Romeo and Juliet is not only one of the most popular of Shakespeare’s plays, it is one of the most popular stories in the world. It is probably the most widely disseminated myth of romantic love; the very names of its heroes have become synonyms for young lovers. The image of a young woman on a balcony, conversing with her lover by moonlight, is a universally recognised icon. Romeo and Juliet are endlessly invoked in pop culture, in advertisements, TV shows, cartoons, and popular songs. The play has been filmed dozens of times and is probably second only to Hamlet as the most frequently performed of Shakespeare’s works.

Yet while Romeo and Juliet has rarely been off the stage since Shakespeare’s time, it has rarely – if ever – been there as Shakespeare wrote it. Wide discrepancies between the two quarto texts suggest a degree of instability in the play even in Shakespeare’s day, and since the theatres reopened after the Restoration the play has undergone radical transformations. It has always been popular, but it has also always been edited, adapted, and rewritten. In spite, or perhaps because, of its enduring appeal as the definitive love story, Romeo and Juliet has been a dynamic and unstable performance text, endlessly reinvented to suit differing cultural needs.

Restoration adapters radically altered the text, adding a happy ending in James Howard’s version, and a Roman political context in Thomas Otway’s Caius Marius. A century later David Garrick, following Otway and others, added a passionate scene between Romeo and Juliet in the tomb. Garrick tailored the play to showcase his own histrionic powers, making it primarily a vehicle for Romeo: he and Spranger Barry had a celebrated rivalry in the role. By the nineteenth century, however, Romeo had become a role that actors avoided, and the play primarily a vehicle for actresses. Juliet became the signature part of Eliza O’Neill, Fanny Kemble, and Helena Faucit, and developed into an idealisation of Victorian womanhood. Even Romeo became a star part for actresses, especially Charlotte Cushman, who finally rejected the Garrick text in favour of Shakespeare’s. This restoration coincided with the Victorian penchant for authenticity, which, together with technological and theatrical developments, shifted the play’s focus from the lovers to their environment. Henry Irving’s production used scrupulously detailed Veronese settings, expertly choreographed crowd scenes, and spectacular scenic effects to create an imaginative representation of Renaissance Italy in which he and Ellen Terry were awkwardly out of place.

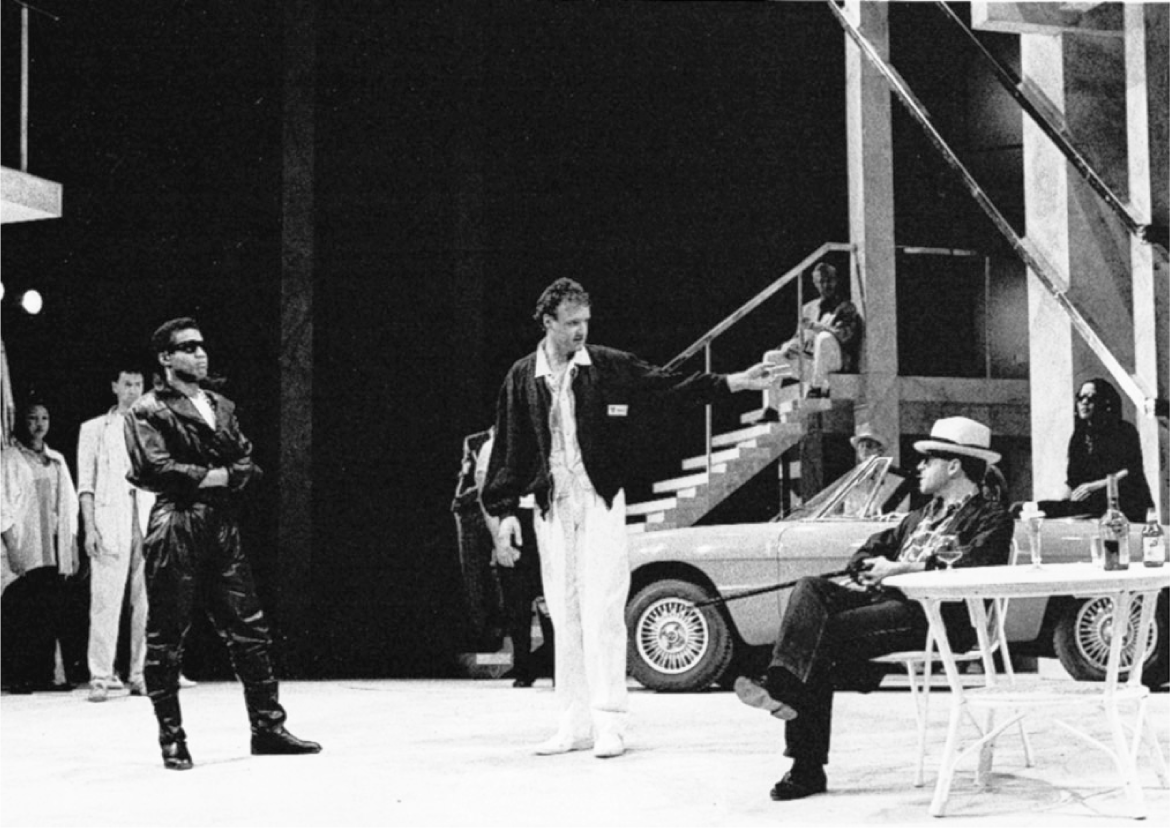

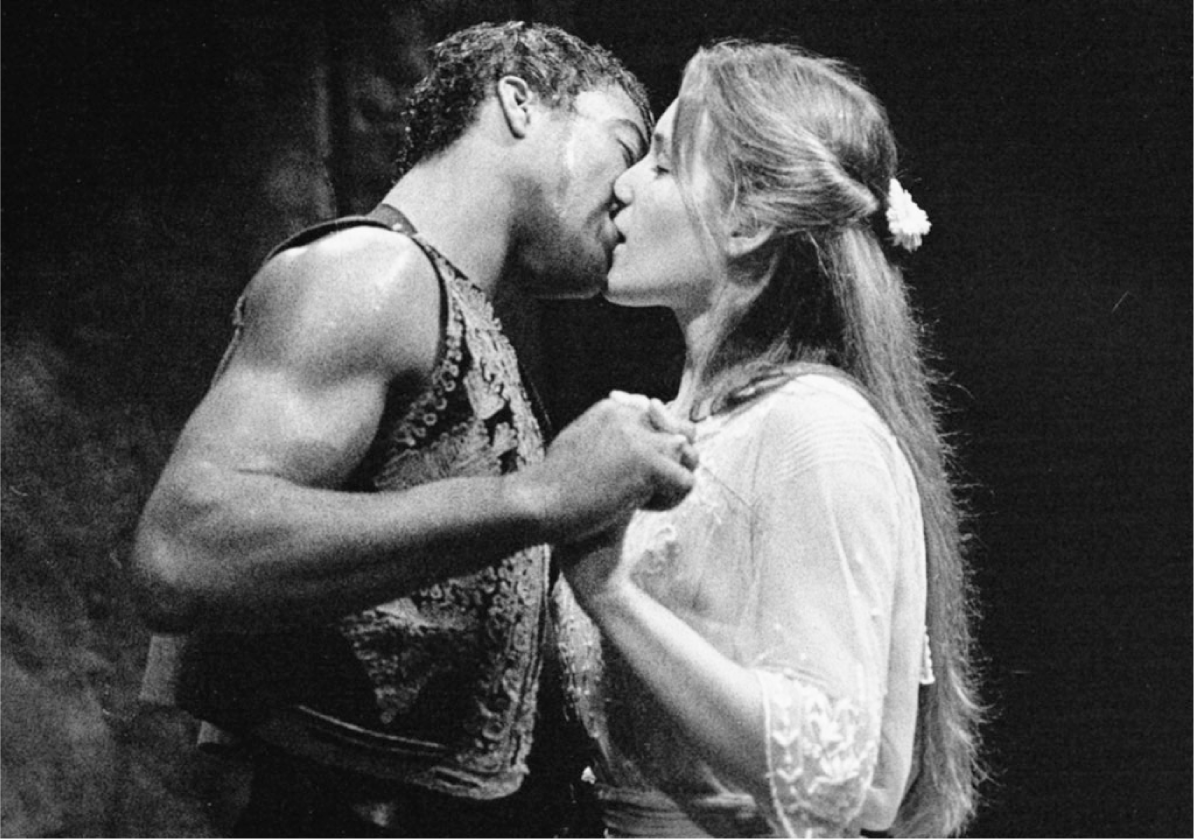

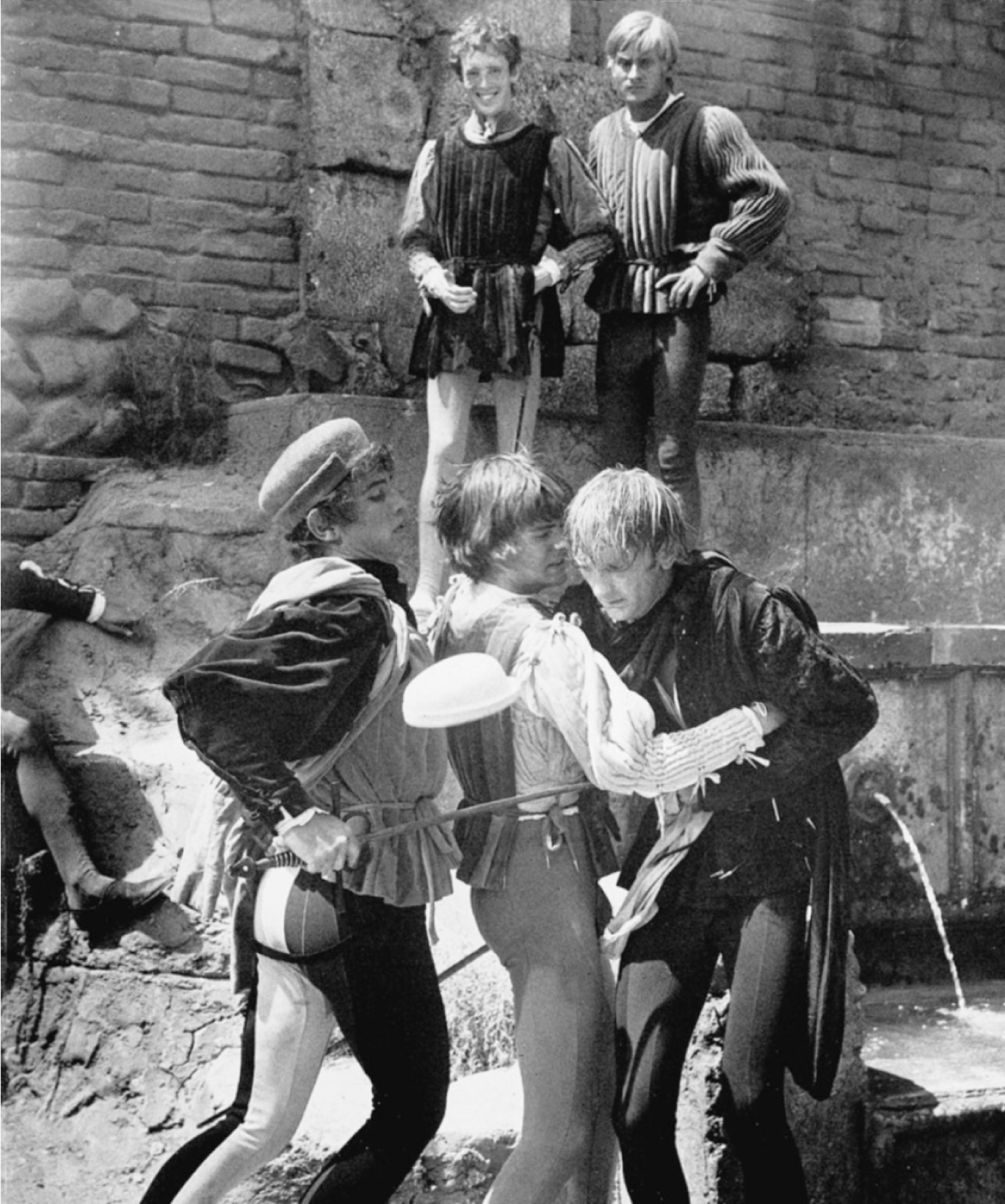

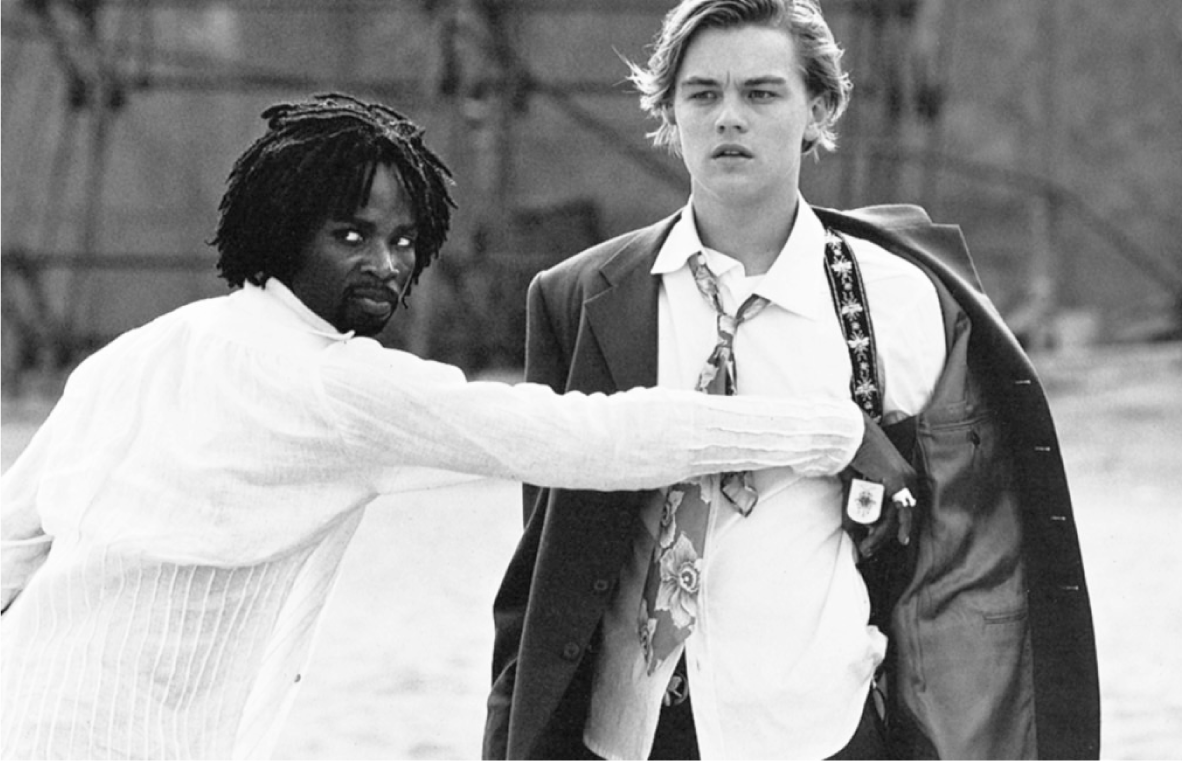

The twentieth century has seen further shifts in the play’s meaning. The influence of William Poel and Harley Granville-Barker led to fuller texts and leaner stagings, notably John Gielgud’s celebrated production of 1935, in which he and Olivier alternated Romeo and Mercutio. The contrast between them marked a crucial change in modern acting styles, with Gielgud’s poetic elegance giving way to Olivier’s intense realism. This transition, continued by Peter Brook at Stratford, was fully realised with Zeffirelli’s boisterous, earthily Italian production at the Old Vic in 1960, a seminal moment in the play’s history. Zeffirelli made the play a celebration of youthful rebellion, in keeping with the cultural trends of the sixties and the rise of the teenager. The focus on recognisably modern youth in Zeffirelli’s play and film, as well as in the stage and film versions of Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story, redefined Romeo and Juliet as a study of generational and cultural conflict. In the twentieth century Romeo and Juliet turned from a play about love into a play about hate. Modern-dress versions became increasingly common, as did settings in various contemporary blood-feuds such as Northern Ireland or Bosnia. Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film version sums up the contemporary approach with its urban nightmare world of gang violence, conspicuous consumption, and frenzied, lurid imagery.

While different aspects of Romeo and Juliet – its lyricism and bawdry, its comedy and tragedy, its politics and sentiment – have emerged at different times, it has remained a vivid index of cultural attitudes about romantic love and social crisis. This edition aims to trace the broad trends whereby performance has reinvented the play, as well as to detail the remarkable variety of individual choices actors and directors have made to bring life and death to Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovers.

Romeo and Juliet on Shakespeare’s Stage

About the first performances of Romeo and Juliet we know little that is concrete. We do not know when, where, or how often the play was performed, or who played the leading roles, although there has been much speculation on these subjects. The title page of the 1597 first quarto (Q1) records that ‘it hath been often (with great applause) played publicly, by the right honorable the Lord of Hunsdon his servants’. This company was Shakespeare’s, better known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. The play must have been performed before 1597, but there is no conclusive evidence that it was written later than 1592; probably it dates from between 1594 and 1596.Footnote 1 At any rate, the Q1 title page suggests that it was a success, and it is among the plays Francis Meres cited in 1598 as examples of Shakespeare’s mastery of tragedy.

Shakespeare almost certainly wrote Romeo and Juliet for the Theatre, the first home of the Chamberlain’s Men and the first purpose-built theatre in London since Roman times. The Chamberlain’s Men probably performed the play at the Curtain, their temporary home during the closure of the Theatre, in 1598, and at the Globe after their move there in 1599.Footnote 2 It is also likely that Romeo and Juliet was performed on tour; the company performed in Ipswich, Cambridge, Dover, Rye, Bath, and Bristol, among other towns, between 1594 and 1597.Footnote 3 The first quarto version of the play can be performed with doubling by a company of twelve, plus supers, such as might have been available for a provincial tour.Footnote 4

The two quarto texts of Romeo and Juliet have occasioned much discussion as to their relation and provenance. The second quarto (Q2), published in 1599 and long regarded as the superior version, is the basis for all standard texts of the play. However, Q1, once dismissed as a ‘bad quarto’, has gained much esteem in recent years. Scholars have moved away from the idea of an authorially sanctioned ‘authentic’ Shakespearean text toward a notion of the text as merely one unstable element in the complex creation of Elizabethan theatre. Even if Q1 is a pirated version, reconstructed from memory (the traditional interpretation), it reflects something of Elizabethan playhouse practice. David Farley-Hills has argued that it is a shortened version adapted for provincial performance; Jay Halio concurs, and suggests the adapter was Shakespeare himself. Donald Foster has also argued, using a computer analysis of the text, that Q1 is Shakespeare’s work, though Foster asserts that it precedes Q2.Footnote 5 Whatever its history, Q1 provides suggestive material for performance historians, including unusually precise stage directions. Before their wedding at the Friar’s cell, ‘Enter Juliet, somewhat fast, and she embraces Romeo’ (Q1, ).Footnote 6 While Romeo is lamenting his banishment, ‘Romeo offers to stab himself, and the Nurse snatches the dagger away’ (). After Juliet drinks the potion, ‘She falls upon her bed within the curtains’ (). When Juliet is discovered, apparently dead, ‘They all but the Nurse go forth, casting rosemary on Juliet and shutting the curtains’ ().

As Andrew Gurr has pointed out, Romeo and Juliet makes considerable demands on the resources of the Elizabethan theatre.Footnote 7 It has a very large cast (especially in Q2), numerous properties, and very specific scenic requirements, notably an upper playing area, a curtained bed, and some representation of a tomb. A performance at the Theatre or Curtain would have made full use of Elizabethan staging conventions. Played in broad daylight, night scenes would have been identified by the torches carried by the actors, as before the Capulet ball (1.4). The unlocalised stage, a bare platform in front of the tiring-house façade, would have allowed fluid changes of scene, as when Romeo and his friends move from the street to the party without leaving the stage: ‘they march about the stage, and servingmen come forth with napkins’ (Q2, 1.4.114 SD). Sometimes the location could change even within a scene. In 3.5 Romeo and Juliet enter ‘aloft’ (Q2) or ‘at the window’(Q1) of Juliet’s bedroom, clearly at an upper level above the stage; then ‘he goes down’ to the main-stage platform (presumably using the rope ladder), where he converses with Juliet as from the Capulet orchard. After his exit Lady Capulet enters the platform, and Juliet ‘goes down from the window’ (Q1); when she reenters the platform, it is now presumed to be her bedroom. Such free changes of scene have frustrated many modern directors, but were easily managed on the Elizabethan stage.

The complex demands of the last few scenes must have required similar staging. Juliet’s bed, which appears in 4.3 and 4.5, was either brought out from the tiring house, in which case it must have had its own curtains, or it was located in the discovery space in the tiring-house façade, and so curtained off; the former seems more likely, given sight-line constraints. If the bed was brought onto the stage, it clearly remained during the intervening scene in the Capulet household (4.4), and it may well have become the bier for 5.3.Footnote 8 The staging of the tomb scene raises multiple possibilities. Either the tomb was the discovery space; or the body of Juliet was brought up out of the trap; or she had remained onstage in her bed, which became a bier; or some form of tomb-structure was brought on.Footnote 9 Each of these solutions has its adherents, and indeed each has been made to work, one way or another, in subsequent performances.

About the casting we know almost nothing. A bit of an elegy associating Richard Burbage with the role of Romeo is now generally discounted as inauthentic, though as the leading actor of Shakespeare’s company he is the likeliest candidate.Footnote 10 In The Organization and Personnel of the Shakespearean Company, T. W. Baldwin argued that Richard Burbage played Romeo, Thomas Pope Mercutio, Robert Goffe Juliet, George Bryane Friar Lawrence, John Heminges Capulet, Augustine Phillips Benvolio, William Sly Tybalt, Will Kemp Peter, and Shakespeare the Prince.Footnote 11 Donald Foster, using computer analysis, has argued that Shakespeare played Friar Lawrence.Footnote 12 Only the assignment of Peter to Kemp has any direct evidence to support it. The Q2 text has the stage direction ‘Enter Will Kemp’ for Peter’s scene with the musicians at 4.5.99. Beyond that, all we really know is that Romeo and Juliet was performed by a professional theatre company, of which Shakespeare was a member; that the women’s roles were played by male actors; and that the play availed itself of such scenic resources as the Elizabethan playhouse afforded.

As to what Elizabethan audiences made of the play, there again we can only speculate. Stories of young lovers confronting parental opposition were familiar enough, though mainly limited to comedy; Shakespeare had used similar situations, and the same setting, for The Two Gentlemen of Verona. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, written either just before or just after Romeo and Juliet, he burlesqued the star-crossed lovers’ story, both through the adventures of Lysander and Hermia and with the Mechanicals’ version of Pyramus and Thisbe. In any event, Romeo and Juliet used a familiar narrative and dealt with issues of interest to the Elizabethans, notably marriage, family conflict, and civil disturbance. It did not, however, present a strict mirror of Elizabethan family life. Juliet’s marriage at age thirteen, for instance, was not at all typical. Elizabethan women of the propertied classes usually married at twenty, the middle and lower classes even later.Footnote 13 Upper-class families certainly made arranged marriages, though the children’s wishes were usually consulted. The notion of a love-match based purely on personal affection was something of a novel one, and Shakespeare’s play may well have encouraged it. As Lawrence Stone observes, there was ‘a clear conflict of values between the idealisation of love by some poets, playwrights and the authors of romances on the one hand, and its rejection as a form of imprudent folly and even madness by all theologians, moralists, authors of manuals of conduct, and parents and adults in general’.Footnote 14 Shakespeare’s sympathy for the lovers was not the only possible response; the preface to his source, Arthur Brooke’s Romeus and Juliet, describes ‘a couple of unfortunate lovers, thralling themselves to unhonest desire, neglecting the authority and advice of parents and friends … abusing the honorable name of lawful marriage to cloak the shame of stolen contracts, finally, by all means of unhonest life, hasting to most unhappy death’.Footnote 15 While Brooke’s narrative itself isn’t so harsh, such antipathy toward the lovers’ ‘unhonest’ behaviour was certainly an available attitude.

At any rate, the conflict between love-matches and marriages arranged for family interest would have been a recognisable one to Elizabethans, particularly as many of the audience were likely to have been in their late teens and early twenties.Footnote 16 Another highly topical issue was duelling. Despite Tudor edicts against them, street fighting and violent feuds were a constant danger, and duelling was on the rise in the 1590s.Footnote 17 The late sixteenth century saw an invasion of Italian and Spanish fencing masters, with their stylish terminology and elaborate rules of etiquette.Footnote 18 Shakespeare’s Mercutio, though ostensibly Italian himself, repeatedly mocks ‘such antic, lisping, affecting phantasimes’ (2.4.25) in his characterisation of Tybalt as ‘the courageous captain of compliments … the very butcher of a silk button, a duellist, a duellist’ (18–19, 21–2). Indeed, the play’s presentation of duelling is a part of its curious admixture of things English and things Italian. Elizabethans certainly associated the Italians with violence and passion: Roger Ascham wrote in 1570 of ‘private contention in many families, [and] open factions in every city’.Footnote 19 Yet English playwrights regularly used Italy as a mirror, and audiences would not have needed to look too hard to see themselves in Shakespeare’s play. The domestic details of the Capulet household, with its servants Potpan, Sue Grindstone, and Nell, and its joint-stools, trenchers, log fires, and baked meats, suggest middle-class Elizabethan life rather than the aristocracy of the Italian Renaissance.

Elizabethan audiences certainly seem to have liked and remembered the play. It was reprinted three times before the 1623 Folio, and The Shakspere Allusion-Book cites thirty-six references to it before 1649, more than to any play except Hamlet. Several plays of the period echo or parody elements of Romeo and Juliet. Porter’s The Two Angry Women of Abingdon and Dekker’s Blurt, Master Constable both include burlesqued balcony scenes, as well as deliberate verbal echoes.Footnote 20 John Ford’s ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore (1631) invokes Shakespeare’s tragedy in depicting a star-crossed love affair between a brother and sister, admonished by a Friar and aided by a Nurse. Robert Burton, discussing the dangerous effects of love in The Anatomy of Melancholy, cites Shakespeare’s lovers, as though they had already, in 1624, become universally recognised emblems of tragic passion:

Romeo and Juliet in the Restoration Theatre

Romeo and Juliet returned to the stage, in some form, soon after the Restoration. Samuel Pepys records in his diary that he saw the premiere on 1 March 1662, given by William Davenant’s company, the Duke’s Men. Pepys was not impressed: ‘It is the play of itself the worst that ever I heard in my life, and the worst acted that ever I saw these people do’, largely because the actors didn’t know their lines.Footnote 22 Mary Saunderson played Juliet, probably the first woman to take the role. Her future husband Thomas Betterton, the leading actor of the period, did not partner her, but played Mercutio, while Henry Harris was Romeo, according to the prompter John Downes.Footnote 23 Downes relates that the play was next revived in altered form: ‘This tragedy of Romeo and Juliet, was made sometime thereafter into a tragicomedy by Mr James Howard, he preserving Romeo and Juliet alive; so that when the tragedy was revived again, ’twas played alternately, tragical one day, and tragicomical another, for several days together.’Footnote 24 No other account of this version exists, but the story isn’t implausible: Howard was a writer of comedies, and Nahum Tate was soon to add a happy ending to King Lear. While Romeo and Juliet has seldom been played with the lovers surviving, several adaptations and non-English versions have had happy endings. In David Edgar’s stage version of Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby, Vincent Crummles’s troupe perform a hilarious Romeo and Juliet wherein the lovers come back to life singing a patriotic British anthem.Footnote 25 Sadly, I can find no evidence that any Victorian companies actually ended the play this way, though something similar does happen in Andrew Halliday’s popular 1859 burlesque, Romeo and Juliet Travestie: or, The Cup of Cold Poison, wherein Queen Mab appears to reanimate the corpses.Footnote 26

After Howard’s version, the next important incarnation of Romeo and Juliet was in Thomas Otway’s Caius Marius, 1679. Otway grafted much of Shakespeare’s language and characterisation onto a story from Plutarch’s Rome, renaming Romeo Young Marius, and turning Juliet into Lavinia, the daughter of a rival senator. Otway acknowledges, in a disarming prologue, that he has stolen from Shakespeare out of his own necessity, rather than trying to improve the material as other Restoration adapters had done:

In Otway’s play the elder Marius is a demagogue who falls foul of the ruling party in Rome. Though he has himself proposed that his son marry Lavinia, daughter of his rival Metellus, he forbids the match when he learns that Young Marius loves her. Metellus meanwhile wishes Lavinia to marry Sylla, Marius’ chief opponent. Otway gives Young Marius and Lavinia a fairly full version of Shakespeare’s balcony scene – ‘O Marius, Marius, wherefore art thou Marius?’ – as well as much of the dawn parting. As in the French and Italian versions of the story, the lovers share a brief scene in the tomb, when Lavinia awakes from her trance before Young Marius dies:

Lavinia

Marius

After Young Marius dies, Lavinia has to watch Old Marius kill her own father before she stabs herself. Her suicide is an act of fury rather than pathos, as she rages at her former father-in-law:

The political conflict remains unresolved; civil war once again threatens to engulf Rome. The play ends with the death of Sulpitius, Old Marius’ henchman, who is based loosely on Mercutio but turned into a character of almost unmitigated brutality and cynicism:

Sulpitius

Granius

Sulpitius No, ’tis not so deep as a well, nor so wide as a church-door. But ’tis enough; ’twill serve; I am peppered I warrant, I warrant for this world. A pox on all madmen hereafter, if I get a monument, let this be my epitaph:

Later critics have been very hard on Otway’s adaptation, with some justification. Frederick Kilbourne, in 1906, refused ‘to waste any time or words upon such a contemptible piece of thieving’, while in 1927 Hazelton Spencer found it an ‘abominable mixture of Roman and Renaissance’, of which ‘the execution … is as grotesque as its conception’.Footnote 28 Yet Otway’s work deserves reappraisal, especially in the light of twentieth-century attempts to reinterpret Romeo and Juliet. For while Otway’s setting the play in Rome may seem incongruous, he is in fact doing what many modern productions have done, in trying to give the play a contemporary political relevance. As Kerstin P. Warner has pointed out, Otway’s play is not really concerned with ancient Rome but with the politics of Restoration England.Footnote 29 Old Marius is a version of Lord Shaftesbury, a powerful Whig politician Otway saw as a dangerous demagogue. The scenes of civil conflict throughout are directly related to the Exclusion crisis; Otway feared that Whig attempts to keep the Catholic Duke of York from succession would lead to civil war. By using the story of Romeo and Juliet to protest, not the feuding of rival families, but a contemporary political crisis, Otway was anticipating many directors and adapters of much more recent times.

Two other features of Otway’s version are notable, from the point of view of staging. Otway acknowledged in the Epilogue that some of his audience came ‘Only for love of Underhill and Nurse Nokes’ (18). These were two of the star performances, in the roles of Sulpitius (Mercutio) and the Nurse – then as now characters in danger of stealing the play from the leads. The Nurse was played by a man, James Nokes, in the Elizabethan tradition. This practice continued until at least 1727. Mrs Talbot was apparently the first female Nurse, at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in 1735.Footnote 30 Otway and the actor Cave Underhill made Sulpitius a caustic and brutal swordsman. In the 1774 Bell edition, Francis Gentleman, comparing Otway’s ‘snarling cynic’ with the ‘vacant, swaggering blade’ typical of eighteenth-century Mercutios, declared that ‘Otway’s conception of him is more consistent with nature and with Shakespeare.’Footnote 31 Otway’s cynical Sulpitius was perhaps not so far from the violent gang-leader Mercutio often became in the twentieth century. Betterton played Old Marius; the lovers were William Smith and Elizabeth Barry, the leading tragic actress of the Restoration.

The play fared well with Restoration audiences, and proved Otway’s third most popular: it was performed most seasons for the next fifty years.Footnote 32 Its success presumably inspired the staging of more Shakespearean versions in the 1740s, by Theophilus Cibber at the Haymarket, Thomas Sheridan in Smock Alley, Dublin, and finally David Garrick. Perhaps Otway’s most important influence was the inclusion of a scene between the lovers in the tomb, which became standard practice for nearly 165 years.Footnote 33

Theophilus Cibber’s version, performed in 1744, restores a good deal of Shakespeare’s text, though it also incorporates large sections of Otway and bits of The Two Gentlemen of Verona. There is no ball scene, as Romeo is in love with Juliet from the beginning. As in Otway, Romeo’s father has previously considered a match between the two,

Almost all of Shakespeare’s scenes appear in some form, generally abbreviated; the Mantua scene, 5.1, is reset ‘near the walls of Verona’ in accordance with the neoclassical unity of place. The tomb scene between the lovers is taken from Otway almost without alteration, though Juliet is given a more pathetic death speech:

Cibber, the dissolute and much-hated son of Colley Cibber, played Romeo himself, opposite his daughter Jane (Jenny), who was Juliet’s age of fourteen at the time. Much of the Prologue to the play is devoted to begging indulgence for young Jenny, ‘Who, full of modest terror, dreads t’appear, / But, trembling, begs a father’s fate to share’ (p. 74). By Cibber’s own account, the play ran successfully for twelve nights at the Haymarket: ‘Jenny nightly improved in the part of Juliet. Our audiences were frequently numerous, and of the politest sort’ (p. 74). Other contemporary accounts are harsher. John Hill pitied Jenny Cibber for having to play opposite ‘a person whom we could not but remember, at every sentence she delivered concerning him, to be too old for her choice, too little handsome to be in love with, and, into the bargain, her father’.Footnote 35 Such quasi-incestuous pairings were not uncommon among the theatrical dynasties of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but the Cibbers came under particular attack. David Garrick was revolted: ‘I never heard so vile and scandalous a performance in my life … the girl, I believe, may have genius; but unless she changes her preceptor, she must be entirely ruined.’Footnote 36 Romeo and Juliet did seem to catch the public’s fancy, and would have played longer had not the owners of the two patent theatres invoked the Licensing Act to shut down the Haymarket performances.

The next revival of the play was by Garrick’s sometime associate Thomas Sheridan in Dublin, opening 15 December 1746. Sheridan’s performances, at the Smock Alley Theatre, were notable for their reattribution of the Queen Mab speech. According to Gentleman, Sheridan, who played Romeo, ‘by an amazing stroke of injudicious monopoly annexed this whimsical picture to his own sighing, lovesick part’.Footnote 37 Sheridan gave the speech ‘with all the melancholy solemnity of a sermon’, according to Thomas Wilkes.Footnote 38 Juliet was George Anne Bellamy, a young Irish actress who would later partner Garrick. The play, ‘written by Shakespeare with alterations’, was grandly mounted; Sheridan added an elaborate funeral scene and raised his prices to cover ‘a great deal of expense in decorations’.Footnote 39 The production managed a successful run of nine nights.

David Garrick and the ‘Battle of the Romeos’

The most significant of the eighteenth-century adaptations was certainly that of David Garrick. First published and performed in 1748, Garrick’s version was close to Shakespeare by eighteenth-century standards. As he explained in his preface, ‘the alterations to the following play are few and trifling, except in the last act; the design was to clear the original, as much as possible, from the jingle and quibble which were always thought the great objections to reviving it’.Footnote 40 By jingle, Garrick meant rhymed verse, which he avoided by judicious substitutions. Speaking of Juliet’s eyes, Garrick’s Romeo observes, ‘They’d through the airy region stream so bright / That birds would sing and think it were the morn’ (rather than ‘not night’, as in 2.2.21–2). The sonnet shared by the lovers at the Capulet ball (1.5.92–105) is reduced to a seven-line exchange containing only one rhyme. By quibble, Garrick meant the punning and bawdry that offended eighteenth-century sensibilities. Garrick’s Mercutio loses the quip about dying ‘a grave man’, for instance, and the sexual innuendo is increasingly curtailed in successive editions of the play. Garrick makes other concessions to decorum: Juliet’s age is increased to eighteen, and in the ‘Gallop apace’ speech she loses her most explicit reflections on ‘amorous rites’ and ‘stainless maidenhoods’ (3.2.8–16). Nevertheless, in his first version of the play in 1748, Garrick included Romeo’s love for Rosaline, in the face of public opinion: ‘Many people have imagined that the sudden change of Romeo’s love from Rosaline to Juliet was a blemish in his character, but an alteration of that kind was thought too bold to be attempted; Shakespeare has dwelt particularly upon it, and so great a judge of human nature knew that to be young and inconstant was extremely natural.’Footnote 41 By 1750, however, Garrick accepted his friend Dr Johnson’s dictum that ‘the drama’s laws the drama’s patrons give’, and wrote Rosaline out of the play, protesting only that he did so ‘with as little injury to the original as possible’.Footnote 42 Gentleman approved, commenting: ‘Making no mention of Rosaline, but rendering Romeo’s love more uniform, is certainly improving on the original, notwithstanding the caprices of love.’Footnote 43

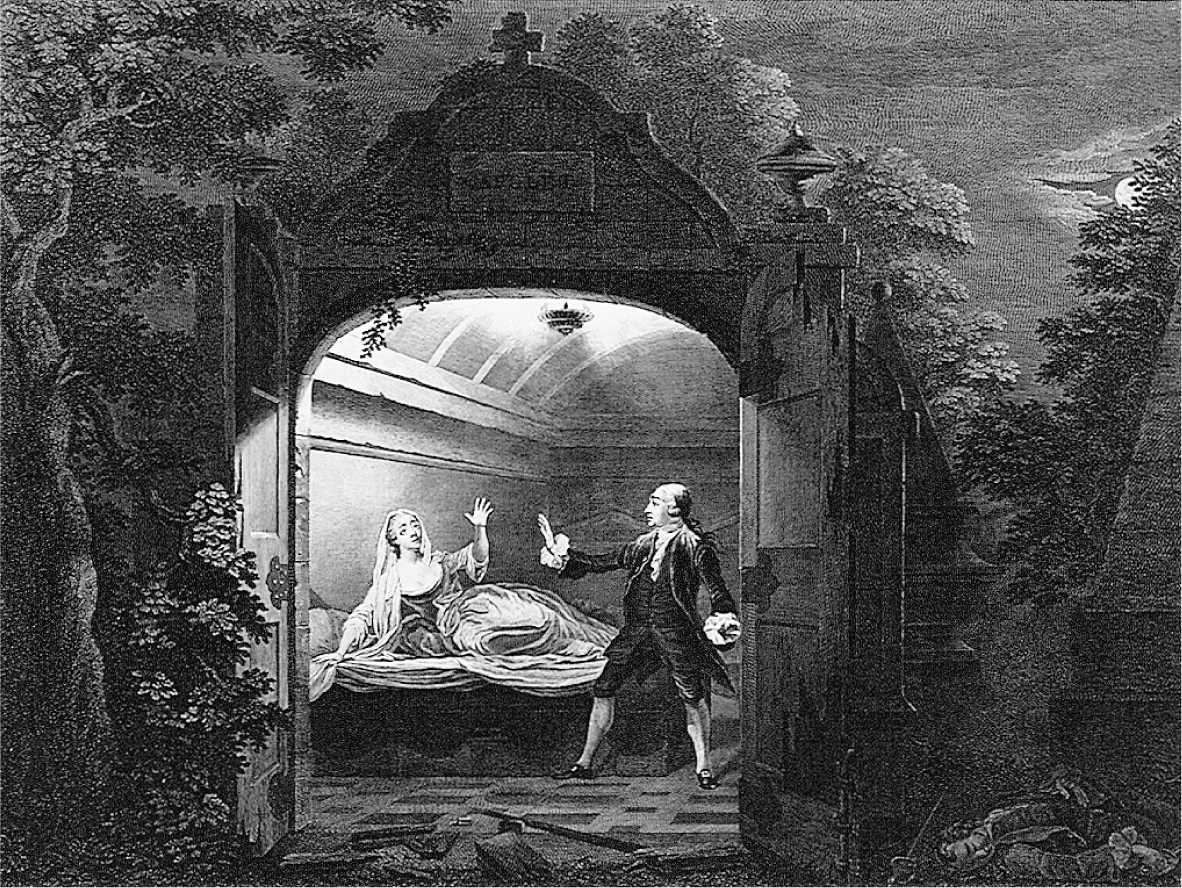

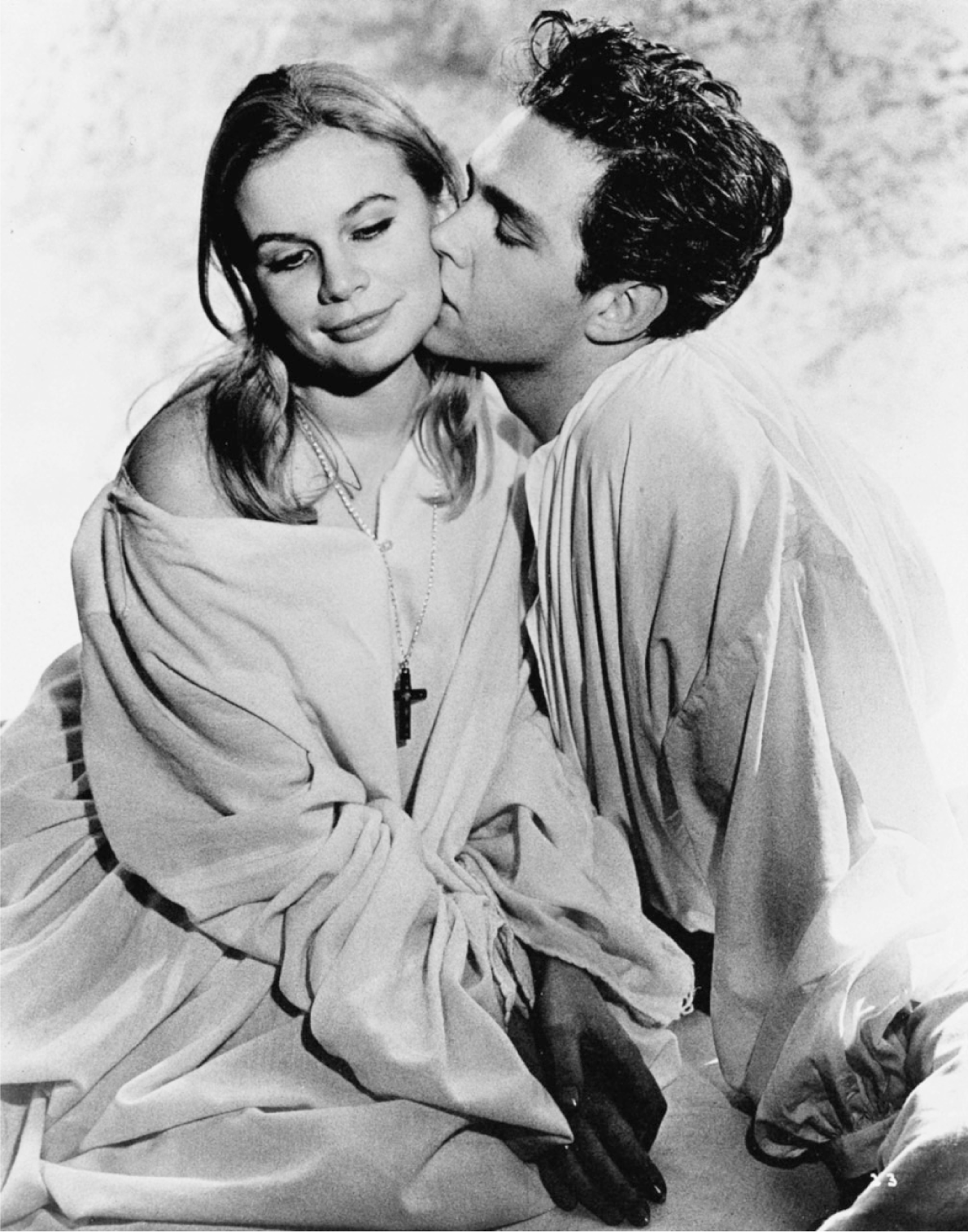

1 George Anne Bellamy and David Garrick in Garrick’s added tomb scene, wherein Juliet wakes after Romeo has taken the poison but before he dies, c. 1750.

In the last act, Garrick added a new scene between the lovers in the tomb, even longer and more complex than the Otway–Cibber version (see Appendix, pp. 252–4). In a preface to his published text, Garrick cited literary precedent to justify his alteration: ‘Bandello, the Italian novelist, from whom Shakespeare has borrow’d the subject of this play, has made Juliet to wake in the tomb before Romeo dies: this circumstance Shakespeare has omitted not perhaps from judgement, but from reading the story in the French or English translation, both which have injudiciously left out this addition to the catastrophe.’Footnote 44 While it is unlikely that Shakespeare couldn’t have thought of a tomb duet by himself, Garrick is perfectly correct in his account of the various versions. Garrick’s own judicious ‘addition to the catastrophe’ afforded scope for the virtuoso display of alternating passions that was the hallmark of eighteenth-century acting. In 1746 Aaron Hill had codified the ten dramatic passions in an actor’s arsenal as ‘joy, grief, fear, anger, pity, scorn, hatred, jealousy, wonder, and love’.Footnote 45 Garrick’s tomb scene allows for all of these, most in the seventy-line exchange with Juliet, as his happiness at her awakening gives way to the poison’s effect, and he dies cursing his fate:

Garrick’s ending, however, adds another dimension to the scene beyond the actor’s self-display. Garrick’s text brings the social causes of the tragedy into the tomb. ‘Fathers have flinty hearts, no tears can melt ‘em’, Romeo cries. ‘Nature pleads in vain – children must be wretched.’ Shakespeare’s lovers give little thought to the feud in their final moments, whereas Garrick’s are bitterly aware of the reason for their fate, and die exclaiming against it. Accordingly, when the families enter the tomb at the end, the Prince’s condemnation of them is even harsher and more explicit than in Shakespeare:

Garrick’s ending certainly proved popular with contemporary critics. Francis Gentleman, in 1770, wrote, ‘As to the catastrophe, it is so much improved, that to it we impute a great part of the success which has attended this tragedy of late years.’Footnote 46 In 1808 Thomas Davis asserted that the scene ‘was written with a spirit not unworthy of Shakespeare himself’.Footnote 47 Charles Wyndham used Garrick’s text as late as 1875, and Fanny Kemble allegedly preferred Garrick: Clifford Harrison quotes her as saying, in 1879, ‘I have played both; my father has played both; and I know which is best for the stage.’Footnote 48 Few would now make this claim; but in the twentieth century it again became common to have Juliet wake before Romeo’s death. Julie Harris, in Michael Langham’s 1960 Stratford, Ontario production, awoke in time to watch Romeo die, a moment described by one reviewer as ‘electric in its impact’.Footnote 49 Trevor Nunn and Barry Kyle, at Stratford in 1976, made Juliet’s awakening a central emblem of the production, and in Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film the lovers share a few moments of desperate anguish and even exchange some lines. The early awakening of Juliet can add not only pathos, but a defamiliarising shock that reminds the audience of the larger social circumstances responsible for the lovers’ deaths.

Romeo and Juliet opened, under Garrick’s direction, at Drury Lane on 29 November 1748. Well performed by Spranger Barry and Susanna Cibber (Theophilus’ estranged second wife), the play ran successfully for eighteen performances. Two years later, however, Barry and Cibber decamped to the rival Covent Garden management of John Rich, who announced they would play Romeo and Juliet there. Garrick, anticipating the challenge, secretly prepared for the part of Romeo opposite George Anne Bellamy, who had acted Juliet at Covent Garden earlier in the year. The two productions opened simultaneously on 28 September 1750, beginning what was known as ‘the Battle of the Romeos’. For twelve nights the productions ran head to head, until Cibber withdrew from fatigue or illness. Garrick played for one more night to mark his triumph, but audiences had grown tired of having a single play monopolise both patent theatres, as a verse in the Daily Advertiser attested:

There are a number of contemporary accounts of the relative merits of the two productions, all centring on the character of Romeo. According to William Cooke, ‘Parties were much divided about which of the Romeos had the superiority; but the critics seemed to be unanimous in favour of Barry. His fine person, and silver tones, spoke the very voice of love.’Footnote 51 Some felt Barry was better in the love scenes of the first three acts, Garrick better in the tragic ending, and Cooke reports that ‘some of them supported this opinion by frequently leaving Covent Garden in the middle of the play, to see it finish at Drury Lane’. While Garrick exhibited more tragic passion, he could not compete with the tall, good-looking Barry as a stage lover. Francis Gentleman gave a divided verdict based on careful study of both performances:

As to figure, though there is no necessity for a lover being tall, yet we apprehend Mr Barry had a peculiar advantage in this point; his amorous harmony of features, melting eyes, and unequalled plaintiveness of voice, seemed to promise every thing we could wish, and yet the superior grace of Mr Garrick’s attitudes, the vivacity of his countenance, and the fire of his expression, showed there were many essential beauties in which his great competitor might be excelled.Footnote 52

Gentleman felt Barry was more successful in the balcony and parting scenes, Garrick with the Friar and Apothecary; he divided the play’s end, awarding ‘Mr Barry first part of the tomb scene, and Mr Garrick from where the poison operates to the end’. In conclusion he felt that ‘Mr Garrick commanded most applause, Mr Barry most tears.’

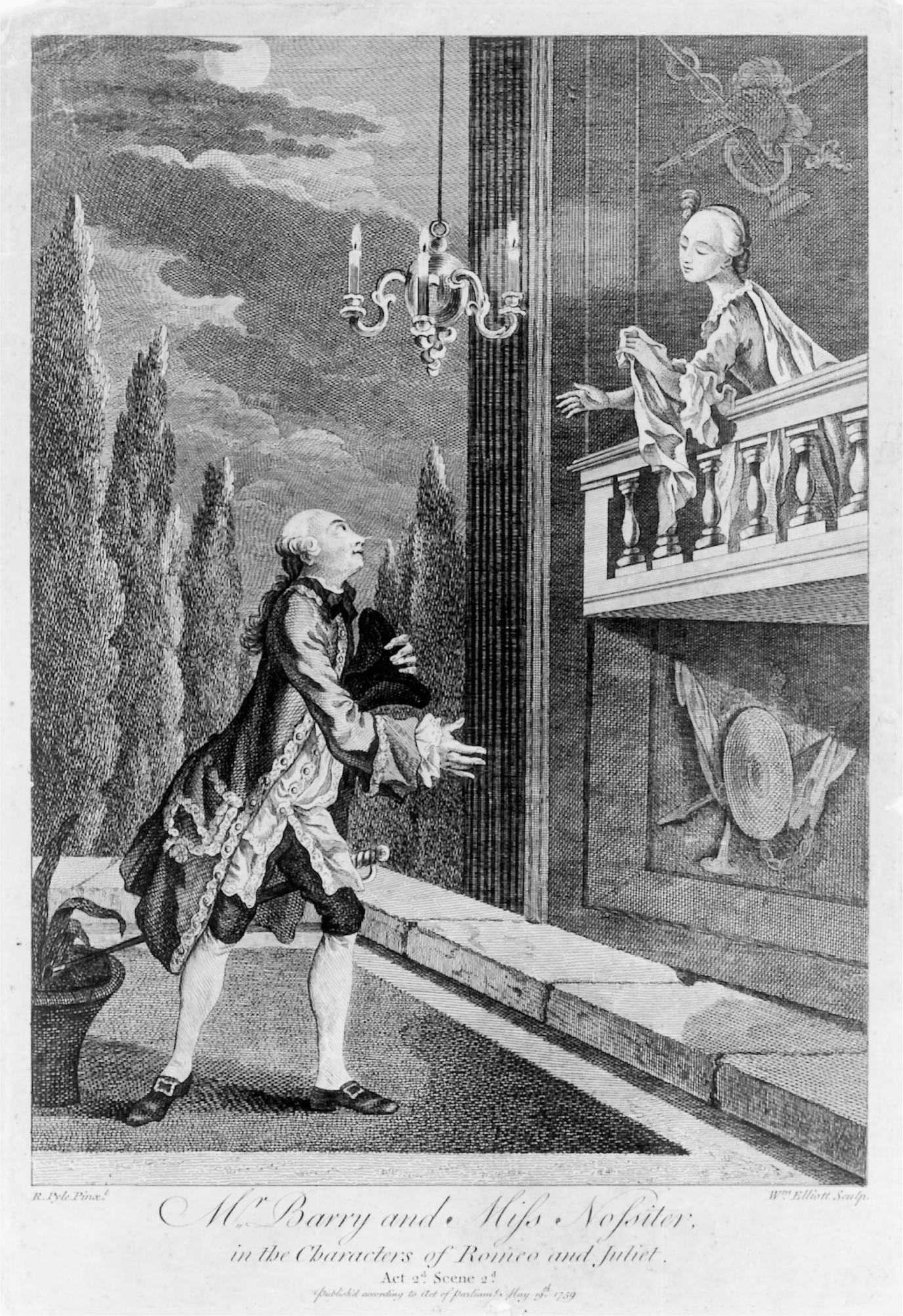

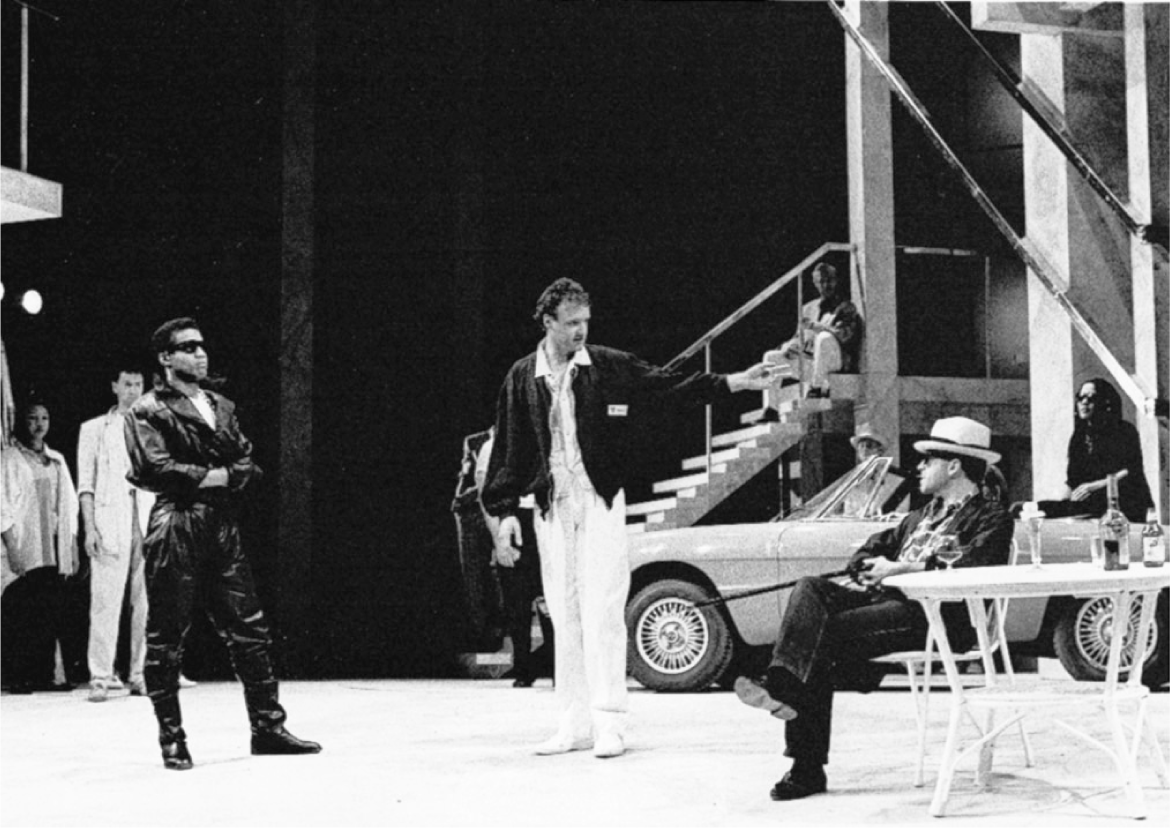

2 Spranger Barry and Isabella Nossiter in the balcony scene, c. 1753. Hannah Pritchard commented, ‘… had I been Juliet to Barry’s Romeo, – so tender and seductive was he, I should certainly have jumped down to him!’

John Hill likewise felt that their different gifts illuminated different aspects of Romeo, but that finally Barry was more suited to it:

in parts where violence and fury are the great characteristics, Mr Garrick succeeds best, and Mr Barry in those distinguished by tenderness; and in the character of Romeo, where there is a great deal of both, they are both … amazingly eminent: if upon the whole, we see Mr Barry with the greatest pleasure, it is not because Mr Garrick is the inferior actor, but because Romeo is more distinguished by love than rage.Footnote 53

One of the most succinct and oft-quoted comparisons is attributed to the actress Hannah Pritchard: ‘Had I been Juliet to Garrick’s Romeo, – so impassioned was he, I should have expected that he would have come up to me in the balcony; but had I been Juliet to Barry’s Romeo, – so tender and seductive was he, I should certainly have jumped down to him!’Footnote 54 Katherine Wright observes that by his triumph as Romeo, Barry redefined the character as a romantic lover rather than a tragic hero, leaving a mark on the play that would not be challenged until the twentieth century.Footnote 55

As to their respective Juliets, Susanna Cibber, who had originally been directed by Garrick, was generally felt to be the more successful, particularly in the tragic passages. Thirty-six at the time of the rivalry, she possessed great beauty, skill, and stage presence, and excelled in tenderness and pathos. As John Hill wrote, ‘What is the reason that nobody ever played Juliet so well as Mrs Cibber, but that Mrs Cibber has a heart better formed for tenderness than any other woman who ever attempted it…?’Footnote 56 Bellamy, at nineteen, was a younger, more passionate Juliet, lacking Cibber’s stature and depth of feeling. The actresses’ offstage identities may have coloured the reception of their performances, as has often happened with this play. Susanna Cibber was the long-suffering wife of the hated Theophilus, and constantly plagued by ill-health, while Bellamy was a bold, vivacious beauty with many lovers and a reckless taste for gambling. The critic of the Gentleman’s Magazine seems to reflect this perception in his assessment: ‘Miss Bellamy, if she possesses not Mrs Cibber’s softness, she makes a larger compensation by her variety … For my own part, I shed more tears in seeing Mrs Cibber, but I am more delighted in seeing Miss Bellamy.’Footnote 57 The partnerships were later reversed; Cibber returned to Drury Lane in 1753 and played Juliet opposite Garrick, though her health frequently kept her off the stage. Barry’s new Juliet, the eighteen-year-old Maria Isabella Nossiter, made a sensational début in the role, but was replaced in 1757 by Bellamy. Nossiter remains the best documented of eighteenth-century Juliets, as an admirer (probably the critic MacNamara Morgan) wrote a detailed pamphlet praising her; he called Nossiter’s potion scene ‘the greatest acting that has been exhibited on the stage, by man or woman, since Betterton went off’.Footnote 58

The rival Mercutios were also noteworthy. By far the more successful was Henry Woodward, who played with Garrick at Drury Lane. A master of high comedy, Woodward made Mercutio a graceful, whimsical fop. The high point of his performance was the Mab speech, treated as an extravagant flight of fancy; John Hill felt ‘… it is not more certain that none but Shakespeare could have wrote this speech, than that no man but Woodward can speak it’.Footnote 59 By contrast, Covent Garden’s Mercutio was Charles Macklin, famous for turning Shylock from a low comic part to one of bitter tragedy. Macklin made Mercutio a coarse and cynical malcontent, along the lines of Otway’s Sulpitius. Gentleman felt Macklin’s ‘saturnine cast of countenance, sententious utterance, hollow toned voice, and heaviness of deportment, ill suited the whimsical Mercutio’.Footnote 60 Yet he conceded that Macklin showed ‘ten times more art’ than Woodward. The predominance of Woodward’s approach is evident in a comment by Macklin’s friend and biographer William Cooke: ‘How Macklin could have been endured in a character so totally unfitted to his powers of mind and body, is a question not easily resolved at this day; particularly as Woodward played this character at the other house, and played it in a style of excellence never perhaps before, or since, equalled.’Footnote 61 Macklin’s darker interpretation of the character would have to wait for the twentieth century to become predominant.

As far as the staging goes, the Covent Garden and Drury Lane performances followed the conventions of the mid-eighteenth century. The theatres were proscenium houses seating well over a thousand, though the actors shared the same light with the audience and could address them directly from the forestage. While actors used conventional gestures to indicate the different passions, Garrick had led a revolution of ‘real feeling’ on the stage, and both Cibber and Bellamy were known for crying real tears.Footnote 62 The scenery was primarily two-dimensional, with wings and shutters pulled from the theatre’s stock of streets, palaces, churches, and groves. Costumes were modern dress: long coats, knee-breeches, elegant gowns, and powdered wigs, even a tricorne hat for Barry’s gallant Romeo.Footnote 63 Both the Drury Lane and Covent Garden productions added elaborate music and spectacle. In addition to a grandly staged masquerade dance at the Capulet ball, both productions included Juliet’s funeral procession, accompanied by a solemn dirge. The dirges were significant musical events, written by two of the leading composers of the day; Drury Lane’s was by William Boyce, Covent Garden’s by Thomas Arne, the brother of Susanna Cibber. Of this innovation Gentleman comments sardonically: ‘Though not absolutely essential, nothing could be better devised than a funeral procession, to render this play thoroughly popular; as it is certain that three-fourths of every audience are more capable of enjoying sound and show, than solid sense and poetical imagination.’Footnote 64 The funeral dirge remained an important part of productions through the nineteenth century, and was often more prominent on playbills than the names of the actors.

Romeo and Juliet was performed 399 times between 1750 and 1800, more than any other Shakespeare play.Footnote 65 Garrick went on playing Romeo until 1761, when he switched to Mercutio; Barry played it continually until 1768, when he was nearly fifty. The play appeared in virtually every season, often at both theatres, through to 1800.

Nineteenth-Century Failures

By the end of the century the London theatre was dominated by the Kemble family, particularly John Philip Kemble and his sister, Sarah Siddons. Both excelled in lofty tragic roles, and were rather too statuesque for Romeo and Juliet. John Philip Kemble’s marmoreal patrician demeanour was more suited to Coriolanus than to Romeo, whom he played for only three performances, without success. Even his loyal biographer James Boaden conceded that ‘youthful love … was never well expressed by Kemble: the thoughtful strength of his features was at variance with juvenile passion’.Footnote 66 Kemble did carefully reedit the play, retaining most of Garrick’s alterations, in what became the standard theatrical version for much of the century. Sarah Siddons played Juliet in the provinces in her youth, but only took the role once in London, opposite her brother on 11 May 1789. She was then thirty-four years old, and ‘time and study had stamped her countenance … too strongly for Juliet’; besides, her cold and formal style was ill suited to the role.Footnote 67 Boaden felt her Juliet ‘was exactly what might have been anticipated – too dignified and thoughtful to assume the childish ardours of a first affection; but, as the serious interest grew upon the character, impassioned, terrific, and sublime’. Nevertheless, ‘she left fewer of her marks upon it, than she did upon any other character of equal force’, and she never attempted it again.Footnote 68

It was Charles Kemble, another brother, who had the best luck with the play. He had considerable success as Romeo opposite Eliza O’Neill, but truly distinguished himself when he switched to the role of Mercutio in 1829, in which part ‘he walked, spoke, looked, fought, and died like a gentleman’, according to one viewer.Footnote 69 He avoided the bullying cynicism of Macklin as well as the foppishness of Woodward, making Mercutio instead an elegant and courtly figure of high comedy. His Mab speech was famous for its freshness and spontaneity, the way each ‘sudden burst of fancy’ led to the next, ‘till the speaker abandoned himself to the brilliant and thronging illustrations which, amidst all their rapidity and fire, never lost the simple and spontaneous grace of nature in which they took rise’.Footnote 70 He was gallant and courtly in his banter with the Nurse, and made a point of grasping Romeo’s hand in forgiveness even at the moment of his death. His ‘heroic and courtly humorist’ was the definitive Mercutio of the nineteenth century.Footnote 71

Among other actors of the period, William Charles Macready had some success when he débuted as Romeo in 1810, but later audiences resisted his Romeo because of his appearance. His ‘want of personal attractions’ was noted in one review, which, according to Macready, observed that ‘Nature had interposed an everlasting bar to my success’ by being ‘unaccommodating … in the formation of my face’.Footnote 72 He later found himself reduced to playing Friar Lawrence, a part in which he found ‘no direct character to sustain, no effort to make’.Footnote 73

The greatest actor of the age, Edmund Kean, failed disastrously as Romeo; as William Hazlitt crushingly declared, ‘His Romeo had nothing of the lover in it. We never saw anything less ardent or less voluptuous … He stood like a statue of lead.’Footnote 74 The Drury Lane committee, noting the success Eliza O’Neill was having as Juliet at Covent Garden, decided to push their star actor into the play; Kean reluctantly accepted, opposite Mrs Bartley.Footnote 75 Hazlitt observed that Kean’s remarkable powers, which he admired, were particularly unsuited to Romeo: ‘Mr Kean’s imagination appears not to have the principles of joy or hope or love in it. He seems chiefly sensible to pain, or to the passions that spring from it.’ Accordingly, while he was effective in the Friar’s cell and the tomb, he was unconvincing before Juliet’s balcony: ‘His acting sometimes reminded us of the scene with Lady Anne [in Richard III]’, Hazlitt observed dryly, ‘and we cannot say a worse thing of it, considering the difference of the two characters.’ After the first three performances a different Juliet was tried, Miss L. Kelly, but to no avail. The play was taken off after nine performances, and Kean never attempted Romeo again.

The major English Shakespeareans of the Victorian period – Macready, Samuel Phelps, Charles Kean, and Henry Irving – were all better suited to tragic kingship than to the youthful ardour of Romeo. Phelps limited himself to Mercutio, and Charles Kean attempted Romeo only a few times, to bruising reviews. The response to his début in the role, opposite Miss C. Phillips, is not atypical of nineteenth-century biases: ‘Miss Phillips was a great success, and Kean a great failure. He was consequently very much humiliated and distressed.’Footnote 76 Though the play remained popular, Romeo became a role actors sought to avoid.

Victorian Actresses

For women it was a different story. Where virtually every important nineteenth-century actor failed as Romeo, virtually every important nineteenth-century actress succeeded as Juliet. In part this has to do with the importance of Juliet in the canon of nineteenth-century women’s parts; it was typically a début role, and if one failed in it, one was unlikely to have much of a subsequent career.

The position of actresses in the nineteenth-century theatre was an ambiguous one. Tracy Davis, in Actresses as Working Women, has pointed out the disproportionate hardships women faced in an ill-paid and highly competitive industry where they were often regarded as little better than prostitutes. Gail Marshall has argued that Victorian actresses were constrained by a dominant cultural ‘Galatea myth’ that positioned them as sculptures, silent and immobilised commodities for male visual and sexual appreciation. Kerry Powell has asserted that the Victorian theatre ‘conspired in producing repressive codes of gender even as it provided women with a rare opportunity to experience independence and power’.Footnote 77 Yet women achieved increasing numbers and economic success on the stage in the nineteenth century, and Romeo and Juliet was one of the chief vehicles by which they did so. Indeed, the history of nineteenth-century theatre is a long catalogue of triumphant débuts as Juliet.

The first was Eliza O’Neill, who débuted at Covent Garden in 1814. She was twenty-four but looked fifteen, and her performance called up hyperbole in all who saw it. ‘Through my whole experience hers was the only representation of Juliet I have seen,’ gushed Macready, who later played opposite her. ‘I left my seat in the orchestra with the words of Iachimo in my mind. “All of her, that is out of door, most rich! … She is alone the Arabian bird.”’Footnote 78 His apparently unselfconscious quotation of Iachimo, the villain who lustfully describes the beauties of the innocently sleeping Imogen in Cymbeline, says a good deal about how nineteenth-century spectators viewed their Juliets. Much of Macready’s account has this same voyeuristic quality:

It was not altogether the matchless beauty of form and face, but the spirit of perfect innocence and purity that seemed to glisten in her speaking eyes and breathe from her chiseled lips … There was in her look, voice, and manner, an artlessness, an apparent unconsciousness (so foreign to the generality of stage performers) that riveted the spectator’s gaze …

It is Juliet’s eyes that speak, while her lips are those of a statue; she is unconscious and innocent, but rivets the (male) spectator’s gaze. Macready’s effusions are firmly in line with the ‘Galatea aesthetic’ Gail Marshall has identified. The most famous critic of the age, William Hazlitt, resisted O’Neill’s performance, being partial to her great predecessor Sarah Siddons; but he did acknowledge her skill in ‘the silent expression of feeling’.Footnote 79

John Cole made an extended comparison between the two actresses that suggests much about the changing fashion between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries:

Inferior to Siddons in grandeur, and in depicting the more terrible and stormy passions of human nature, [Miss O’Neill] excelled that great mistress of her art in tenderness and natural pathos … Mrs Siddons presented a being exalted above humanity, to admire and gaze upon with wonder; but whom you hesitated to approach in familiar intercourse. Miss O’Neill invited sympathy, and while she suffered with intenseness, appeared incapable of retaliation.Footnote 80

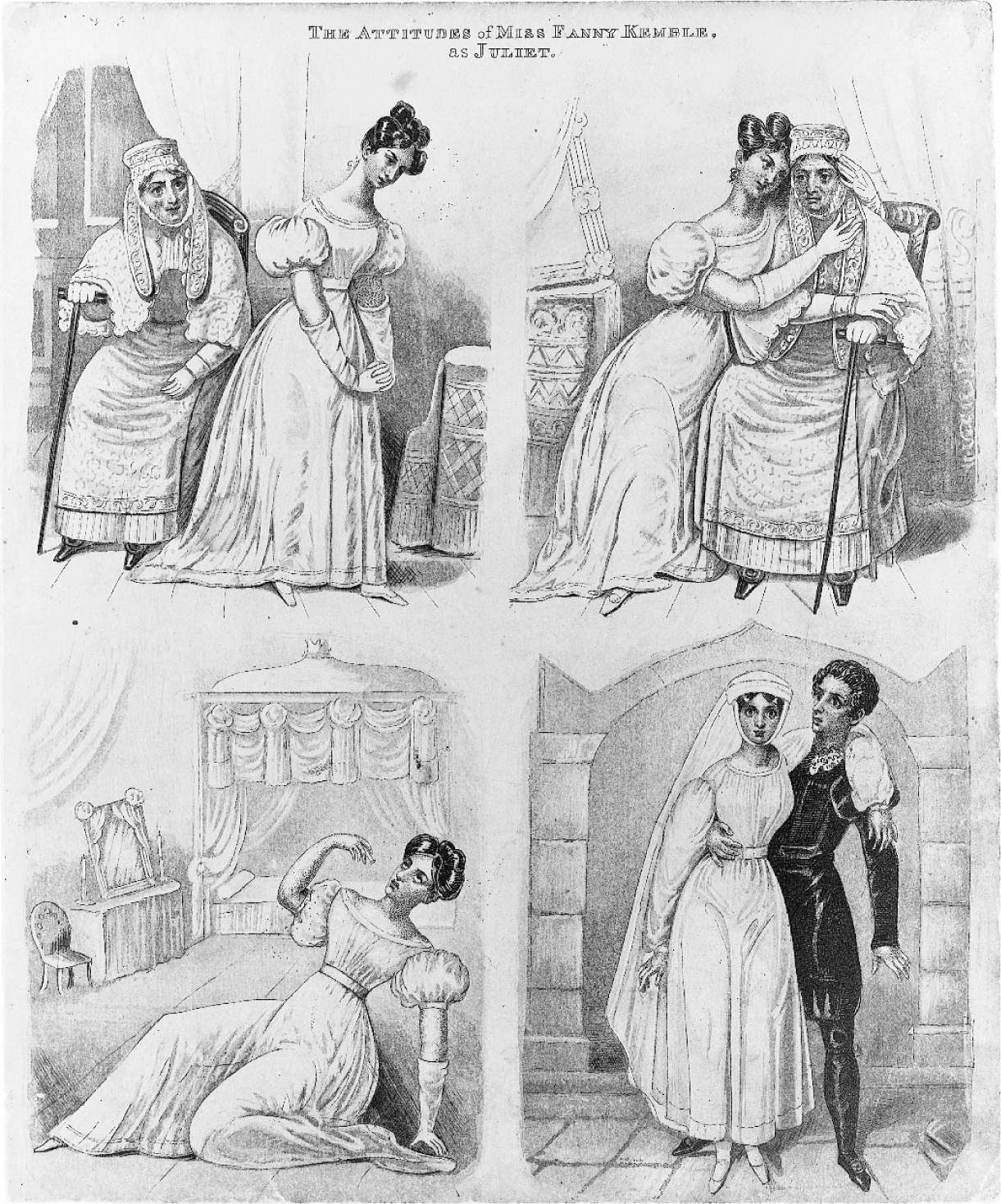

Eliza O’Neill, with her beauty, artlessness, susceptibility to ‘familiar intercourse’, and defenceless suffering, became the model for nineteenth-century Juliets. With her graceful figure, fair curls, and huge, easily weeping eyes, she was ‘a perfect image of loveliness in distress’, according to William Winter, and ‘evoked prodigious sympathy, – as loveliness in distress always will’.Footnote 81 Fanny Kemble, who succeeded her in the role, archly commented that O’Neill ‘was expressly designed for a representative victim’.Footnote 82 Nonetheless, accounts of Kemble’s own début stress similarly vulnerable qualities. Kemble first played Juliet at the age of twenty, at Covent Garden, with her father Charles playing Mercutio and her mother as Lady Capulet. Her first appearance was a metatheatrical emblem of innocence suffering under an oppressive gaze:

On her first entrance she seemed to feel very sensibly the embarrassment of the new and overwhelming task she had undertaken. She ran to her mother’s arms with a sort of instinctive impulse, but almost immediately recovered her composure … In the garden scene she gave the exquisite poetry of the part with a most innocent gracefulness … The scene with the Nurse was full of delightful simplicity.Footnote 83

In spite of the critical emphasis on her timidity, Fanny Kemble was given credit for saving her family’s management of Covent Garden. Romeo and Juliet was a tremendous success, and her career was launched. The vehement effusions of contemporary writers make it difficult to judge how Kemble actually played the role: Anna Jameson, for instance, says she did it ‘as though every line and sentiment in Shakespeare had been transplanted into her heart, – had long been brooded over in silence, – watered with her tears, – to burst forth at last, like the spontaneous and native growth of her own soul’.Footnote 84 Interestingly, Kemble’s writings reveal a degree of frustration with the character of Juliet, whom she calls a ‘foolish child’, and an intelligent and slightly cynical attitude toward the play: ‘I have little or no sympathy with, though much compassion for, that Veronese young person.’Footnote 85 She also had little tolerance for traditional and sentimental stage business; when Ellen Tree, as Romeo, wanted to carry her to the footlights in the tomb scene, Kemble declared, ‘If you attempt to lift or carry me down the stage, I will kick and scream till you set me down.’Footnote 86 Though she never again matched her initial success and was often a reluctant actress, Kemble was a perceptive critic and writer, full of insights into the role and the play. She observed to Clifford Harrison that ‘Romeo represents the sentiment, Juliet the passion, of love. The pathos is his, the power hers.’Footnote 87 She made her mark on the role of Juliet and continued to give readings of it, in public and private, until she was at least seventy.

Helena Faucit also made her début as Juliet, and identified herself with the part for much of her early life. In her book, On Some of Shakespeare’s Female Characters, she discusses her childish admiration for Juliet’s courage, and her terror in reading the tomb scene. She recalls playfully acting the balcony scene opposite her sister in the empty Richmond Theatre, being overheard, and thus being invited to play Juliet there at the age of thirteen. She felt her youth worked against her; she was ‘too near the age of Shakespeare’s Juliet, considering the tardier development of an English girl, to understand so strong and deep a nature’.Footnote 88 In the potion scene, Faucit recalls, she was so overwrought that she crushed the vial in her hand, and then genuinely fainted at the sight of her own blood staining her dress.

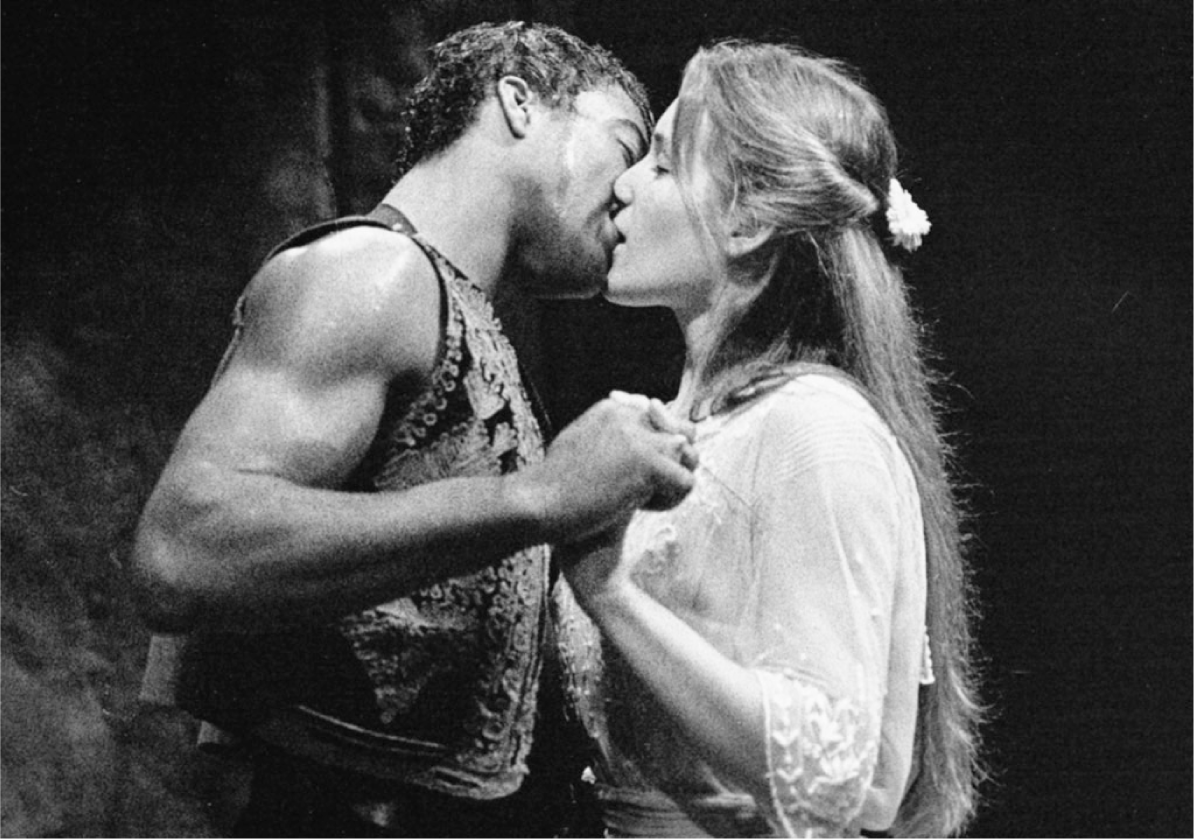

3 Fanny Kemble, from her 1829 Covent Garden performances: with the Nurse, taking the potion, and in Garrick’s version of the tomb scene.

Whether accurate or not, Faucit’s reminiscences embody the same combination of innocent fragility and unbidden, passive sexuality that made O’Neill and Kemble so successful in the role. As Gail Marshall argues, the story of Romeo and Juliet

enabled the display of, and contained its own solutions to the problems raised by, theatrical representations of female sexuality. Juliet’s youthfully unconscious desirability is invoked by others only to be obliterated by death … Juliet’s sexual awakening is amply contained by the dimensions of the tragedy, thus making the part the perfect vehicle for conveying the attractively malleable sexuality of the actress.Footnote 89

Faucit gave a highly successful performance at Covent Garden in 1836, and continued to play Juliet regularly for the next thirty-five years. Her ability to embody the ideal of Victorian womanhood was an important aspect of her performance. According to her husband and biographer Theodore Martin, ‘People saw in her not only a great actress, they felt themselves in the presence of one who was in herself the ideal woman of whom poets had written.’Footnote 90 Faucit to some extent played into this role, idealising Shakespeare’s heroines as ‘these sweet and noble representatives of our sex’, and declaring that ‘women are deeply in debt to Shakespeare for all the lovely noble things he has put into his women’s hearts and mouths’.Footnote 91 But her detailed discussion of the play, in On Some of Shakespeare’s Female Characters, reveals insights that go far beyond an idealised stereotype. For one thing, Faucit was rare in the nineteenth century in viewing the play in social terms rather than focusing solely on the protagonists; she felt Shakespeare’s ‘far wider and deeper’ purpose was obscured if the play ended, as it often did, with the deaths of the lovers.

Faucit’s account of the potion scene shows the pragmatic choices of an intelligent performer fully aware of the emotional demands of the role: ‘What a scene is this – so simple, so grand, so terrible! What it is to act I need not tell you. What power it demands, and yet what restraint!’ Her moment-by-moment account of the scene is full of vivid psychological details:

I always felt a kind of icy coldness and stillness come over me after leaving the Friar’s cell which lasted until this moment. The ‘Farewell!’ to Lady Capulet, – ‘God knows when we shall meet again’ – relaxed this state of tension.

I could never utter these words [about Tybalt’s corpse] without an exclamation of shuddering disgust accompanying them.

At the mention of Romeo’s name I used to feel all my resolution return.

By charting her own psychological journey through the scene, Faucit asserted a degree of creative autonomy, and to some extent transcended the objectification to which her performance on stage was subject. The writings of actresses like Faucit, together with other women like Mary Cowden Clarke (The Girlhood of Shakespeare’s Heroines) and Anna Jameson (Shakespeare’s Heroines), fleshed out the conception of Juliet that had been offered to the gaze of Victorian spectators. These character-studies, though in many ways false to the play, enabled women to lay claim to Juliet’s inner life, and insist on her depth and complexity.

Charlotte Cushman’s Romeo, 1845

If Victorian women were able, through their performances and writings, to give cultural prominence and variety to Shakespeare’s Juliet, they were also able to best their male counterparts in the role of Romeo. A variety of actresses played Romeo on the Victorian stage, including Caroline Rankley, Felicita Vestvalli, Fanny Vining, Margaret Leighton, Esmé Beringer, and Ellen Tree.Footnote 92 Tree played Romeo at Covent Garden in 1829, opposite Fanny Kemble, who described it as the ‘only occasion on which I ever acted Juliet to a Romeo who looked the part’.Footnote 93 According to John Cole, Tree’s ‘hazardous attempt’ achieved ‘singular success, all the newspapers being unanimous in her praise’.Footnote 94 Other female Romeos were less enthusiastically received: William Archer felt Esmé Beringer was ‘a clever young lady, and made a graceful, inoffensive and even intelligent Romeo … but for my part, I hold such travesties, in their very nature, unprofitable and unattractive’.Footnote 95 Nonetheless, the most acclaimed Romeo of the century – male or female – was the American actress Charlotte Cushman. Cross-dressing actresses had been common on the English stage since the Restoration, but in the nineteenth century women were able to transcend the crude bodily display that initially made ‘breeches parts’ popular. Actresses like Cushman who could convincingly embody male characters ‘dissociated breeches roles from their tradition of sexual titillation’, according to Sandra Richards.Footnote 96 Cushman defied and transcended gender roles even in female characters like Lady Macbeth, according to a contemporary critic, William Winter: ‘She was not a theatrical beauty. She neither employed, nor made pretence of employing, the soft allurements of her sex. She was incarnate power: she dominated by intrinsic authority: she was a woman born to command.’Footnote 97

Cushman ostensibly took the role of Romeo in order to showcase her sister Susan, who played Juliet; she wrote that she wanted to give Susan ‘the support I knew she required and would never get from any gentleman that could be got to act with her’.Footnote 98 The arrangement caused some concern among the citizens of Edinburgh, where they played before coming to London; her friend and fellow-actor John Coleman reports that ‘her amorous endearments were of so erotic a character that no man would have dared to indulge in them’.Footnote 99 Such comments were actually quite rare, though Lisa Merill has convincingly argued that Cushman’s performance enacted a passionate lesbian sexuality – which the public mostly took great pains to ignore.Footnote 100 Cushman defended herself by citing the precedent of Ellen Tree, and claiming that her performance opposite her sister was less indelicate than Fanny Kemble’s, who played Juliet to her father’s Romeo on a US tour. In any event, when Romeo and Juliet opened in London in December 1845, it was clear not only that Cushman’s Romeo was acceptable to the public, but that she was the star of the production; Susan’s Juliet passed almost unnoticed.

Cushman’s Romeo was noteworthy in part because she used Shakespeare’s original text instead of Garrick’s. She was not the first to do so; Madame Vestris had apparently attempted it, without success, in 1840.Footnote 101 Cushman herself had played the Garrick text in the US, but for the Haymarket she insisted on reverting to Shakespeare. Cushman’s version was not by any means complete, and indeed she made many of the same cuts as Garrick and Kemble. According to the Lacy edition of 1855, she cut the Prologue, the servants’ bawdry and the entry of the Capulet and Montague wives in 1.1, much of the discussion of Rosaline’s chastity, most of the Nurse’s story of Juliet’s childhood, most of the bawdy jesting of Mercutio, Benvolio’s report of the duel in 3.1, some of the lamentations in the ‘banished’ scenes, and much of the Friar’s counsel, much of the mourning for Juliet in 4.5, the Musicians, and a certain amount of the final recapitulation and sorting of evidence. Perhaps not surprisingly, her version favoured the part of Romeo at the expense of nearly everyone else. Her return to Shakespeare had the crucial effect of expanding Romeo’s character by including his early passion for Rosaline. Passion was the keynote of her performance; as one review remarked, ‘Miss Cushman has suddenly placed a living, breathing, burning Italian upon boards where we have hitherto had an unfortunate and somewhat energetic Englishman.’Footnote 102 The Times concurred: ‘For a long time Romeo has been a convention. Miss Cushman’s Romeo is a creative, a living, breathing, animated, ardent human being’ (30 December 1848). James Sheridan Knowles compared her Romeo to Kean’s Othello, citing ‘the genuine heart-storm’ of the banishment scene: ‘not simulated passion, – no such thing; real, palpably real’.Footnote 103 Several critics commented that Cushman was restoring a previously lost role:

The character, instead of being shown to us in a heap of disjecta membra, is exhibited by her in a powerful light which at once displays the proportions and the beauty of the poet’s conception. It is as if a noble symphony, distorted and rendered unmeaning by inefficient conductors, had suddenly been performed under the hand of one who knew in what time the composer intended it should be taken.

While her unified and passionate grasp of the role was widely praised, her gender certainly didn’t pass without comment. Queen Victoria herself went to see her, and was surprised by her authentically masculine performance:

Miss Cushman took the part of Romeo, and no one would ever have imagined she was a woman, her figure and her voice being so masculine, but her face was very plain. Her acting is not pleasing, though clever, and she entered well into the character, bringing out forcibly its impetuosity.Footnote 104

In the one surviving photo of Cushman as Romeo, taken in the 1850s, she looks obviously female and middle-aged, but in 1845 audiences had no difficulty responding to her as a passionate young man.Footnote 105 Joseph Leach summarises the contemporary response: ‘Few Romeos in London’s memory had looked young enough and passionately agile enough to be convincing, but watching this fiery young gallant, one witness was soon exclaiming that this Miss Cushman seemed “just man enough to be a boy!”’Footnote 106

At some level, Cushman was able to succeed as Romeo, where men failed, because of her gender. One reviewer, commenting on recent male performances, observed that ‘there is no part more difficult to sustain efficiently than Romeo. At one time we have seen it a lifeless, sickly, and repulsive conception; at another a rough, indelicate, animal picture.’Footnote 107 The character of Romeo, as understood in the nineteenth century, was incompatible with Victorian notions of masculinity. As an article in Britannia observed, in reference to Cushman’s performance, ‘It is open to question whether Romeo may not best be impersonated by a woman, for it is thus only that in actual representation can we view the passionate love of this play made real and palpable.’Footnote 108 Indeed, Victorian productions of Romeo and Juliet seem to suggest a rare case where gender bias, in a small way, liberated women and hindered men. Where Victorian women used a range of performances, and their considerable writings on the play, to assert a degree of female subjectivity and independence, their male counterparts repeatedly failed as Romeo; and failed, at least in part, because they just weren’t sexy enough. Emma Stebbins, companion and biographer of Charlotte Cushman, thought that Victorian actors were simply too old and ugly for Romeo: ‘Who could endure to see a man with the muscles of Forrest, or even the keen intellectual face of Macready, in the part of a gallant and loving boy?’ Turning the tables on an oft-repeated aphorism about Juliet, Stebbins put male actors firmly in their place: ‘When a man has achieved the experience requisite to act Romeo, he has ceased to be young enough to look it.’Footnote 109 For most of the nineteenth century, the English theatre-going public seems to have agreed.

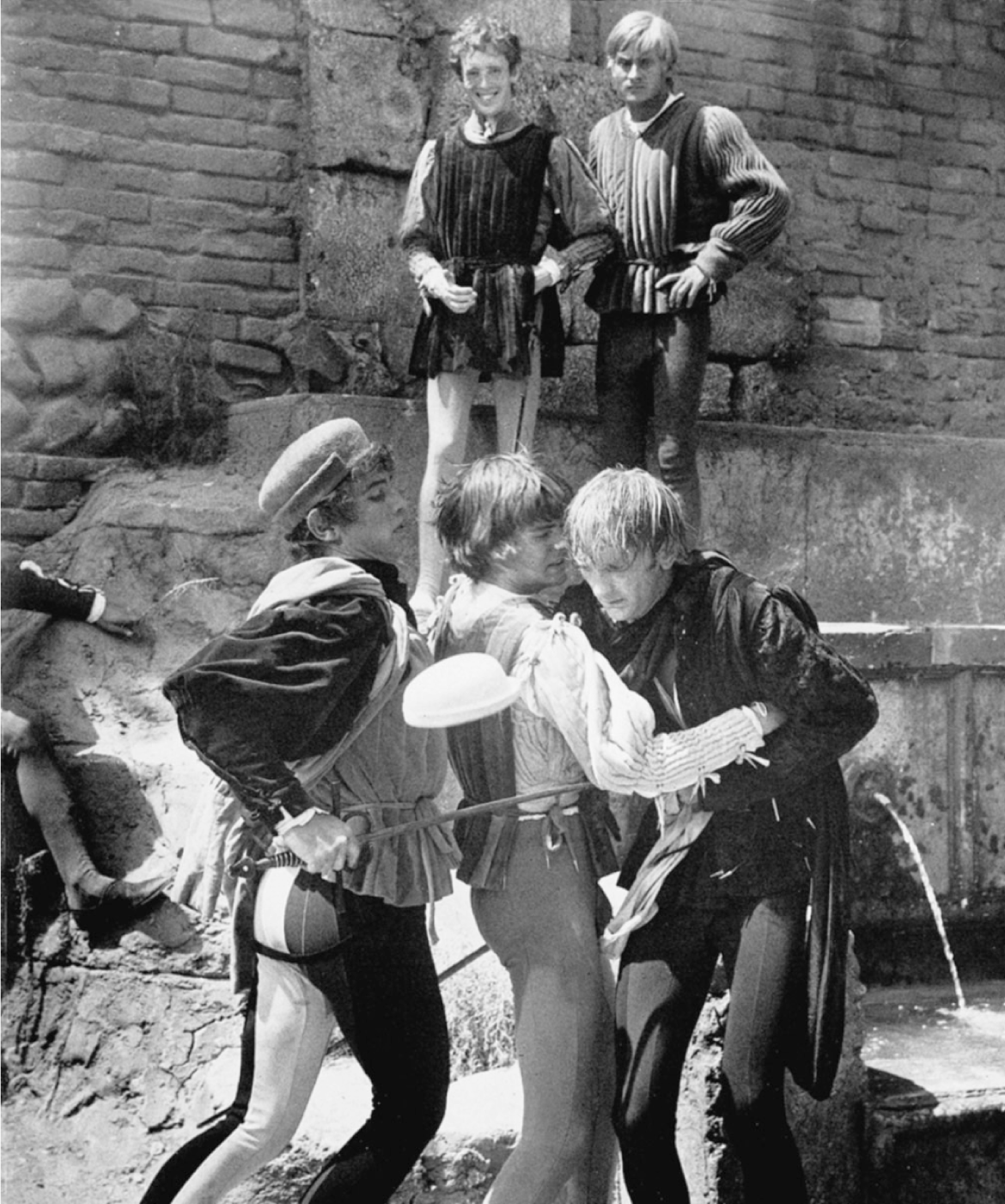

4 Charlotte Cushman, the most successful woman to take the role, in her costume as Romeo, c. 1855.

Henry Irving and Ellen Terry at the Lyceum, 1882

Cushman’s success broke the hold of the Garrick–Kemble version of Romeo and Juliet, but it by no means meant a return to full Shakespearean texts. Not only were the many sexual references consistently censored, but theatrical conventions prompted heavy cutting for various reasons. London’s two patent theatres had greatly increased in size and scenic capabilities. After fires in 1808 and 1809, Covent Garden and Drury Lane were rebuilt with seating capacities of 3,044 and 3,611 respectively, roughly twice the size they had been in Garrick’s day. In such a cavernous theatre, the nimble banter of Mercutio could have much less impact than a rhetorical set piece like Juliet’s potion speech, and the play was cut accordingly. The need for slower, more demonstrative playing increased as a series of renovations reduced and eventually eliminated the stage apron, leaving a picture-frame opening measuring 12.8 metres (42 feet) across at Covent Garden, with wings of 6 metres (20 feet).Footnote 110 Through this proscenium audiences viewed more and more elaborate scenery, complemented, after 1817, by gas lighting. New scenes, rather than stock flats, came to be employed (and advertised) for major new productions; the painter’s art was increasingly supplemented by that of the carpenter, as more and more elaborate three-dimensional structures were employed. The difficulty in changing these caused managers to cut and rearrange scenes in order to simplify the staging; for instance, 4.2 and 4.4 were regularly cut, so that the only sets needed for the fourth act were the Friar’s cell and Juliet’s bedroom. A representative production was that of Charles Kean, the antiquarian son of Edmund, who played Romeo opposite his wife Ellen Tree at the Haymarket in 1841. Charles Marshall designed thirteen separate scenes that carefully reproduced the art and architecture of the Italian Renaissance; the brief Mantua scene, 5.1, even had a recognisably different architectural style from the Verona scenes.

One exception to the prevailing trend was Samuel Phelps. After the Theatre Regulation Act of 1843 abolished the monopoly of the patent houses, Phelps took over the management of the unfashionable Sadler’s Wells Theatre, where he staged all but four of Shakespeare’s plays, emphasising acting and poetry over scenic spectacle. He played Mercutio with William Creswick and Laura Addison in 1846, using a remarkably full text unrivalled until the twentieth century. The Nurse’s story was complete (except for her reference to ‘a young cock’rel’s stone’, 1.3.54), Phelps allowed himself most of Mercutio’s banter, and every scene of Shakespeare’s play was included in some form. Both Benvolio and the Friar retained their accounts of past events, and the mourning for Juliet in 4.5 was included, with only the Musicians gone. In a smaller theatre, with less scenery to change, Phelps was able to give a virtually complete performance of the play, anticipating the ‘Shakespeare revolution’ led by William Poel and Harley Granville-Barker at the beginning of the next century.

Phelps had few imitators, however, and the other London theatres continued to opt for spectacle. The culmination of the Victorian pictorial tradition came with Henry Irving’s production of Romeo and Juliet at the Lyceum, opening 8 March 1882. Irving’s conception of the play, from the beginning, was visual. According to Ellen Terry, he observed that ‘Hamlet could be played anywhere on its acting merits. It marches from situation to situation. But Romeo and Juliet proceeds from picture to picture. Every line suggests a picture. It is a dramatic poem rather than a drama, and I mean to treat it from that point of view.’Footnote 111

Accordingly, Irving created a theatrical experience of unprecedented splendour and expense. The play was given in twenty-two scenes, most of which had different sets, solidly constructed in three dimensions. He made innovative use of lighting to enhance his changes of scenery, producing ‘a sort of richness of effect and surprise as the gloom passes away and a gorgeous scene steeped in effulgence and colour is revealed’.Footnote 112 The production clearly used every resource the Victorian theatre could afford. Clement Scott responded to the combination of scenery, lighting, and music by which Irving created an Italian world:

Such scenes as these – the outside of Capulet’s house lighted for the ball, the sunny pictures of Verona in summer, the marriage chant to Juliet changed into a death dirge, the old, lonely street in Mantua where the Apothecary dwells, the wondrous solid tomb of the Capulets – are as worthy of close and renewed study as are the pictures in a gallery of paintings.Footnote 113

In the costumes, which Irving designed along with Alfred Thompson, he sought to convey ‘the rich harmonies and bold compositions of the Italian masters’.Footnote 114 Sir Julius Benedict provided accompanying music in the Italian manner.

Much of Irving’s direction seems to have been theatrically effective. Irving had seen the Duke of Saxe-Meiningen and his company play in London the previous year, and imitated his method of directing crowd movement. The opening fight was particularly gripping, according to Bram Stoker, as the Montagues pushed the Capulets downstage over a bridge: ‘they used to pour in on the scene down the slope of the bridge like a released torrent, and for a few minutes such a scene of fighting was enacted as I have never seen elsewhere on the stage’.Footnote 115 Ellen Terry, though dissatisfied with her own performance as Juliet, agreed that the production was visually breathtaking:

In it Henry first displayed his mastery of crowds. The brawling of the rival houses in the streets, the procession of girls to wake Juliet on her wedding morning, the musicians, the magnificent reconciliation of the two houses which closed the play, every one on the stage holding a torch, were all treated with a marvellous sense of pictorial effect.Footnote 116

In this last scene, Irving achieved a coup de théâtre that demonstrated his confident marshalling of Victorian stage techniques. Not content with a single image for churchyard and tomb, he divided 5.3 into two distinct scenes. Romeo killed Paris in a moonlit gothic churchyard, from which Irving moved the scene into the tomb with an almost cinematic dissolve, as one critic later recalled:

Seizing his torch and dragging after him the lifeless form of his antagonist, Romeo disappeared, descending into the vault below. While the flare of his torch still reddened the damp walls of the entrance, the picture faded from view. Silently it came; as silently it vanished … Again the darkness became luminous, and the outlines of a deep cavern, hewn in solid rock, grew before the eye. It was the crypt in which rested the Capulet dead. High up in the background was seen an entrance from which a staircase, rudely fashioned in the rock, wound downward on the left to the cavern floor, and through which the moonlight streamed and fell upon the form of Juliet lying upon a silken covered bier in the foreground. Immediately the scene was developed Romeo appeared at the entrance leading from the churchyard above, bearing his flaming torch, and with the corpse of Paris in his arms, descended the rocky stairway to the bottom of the tomb.Footnote 117

Irving spent hours practising how best to carry the body; in the end he substituted a dummy for the actor of Paris, but insisted that it be the appropriate weight and dimensions.Footnote 118 His care paid off, as this became the most memorable effect of the production. Even Shaw, no fan of Irving’s, was haunted by the image years later: ‘One remembers Irving, a dim figure dragging a horrible burden down through the gloom “into the rotten jaws of death”.’Footnote 119

Irving prepared his own version of the text, cutting the bawdry as usual, judiciously eliminating all references to Juliet’s age (Ellen Terry was thirty-six, Irving forty-four), and dropping 4.2 and 4.4 to accommodate the scenery. Following Cushman, he retained and even emphasised Romeo’s love for Rosaline: ‘Its value can hardly be over-appreciated, since Shakespeare has carefully worked out this first baseless love of Romeo as a palpable evidence of the subjective nature of the man and his passion.’Footnote 120 He even carefully chose a tall dark actress to play Rosaline at the ball. ‘Can I ever forget his face,’ Terry asked rhetorically, ‘when in pursuit of her he saw me.’Footnote 121

By a good margin, the performances were less successful than the stage effects. The one triumph was Mrs Stirling’s Nurse, a definitive performance for the era. The young and handsome William Terriss played a vigorous Mercutio, and many felt he should have been Romeo, as indeed he was in Mary Anderson’s Lyceum production two years later. Irving achieved a few powerful effects in scenes of melancholy and despair; his reception of the news of Juliet’s death, and his subsequent visit to the Apothecary, were his best moments. But Irving’s age, his intellectuality, his bony figure and hoarse voice, all precluded a successful characterisation of the young lover. As Henry James observed, ‘How little Mr Irving is Romeo it is not worth while even to attempt to declare; he must know it of course, better than anyone else, and there is something really touching in so extreme a sacrifice of one’s ideal.’Footnote 122 A less charitable critic compared Irving to ‘a pig who has been taught to play the fiddle. He does it very cleverly, but he would be better employed in squealing.’Footnote 123 Irving’s inadequacy did not, however, prevent the production from running for over a hundred performances.

Terry’s Juliet was not a success, though it was not quite so great a failure as Irving’s Romeo. One of the chief complaints against Terry was that she was simply ‘too English’, in Henry James’s phrase. Her Victorian heroine lacked ‘the joy of this passionate young Italian’, as Terry characterised her.Footnote 124 One critic wrote, ‘Miss Ellen Terry is very charming, but she is not Juliet; and when really tragic passion is wanted for the part, it is not forthcoming.’Footnote 125 Ironically, Terry’s relative lack of success as Juliet seems to have been due in part to the ideal of Victorian womanhood she embodied. She was unable to compete with a new conception of Juliet that went beyond the fragile, unconscious sexuality of O’Neill and her followers. In several reviews, Terry was compared unfavourably with the darkly passionate, doom-laden Juliet of Adelaide Neilson.Footnote 126

Foreign Juliets of Late-Victorian Times

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, several actresses succeeded as Juliet by playing against the English conception of the role. Capitalising on the Imperial fascination with the exotic and foreign, and the licence associated with other cultures, Adelaide Neilson, Stella Colas, and Helena Modjeska achieved considerable success and extended the possibilities for performing Juliet.

Neilson, who played Juliet from 1865 to 1879, was actually from working-class Leeds, but she wrapped herself in an aura of illicit Mediterranean sexuality. Allegedly the natural daughter of a Spanish artist and an English gentlewoman, raised at Saragossa and educated in Italy, she owed to this upbringing ‘the richness of her voice, the depth of expression in her dark eyes, the sensuous grace of her movements, the burning energy of passion which she displays as the tragedy progresses’.Footnote 127 Her phoney origins, her dark beauty, and her death at the age of thirty-two all contributed to her legend, but she clearly was a remarkable performer. What critics chiefly comment on is her very un-Victorian passion. William Winter writes that ‘her performances were duly planned, and her rehearsals of them conscientious; but at moments in the actual exposition of them her voice, countenance and demeanor would undergo such changes, because of a surge of feeling, that her person became transfigured, and she was more like a spirit than a woman’.Footnote 128 None of her competitors could match her in ‘manifesting the bewildering, exultant happiness of Juliet, or her passion, or her awestricken foreboding of impending fate’. These notes of open sexuality and tragic doom made her Juliet distinctively different from the innocent heroines who had preceded her. Her supposed otherness enabled her to stretch the role of Juliet beyond the conventional Victorian expectations for the part.

Several other actresses succeeded as Juliet in Victorian London by exploiting their foreign origins. Stella Colas, a French actress, had a period of success in the role, both in London (first in 1863) and at the Tercentenary celebrations in Stratford in 1864. Colas had a thick French accent, was considered a great beauty, and performed with ‘a strong voice and much force, volitive and physical’.Footnote 129 Her merits as an actress were much debated. Clement Scott commended her youth, beauty, and passion in the early scenes, and the tragic force of her potion speech. In the balcony scene, he felt, ‘her foreign origin enabled her to delight us with those tricks, fantastic changes, coquettings, poutings, and petulance which come with such difficulty from the Anglo-Saxon temperament’.Footnote 130 In the potion scene, by contrast, she ‘turned positively green with fear, and became prematurely old, ugly, and haggard’, uttering a terrifying shriek as she lapsed into momentary madness. Henry Morley thought her coquetry in the balcony scene ‘abominable’, and her shrieking at Tybalt’s ghost a ‘claptrap stage effect’ done with ‘a great deal of misdirected force’.Footnote 131 George Henry Lewes found her lacking in spontaneity and tiresomely over-emphatic: ‘With all her vehemence, she is destitute of passion; she “splits the ears of the groundlings”, but moves no human soul’.Footnote 132 Her accent hindered her somewhat, but her beauty, energy, and non-English passion seem to have compensated for it, at least for the popular audience.