Scenes of Insurrection

A woman in black, black duct tape sealing her mouth, iron chains wrapped around her torso and wrists, clutching a small stack of blank papers, walks in silent defiance on an unidentified urban street (see Channel 4 News 2022). Footnote 1

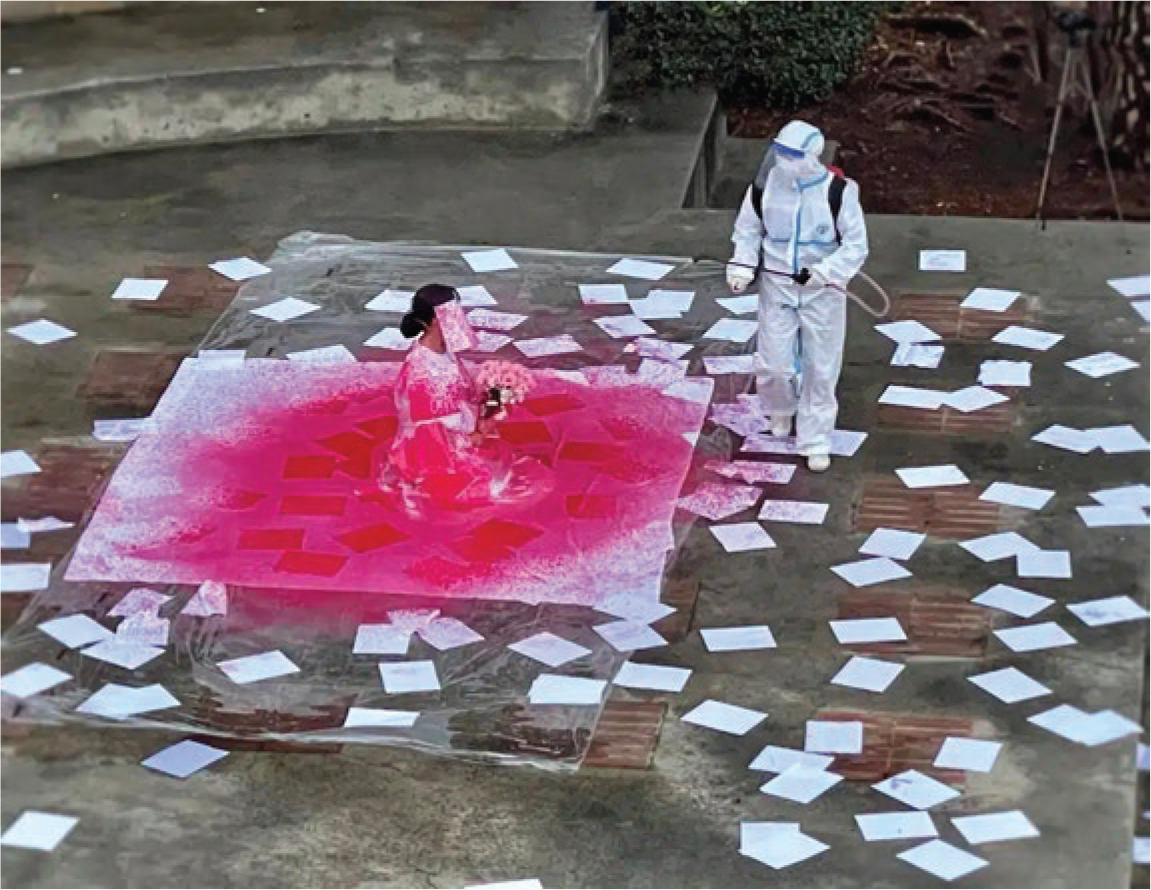

A woman kneels on the ground, which is carpeted with blank A4 sheets of paper (the standard size used in China), holding a bouquet of white flowers, her face and body fully pasted with white sheets of paper, while a person in a hazmat suit relentlessly sprays pinkish-red paint all over her costume (see Positions Politics Reference Politics2023).

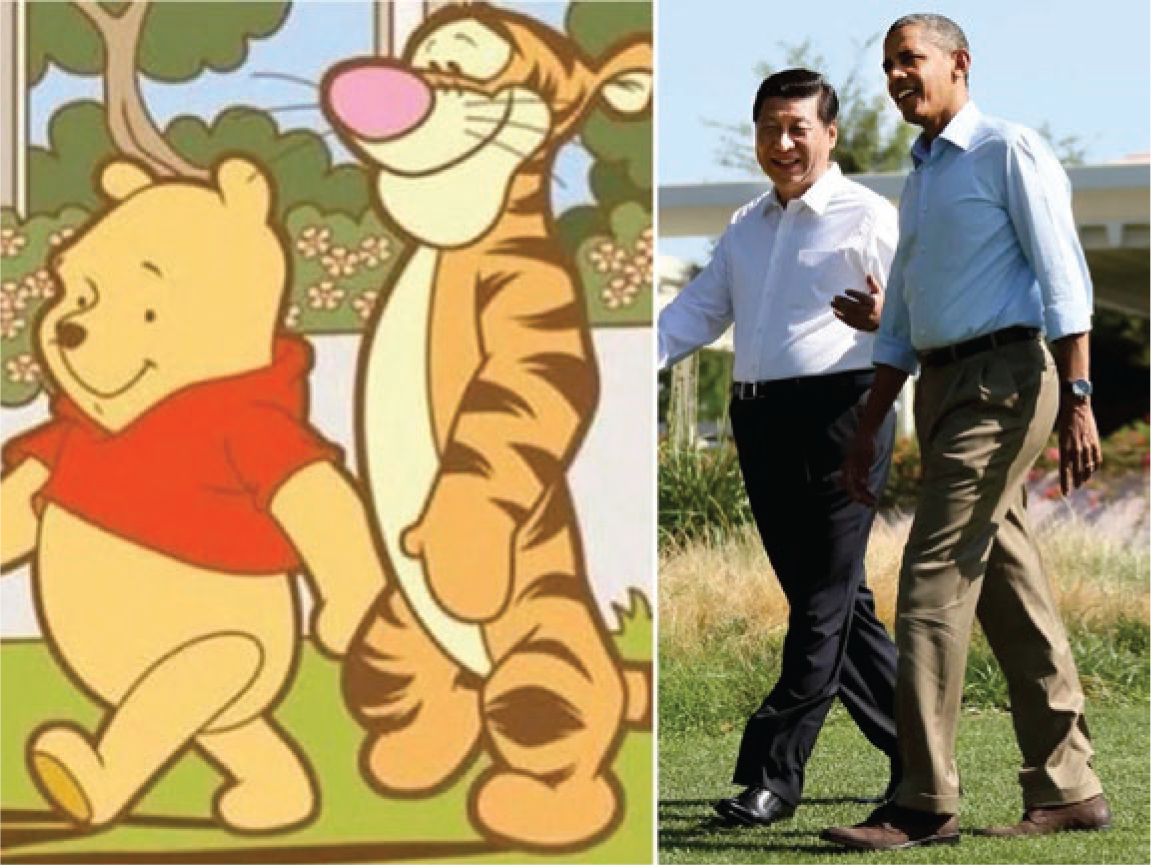

An oversized figure looking like a cross between Winnie the Pooh and a Chinese emperor carries a blank A4 paper. In contrast to its comical appearance, the figure speaks in a somber voice, “I believe Chinese students, most of them, don’t know what happened 30 years ago. I am a little bit worried about their freedom, [which] may be taken by the government” (see Global News 2022; my transcription).

Massive crowds gather in Urumqi, Shanghai, Chengdu, Beijing, and multiple other Chinese cities; they repeatedly chant in unison a familiar CCP (Chinese Communist Party) slogan: wei renmi fuwu (为人民服务, serve the people); followed by call-and-response taunts: gongchandang (共产党, Communist Party); xiatai (下台, leave the stage/step down); Xi Jinping (习近平); xiatai (下台) (see Lee Reference Lee2023; PBS NewsHour 2022).

All of the aforementioned scenes of civil revolt came from online sources, including posts from social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, X/Twitter, Weibo, etc.), individually shared personal audiovisual feeds, and news video excerpts on YouTube. Benefiting from the transnational flow of information and populations in a glocalized era, these protests exposed the vulnerability of an authoritarian regime’s sophisticated censorship. The systems failed to suppress its people’s desire to achieve political agency and garner international attention. Although documented online, these protests took place in actual and geographically disperse locations: the first and the fourth incidents in China; the second in the United States; the third in Australia. The protesters all gathered in defiance against China’s draconian zero-Covid policy, which enforced severe quarantine of its population during the global pandemic, from January 2020 to December 2022.

The sampled scenes of insurrection share several expressive traits:

-

(1) They used performance as a means of political protest.

-

(2) They happened in public and their images/messages—visual, aural, thematic, symbolic—were transmitted and disseminated globally through internet channels.

-

(3) The protesting crowds appeared decentralized, sporadic, and voluntary; most performers were masked and anonymous.

-

(4) Most provocatively for my inquiry: the scenes showed the structural affinity between performance and politics, revealing how both performative spheres tend to exceed the externally imposed limits and boundaries of their power. Neither the agents of politics nor performance can fully control (contain, condition, manipulate, enhance) the impact of their actions on their witnessing publics, let alone anticipate how they may change the observers’ hearts, minds, and behavior. These audience members—be they witnesses/spectators for artistic performances, or subjects/citizens for political performances—have the power to interpret the messages and shape their responses, thereby shifting the power dynamics in the body politic.

Performative Agency via Self-Proclamation

Politics and performance both involve “a repertoire of scenarios, embodiments, gestures, repetitions, and rhetorical and improvisational strategies through which a political event reveals its theatricality and a theatrical performance foregrounds its politics” (Gluhovic et al. Reference Gluhovic, Jestrovic, Rai and Saward2021). Defining politics broadly as “a contest of power, values, resources, and representation,” and performance as “any action that is framed, presented, highlighted, and displayed,” we may appreciate these two sociocultural spheres as “co-constitutive.” In short, both spheres place a premium on generating “symbolic acts” and utilizing “an affective register” to galvanize their addressees/receivers (Gluhovic et al. Reference Gluhovic, Jestrovic, Rai and Saward2021). Extending this analysis, I suggest that both politics and performance are reflexive genres; they best maintain their democratic transparency by disclosing their performers’ motivations, affiliations, and investments, while acknowledging their viewers’ spectatorial agency. If the performance of politics focuses on empowering the citizens/constituents to participate in the legislative/power-making process, then the politics of performance relies on the performers to openly share their political agenda with their viewers, hence giving them the freedom of deliberation and choice.

In this reflexive, egalitarian spirit, I share my authorial agency as a Taiwanese American performance critic with a proclivity for democratic values. From this admittedly partial and politicized perspective, I’ve rejoiced in watching the recent performative revolts staged by ordinary Chinese citizens and expatriates, including some Chinese and Chinese American students at the University of Southern California where I teach (see Hartman Reference Hartman2022; BBC News Zhongwen 2022). I find these protests exciting, hopeful, and politically energizing, even though my elation is tinged with trepidation. First, my hope; then my foreboding.

Along with many other overseas China watchers, I’ve discerned the tacit tributes many anti–zero Covid protest performances paid to an earlier incident, one astonishing the world with its brazen courage. On 13 October 2022, a lone man in construction garb hung two white banners across Beijing’s Sitongqiao (Sitong Bridge, or Sitong Overpass). One banner inscribed his defiant demands in big red characters, which I’ve translated into English: “No [to] nucleic acid test; Yes [to] food/No lockdown; Yes freedom/No lies; Yes dignity/No Cultural Revolution; Yes Reform/No [totalitarian] leaders; Yes votes/Don’t be slaves; Be citizens.” Footnote 2 The other banner carried words of exhortation: “Strike at school/Strike at work/Remove dictator and state thief Xi Jinping/Arise all who refuse to be slaves! Oppose dictatorship/Oppose authoritarianism/One person one vote to elect the [CCP] Chairman.” Footnote 3 The man drew further attention to his display by burning tires to emit plumes of dark smoke from the overpass, simultaneously using a loudspeaker to blast looped catchphrases of his calls to strike and to remove Xi.

The lone activist, later identified as Peng Lifa (彭立发), a.k.a. Peng Zaizhou (彭载舟) on TikTok and Twitter (now X), performed his political protest with theatrical panache. He timed his protest just before the opening of the CCP’s 20th congress on 16 October, when Xi was “expected to assume an unprecedented third term as General Secretary at the end of the party’s Congress” (China Change Reference Change2022). By denouncing Xi as a “state thief,” Peng referred to the two-consecutive-term limit to China’s presidency instituted in 1982 by Deng Xiaoping, who aimed to avert the kind of dictatorial power and personality cult that Mao Zedong had wielded, resulting in the catastrophic Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). In the face of Xi’s impending ascension as the CCP’s supreme leader for life, Peng’s white banners draped the bridge like traditional mourning clothes, as memorials to the de facto end of China’s 40-year-long reform period (1978–2018) (see Doubek Reference Doubek2018). Peng strategically sited his solo insurrection on the Sitong Overpass, a 280-meter-long “enclosed 6-lane expressway bridge that can only be accessed through traffic from either direction”—a spatial feature that afforded him “just enough time—a few minutes—to carry out his plan in Beijing’s barrel-tight security before the police and firefighters arrived” (China Change Reference Change2022). Peng’s action maximized the crowd’s attention with multisensory appeal: the smoke spectacle drew focus to his banners and the loudspeaker amplified his messages in highly citable soundbites. The performer knew that his open rebellion would last only for a moment and would undoubtedly end with his arrest, letting the public bear witness to his political martyrdom. Footnote 4

Dubbed the “Bridge Man,” echoing the brave “Tank Man” Footnote 5 during the 4 June 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, Peng chose to sacrifice himself to deliver his political message. Knowing his protest would be brief, Peng carefully safeguarded and expanded his political performance. At around 4:00 a.m. Beijing time, prior to Peng’s bridge action on 13 October 2022, someone anonymously emailed to “several overseas Chinese language websites” Peng’s full script, “Offensive Tactics for Business Strike, Student Strike, and the Removal of Xi Jinping.” Footnote 6

The PDF file has 21 units with a [lead] that reads, “This is a broadside against the state thief, this is a protest toolkit, this is an election platform, and this is a policy plan, all for the purpose of opposing despotism and [saving] China. Those who violate our human rights must be rejected no matter how powerful they are.” (China Change Reference Change2022) Peng’s file ends with a copyright, declaring that he is the principal author of the document and apologizing for any violation of other authors’ copyrights in the units collected in his file, including “Charter 08,” a proposition for democracy and human rights protections attributed to the 2010 Nobel Peace laureate Liu Xiaobo (China Change Reference Change2022).

Those affected by Peng’s abbreviated call to action on Sitongqiao—from those in power to the citizens on the periphery, both domestically and internationally—responded swiftly. Peng was seized by the police; his online presence, identity, and incendiary political statements were scrubbed from China’s media outlets. Anticipating the fierce censorship that would follow his action, Peng outfoxed the CCP authorities by electronically transmitting advanced copies of his “protest toolkit,” which enabled sympathetic spectators—however they encountered the protest—to recount and extend the reach of the activist’s heroic feat. Spectators found inventive ways to disseminate Peng’s call to action, including scribbling his slogans on the walls of public restrooms (these had no surveillance cameras inside) and PCR Covid test booths (China Change Reference Change2022). Peng’s messages on the bridge, reproduced on countless posters and stickers, also found new life on numerous university campuses and in metropolises across the US, Europe, Japan, and Australia. International news and social media indicated the historical significance of Peng’s dissidence—some citing a Chinese proverb that Mao Zedong once used (in 1930) to extol the communist takeover of mainland China: “A single spark can start a prairie fire” (see, for example, Hartcher Reference Hartcher2022).

The ironic prescience of Mao’s phrase should have served as a warning for today’s CCP. The world saw the “prairie fire” spread roughly a month after Peng hung his banners, with images of Chinese people holding sheets of blank A4 paper in front of their masked faces in the wake of the Ürümqi fire that killed 10 Uyghurs, reportedly because firefighters were hindered by the strict Covid lockdown (see Che and Chien 2022). My opening examples of protest performances, as spontaneous scenes of insurrection, are a minuscule sampling of unparalleled civil unrest in China and the worldwide Chinese diaspora. Peng’s banner on the bridge was the “single spark” that ignited these uprisings.

While startling and rare, Peng’s civil disobedience is not unprecedented in China, contrary to expectations regarding the legality of public protests in this autocratic country. “Rightful resistance,” a term proposed by Kevin O’Brien and Lianjiang Li (2006), explained how peasants in rural China used legal means to denounce the corruption of regional governments to the central authorities. Peng’s protest, however, pushed the nebulous line between legality and insurgency, between the righteously legitimate and blatantly seditious. Some of his tactics exhibited rightful resistance, as when he called Xi out as the “state thief” on the basis of Deng Xiaoping’s law. But Peng’s other tactics, especially those championing democracy and human rights, were undoubtedly received as subversive by the CCP’s one-party political hegemony.

Peng’s playbook seems to have inspired subsequent rounds of antilockdown protests, with demonstrators adopting sanctioned methods of public complaint to voice their rightful resistance. Protesters frequently resorted to mouthing the CCP’s own slogans, such as “serve the people,” or expanded their public grieving for not only the recent dead but all victims of the stringent zero-Covid policy, expressing their rage through pathos. To playfully spite their disciplinarians, they often used sardonic wit in their performances. A protester in Shanghai cunningly showed how to shift between innocuous and riotous tactics. In a news video showing hundreds of Shanghai residents massing on the Ürümqi Road, a man holding a bouquet of chrysanthemums—often used in Chinese funerals—called out, “We need to be braver! Am I breaking the law by holding flowers?” The crowd shouted in reply, “No!” (see The Sun 2022). His theatrical activism—with an outspoken proclamation and a funereal prop—baited the police to commit the unrightful action of abusing a flower-bearing messenger.

According to one CNN report, “Some videos show people singing China’s national anthem and ‘The Internationale,’ a standard of the socialist movement, while holding banners protesting the country’s exceptionally stringent pandemic measures” (Gan and CNN’s Beijing Bureau 2022). While mounting these rightful, unarmed, peaceful protests, demonstrators often sneaked in sentiments that exceeded the government’s allowable limits. Lamentations for the Uyghurs burned to death in the Ürümqi fire of 24 November 2022 rebuked China’s ongoing political, cultural, and religious oppression of this mostly Muslim, Turkic-speaking ethnic group. Some overseas protesters went further. On 1 December 2022, a Chinese UCLA student who belonged to the dominant Han ethnicity used a public memorial to apologize for China’s concentration camps for Uyghurs, leading the crowd chanting in Chinese: “Tingzhi jizhongying (停止集中营)/Ziyou Weiwuer ren (自由维吾尔人)” and in English, “Stop Concentration Camps! Free Free Uyghurs” (Uyghur American Association 2022).

The Ürümqi victims were, at that time, only the latest in a long litany of causalities from the harsh zero-Covid rule, one of Xi Jinping’s signature policies. According to countless Weibo posts, daily lives in China since 2020 had been severely and negatively affected by this inflexible policy. Police broke into the homes of those quarantined elsewhere (in government facilities) to enforce extreme acts of virus-cleansing, leaving the houses in shambles and house pets tortured. There were obligatory daily Covid tests with often misassigned positive results. Authorities collected private information through pervasive individual code-scanners and banned Weibo accounts with even the slightest hint of civil discontent (see for example people.cn 2020; Gao Reference Gao2022; Wang Reference Wang2022). “It’s like our life is without dignity. It’s a very very painful experience,” said Yicheng Huang, a 26-year-old exiled protester (see WION 2023). As news of these drastic measures were disseminated by both the victims and observers on social media (quickly scrubbed), the people’s dissatisfaction grew to a fury, exploding in street protest actions.

“The most serious mass protest incident in nearly 30 years […] ‘White Paper Movement,’” read an Instagram post—originally written in Chinese—on 29 November 2022 (Jiuzyoung 2022). This declaration comported with a plethora of contemporaneous comments by international political scientists and news pundits, who proclaimed the latest rounds of antilockdown demonstrations and concomitant widespread mobilization comparable only to those of the 1989 prodemocratic rallies in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square and throughout China. Such comparisons highlight the historical significance of the White Paper protests beyond their immediate opposition to the severe Covid-lockdown measures and resulting casualties. They affirmed the pivotal roles that younger Chinese, mostly college students, played in both the 1989 prodemocratic movement and the 2022 White Paper protests. As US-based American Uyghurs Association Chairperson Yili Xiati put it,

I feel very comforted that [a Han UCLA student] apologized. His attempt to give voice to the Uyghurs is sincere. This action was a surprise but also long-anticipated. Thank him! This demonstrates that the Chinese youth can give us hope. I’ve always emphasized that once China’s brainwashing and internet lockdown are overthrown, I believe [we will see that] people in that land have humanity, morality, and sense of justice. (Wu and Cheng 2022; my translation)

Like Yili Xiati, I felt heartened by the emancipatory awakening of Chinese young people. The reference to the 1989 Tiananmen Square tragedy, however, unavoidably triggered my fear. My memories of the Tiananmen Square massacre, admittedly mediated by the US news media, centered on the brutality of the Chinese government, which launched a military suppression of the largely student-led nonviolent prodemocratic movement. Evoking this tragic history filled me with dread for the consequences awaiting the antilockdown protesters. My fear was justified: the Chinese police harassed, arrested, and beat BBC journalist Edward Lawrence, whose non-Chinese identity and journalistic license did not shield him from police brutality in Shanghai. Footnote 7 The increasingly aggressive militant stance that Xi’s regime has taken regarding China’s territorial claim to Taiwan further exacerbated my fear. I worry that Taiwan might follow Tibet, Xinjiang, and Hong Kong—all of which continue to suffer from China’s subtle, insidious, or overt oppression. Would China take some perverse inspiration from Russia’s war in Ukraine, also motivated by spurious claims of “reunification”?

Feminist philosopher Katie Stockdale observed that “we only hope in contexts in which we judge that our own agency is insufficient to bring about the outcome we desire” (2019:30). In this light, we may consider hope the sanguine face of our masked fear of failure, humiliation, subjugation, and death. Fear, along with pity, are the twin emotions Aristotle identified as propelling the purging process leading to the audience’s catharsis. So far, I feel no catharsis, nor do I expect the White Paper movement—erupting, fuming, and subsiding all in November 2022—to fundamentally change the CCP regime. What we learned in 2023 was that countless White Paper protesters, especially women, were detained and disappeared indefinitely by the police. Yet—and most surprisingly—the CCP government abruptly ceased its zero-Covid policy in early December 2022, seemingly bowing to the will of its people. As an ongoing grand political performance, Xi’s regime conceded to the raging interactive performances staged by its audience: the Chinese people (Zheng Reference Zheng2023). No matter their consequences and promises, these protest performances that some netizens had optimistically dubbed as the “White Paper Revolution” have stirred my political consciousness. They cannot be overestimated as visions of hope.

White Paper Revolution (WPR) and Chinese Performance Art

As performance scholars, we may readily accept that the massive street protests raging in China and its diaspora in late 2022 were performative, given their quest to publicly show their doing. Footnote 8 While assessing them as performances, we must also acknowledge that these antilockdown protests—which I subsume under the hopeful moniker of “White Paper Revolution” (WPR)—took place not for artistic intent and interest, but for political agitation and social change. As performances of politics, they have cost some of the major players, such as Peng Lifa, their freedom, if not life, but they have also demonstrated a degree of efficacy in achieving their specific aim of ending the zero-Covid policy. So far, their larger political aspirations—democratic freedom, self-determination for Chinese citizens of all ethnicities, and liberation from constant government surveillance and censorship, among other causes—have been less successful. Yet, the WPR has undeniably made a positive impact on the world’s perceptions of the Chinese people’s courage and creativity under authoritarian rule.

The White Paper Revolution has underscored the truism that politics is both central to Chinese life and the most perilous area for public intervention (risking individual, familial, or group reprisal). The WPR protests appear to have subsided after China ended its zero-Covid policy on 5 December 2022—though given the regime’s control of unfavorable information and images, one cannot be certain. During the movement’s active phase between November and December 2022, then, how did the WPR protesters sustain their political movement in the face of substantial danger?

The most direct answer to the question is: through tactical performance maneuvers and furtive behavior.

As mentioned earlier, most White Paper protests appeared decentralized, spontaneous, and yet also somewhat premeditated—organized through quick-fire social media posts and reposts. These features suggest that performances in anonymous masses, in which a singular leader cannot be ascertained and eliminated, can offer participants a degree of protection, if not full immunity. Indeed, I was most impressed with those young WPR protesters’ real-world sophistication: They demonstrated their resolve for public good, despite the high probability of self-sacrifice (i.e., being outed and arrested as dissidents); simultaneously they took risk-averse self-protective measures (wearing masks, joining with others in unidentifiable crowds, leaving/erasing/passing around internet posts). After all, we want heroes but not martyrs, even when martyrdom might not be optional.

The WPR demonstrators, united as they were by their explicit political motivation and specific aims, resorted to multiple other performance modes to stage their street actions. Did WPR’s pervasive usage of performance, literally defined as a framed creative action, teach us anything about Chinese performance art in contemporary Chinese societies, including its diasporas?

To me, the fact that performances had appeared so frequently in the WPR demonstrations implies that Chinese performance art has transformed from its previous sociocultural status as an extreme, individualistic artistic medium into an acculturated method for political agitation. Performance art, or, in its Chinese translation, xingwei yishu (行为艺术, behavior art), has become a cultural language, an intertextual lexicon of citable behaviors. Footnote 9 As readily transmissible as internet memes, if not always humorous in tone, xingwei yishu provides plenty of multisensory behavioral prototypes (visual, auditory, kinetic) that can be sampled, duplicated, variously appropriated, reproduced, reconfigured, and reassembled to serve numerous purposes and occasions. In short, xingwei yishu has moved from the artistic peripheries toward the sociocultural mainstream.

I cannot elaborate here how xingwei yishu evolved throughout its nearly four-decade history (1985–), Footnote 10 but I will annotate a few turning points, as a shorthand sequel to my previous study on Chinese time-based art (Cheng Reference Cheng2013).

Qiangji Shijian (枪击事件, 1989)

Xingwei yishu began in China amid the 1985 New Wave Art Movement (see Gao [Reference Gao1986] 1993). As an embodied, transient, and economically affordable medium (using the artist’s own body), flexible enough to evade institutional control, xingwei yishu nevertheless entered a much more public life with infamy. During Beijing’s China/Avant-Garde exhibition (February 1989), two then little-known artists, Xiao Lu (肖鲁) and Tang Song (唐宋), performed an unexpected xingwei—an explosive happening that the eminent Chinese curator Li Xianting (栗宪庭) called Qiangji Shijian, known in English as Pistol Shot Event (1989). Footnote 11 Xiao and Tang’s impromptu xingwei forced China/Avant-Garde to close on its opening day. The Pistol Shot Event, for its incendiary nature and temporal proximity to the nationwide prodemocratic movements of April–June 1989, earned the reputation as “the opening shots of Tiananmen” (see Colville Reference Colville2021). Thus, xingwei yishu began its tenure in China with a violent, high-profile entanglement with politically subversive actions.

East Village Xingwei Yishu (1993–94)

The alliance between Beijing’s contemporary artists and the prodemocratic student activists during the 1989 Tiananmen protests made the CCP authorities suspicious of avantgarde art. As a result, after the incident on 4 June, all contemporary art activities were suppressed for three years (see Cheng Reference Cheng2013:34–47). This political circumstance had contributed to the historical significance of xingwei yishu’s reemergence in 1994 in the Dong cun (东村, East Village) neighborhood of Beijing, a communal hothouse for xingwei yishu where its young artist-residents included Ma Liuming (马六明), Zhang Huan (张洹), Zhu Ming (朱冥), and Cang Xin (苍鑫).

Now globally recognized as groundbreaking Chinese performance artists, the East Village cohort staged perilous live actions, putting themselves in psychosomatic duress during performance. Their xingwei artworks have acquired a sheen of transcendent mystique through the photographic documentation of Rong Rong (荣荣) and Xing Danwen (邢丹文)—artists in their own right (see Johnson Museum of Art 2023). The aesthetic appeal of these now iconographic images—capturing the sacrificial, self-harming actions of the stoic xingwei artists—brought worldwide attention to extreme Chinese performance art.

Controversial Exhibitions

The dark clout achieved by the East Village xingwei artists found its wider reach through three pivotal pioneering exhibitions—each known by its bilingual title in English and Chinese: Post-Sense Sensibility: Alien Bodies & Delusion/Hou ganxing: Yixing yu wanxiang (后感性:异形与妄想, 1999), cocurated by Wu Meichun (吴美纯) and Qiu Zhijie (邱志杰); Fuck Off/Buhezuo fangshi (不合作方式, 2000), cocurated by Ai Weiwei (艾未未) and Feng Boyi (冯博一); and Infatuation with Injury/Dui shanghai de milian (对伤害的迷恋, 2000), curated by Li Xianting (栗宪庭). These in-yer-face exhibitions, featuring fetal cannibalism, corpse display, self-mutilation, animal torture, and decaying pork stuffed inside a red sofa, brought Chinese performance art to the attention of both foreign journalists and the CCP’s indignant dignitaries. Waldemar Januszczak, a Sunday Times art critic who hosted the contentious documentary Beijing Swings (2003) for the British Channel 4 exclaimed, “the most extreme art currently being produced anywhere on the planet is, like so many other things, made in China” (in Herring Reference Herring2003; see Cheng Reference Cheng2013:117–18). Januszczak’s fervent remark could well claim its solid basis—if ironically and inversely—from the Chinese Ministry of Culture’s 2001 edict banning and threatening jail terms for publicly displaying any xingwei deemed xiexing (血腥, bloody), canbao (残暴, violent), or yinhui (淫秽, obscene) (Artda [2001] 2010) due to the artist’s self-abuse, mistreatment of animals, or exhibiting corpses “in the name of art” (Renmin ribao 2001, my translation; see also BBC 2001). As the last millennium turned, xingwei yishu found its art-fringe perversity promulgated through these official characterizations: bloody, violent, and obscene, too easily scandalous, and blatantly catering to the Western taste for aberrant exoticism.

Earthquake Activism

Arguably, xingwei yishu retained its status as a marginal art medium until it was “normalized” as an activist tool after the disastrous 7.9-magnitude earthquake in the Sichuan province (12 May 2008). This shift in xingwei yishu’s standing had much to do with the efforts of a polemic figure: Ai Weiwei. A catalyst in abetting xingwei yishu’s earlier notoriety, Ai was also a decisive force in modifying the genre as a set of socially reproducible behavioral modes. This ironic contrast also impacted Ai’s personal reputation: while internationally celebrated as the paragon of expatriate human rights activists from China, Ai Weiwei is domestically little known to most younger generation Chinese. Footnote 12

Ai Weiwei’s opposition to the CCP regime peaked in 2008 when he boycotted the Beijing Olympic Games and rallied for the Sichuan earthquake victims (see Cheng Reference Cheng2013:424–30). Ai used his social media dexterity to recruit and mobilize more than 100 participants in towns across Sichuan to join his political activism and engage in “citizens’ investigations.” Their combined efforts culminated in Ai’s Sichuan Earthquake Names Project (2008–2009), an installation that included 5,219 names of students crushed to death by shoddily constructed school buildings during the earthquakes. Ai kept up the pressure on corrupt officials and evasive bureaucrats by focusing the world’s attention on the Sichuan calamity with his international series of earthquake-themed art projects. Ai’s relentless political agitation led to his 81-day detention by the Chinese authorities in 2011, and eventually made him choose the path of self-exile from China in 2015. Footnote 13

Taking his earthquake projects as her case study, Meiqin Wang places Ai Weiwei’s pursuit of social justice in the contemporary lineage of socially engaged art (see Wang Reference Wang2019). In addition to Ai’s contribution, what Wang calls the “social and public turn of contemporary Chinese art” (2019:3) in the 21st century may also explain why xingwei yishu—or rather, in its more quotidian label as xingwei/behavior—has become refashioned as self-determined, often premeditated, extra/ordinary actions. Xingwei/behavior has developed as ephemeral public behavior that can be used to shed light on various blameworthy civil issues, from government corruption and ecological degradation to labor exploitation; oppression of political activists to Covid-lockdown inhumanity; from gender-, sexuality-, and ethnicity-based discrimination to #MeToo sexual harassment exposures.

Ideological Machinery

Perhaps the most dominant, if inadvertent, cause for xingwei yishu’s deviation from its initial sociocultural position as an elitist and disreputable art form to an expedient cultural tool for public behavior—whether activist or simply eccentric—has been China’s now decade-long Sinocentric shift toward an ever-tightening nationalistic surveillance state. Since his ascension as the country’s paramount leader in 2012, Xi Jinping has increasingly modeled his leadership style on Maoist principles. Footnote 14 As a supreme political performer, Xi himself “imitates Mao on many occasions, including his gestures, dress, and rhetoric” (Marquis Reference Marquis2022); and “launched the largest ideological campaign that China has seen since Mao was in charge” (Zhao Reference Zhao2016:83).

Xi’s ideological campaign set him apart from his immediate predecessors Hu Jintao (2002–2012) and Jiang Zemin (1989–2002). Each of them had chosen to downplay ideology and to tolerate—within limits—the expression of liberal ideas. (87)

Jiang’s and Hu’s regimes—each following and shaped by their respective interpretation of Deng Xiaoping’s socialism with Chinese characteristics directives (see Moak and Lee Reference Moak and Lee2015)—sanctioned a less restrictive cultural climate, which allowed Chinese contemporary art, including xingwei yishu, to enjoy a productive, critically acclaimed, and, for some painters, highly profitable period. In fact, even the aforementioned Ministry of Culture’s 2001 edict did not prevent the most zealous xingwei artists from producing some of the medium’s least ethically acceptable pieces, such as Zhu Yu’s horrendous Xian ji (献祭, Sacrificial Worship, 2003), made after his cannibalistic xingwei, Shi ren (食人, Eating People, 2000), at which the 2001 Ministry of Culture edict was specifically aimed (see Cheng Reference Cheng2013:106–69). Footnote 15

A China-based curator who wished to remain anonymous lamented:

With the rise of Xi Jinping, there has been an overall ideological tightening in China—not just in the arts, but probably first with universities, media, and gradually hitting contemporary art […] Red lines [of censorship] have gotten tighter [… and] what might have flown under the radar are more scrutinized. (in Movius Reference Movius2022)

Symbolic of Xi’s Maoist gambit to better control China’s diversifying, even privatizing, cultural scene was his 2014 “Talks at the Beijing Forum on Literature and Art” (Creemers Reference Creemers2014), a speech if not mimicking, then closely reminiscent of Mao Zedong’s 1942 “Talks at the Yanan Forum on Literature and Art” (Marxists.org [1942] 2004). Mao’s speech emphasized the political function of art and literature, dictating these creative endeavors to serve the broader revolutionary movement. He urged writers and artists to align their perspectives with those of the proletariat and the masses, and commanded that their cultural output function as a powerful tool for the revolutionary machine. Following Mao’s exhortation for literature and art to serve the party and the people, Xi’s speech urged cultural workers to meet their sociopolitical responsibility and promote socialism’s core values. Although he acknowledged that “a new springtime” had ushered in many excellent works since the reform and “opening up,” Xi nevertheless echoed Mao’s condemnation of Chinese reactionaries’ all-out efforts to favor quantity over quality, criticizing that “there is quantity but no quality” and that [made-in-China] cultural products were plagued by the problems “of plagiarism, imitation and stereotypes” (see Marxists.org [1942] 2004; in Creemers Reference Creemers2014). Just as Mao showed his contempt for money, so too did Xi advise cultural industry workers not to be absorbed into “the market economy.” Xi further identified the eternal value of literature and art as the pursuit of “the true, the good, and the beautiful,” guiding people towards a positive outlook and moral judgment.

While many of his remarks, now codified as the “Xi Jinping Thought,” may sound like bureaucratic platitudes, they do come with punitive authority as well as patronage incentives, supported by Xi’s army of online and print censors, public security personnel, plainclothes police, and regional CCP officials. Footnote 16 Xi’s strongman-benefactor style of authoritarian governance evokes, for me, Michel Foucault’s “repressive hypothesis,” questioning: “Are prohibition, censorship, and denial truly the forms through which power is exercised in a general way […]?” ([1978] 1990:10). Foucault argues that the “polymorphous techniques of power” do not merely suppress illicit expressions [of sexuality, here as a stand-in for any anomalous behaviors], but they also effectively foster “discursive production” and “the propagation of knowledge” concerning tabooed/suppressed/repressed subjects and practices (11–12). I find Foucault’s joining of proscription and production illuminating in understanding the paradoxical ties between censorship/repression and production/coercion that Xi’s Sinocentric cultural ideology appears to enforce/encourage.

As his 2014 Beijing Forum talks—and many subsequent talks on art and literature—promulgate, Xi’s Maoist cultural ideology explicitly serves to bolster the CCP’s hegemony. Nevertheless, these speeches, as CCP propaganda, have broader sociocultural, political, and economic impact on China’s cultural workers—including artists, writers, and even celebrities (in performing arts, cinema, popular cultures, sports, and entertainment)—telling them what’s desirable and what’s punishable in contributing to China’s cultural industry.

Xi’s endorsement of “the true, the good, and the beautiful” in creating cultural artifacts largely aligns with the Chinese Ministry of Culture’s 2001 interdiction against the open display and production of “bloody, violent, and obscene” xingwei yishu. But the landscape of tolerance in China has drastically altered. Although no artist I know of was legally convicted of violating the Ministry of Culture’s 2001 edict, it would be far more precarious today for xingwei artists to peddle—so to speak—their old, less than “true, good, and beautiful” trade with impunity. What can a creative individual do, facing certain danger and loss of all potential reward? “Be formless, shapeless, like water,” as martial artist/actor/philosopher Bruce Lee once advised (see Max Associates Reference Associates2013). Footnote 17 With patience and strategic resistance, be like water, working with and reshaping one’s environment. Not all artists need to be dissidents.

Somewhere between xingwei yishu’s erstwhile notoriety as “bloody, violent, obscene” and Xi’s dictates for art and other cultural products to be “true, good, beautiful” is the domestic territory for Chinese artists and nonartists to practice the ways (Dao) of water. This ideological context is the political impetus behind contemporary Chinese art’s “social and public turn.” Thus has xingwei yishu, or in its mundane—and not necessarily political—guise simply as xingwei/behavior, become a hybrid social art practice in China. As we’ve seen in the WPR protests, xingwei, in its down-to-earth, instrumental versions as civic behaviors, has been incorporated into China’s contemporary culture as a highly mobile, visible, adaptable, and potentially efficacious movement-vocabulary: a citable urban dictionary of repeatable/imitable behavioral phrases. You and I—and any individual with a will to publicly show some doing—can make and do xingwei.

Microperformances

My opening collage of exemplary protest scenes illustrates how xingwei/performance has served the White Paper Revolution as an expanding cultural lexicon of behavioral phrases, available to be imitated, replicated, and reassembled to raise awareness of any topic requiring political redress. I call these performative snippets that emerged from the WPR “microperformances”; with their dual nature as engaged politics and stand-out performance fragments, they have enriched the ongoing history of Chinese performance art. Footnote 18 While some of the microperformances have been created by artists, they existed primarily as scenes of civic insurgency within an explicit nonart context: in this case, the WPR. All microperformances—even when they were observed and documented in apparent isolation—participated in larger public demonstrations, employed by many others seeking similar political objectives. These microperformances therefore resemble deliberately incised performance tissue-samples, scrutinized under my critical microscope. Moreover, most microperformances were ultimately transmitted, shared, and circulated only as orphaned online images, extracted from their source performances, which can’t always be identified and never fully experienced by remote viewers.

My first sampled microperformance exemplifies the somewhat contradictory nature of the performance fragments as both confrontational and concealed: the woman in black, her mouth taped and hands bound by a metal chain, holds a stash of blank papers and walks slowly among pedestrians on a street (see fig. 1). Footnote 19 The woman’s microperformance appears more noteworthy for the compound references that her demeanor and gestures evoke than for their dramatic uniqueness. The defiant attitude revealed in her eyes, her behavior, and her props combines both restriction and resistance, and her choices of black and white colors in her costume—both associated with mourning in China—all become much more meaningful to viewers because they reiterate well-known cultural references as well as the specific and generic symbolism seen in other WPR protests.

Figure 1. Footage from Channel 4 shows the woman in black, in chains and holding a stack of white paper, walking on the street. “China Covid protests: police turn out in force to tackle ‘white paper’ movement,” YouTube, 28 November 2022; www.youtube.com/watch?v=xeIoezR_o5s. (Screenshot by author)

Figure 2. A crowd holding white papers, demonstrating in Beijing, China, 2022. The image was originally shared by @EMILYZFENG via Twitter and broadcast on PBS NewsHour. “Thousands in China protest zero-COVID policy in largest demonstrations in decades,” YouTube, 28 November 2022; www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrHdMMlvY8g. (Screenshot by author)

Figure 3. A crowd holding white papers, demonstrating in Chengdu, China, 2022. The image was originally shared by @FANGSHIMIN via Twitter and broadcast on PBS NewsHour. “Thousands in China protest zero-COVID policy in largest demonstrations in decades,” YouTube, 28 November 2022; www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrHdMMlvY8g. (Screenshot by author)

Figure 4. Wall Street Journal broadcast of Peng Lifa’s banners on Sitongqiao (2022). (Screenshot by TDR)

Figure 5. USC students demonstrating on a bridge in Los Angeles, led by graduate student Wang Han. Their banner has messages copied from Peng Lifa, the Bridge Man, in Beijing. The English translation for the Chinese subtitle in the screenshot reads: “To have the courage to express, to voice [dissent].” Broadcast by BBC News Zhongwen (反「清零」抗議潮:美國的中國留學生如何用行動聲援?Anti–zero Covid Protest Waves: How did US-based Chinese students use their actions to support the protest?) BBC News 中文, YouTube, 2 December 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=afogKHWoRcg. (Screenshot courtesy of author)

Figure 6. Peng Lifa’s TikTok profile picture, 2022, shared by China Change.

Figure 7. A Chinese student during a vigil at UCLA on 1 December 2022 apologized to Uyghurs for the CCP’s oppression. Uyghur American Association. @UyghurAmerican, Twitter, 2 December 2022. (Screenshot by author)

Figure 8. A crowd holding white papers demonstrating in Shanghai, China; broadcast on PBS Newshour in 2022. “Thousands in China protest zero-COVID policy in largest demonstrations in decades,” YouTube, 28 November 2022; www.youtube.com/watch?v=vrHdMMlvY8g. (Screenshot by author)

Figure 9. A woman in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, holding a blank white board in an antiwar protest, is escorted out by the police. Kevin Rothrock, @KevinRothrock, Twitter, 12 March 2022. (Screenshot by author)

Figure 10. The white-paper-covered performer on the UCLA campus, 2022. (Photo by Yancen Chen)

Figure 11. The white-paper-covered performer, assaulted by a figure wearing a Hazmat suit who sprays her with paint. The UCLA campus, 2022. (Photo by Yancen Chen)

Figure 12. The screenshot of the Winnie-the-Pooh Chinese Emperor, demonstrating with a white paper in a Global News clip, 2022. “Protests against China’s zero-COVID policy go global in show of solidarity,” YouTube, 28 November 2022; www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjRhpfIOUsQ . (Screenshot by author)

Figure 13. Xi and Obama paired with Winnie the Pooh and Tigger meme. Image shared to Twitter via @WhiteCurryLover. (Screenshot by TDR)

Figure 14. A Global News reporter (wearing mask) among protesters in China, 2022. “Protests against China’s zero-Covid policy go global in show of solidarity,” YouTube, 28 November; www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjRhpfIOUsQ. (Screenshot by author)

The performer’s taped mouth and chained wrists, signifying both enforced silence and oppressive bondage, specifically call to mind the horrendous Xuzhou chained woman incident, when a toothless woman named Xiao Huamei (小花梅), a mother of eight, was videotaped chained to the wall of a freezing shed, with a padlock on her neck. Footnote 20 The chained woman’s tragic life—when it first went viral on Douyin (抖音, Chinese TikTok) in January 2022—generated angry debate among Chinese netizens about domestic violence and human trafficking of women and children in China, especially in its rural regions and ethnic enclaves (see Zhou Reference Zhou2022). The woman in black essentially joined these debates by again bringing social awareness to the chained woman’s bondage; the performer further complicated her referential network by holding white papers with her chained hands, raising the specter of the Covid lockdown opposed by other white-paper-holding demonstrators. This microperformance posited a global analogy between Xiao Huamei’s cruel confinement and the confinement endured by Chinese citizens and residents for three years.

Even as she walked alone among unsuspecting pedestrians going about their daily business, the woman in black didn’t create her microperformance in isolation. Instead, her public demonstration imitated other politicized actions of the WPR. Having adopted the ubiquitous symbol of censorious blankness, the performer showed her political affiliation with other WPR demonstrators, paying tribute to her precedents; nevertheless, it would be difficult for us to ascribe her chosen prop to a singular origin. Some reporters traced the first appearance of the blank white paper in China to a masked student standing alone on the steps of the Communication University of China in Nanjing (see for example Pollard and Goh Reference Pollard and Goh2022). Yet, the alleged first user might have been inspired by the blank paper-wielding protestors in Hong Kong in 2020, after “the implementation of a national security law banning banners with slogans that criticize the government” (Chow Reference Chow2022). A similar protest symbol—a large blank white board—was used by an antiwar demonstrator in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, in early 2022 (see van Brugen Reference van Brugen2022; Rothrock Reference Rothrock2022). With the WPR microperformances, we have entered post-Duchampian cultural territory where the behavior of appropriation is a key strategy and the central protest object (a blank white paper) is both a readymade original and a copy. Each white paper is both repetitive and generative, an incipient point of departure and a destination; an interim path and a culmination.

If conceptually apt, analyzing the blank white A4 paper through the lens of Duchamp’s readymade is nevertheless emotionally tone-deaf. Duchamp described his “indifference” ([1961] 1996:819) in selecting an industrial product as a readymade while the woman in black and others use this common WPR symbol with zeal and political agency. I find it more pertinent to regard the blank white paper as a “disobedient object,” a curatorial concept exploring “the powerful role of objects in movements for social change” in a Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition (Victoria and Albert Museum 2015). This museum concept inspired a recent design research project organized by Yiying Wu and Karthikeya Acharya, who interviewed 42 Chinese citizens regarding their views on the significance of the “white paper” and asked them to create an artwork (a short story, a design artifact, a poem) capitalizing on “the potential and capability of ‘Blank’ to facilitate transformation and change” (Wu and Acharya Reference Wu and Acharya2023). Their surveys reveal two interrelated effects the white paper had on their respondents: it elicited anger against the pandemic policy and/or local governments’ enforcement measures; and frustration with the increasing censorship during the pandemic years. Provocatively, the 14 pieces of fiction created by 12 of the respondents were all “written like Aesop’s Fables to mock, criticize or exaggerate the censored society” rather than proposing a solution for a less-censored society (Wu and Acharya Reference Wu and Acharya2023). Rage breeds rebellion, which breeds protest, which breeds persecution, which breeds dystopia. In an authoritarian dystopia, only sardonic mockery and cynical humor are balms for festering wounds.

Dystopian thoughts and fabrications, which imagine an excess of despair to stave off one’s real-life impotence and depression, appear to be the prime motivation for using the blank paper as WPR’s disobedient object of choice. Consider my second sampled microperformance, enacted anonymously on the UCLA campus: The person in a white dress kneeling on the ground was further covered by white papers, layered to evoke a white veil and a white mail. With the raised white flower bouquet and her still, erect torso, the performer emulates the dual role of a supplicant and dissenter. The swift response to her silent supplication/dissent, however, was an aggressive denial, reinforced by the figure in the Hazmat suit (perhaps a Dabai [大白], Big white, a nickname for the Covid test enforcer) ceaselessly and excessively spraying what looked like chemical disinfectants on the dissident/supplicant-turned-victim/martyr. The pinkish red color drenching the kneeling figure may be read more than one way: its redness simulates blood, as a symbol of her persecution; its pinkish hue evokes the terror of xiao fenhong (小粉红, little pink), the young jingoistic Chinese nationalists and CCP loyalists who troll and bully suspected dissidents online. As a tableau of stoic resistance, the soaked kneeling performer emerges as a politicized emblem of WPR, pessimistically prefiguring the personal sacrifices awaiting protesters in China. The dystopian image embodied such a proximity to the real that there was no room for sarcastic humor.

“The effect of mimicry is camouflage” (in Bhabha Reference Bhabha1984:125). With this quotation from Jacques Lacan, Homi Bhabha launched his postcolonial analysis of mimicry as a performative tactic adopted by a colonized subject to deal with the colonizer. Reflecting the colonizer’s desire for “a reformed, recognizable Other,” colonial mimicry presents this seemingly assimilated Other as “a subject of a difference that is almost the same, but not quite” (125), “almost the same but not white” (130). Although Bhabha’s theory was developed against Britain’s historical colonization of India, his critique is presciently applicable to the ironic doubleness of WPR’s central symbolic object.

Perhaps it is counterintuitive to describe a blank white paper as “not white,” but Bhabha’s concept of colonial mimicry as a mimetic technique seasoned with mockery aptly explains how the blank page used in the WPR protests looks “almost the same, but not quite” the same as a white background with its previous content erased by censors, or a white screen with a 404 error code. Therefore, the central protest object—simulating blankness, anonymity, inscrutability, and dissent—coming out of the WPR is a product of mimicry, which camouflages itself as being empty of content so as to forestall state censorship. The WPR protesters sardonically employ self-censorship, making pieces of ordinary, mass-produced white paper mimic the effect of censorship, thereby preempting its political power to curb dissent. Freedom is the hidden code inscribed on this blank page and hope its invisible ink.

“The discourse of mimicry is constructed around an ambivalence; in order to be effective, mimicry must continually produce its slippage, its excess, its difference” (Bhabha Reference Bhabha1984:126). Seen as a performative mimicry, the ambivalence that Bhabha analyzes—a sense of rupture constructed through visual and auditory incongruity—aptly captures the oddity of a hybrid character, a Sinified Winnie the Pooh/Emperor, seen in my third sampled microperformance. Wearing a huge Winnie the Pooh head, a red cap with jewels resembling a crown, and an imperial yellow robe decorated with an ornate golden embroidery and red belt with jade pendants, the hybrid character in this WPR microperformance appears destined to elicit laughter. The cartoonish persona refers to a social media meme that emerged in 2013, when someone juxtaposed a photo of Xi and then–US President Obama walking side by side with an image of Pooh and Tigger (see Know Your Meme 2019). This comedic satire “prompted Beijing to censor the Chinese name for Winnie the Pooh and animated gifs of the chubby, somewhat dopey bear on social media platforms in 2017” (Romo Reference Romo2023).

By connecting Pooh with Emperor, while holding a blank piece of paper, the protester simultaneously restores a target of censorship (Pooh), repudiates the overwhelming state censorship in China (the symbolic A4 paper), and exposes Xi’s imperial ambition as the ruler of China for life (the Imperial attire). For me, the activist enclosed in this humorous body mask nevertheless breaks character by calling up the loss of freedom 30 years ago with my memories of the tragic Tiananmen massacre. Would the revolutionaries of the WPR suffer the same fate? The performer adopts a rhetorical mimicry that thrives on incompatibility, ambivalently vacillating between the visual hilarity of his cartoonish masquerade and the pathos of his message, reviving PTSD narratives of caution, mistrust, and cynicism.

My fourth sampled set of microperformances, with protesting crowds gathering in numerous Chinese cities and throughout its diaspora, add to the sardonic arsenal of performative mimicry. Imitating the CCP’s tongue to remind the powers that be of responsible governance, “serve the people” criticizes the regime’s current imperialist trends as betraying the people: a CCP-supported ascension of Xi Jinping as the presumptive supreme ruler for life that first became exposed by the Bridge Man’s dissident theatre on Beijing’s Sitongqiao.

Mimicry is a repetition that fractures its own façade of sincerity. In this light, mimicry is a mimetic technology that clones itself with a self-conscious smirk. Yet, as with other microperformance samples, the WPR has shown the world various imitation games, many of which offer an underlying, earnest political hope.

Repetition as imitation as solidarity: The WPR protesters often repeated certain rhetorical and performative practices (holding candles for vigils; placing white papers in front of their masked and capped faces as signs and shields; shouting similar slogans), freely imitating one another by using similar readymade protest objects (white A4 papers, hazmat suits, iPhone flashlights, flower bouquets), shouting the same slogans (“freedom,” “serve the people,” “give me liberty or give me death”), and behaving in like fashion (gathering in public places, milling around to evade police captures, sardonically taunting the authorities). The performative repetition has formed a dynamic behavioral aggregate, an inventory of cultural signs, references, movements, and codes, readily available to fellow protesters and their followers for further adoption and adaptation. Originality is not the point here; successive emulation in countless iteration is.

As performances of politics, the politics underpinning these microperformances accrue value in the repetitions and recurrences of certain choices the protestors make, including their attires, behavior, slogans, props, accessories, and settings. Theirs is a performative politics that gathers its power in numbers: the more WPR protesters mobilize in mass actions, the stronger their political impact; the more geographically widespread, the more impressive their democratic coalition; the more unified their political demands, the more forceful their movement becomes.

I realize that I have taken on a phantasmic present-tense to describe the historical eruptions of the White Paper Revolution in 2022. Perhaps this is my attempt to gesture hope and solidarity, enacted not so much because the WPR has definitively succeeded, but to project on the empty richness of a blank page. “White is not death,” as Wassily Kandinsky wrote, “It is the nothing before the beginning, the nothing before birth” (Kandinsky (1911) 2012; in Wu and Acharya Reference Wu and Acharya2023).

Hope is the midwifery that brings this nothingness to life in these creative movements, on the street and in the minds of the people.