The years following Nikos Skalkottas's return to Greece from Germany in 1933 is characterized by the composition of a greater number of more accessible, tonal works. This period coincides with the political turmoil of the Metaxas dictatorship,Footnote 1 the Greco-Italian War (1940–1), the Nazi occupation (1941–4, during which Skalkottas was briefly interned at a concentration camp), and the subsequent Civil War (1946–9) – a series of seismic events that played a crucial role in shaping the cultural landscape.Footnote 2 The practical motivations for a direction towards tonality have been previously discussed by Skalkottas's biographer Eva Mantzourani, among others.Footnote 3 Amid these sociopolitical upheavals, the composer's self-proclaimed efforts to establish a more accessible musical style, however, warrant scrutiny within the political climate of anti-fascist resistance. Centring on the period from 1941 to the composer's death in 1949 and focusing on the years between 1947 and 1949 when, as Mantzourani observes, ‘tonality predominated’,Footnote 4 this shift is comprehensively viewed through the lens of the impact of Socialist Realism in Greece for the first time. While I consider Skalkottas's general orientation towards tonality, I place particular emphasis on his Classical Symphony in A for wind orchestra, two harps, and lower strings composed in 1947 – a major work that continues to occupy a peripheral position in existing Greek and Anglophone scholarship on the composer.Footnote 5 Despite crucial evidence testifying to the impact of Socialist Realism on Greek music during this period of anti-fascist mobilization, this article identifies how its continued obscurity in existing scholarship reflects and sustains persistent Cold War cultural antagonisms.

Born in 1904 on the Greek island of Evia, Skalkottas began violin lessons with his uncle and later studied at the Athens Conservatoire, graduating in 1920 with the First Prize medal. A scholarship enabled him to pursue further training in Berlin, where he shifted his focus from performance to composition. In Berlin, he studied composition under Kurt Weill, Philipp Jarnach, and Robert Kahn, and from 1927 to 1933, he was a member of Arnold Schoenberg's composition masterclass.

Returning to Athens in 1933, Skalkottas was exempted from military service due to long-standing health issues. During the Nazi occupation, he performed with the Athens Radio, National Opera, and Athens State Orchestras. Despite taking on various other musical positions including teaching, transcribing, and accompanying, he, like many musicians, ‘suffered from deprivation’.Footnote 6 In May, he was imprisoned at the Haidari concentration camp for one and a half months. Skalkottas died in 1949 from an untreated hernia, two days before the birth of his second son with the pianist Maria Pangali.

While Skalkottas is the central subject of analysis, this does not suggest he was a mainstream composer who enjoyed widespread critical and commercial success. Despite some degree of heterogeneity within the prevailing Greek National School of Music, and although Skalkottas composed some music that aligned with its principles – such as his Greek Dances, which received a measure of success among Greek critics and audiences during his lifetime – his broadly conceived politico-musical activity, his position as a representative of the modernist avant-garde, his association with the popular yet controversial urban popular song tradition of rebetiko in the 1940s, and his introverted temperament likely collectively contributed to his alienation from the musical mainstream.Footnote 7 Ultimately, Skalkottas's works were never widely performed, and he remained a marginal figure during his lifetime.

Furthermore, there was nothing during this period that could constitute an official Socialist Realist musical movement in Greece.Footnote 8 Instead, in Athens, Socialist Realism was primarily disseminated from grassroots levels, through periodicals and magazines, as well as by individual artists and intellectuals. Indeed, while I identify Socialist Realist tendencies in Greece – in both the guerrilla songs of the Greek resistance and Alekos Xenos's narrative symphony – and situate Skalkottas's late tonal work within this context, I aim to shift these leftist repertoires away from reductive notions of Soviet vassalage or propaganda. I encourage their comprehension as expressions of a broader anti-fascist aesthetic that was informed by the lasting influence of the politics and perspectives of the popular front. In this way, the conceptual limits of Socialist Realism are broadened, and leftist politico-musical activity is aligned with a broad anti-fascist project, wherein support for Soviet communism is just one part of a far bigger story.

Signifying the rival aesthetic ideologies prized and promoted on either side of the Iron Curtain, Skalkottas's works have been partitioned into two primary categories. In one category were his twelve-tone and atonal works.Footnote 9 These were promoted in particular by the musicologist and composer John G. Papaioannou in relation to Skalkottas's association with the Second Viennese School. In the other category were Skalkottas's tonal and folkloristic works, promoted largely by those focused on rooting the composer within the first generation of the Greek National School of Music, primarily the eminent composer Manolis Kalomiris. Accordingly, the construction of Skalkottas's legacy after his death has been largely shaped by attempts to canonize the composer either as an autonomous modernist genius and descendant of the Second Viennese School, or as an avowed Greek national(ist) composer whose Greekness is expressed in his tonal and folklorist works.

While the competing perspectives of Kalomiris and Papaioannou played out in the twentieth century, they have had a pervasive impact on Skalkottas's contemporary reception, influencing which works are programmed and recorded, and how they are framed and understood. The anglophone foreword of the Greek Skalkottas Today conference, dedicated to the seventieth anniversary of the composer's death in 2019, illustrates that contemporary perceptions on the composer continue to be informed by the viewpoints of Kalomiris and Papaioannou:

Nikos Skalkottas is a representative composer of European music creation of the first half of the 20th century. His life and his work show the critical elements of contemporary music. He is a pioneer, innovative, inspired, and participant in the development of European music of his time as well as the development of the history of Greek music composition, while being secluded in his own art. He believed in himself, no matter the response of the audiences, he considered himself a European, but he also wanted to write many large scale works so that his country would have an important composer.Footnote 10

The privileging of Skalkottas's modernist works, which are seen as embodying the ‘critical elements of contemporary music’, the emphasis on European musical lineage, and the Romantic notions of artistic isolation expressed in this foreword reflect the perspectives of Kalomiris and Papaioannou and are representative of contemporary views and popular discourse surrounding the composer.

A series of recent articles also point in this direction, demonstrating how reductive narratives promoted by Kalomiris and Papaioannou still hold sway. An article in Classical Music Daily from 2019, for example, perpetuates the idea that Skalkottas's tonal compositions are nationalist works of lesser aesthetic value compared to those written in a modernist musical idiom. This perspective is evident in the use of the dismissive term ‘mere folkloricist’ to describe the composer's tonal works: ‘[Skalkottas was] principally known for his sets of Greek Dances – founded in folk music and showing the nationalistic side of this composer. But more than being a mere folkloricist, he had a thoroughly modernist side, from his studies in Germany.’Footnote 11

Discussing the ongoing digitization of Skalkottas's archive at the Lilian Voudouri Library, an article on the popular Greek website Culture Now describes the influence of ‘new musical currents’ that the composer encountered in Germany. There is no reference to the composer's tonal works. Indeed, the last years of Skalkottas's life, marked by a prevalence of tonal compositions and including politically engaged works, are vaguely described as being characteristically ‘introspective and dramatic’.Footnote 12

Efforts to curate and pigeonhole Skalkottas's music suggest strategic ‘position-takings’ that situate the composer's works within an ideological-artistic binary produced in the context of the Cold War.Footnote 13 Broadly speaking, they indicate a scholarly reluctance to confront composers’ messiness; their mobility between and across generic categories and binary historiographical frameworks which have featured prominently in Western musicological discourse. By addressing the scholarly reluctance to confront Skalkottas's fullness, complexity, and the social, cultural, and historical situatedness of his works, the necessity to re-examine Skalkottas as a ‘subject-in-community’ emerges.Footnote 14

Against the backdrop of political instability, dire living conditions, and the growing threat of fascism, the Communist International's (Comintern) mandate for the establishment of united fronts in the 1920s helped to promote unity between Greek communists, socialists, and other left-leaning individuals. As the political priorities of the left shifted away from the complete destruction of capitalism and the establishment of world communism, popular front strategies helped inspire a powerful anti-fascist movement that would play a crucial role during the resistance against Nazi occupation.Footnote 15 The emphasis on coalition-building inspired the protean diversity of the popular front as a unifying ideology – an ideology which, this article contends, would inform the reception of Socialist Realism in Greece.

Popular front politics were communicated to Greek artists and intellectuals, shared among the increasing number of unionized workers, and within teaching institutions, through various mechanisms. This included translated Soviet texts and articles published in several leftist newspapers and magazines, some of which directly appealed to cultural agents.Footnote 16 These mechanisms helped to motivate support for left-wing social and cultural practices and innovations that developed in accordance with the models exported from the Soviet Union, expressed in the concept of ‘The Cultural Front’.Footnote 17 It is within this context that this article suggests Greek artists appropriated and interpreted the qualities of Socialist Realism to engage with their local political reality, giving voice to their concerns about fascism and their hopes for unity in support of liberation and democratic reform.

Concerns surrounding stylistic accessibility and appeal existed in Greece since the 1920s, but the reporting of the Russian Revolution, the transmission of Soviet political theory, and the promulgation of Socialist Realism generated an increased emphasis on these tenets.Footnote 18 Indeed, during the Second World War, Russia's history of mass social action and the military might of the Soviet Union appealed broadly, beyond avowed communists who sought to incite revolution in Greece. In this context, Socialist Realism benefited from its association with socialist discourse, and for artists and intellectuals, the primary artistic goal of creating art for ‘the people’ gained momentum as it expressed a prevailing spirit of anti-fascist unity, solidarity, and egalitarianism.

While notoriously difficult to define, of the officially recognized qualities of Socialist Realism, accessibility (dostupnost’) and relevance to the masses (massovost’) were promoted as priorities for Greek artists. For music, the central aesthetic concerns of bringing art to ‘the people’ prescribed stylistic accessibility that was broadly identified in a tonal musical language that was melodic and rousing.Footnote 19 It furthermore called for music that was underpinned by a social or political message relevant to the time.

This article identifies how Greek artists engaged with these same principles, however, as I will illustrate, strict comparisons with Soviet Socialist Realism and an interpretive lens limited by an understanding of how the aesthetic doctrine ultimately crystallized into a ‘rigid, administered, “boring” dogma’ in the Soviet Union,Footnote 20 cannot do justice to the local appropriation of Socialist Realism in Greece during this time and its significance within the local context.Footnote 21 Furthermore, while the priorities of accessibility and broad appeal could also characterize fascist culture, the deliberate efforts to divorce these qualities from fascist politics in the Greek press and mainstream musical periodicals are also addressed in what follows.

Lifting the curtain on existing Skalkottas scholarship

The partitioning of Skalkottas's works into two distinct categories took place despite the fact that he composed atonal and serial as well as tonal music throughout his career without, as Jim Samson writes, ‘any sense that he valued any one type more highly than the others’.Footnote 22 Furthermore, a number of his works demonstrate attempts to combine atonality and tonality, suggesting that he did not necessarily conceive of the two idioms as incompatible.Footnote 23 Nevertheless, contradictory responses have pitted the two compositional approaches characteristic of Skalkottas's oeuvre in opposition to each other, producing an authenticity discourse expressed in claims that identify the ‘true’ Skalkottas in either his atonal or tonal works.

Perceptions of Skalkottas's Greekness were also deeply implicated in these responses and similarly related to the rival aesthetic ideologies of the Cold War. On the one hand, his Greekness was seen as mediated through his association with Western Europe and his channelling of Western European musical trends. Propagating the narrative that Greek identity was rooted in European musical traditions can also be considered a political standpoint in terms of ever-present debates regarding Greece's status as Balkan or European, emerging from the country's geographical ambiguity, which situates it at a political and cultural crossroads between East and West. On the other hand, Skalkottas's Greekness was evinced in his engagement with Greek folk song, in music that was considered unadulterated by foreign influence. These competing notions accorded with the respective rival aesthetic ideologies of the United States and Western Europe, and the Soviet Union, which each vied for primacy in the cultural Cold War.

Behind this posthumous mythopoesis of Skalkottas, there is a sense that musicians and critics in Greece sought to construct a hero figure in the ruins of dictatorship and war – a paragon of resilience against adversity, musical excellence, and unwavering Greekness, whose music fulfilled and expressed political functions and cultural ideals deemed crucial for reconstructing the Greek national imaginary. In the spirit of Cold War tensions, any work associating the Greek and Soviet experience in the early twentieth century in any capacity consequently became increasingly uncomfortable, provoking consternation, resentment, and even outright outrage. The lasting impact of the competing perspectives of Kalomiris and Papaioannou on contemporary reception of Skalkottas's work, and the scholarly reluctance to confront the impact of Socialist Realism on his oeuvre, illustrate how the notion of totalitarianism has functioned as a potent intellectual weapon, fuelling Cold War-style opposition against leftist politics and its associated cultural expressions.Footnote 24

Indeed, although the evidence suggests that Skalkottas remained engaged with Greek political reality even during his time in Berlin and gave much consideration to the political relevance of his works, especially during the German occupation, he has been frequently described as a socially and politically detached figure. For example, the musicologist John Thornley describes him as a ‘politically naïve’Footnote 25 figure with a ‘remarkable creative ability to detach himself from his surroundings’.Footnote 26 Ben Earle posits that Skalkottas ‘was evidently a monomaniacal dilettante, sitting up night after night in an indifferent Athens to notate immense scores according to esoteric schemes’,Footnote 27 while Mantzourani writes that ‘until his death in 1949, [Skalkottas] composed his “serious” dodecaphonic works in complete isolation, thus maintaining his high ideals and developing an idiosyncratic musical language’.Footnote 28 The conductor Vladimiros Symeonidis has recently spoken in a similar vein. While acknowledging that Skalkottas would have been ‘somehow influenced by the circumstances’,Footnote 29 he nevertheless suggests that Skalkottas ‘is an archetype … [he] embodies, in a way, the image of the romantic artist’ and that ‘this image is certainly valid for the music of his last period’.Footnote 30

In apparent efforts to validate Skalkottas's genius through an emphasis on his hermetic social isolation and melancholic mental state, these portrayals succumb to the pitfalls of the Romantic notion of the autonomous artist, essentially divorcing the composer's works from the political landscape and broader field of production in which they were created.Footnote 31 Notwithstanding the problematic ‘romantic notion of the “composer” and its attendant ideology of the genius in the garret’, these qualities have, to varying degrees, been expressed in the two main musical historical narratives on Skalkottas cultivated by Papaioannou and Kalomiris.Footnote 32

There are, however, important shades between the defining extremes in Skalkottas scholarship that nuance the lasting perspectives of Papaioannou and Kalomiris. Indeed, my interrogation of Skalkottas's direction towards tonality builds on the work of several scholars who, in the decades following his ‘rediscovery’, have begun to reconsider the classification of Skalkottas's works into two distinct categories and thereby problematize the idea of a radical shift towards tonality in the last years of his life. This scholarship includes the work of Katy Romanou, Kostis Demertzis, and Ioannis Tsagkarakis,Footnote 33 as well as that of Minos Dounias, George Zervos, and Melissa Garmon Roberts.Footnote 34

These reassessments of Skalkottas's evolving relationship with tonality have been instrumental in beginning to dismantle the binary distinctions within Skalkottas scholarship and public opinion on the composer. However, the sociopolitical factors impacting this relationship with tonality require urgent further attention, lest they be entirely erased in an era of heightened Cold War attitude and rhetoric. I argue that these reassessments should go beyond the scope of considerations such as those explored in Zervos's writing for example, which focus on motivations relating to Skalkottas's connection with his national identity and Schoenbergian modernism. Instead, they should be expanded to encompass inquiries into accessibility concerning the composer's association with anti-fascism and the dissemination of Socialist Realism in Greece. How did politicized discourses surrounding accessibility, functionality, nationality, and popularity gain traction in the capital and become relevant for Greek composers in the context of Nazi occupation, and where is this impact reflected in Skalkottas's works and writings? These are the questions that will be addressed in the following sections.

Socialist Realism in Greece

The Russian Revolution launched a cultural inquiry into new forms of musical expression that effected a radical break from Tsarist culture. Shostakovich, Myaskovsky, and Mosolov were driving forces of musical modernism, and the Soviet Association for Contemporary Music (ASM) advocated for modernist experimentation and promoted avant-garde music from Western Europe and the Soviet Union. Modernist principles were espoused across the arts as proto-Communist, breaking down traditional cultural hierarchies which had previously privileged the bourgeois elite, thereby reflecting artistic freedom, opportunity, and egalitarianism.

While a modernist and avant-garde movement had responded to the ideals and sensibilities of early communism in the Soviet Union in the 1920s, it was deemed no longer relevant to the social, political, cultural, and nationalist priorities of the 1930s. A new aesthetic was considered necessary to replace it, one that was widely accessible and appealing to the masses: a positive reflection of communist reality – whether real or imagined. In these malleable terms, Socialist Realism was formulated in opposition to modernism, marking a shift in the acceptable mode of left-wing musical expression. Cultural officials within the Soviet Union favoured text-based works including mass songs and cantatas which were suitable to ‘carry ideological messages desired by the party’.Footnote 35 Instrumental works, more limited in their capacity to represent reality and be tendentious, had to be ‘easily understandable to the broad masses and preferably melodic, stirring, and uplifting’.Footnote 36 In this vein, a Romantic and Russian Classical symphonic repertoire provided a suitable basis for musical form and style, and programmes, the use of folk materials, and optimistic endings were encouraged.Footnote 37

As Socialist Realism – being both a trend in artistic practice and a historical discourse – traversed geographical, social, cultural, and political borders throughout the twentieth century, it assumed a multitude of forms and meanings through its engagement with local contexts. Attuned to the variety and diversity of Socialist Realism's impact within and outside of the context in which it emerged, I situate the doctrine and the discourses surrounding it within a ‘global ontological framework of connected histories’.Footnote 38 This approach facilitates a richer understanding of how Socialist Realism could signify differently in different places and times. It could, paradoxically, serve as both a vehicle of Soviet state power and oppression and, outside the Soviet bloc, as a genuinely inspiring set of ideas and qualities that appealed to artists who wanted to communicate to their compatriots – particularly amid the Nazi occupation. These artists, in response, produced ‘creative, interesting music that fit within a broad interpretation of [Socialist Realism's] tenets’.Footnote 39

The Greek engagement with Socialist Realism was facilitated and structured through various mechanisms from across the political and cultural landscape, including the periodical press, cultural magazines, literary journals, and exhibitions of visual art. Pre-eminent cultural figures such as Dimitris Glinos, Kostas Varnalis, and Nikos Kazantzakis reported on the social, cultural, and political landscape of the Soviet Union, helping to transmit, circulate, and mediate the political and artistic instructions of Socialist Realism and adapt these to respond to the Greek context.Footnote 40 This section is structured around several influential periodicals and cultural agents that were most effective in mediating Soviet political theory, socialist discourse, and Socialist Realism into Greece. Crossing disciplinary boundaries, I underscore the contemporaneous relevance of Socialist Realism within artistic discussions and debates in Athens, before situating Skalkottas's turn to tonality within this context.

In September 1934, the magazine Néoi Protopóroi (New Pioneers) published a special edition dedicated to the first Congress of Soviet Writers, where the doctrine of Socialist Realism was formally outlined. According to Christina Ntouniá, this introduction in Greece ended long-standing debates regarding the form and function of proletarian art that had emerged decades earlier, especially since the introduction of communist and socialist theory in Greece.Footnote 41 While there is no direct evidence that Skalkottas read Néoi Protopóroi, the magazine signals how Socialist Realism was promulgated by the Greek leftist press, highlighting the widespread concern for artistic accessibility and political relevance that it advocated. Indeed, Ntouniá writes that Néoi Protopóroi was one of the most significant publications of the 1930s in terms of the role it played on the ‘field of ideas’, and the influence it exerted on left-wing intellectuals and writers.Footnote 42 The magazine not only expressed ‘the ideology of the official political organ of the left’ but also aimed ‘to connect a broad spectrum of intellectuals and artists’ who ‘challenged established frameworks’ and searched for ‘an art that expresses a new social dynamic’.Footnote 43 However, after the first Congress of Soviet Writers, the Greek Communist Party became more involved in the magazine's output, aligning it with the artistic instructions defined by Gorky and Zhdanov.Footnote 44

In Néoi Protopóroi, the pre-eminent Marxist critic Alexándra Alafoúzou discusses how Socialist Realism replaced other doctrines, representing a ‘higher art’ that could facilitate the ‘general transformation of the entire mass of workers into conscious and active workers of the classless socialist society’.Footnote 45 The magazine published the keynote speeches from the 1934 Congress of Writers delivered by Gorky and Zhdanov, in which the artistic doctrine of Socialist Realism was officially promulgated. According to these speeches, ‘artistic portrayal’ should ‘depict reality in its revolutionary development’ and ‘truthfulness and historical concreteness … should be combined with the ideological remoulding and education of the people in the spirit of socialism’.Footnote 46 Néoi Protopóroi ‘immediately undertook the mission of implementing’ the resolutions defined by the congress. This took the form of publishing ‘visual art by Soviet artists who faithfully serve the doctrine of Socialist Realism’, publishing translations of literary texts, literary criticism reinforcing the ‘necessity of Socialist Realism as an artistic method’, and reviews of Greek literature, theatre, cinema, and visual arts that ‘make the intentions of the magazine's editors to implement Socialist Realism according to the instructions defined by Gorky and Zhdanov evident’.Footnote 47 According to Ntouniá, after 1934, the magazine published an increasing number of Soviet and European theoretical texts with the primary purpose of ‘supporting and popularising’ Socialist Realism.Footnote 48 In the first years after the Congress of Writers, ‘Greek intellectuals on the left, the majority of whom in this period rallied around Néoi Protopóroi, accepted the decisions of the Congress of Writers with the enthusiasm of their European comrades’.Footnote 49

As representatives of the Greek intelligentsia, the poet, writer, and journalist Varnalis and the philosopher, politician, and educator Glinos, both frequent contributors to Néoi Protopóroi, were invited to take part in this first Congress.Footnote 50 Upon their return, writing in the pages of Néoi Protopóroi and the newspaper Néos Kósmos (New World), Glinos and Varnalis introduced Greek audiences to Soviet literary trends and Socialist Realism through articles including ‘The Cultural Revolution’.Footnote 51 In a November 1934 piece for Néoi Protopóroi, Glinos, who had previously served as secretary-general of the Ministry of Education and later became a parliament member with the Greek Communist Party, wrote about the Congress and described the creative method of Socialist Realism as an ‘optimistic art, powerful and full of faith and hope’.Footnote 52 According to Glinos, Socialist Realism provided proletarian artists with a range of themes to engage with, including ‘war, fascism, the demolition of capitalism (and) the heroic struggle of the proletariat’.Footnote 53 Varnalis echoed this sentiment on the eve of the German occupation of Greece in 1941, writing that: ‘Those engaged in cultural production should be near to the People, they should put their heart on the heart of the People so that it beats willingly together … to unroot the sterile art’.Footnote 54 Commenting on the emphasis on Socialist Realism and how it shaped discussions regarding artistic style and function, Angeliki Koufou observes that ‘from discussing proletarian literature and realism … Néoi Protopóroi shifted its attention to the tenets of Socialist Realism which embraced and enriched these artistic principles’.Footnote 55

Visual art scholar Costas Baroutas describes the impact of Socialist Realism, which reached Greece through publications such as Néoi Protopóroi and Néos Kósmos, on Greek visual artists:

from 1917 onward, Greek artists began to take an interest in Soviet art, initially called proletarian art, then Socialist Realism from 1932. The social messages of the Russian Revolution and the images of workers’ battles, social revolutions, demonstrations, strikes, and more generally the life of workers and farmers provided inspiration for many artists and students of the Athens School of Fine Arts throughout the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 56

According to Baroutas, ‘the decisive event in the history of Socialist Realism in Greece was the exhibition of Soviet engravings in Athens in 1934’.Footnote 57 Writing about the exhibition, the writer and journalist Zacharías Papantoníou declared in Elefthéron Víma that the Soviet artists, with their work, combat the philosophy of ‘art for art's sake’ which had flooded Europe.Footnote 58 In Rizospástis (Radical), an anonymous contributor writes that the Soviet art is ‘indebted to the proletariat which has destroyed capitalism … who have cleared the path for the masses for art’.Footnote 59 In an earlier article in Rizospástis entitled ‘A Soviet Exhibition in Athens’, the anonymous author describes another exhibition in Zeó on Fillelínon Street showcasing Soviet embroidery and engravings. According to the author, these items demonstrate the emphasis the Soviets place on art, thus opposing the ‘reactionary slander’ that in the USSR ‘man has become machine’ at the expense of ‘art and initiative’.Footnote 60

After these exhibitions and the issue of Néoi Protopóroi devoted to the Congress where Socialist Realism was outlined, the term was adopted by Greek artists, about thirty of whom were ‘enthusiastic about the Soviet cause’.Footnote 61 Indeed, in the years following the Congress, Greek artists appropriated Socialist Realism to respond to Greek political reality and there were an increasing number of exhibitions showcasing Socialist Realism at prominent venues, including the Stratigopoúlou and Parnassós galleries, and the Soviet embassy in Athens.Footnote 62 Aside from its publication in Néoi Protopóroi, Socialist Realist art also found its way into several left-wing newspapers and magazines including Neolaía (Youth) and Rizospástis. Footnote 63 The Greek appropriation of Socialist Realism is summarized in the words of an art critic who wrote under the pseudonym Ilgia in Rizospástis in 1936, shortly before the Metaxas dictatorship. Reformulating Stalin's declaration on Soviet national cultures being ‘national in form, socialist in content’ from 1930,Footnote 64 Ilgia asserts that in Greece ‘progressive artists are national in form and content, international in their ideological platform and realist in art’.Footnote 65

The flourishing of art inspired by the qualities of Socialist Realism ended abruptly with the establishment of the fascist Metaxas dictatorship. Néoi Protopóroi and Rizospástis, along with other left-wing publications, fell victim to the regime's strict and vehemently anti-communist censorship campaign.Footnote 66 During this period, Socialist Realism, as an artistic style closely related to society, possessed, as Baroutas notes, a ‘capacity to translate a militant and revolutionary spirit’, making it a suitable mode of creative expression for Greek artists who sought to align their work with the political and social struggle.Footnote 67 While the characteristic optimism of Socialist Realism was less suited to depict the devastation of Nazi occupation, from 1941 to 1944, ‘Socialist Realism survived among certain artists who were directly involved in the secret armed resistance’, and also in the works of artists ‘with differing political opinions’.Footnote 68

For Greek musicians, as Tsagkarakis writes, ‘the need for direct communication was by far the sine qua non condition of the moment. In other words, Greek music needed to be placed at the service of a liberation movement.’Footnote 69 Even before the German occupation, in the years following the promulgation of Socialist Realism in the Greek press, numerous articles from musical publications stressed the social emancipation and responsibility of musicians, emphasizing the necessity for music to be widely accessible and elevate the cultural level of the people.

In the pages of Mousikós Kósmos (Music World), the organ of the Panhellenic Music Union – of which Skalkottas was a member – readers were encouraged to confront the practical challenges facing professional musicians through (re)considerations of the role and function of music, and musicians’ civic duty. An article from January 1935 entitled ‘The Professional Musician and his Duty’ proclaims that: ‘[The Greek musician] with the social emancipation, particularly of the post-war years … saw clearly how the axiom “art for art's sake” was nothing more than a nonsense that truly meant “art for the pockets and the revelry of the privileged” … the musician serves the rise of the artistic level and of his own standards of living’.Footnote 70 In a similar spirit, a later article champions musicians as the ‘honorable workers of social enlightenment, and moral and spiritual transformation, and the sole responsible contributors to social education’.Footnote 71

Several articles in the same vein criticized the notion of ‘art for art's sake’, advocating instead for the widespread dissemination and democratization of music, urging musicians to serve the masses. The language used to discuss accessibility and mass appeal in relation to music echoed that of Socialist Realism in the Greek press, thereby aligning musical qualities with its principles. These qualities, however, could be cited by antagonistic cultural and ideological agendas, both socialist and fascist. Yet, it is important to remember that anti-fascism functioned as a structuring political principle and cultural philosophy, playing a powerful role in mainstream political discourse at this time. Consequently, numerous articles within the Greek leftist press and music periodicals emphasized the connection between accessibility, mass appeal, and leftist politics and/or anti-fascism, thereby mitigating ideological ambiguity.

A notable example can be found in a Mousikós Kósmos article entitled ‘Music and Fascism in Italy’, which takes an unequivocal stance against fascism as a suitable ideological basis for creating culture that is accessible and has mass appeal. It begins with the assertion that ‘under the spectre of fascism every expression of the spirit is extinguished’.Footnote 72 The article further contends that ‘in 13-years of fascism they did not manage to inspire a single serious artistic work’ and that ‘on the contrary we observe the enormous spiritual development in the democratic nations, and in particular in the country where the liberation of man from the exploitation of his fellow man was accomplished’.Footnote 73 While different and sometimes antagonistic ideological threads ran through the conceptual history of ‘music for the masses’, there is a clear intention in the pages of Mousikós Kósmos to disassociate qualities of accessibility and mass appeal from fascism. Instead, as implied earlier, they are associated with Soviet culture.

Further articles in Mousikós Kósmos and elsewhere explicitly celebrate Soviet musical life, for instance a 1934 interview published in Rizospástis with Dimitris Mitropoulos, a contemporary of Skalkottas and a leading pioneer and advocate of musical modernism in Greece, who also supported Skalkottas's tonal works. Mitropoulos claims that ‘if you were to ask me where I would prefer to work as an artist, I would respond unequivocally: A thousand times—Russia!' where the ‘interest of the workers in art … is more developed than in all the nations’.Footnote 74 Furthermore, in a 1935 interview, Mitropoulos emphasizes that a wealth of musical institutions and the democratization of music foster ‘love, interest, and zeal’ among the wide Russian public for classical music. He adds that ‘there is no country in the world where music tends to be the property of all the people’.Footnote 75

During Nazi occupation, the Greek resistance movement ‘grew rapidly and spread widely’, as Alexandros Charkiolakis points out, ‘[m]any joined the political branches of the various resistance groups, depending on their ideological stance. EAM (Ethnikó Apeleftherotikó Métopo – The National Liberation Front) was the largest and most popular resistance organization and it maintained branches in various professional occupations, including musicians’.Footnote 76 In the early period of the occupation, EAM published an ‘illegal leaflet under the title “The Musician”’, which was covertly distributed amongst musicians in, according to Xenos, ‘even the smallest of orchestras’.Footnote 77 The purpose of this leaflet was to ‘enhance morale and attract more people towards joining the resistance movement’.Footnote 78

In this context the qualities associated with Socialist Realism which had been previously defined in the pages of Néoi Protopóroi, for example, found fertile ground across the musical landscape. Indeed, Socialist Realism's emphasis on accessibility and mass appeal was particularly relevant in terms of the EAM's inclusive anti-fascist stance.Footnote 79 For music, the language primarily favoured to serve the goals of mass communication and social and political relevance emerged as one which was tonal, vocal, and diatonic.Footnote 80

The guerrilla songs of the Greek resistance known as andártika – so called to reflect their connection with guerrilla fighters (andártes) – reflect the qualities of Socialist Realism favoured by cultural officials in the Soviet Union in the 1930s and 1940s. The original tunes of andártika were composed by both professional and amateur musicians organized in the resistance, intended as mediators of togetherness and solidary, and emotional catalysts. Greek authors borrowed from a history of established musical codes associated with resistance and revolutionary songs to foster accessibility and appeal.Footnote 81 The music of andártika primarily served to facilitate engagement with the lyrical messages promoting solidarity, patriotism, and national unity. In these terms, andártika resemble Soviet mass songs of the 1930s. While andártika were propagated from below and transmitted largely by oral traditions, as opposed to mass songs which were a state-sponsored form of mass culture – often emerging in association with film – they share crucial and characteristic features in their ‘optimistic humanitarian and positive lyrics and accessible tunes’.Footnote 82

Qualities of accessibility, a national perspective, and an emphasis on broad appeal are also expressed in this period in the works of communist composer – and friend of Skalkottas – Alekos Xenos, particularly in his Symphony No. 1 subtitled ‘The Resistance’. Xenos based the three movements of this symphony, referring to the lives and struggles of the guerrilla fighters in the mountainous regions of northern Greece where much of the hand-to-hand combat took place, on three emblematic andártika. In both a political and an aesthetic sense, the narrative symphony, pertaining to the Greek resistance against Nazi occupation, embodies the qualities of ‘heroic classicism’ favoured in symphonic Socialist Realist works.Footnote 83

Xenos was an active member of the Greek resistance, playing a prominent role in the musicians’ committee under the guidance of EAM and composing several andártika of his own. In his autobiography, he describes pertinent conversations with Greek composers, including Skalkottas:

From the conversations I had originally with Lavragas, and later with Kalomiris, Varvoglis, Mitropoulos and Skalkottas, regarding the problems of musical art, I formed the impression that in our current situation we had to communicate with the people and therefore we needed an art that was national in form and progressive and socialist in content.Footnote 84

By channelling Stalin's slogan, Xenos's statement indicates an awareness of ideas regarding accessibility and the political relevance of art, as well as their association with Socialist Realism among the Athenian musical community during the occupation. While the statement is not dated, it is reasonable to suggest that it coincided with Xenos's involvement with EAM in 1941, shortly after which he became secretary-representative of the intellectual-artistic branch of the organization. While Xenos refers to Skalkottas along with several other composers in this statement, in his autobiography he mentions a close friendship with Skalkottas: ‘I became close with Nikos Skalkottas when he returned from Germany … we had never-ending discussions about the good and bad of modern art. Later … we became even closer and many times he would bear his soul to me.’Footnote 85 Xenos's reference to discussions with Skalkottas, as well as the friendship he describes between the two composers, establishes an important connection between Skalkottas and Socialist Realism. According to Xenos, Socialist Realism's tenets – corresponding to the social and political climate of the occupation in Greece – clearly resonated with artists united in their opposition to Nazi occupation.

The extent to which Skalkottas explicitly shared Xenos's political views is uncertain; however, another testimony, that of Dimitris Efthimiopoulos – a long-term friend of Skalkottas, who was imprisoned at the Haidari concentration camp at the same time as the composer – suggests that his politico-musical activity was indeed allied with the anti-fascist movement. In an interview with the musicologist George Leotsakos in 1981, Efthimiopoulos recalled that Skalkottas participated in ‘veiled but scornful criticisms of the Metaxas regime’, for example.Footnote 86 Recalling their imprisonment at Haidari, Efthimiopoulos told Leotsakos, ‘I didn't ask him [about his politics] at Haidari. There, we didn't ask such questions. But … I believe that he must have been in a [resistance] organisation … as far as I could see he was anti-regime, politically progressive, a friend of the people.’Footnote 87 In this vein, a series of programmatic works – now lost – composed during Skalkottas's imprisonment, and two military marches written after Greek liberation, call his apparent political naivety and detachment strongly into question.Footnote 88 Indeed, John Thornley questions whether the marches were a result of the composer's ‘radicalization’ after his imprisonment at Haidari, representing an attempt to express sympathy with the resistance movement.Footnote 89

While posing this question of politico-musical agendas and what we label as Socialist Realist may appear academic, as Lily Wiatrowski Phillips states in her pertinent study on W. E. B. Dubois entitled The Black Flame as Socialist Realism, ‘the crucial question … is why it may be useful’.Footnote 90 In the context of Skalkottas scholarship, considering the composers’ embrace of tonality through the lens of Socialist Realism helps to challenge the pigeonholing of his oeuvre and the conventional wisdom that Skalkottas was an apolitical, ahistoric figure whose tonal music is seemingly unworthy of critical attention and contextualization. It ultimately becomes possible to square Skalkottas's works – both tonal and atonal – with the fundamental understanding that, as Charles Wilson writes, ‘Artworks, however innovative and “independent”, inevitably take shape against the background of shared conventions (whether these are tacitly accepted or deliberately transgressed)’.Footnote 91

Skalkottas's writings

Skalkottas's writings in a series of undated and unpublished essays, several of which are considered to have been intended for the popular progressive literary journal Neoelliniká Grámmata (Neohellenic Letters), indicate his concerns on artistic matters which were being advanced in relation to Socialist Realism.Footnote 92 Published weekly from 1935 to 1941, Neoelliniká Grámmata's content focused on literary, artistic, and scientific issues and contained articles by ‘the most progressive of the mainly leftist younger generation of writers, critics and journalists at the time’.Footnote 93 Skalkottas discusses various issues including the use of folk song, musical influences, and compositional style, focusing on questions of musical accessibility and dissemination, interrogating the intersections of music and its social and political reality, and grappling with issues pertaining to the role and function of music in society.Footnote 94

While Skalkottas's essays were until recently housed in the composer's archive, the original manuscripts are now confirmed to be lost. This raises crucial questions surrounding the maintenance of the archive and invites us to consider the factors that could have contributed to their absence. These considerations are particularly pertinent in the context of the fraught construction of Skalkottas's legacy, which persists to the present day.Footnote 95

In an article entitled ‘Musical Search’, Skalkottas discusses a ‘new critical means’, with which to move towards a music that is more closely related with society.Footnote 96 His language echoes the fundamental principles of Lenin's theory of reflection, as outlined in ‘Materialism and Empirio-Criticism’ (1909):Footnote 97

The search for an appropriate musical expression [I mousikí anazítisis] surprises us and presents us with new ways of thinking, a new critical means, and it inclines us to carve a new true path for the music of our century … The meaning, therefore, of this musical search, is the passage towards the bright and informed, [towards] stable mirrors of reality … Here we combat every shallow superficiality … Machine music is pursued meticulously … emerging in new schools of thought … We conceive of the strength [of this music] yet struggle to grasp what this [music] means in terms of the search for musical truth … a clear, truthful, light-filled, and realistic invention [instead] leaves an impression of something more ‘alive’.Footnote 98

Skalkottas's writing echoes Lenin's formulation that consciousness reflects objective reality, as moulded by and evolving according to changes in material conditions. Invoking the shifting acceptable mode of leftist musical expression signalled by the promotion of Socialist Realism, Skalkottas criticizes machine music to underscore the necessity for a music that is instead more ‘clear, truthful, light-filled’, ‘realistic’, and ‘alive’.

A requirement that music reflects reality in ‘truthful’ terms that is informed by personal experience emerges as a recurring theme in Skalkottas's essays, including in ‘Collection of Ideas’. Here, while discussing a pathway for the creation and dissemination of new music, Skalkottas writes that ‘to propagate [a new music with a theoretical basis], we ourselves must experience it, if it is possible, to the best of our ability’.Footnote 99 The potential of such a foundation for music is ostensibly profound:

an idea can lead any which way, to destroy, to throw light on the birth of a new era, and to establish an environment that is beneficial for human life, if indeed we choose to rely on an idea that moves us, enthuses us, and shows us new horizons – new paths previously unexplored by the human mind – we will discover enough drive towards a general cultural perception that is entirely our own.Footnote 100

In another essay where Skalkottas discusses trends within contemporary schools of music, he highlights the presiding objective of this new music: ‘to enlighten us for exploring and discovering reality’.Footnote 101

Skalkottas continues to grapple with the relationship between art and reality in other articles, including in ‘The Theory and Practice of Musical Rules’. While the essay's syntax is highly obscure, the following extract, in which Skalkottas describes how accessibility can help facilitate a potential shift away from ‘absolute or neutral’ music, is significant:

In this way a superior musician could also turn to higher ideological phases, with political tendencies, wanting to interpret a musical creation not as absolute or neutral … but as a revolutionary harbinger of new tendencies, such as an oratorio or a musical narration of political events on fantastic and eccentric rhythms of a new musical atmosphere. … We must, therefore, in the application of the rules of music, perhaps seek a simplified realism. The outcome of this process must resound in a realistic way and this (realism) could come to define any application of the rules of music.Footnote 102

Emphasizing the importance of making musical expression understandable, Skalkottas advocates for realism and simplicity, while also suggesting new approaches that promote music as social commentary, potentially with political implications. While musical realism had also been politicized by the right (as with the Metaxas dictatorship's claims on folk music, discussed previously),Footnote 103 the context of German occupation stimulated an interest in and engagement with realism as an anthropocentric elaboration of anti-fascist political concerns. In the preceeding quotation, Skalkottas appears to extol the political relevance of realism in these terms, considering it as a virtue for the creation of politically implicated and engaged music appropriate to the new political atmosphere necessitated by the German occupation. Ostensibly, despite realism's historical associations with fascist causes, the political circumstances of German occupation and the dynamics of resistance twinned the promotion of realism with social messages of accessibility, inclusivity, and unity against fascism, which appear to have been adapted from rhetoric associated with the popular front strategies of the previous decade.

In another essay entitled ‘The Power of Symphonic Concerts’, Skalkottas elaborates on artistic accessibility and comprehensibility, music's relationship to a living context, and the use of music to elevate the cultural level of the people. Skalkottas's wording is typical of Socialist Realist literature and criticism. Indeed, it is reminiscent of the language of Zhdanov's 1934 keynote speech from the Congress of Writers, which was reproduced in Néoi Protopóroi and echoed in the writings of prominent Greek cultural figures and intellectuals. Zhdanov discusses the necessity of artists ‘knowing life so as to be able to depict it truthfully … not to depict it in a dead, scholastic way, not simply as “objective reality,” but to depict reality in its revolutionary development … the truthfulness and historical concreteness of the artistic portrayal should be combined with the ideological remoulding and education of the toiling people.’Footnote 104 Consequently, invoking a phrase that appears to be derived from Zhdanov's definition of Socialist Realism, Skalkottas writes that:

The symphonic concerts that are intended to serve the sustainable and evolving education of the people need of course also to have a corresponding relationship to a developing and living context. … The symphonic musical concert … must have a meaning, one which is free from an incredible complexity of composition … the result must be … a living grandeur.Footnote 105

Here, Skalkottas advocates for a ‘living new direction’ that would facilitate accessibility. Beyond this, given the crucial connection with its ‘living context’, music concerts enjoyed by the ‘great masses’ would reflect ‘greater intelligence and reason’.Footnote 106

Skalkottas's writings reflect the reconceptualization of the role and function of symphonic concerts, associated with the leftist political ideals of inclusivity and mass appeal represented by Socialist Realism. Greek awareness of Soviet cultural developments, which would come to characterize the cultural and political programme of Socialist Realism, can be traced to articles from as early as 1921. For example, a 1921 article in Ergatikós Agón (Worker's Struggle), the official organ of the SEKE (Greek Socialist Party), describes in some detail the impact of the Revolution on Russian musical life, discussing the creation of new music that is ‘born of the proletariat’ and the reorientation of concert-life and music education towards the masses.Footnote 107 Ultimately, Skalkottas's essays reflect an engagement with concerns which were being discussed in relation to Russia since the Revolution and were foregrounded through the transmission of Socialist Realism in Greece, amplified in connection with Greek political turmoil.

The Classical Symphony

There are several works from 1941 to 1949 that reflect the composer's orientation towards accessibility, and, indeed, the qualities of Socialist Realism, in their musical characteristics, thematic emphasis on natural and agricultural subjects, use of folk motives, and references to antiquity.Footnote 108 I focus on the Classical Symphony from 1947 as Skalkottas's final major work which could represent the culmination of the composer's orientation towards tonality and accessibility.Footnote 109 This work was ostensibly not commissioned – unlike several other tonal works from this period – raising crucial questions around its creation that we can consider alongside numerous extant sources relating to the work.

In particular, my focus on the symphony is prompted by the existence of the composer's handwritten programme note in the manuscript score, which points to a political extra-musical narrative, marking out the work as a particularly rich source. This programme note has not yet been the subject of scholarly analysis, and quotes presented in this article appear in English translation for the first time.Footnote 110

The symphony was composed amid the Greek Civil War. Despite the backdrop of escalating warfare and political uncertainty, Skalkottas's personal life appears to have been passing through a rewarding and relatively stable phase.Footnote 111 It is written for a large wind ensemble, features strings and percussion, and adheres to the conventions of Western harmony. Its structure follows a traditional four-movement form comprising a ‘Little Overture’, Rondo, Scherzo, and Finale. The thematic sonata form of the first movement, along with the overall sense of metric regularity, reinforces the classical spirit of the work. Indeed, according to the composer's autograph notes, the work is a ‘dedication to the classical symphony’.Footnote 112

Skalkottas paid significant attention to the instrumentation and orchestration of his works, something which is evinced in the composer's essays including Orchestration, Theory and Practice of Musical Rules,Footnote 113 and Treatise on Orchestration, a manuscript of about 150 pages including several musical examples, which Demertzis dates to 1939.Footnote 114 Aside from the Classical Symphony, Skalkottas composed a number of other works for wind orchestra including the now lost Concerto for Wind Orchestra and the Concerto for Violin, Viola, and Wind Orchestra. He also transcribed nine Greek Dances and the Ancient Greek March for wind orchestra. It is not known whether his emphasis on works for wind ensemble was the result of an association with a particular wind band, military or otherwise. His extensive writing for wind ensembles has often been framed as an idiosyncratic indulgence or eccentricity.Footnote 115 However, bearing in mind Skalkottas's considered interest in orchestration, his decision to compose a large-scale classical symphony for wind orchestra in the aftermath of Nazi occupation and during the Greek Civil War warrants greater scrutiny. Indeed, the characteristic features of the work, which prioritize accessibility, along with insights from the composer's programme note, suggest two significant politico-musical influences and motivations. These relate to the influence of his time in Weimar Germany and the traditional role of wind bands in Greek society.

Aside from the more obvious markers already mentioned, the Classical Symphony contains several features which sincerely reinforce the classical spirit of the work and its emphasis on accessibility. The introduction of the first movement begins with a grand symphonic gesture, or what Skalkottas terms a ‘distant dramatic announcement’ (Example 1).Footnote 116 This introduction is severe, featuring syncopated chromatic ascending phrases, diminished seventh harmonies, and structural symmetry. It culminates in a heraldic fanfare punctuated by percussion through a perfect cadence (bb. 14–17).Footnote 117 This recurring heraldic fanfare is contrasted with a lyrical melody introduced in the oboe (b. 18) which recalls, in Skalkottas's words, a ‘simple classical song’.Footnote 118 The melody appears to be written in a folk idiom, emphasized by the use of the Dorian mode and acciaccaturas that appear in the oboe and piccolo when the melody repeats (b. 23). These embellishments and the triplet rhythm give the melody an almost improvisatory character, further emphasizing the folk quality. Meanwhile, the oboe and piccolo playing in unison evokes the timbre of the Greek floghéra, a type of flute common in Greek folk music. This lyrical theme returns in the solo trumpet, followed by the horn, framed by a repeat of the ‘distant dramatic announcement’.Footnote 119

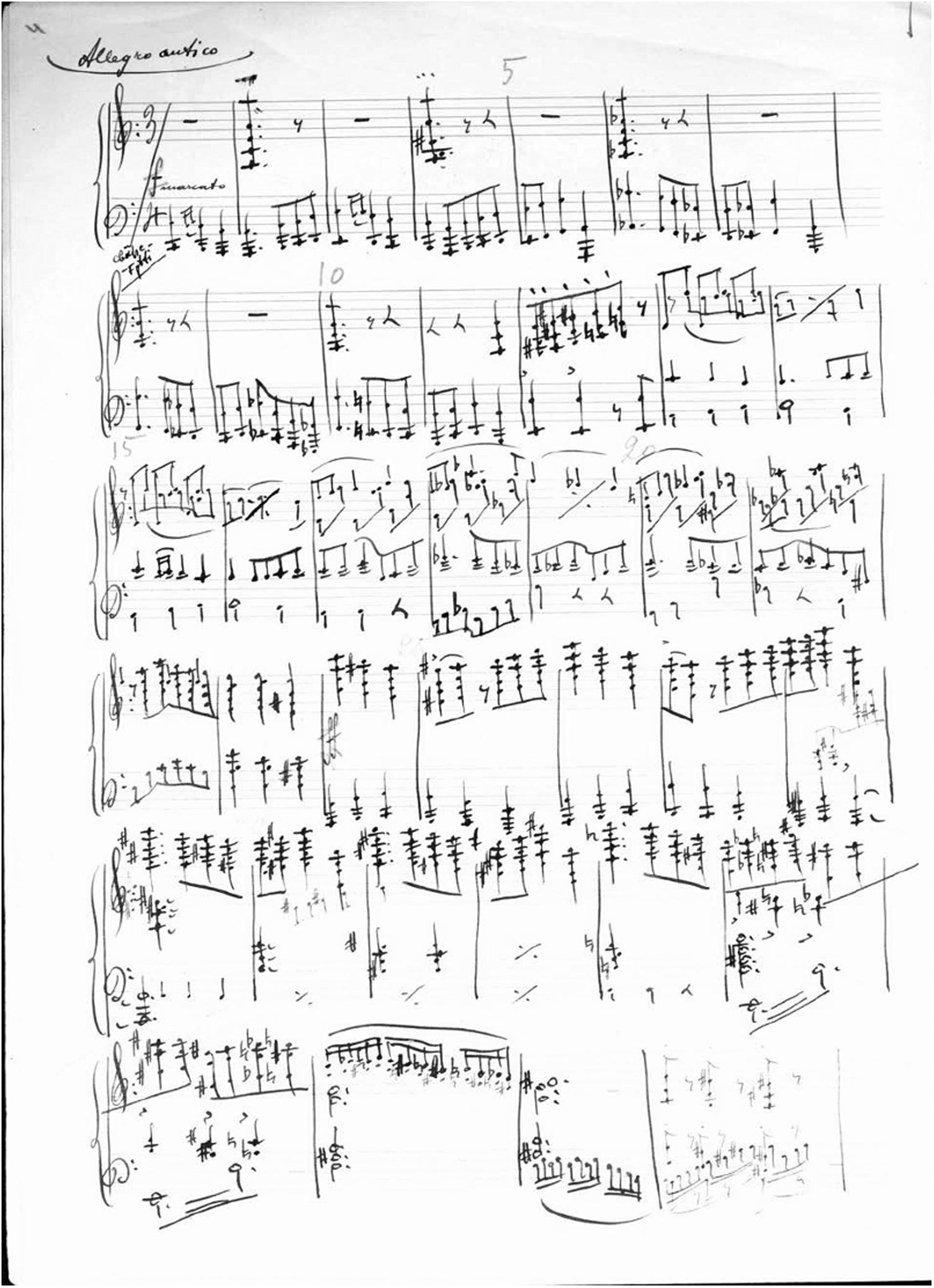

Example 1. Nikos Skalkottas, Symfonía se klassikón ýfos (gia orchístra pnefstón organon) (Symphony in a Classical Style (for wind orchestra)), 1947, Music Library of Greece ‘Lilian Voudouri’ Digital Collections, autograph score of composer's piano reduction, Folder 2008, Subfolder C, bb. 1–26, p. 1, https://digital.mmb.org.gr/digma/handle/123456789/60389.

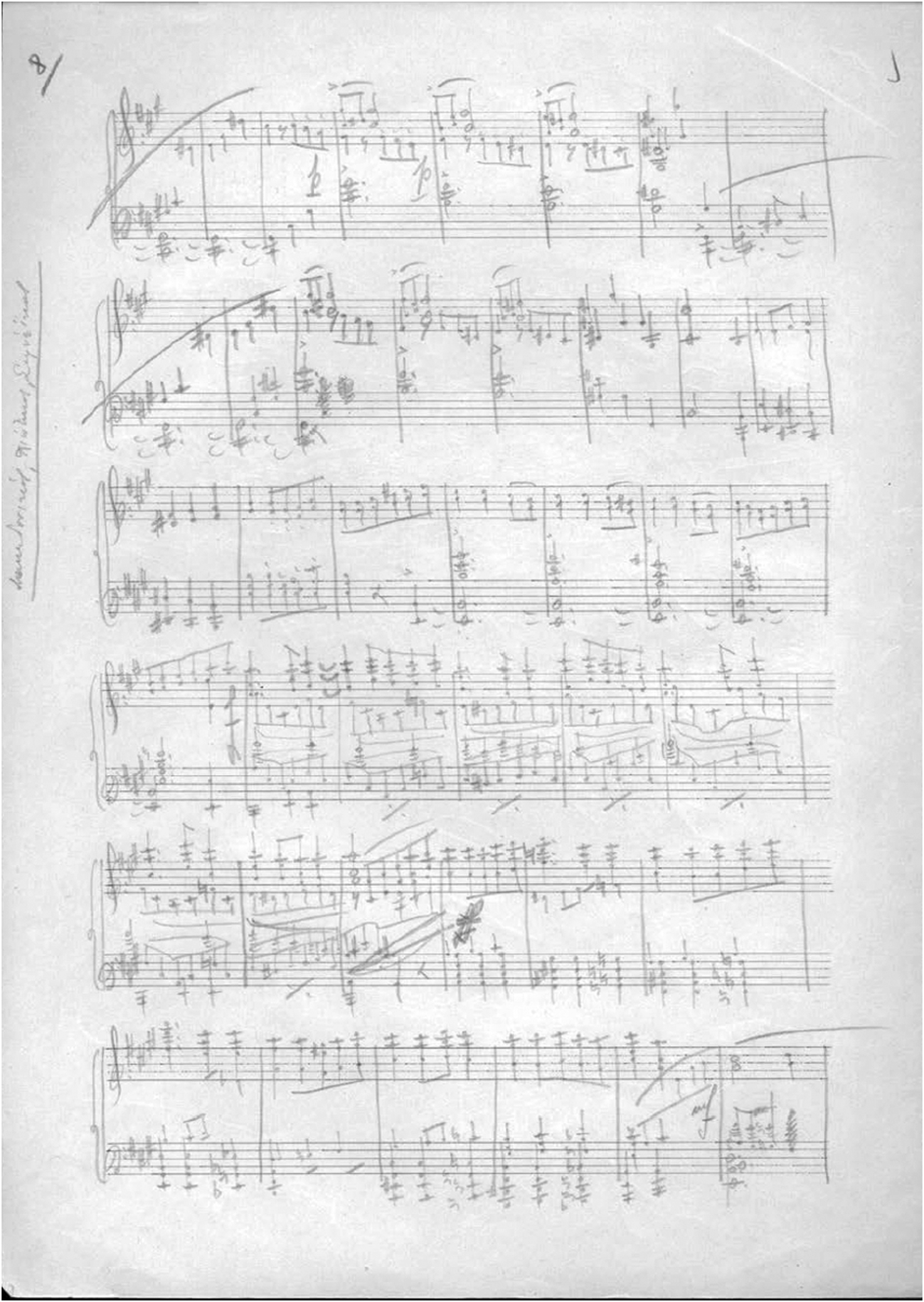

The main theme that follows is marked ‘Allegro antico’ (Example 2), which roots the work in the past. Indeed, Skalkottas writes that the main theme, appearing first in the basses, is ‘archaic’.Footnote 120 The classical character of this section is emphasized by the strict contrapuntal texture, reminiscent of the Baroque stile antico (bb. 13–23). The sequential development is underscored by prominent dominant–tonic progressions (e.g., bb. 23–24), the strict rhythmic context, and use of the horn and trumpet in the reprises of the main theme, which give it a popular march- and song-like quality. According to Skalkottas, this main theme dominates until a second ‘cantabile’ theme is introduced in bar 66 (Example 3), which is simple like a ‘folk psalmody’.Footnote 121 A new ‘appassionato sostenuto’ theme follows and is ‘interrupted by a musical descent with a certain variation of the main theme’.Footnote 122 This E-minor theme returns in clear diatonic language within a waltz-like structure before the Coda (b. 209).

Example 2. Skalkottas, Symfonía se klassikón ýfos, bb. 1–38, p. 4.

Example 3. Skalkottas, Symfonía se klassikón ýfos, bb. 64–71, p. 5.

A slower, lyrical second movement follows, which Skalkottas calls a ‘song of the past, a song of the old times – another classical song’.Footnote 123 This Rondo consists of four ‘completely contrasting’ themes with a short introduction, the start of which is repeated throughout the entire movement. According to Skalkottas, the first theme is a ‘pathétique’, like a ‘popular Romance’; the second is ‘polyphonic’; the third is ‘completely rhythmic’; and the fourth is ‘erotic and flamboyantly passionate’.Footnote 124 Skalkottas is clear in his autograph notes that the movement evokes a musical past, writing that it concludes with a ‘musical reminiscence’ in a ‘melancholy and sombre tone’ that harks back to the ‘old times’.Footnote 125

Typical of a classical symphony, the third movement is a scherzo written in 3/4 time (Example 4), followed by a contrasting trio section, before returning to the Scherzo. The Scherzo begins with a brief introduction that ‘defines the rhythm and harmony’ of the movement.Footnote 126 Skalkottas describes the first theme that follows (b. 27) as a ‘Greek village mountain song’.Footnote 127 The theme is subsequently repeated, with the accompaniment creating the effect of, according to Skalkottas, a ‘festival of … lutes and folk instruments’.Footnote 128 The musical progression is ‘varied in rhythms, themes and motifs’, until the repeat of the main theme by the whole ensemble, which creates the impression of a ‘popular celebration’ (laïkó glénti).Footnote 129 The clearly defined structure, with its repetitions and evocation of Greek folk and popular song, combined with the use of simple harmonic and melodic language in the first section, creates a sense of familiarity and stability. A firm and steady sense of pulse and metre, often aligning with the harmonic rhythm, contributes to the overall accessibility of the work, enabling the listener to remain rooted in the unfolding structure. This structure is further reinforced by percussion accompanying the cadential closure of phrases. These cadences are made even more emphatic with four-note phrases, highlighted in the score with a bracket, which interrupt the previously established sense of two-note phrases (bb. 37–8). These four-note phrases recall the steps and rhythmic sequences of Greek folk dance. Moreover, the introduction of a waltz at the outset of the trio confirms the work's typical classical structure (Example 5).

Example 4. Skalkottas, Symfonía se klassikón ýfos, bb. 1–52, p. 16.

Example 5. Skalkottas, Symfonía se klassikón ýfos, bb. 1–43, p. 22.

The Trio opens with a ‘sweet’ 8-bar theme in the oboe, which is then overlaid with a delicate melody in the flute (bb. 19–26), once again reminiscent of the floghéra. The main theme is subsequently introduced in the trumpet and horn; Skalkottas terms this ‘a second folk song’.Footnote 130 This theme is then picked up by the entire ensemble and it is eventually brought to a rousing fortissimo. Framing the fortissimo theme, and before the return of the Scherzo, we hear a short ‘sweet’ pastoral theme in the tonic key (b. 47 of the Trio), accompanied by a descending parallel fifth drone. Following the fortissimo theme, this descending drone is repeated in the parallel minor. The appearance of this pastorale, coupled with the use of percussion in this section, emphasizes the historical aesthetic and sincerity of the work, evoking imagery of a demotic celebration (Example 6). The return of the familiar themes of the Scherzo follows in the final section. Skalkottas highlights the accessibility of this section in his notes, writing that it is characterized by ‘thematic and harmonic simplicity’.Footnote 131

Example 6. Skalkottas, Symfonía se klassikón ýfos, bb. 44–84, p. 23.

Skalkottas labels the final movement – whose tempo marking is Schnell und fröhlich – a ‘joyful march’ of ‘symphonic character and symphonic form’.Footnote 132 The primary theme undergoes a series of repetitions and harmonic and textural variations; the initial repetitions of the theme are, as Skalkottas writes, ‘effortless and cheerful’. The second and third related themes feature several soloistic sections which culminate in a great orchestral tutti with a ‘happy and cheerful marching rhythm’ (b. 114).Footnote 133 The introduction of a second primary theme could, according to Skalkottas, be termed a trio (b. 135), whose musical character is greatly removed from the first theme and is accompanied by a strict rhythm.

A crucial phrase in the composer's programme notes relating to this theme could elucidate an underlying narrative to the symphony. Skalkottas writes that this theme is: ‘melodic and dramatic as if recounting all the ills and ugliness of the world that had dominated it’.Footnote 134 The main part of the theme's development features a seven-part fugue (b. 189) with staccato articulation and rich ornamentation, exuding a playful wittiness. This section transitions into an ‘expansive (multi-instrumental), polyphonic musical section of the march’.Footnote 135 The repetition of the main theme after the fugue resounds in the entire orchestra, and ‘certain chords and fanfares from the orchestra’ bring the symphony to a joyful closing fortissimo. Preceding the ‘joyful fortissimo’ of the coda, there is a reference to the brass fanfare from the first movement, which Skalkottas describes as a ‘brief unique reminiscence’.Footnote 136

Skalkottas's Classical Symphony is characterized by a distinct sincerity, exemplified in the strict adherence to classical formal models and the adoption and adaption of stylistic features typical of the genre. Furthermore, the frequent presentation of folk idioms, fanfares, popular songs, and dance forms throughout the work affect accessibility, orienting the work towards ‘the people’. This sincerity is underscored in Skalkottas's programme note. This text, approximately 1,000 words long, serves as a musical exegesis, imbuing the symphony with extra-musical meaning. In a discussion of ‘form’ and ‘content’ – that is typical of Socialist Realist discourse of the time – Skalkottas writes that ‘The great symphonic form governs the work, from beginning to end; the musical content completely effortlessly echoes both musical phrases and rhythms of the classical symphony as a memory in our time.’Footnote 137 Arguably, however, Skalkottas's most crucial statement comes later, in his discussion of a narrative of patriotic triumph over evil. This narrative is reflected in the accessible, sincere, and demotic music, which builds organically to the optimistic and joyful climax of the final movement:

The joy, the pleasure, the happiness, and the Victory of the people who are freed and liberated from all that which battles against them, and who for the first time learn the Truth is coming in all its glory (I Alítheia érchetai eis olo tis to Fos) is heard with the first sounds of the march that unisono echoes the main theme.Footnote 138

Guided by the composer's writings and experiences during the war, and viewing the symphony as part of a lineage of more accessible and sociopolitically engaged works, Demertzis refers to the work as clearly expressing a ‘political content’, namely the expression of joy and optimism relating to the liberation from the Nazi yoke.Footnote 139 Beyond this, I argue that Skalkottas's programme note anchors his symphony's engagement with classical form, tonal musical language, and accessible features within the scope of Socialist Realism, whose promulgation in Greece promoted these very qualities in relation to the role of artists in the prevailing anti-fascist struggle. Measuring this major tonal work alongside its extensive programme note, against the work of Skalkottas's contemporaries and the repertoire that dominated official musical life, brings it into relation with Xenos's politico-musical activity. This work was associated with the resistance movement, representing the closest approximation to an official Greek Socialist Realist music. Indeed, the mention of freedom, liberation, and victory in Skalkottas's programme rhetorically grounds the symphony in the spirit of this resistance.

Framing the instrumentation of the Classical Symphony in these terms suggests that Skalkottas draws from the stylistic qualities and leftist popular spirit of German works of the Weimar period, from Weill (Skalkottas's former teacher), Hindemith, and the associated concept of Gebrauchsmusik. Weill's active leftist political engagement and his associated promotion of the social and political utility and accessibility of music also likely resonate in Skalkottas's Classical Symphony. Indeed, the use of the wind orchestra in the Classical Symphony could have been inspired by Weill's Violin Concerto, op. 12.

Across the Weimar musical landscape, the remarkable fusion of modernist innovation, political relevance, and emphasis on mass appeal, set against the backdrop of a constellation of political, social, and economic pressures, continued to resonate well after the fall of the Weimar state and the rise of Nazism. While they were not Socialist Realist composers in Soviet terms, Weill and Hindemith drew on shared principles of social relevance, utility, and accessibility, and their music provided valuable inspiration in the context of the promulgation of Socialist Realism in Greece. This promulgation took place in the context of the anti-fascist struggle which promoted Soviet cultural developments more broadly and provided a crucial impetus for new music that would respond to the cultural and political zeitgeist.

It thus becomes possible to consider that Skalkottas drew on the aesthetic-political thought of the Weimar period to respond to the dissemination of Socialist Realism in Greece and meet the requirements of the 1940s. In the Classical Symphony, Skalkottas does not abandon his style – indebted as it was to his formative years spent studying in Germany under Schoenberg and Weill – in favour of creating a narrative symphony referring to resistance and liberation that adopted qualities of Socialist Realism.

Alongside considering the Classical Symphony's roots in the aesthetic-political thought of Germany in the 1920s, where Skalkottas studied, it is important to also examine the work in the context of musical culture and development in Greece, where Skalkottas returned in 1933 and remained until the end of his life. The history of wind ensembles in Greece and their role within society offers greater insight into the motivations behind the work's orientation and its orchestration.

Wind ensembles were introduced across the Balkan peninsula during the Greek Revolution. In the decades following liberation from the Ottoman Empire and the formation of the Hellenic state, they emerged in most Greek urban centres, contributing significantly to cultural life and music education. The ensembles were often referred to with the term ‘philharmonic’.Footnote 140 The use of this term to denote a wind ensemble – despite it traditionally signifying an ensemble incorporating instruments from different families – is noteworthy; it points to the prominence and significance of wind instruments in Greek cultural life at this time. Indeed, in the entry on ‘Philharmonic’ in his Great Greek Encyclopaedia published in 1933, Georgios Sklavos remarks on the synonymous use of philharmonic and wind ensemble in Greece. He writes that ‘according to the presiding Greek custom, this [philharmonic] is the title of an orchestra of woodwinds, brass and percussion. In the West the word philharmonic mainly implies a company of symphonic concerts.’Footnote 141 Furthermore, in the prologue to his treatise on ‘neohellenic music’ published in 1958, Spiros Motsenigos concurs, writing that ‘in Greece, given that the first examples of musical activity appear closely connected with the “band”, the term “Philharmonic” is used to characterize an orchestra comprised exclusively of winds and percussion. In the West however, the meaning is different.’Footnote 142 Through their participation in religious festivals, national parades, and other ceremonies of national significance, wind ensembles became a prevalent feature of cultural life in Greek urban centres that was embedded in the popular consciousness. Their significance is reflected in the appropriation of the term ‘philharmonic’.

During the occupation, the activities of most ‘philharmonic’ orchestras were interrupted.Footnote 143 Indeed, writing about Athens in the period between 1930 and 1950, Motsenigos describes the ‘progressive collapse of the Wind Orchestra’ and more generally, the ‘decline of the Wind Orchestras’.Footnote 144 After the end of the war, most orchestras were re-established and resumed activities that reflected their popular role within society.Footnote 145 The egalitarian spirit of these ensembles was also shaped by and responded to the socioeconomic backgrounds of the musicians within the bands themselves; as Ioannis Plemmenos writes, many of these musicians were from the ‘lower social strata’.Footnote 146

In this light, I suggest that the choice to score the Classical Symphony for wind orchestra emphasizes Skalkottas's otherwise expressed intentions for accessibility, associating it with a tradition of popular, inclusive, communal music-making in the urban centres of Greece. Indeed, Skalkottas clearly intended the symphony to be performed in its entirety, preparing numerous versions of the orchestral score, a piano reduction, and well-presented solo instrumental scores.Footnote 147 We may therefore begin to re-situate the work in the context of key positions argued in Skalkottas's contemporaneous writings, cited previously. These include his arguments in ‘The Power of Symphonic Concerts’, that concerts must correspond to a ‘developing and living context’, and that music could shift away from the ‘absolute or neutral’ in ‘Musical Search’. Skalkottas's emphasis on accessibility as an orientation towards ‘the people’ is echoed in his notes prefacing an edition of Four Greek Dances published by the French Institute in 1948:

when I first planned them (i.e., 1932–33) I had a narrow and intimate (oikeío) musical goal. However, the critical as well as the favourably-disposed … have persuaded me – whether I wanted or not – that this goal has a wider tendency in this humble musical effort of mine (i.e., the Dances) and that it is not the composer who is right but the criticism of the general public.Footnote 148

This sentiment also features in Skalkottas's prologue for his later tonal work entitled The Sea and dated 26 June 1949, making it the composer's last dated text before his death. Here Skalkottas writes: ‘As in its storyline, as in the music, the popular element dominates … The tone of the music is popular from beginning to end.’Footnote 149

Contradicting the persistent narratives that depict Skalkottas's tonal works as entirely divorced from their social and political context, created simply to ‘have fun’, is the composer's apparent homage to the classical symphonic form, his incorporation of folk and popular elements, and his extensive programme note which illuminates a potential narrative.Footnote 150 These features all work to root this major work firmly within the realm of both the popular and the political, situating it within the gravitational pull of Socialist Realism.

Socialist Realisms

Socialist Realist art did not dominate the cultural landscape in Greece in the first half of the twentieth century. Concert programmes continued to be dominated by German, French, and Italian repertoire and, regarding the visual arts, for example, abstraction continued to be defended against representational art. Nevertheless, the Greek engagement with Soviet politics and culture, facilitated by literary, artistic, and musical publications, along with periodicals, cultural events, and individuals, collectively worked to propel the artistic properties of Socialist Realism to the forefront of cultural discourses pertaining to artistic production and its intersections with civic life. Moreover, in Athens, Socialist Realism was promoted against the backdrop of, and in response to, the rise of fascism. As a result, it acquired local significance and achieved far-reaching impact in the context of the popular anti-fascist struggle. In collaboration with a network of co-actors, Socialist Realism therefore played a part in shaping the Greek cultural landscape. Advanced and appropriated primarily by the Greek cultural left, it yoked artists to more popular, accessible forms that ostensibly represented an artistic language that was suitable and appropriate to the conditions of the era. This signals a significant distinction between Socialist Realism in Greece and Soviet Socialist Realism, where the conditions for official approval often resulted in works that have come to be understood as ‘glib’, ‘bland’, ‘corny’, and ‘irredeemably tainted by ideology’.Footnote 151 In Greece, Socialist Realism was instead framed as a kind of countermovement, constituting a form of artistic resistance.

In these terms, I argue that Skalkottas's populist orientation did not emerge as a tabula rasa. While financial and practical incentives likely featured prominently in Skalkottas's emphasis on more accessible musical styles, it is ultimately untenable to consider that the composer was motivated exclusively by the ‘mundane, practical wish to have his music played in Greece’,Footnote 152 or by the need to make his music more ‘commercially viable’.Footnote 153 Through a critical reassessment of Skalkottas's relationship with tonality in context, we can consider how Skalkottas's works recast multiple and complex influences and impulses. In so doing, it becomes possible to nuance the canonization of the composer as either a modernist genius or a conservative sell-out in histories which have defined the political against the non-political in – to borrow from J. P. E. Harper-Scott's work on musical modernism – a ‘mimesis of ideological binaries in whose confines the human subject “must” constitute itself’.Footnote 154 Similarly constructed binaries have also opposed consonance against dissonance, tonalism against atonalism, Romanticism against modernism, and popularity against aesthetic quality.Footnote 155