Introduction

Older people with experiences of homelessness (OPEH) remain largely invisible in research, policy and practice domains though rates of this population are increasing (Crane and Warnes, Reference Crane and Warnes2010; Gonyea et al., Reference Gonyea, Mills-Dick and Bachman2010; Culhane et al., Reference Culhane, Treglia, Byrne, Metraux, Kuhn and Doran2019). OPEH include people aged 50+ who have experienced chronic/episodic homelessness or are experiencing homelessness for the first time in later life, both of which are associated with accelerated ageing that predisposes younger-aged people to geriatric health conditions normally associated with old age (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Kiely, Bharel and Mitchell2013a). For instance, OPEH are at risk of exposure, infectious disease, injury, trauma, stress and violence, and have limited options to participate in healthy lifestyles, resulting in negative health and psycho-social outcomes (Khandor and Mason, Reference Khandor and Mason2007; Homeless Link, 2014). In this study, homelessness is defined as being (a) unsheltered or absolutely homeless and living on the streets or in places not intended for human habitation; (b) emergency sheltered, including staying in homeless or family violence shelters; (c) provisionally accommodated, including living temporarily with others, couch surfing or in institutional settings; or (d) at-risk of homelessness, including living in precarious or substandard housing (Gaetz et al., Reference Gaetz, Dej, Richter and Redman2016).

Compared to younger people experiencing homelessness, and older adults in general, OPEH have more complex health and social challenges and significant unmet needs regarding access to suitable shelter/housing and support services (McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2007, Reference McDonald, Donahue, Janes, Cleghorn, David Hulchanski, Campsie, Chau, Hwang and Paradis2009; McGhie et al., Reference McGhie, Barken and Grenier2013). For example, functional impairments and chronic health conditions, including difficulties with activities of daily living (e.g. eating, bathing) and instrumental activities of daily living (e.g. financial and medication management) (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Hemati, Riley, Lee, Ponath, Tieu, Guzman and Kushel2017), as well as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosis and cognitive impairment of OPEH (Stergiopoulos and Herrmann, Reference Stergiopoulos and Herrmann2003; Garibaldi et al., Reference Garibaldi, Conde-Martel and O'Toole2005; Sudore et al., Reference Sudore, Cuervo, Tieu, Guzman, Kaplan and Kushel2018), are challenging to support in traditional shelter/housing settings (Canham et al., Reference Canham, Custodio, Mauboules, Good and Bosma2020). Yet, there are few shelter/housing options to support the diverse physical, mental and social needs of OPEH (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003). Furthermore, homelessness programming largely targets youth and people who have experienced chronic homelessness rather than OPEH (Canham et al., Reference Canham, Battersby, Fang, Wada, Barnes and Sixsmith2018), thus, there is a research, policy and practice need to identify and describe shelter/housing models and outcomes for OPEH.

‘Ageing in place’ research, policy and practice goals are based on the assumption that individuals have access to stable housing (Bigonnesse and Chaudhury, 2002; Means, Reference Means2007; Pani-Harreman et al., Reference Pani-Harreman, Bours, Zander, Kempen and van Durenin press). As limited research suggests, this can lead to OPEH feeling ‘stuck in place’ or ‘oscillating in and out of place’ rather than ageing in place (Torres-Gil and Hofland, Reference Torres-Gil, Hofland, Cisneros, Dyer-Chamberlain and Hickie2012; Burns, Reference Burns2016). Despite there being few options that address the diverse needs of OPEH or enable them to age in place (Furlotte et al., Reference Furlotte, Schwartz, Koornstra and Naster2012; McLeod and Walsh, Reference McLeod and Walsh2014; Burns, Reference Burns2016; Canham et al., Reference Canham, Battersby, Fang, Wada, Barnes and Sixsmith2018, Reference Canham, Custodio, Mauboules, Good and Bosma2020; Burns and Sussman, Reference Burns and Sussman2019), a growing body of literature recognises that innovation is required to support ageing in the right place for marginalised older adults (e.g. McGhie et al., Reference McGhie, Barken and Grenier2013; Sixsmith et al., Reference Sixsmith, Fang, Woolrych, Canham, Battersby and Sixsmith2017; Humphries and Canham, Reference Humphries and Canham2019).

Humphries and Canham (Reference Humphries and Canham2019) have developed a conceptual model of how different trajectories into homelessness (e.g. chronic/episodic versus first time in late life) give rise to unique needs and solutions to support ageing in the right place for OPEH. While this model identified three broad types of shelter/housing for OPEH (i.e. Housing First, permanent supportive housing and multi-service homelessness intervention programmes), Humphries and Canham (Reference Humphries and Canham2019) did not provide a detailed description of different shelter/housing options. The review by McGhie et al. (Reference McGhie, Barken and Grenier2013) identified affordable housing, supported and supportive housing, emergency shelter/housing and long-term care as models for OPEH, however, their literature review was limited to options in Canada only. With unique political and social landscapes across different countries, there is a range of shelter/housing options, supports and interventions for OPEH which have not been captured in earlier reviews that were limited in scope or geography. The purpose of this study is to identify and describe shelter/housing options, supports and interventions (i.e. models) for OPEH, as well as reported outcomes. Our guiding research question is:

• What shelter/housing options, supports and interventions have been developed for older people (age 50+) who are currently or formerly experiencing homelessness?

We subsequently ask:

• What are the reported outcomes of these shelter/housing options, supports and interventions?

Methods

We used a scoping review methodology based on Arksey and O'Malley (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005), which enables researchers to capture rigorously and transparently the nature and breadth of the literature without assessing the quality of evidence. We also drew from the recommendations for conducting scoping reviews of Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010) by establishing well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (step 1), and using these criteria and the research question to identify relevant studies (step 2). We then selected studies (step 3) in an iterative process whereby authors JH and PM independently reviewed titles and abstracts for inclusion, meeting weekly with author SC to discuss process and progress, and using Covidence software (https://www.covidence.org) to assist in the organisation of relevant and selected studies. During weekly meetings, discrepancies in authors’ inclusion decisions were discussed by the three authors until a final determination was made. Studies that met the following criteria were included: (a) described a shelter/housing option, support or intervention for OPEH (age 50+ and currently or formerly experiencing homelessness – absolutely homeless, residing in a place unsuitable for habitation, a shelter or transitional housing, or at-risk of homelessness); (b) presented primary empirical data; and (c) available in the English language. Both peer-reviewed and grey literature were included if primary empirical data were presented, while literature reviews and policy reviews were excluded if no primary data were presented. Additionally, a hand search of articles in the bibliographies of these documents was conducted to identify relevant studies. Next, using Excel as an organisational tool, the research team developed a data-charting form, which included study location, study design, participant characteristics, a description of the model and main findings, and JH and PM independently extracted and charted data (step 4). Finally, results were summarised and collated (step 5), enabling the research team to report results relevant to the study's research question (Levac et al., Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010).

Study selection

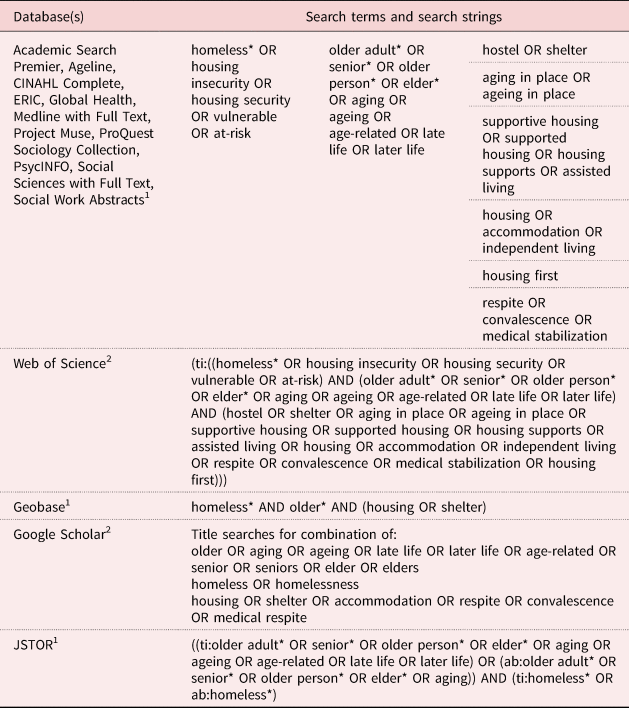

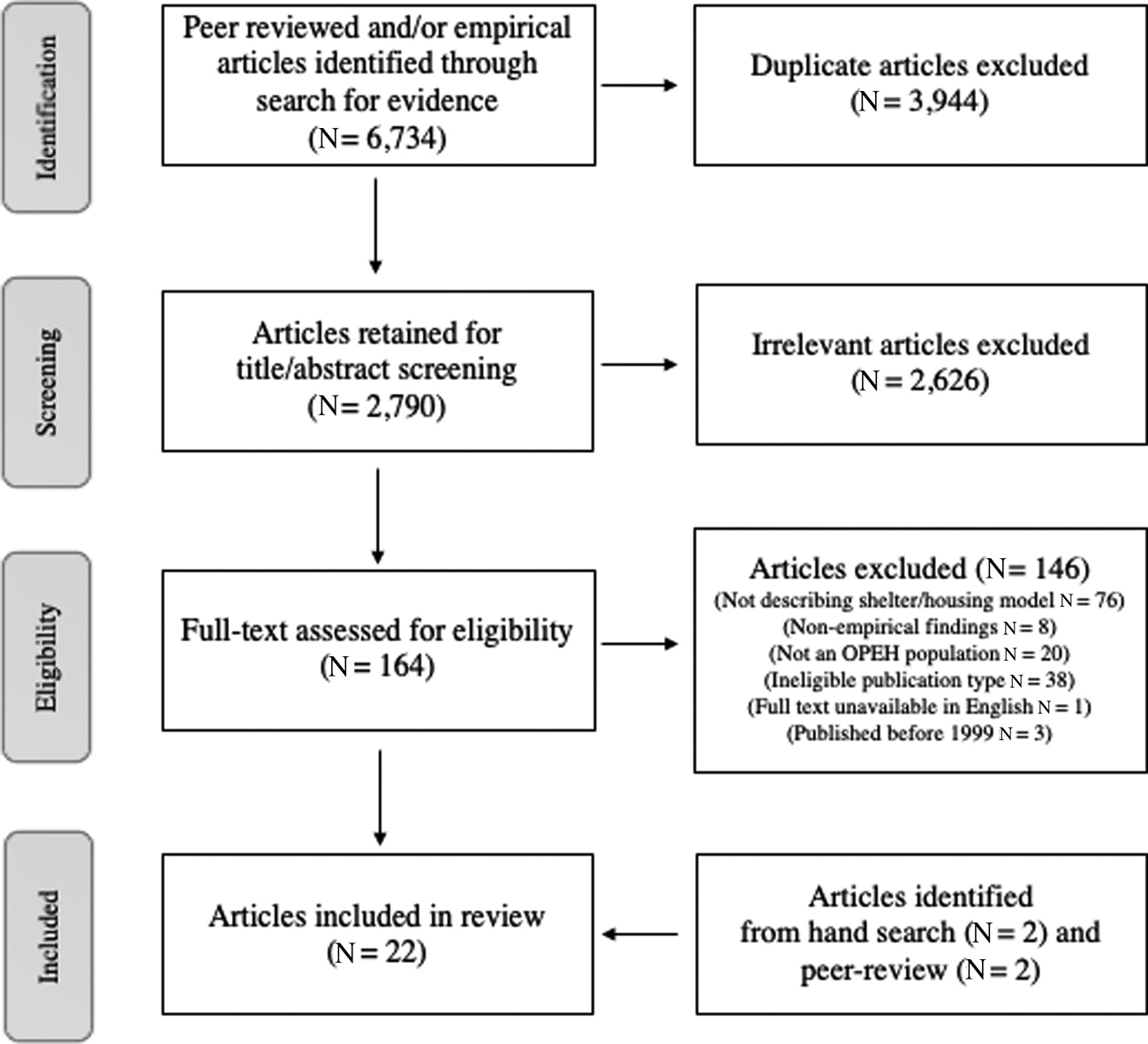

To establish an effective search strategy (Levac et al., Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010), SC consulted with a university librarian to develop a study protocol and to determine specific search databases and criteria, including search terms and strings that would enable the capture of available literature within range (sensitivity) and relevance (specificity). From 24 August 2019 to 15 October 2019, JH and PM searched 15 databases (Academic Search Premier; Ageline; CINAHL Complete; ERIC; Geobase; Global Health; Google Scholar; JSTOR; Medline with Full Text; ProQuest Sociology Collection; Project Muse; PsycINFO; Social Sciences with Full Text; Social Work Abstracts; and Web of Science) for English-language peer-reviewed and/or empirical literature published from 1999 to 2019. Keyword searches included various combinations of terms, including homeless, at-risk, older adult, senior, aging/ageing, shelter, housing, accommodation, respite, etc. (Table 1). Results revealed 6,734 references, of which 3,944 duplicates were removed (for the PRISMA flow diagram, see Figure 1). Titles and abstracts of 2,790 articles were assessed for inclusion by JH and PM, and through discussion with SC any discrepancies in article inclusion were resolved, resulting in 164 articles for full-text review. During the full-text review, if a text described empirical findings, a hand-search of that text's bibliography was conducted to identify any literature not previously captured.

Table 1. Databases, search terms and search strings

Notes: ab: abstract. ti: title. 1. Both title and abstract searched in these databases. 2. Only title searched in these databases.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of literature inclusion.

Note: OPEH: older people with experiences of homelessness.

During study selection, studies were excluded for not describing a model (N = 76); reporting non-empirical programme descriptions or findings from a literature review or policy review (N = 8) or on a population other than OPEH (N = 20); and being the wrong publication type (N = 38), unavailable in English (N = 1) or published prior to 1999 (N = 3). After screening, 18 articles remained; additional sources that met criteria for inclusion were identified through the hand-search (N = 2) and following peer-review (N = 2), resulting in a total of 22 articles included in the review.

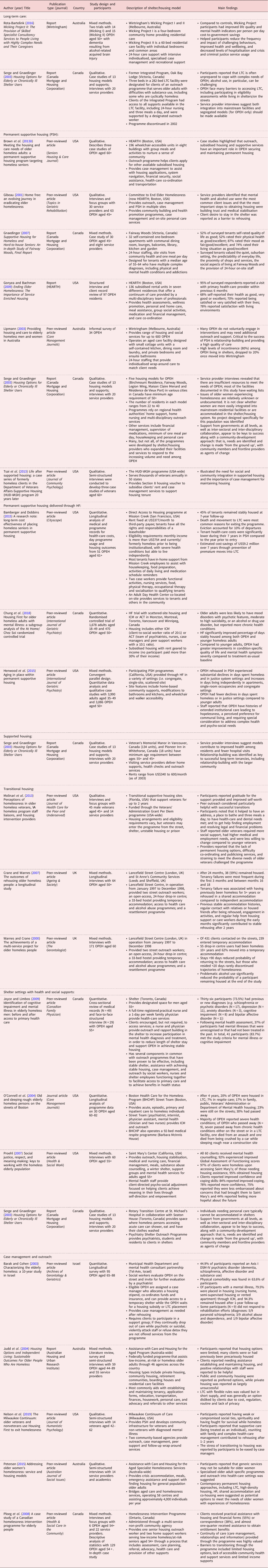

The sources that reported research data used mixed (N = 8), qualitative (N = 7) and quantitative (N = 5) methods, while two sources reported conducting surveys but did not indicate if they were mixed methods or quantitative. Fifteen of the studies collected data from OPEH, two from service providers, and five from both service providers and OPEH. Sixteen sources were peer-reviewed articles, one was a non-peer-reviewed article and five were reports. Sources reported research and programme initiatives from the United States of America (USA; N = 10), Canada (N = 5), Australia (N = 4), the United Kingdom (UK; N = 2) and Israel (N = 1).

Data analysis

Data charting was an iterative process whereby JH and PM independently extracted data from all 22 studies and subsequently met to compare results (Levac et al., Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010). Once data were extracted, SC reviewed the findings and participated in in-depth discussions with the other two researchers until the research team agreed on the summary of each study's findings. Through the process of reading and discussing the studies and extracted data, the research team organised findings into higher-level categories. As a result, six shelter/housing and service models were identified, reviewed and agreed upon by the research team.

Findings

The findings of this scoping review were categorised according to the provision of a physical structure and the services and supports offered to clients, resulting in: (1) long-term care (LTC), (2) permanent supportive housing (PSH), including PSH delivered through Housing First (HF), (3) supported housing, (4) transitional housing, (5) emergency shelter settings with health and social supports, and (6) case management and outreach (Table 2). Though these six categories are discussed separately to highlight their unique characteristics, there exists some overlap between them, which are noted in the sections below.

Table 2. Literature sources, study characteristics, description of shelter/housing model and main findings

Notes: ACT: assertive community treatment. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edn. HF: Housing First. ICM: intensive case management. LTC: long-term care. OPEH: older people with experiences of homelessness. PSH: permanent supportive housing. UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America.

(1) Long-term care (LTC)

Research suggests that LTC designed to provide nursing care to general populations of older adults and others requiring complex care is often unprepared to manage the needs of OPEH, including alcohol use, smoking and other behaviours (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003). Moreover, OPEH face barriers to accessing LTC as eligibility assessments are not conducted with OPEH who are staying in a shelter or on the street (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003). In response to these challenges, the Integrated Program at Oak Bay Lodge in Victoria, Canada (which was discontinued in 2002) designated three beds in a 282-bed LTC facility for older adults with difficulties with substance use, including some who were cyclically homeless (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003). Clients of the Integrated Program had access to all supports available in the LTC facility, including 24-hour nursing and three meals a day, and were supported by a designated outreach worker (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003). Outcomes of the effectiveness of this model are unknown.

In a similar model in Melbourne, Australia, Wintringham, Wicking Project I and II provides long-term residential care for OPEH with dementia resulting from alcohol-related acquired brain injury in a four-bedroom community home (in Wicking I) and a 60-bed residential care facility with individual bedrooms and common area (in Wicking II). These programmes provide intensive, individualised recreational support and specialised case management and recreational support (Rota-Bartelink, Reference Rota-Bartelink2016). When compared to control OPEH clients, Wicking Project clients were less expensive. Moreover, Wicking I and II helped participants reduce the frequency and impact of challenging behaviours, improved health and wellbeing, and decreased levels of hospitalisation and crisis and criminal justice service use (Rota-Bartelink, Reference Rota-Bartelink2016).

(2) Permanent supportive housing (PSH)

PSH models provide affordable housing and supportive services for people experiencing chronic homelessness in either scattered or single-site settings (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Thomas, Cutler and Hinderlie2013b; Henwood et al., Reference Henwood, Katz and Gilmer2015). Services range widely, but include social supports (e.g. case management, meals, home-making services) and/or medical supports (e.g. nursing, psychiatric treatment, substance use counselling) (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Thomas, Cutler and Hinderlie2013b; Bamberger and Dobbins, Reference Bamberger and Dobbins2015).

Operating in Boston, MA, HEARTH (formerly the Committee to End Elder Homelessness) provides outreach services and subsidised PSH rental units for OPEH in seven different residences that offer a continuum of care provided by a multi-disciplinary team of professionals (e.g. social workers, care aides) and 24-hour staffing to support complex physical and mental health challenges (Gibeau, Reference Gibeau2001; Gonyea and Bachman, Reference Gonyea and Bachman2009; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Thomas, Cutler and Hinderlie2013b). Fairway Woods in Victoria, Canada offers PSH with a variety of common spaces that promote social interaction and community-building for OPEH, as well as meals and 24-hour medical and social support (Gnaedinger, Reference Gnaedinger2007). Operating under a harm reduction approach (Pauly et al., Reference Pauly, Reist, Schactman and Belle-Isle2011), Wintringham in Melbourne, Australia delivers a variety of medical, housing and outreach services for over 600 OPEH, including a PSH programme that provides small home-like cottages with a self-contained kitchen, dining room, laundry and private bedrooms that are staffed 24 hours (Lipmann, Reference Lipmann2003). Similarly, the Résidence du Vieux Port in Montréal, Canada provides PSH for OPEH with mental health and/or alcohol use conditions and permits on-site alcohol use (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003). Finally, while all PSH programmes provide subsidised housing, the US Housing and Urban Development-Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) programme, which provides PSH through wrap-around case management services to veterans experiencing homelessness, is the only identified PSH model that uses a housing voucher (i.e. a government subsidy paid directly to the landlord) as a method of subsidising rent (Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Klee, Remmele and Harkness2013).

The existing research indicates that placement in PSH contributes to improved relationships, health, wellbeing, stability, connection to health-care providers, and feelings of satisfaction and security among OPEH (Gnaedinger, Reference Gnaedinger2007; Gonyea and Bachman, Reference Gonyea and Bachman2009). Furthermore, research suggests that PSH is an appropriate setting for OPEH who may be too young or not a good ‘fit’ in aged care facilities, but whose needs are too complex for shelter accommodation (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003). While transitions into PSH can be stressful for some OPEH, the research suggests that individualised, person-centred outreach and case management improves healthy behaviours and facilitates reconnections with family, which contribute to reduced stress, recovery and perceptions of stable rehousing (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Morzinski and Flower2019). Moreover, ongoing case management and support with substance use and mental health challenges are important to OPEH's stability in PSH (Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Klee, Remmele and Harkness2013), and caring and helpful service providers contribute to OPEH's positive perceptions of PSH (Gibeau, Reference Gibeau2001). In North America, one sub-category of PSH has been implemented successfully through HF programmes.

(2a) PSH delivered through HF

As a sub-category, some PSH models are delivered using a HF philosophy. HF takes a person-centred, rights-based approach to rehousing to provide direct access to housing for people experiencing homelessness living with mental illness, without prerequisites that OPEH are sober or participate in treatment (Bamberger and Dobbins, Reference Bamberger and Dobbins2015; Henwood et al., Reference Henwood, Katz and Gilmer2015; Chung et al., Reference Chung, Gozdzik, Palma Lazgare, To, Aubry, Frankish, Hwang and Stergiopoulos2018). Furthermore, HF clients are supported through either intensive case management (ICM: weekly meetings with a case manager to develop and implement an individualised care plan) or assertive community treatment (24-hour access to a care team of medical providers, case managers and peer support workers who collaboratively address client concerns and implement individualised care plans) (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Gozdzik, Palma Lazgare, To, Aubry, Frankish, Hwang and Stergiopoulos2018).

Mission Creek Apartments in San Francisco, CA have no prerequisites for sobriety and is co-located with an adult day centre that offers functional activities, nursing services and opportunities for socialisation to tenants and community members (Bamberger and Dobbins, Reference Bamberger and Dobbins2015). Research suggests that PSH HF strategies increase the number of days OPEH are stably housed, while reducing mental health symptom severity (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Gozdzik, Palma Lazgare, To, Aubry, Frankish, Hwang and Stergiopoulos2018). Henwood et al. (Reference Henwood, Katz and Gilmer2015) found that after engagement with PSH HF services, OPEH experienced a substantial decline in days spent homeless or in justice settings and an increase in days spent living independently in an apartment. Furthermore, PSH HF models have been found to contribute to longer tenancy outside a skilled nursing facility (Bamberger and Dobbins, Reference Bamberger and Dobbins2015).

(3) Supported housing

While similar to PSH in that it offers residents permanent housing, supported housing deviates from PSH in that services and supports are not integrated with the housing, but are offered separately. Two models of supported housing identified (Veteran's Memorial Manor in Vancouver, Canada has 134 units; and Pioneer Inn in Whitehorse, Canada has 18 units) have minimum age requirements between 55+ and 45+ years old, respectively, and bring service providers on-site to deliver home support, nursing, health checks and multi-disciplinary outreach services (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003). These services support residents’ daily activities and research suggests that supported housing contributes to improved health among residents, fewer hospital visits and reduced health-care costs (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003). In addition, relationship-building has been identified as key to successful long-term tenancies, including integration into the larger community (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003).

(4) Transitional housing

Transitional housing provides time-limited move-in and rental assistance and/or physical accommodation to individuals with the aim of providing quick access to housing, as well as support stabilising, so individuals can move into permanent housing (Gaetz, Reference Gaetz2014). The US Veterans’ Administration Grant Per Diem programme offers funding for up to two years of community-based transitional housing and case management to veterans living on the street, in shelters, unstable housing or prison (Molinari et al., Reference Molinari, Brown, Frahm, Schinka and Casey2013). In operation from 1997 to 1998, the Lancefield Street Centre in London, UK provided services to OPEH to enable progression from street living to resettlement in long-term accommodation, including two street outreach workers, a 24-hour drop-in centre, a 33-bed hostel providing temporary accommodation, access to health-care and alcohol-use programmes, and a resettlement programme (Warnes and Crane, Reference Warnes and Crane2000; Crane and Warnes, Reference Crane and Warnes2007).

Research suggests that having a stable address, access to meals and bathing facilities, assistance with financial, legal and employment issues, and co-ordinated health and dental care support the self-worth and achievement of permanent housing goals for OPEH (Molinari et al., Reference Molinari, Brown, Frahm, Schinka and Casey2013). In addition, longer stays in transitional housing have been found to reduce OPEH's chances of returning to the streets (Warnes and Crane, Reference Warnes and Crane2000). Having had a previously stable accommodation history, engagement in activities, regular contact with relatives and regular assistance from housing support or care workers during the early months of being in transitional housing have been associated with housing stability (Crane and Warnes, Reference Crane and Warnes2007).

(5) Emergency shelter settings with health and social supports

Though some research suggests that homeless shelters can be unsupportive environments for OPEH with complex health conditions (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003; Burns, Reference Burns2016; Canham et al., Reference Canham, Custodio, Mauboules, Good and Bosma2020), accessible shelter settings with appropriate health and social services have been found to support OPEH during housing crises (McLeod and Walsh, Reference McLeod and Walsh2014). In Toronto, Canada one shelter offers health-care services to OPEH delivered by a full-time registered practical nurse and a drop-in family physician, including screening for mental health and cognitive impairment (Joyce and Limbos, Reference Joyce and Limbos2009). Also in Toronto, the Rotary Transition Centre provides shelter where homeless persons accessing acute care can shower, eat and wash clothes while psychiatrists, students and residents serve clients through the Psychiatry Shelter Outreach Program (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003). Another model, the Boston Healthcare for the Homeless Program (BHCHP), employs a ‘street team’ (i.e. a psychiatrist, internist, physician assistant, mental health clinician and two nurses) which connects with and provides health-care outreach to OPEH living on the streets and in shelters, the majority of whom report severe health conditions (O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Roncarati, Reilly, Kane, Morrison, Swain, Allen and Jones2004). BHCHP also operates the Barbara McInnis House, a 92-bed medical respite programme for OPEH (O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Roncarati, Reilly, Kane, Morrison, Swain, Allen and Jones2004). Saint Mary's Center in California provides OPEH-directed services, including outreach, housing system navigation, medical care, mental health services, financial management, substance use counselling, support groups and a winter shelter (Proehl, Reference Proehl2007).

Research suggests that bringing medical resources into shelters can help rehouse OPEH in supportive settings that meet their needs, including LTC, respite care and public housing (O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Roncarati, Reilly, Kane, Morrison, Swain, Allen and Jones2004). Furthermore, having health-care services integrated into shelter settings has been found to help identify and treat previously undiagnosed cognitive impairment and mental illness, resulting in positive health, wellbeing and tenancy outcomes (Crane and Warnes, Reference Crane and Warnes2007; Joyce and Limbos, Reference Joyce and Limbos2009). For example, among OPEH who received mental health counselling in Saint Mary's Center, the majority reported improved confidence and coping skills (Proehl, Reference Proehl2007). Moreover, continued engagement with health and social services has been found to improve the likelihood of OPEH securing and maintaining permanent accommodation (Proehl, Reference Proehl2007).

(6) Case management and outreach

Finally, while not providing a physical structure, case management and outreach was identified as a model to support OPEH. In particular, a flexible and respectful approach to care, building trust and personal relationships, caring attitudes and helpfulness from staff, provision of supportive services and advocacy, and access to a broad range of available, affordable housing options have been reported as essential components of programming for OPEH (Gibeau, Reference Gibeau2001; Lipmann, Reference Lipmann2003; Judd et al., Reference Judd, Kavanagh, Morris and Naidoo2004; Petersen, Reference Petersen2015). Noted previously, HEARTH (Boston) employs a team of case managers who provide outreach to OPEH living in shelters and precarious housing to assist with housing navigation, health-care co-ordination, financial issues, substance use treatment and securing benefits (Gibeau, Reference Gibeau2001; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Thomas, Cutler and Hinderlie2013b). In Milwaukee, WI, the Milwaukee Continuum of Care connects older veterans and non-veterans experiencing homelessness to HF programmes using peer support outreach specialists, who build trusting relationships with clients and provide linkages to case managers who design personalised care plans with clients and co-ordinate wrap-around support through the rehousing process (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Morzinski and Flower2019). Similarly, a homelessness intervention programme in Toronto, Canada employs an outreach worker who provides assessment, care planning, practical assistance, referrals, advocacy and follow-up to assist in the placement and maintenance of permanent housing for OPEH (Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Hayward, Woodward and Johnston2008). An outreach programme in Tel Aviv, Israel utilises an ICM team of case managers, criminologists and a psychiatrist to identify OPEH in the community, evaluate their mental health and assist with placement in appropriate supported or independent housing (Barak and Cohen, Reference Barak and Cohen2003). Finally, in Australia, the federally funded Assistance with Care and Housing for the Aged Program assists OPEH to establish and maintain housing tenancy, complete application forms, transportation, personal care, meals, housework, financial assistance, advocacy, crisis accommodation and referral to other services (Judd et al., Reference Judd, Kavanagh, Morris and Naidoo2004; Petersen, Reference Petersen2015).

The available research amongst OPEH who may experience barriers or challenges to accessing support suggests that case management (including ICM) and outreach yields positive health and housing outcomes (Barak and Cohen, Reference Barak and Cohen2003; O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Roncarati, Reilly, Kane, Morrison, Swain, Allen and Jones2004; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Morzinski and Flower2019). For OPEH, including those living with mental and physical illness, case management and outreach have been found to contribute to getting placed in housing and maintaining long-term housing (Barak and Cohen, Reference Barak and Cohen2003; O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Roncarati, Reilly, Kane, Morrison, Swain, Allen and Jones2004). For OPEH, there are a range of housing types that meet different levels of health and social need, and navigating wait times and the stress of transitioning into housing was reportedly eased when assisted by case managers (Petersen, Reference Petersen2015; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Morzinski and Flower2019). Moreover, continuity of care and practical assistance in completing housing and financial forms has been reported as highly valued by OPEH receiving outreach services (Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Hayward, Woodward and Johnston2008).

Discussion

This review identified six shelter/housing options, supports and interventions for OPEH and, where possible, the impact of these models on health and housing outcomes for OPEH. Models were categorised according to the provision of a physical structure and the formal services and supports offered. This categorisation aligns with research that suggests that OPEH have a broad range of needs, which require diverse options, supports and interventions (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003; Burns and Sussman, Reference Burns and Sussman2019; Canham et al., Reference Canham, Custodio, Mauboules, Good and Bosma2020) and builds upon the categorisation by Humphries and Canham (Reference Humphries and Canham2019) (HF, PSH and multi-service interventions) and McGhie et al. (Reference McGhie, Barken and Grenier2013) (affordable housing, supported and supportive housing, emergency housing/shelter, and LTC).

Providing the highest level of support, LTC and PSH models provide permanent housing with on-site health and social supports. Both LTC models identified in this review support OPEH with drug- and alcohol-related challenges, including acquired brain injury. Prior research has identified OPEH who are chronic alcohol users as having few or no supports available because options for OPEH are too expensive, do not permit the use of alcohol and do not support individuals who experience alcohol-related behavioural issues (Canham et al., Reference Canham, Custodio, Mauboules, Good and Bosma2020). However, the Wicking Projects and the Integrated Program reported on the value – to both individual outcomes and health-care cost savings – of providing 24-hour individualised support to sub-populations of OPEH who chronically use alcohol.

PSH models were the most commonly identified shelter/housing option for OPEH, serving a diverse range of individuals in the USA, UK and Australia in a range of housing typologies (e.g. scatter site, congregate). While a few models identified specific target populations of OPEH, including veterans (Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Klee, Remmele and Harkness2013) and those living with mental health disorders (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Gozdzik, Palma Lazgare, To, Aubry, Frankish, Hwang and Stergiopoulos2018), most research did not describe population-specific programme development or outcomes for any sub-groups of OPEH. Instead, studies focused on the similarities across models centred on the integration of housing and services, and the benefits of PSH for housing, health and social outcomes for OPEH. Supported housing models, of which only two were identified (Serge and Gnaedinger, Reference Serge and Gnaedinger2003), were also found to result in positive outcomes for OPEH, though these models require services to be brought on-site by health and social support agencies.

Two transitional housing models for OPEH were identified, including one that provides transitional supportive housing to older veterans for up to two years (Molinari et al., Reference Molinari, Brown, Frahm, Schinka and Casey2013), and a second (Lancefield Street Centre) that supports rehousing single older adults in the UK from homeless hostels into permanent housing (Warnes and Crane, Reference Warnes and Crane2000; Crane and Warnes, Reference Crane and Warnes2007). Both models supported single, unattached OPEH, but varied in how OPEH were supported to move from the street, shelter, unstable housing or prison into permanent housing. Similar to findings from other models identified in this review, OPEH clients in transitional programmes were more successful in rehousing when they were able to maintain connection to positive peer support and formal social support, and less successful if clients had long histories of homelessness or problematic alcohol use.

Several shelters that provide health and social supports to OPEH were identified in both the USA and Canada; similar to transitional models, shelters provide accommodation and services, but only temporarily. Regardless of country or shelter site, key features that were found to support OPEH include inter-professional health and social care teams that collaborate to serve clients on the street or in the shelter. In addition, the identification of previously undiagnosed cognitive and mental health conditions was a reported benefit (Joyce and Limbos, Reference Joyce and Limbos2009). Research on the identified shelter models did not distinguish between client outcomes based on gender or race/ethnicity. Instead, the primary focus of programme delivery and similarity among OPEH clients across all sites and studies was the need for complex and integrated care co-ordination, whether it be for detox, rehabilitation or medical respite (O'Connell et al., Reference O'Connell, Roncarati, Reilly, Kane, Morrison, Swain, Allen and Jones2004; Proehl, Reference Proehl2007).

Finally, while case management and outreach do not provide a physical structure where OPEH can sleep, research from the USA, UK, Australia and Israel suggested the importance of this model for offering OPEH with the services and supports needed to establish and maintain housing, access practical and financial assistance, and have continuity in their physical and mental health care. Of the five models identified in this category, several (Barak and Cohen, Reference Barak and Cohen2003; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Morzinski and Flower2019) emphasised the value of case management in serving OPEH clients who have mental health disorders. Only one (Petersen, Reference Petersen2015) described the need for gender-specific considerations, suggesting that generic services may not be suitable. Taken together, there was a notable gap in the literature on which sub-populations of OPEH are best served by the different categories of shelter/housing support.

Alignment with conceptualisations of ageing in the right place

Research on ageing in the right place recognises that where older persons live impacts their ability to age optimally and must match their unique lifestyles and vulnerabilities – in other words, the ‘right’ set of housing, health and social supports can enable diverse groups of older adults (including older adults with limited income and/or chronic complex health conditions) to age in a positive way (Golant, Reference Golant2015). While ageing in place for general populations of housed older adults is supported through physical, psychological, social and functional aspects of the home and community environment (Greenfield, Reference Greenfield2012; Sixsmith et al., Reference Sixsmith, Fang, Woolrych, Canham, Battersby and Sixsmith2017), our findings demonstrate that, due to the unique needs of OPEH, additional support is needed in order to promote ageing in ‘the right’ place (Woolrych et al., Reference Woolrych, Gibson, Sixsmith and Sixsmith2015; Canham et al., Reference Canham, Battersby, Fang, Wada, Barnes and Sixsmith2018). Prior research has indicated that ageing in the right place for OPEH requires shelter/housing models to include health and social supports that contribute to positive outcomes, a sense of belonging and community reintegration (Waldbrook, Reference Waldbrook2015; Grenier et al., Reference Grenier, Barken and McGrath2016a). Building upon this, our review suggests additional considerations for promoting ageing in the right place for diverse OPEH, including (a) social connection and trusting relationships, including from peer supports; (b) individualised services and supports, including 24-hour on-site physical and mental health care; and (c) permanent supportive housing options that are co-located with opportunities for socialisation and transportation to off-site services. These considerations are suggestive of not merely the individual-level aspects of how to support OPEH to age in the right place but attend to the mezzo- and macro-level systems and policies (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, Reference Bronfenbrenner, Morris, Damon and Lerner2006) that enable or challenge ageing in the right place. For instance, in regions where there is limited affordable housing, the ability for OPEH to remain in their homes or communities of choice becomes less feasible (Canham et al., Reference Canham, Battersby, Fang, Wada, Barnes and Sixsmith2018).

Aligned with previous literature (Burns, Reference Burns2016; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Lorenzetti, St-Denis, Murwisi and Lewis2016; Bazari et al., Reference Bazari, Patanwala, Kaplan, Auerswald and Kushel2018; Finlay et al., Reference Finlay, Gaugler and Kane2020), findings from this review suggest that social connection and relationship-building among OPEH, service providers and the surrounding community is highly valued by both OPEH and staff, and is associated with successfully establishing and maintaining housing (Gibeau, Reference Gibeau2001; Lipmann, Reference Lipmann2003; Judd et al., Reference Judd, Kavanagh, Morris and Naidoo2004; Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Klee, Remmele and Harkness2013). Indeed, restoring social connections promotes feelings of value and self-worth among OPEH (Gonyea and Melekis, Reference Gonyea and Melekis2017). Moreover, continuity of care during the rehousing process has been found to rebuild a sense of trust and promote a sense of social connection that buffers against future homelessness (Crane and Warnes, Reference Crane and Warnes2007; Ploeg et al., Reference Ploeg, Hayward, Woodward and Johnston2008). Beyond formal relationships with staff, connection with peers who have successfully navigated rehousing has been suggested as an avenue to combat the shame, anxiety and stigma experienced by OPEH (Grenier et al., Reference Grenier, Sussman, Barken, Bourgeois-Guérin and Rothwell2016b). The value of social connection and trusting relationships cannot be overstated, as strong social networks are integral to supporting OPEH who are at risk of isolation and prolonged homelessness (Kimbler et al., Reference Kimbler, DeWees and Harris2017).

In light of findings that housing and supports contribute to decreased homelessness and days involved in justice settings among OPEH (Henwood et al., Reference Henwood, Katz and Gilmer2015), while increasing health and quality-of-life outcomes (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Gozdzik, Palma Lazgare, To, Aubry, Frankish, Hwang and Stergiopoulos2018) and cost savings on health-care expenditures (Bamberger and Dobbins, Reference Bamberger and Dobbins2015), models that want to promote ageing in the right place for OPEH should offer individualised services and supports. Highlighted in this review, the individualised service needs of diverse OPEH may require co-ordinated health care or 24-hour on-site physical and mental health care, substance use counselling, housing navigation assistance (i.e. finding and maintaining permanent accommodation) and financial support. Such individualised support should integrate culturally sensitive (Chau et al., Reference Chau, Yu and Tran2011) and trauma-informed approaches by focusing on individual strengths, safety and personal development (McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Dergal and Cleghorn2007; Hopper et al., Reference Hopper, Bassuk and Olivet2010; Gaetz et al., Reference Gaetz, Scott and Gulliver2013). Coupling culturally sensitive, trauma-informed practice with flexible and individualised (i.e. person-centred) health supports (Henwood et al., Reference Henwood, Shinn, Tsemberis and Padgett2013) and adequate resources (Canham et al., Reference Canham, Davidson, Custodio, Mauboules, Good, Wister and Bosma2019) within shelter/housing can promote ageing in the right place for OPEH (Humphries and Canham, Reference Humphries and Canham2019).

Finally, despite limited availability, there is some indication that models that co-locate permanent supportive housing with opportunities for socialisation and transportation to off-site services are well-suited to meet the diverse physical, mental and social needs of OPEH (Bamberger and Dobbins, Reference Bamberger and Dobbins2015). Such models have the opportunity to support nutrition, social connection, physical and mental health therapy, and more in a central location. Co-located, community-based models that recognise and support OPEH-specific needs and activities have significant potential to promote ageing in the right place for this population. In addition, models that prevent eviction are needed (Crane et al., Reference Crane, Byrne, Fu, Lipmann, Mirabelli, Rota-Bartelink, Ryan, Shea, Watt and Warnes2005; Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, Hewson, Paul, Gulbrandsen and Dooley2015), including utility subsidies, which reduce financial strain for low-income older adults (Bottomley, Reference Bottomley2001).

Several limitations to this scoping review require noting. We limited our search to peer-reviewed and grey literature in which empirical data were reported. This may have excluded reports that describe shelter/housing models that support various sub-groups of OPEH, including Indigenous elders, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, and two-spirit (LGB+) seniors, older veterans or older women fleeing violence. Moreover, as a result of publication bias, non-significant findings are rarely published and, therefore, not captured in this review. Additional efforts are needed to identify the distinct needs of sub-groups of OPEH and to develop models to support their capacity to age in the right place. In addition, future research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of different models that have not been subject to rigorous evaluation in order to determine what ‘works and for whom’ (Canadian Homelessness Research Network, 2013). As OPEH are a heterogeneous population, the models that best support different sub-groups of OPEH remain to be determined.

While we examined literature from 1999 to 2019, 13 of the 22 sources were published between 1999 and 2009, which may impact their relevance to the experiences of OPEH today. We were also limited to reviewing literature available in English. In addition, our identification of models embedded within different housing and health-care delivery and policy systems does not enable us to achieve consensus about best practices. Nevertheless, we were able to identify a broad range of models. Finally, our review may be limited in that we did not assess the quality of evidence reported in the research reviewed, as this is not the goal of a scoping review. Instead, our goal was to determine the extent, range and nature of existing literature on shelter/housing options, supports and interventions for OPEH, which we achieved.

Findings from this review have enabled us to categorise and describe shelter/housing options, supports and interventions for OPEH. This categorisation can be used as a template for designing and implementing future solutions, while serving as a foundation for research evaluating efficacy and fit of different models that serve as best practices for specific sub-groups of OPEH to age in the right place. Building such an evidence base has significant potential to advance policy, practice and design to better meet the unique needs of diverse OPEH.

Financial support

This research, ‘Aging in the Right Place: Building Capacity to Improve Supportive Housing for Older People Experiencing Homelessness in Montréal, Calgary, and Vancouver’, was supported by a Partnership Development Grant funded by the Canadian Mortgage Housing Corporation (CMHC); and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). The opinions and interpretations in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of CMHC or SSHRC.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.