Urban historiography has established that political projects have spatial dimensions, often cast in the form of cities. For example, nation-states need cities as embodiments of their power, and those of Southeast Asia are no exception. Viewed from the vista of official nationalism, the capital city thus occupies an exalted space within the geo-body of the nation as the best spatial representation of the imagined community.Footnote 1 Southeast Asian studies has benefited from scholars who have analysed and interrogated the interplay between nationalism and the construction of cities. Much of this discussion has focused on how capital cities are invested with symbolic capital in the form of architecture and city planning, however.Footnote 2

This article gives a new angle to the study of nationalism vis-à-vis urbanism by analysing the emergence of a would-be capital city of a would-be independent nation-state. Looking at the establishment of Quezon City in 1939 as the future capital city of the Philippines, one can easily see how it seems to conform to the established literature. To begin with, Quezon City was an imagined city, in more ways than one, for a Philippine nation that was about to change from being a colony of the United States to a sovereign nation-state. Also, the local elite, the main articulators of Filipino nationalism, led in planning and constructing the city to turn it into a spatial emblem: from the symbolic monuments to the wide avenues and open spaces to evoke grandeur and modernity. From a postcolonial vista, Quezon City appeared to be the city that would replace colonial Manila, a metropolis characterised by disorder and decay. The early history of Quezon City tells a different story: on the one hand, the elite used nationalism as a smokescreen for devious personal and political objectives in pushing for the new capital; on the other hand, resistance from marginalised stakeholders and Quezon City's contradictions reveal the city's precarious ideological foundations.

The visionaries behind Quezon City were the Filipino elite, led by Commonwealth president Manuel Quezon (1935–44). The president occupies a special position in the conventional narrative of Filipino nationalism because he played an active role in both the revolutionary and the ‘parliamentary’ phases of the formation of modern Philippines.Footnote 3 As such, Quezon has been the subject of numerous studies and biographies, perhaps more than any other historical figure in the Philippines aside from José Rizal. The early biographies ranged from pre-Second World War authorised biographies to early postwar hagiographies. Since the 1980s, however, biographies of Quezon have become more critical, as they point out not just his ‘misdemeanours’ but his regime's systemic corruption.Footnote 4 More importantly, scholars like Alfred McCoy and Donovan Storey have established the links between Quezon City and its founder's authoritarianism.Footnote 5 In emphasising his dictatorial stamp on the city, however, they neglected evidence that Quezon City was part of Quezon's larger framework of using a system of chartered cities to consolidate his power. They also failed to consider how contradictions between intent and reality undermined Quezon City's putative ideological place in the coming nation-state. By elaborating on these gaps, this article seeks to contribute new insights to the growing literature on Philippine and Southeast Asian urban history.

This article is based on the same primary sources cited in these biographies and earlier studies. Important government documents include the annual reports of the High Commissioner and of the President, Quezon's speeches and messages, and the 1939 census. The annual reports of the Board of Regents are a crucial source about the University of the Philippines (UP), one of the most important state institutions in the early history of Quezon City. Contemporary periodicals complement official documents because they present non-state perspectives, but vary in their political biases. The Quezon Papers of the Philippine National Library are a treasure trove of archival data about the President's life, but I have not obtained much information about the early history of Quezon City from it, apart from published government documents included in the collection. Instead, I have turned to published accounts of key personalities during the Commonwealth period, such as Quezon's autobiography, a political treatise by Vice Governor Joseph Ralston Hayden, and the recollections of Quezon City treasurer Pio Pedrosa.

The Commonwealth period: Remapping Greater Manila

Quezon City was established during the Commonwealth period, a ten-year transition beginning in 1935 that would supposedly prepare Filipinos for eventual self-rule after more than three decades of US colonial rule. Long-time prominent politician Manuel Quezon was elected president and spearheaded a Filipino government that, though still under US sovereignty, had control over practically all aspects of domestic rule. The Commonwealth period also represents the culmination of the Filipino elite's negotiations in Washington for a definite date for the transfer of sovereignty. Starting in 1919, Filipino politicians regularly sent representatives to Washington on so-called ‘independence missions’, which ended when the 1934 Quezon mission secured the passage of the Tydings–McDuffie Act, which established the Commonwealth government and guaranteed Philippine independence ten years after.Footnote 6

The Commonwealth period does not only signify an administrative transition; it also represents the pinnacle of official Filipino nationalism, which the American colonial state had encouraged for decades. Leading the way were elite politicians, scholar-bureaucrats, and intellectuals who had long harnessed a brand of civic nationalism that was both acceptable to the coloniser and palatable to the Filipino electorate. One important manifestation of this paradoxical colonial relationship was the establishment of key state institutions that defined official Filipino culture, such as the National Library and the National Museum, in the early decades of American rule.Footnote 7 The Commonwealth government took this to a higher level as it founded more institutions that aimed to develop a national consciousness: from linguistic nationalism, as embodied by the Institute of National Language, to economic nationalism, as defined by the National Economic Council and the state-supported National Economic Protectionism Association.

State-sanctioned civic nationalism also had spatial dimensions. Throughout the colonial period, the question of a capital city had been a preoccupation of the Filipino elite. Although a comprehensive urban plan in 1905 seemed to have ensured Manila's status as capital city for the decades to come, the elite's vision of a nation led them to contest the colonial masterplan. At the onset of American rule, the Philippine Commission envisioned a capitol site and civic centre in Manila. The 1905 Burnham Plan became the blueprint for this project, which aimed to develop an expansive government and civic complex in Ermita. Implementing the Burnham Plan became one of the chief tasks of the consulting architect, a government position created following the abolition of the Bureau of Architecture. While the first consulting architect, William Parsons, gradually but meticulously began to execute Burnham's plan,Footnote 8 only a few aspects of this blueprint were to come to fruition. After Parsons’ resignation in 1914, the plan was essentially neglected by his successors, who had little faith in it. In a letter dated 18 October 1928, acting consulting architect Juan Arellano informed Quezon of his opposition to the Burnham Plan. Rather than implementing Burnham's idea, Arellano advocated putting up the government centre at Marikina Heights.Footnote 9

Manila's urban problems, already apparent and alarming by the 1930s, also served as a disincentive for Filipino politicians to invest resources in creating a government centre in the present capital city. Sanitation and traffic congestion were just a few of these problems. The most pressing of all was the housing crisis: thousands of Manila residents lived in congested informal settlements with inadequate basic services, especially in the central districts of Binondo, Quiapo, San Nicolas, Tondo, and Intramuros. Americans often complained about the overcrowded conditions and the housing shortage in the downtown area from the early years of colonial rule up to the eve of the Pacific War.Footnote 10 These slums in the once-prosperous districts of Manila, like Intramuros and the southern tip of Santa Cruz, were an affront in the eyes of the colonial elite. Philippines Free Press journalist Leon Ty provided vivid descriptions of the squalor and indignity that informal settlers, mostly workers and migrants from the provinces, were subjected to. In the slums of the Intramuros, monthly rent for a room was P12 pesos without light (water was free of charge), although one could have P8 rooms in Quiapo, or even P7 ones in Sampaloc and Paco.Footnote 11

President Manuel Quezon and Vice President Sergio Osmeña were aware of this problem. Though government concern had led to housing projects, especially in light of Quezon's choice of social justice as the main thrust of his administration, initiatives such as the barrio obrero (workers’ community) in Avenida Rizal, Sta. Cruz, and in Barrio Vitas, Tondo, failed miserably.Footnote 12

Manila's housing crisis was one of the more important factors behind the development of the suburbs just outside the city limits. Starting in the 1920s and throughout the 1930s the municipalities of Pasay, San Pedro Makati, San Felipe Neri (eventually renamed Mandaluyong), San Juan del Monte and San Francisco del Monte became favoured sites of real estate developments that attracted middle- and upper-class residents who wanted to escape Manila without cutting off their economic links to it. As a result, a Greater Manila Area had emerged by the 1930s.Footnote 13

The suburban surge was so significant that politicians wanted to redraw the boundaries of Manila to include these new municipalities. Quezon was a vocal supporter of this proposal. In 1938, Quezon backed the move to include Malabon, Caloocan, San Juan, Pasay, and San Pedro Makati — all of which were towns of Rizal province — into an expanded territory of Manila. Nonetheless, the proposal failed due to the opposition of Rizal politicians and real estate developers.Footnote 14

Though Quezon failed to remap Manila, he succeeded in making something bigger: the conjuring of an entirely new, purpose-built city. Even if Manila did not expand its territory, Quezon would still get what he wanted, which was to alter the boundaries of the rapidly growing Greater Manila Area. The founding of Quezon City in 1939 did not only mark the total abandonment of the Burnham Plan; it also demonstrated Quezon's keen interest in the Greater Manila Area and wider urban issues.

Establishing Quezon City

To a large extent, Quezon City was the product of Quezon's ‘imagination’. And just like most momentous undertakings, the creation of Quezon City also has its own ‘official narrative’.

The oft-repeated story of the founding of Quezon City credits Alejandro Roces Sr. as the influence behind Quezon's vision: ‘It was his [Roces's] conception of a model workers’ community which fired the enthusiasm of President Quezon, who thereupon gave Don Alejandro practically a free hand to carry the project through to completion.’ As one contemporary commentator remarked, ‘Don Alejandro looks upon the Quezon City project as a personal monument.’Footnote 15 As the official story goes, Quezon, in a breakfast with Alejandro and his son Ramon, talked about his dream of having a city where the common tao (people) could grow ‘roots’ and ‘wings’. It was at this point that the elder Roces suggested to Quezon to purchase a sizeable tract of land for this purpose.Footnote 16

Quezon ordered Ramon to identify lands near Manila for expropriation to be sold to low-income families at a low price. Ramon sought the help of Bobby Tuason, who then talked to his aunt Doña Teresa Tuason, who owned the Diliman Estate. The Philippines government already had a previous commitment to Teresa Tuason when it expropriated part of her land for road projects. What followed was a Malacañang meeting that involved Secretary of Finance Manuel Roxas, Secretary of Justice and Philippine National Bank (PNB) chair Jose Abad Santos, PNB President Vicente Carmona, and Alejandro Roces. The problem, however, was that the government had no available funds except for a P3 million fund in the name of the National Development Company (NDC).

To mobilise the said funds, Quezon called for the creation of the People's Homesite Corporation (PHC). The PHC, a subsidiary of NDC, became the main state vehicle for the realisation of Quezon's vision. Organised on 14 October 1938, the PHC had an initial capitalisation of P2,000,000. Alejandro Roces became PHC's chairman of the board and worked with board members Ambrosio Magsaysay, Vicente Fragante, Jose Paez, and Dr Eugenio Hernando. PHC immediately acquired the Diliman Estate at a cost of 5 centavos per square metre (sq m).Footnote 17 Two days after the delivery of the cheques to Bobby Tuason, TCT No. 35979, Rizal (now No. 1356, Quezon City), was issued to the PHC. As the administrator of the property, the PHC's initial task was to conduct topographical and subdivision surveys and, ultimately, to subdivide the land into residential lots and sell them to the target buyers at an affordable rate.Footnote 18 The PHC also worked with the Bureau of Public Works, then under Secretary Vicente Fragante, in the construction of highways and streets within the property. Quezon also asked Juan Arellano to draft a design for the city. A key component in the initial planning of the Diliman Estate under PHC was the extension of the Metropolitan Waterworks system to the site.Footnote 19

The city that Quezon envisioned appeared to be the culminating urban project of the decades-long struggle to democratise the landed estates in the suburban frontier. To create Quezon City, eight big estates were acquired: the centrepiece was the Diliman Estate (15,732,189 sq m); the other estates were the Santa Mesa Estate (8,617,883 sq m), Mandaluyong Estate (7,813,602 sq m), Magdalena Estate (7,644,823 sq m), Piedad Estate (7,438,369 sq m), Maysilo Estate (2,667,269 sq m), and the San Francisco Del Monte Estate (2,575,388 sq m). The ostensible beneficiaries were Manila's working class, who had been suffering from a shortage of decent and affordable housing in the capital. Quezon's planned city was to serve as a haven for them where they ‘could live like men and not like hogs’.Footnote 20 As Quezon declared in a 1939 press release, ‘Social welfare can only be built on decent homes’. In the same press release, he also promised that the government would provide the residents of the new housing estate with basic services, from transportation to markets, schools, and even amusement houses.Footnote 21

Quezon's stated goal of creating low-cost housing projects out of state-purchased estates coincided with another major goal of his administration for the Greater Manila Area: the transfer of the UP campus in Manila to a more suitable location. Similar to the housing situation, urban congestion was the problem that Quezon saw as a pressing concern for the country's premier university. It was a move that was supported by other prominent politicians such as Manuel Roxas.Footnote 22

Years before the creation of a capital city, there were already serious plans for the transfer of the UP campus from Ermita to a less urbanised location. The revised Burnham Plan, for example, envisioned the new campus at the ‘heights behind Manila’.Footnote 23 As early as 1922, UP President Guy Potter Wharton Benton had already considered relocating the campus to a ‘100-hectare site in San Juan, Rizal, but the plan fizzled out’.Footnote 24 The plans gained more traction when in 1938 university officials contracted Purdue University President Charles Edward Elliot and Dean Paul C. Packer of Iowa University to study the relocation proposal. Both consultants advised that the campus be moved.Footnote 25

The UP Board of Regents (BOR) acted on this advice and informed Quezon of its decision to relocate the campus, gaining the President's support. In Quezon's 1939 state of the nation address, he stressed that UP needed a new campus to improve its facilities and to ensure that students are ‘brought under a more strict and wholesome supervision and control, and the proper spirit and atmosphere may be created on the University campus’.Footnote 26 Moreover, Quezon wanted the facilities in the Manila campus to be used for government purposes. In light of these points, Quezon urged the National Assembly to enact UP's relocation during the 1939 session. The National Assembly obeyed the chief executive's instructions, and on 8 June 1939 it passed Commonwealth Act 442, enacting the transfer of UP to a site outside Manila, with a P17,500,000 appropriated budget.Footnote 27

Act 442 authorised the BOR to choose the relocation site. Quezon and UP President Jorge Bocobo, a known Quezon ally, were the most decisive figures in the deliberations regarding the choice of the new campus. In the end, the BOR adopted Bocobo's proposal and recommended that UP

be transferred to a place contiguous to the City of Manila and that for this purpose that portion of the Mariquina Estate (adjacent to the Diliman Estate) which is owned by the Philippine National Bank, with an approximate area of 600 hectares, be selected.Footnote 28

Aside from the portion of the Mariquina Estate, UP officials also added a part of the Diliman Estate (around 1,600 ha) that was located near Calle España.Footnote 29 As a result,

With the additional land, the contemplated University boundaries would be the Marikina River on the East and the provincial road to Marikina (now Aurora Boulevard Extension) on the South, the Payatas and Piedad Estates on the North, and Marikina Estate West.Footnote 30

With the legal infrastructure in place for the homesite and the new UP campus, both institutions became the main anchors for Quezon's envisioned city. Giving this city its legal existence was thus made a lot easier. The final and most important piece of legislation was passed on 12 October 1939. Commonwealth Act No. 502 was passed by the National Assembly, surprisingly with Quezon allowing the bill to lapse into law by default because he did not sign it. The law created Quezon City and served as its charter. Moreover, it enjoined state officials to plan its development as the future capital.Footnote 31

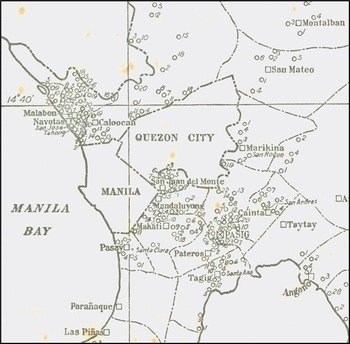

Based on its charter, one could characterise Quezon City as an ‘invented’ or an ‘imagined city’ since it was founded not on a single pre-existing settlement, but by carving out barrios from various towns to create a new city, so as to correspond with the estates that the PHC bought. Included in its original area of 7,355 ha, one-third of which were government-owned, were the following: the barrios of Bagubantay (Bago Bantay), Balintauac (Balintawak), Loma (La Loma), Santol and Masambong, which were taken from Caloocan; the barrios of Cubao, Diliman, and San Francisco, which were taken from San Juan; the barrios of Jesus de la Peña and Tanong, including the new UP site, which were taken from Marikina; and, the barrio of Ogong (Ugong Norte), which was taken from Pasig (see fig. 1).Footnote 32

Figure 1. Map of Quezon City and nearby towns, 1939

However, it did not take long for the government to consider revising Quezon City's original borders. Commonwealth Act No. 659, enacted on 21 June 1941, revised the city charter to change its boundaries.Footnote 33 Under this law, jurisdiction over the area of the Wack Wack Golf and Country Club reverted to Mandaluyong, and the barrios of Jesus de la Peña and lower Barranca were returned to Marikina. On the other hand, the area of Camp Crame was taken from the town of San Juan and added to Quezon City.

As a city carved out of the suburban frontier, Quezon City in its early years was predominantly rural. It was a ‘dream city out of a wilderness’, situated in a ‘highly malarious location’.Footnote 34 In the year the city was established it had a population of 39,103. One may argue that its demography was already exhibiting the spillover effects of Manila's early-twentieth-century urbanisation. If the population of the barrios that comprised Quezon City were tallied for the two previous censal years, one can see a population increase from 3,062 residents in 1903 and 8,789 in 1918. Between 1903 and 1918, the city posted an average population increase of 12.5 per cent per year, while between 1918 to 1939, this rate accelerated to 16.4 per cent. Nevertheless Quezon City's rurality remained apparent in other aspects, especially in comparison with Manila. For example, 1939 census records show that Quezon City had 964 farms, amounting to 2,123.21 ha, in contrast to Manila's thoroughly urban geography. Out of this area, 1,518.65 ha were cultivated.Footnote 35

The cosmopolitan Quezon, of course, did not want a rural wilderness to be the predominant image of the city that bore his name. Moreover, he was clear and persistent in his aim to turn Quezon City into the national capital eventually.Footnote 36 Hence, Quezon City had to conjure images of grandeur and national unity, with an expansive layout complemented by magnificent edifices that would house government offices. As such, Quezon had a vision in planning and took an active role in it to ensure that Quezon City would rise as a modern city. Around October 1939, Quezon even cabled Osmeña, who was then in the United States, to ‘study the park and recreation facilities of modern countries abroad’.Footnote 37

Quezon turned to five consultants for the urban plan of Quezon City. He first asked William Parsons, the former consulting architect who helped in selecting the Diliman Estate as the main site for the new city, to head the project. Parsons advocated building the government complex in Diliman and not in Wallace Field, Manila, due to the possibility of bombardment from Manila Bay. After he died in December 1939 Harry T. Frost, a partner in the US architectural firm Bennett & Frost, which had been involved in significant urban improvements in Washington DC and Chicago, became the lead planner. Frost arrived in the country on 1 May 1940 and became the architectural adviser of the Commonwealth government. Under Frost were Juan Arellano, Alpheus D. Williams, former director of the Bureau of Public Works, and Welton Becket. Their master plan was approved by Philippine authorities in 1941.Footnote 38

The Frost plan featured wide avenues, large open spaces, and rotundas for major intersections.Footnote 39 Louis Croft's plan for the major thoroughfares in the greater Manila area served as the backbone for the plan for Quezon City. At the heart of the city was a 400-ha quadrangle formed by four avenues — North, West, South and East — and designed to be the future location of national government buildings. At one of the corners of the quadrangle was the main rotunda, a 25-ha elliptical site. Here, the cornerstone for the capitol was laid down on 15 November 1940, in celebration of the fifth anniversary of the Commonwealth government. Analysing the act from the vista of official nationalism, Michael Charleston Chua regarded it as ‘the nation re-offering itself for the advancement of democracy and independence’.Footnote 40 On the same date, for the first time since 1935, Quezon delivered his annual state of the nation address in Quezon City rather than in Manila.

As the spatial manifestation of official nationalism, Quezon City served as the place for the presumptive nation-state to articulate its readiness to join the international community of nations. Exemplifying this was the government's decision to hold an international exposition in this city to celebrate the sixth anniversary of the Commonwealth, the Philippine Exposition of 1941.Footnote 41 Here was a soon-to-be independent country — just three decades removed from the humiliating 1904 exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, in which Americans displayed Igorots as ‘exhibits’, a historical event that remained fresh in Quezon's mind — presenting itself to the community of nations that it was ready to be one of them. The exposition grounds covered 75 ha and included the construction of three permanent buildings. The main organiser of the Philippine International Exposition was Arsenio Luz, who had served as general manager of the annual Philippine Carnival held in Manila.Footnote 42 The official narrative woven into the Philippine International Exposition of 1941, which opened on 15 November, can be read from an advertisement it released for the event:

In a world caught in a vast whirlpool of turmoil and war, the Philippines is the one place, outside of the American continent, where one can witness and enjoy orderly progress, peaceful and contented living and unhampered pursuit of happiness.Footnote 43

The exposition, far from conveying a sense of arrogant optimism (as expositions during that time usually did), revealed the anxiety of the presumptive independent nation-state: it proffered the idea of Quezon City as a haven of peace amid the increasing turbulence at the beginning of the Second World War. This idea is contradicted by the position of Quezon City itself: it was an inland city, in contrast to coastal Manila, given that national authorities were anxious about possible attacks against the capital via Manila Bay. In fact, due to the war in Europe and escalating tensions in East Asia, the exhibition was eventually restricted to local participants.Footnote 44

After the main features of Quezon City's layout had been completed, the contrast between Quezon City and Manila became apparent. According to the influential American Chamber of Commerce:

In a city so badly equipped with wide streets as is Manila, the contrast with Quezon City in this respect is unbelievable. It is safe to say that no matter how much development should take place in the new city in years to come, there can scarcely be any traffic congestion.Footnote 45

Road planning was a significant part of Quezon City's early history, revealing the plan's civic virtue. As in the McMillan Plan for Washington DC, the city was conceived of along the lines of ‘urban renewal’. The use of American or American-trained architects and experts, as well as the notion of a planned capital, led many to draw parallels between the two cities.Footnote 46 This was no coincidence: the architects behind Quezon City also imbibed the ‘behavioralist’ school of thought behind modern Washington DC. The same notion of urban space as an influence in the behaviour of citizens had already been seen in Burnham's City Beautiful design, and remained in the ideas of Parsons and his fellow planners.

Quezon, who was most familiar with Washington DC's urban plan, saw it fit to apply the same urban ideology in his own city. Civic virtue became the underlying ideology in the founding of Quezon City: an ideal city to mold ideal citizens.

Contradiction and corruption in the City

Sergio Mistica offers an interesting anecdote regarding Quezon and the early history of Quezon City:

Once he [Quezon] overheard that some clerks were underpaid and consequently lived a most uncomfortable and miserable lives [sic]. He, therefore, decided to look into the matter, personally visiting the homes of the employees concerned to ascertain the actual conditions in which they were. Finding that the reports were true, he ordered the establishment of a colony for lowly paid employees in Quezon City to be sold to them at cost and on the installment basis.Footnote 47

This anecdote reveals how Quezon's stated intention to create not just a national capital, but a city catering to the common people was a significant part of Quezon City's official narrative. Up until the outbreak of war, housing remained a government priority, as seen in the creation of the National Housing Commission, by virtue of Commonwealth Act No. 648. Quezon's public pronouncements were consistent in their message. In his 1940 state of the nation address, Quezon explained that Quezon City was established because Manila's working-class population had been suffering from unemployment, a lack of housing, and unsanitary conditions:

In an effort to relieve Manila of a part of its congested population that can conveniently go to live in Quezon City, we have purchased a large parcel of land, known as the Hacienda de Diliman, with an area of about 1,600 hectares. The plan is to offer to government officials, especially the small salaried employees and laborers, for sale or rent, lots where they can build, or have the Government build, their homes. In the subdivision of this land there will be portions which may be acquired by private individuals, both the rich and those of moderate means.Footnote 48

Manuel Quezon reiterated this idea in his annual report to the White House and the US Congress. He pointed out how this programme gave easy terms to its beneficiaries to enable them to ‘live in healthful surroundings with modern facilities and conveniences’.Footnote 49 Thus, Quezon City's purpose was not just to be the site of a low-cost housing programme, but to be ‘a model workers’ community’.Footnote 50 The government encountered difficulties in achieving this goal, however. The inherent contradictions between Quezon City's economic and ideological foundations proved irreconcilable.

The sale of lots in the former Diliman Estate began in January 1940. The PHC auctioned the lots at prices ranging from P2.50 to P7 per sq m, payable either in cash or in instalments.Footnote 51 Quezon claimed, ‘The eagerness with which the people have responded to the opportunity of acquiring their own houses has been very gratifying, and the People's Homesite Corporation has plans for the construction of more houses.’Footnote 52 Given these prices, Quezon City became a golden opportunity for middle-class professionals and government employees to own their own houses and lots. Manila's working-class population found it difficult, if not impossible, to purchase these lots — the daily minimum wage was P1, and the floor price of P2.50 per sq m was simply out of reach for them.

Accessibility was another issue for Quezon City's prospective and actual residents; for all intents and purposes it was ‘essentially a Manila suburb’.Footnote 53 Quezon City was inhabited by workers who derived their livelihood from places of work in Manila, and Quezon himself targeted Manila-based workers as the main beneficiaries of the housing projects in the new city. As such, easy communication and transportation between the two cities were crucial:

Modernized transportation is the basic explanation of Quezon City … It [Quezon City] will fill up with the homes of folk whose work is either there, in the government, or in Manila, and the drive back and forth, even by bus, will be a matter of a few minutes only.Footnote 54

To maintain accessibility between Manila and the new city, Quezon ordered Luzon Bus Lines to go as far as Kamuning from Tutuban Station in order to provide transport services to Quezon City's residents, who still had no markets within the vicinity.Footnote 55 Unfortunately, these services were not affordable for minimum wage earners.

As a result of unaffordable prices and a lack of facilities and transport for lower income earners, the original objective of mass housing was not met. Rather, most of the original beneficiaries of Quezon's vision were middle-class households, such as in the case of Kamuning, one of the first residential communities established after the founding of Quezon City. Kamuning's middle-class character challenged the City's ‘working-class narrative’. In fact, its residents petitioned the PHC to change the name of their area: from the original Barrio Obrero to Kamuning, named after a fragrant flowering tree that grew in the area. Their reason was that they were not obreros (labourers) because the majority of them were government employees or had other white-collar jobs.Footnote 56 Furthermore, middle-class demand encouraged speculators to take advantage of the situation, a development that Quezon denounced.Footnote 57 His crusade against speculation was, of course, questionable given the fact that his family's suburban properties benefited from the development of Quezon City.

At a time when living in Manila's suburbs was a distinct part of elite consumption, the Quezon family's preference for the rustic-but-accessible came with a hefty price tag. More importantly, the Quezons’ accumulation of suburban property was a platform for his political opponents’ attacks against the President. Around mid-1929, at the height of the spat between Aguinaldo and Quezon, the former launched a public attack against the latter by revealing details about the President's questionable properties (see fig. 2). Aguinaldo listed the properties in a press release published by the major dailies:

-

1. 2,700,000 square meters of Dominican friar lands in San Felipe Neri [Mandaluyong] which are now being sold in lots.

-

2. His residence in Pasay, valued at P100,000.00.

-

3. The residence and grounds of Justice Johnson which he has recently bought for P75,000.00 cash.

-

4. A house bought in San Juan del Monte, valued at P40,000.00.

-

5. Fishponds in Pampanga, valued at P60,000.00.

-

6. Coconut hacienda (about 25,000 trees) and cattle ranch in Tayabas.

-

7. One third share in the Balintawak Estate, worth P3,000,000.00, where there is talk of building the new capitol.

-

8. Large tracts of land in Baler and in Infante [Infanta], Tayabas, which the projected railroad will traverse

-

9. Shares worth P50,000.00 in the lumber mill at Calauag, and numerous shares in other companies.Footnote 58

Source: ‘It's time to retire: Quezon–Aguinaldo fight getting tiresome’, Philippine Graphic, 7 Aug. 1929, p. 20.

Figure 2. Editorial cartoon depicting Aguinaldo searching for Quezon's supposedly questionable properties

A week after publishing Aguinaldo's tirade, the Manila Times printed Quezon's rebuttal, in which he totally denied all the allegations regarding the rural properties. He also denied that he owned a hacienda and a ranch in Tayabas or anywhere else in the country and that he had a property in Infanta; also clarifying that he had owned the land in Baler before he entered politics.

Quezon partly admitted, however, to owning the urban and suburban properties that Aguinaldo listed.Footnote 59 The Mandaluyong property was the ‘most valuable’Footnote 60 and his earnings from it had enabled him to acquire other properties. He explained that he owned 2,000,000 sq m in this estate, representing one-eleventh of the business, which he bought from Mr Whitaker and Mr Ortigas, the owners of Mandaloya Estate, on 16 July 1920 for P100,000. Quezon also mentioned that he obtained the P100,000 as a loan from the Philippine National Bank (PNB) under the guaranty of Tomas Earnshaw, a loan that he had already settled. He then went on to boast about the profitability of the said business, which, for instance sold the Magdalena Estate for P1.2 million with a P100,000 profit. From 1920 to 1929 Quezon had already earned more than P168,000. He also claimed how the Mandaloya Estate had appreciated in value because of the rise of the San Juan Heights near it.Footnote 61

As for the other properties, Quezon clarified that his Pasay house and lot cost P50,000 at the time of the construction. He then stated that the house in San Juan was acquired from real estate magnate C.M. Hoskins for P33,000. As to the house he got from Justice Johnson, he corrected this accusation by saying that he bought it from Johnson's son-in-law, Mr Gibbs, for P75,000. Regarding the Calauag lumber mill shares, he clarified that even if the book value of his shares was P50,000, he only paid P35,000 for it because of the lien on the shares. As to the Pampanga fishponds, he actually owned two, but at a total cost of P23,000. Quezon explained that he accumulated these properties through the profits he earned from the Mandaloya Estate and loans from banks and friends. As a result, he had outstanding debts of more than P150,000.Footnote 62

As if to lay down all his cards, Quezon went on to disclose other transactions and properties that Aguinaldo failed to mention. These transactions included a house and lot that he bought and resold for a P10,000 profit; and the purchase and resale of 1,600 shares in the Manila Times and of a small sum in La Vanguardia for a profit of P24,000. He also revealed that he owned a lot in Sariaya after it was given to him by the Rodriguez family; a lot in San Juan del Monte, which Quezon fondly called ‘Dalagang Bukid’, which was presented to him by a number of Manila residents as a token of appreciation for his efforts in securing the passage of the Jones Law; another lot adjacent to the house he bought from Hoskins, which he purchased from Antonio Brias for P12,000.Footnote 63

Quezon also admitted that he acquired shares in the Balintawak Estate in 1921, but clarified that the estate was capitalised at P360,100 and that his shares represented only a tenth of this value (P35,650). His partners in the ownership of this property were Senator Vicente Singson Encarnacion, Dr Baldomero Roxas, and Vicente Arias. An intriguing claim, however, is his denial that the estate would be the site of the future capital.Footnote 64 As shown above, Balintawak would actually be part of the city that Quezon himself would conjure for the would-be independent Philippine nation-state. Not only that, with the establishment of Quezon City as a priority government urban development project, real estate values in neighboring San Juan, Mandaluyong, and Marikina — places were Quezon had invested from the 1920s to the 1930s — increased almost overnight.

In responding to Aguinaldo's accusations Quezon claimed in 1929 that ‘the only thing that my business transactions show is that not only have I been lucky in some of them, but also in all modesty, I may say, that I am not entirely lacking in business foresight.’Footnote 65 Based on all these urban and suburban properties that Quezon himself admitted to owning, he had indeed demonstrated his keen business sense. However, Quezon was no real estate speculator; rather he used his political position to engineer an assured handsome return on investments.

The potential profit-making from the development of Quezon City was in fact the reason why in 1940 the US State Department investigated public expenditures in this city, along with those for Tagaytay City. The large allocations for both cities seemed illogical to the State Department because neither were populous nor economically important. The investigation concluded that the ‘profit motive’ was the reason behind these irrational budgetary outlays. On Quezon City, the State Department reported:

Without going into detail as to how profit is obtained by the politicians and their friends concerned, it may be stated that the chief methods are reportedly as follows:

-

(a) the land which now forms Quezon City was purchased for a few centavos a square meter by certain politicians and their friends who had prior knowledge of the Government's intention to create the city, and this land has not greatly increased in value;

-

(b) the People's Homesite Corporation was created to administer the development of the city, and its membership involves some of the same people involved in the land purchase; and

-

(c) the Santa Clara Lumber Company, whose personnel is identified with members of the Homesite Corporation, obtains any contract on any public project in Quezon City it desires. (The activities of Santa Clara Lumber Company are within the law as, when it submits a bid, the bid is lower than the bid of competitors, in fact unprofitably low. However, after the Homesite Corporation has awarded the contract, it alters the plans of the project, thereby freeing the Santa Clara Lumber Company from the necessity of confining itself to its original estimates.) Footnote 66

When Quezon died in 1944, he left an estate worth P309,641. The smallest portion of his estate were insurance policies valued at P30,000 and personal belongings worth P30,000. Most of it consisted of real estate, ‘distributed in various parcels of land in Baguio valued at P69,800; Pampanga, P69,540.77; Rizal and Quezon Cities, P78,301; Tayabas, P27,000; and Manila, P5,000’.Footnote 67 Clearly, a big chunk of the Quezons’ wealth came from their suburban properties. Analysing these data, McCoy stops short of stating that Quezon used Quezon City to illegally accumulate wealth because there is no direct evidence of this. Still, the circumstantial evidence is simply too difficult to ignore, and enough to cast a shadow of doubt upon Quezon's integrity as a public official.

Contradiction and conflict also marked the preparatory phase for UP's relocation, despite the fact that operations had not yet begun in the new campus. By 1941, the only establishments in the Diliman site were two concrete three-story buildings, which would only be occupied starting June 1942, when university operations would finally begin in the new campus.Footnote 68 From the perspective of official nationalism, the premier state university seemed a perfect fit in the conceptualisation of a city that was to serve as the ‘Republic's eventual realization’.Footnote 69 However, this was not the view of UP student leaders and alumni, who vigorously opposed Quezon's decision to transfer the campus to Diliman. Meanwhile, UP's position as an official nationalist symbol was effectively undermined by the fact that its new campus was near places of ill-repute that attracted its students. Cabarets, in particular, became a source of anxiety for university officials.Footnote 70

Also known as dance halls, cabarets were a popular place of leisure for men who wanted to dance and/or have a drink with young ladies called bailarinas. But as these places were perceived to be fronts for prostitution, municipal ordinances prohibited their establishment within city limits. However, these ordinances did not prevent cabaret owners from putting up their businesses just outside Manila's borders to capitalise on the huge demand from clients, who were mostly middle-class males living in the capital city. These cabarets hounded the early history of Quezon City because its territory incorporated areas where they were established, such as La Loma. UP's location, which would supposedly isolate the campus from the urban distractions of downtown, actually brought students closer to infamous cabarets such as those in Caloocan.Footnote 71

Quezon City's contradictions

Quezon's double-speak in promoting Quezon City as a model community and university town should not be surprising if read alongside his more important objective of centralising political power. The name of the city itself spoke of how Quezon treated it as a tool for his personal interests. According to stories, however, it was Alejandro Roces who was against using an American name for the new city and had suggested ‘Quezon City’. Quezon supposedly retorted: ‘Why can't you wait until I'm dead before you name anything after me?’ Roces replied that if Washington DC could be named after the founding father of the United States, then the same could be done for the new city.Footnote 72 When the legislative bill to establish Quezon City was sent to Quezon for his approval, he quibbled again over the city's name. But the members of the National Assembly prevailed upon him, and he allowed himself to be persuaded.

But Quezon City was not a mere vanity project — although the naming of Quezon City was clearly an act of vanity.Footnote 73 It was a reflection of how Quezon's urban policy served his authoritarian tendencies, a point already put forward by a number of scholars: Aruna Gopinath calls Quezon a ‘tutelary democrat’; Theodore Friend has pinpointed the ‘maldistribution of political power’ in his government; and Alfred McCoy calls the Commonwealth regime authoritarian.Footnote 74

The passage of the bill creating Quezon City cannot be understood apart from Quezon's control of the legislature. Historians have already noted how, as president of the Commonwealth government, Quezon enjoyed vast powers as chief executive vis-à-vis the other branches of government.Footnote 75 For instance, the National Assembly ‘worked closely with Quezon in passing Quezon-sponsored bills’.Footnote 76 Quezon City's charter, Commonwealth Act No. 502, is just one among many examples. Moreover, in the dealings involved in relocating UP to Quezon City, Quezon succeeded in using state funding in ‘bending lesser masters to his personal will’.Footnote 77 Quezon slashed UP's budget when its leadership opposed him; otherwise, appropriations were easy to be had. In fact, the relocation happened alongside a significant increase in the university budget.Footnote 78 This, despite the fact that the power of the purse technically belonged to the legislature.

Quezon's use of the budget as political leverage gains more significance in light of the fact that the state had huge sums of money at its disposal due to the financial intricacies of the Commonwealth government. To lighten the effects of the end of free trade due to the Tydings-McDuffie Act, the United States regularly remitted to the Commonwealth government the taxes collected from American imports of coconut oil from the Philippines. The coconut oil excise fund was such a rich source of revenue that the Commonwealth government tapped it to finance a wave of construction projects that focused on ‘large government buildings and of wide avenues in Manila, including the great Circumferential Road’.Footnote 79 It was also the source of the P2-million allocation in 1938 for the purchase of large landed estates and the P8.5 million budget for UP's relocation.Footnote 80

Quezon's de facto dictatorship was also evident in his deployment of urban politics toward the centralisation of power. Quezon City was conceived and created during a period when Quezon was pushing through the establishment of chartered cities in several key urban areas. Former vice governor-general Hayden observed that during the Commonwealth period: ‘Never in Philippine history have provincial and municipal officials been subjected to such exacting supervision by the chief executive as President Quezon has bestowed upon them.’Footnote 81 Before the Commonwealth, Manila and Baguio were the only chartered cities. However, under Quezon, the National Assembly granted charters to ten cities in a span of six years: Bacolod, Dansalan (Marawi City), Cavite, Cebu, Davao, Iloilo, San Pablo, Zamboanga, Tagaytay, and Quezon City.Footnote 82 The charters of these cities were similar to that of Manila, which meant that the Chief Executive, via the Secretary of the Interior, exercised much power over municipal affairs compared to ordinary municipalities. One important reason behind this was that the president had the prerogative of appointing and removing the mayor (even if the appointees were non-residents of the said cities) of these populous and economically important cities, in contrast to the elective mayoralty position in other towns. The provincial government, led by a locally elected governor, was effectively bypassed. As such, genuine local autonomy in urban areas had been increasingly eroded.Footnote 83 Even Quezon himself ‘frankly recognized that the new city charters mark[ed] no progress in the direction of democracy’. Moves to reverse this trend were easily quashed. When the Municipal Board of Manila demanded that the position of Mayor be made an elective one, Quezon insisted that it remained an appointive one and the proposal simply fizzled out.Footnote 84

If the other chartered cities were already controlled by the executive, Quezon City was even more dependent on its chief creator. While the city councils in other chartered cities were elective,Footnote 85 the Quezon City council was completely controlled by Quezon. As Hayden put it: ‘There is no Democratic nonsense in the charter of Quezon City.’Footnote 86 In justifying the expansive control of the national government over chartered cities to the detriment of the residents’ right to vote, Quezon cited the case of Washington DC. Manuel Duldulao believes that Quezon's preference for appointed city mayors was a practice he learned from his trips to Latin American countries, most of which were being ruled by authoritarian caudillos.Footnote 87 However, Quezon did not need to learn from the Latin American experience; his knowledge of local politics in Manila and Washington DC was certainly enough to convince him that controlling the Philippines’ urban centres would be in his interest. In a 1937 speech, Quezon deflected such criticisms by referring to his personal observations of urban governance in Western cities:

The idea of an appointive mayor is not a Filipino creation. It originated in America. There is the city of Washington, governed by a board appointed by the President. In France, prefects are appointed. … In America elective city officials have resulted in corruption, and inefficiency, so that in great cities there developed a strong feeling for the city management form of government.Footnote 88

Quezon City's dependence on Quezon was also apparent in the first city government's composition. He even acted as city mayor from 12 October to 4 November 1939, pending the resignation from another position of his intended appointee and close friend, Tomas B. Morato, who was then mayor of Calauag, Tayabas, and given the initial appointment of Quezon City chief of police.Footnote 89 So many well-known Quezon cronies comprised the local government that the ‘roster of officials [which] reads like an all-star selection’ because many already held high positions in government.Footnote 90 These appointees were known as the ‘Casiana cronies’, after Quezon's yacht where they often met to unwind. Indeed on 10 October 1939, two days before the actual enactment of the Quezon City charter, Quezon announced the appointments, led by Morato, aboard the Casiana. Director of Public Works Vicente Fragante was appointed vice mayor and city engineer. The councilors were Alejandro Roces, Jose Paez, manager of the Manila Railroad Company, and Director of Health Eusebio Aguilar, who was also named city health officer. Williams was city secretary, Pio Pedrosa appointed treasurer, while Jacob Rosenthal, a Jewish American businessman in Manila, was city assessor. Well-known educator Conrado Benitez was barrio lieutenant.Footnote 91

Despite Quezon's political dominance, the City's inherent contradictions made it vulnerable to resistance from various stakeholders. Even if Quezon exerted much influence over the three branches of government, there were still officials who opposed the President with regard to his management of the new city. First and foremost were the politicians from the municipalities whose territories were affected by the delineation of Quezon City. These officials felt that their power had been undermined because Quezon City was ‘carefully picked out, piece by piece, from the best parts of several towns’.Footnote 92 As such, Quezon City became a rallying point for anti-Quezon individuals and groups.

Juan Sumulong, a vocal Quezon oppositionist, was one of its fiercest critics. He lamented that ‘so many millions of the people's money are being wasted on a project designed to establish a separate district for the residence of the privileged classes’. He opposed the purchase of the Diliman Estate and called it ‘a waste of government money which would benefit and enrich only the hacenderos of Marikina, Caloocan and Santa Mesa, as well as the Mandaluyong and Magdalena Estates, all at public expense’.Footnote 93

Opposition to Quezon City at the grassroots level emerged almost from the beginning. As the government set out to build the infrastructure for the city, it encountered dissenting opinions from the residents themselves. For example in 1940, right-of-way problems emerged in Barrio Kangkong when the government wanted to build a 50 m boulevard there. The residents of Kangkong demanded P1 to P1.50 per sq m, but the government would only give them 20 centavos. The government justified the small amount by saying that

their properties consisted mostly of second-growth bushes and bamboo groves of little value, with a few guava trees planted by nature and one or two santol trees here and there. In fact their land has been assessed at five centavos per square meter, and no improvements were mentioned in the assessments except the nipa houses.Footnote 94

The government even asserted that they were lucky to get 20 centavos per sq m. As a result, the people of Kangkong became furious. They pooled all their land titles, hired a lawyer, and took the case to court. However, the court upheld the government's price. It maintained that Quezon City should become the new owner of the expropriated land and ordered the local government to deposit the sum needed to cover the cost of the land for the new boulevard. Amado Capellan, one of the road contractors in the Kangkong construction, described an incident when he visited the construction site. An old man with a long bolo, reminiscent of the legendary Filipino revolutionary leader Andres Bonifacio, ‘charged at the workers. Swearing, cursing, and shouting at the top of his voice, he ran toward them. The labourers fled in panic, leaving their tools.’ Capellan remembered the Cry of Balintawak and mused: ‘Was this the second “cry”?’, an allusion to the event that signalled the start of the anticolonial revolution against Spain.Footnote 95

Conclusion

Quezon City can be viewed today as an artefact that gives us a glimpse of what early Filipino politicians, and Manuel Quezon in particular, envisioned as an ideal Filipino ‘imagined community’Footnote 96 once formal colonial ties were finally severed. In discussing nationalism, the capital city cannot be disregarded for almost always, ‘It was at and from the center that the nation was imagined’.Footnote 97 Nonetheless, one has to go beyond the wide avenues, celebratory monuments, and modern urban plans to get a fuller view of the city. Quezon City's early history shows how the façade of nationalist symbols and the official narrative that they support are undermined by the very contradictions present in them. The narrative spun by nationalist politicians, as typified by Quezon's official pronouncements, hailed Quezon City as a haven for the working class and a model community. However, the predominance of middle-class households, the concerns over cabarets near UP, conflicts of interest in landownership, and resistance by the area's original farmer-settlers belie Quezon's visions of grandeur. Quezon's social justice thrust proved to be hollow in light of the city's authoritarian and corrupt foundations.

Quezon City thus illustrates what one historian has argued regarding Quezon in terms of the ‘glaring contrast between what he said he desired and what he did’.Footnote 98 Quezon City's emergence was not just a product of Quezon's urban housekeeping; it helped solidify his rule.