Introduction

The Natufian was a semi-sedentary hunter-gatherer culture that occupied the Levant during the Terminal Pleistocene (e.g. Belfer-Cohen Reference Belfer-Cohen1991; Valla Reference Valla and Levy1995). Natufian sites in the Mediterranean woodland area of the southern Levant include curvilinear structures with stone foundations, intensively used cemeteries with diverse burial customs, ground stone tools and bedrock features, decorated art objects and evidence for dog domestication (Davis & Valla Reference Davis and Valla1978; Belfer-Cohen Reference Belfer-Cohen1988; Valla Reference Valla1988; Weinstein-Evron Reference Weinstein-Evron1998; Bocquentin Reference Bocquentin2003; Dubreuil Reference Dubreuil2004; Rosenberg & Nadel Reference Rosenberg and Nadel2014). As such, the Natufian culture was innovative in many ways. Natufian subsistence relied on systematic plant gathering and processing, evidenced by flint sickle blades and ground stone tools, and by the intensified hunting of gazelles and small game (Unger-Hamilton Reference Unger-Hamilton, Bar-Yosef and Valla1991; Dubreuil Reference Dubreuil2004; Munro Reference Munro2004; Edwards Reference Edwards2006; Bar-Oz et al. Reference Bar-Oz, Yeshurun, Weinstein-Evron, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013; Yeshurun et al. Reference Yeshurun, Bar-Oz and Weinstein-Evron2014). These practices are considered to have played a major role in initiating the ‘agricultural revolution’ in the Near East, thereby lending special importance to the accurate determination of their chronologies (e.g. Valla Reference Valla and Levy1995; Belfer-Cohen & Bar-Yosef Reference Belfer-Cohen, Bar-Yosef and Kuijt2000).

The geographic expansion of the Natufian is broadly divided into two provinces: the Mediterranean woodland area and the more arid belt (Belfer-Cohen & Goring-Morris Reference Belfer-Cohen, Goring-Morris, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013; Goring-Morris & Belfer-Cohen Reference Goring-Morris, Belfer-Cohen, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013; Richter et al. Reference Richter, Arranz, House, Rafaiah and Yeomans2014). The settlement pattern in the Mediterranean area, where Raqefet Cave is situated, includes semi-permanent settlements and other sites that were probably designated for burials (Figure 1). The latter are considered indicators of “boundaries between various regional groups” (Goring-Morris et al. Reference Goring-Morris, Hovers, Belfer-Cohen, Shea and Lieberman2009: 205). Some of the Natufian graves display complex funerary practices reflecting an elaborate social system (Garrod & Bate Reference Garrod and Bate1937: 14–19; Belfer-Cohen Reference Belfer-Cohen1988; Byrd & Monahan Reference Byrd and Monahan1995; Bocquentin Reference Bocquentin2003; Grosman et al. Reference Grosman, Munro and Belfer-Cohen2008; Nadel et al. Reference Nadel, Danin, Power, Rosen, Bocquentin, Tsatskin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Weissbrod, Rebollo, Barzilai and Boaretto2013).

Figure 1. Map showing major Natufian sites in the Mediterranean core area of the Southern Levant. Raqefet Cave and el-Wad are marked in red.

Natufian chronology

The rich archaeological record is used for determining the relative Natufian chronology and is conventionally divided into Early and Late phases, although some scholars (e.g. Valla Reference Valla and Levy1995) divide it into three phases: Early, Late and Final. This paper follows the two-phase division that combines the Late and Final into a single phase. The most commonly used criterion for distinguishing between these phases is that of the microlithic lunates, which were originally part of composite hunting tools (Bocquentin & Bar-Yosef Reference Bocquentin and Bar-Yosef2004; Yaroshevich et al. Reference Yaroshevich, Kaufman, Nuzhnyy, Bar-Yosef, Weinstein-Evron, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013). Larger lunates shaped by bifacial retouch, known as Helwan lunates, are typically attributed to the Early Natufian, whereas smaller backed lunates characterise the Late Natufian (e.g. Bar-Yosef & Valla Reference Bar-Yosef and Valla1979; Valla Reference Valla1984; Goring-Morris Reference Goring-Morris1987). This chronological scheme is based upon the stratigraphic sequence of two major sites, Eynan and el-Wad Terrace (Garrod & Bate Reference Garrod and Bate1937; Valla Reference Valla1984; Kaufman et al. Reference Kaufman, Yeshurun and Weinstein-Evron2015), and is often used for determining the chronology of undated Natufian sites.

Natufian radiocarbon chronology is based on more than 120 radiocarbon dates, which supposedly represent the entire Natufian sequence (Maher et al. Reference Maher, Banning and Chazan2011: tab. 3; Grosman Reference Grosman, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013: appendix). Many dates, however, are on materials from poorly defined contexts or were produced by old dating techniques, such as decay counting. Recent attempts to refine the Natufian chronology based on published data applied several screening criteria to reduce uncertainties and errors. Maher et al. (Reference Maher, Banning and Chazan2011: tab. 3), for example, excluded 34 published dates from their analysis that had large standard deviations or unclear archaeological contexts; single dates and old 14C determinations were also excluded. Materials problematic for dating (e.g. burnt bones from the old excavations at Raqefet and Hatoula, or charcoal from old excavations at Jericho), however, were not excluded. Moreover, no control was applied regarding charcoal characteristics (i.e. old wood effect), and no details were provided on charcoal preservation.

The chronology proposed by Grosman (Reference Grosman, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013) relies on 23 dates attributed to the Early Natufian and 78 dates attributed to the Late Natufian. It is not specified which dates were excluded from the chronological scheme, but the database (Grosman Reference Grosman, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013: appendix) is very similar to that of Maher et al. (Reference Maher, Banning and Chazan2011: tab. 3). Dates were excluded from the analysis if they met one of three conditions: a) a large error range (more than 300 years); b) they were prepared before the beginning of the 1980s; or c) the age result is 2000 years older or younger than expected.

Blockley and Pinhasi (Reference Blockley and Pinhasi2011) rely solely on four Natufian sites for their chronology: Eynan, Hayonim, Nahal Oren (samples from not always clearly defined contexts) and Raqefet Cave (old excavation with unreliable contexts; see Lengyel Reference Lengyel2007). In our view, this scheme, based exclusively on four sites, does not represent the entire range and nuances of the Natufian radiometric chronology.

To avoid such limitations, we chose to focus on recently produced dates from two nearby sites from Mount Carmel as a case study for Natufian chronology, which are from well-defined, high-quality contexts. Accordingly, we here present new dates obtained from the recent excavations at Raqefet Cave and compare them to the published dates from el-Wad Terrace (Eckmeier et al. Reference Eckmeier, Yeshurun, Weinstein-Evron, Mintz and Boaretto2012; Weinstein-Evron et al. Reference Weinstein-Evron, Yeshurun, Kaufman, Eckmeier and Boaretto2012; Caracuta et al. Reference Caracuta, Weinstein-Evron, Yeshurun, Kaufman, Tsatskin and Boaretto2016). The dates from these sites, excavated using similar modern methods, and with samples extracted from secure contexts, enable us to establish a radiometric chronological framework into which the lunate assemblages from these sites can be incorporated.

Raqefet Cave

Raqefet Cave is situated in an inner wadi (Raqefet) on the south-eastern side of Mount Carmel (Figure 1). The site was first excavated between 1970 and 1972 (Noy & Higgs Reference Noy and Higgs1971). Renewed excavations from 2004–2011 (Nadel et al. Reference Nadel, Lengyel, Bocquentin, Tsatskin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Bar-Oz, Bar-Yosef Mayer, Beeri, Conyers, Filin, Hershkovitz, Kurzawska and Weissbrod2008, Reference Nadel, Lengyel, Cabellos, Bocquentin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Brown-Goodman, Tsatskin, Bar-Oz and Filin2009, Reference Nadel, Lambert, Bosset, Bocquentin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Weissbrod, Tsatskin, Bachrach, Bar-Matthews, Ayalon, Zaidner, Beeri and Grinberg2012; Lengyel et al. Reference Lengyel, Nadel, Bocquentin, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013) revealed that the Natufians used the site primarily for burials, as evidenced by 29 adult, child and infant interments (Figures 2–5; Nadel et al. Reference Nadel, Lambert, Bosset, Bocquentin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Weissbrod, Tsatskin, Bachrach, Bar-Matthews, Ayalon, Zaidner, Beeri and Grinberg2012). Four graves had directevidence of a lining, composed of a thick layer of plant material, including sage flowers (Nadel et al. Reference Nadel, Danin, Power, Rosen, Bocquentin, Tsatskin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Weissbrod, Rebollo, Barzilai and Boaretto2013).

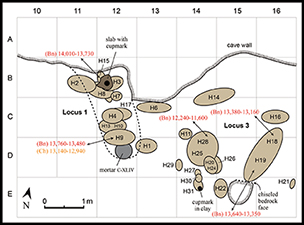

Figure 2. Plan of burials in the first chamber, Raqefet Cave. Bn = dated bone; Ch = dated charcoal.

Figure 3. Locus 1 during excavation, looking south-east. Human bones of several individuals are visible. Note the use of stone objects, and the slab with a cupmark on top.

Figure 4. The double burial of Homo 25 and Homo 28.

Figure 5. Homo 19 during excavation.

A further aspect of note at the site is the wide variety of features hollowed out of the bedrock (Nadel & Lengyel Reference Nadel and Lengyel2009; Nadel et al. Reference Nadel, Filin, Rosenberg and Miller2015; Nadel & Rosenberg Reference Nadel and Rosenberg2016). Stones set on edge were found in a few of the larger, rock-cut mortars (or deep shafts), and phytoliths were recovered from several deep mortars (Power et al. Reference Power, Rosen and Nadel2014). The flint assemblage contains over 20000 artefacts, and is currently undergoing detailed analyses (Nadel et al. Reference Nadel, Lengyel, Bocquentin, Tsatskin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Bar-Oz, Bar-Yosef Mayer, Beeri, Conyers, Filin, Hershkovitz, Kurzawska and Weissbrod2008; Lengyel Reference Lengyel2009; Lengyel et al. Reference Lengyel, Nadel, Bocquentin, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013). Two samples from the richest loci (1 and 3) were analysed as part of the current research (Table 1). This corpus of flints was recovered from the immediate surroundings of the burial pits or from within the graves, and should be viewed as representing the cemetery as a whole. In both loci, flakes are the dominant product, comprising just over 50 per cent of the total assemblages. Bladelets are approximately four times more common than blades. Tools encompass 7.9 and 6.4 per cent of the lithic assemblages from loci 1 and 3 respectively. In these loci the lunate assemblage (n = 200) is dominated by the abruptly backed type (89.5 per cent). The abrupt category includes both unipolar and bipolar specimens, and a mixture of both (Figure 6). The Helwan lunates include fully and partially retouched specimens (Figure 7), and eight specimens that have both Helwan and some abrupt retouch. According to the commonly used relative Natufian chronology (e.g. Bar-Yosef & Valla Reference Bar-Yosef and Valla1979; Valla Reference Valla1984), this proportion of abruptly backed lunates aligns the Raqefet assemblage with the Late Natufian phase.

Table 1. A breakdown of flint samples from loci 1 and 3 according to blanks (Raqefet Cave). Note the high similarity between the two loci.

Figure 6. Lunates from Raqefet Cave. 1: Abrupt (locus 1, C12a, 222–228); 2: abrupt and bipolar (locus 3, 195–200); 3: bipolar (locus 3, C15d, 190–195); 4: Helwan (locus 3, E15a, 210–214); 5: Helwan and abrupt (locus 3, 193–200).

Figure 7. SEM image of a Helwan lunate (locus 1, B12d, 223–238).

Comparing complete Helwan (n = 12) and abruptly backed lunate (n = 104) lengths shows that the former lunates are significantly larger than the latter (t (114) = –2.377, p = 0.019) (Table 2).

Table 2. Dimensions (in mm) of complete lunates from loci 1 and 3, according to type (Raqefet Cave).

Flint from the grave fills may not be directly associated with the dated human remains. Such lithics must be either contemporaneous or earlier to have been included in the burials. The relationship of the burials with the materials in the fills was, however, examined taphonomically in the study of the faunal remains from locus 1; these food remains were interpreted as representing funerary feasts, rather than domestic Natufian refuse accumulated prior to the digging of the graves (Yeshurun et al. Reference Yeshurun, Bar-Oz and Nadel2013).

The radiocarbon dates

We obtained eight radiocarbon dates (see Table 3 for details) from Raqefet: five from human long bones belonging to five individuals (three adults and two adolescents), and three from charcoal pieces found in association with the burials.

Table 3. 14C dates from Raqefet Cave and el-Wad. The Raqefet Cave dates of Homo 18, 19 and 28 from Nadel et al. (Reference Nadel, Danin, Power, Rosen, Bocquentin, Tsatskin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Weissbrod, Rebollo, Barzilai and Boaretto2013), the el-Wad dates from Weinstein-Evron et al. (Reference Weinstein-Evron, Yeshurun, Kaufman, Eckmeier and Boaretto2012) and Caracuta et al. (Reference Caracuta, Weinstein-Evron, Yeshurun, Kaufman, Tsatskin and Boaretto2016). Eight samples from el-Wad were excluded from this table as they were either too old (RT 6097-2, RTD 6957 and RTD 6958) or their cultural context was not secure (RTT 6114, 6095-2) (Weinstein-Evron et al. Reference Weinstein-Evron, Yeshurun, Kaufman, Eckmeier and Boaretto2012: 820–21).

The charcoal specimens were taxonomically identified and pre-treated following the standard water-acid-base-acid procedure that was also used for the el-Wad Terrace samples (Eckmeier et al. Reference Eckmeier, Yeshurun, Weinstein-Evron, Mintz and Boaretto2012). The five bones were pre-screened using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, which determined their splitting factor and the preservation of collagen (Rebollo et al. forthcoming). Sediments adhering to the bones were removed before pre-screening and their mineralogical composition was analysed. Bone samples were prepared following the ultrafiltration method of Bronk Ramsey et al. (Reference Bronk-Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004). Quality control of the suitability of the dated samples was carried out for each sample. All radiocarbon dates were calibrated using IntCal13 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013) and OxCal v4.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009). All samples were prepared and measured at the Dangoor Research Accelerator Mass Spectrometer D-REAMS for Radiocarbon Dating at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

The new set of dates from Raqefet Cave clusters between 14000 and 13000 cal BP, except for RTK 6638, which dates to around 12000 cal BP (Figure 8). The stratigraphy, spatial distribution of the burials and radiocarbon dates indicate that the site was used as a Natufian burial ground over many generations. The earliest burial phase is locus 1 (Figure 3), which saw the burial of at least ten individuals between 14010 and 13480 years cal BP. This range is derived from the dating of the lowest burial in the northern cluster (Homo 15, RTK 6481) and the uppermost burial in the southern cluster (Homo 9, RTK 6541). These dates confirm the diachronic progression of the burials in the rock basin, starting from the north, adjacent to the wall of the cave, and continuing towards the south (Lengyel et al. Reference Lengyel, Nadel, Bocquentin, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013). Dating of charcoal from the southern cluster may extend the use of this location to 13140–12940 year cal BP. The radiometric results show that this location was used for burial for approximately 500 years, and possibly more.

Figure 8. Probability distribution of the calibrated radiocarbon dates from Raqefet Cave and el-Wad Terrace. Colour codes refer to material type: red: human bone; orange: animal bone; black: charcoal.

Other dated graves were double interments in the adjacent locus 3. The double grave containing Homo 18/Homo 19 was dated to 13640–13160 cal BP and the double grave of Homo 25/Homo 28 was dated to 12400–11600 cal BP.

Discussion

Recent evaluations of available radiocarbon dates have proposed that the Natufian lasted approximately 3500 years, between c. 15000 and 11500 cal BP (e.g. Goring-Morriset al. Reference Goring-Morris, Hovers, Belfer-Cohen, Shea and Lieberman2009; Bar-Yosef Reference Bar-Yosef2011; Blockley & Pinhasi Reference Blockley and Pinhasi2011; Grosman Reference Grosman, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013). This time span is usually further divided (mainly based on lithic typology) into two major phases: the Early and Late Natufian. The changeover is considered to have occurred at approximately 13500 cal BP. Our new results from Raqefet Cave demonstrate that the postulated shift from Early to Late Natufian may have occurred earlier than previously suggested. The radiocarbon dates from the Raqefet Cave burials, in association with the proportion of backed lunates in the graves, sets the beginning of the Late Natufian at Mount Carmel to around 14000 cal BP, if the two phases are defined by their lunate assemblages. Consequently, the Late Natufian lithic assemblage at Raqefet Cave falls within the commonly accepted time range of the Early Natufian (Goring-Morris et al. Reference Goring-Morris, Hovers, Belfer-Cohen, Shea and Lieberman2009; Bar-Yosef Reference Bar-Yosef2011).

This chronology is supported by comparing the Raqefet Cave results to the neighbouring Natufian site of el-Wad Terrace, located 10km to the west (Figure 1). El-Wad Terrace provides one of the most detailed and best-dated Natufian sequences in the Mediterranean core area (Weinstein-Evron et al. Reference Weinstein-Evron, Yeshurun, Kaufman, Eckmeier and Boaretto2012; Kaufman et al. Reference Kaufman, Yeshurun and Weinstein-Evron2015). The Early Natufian at el-Wad Terrace is represented by a thick layer (>1m) containing structures with living floors, and overlying occupation levels with no architecture. The lithic assemblage from the Early Natufian contexts is clearly dominated by large Helwan lunates (Kaufman et al. Reference Kaufman, Yeshurun and Weinstein-Evron2015).

Comparison between the lunate assemblages from Raqefet Cave and el-Wad Terrace shows differences between the sites. El-Wad Terrace units 1–2 and W0, which are the two uppermost Natufian levels, are the closest to Raqefet Cave in the Helwan: abrupt ratio. The latter, however, has a higher proportion (almost 25 per cent) of backed lunates (Table 4). Hierarchical cluster analysis of the proportions of the two types of lunates in each assemblage shows two groups (Figure 9). The smaller group includes Raqefet Cave and el-Wad units 1–2 and W0; the rest of the el-Wad assemblages comprise the larger group.

Table 4. Frequencies of Helwan and backed lunates along the el-Wad sequence (Kaufman et al. Reference Kaufman, Yeshurun and Weinstein-Evron2015).

Figure 9. Hierarchical cluster analysis of Raqefet Cave and el-Wad Terrace using the proportions of abruptly backed and Helwan lunates.

The el-Wad phases were recently radiocarbon dated and clearly show a continuous occupation for the Early Natufian between 15000 and 13200 cal BP (Figure 7) (Eckmeier et al. Reference Eckmeier, Yeshurun, Weinstein-Evron, Mintz and Boaretto2012; Weinstein-Evron et al. Reference Weinstein-Evron, Yeshurun, Kaufman, Eckmeier and Boaretto2012). Evidence for the Late Natufian is sparse and dates to 13700–11800 cal BP. The early age of sample RTK-6955 (charcoal) at el-Wad shows overlap there between the Early and the Late Natufian. Being a single date, it was, however, suspected to be an outlier. Now, the new Late Natufian dates from Raqefet Cave suggest the RTK-6955 sample is not an outlier. A comparison between the absolute chronology of Raqefet Cave and the Early Natufian absolute chronology of el-Wad shows an overlap of approximately 1000 years, between around 14000 and 13000 cal BP. Thus, the latest Early Natufian of el-Wad Terrace and the earliest Late Natufian of Raqefet Cave are contemporaneous.

The well-established dating results from these two sites raise a question concerning the differences between the contemporaneous lithic assemblages. The distinct lunate compositions (in terms of type frequencies and dimensions) from the two sites are apparently synchronous and thus they cannot be interpreted as reflecting chronological phases. Similarity in ecological setting (e.g. Caracuta et al. Reference Caracuta, Weinstein-Evron, Yeshurun, Kaufman, Tsatskin and Boaretto2016) and the limited geographic distance between the sites would seem to exclude the possibility that the two communities did not interact. One plausible explanation for the typological difference is that there was a long intermediate phase between the Early and the Late Natufian during which the two lunate types coexisted (Kaufman et al. Reference Kaufman, Yeshurun and Weinstein-Evron2015). Although the presence of the two types together in Natufian sites has usually been interpreted as a mixture of two chronological phases, this a priori assumption has been questioned for several sites in the southern Levant (Olszewski Reference Olszewski1986, Reference Olszewski1988; Barzilai et al. Reference Barzilai, Agha, Ashkenazy, Birkenfeld, Boaretto, Porat, Spivak and Roskin2015). The use of lunates as a relative chronological marker has been further challenged by the discovery of small lunates modified by Helwan retouch at the open-air sites of Hof Shahaf and Shubayqa 1 (Marder et al. Reference Marder, Yeshurun, Smithline, Ackermann, Bar-Yosef Mayer, Belfer-Cohen, Grosman, Hershkovitz, Klein, Weissbrod, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013; Richter et al. Reference Richter, Arranz, House, Rafaiah and Yeomans2014). Their position within Natufian chronology is currently unknown due to the lack of radiocarbon dating.

Another explanation for the typological differences between Raqefet Cave and el-Wad Terrace may be found in the social sphere. Ethnographic studies show that projectile style can convey social information (e.g. Wiessner Reference Wiessner1983). Thus, it is possible that the typological differences in lunate types, commonly used as projectiles (Yaroshevich et al. Reference Yaroshevich, Kaufman, Nuzhnyy, Bar-Yosef, Weinstein-Evron, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013), may attest to social identity. Raqefet Cave functioned primarily as a Natufian burial ground, whereas el-Wad Terrace was a settlement including dwellings, burials and a variety of features (Garrod & Bate Reference Garrod and Bate1937; Weinstein-Evron Reference Weinstein-Evron1998, Reference Weinstein-Evron2009). That no settlement evidence was found at Raqefet Cave (Nadel et al. Reference Nadel, Lengyel, Bocquentin, Tsatskin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Bar-Oz, Bar-Yosef Mayer, Beeri, Conyers, Filin, Hershkovitz, Kurzawska and Weissbrod2008, Reference Nadel, Lengyel, Cabellos, Bocquentin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Brown-Goodman, Tsatskin, Bar-Oz and Filin2009, Reference Nadel, Lambert, Bosset, Bocquentin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Weissbrod, Tsatskin, Bachrach, Bar-Matthews, Ayalon, Zaidner, Beeri and Grinberg2012, Reference Nadel, Danin, Power, Rosen, Bocquentin, Tsatskin, Rosenberg, Yeshurun, Weissbrod, Rebollo, Barzilai and Boaretto2013) suggests that the site must have been used as a burial place for a Natufian settlement nearby. The difference between the lunate assemblages at Raqefet Cave and el-Wad, as well as the presence of burials at el-Wad, suggest that the former was not the burial site of the latter. Thus it is possible that the Raqefet Cave cemetery represents a geographic marker that distinguished between two co-existing Natufian communities, each with its different lithic tradition (i.e. lunate types) within Mount Carmel and maybe also the valleys to the east.

The current case study highlights a common archaeological problem: namely, the integration of relative and absolute chronologies. Natufian sites in the Mediterranean woodland zone are stratigraphically complex and include archaeological contexts that were subjected to a variety of taphonomic processes. It is crucial, therefore, to retrieve materials for absolute and relative dating (e.g. radiocarbon and lithic typologies) from the same secure contexts, such as graves and living floors. Our study shows that the Raqefet Cave cemetery was used for many centuries and that the fossil directeur of the Natufian, the lunate, is not a suitable chronological marker in the Mount Carmel region for the period between 14000 and 13000 cal BP.

Our results therefore question the reliability of the commonly used lunate-based relative dating of the Natufian. This applies to the Mediterranean zone, but may have implications for other regions. Hence the use of tool types as a proxy for dating Natufian phases (and probably also phases in other periods and places) should not be considered sufficient to support a high-precision chronology. Furthermore, only specimens retrieved from secure contexts should be incorporated in such relative dating schemes, and wherever possible they should be compared to context-specific radiocarbon dates. It is hoped that additional case studies will enhance the resolution of our dating of the Natufian, and thus further illuminate the complex processes that led to the establishment of sedentary communities and the development of agriculture in the Near East.

Acknowledgements

This work forms part of a post-doctoral research project conducted by O.B., supervised by E.B. (ISF grant 475/10). Fieldwork was carried out under licence numbers G-2004/50, G-34/2006, G-64/2008, G-34/2010 and G-22/2011 of the Israel Antiquities Authority, and permits of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. The Irene Levi-Sala CARE Archaeological Foundation, the National Geographic Society (grant 8915-11) and the Wenner-Gren Foundation (grant 7481-2008) generously supported the excavation. Teresa Cabellos Panades, Aurore Lambert and Gabrielle Bosset assisted in the excavation of the burials. Michal Birkenfeld prepared Figure 1. Anat Regev-Gisis prepared Figures 2, 6 and 7. We thank N. Taha from the Basin Analysis and Petrophysical laboratory (PetroLab) at the University of Haifa, and N. Waldmann and R. Reshef for their help in documenting the lunates. E. Gershtein prepared the photographs of lunates.