Introduction

This investigation took place in a mixed selective state grammar school in the northwest of England for ages 11–18. The school roll was 1,249 in 2022, with the sixth form representing approximately 28% of pupils. This same year, the school was rated ‘good’ by Ofsted, and it was noted that teaching staff and leaders have high expectations of what pupils can achieve, but lack of emphasis on reading was detailed as a weakness. In 2023, 58% of all pupils at GCSE achieved grades 9/8, with 8 being the average grade. In the sixth form, 86.6% of all grades were A*-B. The school caters for a range of socio-economic backgrounds, but due to the selective nature of the school, pupils are highly self-motivated and value their education which is reflected in high attendance and the lack of disruption to classes by poor behaviour.

Pupils begin learning Latin in Year 8 and select their GCSE options in Year 9. This means that all teaching from Year 9 onwards focuses on the GCSE syllabus. The school offers Latin, which must be taken in tandem with either Spanish or French, but Classical Civilisation is not offered. In the sixth form, Latin is likewise offered and may be taken without French or Spanish, but Classical Civilisation is not. Latin is viewed to be more challenging for pupils, but lack of subject specialist staff also contributes to the decision only to offer Latin.

Since 2019, 60% of the pupils in the A Level Latin cohorts have achieved A/A* grades. Latin is consistently the highest performing subject in the school. It is within this context that I undertook a structured investigation into the effect of vocabulary retrieval in a Year 12 Latin classroom.

Literature review

Research into formative assessment formed the basis of this investigation. The seminal study Inside the Black Box (Black and Wiliam, Reference Black and Wiliam1998) found that ‘significant learning gains’ are possible through the implementation of formative assessment whereby the ‘effect size’ on performance by introducing learning innovations for adaptive teaching was between 0.4–0.7 (Black and Wiliam, Reference Black and Wiliam1998, 4). This can be quantified into a difference of between 1–2 grades at GCSE. However, poor examples of practice, such as lack of guidance in feedback about how to improve and techniques that encourage ‘rote and superficial learning’, had non-positive long-term effects. Subsequent research has provided guidance for incorporating formative assessment into class time, such as beginning each lesson with a short review task, further weekly and monthly review, and asking a plenitude of questions that require every pupil to respond (Rosenshine, Reference Rosenshine2012, 12).

In the Latin classroom that provided the context for my study, Rosenshine's (Reference Rosenshine2012) principles were thoroughly embedded into the lesson routines, with pupils across all year groups trained to expect an oral review starter at the beginning of each lesson, and two weekly low-stakes tests. As outlined by Rosenshine (Reference Rosenshine2012), I observed that the regularity and consistency of these formative assessments enabled vocabulary and grammar principles to be retained long-term and helped to connect ideas across topics (Rosenshine, Reference Rosenshine2012, 19). For example, after reviewing the perfect passive, pupils could see patterns emerging in a lesson on the pluperfect passive. Well-connected ideas developed student understanding of new topics, and allowed pupils to perform consistently even when formative assessment was performed ad hoc, for example through cold-calling (e.g. ‘and how did we form the pluperfect active?’), or an unanticipated plenary at the end of a lesson.

Partly in response to Black and Wiliam (Reference Black and Wiliam1998) and Rosenshine (Reference Rosenshine2012), specific studies have been conducted in the field of Modern Languages teaching to make formative assessment impactful, meaningful, and its effect long-lasting (Conti and Smith, Reference Conti and Smith2021, 83). As course books only provide roughly half of the necessary input for language learning (Nation, 2013, 46), it is important to provide pupils with an opportunity for focusing on learning high-frequency words via production of the TL and targeted practice. For example, open questions with sentence starters such as ‘do you agree…’ or ‘how can be improve X…’ were found to result in longer answers being given than previously, more pupils self-selecting to answer, and a broader range of answers (Black and Jones, Reference Black and Jones2006, 6). Metacognitive reflection was also shown to produce desirable outcomes, particularly peer and self-assessment which provided pupils with a rationale for the correct answers by allowing them to focus on criteria and assimilate mark schemes into their thinking (Black and Jones, Reference Black and Jones2006, 8–9). While effective in the short-term, these outcomes took place at the level of classwork and do not reflect the effect of performance in long-term summative assessment. More recent studies have gone further.

The 2014 edited volume Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Roediger and McDaniel2014) focuses on effortful retrieval practice through regular low-stakes quizzing (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Roediger and McDaniel2014, 15–16) to improve knowledge retention. The frequency and variation of such testing will reduce the phenomena of pre-exam ‘cramming’ (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Roediger and McDaniel2014, 63). Further, problem solving, and ‘desirable difficulty’ (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Roediger and McDaniel2014, 90–92) can help pupils to deep process information. I have used this in my own classrooms when teaching the difference between the use of ne in fearing clauses and purposes clauses. Engagement with the question of how ne is used differently in each construction was high and pupils guided themselves towards the answer. Subsequently, no pupils confused the constructions in the plenary where they were asked to identify positive and negative constructions in fearing clauses. Carefully selecting problems for pupils to solve before giving them the answer has the added benefit of being practical to implement in the classroom through peer-discussion and questioning.

Other examples of good practice are repeated, specific retrieval with multiple-choice questions (MCQs) being an effective way to make inferences about a pupil's understanding (Christodoulou and Wiliam, Reference Christodoulou and Wiliam2017, 164–165). In Making Good Progress: The Future of Assessment for Learning Christodoulou and Wiliam take a reparative approach to the much-maligned use of MCQs. In their example, an MCQ about totalitarianism under Hitler and Stalin that allowed pupils to choose between four simple options allowed teachers to highlight student misunderstanding quickly, based on incorrect answers. While MCQs should not replace extended written assessment, they are an efficient tool for quick and responsive adaptive teaching due to their low time cost and the ability to easily observe results.

MCQs for low stakes testing could be usefully applied to Latin morphology tests, for example, instead of giving pupils the infinitive of a verb and asking them simply to translate it into English, the test could consist of a different form, for example the future participle (e.g., amaturus). Pupils would then select the correct translations (e.g., a. about to love, b. worthy of love, c. having been loved, d. being loving), allowing teachers to quickly identify errors in understanding words in context rather than only testing superficial memorisation of meanings, a problem that particularly effects the teaching of Classical languages (Hunt, Reference Hunt2022, 14). If a student answered c or d, for example, teachers may easily infer that the student has forgotten that future participles cannot be passive. This mistake can be easily addressed by immediate feedback, whereas a mistranslation of amare would only demonstrate a retrieval error. The same could be done for nouns, for example instead of asking pupils to translate rex, regis as ‘king’, use regum providing a. of the king, b. of the kings, c. by the king, d. for the kings. This would allow teachers to notice case and number errors.

While historically there has been a cordon sanitaire between Modern Languages pedagogy and the teaching of Classical languages, recent research has sought to bridge this gap and employ the techniques used in Modern Languages teaching (Patrick, Reference Patrick2015, 108). Traditionally, formative assessment in Latin has centred around identifying and explaining grammar constructions. However, through targeted teaching of vocabulary that focuses on comprehension rather than grammar drills, such as those used in French and Spanish, Latin is made more understandable to pupils as rendering syntax becomes meaning-focused. This helps to overcome barriers experienced by other learners of a second language, such as the phonological loop (how long it takes to pronounce something), which have an impact on cognitive load (Conti and Smith, Reference Conti and Smith2021, 83). Not knowing how to pronounce something creates extraneous cognitive load as too much time is spent problem-solving over new schema formation (Shibli and West, Reference Shibli and West2018). Pre-teaching vocabulary would therefore help to scaffold the higher-level translation task and allow pupils to work through language above their level as per Bailey's desirable targets (Bailey, Reference Bailey, Lloyd and Hunt2021, 33) but with independence (Shibli and West, Reference Shibli and West2018; ‘without necessarily needing the help of their teacher for each stage’).

There is comparatively little research in the field of classics for implementing such techniques in the classroom. Classical languages present their own set of challenges that mean the results of the above studies are not always valid for classical languages. For example, Latin (and Ancient Greek) are non-spoken languages, and all summative assessment is therefore either reading and translating into English, or composing into Latin from English, with a primary focus on the former (Hunt, Reference Hunt2022). Historically, the key approaches to teaching Latin are implicit learning as exemplified by the Cambridge Latin Course, where continuous reading leads to mastery, or the more traditional method of grammar drills (Gay, Reference Gay and Morwood2003, 76). In my context school, the grammar approach has been predominantly adopted due to the time constraints of Latin only being introduced on a staggered basis in Year 8.

For pupils facing an unseen translation for the first time, the ‘fear factor’ has been identified as a barrier to learning (Gall, Reference Gall2020, 11) as unfamiliar syntax prevents recall of meaning, even when confronted with familiar vocabulary. Embedded readings (Gall, Reference Gall2020, 13–14), where the teacher provides three or more scaffolded versions of the text (e.g., translations with only missing words) did help improve pupils' confidence in translating. However, this process is extremely time-consuming for the teacher. In Gall's (Reference Gall2020) study, the teacher replaced all oratio obliqua with direct speech, before presenting the target text. For focused unseen practice done on a regular basis (i.e., weekly) this may be unfeasible as a pre-teaching method. The method was deemed most suitable for set texts, where frequent, graded encounters with the text aided memory pertinent to the exam. Gall (Reference Gall2020) therefore concludes regarding unseens: ‘I think I should have placed more focus on memorising the key vocabulary, which was glossed in each version, as both pupils consistently relied on the glosses’ (Gall, Reference Gall2020, 17–18). This caused me to think about a method of formative assessment that would support implicit teaching of vocabulary for approaching an unseen, with a greater economy of time for the teacher than Gall (Reference Gall2020) achieved with embedded readings.

To anticipate which words would be most lexically challenging for pupils, I considered the following factors: word length, word frequency, lexical sophistication, lexical density, and lexical variation (Gruber-Miller and Mulligan, Reference Gruber-Miller and Mulligan2022, 83–84). Words longer than six letters, and with a density falling short of 59% were the most lexically challenging. This provides a quantitative approach for identifying difficult vocabulary, rather than relying on anecdotal intuition and can be implemented using easy to access word frequency tools such as Perseus. Nonetheless, the phonological similarity effect should also be considered for commonly confused words (Warwicker, Reference Warwicker2019, 4); thus teachers should not rely solely on the datasets of Gruber-Miller and Mulligan (Reference Gruber-Miller and Mulligan2022). Finally, without knowing 95–98% of words in the text, meaning will be significantly impeded therefore vocabulary acquisition is a priority for learning.

Three desirable outcomes have been identified as targets for adaptive teaching in Latin (Bailey, Reference Bailey, Lloyd and Hunt2021, 45): (a) ability to sight-read familiar texts, (b) ability to read specific target texts, and (c) ability to interact and respond to texts above one's reading level. A particularly effective method for reaching these goals is ‘to identify in advance the elements of the text likely to present the greatest difficulty’, particularly morphology (Bailey, Reference Bailey, Lloyd and Hunt2021, 33). The teacher should provide a ‘focused input’ task (Bailey, Reference Bailey, Lloyd and Hunt2021, 35–36) as a form of formative assessment to address these elements of the text and make target morphology learning more focused (fewer extraneous variables) and more varied (in several contexts).

Furthermore, a focus on completing translations in classical languages pedagogy leaves little time for reflection on the process of translation, which has been shown to increase accuracy and analytical skills (Praet and Verhelst, Reference Praet and Verhelst2020, 31–33). Leaving time after the completion of a translation for comparing answers, evaluating the best renderings, and systematic feedback as a class allows for productive reflection that not only prepares pupils for independence but reviews the material to embed understanding (Rosenshine, Reference Rosenshine2012, 13).

Pupils reported that they used the app memrise to learn the vocabulary list. One study has investigated the benefits of using memrise in classical language learning and suggests that it has a positive impact on intrinsic motivation, meta-learning, and improves performance on vocabulary tests (Walker, Reference Walker2015, 19). Computer-aided learning is often reported as the main method of study for pupils and has the benefit of supporting rote learning, though surveys of pupils feelings towards apps to learn vocabulary show that the extrinsic motivation provided by the app is not enough to keep pupils practising regularly when there is no scheduled test in school (Walker, Reference Walker2015, 9). Pupils in the context school reported using memrise in pre-A Level years, but the sixth form had begun using anki as they preferred the control and personalisation made possible by the ankiweb software.

The main themes that emerge from this literature review are that formative assessment that gathers diagnostic data from the whole class is essential for positive learning outcomes (Black and Wiliam, Reference Black and Wiliam1998; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Roediger and McDaniel2014; Conti and Smith, Reference Conti and Smith2021; Nation, 2013; Rosenshine, Reference Rosenshine2012); Modern Languages research has the potential to expand the range of pedagogical techniques in the teaching of classical languages (Bailey, Reference Bailey, Lloyd and Hunt2021; Christodoulou and Wiliam, Reference Christodoulou and Wiliam2017; Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, Reference Hunt2022; Patrick, Reference Patrick2015); and finally, Latin has an implicit learning problem whereby pupils are not exposed to uses of the language in a range of relatable and adaptable contexts (Gall, Reference Gall2020; Gruber-Miller and Mulligan, Reference Gruber-Miller and Mulligan2022; Praet and Verhelst, Reference Praet and Verhelst2020). My study therefore aims to address the problems and issues identified above and ensure that my language learning pedagogy was informed by valid research reflected in practice.

Observations

The following observations were carried out in a Year 12 AS Level class consisting of eight pupils. The class composition was three boys, and five girls. There were no SEND pupils, and two pupils were EAL. Five out of eight of the pupils were predicted an A*, and the remaining three were predicted an A grade.

Prior to conducting the investigation, I had taught the class one lesson a week for an hour over the course of six weeks. Each week, the class was asked to translate an unseen passage of approximately 14 lines from a set textbook (Carter, Reference Carter2016). I observed that while some pupils were able to finish the translation within 45 minutes (the final 10–15 minutes of the class were spent on group marking and class discussion of difficult grammar items), most of the pupils struggled to finish the passage and were distracted by unfamiliar vocabulary and the inability to recognise instances of hyperbaton. Unfamiliar vocabulary appeared to be having a negative impact on the pace of translation (Nation, 2013, 195). Therefore, I decided to conduct a series of observations using retrieval practice as a method of formative assessment that would pre-teach unfamiliar vocabulary.

During the classes I aimed to observe:

How much of the translation pupils finished.

The extent to which pupils needed to ask for vocabulary help and rely on dictionaries.

To what extent pupils found the formative assessment useful for completing the unseen. E.g., after learning the principal parts of do (dare, dedi, datus), could pupils recognise the pluperfect form (dederam) as part of the verb?

I evaluated these directives through observation of a collaborative translation task (CTT). Pupil understanding of the unseen passage was assessed in all conditions by a group translation at the end, with pupils taking it in turns to read aloud their translation, one sentence at a time. All pupils were required to contribute, achieved through randomised cold calling. Pupils were therefore not able to anticipate which sentences they would be asked to translate, allowing me to assess whether their understanding was consistent throughout the passage. The final 15 minutes of the classes were spent on teacher-led discussion of common errors, guiding pupils through corrections.

Methodology

With a one-hour weekly time slot to guide the class through an unseen, I decided to use a CTT for the translation of the unseen passages (Kargar and Ahmadi, Reference Kargar and Ahmadi2023). My reasons for this were linked closely to the findings of the aforementioned study; working in a small group (two-three) allowed pupils to engage in topic-based discussions which serve to bring attention to the target languages forms (Kargar and Ahmadi, Reference Kargar and Ahmadi2023, 88). These aims accord with the language acquisition principle that instruction needs to account for the fact that translation has a subjective aspect (Conti and Smith, Reference Conti and Smith2021, 205). The study further argued in relation to modern, spoken languages that collaborative interaction with peers helped to imbue the TL with sociocultural significance which made it more meaningful to participants, and therefore aided recall (Conti and Smith, Reference Conti and Smith2021, 89). While this may not be directly relevant for Latin teaching, especially where contexts are unfamiliar (e.g., a Roman battle) the group engagement with the TL still causes pupils to consider the differences between the L1 and TL, leading to better understanding and retention.

A similar investigation to mine used collaborative learning in a Year 12 Latin classroom to assess unseen verse translation (Law, Reference Law2022, 5). The data gathered in this study through a student self-reflection questionnaire indicated that collaborative translation increased student motivation to complete the unseen translation, and increased confidence through the sharing of ideas (Law, Reference Law2022, 10). This is particularly important in Latin where the focus of learning is understanding of the syntax, rather than ability to communicate in the TL, leading to a greater demand for accuracy which some pupils may find intimidating. My study complements and extends Law's research by incorporating formative assessment into the observations to evaluate its impact on accuracy during the CTT, whereas Law measured student motivation and confidence with unseen translation taught through CTT.

Furthermore, the CTT allowed pupils to feel comfortable making mistakes with each other, and genuinely attempting every aspect of the translation before giving answers to the expert teacher. Reduction of anxiety or threat of embarrassment meant that pupils were more engaged and able to function better. A drawback of the CTT is an error contagion effect; when one particularly vocal or dominant student made an error during the task, pupils deferred to their judgement and therefore repeated the error. While the expert teacher can correct this error at the end of the class during feedback, it may lead to a misrepresentation of each student's knowledge, as the error ultimately came from one source. The teacher should listen carefully to all discussion during the CTT and keep mental notes about what individual pupils contribute in order to mitigate this effect and maintain a detailed impression of each student's level/skills.

The final test condition (pre-teaching vocabulary followed by a low-stakes quiz) follows a methodology that has been applied to Modern Languages teaching (Perez, Reference Perez2019, 7–9). Eye-tracking technology has allowed researchers to investigate how cognitive resources are allocated when confronted with a TL. Participants in the study spent less time ‘noticing’ pre-taught, familiar words, which allowed them to focus on overall grammar and meaning construction (Perez, Reference Perez2019, 17–18). While the applicability of this study to Latin is limited as the study focused on audio-visual inputs such as captioned footage, the pedagogical implications are nevertheless productive; pre-teaching vocabulary allows pupils to focus on grammar connections resulting in better learning outcomes, particularly in test-taking. Formative assessment supports this pre-teaching.

No retrieval practice

Pupils were given the passage Hiero and told they had 45 minutes to translate the passage into their books working in self-selected groups of two or three. The passage gave text-based glosses of words that are not part of the A Level vocabulary list, but pupils were not given any further vocabulary support.

Results and analysis

Four out of the eight pupils finished the passage in the timeframe, but all pupils managed to translate up to line 11 of the 14-line translation. From overhearing discussion during the CTT, I observed major vocabulary problems with the irregular past participle forms (e.g., obsesso from obsideo). This stemmed from an inability to recognise the form rather than non-recognition of meaning. Similar difficulties arose with commonly confused words (viribus mistaken for the ablative form of vir, phonological similarity effect (Nation, 2013, 459) also led ostendo to be mistaken for occido). Other difficulties were maritus, mariti (2) (mistaken for mare), potestas, potestatis (3), and non-recognition of numerals (nonaginta, quindecim, and the force of unum). Overall, pupils produced accurate translations with only minor errors. The errors were linked to a misunderstanding of vocabulary. For example, having translated ostendit as ‘he killed’, pupils made tyrannum a direct object, ‘he himself killed the tyrant’.

Retrieval practice: matching words

In this condition, the class began with a matching task on paper (see supplementary appendix 1a). Words selected for retrieval practice needed to be included on the OCR A Level vocabulary list, anticipated the vocabulary in the unseen passage, and additionally fulfilled the word length and lexical sophistication conditions of Gruber-Miller and Mulligan (Reference Gruber-Miller and Mulligan2022). The pupils were given five minutes to match the words in the list with the English meaning. Afterwards, the solution was provided on the board and pupils self-assessed. This method was chosen due to the high time constraints of the one-hour class. It was important the retrieval task did not take time away time from the CTT and allowed time for teacher-led feedback at the end of the session. Pupils were then given the passage Pacuvius Calavius (2) and told they had 45 minutes to translate the passage into their books working in the same self-selected groups. Ten minutes was planned for group translation and teacher-led feedback.

Results and analysis

The completion rate of the translation was very low in this condition. Only two pupils finished the translation in 45 minutes. The remaining six pupils completed nine lines. Therefore, I decided to give the class 55 minutes to finish the translation, in which time every student was able to complete the task. This meant feedback was not provided until the next class, six days later. The vis/vir confusion persisted, with pupils attempting to make in eius locum virum into ‘he was in a strong place’. Other difficulties were ablative absolutes that contained prepositional phrases (vocato ad consilium populo; nominibus in urnam coniectis). Pupils made the verbs indicative and transferred subjects from the main clause. e.g., ‘he was called to a meeting by the people’.

Retrieval practice: low-stakes vocabulary test

In this test condition, pre-learning was used as an instructional intervention prior to reading (Nation, 2013, 294 & 506). Pupils were instructed to learn 17 vocabulary items (see supplementary appendix 1b) as a homework task over the course of one week which anticipated the vocabulary in the unseen. Vocabulary items were selected on the same basis as the matching task. In addition, Hunt's criteria for testing vocabulary, focusing on putting words in context (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, 140) allowed meaning carried by form to be part of the assessment. I also included an MCQ section to test specific skills in noticing forms rather than memory (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Roediger and McDaniel2014). The class began with a written five-minute paper test (see supplementary appendix 1c), followed by the provision of solutions on the board and student peer-assessment. I collected these marks during the CTT. Pupils were then given the passage The Battle of Actium and instructed they had 45 minutes to translate the passage into their books working in the same self-selected groups. Ten minutes was reserved for the group translation and teacher-led feedback.

Results and analysis

The completion rate of the translation was the highest in this condition. Pupils spent eight minutes completing and peer-assessing the vocabulary test. All the pupils completed the translation within 40 minutes. 12 minutes was spent on teacher-led marking and feedback. Pupils spent no time looking up vocabulary and did not use their dictionaries to complete the exercise. Question 16 on the test required pupils to recognise the perfect passive participle inlatus. Only five pupils translated the participle correctly on the test, but all pupils correctly translated inlatae in the translation task having received feedback for their former answers (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Results of the Low-Stakes vocabulary test.

Conclusion

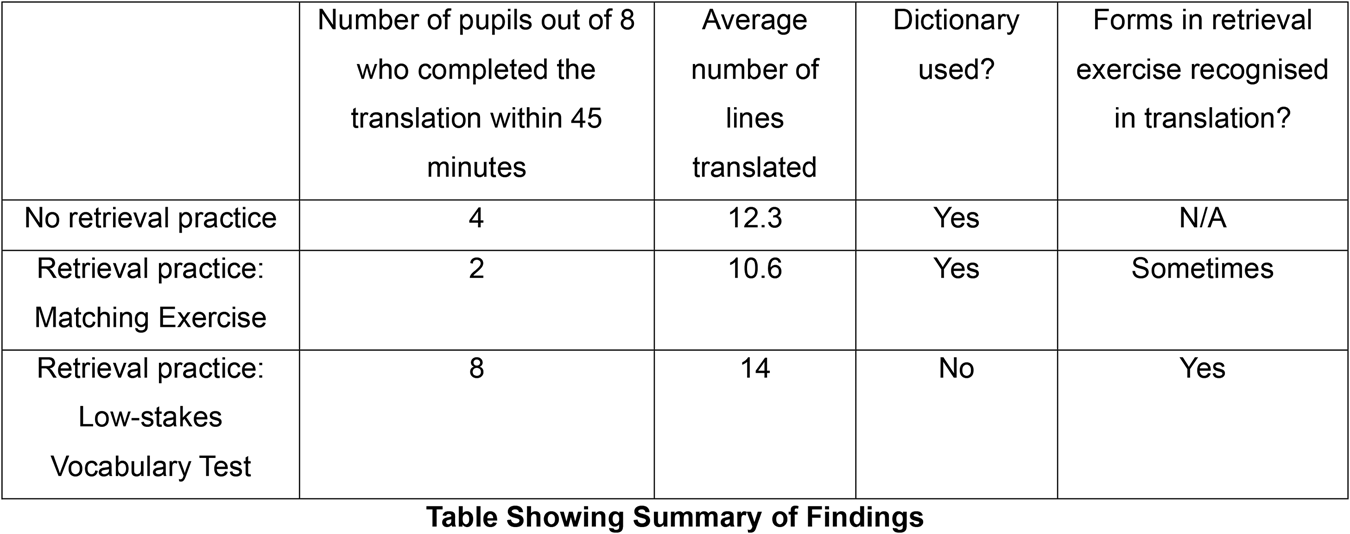

The test condition that led to the highest completion rate (within 45 minutes) was retrieval practice through a low-stakes vocabulary test which led to all pupils completing the translation in the allotted time. In the control condition, no retrieval practice, only half the pupils completed the translation. The lowest completion rate was the retrieval practice condition that used a matching exercise where only a quarter of the pupils completed the translation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Table showing summary of findings.

The matching words condition produced an accurate translation with few vocabulary errors, but pupils still relied heavily on their vocabulary list, flicking between the matching exercise and the passage to a produce a translation. Ultimately, the matching exercise does not satisfactorily solve the problem of reliance on dictionaries, as time must be taken out of the lesson for the exercise and speed of translation remains slow. Moreover, sometimes pupils struggled to connect the words they saw on the page with the form given in the matching exercise, much in the same way as pupils struggle to derive the correct form to search for in the dictionary from the form in the text.

The biggest challenge was finding a balance between economy of time spent on producing materials and conducting the assessment, while allowing ample time for the completion of the unseen. In the matching exercise condition, the fact that feedback was not able to be provided until six days later was a major drawback because pupils focused less on the Latin, reading out their translations, but struggling to remember how they had derived them from the Latin. This reduces the positive impact of teacher feedback on understanding.

Extraneous variables that may have impacted the results of this investigation are the impact of time separating the test conditions and the unrepresentative high ability cohort. Firstly, these observations were conducted over a period of four weeks. Performance in the final test condition may therefore have been affected by the fact pupils had developed their skills and become better Latinists in this time because of factors outside the retrieval practice and test conditions. To increase the validity of the experiment, I would ideally have conducted my investigation within the same week and with a wider, more diverse sample of participants.

My participants were all pupils predicted A/A*. A conscientious mindset meant that pupils spent time learning their vocabulary for the low-stakes vocabulary test, responded attentively to teacher feedback, and actively made corrections, which ensured a high performance for the final condition. A low- or mixed-ability cohort may have responded differently to the test conditions.

In conclusion, the most effective method of formative assessment for supporting pupils during unseen tasks is pre-teaching vocabulary followed by low stakes retrieval practice through a vocabulary test. Although, the preparation of vocabulary tests prior to reading unseens does represent a time-consuming burden for the teacher, I suggest that the unseens and vocabulary test be planned as part of a scheme of work well in advance. This is what is called a ‘vocabulary curriculum’ (Conti and Smith, Reference Conti and Smith2021, 209). Regular vocabulary testing should form a major part of language teaching regardless (Nation, 2013, 414). If this can be synthesised efficiently with the translation of unseens, teachers of Latin stand to make significant gains. The pre-taught vocabulary will be given context by the subsequent translation of the unseen, which will additionally provide repetition, and therefore aid long-term recall in line with research (Hunt, Reference Hunt2022, 63–65). This enhances the effectiveness of the formative assessment and the student ability to translate unseen texts.

Unseens are important pedagogic tools as they provide intensive reading instruction (Nation, 2013, 202) but they are daunting task for pupils due to the unfamiliar and unpredictable elements of the task (Bailey, Reference Bailey, Lloyd and Hunt2021, 33; Law, Reference Law2022, 4). Formative assessment should be incorporated into this activity in a way that facilitates learning for the pupils and allows them to tackle unseens with less anxiety. Replicating this investigation in a mixed-ability cohort and in other, non-selective, schools would be an excellent way to trial low-stakes vocabulary testing linked to unseen passages as a method of formative assessment which could be incorporated into a holistic and well-planned vocabulary curriculum. The sharing of such a resource would increase the effectiveness of the unseen translation, and the major role it plays in the teaching of Latin.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2058631024000692.

Author biography

Caitlin was formally an undergraduate student at the University of Cambridge, where she studied Classics on the four-year programme. She then went on to complete her MA studies at the University of Manchester in Classics and Ancient History. In 2024, she completed her PGCE at Liverpool Hope University in Classics and Latin before assuming a post as teacher of Latin and Classical Civilisation at The Grange School in Cheshire in September 2024.