Political scientists have long argued that democracies require supportive democratic cultures in which individuals share attitudes and values favouring participation in public affairs (e.g. Almond and Verba Reference Almond and Verba1965). Popular participation is key to the functioning of democratic systems, with variations in political participation being often associated with citizens' support for, or opposition to, democratic institutions, values and principles. Since the turn of the century, scholars studying young people's views and political involvement in contemporary democracies have evidenced a change that has been interpreted in starkly different ways (see Weiss Reference Weiss2020). Several authors have stressed the progressive alienation of young people from mainstream forms of democratic life (Delli Carpini Reference Delli Carpini2000; Quintelier Reference Quintelier2007; Ross Reference Ross2018). Yet, recent scholarship has questioned these findings, suggesting instead that younger generations engage through other forms of participation, which challenge traditional understandings of democratic politics (Earl et al. Reference Earl, Maher and Elliott2017; Pickard Reference Pickard2019).

Against this backdrop, this article engages in a detailed analysis of the nexus between young people's democratic attitudes and political engagement in the context of Western European democracies. Specifically, the article offers a finer-grained understanding of the relationship between youth and democratic engagement. Our analysis examines ingroup attitudinal differences among young people and investigates whether attitudes of opposition to democracy are more likely to decrease political mobilization among youngsters than among groups of older people.

Building on the association between democratic attitudes and behaviour, we first examine the extent to which attitudes of opposition to democracy – that is, attitudes of critical concern towards the democratic regime, system functioning and its principles – vary across age groups. Our data show significant group variation among the attitudes of young Western Europeans. Attitudes opposing democracy are stronger and more prevalent among young people aged 25–34 than among young people aged 18–24, advancing a non-linear negative association between attitudes of opposition to democracy and age. Second, our analysis sheds light on the youth ‘participation paradox’ (Pleyers and Karbach Reference Pleyers and Karbach2014).Footnote 1 Specifically, we show that opposition to democracy shapes both voting and protest behaviours (1) always negatively but (2) regardless of age. Although young people tend to oppose democracy more than their older counterparts (aged 35+), their critical concerns about democracy are no more likely to translate into greater democratic disengagement than among older individuals.

Drawing on survey data with booster samples of young respondents collected across nine European countries, we empirically compare the relationship between attitudes of opposition to democracy and political behaviour among age groups. By investigating heterogeneity in attitudes both within younger age groups and between age groups (young–old), we challenge and nuance narratives that depict young people as a homogeneous and disaffected group of citizens. In fact, studying youth attributes is important to understanding democratic life, and such attributes are likely to crystallize in different configurations of values and patterns of democratic engagement over time. Specifically, our evidence shows that young adults who were in their teens and early 20s in the midst of the Great Recession (2010–2013) hold more attitudes of opposition to democracy, suggesting that contextual conditions and experiences of political socialization are key for democratic support. Accordingly, the relationship between young people's attitudes and democratic politics takes place within broader political and social processes.

In the next sections, we review the relevant literature and develop our theory linking young people and democratic attitudes, between- and within-group heterogeneity and political mobilization. Then we present our data and methodological design, followed by our empirical analyses and discussion of the main results. We conclude by discussing the implications and limitations of this article, and also signal avenues for further research.

Young people and opposition to democracy

Scepticism about the role of young people in democracy has long been framed as part of broader problematic trends in contemporary Western democracies. Studies pointing to a generalized weakening of civic life, falling voter turnout and declining party membership warn that these trends are especially acute for younger generations (Franklin Reference Franklin2004; Putnam Reference Putnam2000; van Biezen et al. Reference van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012). At the turn of the century, it was suggested that youth political engagement was at an unhealthily low point (Delli Carpini Reference Delli Carpini2000). As Pippa Norris argued, ‘political disengagement is thought to affect all citizens but young people are believed to be particularly disillusioned about the major institutions of representative democracy, leaving them apathetic (at best) or alienated (at worst)’ (cited in Sloam Reference Sloam2014a: 664).

Scholars have underscored that young people's lack of commitment to liberal democratic values and institutions results in lower political engagement relative to past generations (Ross Reference Ross2018). Widespread democratic disaffection among young people could lead to instability and ‘democratic deconsolidation’, exposing established democracies to authoritarianism, extreme instability of the party system and even threatening the survival of democratic regimes (Foa and Mounk Reference Foa and Mounk2016). Roberto Foa and Yascha Mounk (Reference Foa and Mounk2019) further sustain that in some parts of continental Europe where youth face systematic economic and social discrimination, ‘apathy has become active antipathy’, involving the active embracing of illiberal preferences and hostility against pluralistic institutions. Indeed, young people seem especially attracted to nationalist populist parties, which are bound to damage liberal democracy (Eatwell and Goodwin Reference Eatwell and Goodwin2018). In this view, young individuals would be more problematic for democracy than their parents and grandparents (Foa and Mounk Reference Foa and Mounk2017).

As a result, young citizens' democratic disaffection tends to be interpreted as a decline of support for democracy in terms of interest, participation, values and trust in institutions. Yet, young citizens' low levels of participation, low trust and critical views of representative democratic institutions are not necessarily a path to democratic disaffection – and apathy (Ellison et al. Reference Ellison, Pollock and Grimm2020; Hooghe and Marien Reference Hooghe and Marien2013). Concerns about young citizens lacking support for or even being opposed to liberal democracy's institutions, values and system functioning must be tempered. Ronald Inglehart (Reference Inglehart2016) argues that discourses of ‘democratic deconsolidation’ overstate threats to democracy and misunderstand its causes. He suggests that this is especially true when it comes to young people, whose democratic disaffection and scepticism are rooted in the rise in feelings of insecurity rather than in a rejection of liberal democracy and modernization. Norris (Reference Norris2017) argues that younger generations' scepticism towards liberal democracy manifests a critical questioning about democratic performance rather than an opposition to democracy. Amy Alexander and Christian Welzel (Reference Alexander and Welzel2017) show that young people are probably more supportive of democracy than ever before, given the fundamental moral and lifestyle changes they express, while their democratic disaffection is only weak and linked to life-cycle effects rather than generational ones.

Young people are generally more satisfied with democracy than older citizens (Zilinsky Reference Zilinsky2019), and a wealth of studies point to younger generations shifting to ‘do it ourselves’ (DIO) political behaviours (Mirra and García Reference Mirra and García2017; Pickard Reference Pickard2019; Pontes et al. Reference Pontes, Henn and Griffiths2019). These forms of engagement – strongly associated with self-expressive values – go beyond formal, institutional and routinized electoral politics (‘duty-based citizenship’). DIO behaviours embed politics in daily life practices through different repertoires of action (‘engaged citizenship’), such as digital media activism, political consumerism, volunteering, protesting, boycotting, staging public performances and more (Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Della Porta Reference Della Porta2019; Earl et al. Reference Earl, Maher and Elliott2017; Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni, Grasso, Giugni and Grasso2021; Holecz et al. Reference Holecz, Fernández and Giugni2021; Pickard Reference Pickard2021; Pickard et al. Reference Pickard, Bowman, Dena, Grasso and Giugni2022; Quaranta Reference Quaranta2015; Zukin et al. Reference Zukin, Keeter, Andolina, Jenkins and Delli Carpini2006). Therefore, rather than being democratically disaffected or even opposed to democracy, young people participate in politics differently to older generations in their respective contexts.

In contrast to narrow conceptions of democratic engagement that conceive a ‘right way’ to participate, a wealth of research sees young people as driving forces of social and political change (García-Albacete Reference García-Albacete2014; Grasso Reference Grasso2016; Pickard Reference Pickard2019; Pickard et al. Reference Pickard, Bowman, Dena, Grasso and Giugni2022). Around the world, recent mass mobilizations have brought to the fore groups of young people critical of the extant political offer and who desire to participate in democratic life, in ways that liberal democracies struggle to meet (Cammaerts et al. Reference Cammaerts, Bruter, Banaji, Harrison and Anstead2014). As illustrated by mass protests of the ‘outraged people’ against austerity policies and corruption, the Occupy mobilizations against the excesses of global capitalism, and the emergence of new movement parties, ‘youth activism has become a major feature of the European political landscape’ (Sloam Reference Sloam2014b: 217). These observations also seem to hold for contemporary European mobilizations, including the school strikes for climate or the Ni Una Menos (Not One Woman Less) feminist marches, where young people played a leading role (Chironi Reference Chironi2019; de Moor et al. Reference de Moor, Uba, Wahlström, Wennerhag and de Vydt2020; Portos Reference Portos2019).

Studying attitudes of opposition to democracy

While knowledge about empirical research on support for democracy is fragmented across different models and conceptions of democracy (König et al. Reference König, Siewert and Ackermann2021), in this study we want to assess (young) people's support for, or opposition to, democracy in general – and not just their preference for one of its manifestations (e.g. liberal, direct, stealth, populist). Specifically, when studying opposition to democracy, we adhere to David Easton's seminal distinction between diffuse and specific support for democracy:

Whereas specific support is extended only to the incumbent authorities, diffuse support is directed towards offices themselves as well as towards their individual occupants. More than that, diffuse support is support that underlies the regime as a whole and the political community … we are here drawing attention to support given to, or withheld from, those political objects that, for the understanding of political systems, have a theoretical significance very different from support for the incumbents of political offices alone. (Easton Reference Easton1975: 445)

We argue that attitudes of opposition to democracy consist of three aspects: namely its regime, system functioning and principles. Some authors have claimed that these aspects pertain to two separate dimensions, referring to a general assessment of democracy and to the outcomes of democratic governance (Ciftci Reference Ciftci2010: 1449–1450). However, these three aspects of diffuse democratic support tap into three types of concerns traditionally understood as relevant to an opposition to democracy (see Gorman et al. Reference Gorman, Naqvi and Kurzman2018). First, culturalist concerns link attitudes towards regime desirability to societal values. Second, developmentalist concerns connect attitudes towards system functioning to economic and/or social evaluations. Finally, elitist concerns focus on attitudes pertaining to core principles – for example equality among citizens (Gorman et al. Reference Gorman, Naqvi and Kurzman2018).

Within- and between-group heterogeneity

Traditionally, the literature has investigated youth political participation through arguments about life cycle and personal constraints (Highton and Wolfinger Reference Highton and Wolfinger2001; McAdam Reference McAdam1986; Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). The available empirical evidence suggests that significant life transitions influence people's political engagement (Elder and Johnson Reference Elder, Johnson, Mortimer and Shanahan2003). Scholars have shown that young citizens are more active in non-conventional forms of participation according to different levels of ‘biographical availability’ (Beyerlein and Bergstrand Reference Beyerlein, Bergstrand, Snow, Della Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013; McAdam Reference McAdam1986).Footnote 2 Overall, positions in the life cycle and access to resources have been shown to favour young citizens' political participation (Lorenzini et al. Reference Lorenzini, Monsch and Rosset2021; Marquis et al. Reference Marquis, Kuhn and Monsch2022).

Whereas it is still the case that ‘hardly any research has looked at patterns of engagement “within” a generation of young people across different democracies’ (Sloam Reference Sloam2013: 836), recent studies suggest that variations among groups of young people can be salient. In particular, inequalities related to gender, migration background and socioeconomic status influence young Europeans in different ways (Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni, Grasso, Giugni and Grasso2021; Quintelier and Hooghe Reference Quintelier and Hooghe2013). Maria Grasso and Marco Giugni (Reference Grasso and Giugni2022; see also Henn and Foard Reference Henn and Foard2014) show across several European countries that large class inequalities between young people negatively affect their views about democracy.

Additionally, young people suffer from lack of access to housing, from high education-related debts and from structural changes in the labour market, affecting their human capital investments and exacerbating patterns of inequality (Holdsworth Reference Holdsworth2017; Pickard and Bessant Reference Pickard and Bessant2018). Young Western Europeans are inserted in networks of international mobility, which are assets and constraints for developing their material and social resources. These aspects are associated with increased knowledge and civic skills, which remain key components of democratic life, as stressed by the civic voluntarism model (Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Accordingly, inequalities related to access to labour markets and unemployment, education, socialization and politicization are expected to have an asymmetric impact on attitudes towards democracy across different young milieus, not just relative to older generations.

Beyond the well-known effects of inequalities and life-cycle events such as school transition, starting a family or entering the labour force, young age groups could also exhibit divergent patterns of attitudes of opposition to democracy because they have experienced different social, economic and political opportunities that are dependent on broad contexts (Grasso et al. Reference Grasso, Farrall, Gray, Hay and Jennings2019), especially in their formative years. Experiences of socioeconomic turmoil can leave a deep imprint on young people's political socialization, attitudes and broader democratic engagement (García-Albacete and Lorente Reference García-Albacete and Lorente2021; Marquis et al. Reference Marquis, Kuhn and Monsch2022). Moreover, young people who have come of age in periods of heightened social unrest – as was the case during the Great Recession – are more likely to have a common understanding of their political environment (Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni and Grasso2019; Grasso Reference Grasso2014; Lorenzini et al. Reference Lorenzini, Monsch and Rosset2021), combining high levels of dissatisfaction with political (dis)engagement in the long term (García-Albacete and Lorente Reference García-Albacete and Lorente2021).

However, the implications of the above aspects are difficult to explore through analyses of young people's political attitudes and behaviour, which tend to focus on comparisons among cohorts or generations, overlooking differences between small generational groupings. In fact, as members of generational subsets, small age groups might encounter changing opportunities and constraints that affect thresholds for action due to their access to resources and networks (Johnston and Aarelaid-Tart Reference Johnston and Aarelaid-Tart2000; Whittier Reference Whittier1995). To capture this potential diversity across subsets of age groups among young individuals, we distinguish between the ages 18–24 and 25–34 while controlling for inequality-engendering factors at the individual level. We study how age-group effects are associated with attitudes of opposition to democracy.

Following the life-cycle arguments, we expect attitudes of opposition to democracy to vary among young age groups. Specifically:

Hypothesis 1: Attitudes of opposition to democracy are greater for younger – relative to older – age groups.

Conversely, following arguments of youth heterogeneity between small generational groupings, we expect significant intergenerational attitudinal variation between the age group of 25–34, who came of age during the Great Recession, and their younger counterpart group of 18–24, who did not. Thus:

Hypothesis 2: Attitudes of opposition to democracy vary between subsets of young people, with those aged 25–34 being more opposed to democracy than those aged 18–24.

Attitudes to democracy and mobilization

Having discussed attitudinal aspects with respect to subsets of young people, we now focus on their association with political mobilization, which is a fundamental feature for promoting collective interests and maintaining collective goods in democracy (Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Following the civic voluntarism model once again, young people engage in politics provided they have resources and networks, develop democratic attitudes comprising interest and are willing to act (Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Engaging in political action is key to ensuring effective representation, and political repertoires – that is, the practices through which citizens give voice to their claims – are central to defining associations between democracy and citizenship (Grasso Reference Grasso2016, Reference Grasso, Pickard and Bessant2018). This relationship between attitudes and political participation has been crucial for understanding assumptive discourses of youth democratic disaffection and political disengagement (Grasso Reference Grasso, Pickard and Bessant2018; Holecz et al. Reference Holecz, Fernández and Giugni2021; Pickard Reference Pickard2019; Pickard and Bessant Reference Pickard and Bessant2018).

Arguments that stress young people's democratic disaffection suggest that attitudes opposing democracy are stronger among young individuals, leading to greater demobilization among young milieus. The tendency to refer democratic values and participation solely to ‘liberal institutions’ has favoured a conception of democracy as less entrenched among millennials than among their baby-boomer parents (Foa and Mounk Reference Foa and Mounk2016: 9). However, researchers have pointed out that comparisons with previous generations fail to capture the plethora of ‘non-institutional’ forms of participation used by young people to participate in contemporary democracy (García-Albacete Reference García-Albacete2014; Mirra and García Reference Mirra and García2017; Pontes et al. Reference Pontes, Henn and Griffiths2019). Indeed, youth scholars often go beyond a narrow understanding of democracy, which encompasses mostly electoral and other institutional forms of participation. They describe young people's political engagement beyond conceptions of dutiful and rightful adult citizenship, including broader political repertoires and forms of expression such as lifestyle politics, digital activism and street protests (Bright et al. Reference Bright, Pugh, Clarke, Pickard and Bessant2018; Earl et al. Reference Earl, Maher and Elliott2017; Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni, Grasso, Giugni and Grasso2021; Pickard Reference Pickard2019, Reference Pickard2021). As a result, youth political participation consists of institutional actions – such as voting or party membership – but also non-institutional actions, such as protesting or flash mobs (Grasso Reference Grasso2016; Theocharis and Van Deth Reference Theocharis and Van Deth2018), where young people are overrepresented (Grasso Reference Grasso, Pickard and Bessant2018; Pickard and Bessant Reference Pickard and Bessant2018).

Overall, arguments that stress young people's democratic disaffection suggest that attitudes of opposition to democracy should be stronger among young individuals, leading to greater demobilization among young milieus. Moreover, if we are witnessing a potential process of democratic deconsolidation and generalized democratic disaffection among young adults, we should expect the association between attitudes of opposition to democracy and political participation to decrease with age. In other words, the negative impact of attitudes of opposition to democracy on the propensity to participate politically should be greater among young people, and should hold across forms of political participation. Regarding the association between age and attitudes of opposition to democracy on political mobilization, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3A: The negative impact of opposition to democracy is prevalent and stronger for younger than for older age groups.

Hypothesis 3B: The negative impact of opposition to democracy significantly decreases mobilization by younger relative to older age groups – both for voting and protesting.

Data

In the framework of a large EU-funded collaborative research project, we use a survey including booster samples of young people in nine European countries: namely France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.Footnote 3 These data have two unique advantages. First, to the best of our knowledge, it is the largest reliable, comparative European survey on young people. While the dataset is made up of at least 1,000 general population cases in each country, it includes two booster samples of young people aged 18–24 and 25–34; each booster sample consists of at least 1,000 additional respondents for every country. In total, 27,446 people were interviewed between April and December 2018.Footnote 4 A specialized polling agency collected the data ad hoc through administered online panels using balanced country quotas in terms of sex, age, region and education level to match national population statistics (EURYKA 2018).

Second, this survey includes a battery of five questions concerning attitudes of support for democracy, which allows us to operationalize and measure attitudes of support for/opposition to democracy. In our index, we follow a combined measurement approach with preference items based on conceptual considerations about democratic regimes, system functioning and principles (EURYKA 2018). In particular, we focus on the extent of agreement with some of the most widespread criticisms towards and considerations about different aspects of democracy, which we measure through five-point Likert scales. These are: democracies being indecisive, being disorderly, being economically inefficient, whether democracies are better than alternative regimes, and whether the equal representation principle (one person, one vote) is desirable (see the Supplementary Material: Appendix 1; see also Figures A1–4, Appendix 2).Footnote 5

Siding with Easton (Reference Easton1975), considering that ‘democracies’ are ‘indecisive’, ‘aren't good at maintaining order’ or are a type of regime in which ‘the economic system runs badly’ clearly transcends the evaluations of the incumbents, and are thus not a specific form of political support. As discussed earlier, our indicators tap into Brandon Gorman et al.'s (Reference Gorman, Naqvi and Kurzman2018) interrelated considerations of opposition to democracy: empirically, the items about economic efficiency and decisiveness connect preference for democracy to economic and social evaluations (developmentalist considerations); the desirability of maintaining order and living in a democracy rather than in another system focuses on societal values (culturalist considerations); and equality of minorities refers to the acceptance/rejection of egalitarian elements in a democracy (elitist considerations). Moreover, as the level of correlation between the five items is moderate (0.17 < Pearson's r < 0.56, based on a polychoric correlation matrix), we carry out a Principal Component Analysis, which offers a solution where one single component has an Eigenvalue above the 1.00 threshold (Eigenvalue = 2.30), accounting for 46% of the total variation. The internal consistency of the weighted summated scale falls within reasonable standards (Cronbach's alpha = 0.69), with Poles displaying slightly more opposition to democracy than people in other countries, and Swedes being located at the other end of the spectrum (see Supplementary Material, Figures A2–3, Appendix 2).

To test the first two hypotheses, we use a categorical age group variable as an indicator that considers age differences inside the youth sample, while allowing comparison between young people against the rest of the population. This variable splits the sample according to the data structure: (1) young respondents aged 18–24 (n = 10,013), (2) young respondents aged 25–34 (n = 10,603), and (3) respondents aged 35 years or older (n = 6,820).

In addition, to test Hypotheses 3A and 3B, we operationalize two dependent variables related to political behaviour. Firstly, an electoral turnout variable captures whether the respondent voted in the last national election (1 = yes, 0 = no).Footnote 6 Secondly, we generate a dummy variable that measures whether respondents have ‘attended a demonstration, march or rally in the past 12 months’ (1 = yes, 0 = no). On average 76.4% of our sample turned out to vote in the last national election and 11.1% protested in the past 12 months. However, we observe relevant differences across countries (Figure 1). While more than 83% of German, Italian and Swedish people declared in 2018 that they had turned out to vote, Swiss people voted to a much lower extent (61.1%). Regarding the protest behaviour variable, demonstrators increase dramatically if we restrict our focus to South European countries, especially Greece (15.7%) and Spain (28%).

Figure 1. Probability of Turning Out to Vote and Demonstrating, by Country

Building on previous research analysing covariates of political participation, we consider several control variables to strengthen our arguments against alternative explanations. Among these variables, we include three different groups: sociodemographics and grievances; social capital; and political attitudes (Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Van Sickle and Weldon2010; Schussman and Soule Reference Schussman and Soule2005; Vráblíková Reference Vráblíková2014). Table A1 in the Supplementary Material summarizes the descriptive statistics of all the variables included in the models (see also Appendix 1).

It is well known that increased resources are associated with increased prospects for citizen engagement in political action. Certain sociodemographic characteristics and personal attributes, such as sex, migration background, social class, the urban/rural area of residence or education, increase the costs and risks associated with political participation (McAdam Reference McAdam1986; Schussman and Soule Reference Schussman and Soule2005; Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Two three-point interval-level variables measure the highest level of education attained by the respondents (primary, secondary or tertiary education) and their social class (upper, middle or lower/working class). Two dummy variables capture sex assigned at birth (1 = female, 0 = male) and migration status (1 = country citizen, 0 = not a country citizen). Finally, an ordinal variable measures the degree of rurality of the area in which the respondent lives (1 = big city; 2 = suburbs or outskirts of a big city; 3 = town or small city; 4 = country village; 5 = farm or home in the countryside). In terms of grievances, we include and control for whether the respondents have ‘experienced real financial difficulties (e.g. could not afford food, rent, electricity) in the past 12 months’ (1 = yes; 0 = no) – this measurement is also a proxy for material and existential insecurity (see Inglehart Reference Inglehart2016).

To control for the role that social capital and political attitudes might have for political participation, we consider network embeddedness and social disposition covariates (Norris Reference Norris2011; Schussman and Soule Reference Schussman and Soule2005; Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Specifically, we consider the frequency with which respondents meet friends who do not live in their household (four-point ordinal scale; 1 = less than once a month; 2 = once or twice a month; 3 = every week; 4 = almost every day) and how often they discuss politics with friends (11-point scale; 0 = never, 10 = frequently). Previous research has also shown that ideological self-positioning is a key predictor to explain the willingness to engage in protesting behaviour or other forms of political participation (Hutter and Kriesi Reference Hutter, Kriesi, van Stekelenburg, Roggeband and Klandermans2013; Torcal et al. Reference Torcal, Rodon and Hierro2016), hence we also include a scale variable ranging from 0 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right), measuring participants' left–right ideological self-positioning. Importantly, to account for the country differences in the average of the dependent variable we also include country-fixed effects in our statistical analyses.

Finally, in addition to country-fixed effects and for robustness checks, we also include two contextual variables for multilevel random intercepts and slopes models. First, contextual economic variation is measured through real GDP per capita (2018), adjusted for cross-country differences in cost of living and inflation. Second, we use the EURYKA (2018) policy analysis dataset to control for variation related to civic culture. The 2018 Civic Policy Index measures the extent to which countries' existing policies encourage or discourage social inclusion and the political involvement of young people.

Empirical results and discussion

Attitudes of opposition to democracy across groups

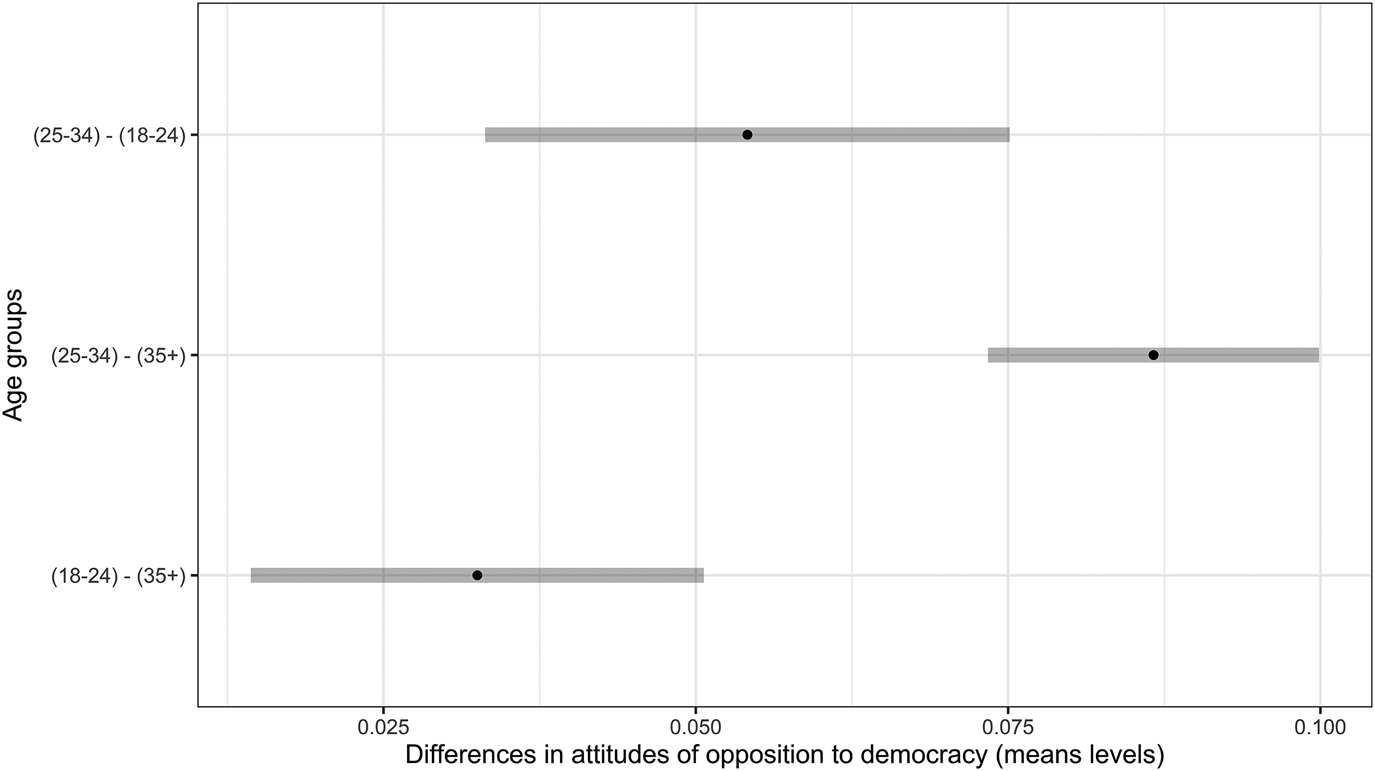

To explore whether there are significant differences in attitudes of opposition to democracy between the three age groups (18–24 years old, 25–34 years old and 35+ years old), we conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc multiple means comparison using a Tukey test. With respect to average score values on attitudes of opposition to democracy across age groups, we observe slight differences: 18–24 years: mean 1.17 (0.32 sd); 25–34 years: mean 1.21 (0.33 sd); and 35+ years: mean 1.14 (0.34 sd). Indeed, Figure 2 shows a similar distribution across the three groups' opposition to democracy.

Figure 2. Distribution of Opposition to Democracy across Age Groups (n = 27,446)

The results of the ANOVA test confirm that there is a significant difference in the overall effect between the age groups in attitudes of opposition to democracy (F (2, 27,427) = 132.91, p < 0.000, generalized η 2 = 0.01), after including the country, sociodemographic and personal constraint control variables. The Tukey's range test showed that, relative to the younger age groups, the 35+ age group has lower levels of opposition to democracy. Accordingly, the estimated contrasts are stronger between groups ([35+]–[25–34] = −0.087 (0.006 sd, p < 0.0001)) than between groups ([35+]–[18–24] = −0.033 (0.008 sd, p < 0.0001)). At a first glance, attitudes of opposition to democracy seem to be stronger among the younger generations than among those aged 35 and older (Supplementary Material, Table A2, Appendix 2). However, young individuals do not form a monolithic category. The estimated contrasts revealed that the relationship (opposition to democracy–age) is complex and nuanced within groups of young people.

Indeed, attitudes of opposition to democracy vary significantly between the two young age groups, showing a positive differential in favour of the 25–34 age group relative to the younger subset ([25–34]–[18–24] = 0.054 (0.009 sd, p < 0.0001)). Likewise, the estimated contrasts are stronger for those aged 35+ when compared with the second age-group subset, yet much lower relative to the youngest subset. In other words, relative to both the 35+ and 18–24 age groups, attitudes of opposition to democracy are stronger among the 25–34 age group (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Age Group Means Comparisons and Differences in Attitudes of Opposition to Democracy (n = 27,446)

These findings support Hypothesis 1, with age-group levels in attitudes of opposition to democracy being greater among the younger age groups than among the older age group (35+ year-olds). Yet, these differences vary significantly across young groups as well (18–24 against 25–34 year-olds), with people aged 25–34 being more opposed to democracy than those aged 18–24. These results also conform to Hypothesis 2, in line with recent research that advocates abandoning the idea of ‘youth’ as a homogeneous social category (Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni, Grasso, Giugni and Grasso2021; Grasso Reference Grasso, Pickard and Bessant2018; Holecz et al. Reference Holecz, Fernández and Giugni2021; Pickard and Bessant Reference Pickard and Bessant2018).

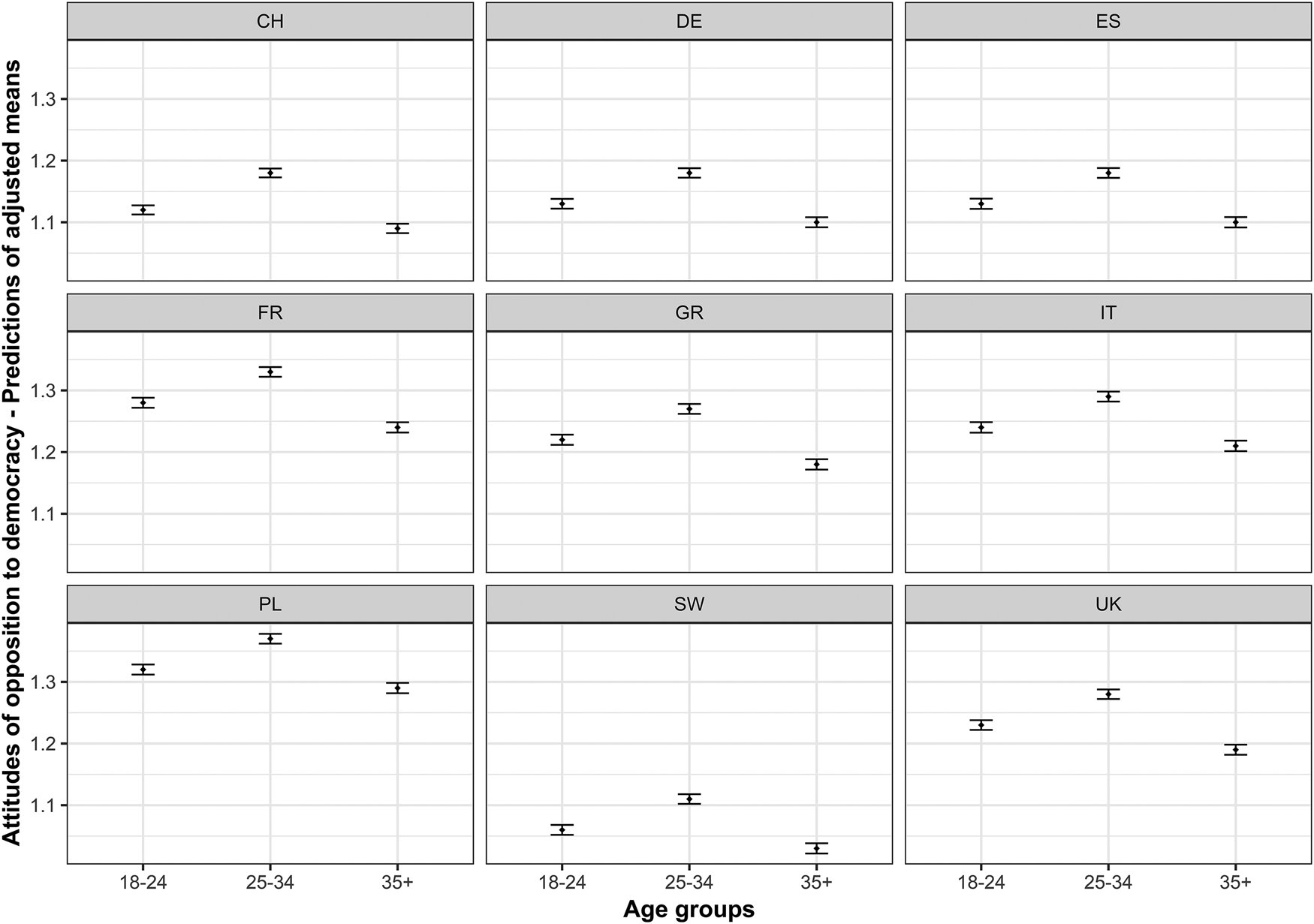

After controlling for inequality-engendering factors at the individual level, we show that age-group covariates also explained significant variation in attitudes towards democracy among young people. Attitudes of opposition to democracy are stronger and more prevalent among young people aged 25–34 than among young people aged 18–24, advancing a non-linear negative association between attitudes of opposition to democracy and age.Footnote 7 Moreover, people aged 25–34 are more likely to have strong attitudes about ‘opposition to democracy’ than other age groups for every European country we surveyed (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Estimated and Adjusted Means of Opposition to Democracy, by Age Groups across Countries

By investigating differences in attitudes of opposition to democracy both within subsets of young people and against older age groups, we posit that the opportunities and constraints experienced in a broad sociopolitical context are essential aspects for understanding young people's overall support for democracy and political socialization. Specifically, our results show that those who were in their teens and early 20s in the depths of the Great Recession (2010–2013) were likely to hold greater attitudes of opposition to democracy by the time the survey was fielded. Hence, the broader political context and specifically moments of social unrest are factors that influence young people's attitudes to democracy and perceptions of the political environment. Moreover, far from being an increasingly disaffected group of citizens, the youngest subset of people shows greater attitudinal support for democratic values than older (but still young) people – and possibly a higher potential for increased mobilization, as we shall explore next.

Opposition to democracy, age groups and political mobilization

Following arguments that youth democratic disaffection leads to potential democratic deconsolidation, we now test whether attitudes of opposition to democracy decrease political mobilization – especially among young people. Thus, opposition to democracy would lead to political disengagement as well as age, moderating the association between attitudes of opposition to democracy with political mobilization (considering both electoral and protest behaviour).

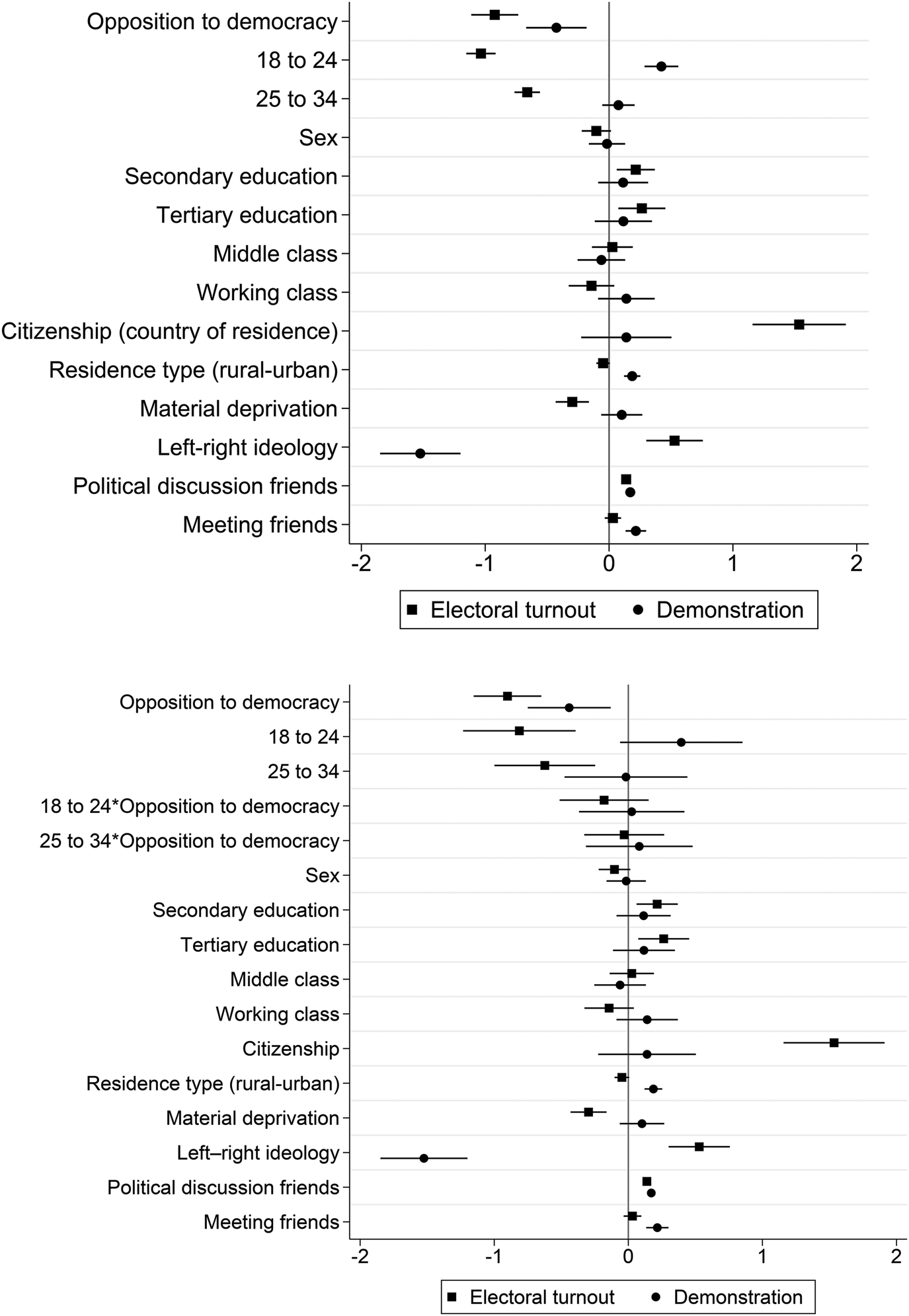

To test our Hypothesis 3, we include age group, attitudes of opposition to democracy and their interaction as key predictors in a multivariate logistic regression model with country fixed effects and controls (Supplementary Material, Table A6, Appendix 2). Overall, our results show a negative and statistically significant association between attitudes of opposition to democracy and both protesting and voting behaviour (see Supplementary Material, Figure A6, Appendix 2).

Our general results also follow the literature's findings on the different forms of political engagement among age groups, meaning that, depending on their age group, individuals display different propensities to engage in voting or protesting behaviours. In terms of electoral turnout, we observe a negative and statistically significant association with age: compared to older age groups (35+ years old), the two younger subsets (18–24 and 25–34 years old) are less likely to engage in electoral politics. Yet, concerning political engagement in protests, we find a positive and statistically significant association with age. However, only the youngest subset of individuals (aged 18–24) is much more likely to participate in protests than older age groups (35+), which is consistent with arguments on biographical availability – see Figure 5. Overall, young people (aged 18–24 and 25–34) turn out to vote to a lesser extent than older people (aged 35+) do, while younger people protest more.

Figure 5. Plots of Coefficients from Logit Regression (Log Odds). Top: Without Moderation Term. Bottom: With Moderation Term

Notes: For top plot, see Supplementary Material, Table A6, Models 3 and 8. Dependent variables: electoral turnout and demonstration. 95% C.I. (n = 27,446). For bottom plot, see Supplementary Material, Table A6, Models 5 and 10. Dependent variables: electoral turnout and demonstration. 95% C.I. (n = 27,446).

We show that attitudes of opposition to democracy decrease the likelihood of political engagement across all age subsets. However, there is no statistically significant interaction between age and opposition to democracy on political mobilization. Based on our empirical evidence, we cannot corroborate Hypothesis 3A; the association of age with attitudes of opposition to democracy on political mobilization is neither prevalent nor stronger for younger age groups than for older ones. Indeed, relative to older groups (35+), young age groups (18–24 and 25–34) are more likely to show opposition to democracy, but these do not lead to greater demobilization among young people (group mean comparison results are reported in the Supplementary Material, Tables A3–4).

Additionally, Figure 6 empirically shows that the association between age and attitudes of opposition to democracy is statistically non-significant for both electoral and protest forms of action. Therefore, we cannot verify Hypothesis 3B. The marginal effects illustrate how the predicted values of attitudes of opposition to democracy are negatively correlated with electoral turnout and demonstration – no matter the age group. This relationship is constant across age groups, with slope differences being negligible. Our results are robust after controlling for macro-level variation (Supplementary Material, Tables A7–8). Our eight multilevel logistic models with random slopes accounting for country–country variation in GDP and in the Civic Policy Index corroborate that the interaction terms between age group and attitudes of opposition to democracy are not significant and provide a poorer-fitting model than parsimonious models with no interaction. Importantly, all models corroborate the results of the fixed-effects regression and point to the role of small age subsets' attitudinal variation on political engagement (both in electoral and protest terms).

Figure 6. Predicted Probabilities of Electoral Turnout (top) and Demonstrating (bottom) as a Function of Attitudes of Opposition to Democracy and Age Groups

Notes: 95% C.I. (n = 27,446).

To further assess the statistical association between age and opposition to democracy on voting and protest, we implement a post hoc analysis on the slope trends for each factor level. While controlling for covariates, our fitted models estimate a separate linear trend by age group and for each form of political action relative to attitudes of opposition to democracy. As Figure 7 shows, the contrasts – that is, the differentials between the slopes – are not significant for our six pairwise comparisons: three age groups by two action repertoires (electoral and protest). In other words, people who have concerns regarding the democratic regime, system functioning and principles are less politically active, regardless of age group or action repertoire.

Figure 7. Estimated Statistical Differences of Electoral Turnout (top) and Demonstrating (bottom) as a Function of Attitudes of Opposition to Democracy Relative to Each Age Group

Notes: 95% C.I. (n = 27,446).

All in all, contrary to the ‘democratic deconsolidation’ argument and challenging the scepticism about youth political engagement, our results show that attitudes of opposition to democracy do not translate into less mobilization among young people relative to older citizens. In line with the youth participation ‘paradox’, our findings suggest that young people's critical views on democracy rarely turn into democratic disengagement, at least not more so than for older adults. The broader repertoire of youth political participation provides an interesting challenge to supporters of the youth democratic disaffection argument. At the very least, our findings caution against strong presumptive discourses on youth democratic disaffection, democratic disillusionment and disengagement.

Finally, some of the control variables confirm established tenets of the political participation literature, but also help to qualify some previous findings (see Figure 4). With regards to the set of sociodemographic and personal constraints covariates, the results show that migrant/citizen status is negatively correlated with electoral participation, and living in an urban area increases the likelihood of protest, while gender and class are not associated with the propensity to turn out to vote or protest. Also, the results validate that higher education attainment is positively correlated with voting and that material deprivation has a negative impact on electoral participation. As expected, we find a positive association between network embeddedness and social disposition variables on political participation: discussing politics with friends increases the likelihood of protesting and voting. Furthermore, as expected, ideology shows a differentiated association with the forms of political participation: right-wing people are more likely to vote but left-wing people are more willing to engage in protest activities. Finally, meeting often with friends increases the chances of protesting, but it does not influence electoral turnout.

Conclusion

Young people are deeply involved in the ongoing transformations of our current democracies. This article contributes to the growing body of scholarship seeking to understand the terms in which young people participate in contemporary democratic life. Towards this end, it is fundamental to understand the differences characterizing young people, with respect to their background, their attitudes and their behaviour, the way they interact with each other and their impact on democratic life. In doing so, we have sought to find ‘youth-specific explanations’ for the participation paradox with a fine-tuned analysis of their democratic views and activities (Weiss Reference Weiss2020: 9).

Young people stand out as critical actors engaging with democracy in ways that are poorly captured through standard liberal democratic lenses. Our overarching findings complement the previous literature by directly challenging the democratic scepticism argument depicting young people as a monolithic category and more democratically disaffected compared to their older counterparts. The results show that the youngest group of adults are likely as supportive of/opposed to liberal democracy as older groups. Differences emerge in the chosen forms of mobilization. However, relative to age, the impact of attitudes of opposition to democracy on political mobilization – protesting and electoral behaviour – is not greater or different from the rest of the population.

While young people vote less than older people, their critical views about democracy do not usually transform into democratic disaffection – or apathy, at least not to a greater extent than for older adults. Therefore, a lack of diffuse support undermines democratic life – both in its attitudinal and behavioural dimensions – for all age groups and is by no means a distinctive feature of youth.

Rejecting the view of young people as a homogeneous and disaffected group of citizens, this article shows that people who were socialized politically under the Great Recession are the most opposed to democracy across European countries nowadays. This presents a wake-up call: the way the recession was handled at the national and supra-national levels, and the way costs and austerity policies were distributed, were likely to make citizens sceptical and critical of democratic principles, values and system functioning. At the same time, it is encouraging that the youngest subset of people seems to be more committed to democracy than older young citizens, as this might embolden a potential for democratic regeneration.

Our study is not without limitations: future research should try to extend regional focus, political repertoires of action and leverage other types of evidence (e.g. experimental) to build causal claims. Although we were able to offer a more defined picture of internal differences among young people and started to explore how their attitudes and behaviours interact, work remains to be done to investigate some crucial aspects in the relationship between youth and democracy that our investigation could not cover. For instance, how inequalities and political ideologies affect young people's approach to democracy remains largely unexplored. Finally, further work is also needed to ascertain empirically to what extent young people are bearers of new democratic ideas and practices.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2023.16.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article have been presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association (virtual, 2021), the European Sociological Association conference (virtual, 2021) and a seminar at TU Chemnitz (virtual, 2022). We are grateful to participants in these events for helpful feedback. We also thank the editors of Government and Opposition and three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. Finally, we are also grateful to Lorenzo Bosi, Marco Giugni and Maria Grasso for their help and support throughout.

Financial support

This work has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No. 727025. MP also acknowledges support from the Conex-Plus Marie Curie framework (G.A. No. 801538) and the Ramón y Cajal grant (G.A. No. RYC2021-032179-I), which is funded by the MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Union's ‘NextGenerationEU’/PRTR.