Introduction

In 2013, the two largest trading blocs in the world, the European Union (EU) and the United States, launched a free trade agreement (FTA) known by the name of Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). Soon after, in 2014, the TTIP became a very contentious issue in Europe. Public opinion and interest groups across the continent started to mobilize against the agreement on issues such as food standards and state–firms relationship. On 15 July, Karel De Gucht, then EU trade Commissioner, spoke before the European Parliament (EP) about the state of the negotiations. Almost 100 EP Members (MEPs) took the floor, articulating the most different positions, from strong support to absolute contempt for the agreement. Four years later, on 11th December 2018, his successor Cecilia Malmström asked for the EP's opinion on another FTA, this time with Japan. Despite the considerable size of the trading partner and notable differences in regulatory standards with Europe, negotiations did not attract much attention. The parliamentary debate was shorter, less polarized, and MEPs expressed mostly positive opinions for the agreement.

What explains these differences? Why do MEPs (not) support FTAs? Since the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty (2009), the EP is required to give its consent on FTAs negotiated by the European Commission on behalf of the Member States. At the same time, FTAs have started embracing a wide range of topics, not only related to trade openness, but also to services and investments, public procurement, and regulatory measures. Although existing literature has tackled the growing importance of the EP vis-à-vis the European Commission and the Council during negotiations (Ripoll Servent, Reference Ripoll Servent2014; Meissner, Reference Meissner2016; Héritier et al., Reference Héritier, Meissner, Moury and Schoeller2019), to date, there has been no systematic research analysing the lines of conflict in the EP on FTAs. Existing studies either subsume preferences about FTAs in the larger category of ‘external relations’ (Raunio and Wagner, Reference Raunio and Wagner2020) or take into account a rather limited number of agreements (Shaohua, Reference Shaohua2015; Van den Putte et al., Reference Van den Putte, De Ville, Orbie, Stravridis and Irrera2015). Given FTAs' great political and economic impact on states’ economy, businesses, and citizens, investigating the drivers of the MEPs preferences FTAs bears considerable relevance.

In order to address this gap in the literature, the study analyses the speeches delivered by MEPs in all plenary debates over the six major FTAs taking place during the 7th and 8th EP terms (2009–2019). The FTAs involved the following trade partners: United States (TTIP), Canada [Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)], Japan, Mercosur, Australia/New Zealand, and South Korea. On the basis of a manual textual analysis, we build an original and comparable measure of support for FTAs, which we use as a dependent variable in regression models. We hypothesize that competition between MEPs on FTAs builds around two traditional cleavages: position on the left-right axis and support for the EU (Hix et al., Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2006). Findings support our argument: right-wing and more Europeanist MEPs are significantly more supportive of FTAs than their left-wing and Eurosceptic colleagues. In turn, the degree of politicization of the agreements exacerbates these conflicts, by further polarizing positions in the EP. In other words, in highly salient agreements including TTIP and CETA, the gap between left-right and pro-anti EU MEPs is wider.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. After a review of the literature on the post-Lisbon role of the EP in FTAs, we draw our main theoretical expectations concerning the impact of ideological factors in shaping MEPs preference on this issue, and how politicization interacts with them. After that, we introduce the new dataset, and finally we test our hypotheses by means of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models. We conclude with a discussion section outlining our contribution and potential avenues for further research.

FTAs and the European Parliament

In the past 15 years, a growing number of ‘new-generation’ FTAs have been negotiated by the EU.Footnote 1 Laursen and Roederer-Rynning (Reference Laursen and Roederer-Rynning2017) point to two fundamental differences between trade agreements negotiated by the EU until the early 2000s and the ‘new-generation’ ones. The latter are increasingly ‘deep and comprehensive’ as they ‘cover a broad range of trade liberalisation issues – from goods and services to investment, through intellectual property […] and aim not at just eliminating tariffs, but at more ambitiously, integrating markets’ (p. 764). Second, although previous agreements focused on development issues and used to involve mainly former colonies in the African, Caribbean, and Pacific, new FTAs aim at creating jobs and growth in the EU by targeting global powers. In particular, two of these FTAs attracted the attention of public opinion across Europe: the TTIP with the United States and the CETA with Canada (Dominguez, Reference Dominguez2017; Hübner et al., Reference Hübner, Deman and Balik2017). However, other FTAs, such as the one with Japan, did not spark a similarly intense debate (Suzuki, Reference Suzuki2017). Such variation in salience led scholars to start investigating the ‘politicization’ of EU trade policy (Laursen and Roederer-Rynning, Reference Laursen and Roederer-Rynning2017; Meunier and Czesana, Reference Meunier and Czesana2019).Footnote 2

The involvement of the EP in these increasingly salient agreements is a relatively recent topic. In fact, it was only with the Lisbon Treaty (2009) that the EP made a ‘leap forward’ (Van den Putte et al., Reference Van den Putte, De Ville, Orbie, Stravridis and Irrera2015) and acquired a significant role in the negotiations, both formally and informally. On the formal, according to the rules set in Lisbon, the EP has to give its consent to any trade agreement negotiated (TFEU) and it should be regularly updated on where negotiations are going. With regards to EU trade legislation, the EP is on an equal footing with the Council under the Ordinary Legislative Procedure. Empirically, the most emblematic example of the EP exercising its newly obtained powers was the decision to vote against the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement in 2012 (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014; Van den Putte et al., Reference Van den Putte, De Ville and Orbie2014; Sicurelli, Reference Sicurelli2015). On the informal, a number of scholars have focused on the increasing engagement of the EP in trade negotiations since Lisbon particularly from 2014 onwards. Jančić (Reference Jančić2016) has analysed how the EP and the US Congress are active players in shaping transatlantic relations, as their veto powers over international agreements enable them to expand their informal influence through ‘diplomatic’ action (2016: 908). Ripoll Servent (Reference Ripoll Servent2014) has overviewed the EP's ability to use its day-to-day decision-making to informally expand its veto powers. Finally, Peffenköver and Adriaensen (Reference Peffenköver and Adriaensen2021) have shown the EP's capability of signalling ‘looming vetoes’ to the Commission in order to modify negotiation outputs. This growing strand of research underlines the existence of a process of institutional self-empowerment and ‘assertion’ (Roederer-Rynning, Reference Roederer-Rynning2017) undertaken by the EP in the negotiation and ratification of new EU FTAs, especially in the context of salient ones such as TTIP and CETA (Young and Peterson, Reference Young and Peterson2014; Dominguez, Reference Dominguez2017) but also, for example, in the EU–Korea FTA (Park, Reference Park2017). Ultimately, according to Meissner (Reference Meissner2016) the relevance of the EP has truly reached its apex with the TTIP, as opposed to earlier trade negotiations (2016: 284).

Besides the general empowerment of the EP vis-a-vis other political actors, scholars have also focused on the EP's positioning on specific matters such as human rights conditionality in various agreements including Vietnam (Sicurelli, Reference Sicurelli2015), CETA (Meissner and McKenzie, Reference Meissner and McKenzie2019), and on a wider sample of cases (Meissner and McKenzie, Reference Meissner and McKenzie2019; Saltnes and Thiel, Reference Saltnes and Thiel2021). Moreover, Frennhoff Larsén (Reference Frennhoff Larsén2017) has analysed the EP's preferences in terms of market access and pharmaceutical regulations in the EU–India negotiations. Relating to the determinants of more general support on trade agreements, evidence not yet corroborated by systematic large-n data collection acknowledges the importance of left-right dimensions, as well as of line of conflict over non-commercial issues (Shaohua, Reference Shaohua2015; Van den Putte et al., Reference Van den Putte, De Ville, Orbie, Stravridis and Irrera2015). In contrast, Norrevik (Reference Norrevik2020) accounts for MEPs backing of the TTIP, CETA, and Korea Free Trade Agreement on the basis of government support and a number of political-economic variables. Finally, within the above-mentioned ‘politicization’ of EU trade policy (Laursen and Roederer-Rynning, Reference Laursen and Roederer-Rynning2017; Meunier and Czesana, Reference Meunier and Czesana2019; Bianculli, Reference Bianculli2020; De Bièvre et al., Reference De Bièvre, Garcia-Duran, Eliasson and Costa2020) – materialized in much higher public salience and contestation of trade agreements – recent contributions connect the EP to this subject suggesting that under high political salience MEPs seems to be more responsive to citizens (Rosén, Reference Rosén2019), and keener to use the contestation instruments at their disposal (Meissner and McKenzie, Reference Meissner and McKenzie2019).

Against this backdrop, we argue that the literature tackling the EP in connection to trade policy is very wide but tends to focus much more on its institutional influence in the supranational arena, especially under politicized agreements, rather than on the drivers of single MEPs’ preferences on these agreements. In other words, although the spotlights are set on how the EP attempts to shape trade relations as an active EU player, there is scant research on the party politics side of FTAs, in particular, on what influences MEPs preferences on FTAs. What explains the variation of MEPs support of these agreements? Our aim is to answer this question by providing the first comprehensive analysis of MEPs preferences over new-generation FTAs. We seek to combine classic research on competition within the EP with the emerging literature on FTAs and their politicization. On the one hand, we aim to test the presence of left-right and pro-anti EU dimension cleavages on this issue. On the other hand, we explore how the agreement's politicization affects competition in the EP.

Hypotheses

Several scholarly accounts consistently point to the presence of two fundamental cleavages in the EP: the left-right dimension and support for the EU integration (Kreppel and Tsebelis, Reference Kreppel and Tsebelis1999; Hix, Reference Hix2001; Noury, Reference Noury2002; Hix et al., Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2005; McElroy and Benoit, Reference McElroy and Benoit2007; Otjes and van der Veer, Reference Otjes and van der Veer2016). These two cleavages override nationality in explaining MEPs behaviour, suggesting that political actors are key, rather than nationality.Footnote 3 In their seminal study, Hix et al. (Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2006) argue that the classic left-right dimension of democratic politics is the crucial dimension of politics in the Parliament and that the dimension of pro-anti EU is present but to a lesser extent. More recently, Otjes and van der Veer (Reference Otjes and van der Veer2016) highlight that the Eurozone crisis has increased the relevance of support for EU integration in shaping MEPs preferences, especially concerning economic issues. Involving matters of national interest and sovereignty, foreign policy issues can be expected to raise a conflict based on nationality. However, several studies show that even in this policy area the left-right dimension is prominent shaping individual positions (Hix and Høyland, Reference Hix and Høyland2013; Raunio and Wagner, Reference Raunio and Wagner2020).

In this contribution, we seek to test the impact of these two fundamental ideological cleavages in shaping the preferences of MEPs over FTAs. We first focus on the traditional cleavage between left and right. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the left-right divide has reflected the societal cleavage between capital and labour (Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). Based on the achievement of social equality through welfare states, this cleavage has deep ramifications for party positions on free trade (Hiscox, Reference Hiscox2002). Although socialist left-wing parties are more favourable to protectionism as a form of state intervention in the market, neo-liberal right-wing parties are free trade champions, viewing tariffs as a form of restriction to international flow of goods and capitals. Differences concerning free trade are essential to the point that the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) lists positive and negative mentions of protectionism among the instances discriminating between left-wing and right-wing parties, respectively (McDonald and Budge, Reference McDonald and Budge2005). Several studies confirm the existence of a strong left-right divide on this issue (Milner and Judkins, Reference Milner and Judkins2004; Milner and Tingley, Reference Milner and Tingley2011). For instance, Milner and Judkins (Reference Milner and Judkins2004: 98) demonstrate that ‘right parties consistently take more free trade stances than do left ones’. This division is inevitably reflected in legislative arenas. In fact, Milner and Tingley (Reference Milner and Tingley2011) find that conservative members of the US House of Representatives tend to be more in favour of trade liberalization.

As we just suggested, the left-right dimension is acknowledged to be a dominant dimension of conflict not only in national parliaments but also in the EP (Noury, Reference Noury2002; Hix et al., Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2005, Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2006; McElroy and Benoit, Reference McElroy and Benoit2007). Two studies (Shaohua, Reference Shaohua2015; Van den Putte et al., Reference Van den Putte, De Ville, Orbie, Stravridis and Irrera2015) suggest that this dimension tends to shape the conflict on trade policy in the post-Lisbon scenario as well. Interestingly, Jančić (Reference Jančić2017: 212) argues that, in the case of TTIP, ‘in Britain and France protectionist impulses are more detectable among left-leaning parties’ (p. 212). Therefore, we expect position on the left-right axis to fundamentally structure support for FTAs in the EP.

Hypothesis 1a: Right-wing MEPs are more supportive of FTAs than left-wing MEPs

Second, we concentrate our attention on the pro-anti EU cleavage. As noted earlier, several studies find this dimension to be a relevant line of conflict in the EP (Hix et al., Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2006; McElroy and Benoit, Reference McElroy and Benoit2007; Otjes and Van der Veer, Reference Otjes and van der Veer2016). According to the ‘Hix and Lord model’, the one that has been corroborated the most by empirical evidence support for EU integration is orthogonal to the left-right position: they are independent from each other (Hix and Lord, Reference Hix and Lord1997). Shifting from a situation of ‘permissive consensus’ to a one of ‘constraining dissensus’ with regards to the relationship between public and elites (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), this divide has become increasingly central in shaping European politics over the years, especially, after the EU crisis (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). The progressive transfer of powers from the national to the supranational level in the EU has surely contributed to this development. In fact, it has stimulated the rise of challenger parties of the left and the right that contest globalization and the erosion of national sovereignty (Hobolt and Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016).

The growing importance of the cleavage between Europeanist and Eurosceptic parties is also mirrored in the EP (Otjes and Van den Veer, Reference Otjes and van der Veer2016). Trade policy is presumed to cut across the EP over this line of conflict even more profoundly than other issues. On one side, MEPs from mainstream and liberal parties, supporting further market and trade integration in the EU context, should also be generally in favour of free trade and market integration. Conversely, MEPs from challenger and Eurosceptic parties are expected to oppose increasing international trade liberalization, as it would supposedly threaten national sovereignty and widen the gap between the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of globalization (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi2006). Competition across this dimension should be exacerbated by fact that trade policy is an exclusive EU competence (Art. 3 TFEU). In this regard, Eurosceptic MEPs may be more hostile towards the EU's trade initiatives and the Commission's ability to lead negotiations, merely because of their aversion towards the EU executive, rather than the agreement itself.

With regards to the specific issue of FTAs, Steiner (Reference Steiner2018) demonstrates that a positive view of the EU is a strong explanatory variable to explain public support for the TTIP. As MEPs are elected politicians, we expect this factor to have a similar impact on their preferences.

Hypothesis 1b: Pro-EU MEPs are more supportive of FTAs than anti-EU MEPs

Beyond assessing the impact of these two fundamental cleavages on competition in the EP over FTAs, we also seek to examine how these dimensions interact with the salience of the agreement. As noted earlier, although FTAs share several features including the commitments on liberalization of trade in goods, as well as commitments on services, investments, and regulatory issues (Laursen and Roederer-Rynning, Reference Laursen and Roederer-Rynning2017; European Commission, 2019), they differ insomuch as some became highly politicized throughout their negotiations, and others less so. Notably, the TTIP with the United States was subject of great mobilization in relation to a number of concerns raised by civil society over the environment, food standards, and public services. Similarly, and partly as a consequence of contestation over TTIP, CETA was subject to a similarly severe public scrutiny (Hübner et al., Reference Hübner, Deman and Balik2017). Conversely, important FTAs negotiated with other countries/organizations, such as those with Japan and Mercosur, generally flew below the public radar (Meunier and Czesana, Reference Meunier and Czesana2019).

We argue that the politicization of FTAs may bear relevant consequences for the divisions within the EP. In the context of EU integration, De Wilde defines politicization as an ‘increase in polarization of opinions, interests or values and the extent to which they are advanced towards policy formulation within the EU’ (2011: 566). This phenomenon has magnified in more recent years largely due to the expansion of EU competencies in a number of policy areas (De Wilde and Zürn, Reference De Wilde and Zürn2012). Politicization is, therefore, primarily a bottom-up process occurring at the national level, stimulated by a rise in public awareness and mobilization concerning EU affairs (Schimmelfennig, 2020). Against this background, EU actors may react either by increasing or decreasing their visibility and the salience of the issue itself, according to what they consider being more in line with their mandate by electorate and elites (Bressanelli et al., Reference Bressanelli, Koop and Reh2020). In other words, they ‘look over their shoulders’ (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009) by de-politicizing the issue or, alternatively, ‘ride the wave’ by further politicizing it. Several researchers have shown how both majoritarian (Wratil, Reference Wratil2018; Schneider, Reference Schneider2019) and non-majoritarian institutions adapt policy choices in light of intensifying public debates about European integration (Rauh, Reference Rauh2019; Blauberger and Martinsen, Reference Blauberger and Martinsen2020). As the only directly elected institution in the EU, the EP is arguably very much exposed to the politicization process. MEPs are strongly incentivized to respond to issue salience and visibility by calling for a more transparent and accountable decision-making process and presenting their views as responsive to the demands of the electorate. This should be true especially for all those challenger parties on the left and the right that are ‘unconstrained in politicizing the EU and thrive on winning over dissatisfied voters from mainstream parties when EU policies become contested’ (Schimelfenning, Reference Schimmelfennig2020: 351).

Consequently, in the context of FTAs, we expect MEPs to react to politicization by further increasing their own visibility, taking a more ideological tone during debates. Especially, those MEPs who oppose these agreements are likely to further polarize the discussion and emphasize broader ideological issues with respect to more technical one such as economic gains, portraying themselves as closer to the electorate. As Duina (Reference Duina2019) points out, TTIP and CETA stimulated an ideological and value-based societal debate that was inevitably mirrored within the EP. In light of this discussion, we expect politicization to magnify the impact of the two aforementioned cleavages, left-right and pro-anti EU, in shaping MEPs preferences on FTAs.

Hypothesis 2: Politicized FTAs intensify the ideological conflicts between MEPs both on the left-right and pro-anti EU dimensions.

Measuring support for FTAs in the EP

In order to measure MEPs preferences on FTAs, we collected and analysed 706 MEP speeches occurred all the 20 plenary debates during the 7th and 8th EP terms (2009–2019) regarding six major FTAs: TTIP, CETA, and the agreements with Japan, Mercosur, Australia/New Zealand, and South Korea. The distribution of the debates by agreement is the following: three TTIP, four CETA, five Japan, three Mercosur, two Australia/New Zealand, and three South Korea. During these debates, 332 different MEPs took the floor, representing 117 distinct national parties and 28 countries (all the current Member States plus United Kingdom).Footnote 4 The more salient FTAs, TTIP and CETA, account for more than a half of all the total speeches (254 and 164, respectively) whereas the other agreements have more limited numbers of observations (95 Japan, 92 Mercosur, 51 Australia/New Zealand, and 50 South Korea).

We did not analyse other agreements negotiated in this period due to issues of data availability and comparability. Some FTAs were excluded as they were either not debated at all or debated only to declare voting intentions, such as the ones with Thailand and Malaysia, respectively. Other FTAs, such as those with Singapore and Colombia, were not considered as the related debates did not focus on trade but, rather, on the respect of human rights and rule of law in the trading partners. The shift of attention to other issues clearly compromises a solid and consistent testing of our main hypotheses, which are instead circumscribed to trade. To sum up, the FTAs included in the analysis were the only ones for which it was possible to extract comparable MEPs preferences that suit our theoretical purposes.

Although the majority of studies investigating dimensions of conflict within the EP employ roll-call votes as a source of data (Kreppel and Tsebelis, Reference Kreppel and Tsebelis1999; Hix et al., Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2005, Reference Hix, Noury and Roland2006), we focus on speeches instead, for three main reasons.Footnote 5 First, in some cases, it is not possible to identify a single vote correctly representing MEPs' support for the FTA under scrutiny. In fact, in the EP, different resolutions containing distinct positions on the same topic are often put under vote. Given this, votes reflect MEPs' positions about what the resolution says about the topic under discussion and not about the topic itself. For example, one debate in our dataset (CETA – 15 February 2017) was followed by three roll call (final) votes on resolutions articulating diverging opinions on the same FTA. Unsurprisingly, the resolutions had different results: two were approved, one was not. Second, speeches have fewer constraints than votes and provide more nuanced information concerning MEPs positions (Proksch and Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2010). In fact, although MEPs face strong incentives to toe the group and/or national party line in a roll-call vote, they have more leeway to express their opinion in their statements. Dissenting legislators may even use the opportunity to talk in public to signal their diverging point of view. In any case, MEPs articulate position that are much more complex than ‘yes’, ‘no’ or, ‘abstain’ when they talk. In other words, speeches allow us to capture all the different blurs in terms of positions across the Parliament (Goet, Reference Goet2019). Finally, as existing studies exploring conflicts within the EP on external policy and/or trade policy use roll-call votes (Van den Putte et al., Reference Van den Putte, De Ville, Orbie, Stravridis and Irrera2015; Raunio and Wagner, Reference Raunio and Wagner2020), by using MEPs' speeches, we are able to test the validity of their arguments on a different source of data.

The main drawback of employing MEPs speeches consists of the fact that only a limited number of MEPs take the floor. In our dataset, the most participated debate (TTIP – 7 July 2015) involved 114 single speakers, a little more than 15% of all the MEPs. In the least participated (Japan – 17 April 2014) only three MEPs spoke. We attempt to minimize selection bias by analysing multiple debates regarding the same agreement. Furthermore, it is important to note that most issues concerning FTAs are previously discussed within the relative EP committees. In theory, this should reduce the extent of conflict in the floor. However, we believe that MEPs still have strong incentives to articulate different positions during plenary debates. This is foremost due to the higher level of publicity of the latter compared to committee meetings.

Given the focus on the speeches, we measure the degree of support/opposition to the agreement under negotiation through a manual textual analysis. Our choice of using hand-coding over supervised and unsupervised scaling techniques such as Wordscores (Laver et al., Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003) and Wordfish (Slapin and Proksch, Reference Slapin and Proksch2008) is mainly motivated by the necessity to grasp fine-grained differences in MEPs’ positions, and, simultaneously, develop a measure of support that could be easily compared across the agreements. Producing valid and comparable measures would be more difficult as the scarcity of existing literature on conflicts in the EP on FTAs makes it hard to identify reliable reference texts for Wordscores. In addition, the limited length of the text documents and the high complexity of the debates may negatively affect the validity of measures produced by Wordfish (Hjorth et al., Reference Hjorth, Klemmensen, Hobolt, Hansen and Kurrild-Klitgaard2015).

A preliminary open coding (Kuckartz, Reference Kuckartz2014) reveals the occurrence of several topics including consumer and environmental protection, democratic accountability, protectionism, and trade liberalization. Moreover, several qualitative differences emerge between the more politicized agreements, that is, CETA and the TTIP, in comparison with the others. On the one hand, in the case of CETA and TTIP there is a stronger and marked tendency to defend EU standards and fight for higher market regulation. For example, in one debate (7/7/2015) Marine Le Pen, the well-known leader of the French far right and Eurosceptic party Rassemblement National (formerly known as ‘Front National’) defined TTIP as a ‘bombshell’ as it would have put ‘quality agriculture in danger of disappearing’ since ‘Americans do not have the same protective vision of standards that Europeans have’. On the other, in the case of Japan, it is this latter to be criticized for being too protectionist, especially in the automobile sector. David Martin, MEP for the British Labour Party, and member of the International Trade (INTA) committee, said in another debate about this agreement (17/4/2014) that negotiations would move ahead ‘if Japan is serious about tackling nontariff barriers’. In summary, the non-politicized agreements display, on average, less aggressiveness and strong opposition to un-regulated openness.

Although this topic exploration may be highly useful in the context of in-depth case study research evaluating the kind of arguments presented by different MEPs, for the scope of this paper our main goal is to produce a general and comparable measure of support/opposition within the negotiations. Hence, after the preliminary topic exploration just overviewed, we sought to narrow-down the coding to a binary category, that is, statements supporting the agreement under debate, and statements opposing it. In line with the methodology of the CMP (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Bara and Budge2009), we employ ‘quasi-sentences’: each quasi-sentence contains one statement or ‘message’, in this case support or opposition to the agreement under debate. Through this simpler categorization, we obtain a parsimonious measurement of FTA support. To construct our dependent variable, that is, support for FTAs, we measure each MEP's support for the trade agreement based on a statement's share of positive quasi-sentences in relation to negative quasi-sentences (Schimmelfennig and Winzen, Reference Schimmelfennig and Winzen2020), by computing the difference between all statements in favour and all statements against the agreement within each statement.Footnote 6 After that, to make the value comparable across statements, we weight the difference by the length of the text, as longer statements are more likely to contain higher lexical diversity (Koizumi, Reference Koizumi2012) and provide more opportunities to raise a higher number of topics (Xie et al., Reference Xie, Yang and Xing2015) – and hence express a higher number of favourable or unfavourable positions.Footnote 7

The dataset

The dataset includes the measure of support for FTAs obtained through the hand-coding of speeches as a dependent variable, together with a series of independent and control variables. Our dependent variable, Support FTA, ranges between about −8 and 15 and has a mean close to 0. The distribution does not appear skewed, and the vast majority of values falls between −5 and 5.Footnote 8 Predictably, on average, the mean is negative for the two most salient agreements, TTIP and CETA, indicating a rather generalized EP's hostility. However, the scores are also slightly below zero also in the cases of South Korea and Mercosur. This suggests a considerable level of contestation on this issue, also on less salient FTAs.

The key independent variables are MEP's position on the left-right axis, their support for EU integration and FTA's politicization. Position on the left-right axis and support for EU Integration are taken from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey 2014 (Polk et al., Reference Polk2017). This survey was chosen because it was conducted in the middle of our timespan. MEPs are attributed to the scores on the basis of their national party affiliation. Left-right position and EU support correspond to the variables LRGEN and POSITION, respectively. LRGEN ranges from 0 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right), whereas POSITION from 1 (strongly opposed) to 7 (strongly in favour). In order to compare the effect of the two variables, we rescaled support for the EU in a measure ranging between 0 and 10. Although we are aware of the relevance of the GAL/TAN cleavage in shaping competition in contemporary politics in Europe (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018), we did not include this ideological variable in our analysis for two reasons. First, at least in Western Europe, it is strongly associated with the left-right axis: left-wing parties and right-wing parties are located at the GAL and TAN sides, respectively (Marks et al., Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006). It is, therefore, unsurprising to find a strong correlation (r = 0.7412) between these two measures in our dataset. Second, there is some evidence that the left-right axis is a stronger predictor of European parties' positions on foreign policy issues than the GAL/TAN dimension. In fact, Wagner et al. (Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2018) find that support for military interventions is better explained by a party location on the left-right axis. The large number of parties in the dataset avoids encountering significant gaps in the distribution, even at the extremes.

To distinguish politicized and non-politicized agreements, we created a dichotomous variable, taking value 1 for TTIP and CETA and 0 for agreements with Japan, Mercosur, Australia/New Zealand, and South Korea. This is a proxy based on the existing literature on FTAs (Dominguez, Reference Dominguez2017; Hübner et al., Reference Hübner, Deman and Balik2017; Suzuki, Reference Suzuki2017; Duina, Reference Duina2019). We are aware that a continuous variable would better capture the nuances of the societal debate over these FTAs. However, we faced significant limitations in terms of data availability concerning non-politicized agreements. For example, we examined searches on Google of terms associated with the analysed FTAs, but data were either scant or completely non-existent, depending on the agreement.

The dataset also includes five control variables: two for MEPs' nationality and three for their individual role in the debate and appointments in the EP. Starting from the ‘nationality variables’, we separate MEPs elected in northern countries from those that are elected in other countries through a dichotomous measure. Scholars have highlighted a persistent cleavage in EU trade policy between a liberal North and a protectionist South (Young and Peterson, Reference Young and Peterson2014). We consider as northern countries Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Sweden, and United Kingdom. They account for 40.9% of our sample. Moreover, we distinguish Eastern MEPs from their Western colleagues. Elsig (Reference Elsig2010) has highlighted that more recent member states supported this EU trade policy shift towards new-generation FTAs, also for political reasons. Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia are considered as Eastern countries. Almost a quarter of the speakers in our dataset is elected in these states. Furthermore, the dataset contains MEP-level dummy variables, controlling for their membership in the International Trade (INTA) committee, their presence in the EU partner's delegation, and their role as group speaker in the debates.Footnote 9 As Proksch and Slapin (Reference Proksch and Slapin2014) note, speaking time in the EP is allocated by groups is also based on MEPs individual competences, demonstrated by their membership in key committees and delegations. Indeed, 42.4% of all the MEPs in our dataset were members of the INTA committee at the time of the debates.

With respect to the full sample of speeches, 53 observations were removed from the analysis. Forty observations (13 TTIP, 10 CETA, 4 Japan, 7 Mercosur, 4 Australia/New Zealand, and 2 South Korea) consisted of speeches given by independent MEPs, that is, those that are not affiliated to any national party. The reason is that we could not rely on any source to attribute to these MEPs a score for the variables left-right position and support for the EU. We removed further 13 observations from ‘non-informative’ speeches (five TTIP, three CETA, one Japan, three Mercosur, and one South Korea), not containing at least one match for any of the coding categories. In other words, in those statements, MEPs talked about issues not associated with the FTAs. Eventually, the dataset contains 653 observations (236 TTIP, 151 CETA, 90 Japan, 82 Mercosur, 47 Australia/New Zealand, and 47 South Korea).Footnote 10 Table 1 summarizes the variables in our dataset and their descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the variables

Analysis and results

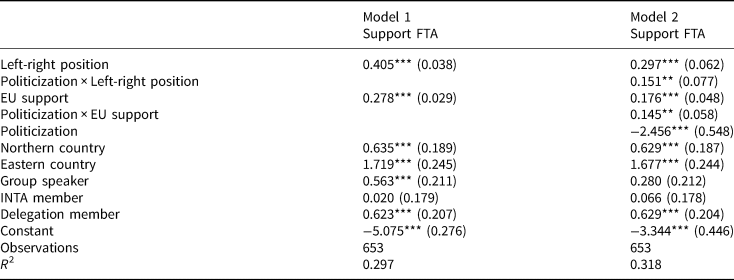

We test our hypotheses by means of two linear regression models with robust standard errors. Model 1 tests the individual impact of left-right position and support for the EU on MEPs preferences on FTAs (H1a and H1b). Model 2, in turn, assesses how the agreements' politicization affect these two conflicts in EP debates (H2). Table 2 reports the results of the two models.Footnote 11

Table 2. OLS regression models with robust standard error

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1.

Model 1 indicates that competition across the left-right and pro-anti EU dimensions fundamentally shapes MEPs support for FTAs. In fact, left-right position has a positive and highly significant effect on our dependent variable. Therefore, in line with H1a, right-wing MEPs are, on average, more supportive of FTAs than their left-wing counterparts. Moreover, support for EU integration is positively and significantly associated with the dependent variable. This means that, confirming H1b, the more MEPs have a positive view of the EU and its institutions, the more they support FTAs negotiated by the EU institutions themselves. The coefficient for left-right position is larger than the one for EU support: although a one-unit increase on the former dimension leads to a 0.405 increase in our measure of support, a one-unit increase in the latter dimension has a 0.278 impact. This indicates that the left-right dimension is generally more decisive in structuring competition in the EP over FTAs. The results contained in model 2 suggest that politicization magnifies these two ideological conflicts in the EP. In fact, both interaction terms with left-right axis and support for the EU are positive and significant. This suggest that, as expected in H2, in our two politicized agreements, TTIP and CETA, differences between left-right and pro-anti EU MEPs were more marked than in the other four non-politicized agreements, that is, those with Japan, Mercosur, Australia/New Zealand, and South Korea. In other words, politicization seems to lead to more polarization in preferences on this issue in the EP.

In both models, the control variables concerning conflicts based on MEPs nationality have a positive and highly significant correlation with support for FTAs. As expected, MEPs elected in Northern and Eastern countries are more in favour of these agreements. In particular, the East-West divide seems extremely relevant in structuring preferences over FTAs. In addition, members of the specific EU partner's delegation are predictably more supportive than their colleagues. On the contrary, sitting on the INTA committee does not appear to make a significant difference. Finally, the term for Group speaker is positive and significant only in model 1, not indicating a robust correlation with support for FTAs.

Figure 1 describes the adjusted prediction of support for politicized and non-politicized FTAs distributed across the left-right axis and EU support dimensions. First, the plots show that these two cleavages matter in determining whether an MEP is in favour of these agreements or not. On the one hand, right-wing MEPs are generally supportive of FTAs whereas left-wing MEPs are, on average, against. On the other hand, the more an MEP has a positive view of the EU, the more he/she supports these agreements. Second, they confirm that the left-right cleavage contributes more to polarization within the EP over this issue than the pro-anti EU dimension. In fact, both lines in the graph on the left are steeper than the respective ones in the graph on the right, making the distance between the most positive and most negative positions larger. This depends on the fact that although at the extreme left sides of the two scale positions are similar, at the extreme right side of the left-right scale we find more positive position than in the pro-anti EU scale. Therefore, although left-right and Eurosceptic MEPs are almost equally against FTAs, right-wing MEPs are more in favour of the agreements than strongly Europeanist ones. Third, the plots highlight how politicized agreements exacerbate competition in the EP across both these ideological dimensions. This could be seen in the two plots as the two lines diverge the more you approach the respective left poles, increasing the distance between positions. Interestingly, CETA and TTIP attracted significantly more criticism from left-wing MEPs. As we already suggested, the effect is slightly stronger in the pro-anti EU dimension. Indeed, in the plot on the right, the two lines diverge slightly more to the point that only strongly pro-EU MEPs seem to support these agreements.

Figure 1. Adjusted prediction of the effect of left-right position (left) and support for the EU (right) in politicized and non-politicized FTAs [95% confidence interval (CI)].

Figure 2 plots the conditional effect of a one-unit increase in left-right and EU support variables on support for FTAs, in both politicized and non-politicized agreements. For both ideological independent variables, the effect is always positive, disregarding of the presence of politicization. However, as we already underlined, it increases in the two politicized agreements, TTIP and CETA. The effect moves from around 0.30 to 0.45 for the left-right and from 0.18 to 0.32 for the pro-/anti EU cleavage. This means a 50 and 77% increase, respectively. Therefore, politicization apparently amplifies more the conflict across the pro-anti EU dimension than that across the left-right axis.

Figure 2. Average marginal effect of a one-unit increase of left-right position (left) and support for the EU (right) in politicized and non-politicised FTAs (95% CI).

Conclusions

In this paper, we investigated the drivers of MEPs preferences on EU's new-generation FTAs. In particular, we examined the impact of the two most fundamental cleavages in the EP, left-right and pro-/anti EU, and how politicization, in turn, affects these lines of competition. To do so, we first hand-coded all the debates occurred in the 7th and 8th parliamentary terms (2009–2019) on six major FTAs, TTIP, CETA, and the agreements with Japan, Mercosur, Australia/New Zealand, and South Korea, to construct an original and comparable measure of within-speech agreement support. This measure was then employed as a dependent variable in regression models to test our arguments.

We find that competition over FTAs is structured along the two fundamental cleavages in the EP, left-right position, and support for the EU. On the one hand, right-wing MEPs are significantly more in favour of FTAs than their left-wing colleagues. Therefore, for instance, an MEP from the European People's Party (EPP) group is, on average, more in favour of FTAs than a colleague from the Socialist and Democrats (S&D) group that is, in turn, less critical than the one from the extreme-left group (GUE/NGL). This result is in line with various studies finding a relationship between the left-right dimension and free trade preferences: the right more supportive of trade liberalization and the left more protectionist (Milner and Judkins, Reference Milner and Judkins2004; Milner and Tingley, Reference Milner and Tingley2011). The collection of a considerable amount of data regarding multiple FTAs strongly corroborates previous findings about the relevance of the left-right cleavage in explaining preferences over EU trade policy in the EP (Shaohua, Reference Shaohua2015; Van den Putte et al., Reference Van den Putte, De Ville, Orbie, Stravridis and Irrera2015). On the other hand, the more an MEP has a positive view of the EU, the more he/she supports FTAs. For example, generally pro-EU EPP and S&D MEPs tend to be more in favour than their colleagues from the Eurosceptic group formerly known as Europe of Nations and Freedom.Footnote 12 This is totally plausible since FTAs are designed to further integrate global markets and the Commission, the supranational EU executive, is in charge for initiating and conducting negotiations. Furthermore, this finding confirms the growing importance of the pro-anti EU dimension in shaping contemporary European politics at both the levels of public opinion and, consequently, political parties (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018).

We also show how politicization amplifies the ideological conflicts within the EP. The left-right and pro-anti EU cleavages on FTAs became deeper in the case of politicized agreements than in non-politicized agreements: TTIP and CETA attracted significantly more contestation from left-wing and Eurosceptic MEPs than the other agreements considered in the analysis. In particular, conflict over position on EU integration, the dimension that is arguably more connected with items such as values and identities between the two, has gained more prominence in these two cases. These findings resonate well with recent studies on EU trade policy emphasizing how TTIP and CETA triggered a public and political debate that went far beyond rational benefits and drawbacks of the agreements themselves, touching upon values and beliefs cutting across current European politics (Steiner, Reference Steiner2018; Duina, Reference Duina2019). Research on politicization in the EU has underlined how significant domestic mobilization on salient issues puts policy-makers in front of a choice: decreasing issue-visibility and, by the same token, its salience, or emphasize it further (Bressanelli et al., Reference Bressanelli, Koop and Reh2020). In the case of FTAs, MEPs seem to have chosen the latter strategy. This is understandable considering how their mandate depends on the capacity to represent their own constituencies. Therefore, politicization of trade policy moves not only the EP as a unitary institution in search of self-empowerment, but also its members, one by one. Although this study does not deal directly with responsiveness, these findings may be of use for further research (see e.g. Rosén, Reference Rosén2019) investigating in more depth the connections between EP debates and different demands coming from citizens and interest groups vis-à-vis their party and group affiliation.

In summary, this paper constitutes the first comprehensive examination of MEPs' preferences on new-generation FTAs. So far, existing studies have either relied on limited empirical evidence (Shaohua, Reference Shaohua2015; Van den Putte et al., Reference Van den Putte, De Ville, Orbie, Stravridis and Irrera2015) or subsumed this issue in the larger universe of EU's external relations (Raunio and Wagner, Reference Raunio and Wagner2020). Given the relevance of EU trade policy and how it involves both EU and national interests, we consider it as a strong contribution to the literature on the factors shaping preferences in the EP. Furthermore, in contrast to the vast majority of studies on this topic, our study employs speeches rather than roll-call votes to measure MEPs' position. Although we acknowledge and address the limitation of this source of data, we believe that speeches offer a valuable and yet underestimated resource to explore competition in the EP. On the one hand, the exploration of topics through manual coding allows us to grasp several issues important to intervening MEPs which could be employed for more in-depth qualitative research in the future. On the other, a more parsimonious grouping of these topics allows us to construct a preference ratio comparable across different agreements.

Finally, our findings may offer relevant insight for research focusing on the interaction between politicization and EU institutions. In our case, politicized FTAs present stronger ideological conflict in the EP. From a supranational/EU perspective, observing a Parliament leaning towards a more marked resemblance with national ones under politicization, might be a positive signal in favour of more genuine transnationalism. On the other hand, high politicization may pave the way for a more ‘sectarian’ and polarized EP.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2021.50

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Fabio Franchino, Manuela Moschella e Christian Freudlsperger for their suggestions on earlier versions of the article. They are also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for the comments and insights.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.