Introduction

According to Jonathan Spencer, European anthropology (also called ethnology and ethnography) “shares an intellectual history with nationalism” (Spencer Reference Spencer, Barnard and Spencer2010, 497). At its beginnings lies the romantic legend of folk roots of the “nation,” inspired, like nationalism, by the ideas of Johann Gottfried Herder. Pre-scientific, and later scientific, ethnographic research on the culture of non-elite groups of European societies (Völkerkunde), evolving since the time of the Enlightenment, supplied knowledge which was used in nationalistic discourse and as a source of legitimacy of national ideologies and both types of nationalism:Footnote 1 “polity-seeking or polity-upgrading nationalism that aims to establish or upgrade an autonomous national polity; and polity-based, nation shaping (or nation-promoting) nationalism that aims to nationalize an existing polity” (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 79).

Similarly, in the interwar period, new nationalizing states, including Poland, which came into being after the fall of three European empires, used ethnological knowledge, expertise, and institutions to construct nationalistic discourse, legitimize nationalistic claims, and support nationalistic policies. Suffice it to mention the performative power of ethnographic, ethnolinguistic, and ethno-geographic maps, as well as ethnicity statistics, which served as a foundation for the discourse of “national interest,” with its focus on “ethnographic masses,” constituting “material,” either for “nationalizing” or “awaking from national slumber” (Górny Reference Górny2014, 126–170).

The anthropologists themselves often employed nationalist discourse, taking it as a socio-cultural given. They did not question the category of “nation,”Footnote 2 nor did they attempt to deconstruct it. The majority of anthropologists at the time shared the widespread, essentialist assumption that “nation” is a perennial entity an sich, in itself, as well as the belief in a natural connection between the “nation” and its culture within its territory. The role of anthropologists, including Polish ethnologists, in laying the foundations of nationalistic discourse is undeniable: “they imposed nationalistic categories on a rich and varied cultural reality” (Kubica Reference Kubica2020, 153).

The question of the complex and changing interdependencies between Polish anthropology and Polish nationalism with their converging or competing discourses, however, has not yet garnered substantial attention and still awaits its monographer. Over the past couple of years, only a handful of articles devoted to this subject appeared. A general overview of the development of Polish ethnography/ethnology/anthropology in the context of the evolving and consolidating ethnic nationalism is given by Michał Buchowski in his synthetic essay on the history of anthropology, from the beginning of the 19th century until the present day (Buchowski Reference Buchowski and Buchowski2019). Buchowski consistently shows that, in Poland, this discipline developed under the influence of both scientific and nationalistic forces, and that “whether they were aware of this or not, many scholars participated in nation-building” (Buchowski Reference Buchowski and Buchowski2019, 11). “Yet even if they were agents for the nationalist cause” – he concludes – “they were not really any different from Western empire-building anthropologists, who were accused of being agents of colonialism” (Buchowski Reference Buchowski and Buchowski2019, 37).

A more detailed enquiry into this issue in the interwar period was undertaken by Olga Linkiewicz and Grażyna Kubica. Linkiewicz’s research is focused on the interlinkage of scientific ideals, professionalization of ethnology, and its political involvement in interwar Poland against the backdrop of national mobilization of the period (Linkiewicz Reference Linkiewicz2016b). She also analyzes the public status of the expert in social sciences and physical anthropology in the context of a transnational exchange of knowledge and experience on the one hand, and the driving force of nationalization and politization on the other (Linkiewicz Reference Linkiewicz2016a, Reference Linkiewicz, Cain and Kleebergforthcoming). Kubica, in turn, using the example of two prominent Polish ethnologists, Jan Stanisław Bystroń and Bożena Stelmachowska, shows how “the scholarly authority of Polish ethnographers served to consolidate nationalist discourse even when they were critical of it” (Kubica Reference Kubica2020, 135). Analyses of the role of ethnographic knowledge in constructing the Polish “nation” and Polish nation-state in the interwar period, as well as of the interdependence of nationalism and social sciences, can also be found in historical monographs of the period; however, they do not focus on the discipline of ethnology (Ciancia Reference Ciancia2021; Górny Reference Górny2014, Reference Górny2017).

This article attempts to analyze – based on three representative examples – the interdependencies between Polish anthropology and the politics of the nationalizing Polish state, or, in other words, the subordination of the scientific field to the state and its administrative field in 1930s Poland. According to Pierre Bourdieu, intellectuals – hence also scholars – are “a dominated fraction of the dominant class” (Bourdieu and Wacquant Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992, 104–105). Anthropologists, as well as other agents of the field of science, are dependent both on the power play within the field itself and the influence of the political, administrative, and economic fields in particular. On the other hand, “the scope of the scientific field [is particularly interesting], for it constitutes a social microcosm, provided with the strongest autonomy and the most specific structures” (Lebaron Reference Lebaron2017, 6). In particular, I will focus on the question of how and to what extent the political and administrative strategies and practices of Polish nationalizing state influenced research autonomy of anthropologists at the time. To answer this question, I will analyze three case studies depicting different habitus, cultural/social capitals, trajectories, and choices of actors of the social microcosm of Polish ethnology, which at that time was already a well-established discipline, subsidized, although relatively modestly, by the state.

The historical context of my analysis is the sociopolitical reality of the Second Polish Republic, i.e., the interwar Polish state existing from 1918 to 1939. The year 1918 marks the turning point from polity-seeking Polish nationalism to one which creates discourse and political practices of a new state – a “‘nationalizing’ nationalism within the framework of an existing state” (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 82). In this new Poland, which emerged after over 120 years of partitions when its territory was divided between Russia, Prussia, and Austria, although national minorities accounted for some 30% of the country’s population, the dominant culture and political decisionmakers promoted the concept of a “nation” based on the identity of a Pole-Catholic, i.e., not a paradigm based on multicultural citizenship, but an ethno-religious one, to the exclusion of the Other. “The new Polish state […] was conceived as a state of and for the ethnolinguistically (and ethno-religiously) defined Polish nation, in part because it was seen as made by this nation against the resistance of Germans, Ukrainians, and Jews. A clear distinction was universally drawn between this Polish nation and the total citizenry of the state” (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 85). As a result of the institutionalization of power in the new state, those who were previously dominated (by foreign powers) now became the dominating ones. It was a nationalizing state in the full meaning of the term, in which, in the words of Rogers Brubaker, “the core nation is understood as a legitimate ‘owner’ of the state,” and the state’s power is used “to promote the specific […] interests of the core nation” (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 9, 5). The state’s allies in promoting these interests were to be, among others, ethnologists.

This peripheral young state, which, in many respects, was still pre-modern and facing grave economic difficulties and social conflicts, ceased to be a democracy after a military coup in 1926, when it became a military and police dictatorship (so called Sanacja [Sanation]), drifting toward a fascist model in the late 1930s (although the political scene still remained complex in certain aspects). On the other hand, the social energy of citizens creating the ideology and institutions of the young state led to a rapid advance in social sciences and the humanities. Ethnology, present in Poland already since the first decades of the 19th century, was at that time subjected to the processes of professionalization and institutionalization. In the 1920s, departments of ethnology (or ethnography) were being established at universities, with their overall number reaching seven in 1939.

The ethnological community, attracting academics and a sizeable group of ethnographic curators, maintained scientific contacts with sociologists and representatives of other social sciences active in the scientific field at home and abroad. Moreover, the strengthening of the discipline itself promoted diversity in the adopted theoretical approaches and improvements in the overall quality of ethnological work, which was being conducted by a growing number of knowledgeable, internationally trained, multilingual, and sophisticated researchers (Buchowski Reference Buchowski and Buchowski2019, 17–18). The ethnological subfield, as all fields of social sciences at the time, constituted a relatively complex scene, with scientific disputes as well as methodological, personal, and political controversies playing their respective parts.

The ethnologists were primarily part of the local field of social sciences, constituting “the constellation of scientific ideals, the professionalization of social sciences, and the political entanglement of scholars” (Linkiewicz, Reference Linkiewicz, Cain and Kleebergforthcoming). A vital activity in this field was the work of experts, for it constituted the answer of learned professionals to state demand, ever-growing in the 1930s, for modern applications of social sciences.Footnote 3 As part of state-funded research programs and institutions, ethnologists and other specialists delivered the requested expertise and arguments serving, for example, to further the polonization of national and ethnic minorities (Grott Reference Grott2013; Kubica Reference Kubica2020; Linkiewicz Reference Linkiewicz2016a; Reference Linkiewicz2016b, Reference Linkiewicz, Cain and Kleebergforthcoming).

All three researchers who constitute the focus of this paper – Stanisław Dworakowski, Joachim/Chaim Chajes and Józef Obrębski – belonged to the same generation. Born in the first decade of the 20th century as citizens of the partitioning states (Russia in the case of Dworakowski and Obrębski and Austria in the case of Chajes), they obtained higher education already after 1918 in the independent Polish state. All three were professionals, graduates of the newly established ethnological departments. Only Obrębski was educated both in Poland and abroad. As a fellow of the Rockefeller Foundation, he became a student and research assistant to Bronisław Malinowski, who, in turn, was his doctoral advisor. Chajes, despite the lack of formal education abroad, maintained academic contacts with scholars outside of Poland (with leading folklore centers in Switzerland, Finland, Estonia, and the Soviet Union), due to his position as the secretary to the Ethnographical Commission of the Yiddish Scientific Institute (YIVO) in Vilnius.

All three researchers had solid fieldwork experience as well. They were talented and skillful ethnographers. Obrębski was the only one among the three who conducted his own fieldwork outside of Poland, in the Balkan states. In their domestic fieldwork, they all chose a similar destination: the eastern regions of the Polish state, densely inhabited by East-Slavic national minorities and Jews. Obrębski and Dworakowski were active in the Polesie region among Orthodox, Belarusian-, and Ukrainian-speaking peasants; Chajes in the Carpathian Mountains among Greek-Catholics, Ukrainian-speaking highlanders, and their Jewish neighbors, as well as in the Jewish village of Laybishki in the Vilnius Region. In addition, Chajes archived and elaborated the data sourced from hundreds of amateur collectors, thus having daily contact with field material from hundreds of Jewish communities dispersed in the area of the whole country and beyond.

All three of them published, delivered academic lectures, and popularized the field of ethnology. When it comes to institutional affiliations, however, only Dworakowski had stable, long-term employment in the Warsaw Scientific Society, a community institution financed from state subsidies. Obrębski only obtained a state position three years before the outbreak of the war: he became a deputy director of a newly established scientific and research institution, the National Institute of Rural Culture, which was intellectually and organizationally dominated by a community of innovative qualitative sociologists, students of the anthropologically minded Florian Znaniecki. Previously, as a “freelance intellectual […] encamped on the margins or in the marginalia of an academic empire” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Collier1988, xix), he was affiliated with different institutions, carrying out a large, state-funded research project and giving lectures. The situation of Chajes was the most difficult and least stable one. After leaving YIVO in about 1934, he was unemployed and earned a living from temporary jobs.

Unlike their decade-and-a-half older colleagues, Jan Stanisław Bystroń and Bożena Stelmachowska, whose journalistic writing, entangled in nationalistic discourse, was analyzed by Grażyna Kubica, none of the three scholars presented in this article took part in public debate. Their work cannot thus be perceived in terms of engaged or public anthropology (Kubica Reference Kubica2020, 136–138) – although both Obrębski and Dworakowski were active in the field of applied anthropology, “supplying the authorities […] with knowledge facilitating governing over ‘natives’” (Kubica Reference Kubica2020, 137) or, in other words, in “the field of think tanks, constitutionally committed to generating useful knowledge for external actors” (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2016, 104).

Our three anthropologists reached academic maturity and, for better or worse, achieved professional positions on the eve of World War II. Still relatively young at the time, they could be “defined above all negatively, by their lack of institutionalized signs of prestige and by the possession of inferior forms of academic power” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Collier1988, 79). The war disturbed or interrupted their careers and, in one case, life.

Two of them belonged to the dominating majority in the country: Dworakowski and Obrębski were Poles, nominally Catholics, although we know that the latter was an agnostic. Chajes belonged to the Jewish minority, subjected to systematic violence and exclusion by the Polish state. The political, social, and cultural situation of the East-Slavic minorities, which was their subject of research, was also far from privileged at the time. These minorities were subjected to linguistic and religious polonization and discriminated against on the economic and social plane. They were subjected to a policy of assimilation whose goal was to transform them into an ethnoculturally Polish “nation.” In the words of Brubaker, “while it was widely believed that […] Jews should not be assimilated, the assimilation of Belarusians and Ukrainians was seen as both possible and desirable, even as necessary” (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 100). Jews, conversely, were the subject of anti-assimilation efforts:Footnote 4 “If nationalizing policies and practices vis-à-vis Jews sought in the short term to exclude them from the professional and commercial economy, the long-term aim was to promote Jewish emigration […] Governmental nationalization from above was complemented by extragovernmental nationalization from below” (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 97, 96).

Case 1. From Ethnographer to a Propaganda Man. Stanisław Dworakowski (1907–1976): Scholar at the Service of a Nationalizing State

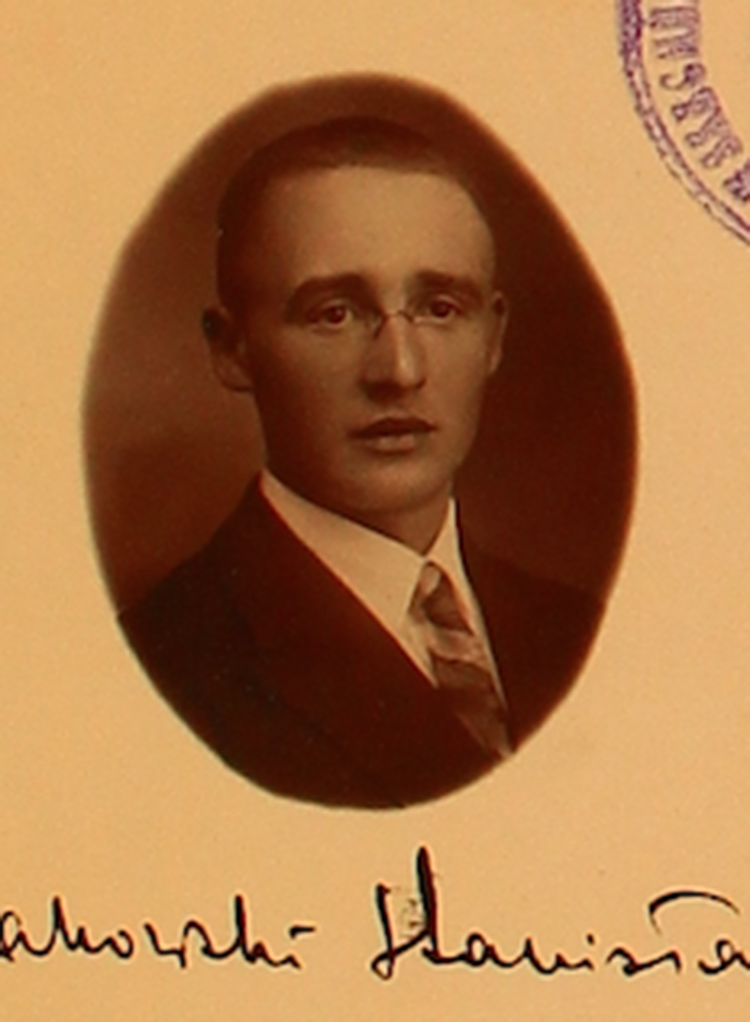

Stanisław Dworakowski came from a petty nobility family from a village in the Łomża province (today’s northeastern Poland) (see figure 1). His father had a farm of about 50 hectares. A substantial part of inhabitants in the region were petty nobility, attached to the catholic-national ethos, and at the same time there was growing support for nationalistic organizations, including the fascist National Radical Camp (ONR).Footnote 5 Brought up in the tradition of patriotism and the struggle for Polish independence, Stanisław was the first child in the family to receive higher education. Any direct statements of his political views are not known; in postwar personal questionnaires, he declared political inactivity before the war.Footnote 6 One can assume from his postwar fate that he was not a supporter of the new regime introduced in Poland after the country was incorporated (as the Polish People’s Republic) into the Soviet bloc.

Figure 1. Stanisław Dworakowski (1907–1976). Photo from the State Archive in Warsaw (72/142/0)

Dworakowski studied ethnography and ethnology at the Free Polish University in Warsaw (1930–1934). This university was private and considered as leftist, admitting at the time the highest percentage of women and Jews. His mentor was Professor Stanisław Poniatowski, a critical and creative continuator of the Kulturkreislehre school, a theorist and methodologist of ethnology, and a researcher of Siberia. Immediately after graduating, Dworakowski was employed as an assistant to Poniatowski in the Department of Ethnology of the Institute of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences of the Warsaw Scientific Society (IAES of the WSS) – at the time, Poniatowski was the president of that Institute. At the time, the WSS served as an academy of science, thus, its goal was scientific research – not educating students.Footnote 7 It was funded by state subsidies and thus dependent on shifts of power in the economic, political, and administrative spheres. Like other scientific institutions in the country, which were “high in cultural capital and low in economic capital” (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2016, 104), the IAES struggled with financial difficulties throughout the entire interwar period. The scientific and research activity of the Department of Ethnology was largely focused on the eastern regions of the Republic of Poland, including Polesie. It was a continuation of its employees’ work before 1914 and stemmed from the commonly shared assumption of the exceptional value of archaic peasant culture of Polesie for the study of the ethnogenesis of Slavs, in general, and for ethnology, in particular. The Department members were thus mainly motivated by scientific reasons; only Dworakowski voiced motives of a nationalistic nature. While simultaneously conducting research in his hometown area, he also engaged in fieldwork in Polesie, the region with the biggest percentage of national minorities: East Slavic peasants and Jews.Footnote 8

Dworakowski’s ethnographic activity in this area was varied in nature and conducted in relation to three institutions. Firstly, within the WSS, Dworakowski conducted his own individual fieldwork on the joint family system in Polesie (e.g., premarital habits of the youth, rites of passage, and annual celebrations). Since the field materials and finished monographs (one of them was to become his doctoral dissertation) burnt down in Warsaw in September 1939, little is known about this research. Its only surviving part is an article “Wedding Rites in Niemowicze” (1938) – a meticulous ethnographic description, illustrated with photographs. Secondly, in 1935, Dworakowski took part in an ethno-sociological expedition directed by Józef Obrębski on behalf of the Committee for Scientific Research of Eastern Poland. In this project, Dworakowski researched sources related to the ethnic structure of Polesie. A small part of this documentation (about 80 pages of fieldnotes and 130 photographic negatives) has survived in Obrębski’s legacy.Footnote 9 The meaning of this expedition in relation to the nationalizing policy of the state will be discussed below.

And finally, Dworakowski’s last undertaking in Polesie, one in which we are particularly interested here, seems to be a typical example of aligning the ethnologist’s research activity with the political interests of the state. This undertaking consisted in fieldwork conducted in July 1938, commissioned by the Science Section of the Committee for the Issues of Petty Nobility in Eastern Poland, of which Dworakowski was a member. It was crowned with the publication of a book entitled Petty Nobility in the Eastern Counties of Volhynia and Polesie (1939).Footnote 10 This piece of Dworakowski’s applied anthropology was supposed to, and did, provide arguments for the state action of national revindication to Polishness and of religious conversion to Catholicism of the local petty nobility, who were mostly Orthodox and spoke local Belarusian-Ukrainian dialects.

The Committee for the Issues of Petty Nobility of the Society for the Development of the Eastern Lands (Ciancia Reference Ciancia2021, 217–219, Grott Reference Grott2013, 216–225; Kacprzak Reference Kacprzak2005, 97–114), established on February 25, 1938, was a community organization. However, it was in essence the public emanation of a secret inter-ministerial committee formed by military authorities in the autumn of 1937 in order to coordinate an extensive campaign aimed at “strengthening the Polishness of Eastern Borderlands” (Jarosz Reference Jarosz and Grott2002).Footnote 11 The deputy Minister of Military Affairs, General Janusz Głuchowski, was head of both these committees (one secret, one public), and he was also member of the authorities of the Society for the Development of the Eastern Lands. The Committee for the Issues of Petty Nobility in Eastern Poland openly formulated its goals to be the “national revindication of nobility and mobilization of all measures to strengthen Polish ardour in the eastern lands of the Republic of Poland” (AAN, KdSZ, I, 60–61). The Scientific Section of the Committee was chaired by another military man – Lt Col Alojzy Horak. Obviously, none of these bodies was independent, as the field of think tanks has to be viewed as homologous to the field of politics. The institutions in question were directly dependent on government officials and their decisions.

Dworakowski became a member of the Committee’s Scientific Section in July 1938, right before the beginning of his fieldwork. In response to the invitation to cooperate with the Section, he wrote: “I will gladly cooperate with the Honourable Gentlemen in the Scientific Section of the Committee not only for scientific, but also patriotic, reasons” (a letter dated July 2, 1938, AAN, KdSZ, 17, 33). What exactly did he mean by “patriotic reasons”? According to his book, he fully identified with the ideology of the Committee and shared its political goals. This identification is also confirmed by the inclusion of the name of Dworakowski among “those members of the Scientific Committee who in the first initial period of work contributed the most to the development of the movement” in the “Report of the Scientific Section for the financial year 1938/39” (AAN, KdSZ, 7, 9). Evidently, he was an active member of the Section, helping not just with its achievements but with its public image as well. His social class habitus presumably also played a role in this involvement, although we have only indirect indications of his attachment to the petty-nobility ethos (namely, his activity for this social stratum). It is known, however, that he was socialized in, and attached to, Polish national mythology.

Dworakowski’s book is a testimony to both the author’s ethnographical skills and his political views, which were akin to the ideas and demands of the right-wing, nationalist National Democratic Party (the so-called Endecja). This National Democratic “syndrome of nationalistic thinking” (Kubica Reference Kubica2020, 140) was an ideology Dworakowski shared with several ethnologists working in new institutions created by the state for furthering the nationalizing mission – for example, the Baltic Institute or Institute for the South-Eastern Lands. Bożena Stelmachowska was working for the former (Kubica Reference Kubica2020), and Adam Fischer and Józef Gajek from the Department of Ethnology at Lviv University (Linkiewicz Reference Linkiewicz2016b) were active in both.

Dedicated to General Głuchowski, “a guardian of the Polish petty nobility in the Eastern Borderlands,” and containing “sincere thanks” to Lt Col Horak, Dworakowski’s book unites thorough ethnographic description with nationalist, anti-Ukrainian propaganda, and anti-Semitic statements.

There is indeed something tragic in the fate of this unfortunate Polish population whose homeland, nationality, and language were once taken away by sheer force, and who had been tied, by violence or deceit, to a foreign culture and religion. Today, moreover, there are Ukrainian elements who would like to take advantage of this population in action against Poland […] The vital interests of the Polish nation are threatened […]

wrote Dworakowski in the preface. And he went on,

Let every Pole understand this and let him take even the most modest part in the work on the reconstruction of Polishness in our Eastern Borderlands (Dworakowski Reference Dworakowski1939, 11).

The entire book is written using similar phraseology and a similar emotional tone. The construction of ethnographic facts is immersed in an ethno-religious, nationalist discourse, and scattered throughout are mechanisms of persuasion and axiologically loaded linguistic expressions. More detailed ethnographic, linguistic, and sociological observations made on the basis of fieldwork conducted in 18 noble and noble-peasant villages, which prove Dworakowski’s field experience, or even talent, are reported in a manner devoid of ethnographic objectivity and used to promote a political agenda. The author seems to present himself first and foremost as an actor of the political, not the scientific field, preaching “the supremacy of the Polish culture and Roman-Catholic religion in regard to the primitive culture of Polesie and the eastern rite” (Dworakowski Reference Dworakowski1939, 35). Among the recommendations he formulated, for example, were carrying out propaganda activities for Polish culture and Catholic missions in the Polesie region, constructing Catholic churches, introducing the Gregorian calendar to the Orthodox church, and making the local population aware of their low cultural level. The region in which he was conducting his research was not yet the scene of tearing down Orthodox churches or turning them into Catholic ones, although this was taking place southwest of Polesie, in the Chelm region, simultaneously with his fieldwork. His book, however, laid the discursive foundations for this kind of state violence in Polesie and Volhynia too. Dworakowski declared, in accordance with the political vision of his superiors, that the polonization of Polesie is the expected result of the so-called Polish action – the social effects of which were to serve a strategic goal: the territorial isolation of “two nationalisms” (Dworakowski Reference Dworakowski1939, 33) – a Belarusian one in the north and a Ukrainian one in the south – by dividing them with a “Polish wedge.” In this context, the scientific aspect of Dworakowski’s work on the petty nobility of Volhynia and Polesie – in other words, its association with the field of science – has to be considered doubtful.

In sharp contrast to Dworakowski’s conclusions stands the work of Obrębski, who conducted fieldwork in the same region. In regard to the “Polish action,” he wrote:

The main difficulty of the Polish action lies in [its] lack of appreciation of the real current needs of the countryside and ignoring the inclinations of local inhabitants. The exclusive nature of the Polish centres, carrying out polonization activities in an atmosphere of coercion and conflict, also influences the action’s effectiveness […] Poles are trying to impose their values not through cooperation, but through struggle and conflict. Arrogant Kulturträger […] The idea of the Poleshuk: a primitive being elevated to a certain level of civilisation from the depths of savageness […] There is lack of will to understand and sympathise with a foreign culture. (Obrębski Reference Obrębski and Engelking2007, 501, 535–536)

After 1945, Dworakowski worked for a short time in the Department of Ethnology at the University of Warsaw, participating in the postwar reconstruction of ethnography and ethnology in the academic field. After a year, he left the University and settled in his hometown area where he took up beekeeping. Privately, he was still active as an ethnographer-fieldworker, collaborating at the end of his life with the Białystok Scientific Society, founded in 1962.

The reasons for his leaving the academic field are unknown. Political reasons cannot be excluded. Perhaps the new communist authorities learned about Dworakowski’s prewar connections with the Sanation regime and deemed him a persona non grata at the university, which was under their political control. However, this is only a hypothesis, which requires further study. Whatever the cause of this turn of events, there is no doubt that the postwar transformation of Stanisław Dworakowski, who accumulated considerable academic capital in the prewar stage of his career, into a private person was preceded by the episode of collaboration with the nationalizing state described above.

Case 2. From Academy to Prison. Joachim Chajes (1902–1942?): Scholar in Conflict with a Nationalizing State

The case of Joachim or Chaim Chajes (in English transcription: Khayes)Footnote 12 stands in radical contrast to that of Dworakowski (see figure 2). This ethnologist did not become – nor could he become, for structural reasons – a supporter of the nationalizing policy of the Polish state. On the contrary, he became a victim of this policy; the state’s policy was to polonize Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities – not the Jews, whom the authorities wished to alienate. Chajes’s case demonstrates how risky it was for a Polish Jewish scholar to take on novel ethnological concepts. In contrast to Dworakowski, whose work as an ethnographer focused on traditional, and thus uncontroversial, issues, Chajes was an anthropologic innovator when it comes to research topics.

Figure 2. Joachim Chajes (1902–1942?). Photo from the Lithuanian Central State Archives (F. 175, ap. 5IVB, b. 77, l. 30)

Joachim Chajes was born to a merchant family in Kolomyia, at the foot of the Ukrainian Carpathians. In contrast to Dworakowski, who was brought up in an ethnically exclusive discourse of Polish nationalism, the society Chajes grew up in was multilingual and multicultural: he was a Galician Jew absorbing both German and Polish culture; he used the non-Jewish version of his name and only began using the name Chaim in the Yiddishist milieu in Vilnius. His father was an orthodox Jew; Joachim, however, received a secular education in non-Jewish schools. He attended Polish gymnasiums in Kolomyia and Vienna and a Ukrainian one in Kolomyia. In 1921, he moved to Vilnius, where he began studying at the experimental Jewish Teachers’ Seminary (Golomb Reference Golomb1933; Szyba, Reference Szybaforthcoming). The Seminary, operating according to the rules of modern pedagogy, educated teachers for secular Jewish schools teaching in Yiddish. It remained under the influence of leftists – in particular, activists from Bund and the left wing of the Poale Zion (Workers of Zion) movement. Chajes became a student in the Seminar’s first year of operating, and, although he ended up spending less than two years in the Seminar, he continued to maintain close relationships with its milieu. Conscripted into the army, after a year of service he returned to Vilnius, this time to the Stefan Batory University (SBU) where he studied ethnography and ethnology (1924–1929) under the guidance of Professor Cezaria Baudouin de Courtenay-Ehrenkreutz.

Ethnology at the University of Vilnius, developing under the direction of two remarkable professors (in 1935, the Chair of Ethnology was taken over from Cezaria Baudouin de Courtenay-Ehrenkreutz by Kazimierz Moszyński), stood out among similar academic units in the country mainly due to its focus on fieldwork and the inclusion of museum activities in the course of research and teaching. Cezaria Ehrenkreutz was devoted to the integration of theory and practice. Drawing inspiration from linguistics and philology, on the one hand, and phenomenology, on the other, she developed an individual approach to the subject and demands of ethnology. She engaged in folklore studies in her own scientific research, which resonated with Chajes’s interests.

Simultaneously, Chajes was active in another academic institution – the Yiddish Scientific Institute, YIVO, directed by Max Weinreich. Established in 1925, this “Jewish academy of sciences,” as many called it, was a private institution financed through donations and fees from YIVO’s friends in many countries across the world. It was treated as a hostile political entity by Polish authorities and police, who kept it under surveillance. The Institute struggled with constant financial problems and desperately tried to remain apolitical – which was doomed to fail, since YIVO was being politicized by the anti-Semitic social environment. The Ethnographic Commission of the Institute was headed by the folklorist Yudah Loeb Cahan, founder of the New York branch of YIVO (Gottesman Reference Gottesman2003, 111–170). Cahan, one of the creators of Jewish folklore studies, was Chajes’s mentor in YIVO, along with Weinreich. For a decade of its existence, Chaim Chajes was the Commission’s secretary (for about seven years as YIVO employee and later as a volunteer). His work focused on gathering, archiving, cataloguing, and describing Jewish folklore and ethnographic materials, as well as artefacts for the Institute’s Ethnographic Museum collection. He coordinated the activity of zamlers – volunteer fieldworkers operating in the Jewish diaspora around the world (Kuznitz Reference Kuznitz2014, 72–80). As emphasized by historians, the Ethnographic Commission was very active and the most popular YIVO unit; it was the ultimate embodiment of the zamler phenomenon (Gottesmann Reference Gottesman2003, 124, 129; Kuznitz Reference Kuznitz2014, 76). At the same time, the Commission was an important actor in the emerging field of world folklore, as well as in the Yiddishist movement,Footnote 13 which employed Yiddish folklore in the process of constructing a modern Jewish “nation” (Fishman Reference Fishman2005). Chajes’s scientific and organizational activity thus also served the process of nationalization of the Jewish diaspora in Poland.

Chaim Chajes was the only YIVO worker linked to the Vilnius University’s ethnology. Therefore, he inevitably played the role of a representative of Jewish ethnography in Polish ethnologist circles, and, at the same time, of an intermediary transferring ideas and practices between the two communities. His main scientific interest was folklore comparative studies: migratory themes, mutual borrowings of beliefs, rituals, and oral poetry between the Jewish and Christian rural communities. Chajes’s mediating position therefore had an organizational-institutional as well as an intellectual dimension. Sources give us the following titles of papers he delivered at the seminars of the SBU’s Ethnology Department: “Review of the book ‘From Research on Ten Jewish Songs’ by Prof. Bystroń,” “Transformation of Some Polish Songs Borrowed by Jewish Craftsmen,” “Report on Ethnographic Research on the Jewish Population in the Village of Laybishki,” and “Lenin in Kyrgyz Epic Poetry and Legends” (LCVA, F. 129, Ap. 2). Research related to that last topic had tragic consequences for him, which will be discussed below. He also published four articles in Yiddish.Footnote 14 In later years, he worked on comparative studies of Jewish, Polish, Russian, and Ukrainian folklore.

At the beginning of 1929, YIVO published a booklet by Naftali Weinig and Chaim Chajes entitled Vos iz azoyns yidishe etnografie? (Hantbichl far zamler) (What is Jewish ethnography? [Handbook for fieldworkers]) (Vaynig and Khayes Reference Vaynig, Khayes, Finkin, Kilcher and Safran2016). This guide, the very first of its kind in Jewish anthropology, played a crucial, formative role in amateur ethnographic collecting of field material; it was called the “Zamler Bible” (Gottesman Reference Gottesman2003, 138–144). It was written within the paradigm of “salvage ethnography” – paramount for the nation-building ideology of Yiddishism, as well as other nationalizing movements – a directive to document the entire heritage of a given culture so that it is not forgotten. The booklet is a propaedeutic and didactic study, concise and exhaustive at the same time, rooted in classical ethnological literature but also taking into account new developments in the discipline and open to new fields of research (such as the city or subcultures) and free from anachronisms. It heralds “the new language of ethnography and folklore studies” (Gottesman Reference Gottesman2003, 144).

In November 1931, a pogrom organized by anti-Semitic students associated with the far-right organizations Camp of Great Poland and All-Polish Youth took place at the university and on the streets of Vilnius (the so-called Wacławski’s case [Aleksiun Reference Aleksiun, Kijek, Markowski and Zieliński2019; 2014, 129–132]). Chajes was attacked and received two knife blows, one in the back and one in the hand. The atmosphere was saturated with anti-Semitism and concomitant anti-communism, which together formed the politically instrumentalized stereotype of “Judeo-Communism” (Gerrits Reference Gerrits1995). This stereotype linking, as if intrinsically, Jews with Communism exerted substantial influence on the collective imagination of Poles. Four months later, in March 1932, Chajes was arrested. The police set a trap in a flat suspected of being frequented by communist activists, to which Chajes happened to come.

He was sentenced to five years in prison and eight years of deprivation of public and honorary civil rights “for belonging to a conspiracy under the name of the Communist Party of Western Belarus, aimed at overthrowing the political and social system of the Polish State by violence and at tearing off part of its territory to join it to the USSR” (LCVA, F. 129, Ap. 2). As a result of an appeal, the sentence was changed to two years in prison, suspension for five years, and deprivation of public and honorary civil rights for the same period. He was also deprived of the right to study for five years, i.e., until June 1938. In total, Chajes spent one year in prison; he was released in June 1933.

Chajes was not a communist, nor a member of the illegal Communist Party of Western Belarus. If he were a communist, he would not have worked in YIVO since Yiddishists and communists were ideological opponents, and the latter were strongly against the Institute’s work (Kuznitz Reference Kuznitz2014, 99–111; Zenderland Reference Zenderland2013, 748–749). He was a member of the legal socialist party Bund where he was involved in cultural and educational work. It was his folklore studies that served as the key pretext to convict him for communist activities. During a search of Chajes’s apartment, the police found Russian and German works on Lenin and leaflets of leftist groups. The testimonies of witnessesFootnote 15 and documents presented to the court confirmed the scientific – not political – nature of the accused’s interest in Lenin: he conducted a research project focused on contemporary folklore originating from Soviet Central Asia, inspired by the character of the leader of the revolution (later researchers categorized it as Soviet folklore of pseudo-folk character). The materials were collected legally for the Institute’s archives, and the leftist literature was obtained by YIVO by legal means. Polish judicial authorities, however, did not believe either the documents or the witnesses; the phantasmatic notion of “Judeo-Communism” proved to be more convincing. From their point of view, a scholar from a Jewish institution who had left-wing views, contacts with the USSR, and research interests of the type supervised by secret police seemed to be the living incarnation of the stereotype of a Jewish communist hostile to the Polish state.

During Chajes’s imprisonment, the activity of YIVO’s Ethnographic Commission died out and was not revived even after his release. There were changes in the Institute itself: in 1935, an Aspirantur training program was established, in which ethnology and folklore studies had a marginal position (Gottesman Reference Gottesman2003, 145–161; Kuznitz Reference Kuznitz2014, 153–157).

Chajes tried to continue his work, which at the time focused on creating a professional folklore archive and preparing a volume of Jewish folklore for print.Footnote 16 His plans and ambitions were thwarted, however, and not only due to the lack of funding. In all likelihood, having a secretary of the Ethnographic Commission with the stigma of being a communist became problematic for the Institute. Chajes wrote extensively about the dilemmas related to his work and the growing frustration resulting from the lack of sufficient understanding and support from the Institute in his letters to Cahan (YIVO, RG 202). These letters, particularly from 1933 on, are a dramatic documentation of Chajes carrying out scientific work in a way that exceeded the strength of one person, in oppressive external conditions, until the end of the Commission’s activity. This work was for him a mission, performed to a large extent without pay. One can imagine how difficult it was to get by in such conditions, let alone support a family.

After graduating in 1929, Joachim Chajes was still in touch with the SBU Ethnology Department, where he participated in seminars and prepared his Master’s thesis. In 1934, his most extensive publication appeared in the Polish-language Jewish Monthly, an article in two sections entitled “Christians on Baal-Shem-Tov” (Chajes Reference Chajes1934), in which he analyzes the mutual exchange of folklore motifs between Hasids and peasants. This work demonstrates how competently and creatively Chajes moved within the realities of both cultures: taking into account the religious and cultural differences between the two groups, he nevertheless did not view them through a national lens. On the basis of this text, one could not say his implicit assumption was methodological nationalism, either Jewish or Polish, although Chajes definitely understood the concept of “nation” according to the paradigm of ethnology prevalent in both Vilnius institutions (the SBU and YIVO), that is, in an objectivist way. He views the Carpathian Hasids and peasants, with whom he became well-acquainted during his field research in the Carpathian Mountains in the vicinity of Kolomyia, mainly from the more accurate perspective of class, basing on the assumption of the similar social environments and worldview categories of the two groups.

After leaving YIVO, he was engaged in auxiliary organizational work at the Stefan Batory University’s Ethnology Department and its Ethnographic Museum. (I was not able to determine whether he was earning a living from somewhere else as well at that time.) He worked on an archive of folklore of northeastern Poland. He privately conducted ethnographic projects together with the curator of the museum, Maria Znamierowska-Prüffer, a friend of his. The community of the Vilnius Ethnology Department, however, did not have sufficient power in the administrative the political fields to guarantee Chajes professional stability and, more importantly, genuine civic equality. The community gave him what it could within the scientific field: intellectual partnership and recognition.

Chajes finally gained recognition in the Jewish community as well. When Vilnius came under Soviet rule in June 1940, Chajes returned to YIVO (which after a series of reorganizations, became, as the Institute of Jewish Culture, a part of the Academy of Sciences of the Lithuanian SSR). However, we have no precise knowledge of this period of his life and of his scientific activities during this relatively short time.

The date and circumstances of Joachim/Chaim Chajes’s death are also unknown. In all likelihood, like thousands of prisoners of the Vilnius ghetto, he was shot by the Nazis during the massacre in Paneriai (today a suburb of Vilnius).

His name is not present in the history of anthropology. In a monograph on YIVO’s history, his name appears in a single footnote (Kuznitz Reference Kuznitz2014, 229). He is mentioned slightly more often in a monograph on Jewish folklorists (Gottesman Reference Gottesman2003), but always in the background, as if hidden behind the lively activity of the Ethnographic Commission. It seems that, paradoxically, despite the great success of the activity of Jewish fieldworkers, the director of their work was not “one of the institutional elite” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Collier1988, xxi).

Chajes, as a Jewish folklorist from a Yiddishist institution striving to achieve cultural and political autonomy (Shanes Reference Shanes1998), remained in structural conflict with the nationalizing Polish state. This conflict was embodied by him in a literal sense. Behind the bars of the Vilnius Lukishki prison, he served as the living proof of “Judeo-Communism” after state authorities used him to legitimize their own nationalist, anti-Semitic, and anti-communist violence. Not only in relation to political power, however, was his position a marginalized one. The Polish academic field in the interwar period was gradually excluding Jews, both professors and students, from full participation in university life, culminating in the introduction of ghetto benches at public universities in the fall of 1937 (Aleksiun Reference Aleksiun2014, 132–135). The recognition received by Chajes in this field was personal and private, not an institutional one, which would entail employment or the possibility to publish. In fact, his position in the Jewish scientific field was similar, despite the undisputable value of his work establishing the foundations of Jewish anthropology in Poland. He was one of those who, in Bourdieu’s words, “having nothing to oppose to the forces of the field, are condemned, in order to exist, or subsist, to float with the tides of the external or internal forces which wrack the milieu” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Collier1988, xxii).

Case 3. Doing One’s Own Thing. Józef Obrębski (1905–1967): Scholar Resisting a Nationalizing State

Józef Obrębski was born in the Podolia province in Ukraine to a family of Polish post-noble intelligentsia (see figure 3).Footnote 17 He received secondary education in Warsaw. His mother was a teacher, raising Józef and his two sisters on her own, as their father died when they were young. She belonged to the social circle of the so-called progressive intelligentsia. Its ethos, democratic and liberal, shaped the worldview of the future anthropologist. While he did not speak publicly about his political views, both his scientific work and his life path, as well as the friendships he cultivated, are a testimony to a leftist habitus. Obrębski studied ethnology and ethnography of Slavs and linguistics at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow (1925–1930). His teacher, Professor Kazimierz Moszyński, a fieldworker, ethnogeographer, cultural historian, author of the theory of critical evolutionism, and an expert on Slavs, recommended him to pursue his doctoral studies at the London School of Economics. Obrębski was exceptionally talented and the most educated of the men discussed in this article. He was a close student of Bronisław Malinowski, which brought him fame in the Polish anthropological milieu. By the early 1930s, he was already a doctor of social anthropology (1934) and the author of several publications about Slavic material culture and traditional medicine. He was working on a book about Macedonian witchcraft and other monographs, which were the result of the first functionalist research of European village that he conducted among the Orthodox highlanders of the Macedonian region of Poreche.Footnote 18

Figure 3. Józef Obrębski (1905–1967). Photo from the author’s collection.

However, when Obrębski returned from London to Warsaw in 1934, he occupied a marginal position in the Polish ethnology subfield. Like many contemporary postdocs, he in the precarious situation of “an anthropologist for hire.” Moszyński and Cezaria Ehrenkreutz-Jędrzejewicz supported him in his search for employment. Perhaps it was the support of the latter that contributed to Obrębski’s employment as a contractor in the government’s interdisciplinary research program in eastern Poland.

The research conducted within this program, viewed as “cross-sectional studies of strategic importance for the Polish state” (Grott Reference Grott2013, 92) and stylized as a civilizing missionFootnote 19 in the public propaganda discourse, included a comprehensive study of economic and ethnic issues. It was conducted by economists, geographers, statisticians, demographers, physical anthropologists, specialists in agricultural issues, historians, linguists, and ethnographers. The region of Polesie, seen as the most promising for polonization efforts, was given priority (Cichoracki Reference Cichoracki2013; Reference Cichoracki2014). The Polish Minister of Military Affairs, general Tadeusz Kasprzycki, head of the government’s Commission for Scientific Research into the Eastern Lands, which supervised the implementation of the program, urged: “We need to go east in great numbers […] we need to work there […] to saturate this region fully with Polish culture, and to strengthen our hold over the land by means of spiritual and economic values” (Zjazd Reference Paprocki1938, 99).Footnote 20

Nevertheless, this political program with an eye to “revindicate” Belarusian and Ukrainian language peasant communities, did not translate in a simple and direct way into the scientific activity of individual researchers. Although the goal of the state agenda was political, the lower-level research goals were scientific, as employers wanted to obtain empirical knowledge. Admittedly, many scholars did not escape methodological nationalism; many were also not free from negative stereotypes of East Slavic minorities (Engelking Reference Engelking2017). Nevertheless, the research itself and its results were not, as can be gathered from Obrębski’s case, under direct political or ideological pressures.Footnote 21 The researchers, however, were constrained by administrative and economic fields, in particular through the reduction of the initially allocated funding.Footnote 22

The most important scientific partner of the Commission was the Institute of Ethnic Studies. It was a private association with relative independence and power, as all think tanks are. Among its members were the greatest authorities in the field of ethnic and minority studies as well as political activists (Grott Reference Grott2013; Stach Reference Stach, Kleinmann, Stach and Wilson2016). As an expert institution mediating between national minorities and state authorities, with connections in the governmental and parliamentary spheres, the Institute had influence on the state’s policies regarding ethnic minorities (Stach Reference Stach, Kleinmann, Stach and Wilson2016). Many of the scholars who carried out the Commission’s research program were members or affiliates of the Institute, including Obrębski.Footnote 23 His research is a good illustration of the power dynamics in the fields of social sciences and think tanks, visible on “the axis of autonomy versus heteronomy, which points to the very definition of the field as a semi-autonomous realm of activity” (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2016, 104).Footnote 24

Obrębski’s three-year field expedition encompassed two voivodships, Polesie and Volhynia. He worked alone or with a companion. Stanisław Dworakowski, at that time clearly fascinated by Obrębski’s intellect and personality, was his field assistant for one season. Data on dialects, ethnonyms, distinctive features of costume, and other elements differentiating local peasant groups collected by Dworakowski and other assistants served as the foundation for Obrębski’s innovative, anti-essentialist theory of ethnic groups and boundaries, which he proclaimed in 1936. Thirty years before Barth and Anderson, he conceptualized these phenomena as “imagined formations” and described the configuration of ethnic groups as a system of oppositions between the perceptions of “others” and “us.”Footnote 25

Besides research on the ethnic structure of Polesie, Obrębski’s interests focused on the processes of social and cultural change, including nation-building. He was interested in the dynamics of nationalization. He sought to discover the factors underlying the advancing nationalization of the countryside and drew theoretical conclusions on the questions of nationality and ethnicity. He understood “nation” in terms of consciousness, consistently arguing against limiting the phenomena of the “nation” to an encyclopedic approach and objectivistic theories.Footnote 26 He deconstructed essentialist conceptualizations of “nation” and ethnic groups, but being the only Polish social scientist at the time to do so, he found little understanding among not only ethnologists but also leading Polish sociologists of nationalism (Lubaś Reference Lubaś and Buchowski2019). Simultaneously, he deconstructed the mechanisms used by the nationalizing state in its project of assimilationist nationalization of East-Slavic minorities.

His anthropological approach can be seen in the references to social practice and his awareness of the need for research results to be applicable. Obrębski conceptualized the peasants of Polesie in terms of potential partners for “active and constructive” civil cooperation. While describing and presenting his interpretation of the process of socio-cultural change in the rural societies of Polesie “from the native’s point of view,” he provided arguments which in his eyes were objective. These arguments stood against the nationalizing policy of “expanding Polishness by means of expansion,” to quote one of the government’s decision makers (Grott Reference Grott2013, 95).

Having confidence in science and in the efficiency of procedures based on its laws, Obrębski was decisively critical of the colonizing goals of the Commission, as expressed in ideological formulas. In his writings, one finds comments about the colonial character of the Polish government’ policy toward Ruthenian peasants. He indicated rhetorical strategies dehumanizing the peasants of Polesie in the general discourse on Polesie and “Poleshuks,”Footnote 27 deconstructing at the same time depreciating images of Belarusian-Ukrainian rural communities (see Borkowska Reference Borkowska2014). In the 1930s, he could not have used the category of symbolic violence. Nevertheless, from today’s perspective, it is clear that his work on the nation-building process in Polesie is precisely an analysis of the mechanisms of symbolic violence. The unorthodox and innovative work of Obrębski points to his being situated at the “intellectual pole” (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2016, 100) of the field of social sciences and his gravitation toward its autonomous extreme at the same time.

Obrębski’s works on Polesie clearly show the discrepancy between the conclusions of his research and the political line of his employers. He expressed his views publicly in his paper “Today’s people of Polesie,” presented during the First Scientific Congress on the Eastern Lands in Warsaw in September 1936. There, he described the social and cultural mechanisms of antagonisms and conflicts between Poleshuks and Poles and analyzed, both in terms of class and nationality, the sense of injustice and humiliation felt by the peasants of Polesie and the formation of the stereotype of the enemy that they applied to Poles. It is worth noting that the Regulation of the President of the Republic of Poland introduced in 1932 stated that “insulting or ridiculing the Polish Nation or the Polish State” was punishable by up to three years of imprisonment.Footnote 28 In light of this law, the research conclusions presented by Obrębski could, as “anti-Polish” or “anti-state,” prove perilous for him. However, as a member of the dominant national group, he was in a much more comfortable situation than Chajes.

The impartial and in-depth description of Polesie’s social situation, together with critical diagnoses, presented by Obrębski nevertheless did not inspire the authorities to revise their nationalizing strategies and practices. On the contrary:

It is noteworthy that local administration, despite being familiar with the conclusions of ethnographic research systematically published in the 1930s and especially in the second half of the decade, ignored them in practice. Thus, it can be concluded that the translation of the effort of the specialists studying Polesie to political practice proved to be undetectable in 1939. (Cichoracki Reference Cichoracki2013, 113)

In the late 1930s, the authorities significantly strengthened – politically, organizationally, discursively, and financially, the polonization of the population in eastern voivodships. In this context, Dworakowski, who collaborated in the state’s project of assimilationist nationalization proved to be the “winner.” Not for long, however.

The nationalizing “civilizing mission” conducted by political and military authorities “had just the opposite effect, producing by the end of the period what had not existed at the beginning: a consolidated, strongly anti-Polish Belarusian and […] Ukrainian national consciousness” (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996, 100). Obrębski’s diagnoses were verified by the events that followed. At the beginning of the war, Polesie became the scene of numerous acts of hostility against Poles. The behavior of the inhabitants of the region, which was deemed “the easiest to polonize,” confirmed the ethno-sociological findings that the exclusion of Orthodox and Russian-speaking citizens from the general national society must lead to an open conflict. Although the nationalistic agenda failed, the politically non-neutral state patronage over Obrębski’s research contributed to lasting scientific achievements.

After the war, which Obrębski spent in Warsaw (writing two anthropological monographs on the peasantry of Polesie),Footnote 29 he was professor at the universities in Lodz and Warsaw. However, he left the country soon after. Invited by Edward E. Evans-Pritchard, he gave a series of lectures in OxfordFootnote 30 and was subsequently employed by London School of Economics as a research sociologist to conduct fieldwork in Jamaica, as part of a project of the West Indian Social Survey, financed by a grant from the British Colonial Social Science Research Council. For a year and a half, he studied the dynamics of the economic system and social structure in the context of the formation of modern post-slave society. He observed the process of the forming of the Jamaican “nation” and elaborated his theory, first conceived during his research in Polesie, on the emergence of modern “nations.”Footnote 31 Afterward, Obrębski’s expert competences found application in the United Nations Trusteeship Department, where he worked as a specialist on decolonizing processes (1948–1958), thus working once more in the orbit of both the scientific and the political fields. He lived in New York until the end of his life, teaching sociology and anthropology at the colleges of CUNY and Long Island University for the last ten years of his live. He participated in American academic life, but he never felt at ease in the academic system there. In the American academic field, he remained a “marginal man” (see Lebow Reference Lebow2019).Footnote 32

Conclusions

The three anthropologists discussed in this article lived in the era of expertise, when the symbolic power of science had substantial influence on reality. At the same time, they were citizens of a state whose authoritarian political power controlled the field of science to a greater extent than in democratic systems. In the subfield of ethnology, in which all three of them operated, it was particularly clear that the dynamics of scientific and organizational work is shaped by the autonomy-heteronomy axis, with the tendency to draw nearer to its heteronomous extreme. In this context, Stanisław Dworakowski, Joachim/Chaim Chajes, and Józef Obrębski adopted different strategies toward the nationalizing discourse and practices of the state.

None of the men who were the subject of this article’s analysis was a leading figure in the scientific field of interwar Poland. Up until the outbreak of World War II, they failed to gain academic power. Paradoxically, the one who came the closest to this was the “freelance intellectual” with a British PhD, Obrębski, and not Dworakowski, who enjoyed a stable position at a scientific institution. He profited from upward mobility thanks to his academic studies, but he had, it seems, smaller amount of cultural capital than Obrębski or Chajes; and as an ethnographer, he was further away from the “intellectual pole” of the scientific field. Obrębski and Chajes were scholars who “orientated mostly toward research and scholarly goals and the intellectual field” but who were nevertheless “placed in a relation of wide-ranging and prolonged dependency” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Collier1988, 74, 84); they thus acquired a low amount of academic capital. They both had at their disposal “scientific power or authority displayed through the direction of a research team [and] scientific prestige measured through the recognition accorded by the scientific field” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Collier1988, 79), but, in their case, these attributes were unstable and accidental and not institutionalized enough. The trajectory of Obrębski’s academic career, unlike that of Chajes, was doubtless upward. The position of Chajes, affiliated with a minority institution that lacked legitimacy in the broader academic field of the state, became more and more permanently marginalized (he was hindered even from obtaining a master’s degree) – a testament to the efficiency of the methods used by the Polish state against the assimilation of Jews. The cases of Chajes and Dworakowski show different sides of the dominance of the field of politics and administration over the scientific field. Dworakowski’s activity in the Committee for the Issues of Petty Nobility in Eastern Poland shows a scholar equating the goals and stakes of science and politics. Dworakowski clearly cared about recognition in the political field.

Obrębski, acting outside the structure of public universities and dependent on institutions funding his research, although not approving of the government’s policy toward national minorities, was “motivated by the prospect that expert knowledge could lead to ‘social betterment’” (Linkiewicz, Reference Linkiewicz, Cain and Kleebergforthcoming). Like Chajes, he maintained research autonomy, and, despite criticizing the nationalizing discourse and practices and analyzing its mechanisms, his scientific choices did not come at such a cost as those of Chajes. He was protected by being a member of the dominant group and by belonging to the academia’s intellectual pole. Dworakowski, a member of the same state nation group, did not protect his autonomy; on the contrary, he willingly introduced the external political criteria into his scientific work. Politicians who wanted their policies to be given legitimacy by science found in Dworakowski a typical example of a scholar in the service of this undertaking.

The three case studies presented in this article form a complex, multi-dimensional illustration of a set of factors determining the dynamics of the autonomy-heteronomy axis of the scientific field in a social space in which science is produced. By showing the not merely symbolic violence exerted by a nationalizing state against the field of science, they also contribute to the reflection on the boundaries of the autonomy of science.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my deep gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers for their extremely valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosures

In accordance with Cambridge University Press policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I am reporting that some of the findings related to Joachim Chajes, including especially those based on a query in the YIVO Archives in New York, were made by Karolina Szymaniak. We are the co-authors of a biographical article about Chajes in the dictionary of Polish anthropologists (Engelking, Szymaniak Reference Engelking, Szymaniak, Ceklarz, Spiss and Święch2019), which is in parts translated and repeated in this article as well. I have disclosed those interests fully to Cambridge University Press, and I have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from that involvement.