CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 67-year-old male presents to the emergency department (ED) in respiratory distress secondary to pneumonia. His oxygen saturation is 86% on a nonrebreather, respiratory rate is 32 respirations/minute, blood pressure 147/72 mmHg, heart rate 121 beats/minute, and temperature is 38.7° Celsius. The decision is made to intubate the patient. Fentanyl and propofol are used for analgesia and sedation, and rocuronium is used for paralysis. Using video laryngoscopy, the patient is successfully intubated, and now the ED team is awaiting your orders for the postintubation sedation care of this patient.

KEY CLINICAL QUESTIONS

- 1.

What are the components of postintubation sedation?

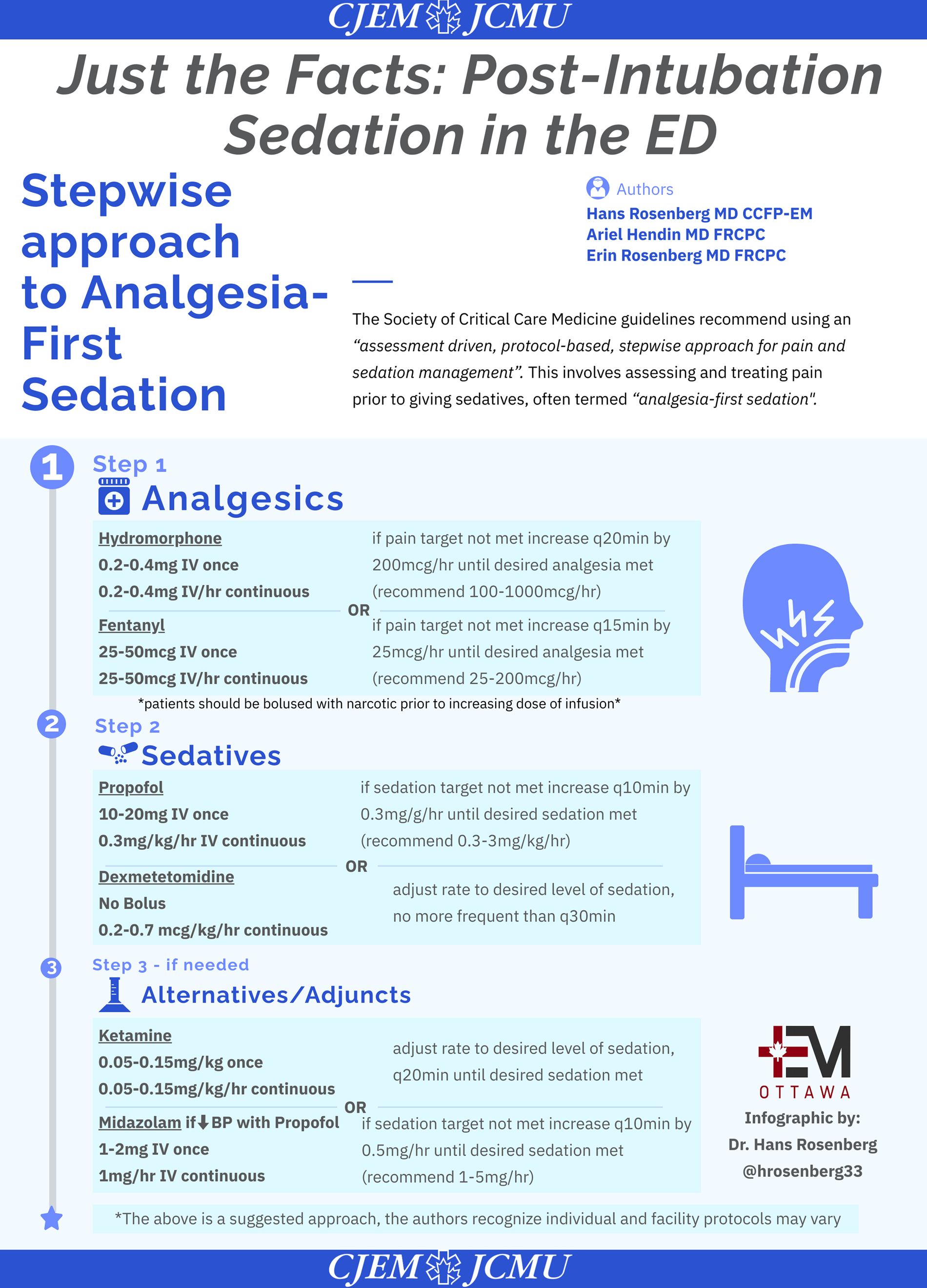

Mechanically ventilated patients commonly experience both pain and agitation. Pain can occur for a variety of reasons both at rest and with procedures. Undertreated pain can negatively affect patients in many ways, including causing cardiac instability, respiratory compromise, and immunosuppression. Sedatives are frequently required in intubated patients to manage anxiety/agitation; however, most sedatives do not have analgesic properties. The Society of Critical Care Medicine guidelines recommend using an “assessment driven, protocol-based, stepwise approach for pain and sedation management.” This involves assessing and treating pain before giving sedatives, often termed “analgesia-first sedation.”Reference Devlin, Skrobik and Gélinas1

- 2.

What percentage of patients receive postintubation sedation in the ED?

A key study by Bonomo et al. in 2008 showed 74% of ED patients (95% CI 65–82%) received no or inadequate anxiolysis postintubation, and 75% (66–83%) received no or inadequate analgesia.Reference Bonomo, Butler, Lindsell and Venkat2 Further studies since that time have shown significant improvements, however, in a retrospective cohort analysis of over 1 million patients in the United States undergoing intubation, 42.6% of patients who survived to admission or transfer still did not receive postintubation sedation (including benzodiazepines, opioids, and other sedatives).Reference Weingart, Carlson, Callaway, Frank and Wang3

- 3.

Why is it important for emergency physicians to provide appropriate postintubation sedation?

Due to the realities of overcrowded EDs and limited medical hospital capacity, intubated patients may spend significant amounts of time in the ED. Therefore, having a postintubation sedation approach for all patients is critical. Little or no sedation will result in a patient who is experiencing pain and anxiety, particularly if neuromuscular blockade is still present while sedating medications administered during intubation have been cleared. Up to one in five ED patients who receives long-acting neuromuscular blockade for intubation does not receive sedation, which can lead to tachycardia, hypertension, and patient recall of events.Reference Chong, Sandefur and Rimmelin4 It can be challenging to assess whether a paralyzed patient is adequately sedated based on clinical assessment alone, as signs such as lacrimation, diaphoresis, and tachycardia are unreliable. Train-of-four or bispectral index monitoring, while widely used in anesthesia and in critical care for patients who receive neuromuscular blockade, are not available or commonly used in the ED.Reference Murray, DeBlock and Erstad5 As such, patients receiving long-acting neuromuscular blockade should be administered sedation until the medication is expected to have worn off. After this time, avoiding deep sedation is also important. In one ED retrospective cohort study, two-thirds of patients were deeply sedated, and this was associated with increased time on a ventilator and mortality.Reference Stephens, Ablordeppey and Drewry6

- 4.

What agents should we use for postintubation sedation and analgesia?

Opioids (e.g., hydromorphone, fentanyl, and morphine) are the most commonly used agents for pain management in critical care; however, they are associated with delirium, ileus, respiratory depression, and can prolong intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay. Due to these negative effects, multimodal analgesia with nonopioid agents, such as acetaminophen, ketamine, and neuropathic agents, is recommended to minimize opioid use (Figure 1). There is no single preferred opioid, and availability/center-specific preferences will dictate what is used. Recommendations for sedative use have changed over the past several years, and nonbenzodiazepine sedatives are the preferred option, including propofol and dexmedetomidine.Reference Devlin, Skrobik and Gélinas1 A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that benzodiazepine-based sedative regimens are associated with longer ICU length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation compared with propofol or dexmedetomidine-based regimens.Reference Fraser, Devlin and Worby7

- 5.

How can we measure pain and sedation in intubated patients to adjust analgesic and sedative doses?

Critically ill patients are often unable to easily communicate due to altered mental status, mechanical ventilation, and other invasive devices that can limit mobility and speech. Analgesics and sedatives all have side effects, and so the desire is always to use the lowest possible dose for the shortest amount of time. In keeping with the Society of Critical Care Medicine recommendation for an assessment-driven approach to pain and sedation management, there is a clear need for validated pain and sedation assessment tools. The gold standard for pain assessment is patient self-report using the numeric rating scale from 0 to 10; however, intubated patients are not always able to do this. Two pain assessment tools developed for and validated in critically ill mechanically ventilated patients are the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool and the Behavioural Pain Scale. Sedation can be assessed using either the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale or the Sedation-Agitation Scale. A light level of sedation is the desired goal, with patients who are ideally alert and calm, or mildly sedated but easily roused. Light sedation is associated with shorter duration of mechanical ventilation and reduced rate of tracheostomy.Reference Devlin, Skrobik and Gélinas1

CASE RESOLUTION

The patient is started on a fentanyl infusion at a set rate, which is then titrated using the Behavioural Pain Scale once rocuroniumhas worn off. In addition, a propofol infusion is started and titrated using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale. The patient appears comfortable, can respond to commands, and remains hemodynamically stable. The intensive care team arrives in the ED, and the patient is safely transported to the ICU.

KEY POINTS

1. Intubated patients frequently experience both pain and anxiety, which should be treated first with analgesia, and then with sedatives if required.

2. While emergency physicians are now more cognizant of the need to provide analgesia and sedation post intubation, some patients still are under-treated in the ED.

3. Inadequate sedation as well as very deep sedation both have adverse physiologic consequences and negatively impact patient outcomes.

4. Emergency physicians must ensure that patients receiving long-acting neuromuscular blockade are administered sedation until the paralytic is expected to have worn off.

5. Opioids should be used along with multi-modal analgesia to manage pain. Propofol is preferred for sedation over benzodiazepines, which have been shown to prolong duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay.

6. Validated scales for assessing pain and degree of sedation in the intubated patient should be used to titrate medication dosing.

Competing interests

None declared.