aid to national airlines, the impact of political factors and their relationship with technocratic factors is most likely to be uncovered in this type of cases. By examining these cases, this study aims to answer the research question under which political and technocratic conditions the Commission does (not) approve state aid granted to national airlines in difficulties by EU member states.

To answer this question, this study utilises crisp-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (csQCA). The reason for employing QCA is that this technique allows us to deal with complex causality (Rihoux and Ragin Reference Rihoux and Ragin2009). It does this by testing for different combinations of conditions – also referred to as configurations – and allowing for the coexistence of non-exclusive explanations. By allowing for complex causality, the interaction between technocratic and political factors in determining outcomes can be uncovered.

The case selection consists of all 14 cases in which the Commission assessed the legality of alleged state aid to national airlines under the Rescue & Restructuring (R&R) guidelines between 2004 and 2019. While nine of the measures assessed by the Commission were approved, five of them were decided on negatively, leading to bankruptcy or the establishment of new airlines. 2004 was chosen as a starting point because this moment coincides with the introduction of the first R&R guidelines that are the basis for the Commission’s assessment of state aid to national airlines.Footnote 1 From this moment onwards, all state interventions related to undertakings in difficulties had to be assessed on the basis of a standardised set of objective rules brought together in one transparent assessment framework. 2004 also coincides with the accession of Central and East European member states and the enlargement of the internal market, which forced national airlines – both from the EU-15 and new member states – to compete on a truly European-wide market. The interval ends before the COVID-19 crisis hit (December 2019), as the assessment of restructuring aid during the crisis took place in the different context of the COVID-related ‘Temporary Framework’. This Temporary Framework consists of different legal parameters to determine whether aid can be approved. This means that the technocratic parameters which were the basis of the assessment of all aid to national airlines before and after the pandemic hit cannot be meaningfully compared.

An additional argument for focusing on state aid to national airlines in difficulties is that it forms a category of aid in which the characteristics of state aid measures are relatively similar; airlines are all competitors within the internal market confronted by the same financial problems stemming from similar EU-wide market conditions and the design of state aid policies is relatively similar; these mostly constitute contributions to restructuring plans in the form of loans or capital injections. This has the consequence that it allows us to control for the impact of market-specific and most policy-specific factors in the assessment of Commission decisions.

Apart from the relevance of this study for broader debates about the interaction of political and rational modes of policymaking, this study contributes to the literature in two more specific respects. Firstly, this study improves our understanding of the day-to-day functioning of the EU state aid regime. Whereas most studies on the EU state aid regime have focused on the regime’s development through time (e.g. Smith Reference Smith1998; Cini Reference Cini2001; Doleys Reference Doley2013) and the impact of EU state aid control on aggregate national state aid spending (Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2010; Franchino and Mainenti Reference Franchino and Mainenti2013; Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2013), this study adds to the developing literature on enforcement in individual cases (Finke Reference Finke2020; Van Druenen and Zwaan Reference Van Druenen and Zwaan2021). More specifically, this study sheds light on the interaction between political and technocratic factors in enforcement, which is still absent in literature.

Secondly, whereas we do know that Commission behavior in enforcement, and more specifically in the so-called infringement procedure, can be driven by political motives (e.g. König and Mäder Reference König and Mäder2014; Fjelstul and Carrubba Reference Fjelstul and Carrubba2018), whether and to what degree this also applies to more legalised regimes, such as the EU state aid regime, is less clear. By uncovering the impact of political factors in relation to technocratic factors, this study contributes to a better understanding of the Commission’s nature as enforcer of rules (i.e. a technocratic or political one) in EU governance.

Section 2 gives an overview of how R&R aid to airlines is formally assessed by the Commission within the state aid procedures. This is followed by a presentation of different technocratic and political conditions that may account for different enforcement outcomes in Section 3. Section 4 consists of a discussion of the case selection, QCA, and the operationalisation and calibration, whereas Section 5 discusses the results of the analysis. These results show that both the approval and non-approval of aid are predominantly dependent upon the Commission’s technocratic assessment: a low degree of market distortion turns out to be sufficient condition for the approval of aid, whereas a high degree of market distortion is a necessary condition for the non-approval of aid. However, in some cases, political factors are decisive in determining enforcement outcomes. Finally, the main conclusions, limitations, and implications of this research are presented in Section 6.

Assessing aid to airlines in the EU state aid regime

EU state aid rules are covered by the Articles 107–109 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). Article 107(1–3) consists of both the general prohibition to grant state aid and exceptions under which granting state aid shall or may be compatible. In addition, Article 108 TFEU regulates the state aid procedures that have to be followed in order to come to the decision that state aid is considered to be legal or illegal.Footnote 2 More specific procedural rules on state aid are laid down in Regulation 2015/1589/EU (European Commission 2013).

Article 108(3) TFEU obliges member states to notify their intention to implement state aid to the Commission.Footnote 3 The Commission then has the sole competence to decide on the compatibility of aid with the internal market in a so-called preliminary investigation. In order to make a thorough assessment of the legality of the state aid under scrutiny, the Commission applies, in addition to the Treaty Articles, specific soft law in the form of guidelines for specific types of aid.Footnote 4 In the case of state aid to national airlines, the Rescue and Restructuring (R&R) Guidelines, which cover aid to undertakings in difficulties in all economic sectors, apply (see next section).

If the Commission has serious doubts about the compatibility of the notified aid measure with the internal market, it has the obligation to initiate a formal investigation under Article 108(2) TFEU (European Commission 2013). In addition, member states sometimes implement aid without prior notification to the Commission. This type of aid is referred to as unlawful aid. Formal investigations can, apart from originating from notified aid, also be initiated as a result of the Commission having serious doubts about compatibility after its own investigation into these allegedly unlawful aids.Footnote 5 Both origins, notified and unlawful, lead to similar formal investigations.

After an in-depth assessment of aid in a formal investigation, including an examination of the information that has been provided by (other) member states and interested parties, the Commission eventually makes a decision. This decision can take two forms. The first option is that the Commission approves a state aid on the basis of adopting a ‘no aid’, ‘positive’, or ‘conditional’Footnote 6 decision. This means that aid can be legally implemented or aid that has already been granted is legally approved. The second option is that the Commission does not approve a state aid on the basis of a ‘negative’ decision. This means that state aid is declared incompatible with the internal market and cannot be implemented or needs to be recovered if it has already been granted.

Explaining the (non-)approval of state aid

What factors can account for the Commission’s (non-)approval of aid? To answer this question, this study builds upon the literature that focuses on the role and motives that drive Commission behavior. From a technocratic perspective, the Commission is considered as a expertise-driven institution that, insulated from political pressures, seeks to formulate policies that are the best long-term solutions to complex societal problems (e.g. Radaelli Reference Radaelli1999; Wille Reference Wille2013; Rauh Reference Rauh2016). By utilising scientific evidence and in-depth analysis, the decisive factor in determining policy outcomes is the objective ‘computational’ application of legal and economic rules, regardless of the political implications of these outcomes (Radaelli Reference Radaelli1999: 764). In the context of the EU, technocracy is often associated with regulatory policies such as those in the domain of EU competition law (Majone Reference Majone2002). Therefore, one would expect technocratic conditions to be good predictors of enforcement outcomes in the state aid regime.

However, other authors argue that the Commission is a political institution whose behavior is also driven by considerations regarding its own interests and position (e.g. Franchino Reference Franchino2007; Hartlapp et al. Reference Hartlapp, Metz and Rauh2014; Nugent and Rhinard Reference Nugent and Rhinard2019). Even though the state aid regime may be highly legalised due to the increasing body of soft law that was introduced in the last decades based on previous decisions and CJEU rulings, the Commission still has a degree of discretion in how it applies state aid rules in specific situations (Cini and McGowan Reference Cini and McGowan2009: 166). This discretion may open up room for political motives to enter the Commission’s decision-making (Doleys Reference Doley2013: 24). On the basis of the EU literature employing principal-agent theory, it can be argued that the Commission is likely to use its discretion to protect and strengthen its position (Wilks Reference Wilks2005; Pollack Reference Pollack2008; Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis2010; Karagiannis and Guidi Reference Karagiannis, Guidi, Zahariadis and Buonanno2017). These considerations may be translated into, on the one hand, strategies to further strengthen its institutional position in line with its role of ‘Guardian of the Treaties’ and, on the other hand, strategies to preserve its institutional position by securing member state support.

In the following subsections, conditions that may affect state aid decisions related to both technocratic and political motives are presented. One of the technocratic conditions, degree of market distortion is hypothesised to be an individually necessary and sufficient condition. The other three conditions, degree of compensatory measures, and the two political conditions, are expected to be INUS conditions (insufficient, but necessary part of an unnecessary but sufficient condition). Therefore, the wording ‘contribute’ has been chosen for hypotheses 2–4.

Technocratic conditions

The main condition for the approval of state aid measures from a technocratic perspective is whether these measures are compatible with the internal market according to relevant Treaty provisions, regulations, and soft law documents. In the case of aid to airlines in difficulties, the most important rules that have to be complied with are the Rescue and Restructuring (R&R) guidelines. These guidelines require R&R aid granted to airlines to be capable of bringing the beneficiary to long-term viability (European Commission 2014a). Initial rescue aid should be restricted to keeping an airline viable for 6 months in order to enable the preparation of a restructuring plan. Subsequently, in order for the restructuring plan to be approved, a member state needs to address two aspects of the state intervention sufficiently: most importantly, the degree of market distortion caused by granting aid and, additionally, the degree of compensatory measures taken by the recipient of aid to promote competition.

Firstly, by decreasing the degree of market distortion, the consequences of a measure for competition can be limited. The degree to which a measure distorts market competition is determined on the basis of the Commission’s assessment of several parameters. As a first step, the Commission assesses whether an intervention should be classified as aid according to Article 107(1) TFEU. An important instrument the Commission applies to do this is the Market Economy Operator (MEO) test: if a member state acts like a private investor in a market economy in providing support to an undertaking, the measure does not constitute aid and the degree of market distortion is limited (European Commission 2016: 18).Footnote 7

In addition, the R&R guidelines bring forward two ‘market distortion’ parameters that have to be met if a measure does constitute aid: (1) an appropriate share of the restructuring costs should be financed by an airline itself in addition to the government’s share; and (2) the airline may not have been a beneficiary of state aid in the past decade, as restructuring aid can only be granted once in 10 years (European Commission 2014b).Footnote 8 This last parameter is often referred to as the ‘one time, last time’ principle.

By consecutively assessing measures on the basis of these different parameters – MEO test, own contribution, and ‘one time, last time’ principle, the Commission determines the degree to which a measure distorts competition. As a result, it can be expected that the Commission will consider a relatively low degree of market distortion as a sufficient condition for the approval of aid, whereas it will consider a relatively high degree of market distortion as a necessary condition for the non-approval of aid. This results in the following hypotheses:

H1a: A low degree of market distortion will be a sufficient condition for the approval of state aid to national airlines.

H1b: A high degree of market distortion will be a necessary condition for the non-approval of state aid to national airlines.

Secondly, by implementing compensatory measures, the aid recipient can mitigate the distortion of competition that is created by granting aid (European Commission 2014b). According to the R&R guidelines, undertakings that benefit from aid may be required to structurally reduce their business activities in markets in which these undertakings have ‘a significant market position’ (European Commission 2014a: 15). In the case of airlines, this is often associated with terminating activities the airlines operates on certain profitable routes. In addition, the guidelines state that the Commission may consider commitments from the undertaking to reduce entry barriers on the market concerned (European Commission 2014a: 16). Applied to airlines, these entry barriers are most often linked to releasing landing slots at economically important airports. Both provisions aim to promote more competition as compensation for granting state aid.

It follows that the Commission is more likely to favorably assess aid that is associated with a relatively high degree of compensatory measures compared to aid that is associated with a relatively low degree of compensatory measures. This leads to the following expectations:Footnote 9

H2a: A high level of compensatory measures will contribute to the approval of state aid to national airlines.

H2b: A low level of compensatory measures will contribute to the non-approval of state aid to national airlines.

Political conditions

In addition to technocratic motives, political motives may also play a role in determining enforcement outcomes. Political motives may, in one view, enter decision-making when the Commission utilises its discretion to further strengthen its own institutional position. In line with its role of ‘Guardian of the Treaties’, the Commission may choose a strategy of deterring member state from engaging in behavior that undermines the Commission’s position. In the case of the EU state aid regime, it can do this by aiming for better compliance with procedural EU state aid rules. In this context, the most important procedural provision is whether the state aid measure has (not) been notified to the Commission before it was put into effect. Article 108(3) TFEU states that ‘the Commission shall be informed, in sufficient time to enable it to submit its comments, of any plans to grant or alter aid’. If such a notification prior to the intention to grant aid is absent, the Commission classifies the state aid measure as unlawful, as it is a violation of procedural rules.

However, the violation of this procedural requirement does not form a ground for declaring a state aid measure illegal. This assessment should only be made on the basis of substantive grounds (i.e. related to assessments on the basis of Article 107 TFEU and guidelines). Nonetheless, the Commission could less favorably assess aid that has been provided unlawfully, as its undermines its position in the state aid regime. In this way, it deters member states from violating procedural rules in the future (Van Druenen and Zwaan Reference Van Druenen and Zwaan2021). Therefore, it can be expected that the Commission will more favorably assess aid that has been notified according to the procedural rules compared to aid that has not been notified according to these rules.Footnote 10 This expectation is captured by the following hypotheses:

H3a: Notifying aid in accordance with procedural rules will contribute to the approval of state aid to national airlines.

H3b: Providing aid unlawfully will contribute to the non-approval of state aid to national airlines.

Secondly, political motives may also enter decision-making when the Commission chooses the strategy of preserving its institutional position by securing member state support. This line of argumentation departs from the point that the discretion attributed to the Commission is especially relevant due to the highly politically sensitive nature of state aid decisions; these decisions target member states directly and are often accompanied with significant public attention (Blauberger Reference Blauberger and Szyszczak2011; Aydin Reference Aydin2014: 28). This means that member states will be unlikely to accept negative decisions easily and may challenge the Commission when this happens (Doleys Reference Doley2013: 27; Finke Reference Finke2020). Therefore, as the Commission’s clout ultimately depends upon member state support, it may decide to utilise its discretion by not pushing too hard.

In EU enforcement studies, this dependence on member state support is often measured by focusing on member states’ political (bargaining) power; as the Commission is more dependent upon more powerful member states, it is likely to refrain from strict enforcement in these member states’ cases (e.g. Börzel et al. Reference Börzel, Hofmann and Panke2012; Blauberger and Schmidt Reference Blauberger and Schmidt2017). However, applied to the state aid regime, results on the effect of member state power are inconclusive (Finke Reference Finke2020; Van Druenen and Zwaan Reference Van Druenen and Zwaan2021; Van Druenen et al. Reference Van Druenen, Zwaan and Mastenbroek2021).

Alternatively, this study incorporates the way member state support affects Commission decisions by focusing on the specific domestic context of a member state. With the increasing politicisation of the EU, the Commission can no longer assume it enjoys public support for its policies (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), and therefore needs to incorporate the domestic implications of its decisions to gain and preserve support of member states. The need to be responsive to these public sentiments is irrespective of member state size. Therefore, it can be argued that the importance of the survival of an undertaking to a member state is crucial in the Commission’s assessment of aid. In the case of aid to airlines, the importance a member state attributes to state aid is expected to be dependent on the economic importance of an airline in difficulties to a national economy, as this is closely linked with directly and indirectly providing employment to a member state’s residents. If the Commission ignores this aspect, it runs the risk of fueling Eurosceptic sentiments and therewith losing member state support.

Therefore, contrary to what would be hypothesised from a technocratic perspective, it can be expected that the Commission more favorably assesses aid granted to national airlines that are of relatively great importance compared to aid granted to national airlines that are of lesser importance to national economies. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H4a: A relatively high level of importance of an airline to a national economy will contribute to the approval of state aid to national airlines.

H4b: A relatively low level of importance of an airline to a national economy will contribute to the non-approval of state aid to national airlines.

Methods and data

Cases of state aid to national airlines

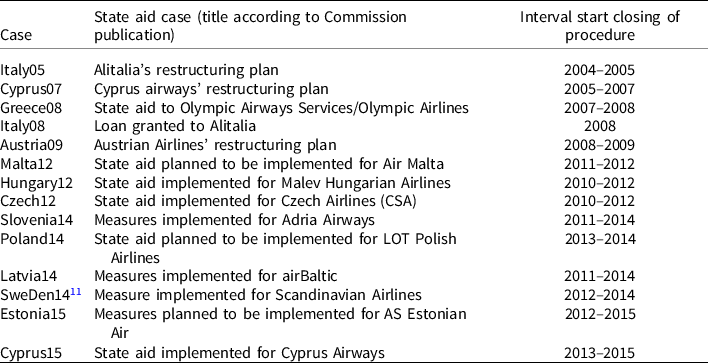

The Commission decisions on all cases were obtained from the State Aid Register (2020). The dataset consists of all 14 cases of alleged state aid to national airlines in difficulties the Commission decided on between January 2004 and December 2019. None of the included decisions led to appeals to the CJEU. These cases have been displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Included cases

Qualitative comparative analysis

The hypotheses in this study are tested by using Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). Employing QCA has the important advantage of allowing us to deal with complex causality (Legewie Reference Legewie2013; Rihoux and Ragin Reference Rihoux and Ragin2009; Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). This means that different configurations of conditions may explain the outcome and non-exclusive explanations can coexist. Thereby, QCA allows for uncovering the interaction between the various technocratic and political factors in explaining the outcome. Another element of this causal complexity is that causal explanations for negative outcomes do not necessarily correspond with reversed explanations for positive outcomes. QCA allows for explaining both positive and negative outcomes. In addition, while a set of 14 cases is too small to execute regression analyses and too large for in-depth case studies, QCA is an appropriate method for analysing this medium-sized set of cases (Ragin Reference Ragin, Box-Steffensmeier, Brady and Collier2008).

The so-called crisp-set approach to QCA (csQCA) that is employed in this study requires the dichotomisation of both the outcome and conditions (Rihoux and De Meur Reference Rihoux, De Meur, Rihoux and Ragin2009: 41). Although the dichotomisation of these conditions – often referred to as calibration – has the downside of losing information richness, this disadvantage is relatively limited in this study; the outcome (approval or non-approval) and one condition (procedure) are naturally binary variables, two other conditions (market distortion and compensatory measures) are based on a multi-step categorisation in the presence and absence groups (see operationalisation), and there is an obvious threshold because of a large natural gap in the distribution of the raw data on the remaining condition (importance to national economy, see operationalisation).

Dichotomised conditions and outcomes enable executing a Boolean minimisation procedure, that allows for specifying the different configurations that can be considered sufficient for causing the outcome (uppercase) or negation of the outcome (lower case) (Rihoux and De Meur Reference Rihoux, De Meur, Rihoux and Ragin2009: 43). In this study, these different configurations were found by executing analyses in the program Tosmana (Cronqvist Reference Cronqvist2019). The decision was taken to interpret parsimonious solutions, because these allow us to make causal inferences about minimally causally relevant configurations, thereby reducing the chance of redundancy. In order to create these most parsimonious solutions, logical remainders were included for reduction.Footnote 12

Operationalisation

The approval of aid (A)

The outcome variable was measured by looking at the decision made by the Commission at the end of its assessment. The outcome was coded as ‘approval (A)’ when state aid measures received a ‘positive or ‘no aid’ decision after assessment in a formal investigation under 108(2) TFEU. The outcome was coded as ‘non-approval (a)’ when state aid measures received a negative decision after assessment in a formal investigation under 108(2) TFEU. If a state aid measure received a conditional decision (i.e. approved but only if specific conditions are met) in a formal investigation, these cases were coded as approval if the conditions attached were not associated with the included components of degree of market distortion or compensatory measures. Data on the outcome were derived from the Commission decisions that can be found in the State Aid Register (Register 2020).

Technocracy: market distortion (MD) and compensatory measures (CM)

The first technocratic condition, degree of market distortion, was measured by consecutively analysing the following elements of a case. Firstly, if the Market Economy Operator (MEO) test was passed according to the Commission, cases were coded as a low degree of market distortion (md). Subsequently, for cases that did not pass this test, it was examined whether granting of aid would violate the ‘one time, last time’ principle according to the Commission. Cases for which this principle would be breached were coded as high degree of market distortion (MD). For the remaining cases, it was assessed whether the own contribution by an airline equaled or exceeded 50% of the restructuring costs according to the Commission. 50% was chosen as a threshold, because of this percentage is mentioned in the R&R guidelines as a threshold for adequacy: “The own contribution will normally be considered to be adequate, if it amounts to at least 50% of the restructuring costs (European Commission 2014a: 13).” Cases were coded as low degree of market distortion (md) if this own contribution equaled or exceeded 50%. If this own contribution was lower than 50%, cases were coded as high degree of market distortion (MD).

The second technocratic condition, the degree of compensatory measures, was measured by determining both the presence of capacity reduction on profitable routes and the presence of slot reductions in coordinated airports. Capacity reduction on profitable routes was present, if the Commission assessed that the restructuring plan included divestment of business activities on profitable routes.Footnote 13 Reduction of slots in coordinated airports – airports in which transport demands frequently exceed capacity – was present if the Commission assessed that provisions on this matter were included in the restructuring plan. Both elements had to be present in order to code cases as high degree of compensatory measures (CM). If one or both elements were missing, cases were coded as low degree of compensatory measures (cm). Data on which the measurement of degree of market distortion and compensatory measures were based, were derived from the Commission decisions that can be found in the State Aid Register (Register 2020).

Politics: procedure (P) and importance to national economy (I)

For measuring the first political condition, procedure, a distinction was made between the intention to implement state aid that is notified to the Commission under Article 108(3) TFEU and state aid that is granted unlawfully without prior notification. Cases were coded as ‘notified (P)’ if aid was classified as notified by the Commission. Cases were coded as ‘unlawful (p)’ if aid was classified as non-notified (i.e. unlawful) by the Commission. If both rescue and restructuring aid were decided on by the Commission, this classification applies to restructuring aid, as this is the most important component of the state aid case. Data on this condition were derived from the Commission decisions that can be found in the State Aid Register (Register 2020).

The second political condition, importance to a national economy, was measured by calculating an airline’s revenues as share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the year prior to the notification (if notified) or implementation (if unlawfully provided) of the aid measure. Cases were coded as ‘high degree of importance to national economy (I)’ if turnover of an airline constituted more than 8% of GDP and as ‘low degree of importance to national economy (i)’ if turnover of an airline constituted less than 8%. 8% was chosen as a threshold, because there is a clear ‘gap’ in the empirical data, with five cases contributing 9% or more and nine cases contributing 5% or less to a member state’s GDP. Data on which the measurement of this condition were based, were derived from Eurostat (GDP per year) and the airlines annual financial reports (revenues) (Eurostat 2020).

Results

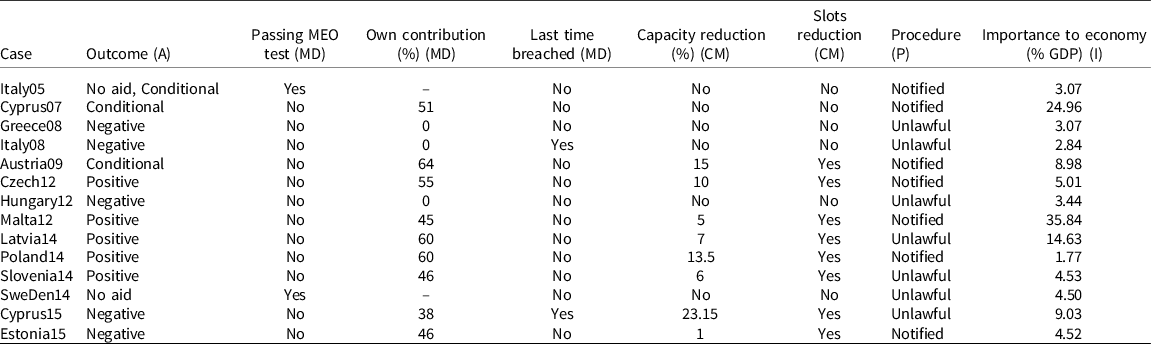

Table 2 depicts the values of all (components of) relevant conditions and the outcome. Each row shows the characteristics of the individual cases, whereas the columns allow for a comparison of all cases on one specific condition. The time period in which these cases were decided on comprises five different Commissions and four different competition commissioners. No systemic differences in outcomes with respect to different Commissions could be observed, which supports the claim that Commission composition does not considerably change enforcement behavior in the state aid regime (see also Van Druenen and Zwaan Reference Van Druenen and Zwaan2021).

Table 2. Raw data matrix

The first step of the analysis was to dichotomise the data on the basis of the operationalisation and calibration criteria presented in Method section. This dichotomisation resulted in a truth table (see Table 3). The detailed calibration process leading to attributing the values of 0 and 1 to the conditions and outcome for each case can be found in Appendix 3. The table shows that 11 of the 16 logically possible configurations were observed and no contradictory configurations – indicating different outcomes for similar configurations – were found.

Table 3. Truth table

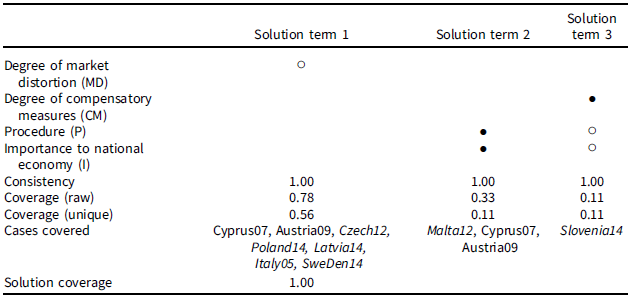

Which conditions and configurations result in the approval of state aid to national airlines? An analysis of necessity shows that no necessary conditions were present. The following step in the analysis was to identify the configurations that are sufficient for observing outcome A (approval). Table 4 depicts the three configurations associated with the sufficient parsimonious solution for this outcome. Firstly, a low degree of market distortion (md) is a sufficient condition by itself for the approval of aid. This solution term is in line with hypothesis 1a and is present in seven out of nine approval cases (‘raw’ coverage 0.78), of which five are uniquely covered (unique coverage 0.56). Secondly, the second solution term shows that notifying aid according to state aid rules is combined with a high level of importance to a national economy (P * I) also leads to approval of aid. This ‘political’ path is in line with both hypotheses 3a and 4a and is present in three out of nine approval cases, of which one is uniquely covered (raw/unique coverage 0.33/0.11). The third solution term, a combination of a high degree of compensatory measures, providing aid unlawfully and a low level of importance to a national economy (CM * p * i) is consistent with hypothesis 2a, but contradicts hypothesis 3a and 4a. This path is associated with one unique case, Slovenia14 (raw/unique coverage 0.33/0.11). This solution term could be explained by the fact that the technocratic condition of including a high degree of compensatory measures is more important than the absence of favorable political conditions in the Commission’s decision making. This strengthens the argument that the Commission’s assessment for approval is predominantly a technocratic one.

Table 4. Sufficient parsimonious solution for approval (a)

●Indicates a condition is present.

○Indicates a condition is absent.

Cases in italics are uniquely covered.

The final step of the analysis was to determine which conditions and configurations result in the non-approval of state aid to national airlines. Table 5 depicts the three configurations associated with the parsimonious sufficient solution for non-approval (outcome a). Firstly, Table 5 shows that a high degree of market distortion (MD) is a necessary condition for the non-approval of aid, as this condition is present in all three solution terms. This finding is in line with hypothesis 1b. The first solution term for non-approval, a high degree of market distortion in combination with a low degree of compensatory measures and a low level of importance to the national economy (MD*cm*i) is also in line with hypothesis 2b and 4b. This configuration is present in three out of five non-approval cases, all three being uniquely covered (raw/unique coverage 0.6). Two other configurations also lead to non-approval: (1) a combination of a high degree of market distortion, notifying aid according to state aid rules and a low level of importance to the national economy (MD * P * i); and (2) a combination of a high degree of market distortion, providing aid unlawfully and a high level of importance to the national economy (MD * p * I). Both cover one unique case, respectively, Estonia15 and Cyprus15 (raw/unique coverage 0.2). These paths do not give a decisive answers about hypotheses 3b and 4b. Instead, these latter two configurations indicate that, in the presence of a high degree of market distortion, the presence of one political factor in combination with the absence of the other political factor leads to non-approval of aid.

Table 5. Sufficient parsimonious solution for non-approval(a)

●Indicates a condition is present.

○Indicates a condition is absent.

Cases in italics are uniquely covered.

Conclusion and discussion

The aim of this study was to shed light on technocratic and political motives of Commission enforcement behavior in the EU state aid regime by explaining under what conditions the Commission does or does not approve state aid to national airlines in difficulties. Therefore, several hypotheses about technocratic and political conditions affecting the Commission’s decisions were formulated. These hypotheses were tested using csQCA on a set of all cases of alleged state aid to national airlines in difficulties between 2004 and 2019.

The results show that both the approval and non-approval of aid are predominantly explained by technocratic factors. A low degree of market distortion constitutes a sufficient condition for the approval of aid (covering 78% of approval cases), whereas a high degree of market distortion is a necessary condition for the non-approval of aid. Aid is also approved if a high level of compensatory measures is combined with unlawfully provided aid plus a low level of importance to the national economy. In addition, aid is not approved by the Commission if a high degree of market distortion is combined with a low level of compensatory measures and a low level of importance to the national economy.

Although the impact of political factors is significantly curtailed by technocratic conditions, evidence was found for their impact in some cases: aid is also approved when notifying aid according to state aid rules is combined with a high level of importance of an airline to a national economy. Furthermore, aid is not approved if a high level of market distortion is combined with the absence of one of these favorable political conditions.

The number of cases in which these political conditions made a difference is limited as, in most cases, technocratic conditions prevailed. So, even in the most likely policy domain for political factors having an effect on enforcement, this effect turns out to be modest. This supports the claim that assessment in the state aid regime is overwhelmingly driven by technocratic considerations. Thus, the impact of political factors seems to be less important than in other enforcement procedures, such as infringements (see e.g. Börzel et al. Reference Börzel, Hofmann and Panke2012; Fjelstul and Carrubba Reference Fjelstul and Carrubba2018).

However, the distinction between technocracy and politics and their operationalisation in this study may underestimate the real impact of politics in determining Commission decisions. After all, the discretion available may not only utilised by incorporating political considerations in its assessment, but may also offer some freedom of appreciation in determining the outcome of indicators on technocratic parameters. For example, the Commission may sometimes have some degree of freedom in deciding whether a measure constitutes aid or not according to Article 107(1) TFEU. If it decides that a measure does not constitute aid, it waives itself from the obligation of assessing the measure on the basis of other legal parameters (such as determining the level of the own contribution) that may be less easily complied with. For example, whereas an in-depth legal assessment of the state intervention in the case of Alitalia and SAS airlines is outside the scope of this study, one can question whether these measures really did not constitute aid. By taking this decision, the Commission may choose a politically more acceptable outcome.

Secondly, the research design only allowed for a limited number of relevant political conditions to be included in the analysis. Although the included conditions seem to be relatively good predictors of outcomes in which technocratic conditions were not decisive, this may result in potentially influential political factors being overlooked. For example, the importance attributed to rescuing flag carriers by member states may not be only composed of economic contributions (e.g. employment), but may also be affected by other issues, such as domestic political competition or identity-related factors, such as national pride related to these undertakings.Footnote 14

The body of political science research on EU state aid policy is likely to grow in the coming years due to the increasing relevance of these policy instruments in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis. The EU’s current ‘Temporary Framework’ that was introduced after the global COVID-19 outbreak in March 2020 leaves more room for member state to support their national economies, indicating that the Commission attempts to accommodate member state pressure without giving up its institutional position (European Commission 2020b), supporting the view brought forward linked to the Commission’s strategy to secure member state support. It would be interesting to study the more recent restructuring aids granted to national airlines in the context of COVID-19 in order to compare enforcement dynamics in this policy domain over time.

Future research should also more specifically focus on the Commission-member state interactions in the state aid procedures and domestic political debates on state aid in (comparative) case studies. This requires more in-depth analysis of Commission and member state behavior as well as more detailed substantive assessment of Commission decisions. This type of research would require expertise in both political science and state aid law. Such interdisciplinary approaches may help us to further improve our understanding of how rational and political modes of policymaking are related in explaining policy outcomes.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X22000010

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/4NYZJM

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Pieter Zwaan, Pieter Kuypers, Johan van de Gronden, Ellen Mastenbroek, and Daniël Polman for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.