Introduction

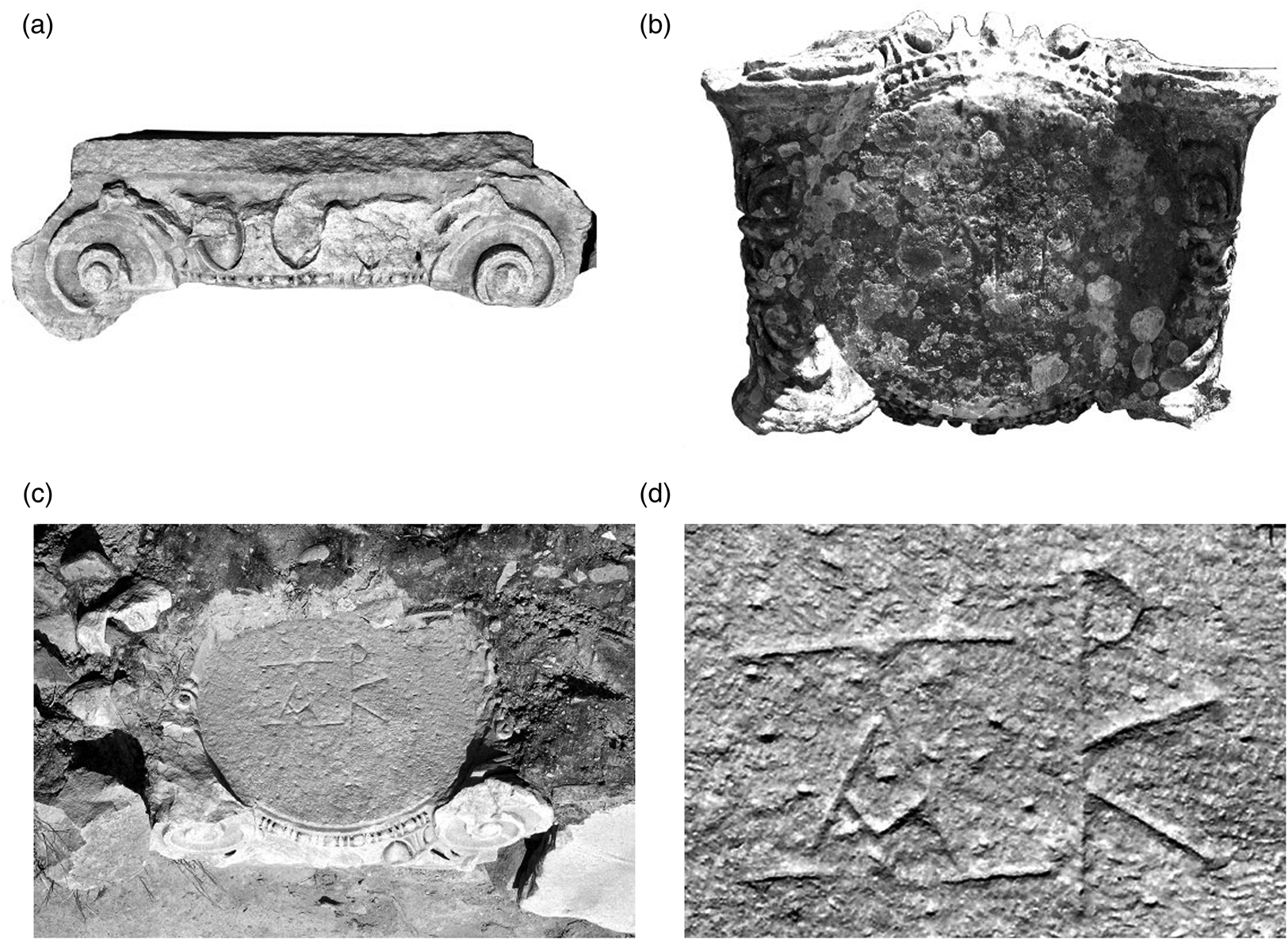

In the late 1960s, in the northern part of the Late Roman baths at Kom el-Dikka in Alexandria, an Ionic capital of bluish-white marble was found (Field Reg. 60, h. 0.245 m, diam. 0.60 m, w. 0.88 m) which had an abbreviated inscription, ΦΛ ΑΝΤ, carved on its underside (Figs. 1 and 2a–b).Footnote 1 The phi is engraved in a decorative ligature with the lambda, which forms the vertical bottom line of the phi. The nu and tau also form a ligature. This text was interpreted by the first editor, as a name, such as Φλ(άουϊος) Ἀντ(ωνῖνος) or Φλ(άουϊος) Ἀντ(ώνιος).Footnote 2 Another very similar Ionic capital of grayish-white marble, without any inscription, was also found in the area of the baths (Field Reg 15, h. 0.21 m, diam. 0.585 m, w. 0.88 m; Fig. 3),Footnote 3 as was half of a third capital (Field Reg. 108, h. 0.25 m, diam. ca. 0.5 m, Fig. 4) on which part of a mark like that on the first capital is preserved on the underside; in this case, only the letter Φ is preserved.Footnote 4 These Ionic capitals, with their distinctive Ionic kyma and pulvini, follow late Hellenistic models, but certain minor decorative details and the type of marble convinced Patrizio Pensabene that they should be dated to between the 1st and the early 2nd c. CE and interpreted as imports from Asia Minor reused in the later baths.Footnote 5

Fig. 1. Reused Ionic capital, Field Reg. 60, found in the baths at Kom el-Dikka, Alexandria. (Courtesy of the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archaeology; G. Majcherek.)

Fig. 2. (a) Underside of the Ionic capital Field Reg. 60 with the inscription ΦΛ ΑΝΤ, found in the baths at Kom el-Dikka, Alexandria. (Łukaszewicz Reference Łukaszewicz1990, pl. IIa; courtesy of Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH.) (b) Drawing of the inscription ΦΛ ΑΝΤ. (A. Kordas.)

Fig. 3. Reused Ionic capital, Field Reg. 15, found in the baths at Kom el-Dikka, Alexandria. (Courtesy of the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archaeology; E. Kulicka.)

Fig. 4. Drawing of the Ionic capital, Field Reg. 108, probably with a fragment of the mark ΦΛ ΑΝΤ, although only one letter Φ is preserved. Found in the baths at Kom el-Dikka, Alexandria. (Courtesy of the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences; K. Kamiński.)

There are many possibilities regarding the identity of this Flavius Αnt(- - -?), and the editio princeps of the text left this question unanswered. The inscribed mark itself has since been interpreted as a “proprietor's mark,” indicating that the element, bought from a “dismantled building,” was “a private contribution to the building of the thermae.”Footnote 6 However, from the beginning of the 4th c. CE onwards, as a consequence of Constantine's victory over Licinius in 324 CE, the name Flavius, which was the emperor's gentilicium, was often assumed by provincial governors, members of their officia, and officials or prominent dignitaries, soldiers and veterans, and especially decurions, as well as curatores civitatis.Footnote 7 Thus, it became a status marker for a person who bore the name. An important conclusion results from this observation: the name Flavius engraved on the Ionic capitals must have belonged to a high-ranking civilian or military imperial official.

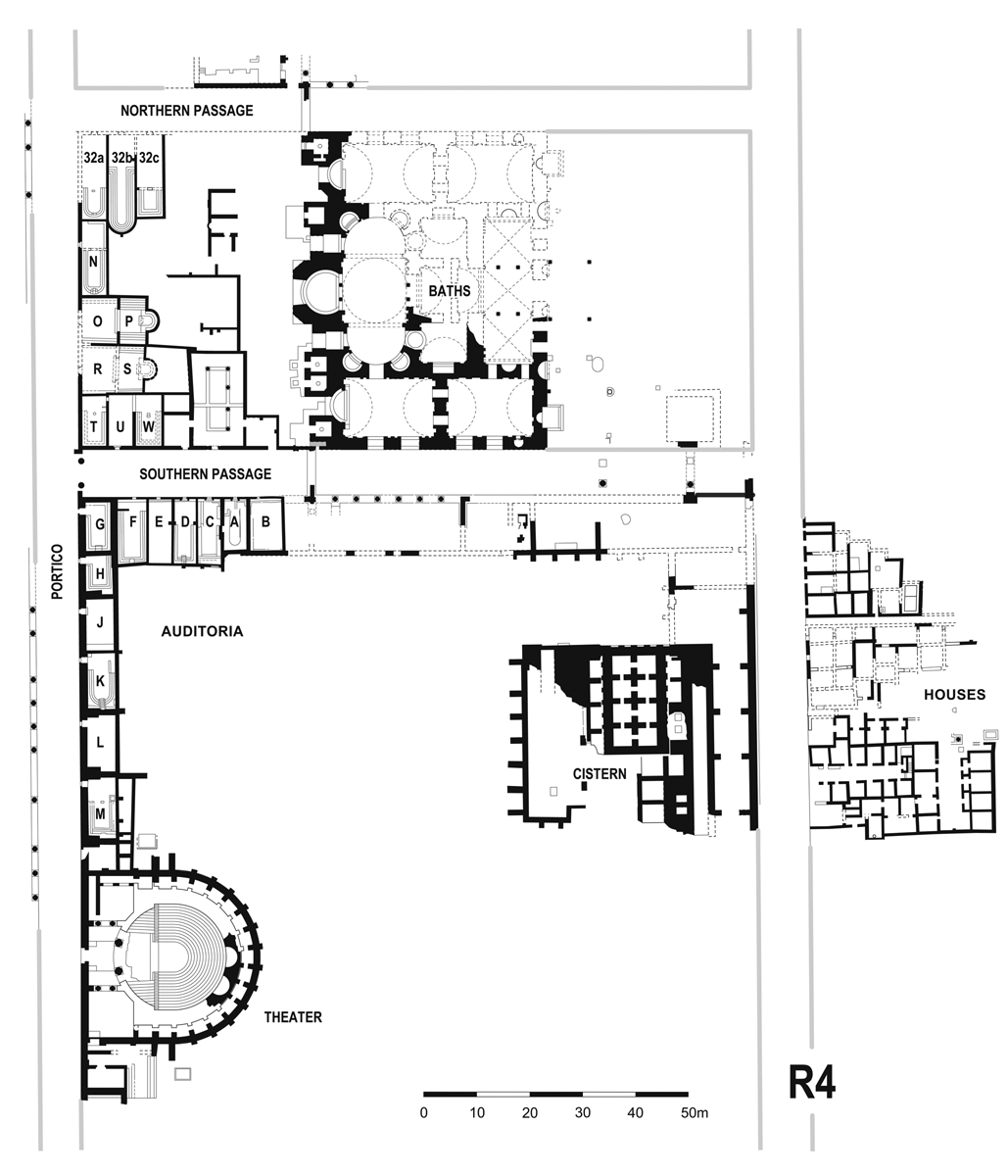

Archaeological evidence of the baths

As for the chronology of the baths at Kom el-Dikka, the moment of their foundation is uncertain. During excavations, no relevant inscription was found which would help date the construction or identify its founder. Furthermore, none of the written sources describing Alexandria's baths contain sufficient details to permit a definite identification of the baths at Kom el-Dikka.Footnote 8 The insula of the baths (Fig. 5) was formerly a residential quarter containing wealthy urban houses dated to between the 1st and 2nd c. CE,Footnote 9 which were destroyed at the end of the 3rd c. CE.Footnote 10 Later, the whole urban block was completely reorganized and the villas built over by a public complex including the baths.Footnote 11

Fig. 5. Plan of the architectural complexes discovered at Kom el-Dikka in Alexandria. (Courtesy of the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archaeology; drawing by W. Kołątaj, A. Pisarzewski, and D. Tarara.)

Wojciech Kołątaj, who excavated the baths, argued that the decision to construct them was made in the reign of Gratian, on the basis of a coin found in a trial pit adjacent to the remains of the structure's southern exterior wall; the coin was within a layer containing fragmented ceramics, including terra sigillata and lamps dated to between the 2nd and 4th c. CE.Footnote 12 This layer, a leveling fill over the earlier urban villas, was interpreted as concurrent with the first phase of the construction of the public buildings in the insula. Kołątaj connected the decision to construct the baths with the tsunami of 365 CE. However, it remains possible that the construction of public buildings in this area could have already been underway in the first half of the 4th c CE.Footnote 13 In support of this hypothesis, in the northeastern corner of the baths complex a huge limestone block was found (Fig. 6) with remnants of two extremely big letters TA, which suggest that it was a monumental inscription for a public building.Footnote 14 A review of imperial names for a reconstruction of this inscription pointed to Constantine, Constantius, or Constans as the only possibilities, and therefore either the Constantinian or post-Constantinian period could be considered a viable date for the construction of the baths.Footnote 15

Fig. 6. Huge limestone block found in the northeastern corner of the baths complex, with remnants of two extremely big letters: TA. (Łukaszewicz Reference Łukaszewicz1990, pl. IIIa; courtesy of Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH.)

The baths were restored or rebuilt multiple times following their initial construction. Exploration of the pavements of the baths indicated at least two reconstructions. The find of coin, an issue of Carthage dated to the years 395–425 CE,Footnote 16 provides the most authoritative terminus post quem for the first of these rebuildings. The second is dated by a coin of Mauricius Tiberius of 582–602 CE, which was found in the bedding of the latest pavement. Kołątaj was inclined to date the first rebuilding to the first half of the 5th c. CE and place the second rebuilding after the earthquake of 535 CE.Footnote 17 In sum, the baths had three main phases and, due to the extent of the alterations made in the second and third of these, it is impossible to reconstruct the exact architectural decoration of the first phase.

A range of indicators suggest that these baths were probably funded by the emperor. This is suggested, in part, by their size and symmetrical design. Their architectural characteristics and monumental scale are quite different from the Mareotic group of baths in the region of Alexandria and from other Egyptian regional baths. For this reason they were assigned by Thibaud Fournet and Bérangère Redon to a separate group, the so-called Imperial baths, which reproduced, or attempted to reproduce, the gigantic baths built in Rome during the Imperial period.Footnote 18 They assume that baths of this type were most probably built on the initiative or with the financial support of the emperor. Indeed, at Kom el-Dikka it is hard to imagine that anyone other than the emperor or his local representative could have authorized such a large-scale reorganization of the site and demolition of existing houses at this date.Footnote 19

Identification of ΦΛ ΑΝΤ

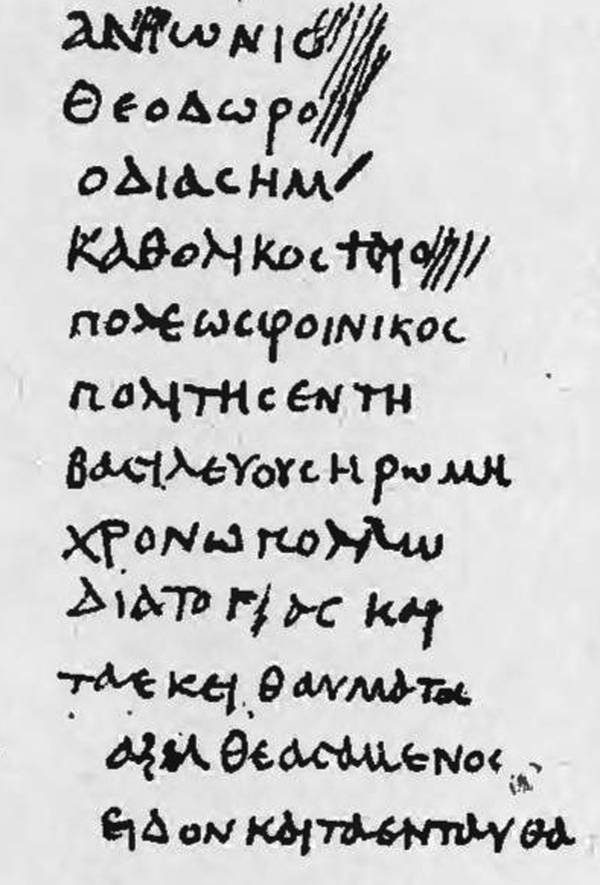

The best evidence for who precisely was responsible for the reorganization of the Kom el-Dikka site and the construction of the baths is provided by the inscribed mark on the Ionic capital. The name Flavius on these capitals suggests that this individual was a high imperial official. The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire lists only five people of high rank whose names could be abbreviated as Fl. Ant. Only one of these held the highest office in Egypt – that of the prefect of Egypt – and this person seems worthy of further consideration in the context of the construction of the baths.Footnote 20 This individual, Flavius Antonius Theodorus,Footnote 21 is mentioned three times in a papyrus (Fig. 7) and described there as prefect of Egypt – ὁ διασημότατος ἔπαρχος τῆς Αἰγύπτου – in a petition regarding a dispute over some property.Footnote 22 The document is dated to March 28, 338 CE. He also is mentioned as prefect of Egypt in a dating formula of a letter by a bishop of Alexandria, Athanasius: “For 338. Coss. Ursus and Polemius; Præf. the same Theodorus, of Heliopolis, and of the Catholics. After him, for the second year, Philagrius; Indict. XI; Easter-day, VII Kal. Ap. XXX Phamenoth; Moon 18 1/2; æra Dioclet. 54.” Footnote 23 Thanks to the index of Athanasius, Fest. Ind. s.a. 338, this is dated precisely to March 26, 388 CE. We know that the Flavius Philagrius mentioned in the formula was the preceding prefect of Egypt, between 335 and 337 CE, and that Constantius II reappointed him to the same office for the years 338–40 CE.Footnote 24

Fig. 7. POxy 67, the beginning of line 8 with the name of Φλαϋιος Ἀντώνιος Θɛόδωρος. (© British Library Board, Papyrus 754(A).)

Flavius Antonius Theodorus is also known from two dipinti painted in the tomb of Ramesses VI in the Valley of the Kings in Thebes. In the first he presented himself as Antonius Theodorus (Fig. 8),Footnote 25 while in the second he was described by another person simply as Theodorus (Fig. 9).Footnote 26 In both dipinti, he is defined as καθολικός (rationalis), but the first includes other information about his origin. To judge from this text it is clear that Flavius Antonius Theodorus was a native of the city of Heliopolis (Baalbek) in the province of Syria-Phoenicia. Prior to 335 CE,Footnote 27 he had served as a rationalis in Egypt, and undoubtedly while holding this office he had a chance to gain experience in central financial administration, which was required for a future prefect.Footnote 28 While in post, he traveled around Egypt and left two commemorative dipinti in Thebes. From the letter of Athanasius it may be inferred that in both 337 and 338 CE he served as prefect of Egypt, and the papyrus discussed above confirms this.

Fig. 8. Drawing of the dipinto mentioning Ἀντώνιο[ς] Θɛοδώρο[ς] found in a corridor of the tomb of Ramesses VI (KV9) in the Valley of the Kings in Thebes. (Baillet Reference Baillet1926, pl. 48, no. 1249.)

Fig. 9. Drawing of the dipinto mentioning καθολικὸς Θɛόδορος found in a corridor of the tomb of Ramesses VI (KV9) in the Valley of the Kings in Thebes. (Baillet Reference Baillet1926, pl. 42, no. 1285.)

The form of the most complete of inscriptions from the baths at Kom el-Dikka adds further support to the argument that the text refers to the prefect. The decorative ligatures and harmonious letter composition of the monogram suggest that it was designed for the needs of the officium of the prefect, rather than for a private person who had merely bought a series of capitals on the secondhand market for a donation to a public building, which is the interpretation proposed by the editor princeps.Footnote 29 As the texts listed above show, Flavius Antonius Theodorus signed his name or was described in different ways (as Flavius Antonius Theodorus, Antonius Theodorus, or just Theodorus). Although the inscription from Kom el-Dikka does not include the name Theodorus, the combination of the abbreviated name Flavius, which emphasized his highest rank, and the name Antonius would seem sufficient to identify this as the prefect's monogram. Hypothetically, the mark consisting only of his name, Theodorus, would require additional clarification to make it clear that the inscription referred to the ἔπαρχος. In this case, the text would have ended up longer and would have been more laborious to engrave than a three-letter monogram.Footnote 30

Other examples of similar marks

Another argument for this inscription being the name of the prefect is provided by examples of inscribed marks on architectural blocks that refer to similar state interventions in other parts of the Roman Empire. The group of marks gathered by Giulia Marsili and labeled “marchi di stoccaggio” includes inscriptions placed on architectural elements at the time of their storage, often carved at the point of dismantling of earlier structures or following selection and purchase by a customer.Footnote 31 At a regulatory level, the appropriation of spolia for both public and private building works had to be authorized,Footnote 32 and we can observe this phenomenon in various inscribed marks with the names of people holding the highest offices.

A notable example is the inscribed mark PAT DECI preserved on the column drums of the peristyle of the temple of Mars Ultor in Rome.Footnote 33 These texts have been dated paleographically to Late Antiquity and linked to the noble family of the Caecina Deci, and more specifically to Caecina Mavortius Basilius Decius, praefectus urbi, praefectus praetorio, and consul in 486 CE.Footnote 34 According to a decree issued under Theodoric (r. 491–527 CE), this Decius owned a domus near the Porticus Curva – between the Forum of Augustus, where the temple of Mars Ultor was situated, and the Temple of Minerva in the Forum of Nerva – and applied for an extension of his house toward it. The marks PAT DECI could be related to this specific construction activity and provide evidence for direct purchase of the marble spolia from the state by a high-ranked person.Footnote 35

Further significant examples of inscribed marks of this sort have been found in Ostia, on both new marble column shafts and examples from dismantled earlier buildings.Footnote 36 These column shafts in cipollino and Proconnesian marble, of equal diameters, found together with octagonal plinths and Corinthian capitals, bear the marks DNGF (five items) and FLSTL (three items) (Fig. 10). These abbreviations have been reconstructed as D(omini) N(ostri) G(ratiani) F(elicis) and Fl(avii) St(i)l(ichonis).Footnote 37 It has been proposed that the marble elements must have been intended for a single building project, but for whatever reason never used. This is evidenced by the partial finishing of the elements and the lack of dowel holes needed to actually erect them. The inscriptions with the names of both the emperor Gratian (r. 367–83) and Flavius Stilicho – illustrissimo viro, twice consul in 400 and 405 CE, and magister militium, whose engagement in public construction is well known – would suggest that these valuable marble elements were ordered by the imperial household but that supervision of the project was carried out by a member of the aristocracy.Footnote 38 Also from Ostia are the bases, column shafts, and Ionic capitals found in a deposit in the courtyard of the collegiate temple of the Fabri Navales after its disassembly.Footnote 39 At least five elements are inscribed with the name VOLUSIANI V(iri) C(larissimi), who has been identified as Rufus Antonius Agrypnius Volusianus,Footnote 40 praefectus pretorio Italiae et Africane in 428–29 CE and praefectus urbi in 417–18 CE, rather than his ancestor C. Ceionius Rufus Volusianus Lampiadus,Footnote 41 also praefectus praetorio and praefectus urbi between 355 and 365 CE.Footnote 42

Fig. 10. Marble column shafts with the inscriptions FLSTL and DNGF, found in Ostia, now in the Palazzo Cesarini Sforza in Rome. (Marsili Reference Marsili2019, 117, fig. 64; courtesy of G. Marsili.)

The presence of individuals who held the role of praefectus urbi in these texts is notable. From the eastern Empire, we can point to a further example: this is the delivery mark on a column shaft of Docimian marble found in Constantinople in the Hagia Sophia lapidarium, which includes the text τοῦ ἐπάρχου (Fig. 11).Footnote 43 This indicates that the column was meant for a building commissioned by an urban prefect.Footnote 44 We know from other sources that construction activity and responsibility for control of building materials in both Rome and Constantinople was part of the duties of the praefectus urbi.Footnote 45 To judge from this evidence, it is reasonable to assume that the presence of the prefect of Egypt's name in marks inscribed on architectural elements from Alexandria shows that imperial construction activity fell within his range of his duties.

Fig. 11. Delivery mark τοῦ ἐπάρχου carved on a column shaft in Docimian marble, Hagia Sophia Museum. (Marsili Reference Marsili2019, 97, fig. 50; courtesy of G. Marsili.)

Although not relating to a prefect, another example from Constantinople shows that inscribed names were used to designate batches of material to projects overseen by high level officials. These are the inscriptions reading ΑΝΤΙΟΧΟΥ ΠΡΕΠΟCΙΤΟΥ, which were found on marble column bases in a building close to the hippodrome. They have been interpreted as referring to Antiochus, praepositus sacri cubiculi under Theodosius II, leading to the identification of the unearthed palatial structure as the Palace of Antiochus.Footnote 46

One final example of an inscribed mark, also from the eastern Empire, is worth mentioning here. This is the word ΠΡΟΒΑΤ, carved on eleven blocks reused on the northern façade of the outer wall of the Bouleuterion in Aphrodisias in Caria, which has been interpreted as Greek transliteration of a Latin past participle (probat), indicating an operation of control and official approval of reuse. It has been argued that these marks were added to blocks stored in building yards in order to confirm their acquisition by the government.Footnote 47 In her analysis of an inventory of columns preserved on papyrus, Arietta Papaconstantinou noted that there was a “clear separation between public and private property, and transferring building materials from one to the other was not straightforward, but subject to a formalized transaction.”Footnote 48 Even if part of the dismantled material did not end up being reused in another public building, these kinds of marks on them would indicate that they were to be sold for the benefit of the imperial treasury.

During the reign of either Constantine or Constantius II, legislation also guaranteed that revenues generated by civic property were confiscated by the fiscus.Footnote 49 Efforts made by local authorities to recover the city's property by handing over building material to municipal construction supervisors (ἐπιμɛληταί, curatores operum publicorum) are evidenced by the edict issued by a proconsul of Achaia, Publius Ampelius.Footnote 50 Alongside a range of other imperial edicts,Footnote 51 all of this indicates that the Ionic capitals at Kom el-Dikka were probably labeled with the name of the prefect of Egypt just after the dismantling of the structure to which they previously belonged. The marks identified them as originating from a ruined public building and so public property, which meant that they should be reused in another public construction.

There is one more explanation for the marks ΦΛ ΑΝΤ, which should be at least be touched upon here: the possibility that they indicate the identity of the workshop originally responsible for carving the capitals. As noted above, the Ionic capitals have been interpreted as imports from Asia Minor dated to the 1st or early 2nd c. CE.Footnote 52 An interesting possible parallel could be the two Ionic capitals in white marble found at Gortyn (h. 0.2 m, diam. 0.52 m, w. 0.77 m), which are inscribed with the mark AΡΚ on the underside (Fig. 12). They have also been interpreted as works produced by craftsmen from Asia Minor and dated to the second half of the 2nd c. CE.Footnote 53 Despite the general similarity of these two Ionic capitals to the examples from Alexandria, and the fact that their inscriptions are also located on their undersides, however, a broader analysis of the inscribed marks of workshops from the Early Byzantine period shows that they usually refer to the name of a single producer or the supervisor responsible for the delivery of the product;Footnote 54 these marks also usually consist of one to five letters or a monogram, generally linked to that person's proper name.Footnote 55 It seems highly unlikely that the noble name Flavius would refer to the owner of a stonemason's workshop or a contractor responsible for delivery. Moreover, paleographic analysis of the letters of the ΦΛ ΑΝΤ text suggest that it was added in the Late Roman period, long after the capitals were carved. The practice of high officials assuming the name of Flavius after 324 CE seems to corroborate this dating.

Fig. 12. Two Ionic capitals carved by workers from Asia Minor with stonemason's mark AΡΚ. Their original use was assigned to the first phase of the nymphaeum in Gortyn. (Livadotti Reference Livadotti, Lippolis, Caliò and Giatti2019, 328, fig. 79 a–f; courtesy and copyright of the Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Atene.)

Finally, examples of analogous marks carved on various construction elements at Aphrodisias have recently been interpreted by Angelos Chaniotis.Footnote 56 He has connected the abbreviations ΑΛΒ, ΑΛΒΙΝ (on eight plaques of the pavement of the West Stoa in the Place of Palms), ΑΝΠΕ (on the surface of three bases from the Sebasteion), and ΚΩ (on six blocks used for construction of Late Antique city walls) to the names of sponsors of building projects mentioned in other inscriptions: Albinus, sponsor of the West Stoa;Footnote 57 Flavius Ampelius, a well-known overseer of various building activities in the second half of the 5th c. CE;Footnote 58 and the governor Flavius Constantius, who oversaw the building of the city walls.Footnote 59 It is worth emphasizing that none of these abbreviated texts contain a reference to the dignity, rank, or title of these men. Nevertheless, Chaniotis firmly rules out interpreting these marks as naming the owners of workshops or leaseholders of quarries, and proposes instead that these texts should be read as “for (the project) of Albinus, Ampelius, or Constantius,” or, more likely, “acquired by or on behalf of,” because in many cases they were carved on recycled building material. I would argue that the marks on the Ionic capitals from the baths at Kom el-Dikka should be interpreted in exactly the same way.

The prefect of Egypt and the construction of public buildings

If the interpretation of the inscribed marks on the capitals outlined above is correct, it seems to indicate that the prefect was involved in the construction of the baths, presumably at the request of the emperor or with his blessing. With this in mind, what can we say about the prefect's duties relating to the construction of public buildings? These are difficult to determine precisely at the beginning of the 4th c. CE.Footnote 60 Certainly, he would have presided over a vast administrative bureaucracy centered in Alexandria and would have governed subordinate financial officers – such as the rationales, magistri privatae, procuratores privatae, procuratores monetae Alexandriae, censitores, and logistes – responsible for the finances and administration of particular towns.Footnote 61 A prefect would have exercised control over nearly every aspect of life in the province of Egypt. Therefore, it is possible that the control and approval of construction material in Alexandria, reclaimed from demolished structures, was also among the duties of this office. At the same time, based on the extant documentation, it is not possible to pinpoint the extent to which municipal authorities, as opposed to the prefect, oversaw public construction in this period in Egypt.Footnote 62 The situation in Alexandria presents particular challenges due to the lack of papyrological sources.

Three earlier documents from elsewhere in Egypt do offer some insight into the involvement of prefects with the construction of baths. A papyrus dated to 128 CE contains a letter from the prefect Flavius Titianus to the town of Oxyrhynchus and a building permit for a set of baths, which were to be financed from funds already collected.Footnote 63 Another papyrus, dated to 107 CE, provides a financial report for a project involving the reconstruction of baths and construction of a road, for which 16 talents were given by Herakleides, the strategos of Hermoupolis, while a further 70 talents were allocated by the prefect Vibius Maximus.Footnote 64 The document also states that these costs were to be covered by municipal funds previously collected for projects in another town. The third papyrus, dated to 306 CE, reveals that the prefect Clodius Culcianus instructed his subordinate official, the prytaneus, to allocate 50 talents from the town's funds to finance the baths and to cover other costs related to the prytaneia.Footnote 65 These examples show that the competences of a prefect included approval of decisions and allocation of funds for the construction of public baths. Owing to the imperial nature of the baths at Kom el-Dikka, in this case it seems more convincing that the funds for the construction project came from a special donation made to the city by an emperor rather than from municipal accounts.Footnote 66

In this context, one further official cannot be ignored: numerous papyrus sources show that the construction of public buildings in Egyptian metropoleis was entrusted to curators called either epimeletes or logistes.Footnote 67 Among the tasks overseen by these officials were securing construction sites, purchasing materials, sometimes even extraction of stones or cutting of trees, agreeing contracts with those carrying out the work, assessing construction costs, and reporting on expenses.Footnote 68 These officials, however, as is clear from a number of other texts, were overseers of building projects;Footnote 69 unlike the prefect they were not in charge of approving projects or allocating funds.

Finally, the sources certify that in the field of public works the prefects of Egypt had a certain tendency to neglect maintenance works in favor of new constructions.Footnote 70 The building of imperial baths at Alexandria and the wholescale reorganization of the greater part of the insula in which they were situated, were projects significant enough to match the competences and ambitions of the prefect of Egypt.

Contribution to the dating of the baths building

The interpretation of the inscribed mark ΦΛ ΑΝΤ as the name of the prefect of Egypt Flavius Antonius Theodorus has important implications for the dating of the Kom el-Dikka baths. This individual was appointed to the office of prefect by the emperor Constantine, probably at the beginning of 337 CE. He was then replaced in this role in 338 CE, under Constantius II.Footnote 71 During the short-term of his prefecture, on May 22, 337 CE, the reign of Constantine came to an end. It is highly unlikely that one of the heirs of Constantine would decide to reorganize this entire quarter in Alexandria in such a short time and begin the construction of the baths immediately following the death of his father.Footnote 72 Therefore, the hypothesis already proposed by Łukaszewicz on the basis of the archaeological evidence and the two preserved letters (TA) of the monumental inscription (Fig. 6) – that the construction of the baths at Kom el-Dikka was initiated upon the order of Constantine – becomes all the more convincing.Footnote 73 The construction of the baths would have started before the emperor's death and during the prefecture of Flavius Antonius Theodorus, which would mean that it was already underway in the first half of 337 CE.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Prof. Monika Rekowska (University of Warsaw), Prof. Grzegorz Majcherek (Director of Research at Kom el-Dikka, the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw), Prof. Adam Łajtar (University of Warsaw), and Prof. Angelos Chaniotis (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton), and my colleagues Dr. Paweł Nowakowski (University of Warsaw) and Dr. Ulf Weber (Independent Researcher) for their careful readings of this article and valuable comments; their positive impact on the overall quality of my research cannot be overstated. I also thank Maciej Talaga for the first-language proofreading of this paper.