Suicide is intentional self-killing and it features in every society for which there is recorded history (Beattie & Devitt, Reference Beattie and Devitt2015). Self-harm is the intentional infliction of non-fatal harm on oneself and includes a wide variety of methods such as overdosing and self-cutting. Self-harm also encompasses a variety of levels of suicidal intent, including near-fatal suicide attempts as well as less medically serious episodes of self-harm.

In the early 1900s, it was generally thought that Ireland had a low suicide rate, which is said to have increased significantly as the 20th century progressed, with some fluctuation. In the early 1950s, the Central Statistics Office (1954) reported the annual average number of deaths from suicide in Ireland was 89 between 1921 and 1930 (giving a rate of 3.0/100 000 population per year), 98 between 1931 and 1940 (3.3/100 000 population per year), and 77 between 1941 and 1950 (2.6/100 000 population per year) (Kelly, Reference Kelly2016). Suicide was likely under-reported during this period and, in 1967, the Central Statistics Office introduced a new form (Form 104) to improve recording accuracy and facilitate study. During much of this period, suicide was a felony under Irish law and attempted suicide was a misdemeanour; both offences were abolished in 1993 with the Criminal Law (Suicide) Act.

In 1962, the Samaritans were established in Ireland and their volunteers provide a listening service to anyone who contacts them; many, but not all, of those who contact them are suicidal (www.samaritans.org). By 2016, there were 20 Samaritans branches across Ireland with 2400 active volunteers doing extraordinarily skilled, selfless work; their contribution to Irish society is beyond measure.

In 1996, the Irish Association of Suicidology was founded by Dr John Connolly, Dr Michael Kelleher and Dan Neville T.D., to work with community, voluntary and statutory bodies to inform, educate and promote positive suicide prevention policies. It is a forum where various organisations can come together and exchange knowledge regarding any aspect of suicidology gained from differing perspectives and experiences (www.ias.ie).

Today, there are a number of sources of information and statistics about self-harm and suicide, including the National Suicide Research Foundation, an independent, multidisciplinary research unit that investigates the causes of suicide and self-harm in Ireland (www.nsrf.ie). The National Office for Suicide Prevention (NOSP) was set up in 2005 within the Health Service Executive (HSE) to oversee the implementation, monitoring and coordination of ‘Reach Out: National Strategy for Action on Suicide Prevention, 2005–2014’, Ireland’s first national suicide prevention strategy. NOSP is now a core part of the HSE National Mental Health Division, strongly aligned with mental health promotion and specialist mental health services (www.nosp.ie).

How common are self-harm and suicide?

Globally, over 800 000 people die due to suicide every year, and for every suicide there are many more people who engage in self-harm (World Health Organisation, 2017). Suicide is the second leading cause of death among 15- to 29-year olds around the world.

Rates of self-harm and suicide change significantly over time. In broad terms, recent years have seen a reduction in the rate of suicide in Ireland, despite the economic recession of 2008–2013. But rates of self-harm and suicide are not evenly distributed across age groups and there are particular reasons to be concerned about younger adults.

Turning to self-harm first, NOSP’s 2015 Annual Report analysed trends in suicide and self-harm in Ireland from 2002 to 2015 (NOSP, 2016), for which it presented provisional figures drawn from National Self-Harm Registry Ireland (www.nsrf.ie) (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Arensman, Dillon, Corcoran, Williamson and Perry2016). In 2015, there were 11 189 presentations to hospitals in Ireland due to self-harm, involving 8791 individuals. This gives an overall rate of 204 episodes of self-harm per 100 000 population per year, which is essentially the same as the rate in 2002, 6 years prior to the recession (NOSP, 2016).

Just over half (55%) of presentations with self-harm are by women. The highest rate among females is in the 15- to 19-year-age group, which has a rate of 718 episodes of self-harm per 100 000 population per year, meaning that one in every 139 girls in this age group presents to a hospital with self-harm in a given year. The highest rate among men is among 20- to 24-year olds, at 553 per 100 000 per year, or one in every 181 men in that age group.

The National Self-Harm Registry Ireland’s Annual Report for 2015 reports that two acts of self-harm in every three involve taking an overdose; one in every three involves alcohol; and one-quarter involve self-cutting (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Arensman, Dillon, Corcoran, Williamson and Perry2016). There is a higher incidence of self-harm in urban compared to rural areas, and the highest numbers of presentations to hospitals are on Mondays and Sundays.

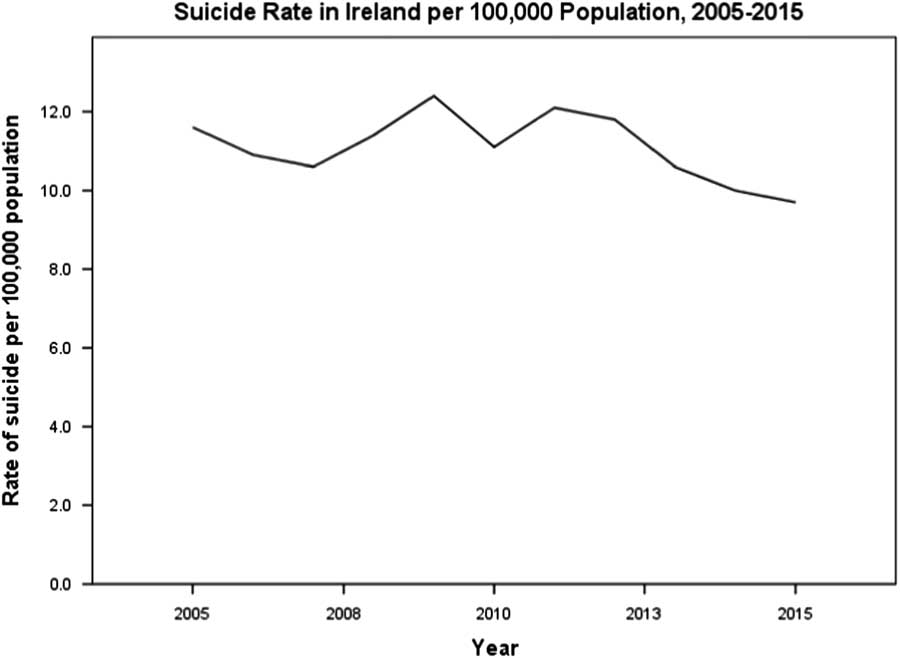

Turning to the suicide, NOSP’s 2015 Annual Report records that there were 554 suicides in 2011, 541 in 2012, 487 in 2013, 459 in 2014 and 451 in 2015.Footnote 1 This is a 19% decrease over 5 years despite likely population growth. The 2015 report also notes that the rate of suicide in 2005 was 11.6/100 000 population per year, and by 2015 this had fallen to 9.7/100 000 population per year, following some fluctuation over the course of the decade (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Suicide rate in Ireland per 100 000 population, 2005–2015. Source: NOSP (2016).

Consistent with previous years, the 2015 suicide rate in men (16.4/100 000 population per year) was substantially higher than that in women (3.2/100 000 population per year). While under-reporting likely remains an issue, it is noteworthy that the rate of undetermined deaths (which might well include some suicides) also fell over the past decade, from 3.2/100 000 population per year in 2005 to 1.5 in 2015.

How does Ireland compare internationally? In its 2013 Annual Report, NOSP (2014) presented figures comparing the Irish suicide rate with those of other European countries. This comparison showed that Ireland’s overall suicide rate was relatively low by European standards, 11th lowest in the EU. In 15- to 19-year-age group, however, Ireland’s rate was the fourth highest in the EU, in dramatic contrast with Ireland’s overall rate and with rates in that age group in other countries.

In 2015, Ireland’s suicide rate among males aged 15–24 years increased to 21.5/100 000 population per year, compared to 16.4 for all males in Ireland and 3.6 for females aged 15–24 years. Rates among men also increased in other age groups; for example, in the 25- to 34-year-age group, the rate increased to 24.2/100 000 population per year in 2015.

The precise effects of the economic recession of the early 2000s on suicide and self-harm remain unclear, but particular and legitimate concern has emerged about suicide and self-harm in young people (McMahon et al. Reference McMahon, Keeley, Cannon, Arensman, Perry, Clarke, Chambers and Corcoran2014), especially children (Malone et al. Reference Malone, Quinlivani, McGuinness, McNicholas and Kelleher2012) and young men (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Kelleher and Malone2015), most notably between the ages of 25 and 44 years (Corcoran et al. Reference Corcoran, Griffin, Arensman, Fitzgerald and Perry2015).

Despite the overall decrease in suicide in Ireland in the early years of the 21st century, then, rates of youth suicide and self-harm, and suicide in men, remain a real source of concern, especially as rates of youth suicide are persistently very high in Ireland compared to other EU countries. This merits greater investigation and coordinated psychological, social and educational supports for young people in communities, schools and colleges, and through social media (below).

Can self-harm and suicide be predicted?

Given the research findings outlined above, there have been extensive efforts to build models to try to predict self-harm and suicide, and so provide better care. Key risk factors for non-fatal self-harm include female gender, younger age, poor social support, major life events, poverty, being unemployed, being divorced, mental illness and previous self-harm (Williams, Reference Williams1997; Hawton & van Heeringen, Reference Hawton and van Heeringen2009; Turecki & Brent, Reference Turecki and Brent2016).

Key risk factors for suicide include male gender, poor social support, major life events, chronic painful illness, family history of suicide, mental illness and previous self-harm (Williams, Reference Williams1997; Hawton & van Heeringen, Reference Hawton and van Heeringen2009; Turecki & Brent, Reference Turecki and Brent2016). For both self-harm and suicide, availability of means is also significant (e.g. easy availability of tablets to take overdoses) (Zalsman et al. Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, van Heeringen, Arensman, Sarchiapone, Carli, Höschl, Barzilay, Balazs, Purebl, Kahn, Sáiz, Lipsicas, Bobes, Cozman, Hegerl and Zohar2016). In terms of mental illness, suicide is associated with major depression (long-term risk of suicide: 10–15%), bipolar affective disorder (10–20%), schizophrenia (10%) and alcohol dependence syndrome (15%) (Williams, Reference Williams1997). In addition, individuals who engage in self-harm have a 30-fold increased risk of completed suicide over the following 4 years (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Kapur, Webb, Lawlor, Guthrie, Mackway-Jones and Appleby2005).

Despite these associations, the majority of people with these risk factors will not die by suicide, because the increases in risk associated with these risk factors are small and, despite its tragedy and implications, suicide is (from a mathematical viewpoint) a statistically rare event, with fewer than 500 suicides per year in a population of 4.7 million in Ireland.

There have been very many studies of predictive models and all yield essentially similar results. One classic study followed-up almost 5000 psychiatry inpatients after discharge, using a combination of known risk factors to try to predict suicide in this especially high-risk group (Pokorny, Reference Pokorny1992; Nielssen et al. Reference Nielssen, Wallace and Large2017). While this study succeeded in predicting 35 out of 67 subsequent suicides, their model also generated over 1200 ‘false positives’ (i.e. predicted suicide in over 1200 individuals who did not die by suicide). A more recent meta-analysis (Large et al. Reference Large, Kaneson, Myles, Myles, Gunaratne and Ryan2016) and systematic review (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Bhatti, Meader, Stockton, Evans, O’Connor, Kapur and Kendall2016; Mulder et al. Reference Mulder, Newton-Howes and Coid2016) confirm this finding: suicide cannot be predicted at the level of the individual (Murray & Devitt, Reference Murray and Devitt2017).

This is true even for people who have active thoughts of suicide, because the proportion of people with suicidal thoughts who go on to actually complete suicide is less than one in 200 (Gunnell et al. Reference Gunnell, Harbord, Singleton, Jenkins and Lewis2004). This suggests that simple population screening for suicidal thoughts is unlikely to be either effective or efficient in identifying individuals at risk of suicide.

Can self-harm and suicide be prevented?

Evidence for specific interventions

So, if it is impossible to predict suicide accurately at the individual level, what can be done to prevent self-harm and suicide? What is the evidence?

In 2015, the Health Research Board (HRB) published a comprehensive review of the evidence for various methods of suicide prevention, covering evidence relating to means restriction, media guidelines, gatekeeper training, screening, psychosocial interventions, telemental health, web-based suicide prevention, emergency departments, school-based interventions, and veterans and military personnel (Dillon et al. Reference Dillon, Guiney, Farragher, McCarthy and Long2015). While the HRB review found that greater evidence was needed, it also pointed to existing evidence of effectiveness for means restriction and psychotherapy, and potential evidence to support gatekeeper training (e.g. primary care physicians) as part of a multi-faceted strategy.

Evidence to support screening, psychosocial interventions, telemental health and web-based suicide interventions, was more mixed. Evidence in other areas was either inconclusive or preliminary, although that does not mean that various other interventions are necessarily ineffective, but rather than there is currently insufficient evidence to support effectiveness. This very useful HRB report is freely available online for those seeking further information about specific interventions.Footnote 2

Another review, by Zalsman et al. (Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, van Heeringen, Arensman, Sarchiapone, Carli, Höschl, Barzilay, Balazs, Purebl, Kahn, Sáiz, Lipsicas, Bobes, Cozman, Hegerl and Zohar2016), sought out updated evidence for the effectiveness of suicide prevention interventions since 2005 and identified 1797 relevant studies, including 23 systematic reviews, 12 meta-analyses, 40 randomised controlled trials, 67 cohort trials and 22 ecological or population-based investigations. This review found that evidence to support restricting access to lethal means for prevention of suicide has strengthened since 2005, especially with regard to control of analgesics (see below) and hot-spots for suicide by jumping. The authors also found that school-based awareness programmes have been shown to reduce suicide attempts and that the anti-suicidal effects of clozapine and lithium have been substantiated, but might be less specific than was thought.

In addition, the review concluded that effective pharmacological and psychological treatments of depression are important in prevention, but felt that insufficient evidence exists to assess the possible benefits for suicide prevention of screening in primary care, general public education and media guidelines.

Given all of this evidence, then, what can be done in practice to help prevent self-harm and suicide?

Interventions at the level of the individual

Despite the impossibility of statistical or actuarial prediction in individual cases, careful, realistic clinical assessments and explorations of risk are still very useful for guiding treatment and providing support to people who present with suicidal crisis or mental illness – although it must be remembered that these assessments do not provide a basis for statistical or actuarial prediction of precisely which individuals will engage in self-harm or suicide, and precisely which individuals will not. Suicide is simply too rare to be predicted in individual cases.

As a result, even following careful psychiatric clinical evaluation, exploration of risk, full treatment, risk management, communication with family and/or others (possibly necessitating breach of confidentiality), and meticulous follow-up, it is still entirely possible that any given individual will engage in self-harm or suicide. All of the assessments, risk management and treatment services should, of course, be provided as appropriate to each individual case and they might well reduce risk in a general sense. But, even so, the outcome cannot be predicted in any given case: even with the very highest standard of assessment and care on any given day, self-harm or suicide can still occur on that same day and cannot be predicted.

In an overall sense, good primary care, good secondary mental health care, good communication with families and good follow-up quite possibly might all help reduce general risk of suicide (Zalsman et al. Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, van Heeringen, Arensman, Sarchiapone, Carli, Höschl, Barzilay, Balazs, Purebl, Kahn, Sáiz, Lipsicas, Bobes, Cozman, Hegerl and Zohar2016). In 2010, the College of Psychiatry of Ireland (now College of Psychiatrists of Ireland) noted that ‘effective treatment of depression is an important means of reducing suicide rates’ and addressed the much-discussed role of antidepressant medication in adults in some detail:

Untreated depression can have a fatal outcome. Those experiencing moderate to severe depression frequently describe having thoughts of self-harm. Antidepressants are effective in the treatment of depression. The effective treatment of depression is an important means of reducing suicide rates. A huge volume of research in recent years has failed to establish a causal link between antidepressant use and suicide. At an individual level, the period early in treatment may be a time of relatively high risk, as treatment tends to start when the person’s depression is severe and treatment takes some weeks to work. As treatment takes effect and energy and motivation return, people who have recently commenced antidepressant treatment may be more able to act on suicidal thoughts that are inherent to their condition. That the early recovery period is potentially a period of increased risk for suicidality is something of which all doctors should be aware. The College of Psychiatry of Ireland, in unison with the advice of the Irish Medicines Board, recommends close monitoring of all individuals commenced on antidepressant therapy. There is no evidence of a link between antidepressant use and homicide (College of Psychiatry of Ireland, 2010).

Good treatment of depression in primary care (by GPs and their teams) is also essential in trying to reduce suicide rates (Zalsman et al. Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, van Heeringen, Arensman, Sarchiapone, Carli, Höschl, Barzilay, Balazs, Purebl, Kahn, Sáiz, Lipsicas, Bobes, Cozman, Hegerl and Zohar2016), as is treatment of substance abuse, including alcohol misuse (Williams, Reference Williams1997). Other specific mental disorders should also be treated in their own ways; for example, use of lithium in bipolar disorder might help reduce suicidal behaviour in this group (Curran & Ravindran, Reference Curran and Ravindran2014; Zalsman et al. Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, van Heeringen, Arensman, Sarchiapone, Carli, Höschl, Barzilay, Balazs, Purebl, Kahn, Sáiz, Lipsicas, Bobes, Cozman, Hegerl and Zohar2016).

In emotionally unstable personality disorder, psychological therapies can prove very helpful in addressing suicidal behaviours, including adaptations of cognitive-behaviour therapy and dialectical-behaviour therapy (DBT). DBT is a challenging therapy but it can help reduce self-harm in certain conditions, including (but not limited to) personality disorders (Hawton et al. Reference Hawton, Witt, Taylor Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell, Hazell, Townsend and van Heeringen2016).

Interventions at the level of groups, communities and society

From a public health perspective, measures to limit access to means of self-harm are very important and effective (Zalsman et al. Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, van Heeringen, Arensman, Sarchiapone, Carli, Höschl, Barzilay, Balazs, Purebl, Kahn, Sáiz, Lipsicas, Bobes, Cozman, Hegerl and Zohar2016). Regulations governing paracetamol sales are an excellent example. In the United Kingdom, legislation restricting pack sizes of paracetamol and salicylate was introduced in 1998 and the following year saw a 21% reduction in the number of deaths from paracetamol poisoning and a 48% reduction in deaths from salicylates (Hawton et al. Reference Hawton, Townsend, Deeks, Appleby, Gunnell, Bennewith and Cooper2001). Over the following 11¼ years, deaths from paracetamol overdose decreased by 43% in England and Wales (Hawton et al. Reference Hawton, Bergen, Simkin, Dodd, Pocock, Bernal, Gunnell and Kapur2013), making paracetamol pack size legislation one of the most effective public health interventions in all of medicine.

Ireland experienced similar problems with paracetamol overdoses (Sheehan, Reference Sheehan2001) with 82% of people citing ease of availability as a reason for taking paracetamol (O’Rourke et al. Reference O’Rourke, Garland and McCormick2002). The introduction of similar legislation in Ireland in 2001 was duly followed by a significant reduction in the number of tablets taken in paracetamol overdoses (Donohoe et al. Reference Donohoe, Walsh and Tracey2006). It is, of course, imperative that these regulations are enforced in order to maintain this benefit into the future (Ní Mhaoláin et al. Reference Ní Mhaoláin, Davoren, Kelly, Breen and Casey2007; Ní Mhaoláin et al. Reference Ní Mhaoláin, Kelly, Breen and Casey2009). Placing barriers at known suicide locations (e.g. certain bridges) is another effective method for deterring self-harm and suicide, as a significant number of people who are deterred or delayed in this fashion will re-consider their suicidal thoughts and many will not proceed to find other means of self-harm (Bennewith et al. Reference Bennewith, Nowers and Gunnell2007; Zalsman et al. Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, van Heeringen, Arensman, Sarchiapone, Carli, Höschl, Barzilay, Balazs, Purebl, Kahn, Sáiz, Lipsicas, Bobes, Cozman, Hegerl and Zohar2016).

Against this background, a new suicide prevention strategy was launched in 2015 by Healthy Ireland, Department of Health, HSE, NOSP (2015), titled ‘Connecting for Life: Ireland’s National Strategy to Reduce Suicide, 2015–2020’. The strategy involves preventive and awareness-raising work with the population as a whole, supportive work with local communities, and targeted approaches for priority groups. The strategy proposes high-quality standards of practice across service delivery areas and – most importantly – an underpinning evaluation and research framework. In parallel, the budget for NOSP was increased from €3.7 million in 2010 to €11.5 million in 2016.

Addressing the psychiatric, psychological and emotional underpinnings of suicidal feelings is an essential element of care, complementing public health measures (such as limiting access to means). This is especially important among those presenting to Irish hospitals with self-harm, as we know that they are at especially high risk of further self-harm and suicide. In this context, Murray (Reference Murray2016) notes the profound difficulties with estimating suicide risk and recommends that assessment and management of patients presenting with suicidal thoughts, feelings and behaviour should focus on reducing or tolerating emotional pain.

The reduction of distress in such situations is also likely also to require approaches rooted outside of core mental health services, such as addressing alcohol problems and other addictions (see above), reducing homelessness, reforming the criminal justice system, and improving access to social care. The HRB review of suicide interventions notes that evidence for psychosocial interventions is very mixed (Dillon et al. Reference Dillon, Guiney, Farragher, McCarthy and Long2015), but, on the other hand, it is exceptionally difficult to generate individual-level evidence that addressing homelessness, reforming the criminal justice system, or improving social services at societal level definitely impacts on rates of self-harm or suicide. It is nonetheless likely that they do.

The high rates of self-harm and suicide in young people require particular, coordinated psychological, social and educational supports for young people in communities, schools and colleges, and through social media. Zalsman et al. (Reference Zalsman, Hawton, Wasserman, van Heeringen, Arensman, Sarchiapone, Carli, Höschl, Barzilay, Balazs, Purebl, Kahn, Sáiz, Lipsicas, Bobes, Cozman, Hegerl and Zohar2016), in their systematic review of evidence for various suicide prevention strategies, note that school-based awareness programmes have been shown to significantly reduce suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. Consistent with this, ‘Connecting for Life: Ireland’s National Strategy to Reduce Suicide, 2015–2020’ supports ‘a whole-school approach to mental health promotion’ and integrating ‘suicide prevention into relevant sports policies and programmes for those who are vulnerable and at increased risk of suicide within the sporting community’.

‘Connecting for Life’ also takes account of ‘evidence on social media and social marketing strategies, language and stigma reduction’, and while the policy notes that ‘internet sites and social media have been implicated in both inciting and facilitating suicidal behaviour’, the potential for social media to make a positive contribution to suicide prevention also requires further research given the growing power of social media in many people’s lives.

Overall, in terms of prevention, a multi-level, multi-strand approach appears most likely to help, applied individually to each particular person who presents, following careful individual assessment. At present, according to the National Self-Harm Registry Ireland Annual Report 2015, 73% of people who present to Irish hospitals with self-harm receive an assessment in the emergency department (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Arensman, Dillon, Corcoran, Williamson and Perry2016). Approximately 23% are admitted to a general hospital, 9% are admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit, 1% do not permit admission, 13% leave before a recommendation is made and 55% are not admitted. The more lethal the method of self-harm used, the greater the likelihood of psychiatric admission.

Follow-up assessments, support for families, communication with GPs, good outpatient mental health care and involvement of dedicated self-harm nurses are all essential elements in care plans following self-harm. Media guidelines on reporting suicide have been produced by the Irish Association of Suicidology and the Samaritans (2013) in order to minimise further harm and reduce the possibility of copycat acts. The HSE (2011) has also produced clear guidelines on responding to suicide ‘clusters’, focussed on pro-active response plans in local health areas.

Despite such increased public and professional discussion, however, much remains to be done to provide effective, coordinated support to those at risk of suicide and those bereaved. In 2016, it was estimated that there were up to 300 different groups providing support for those at risk (O’Regan, Reference O’Regan2016). Clearly, a coordinated, effective and compassionate approach is needed, linking community and state resources with each other in order to optimise efforts to address this problem which has been a long-standing issue in the history of psychiatry in Ireland, as has been the case elsewhere (Kelly, Reference Kelly2016).

Grief following suicide is especially complex and difficult. Families often experience shock, loss, guilt, shame, anger and many other emotions. They may not feel able to identify with families who are bereaved in other ways. They may feel isolated and that there a lack of understanding. Pieta House (www.pieta.ie) offers support, both for those bereaved and those who are feeling suicidal. Patient suicide also affects psychiatrists and other health care staff and can be a substantial source of stress (Foley & Kelly, Reference Foley and Kelly2007).

Conclusions

The fact that the Irish suicide rate is falling is a very welcome development. Even so, suicide and self-harm remain substantial societal problems, especially among particular groups. It is not possible to predict suicide at the level of the individual but good primary care, good secondary mental health care and good social care all likely reduce rates of self-harm and suicide. In terms of targeted interventions, public health measures, such as paracetamol pack size regulations, have the best evidence base to support them.

Despite increased public and professional discussion in recent years, much remains to be done to provide effective, coordinated support to those at risk of self-harm and suicide, and those bereaved. A coordinated, effective and compassionate approach is needed.

Acknowledgements

The author is very grateful to the editor and reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

This paper did not involve human or animal experimentation. The author asserts that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The author asserts that ethical approval for the publication of this paper was not required by his local Ethics Committee.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.