1. Introduction

An increasing number of children are growing up bilingually. Assuming that monolingual and bilingual children are equally affected by developmental language impairment, the number of bilingual children with language impairment is likely to increase as well. The combination of bilingualism and developmental language impairment in the same individual raises a number of issues for both research and clinical practice. From the perspective of bilingualism research, for example, we may ask whether and if so how a bilingual child's language development is affected by language impairment. Conversely, from the perspective of research on language impairment, we may ask whether and if so how growing up with more than one language influences a child's language impairment. Developmental language impairment in bilingual children also brings up practical concerns for diagnosis and intervention. In Germany, for example, children whose first language is not the dominant language are increasingly represented in elementary school classrooms, and consequently, in the caseloads of Speech-Language Pathologists. Given the heterogeneity of these children's language background, an important question for clinical practice is whether it is possible to identify a bilingual child as language impaired from assessing one of her languages, e.g., in the case of bilingual German-speaking children with Turkish, Arabic, Farsi, Russian, or Kurdish as L1, from their German.

The current study focuses on children with Specific Language Impairment (SLI)Footnote 1, a delay and/or disorder of the normal acquisition of language in the absence of neurological trauma, cognitive impairment, psycho-emotional disturbance, or motor-articulatory disorders (Leonard, Reference Leonard1998; Levy & Kavé, Reference Levy and Kavé1999). Linguistic research on individuals with SLI aims at providing detailed characterisations of their strengths and weaknesses in different domains of language and across different languages, and of how their language differs from that of typically-developing children. This research has identified syntax and morphology as areas of difficulty for many children with SLI, and within these domains specific linguistic markers of SLI. A well-known account considers impaired tense marking as a linguistic marker of SLI in English (Rice & Wexler, Reference Rice and Wexler1996; Rice, Reference Rice, Levy and Schaeffer2003). For German, subject-verb-agreement marking (e.g., Clahsen, Reference Clahsen1989) and the formation of complex sentences involving the CP-domain (Hamann, Penner & Lindner, Reference Hamann, Penner and Lindner1998; Platzack, Reference Platzack2001; Ibrahim & Hamann, Reference Ibrahim, Hamann, LaMendola and Scott2017), the highest syntactic level of clause structure, have been identified as linguistic domains causing particular difficulties for children with SLI. These markers (if correct and valid) should apply to children with SLI irrespective of whether they are growing up with just one or with more than one language. Assuming that these linguistic markers are due to a specific impairment of the child's grammar (Clahsen, Reference Clahsen1989; Clahsen, Bartke & Göllner, Reference Clahsen, Bartke and Göllner1997; Hamann et al., Reference Hamann, Penner and Lindner1998; Platzack, Reference Platzack2001; Rice & Wexler, Reference Rice and Wexler1996, Rice, Reference Rice, Levy and Schaeffer2003), differences with respect to these linguistic markers should be found between bilingual children with and without SLI, but not between monolingual children with SLI and bilingual children with SLI.

Alternatively, difficulties with syntax and morphology in SLI have been attributed to more general cognitive/perceptual deficits leading to reduced intake of linguistic input in children with SLI (e.g., Ellis Weismer, Evans & Hesketh, Reference Ellis Weismer, Evans and and Hesketh1999; Archibald & Gathercole, Reference Archibald and Gathercole2006; Leonard, Ellis Weismer, Miller, Francis, Tomblin & Kail, Reference Leonard, Ellis Weismer, Miller, Francis, Tomblin and Kail2007a; Ullman & Pierpont, Reference Ullman and Pierpont2005). Leonard et al. (Reference Leonard, Ellis Weismer, Miller, Francis, Tomblin and Kail2007a: 411) noted, for example, that for children with limited cognitive/perceptual capacities, comprehension of linguistic input is only partial and linguistic representations are built up more slowly. Given that bilingual children receive less input in each of their languages than corresponding monolingual children, these accounts lead us to expect that bilingual children with SLI should be disadvantaged both relative to typically-developing bilingual children (due to SLI) and compared to monolingual children with SLI (due to reduced input); see, for example, Orgassa and Weerman (Reference Orgassa and Weerman2008).

In the present study, we investigate whether linguistic markers of SLI in German that have been proposed for monolingual children also hold for bilingual children with SLI. The data we examined come from bilingual (Turkish–German) children who grew up in immigrant communities in Germany, learnt Turkish from birth and began to learn German at the age of about three to four years. The study focuses on phenomena that involve the so-called CP (Complementizer Phrase) in German, to test the supposed impairment of complex syntax in SLI German. In addition, we re-examined these children's subject-verb-agreement marking previously studied by Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen (Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012) - using the same statistical methods as for the CP-related phenomena.

2. The CP-domain with special reference to German

The CP-domain has been singled out as a domain of the clause that is supposed to cause problems in different types of populations, viz. typically-developing children learning their native language, children with SLI, adult second language learners, and patients with Broca's aphasia (Platzack, Reference Platzack2001). It is argued that these speakers successfully control the syntax of lower structural levels in a target-like way, but display non-target-like performance for the highest level of clause structure, the CP-domain. Platzack's evidence comes from Swedish with additional observations on German. Platzack noted difficulties in the above-mentioned populations with verb second, complementizers, and wh-questions (all of which involve the CP-domain), whereas other phenomena that are represented at lower levels of clause structure, e.g., pre/postposition, the order between main verb and object, between object and adverbials, etc. are supposedly unaffected.

In standard (generative) analyses of German clause structure, the CP level hosts lexical complementizers and finite verbs, as well as wh-expressions and other (topicalized) constituents. Verb finiteness is encoded in German through tense, mood and subject-verb agreement morphemes, typically suffixes and, occasionally, stem changes. Finite verb placement in German involves the CP-domain. In main clauses and in wh-questions, the finite verb raises from the VP to the functional head C and normally appears in second position (‘V2’) preceded by another constituent, e.g., a subject, an object, or a PP (cf. 1a, 1b). In subordinate clauses, the C-position is typically filled with a lexical complementizer. In such cases, the finite verb cannot move to C and appears instead in clause-final position (‘V-final’; 1c). Non-finite verb forms such as participles, infinitives or verb particles remain in their base position in the VP in both main clauses and subordinate clauses (1d, 1e).

(1)

a. Dilan spielt mit Puppen ‘Dilan plays with dolls’

b. Heute spielt Dilan mit Puppen ‘Today Dilan plays with dolls’

c. Ich sehe, dass Dilan mit Puppen spielt ‘I see that Dilan with dolls plays’ (I see that Dilan plays with dolls)

d. Dilan möchte mit Puppen spielen ‘Dilan wants with dolls play’ (Dilan wants to play with dolls)

e. Dilan hat mit Puppen gespielt ‘Dilan has with dolls played’ (Dilan has played with dolls)

The CP-domain is also involved in the distribution of null and overt subjects in German. Non-embedded so-called root clauses with the finite verb in the C-position allow null subjects in the Spec-CP position only, a case of topic-drop (2a). If the topic position is filled, subject drop is not possible, unlike in so-called pro-drop languages such as Italian and Spanish; see (2b). In subordinate clauses and wh-questions, empty referential subjects are always ungrammatical; see the contrast in (2d) and (2e). An account of this contrast has been proposed by Rizzi (Reference Rizzi, Hoekstra and Schwartz1994). He suggested that topic-drop sentences such as (2a) involve a null constant in an argument position which is not c-commanded, so that the null constant can be freely interpreted within the discourse context; see (2c). This option is not available for subordinate clauses and wh-questions, because in these cases the highest Spec-position is not available for a potential topic:

(2)

a. Habe heute meine Oma besucht ‘have today my grandma visited‘ ((I) visited my grandma today)

b. *Heute habe meine Oma besucht

c. [nci [hab [ti [heute meine Oma besucht]]]]

d. *dass heute meine Oma besucht habe ‘that today my grandma visited have’

e. *Wann hab Oma besucht? ’when have my grandma visited’

3. The CP-domain in bilingual German child language

Extending Platzack's original (Reference Platzack2001) proposal, several researchers have argued that difficulties with CP-related phenomena are also found in bilingual language development. Some researchers have argued that the CP-domain is particularly likely to be subject to cross-linguistic interference in bilinguals (Müller and Hulk, Reference Müller and Hulk2001; but see Bonnesen, Reference Bonnesen, Guijarro-Fuentes, Larrañaga and Clibbens2008 for evidence against this latter view).

Most previous research on CP-related phenomena in bilingual German child language is available on finite-verb movement to the head position of CP (aka ‘V2 placement’). In monolingual German-speaking children, the development of V2 has been shown to be closely linked to the acquisition of finiteness markers, specifically the development of a regular subject-verb-agreement paradigm; see Clahsen and Penke (Reference Clahsen, Penke and Meisel1992) and much subsequent work. In bilingual children, at least those with an age-of-acquisition (AoA) of German of less than 3–4 years, development proceeds in a similar way to monolingual children, according to most (but not all) studies. Typically-developing bilingual children consistently produce main clauses with V2 order once subject-verb agreement has been acquired, usually after 6 to 18 months of exposure (Chilla, Reference Chilla2008; Prévost, Reference Prévost2003; Rothweiler, Reference Rothweiler and Lleó2006).

The V2 position is predominantly filled by finite verb forms even before main clauses are consistently produced with V2 order. Tracy and Thoma (Reference Tracy, Thoma, Jordens and Dimroth2009), for example, reported data from a longitudinal study with Russian–German and Arabic–German children (AoA: 2–4 years) showing that the V2 position is typically occupied by finite verb forms, although one child initially produced non-finite verb forms in V2.

Wojtecka, Schwarze, Grimm and Schulz (Reference Wojtecka, Schwarze, Grimm, Schulz, Amaro, Judy and y Cabo2013) studying 25 typically-developing bilingual children (various L1s, AoA: 3 years) found that at age 3;9, after 5–19 months of exposure, 76% of all verb forms in V2 were correctly marked for subject-verb agreement. Errors in V2 were restricted to the use of bare forms (14%), e.g., spiel ‘play’. Note that bare forms are ambiguous with respect to finiteness; they could be non-finite stems or finite (1st sg or imperative) forms. True non-finite forms in V2 were extremely rare (7%). By contrast, verb forms in clause-final position were typically -n forms (83%), most likely infinitive forms, in addition to bare forms (11%). At age 4;8 almost all verb forms in V2 were correctly marked for subject-verb agreement and almost all of the verb forms in clause-final position occurred with the ending -n. The authors conclude that early bilingual children differentiate between finite and non-finite verb positions by placing finite (correctly inflected) verb forms in the V2 position and nonfinite verb forms in non-finite position. With regard to bare stems, Wojtecka et al. (Reference Wojtecka, Schwarze, Grimm, Schulz, Amaro, Judy and y Cabo2013) argue that such verb forms are likely to be finite, as they appeared more often in the V2 than in clause-final position (see also Prévost, Reference Prévost2003; Schulz & Schwarze, Reference Schulz and Schwarze2017).

Sopata (Reference Sopata, Rinke and Kupisch2011, Reference Sopata, Stavrakaki, Lalioti and Konstantinopoulou2013) investigated verb placement and verb inflection in production data of four Polish–German children. While these data confirmed the developmental link between the acquisition of subject-verb agreement and V2 placement, three of the four children occasionally produced incorrect (potentially non-finite) –n forms in the V2 position as well as finite verbs in a post-subject V3 position, a word order permitted in Polish but not in German. Sopata (Reference Sopata, Rinke and Kupisch2011, Reference Sopata, Stavrakaki, Lalioti and Konstantinopoulou2013) attributed these errors to the relatively late AoA of German for these three children (≥ 3;8), as the fourth child in her sample had an AoA of 2;6 for German and rarely produced these errors.

4. The CP-domain in bilingual German-speaking children with SLI

The CP has been claimed to be a ‘vulnerable domain’ in the grammars of children with SLI (Hamann et al., Reference Hamann, Penner and Lindner1998; Platzack Reference Platzack2001). Instead, children with SLI are supposed to resort to a ‘minimal default grammar’ that projects underspecified CPs which do not comprise the full feature set of the target grammar. Such an underspecified CP might lead to difficulties with structurally complex sentences and to errors with respect to CP-related phenomena such as verb-raising to COMP.

Other researchers have argued against the CP-domain as the core of the grammatical difficulties of German-speaking children with SLI. Rothweiler et al. (Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012; Rothweiler, Schönenberger & Sterner, Reference Rothweiler, Schönenberger and Sterner2017) showed that subject-verb agreement is selectively impaired in both monolingual and bilingual German–Turkish children with SLI, even in children who produce well-formed embedded clauses and wh-questions. Consequently these authors proposed subject-verb agreement rather than the CP-domain as a linguistic marker for SLI in bilingual German-speaking children.

Potential links between verb placement and subject-verb agreement in German-speaking bilingual children with SLI have been investigated by Schulz and Schwarze (Reference Schulz and Schwarze2017) in a study of 11 sequential bilingual children with SLI (AoA: 2;9-3;9, 7–75 months of exposure) compared to 22 younger bilingual typically-developing children (AoA: 2;0-3;4, 5–19 months of exposure). The bilingual children had different L1s, most frequently Arabic, Russian, or Turkish. They found that verb forms in V2 were mostly correctly marked for subject-verb agreement. Agreement errors of verb forms appearing in the V2 position were (potentially finite) bare forms such as spiel ‘play’ or mach ‘do’. Verb forms in clause-final position mostly occurred with the (potential infinitive) ending –n. Unlike the typically-developing group, children with SLI produced some bare forms (8.1%) and verb forms that were correctly marked for subject-verb agreement (13.5%) in clause-final position. The authors conclude from these findings that bilingual children with SLI, like typically developing L2 children, correctly place finite verb forms in finite position and non-finite verb forms in non-finite position, indicating that there is no deficit in the underlying representation of the CP (see also Schwarze, Wojtecka, Grimm & Schulz, Reference Schwarze, Wojtecka, Grimm, Schulz, Hamann and Ruigendijk2015).

5. The present study

The current study aims at contributing to a better understanding of language impairment in bilingual children. To this end, we examined a group of Turkish (L1)–German (early sequential bilingual) children with SLI in comparison to two control groups (bilingual children without SLI, monolingual German-speaking children with SLI) with respect to phenomena related to the CP-domain in German, viz. V2 placement and subject omissions in different clauses types. In addition, we reanalysed earlier presented data on subject-verb agreement from these children (Rothweiler et al., Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012), using the same mixed-effects logistic regression models as for the CP-related phenomena.

With these data sets and analyses, we will assess a number of controversial questions on SLI and bilingualism. If the CP-domain is particularly ‘vulnerable’ in SLI (Hamann et al., Reference Hamann, Penner and Lindner1998, Platzack, Reference Platzack2001), we expect that bilingual children with SLI show an impairment for phenomena that involve the CP-domain relative to typically-developing bilingual children. If, on the other hand, SLI specifically affects grammatical agreement (Clahsen, Reference Clahsen1989), we expect that bilingual (and monolingual) children with SLI have persistent difficulty with subject-verb agreement, even those children with a fully developed CP. Delays and difficulties with language in children with SLI may (also) be due to domain-general deficits causing reduced intake of linguistic input in these children (e.g., Leonard et al., Reference Leonard, Ellis Weismer, Miller, Francis, Tomblin and Kail2007a). Consequently - assuming that both CP-related phenomena and subject-verb agreement are similarly affected by these domain-general deficits - we would expect the group of bilingual children with SLI tested to perform worse on both these phenomena than typically-developing bilingual children.

6. Method

6.1. Participants

We examined spontaneous speech data of German from 18 children, six typically developing Turkish-German bilingual children (‘TD-L2’), six Turkish-German bilingual children with SLI (‘SLI-L2’), and six monolingual German-speaking children with SLI (‘SLI-L1’). The same data set was previously examined with respect to participle formation and subject-verb agreement (Clahsen, Rothweiler, Sterner & Chilla, Reference Clahsen, Rothweiler, Sterner and Chilla2014; Rothweiler et al., Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012). The data of the bilingual children are part of the Hamburg corpus (Rothweiler, Reference Rothweiler and Lleó2006), which consists of longitudinal spontaneous speech data of 24 German-Turkish bilingual children (12 children with SLI and 12 typically-developing children). The data of the monolingual children are part of the Düsseldorf corpus (Clahsen et al., Reference Clahsen, Bartke and Göllner1997; Clahsen, Rothweiler, Woest & Marcus, Reference Clahsen, Rothweiler, Woest and Marcus1992), which consists of longitudinal spontaneous speech data of 19 children with SLI. As the current study targets CP-related phenomena, we ensured that the children included produce complex sentence structures, that is, wh-questions and/or subordinate clauses. Therefore, our sample is not meant to be representative of the population of monolingual or bilingual German-speaking children with SLI.

All participants came from families with a low or middle socio-economical status. For the bilingual children, we carried out interviews with parents and elementary school teachers to obtain information on the children's skills in Turkish and their exposure to both Turkish and German. All bilingual children were exposed to Turkish from birth and initially grew up almost exclusively with Turkish. Exposure to German began when they entered a day care centre, in which the lingua franca amongst the children was German and in which staff spoke only German. All children spent at least 20 hours/week in a day care centre. The SLI-L2 children were assessed as being language-impaired in both languages by qualified speech-and-language therapists on the basis of interviews with parents and teachers. For four children (Arda, at age 4;1, Devran, at age 5;5, Erbek, at age 4;0 and Ferdi, at age 6;5), samples of spontaneous speech of Turkish were recorded, and a standardized Test for Turkish (T-SALT, Acarlar, Miller & Johnston, Reference Acarlar, Miller and Johnston2006) was performed. However, since tests with norms for monolingual children are not really appropriate to assess bilingual children (Thordardottir, Reference Thordardottir, Armon-Lotem, de Jong and Meir2015), here we only report the results from the analysis of the Turkish speech samples (Chilla & Babur, Reference Chilla, Babur, Topbas and Yavas2010). These analyses revealed that these four children perform worse than their typically-developing bilingual peers on a range of measures. In contrast to the TD-L2 children the bilingual children with SLI produced, for example, omission and commission errors in verbal morphology as well as with respect to case markings in their Turkish; see Rothweiler, Babur, and Chilla (Reference Rothweiler, Babur and Chilla2010) for further details.

All SLI-L2 children reached normal IQ scores in a non-verbal IQ test (CMM 1-3, Schuck, Eggert & Raatz, Reference Schuck, Eggert and Raatz1999) or were assessed as being cognitively unimpaired by speech and language therapists. None of these children was reported as suffering from hearing loss or from obvious neurological dysfunction or motor deficits. The SLI-L1 children received individual language therapy and/or attended special language therapy classes and were diagnosed as having SLI by speech therapists. According to the clinicians' reports, their non-verbal cognitive abilities were within the normal range for their chronological age, and there were no reported hearing loss, obvious neurological dysfunction or motor deficits; see Bartke (Reference Bartke1998), Clahsen et al. (Reference Clahsen, Rothweiler, Sterner and Chilla2014), and Rothweiler et al. (Reference Rothweiler, Schönenberger and Sterner2017) for more information.

Table 1 provides an overview of the three child groups’ language profiles (for individual data, see Appendix A1). The three groups were matched in terms of MLU (Mean Length of Utterance), which is taken as a general measure of the level of language development (Rice, Redmond & Hoffman, Reference Rice, Redmond and Hoffman2006). The two L2 groups were also very similar with respect to their mean AoA of German. Note, however, that to match the two groups of bilingual children with respect to ‘general level of linguistic development’, the SLI-L2 children were on average approximately eight months older than the TD-L2 children and had a longer mean time of exposure to German (ME). Note also that the SLI-L1 group was on average approximately one year older than the SLI-L2 group.

Table 1. Language profiles of the three groups

Note. AoA: age of onset of acquisition of German (in years); Exposure: mean exposure to German (in years); MLUw: Mean Length of Utterance (in words).

The six monolingual children with SLI did indeed produce subordinate clauses and/or wh-questions from the first recording onwards. For most of the children in the two L2 groups, earlier recordings are available in which these children did not yet produce wh-questions and subordinate clause. Although the TD-L2 and the SLI-L2 groups are similar with respect to age of onset, the SLI-L2 children started to produce complex sentences only after minimally 15 months of exposure to German, with most children taking a further 12 months before producing the first complex sentences. The TD-L2 children on the contrary did so after about 8 to 15 months of exposure to German. In the data sets included in the current study, omissions of overt wh-words and complementizers were overall not very common. In wh-questions, the frequencies of omissions of wh-words were 3.3% for the SLI-L2 group, 7.9% for the SLI-L1 group, and 4.7% for the TD-L2 group. Of the embedded clauses that required overt complementizers, 4.8% were omitted in the SLI-L2 group, 10.6% in the SLI-L1 group, and 5.6% in the TD-L2 group.

6.2 Materials

We analysed spoken production data from 76 recordings of about 45 minutes each, which involved free play sessions (see Table 1 for the number of recordings per group). The bilingual children were recorded in the day care centres. The monolingual children with SLI were recorded in the institutions where the children were being treated.

6.3 Data scoring and analysis

We adopted procedures for data scoring and analysis that are commonly used for spontaneous or elicited speech data in child language research (e.g., Clahsen, Kursawe & Penke, Reference Clahsen, Kursawe, Penke, Koster and Wijnen1996; Sopata, Reference Sopata, Rinke and Kupisch2011; Unsworth, Reference Unsworth2005; Schulz and Schwarze, Reference Schulz and Schwarze2017). The following utterances were excluded: self-corrections, incomplete aborted utterances, single word utterances, utterances without a verb form, and unanalysable utterances. In addition, the utterances Was is(t) das? (‘What's that?') and Guck ma(l)! (‘Look here!') which are likely to be unanalysed chunks were not considered. A total of 11,100 utterances were included; see Table 1 for a breakdown by participant group.

Verb placement

We examined whether the COMP position is filled with a finite verb form, as required in German main clauses; this is labelled as the ‘V2’ position. Only wh-questions, yes-no-questions (V1-questions) and main clauses were included, since these sentence types clearly distinguish verb-raising to COMP (‘V2’) from the (phrase-final) position for non-finite verbs within the VP (e.g., Nach Wien fahren wir. ‘To Vienna go we’ vs. *Nach Wien wir fahren. ‘To Vienna we go’). In embedded clauses, on the other hand, the correct position of a single verb is (on the surface) indistinguishable from the VP-internal position for non-finite verbs (ob wir wohl nach Wien fahren…’ whether we to Vienna go’); such ambiguous cases were not included in the analysis. Likewise, sentences displaying the pattern (X)V were also excluded, because in such cases it is again not possible to decide whether the verb is in V2 or has remained within the VP.

Firstly, we coded the data as to whether a given verbal element appeared in the V2 position or elsewhere. We assume that a verb form fills the COMP position when it appears on the surface in the first or second position of the clause and is followed by another element. Verb forms in other surface positions, e.g., in the third, fourth or final position, were coded as ‘placed elsewhere’. Secondly, all verb forms appearing in the V2 position or elsewhere were examined with respect to their morpho-syntactic properties, specifically whether they are finite or non-finite in terms of their inflectional form (‘form finiteness’). The following coding rules were applied to the data. As ‘finite’ we coded the verb forms in (3) and as ‘non-finite’ those in (4):

(3)

a. Inflected forms of sein (be) and verb forms with marked stems:

er ist alt ‘he is old’ (infinitive: sein ‘to be’); er isst Kraut ‘he eats kraut’ (infinitive: essen ‘to eat’)

b. Preterit forms:

es regne-te gestern ‘it rained yesterday’ (infinitive: regnen ‘to rain’); er koch-te Kartoffeln ‘he cooked potatoes’ (infinitive: kochen ‘to cook’)

c. Forms with unmarked stems suffixed with -t or –st:

er renn-t schnell ‘he runs fast’; *er renn-st schnell ‘he runs fast’

d. Forms with unmarked stems correctly inflected with -e or -n and an overt subject:

ich renn-e schnell ‘I run fast’; sie renn-en schnell ‘they run fast’

(4)

a. Forms with unmarked stems incorrectly suffixed with -e or -n and an overt subject:

*du renn-en schnell ‘you run fast’, *du renn-e schnell ‘you run fast’ (correct: du renn-st schnell)

b. Infinitive forms in verb clusters and the form sein ‘to be’:

möchte schnell rennen ‘want run fast’, das könnte sein ‘It could be’

c. Verb particles (if separated from finite verb):

ich blase den Ballon auf ‘I inflate the balloon’

Note that while verb forms with the suffixes -t or –st (as well as those in (3a) and (3b)) are unambiguously finite, -e and –n forms may be finite or non-finite; -n forms may be 1st/3rd pl forms or infinitives, and –e forms may be 1st sg or imperative forms vs. (phonologically reduced) infinitive forms. To account for these ambiguities, we did not include verb forms with unmarked stems and an -e or -n affix in sentences without an overt subject. If, however, these verb forms occurred in a verb cluster paired with a finite verb form, -e or -n forms were coded as non-finite (e.g., kann heute kommen ‘can today come’). Furthermore, correctly agreeing -e or -n forms in sentences with overt subjects were coded as ‘finite’ (3d), and non-agreeing -e or -n forms in sentences with overt subjects were treated as ‘non-finite’ (4a); see Clahsen & Penke (Reference Clahsen, Penke and Meisel1992) and Rothweiler et al. (Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012) for further justification. Special attention was given to bare unmarked stems (Ich/du/er kauf ‘I/you/he buy’) which have been argued to be finite by some (Schulz & Schwarze, Reference Schulz and Schwarze2017; Prévost, Reference Prévost2003) and finite or non-finite by others (Rothweiler et al., Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012, Reference Rothweiler, Schönenberger and Sterner2017). We analysed verb placement for these forms separately.

Overt vs. null subjects

In German, subjects can be dropped from the structurally highest argument position in a sentence; see (2a). This option is not available if the Spec-CP position is filled with another constituent, e.g., an object phrase. Compare, for example, a case of topic-drop (viz., Besuche heute meinen Opa ‘(I) visit today my grandpa’) with a case of incorrect subject omission (*Meinen Opa besuche heute ‘My grandpaAcc visit today’). Furthermore, subjects cannot be dropped within embedded clauses and in wh-questions. Our analysis distinguishes between these two kinds of subject omissions. To determine cases of topic drop, main clauses with a finite verb in V2 and an unfilled Spec-CP position were examined, as in these cases null subjects are licit. In addition, we included wh-questions and embedded sentences with an unfilled CP (i.e., questions and subordinate clauses without an overt wh-word or complementizer). To determine cases of incorrect subject omissions, we examined main clauses with a finite verb in V2 plus a filled Spec-CP position, as well as yes-no questions with a finite verb in V1, wh-questions with an overt wh-word and subordinate clauses with an overt complementizer. In all these circumstances, subject omissions are ungrammatical in GermanFootnote 2.

Subject-verb agreement

German subject-verb agreement (henceforth ‘SVA’) inflection encodes PERSON (1st, 2nd, and 3rd) and NUMBER (SG and PL). Regular affixes are -e, -s(t), -t, and –n. Here, we reconsidered the data from Rothweiler et al. (Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012) and Rothweiler et al. (Reference Rothweiler, Schönenberger and Sterner2017), which included the same participants and the same recordings as the current study. Since non-parametric methods were employed in these earlier studies, we reanalysed these data to make sure that the results are replicable using the same statistical methods that were applied in the current study for CP-related phenomena. Sentences without an overt subject were excluded. Produced forms were coded as correct or incorrect depending on whether they correctly encoded the person and number features of the subject.

Statistical analysis

All analyses to be reported here employed mixed-effects logistic regression conducted on count data, i.e., on the summed frequencies for each level of each factor per child. For example, in the case of the verb placement analysis below, the number of utterances was separately calculated for each child in each of the four ‘cells’ (V2 placement vs. elsewhere crossed with finite vs. non-finite forms).

There are several reasons for why this method is more appropriate than the familiar method of calculating proportions. Firstly, proportions are inherently bounded between 0 and 1 and their error variance is not independent from the mean (Barr, Reference Barr2008). Even when such statistical violations are handled by transforming proportions or by employing non-parametric methods (as was done in Rothweiler et al., Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012 and Rothweiler et al., Reference Rothweiler, Schönenberger and Sterner2017), there are still biases in the associated p-values, which may give rise to spurious significances or null results (Jaeger, Reference Jaeger2008). Secondly, the use of logistic regression allows taking into account the actual amount of data that was generated (i.e., the number of utterances produced by each child), whereas an analysis on proportions completely eliminates this information. For example, an analysis on proportions treats 90% of 10 sentences in the same way as 90% of 100 sentences, when in fact we have much narrower confidence intervals around the latter estimate.

Regarding the model's random effects structure, we included ‘random slopes’ (which capture variation in the magnitudes of fixed effects across participants) only if they resulted in models with greater goodness of fit, as assessed by likelihood ratio tests. This procedure allows maximising statistical power while keeping Type I errors under control (see Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen & Bates, Reference Matuschek, Kliegl, Vasishth, Baayen and Bates2017).

7. Results

The following analyses compare the bilingual SLI group (SLI-L2) with bilingual typically-developing children (TD-L2) on the one hand, and with monolingual children with SLI (SLI-L1) on the other, with respect to (i) finite vs. non-finite verb placement, (ii) overt vs. null subjects, and (iii) correct vs. incorrect subject-verb agreement.

7.1 Verb placement

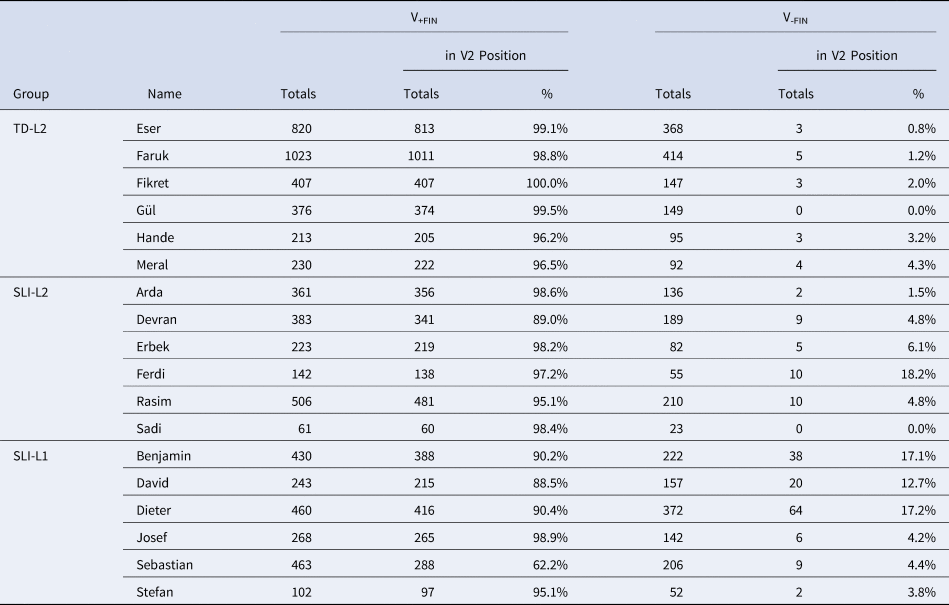

Table 2 gives an overview of the proportions of finite (V+FIN) and of non-finite verbs (V−FIN) that appeared in the V2 position (for individual participant data, see Table A2 in the Appendix). Here and in all cases below, mean percentages were calculated across participants within each group.

Table 2. Frequencies and mean percentages (SDs in parenthesis) of finite and non-finite verb forms in V2 for the three participant groups

As can be seen in Table 2, proportions of finite verb forms in their expected V2 position were high for all three groups. In contrast, non-finite verb forms were rarely produced in the V2 position. All individual subjects performed within 2 SD of their group's mean. The mixed-effects model included Child as a random effect, as well as the fixed factors Form Finiteness (finite vs. non-finite) and Group (TD-L2, SLI-L2, SLI-L1) and their interaction. The model made use of treatment contrasts (in which levels of a factor are compared against a baseline level), which allowed obtaining the main comparison of interest, namely, SLI-L2 vs. TD-L2 (to examine the effect of SLI within bilingual children). Additionally, we also compared the SLI-L2 versus SLI-L1 groups (to examine the effect of bilingualism within children with SLI). Finally, in order to capture the variation in the effect of finiteness across children, Form Finiteness was also included as a random by-participant slope (as this was found to significantly improve model fit; χ2(2) = 63.66, p < .001).

Significant interactions between Form Finiteness and Group were obtained, both for the comparison of SLI-L2 and TD-L2 children (b = −2.32, z = −2.62, p = .009), as well as for the comparison between SLI-L2 and SLI-L1 children (b = 1.77, z = 2.10, p = .035). All groups showed highly significant differences between proportions of finite and non-finite forms placed in the V2 position. The interactions reflect that this difference was largest for the TD-L2 group (difference in percentages: 96.5%; b = −8.78, z = −13.73, p < .001), somewhat smaller in the SLI-L2 group (90.2%; b = −6.46, z = −10.45, p < .001), and smallest in the SLI-L1 group (77.7%; b = −4.69, z = −8.16, p < .001).Footnote 3

An additional analysis was conducted for sentences with bare verb forms such as spiel- ‘play’. Recall that whether these forms are to be considered finite or non-finite in the speech of children with SLI has been a matter of controversy in previous research. Bare forms appeared largely in the V2 position, but less so in the two SLI groups. Whilst in the TD-L2 group, 95.3% of bare forms (797 out of 829 cases) were in the V2 position, the SLI-L2 group's score was significantly lower, at 87.2% (536/610 cases; b = −1.13, z = 2.53, p = .011). On the other hand, there were no significant differences between the two SLI groups (SLI-L2: 87.2% vs. SLI-L1: 84%, 689/829 cases; b = −0.40, z = −0.96, p = .339) and children in the SLI-L1 group also scored significantly lower than typically-developing bilingual children (b = −1.53, z = −3.54, p < .001). Note that the same pattern was also obtained in between-group comparisons of all sentences containing non-finite forms (Table 2): SLI-L2 and SLI-L1 children produced a larger proportion of non-finite forms in the V2 position than TD-L2 children (SLI-L2: b = −1.25, z = −2.47, p = .014; SLI-L1: b = −2.22, z = −5.06, p < .001), but no significant difference was obtained between the two SLI groups (b = 0.66, z = 1.44, p = .150).

In sum, all three groups showed a strong contrast between the placement of finite and non-finite forms. Finite forms were overwhelmingly produced in the V2 position and non-finite forms appeared in positions other than V2. This contrast was found to be strongest for typically-developing bilingual children, with non-finite forms appearing in the V2 position even less often than in children with SLI. Bare verb forms were also produced less frequently in the V2 position by children with SLI (both monolingual and bilingual) than by typically-developing children.

7.2 Overt vs. null subjects

Table 3 presents an overview of the use of overt vs. null subjects in the three data sets; for the individual participant data, see Table A3 in the Appendix. Two conditions are distinguished, labelled ‘filled CP’ which do not permit subject omissions in German, and ‘unfilled CP’ in which case the grammar allows the subject to be omitted (qua topic-drop).

Table 3. Frequencies and percentages (SDs in parenthesis) of overt subjects in sentences with CP filled vs. CP unfilled in the three participant groups

The vast majority of produced sentences with a filled CP contain an overt subject, in all three child groups. The low standard deviations indicate that the individual children behaved very similarly in this respect. For all children (except one), the proportion of overt subjects was well above 90%; only the SLI-L1 child ‘David’ had a slightly lower score of 86.1%.

The mixed-effects logistic regression included the fixed effects CP (filled vs. unfilled) and Group (TD-L2, SLI-L2, SLI-L1); the variable Child was treated as a random effect. As above, the model made use of treatment contrasts; by changing the reference level of CP and Group, the different comparisons of interest could be obtained. The factor CP was included as a random slope, which significantly improved fit (χ2(2) = 13.23, p = .001). The results confirmed that the proportion of sentences with filled CPs and an overt subject were significantly higher than the proportion of sentences with unfilled CPs and an overt subject, in all three groups, TD-L2 (b = 3.18, z = 10.77, p < .001), SLI-L2 (b = 3.10, z = 8.98, p < .001), and SLI-L1 (b = 2.91, z = 9.61, p < .001). No interactions were obtained between CP (filled vs. unfilled) and Group, neither for the contrast between TD-L2 and SLI-L2 children (b = −0.09, z = −0.19, p = .851), nor for the comparison between the two SLI groups (SLI-L1 vs. SLI-L2; b = 0.19, z = 0.41, p = .680). Furthermore, proportions of overt subjects were not significantly different across all three groups. This was the case both for sentences with filled CPs (TD-L2 vs. SLI-L2: b = −0.04, z = −0.10, p = .922; SLI-L2 vs. SLI-L1: b = −0.42, z = −1.08, p = .282) and for sentences with unfilled CPs (TD-L2 vs. SLI-L2: b = −0.12, z = −0.38, p = .705; SLI-L2 vs. SLI-L1: b = −0.23, z = −0.71, p = .476).

In sum, the three groups of children behaved alike in terms of the production of overt subjects, showing the same degree of sensitivity with respect to subject omissions as to whether the CP was filled or unfilled. In CP-filled sentences, subjects were overtly produced in almost all cases, whereas in sentences in which CP was not filled, overt subjects were less common. This is consistent with the grammar of German (‘topic-drop’).

7.3 Subject-verb agreement

We also reanalysed the subject-verb agreement data that were previously presented in Rothweiler et al. (Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012, Reference Rothweiler, Schönenberger and Sterner2017) using the more advanced statistical methods that we employed for the current study to examine the CP-domain. Sentences were coded as correct or incorrect depending on whether subjects correctly agreed with the particular verbal form. In the TD-L2 group, 94.9% (N = 2898, SD = 2.3%) of all verb forms were correctly marked for subject-verb agreement, in the SLI-L2 group 75.4% (N = 1561, SD = 18.9%), and in the SLI-L1 group 72.9% (N = 2264, SD = 13.6%); for the individual participant data, see Rothweiler et al. (Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012, Reference Rothweiler, Schönenberger and Sterner2017). The mixed-effects logistic regression model included Group (TD-L2, SLI-L2, and SLI-L1) as a fixed effect and Child as a random effect. Mean proportions of correct subject-verb agreement were significantly lower for the SLI-L2 group than for the TD-L2 group (b = −1.76, z = −4.26, p < .001). Furthermore, both groups of children with SLI showed a comparably low proportion of correct agreement, with no significant difference between the SLI-L2 and the SLI-L1 group's correctness scores (b = −0.19, z = −0.48, p = .632), but a significantly lower accuracy score for the SLI-L1 group than for typically-developing bilingual children (b = −1.95, z = −4.80, p < .001).

The results of this reanalysis confirm Rothweiler et al.’s (Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012, Reference Rothweiler, Schönenberger and Sterner2017) previous finding of significantly lower accuracy scores for subject-verb-agreement marking in children with SLI than in typically-developing children. While the children of the TD-L2 group all acquired this system after two years of exposure to German, bilingual children with SLI produced considerably more errors similarly to the children in the SLI-L1 group, including not only affix omissions but also genuine agreement (aka ‘commission’) errors; see Rothweiler et al. (Reference Rothweiler, Chilla and Clahsen2012, Table 3, Appendix A and B) for details.

8. Discussion

The objective of the current study was to determine whether a supposed linguistic marker of SLI in German, the ‘vulnerable CP-domain’, applies to bilingual children with SLI. To this end, we examined a range of phenomena related to the CP-domain in bilingual Turkish–German children with SLI in comparison to two control groups, a group of bilingual Turkish–German children without SLI and a group of monolingual German-speaking children with SLI. We ensured that the children included in this study actually produce complex sentences that involve the CP-domain, e.g., subordinate clauses and wh-questions. The main findings from the current study can be summarised in the following three points. Firstly, the SLI-L2 children discriminate between finite and non-finite verb placement, albeit less strictly than the TD-L2 children. Finite verb forms preferably occur in the head position of the CP, viz. the V2 position, non-finite verb forms rarely appear in this position. Secondly, the omission of subjects is grammatically constrained in SLI-L2 children in the same way as in TD-L2 children. Grammatical subjects may only be dropped from the Spec-CP position, i.e., in cases of topic-drop, which are licensed in German. Thirdly, accuracy scores for subject-verb agreement are significantly lower in SLI-L2 than in TD-L2 children.

8.1 CP-related phenomena in SLI German

Consider first the current results in the light of previous findings on SLI in German. As regards verb placement, our finding of a clear contrast between finite verbs typically appearing in the V2 position and non-finite verbs typically not appearing in the V2 position is in line with previous studies on German child language – see Clahsen (Reference Clahsen1989) and much subsequent research – as well as with findings from bilingual children with and without SLI (Wojtecka et al., Reference Wojtecka, Schwarze, Grimm, Schulz, Amaro, Judy and y Cabo2013; Schulz & Schwarze, Reference Schulz and Schwarze2017).

A small point of deviance appears to be the distribution of bare forms such as spiel- ‘play’. While we found clause-final placement of these forms significantly more often in children with SLI (both monolingual and bilingual ones) than in typically-developing children, Schulz and Schwarze (Reference Schulz and Schwarze2017) reported the occurrence of bare forms to be restricted to V2 in TD-L2 and SLI-L2 children. Consequently, they argued that these forms (despite lacking overt finiteness markers) function syntactically as finite verbs. Note, however, that this discrepancy between the two studies is more apparent than real, as bare forms were overall very rare in Schulz and Schwarze's (Reference Schulz and Schwarze2017) data set. In their TD-L2 children there was a total of 28 bare forms (all of which appeared in V2), and in the SLI-data there were 25 cases in total, 22 of which were in V2. Thus, the significant contrast between bilingual children with and without SLI that we observed for a much larger data set (of 2,268 bare forms) is, at least numerically, also seen in Schulz and Schwarze's (Reference Schulz and Schwarze2017) data. We suggest that bare forms may constitute uninflected stems and that such uninflected forms are more common in children with SLI than in TD children; consequently, clause-final placement of these forms is also more common in the impaired children.

In contrast to the above-mentioned studies, Hamann et al. (Reference Hamann, Penner and Lindner1998: 216) reported that in the data set of monolingual German-speaking children with SLI they examined, 44% of all finite verbs appeared clause-finally in main clauses, which they took as an indication of impaired V2 movement in children with SLI. Unfortunately, Hamann et al. do not specify what they counted as a finite verb form. They mentioned (p. 215) that infinitives were coded as non-finite forms, which implies that other verb forms - including bare forms - were treated as finite. Note, however, that bare forms such as spiel- are ambiguous with respect to finiteness. Thus, one reason for the high proportion of clause-finally placed finite verbs reported by Hamann et al. (Reference Hamann, Penner and Lindner1998) might be an artefact of the way they coded ambiguous bare forms. In addition, recall that the data we examined for the current study were preselected to include children who are able to produce complex sentences including embedded clauses and wh-questions. This was not the case for the data reported by Hamann et al. (Reference Hamann, Penner and Lindner1998). Thus, another reason for their findings could be that their data include children at an earlier developmental stage.

With respect to subject omissions, we found that all participant groups followed the grammar of German, with subject omissions being largely restricted to cases of topic drop. In wh-questions and embedded clauses as well as in main clauses with filled CP, on the other hand, subjects were rarely omitted. This distribution of null vs. overt subjects is parallel to what has been reported for monolingual German-speaking children (Clahsen et al., Reference Clahsen, Kursawe, Penke, Koster and Wijnen1996). Furthermore, as regards monolingual children with SLI, we consulted the data presented in Hamann et al.’s (Reference Hamann, Penner and Lindner1998) appendix. In this data set, 23 out of 268 wh-questions and subordinate clauses (= 8.6%) did not contain an overt subject, a percentage similar to the ones we obtained in our data sets (SLI-L2: 9.6%, SLI-L1: 8.9%, TD-L2: 9.2%) indicating that illicit null subjects are rare in all participant groups.

Summarising, our findings on the spoken German of bilingual (Turkish–German) children with SLI show that while verb placement (including V2 placement) and the use of null vs. overt subjects function according to the grammar of German, subject-verb agreement is affected in these children. Although these children may produce complex sentences including wh-questions and embedded sentences, they perform significantly worse in reliably producing finite verb forms than typically-developing children. These findings are consistent with results from previous studies on monolingual German-speaking children with SLI.

8.2 Bilingualism and SLI

Bilingualism has been argued to have disadvantageous effects on global language performance. Bilingual children in each of their languages and at all developmental levels are supposed to lag behind their monolingual peers on measures of language proficiency, vocabulary, and lexical access (see Hoff, Core, Place, Rumiche, Senor & Parra, Reference Hoff, Core, Place, Rumiche, Senor and Parra2012; Bialystok, Reference Bialystok2009). This ‘bilingual delay’ has been attributed to reduced exposure and use - given that a bilingual child receives less input in each of her languages and practices each of her languages less than a monolingual child – in line with exposure-based approaches to language acquisition (e.g., Tomasello, Reference Tomasello, Kuhn, Siegler, Damon and Lerner2006; Gathercole & Hoff, Reference Gathercole, Hoff, Hoff and Shatz2007). As regards bilingualism and SLI, the former has been claimed to aggravate SLI, at least for particular phenomena (Leonard, Davis & Deevy, Reference Leonard, Davis and Deevy2007b; Blom & Boerma, Reference Blom and Boerma2017), possibly due to processing overload caused by the cumulative challenges of bilingualism and language impairment (Orgassa and Weerman, Reference Orgassa and Weerman2008).

Our results do not provide any evidence for these claims. We found that the SLI-L2 children did not perform worse than the SLI-L1 children, even though the latter had considerably more input and a much longer period of practice in German than the former. Furthermore, the SLI-L2 children did not show any global delays in language performance (relative to TD-L2 children), but instead a selective pattern of impairment, with a fully functional CP system and impaired subject-verb agreement. This pattern is hard to explain for global deficit or delay accounts, as the CP-system is arguably more complex and challenging in terms of grammatical computation and representation than the simple (relative to other languages) inflectional paradigm for subject-verb agreement in German

Another line of research regarding bilingualism and SLI highlights commonalities of typically-developing bilingual children and children with SLI, for example with respect to their developmental patterns and the kinds of errors these individuals produce – ‘two of a kind’ to use an expression from Crago and Paradis (Reference Crago, Paradis, Levy and Schaeffer2003); see also Håkansson and Nettelbladt (Reference Håkansson and Nettelbladt1993), Håkansson (Reference Håkansson2001) and Paradis (Reference Paradis2010). This notion is also not supported by the current findings. Instead, our results indicate a dissociation between impaired subject-verb agreement and an intact CP-domain, which holds for both bilingual and monolingual children with SLI and does not apply to typically-developing bilingual children. Thus, children with SLI are clearly distinguishable from typically-developing bilingual children, and are not ‘two of a kind’.

8.3 Linguistic markers of SLI in German

Several previous studies found that both monolingual and bilingual children with SLI have difficulty producing complex sentences including embedded clauses, wh-questions, and relative clauses; see Hamann, Chilla, Gagarina and Ibrahim (Reference Hamann, Chilla, Gagarina, Ibrahim and Di Domenico2017) for review. In elicited-imitation tasks, in particular, difficulties in accurately repeating complex sentences have been argued to ‘have good specificity and sensitivity in identifying SLI not only in monolingual but also in bilingual children’ (Ibrahim & Hamann, Reference Ibrahim, Hamann, LaMendola and Scott2017: 3). Note, however, that difficulty repeating complex/long sentences may be affected by a number of factors, both linguistic and non-linguistic ones. One possible non-linguistic factor is working-memory deficits in SLI (e.g., Montgomery, Magimairaj & Finney, Reference Montgomery, Magimairaj and Finney2010). This would be in line with the fact that complex sentences tend to be longer than more canonical simple sentences. Note, for example, that according to Figure 4 in Ibrahim and Hamann (Reference Ibrahim, Hamann, LaMendola and Scott2017:11), the children with SLI performed worse than the TD control groups on all sentence types tested, including supposedly simple (but long) coordinated sentences. On the other hand, their performance on the latter was somewhat better than on syntactically complex sentences involving the CP-domain (Hamann et al., Reference Hamann, Chilla, Gagarina, Ibrahim and Di Domenico2017: 30). Thus while elicited-imitation tasks may indeed be a useful tool, difficulties in correctly repeating linguistic stimuli may have a number of different sources.

Our current study has pursued a different approach. We specifically selected children who consistently produce embedded clauses and wh-questions in their natural speech, to examine phenomena that involve the CP-domain, the syntactically highest (arguably most complex) layer of clause structure. If syntactic computation and representation is genuinely affected by SLI (Platzack, Reference Platzack2001; Hamann et al., Reference Hamann, Penner and Lindner1998; Ibrahim & Hamann, Reference Ibrahim, Hamann, LaMendola and Scott2017), specifically with respect to the CP-domain, we would expect to find incorrect and/or unreliable V2 placement and illicit null subjects in the speech of German-speaking children with SLI.

The results of the present study do not provide much support for the ‘vulnerable CP-domain’ as a linguistic marker of SLI in German. We found that V2-movement (into the head position of the CP) is largely restricted to finite verbs, whereas non-finite verb forms rarely appear in the V2-position, which is consistent with the grammar of German. Likewise, while subject omissions were restricted to cases of topic drop, illicit subject omissions from other positions were extremely rare, again corresponding to the grammar of German in which subject omissions are licensed by a null constant in the highest clausal position (= Spec-CP), but not elsewhere. Furthermore, the children included in our study (both the impaired and the typically-developing ones) consistently produce embedded clauses and wh-questions with overt complementizers and wh-question words. Hence, in these children, syntactic computation and representation involving the CP-domain is not particularly affected.

Strikingly, however, the same children - and for this matter only those with SLI – scored significantly worse on subject-verb agreement. This contrast indicates persistent difficulties with grammatical agreement in SLI, even in children whose spoken output includes grammatically well-formed complex sentences. We conclude that impaired subject-verb agreement is a more suitable linguistic marker of SLI in German than the notion of a vulnerable CP-domain. Crucially, given the syntax of German, an impairment in agreement also has consequences for verb placement. Consider, for example, bare forms such as spiel- ‘play’ which in the two SLI groups were found to appear more often clause-finally than in the TD-L2 children. Bare forms are ambiguous with respect to finiteness; they may be finite 1st sg. or imperative forms or non-finite bare stems. That children with SLI produce more of these in clause-final position than typically-developing children suggests that these forms are more often left uninflected in these children. Furthermore, the two SLI groups were found to place non-finite verb forms more often in the V2 position than the TD-L2 group. These verb forms were incorrectly inflected –e and –n forms; see (3a) above. Thus, these cases again reflect the SLI's problems of encoding subject-verb agreement rather than any impairment in V2 placement.

9. Conclusion

From the perspective of clinical diagnosis and intervention, it is important to determine whether linguistic markers that were identified for monolingual children with developmental language impairment also hold for bilingual children with language impairment (relative to typically-developing bilingual children). Such linguistic markers can help to avoid misdiagnoses as part of a comprehensive diagnosis, which of course must also consider other relevant factors such as the quantity and the quality of the linguistic input the child is receiving. To this end, the current study examined spontaneous speech data of German from bilingual children with SLI in comparison to data from groups of typically-developing bilingual children as well as monolingual children with SLI. Our focus was on phenomena linked to the hierarchically highest layer of syntactic clause structure (viz. the CP-domain). In previous research, this domain has been argued to be particularly affected in SLI. In addition, we also investigated subject-verb agreement marking in these children, another proposed linguistic marker of SLI in German.

Our results indicate that impaired subject-verb agreement is a suitable linguistic marker of SLI in German. Recall that the children that went into the current study, even those with language impairment, were preselected to ensure that they actually produced complex sentences including subordinate clauses and wh-questions. While the CP-related phenomena we investigated for these children were unimpaired, subject-verb agreement was significantly affected in both bilingual and monolingual children with SLI. It is, of course, conceivable that at less advanced levels of development children with SLI experience difficulty with a range of phenomena, including those related to the CP-domain. It is also conceivable that some children with SLI overcome difficulties with SVA over time and achieve the same high level of accuracy for SVA as typically-developing childrenFootnote 4. Nevertheless it is worth noting that grammatical agreement causes problems for German-speaking children with SLI, even for children that produce complex sentences. Sensible consequences from our study for clinical practice would be to focus diagnosis for SLI in German (both monolingual and bilingual children) on subject-verb agreement and to develop intervention programs that target grammatical agreement. A sensible expectation would be that intervention measures that successfully target subject-verb agreement will (indirectly) without any extra effort improve a child's verb placement; see Clahsen and Hansen (Reference Clahsen, Hansen and Gopnik1997).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Alexander-von-Humboldt-Professorship awarded to HC, a grant by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, ‘German Research Council’) to HC (SPP ‘Language Acquisition’), and a grant to MR by the DFG (SFB 538 ‘Multilingualism’).

APPENDIX

Table A1. Language measures and sample sizes for individual participants

Table A2. Individual frequency counts for placement of finite and non-finite verb forms

Table A3. Individual frequency counts of overt subjects