1. Introduction

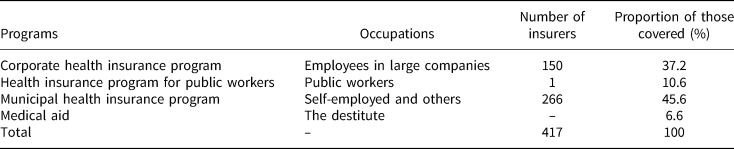

Despite its establishment in 1963, South Korea's (henceforth Korea) social health insurance system did not become operational until 1976, when the Medical Insurance Act was amended to make health insurance mandatory by law rather than a voluntary benefit. Initially, health insurance benefits were gradually extended from employees of large firms (more than 500 employees) to those of small firms (less than 300 employees) and their families. Following its democratization in 1987, Korea finally achieved universal health insurance in 1989. When Korea first established and expanded its health insurance system, the country's policymakers had emulated the basic structure of the Japanese system, which divided insurance coverage between salaried workers and the self-employed (McGuire, Reference McGuire2010: 224). Accordingly, Korea established three types of health insurance programs, as listed in Table 1. The first covered private company employees, and the second covered government employees and private school teachers. The last category of municipal health insurance covered those who were not eligible to join the other two employment-based health programs, such as self-employed, unemployed, and farmers.

Table 1. Structure of health insurance programs in Korea (as of December 1991)

Source: Hoffmeyer et al. (Reference Hoffmeyer, Rowlatt and Lloyd1994: 30).

Under Korea's fragmented health insurance system, those who were insured under corporate-based societies paid lower beneficiary contributions to their health insurance coverage, whereas those in municipal societies had to pay higher contributions for similar benefits. This disparity existed because the former consisted of relatively high-income and low-risk people, whereas the latter consisted of older adults and low-income people. While the corporate health scheme recorded massive surpluses, the municipal health societies suffered fiscal crises (Kwon and Reich, Reference Kwon and Reich2005: 1006). Moreover, municipal health insurance schemes in rural areas experienced chronic losses and, thus, faced huge deficits. To address this issue, Korea decided to integrate its health schemes in 2000, creating a highly ‘solidaristic’ health policy that widened the insurance risk pool and enhanced equity within the public health insurance system (Kwon, Reference Kwon2007).

The Korean health insurance reform of 2000 raises several questions. First, scholars have generally remarked that solidaristic social policies are mostly created in advanced welfare states with a presence of powerful left-wing (Korpi, Reference Korpi1983). However, Korea did not have these conditions. In the 1990s, the country's union density was less than 20%, and left-wing or social democratic parties held no seats in the National Assembly (Lee, Reference Lee2011: 152). The long-dominated right-wing party had relied on clientelistic norms and related networks rather than official and universal benefit packages (Shim, Reference Shim2020). Against this backdrop, in 2000, Korea spent only 3.6% of its GDP on healthcare, which was the lowest among the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries (Jones, Reference Jones2010: 7). Thus, how did Korea achieve its solidaristic health insurance system, even though the political left had only limited power and the country evidently had a small welfare system? Second, in the late-1980s, regular employees in large firms opposed the merger reform because under the integrated health insurance system, they would have had to pay higher contributions to extend coverage to the poor. However, by the mid-1990s, employees of large corporations had changed their stance on the healthcare reform, embracing a solidaristic perspective (Wong, Reference Wong2004; Kwon, Reference Kwon2007). Why did the Korean labor force support such a solidaristic reform when it was at odds with their short-term interests?

Third, how did the modification of policy transfer contribute toward the transformation of the Korean health insurance system? Although the Korean health insurance system was developed based on the Japanese model as mentioned earlier, key practices and rules were modified in the process of policy transfer. While the institutional arrangements of welfare policies are often considered to be resistant to reform (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994), Korea made a fundamental change from its previous health insurance system by merging all health insurance funds. Thus, it follows that in the process of institutional reform, the initial conditions of Korea's revised adoption of the Japanese health insurance system must have affected its future institutional structure and health insurance policies in particular ways, combining with some aspects of the peculiar political contexts in Korea. Therefore, we need to examine how did the distorted adaptation of the Japanese model by Korean policymakers influence the institutional transformation of the Korean health insurance system.

This study examines the institutional and political factors that enabled the Korean government to successfully integrate various health insurance schemes to achieve equity in its universal health insurance program to answer these questions. Specifically, this study emphasizes the role of institutional conflict caused by policy transfer distortions to explain how interactions between conflicting actors and institutional arrangements can trigger institutional change. The policy transfer from Japan to Korea has brought a fusion of new elements with the existing institutional arrangements since politically powerful groups seek to bend some components of institutional rules to accommodate their own priorities and preferences. Thus, the institutional congruence in the health insurance system was seriously reduced when it was translated into Korea. The mismatch between institutional components in the Korean health insurance system has triggered institutional change by creating the distinctive institutional tensions and feedback effects to political and social actors. In Korea, the lack of self-governance in the decision-making processes, a key component of Bismarckian health system, reduced the meaning of fragmented system to a just administrative body. In problem-solving mechanisms, there was the weak commitment for support for rural health insurance schemes since the government wanted to manipulate the subsidy for political reason and lower financial burden. Against this backdrop, ideational changes incurred by the accumulation of political changes and actors' reflection had combined these institutional feedbacks. This combination leads to the coalition shift and puts forward reform outcomes.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the existing theories that have attempted to explain Korea's institutional change and based on their gaps, this study outlines its analytical framework, which combines perspectives on policy transfer and institutional contradictions. Section 3 analyzes the features of the Korean health insurance system and the failed reform trials of the 1980s. Section 4 provides an account of the successful reforms of the late-1990s and the early-2000s. Finally, the last section summarizes this study's argument and presents its theoretical implications.

2. Alternative explanations for institutional change

2.1 Institutional complexity and policy transfer

The new institutionalism school emphasizes the ways in which the ‘rules of the game’ shape political actors' behaviors and structure political battles (North, Reference North1990; Immergut, Reference Immergut1992). Scholars of this tradition call attention to the processes by which initial decisions constrain the political actions of political actors, such as interest groups, during the policymaking process. Initial decisions or existing institutional arrangements can reinforce themselves mainly by shaping the behavior and capacity of political actors over time through the mechanisms of positive feedback or increasing returns (Arthur, Reference Arthur1994; Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2000; Pierson, Reference Pierson2004). However, given that most explanations of institutional change have solely relied on exogenous shocks such as war and other crises, such a rigid institutional approach fails to explain changes from within institutions by not focusing on the endogenous factors that can weaken the existing institutional settings.

Some historical institutionalists have sought to explain endogenous institutional change based on institutional complexity (Clemens and Cook, Reference Clemens and Cook1999; Orren and Skowronek, Reference Orren and Skowronek2004; Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009). Recognizing that institutions comprise various formal and informal dimensions characterized by conflicting institutional logics, these scholars identify several modes and factors of institutional complexity. However, considering the highly complex and conflicted process of institution-building, there is no reason to presume that these sub-components are necessarily linked with each other in coherent ways (Clemens and Cook, Reference Clemens and Cook1999; Pierson, Reference Pierson2000; Jacobs and Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Weaver2014). Therefore, scholars such as Orren and Skowronek (Reference Orren and Skowronek2004) have emphasized how actors exploit the tensions and contradictions between institutions created at different times within political arenas that operate according to their own temporal logic. The ‘non-simultaneity’ of institutional origin creates a mosaic of institutions with layered structures of authority, which may not be neatly fitted into an integrated political regime (Orren and Skowronek, Reference Orren and Skowronek2004: 108). These institutional tensions increased by the simultaneous operation of different sets of rules trigger institutional change.

Second, while Orren and Skowronek (Reference Orren and Skowronek2004) focus on ‘multiple ordering mechanisms’ and contrasting institutional regimes to explain institutional change, some scholars trace internal conflicts within an institution by dismantling its internal dimensions. Scott (Reference Scott2014) contends that institutions are comprised of three basic dimensions: regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive. According to him, much of the impetus for change occurs through endogenous processes, arising out of the conflicts and contradictions between institutional elements. Third, Mahoney and Thelen (Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009) also showed how agents consciously raise institutional tensions and contradictions to justify an institutional change. They examine how gradual or incremental change occurs under the constraints of the prevailing institutional arrangements through processes of layering, conversion, or drift. In addition, institutions are distributional instruments; therefore, institutional arrangements are shaped by the political outcomes of negotiations by actors or the actions of politicians facing short-term electoral pressures (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009; Jacobs and Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Weaver2014). Therefore, despite the dangers of an institutional breakdown, these institutional tensions and the mismatch between institutional components can provide a foundation for an endogenous institutional change.

Although the framework of institutional tensions triggering institutional change can explain the pattern of change of endogenous systems, it has several limitations. First, the mechanisms by which institutional tensions disintegrate the self-reinforcing logic of or path dependence of institutions are unclear. Institutional tensions and conflicts do not always bring about institutional change. In fact, they can do so only if they undermine the particular mechanisms of institutional reproduction on which institutional settings rely (Conran and Thelen, Reference Conran, Thelen, Fioretos, Falleti and Sheingate2016: 63). Second, previous studies have underestimated the role of ideas in the process of institutional change. As institutional tensions are not purely mechanical, conflicts can arise between an institution's ideational and material factors and within the ideas held by the institutional framework. Scholars have noted that institutions preserve their underlying ideas and memories (Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2005; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2010). Thus, the ideational goals or values held by institutions do not often fit into the mechanical and material elements of their existing institutional setting. For example, Lieberman (Reference Lieberman2002) shows how the tensions caused by the gap between institutional goals and the achievement capacity led to changes in the anti-racism policies of the USA. Third, there has been a lack of consideration for the differences in the institutional capabilities of developing countries. The expectations that compliance toward the official rules as seen in advanced democracies would result in high-institutional stability, often does not hold in most developing countries (Levitsky and Victoria, Reference Levitsky and Victoria2009). The operating mechanisms of institutions' self-reinforcing processes and institutional reproduction greatly vary depending on the political context.

In this regard, policy transfers between countries with different institutional capabilities can cause institutional frictions by increasing the internal contradictions and multiplicity within an institutional arrangement (Clemens and Cook, Reference Clemens and Cook1999: 451–452). Policy transfer refers to ‘a process in which knowledge about policies, administrative arrangements, institutions etc. in one time and/or place is used in the development of policies, administrative arrangements and institutions in another time and/or place’ (Dolowitz and Marsh, Reference Dolowitz and Marsh1996: 344). The process of policy transfer hardly leads to ‘isomorphic’ or ‘homogeneous’ outcomes from an original country (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004: 80). However, translating institutional arrangements into local contexts inevitably involves a fusion of new ideas or elements with the existing institutional arrangements. Recent literature on policy transfers has especially focused on the importance and complexity of the institutional context while examining the various outcomes of policy transfers (Sharman, Reference Sharman2010; Marsh and Evans, Reference Marsh and Evans2012). Dolowitz and Marsh (Reference Dolowitz and Marsh2000: 17–19) discuss the complexity of the transfer process and the problem of transferability in this process by demonstrating that uninformed, incomplete, and inappropriate transfers may result in policy failure.

Moreover, the process of intentional or unintentional ‘distortion’ during policy transfers can help indigenize and modify policies in their new location because the transfer process always operates within specific political and historical contexts (Park et al., Reference Park, Lee and Wilding2017). Some recent studies have directly examined the political aspects of policy transfers, such as the characteristics of the borrower government, political actors' preferences, and values embedded in the countries' political relations (Ladi, Reference Ladi2011; Dussauge-Laguna, Reference Dussauge-Laguna2013). Ladi (Reference Ladi2011) focuses on how domestic factors such as actors' preferences mediate the policy transfer process. For instance, agents with policy preferences that align with the existing preferences may facilitate the transfer process. Dussauge-Laguna (Reference Dussauge-Laguna2013) characterizes the bureaucratic battles of the policy transfer process as a ‘contested’ policy transfer in which widely different programs from one country are adopted by another country through a transfer process based on the outcome of their political conflicts and negotiations.

As policy transfers from other countries are sensitive to institutional and political contexts, policy transfers to developing countries are more likely to increase institutional and political tensions. Studies in comparative politics also suggest how institutions operate differently under various institutional conditions (Levitsky and Victoria, Reference Levitsky and Victoria2009). Institutional weakness inhibits the logic of path dependence because the mechanism of reproduction can be easily undermined or disrupted not only by weak expectations, but also by low-institutional capabilities stemming from a power imbalance. An institutional arena is a political battle ground, defined by a continuous interaction between various actors (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009: 8). When policymakers decide to adopt the policy designs of a different country, they can deliberately modify some institutional sub-components to reflect the interests of their own country's dominant groups (Park et al., Reference Park, Lee and Wilding2017). Politically powerful groups seek to bend some components of institutional rules to accommodate their own priorities and preferences. Moreover, strong rule-takers or stakeholders such as big businesses can bend unwritten practices to their own interests because they have the power to enforce informal rules on the society's weak rule-takers, such as their employees (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009: 8). Sometimes formal rules may be disregarded and replaced by unwritten practices, which creates a critical discrepancy between the ‘rules-in-form’ and the ‘rules-in-use’ (Leach and Lowndes, Reference Leach and Lowndes2007: 185). While the original model may have significant institutional coherence within various institutional elements through the gradual adaption to various problems, the modification of critical institutional elements through policy transfer process has unraveled the coordination in the original model (Campbell, Reference Campbell2004; Jacobs and Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Weaver2014). The modifications instituted by politically strong actors create contradictions between institutional elements and their underlying ideas. Losers from a prevailing institution can use these institutional contradictions to persuade and mobilize social actors to challenge the status quo because institutional incoherence can make room for ambiguity or create plurality of meanings in one institution (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2009: 11).

2.2 Ideational change and coalition shift

Although contradictory institutional elements or orders may provide micro-foundations for policy changes, they do not automatically produce institutional shifts. First, institutional change requires losers who are willing to intentionally challenge the status quo. A new institutional arrangement creates two groups competing in an institutional battle – the ‘winners’ – who derive benefits from the change and ‘losers’ – those who incur losses. While some losers of previous legislative battles often simply disappear, other loser groups who mobilize themselves go on to fight for institutional change and attempt to override the previously winning groups (Thelen, Reference Thelen1999: 385). Second, institutional tensions require amplification through political actors' interpretations based on their ideas and orientations. Agents are reflexive and sentient in that they actively reflect the drawbacks of the current system to find better solutions (Kwon, Reference Kwon2003). Political actors constantly (re)interpret the meaning of an institution by (re)shaping their preferences and perceptions based on the changing context, rather than simply repeating the same actions. Through this process, the interaction between ideas and the political context is critical in mobilizing the losers by legitimizing their cases and activating their political activities.

Third, rules are established or operated in a particular context, but over time, such political contexts may be greatly altered as institutions can survive over a long period of time. Thus, such a change in the institutional context can open tremendous space for institutional battles and reinterpretations, which are often vastly different from the intentions of relatively weakened institutional creators (Conran and Thelen, Reference Conran, Thelen, Fioretos, Falleti and Sheingate2016: 57). However, shifts in economic and political contexts do not always abruptly drive radical changes; gradual changes are often mediated by political agents' ideas and perceptions (Gerschewski, Reference Gerschewski2021). Interactions between a series of events such as democratization, regime change, and crisis of movements and the agents' own reflections and deliberations often accumulate to gradually and significantly transform the political contexts of institutions and the power relationship between social actors. A shift in political actors' identities and orientations induce significant changes in their attitudes and interests toward specific policies (Kwon, Reference Kwon2003). Political actors can reshape the meaning of an institution and their interests based on their belief system and core values, which makes them seek legitimacy for their claims about policy change (Béland, Reference Béland2009).

In the long run, these processes tend to change the composition of policy coalitions, as some potential winner groups begin to form coalitions with the reformers (Thelen, Reference Thelen1999: 385). These micro-foundational processes, coupled with institutional frictions and reinterpretation can cause coalition shifts in certain policies, altering institutional configurations by forming a divergent reform coalition. More importantly, institutional arrangements and ideas can diminish the bases of political support enjoyed by existing policies by expanding opposing coalitions (Jacobs and Weaver, Reference Jacobs and Weaver2014). As a consequence of these political activities and conflicts, segments of the groups benefiting from a prevailing institutional setting can move to form a policy coalition with loser or reformer groups. Thus, shifts in political coalitions that underpin institutions and a shift in the power balance between two competing groups can lead to changes in institutional configurations and arrangements (Capoccia, Reference Capoccia2016).

2.3 Data and method

This study utilizes qualitative methods to provide a comprehensive analysis of Korea's healthcare policy reform process. To show how actors' ideas and interests had shaped the political dynamics in their socio-political contexts, process tracing is used in this study (George and Bennett, Reference George and Bennett2005). In the process tracing method, researchers investigate the chain of events or decision-making processes by which initial conditions are translated into final outcomes in a specific case. This study captures the phase and process through which these factors affect the mobilization of reformers, coalition formation, and policy adoption.

Data collection and analysis involved two methods: document analysis and interviews. First, document analysis was conducted based on policy documents and other official communication issued by the government, governmental committees, labor unions, and employer associations to help identify the actors' orientation toward a certain policy. It also uses media reports and secondary literature pertaining to the politics of healthcare reforms. Second, this study utilizes data from semi-structured elite interviews of prominent individuals actively involved in Korea's health reform movement, conducted in the face-to-face mode. The main goal of interviews is to illuminate the major actors' interests and ideas on health insurance reforms. Political actors' ideas, perceived interests on health insurance policy, and the relationship between other political actors were demonstrated by these interviews. The interviewees included a trade union leader, union activists, and a civic activist, who could provide insights into the ideas and interests of their organizations regarding Korea's health reforms. The written informed consent document and participant information sheet were provided to all interviewees.

3. Policy transfer distortions and the call for Korean health insurance reform in the late-1980s

3.1 Institutional conflicts in the health insurance system

Under the non-democratic regime, authoritarian leaders are more attentive to provide private goods to small circle of key supporters to guarantee their regime survival (De Mesquita et al., Reference De Mesquita, Smith, Morrow and Siverson2003). While some authoritarian regimes may achieve significant development in some aspects of social policies, groups that are critical to maintaining the government's stronghold such as public officers and military officers tend to be the main beneficiaries of welfare benefits under such regimes (Knutsen and Rasmussen, Reference Knutsen and Rasmussen2018; Shim, Reference Shim2019). This was also the case in Korea before its transition to democracy. Korea's 1976 amendment to the Medical Insurance Act made it mandatory for all firms with 500 plus workers to build health insurance societies. This bill was highly influenced by the Japanese health insurance system. While drafting the bill, Korean legislators invited Japanese physicians and scholars to learn about the Japanese model (McGuire, Reference McGuire2010: 224). The Korean health insurance system emulated the basic structures of the Japanese system, which categorized beneficiaries between salaried workers and the self-employed. In 1979, another health insurance program for government employees, military officers, and private school teachers came into effect. In 1987, Korea's democratization shifted the political landscape of welfare policies. A nascent democratic government is obligated to pay more attention to the masses due to the combination of the genuine competition in elections and multi-party competition in the legislature (Haggard and Kaufman, Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008; Shim, Reference Shim2019). Thus, following its democratization in 1987, Korea achieved universal health insurance in 1989 by creating a municipal insurance program for the rural population and the self-employed.

Democratization creates expectations among citizens that they would not be excluded from official welfare programs and that the benefits would be equitably distributed. Extending the universal right to healthcare to all citizens requires governments to incorporate the concept of equity of healthcare services and governmental responsibility for healthcare in their healthcare systems (Blank and Burau, Reference Blank and Burau2014: 110). Despite achieving political democratization and universal healthcare, Korea could not shake off the legacies of its authoritarian social policies, demonstrating that democratic transition does not necessarily guarantee greater inclusion of the public into existing social benefits (Wong, Reference Wong2005). In many ways, due to the distorted policy transfer of the Japanese healthcare system into Korea, its fragmented health insurance system was more beneficial to public officers and employees in large firms than farmers and the others. At the time, the universal healthcare program still used the previous framework, and the newly launched program also emulated the Japanese model.

However, there were some key differences between the two systems. When policymakers decide to adopt the policy designs of another country, they deliberately modify some institutional sub-components to reflect the interests of bureaucrats and dominant groups (KIHASA, 1991: 125–127; McGuire, Reference McGuire2010: 224). Accordingly, this type of modification, when implemented in Korea, created two major institutional conflicts within the Korean health insurance system. The first was the lack of self-governance in the decision-making processes. Before the integration reform of 2000–2003, Korea had more than 300 non-profit health insurance societies, which following the Japanese health insurance system, exhibited a para-public administrative structure. According to the 1987 Medical Insurance Act and its Presidential Decree, employees had the right to participate in the decision-making processes of their insurance societies by electing 50% of the steering committee members and directors of their health insurance schemes, respectively. However, self-governance of health insurance societies has hardly been achieved in Korea. In practice, businesses generally appointed human resources personnel to represent subscribers and unilaterally used their reserved funds for corporate health insurance societies with no discussions regarding health insurance schemes (Lee, Reference Lee1998).

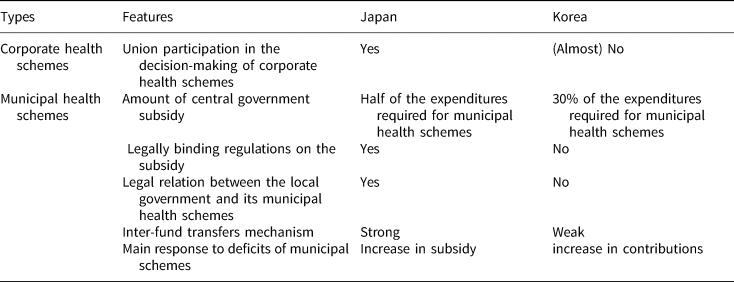

The second important conflict was the significant gap between the idea of universal health insurance and weak governmental commitment for this system. Although the universal healthcare system contains the concepts of equity in healthcare services and governmental responsibility, as mentioned above, the Korean government did not confer credible commitments to supporting financially distressed municipal health societies. When Korea emulated the Japanese health insurance system, its policymakers deliberately reduced the level of institutional commitments to support financially distressed municipal health societies, as shown in Table 2. First, the number of subsidies for municipal health schemes in Korea was left to the discretion of the government, while in Japan, the central government had to bear – with strong legal regulations – approximately half the expenditures incurred by municipal health insurance schemes (Campbell and Ikegami, Reference Campbell and Ikegami1998). When municipal health schemes began in 1988, the Korean government assured the insured that their contributions would be significantly subsidized. However, the Medical Insurance Act of 1988 did not adequately institutionalize this promise. The government had the discretion to manipulate the size of subsidies and, thus, those subsidies were subject to change depending on various political and economic circumstances (Kim, Reference Kim2011: 102).

Table 2. Comparison between Japanese and Korean health schemes

Source: Own table.

Second, municipal health societies in Korea had no legal relationship with the local government. In Japan, municipal health insurance schemes have been directly managed by local governments since the 1948 Citizen Health Insurance Act (Campbell and Ikegami, Reference Campbell and Ikegami1998). Additionally, while their Japanese counterparts dedicated approximately 10% of their annual spending to balance the budgets of their health insurance societies, Korean municipal governments did not have to include their health insurance societies in their budgets. Due to these provisions, Korea's municipal health insurance societies relied on a steep increase in contributions in response to the serious fiscal crisis and huge deficits they faced in the late-1980s (Federation of Korean Medical Insurance Societies, 1997: 570). Through these mechanisms, political leaders can manipulate public support by utilizing the financial aid to health insurance schemes as ‘discretionary’ subsidy (Shim, Reference Shim2019), while privileging the key supporters of the regime such as public officers, big business, and its employees, at the same time, by providing more generous conditions under the health insurance system.

3.2 Problems in the Korean health insurance system and mobilization for health insurance integration reform

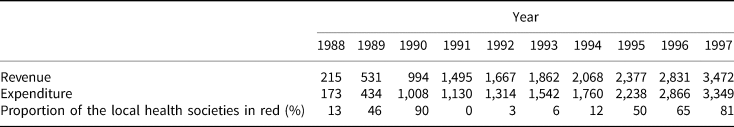

The municipal health insurance schemes, which were already vulnerable to structural issues, especially for self-employed and retired individuals, also began to suffer from financial problems. First, municipal health schemes only covered those who were older and poorer than the people covered by employment-based health insurance. Those over 65 comprised of 8.15% of the rural municipal health schemes' members in rural areas in 1997 while only 5.3% of corporate-based health schemes (Jo, Reference Jo2008: 279). Second, the size of the municipal health insurance schemes made them less efficient and more vulnerable to financial shocks, preventing them from effectively tackling their fiscal deficits. In Korea, approximately half the municipal health insurance schemes recorded deficits in 1989 as shown in Table 3. Most of these schemes experienced financial distress due to the rising health expenditures and the reduced ability to finance health insurance benefits. In addition, the weak financial capability of municipal health insurance plans caused significant disparity between employment- and residence-based health societies. At the time, an enrollee in a rural municipal health insurance scheme contributed 2.36% of their income compared to 1.19% by wage earners (Dongailbo, 1990).

Table 3. Financial trend of the municipal health societies from 1988 to 1997

Source: Federation of Korean Medical Insurance Societies (1997: 574). Unit: billion won, %.

Against this background, the call to integrate all health insurance schemes became louder. In Korea, when municipal health schemes were initiated in the late-1980s, farmers mobilized to protest against the unequal and ill-managed health insurance system (Wong, Reference Wong2004; Kwon, Reference Kwon2007). The problem-solving practices used in Korea's policymaking contradicted rural citizens' expectations from the universal health insurance system, which was based on equity and governmental responsibility. The mismatch between the ideas underlying the public health insurance system and its weak institutional capability created friction. Those insured by the municipal health societies – mainly the farmers – were outraged by the broken pledge to support their health insurance schemes and became strong proponents of reforming the health insurance system (Kwon and Reich, Reference Kwon and Reich2005: 1014). After the well-organized farmers started leading protests, they were joined by progressive civil movements that also supported the health insurance integration reform (Lim, Reference Lim2010: 145). These progressive civil movement groups were a legacy of Korea's democratization movement, and they brought out serious defects in the country's health insurance system.

In addition, activists criticized the government for not taking responsibility for municipal health insurance schemes. Two grassroot movements comprising farmers and civic associations spontaneously joined forces to fight for better healthcare services. Initially, their requests for the health insurance reform were fairly broad and ambiguous. They called for an increase in government subsidies and a discount on their contributions. Later, they directed their demands toward the consolidation of all health schemes that were divided by occupation, which would signal a strong commitment to correcting crucial problems in municipal health insurance schemes (Lim, Reference Lim2010: 144). This movement became the main vehicle through which farmers and protesters attempted to raise political awareness on healthcare issues among themselves and the public (Kwon and Reich, Reference Kwon and Reich2005: 1012–1015).

Business groups were strongly opposed to the merger, claiming that this move would increase the employers' contributions and governmental subsidies (Kwon, Reference Kwon2007: 155–156). The labor movement was also not committed to supporting a solidaristic health insurance reform because the fragmented health insurance system benefitted the workers in large corporations, and labor groups were preoccupied with organizing militant workers' movements (Wong, Reference Wong2004: 94). At the time, the union movements needed to mobilize union members to increase their collective bargaining power at the level of individual companies. Meanwhile, the provider groups' positions regarding health insurance integration were often inconsistent and ambiguous. Medical providers prioritized their own reimbursement but did not have strong incentives to take collective action on administrative structural reform.

In 1989, a bill on integrating the health insurance system was passed in the National Assembly, led by liberal opposition parties, who occupied the majority of the Korean National Assembly. The two center-left opposition parties, the Peace and Democratic Party and the Reunification Democratic Party, particularly showed sympathy with rural residents and reflected their electorates' request for the integration reform (Lim, Reference Lim2010: 145). However, President Roh Tae-woo exercised his veto power to scrap the merger reform as the merger would increase employers' contributions and governmental subsidies for healthcare. Thus, the absence of labor groups in the coalition for the healthcare reform contributed to its failure in the 1980s (Wong, Reference Wong2004).

4. Coalition building and implementation of the health insurance integration reform in the 1990s

4.1 Interactions between institutional and ideational factors

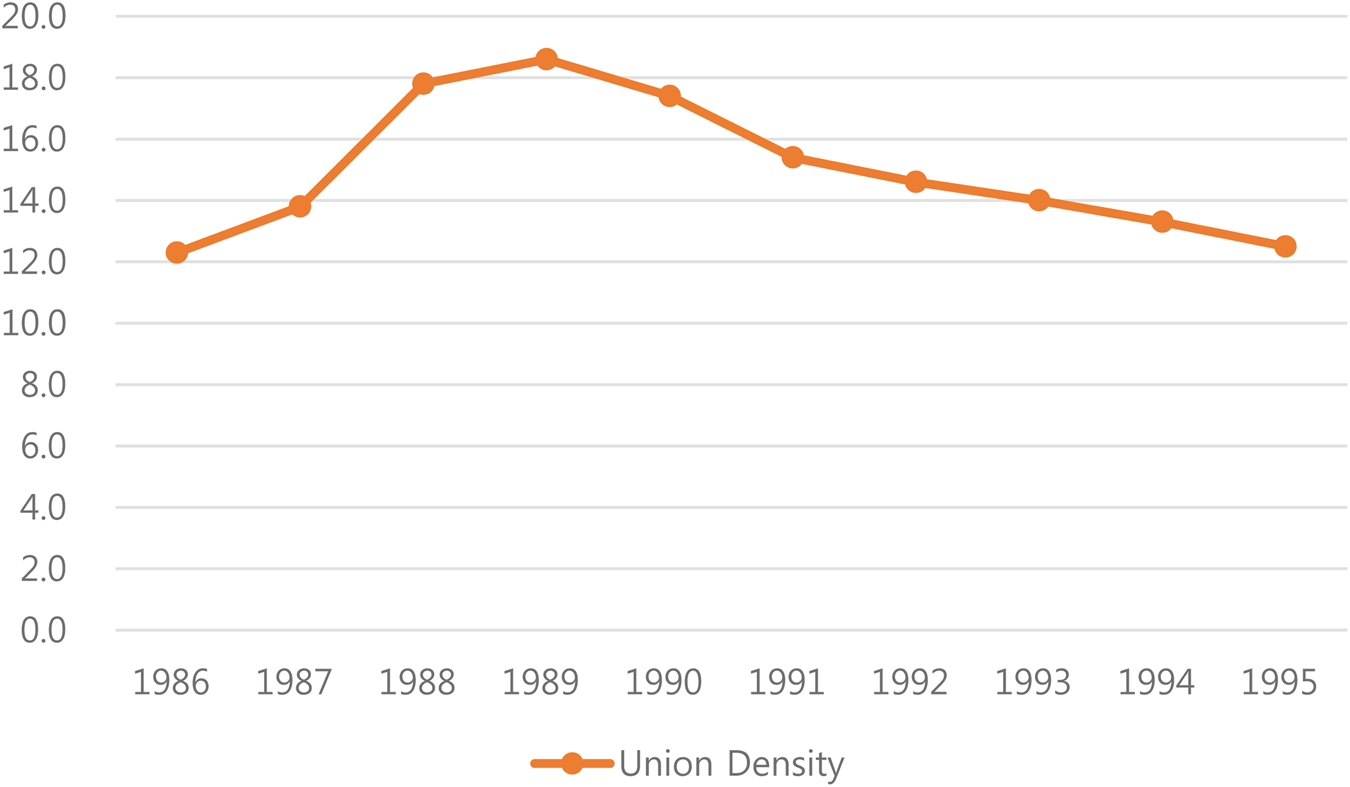

In the mid-1990s, Korean labor movements underwent an ideational shift toward ‘social movement unionism,’ adopting a militant position during the initial stage of the health reform. They were especially concerned with members' economic conditions and attempted to improve them through militant industrial actions (Mo, Reference Mo1996). However, faced with serious internal and external threats, progressive labor unions – led by the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) – dissolved narrow group identities to create a broad coalition for achieving egalitarian social policies (Rowley and Yoo, Reference Rowley, Yoo, Benson and Zhu2008). In the early-1990s, general strikes and other mobilizations ended in failure not only due to brutal government repression but also due to the cynical middle-class attitude toward labor movements in terms of union membership, as shown in Figure 1, the proportion of organized workers in Korea peaked at 18.6% in 1989 but fell back to about 13.3% in 1994. In addition, it was hardly possible for workers to participate in official institutional bodies which would decide economic and social policy-making process at the national level (Lee, Reference Lee2011).

Figure 1. Union density and labor dispute in South Korea, 1986–1995.

Source: OECD Trade Union Dataset (https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TUD#) (accessed 25 August 2021). Unit: %, year.

Frustrated by the failure of its militant strategy, decrease in union membership, and the marginalization of workers in political arena, labor groups sought to change their identity by embracing social reform and other progressive issues (Gray, Reference Gray2007). The KCTU had also started adopting a more socially conscious orientation in the mid-1990s by pursuing wider public interest and proposing a closer partnership with civil movements. Both the fierce debate about the unions' orientation and the dense networks between labor and reformers (such as farmers and civic activists) were credited with the change in labor's position through intensive ‘policy learning’ (e.g., Mo, Reference Mo1996).

The ideational shifts in the union leaders that occurred through their own deliberations on union identity and interactions with other civil movement groups afforded completely different meanings to the healthcare reform. These new interpretations of the fragmented health insurance system fostered by the institutional features of the decision-making processes could affect the ‘legitimacy’ of the prevailing system's new interests. Significantly, the absence of the self-governance principle in Korea became apparent and in the mid-1990s, the labor movement began to criticize the previous management of health insurance societies for favoring business. More importantly, this distortion of practices reduced individual health insurance societies to no more than a governmental body that collected contributions (Kwon and Reich, Reference Kwon and Reich2005: 1107). The occupational divisions in the health insurance system had no special meaning and recognizing this fact helped the Korean labor movement change its position on health insurance reform and adopt a social movement orientation. According to the multiple interviews conducted in this study, the labor leaders and activists thought that company-based health insurance schemes could be merged into other health schemes.

The decision-making processes also shaped the interests of trade unions. Compared with trade unions in other countries that had social health insurance systems, Korean trade unions had fewer institutional incentives to support their country's fragmented health insurance system. Although core members did enjoy economic benefits from this system, their organizational benefits were limited due to their exclusion from company-based health insurance schemes, which made it easier for them to shift their stances on health insurance reform in the mid-1990s, when Korean labor movements adopted a social movement orientation. Thus, these trade unions had begun prioritizing their long-term organizational benefits for short-term economic ones by joining forces on health insurance reform.

By interacting with labor's ideas, Korea's problem-solving practices had two significant effects on health insurance reform. First, these institutional factors shaped the particular interpretations of governmental responsibility for the health insurance system. When the low credibility of Korea's problem-solving practices was combined with Korean labor movements' social movement orientation, the meaning of the fragmented health insurance system changed (based on the interview with a policy director of the KCTU, 23 April 2015; interview with a Health and Medical Workers' Union official, 14 May 2015). When a universal public health insurance system is initiated, people expect their government to take responsibility for providing healthcare to all citizens, thus creating an expectation of fairness (Blank and Burau, Reference Blank and Burau2014: 110). However, when the actual governance of the insurance system collides with this expectation, people may delegitimize the institutional configuration. Against this background, the health insurance system was seen as a symbol of the social exclusion of the disadvantaged and as a malfunctioning social policy stemming from an irresponsible government. The union leaders thought that their government was barely concerned about the welfare of its less fortunate citizens and that it had failed to establish a fair and trustworthy health insurance governance (based on an interview with a former Vice Chairperson of the KCTU, 29 May 2015). Similar to the farmers and civil activists, they also believed that rather than the union's participation in corporate health insurance schemes, the integration reform was the only possible solution for Korea because of the country's weak commitment to financial aid for municipal health societies (based on an interview with a Health and Medical Workers' Union official, 14 May 2015).

Second, these problem-solving practices also affected the political dynamics of reform in Korea by shaping the organizational incentives for labor to participate in the policy coalition advocating integration reform. The massive mobilization of rural areas also raised public awareness of the health insurance reform and provided a political opportunity to build a policy coalition between farmers and Korean workers (based on an interview with a Health and Medical Workers' Union official, 14 May 2015). When Korean trade unions called for solidarity with other civic groups, they had to determine the critical issues to focus on, because lacking effective organizational capabilities, they could not realistically target all the social movement agendas. Although Korean trade unions raised various social reform issues, such as education, judicial processes, and media-related reforms, their organizational capability was limited (based on an interview with a policy director of the KCTU, 23 April 2015). However, they prioritized supporting the health policy reform because of the high public awareness regarding this issue (based on an interview with a former Vice Chairperson of the KCTU, 29 May 2015). In addition, when the KCTU mobilized its members on this issue, the organization was influenced by existing problem-solving practices and framed health insurance reform as one of the most critical problems among all Korean social reforms (Baek, Reference Baek2001: 165; Lim, Reference Lim2010: 151).

4.2 Formation of a broad policy reform coalition and its policy outcomes

Labor movements began to support the integration of the health insurance system. Under the banner of the ‘fight for social reform,’ the KCTU created an industrial strategy to establish a linkage between wage bargaining at the company level and health insurance reform at the national level (Gray, Reference Gray2007: 130). This strategy was successful in triggering political campaigns for the merger reform and in raising the profile of this issue on the civil society agenda (based on an interview with a former Vice Chairperson of the KCTU, 29 May 2015). In this context, farmers, labor movements, civil groups, and progressive social policy academics organized an organization known as the ‘Solidarity for the Integration of Health Insurance’ in 1994, which proved to be crucial for the health policy coalition. Putting the failure of achieving the integration reform in 1989 behind itself, the coalition sparked a heated debate on the consolidation of all health insurance entities.

Compared to the first reform attempt, this time, the boundary of the coalition for policy change expanded as labor movements and numerous civic groups in economic and social policy areas joined the struggle (Wong, Reference Wong2004: 96). While the consolidation reform itself could have disadvantaged regular workers in large enterprises, their organizational goals caused them to transform their strategies and preferences. In return, workers obtained broader support from farmers, liberal parties, and civil activists as a sort of political exchange. The reformers also obtained support from prestigious civic organizations such as the People's Solidarity for Participatory Democracy and the Citizens’ Coalition for Economic Justice. These two civil associations were regarded as reformist and rational rather than radical and ideological, and their positive images were helpful in broadening support for the reform (based on an interview with a former a civil activist from the ‘Solidarity for the Integration of the National Health Insurance,’ 27 May 2015).

The formation of the new and large coalition strengthened the political power of the reformers (Kwon, Reference Kwon2007). First, the coalition attempted to gain access to the political arena. They had strong connections with a liberal opposition party, which was a strong supporter of integration reform. In November 1994, the ‘Solidarity for the Integration of Health Insurance’ filed a petition calling for a health insurance merger; the petition was submitted to the National Assembly through an opposition legislator. Second, the coalition initiated several discussions at large corporations to persuade workers to support health insurance reform. Several key civil activists and the KCTU leaders visited some large-scale corporations to persuade the leaders of politically meaningful enterprise unions to participate in the merger reform, stressing the common interests of labor and civic movements in the agenda on social welfare (based on an interview with a former Vice Chairperson of the KCTU, 29 May 2015).

Opposition candidate Kim Dae-Jung, a long-time supporter of the integration reform, won the presidential election in December 1997 amid a catastrophic economic crisis: the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Driven by a serious economic crisis and regime change, President-elect Kim pushed economic, labor, and welfare reforms. To address health reforms, he established a special committee for social reform that covered health insurance issues (Kwon, Reference Kwon2011: 660). In addition, he initiated a tripartite committee to facilitate negotiations with business and labor through a series of economic and social reforms. These efforts made the integration of all health insurance schemes much easier compared to previous attempts, which had faced strong vetoes from legislators supporting business interests (Kwon, Reference Kwon2011: 661). The successful compromise achieved by the tripartite committee enabled the legislature to integrate all types of health insurance schemes. Thus, in February 1998, the tripartite committee agreed to legislate for the full merger by the end of the year. Based on this decision, Korea's multiple social insurers were merged into a single National Health Insurance Corporation in 2000.

During this period, there were three major ways in which the reformers reinforced their coalitions to secure the integration reform. First, the reformers including the KCTU framed the fragmented health insurance system as a by-product of Chaebol governance, which was blamed as one of the main culprits for the economic turmoil, known as the ‘1997 Asian Financial Crisis’ (based on an interview with a former Vice Chairperson of the KCTU, 29 May 2015). Second, the rivalry between the two peak unions – ‘KCTU and the Federation of Korean Trade Unions (FKTU)’ – helped each group establish and reinforce their identities. The former sought to taint the latter's image as an exclusionary economic bigot as the FKTU fought against the full-scale merger of the health insurance system claiming that the integration would increase the contributions demanded from workers. Finally, the labor reforms between 1996 and 1999 consolidated the progressive coalition. At the end of 1996, the ruling party passed a bill targeting the labor market to ease the strain of layoffs. Between December 1996 and March 1997, labor unions organized large-scale strikes against a more flexible labor market policy. Facing such strong opposition, the government had to cancel the revised Trade Union Act. Through this event, progressive civic more actively embraced labor issues and upheld solidarity with labor, and vice versa. Thus, in 2000–2003, the broader coalition led to the passage of bills on the health insurance merger of the various health insurance schemes. Although the conservatives and some wage workers attempted to thwart the government's intention and restore the fragmented health insurance system, the coalition of farmers, labor, civic activists, and the new ruling party successfully led the legislature to integrate all types of health insurance schemes. Although the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis as exogenous force has served as catalyst by weakening the opponent groups, it could not account for the dynamic process of reshaping main actors' attitudes on the health insurance reform. Institutional stability was already significantly shaken before the 1997 Asian Financial crisis. In short, the seeds of the demise of the former health insurance system have been already implanted in its institutional design and practices.

5. Conclusion

This study aimed to examine the institutional and political factors shaping Korea's successful health insurance integration reform. The country's health insurance system was initially divided based on employment and labor market status by adopting the Japanese model. The attempt to implement an integration reform in the late-1980s was unsuccessful because only a narrow policy coalition supported the change. By mid-1990s, labor movements joined the coalition, and Korea implemented the integration of its different health funds in the early-2000s, choosing a different path from its original health insurance model.

This study contributes to the literature on institutional change, preference formation processes, and policy transfer, especially concerning labor and welfare politics. First, this study demonstrates how the distorted policy transfer disintegrates the self-reinforcing effects of the existing institutional arrangements. Although previous institutional accounts have emphasized the complexity and diversity of institutions, they did not pay attention to how the various features of the policy transfer process shape a high degree of institutional contradictions. The institutional capabilities of developing countries are weak and thus powerful groups seek to bend some parts of the institutional rules to accommodate their own interests. When policymakers in Korea adopted the Japanese health insurance system in the 1970s and 1980s, some components of the health insurance system were modified. The self-governance of health insurance societies has hardly been achieved in Korea. This distortion of practices reduced individual health insurance societies to no more than a governmental body that collected contributions. In problem-solving mechanisms, there was the weak commitment for support such as loosely institutionalized finance assistance for rural health insurance schemes. In the long run, these mismatched institutional components stemming from distorted policy transfer has raised the institutional tension since some institutional practices conflicted with the ideas embedded in the prevailing health insurance system. This incongruence in the prevailing institutional arrangement provided space for institutional change by giving rise to the mass mobilization of disadvantaged groups in the existing institutional setting.

Second, this study demonstrates how ideas reinterpret actors' preference by combining their own reflections and policy feedbacks stemming from institutional practices in the process of institutional change. Political agents continuously reinterpret the meaning of institutions by reshaping and adjusting their preferences and perceptions of those institutions. This process of institutional change is much more likely to succeed when institutional conflicts and policy feedback provide micro-foundations for it. Furthermore, when actors' ideas about their broad orientation interact with institutional incongruence, such interaction could create specific policy ideas that challenge the prevailing institution. As the KCTU had also started adopting a more socially conscious orientation in the mid-1990s, they began to reinterpret the meaning of the health insurance system in Korea.

Third, this study contributes to the political dynamics of the policy coalition formation. Although existing studies have also emphasized the cross-class coalition in Korea's health insurance reform movement (Wong Reference Wong2004; Kwon, Reference Kwon2007), they overshadowed the micro-foundation of this alliance. Most of these studies assumed that labor and progressive civil movements were inherently supportive of the integrated health insurance system. However, workers' support for solidaristic welfare development cannot be taken for granted as the labor class is often divided when facing specific welfare issues (Nijhuis, Reference Nijhuis2009). Their subsequent support was contingent on political and institutional contexts. Actors can shape their preferences by reinterpreting the meanings of institutional arrangements. The shift in their attitude toward prevailing institutions can be explained by the interactions between the actors' ideas and institutional arrangements. By examining this process, this study emphasizes the interaction between institutional frictions and feedback stemming from a distorted policy transfer and ideational changes, which provides scope for the reformers to engage with the health insurance reform. The transformation of major political actors' orientations can lead to shifts in their stances on specific policy reforms by forming a broad cross-class coalition.

Seongjo Kim is Assistant Professor in the Department of Social Studies Education, Sunchon National University, Sun-chon, Korea. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Sheffield, UK. His main research interests lie in comparative welfare politics, social policy, and political economy. His current research interests include the relationship between welfare and electoral politics in East Asia.

Sun-Woo Lee is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science and Diplomacy, Chonbuk National University, Jeon-ju, Korea. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Glasgow, UK. His recent research has been published in the Japanese Journal of Political Science. His research interests include presidency and political institutions in comparative perspective.