Introduction

Recent investigations of the Camel Site in the Jawf region of Saudi Arabia (Figure 1) have provided a Neolithic date for a group of naturalistic reliefs depicting life-sized camels and equids (Charloux et al. Reference Charloux2018; Guagnin et al. Reference Guagnin2021). The site documents a level of skill, technical knowledge and communal effort that is unprecedented in the Near East. In the wake of its discovery, other 2D engravings of large camels (measuring approximately 1.3–2.5m in length) have brought increased attention to a region that is, archaeologically, still poorly explored. Six regional traditions of large camel engravings have been identified (Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Guagnin and Norris2020). Among them is a tradition of large, naturalistic engravings, which stands out due to both its geographical distribution and a number of stylistic traits that suggest a close relationship with the Camel Site reliefs. Here we present newly documented panels that provide insights into the mobility patterns of Neolithic engravers within the Nafud Desert.

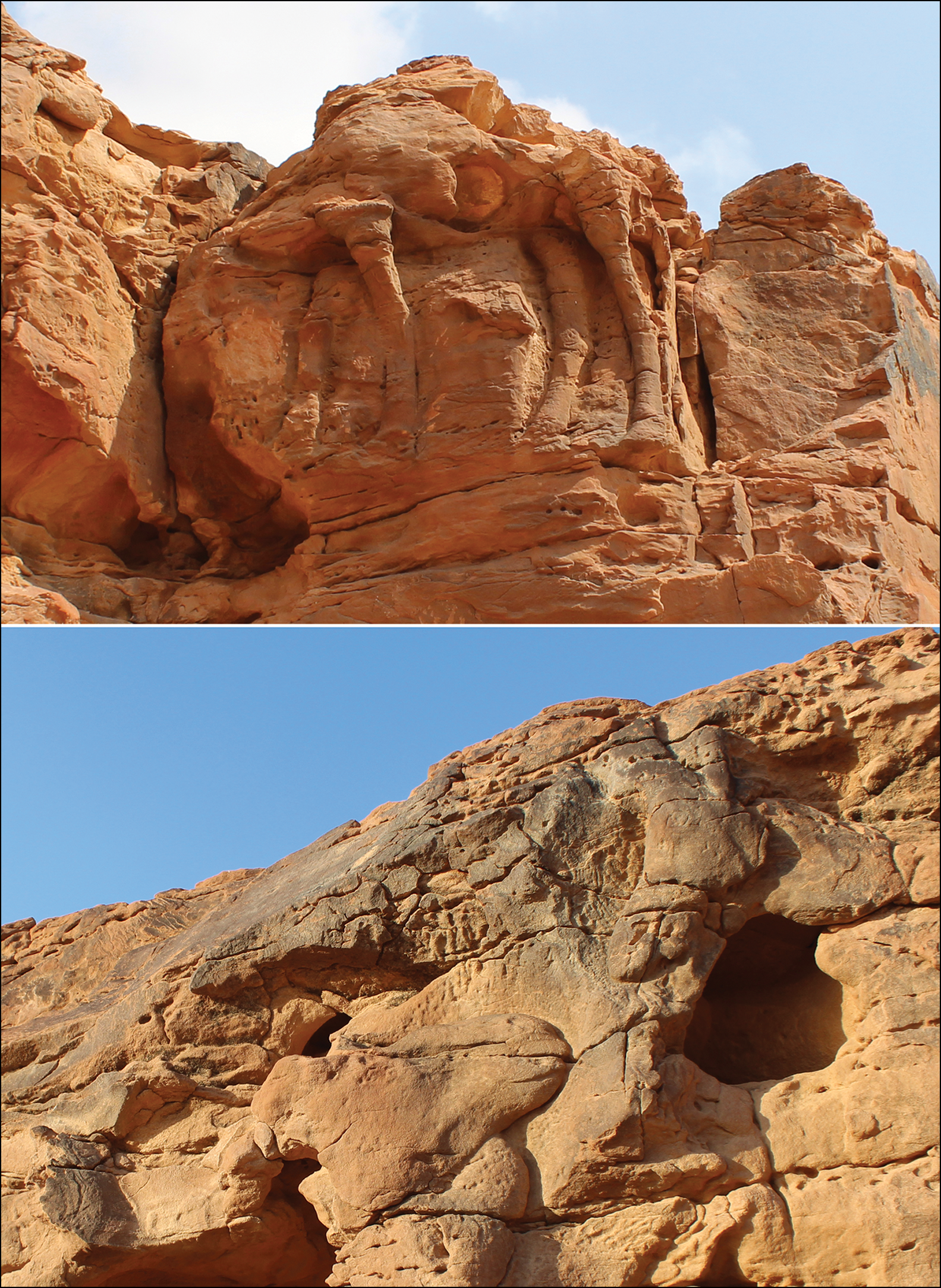

Figure 1. Naturalistic and life-sized camel and equid reliefs from the Camel Site: top) camel relief showing the side and underside of the body with four legs (Panel 11); bottom) camel (left) and equid (upper right) facing each other (Panel 2) (photographs © Camel Site Archaeological Project).

Large, naturalistic camel engravings

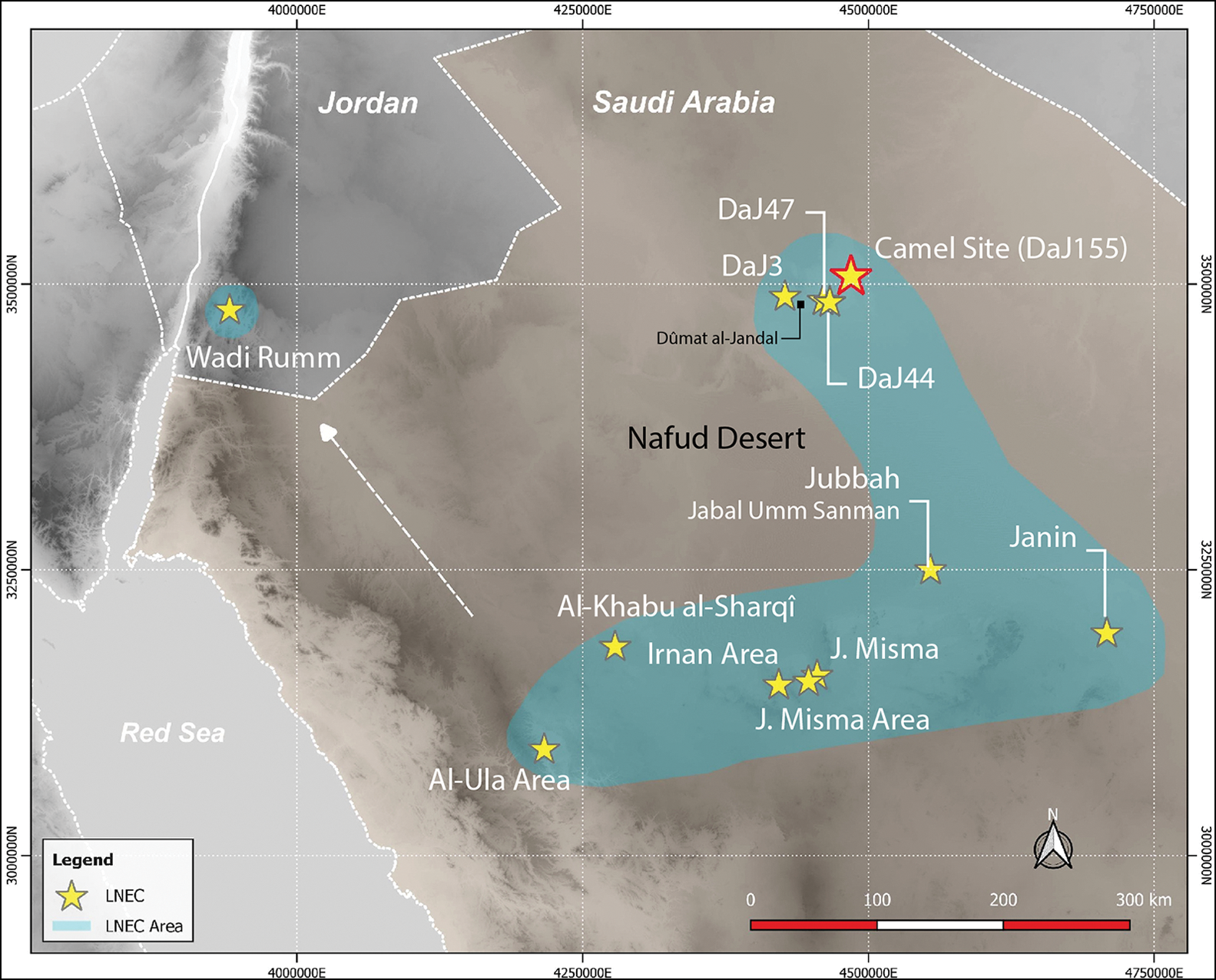

To date, a total of 27 panels, depicting 37 large, naturalistic engravings of camels, have been identified by the authors from previous publications, online sources and recent fieldwork, although new panels are regularly brought to our attention by members of the public. These engravings are distributed across 11 rock-art sites situated around the edges of the Nafud Desert, with a twelfth site located in southern Jordan (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of large, naturalistic engravings of camels (LNEC), shaded in blue. Known sites are shown with yellow stars (figure © G. Charloux).

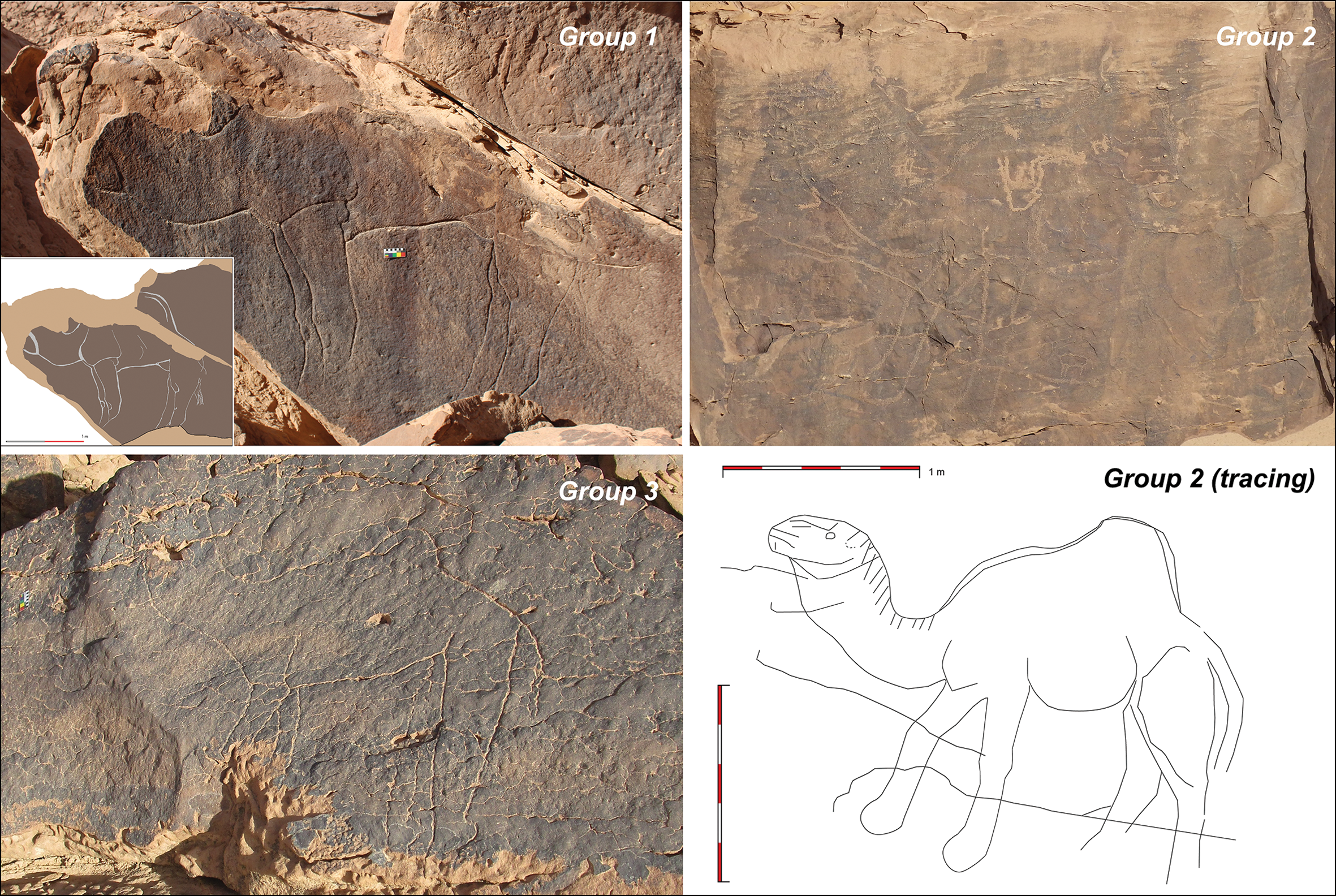

All of the camel engravings from this tradition share common, characteristic traits, including a naturalistic outline and the frequent depiction of details, such as hair, eyes, callosities or ribs. The camel figures are always depicted in profile (facing both left and right), and the position of the legs shows both movement and perspective. The known representations can be subdivided into three main stylistic groups based on their technical sophistication and the amount of detail captured in their outline and features (Figure 3) (see also Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Guagnin and Norris2020). In this article, we focus on the most naturalistic engravings, as such representations of anatomic details require much time and skill. This allows for a better comparison of the engraving processes than quickly produced, more stylised representations.

Figure 3. The level of detail visible in large, naturalistic camel engravings varies and three distinct groups can be identified: Group 1) highly detailed camel engraving from site DaJ44; Group 2) camel from site DaJ3, with only some details represented; Group 3) outline of a camel from site DaJ44, lacking any detail (figure © Dumat al Jandal Archaeological Project (DAJAP), G. Charloux, C. Poliakoff and M. Guagnin).

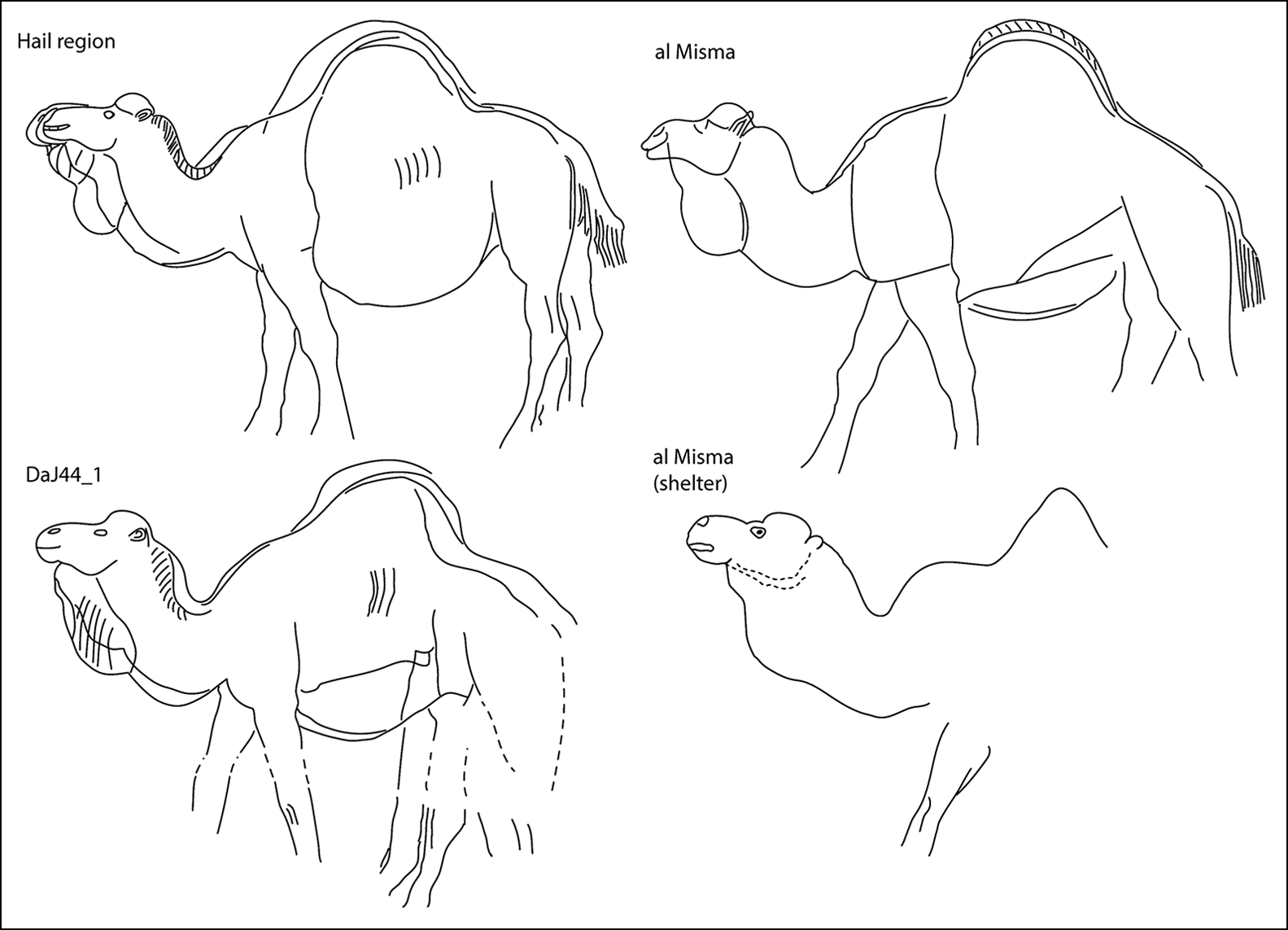

The similarity observed between four highly naturalistic engravings is striking (Figures 4 & 5). Not only do all four share comparable outlines, details, and elements of bas relief, but the actual process of creating the engraving also appears to have been similar. While one of the four panels appears unfinished, the remaining three display an identical process of reshaping the hump, and two appear to show identical reshaping of the neck or abdominal lines and depiction of the tail (Figures 4 & 5). The extent of these similarities exceeds the study of rock-art style and suggests the possibility that they were created by the same individual(s). Three of the engravings were identified in the southern Nafud Desert, while the fourth is located in Jawf Province, to the north of the Nafud Desert, approximately 300km distant (Figure 2). It is possible, therefore, that the engravings were revisited and reshaped repeatedly by the same individual(s), following an identical pattern of change and improvement. Thus, these panels may represent the first archaeological evidence of a repeated pattern of movement across the Nafud Desert that can be linked directly to an individual artist or a small artistic community.

Figure 4. Comparison of four near-identical engravings: top left) Jebel al-Misma area (reproduced with kind permission from S. Al-Ruwaysan); top right) Jebel al-Misma (© C. Baumer); lower left) Panel DaJ44_1 from Jawf Province (© DAJAP). Note that the outline has been re-engraved and thus appears to be lighter in colour; lower right) engraving found in a shelter at Jebel al-Misma, with a second camel superimposed and an earlier gazelle carving—a tracing is provided in Figure 6 (© M. Guagnin).

Figure 5. Tracings of the four camel engravings with greatest similarity (after Figure 4). The two camels on the right have been mirrored for better comparison (© G. Charloux and M. Guagnin).

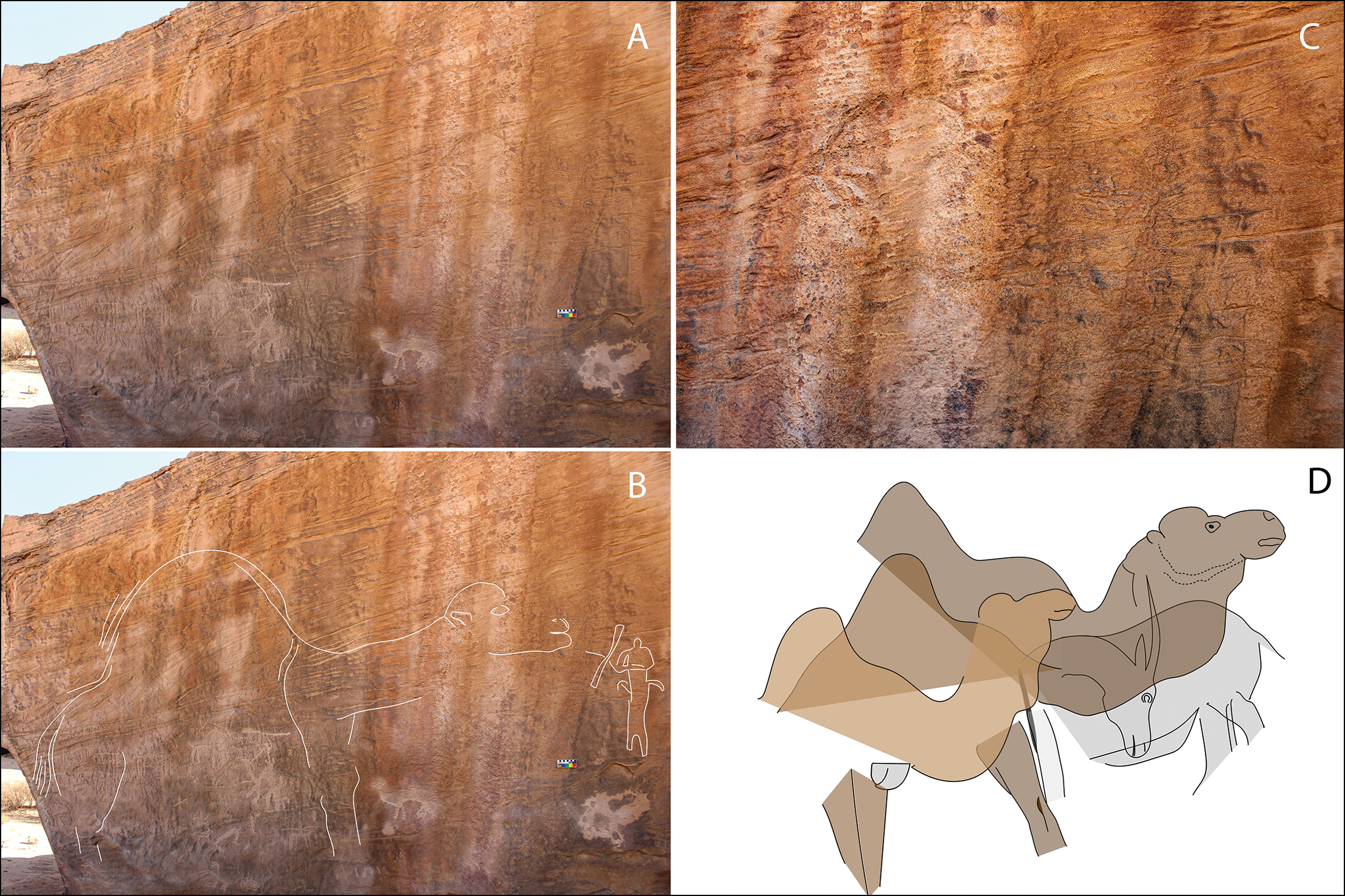

Figure 6. Panels with superimpositions: A) panel at Jebel al-Misma depicting a camel and Neolithic hunter (note that the hunter was possibly added later); B) tracing over A; C) closeup of the camel's head and the upper body of the hunter holding a bow and arrow; D) tracing of the panel from the Jebel al-Misma shelter (based on Figure 4), showing a sequence of three unfinished camel outlines, as well as earlier engravings of a gazelle and an equid (© G. Charloux and M. Guagnin).

Artistic links with the Camel Site and chronology

The similarity in size and technical skill between the engravings and reliefs at the Camel Site, and their geographic overlap, suggest that the reliefs discussed in this article may represent a more sophisticated, 3D expression of the same tradition (Charloux et al. Reference Charloux, Guagnin and Norris2020). A recent chronological assessment of the Camel Site suggests a Neolithic date for the reliefs (Guagnin et al. Reference Guagnin2021), and the engravings described here may therefore be of a similar age. Superimpositions observed amongst some of the newly documented panels provide further evidence of their probable age. One panel at Jebel al Misma depicts a ‘Jubbah-style’ hunter—a style of figure that is generally associated with Neolithic and pre-Neolithic rock art (Figure 6A–B) (Khan Reference Khan2007; Guagnin et al. Reference Guagnin2017). Although the panel is heavily eroded, the Jubbah-style hunter appears better preserved than the camel engraving and is most probably associated with a group of ibex superimposed over the camel's front leg. Further camel engravings in a shelter at al Misma are superimposed over an engraving of an equid (Figure 6D); similar equid representations are known to be associated with the earliest engravings in Jubbah (Guagnin et al. Reference Guagnin2017). Despite remaining chronological uncertainties, the rock art appears to confirm the widespread presence of wild camels and their immense cultural importance for the prehistoric populations of northern Arabia.

Conclusion

Our research suggests that the Nafud Desert region was once the centre of an artistic tradition in which large, naturalistic representations of camels (and, to a lesser degree, other mammals) were engraved and reworked over a long period of time, requiring individual engravers to cross the Nafud Desert repeatedly. The tremendous effort required to curate these images, as well as the technical sophistication and attention to detail applied in their creation, demonstrates the symbolic significance that the wild camel had for these people. Superimpositions visible in some of the panels, and parallels with the Camel Site, place the engravings in the Neolithic period, or even earlier. More extensive surveys and analyses are now required to confirm the age, as well as the environmental and social context, of these engravings.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Heritage Commission of the Saudi Ministry of Culture (HC), in particular Abdullah Al-Zahrani, Nasser Hassan al-Shari and Mohammed Rashid al-Shari. This research is supported by the CNRS, the HC, the Max Planck Society, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the French Embassy in Riyadh, and Freie Universität Berlin. We also thank Christoph Baumer, Florent Egal and Mohammad AlMaarik for bringing engravings from a wider area to our attention.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.