One prominent reason for the recurrent failure of labour legislation on domestic servants in India is the tension inherent in the phrase “domestic worker”.Footnote 1 While “domestic” indicates the realm of the private, into which the intrusion of the state should be minimal, the identity of the worker can only be realized when the state intervenes to secure rights on servants’ behalf. For instance, in 1959, in response to the demand that domestic servants should be included under labour laws, a number of provincial states responded that: “In a household, human relations are more important than statutory rights and any attempt to regulate between [sic] masters and servants will affect adversely the relation.”Footnote 2 In 2012, one of the labour commissioners entrusted with the enforcement of the Minimum Wages Act (1948), as it had been recently extended (in the 2000s) to include domestic servants in some of the states, reasoned that “restriction on implementation is an important component of the Act as one cannot disturb the privacy of households”.Footnote 3 As recent scholarly works suggest, the language of family, kinship, and “pragmatic intimacy” permeates the apparent contractual relationship between employer and employee.Footnote 4

In recent times, reluctant governments have come under intense pressure to legalize and formalize the vast working population of domestic servants. While this form of legal intervention demands the extension of social security and labour rights, in practice police verification of domestic servants has become the norm in contemporary India. This article presents a historical overview of how such practices might have come to be institutionalized. It traces the genealogy of the practice through the multiple changes that occurred during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to show that the history of the registration of servants by police authorities is nothing new, although the scale it has attained in the last few years is unprecedented. In other words, the postcolonial state has managed to realize what the colonial state variously attempted but only marginally succeeded in doing. However, based on current research, the article does not argue that the intense subordination of domestic servants increased in the postcolonial period; rather, that the practice of registration, as it emerged as a tool of control, situated within the larger presence and absence of formal mechanisms of law, has left domestic servants as “potential criminals” who warrant scrutiny from the police.

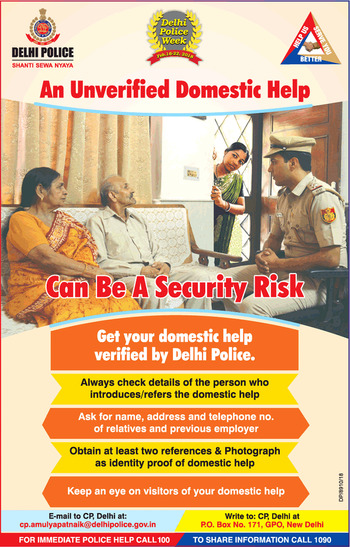

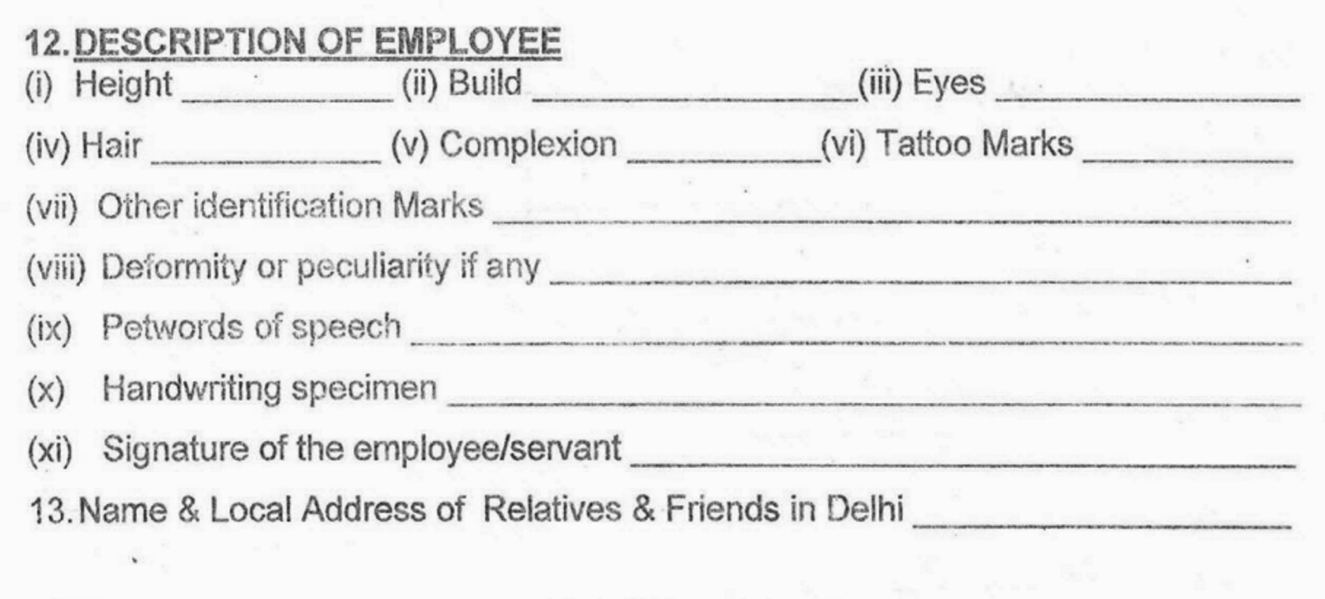

Presently, the securitization of employment relationships, in which the safety of the employer matters above all, has flourished in the absence of formal laws that govern the relations between employer and employee.Footnote 5 City-based police verification forms are easily available on different internet platforms, including city police web portals, and these need to be completed at the time of hiring domestic servants.Footnote 6 Advertisements in national newspapers encourage middle-class families to register their servants in order to ensure the safety of their homes (see Figure 1).Footnote 7

Figure 1. Delhi Police initiative to get domestic servants verified.

https://www.advertgallery.com/newspaper/delhi-police-an-unverified-domestic-help-can-be-a-security-risk-ad/ ; last accessed 1 February 2021.

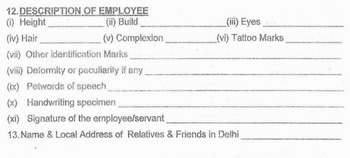

Evidently, the middle classes are apprehensive about a labour inspector entering the private setting of the household to resolve, say, wage disputes, but welcome the police because the image of the servant has been overlaid, or even fused, with the image of the criminal. Numerous advertisements placed by Delhi police have normalized this view. One such states: “Please note that a servant who is reluctant to get himself/herself verified may have malafide intentions.”Footnote 8 In their everyday life, servants feel the presence of the state through the institution of the police, starting with the initial process of physical verification at the police station and continuing in the constant fear that the authority of the police will be invoked by their employers.Footnote 9 The verification forms require the servants to submit information such as names, addresses, local contacts, employment history, addresses of previous employers or referees, physical description, and fingerprints. The “petwords of speech” and “favourite ditty” that are mentioned in the form are also part of the profiling exercise.Footnote 10 Start-up industries have entered the business of verification, with app-based services providing background checks on servants for a “nominal” fee.Footnote 11 Employers, on the other hand, do not need to provide such personal information as their favourite song: in this servant-centric “safety” discourse, disparity is in-built. In spite of the numerous cases of employers who have beaten, abused, raped, denying wages to, and even murdered their servants, we do not see newspaper advertisements that warn domestic servants against working in abusive households, even though these may be their workplaces. A clearly unequal relationship exists, as servants do not get to validate or verify the past conduct of their new masters and mistresses through the formal involvement of a state institution.Footnote 12

Through a study of registration in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this article underscores the linkages as well as distinctions between colonial attempts at registration and the system that exists today. The first discussions about registration took place between the 1760s and the 1810s, while the second wave picked up at the beginning of the 1860s. This remained part of an intense public discussion until the early twentieth century, and even into the postcolonial period. Owing to space constraints, this article will not go into the minute details of the second and the postcolonial phases but will only point to their chief characteristics, thereby underlining the longer trajectory of the relationship between the regulatory mechanism devised for domestic servants and the specific role of registration within it. Without arguing that there was an unchanging continuity from the colonial to the postcolonial period, efforts are made to unpack the ideology surrounding the idea of registration that emerged in different time periods. It is true that by adopting a long-term viewpoint, of more than two centuries, it appears that early colonial attempts to register servants were eventually fulfilled. However, this continuity in attempting to apply a single instrument of control (verification and registration), persisted through changing ecosystems of legal ideas around servant regulation. Although active discussion on registration in different phases might present the idea of a linear progression, it is important to stress that there were two different ideological approaches towards regulating domestic servants over this period. We should not simplistically assume a linearity in the will of the state to establish control over servants. In the first phase, registration was discussed as part of the broader legal framework of master–servant regulations; in the second, it was discussed as a proxy to regulation. In the intervening period of the 1810s to the 1850s, in which the regulation of domestic servants in the Bengal presidency stabilized under Regulation VII of 1819, there were no demands for registering domestic servants.

Why was registration deemed so important by certain actors in the colonial state and the colonizer society at large? Is there a link between the ways in which the idea of registration was expressed in colonial times and the practices that subsequently emerged even when the ecosystem of labour control had ideologically shifted, not just for labour in general but specifically for domestic servants? There is a long history of registration and verification, which continued even when the landscape of labour regulation underwent substantial changes from master–servant regulations to employer–employee contracts, then to protective labour laws, and finally to demands made for the formalization of informal work. The meaning and purposes of registration changed in each of these labour-organizing legal frameworks. While laying out these changes, this article argues that within the changing regimes of labour regulation the policing of domestic servants has remained a key element. It is not just a similarity of approach that exists independently in different time periods, but it is a linkage that connects the past with the present. This is explained in the following section, which situates one specific tool of control, that is registration, within the larger logic of regulation that is adopted and envisioned for domestic servants. In a nutshell, it can be stated here that the history of registration shows how the same instrument, imagined in the past as a formal mechanism operating under the law, came to serve a similar purpose subsequently when it operated under the shadow of the law thanks to the active involvement of the police. While demonstrating this, the article argues that the persistent presence of policing, either as a real or perceived threat, in the lives of servants is part of the colonial legal legacy.

However, regarding the issue of dependence on servants and the legal provisions that tried to define this, there is a contrast between the past and the present. While for some colonialists such a dependence heightened the need for formal regulation, for servant-keeping Indian middle classes today, such a dependence (couched in terms of kin-like relationships) militates against regulation. Why so? In order to understand this, we need to identify the place of the domestic servant in the larger corpus of regulative mechanisms that were devised for labour. This is not an incremental history in which regulation gradually accumulated, but one of sharp shifts and turns that created confusing structures of inclusion and exclusion.

REGISTRATION AND THE “LOGICS” OF REGULATION

Today's attempts at regulation are driven by those sections of the society and policymakers who empathize with domestic servants, particularly female workers, for putting up with abuses and exploitation, which are recurrently reported in national media.Footnote 13 Domestic workers’ associations also play a crucial role. The most recent bill (which failed to become an Act) was introduced in the Indian Parliament in 2017, in which the District and State Boards, representing the government, employers, and domestic workers, were the main stipulated local bodies to implement “decent conditions of work”.Footnote 14 A Central Advisory Committee, comprising member non-governmental organizations, trade associations or unions, and individuals with expertise and experience in issues related to labour, women, and children, was envisaged to oversee the implementation of the Act. Clearly, the intention was to provide security and benefits for servants, and to put in place some transparent structures of accountability.

Domestic servants have remained excluded from “protection under the Industrial Disputes Act [1947] as well as legislations on health and safety and compensation for workplace injury” made between the 1920s and the 1950s.Footnote 15 Since 2000, through different Acts, domestic servants have gained access to certain legal frameworks that allow them to complain about mental, physical, and sexual harassment from their employers, but they still do not have the right to complain as workers. Therefore, the current demand for formalization of work is for according the status of worker. The resistance to grant this is reflected in servants’ discriminatory inclusion in certain social security acts such as the Employees’ State Insurance Scheme and the uneven applicability of the Minimum Wages Act.Footnote 16 There has been a long history of reluctance and failure: since independence in 1947, seventeen attempts have been made to formalize this workforce without any significant success.Footnote 17 This phase has been characterized by scholars as “absence of regulation”.Footnote 18 It is important to remember, as noted previously, that the practice of police verification not only thrives but is also encouraged in this phase of protective “legal absence”. The servant is perceived as a potential criminal, and the ability to mobilize state resources, primarily those of the police, resides more with the employer than with the employee class.Footnote 19 It is possible to think of this development as deliberately obliterating the labour question by subsuming the work identity of domestics in that of potential criminals.

Colonial attempts at regulation emerged from a narrow and limited concern to find ways in which the European view of “rogue” and “lazy” native servants could be mitigated.Footnote 20 The guiding principle was master–servant regulation, the essence of which was that a servant could be criminally prosecuted for a breach of contract, while the master, on the other hand, could only be fined if found guilty of ill-treatment or wage arrears. Under this principle, the first regulation was introduced in 1759, in Calcutta, and was reiterated subsequently in a set of orders (1760, 1766, 1774), followed by Calcutta by-laws in 1814 and 1816, and finally turned into a regulation in 1819 that was applicable to the whole of the Bengal presidency. A similar pattern was to be found in the Madras presidency, although at the beginning of this phase (1760s–1800s) the role of caste headmen in regulating and registering servants in Madras seems to have been much more pronounced than evidence from Bengal suggests.Footnote 21 Also in Bombay, by the turn of the century, definite rules about registering servants with the police were promulgated. As a sitting magistrate, the superintendent of the police was authorized to hold in custody and punish all servants who failed to abide by these rules.Footnote 22 In all three presidency towns of Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, the colonial regulations passed between the 1750s/60s and the 1800s were exclusively meant for European households (and households of “Christian” denomination). Technically, Indian households were outside the purview of the regulatory mechanism. This should not be misconstrued as being kept outside the ambit of the law itself. Through the regulations on slavery, child infanticide, abortion, women abduction, and later sati, the Indian household was also subject to colonial legislation in this period between the 1750s and the 1850s.Footnote 23 Also, Regulation VII of 1819, the first pan-Bengal presidency regulation on domestic servants, was technically applicable to households of all types. Similarly, the 1814 regulation of the Bombay presidency applied to household servants, palanquin bearers, and hammals (a specific category of servant local to Bombay) whether employed in either European or Indian households.Footnote 24 The “Police Regulations” of 1811 in Madras, which drew their essence from the English master–servant laws, also seem to have been applicable to the whole of the Madras population.Footnote 25

The idea of registering servants in the first phase (1760s–1810s) emerged as an intrinsic part of the active master–servant law-making exercise. It was initially tied to the measures that established control over labour, and gradually expanded in scope to control crime in the city in which servants were seen to be either directly involved or indirectly conspiring. It is not surprising, therefore, that, until the Regulation VII of 1819 was repealed in 1861, we barely have any evidence of demand for registering servants. This regulation did not contain any provision for registration because the criminalization of breach of contract apparently successfully established control over the workforce, including domestic servants. The need for registration as an added tool of control was probably not felt.

Within a year of the repeal of Regulation VII, in 1862–1863, demands arose either to bring it back or to extend the clauses of other laws that dealt with the breach of contract (the 1859 Workmen Breach of Contract Act and the 1862 Indian Penal Code) to enable masters to criminally prosecute workmen. The discussion was intense, but views were sharply divided. Many officials whose opinion on the matter was sought advised keeping domestic servants out of the broadened ambit of the law, if it was going to be extended at all. Domestic servants remained outside the remit of the 1859 Workmen Breach of Contract Act. Moreover, in the Indian Penal Code only three types of servants (or rather services) were included under the criminal breach of contract provision: these were those involved with travel (palanquin bearers and seamen) and care (ayahs).

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, a shift was discernible in the state's opinion on regulating domestic servants. A law that would criminally prosecute breaches committed by servants was increasingly seen as a tool that would aid “bad” masters and mistresses. As Nitin Varma shows in his as of yet unpublished research into the Master-Servant Law and domestic servants in colonial India, the government instead decided to explore the possibility of bringing the master–servant relationship under civil contract legislation, although, as he shows, the lasting shadow of the criminal breach of contract pervaded the script of that bill as well (1877–1878). This, too, failed to become an Act. From this point, at least until the 1920s, various bills were introduced at provincial level to regulate and register domestic servants, but none of them was enacted. Factory Acts emerged from the 1880s, and from the early twentieth century the density of what are now called “protective labour laws” began to grow.Footnote 26 Industrial labour became the subject of protective legislation and domestic servants continued to recede into the “unregulated” zone within the precincts of the household. In terms of the legal regulation of domestic work, this was the period when domestic servants were written out of the script of the law and the category of labour. From being included in the master–servant regulations of the first half of the century, they became “unregulated” by the end of the nineteenth century. Since the 1950s, attempts have been made to bring them under the law's protective umbrella and assign them the status of worker, but this has not succeeded.

While this shift was taking place, attempts to register servants continued, but their ideological cast had changed. This can be traced at a legal level and in the space of the “reformed” household, both British and Indian. If in the first phase the idea of registration had emerged as an intrinsic part of the master–servant regulations, in the second phase (1860s–1900s) that idea developed in spite of it. Registration developed as a proxy to any formal set of rules; in other words, it drew strength from the absence of regulation.

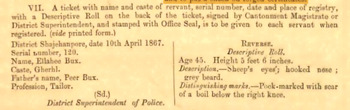

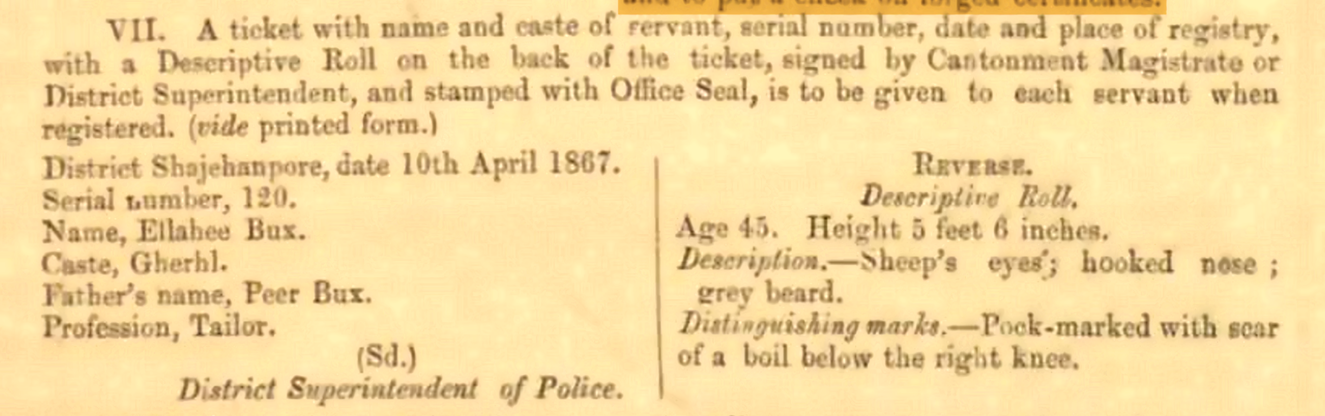

We have noticed how the repeal of Regulation VII of 1819 in 1861 created a virtual panic among European authorities and householders. For instance, the commissioner of Patna described it as causing the “effect of reducing all masters into a state of helpless bondage to their so called servants and workmen”.Footnote 27 However, in spite of views such as this from various districts, the Bengal government did not address the matter of domestic servants and favoured the extension of the 1859 Workmen Breach of Contract Act into rural areas only for “workmen”.Footnote 28 However, in April 1867, a system of registration of domestic servants came into force under the police in the North-Western Provinces. In almost a year, more than 5,000 servants were registered in different places across the region, in cities such as Allahabad and Benares. It was reported that “servants were voluntarily coming in such numbers to the Office of the District Superintendent [of Police]”.Footnote 29 The intended purpose of this system was to allow the police to protect masters from “domestic pilferers”. The police maintained a register that included the name of the servant, nature of service, date and place of original and current registration (in case the servant had moved places and jobs), and the date of and reason for discharge. A ticket was given to the servant with details of name, place, caste, father's name, profession, age, physical description, and distinguishing marks (such as pockmarks) noted. This appears not so different from the police verification form used today. The Police Registry Office was also a repository for discharge certificates, and masters were allowed to consult the Register after the payment of a fee to check the “conduct” of servants at their previous place of employment (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. A snippet from the NWP police registration provision.

GOB, HD, PB, July 1868, nos 81–83, NAI.

Figure 3. Part of the police verification form.

http://www.delhipolice.nic.in/home/servant-f.htm ; last accessed 19 October 2021.

The Bengal authorities, however, rejected the implementation of any such plan or other legislation concerning compulsory registration. One severe point of criticism they raised was that this would allow the police to interfere in matters “with which they have no concern”, and that it would “invite a system of exparte accusation, highly objectionable in itself and unjust to servants”.Footnote 30 It reasoned that, “as a rule, […] a good master will certainly never have any difficulty here in finding good servants without applying to the Registry office”.Footnote 31 This signalled a change in the legal ideology since Phase I. The state was reluctant to legislate directly about domestic servants or even to continue penal provision for breach of contract because it leaned towards the argument that such a law would help bad employers rather than the good ones.

Nonetheless, the Bengal government's reluctance to legislate on registration did not end the demands for it. In the 1890s, the issue of registration was again discussed among members of different departments – home, legal, and military – in terms of legal exceptionalism. This demand considered making registration compulsory for servants who were working in cantonments and hill towns. The government opinion of the futility of such a law did not change, but they half-heartedly consented that registration as a device that would allow employers to better control their servants was “desirable” for some places.Footnote 32 While the government denied aiming to formally institutionalize the practice of registration, it did leave a window open by saying that it could be carried out by “voluntary” efforts.Footnote 33 In 1903, the Punjab government presented a bill for “the exclusion of bad characters from the hill stations in the Punjab” using police registration.Footnote 34 The provincial government made an unambiguous connection between domestic servants and bad characters, and imputed the former with criminal identities. The central government took strong objection to this, calling the proposal a “piece of class legislation” that attempted to portray servants as a “criminal tribe”. Later, when the matter was discussed in the Punjab in 1908, the majority opinion was in favour of directly legislating on expelling servants from the hill towns of Simla and Dalhousie on the basis of “misbehaviour” or “serious misconduct”.Footnote 35 Again, opposing voices reasoned that this would lead to a grave abuse of law, and it was also described as illegal: “We cannot admit that a servant who is lazy or impertinent or disobedient should ipso facto be liable to deportation from a hill station.”

In contrast to the first phase, in the second phase (1860s–1920s) there was an ideological shift in the utility of the law that controlled servants. The idea of formal criminal regulation was firmly dropped by the government. However, in order to overcome this absence, demands that were made by European associations, trade associations, provincial governments, military officials, and hill station municipal bodies hinged on the system of police registration. If servants could be forced to register with the police, it was thought they could be better controlled. The repeal of Regulation VII of 1819 was thought to be partially reversed by this method of verification and expulsion. In the 1900s, during debates that took place in Punjab, it was reasoned that if a definite system of registration be introduced – with provisions for fines for those servants who were working without a licence – it would possibly meet requirements “without the necessity of expulsion”.Footnote 36 In 1883, the Darjeeling Porters and Dandeewallahs Act was introduced with penal provisions for porters and bearers in public service.Footnote 37 The highest governing authority, the secretary of state, assented to this only on the condition that it would not be applied to porters in private service and domestic servants. In the report on the working of the Act in 1885, the local administration made the assurance that in not a single instance was the penal provision implemented, but the “mere existence of power” “sufficed to reform the Darjeeling dandeewallahs”. However, bearers who were charged of misconduct were not allowed to become domestic servants, thus suggesting that the power was indirectly used to regulate the domestic labour market.

Wavering between the decision to legislate a master–servant law (whether criminal or civil regulation of contract) or instead to allow concession for some form of registration existing at voluntary, localized levels, the state created islands of legal exceptionalism but without the express sanction of the law. As a result, registration seems to have materialized in some places. In rejecting the proposal of the Imperial Anglo-Indian Association in 1899 for registration of domestic servants in Calcutta, the Bengal government sympathized with the cause, and suggested that “European masters in Calcutta should assist themselves as in England, by promoting registering offices from which employers could entertain domestic servants with some scrutiny as to their previous character”.Footnote 38 Writing in the same year, Alban Wilson, a military officer, said: “Registry Offices for servants are now started in most of the large Indian towns […] The man has to then sign an agreement to serve you for a certain period at a certain wage, and is thus made liable to be punished if he breaks it.”Footnote 39 Clearly, registration was not only meant to control perceived criminality but also to insert police power into regulating work and wage-related disputes. A little later, Steel and Gardiner mentioned a registry office for servants that was kept by deaconesses in Lahore.Footnote 40 Again, in rejecting the proposal in 1904, the Bengal government asked the Imperial Anglo-Indian Association to “stimulate the establishment of voluntary registration offices”.Footnote 41

Developments in this period (1860s–1920s) deserve a specific inquiry, and this is beyond the scope of this article; but the NWP measures of the 1860s, recurrent demands made by European associations for the registration of servants, the favourable approach of the military department towards this by suggesting the incorporation of compulsory registration in cantonment rules, and the government's own half-hearted acceptance of its utility for certain places such as Simla and Dalhousie, where old and infirm European widows and children were allegedly at the mercy of “rogue” servants, suggest that in this phase the police or municipal registration of servants emerged as a proxy to formal legislation. Even voluntary efforts to register servants, it appears, created a sense of security among masters, as they could rely on the power of the police to get servants punished if need be.

These developments brought the identity of the servant closer to the practice of alleged theft and crime. The servant was recast in the image of a potential criminal, and hence policing through registration was promoted by different sections of colonial society (if not directly by the colonial state) as an important tool to control them. Time and again, the government itself accepted that masters framed the charge of theft when servants demanded their legitimate wage arrears. In 1878, the Lucknow magistrate reported that: “I can remember several cases in which a pretended theft has been reported in order to do servants out of their pay.”Footnote 42 The problem of translation-based miscommunication and “unreasonable” orders given on the part of masters and mistresses was highlighted in 1903:

To call in the Magistrates and the police to decide whether a servant has or has not “seriously misbehaved himself” when he is charged with insolence by a mistress who understands his language imperfectly and may have herself given impossible or unreasonable orders, certainly seems to be an impossible arrangement.Footnote 43

In the discussion on the Domestic Servants Bill in 1959, a member of parliament pointed out that numerous examples abounded in Delhi of masters framing the charge of theft when servants asked for their unpaid wages.Footnote 44 Masters wanted an easy recourse to discipline, and the use of the police was ideal. In the absence of formal legislation on the master–servant relationship, the charge of criminality was generalized so that servants’ legitimate grievances related to work and wage disputes could easily be turned into charges of crime, which could be punished by the police.

Following strong opinions expressed by Thomas B. Macaulay in his draft code, in which he resisted the idea of putting domestic servants under the charge of criminal prosecution for breach of contract, the implementation of his draft code as the Indian Penal Code in 1862, together with the annulment of Regulation VII of 1819, marked a shift in the state's approach. The master–servant relationship legally began to be viewed as a “private” arrangement. This change, which came about after 1861–1862, was also reinforced by new norms of domesticity. An ideological shift in the conceptualization of British homes in the colony was under way. This was marked and established by the prolific publication of household management guidebooks, which initiated the process of “privatization of authority”. A number of these manuals commented on the absence of formal law to regulate servants, and hence proposed ways in which their readers could become good masters and mistresses for child-like Indian servants.Footnote 45 While these “cultural” texts elaborated on ways to become good masters and mistresses, the legal reasoning that developed to reject any need for formal regulation stressed the fact that a good master would never suffer from bad servants. The alleged legal vacuum was thus intended to be filled with a mix of sternness and benevolence. The force of the police, though not officially clearly sanctioned, was used in order to maintain authority within the household when required.

Scholars working on the contemporary period often give the impression that the features of paid domestic work and the absence of regulation are unrelated to the past.Footnote 46 They contend that the past is present but only through social and cultural idioms of caste, work, other notions of discrimination, and patriarchy, which constitute the “feudal imaginaries” of modern times.Footnote 47 For instance, the extremely rich and textured ethnography of Ray and Qayum claims to show the “historical rootedness” of domestic service but, in an attempt to do so, unwittingly straightens out the past. The problem is not so much with the use of labels such as “feudal” and “modern”. While all periods come to be seen as containing a set of values from which the ensuing one distinguishes itself, difficulties arise when such articulations overlook the connections between ideological shifts that occur over a period of time. What appears as static and feudal from the vantage point of the twentieth century was in reality a period of highly dynamic meaning- and boundary-making, in which law played a significant role. The contemporary absence of regulation cannot be comprehended without understanding how the processes of privatization of authority unfolded. That this privatization went hand in hand with an intense demand for servants to be registered by the police and municipal authorities reminds us that the mechanism of state sanction was not seen in antithesis to private authority.

The ideological base of the privatization of authority needs to be probed further. Was it just emerging from the changed notions of respectability that were propounded by Victorian ethics of domestic life or was it also (and most probably it was) linked to the imagination of who the “worker” was, as a debate about this and the divided spatialities of the public and the private, factory and home took shape. These are some of the questions that require future research. The nature of the trajectory is clearer than the process itself: it was the lasting effect of the internalization of this ideological baggage – that servants could better be managed if masters behaved well – that created a sanctimonious cushion around the inviolability of the household from external forces such as the law. And at the same time, the absence was filled with the practice of masters who used the power of the police when servants required to be “corrected”. It requires further research to ascertain the extent of this police intervention: was it largely limited to the perceived criminality of the servant or also to wage and work disputes? In the case of servants, because of their unique position as household workers, it was nevertheless often the practice, as accepted by state functionaries and noted above, that masters turned disputes related to work and wages into allegations of theft. It is very likely that late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century practices laid the ground for employers’ antipathy today towards the formalization of domestic work. So, to recap our arguments so far: between the 1860s and the present day, we see a twin process unfolding: that of the privatization of authority on the one hand and the absence of a formal legal mechanism on the other. This was, nonetheless, accompanied by a growing emphasis on the use of alternative formality, which was based upon the ideas and practices of identification, verification, and registration. These processes of formal absence and alternative formality were interconnected. It was through the connecting logics of inclusion and exclusion, based upon the changing ideologies of social organization, domesticity, and the function of the law that the “absence” was created owing to an active decision on the part of the state.Footnote 48 And at the same time, an attempt was made to fill the absence through the use of another punitive authority of the state, the police.

The above argument, even if it sounds convincing, is incomplete. There is a strong need to qualify this picture. The phrase “absence of regulation” is prone to create a false impression of an ideal informality that existed between masters/employers and servants/employees. It opens room for an interpretation that because there were/are no regulations, masters were/are able to apply disproportionate power and control over their servants. Both these readings would prove to be incorrect if we agree that this absence or informality also needs to be historicized. A question then emerges about the historical genealogy of masters’ confidence in the use of disproportionate power. In a recent incident at the Moderne Mahuguna Society, in Noida, related to a dispute between a maid and her employer, why did the police destroy servants’ tenements whereas the masters’/mistresses’ were undamaged?Footnote 49 Embedded in the ideological setting of “absence”, the practice of active policing is present. In order to understand the historical role of policing, we need to make another genealogical journey, this time into the late eighteenth century. This was the period when for the first time, owing to the design of master–servant regulations as well as the colonial administrative and judicial set-up, the presence of the police became a force in governing the master–servant relationship. In this phase, registration was actively discussed as a part of a regulative mechanism, and not as a proxy for other regulations. Through a focus on specific parts of the registration debate, the remainder of this article shows how policing gained currency. It also shows that the intense demand for police-based registration that arose in the second half of the nineteenth century was built upon events in the eighteenth century, something that is little known in our historiography.

REGISTRATION AND POLICING IN EARLY COLONIAL MASTER–SERVANT REGULATIONS

Beginning in 1759 in Calcutta, in very quick succession, wage lists were prepared, plans of control were drawn up, and proposals were floated, albeit unsuccessfully, to make by-laws. The focus, as outlined in the 1759 order, was on fixing the wages of servants and their terms of service and punishment – criminal prosecution for servants and fines for the masters – instituted by the Court of Zemindary, which had been established in Calcutta in 1700.Footnote 50 The only surviving volume of proceedings from this court from 1766 shows that European masters frequently sent their servants there on charges that they had demanded higher wages, neglected their duties, breached contracts, absconded, or stolen, for which they were fined, flogged, or punished with “hard labour”.Footnote 51 With minor changes in wages for some servant categories, another resolution was passed in March 1760; and then in 1766, a third resolution came into force. This was the first time when the proposal to establish a “Register of all servants of every denomination in Calcutta” was made. A detailed account of wage-related initiatives has been provided elsewhere; therefore, this article focuses only on discussions related to registration.Footnote 52

Soon, a registry office was established with two officials who worked under the Zemindar (the head of the Court of Zemindary).Footnote 53 They were directed to report before the governing board every Monday morning, which indicates the importance the colonial government attached to this project.Footnote 54 However, in more than one year, very few European inhabitants registered their servants; no Armenians and Portuguese did so. The two officials were removed from Calcutta and their offices fell vacant.Footnote 55

During this period, similar structures of control were put in place for different labouring and service groups, servants being just one. Also in 1766, orders were passed for artificers, bricklayers, carpenters, smiths, sawyers, and other craft workers to have their names registered immediately or to be “severely punished and turned out of the settlement”.Footnote 56 Shopkeepers and dealers were also asked to register themselves.Footnote 57 A few years later, silversmiths complained that registration had affected their business.Footnote 58 The fortification work that had started in Calcutta in 1757 and lasted until 1775 intensified control over a variety of working groups.Footnote 59 Other public works also suffered from a shortage of labour or from workers demanding wages higher than the Company was willing to pay. The construction of new buildings was therefore restricted and those under construction, together with all workmen employed, had to be registered; and the unregistered had to be “seized for the service of the publick works”.Footnote 60 The similar approach adopted towards the diverse body of waged labouring population attests to the fact that domestic servants were a formal and integral part of the master–servant regulations in colonial India. The formative period of colonial state formation was geared towards finding ways to deal with labouring groups of both varieties: public (transport, building, and construction were prominent sectors) and those hired to work at home.

This regime of registration had to serve several functions. Based on the idea of identification, it was supposed to individually identify workers and make them accountable for criminal prosecution, if necessary. A certificate containing name, employment, and the number that each worker was assigned had to be maintained in the register. Those who were found to be working without such a certificate were punished, and were subject to forced labour.Footnote 61 Such was the fervour for registration that when complaints were made against European tailors for charging dearly, and the tailors passed the blame of high cost on their journeymen, the committee ordered that all journeymen should be registered and their wages reduced as much as possible.Footnote 62 The alleged extravagant use of palanquins by “upstart natives” also caused an alarm; the remedy, once again, was to register the use of palanquins.Footnote 63 In a period when the colonial state was attuned to understanding Indian society through the prism of collectives such as religion and caste, the individualized entity of the worker being entered as a subject in a registry book points to the fact that categorization and classification undergirded the ideology of colonialism not just in its later phase (as scholars usually identify the second half of the nineteenth century). Even at the beginning of colonial rule, often described as a time when power was heavily limited and circumscribed by local Indian conditions, the colonial state believed in the power of its own constructed classificatory “papereality”.Footnote 64 Raman uses this word in relation to the practices of writing that aimed to make the bureaucratic power of the state appear accountable and legible; it thus gave prominence to a technical and standardized procedural governmentality for the state. My use of the word is on a much smaller scale, suggesting that the widespread desire for the registration of labouring bodies as individuals (through collective categories such as coolies, workmen, and servants) points to the very early primacy that the colonial state gave to the production and maintenance of verifiable records of individuals whose labour had a bearing on the everyday functioning of both the colonial state and European households.

The initial idea of registering domestic servants worked within the logic of labour regulations: wage control, control of labour supply, and clarifying the terms of service and punishment. Registration was designed as an instrument of labour control. It was seen as an integral part of master–servant regulations and did not exist outside it. The impulse to register did not die down after the fortification work had begun to slow. In a subsequent order of 1774, the government instructed that a superintendent of the police (SP) should be appointed as deputy to the Zemindar, in order to receive the complaints of “Christian inhabitants” against their hired servants and slaves, and punish them, when convicted, by whipping, imprisonment, and hard labour.Footnote 65 The same order also reiterated the need for maintaining a register of servants, but now under the SP.Footnote 66 The scheme involved the payment of one anna (pice) by the master for every servant so enrolled. Preference in dealing with complaints was to be given to those who had registered their servants. The police would do their utmost to apprehend servants who had fled from their duties. Servants had to report complaints against their masters to the Zemindar or the Justices of the Peace (JPs).

Institutionally, this was a clear shift, as were the changes that were made at the same time within the existing judicial administration that seem to have enhanced police powers. In 1772, Warren Hastings introduced judicial reforms to create a well-defined system of criminal (foujdary) and civil (diwany) courts. Owing to frequent complaints made by European masters in the foujdary court that impeded its business, the 1774 order forbade masters and ships’ captains from bringing matters related to slaves, servants, and lascars to the court. According to the 1759 order, the Court of Zemindary had dealt with disputes related to the master–servant relationship up to this point. However, contemporary sources indicate that the Court of Zemindary ceased to operate in around 1772.Footnote 67 With its abolition, the SP became an independent authority. Before coming to the history of the office of the SP, which caused a rift within the justice administration of Calcutta, it is important to highlight how the institutional landscape of justice created limited access for servants’ grievance redressal. In Calcutta until 1793, the members of the governor general in council and the judges of the Supreme Court were the only officials who acted as JPs.Footnote 68 The place to which servants could take their grievances, particularly as related to ill-treatment, was the court of quarter sessions, which had been established in 1726. The sittings of this court, presided over by the governor general and his council as JPs, took place very irregularly: records suggest, indeed, that after the early 1770s, the court did not sit until the beginning of the nineteenth century.Footnote 69 For the recovery of wage arrears, servants had recourse to the court of requests (established in 1753), whose volumes of proceeding have yet to be rediscovered. But stray references, particularly from the early nineteenth century, suggest that servants did take their masters to court for recovery of their wages, although the money value of the suit that this court could entertain was fixed approximately at Rs 18, which increased to Rs 80 in 1797 and Rs 400 in 1800.Footnote 70

In this context of judicial overhauling, the most likely scenario that seems to have existed is that masters had access to the police so they could bring complaints pertaining to servants’ “fleeing away from the duty” – to use the wordings of the 1774 order – but servants had relatively limited access for redressal of their grievances, particularly beating, ill-treatment, and undue firing. “Fleeing away from the duty” juridically translated into the charges of “neglect of duty”, “absence without notice”, or “absconding without fulfilment of the task” – the three direct complaints that constituted breach of contract. As I have shown elsewhere, masters brought their servants to courts under these charges.Footnote 71 Thus, this institutional reorganization of justice did two things: first, it created a disproportionate level of access to justice for grievance redressal, as masters could go to the police but servants, for all grievances other than the recovery of wage arrears, were required to approach the JPs, who met irregularly or not at all; and secondly, this arrangement put the resolution of everyday master–servant disputes into the hands of the police. The patchy source material related to the actual working of the law from this period shows that the police worked as the Court of Zemindary had functioned in the past. The process of justice was summary. On comparing the 1766 Court of Zemindary with an extract of Charles Playdell's charge sheet from 1778 (he was the SP at that time), we find a similar kind of punishment meted out by both authorities.Footnote 72 The cases clearly show that it was not only charges of theft but also matters integral to the master–servant relationship, wage and work disputes, in which the police gave summary decisions.

The late eighteenth century was a period of administrative flux: rules and institutions were made and dissolved in quick succession. The state projected its power more than it actually wielded it. However, the acquisition of quasi-judicial power by the police to regulate the master–servant relationship took place in the shadow of the law, and not outside it. When Alexander Macrabie, the brother-in-law of Philip Francis, who was second in command to governor general Hastings in terms of power and authority, was appointed SP in 1774, he was granted the power of summary prosecution. This was justified by Hastings through the language of legal exceptionality:Footnote 73 he agreed that summary power for the police was against the laws of England but was deemed necessary for a place such as Bengal, at least for some years. Macrabie was succeeded by one John Mills and soon by Charles Playdell. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court had expressed its displeasure at “irregularities” in the office of the SP, and they charged the officer with exercising “a most illegal and Oppressive power over the Native inhabitants”.Footnote 74 No royal charter or Acts of Parliament, including the one from 1773 (and previously of 1753), had sanctioned the office of the SP. In spite of harbouring the belief that Indians needed to be ruled according to their customs and institutions, Hastings had a strong opinion on the necessity of bending English laws to suit the colonial needs; so the arbitrariness in legal exceptionalism was inbuilt to the logic of the law, as it developed as a specific form of rule in the colony. All three appointments were made by Hastings under a personalized form of law that was based upon his decision and assessment of what was required for “good order” (there was no legal position for the magistrate/JP). In 1778, subsequent to the criticism of the Supreme Court, a rule for better management of the police was drawn up. This rule gave the superintendent, Playdell, the authority to examine all persons rounded up during the night vigil by his Indian subordinates, which included “all servants and workmen charged with misbehaviour, & c”.Footnote 75 In cases of high crimes, such as treason and murder, the accused person and the relevant depositions had to be sent to the JPs, but otherwise the superintendent was allowed to use “personal Jurisdiction over petty Larcenies, & c”.Footnote 76 This rule was invalidated by the British Parliament in 1780, but the order reached the Supreme Court in India only in 1783. Consequently, in 1783, another rule was drafted which constituted a commission of police, consisting of three commissioners. However, this was also quashed by the Supreme Court of Bengal on the ground that it assigned the commissioners the “exceptionable” power to whip and inflict corporal punishment.Footnote 77 A few years later, in 1788, the concern against the quasi-judicial power of the police was more strongly expressed by the Supreme Court judge William Jones. While asking to increase the number of the JPs whose “legal power is very considerable but yet accurately defined”, Jones had the following to say on the institution of the police: “but a superintendent of the police, is an officer unknown to our system, borrowed from a foreign system, or at least suggesting an idea of a foreign constitution, and his powers being dark and undefined, are those which our law most abhors”.Footnote 78

It hardly appears a coincidence that two years previously, in 1786, the Supreme Court had found the then superintendents Thomas Motte and his associate Edward Maxwell guilty of imprisoning a person overnight. The letter by the superintendents reveals the state of the office of the police:

The Honble Judges […] were bound to give judgement against them [us] according to the English law, out of the passé of which the superintendents acted yet in consideration of the peculiar situation of the police in Calcutta with which the Honble Board is well acquainted, and the impossibility of proceeding with the accuracy and the precision required by the English law, from the multiplicity of business which daily arises, and which renders a summary process absolutely necessary.Footnote 79

The letter requested the government to give the judges a formal “determinate power and authority”; “what they at present possess appears to be merely discretional”. The fact that the master–servant regulations were summarily adjudicated must not have posed a problem for Jones, as this was also the case in England. The Court of Zemindary had followed the same principle of summary jurisdiction, which was presided over by a junior member of the governor's council (and hence technically a JP). The fact that this power was now exercised by an office that had not been sanctioned by English law in the colony must have irked Jones to complain about the summary mode of justice (conviction and punishment) carried on by the “dark and undefined” power of the police in Calcutta. Even in England at this time, there was scepticism about the growing demand for “police reform”, precisely on the basis of the unconstitutionally and “foreignness” of the office.Footnote 80

Immediately after the ruling of the Supreme Court in 1783, and before the superintendents’ indictment in the case mentioned above, a two-year discussion to regulate and register servants kicked off once again. In spite of the strong views of Jones, Hastings, the governor general, asked the SP Motte to draft a plan for a by-law.Footnote 81 In March 1785, this plan was drafted. The governor general, however, changed his mind. In seeking permission from his board to approach the Supreme Court, whose consent was mandatory, he observed that the proposal, if approved, would be published as “a plan for the introduction of good order” in the settlement and not as an actual by-law.Footnote 82 Apart from producing the “absconding” servant, the plan clearly laid out the exercise of authority: “when any servant misbehaves he shall be sent to the [registry] office where he shall be punished according to his fault”.Footnote 83 The role of the JPs in adjudication was not mentioned.

A plan for compulsory registration of servants working in European households was part of the proposal. Motte treated registration as a “fair channel” that would filter the “faithful, industrious and diligent servant” from “desolate” ones entering the “worthy families”.Footnote 84 The name, quality, wage, and place of abode of servants to be hired were to be recorded in the book. According to his plan, the master would pay eight annas per servant to the registry office. Separate books for different categories of servants with an index for each was to be maintained. This was yet another imagined function of registration. Once the registration of all servants already in employment was finished, the registry office would eventually serve as the certified hiring centre. A master wanting a servant would apply to the office; he would then be delivered a servant within three days, for which he would pay one rupee as fee. Further, it was proposed that in the case of a servant absconding from work, the office would produce him – and “for each servant so produced, the person applying shall pay one rupee”. Once again, the plan suggested that the police to whom the registry office would be attached would become the authority to adjudicate work-related disputes between masters and servants.

In hindsight, it appears extremely surprising that the nascent colonial bureaucracy had put so much trust in eighteenth-century Europeans to pay a rupee each first to hire and then to retrieve an absconding servant. Europeans of all shades complained of expenses in the city. One prominent reason for regulating the wages of servants was to ease the expenses that masters incurred on hiring twenty to thirty servants. Hiring, firing, and rehiring the same servant was frequently done. Such an extra expense to keep the registry running simply would not have worked.

The fate of this plan is unclear; but meanwhile, in 1786, a second plan was drafted. Motte further honed the proposed system of registration by introducing a ticket system. On registration, each servant would receive a ticket bearing his name on the office's seal.Footnote 85 On discharge, the masters were supposed to give a discharge certificate in writing on the back of the ticket. If this was refused, the servant was supposed to report it to the office, which would inquire into the reason why the master or mistress had refused to give a certificate. The certificate, or chit as it was commonly called, was proof of a servant's good character at his previous employment, and hence worked as his/her surety for future employment through the registry office. Those convicted of stealing or any other crime had their name struck off at the registry. The convicting authority was the registry office, which was envisioned to work under the SP's charge. The mode of punishment was corporal: “the office [would] enquire into all complaints preferred against servants and […] punish delinquents, no pecuniary punishment to be admitted”.Footnote 86

In both these plans, registration was devised as a mechanism that would regulate servants’ entry into and exit from work and the labour market under the authority of the police. The fact that Motte wanted the registry office annexed to the police superintendent's office shows the blurred boundaries of justice, in which a single authority would investigate and penalize. In spite of the Supreme Court's opinion expressed in 1783, neither the government, nor the police was deterred from proposing a plan in which the functions of the police, the judge, and the court were fused into one. In this regard, it can be deduced that the registration office was imagined not only to act as the hiring centre but also as a new court of justice for dealing with the cases related to servants.

Following Motte's proposals, in 1786–1787, a general committee from among the British notables of the city was formed to give its opinion on the subject. The committee was divided in its view, and hence submitted two reports.Footnote 87 In the majority view, there were the usual clauses of criminal punishment for the breach of contract, while even the failure to procure a testimonial for last service from the registry office before entering into a new one was declared a criminal offence that would be punishable with imprisonment, whipping, and declaration of the servant as “vagabond”.

The gist of both these reports was centred around the potential abuse of power. One faction thought that the process of registration would give sweeping powers to the registry officer; therefore, it recommended the establishment of that office as an executive branch of a “committee of control”, with twelve people chosen from among the inhabitants to oversee the work of the registry officer. The plan also conferred the power on the committee to look into complaints received against the officer by servants. The judicial power to decide on disputes arising between masters and servants was vested in the registry officer (to be monitored by the committee of control); he could summon, investigate, and convict the defaulting party. In cases of dispute over any decision, the aggrieved party could go to the JPs. Later, a change in the proposal was added: the proposed committee of control was to be replaced by the commissioners of police, who were instituted by a by-law in 1784.Footnote 88 The minority dissenting group of two members also raised doubts about the possible abuse of power, this being most likely, in their opinion, to be committed by Indian subordinates in the registry office. They reasoned that these subordinates would have the freedom to distribute work selectively among registered servants who were out of work. This would put servants at the mercy of these officials and agents – which, in turn, would encourage them to bribe these officials to get new jobs rather than seek redress, thus defeating the purpose of guaranteeing servants’ honesty. Among other points, another objection came up, which resonated with the concerns that masters had in England.Footnote 89 A master hiring his servant from the registry office would not have sole control and authority over him; the registry office was seen to compromise the householder's authority.

CONCLUSIONS

The technique of registration was meant to serve households by providing good, loyal, and faithful servants. It was also designed to shape the labour market for domestic servants through blacklisting, banishment, and other forms of criminal punishment to unwanted, undesired ones. The ideational foundation of this legal intervention linked, rather than severed, the ties between the home and the market. It also attempted to insert the police as a judicial authority. An argument that is currently provisional is whether the stigmatized notion of domestic worker – being inherently of a criminal propensity – who was placed at the cusp of the household and the market was a product of policing-based ideas around these attempted legal interventions. It is provisional because in order to make such a case, which imputes a significant amount of agency to putative colonial forms of intervention, one needs to thoroughly sift through various forms of stigmatized depictions of servants that persisted from precolonial times into the colonial era. For instance, in the literature dealing with ethics in the Mughal period, it is noted that masters were advised to check the moral behaviour and character of servants before hiring them. If this was not possible, physiognomy was to be observed: servants with physical deformities who appeared shrewd and cunning were to be avoided.Footnote 90 While servants ideally had to be judged in this way (indicating the presence of the stigma of physical deformity), service itself did not carry a social stigma.Footnote 91 In colonial times, distrust for natives as a default mode of encounter and engagement definitely solidified. In this realm, the perception that a native worker was inherently disinclined to observe a contract or that servants in particular were prone to run away, neglect their work, and commit crime and theft was attributed to the character of the “native”. Going by the space that domestic servants occupied in discussions on law as well as in the pages of diaries and letters of Europeans living in India in which servants appeared as their “intimate other”, it can be argued that servants literally embodied the colonial difference on an everyday basis. In that process, they were typecast as “thieves” and “rogues”. As a result, servants were “cheats” unless otherwise proven – a belief that is widespread in the present day as well.Footnote 92 None other than Motte pronounced to the governor general that: “It is universally acknowledged, that almost all robberies [in Calcutta] are perpetuated by the aid and connivance of servants.”Footnote 93

The extent to which the power of papereality translated into reality is extremely difficult to ascertain but not impossible to gauge. The ambitious plan to document, classify, and categorize colonial labouring groups needed to be tempered with the institutional reach of the state, which was nascent in this phase. The exhaustive sixty-two-clause draft prepared by the general committee discussed above failed to become a by-law. We don't know exactly why it did not become a piece of legislation, but informed guesses can be made. First, the Supreme Court might have disallowed the emergence of a new official entity, the registry officer, with quasi-judicial powers – as indicated by its line of thinking when it earlier struck down the 1783 proposal. Jones's negative feelings about the office of the SP also points us in this direction. Secondly, the cost of registration must have deterred the European masters. A well-to-do European household normally employed twenty to thirty servants. A fee for hiring and then a fee for finding an absconding servant would have appeared excessive. There was also a regular complaint that servants demanded excessive wages. As a result, wage lists were prepared between 1759 and the 1780s. It is difficult to imagine that while they were complaining of high wages prevalent in the city, the masters would have further voluntarily incurred an extra pecuniary burden in getting their servants registered. The constraint on the law becoming a reality was thus enshrined in its own idealism. Thirdly, as mentioned in passing in debates that took place on the last proposal discussed above, the plan could have chiselled away the householder's authority, and hence in all likelihood would not have been favoured by the masters. This is the least likely reason for the failure, however, because with the lack of perceived “customary” and social means of discipline (through caste authority, for instance), the Europeans were not shy of using the law to control their servants. With servants, though, there was an element of legally, socially, and philosophically approved “private” authority as well; if necessary, servants could be “mildly” corrected by their masters privately. This private authority was duly recognized and promoted by contemporary legal thinking and practice.Footnote 94 In the late eighteenth century, had the European masters been convinced that registration would provide them a better and more economical mode of control over servants, they would have opted for it.

Were these plans and measures, some adopted and others proposed, mere “paper resolutions”, as James Long characterized them in the 1860s?Footnote 95 Does the lack of proof of a regular registry office suggest that the sentiment, and even practice, of registration never took hold in colonial Calcutta? In the case of Canada, Paul Craven points to the symbolic value of the master–servant regulations even if they failed to comprehensively regulate the reality on the ground.Footnote 96 In the case of Calcutta, this also seems to be true. Between 1759 and 1772–1773, the Court of Zemindary directly presided over master–servant regulations. This court had its legality drawn from the Mughal firman (grant) and not English law. But the court applied the principles of the master–servant regulations from English experience. The colonial government clearly mixed two things to create an optimum situation for imposing control over servants: it borrowed the principles of these regulations from the home country but placed its adjudication in the perceived Mughal system of summary justice (which also was the case in Britain at this point). Between 1772–1773 and the mid-1790s, the regulation of master–servant disputes arising from work breaches (not just crime) was most likely conducted by the “dark and undefined power” of the police, as Jones remonstrated. Only in instances of high crime such as beating, leading to the death of the servant, would the case move up to the JPs or the Supreme Court. “Misdemeanour”, “misbehaviour”, and “larceny” were often the categories used for describing servants’ faults. Practically, they would have remained within the purview of the personal jurisdiction of the police, as enshrined in the 1778 rule, which was repealed in 1783.Footnote 97 Formally, the office of superintendent of police was created as late as 1808.Footnote 98 In 1793, the power of the magistrate was enlarged to try petty offences and crime, and also to inflict limited corporal punishment. The same year the government was allowed to appoint more JPs, if required. In 1800, to improve the condition of the police in Calcutta, JPs were appointed.Footnote 99 It is very likely that from then on, the SP would have officially become a JP. However, by the turn of the century, owing to the growing legal chasm as well as the alleged increase in the magnitude of the “servant problem”, the police-based system was perhaps found inadequate, and therefore once again attempts were made to institute a by-law, which finally materialized in 1814 and 1816.Footnote 100 These by-laws and the subsequent Regulation VII of 1819 did not mention registration. Between 1759 and 1814, however, registration remained a key element of the emerging structure of regulation that was aimed to shape the labour market for domestics at multiple levels: wage demand, regulation of entry and exit by individual identification, maintenance of a record of employment history, blacklisting and imprisonment, and not least the control of crime.

Even when the proposed measures had failed to turn into a by-law in the mid-1780s, the sentiment of registration prevailed. In July 1794, one R. Nowland, on being “encouraged by his friends”, opened a registration office with the objective to ensure “good behaviour and honesty of servants”.Footnote 101 Lascars and hackeries (a two wheeled carriage drawn by bullocks) were also included in the plan. The process of registration had to follow the “regulations”, which were allegedly “numerous” – they were all displayed in the office in English, Persian, and Bengali. We only have references to the use of these numerous regulations and not their actual content. It is probable that, without active state sanction, these quasi-regulative regulations developed out of some of the steps that were discussed in the 1780s; but indirect state encouragement cannot be ruled out either. In rejecting the 1786 plan, the Board stated that the wages of servants should be regulated by inhabitants at large, but the latter “may appoint a Committee to prepare and form a plan for that purpose, which the Honourable Board will be very glad to receive and take into consideration”.Footnote 102 So far, no subsequent discussion on the divided reports of the general committee that were submitted to the government has been found in my research. But because the framing of the by-law had to wait for another two decades, it cannot be ruled out that Nowland's registration office might have involved the authority of the police. After all, it was put in public domain by advertisements that the police office was in the business of supplying boats of all denominations at a fixed rate and guaranteeing the “conduct and good behaviour” of the boatmen.Footnote 103 The question about servants that kept the colonial machinery perplexed all through these years must have surely “encouraged” the police to support any civic plan, such as the one executed by Nowland.

The efficacy or the longevity of Nowland's office is uncertain. Writing in the 1880s, W.H. Carey called it a “novel undertaking” but added that “we do not wonder that it was not of long continuance”.Footnote 104 But by the time Carey was writing, public memory could have suffered a collective loss. There is definite evidence that the office existed in 1834. In order to deal with the increased pressure of people seeking help from the Calcutta District Charitable Society, the society made lists of people seeking employment. One of the places the list was sent to was the Servant Registry Office that Nowland had established.Footnote 105 However, there is also contradictory evidence, as in 1833 one Mr Murray submitted a proposal to the Calcutta Trade Association for the establishment of an office for the registry of servants, which “for want of support from the Public […] was not established”.Footnote 106

Why did the public support change if the latter is taken to be true? After all, not very long before, during the 1786–1787 debates, it had been emphasized that the “nuisance” related to servants existed “with undiminished, if not increasing force”.Footnote 107 The most probable answer is the passing of the by-law, first in November 1814 for “Journeyman Workman or Labourer” and then in 1816 for domestic servants, which fulfilled the demand of masters and mistresses to have a tribunal of appeal against their servants “for any wilful miscarriage or ill behaviour insolence or neglect of duty”.Footnote 108 In sharp distinction to earlier practices, the by-laws prescribed the JPs to take cognisance of such complaints as made by masters and mistresses, and to examine witnesses, defence, and evidence after taking complaints in writing, thus establishing a non-summary justice procedure. Subsequent history through case law shows that this was a nominal and not a substantive change; a summary mode of justice continued in disputes between masters and servants.Footnote 109

These by-laws mark both a change and continuity from previous decades. In them, the power to adjudicate was squarely invested in the JPs, thus at least nominally chipping away the power of the police. In this regard, the claim made in the 1816 by-law that European masters had no “tribunal” for redressing grievances might appear valid, as because of the absence of the Court of Zemindary and the very irregular sittings of the court of quarter sessions, there might have been a lack of a formal tribunal. This lack, however, does not curtail the strong possibility that the SP continued regulating master–servant disputes. In part, such a claim of absence of tribunal was a legal fiction. It signified the absence of a formal mechanism of control but simultaneously obliterated the history of active policing based on arbitrary powers that Motte himself alluded to and which Hastings desired to establish. The four orders passed in 1759, 1760, 1766, and 1774, the complaints made against servants in the Court of Zemindary, of which unfortunately only one volume is traceable, the extracts from Playdell's charge sheet in 1778, the close involvement of Motte in preparing a number of plans and proposals both for wage control and registration, and Jones's remonstration as late as 1788 are evidence of policing provision that was available to and used by masters and mistresses. The culmination of these varied regulations was Regulation VII of 1819, which remained the guiding principle for adjudicating the master–servant relationship until 1860.

The repeal of Regulation VII once again brought back the debates about registration, in which the role of the police, such as in the case of NWP discussed above, became important. In this phase, nonetheless, the government had actively denied attempting to frame a master–servant law with criminal prosecution of the servant for the breach of contract. It had also shied away from formulating any rule directly based on servant registration, although some provincial authorities, Anglo-Indian and Eurasian communities, and cantonment and military authorities favoured such a move. However, a “voluntary” practice of registration seems to have mushroomed in different cities across India both under police and municipal bodies. In NWP, this happened directly under the aegis of the police. As the debate in this period shifted largely towards the need for verification, identification, and maintenance of the employment history of the servant, laced with the stigma of criminality, registration became the preferred mode of regulation. This phase strongly indicates that the unique position of the servant as the “intimate other” who worked in the household, as opposed to other labouring groups, consolidated the fusion of wage and work disputes with crime. It was easier for the masters to turn the dispute of wage and arrears into an allegation of theft vis-à-vis servants than any other labouring group. The government had time and again pointed out that the general charges of crime committed by servants could well be addressed by the provisions of the Indian Penal Code. The recurrent demand by varied sections of the European community points to the fact that in the tool of registration they saw a mechanism not only to control crime but also to use the crime of theft as a ploy to discipline their servants in general.

To end with reflections on the situation today, the rights-based demand for labour legislation does not involve the role of the police. In prescribing the mediating power of the law to organize the employer–employee relationship, recent attempts include registration, the fixing of minimum wages, sanction for sickness and holiday leave, and other safety and penalty provisions. The draft bill of 2017 emphasized compulsory registration for domestic workers, service providers (that is, the agency or the person providing the worker), and employers; failure to register would lead to punishment.Footnote 110 The regulating power in the bill was vested in the District Board followed by the State Board, and not with the police.Footnote 111 However, moving away from the legal sphere to everyday instances, both in the past and the present, “servants committing crime” is not just a construction of middle-class fear or the state's hyper-surveillance discourse. Some of these charges have proven to be right; but equally important is that some have not been. More so, the disturbing normalcy with which servants are instantly accused of household crime and theft is the result of the long history of policing of their conduct. Historically, keeping wages in arrear (wage theft) has been a usual practice on the part of the masters but the charge of theft was framed when servants demanded their due wages. In terms of social stigma, the imbalance between servants’ portrayal as potential criminals and masters’ and mistresses’ sense of being unsafe and insecure owing to servants’ presence in the household in spite of being themselves convicted for beating, raping, and even murdering is telling. Such an imbalance both accentuates and reflects the social power of the hiring class. The easy access to the institutions of the state that class privilege gives them is not just a product of the “cultural” settings in which the state evolved, but also of the legal culture that the state promoted. In this legal culture, well-meaning intentions also run the risk of subversion. For instance, the draft bill of 2012 that aimed at regulating agencies and private placement services in Delhi provisioned that domestic workers had to satisfy the agency of their character and antecedents. It was pointed out by the group Shakti Vahini that character certificates procured by placement agencies would become a tool of exploitation.Footnote 112 The historical attempt to register servants as both being part of and proxy to the master–servant laws met with limited success, but registration and verification made their way both into the practices of colonial times through the informal practice of employers giving “chits” or character certificates to their servants on discharge and in the contemporary logic of surveillance of the informal labour force. How far this form of surveillance identification based upon a strong stigma of criminality and practices of character certificate-based identification will cease to exist once the servant becomes a “worker” is yet to be seen.