Introduction

In recent years, research into Viking Age (c. ad 790–1050) society has explored its complex social compositions, group formations, and social identities (Svanberg, Reference Svanberg2003; Downham, Reference Downham2009; Raffield et al., Reference Raffield, Greenlow, Price and Collard2016). The reassessments of object-based, chronological frameworks (Skibsted Klæsøe, Reference Skibsted Klæsøe1999) and new dating of trade patterns and maritime ventures (Ashby et al., Reference Ashby, Coutu and Sindbæk2015; Price et al. Reference Price, Peets, Allmäe, Maldre and Oras2016; Baug et al., Reference Baug, Skre, Heldal and Jansen2018) have furthermore shown that the early Viking Age comprises multifaceted and overlapping sets of processes and events that extend back to the early eighth century. One illustrative example of this long overlap is the change in jewellery sets from around ad 700 on the Scandinavian peninsula, including large disc-on-bow brooches, arm-rings, and the introduction of domed, oblong brooches (Callmer, Reference Callmer, Høgestøl, Larsen, Straume and Weber1984: 67).

Here, we explore the social complexities that characterize this period of transition through an in-depth study of the disc-on bow brooches (Figure 1) in Norway and mainland Sweden. Although considered a defining artefact of the Vendel period (c. ad 550–790), there is no up-to-date overview and contextualization of the material. We present a revised typology of the brooches and use this as a starting point to explore how they were used and curated. We argue that the disc-on-bow brooches become increasingly important as mnemonic objects during the Vendel period, and that this is linked to negotiations and conflicts around the past as a political resource in the late Vendel period and early Viking Age. Recent studies have examined the role of the past in the Viking Age, including new perspectives on runic stones and picture stones as foci of remembrance and the re-creation of mythologies and identities (Arwill-Nordbladh, Reference Arwill-Nordbladh, Fransson, Svedin, Bergerbrant and Androshchuk2007; Andrén, Reference Andrén2013) and on interactions with monuments and landscapes (Thäte, Reference Thäte2007; Lund & Arwill-Nordbladh, Reference Lund and Arwill-Nordbladh2016). There has, however, been little attempt to explore this period by combining knowledge gained from typology and detailed contextual studies with theoretical consideration of socially-constituted temporalities and identities (see Fowler, Reference Fowler2017).

Figure 1. Disc-on-bow brooch, Melhus, Trøndelag, Norway (T6574). Length: 24 cm. © NTNU Norwegian University Museum Trondheim, P. Fredriksen/ CC BY-SA 4.0.

In Scandinavia, the disc-on-bow brooches are particularly associated with the cloisonné style. The brooches represent the last and northernmost occurrence of the early medieval use of garnet cloisonné for exclusive items. This technique was widespread in continental Europe in the fifth to seventh centuries and used to decorate unique objects made for the political and social elites (Arrhenius, Reference Arrhenius1985). As garnet decoration gradually went out of use on the European continent from the late sixth to the late eighth centuries, it became increasingly popular in Scandinavia and Anglo-Saxon England to adorn a variety of status objects (Arrhenius, Reference Arrhenius1985; Adams, Reference Adams, Entwistle and Adams2010; Ljungkvist & Frölund, Reference Ljungkvist and Frölund2015; Glørstad & Røstad, Reference Glørstad, Røstad, Vedeler and Røstad2015; Hamerow, Reference Hamerow, Hilgner, Greiff and Quast2017; Fern et al., Reference Fern, Dickinson and Webster2019). While largely going out of production by the late eighth century, the brooches remained in circulation until the tenth century, as antiquities, either complete or in fragments. We argue that the development and long-term use of both complete and fragmented brooches reflects ongoing social negotiations and internal social conflicts from the late Vendel period to the Viking Age, and that women were central to these negotiations. This topic inevitably also concerns the question of how the past was integrated and interpreted in Viking-Age society, particularly how defining and engaging with the past were linked to changing social cohesion and political tension in parts of Scandinavia. This approach underlines the necessity of considering how Scandinavian society in the Viking Age was influenced by its own past, and how this historicity contributed to shape identities and social strategies within various Norse groups.

The Disc-on-Bow Brooches, ad 550–790

The disc-on-bow brooches developed as a distinct fibula type during the Scandinavian Vendel period (c. ad 550–790), with the first examples known from the early sixth century. They evolved from typological forerunners around the North Sea coast, such as relief brooches and fibulae decorated with filigree, garnets, or other semi-precious stones and glass (Salin, Reference Salin1904: 66; Ørsnes, Reference Ørsnes1966: 115; Olsen, Reference Olsen2006). The so-called ‘prototypes’, that is small, not yet standardized brooches, reflect the various regional forerunners (Figure 2). Disc-on-bow brooches are found throughout the Vendel period in all of Scandinavia, the majority in Norway and Sweden. The Swedish island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea has a high concentration of disc-on-bow brooches with a distinctive development, and there production continued into the eleventh century (Thunmark-Nylén, Reference Thunmark-Nylen2006). The Gotlandic corpus is well published and illustrated, and Birger Nerman's studies (Reference Nerman1969, Reference Nerman1975) are still key for this type of brooch. Other studies include Gutorm Gjessing's publication of Norwegian Vendel-period finds (Reference Gjessing1929, Reference Gjessing1934) and Mogen Ørsnes’ (Reference Ørsnes1966) extensive work on the Vendel-period material from Denmark and southern Sweden, as well as regional studies from Norway and Sweden (Stjerna, Reference Stjerna1905; Serning, Reference Serning1966; Vinsrygg, Reference Vinsrygg1979; Gudesen, Reference Gudesen1980; Minda, Reference Minda1989).

Figure 2. Prototype variant, Lunda, Uppland, Sweden (SHM 32300: A1). Length: 6.5 cm.

© Zanette T. Glørstad/ CC BY-SA 4.0.

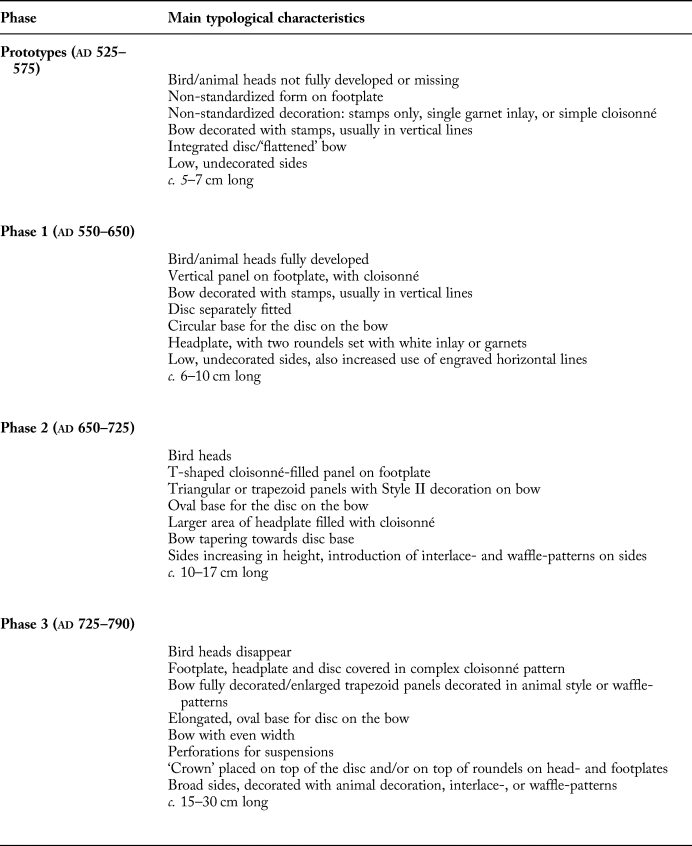

Ørsnes’ work has proved particularly influential, and several later studies build on his typology, which rests mainly on the southern Scandinavian and Gotlandic material (Gudesen, Reference Gudesen1980; Høilund Nielsen, Reference Høilund Nielsen1987; Olsen, Reference Olsen2006). Consequently, some characteristics that appear only on brooches from Norway and Sweden do not fit into Ørsnes’ scheme. Several brooches from Norway and mainland Sweden are, for instance, larger than their southern Scandinavian counterparts and include features absent in that material (Gjessing, Reference Gjessing1934: 138–39). Ørsnes’ typology stresses one specific element, i.e. the presence of one versus three roundels on the footplate, as an overall principle for the subdivisions. This is a traditional distinction between brooches from Gotland and mainland Scandinavia, but it is not a consistently observed difference (Ørsnes, Reference Ørsnes1966: 106). Arguably, this characteristic only plays a minor role as a distinguishing feature; too much emphasis appears to have been placed on this element at the expense of other more conspicuous traits. We therefore present a revised typology of disc-on-bow brooches from Norway and mainland Sweden, comparable to Ørsnes’ subtypes and phases (Table 1). Unlike Ørsnes’ scheme, it does not distinguish between one and three roundels on the footplate. Like Ørsnes, we take into account the brooch's size, the type (or absence) of ‘bird’ heads shown in profile on the footplate, as well as the type of ornamentation and its distribution on the bow and side of the brooch. In addition, the revised scheme emphasizes certain characteristics of the headplates, footplates, and bows not mentioned by Ørsnes. The dating of the brooches follows Ørsnes’ three phases, although we acknowledge that their absolute dates are disputed (Høilund Nielsen, Reference Høilund Nielsen1987). In practice, the brooches are all distinctive with no apparent identical copies; they nevertheless have some common denominators within and across regions.

Table 1. Revised typology with main characteristics of the brooches.

The Dating and Context of Disc-on-Bow Brooches from Norway and Mainland Sweden

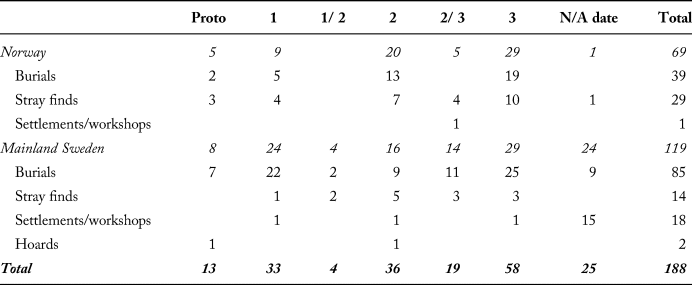

Our review of the Swedish and Norwegian material includes 188 brooches: 119 brooches from the Swedish mainland and sixty-nine from Norway (Table 2) were recorded as either complete exemplars or as fragments (see Supplementary Material for details). The number of finds from each phase increases over time, with most finds dating to the later phases. This could partly be due to the brooches’ increase in size, from c. 6–10 cm long in Phase 1 to up to 25–30 cm long in Phase 3 (e.g. Kåsta in Uppland, SHM 5767, 15878). The later brooches, or large fragments of them, are likely to be more visible in circumstances of accidental findings or non-professional excavations.

Table 2. Number of brooches (or fragments) according to the revised typology. Some fragments are too damaged to be classified; for details, see Supplementary Material.

For both countries, most brooches come from burials: 124 brooches derive from burial contexts, which is a very small proportion of the burials known from Norway and mainland Sweden, given that there are approximately 8000 Viking-Age burials in Norway alone (Stylegar, Reference Stylegar2010: 71) and about 1500 burials of the Vendel and Viking period in southern Sweden (Svanberg, Reference Svanberg2003: 19). Of the thirty-nine burials with disc-on-bow brooches recorded in Norway, eleven were inhumations and thirteen cremations; in the remaining graves, the burial ritual is unknown or insufficiently documented. In Sweden, fifty-nine of the eighty-five brooches from burials are from probable or secure cremation contexts, and only six come from confirmed inhumation burials. Very few burials contain enough human remains to determine biological sex. Nevertheless, studies of southern Scandinavian burials point to a strong correlation between biological sex and traditional, gendered items (Sellevold et al., Reference Sellevold, Lund Hansen and Balslev Hørgensen1984; Svanberg, Reference Svanberg2003: 21–24). Thus, a deceased person buried with brooches, dress pins, bracelets, six or more beads, or textile working implements is considered to be gendered feminine. In total, seventy-five burials could be archaeologically determined as feminine, with no objects designating masculine gender identities. Of the seventeen recorded inhumation burials, only five individuals have been osteologically sexed. Of these, four were assumed to be female, as they were buried with traditionally feminine objects including beads, brooches, and textile working equipment (SHM 29401: g15, SHM 36009:98, RAÄ 162/ A15, VM 27650). One burial, however, contained remains identified osteologically as likely male (UM 43227:79). The deceased was buried with, among other things, a late Vendel-period oval brooch, some forty beads, and a spiral arm-ring. No objects could be associated with a traditional male gender identity. The burial underlines how expressions of gender and its relation to biological sex, or the gendered expression of fluid social roles, may be more complex than previously assumed (see Hedenstierna et al., Reference Hedenstierna-Jonson, Kjellström, Zachrisson, Krzewińska, Sobrado and Price2017).

Many brooches are stray finds or have no context information. Some fragments are found in settlement contexts and seem to have been scrap metal (C52519/14294 from Norway and SHM 5208:32 U 3941 and Rasbo 630:1/no. 158 from Sweden). In Sweden, two brooches come from possible ritual wetland hoards (SHM 1209 and SHM31325, see Lamm, Reference Lamm1986; Magnus, Reference Magnus, Hines, Nielsen and Siegmund1999).

Table 2 presents the corpus. There are no significant differences between the brooches found in Norway and those from mainland Sweden. A group of eight Phase 2 brooches illustrates this: on these, an entire bird's head is shown on the footplate under the roundels with garnet inlays, in contrast to the more common design with only a stylized beak under the roundels, which marks the bird's eyes (Gjessing, Reference Gjessing1934: 138–39, ‘Trøndsk-Jemsk’ group). This variant occurs in central Scandinavia, in both Sweden and Norway, and on the west coast of Norway. Another example is the crucible for the crown of a late Phase 3 brooch from the production site of Store Förvar on Gotland. This crown has few parallels in Gotland itself, the closest being found north of Lake Mälaren in eastern Sweden and in south-western and central Norway (Rogaland and Sør-Trøndelag County) (Gustafsson, Reference Gustafsson, Wallin and Martinsson-Wallin2017). Despite the many variations within the corpus, there are, as demonstrated above, clear examples of connections between the brooches and intra-regional social networks, forming part of a web of production and exchange from the Baltic Sea to central Scandinavia from the end of the eighth century onwards.

Burial rites including cremation of the deceased and of the grave goods significantly influence how objects are preserved, and to which degree they can be identified and contextualized. The large proportion of cremation burials partly explains the highly fragmented, and hence difficult to date, brooches in the Swedish corpus. It is possible to exclude certain phases on the basis of some features, but several fragments can only be attributed to a broad phase. They nevertheless contribute to the overall chronological distribution and development and are therefore included in Table 2 as belonging to either one of two possible phases (1–2 or 2–3).

It is worth noting that the development of agriculture and cultural heritage legislation affect the archaeological record. For instance, metal-detectorists have contributed to several new finds in Norway over the last decade, whereas in Sweden private metal-detecting is largely prohibited. Also, the contents of many burials were acquired through old or non-professional excavations conducted in response to the reorganization of the agricultural landscape, with finds reported as far back as 1835. In most cases, these find contexts are incompletely documented.

Time and Fragmentation

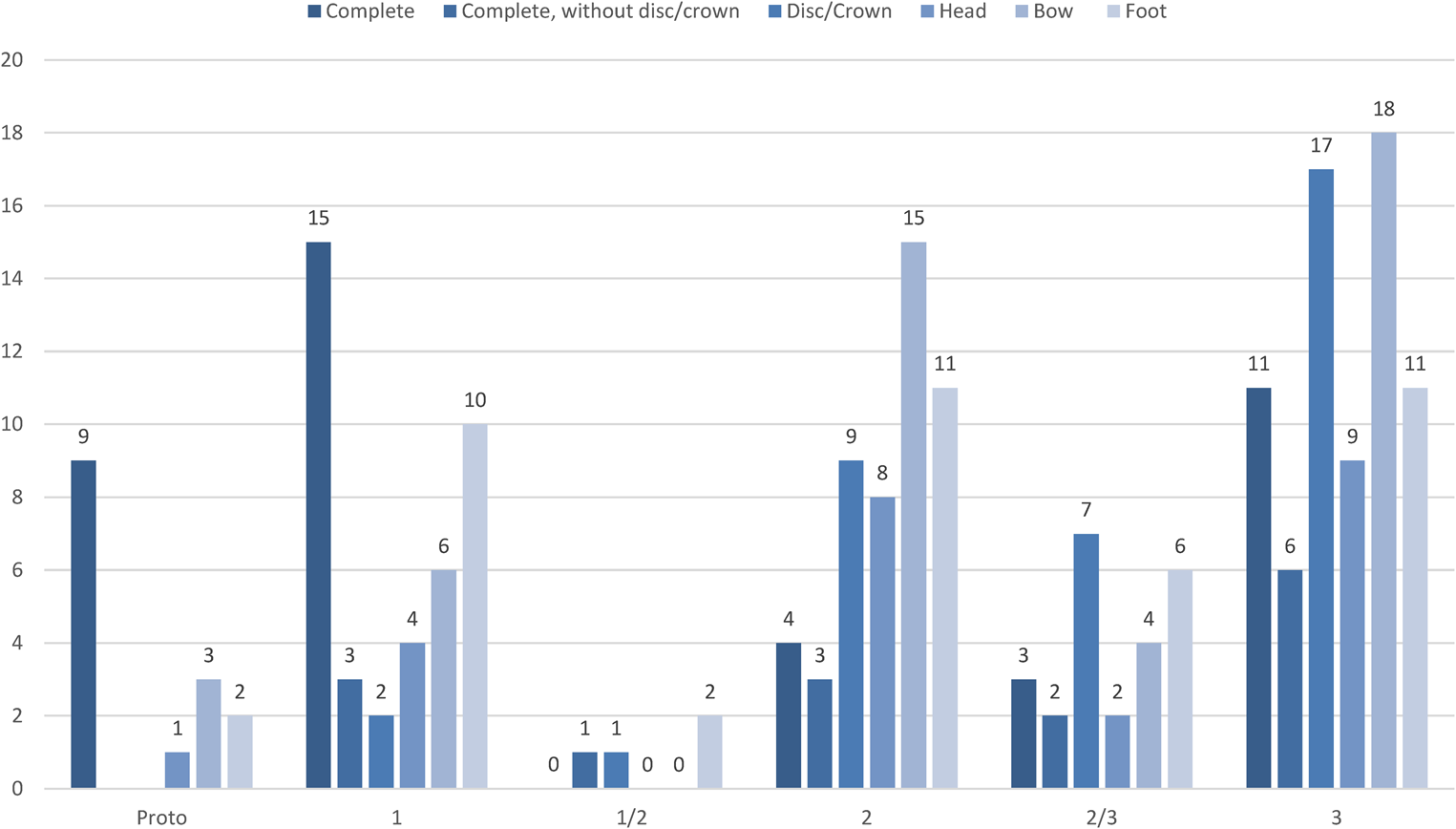

The revised typology and the brooches’ contextual information reveals two main trends that give a broader perspective on their characteristics and use. First, by comparing the datable burials with the stylistic dating of the brooches, it becomes clear that many brooches were quite old at the time of their deposition in burials. Second, what seems to be a cognisant and prolonged use of these brooches is underlined by considerable, deliberate fragmentation and secondary use of brooch fragments (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Complete vs fragmented brooches compared to the brooches’ production phase. Where the fragment consists of two elements, both are recorded. For detailed descriptions, see Supplementary Material.

It is possible to compare the phases of manufacture and depositions of seventy of the brooches, although the quality of excavation and documentation varies. The relative dating of the brooches is based on the revised typology presented above, and the suggested phase of the burials is based on the typological dating of the additional objects in the grave, following established Scandinavian chronologies (Høilund Nielsen, Reference Høilund Nielsen1987; Røstad, Reference Røstad2016). Comparing the relative chronologies for separate types of objects poses challenges, including overlapping chronological schemes and diverging subdivisions of the schemes in question. Nevertheless, in many cases, there appears to be a marked deviation between the estimated period of production of a brooch and its deposition in a burial. This ambiguity seems to emphasize an observation made by the Norwegian archaeologist Guttorm Gjessing on the disc-on-bow brooches: ‘… it will surely prove that for some reason they have been preserved for a long time before deposition in the earth, longer than other types of antiquities’ (Gjessing, Reference Gjessing1934: 139–40, authors’ own translation). Several brooches show much wear and repair; the surface decoration on the bows and edges are worn and parts are reinforced by adding metal sheets. The importance of maintaining the brooches and brooch fragments over long periods seems to start in Phase 2. In fifteen burials, brooches typologically dated to the Vendel-period Phases 1–3 are found in burials with grave goods typologically dated to the late Vendel period or Viking Age, implying that the brooches were deposited in the burial fifty to 100 years, perhaps even longer, after production. Among these, the early Phase 2 brooch from Ylmheim in Sogndal (B12215) shows traces of wear and was repaired before being deposited in a Phase 3 burial. In a burial at Svergvollen in Kvikne (C25880) the seventh/early eighth-century brooch was about 100 years old or more at the time of burial in the early ninth century. In the Norwegian corpus, seven brooches and brooch fragments are documented in female burials with characteristic Viking-Age jewellery (see Supplementary Material). This could in many cases be because a mature woman kept fragments or brooches acquired in youth. Nonetheless, there are also noticeable time intervals. In two cases—the Phase 3 brooches found in a tenth-century burial at Hagbartholmen in Steigen (Ts5281) and in a late tenth-century (possibly close to ad 1000) burial in Fonnås in Rendalen (C8156)—the brooches were 100–150 years old at the time of burial. A similar practice existed, though more difficult to confirm, among Swedish brooches, although thirteen burials could belong to the early ninth century (see Supplementary Material).

The high degree of fragmentation and occasional reworking is a feature common to both Sweden and Norway. Some burials contain several fragments of the same brooch, indicating that it was originally deposited complete but damaged, either during cremation or through decay. In other burials, the fragments display signs of deliberate division and reuse. This phenomenon is recorded in at least fifteen finds, and consists of deliberately separated discs, top crowns, headplates, footplates, and separate bow fragments. Some of the detached parts show traces of worked edges, others are refitted with a pin and catchplate to form a new brooch or are perforated for secondary use. Examples include a bow fragment with worked edges from a female burial at Melø, Norway (C11898; Figure 4), fitted with a secondary pin and catchplate, and a perforated bow fragment from Lien, Norway (C26134a), indicating a secondary use.

Figure 4. Bow fragment with worked edges, Melø, Vestfold, Norway (C11898). a) front; b) back with secondary pin/catchplate. © Museum of Cultural History, Oslo, K. Helgeland/ CC BY-SA 4.0.

The quantity of fragmented brooches increases throughout the period under scrutiny, while the number of complete brooches decreases. The extent of deliberate vs accidental fragmentation is difficult to estimate, although clearly many fragments are the result of the deliberate and targeted breaking up of brooches. In Phases 2 and 3, this seems to target particularly two elements: the bow and the discs and crowns. The increased use of interlace and animal decoration on the bow may have amplified their aesthetic value but also their meaning. The highly affective properties of the intricate design, central in retelling and creating political and cosmological perceptions (Kristoffersen, Reference Kristoffersen1995; Hedeager, Reference Hedeager2005), is likely key to understanding their value and impact as re-used objects. The emphasis put on the separated discs and crowns could indicate that this feature was given extra significance and representative value. One find underpinning this hypothesis is an early Phase 3 disc found in a burial in Södermanland (SHM 34034, grave 16): the disc had a cord looped through its central hole (where the rivet would have originally been), and it was placed on a layer of birch bark and feathers (Foghammar-Summanen, Reference Foghammar-Summanen1987). There are also several examples of otherwise complete brooches where the disc is missing and appears to have been intentionally removed, which could be associated with the potency of the discs. On an otherwise complete Phase 2 brooch from Store Skomo in Trøndelag (T7714) found in a Phase 3 burial, textile fragments covered the bow and the rivet hole originally intended to fasten the disc. This would only be possible if the disc had been removed before burial and the cloth placed over the dead. The most obvious example of an intentionally removed disc is the lavish Phase 3 brooch from Tuna in Badelunda (Vlm 27650), dated to the late eighth century: here the disc was removed, but the crown that is normally on top of the disc was re-fastened directly on the bow (Nylén & Schönbäck, Reference Nylén and Schönbäck1994: 94–99). It has, however, not been possible to prove that discs and brooches from separate localities constituted part of the same object, nor that parts of the same brooch have been deliberately placed in different sections of the grave.

The separate discs and crowns, as well as the otherwise complete brooches with missing discs, reveal how the brooches must have been reworked and manipulated, subjected to negotiations about how their different parts and associated affects were to be distributed among the families and groups to which they belonged. The practice of fragmentation could also be interpreted as an act of pars pro toto (Brück & Fontijn, Reference Brück, Fontijn, Fokkens and Harding2012; Van der Vaart-Verschoof & Schumann, Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof and Schumann2020) in which the separate fragments, with discs and crowns being particularly expressive, carried the ideological and social connotations of the complete brooch, thereby preserving the connection between the previous owners, the deceased, and the brooch as a social, mnemonic object. Fragments then would not only transmit the symbolism of their intact form, but also the enchained connotations of past makers and owners (Chapman, Reference Chapman2000: 39). The traces of deliberate fragmentation and reassembling thus also refer to notions of relations, continuation, bricolage, and identities (Chapman, Reference Chapman2000; Hamilakis & Jones, Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017).

Women as Custodians of the Past: Collective Memories and ‘Cosmological Authentication’

Key studies have underlined cultural or collective memory as essential for mobilizing and defining social communities (e.g. Connerton, Reference Connerton1989; Halbwachs, Reference Halbwachs and Coser1992), and the central role of material culture in re-enacting, manipulating, and negotiating temporal conceptions and communal pasts. Several studies elucidate how material culture moves beyond a conventional timeframe of production, use, and deposition, and that objects, localities, and rituals are repeatedly re-used and re-enacted as mnemonic tools (e.g. Van Dyke & Alcock, Reference Van Dyke and Alcock2003; Williams, Reference Williams2006). These studies emphasize how recollection of the past, either imagined or historical, is a dynamic process including different types of materialities, objects, actions, and embodied experiences, forming intricate fields of temporal and social references (Jones, Reference Jones2007).

The dating, context, ornamentation, and fragmentation of the disc-on-bow brooches points to an increase in such complex referential practice, with a marked change in attitude towards these brooches and their separate parts from around ad 700. During Phase 3, the development of the brooches becomes quite extreme: they reach almost unwearable proportions, the garnets, interlace, and Style III decoration increasingly covers all possible surfaces. This, and the growing number of carefully divided brooches and re-used fragments, suggests that the disc-on-bow brooches became gradually more significant as social and symbolically-charged objects actively integrated within ongoing political and social practice. The cruciform brooches of Anglo-Saxon England, which increase in size through their period of use likely due to their growing symbolic importance (Martin, Reference Martin2015), constitute a valid parallel. Oval brooches also see their size increase during the eighth century, and it has been suggested that the latter phenomenon is linked to the growing availability of metal and increasing resources through emerging urban networks (Sindbæk, Reference Sindbæk, Berge, Jasinski and Sognnes2012). Part of the brooches’ growing significance and prestige may thus be connected to the display of access to the resources needed for their production.

It is also possible that the gradual increase in size facilitated further fragmentation and distribution of the brooches, contributing to enhance their value as authenticating objects and thereby distributing a sense of ownership to mythical narratives. As noted, the prolonged use and conservation of brooches and fragments are widespread phenomena, possibly reflecting how their value as antiques and mnemonic objects grew in importance during the eighth century and the Viking Age. This corresponds to what seems to be a return to conservative styles of decoration during the eighth century, with Phase 3 brooches incorporating ornamental details and features usually associated with older types (Gjessing, Reference Gjessing1934: 139–41; Ørsnes, Reference Ørsnes1966: 111; Thunmark-Nylén, Reference Thunmark-Nylen2006: 51–52, 57). Examples include the brooches from Tømmerås, Norway (T1120), and Ruda, Sweden (SHM 17906): their size and oval-shaped centre at the bow indicate that they were produced in the final phase of the Vendel period. The bow, however, contains conspicuously conservative traits, with a narrow, triangular section and a decorative style largely associated with Phase 2 brooches (Figure 5). The design of the animal figures does nonetheless include traits typical of late Style III, suggesting that the brooches were produced later, as does the dense grid pattern covering the entire bow (Gjessing, Reference Gjessing1934: 140–41). All in all, these changes can be seen as reflecting growing concerns within the social groups in which the brooches and their fragments circulated about the brooches’ role as narrative and time-authenticated objects.

Figure 5. Triangular section on Phase 3 brooch, Tømmerås, Trøndelag, Norway (T1120). © NTNU University Museum Trondheim, P. Fredriksen/ CC BY-SA 4.0.

The gold foil figures from various parts of Scandinavia, largely dating to the seventh–eighth centuries, constitute an additional source for exploring the significance and gendered use of the disc-on-bow brooches. The gold foils show miniscule images, primarily of single or paired humans. They are mainly interpreted as idealized depictions of members of a social elite, or of gods, or mythological characters exhibiting symbols of power. Their meaning is unknown; but their context suggests that they were associated with centres fulfilling political, economic, and cultic functions controlled by the elite (Watt, Reference Watt and Larsson2004; Ratke & Simek, Reference Ratke, Simek, Andrén, Jennbert and Raudvere2006). Despite their minute size, the gold foils show a remarkable level of detail in the depiction of bodies, clothes, and key accessories associated with highly ritualized roles or ritual transformations (Back-Danielsson, Reference Back Danielsson, Hamilakis, Plucenniks and Tarlow2002; Hedeager, Reference Hedeager2015). Several gold foils show women wearing a disc-on-bow brooch placed horizontally, with the head plate pointing toward the woman's right, just under the woman's chin (Figure 6a). A disc-on bow brooch is also clearly depicted and placed in the same manner on a silver amulet from Aska, Sweden, dating to c. ad 800 (Figure 6b) (Arwill-Nordbladh, Reference Arwill-Nordbladh, Fransson, Svedin, Bergerbrant and Androshchuk2007). In these depictions, the disc-on bow brooch emphasizes what appears to be complex symbolic images; it has been suggested that the brooches represent the mythical necklace ‘Brísingamen’ of the goddess Freyja (Arrhenius, Reference Arrhenius1962; Back-Danielsson, Reference Back Danielsson, Hamilakis, Plucenniks and Tarlow2002; Burstrøm, Reference Bertram, Klevnäs and Hedenstierna-Johnson2015).

Figure 6. Depictions of idealized women, with detailed renderings of disc-on-bow brooches included in the women's appearance. a) gold foil from Ekerö/Helgö, Uppland, Sweden (SHM 25075/ 1101); b) silver amulet, Aska, Hagebyhöga, Östergötland, Sweden (SHM 16429/1). © Swedish History Museum, G. Jansson/ CC BY 2.5 SE (a); © Swedish History Museum, C. Åhlin/ CC BY 2.5 SE (b).

It is also possible that in some cases the brooch formed part of a larger visual display. The rows of small circles below the brooch on the Aska amulet could represent a large bead necklace (Arrhenius, Reference Arrhenius1962). This resonates with the grave goods: several burials contain a combination of a disc-on-bow brooch and a large set of beads, the most prominent bead necklace containing over 1200 beads (Ts5281). An examination of the brooches hints at this arrangement being an integrated combination, with the Phase 3 brooches in particular forming part of a larger visual set. At least seven Phase 3 brooches from Norway and mainland Sweden have two small holes perforating two protruding lobes on one side of the bow or the plates, in all cases on the same side (Figure 7). In two instances, the holes held small copper alloy loops to affix the string of beads, and the brooches appear designed to accommodate the bead arrangements. This underlines how the brooches must have mostly been worn horizontally, with the head plate pointing towards the right, as in the gold foil figures and the Aska amulet. This is consistent with the position of brooches in inhumation burials from northern Norway (Glørstad & Røstad, Reference Glørstad, Røstad, Vedeler and Røstad2015: 195–96). The brooches’ perforated bows or plates, together with the large number of beads found in many of these burials, suggest that the brooch and the beads formed a set, and should not be seen as separate categories. This is corroborated by contemporary hoards containing comparable sets of jewellery (Oras et al., Reference Oras, Leimus, Joosu, Kershaw and Williams2019: 163–64; see also Røstad, Reference Røstad, Vedeler, Røstad, Kristoffersen and Glørstad2018 with references).

Figure 7. Extended, perforated lobe on bow, Österrekarne, Södermanland, Sweden (SHM 8716). © Swedish History Museum, C. Hedenstierna- Jonson/ CC BY 2.5 SE.

The frequent depictions of disc-on-bow brooches on gold foil figures emphasize that they were part of a ritual costume or particular attire worn by specific women during celebrations, memorials, or religious or social rituals (Burström, Reference Bertram, Klevnäs and Hedenstierna-Johnson2015). Ritualized or extraordinary costumes, including jewellery, are intrinsically linked with class, social roles, or certain forms of behaviour or postures. Dress, power, and ideology are, thus, mutually integrated elements. Found in what seems to be exclusively female burials, the brooches may have been particularly important as family heirlooms, passed down between women in the same lineage (Lillios, Reference Lillios1999; Gilchrist, Reference Gilchrist, Hahn and Weiss2013). In this perspective, the disc-on-bow brooches may represent objects associated with the perpetuation of stories relating to genealogy and family identities, and hence the control and perception of time (Glørstad & Røstad, Reference Glørstad, Røstad, Vedeler and Røstad2015; Røstad, Reference Røstad, Vedeler, Røstad, Kristoffersen and Glørstad2018). Arwill-Nordbladh (Reference Arwill-Nordbladh, Fransson, Svedin, Bergerbrant and Androshchuk2007) argues for gendered memorial techniques in the Viking Age, with women's association with the past being more closely bound to oral and ritual transmission mediated through material objects. Such objects would be particularly effective if they possessed exclusive identities referring to ancestors, genealogies, and origin myths.

The challenges of managing and transmitting collective memories and narratives of the past may also be reflected in Norse written sources, especially the Eddic poem Hyndlaljod. Hyndlaljod is one of several poems hinting at the complexity of temporal concepts, as well as the significance of controlling and understanding time and temporal relations in Norse society (Clunies Ross, Reference Clunies Ross1994: 234–41). The poem describes how Freyja wakes up the giantess Hyndla, so that she might reveal the ancestors of the protagonist, Ottar, for the latter to claim his inheritance and become king. Hyndla unveils Ottar's lineage, connecting him to the royal families of the Skjoldungs and the Ynglings, both tracing their ancestry back to the gods (Steinsland, Reference Steinsland2005: 154–55, 162, 239–41). Here, Freyja appears as a facilitator revealing memories and genealogies, and the poem illustrates the importance of mythic origins and lineage to gain formal authority. The poem also alludes to knowledge of the past and of collective narratives that had to be managed and maintained by specialists. It implies that this was not only a potent, but also potentially dangerous, type of knowledge. In this perspective, the disc-on bow brooches appear as essential for a form of ‘cosmological authentication’ (Weiner, Reference Weiner1992: 4) combining notions of material agency, historic legitimation, and ritual authority.

Creating a Past Through Antiquities: Insular Loot and Disc-on-Bow Brooches

Following this line of thought, the context and use of the disc-on bow brooches entail aspects of power and hierarchy. Mnemonic objects benefit those families and individuals that have access to and ownership of the inalienable objects in question. As not everyone has equal access to such objects, their possession and display may be perceived as representing a noble good, legitimizing social hierarchies, privileges, and distinction. Access to such heirlooms could, thus, be associated with family memories and personal identities, but also remove signal rank, distinction, and authority.

The possession of heirlooms associated with high social status or genealogy may increase in significance at times when inherited status is threatened by groups or individuals who have acquired higher status through, for example, new political institutions, new forms of economic transactions, or the vagaries of war (Lillios, Reference Lillios1999). This would fit the context of Norse society in the late Vendel period and early Viking Age, from the early eighth into the ninth century. The intensification of the North Sea trade, and the raiding and colonization on the British Isles may have contributed to a more volatile political situation in the Norse homelands, compromising traditional inherited status. This could have resulted in an increased emphasis on the mythical concepts and social distinction represented by exclusive objects. This could explain why the brooches grew to enormous sizes and featured increasingly lavish decoration during the eighth century, and why they were kept in circulation by some families well into the Viking Age. This could, in turn, indicate that similar ideas are detectable in other material categories, as notions and definitions of relevant timeframes and pasts could affect different social groups, with varying reactions and counter-reactions.

The material brought back to Scandinavia from Britain and Ireland (‘Insular’ items) through raiding and trading in the early Viking Age can usefully contribute to our discussion. Regardless of previous use, the majority of the Insular artefacts brought to Scandinavia were incorporated into female dress, or otherwise associated with women (Wamers, Reference Wamers1985; Glørstad, Reference Glørstad2012; Aannestad, Reference Aannestad2018; Heen Pettersen, Reference Heen Pettersen2018, Reference Heen Pettersen2019). Although these artefacts are often discussed, few researchers have considered that they were frequently antiquities themselves. Many were unique objects produced for the aristocracy or clerical authorities in Britain and Ireland in the late seventh and early eighth century and thus were frequently over 100 years old when taken to Norway. They share many similarities in appearance, maintenance, and fragmentation with the Phase 3 brooches: many are old and gilded, with intricate decoration and inlays of precious stones. This suggests that they were not always random loot but targeted to serve primarily as symbolic capital. This would be essential in a world where noble or mythical heritage controlled the path to influence and power. If we view these imports as part of a larger social and material awareness linked to perceptions associated with other types of objects, it is possible that their use in Scandinavia was connected to ongoing social negotiations in times of change. Some imports, including some ornamental mounts from reliquaries reworked as brooches (Figure 8), may even have alluded to the disc on the bow itself. By including in the women's dress Insular items referring to exclusive objects and fragments, upcoming entrepreneurs and families could create an illusion of old lineages and traditions, which was the traditional means of achieving exclusiveness and influence.

Figure 8. Re-used Insular mount, Skedsmo, Akershus, Norway (C15211). Left: front; right: back.

© Museum of Cultural History, Oslo, A. Icagic / CC BY-SA 4.0.

Conclusion

The disc-on-bow brooches from Norway and mainland Sweden form a vast and varied corpus, until recently only partially explored. Re-evaluating the entire group has made it possible to identify typological change over time. The objects’ context and condition has provided a more nuanced perspective on how the production and use of the disc-on-bow brooches consistently go beyond typological phasing: the reintroduction of conservative decorative features, the persistence and repair of the brooches over time, and the curation of brooch fragments speak for an ongoing and attentive interaction with narratives about the past.

Especially in the later Vendel period, the brooches reach enormous dimensions with lavish decoration. In the contemporary representations of idealized women, the brooches are depicted as a detailed and highlighted feature of the costume. A deeper understanding of the significance of this costume element is achieved when assessing the physical traces of the inclusion of brooches and brooch fragments in the funeral costume of select women. They seem to represent an idealized, gender-based role around what appears to be an active mediation, management, and structuring of knowledge of the past in the present. It has been claimed that Viking-age society was extraordinarily fixated on the past, and that the social elite was concerned with creating an intricate referential mosaic of memories and mythologies (Lund & Arwill-Nordbladh, Reference Lund and Arwill-Nordbladh2016; Williams, Reference Williams2016). It is, however, worth noting that there is never a constant or homogeneous understanding of the past or a single way of communicating this within society. Citations of the past in a specific situation through material culture and practice can be interpreted in various, even contradictory, terms and be associated with different narratives; the past can provoke reactions like envy, conflict, rejection, and reinterpretation, as references to the past in essence reflect matters of social interaction.

Multiple and sometimes antagonistic versions of the past will, therefore, exist within the same society, depending on differences over time, space, and social position (Innes, Reference Innes, Hen and Innes2000). This implies that during the late Vendel period and the Viking Age, references to the past were used for different outcomes and to anchor different groups with varying visions of the future. The use of disc-on-bow brooches and their fragments vs jewellery made, for example, from mounts of Insular origin, indicates diverging and contradictory ways of perceiving and curating the past by different social groups. If so, what we see are the contours of conflicts regarding the power to define the past among different social groups, expressed through the active change, manipulation, and appropriation of material culture. Certain groups could, through their experience of and contact with Britain and Ireland, challenge traditional social norms and authority and transcend existing social classes. Regardless of how this process played out, we should consider, when we discuss the variety and heterogeneity of Norse groups, that their identities were anchored both in personal and societal histories as well as social structures. The major change in jewellery traditions and brooches during the eight century reflects innovations in production, style, and costume, but these changes must be understood as socially conditioned, reflecting social and political transformations.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2020.23.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their thorough and constructive comments and suggestions. We would also like to express our deep gratitude to John Ljungkvist, Uppsala University, and to Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, Swedish History Museum in Stockholm and Uppsala University, for information on recent finds.