Introduction

In this chapter, the focus is on how we might help students notice and pay attention to important aspects and patterns of the language that they are learning. The emphasis is on language-focused learning, the third of Nation’s four equal strands of focus or emphasis in the classroom (Reference NationNation, 2007).

We will first start by looking at the reasons why a focus on language is important and then consider the aspects of language that should be included in this focus. Finally, we will discuss some of the ways this might happen.

Nation’s Four Strands

Reference NationNation (2007) argues that a well-balanced language course should consist of four roughly equal strands:

Why Have a Focus on Language in the Language Classroom?

The idea that it is useful, or even important, to have a focus on language in the language classroom has not been without controversy. Some researchers, such as Reference KrashenKrashen (1981), have claimed that this is a waste of time, maintaining that learners will learn purely from exposure to language input in much the same way that children learn their first language. They, of course, do not receive ‘lessons’ from their parents, or caregivers, about the patterns or structures of the language they are acquiring.

In some ways Krashen is right, learners, in particular younger learners, can and do learn language implicitly in this way. However, as we have already seen in Chapter 4, Krashen’s idea that just giving learners lots of input would be enough was put to the test, so to speak, by research conducted in Canada. This research looked at the language learning of English-speaking children who had been enrolled in immersion programmes where their school classes were conducted in French. Swain and other researchers (Reference Harley and SwainHarley & Swain, 1978; Reference Allen, Swain, Harley, Cummins, Harley, Allen, Cummins and SwainAllen et al., 1990; Reference Lightbown and HalterLightbown & Halter, 1989) found that while students who had been learning French in this context benefited in terms of vocabulary development, listening, reading, and speaking skills, they failed to acquire important aspects of the grammar of the language and made serious errors when speaking or writing in French, even though they had been exposed to large amounts of input. In a follow-up study of these students in Grade 8 of secondary school (Reference Lightbown, Halter, White and HorstLightbown et al., 2002), written work reflected difficulties with spelling, function words (e.g. articles, prepositions, and pronouns), and morphology (e.g. putting a verb into the correct tense).

To explain why students in these classes had such gaps in their language knowledge, it was important to examine how the instruction they had received might differ from that of traditional classrooms. One big difference, which we discussed in Chapter 4, was that they had had limited opportunities to produce language output. Another key characteristic was the lack of opportunities to focus on grammar or on other features of the language. That meant very little attention to language form. It appeared, then, that the reason they had not acquired many of the important features of the language they were learning was because they had not noticed them. This was despite being exposed to extensive amounts of input (listening and reading) over 6 years of primary and secondary schooling. The absence of opportunities for a focus on language, and for output, had meant a lack of opportunities to pay attention to language and to notice features of the language and how it is structured.

The importance of attention in language learning is underscored in the Noticing Hypothesis (we referred to this in Chapter 3). By ‘noticing’, Schmidt means the conscious registration of features and patterns in the language. For example, learners of English may notice that a noun often ends in ‘s’ and go on to hypothesise that ‘s’ has the meaning of ‘more than one’. In his initial version of the Noticing Hypothesis, Schmidt claimed that learners do not learn anything they do not consciously attend to. In other words, no noticing, no learning! However, as we have already seen, learners can pick up features of language that they have no conscious awareness of. Schmidt later modified his theory to suggest that learning will be more effective when learners pay attention to what they are learning, in other words, the more noticing, the more the learning that will result!

The Noticing Hypothesis

Learners must notice a language form before it can be learned.

To some extent, researchers are still divided over the question of whether and to what extent a focus on language form is important. Some would query, for example, whether teaching learners grammar rules helps them use language in spontaneous production. There is, however, increasing evidence that learning about language may indeed help learners develop the implicit knowledge that they need to be able to use the language fluently (N. Reference EllisEllis, 2005). ‘The Interface Hypothesis’ argues that there is a role for teaching about language and for drawing attention to language features and patterns. The claim is that doing so will speed up the learning process and make it more efficient. In fact, paying attention during (any) learning has been described as the ‘universal solvent of the mind’ (Reference BaarsBaars, 1997, p. 304).

Why Is a Focus on Language Form Particularly Effective for Adolescent Learners?

There is evidence to suggest that providing opportunities for adolescent learners to explicitly focus on language form is even more important than it is for the younger learner. This is because around the age of puberty, as we discussed in Chapter 1, learners are capable of learning explicitly (Reference Muñoz and MuñozMuñoz, 2006). In fact, some researchers have suggested that, because their language learning abilities are different from those of younger children (Reference DeKeyserDeKeyser, 2000), adolescents need a type of instruction that allows them to use their developing analytic skills. Younger children learn both incidentally (as they happen to notice language they use) and implicitly (without paying purposeful attention). Older learners are more skilled at thinking abstractly. Their growing metalinguistic awareness means that they are more able to reflect on and talk about language (Reference Berman, Hoff and ShatzBerman, 2007), and also make comparisons and connections between their first language(s) and the one they are learning. All of these changes explain why drawing attention to features of language may, for the adolescent, be a particularly efficient way of learning.

Metalinguistic Awareness

‘Understanding of how the various components of language work’.

We saw earlier, in this chapter, that students learning in schools where they are immersed in the language they are learning and receiving lots of input were still considered to need opportunities to focus on language form. This is even more the case for learners in foreign language classrooms where the input is ‘impoverished’. In Chapter 3 we discussed how, in the typical foreign language classroom, learners do not receive anything like the amount of language input that they need to be able to build up sequences and constructions of language in their memories. There is evidence to suggest that drawing learners’ attention specifically and explicitly to language form can help to make up for this deficit and speed up the language learning process (Reference Lightbown and SpadaLightbown & Spada, 2006). It can also help students who may not have noticed aspects of language, perhaps because they lack strengths in analytic ability (see Chapter 2).

What Do We Mean by Form?

Paying attention to the form of language means that we focus on the linguistic features of the language (Reference Doughty and WilliamsDoughty & Williams, 1998). For some, this might suggest grammar. Grammar, however, is one aspect of language form but not the only one. As well as grammar, there is vocabulary, pronunciation, and the appropriate use of language according to context (i.e. pragmatics). In fact, it is difficult to give a comprehensive list of what might be meant by language form as it covers any attention to language and the way that it is used.

In Example 5.1, taken from the Year 10 Spanish classroom, Nicole has students listen to a dialogue. She asks the students to listen for the way that the woman in the dialogue asks for the price of something. In doing this she draws the students’ attention to the language the person uses, asking ‘so what does she say?’ Nicole contrasts what the woman says with the more common phrase that students are already familiar with. This focus and explanation about the way that language is used differently, in a different context, is an example, albeit brief, of focus on form (we put in bold anything that is said in the target language).

Example 5.1

In Example 5.2, from the Year 9 French classroom, Jessica has her students focus on how to use ‘fillers’ in the way that French speakers would use them. A ‘filler’ is a sound or word that is used in conversation to give the speaker time to think about what they want to say next and to signal to others that they haven’t finished speaking yet. Examples in English are ‘um, er, you know, like’.

Example 5.2

T donnez-moi des expressions pour showing that you’re thinking en français. Okay, vite, levez la main … . Give me some expressions for showing that you’re thinking in French. Okay, quick, put your hand up … Rosie Uh, wait. T Okay this is a perfect example because … Rosie’s just been thinking and she went ‘uh, wait, what are we saying again?’ Okay. So en français. Oui. […] Okay. So in French. Yes. S Donc. So. T Donc. Oui. So. Yes. S Euuh. Er. T Euuh … Alors. Er … then. Students Alors. Then. T If you want to say wait – Attends. If you want to say wait – ‘Attends’. Students Attends Wait.

In Example 5.3, we have an example of how a teacher briefly focuses her students’ attention on an aspect of grammar during a lesson. In this example, Margaret gives her Year 11 students, in their third year of learning French, an explanation of how to say what someone’s name was, referring to past instead of present time:

Example 5.3

T Il s’appelait, s’appelait. So if you’re writing about someone in the past and you wanted to say what he was called, you wouldn’t say il s’appelle, that’s ‘he is called’ … Il s’appelait, ok? Il s’appelait. He was called.

Focusing on Form in the Language Classroom

There seems little doubt that a focus on form in the language classroom is important. However, ideas about how to do this have changed somewhat as research has led to greater understanding about how languages are learnt. More traditional approaches to teaching grammar tended to have the idea of implanting specific grammatical features in the learner. In these classrooms, the teacher would usually choose a particular language feature and plan a lesson around it. Often, the lessons would start with the explanation of some grammar point followed by the requirement to practise the grammar in quite controlled exercises. This has been called an ‘isolated’ approach to focus on form (Reference Spada and LightbownSpada & Lightbown, 2008), because the primary aim of the lesson is to teach students about a particular language feature and this feature occurs in activities that are separate from the communicative use of language. This isolated approach to focus on form is similar to what is often called, in the research literature, a Focus on FormS (the use of the capitalised ‘S’ helps differentiate this approach from Focus on Form).

Increasingly in classrooms today, however, there is a greater emphasis on creating opportunities for students to use language to communicate, that is, to convey meaning or information. Often lessons are planned not so much around the teaching of language structures, but around how these opportunities to use language will be provided. This does not mean that a focus on form is less important, it means, rather, that the attention to form will arise out of these attempts to understand and use language. In interacting and using language, learners can attend to and learn about language form. Arguably it is at these times, when students may notice the gap between what they hear or want to say and their knowledge of what it means or how to say it, that learning can be most effective. Reference Spada and LightbownSpada and Lightbown (2008) say that this type of focus on form is integrated. In the literature, this type of approach is often called a Focus on Form.

Focus on Form

Attention is given to language form while students are engaged in meaning-oriented activities/tasks.

Below is an example of integrated focus on form from the Year 10 Spanish classroom. Nicole explains to the students that they are each going to get a shopping list. They will also get four playing cards, each of which depicts a different item. The aim is for them to acquire the items on their list from others in the group they are seated with, by asking them whether they have the cards for the listed items. The teacher explains that this activity will give them practice using the Spanish language they would need to go shopping. She starts by reminding the students of the type, or register, of language that they will need to use in this particular context.

Example 5.4

T We’re going to use a really polite language, because we’re in the shops, and when you’re going to the shops you use polite language to the shopkeeper.

Nicole then reminds the students of some of the phrases that they might find useful in performing this activity. These include: ‘Tiene usted …?’ (Do you have …?), ‘Necesito’ (I need) and ‘Déme’ (Give me).

She then gives some information about ‘déme’:

This is actually the high-level ‘you’ form. This is ‘give me’, we’re using the formal ‘you’; it is polite in Spanish.

In this example she is reminding students that there are two verb forms when using a command in the singular in Spanish and that in a context where you are shopping (as opposed to amongst friends) you need to use the polite, more formal form. After this reminder, the students play the game that she has set up for them and Nicole goes around the class answering questions, giving help and rewarding students who are speaking Spanish with frijoles (beans) that they can later redeem for prizes.

Why might this sort of attention to language form be particularly useful in helping students acquire language form? Researchers would say that it allows learners to make ‘form-meaning mappings’. When students have the opportunity to pay attention to language form in a context where they are actually using the language to communicate something, then they can make a connection between what they want to say and how to say it.

Form-Meaning Mapping

A connection between a language form and the meaning it encodes (Reference VanPatten, Williams, Rott and OverstreetVanPatten et al., 2004). For example, understanding that in English, a verb ending in -ed refers to something that happened in the past.

In this section we have presented two main approaches to focusing on language form: Focus on FormS, where the attention is on ‘isolated’ or discrete aspects of language; and Focus on Form, where the attention is on aspects of language in the context of meaningful communication. In actual fact, as Reference Spada and LightbownSpada and Lightbown (2008) point out, these two approaches are not completely distinct but rather at opposite ends of a continuum. There can be a place for both types of attention to form in the classroom (Reference EllisEllis, 2012), as we will see from examples that we will examine in greater detail below. Teachers may decide to allocate time out of the lesson to explain and focus attention on specific language forms that students might not otherwise notice, followed by opportunities (not necessarily in the same lesson) to use these forms in meaningful communication. There may also be times when either one of these two approaches might be more effective than the other.

One argument, however, against an isolated focus on form (i.e. Focus on FormS) is that it can be demotivating for some students, especially for those who are younger and at the beginning stages of learning. This was highlighted in an interview reported in

Reference Erlam and EllisErlam and Ellis (2018). A teacher

was asked whether she provided isolated explicit

instruction about new grammatical structures for her Year 9 students. She commented:

The students this teacher was talking about were beginner language learners. There would be a greater need for them to understand language structure as they progressed further with the language.

Having established the importance of having a focus on form in the language classroom, in the next part of this chapter we will look at some of the many different ways in which a teacher may do this.

The Power of Corrective Feedback

In recent years there has been a lot of interest in the research literature on corrective feedback and on the potential for learners to benefit in their learning from this type of focus on form (e.g. Reference LiLi, 2020; Reference Mackey, Goo and MackeyMackey & Goo, 2007; Reference Russell, Spada, Norris and OrtegaRussell & Spada, 2006). Example 5.5 is from Jessica’s classroom.

Corrective Feedback

Corrective feedback is given in response to learners’ errors. It provides them with information about what is not possible in the target language. It often, but not always, involves providing the correct language form.

Example 5.5 Translation Explanation Chanelle Parce qu’elle c’est bizarre. Because she it’s weird. Chanelle uses two subject pronouns in this utterance. T Elle est bizarre. She’s weird. Teacher corrects the error. Chanelle Elle est bizarre. She’s weird. Chanelle repeats the correction.

In the above example Chanelle is taking part in a conversation where she has the chance to give her opinion about the singer Lorde. When she makes a mistake, the teacher notices it, corrects it, and Chanelle repeats the correction. The reason that this type of focus on form is considered to be so powerful is that the corrective feedback gives Chanelle the opportunity to notice the gap between what she says and what should be said, and so learn how the language works (see Chapter 4). Researchers claim (e.g. Reference LoewenLoewen, 2005) that learning is likely to happen in this type of integrated focus on form where the learner is using language to communicate.

Corrective feedback need not be restricted to something that the teacher does. In Example 5.6, also from Jessica’s classroom, we have an instance of a student correcting another student. There has been some concern in the past (e.g. Reference McDonoughMcDonough, 2004) that students may provide incorrect feedback for each other and that this could lead to them learning inaccurate or incorrect language forms. The feedback that the student in Example 5.6 gives is correct and, in actual fact, this might not be as unusual as some have predicted. Reference Erlam and Pimentel-HellierErlam and Pimentel-Hellier (2017) examined all the feedback and language help that students gave each other during three lessons in Jessica’s classroom and found that out of a total of forty-six instances, in only seven (fifteen per cent) did students receive feedback that was not correct. Another interesting thing to point out about Example 5.6 is that the aspect of language form that is focused on is pronunciation.

Example 5.6

Translation Explanation S1 Pas de probl/ɒm/. No worries. S1 mispronounces problème [problem]. S2 Pas de probl/ɛm/. No worries. S2 corrects the error.

Reference Erlam and Pimentel-HellierErlam and Pimentel-Hellier (2017) suggest that one really positive aspect of teaching languages to adolescents is that they may be more prepared to correct one another when they make errors than, say, the adult learner who is perhaps less willing to want to appear more expert than their fellow classmates (Reference Philp, Walter and BasturkmenPhilp, Walter, & Basturkmen, 2010). This would appear to be the case especially in classrooms where adolescents have spent a lot of time together and know each other well.

In both Examples 5.5 and 5.6, the focus on form was what we would call ‘reactive’ in that it was in response to an error that had already taken place. It also involved an exchange that was directed, in each case, to one student only. In the following example Jessica decides during a lesson to briefly take time out to deal with a language feature that she had not previously intended to focus on, but that she decided during the lesson it would be advantageous to do so. This is because she has noticed a gap in the students’ knowledge; that is, that they don’t know the word in French to use to refer to a ‘sportswoman’. She therefore decides to give them some feedback to help with this, during a task, with the attention of the whole class. (This lesson is explained in greater detail in Chapter 6.)

Example 5.7

Translation Comment T Now I just wanted, I just heard one thing and I also saw it in the marking that I did. When you talk about un sportif préféré are you talking about a sport or a sportsman? The teachers’ reason for stopping the class seems to be that she realises that students know the word for sportsperson in French when referring to a male, but not the form to use when talking about a woman. Students Sportsman. T Sportsman so maintenant dites-moi mon sportif préféré.Comment faire ça avec la version feminine, mon sportif pour un garçon, ma … Sportsman so now tell me, my favourite sportsman.How do you put that in the feminine form ‘mon sportif’ for a male, ‘ma …’ S ma my T sportive pour une fille, oui. ‘Sportive’ for a female, yes

In Example 5.7, the feedback that Jessica gives in response to noticing that students are making errors because they don’t know how to use the word for ‘sportswoman’ in French, is very similar to an explanation. In the next section, we will look at explanations in more detail and at how they can be used to focus learner attention on language form.

Giving Explanations and Rules

Explanations aim to help students understand specific aspects of language. One issue that teachers may have to think about is how much metalanguage to use when giving explanations, that is, how many technical terms to use in talking about language. Learners can be given explanations in simple, non-technical language, and in fact, there is evidence to suggest that this is how they may best remember them (Reference Elder, Erlam, Philp, Fotos and NassajiElder, Erlam, & Philp, 2007). In the example given below, Jessica gives an explanation that will help her students understand how they might extend and develop their ideas, going beyond giving just simple answers to questions they are asked. However, notice that rather than using technical language like ‘conjunctions’ or ‘text connectors’, she uses the simpler term ‘developing words’. Another interesting feature to notice with this example is that, rather than just telling students what the options are, Jessica tries to elicit these from the students themselves.

Example 5.8

T … one thing that you will need to do in your assessment is to, um, think about how to develop [your ideas]. What are some developing words? … Charlotte Mais But T Mais, … what might you follow mais with? Mais? But [… ] S Je n’aime pas I don’t like T Mais, je n’aime pas, exactement, oui. What are some other developing words? … But, I don’t like, exactly, yes. [… ] S Aussi. Also. T Aussi is a good one, oui, bien. What are some other developing words? Also is a good one, yes, good. […] S Parce que. Because. T Parce que(pause)uh hum. So … you make yourself more interesting by developing what you’re saying, Because

In this example, it was Jessica, the teacher, who initiated the explanation and language focus. However, explanations are not always teacher-initiated. In Example 5.9 it is the student who asks for an explanation and so initiates a focus on language. We would argue that the potential for the student to learn from this brief focus in Example 5.9 is high, because they have noticed that they don’t know this particular form that is essential for what they want to communicate (e.g. Reference Swain and HinkelSwain, 2005; Reference GassGass, 1997). That is, they have noticed the gap between what they want to say and can say (see Chapter 4). This is another example of integrated focus on form because it occurs in a context where the student is focused on conveying meaning.

Example 5.9

Translation Comment S Is reading ‘livres’? Is reading ‘livres’? The student is asking if the word for reading is the same as the word for books. T Ah livres, les livres sont des books, oui. Mais lire, si tu veux dire I like reading, lire. Ah livres, livres are books, yes. But to read, if you want to say I like reading, ‘lire’ S I know T read S I know T Les livres, so they’re linked – which is funny ’cause in English they’re not are they? Jessica helps the student to see that the word for read and book are lexically related in French (lire, livre), while they aren’t in English.

Something else to notice in Example 5.9 is that Jessica makes a comparison for her student between the English and French. Comparing language features between either a learner’s first language, or another language which they know, and the language that they are learning is one way of drawing attention to and explaining how language ‘works’. As we saw at the beginning of this chapter, it is a way of developing learners’ metalinguistic awareness.

Giving explanations can include helping students understand rules about language. We have an example below, in Figure 5.1, from a Year 11 Japanese language classroom. The teacher, Shona, wants her students to learn the rule for ‘before’ sentences in Japanese. However, Shona has designed the activity so that the students have to induce, or work out for themselves, what the pattern is. She has given students the following instructions for how to do this activity:

Before Sentences Starter Sheet

You need to translate these sentences into English according to what you think makes the best sense. Each sentence is a ‘before’ sentence. Once you have translated the sentences, see if you can figure out the formula for this structure, and write a sentence of your own with its appropriate translation.

The formula is …

Notice that, in the exercise in Figure 5.1, the students first had to translate the ‘before sentences’ into English. In translating these sentences, the students would realise that in Japanese you need to mention the action that you ‘did before’ last. So, for example, the second sentence is translated as ‘Before I go to school, I brush my teeth’ but it actually reads, in the Japanese, something like: ‘go to school before brush my teeth’. In Figure 5.2, we have one student’s version of the rule that she wrote in her book after completing the exercise shown in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Worksheet from Year 11 Japanese classroom

Figure 5.2 Student’s written version of the rule for ‘before’ sentences

In deciding to have her students work this rule or pattern out for themselves, Shona took an inductive approach. She may have felt that it was likely that they would learn it more effectively than if she took a deductive approach and just told them what the rule/pattern was. It is generally believed that ‘people learn more by doing things themselves rather than being told about them’ (Reference ScrivenerScrivener, 2005, p. 3). This approach also fits with the ‘levels of processing’ hypothesis (Reference Craik and LockhartCraik & Lockhart, 1972). Having to think about and analyse language is likely to lead to deeper processing than just being told about it. It is for this reason that Annabel says she takes an inductive approach to teaching grammar. Annabel is a teacher of Year 11 Chinese students in a co-educational private school.

Levels of Processing Hypothesis

The most important factor in learning is the quality of mental activity in the mind of the learner at the moment that learning takes place.

One possible disadvantage of an inductive approach, however, is that students may not induce or ‘get’ the rule at all, or they may induce it incorrectly. A solution is for teachers to give the rule or pattern at the end of the lesson where students have had time to try and establish it for themselves. In fact, Shona’s students were told that when they had completed the ‘Before Sentences Starter sheet’, they had to explain to Shona ‘how before sentences are formed’. It is easy to imagine that, if a student had induced the incorrect rule/pattern, Shona would help them establish what the correct one was.

There may be a place for both deductive and inductive approaches to focus on form in the language classroom (Reference EllisEllis, 2006). In fact, these approaches are not completely distinct but exist at opposite ends of a continuum. Simple rules that are not too difficult for students to work out may be best taught inductively (as in the example seen in Shona’s classroom in which students were able to correctly establish the rule for ‘Before sentences’ in Japanese). Complex rules and those features that are non-salient (not obvious) may be best taught deductively. That way the teacher can explicitly draw learners’ attention to connections between form and meaning. Individual learner differences may also need to be taken into consideration when making decisions about how to approach teaching features of language. Learners who are more skilled in grammatical analysis (for example, students who may already be familiar with a language other than their first language) may benefit more from an inductive approach than those who are less skilled or who have specific learning differences (see Chapter 2).

The type of language exercise that students worked at as they completed the ‘Before Sentences Starter Sheet’ (see Figure 5.1) looks like an example of an isolated type of focus on form (i.e. Focus on FormS). This is because it would seem that students worked at this exercise in a context where they were not using the language communicatively (Reference Spada and LightbownSpada & Lightbown, 2008). However, this is not entirely the case. Shona’s students were busy solving a murder mystery and, in order to be able to understand and establish a timeline of events leading to the murder, they had to learn about ‘Before sentences’. In other words, they had a real reason to need to know this language. We will look, below, at some other ways that Shona and other teachers have created exercises that helped students understand and learn about different aspects of the language and that were also motivating.

A Focus on Learning Vocabulary

The language-focused learning strand of a language curriculum must allocate time for deliberate attention to learning vocabulary (Reference Nation, Macalister and NationNation, 2011), as well as to other language features. In classes that we observed, we saw teachers making time for this. In one beginner Japanese classroom, we saw the teacher starting the lesson with revision and the learning of katakana symbols, holding up cards and asking the Year 10 students to name the symbols. At the end of this same lesson, she again made time for students to test each other in pairs, using coloured cards. On the back of each card there was a mnemonic or an explanation of each katakana symbol aimed to help learners remember it. For example, to help them remember the katakana symbol for ‘ku’, the students were given the mnemonic ‘ku’ for ‘kuchi’ (or mouth) with a picture on the reverse of a card to help them think of a mouth from a side profile talking (see Figure 5.3). Interestingly, when we asked students what they enjoyed about this lesson, a number said that the katakana practice was a highlight of the lesson for them. We wondered if, in particular, they enjoyed the competitive nature of it, seeing who could name the most symbols correctly.

Figure 5.3 A card with the katakana symbol for ‘ku’

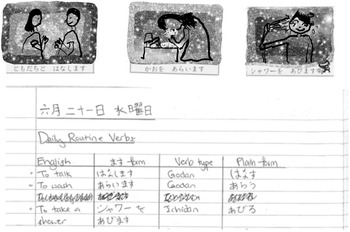

In Shona’s classroom, we saw students extending their knowledge of vocabulary. They had learnt, using word cards, a series of common daily routine verbs such as to talk, wash, shower, and so on (see Figure 5.5). In order to be able to use these verbs correctly they had to learn what type of verbs they were, so that they would know how to conjugate them, that is, how to use them with different pronouns and tenses. Shona gave them a classifying exercise (see Figure 5.4 for the instructions the students received) so that they could identify the categories they belonged to, which had implications for how they would be used. This exercise was part of the highly motivating Murder Mystery unit that Shona’s students worked at and which we have already referred to. Note that Shona, during this unit, no longer referred to herself as the teacher, she had become the Police Chief.

Figure 5.4 Japanese classifying exerciseFootnote 1

Figure 5.5 shows an extract from a student’s exercise book as this student worked at the exercise in Figure 5.4. When the students had completed the exercise, they worked at another exercise aimed to practise, consolidate, and test their learning (see Figure 5.6).

Figure 5.6 Testing verb conjugations

Another way to have a focus on language form in the classroom is to have learners complete grammar exercises. There is a risk that grammar exercises could be tedious and demotivating for the adolescent language learner, but we found examples that appeared to be very engaging for these students!

Exercises to Encourage Students to Understand and Learn Language Form

These examples, and the ones that we will consider below, came from Shona’s Japanese classroom where, as we have seen, students were working at a series of lessons in a ‘Murder Mystery’ unit. The ultimate aim of the unit was for the students (referred to as ‘detectives’) to identify who in the school had murdered the deputy principal. Along the way, students had to establish a number of facts, including the identity of the victim, the timeline of events, the motive, and so on. In order to be successful in establishing all the information they needed to be able to solve the Murder Mystery, students had to be introduced to a number of language structures. The grammar practice exercises that students worked at, and which we will look at below, were preceded by explicit

grammar explanations to help students understand the specific grammatical features in question. This is important to point out because there is evidence that explicit instruction plus practice leads to learning, but less evidence for the effectiveness of practice alone. For Shona’s students, some of the grammar explanations were provided for them on a video which they accessed via their class learning platform. Shona explained:

In Figure 5.1, we saw how Shona’s students had to formulate a rule to help them learn about ‘Before Sentences’ in Japanese. Later, Shona’s students completed a ‘sentence construction’ exercise (Reference Simard and JeanSimard & Jean, 2011), to give them lots of practice with these ‘Before’ sentences. Notice from Figure 5.7, however, that this exercise was in the form of a game.

Figure 5.7 The ‘Before sentences’ game

In order to play this game, students were given a game board and a pile of ‘verb’ cards (as in Figure 5.5) depicting different actions. It is interesting to notice that, in this game, students would not only be working at formulating sentences. They would also be keen to ensure that their teammates were correct, so they would also be involved in listening to input and in checking that it was correct. If it wasn’t correct, the student in question couldn’t roll the dice and move forward.

At a later stage of the Murder Mystery unit described above, Shona’s students needed to know language used for descriptions, in particular language used to describe clothing, to help them establish the identity of the murder suspects. They were given information about how to talk about what one ‘wears’, which is complicated in Japanese because different verbs are used, according to where the clothing is worn. The students were given a ‘sentence completion’ exercise requiring them to provide the missing ‘wear’ verb in each sentence (Figure 5.8).

Figure 5.8 Sentence completion exercise

In another ‘structured output/guided sentence’ exercise (see Figure 5.9), Shona gave her students further practice with descriptions, this time encouraging them to write a complete description in Japanese.

Figure 5.9 Structured output/guided sentence exercise

It is important to note that these exercises, on their own, might not have been very motivating for students and thus not very effective in terms of promoting learning of the different language forms they targeted. However, in designing a murder mystery unit, Shona ensured that students needed to learn these forms so as to be able to establish who had murdered their deputy principal. We therefore observed Shona’s students working conscientiously and enthusiastically at these exercises that otherwise might have been considered dull and boring. This underscores a key point that we want to make in this chapter, which is that learning about language form will be much more effective in a context where students are using this language communicatively (i.e. using it as a tool to find something out or to convey a message).

What Language to Focus on in the Language Classroom

Teachers may have choices not only in how to focus on language, but also on what aspects of language to focus on. On the other hand, some teachers may be following a syllabus and so feel that they have less freedom. For those teachers that do have some choice, Reference Nation, Macalister and NationNation (2011) says that in making selections about vocabulary, the priority should be words that occur with high frequency in the target language. In terms of language structures, instruction should focus on those which students need in order to be able to use language in the ways they would want to. Reference EllisEllis (2012) also suggests that it might be best to focus on structures that learners find difficult and on those which are partially acquired, as learners may be developmentally more ready to learn these.

As we have already pointed out, the method of having a focus on language form is another consideration. Some forms are complex and perhaps best learnt incidentally, whereas others which are simpler may be more appropriate for a classroom focus. Whatever the choice of language form is, and whatever the method that the teacher chooses for drawing learner attention to this form, it is important to remember that the effects of language-focused instruction may be more evident over time than straightaway. As we emphasised in Chapter 3 where the focus was on input, students need continual exposure to language forms in order to acquire them and so that they will be able to use them spontaneously in communication.

Finally, we finish this chapter with two messages of caution, taken from Reference Nation and MacalisterNation and Macalister (2010). They point out that some language classes need to reduce, rather than increase, the amount of language-focused learning they plan for, so that it takes no more than twenty-five per cent of classroom time. They also point out that language-focused learning must be seen as a support, rather than as a substitute, for learning through meaning-focused activities.