The aging population is growing rapidly across the globe and Canada is no exception, with individuals 65 years of age and older projected to comprise 25 per cent of the Canadian population by 2050 (Guruge et al., Reference Guruge, Sidani, Wang, Sethi, Spitzer and Walton-Roberts2019). It is within this context that research into elder abuse and neglect becomes a pressing issue for scholars, social service providers, and policy makers to tackle. Elder abuse is widely recognized as a serious public health concern which requires urgent and immediate intervention (Pillemer, Burnes, Riffin, & Lachs, Reference Pillemer, Burnes, Riffin and Lachs2016; Walsh & Yon, Reference Walsh and Yon2012; World Health Organization, 2020). It is associated with major health consequences including physical and psychological morbidity, increased health care utilization, and premature mortality (Truong, Burnes, Alaggia, Elman, & Rosen, Reference Truong, Burnes, Alaggia, Elman and Rosen2019). The United Nations and other international alliances have underlined elder abuse as a violation of human rights and are calling for global action aimed at its prevention and legal reforms to control it (United Nations General Assembly, 2012; World Health Organization, 2020). The aim of this article is to analyze the available literature on elder abuse focusing on identifying the barriers that older adults experience when considering seeking help about their abusive situations.

Background

Reference to elder abuse within academic literature first appeared in the 1970s (Burston, Reference Burston1975; Lachs & Pillemer, Reference Lachs and Pillemer2015). Since then, there have been numerous attempts to define what elder abuse constitutes. The challenge exists in establishing a standard definition, given differences in cultural understandings of abuse, disagreements over the scope, and differing opinions among researchers (Fraga-Dominguez, Storey, & Glorney, Reference Fraga-Dominguez, Storey and Glorney2019; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2009). In spite of these debates, a widely accepted description refers to elder abuse as “a single or repeated act or lack of appropriate action occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust, which causes harm or distress to an older person” (World Health Organization, 2020, para. 1).

There are five commonly identified subtypes of elder abuse: (1) physical abuse, which consists of acts performed with the intention of causing physical pain or injury such as cuts, bruises, welts, or other physical harm; (2) sexual abuse, referring to non-consensual, threatened, or forced sexual activities or touching with older adults who do not provide willful consent or are unable to understand the situation; (3) psychological abuse, defined as actions intended to cause emotional harm or pain, including verbal assault, threats of abuse, intimidation, or harassment leading to feelings of hopelessness, fear, social withdrawal, depression, or anxiety for victims; (4) financial exploitation, which involves the misappropriation, theft, or withholding of an older adult’s resources including money or property, or changing legal documents to benefit a third party while disadvantaging the victim; and (5) neglect, referring to the failure by a caregiver in meeting the basic needs of a dependent person, particularly when done intentionally, such as withholding necessities including food, clothing, housing, medical care, and emotional support (Yon, Mikton, Gassoumis, & Wilber, Reference Yon, Mikton, Gassoumis and Wilber2017). Neglect may result in a senior’s being underweight or frail, having an unclean appearance, living in dangerous conditions, experiencing feelings of abandonment, and being deprived of dignity and respect (Dong, Reference Dong2015; Haukioja, Reference Haukioja2016; Lachs & Pillemer, Reference Lachs and Pillemer2004; World Health Organization, 2020). Some older adults may experience the co-occurrence of multiple forms of violence, referred to as poly-victimization (Fraga-Dominguez et al., Reference Fraga-Dominguez, Storey and Glorney2019; Truong et al., Reference Truong, Burnes, Alaggia, Elman and Rosen2019). Furthermore, abuse can occur in either domestic/community or institutional settings by perpetrators including spouses, children, grandchildren, or service providers (McDonald, Reference McDonald2011, Reference McDonald2018).

Elder abuse is recognized as a universal phenomenon that cuts across cultural and socio-economic lines (World Health Organization, 2020). In Canada, the prevalence rate of abuse amongst individuals 65 years or older ranges from 4 to 10 per cent (Ploeg, Lohfeld, & Walsh, Reference Ploeg, Lohfeld and Walsh2013; Podnieks, Reference Podnieks1992); with some rates reported to be as high as 22 per cent (Cooper, Selwood, & Livingston, Reference Cooper, Selwood and Livingston2008). A more recent national study by McDonald (Reference McDonald2018) reported prevalence rates at 8.2 per cent for elderly Canadians living in community settings. Prevalence rates vary by the subtype of abuse being measured, the setting in which the abuse occurs, and characteristics of the person experiencing abuse (McDonald, Reference McDonald2018). Elderly individuals presenting with a cognitive impairment, for example, had a higher prevalence of abuse, but this group was frequently excluded from prevalence studies given the difficulty of obtaining survey responses (McDonald, Reference McDonald2018). Moreover, only 4 to 15 per cent of victims personally report their experiences of elder abuse to formal service providers (Burnes, Breckman, Henderson, Lachs, & Pillemer, Reference Burnes, Breckman, Henderson, Lachs and Pillemer2019; Truong et al., Reference Truong, Burnes, Alaggia, Elman and Rosen2019). A report by the World Health Organization (2020) paints an even more dismal picture, indicating that only 1 in 24 cases of abuse are reported by older adults. For reasons such as this, it is predicted that the prevalence of elder abuse remains underestimated. It is now widely recognized that elder abuse is a hidden crisis that presents an enormous challenge in the provision of timely assistance to victims (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Breckman, Henderson, Lachs and Pillemer2019). The majority of elderly persons who suffer abuse endure it in isolation without external supports or intervention, and risk re-victimization.

There are many potential causes for low disclosure and help-seeking rates among those experiencing elder abuse. These range from the complex nature of perpetration and the role of family, coercion, and control (Wydall & Zerk, Reference Wydall and Zerk2017) to other issues such as a reluctance to utilize formal services (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Breckman, Henderson, Lachs and Pillemer2019). Help seeking is defined as an intentional or planned action undertaken by the person experiencing abuse to inform health providers, social services, or other third parties about their victimization (Cornally & McCarthy, Reference Cornally and McCarthy2011; Truong et al., Reference Truong, Burnes, Alaggia, Elman and Rosen2019). The process of help seeking is dynamic; the decision to seek help typically develops over time and is mediated by multiple factors that influence the elderly person’s actions (Truong et al., Reference Truong, Burnes, Alaggia, Elman and Rosen2019). Much of the data gathered about barriers to help seeking, however, come largely from the perspectives of health care professionals, other service providers, relatives, the general public, or hypothetical reactions to elder abuse vignettes rather than from the victim-survivors themselves (e.g., Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Breckman, Henderson, Lachs and Pillemer2019; Dong, Chang, Wong, & Simon, Reference Dong, Chang, Wong and Simon2014; Lee & Eaton, Reference Lee and Eaton2009; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Yoon, Shin, Moon, Kwon and Park2011; Lee, Moon, & Gomez, Reference Lee, Moon and Gomez2014; Moon & Williams, Reference Moon and Williams1993; Wydall & Zerk, Reference Wydall and Zerk2017). It is imperative to focus expressly on the perspectives of those experiencing elder abuse to effectively reduce barriers to help seeking and address the issue of under-reporting. In general, help seeking remains an underexplored area within elder abuse research (Fraga-Dominguez et al., Reference Fraga-Dominguez, Storey and Glorney2019).

Method

Scoping Review and Research Question

Scoping reviews are designed to rapidly map the broad themes, concepts, and gaps that emerge within the literature to provide an overview of a specific research topic (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) This article utilizes the five-step framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) for conducting scoping reviews, which proposes: (1) identifying a research question, (2) finding studies relevant to the research question through a literature search, (3) identifying a subset of studies to be included within the final review, (4) charting the data from the studies selected, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the final results.

This scoping review analyzes the existing literature on elder abuse, focusing specifically on the help-seeking behaviours of older adults living in community-based or institutionalized settings (e.g., long-term care, nursing homes). It is important to note that older adults residing in community-based settings experience abuse under conditions that differ significantly from those experienced by elders living in institutional settings. For example, in the community, abuse is more likely to be perpetrated by individuals belonging to a close network of kin or acquaintances, whereas in institutional settings, abuse is broadly grouped as staff-to-resident or resident-to-resident incidents (Yon, Ramiro-Gonzalez, Mikton, Huber, & Sethi, Reference Yon, Ramiro-Gonzalez, Mikton, Huber and Sethi2019). Nevertheless, studies conducted in both settings have been intentionally included in this review to capture a broad picture of elder abuse disclosure/help seeking and to reveal any potential gaps, patterns, similarities, or differences that may exist across both contexts.

The central research question guiding this analysis is: what are the barriers to help seeking experienced by older adult victims of abuse? The objective is to identify obstacles that older adults encounter when contemplating or attempting to seek help or when disclosing their abusive experiences to any third party (e.g., relatives, friends, medical staff, or support workers). This review and data synthesis seeks to inform policy makers, health care practitioners, and social service providers about key barriers faced by older adults and to encourage future research in this area. Moreover, the findings of this scoping review are situated within the Canadian context to specifically explore policy implications for the aging population in Canada.

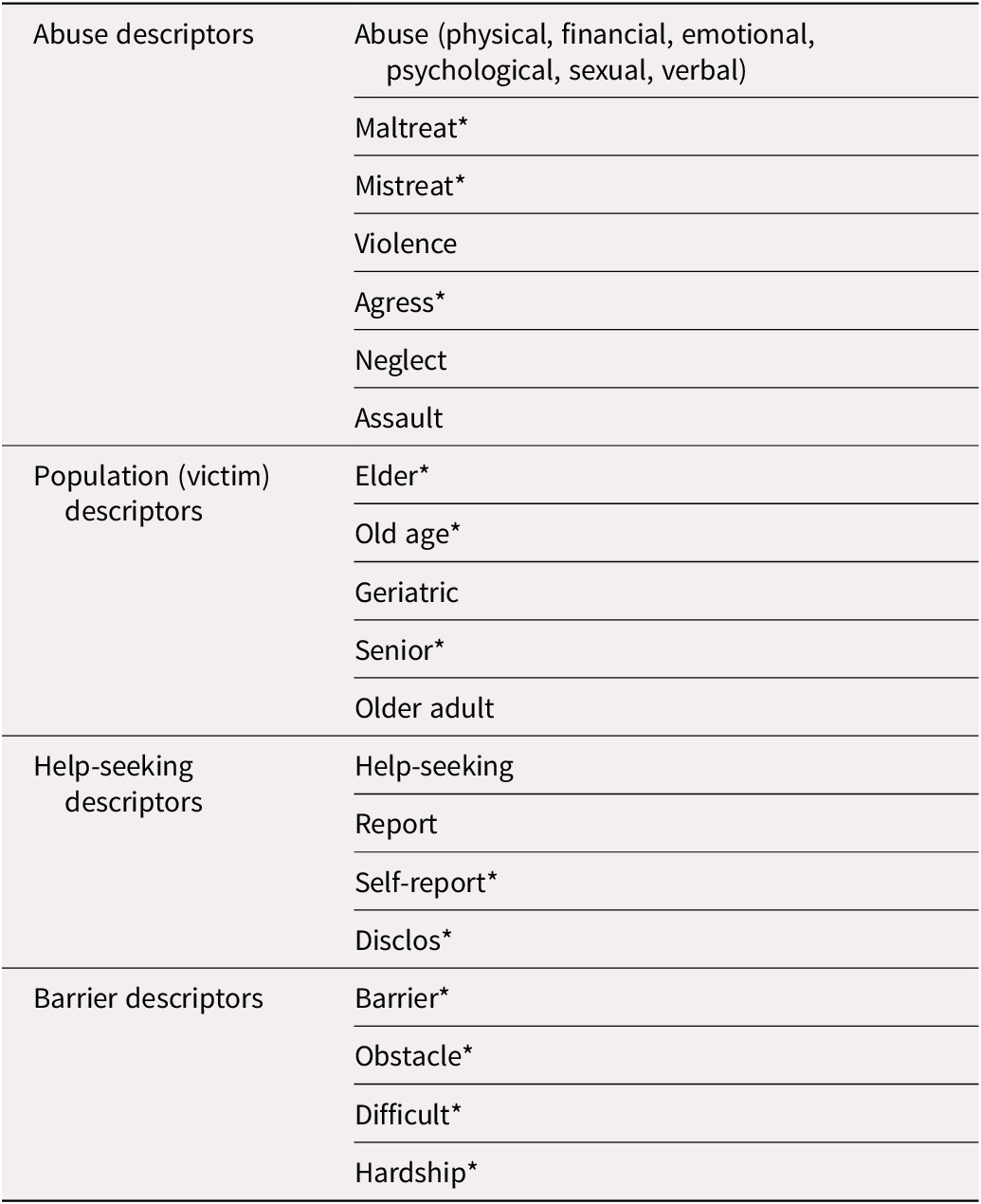

To begin the scoping review process, a search strategy was devised in which seven peer-reviewed databases were examined: PubMed/MEDLINE®, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), ProQuest, Sociological Abstracts, PsycINFO, and AgeLine. These databases were selected based on their overall comprehensiveness and relevance to the field of health, aging, and abuse. Each database was searched for all articles published over a span of 30 years, starting from 1990 up to and including October 15, 2019Footnote 1. The following search terms and their combinations were used in multiple database searches: keywords referring to abuse (e.g., maltreatment, neglect, assault, physical, mental, emotional, financial abuse); keywords referring to aging populations (e.g., elder, old age, senior, geriatric); keywords referring to help-seeking behaviours (e.g., help-seeking, reporting, disclosure); and keywords referring to barriers (e.g., obstacles, hardships, barriers)Footnote 2. Certain words were also truncated using an asterisk (*) to broaden the search results, such as in elder*. To ensure that each search query returned studies relevant to the research question, the keywords related to aging and abuse were required to appear within the abstract and/or title of each publication. Given the iterative and flexible nature of scoping reviews, publications were captured, reviewed, and analyzed throughout the research process, which ensured a deep and comprehensive search process (Arksey & O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For an article to be included in the final scoping review, both the inclusion and exclusion criteria had to be satisfied. These eligibility requirements were defined as follows.

-

• Article type: each article needed to be an original empirical study obtained from a peer-reviewed publication. Articles found within grey literature were excluded, along with any review articles, theoretical papers, book reviews, or editorials/commentaries.

-

• Study focus: articles that investigated the help-seeking behaviours of persons experiencing elder abuse were included in the review. More specifically, to qualify, data needed to be collected directly from the victim-survivors’ perspective (e.g., surveys, interviews, case analyses). Studies in which data about help seeking was collected from a third party, such as health care providers, relatives, or other non-victims, were excluded

-

• Population and sample characteristics: Research focused on victim-survivors 55 years of age or older were included. Studies which sampled from individuals under 55 years of age were excluded unless an explanation was provided for the lower-age cut-off (e.g., lower life expectancy because of low income or other determinants).

-

• Content: Only publications where a substantial focus was placed on elder abuse and help seeking or disclosure were included. Studies that only briefly discussed help seeking or that failed to highlight the older adult’s perspective were excluded.

-

• Language: Studies must have been published in English to be eligible. Articles published in other languages were excluded.

-

• Time period: Studies published between 1990 and 2019 were included. Those published outside of this range were excluded.

With regard to the focus of each study, this scoping review only included articles that were obtained from the victim-survivor’s perspective; any publications that sampled health care professionals, emergency response teams, or the general population and their perceptions of elder abuse were omitted. The decision to exclude non-victims was made intentionally in order to gather information specific to the standpoint of those experiencing abuse first hand. It is crucial to acknowledge the voices of victim-survivors, because they have a nuanced understanding of the complexities underlying their situations and better insight into their own actions, emotions, and thought processes (Hightower, Smith, & Hightower, Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006). It is well documented that the experiences of older adults are frequently neglected in research studies (Wydall & Zerk, Reference Wydall and Zerk2017). Incorporating the voices of traditionally underrepresented and marginalized groups, such as those experiencing elder abuse, can assist in establishing informed, evidence-based, and responsive recommendations to improve public health policy (Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006; Kirby, Greaves, & Reid, Reference Kirby, Greaves and Reid2010). This approach is a central aspect of feminist and participatory action research which seeks to empower and emancipate oppressed populations (Kirby et al., Reference Kirby, Greaves and Reid2010).

In reference to the age cut-off, most developed countries such as Canada define persons 65 years or older as “older adults” (Guruge, Birpreet, & Samuels-Dennis, Reference Guruge, Birpreet and Samuels-Dennis2015). However, life expectancy is shorter in certain low-income countries as a result of other disadvantageous circumstances; accordingly, the definition of “older adult” was expanded to incorporate a wider age range (Guruge et al., Reference Guruge, Birpreet and Samuels-Dennis2015). It should also be noted that within this scoping review, help seeking was conceptualized as the disclosure or reporting of abuse victimization by an older adult to at least one member in their informal or formal networks. Examples of disclosure include sharing personal experience of abuse with family members, friends, or acquaintances, or with professionals (i.e., social services, law enforcement, health care workers). These definitions and inclusion criteria form the parameters within which this scoping review was conducted.

Selection Process and Data Extraction

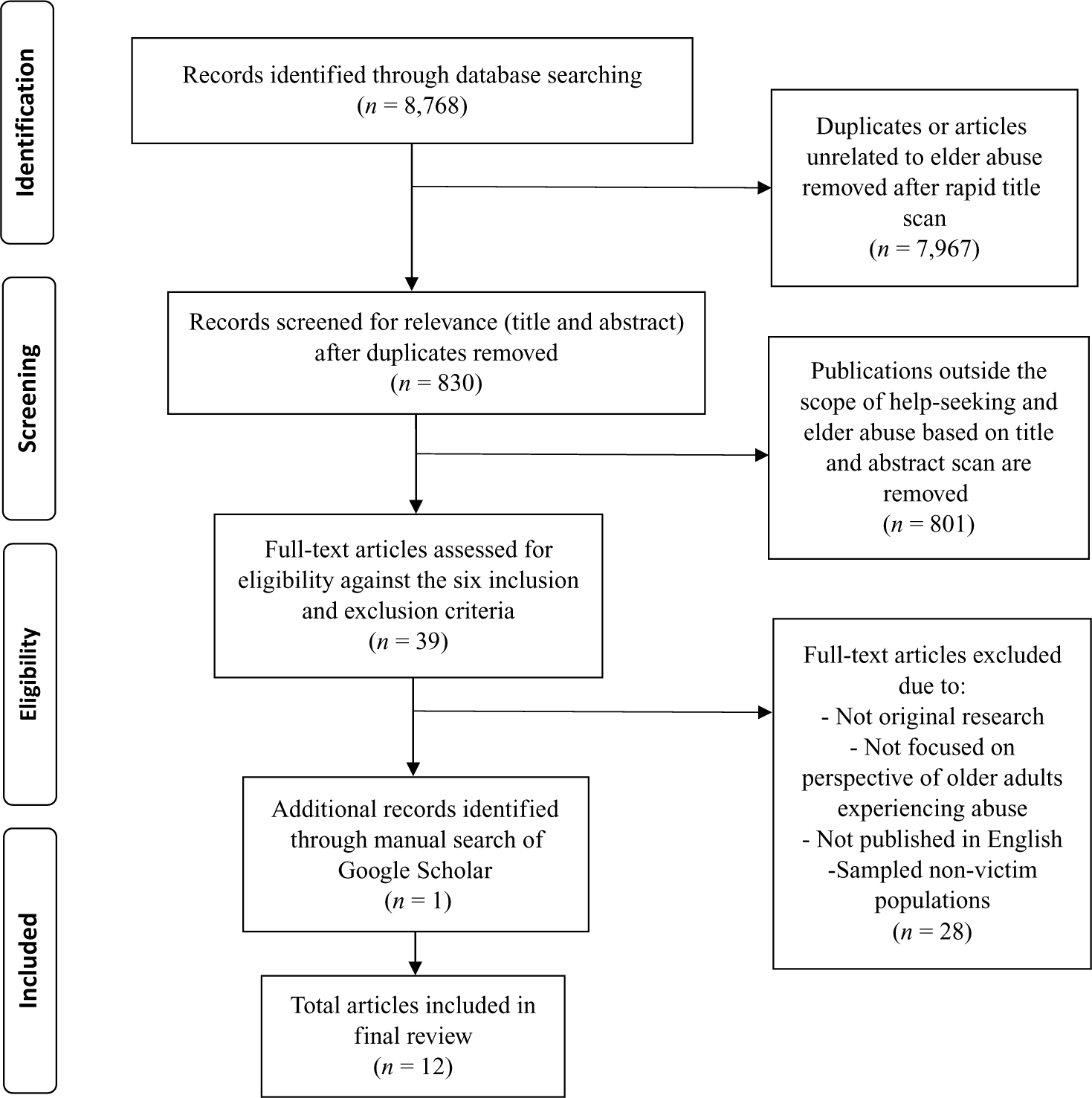

Multiple exhaustive searches of the databases were conducted by the author, which generated 8,768 publications (PubMed/MEDLINE®: 2132; Scopus: 1203; CINAHL: 1102; ProQuest: 1321; Sociological Abstracts: 1025; PsycINFO: 1075; AgeLine: 910). These references were uploaded into Mendeley Desktop (V-1.19.4) citation management system where the titles were scanned and filtered, removing duplicates or irrelevant publications. This preliminary extraction yielded 830 studies that were retained for further analysis through Rayyan QCRI—a Web application designed to assist in the completion of systematic reviews (Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid2016). For this screening phase, the publications were exported from Mendeley to Rayyan QCRI to expediate the title and abstract evaluation process using the tags and key term search options. The titles and abstracts were carefully read and assessed independently by one person, the author, looking specifically for the keywords identified in Table 1 and their combinations. Of these studies, 801 publications were eliminated because they did not focus primarily on help seeking or disclosure of elder abuse to a third party (e.g. addressed other aspects of abuse, risk factors/causes, and/or prevalence).

Table 1. Keywords used in the database searches

In the final selection phase, the remaining 39 studies were obtained in full text, read, and evaluated against the six inclusion and exclusion criteria. From these, 11 articles satisfied all of the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. One article that met the inclusion criteria was later found through a manual search of Google Scholar. Therefore, a total of 12 articles were included in the final analysis. A visual flow chart of this process is outlined in Figure 1 (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). The final set of publications was collated and charted in Microsoft Excel using the following headings: (1) author(s) and year of publication, (2) country of study, (3) research design, (4) sample information, (5) characteristics of abuser, and (6) main findings (see Table 2).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow chart of the search process (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009)

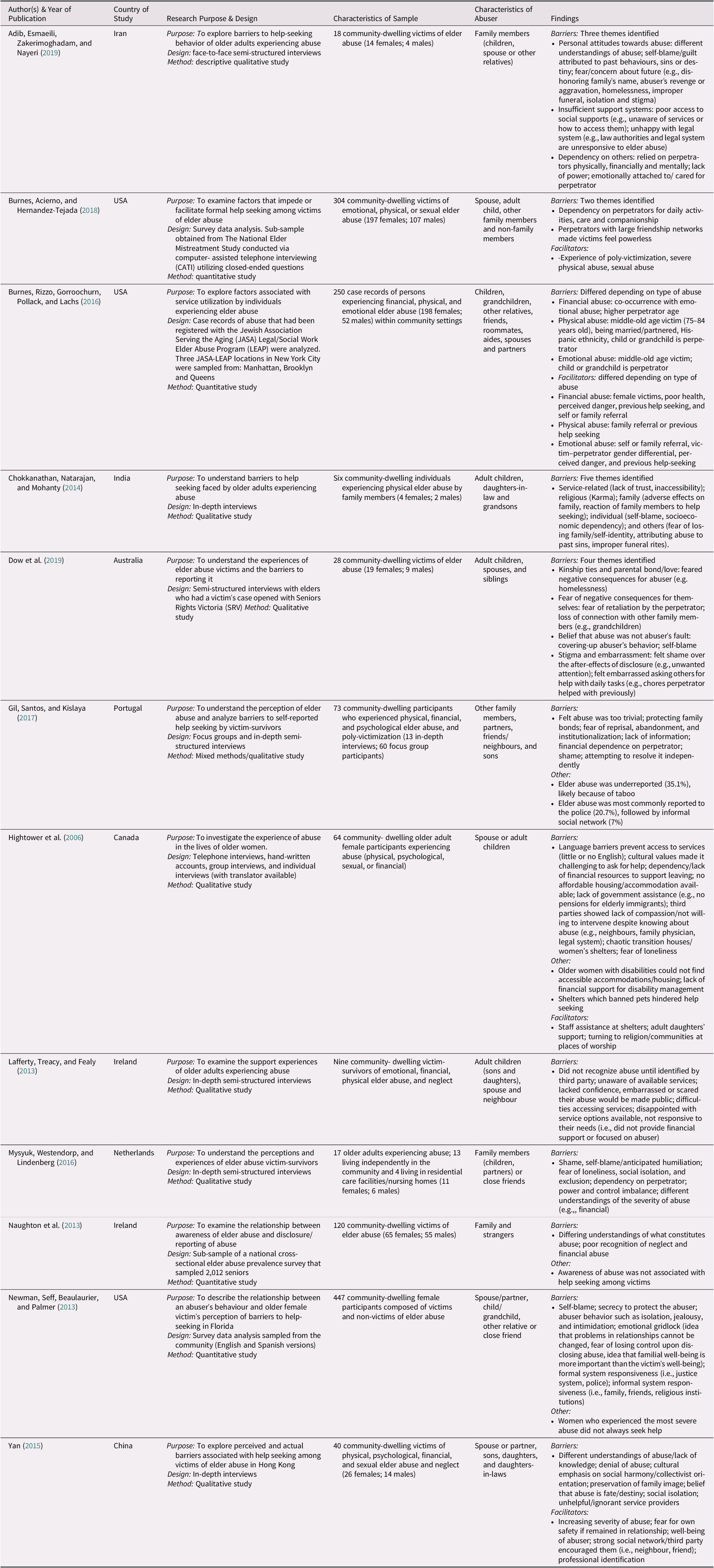

Table 2. Summary of the publications included in the final review

Data Synthesis

Data extraction was followed by a thematic synthesis of the information collected. This process was guided by the central research question, which aimed to identify barriers that older adults experience when contemplating or attempting to seek help in cases of abuse (Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010). Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) six-step framework for thematic analysis was used to synthesize key themes from each of the 12 studies included in the final scoping review. First, each publication was obtained in hard copy and actively read by the author multiple times to become familiar with the content. During each reading, special attention was paid to specific explanations, patterns, or commonalities between the barriers that each study revealed. Second, the author used multi-coloured highlighters, pens, and post-it notes to make annotations and manually generate an initial set of codes from each study. According to Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006), a code is a segment of the data which can be meaningfully assessed in relation to the phenomenon of interest (e.g., help-seeking, barriers). Once these initial codes were established, they were collated into a singular list using Microsoft Word. In the third phase, broad themes were formulated by organizing and grouping together codes that were similar or that shared an overarching relationship. In stages four and five, the author refined the themes by comparing them within and across the publications to inspect their accuracy and consistency. Finally, each established theme was appropriately named and defined.

Three themes and seven sub-themes were distilled from the 12 studies that most accurately captured the barriers to help seeking faced by older adults experiencing abuse. The three overarching themes were identified as: individual-focused barriers; abuser and family-focused barriers; and structural, community, and cultural barriers. During the reading and analysis of each publication, the author also gave particular attention to: the geographic location of each study, the methodological approach used to conduct the study (i.e. qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method), the sampling size and technique utilized, the specific characteristics of the included samples (age, sex, and dwelling type), and variations in the definition of elder abuse employed across studies. Evaluating and comparing the studies against these characteristics helped identify gaps or trends which could inform future research on elder abuse and help seeking.

Results

Characteristics of the Studies

Among the 12 publications included in the final analysis, most of the studies were conducted in the Unites States (n = 3; 25%) and Ireland (n = 2; 16%). The remaining studies took place across seven countries: Australia, Canada, China, India, Iran, The Netherlands, and Portugal. All of the selected studies explicitly examined barriers to help seeking amongst elders sampled from community-based settings. None of the publications focused primarily on older adults residing in long-term care homes, retirement residences, or other institutionalized care settings. One publication did have a small subset of participants (n = 4) living in residential care, although this distinction was not integral to the study (Mysyuk, Westendorp, & Lindenberg, Reference Mysyuk, Westendorp and Lindenberg2016). Finally, one publication was included that sampled from both victim and non-victim populations; however, in keeping with the outlined exclusion criteria, only the results focusing on the perceptions of the older adults who experienced abuse directly were analyzed in the review (Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier, & Palmer, Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013).

There was a range of methodologies used to conduct the studies. The majority employed a qualitative approach (n = 8; 67%). One of these studies drew its data from a mixed-methods analysis that used in-depth interviews, focus groups, and a large-scale population-based survey to determine the prevalence of aging and violence in Portugal; however, only the qualitative results were included in this scoping review because they focused specifically on barriers to help seeking (Gil, Santos, & Kislaya, Reference Gil, Santos, Kislaya, Husso, Virkki, Notko, Hirvonen and Eilola2017). Most of the qualitative studies used in-depth interviewing techniques to better understand the victim-survivor experiences of abuse, and some also combined these interviews with focus group discussions.

The remaining studies utilized a quantitative approach (n = 4; 33%), that drew on data sources such as: national cross-sectional population-based surveys, quantitative case analyses, and community-based surveys (Burns, Acierno, R., & Hernandez-Tejada Reference Burnes, Acierno and Hernandez-Tejada2018; Burnes, Rizzo, Gorroochurn, Pollack, & Lachs, Reference Burnes, Rizzo, Gorroochurn, Pollack and Lachs2016; Naughton, Drennan, Lyons, & Lafferty, Reference Naughton, Drennan, Lyons and Lafferty2013; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013). The quantitative studies used statistical analysis to describe trends within the data collected and to establish associations between certain variables and help-seeking behaviours. Two of the quantitative studies were part of larger projects focused on identifying the prevalence of elder abuse in the national population (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Acierno and Hernandez-Tejada2018; Naughton et al., Reference Naughton, Drennan, Lyons and Lafferty2013).

Sample sizes of victim populations range from 6 (Chokkanathan, Natarajan, & Mohanty, Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014) to 447 participants (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013). With regard to the age of the samples, most studies set the age cut-off at approximately 60 years, with participants ranging in age from 60 to 90 years. Only two studies utilized a reduced age cut-off of 50 years (Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013). The reason provided for the lower cut-off by Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013) was that this age group (50–60-year-olds) was under-served by both elder abuse and domestic violence services, which created a gap in provision of adequate support, hence the goal was to capture whether this had an impact on help-seeking behaviours. Likewise, Hightower et al. (Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006) explained that women 50–60 years of age who attempted to escape their abusive situations and gain independence were more likely to experience employment difficulties as a result of ageist attitudes, but were simultaneously deemed too young for certain state-governed financial supports (e.g., Old Age Security). To capture the effect of this disadvantage on help seeking, the age cut-off was lowered. Therefore, given that both studies focused on the victim-survivor’s perspective and discussed barriers to help- eeking, the author deemed that they should be included in the final analysis.

Conceptualization of elder abuse varied slightly across the publications. There was a general consensus that it included a single or repeated intentional act that caused harm, risk of harm, or distress to an older adult, or involved the failure by a caregiver to meet the older adult’s basic needs and to protect them from harm. Most articles specified the subtypes of abuse experienced by the participants sampled within each study (i.e., physical, financial, psychological, or neglect). All 12 sources focused on abuse committed by someone in a relationship of trust; for example, a spouse, adult children, siblings, other relatives, or friends. Only one study (9%) also included abusive incidents committed by a stranger against older adults (Naughton et al., Reference Naughton, Drennan, Lyons and Lafferty2013). Alhough there was no singular definition of help seeking across the studies, it was commonly described as the disclosure or reporting of the abuse to a third party, such as health care personnel, police, service workers, family, friends, or other acquintances Some definitions were broader, such as disclosure to anyone, whereas others were more specific, such as reporting to formal authorities (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Acierno and Hernandez-Tejada2018; Chokkanathan et al., Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014).

Barriers to Help Seeking

Each of the 12 studies identified through the scoping review examined a variety of barriers to help seeking among individuals experiencing elder abuse. To present the findings in a comprehensive and organized manner, the barriers were grouped together thematically. Each theme presents a substantial barrier which was identified across multiple studies during the thematic analysis process. Three overarching themes and seven related subthemes were discovered, and are discussed in order of prominence within the literature:

Individual-focused barriers

One of the broad themes identified was individual-focused barriers to help seeking. The barriers clustered under this theme focus on the victim-survivor’s: (1) level of dependency; (2) fear, shame, and personal well-being; (3) understandings of self-blame, destiny, and fate; and (4) awareness of abuse. In general, this set of barriers encompassed personal constraints, hesitations, and internalized thoughts that impeded attempts to seek help or disclose abuse to a third party.

Dependency

An older adult’s dependence on the abusive perpetrator was identified as a major barrier to help seeking in 10 studies (83%). Increased dependency on the abuser was associated with a significant decrease in help-seeking attempts and delayed the reporting of abuse to third parties (e.g. friends, family, support and health care workers) across all 10 publications. In the literature, dependency was conceptualized in both functional and financial terms. Functional dependence was defined as the inability of an older adult to self-reliantly perform activities of daily living, as a result of physical or cognitive limitations, therefore requiring the assistance of the abuser to fulfill these needs (Adib, Esmaeili, & Zakerimoghadam, Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019). Financial dependence was identified as an older adult’s reliance on the abuser for money, shelter, food, clothes, or other resources for survival. Both forms of dependency resulted in a loss of autonomy for persons experiencing elder abuse; many doubted their own ability to survive without the perpetrator’s support (Mysyuk et al., Reference Mysyuk, Westendorp and Lindenberg2016). This power imbalance between the abuser and victim became a barrier to disclosure.

Financial or socio-economic dependency on adult children or a spouse, in particular, was reported as a pernicious roadblock to reporting abuse, and resulted in a greater risk of abuse in general (Adib et al., Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019; Chokkanathan et al., Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014). Prevalence of abuse was also higher for elders living in lower socio-economic or materially deprived neighbourhoods, which may be related to the financial dependence of victims on their abusers in these communities (Naughton et al., Reference Naughton, Drennan, Lyons and Lafferty2013). Burnes et al. (Reference Burnes, Acierno and Hernandez-Tejada2018) found that older adults who were in a dependent relationship were less likely to view their mistreatment as problematic; sometimes even engaging in the practice of “tacit exchange” in which abuse was traded for perceived benefits such as care, ability to stay in the community, and companionship with the abuser (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Acierno and Hernandez-Tejada2018).

Fear, shame. and personal well-being

A second set of barriers identified in the included literature was the fear of disclosing abuse (n = 9; 75%), particularly: the fear of negative consequences; fear of embarrassment or of personal issues becoming public; and, generally, a fear for the future. The fear of experiencing negative consequences of disclosure was a central concern. Persons experiencing abuse expressed that they were frightened for their safety, particularly fear of aggravating the perpetrator and the risk of retaliation by the abuser (Naughton et al., Reference Naughton, Drennan, Lyons and Lafferty2013). This was closely related to the fear of an insecure future. For example, Adib et al. (Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019) found that elderly persons were concerned about being dishonored, abandoned, and being denied a deserving funeral after their passing if they were to report their abuse victimization. Others were afraid of being placed in institutional settings or feared creating familial rifts amongst their adult children; these concerns served as major obstacles to disclosure (Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006).

Finally, the fear of embarrassment, stigma, and shame was identified as a key factor that prevented individuals from seeking help for their abuse. This included the shame of requesting supports for financial losses accrued because of the abuse, or asking third parties for help with daily tasks that the perpetrator had originally helped with (Dow et al., Reference Dow, Gahan, Gaffy, Joosten, Vrantsidis and Jarred2019). Another source of embarrassment was the idea that the abuser’s personal matters would be made public. Many seniors felt ashamed about the responses that they might receive from others upon disclosing their experience of being subjected to abuse (Lafferty, Treacy, & Fealy, Reference Lafferty, Treacy and Fealy2013). Maintaining secrecy about the abuse was seen as the optimal solution to avoiding these internalized fears (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013).

Self-blame, destiny, and fate

The third theme that emerged was related to older adults’ faulting or accusing themselves for the abuse they were experiencing, which delayed reporting. Seven (58%) of the studies reviewed found that self-blame was a prominent issue. Self-criticism and blame were associated with feelings of decreased self-worth and negative self-evaluation (Chokkanathan et al., Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013). Persons experiencing elder abuse oftentimes began to believe that their abuse was too trivial to report (Gil et al., Reference Gil, Santos, Kislaya, Husso, Virkki, Notko, Hirvonen and Eilola2017). Many older adults found it difficult to accept that trusted individuals would hurt them, which resulted in the idea that, perhaps, they themselves were to blame for the abuse (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013).

Chokkanathan et al. (Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014) examined two types of self-blame in their article: behavioural and characterological. Behavioural self-blame was defined as the attribution of negative events to one’s own modifiable behaviour, thus allowing space to alter personal behaviour to appease the abuser and avoid negative future events (Chokkanathan et al., Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014). Characterological self-blame, in contrast, was even more insidious as it referred to the attribution of negative events to unmodifiable personality characteristics or other deficiencies within the older adult being subjected to abuse. This resulted in the flawed perception that the abusive situation was uncontrollable and that the victim was at fault (Chokkanathan et al., Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014). All six of the participants interviewed by Chokkanathan et al. (Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014) expressed characterological self-blame, justifying their own victimization by attributing it to their unproductiveness, failing health, and overall frailty.

Related to the concept of self-blame was the idea that the abuse was fate or destiny; this barrier was evidenced in two studies (Adib et al., Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019; Yan, Reference Yan2015). Older adults who felt that abuse was destined and inevitable often cited bad karma, an unlucky life trajectory, and atonement for past sins as justification for the abuse (Adib et al., Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019; Yan, Reference Yan2015). This perception sustained victims’ belief that abuse was inescapable and preordained, which therefore prevented active help-seeking behaviours. Newman et al. (Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013) referred to this feeling of powerlessness and helplessness as “emotional gridlock”, whereas Mysyuk et al. (Reference Mysyuk, Westendorp and Lindenberg2016) referred to it as a “learned helplessness”.

Awareness of abuse

A final individual-focused factor which determined help-seeking behaviours was the older adult’s understanding of abuse and the ability to recognize it within their own context. Five (42%) studies highlighted that abuse recognition influenced an individual’s decision to seek help; however, some studies were not conclusive. For example, Naughton et al. (Reference Naughton, Drennan, Lyons and Lafferty2013) found that the general awareness of the term “elder abuse” was not associated with higher levels of disclosure to a third party; however, the severity and type of abuse being experienced did influence help seeking. For example, Naughton et al. (Reference Naughton, Drennan, Lyons and Lafferty2013) found that 72 per cent of individuals who experienced physical or sexual assault sought help, but that only 60 and 50 per cent sought help for financial and psychological abuse, respectively. Neglect was also less likely to be recognized as abusive. Hightower et al. (Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006) found that older adult women were less likely to recognize violent acts as abusive when their spouse was the perpetrator. Moreover, poly-victimization or continuous and repetitive abusive behaviours increased the likelihood of reporting and disclosure of abuse (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Rizzo, Gorroochurn, Pollack and Lachs2016). In fact, those experiencing poly-victimization were four times as likely to seek help, suggesting that most individuals wait until abuse is severe before disclosing it to a third party (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Acierno and Hernandez-Tejada2018).

Abuser, family, and immediate social network-focused barriers

The second overarching theme that was identified in the scoping review was barriers associated with the abuser, family members, and the elderly person’s immediate social circle. The literature indicates that perpetrators are frequently in a relationship of trust with the victim, such as spouses, adult children, grandchildren, friends, or others belonging to the older adult’s proximate social network. Given the interconnectedness of these relationships, codependent barriers to help-seeking emerged.

Protection and fear of losing connection

A central barrier that was mentioned across 11 (92%) of the articles was the desire of the older adult victim to protect their family or the abuser from potential harm that could arise from reporting abuse. Gil et al. (Reference Gil, Santos, Kislaya, Husso, Virkki, Notko, Hirvonen and Eilola2017) reported that elderly persons had a particularly difficult time disclosing abuse when it occurred within the nuclear family or between spouses. Similarly, Burnes et al. (Reference Burnes, Rizzo, Gorroochurn, Pollack and Lachs2016) noted that female victims of elder abuse were more likely to avoid reporting abuse in order to “protect their offspring from involvement with social service or legal-justice systems and reluctant to accept interventions that threaten core family relationships” (p. 1051). Chokkanathan et al. (Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014) found that parental responsibility, feelings of guilt, desire to protect their abusive children from negative consequences, and the fear of being placed in institutionalized care prevented those experiencing elder abuse from seeking help. A similar sentiment was evidenced in Dow et al. (Reference Dow, Gahan, Gaffy, Joosten, Vrantsidis and Jarred2019) who found that older adults experiencing abuse were afraid of their children becoming homeless, especially when the abuser was cohabiting with their parents. Adib et al. (Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019) discovered that older adults did not report their abuse because they were afraid of being abandoned by their own families; this was especially true when the abuser was a family member. Many individuals experiencing elder abuse were also afraid of losing contact with the perpetrator, who was frequently an individual that the victim cared about deeply (Mysyuk et al., Reference Mysyuk, Westendorp and Lindenberg2016).

Structural, community, and cultural barriers

The third broad thematic area that emerged from the scoping analysis focused on barriers within the community, at the state level, or related to religious and cultural beliefs. The barriers in this theme move beyond individual-level explanations, expanding into wider structural difficulties that persons subjected to elder abuse may face when contemplating or attempting to seek help.

Issues with elder abuse services

The literature revealed that there was a general lack of awareness, or ignorance, about available support services; poor service accessibility; and an overall sense of disappointment in the quality of these services (n = 7; 58%). Lafferty et al. (Reference Lafferty, Treacy and Fealy2013) found that persons experiencing abuse were unaware of the local services that were available to support and protect them from being mistreated. Respondents shared that they were only able to connect to services after a third party, such as a neighbour, directed them to the source, or when they had viewed promotional advertisements about the services on television (Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, Treacy and Fealy2013). Moreover, certain individuals lacked the confidence to access these support services (Chokkanathan et al., Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014; Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, Treacy and Fealy2013). In other studies, it was found that third parties, including friends and family physicians, were reluctant to get involved, even though they knew about the abusive situation (Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006; Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, Treacy and Fealy2013).

Accessibility was another critical obstacle to help seeking. For example, limited service availability (e.g., timings) and physical barriers to access (e.g. lack of transportation) were reported as deterrents (Adib et al., Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019). Language barriers also affected access to support services. For example, Hightower et al. (Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006) found that persons with little or no command of English had a difficult time finding resources available in their native language. Likewise, respondents indicated that few support services were culturally sensitive, which was a hurdle for many new immigrants experiencing elder abuse (Dow et al., Reference Dow, Gahan, Gaffy, Joosten, Vrantsidis and Jarred2019; Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006). Older adults with disabilities faced a unique set of obstacles when contemplating abuse disclosure, such as the possibility that their needs may not be appropriately accommodated if they left their abuser (Adib et al., Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019; Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006). Burnes et al. (Reference Burnes, Acierno and Hernandez-Tejada2018) noted a shortage of home care services which disabled individuals experiencing elder abuse could use (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Acierno and Hernandez-Tejada2018). Finally, inadequate or inaccessible financial supports (e.g. government pensions) coupled with unaffordable housing and living expenses served as a major barrier to help seeking (Adib et al., Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019; Dow et al., Reference Dow, Gahan, Gaffy, Joosten, Vrantsidis and Jarred2019; Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006).

Chokkanathan et al. (Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014) noted that in addition to issues with access and poor awareness of services amongst individuals experiencing abuse, there was also a sense of mistrust and hesitation. Many older adults feared that the service providers would inform their abuser or family members about their complaints. Respondents also shared a sense of frustration with the service staff who, victim-survivors felt, were ill-trained and inept in understanding elder abuse (Chokkanathan et al., Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014). As a result, there was a general cynicism attached to the outcomes of help seeking from formal services, in which older adults felt that reporting would only exacerbate the abuse or force restrictions on their movement outside of the home (Chokkanathan et al., Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014). The participants surveyed in the study by Adib et al. (Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019) echoed similar feelings of disappointment with the legal system and police responders, stating that elder abuse was not taken seriously enough.

Cultural beliefs

The final structural barrier that was found to influence an elderly person’s help-seeking behaviours was cultural values (n = 6; 50%). This barrier particularly influenced the way victims thought about their self-image, their communities, and their families. Yan (Reference Yan2015), for example, found that the traditional Chinese value of social harmony prioritized family goals and interests over those of the individual. This concept is prominent in cultures characterized by a collectivist orientation. Yan (Reference Yan2015) noted that amongst older adults holding this view, such those as in China and the Asian subcontinent, family members were expected to sacrifice their own needs for the sake of preserving relationships and the social unit. Any family problems were expected to be kept within the family circle because sharing them with the outside world would bring shame, dishonour, and embarrassment to all members of that family. This expectation for older adults to keep the family together, thus, prevented individuals from leaving abusive situations and seeking help.

A similar pattern was observed in Adib et al. (Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019) where it was found that in traditional Iranian culture, family integrity held more weight than personal wishes, which discouraged victims from reporting abuse. The results from the study in India by Chokkanathan et al. (Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014) found the same pattern, with family honour taking priority over individual needs. The adherence to traditional values of social conformity, harmony, and family honour, therefore, decreased the chances that older adults would seek help for abuse. Interestingly, it was found that religiosity served both as a barrier to and facilitator of help seeking for situations of elder abuse. For example, individuals who followed religious doctrines that praised the endurance of hardship in exchange for divine rewards were less likely to seek help for abuse (Adib et al., Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019). However, in other cases, the sense of community felt within a religious congregation provided some older adults with comfort and safety from the abuse (Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006). Overall, as highlighted previously, difficulty accessing culturally competent services deterred individuals from disclosing abuse (Dow et al., Reference Dow, Gahan, Gaffy, Joosten, Vrantsidis and Jarred2019).

Discussion

In this scoping review, empirical findings were gathered from the scholarly literature and synthesized to reveal barriers that individuals confront when contemplating seeking help for elder abuse. The results of the review found that older adults experiencing abuse encounter several layers of barriers across multiple contexts: (1) individual-focused barriers, (2) abuser and family-focused barriers, and (3) structural, community and cultural barriers. These findings demonstrate that obstacles exist at all levels, thus shifting analysis away from purely individualized explanations which allude to victim-blaming, towards examining broad structural barriers that prevent older adults from seeking help. More specifically, barriers were found to exist at three levels relative to the older adult, ranging from internalized obstacles, external-proximal challenges, and broad socio-structural barriers which were systemic in nature. The most prominent barrier to help seeking was the desire of the older adult to protect their family or the abuser from harm, which appeared in 11 of the publications included in the review. This was followed closely by the older adult’s own dependence on the abuser for survival. The fear of retaliation and of personal safety was the third most prominent barrier to help seeking. Poor accessibility and awareness of support services were also noted as substantial impediments to disclosure.

In addition, women were observed to be over-represented amongst all study samples included in the review. This trend aligned with prior research showing that older women experience greater abuse victimization than men, on average (Lachs & Pillemer, Reference Lachs and Pillemer2015). The majority of studies included in the current review did not specifically differentiate between the help-seeking or disclosure behaviours of women versus those of men, nor were results explicitly stratified by sex. However, several studies did include discussions of the gendered experience of elder abuse. For example, Chokkanathan et al. (Reference Chokkanathan, Natarajan and Mohanty2014) noted that older women living in joint families frequently experienced abuse for incomplete household chores, whereas older men faced abuse for incomplete tasks outside of the home. Similarly, Yan (Reference Yan2015) noted that elderly women were at a higher risk of experiencing sexual abuse than their male counterparts. Finally, Burnes et al. (Reference Burnes, Rizzo, Gorroochurn, Pollack and Lachs2016) found that older women were less likely to report abuse, in order to protect their families. Two studies included in this review did focus solely on women’s experiences of abuse, which provided an insightful look at help-seeking behaviours from the specific perspective of older women (Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013). One such finding indicated that older adult women were more likely to rely on their adult daughters for help when attempting to escape from abusive situations (Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006).

The results from this scoping review are corroborated by the findings from a similar systematic literature review conducted by Fraga-Dominguez et al. (Reference Fraga-Dominguez, Storey and Glorney2019) on elder abuse and help-seeking behaviours. In their analysis, Fraga-Dominguez et al. (Reference Fraga-Dominguez, Storey and Glorney2019) looked at both barriers to and facilitators of help-seeking. They noted that victims attempting to seek help found support from within their social networks; however, any attempts to seek help were not always immediate and usually occurred after a prolonged period of abuse, oftentimes being prompted by fear for personal safety. Furthermore, paralleling the findings in this review, abuse which was perpetrated by a family member was the most difficult to report and was a major barrier to disclosure. The current study extends the results of Fraga-Dominguez et al.’s (Reference Fraga-Dominguez, Storey and Glorney2019) article by providing an in-depth analysis of specific barriers to help seeking and further by aiming to contextualize these results within the Canadian context.

The current study identified three key themes and seven subthemes of barriers. As was expected, the literature used in the current study had some overlap with that included in the systematic review by Fraga-Dominguez et al. (Reference Fraga-Dominguez, Storey and Glorney2019); however, the current review includes six unique publications which were not utilized in their article (Adib et al., Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019; Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Rizzo, Gorroochurn, Pollack and Lachs2016, Reference Burnes, Acierno and Hernandez-Tejada2018; Dow et al., Reference Dow, Gahan, Gaffy, Joosten, Vrantsidis and Jarred2019; Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013). The differences in the publications extracted in both studies is perhaps a result of: variations in the databases used; discrepancies in the search terms, and their combinations, applied; differences in the eligibility criteria; and the disparities in the time frames of both studies (database search ending on July 5, 2018 for Fraga-Dominguez et al. vs. ending on October 15, 2019 for the current article). Based on these important distinctions, it can be concluded that the current study offers a unique and innovative set of results that can be used to inform public health policy in the area of elder abuse.

Limitations

There are three key limitations to this review. First, only scholarly and peer-reviewed publications were considered for inclusion in the analysis. Therefore, grey literature, such as government documents, working papers, reports from non-governmental organizations, conference proceedings, program evaluations, or other independent studies focusing on elder abuse were not included. Although the decision to exclude grey literature is potentially restrictive, it was a critical step to ensure that the rigor, quality, and ethical standards of the included studies were maintained at a high level.

Second, because this review is bound by the eligibility criteria, any relevant studies outside of the criteria were inadvertently excluded. For example, only studies in English were included. As such, potentially relevant materials written in other languages and published in non-English-speaking countries could have been excluded. Likewise, any study published outside the 1990–2019 time frame were also excluded. Establishing clear eligibility criteria was a necessary step in controlling the volume of materials and maintaining a focus on research-oriented studies. Finally, despite best efforts made by the author to ensure a comprehensive examination of the literature, there is a possibility that certain publications that indirectly discussed barriers to disclosure and help-seeking (e.g., did not use the keywords identified in Table 1) could have been unintentionally eliminated.

Gaps within the Literature: A Call for Future Research

This scoping review revealed several gaps in the literature regarding elder abuse and barriers to help seeking. Future research could offer important contributions in these key areas. The first major gap identified was the absence of studies focused on participants residing in institutionalized care, retirement residences, or long-term care homes. All of the publications included in the current review sampled primarily from within the community. It should be noted, however, that barriers to disclosing abuse may differ considerably in assisted living or institutional contexts for several reasons. For example, in community settings, the perpetrator is generally known to the person being abused, whereas in institutionalized settings abuse is more likely to occur at the hands of staff or professional health care workers, a difference which could impact whether an older adult chooses to disclose their experiences of abuse to a third party (World Health Organization, 2020). Likewise, the type and frequency of abuse experienced across institutional and community-based settings varies; with physical abuse reported as more prevalent in institutions, as compared with higher rates of financial abuse within the community, factors which may differentially impact help-seeking behaviours in both settings (World Health Organization, 2020; Yon et al., Reference Yon, Mikton, Gassoumis and Wilber2017, Reference Yon, Ramiro-Gonzalez, Mikton, Huber and Sethi2019). Individuals living in institutionalized settings also tend to be older, lack social supports, and have more physical or cognitive limitations and acute health issues; potentially making it more difficult to seek help for abuse than it is for community-dwelling older adults (Garner, Tanusputro, Manuel, & Sanmartin, Reference Garner, Tanusputro, Manuel and Sanmartin2018). Finally, social services available to seniors living in community settings are funded and regulated by different governmental departments than are services for those living within institutional care, resulting in variations in the types of support services accessible to both populations (Norris, Reference Norris2020). Given these differences, the results from the current study cannot be generalized to institutional settings; therefore, further research is needed to effectively characterize barriers to older adults’ abuse disclosure within residential care.

Second, as mentioned in the previous section, few studies focused on understanding whether help seeking and disclosure were statistically mediated by sex differences. None of the studies included in the final review stratified their results by sex, nor did any publication offer a comparative analysis of the barriers to help-seeking encountered by older adult men, women, or any other gender. The implications that these differences could have on service provision is significant, and warrants a deeper analysis. Future research in this area could shape how services are designed, advertised, and delivered in more effective and responsive ways. There have been publications that focused specifically on older women’s experiences of help seeking (Hightower et al., Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Seff, Beaulaurier and Palmer2013); nevertheless, an analysis of barriers which takes into consideration the diverse gender and sexuality spectrum would offer the critical insight needed to further research on help seeking and elder abuse.

A third gap identified was in relation to older adults with disabilities. How did disability status affect barriers to help seeking? Although it can be argued that the experiences of persons with a disability may have been subsumed under the theme of dependency on the abuser, there were few studies that explicitly addressed the obstacles to help seeking experienced by disabled older adults. Only Adib et al. (Reference Adib, Esmaeili, Zakerimoghadam and Nayeri2019) and Hightower et al. (Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006) offered a discussion of disability and help seeking, noting that disability deterred persons from disclosing abuse. However, a more in-depth analysis of this relationship would be beneficial. Similarly, future research should pay closer attention to the geographic barriers to accessing services, particularly examining how help seeking differs across rural versus urban settings.

A final gap that emerged during the scoping review was the lack of research focusing on elder abuse and barriers to help seeking conducted in the Canadian context.Although there have been several Canadian studies focusing on elder abuse in general (McDonald, Reference McDonald2011, Reference McDonald2018; Podnieks, Reference Podnieks2008; Walsh & Yon, Reference Walsh and Yon2012), there have not been many Canadian studies conducted to date that focus specifically on the victim-survivor’s perspective of help seeking. Hightower et al. (Reference Hightower, Smith and Hightower2006) was the only Canadian study that explored barriers to help seeking in older adult women. The remaining publications analyzed in the current study spanned eight countries. In order to form a more comprehensive picture of the barriers to reporting abuse, it is essential for Canadian researchers and policy makers alike to focus on this under-explored area. The results of the current study do offer a set of important conclusions which can be extrapolated to the Canadian context as well. The following section explores several policy recommendations and extant programs in Canada that have focused on mitigating barriers to help seeking.

Implications for the Canadian Context

Public health policies in Canada must invest efforts into spreading awareness of elder abuse among older adult populations, health care professionals, service providers, and the general public. The scoping review revealed that many elderly persons experiencing abuse were uninformed about what constituted abuse and its subtypes (Dow et al., Reference Dow, Gahan, Gaffy, Joosten, Vrantsidis and Jarred2019). Certain subtypes of abuse were less likely to be recognized by older adults, such as financial and psychological abuse and neglect (Naughton et al., Reference Naughton, Drennan, Lyons and Lafferty2013). Likewise, the analysis revealed that some individuals lacked knowledge about the services available to support them (Lafferty et al., Reference Lafferty, Treacy and Fealy2013). Finally, Dow et al. (Reference Dow, Gahan, Gaffy, Joosten, Vrantsidis and Jarred2019) highlighted that services and public health initiatives needed to adopt more culturally sensitive frameworks that were responsive to the needs of a diverse aging population. Keeping these barriers in mind, elder abuse awareness campaigns in Canada should be designed in ways that are readily accessible to everyone in the general population.

Podnieks (Reference Podnieks2008), for example, discusses a promising Canadian pilot project called Generations Together: Addressing Elder Abuse, funded by Justice Canada and the National Crisis Prevention Centre. This project focused on spreading awareness of elder abuse across generations and educating youth against negative stereotypes of older adults (Podnieks, Reference Podnieks2008). It encouraged young Canadians to critically analyze the risk factors of elder abuse and has led to the formation of several other intergenerational initiatives focused on raising awareness about elder abuse among children and youth in Canada (Podnieks, Reference Podnieks2008; see Elder Abuse Prevention Ontario, 2021). Social media platforms, such as Twitter and Instagram, for example, have served as important spaces for intergenerational engagement whereby collaborative virtual awareness campaigns developed by various governmental agencies and non-governmental organizations, including #UprootElderAbuse, #WEAAD (i.e. World Elder Abuse Awareness Day occurring on June 15th, annually), and #IGDayCanada (i.e. Intergenerational Day which takes place yearly on June 1st), have become springboards for on-line and off-line conversations about recognizing and preventing elder abuse nationwide (Elder Abuse Prevention Ontario, 2021)

Deploying educational training and awareness campaigns that target professionals, especially health care workers, appears to be one of the best intervention strategies for tackling the under-reporting of elder abuse (Wang, Brisbin, Loo, & Straus, Reference Wang, Brisbin, Loo and Straus2015). Because health care professionals are frequently in contact with older adults outside of immediate social circles, they occupy a unique position for identifying cases of abuse and for understanding the benefits of reporting to authorities (Storey & Perka, Reference Storey and Perka2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Brisbin, Loo and Straus2015). Seniors themselves rarely report their experiences of abuse to social service organizations, with an even fewer number officially reporting to the police (Storey & Perka, Reference Storey and Perka2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Brisbin, Loo and Straus2015). What complicates the reporting process further is the fact that elder abuse in Canada is managed differently across each province and territory. Certain jurisdictions only legally obligate professionals to report abuse, or mandate reporting in cases in which abuse is occurring within institutionalized care settings; while other provinces encourage the general public to report any suspected case of elder abuse (see Canadian Centre for Elder Law, 2011). Further, public awareness of these laws also remains limited. Irrespective of the jurisdictional differences, the general trend towards under-reporting of abuse by older adults indicates the importance of strengthening networks among community-based social services, health care workers, non-profit networks, the justice system, and advocacy groups, to spread awareness of and improve responses to elder abuse across Canada (Storey & Perka, Reference Storey and Perka2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Brisbin, Loo and Straus2015).

Currently, there exist elder abuse networks which are non-governmental non-profit organizations that function in an advisory capacity to develop region-specific interventions for elder abuse (Podnieks, Reference Podnieks2008, Reference Podnieks and Shankardass2020). These networks were established in the 1980s and 1990s; beginning as small-scale grass-roots initiatives which united like-minded individuals concerned with rising rates of elder abuse in both community and institutional settings. These networks later expanded across the country under the umbrella Canadian Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse (CNPEA), comprising professionals, researchers, volunteers, seniors, and other organizations (Podnieks, Reference Podnieks2008, Reference Podnieks and Shankardass2020). CNPEA have curated a website (www.cnpea.ca) which acts as a national hub for collaboration, government lobbying, and resource sharing (Canadian Network for Prevention of Elder Abuse, 2020; Podnieks, Reference Podnieks and Shankardass2020). An example of a provincial network is Elder Abuse Prevention Ontario (EAPON—www.eapon.ca), which similarly functions to engage all levels of government, the public, and professionals in responding to elder abuse by supporting more than 57 regional elder abuse prevention networks across Ontario with advocacy, training, knowledge mobilization, and a current directory of services for help seekers (Elder Abuse Prevention Ontario, 2020; Podnieks, Reference Podnieks and Shankardass2020).

More recently, work by the National Initiative for the Care of the Elderly (NICE), a network of Canadian and international researchers, students, and practitioners, has worked to tackle the issue of elder abuse through knowledge translation. Founded by Lynn MacDonald and located in Toronto, Ontario, NICE has created and distributed evidence-based and interdisciplinary resources about the detection and prevention of elder abuse to frontline responders, stakeholders, and caregivers (e.g., The Brief Abuse Screen [BASE] diagnostic tool) (Podnieks, Reference Podnieks and Shankardass2020). Many of their digital tools have been made freely available in multiple languages on their Web site. Further, they have designed free informational workshops (e.g., Turning Senior Voices into Action) to spread awareness about elder abuse. Finally, NICE has worked to establish key community connections and a helpline for persons experiencing abuse to seek assistance (e.g., Talk2Nice Community Outreach services). Information about NICE and their initiatives can be accessed online at: www.nicenet.ca (National Initiative for the Care of the Elderly, 2020).

Strengthening these networks with additional funding and expanding their initiatives to reach elderly populations and the general public through strategic advertisements and digital expansion would allow older adults and their social networks to better understand the definition of elder abuse, recognize abuse, and access available services to support individuals experiencing mistreatment and abuse. Particular attention must also be paid to the needs of Canada’s diverse population when devising future initiatives and policy agendas. This focus would ensure the suitability, accessibility, and inclusivity of elder abuse support programs. Stakeholders must be cognizant of the specific needs of marginalized groups, including: sexually and gender diverse populations, persons with disabilities, Indigenous populations, those living in rural areas, and individuals facing linguistic or cultural barriers to access, thus allowing for more responsive recommendations to be developed. Furthermore, future initiatives should seek to establish inclusive and safe environments where victim-survivors are not afraid of disclosing their abuse.

An example of a Canadian victim-centered initiative is the Elder Abuse Resource and Support Team (EARS), founded by Catholic Social Services in Edmonton, Alberta. The focus of this intervention program is to empower older adults experiencing abuse by assigning them a case worker who provides individualized support (Fraga-Dominguez et al., Reference Fraga-Dominguez, Storey and Glorney2019; Storey & Perka, Reference Storey and Perka2018). EARS is the longest-running community-based intervention program for elder abuse and a first of its kind, showing great potential for expansion across Canada (Storey & Perka, Reference Storey and Perka2018). Programs with a similar framework to EARS have already started to appear in several regions, including: Elder Abuse Response Team (EART) in Calgary, Alberta; Elder Abuse Response and Referral Service (EARRS) in Ottawa, Ontario; and Senior Support Team (SST) in Waterloo, Ontario (Carya, 2020; Elder Abuse Prevention Council, 2020; Kerby Centre, 2020; Nepean & Osgoode Community Resource Centre, Reference Nepean2020). With the growth of targeted programs and networks, it is evident that significant progress has been made in addressing elder mistreatment in Canada since the 1980s. However, moving forward, the federal government must focus its attention on establishing a comprehensive and cohesive national strategy that addresses elder abuse respectively across both community-based and institutional settings (Podnieks, Reference Podnieks and Shankardass2020). As this scoping review demonstrates, there is an urgent need for a strategy that explicitly tackles each of the individual, group, and structural barriers to help seeking experienced by an intersectionally diverse population of older adults.

Conclusion

This scoping review aimed to provide a better understanding of the barriers to help seeking that older adults experience when attempting to report or disclose their abuse to a third party. Using Arksey and O’Malley’s (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) scoping review methodology, 12 publications were extracted from the scholarly literature, focusing only on those studies that sampled from the perspective of the victim-survivor. Next, Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) thematic analysis framework was used to synthesize and identify key barriers from the selected literature. The analysis resulted in the emergence of three thematic areas in which barriers to help seeking exist, namely: individual-focused; abuser and family-focused; and structural, community, and culture-focused barriers. The results indicated that barriers to disclosure exist at all levels. This finding helps move the conversation about elder abuse towards tackling broad group and structural-level obstacles to help seeking and away from victim blaming.

The publications provided important and unique insights into the help-seeking behaviours of older adults experiencing abuse. An important limitation identified in the available literature was the absence of studies conducted in the Canadian context. Drawing on relevant literature, the author suggested that Canadian health policies focus on creating programs and initiatives that would raise awareness about the prevalence and definition of elder abuse among health care professionals and in the general population. The second recommendation was to ensure that social services are culturally sensitive and victim centered, ensuring a safe and inclusive space to disclose abuse victimization. Further research needs to be conducted that focuses particularly on the voices of elder abuse victims in the Canadian context. Policy makers and social service providers would benefit from the knowledge available by applying it in their policies and practice. Finally, it is imperative that the Canadian government establish a comprehensive federal strategy to tackle elder abuse on a national scale, in order to effectively respond to the needs of victim-survivors.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Weizhen Dong, Associate Professor at the University of Waterloo, for inspiring this project and for her insights during the writing of this manuscript. This work would not have been possible without the support of the University of Waterloo’s Sociology and Legal Studies Department. Finally, the author expresses sincere gratitude to Dr. Deborah van den Hoonaard and the two anonymous reviewers for taking the time to read and review this manuscript; their constructive feedback helped to improve it immensely.