Introduction

There is substantial evidence about the challenges encountered by people ageing who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and other less-articulated sexual and gender identities (LGBT+). While LGBT+ older individuals may experience the same challenges as their heterosexual and cisgender peers (Gendron et al., Reference Gendron, Maddux, Krinsky, White, Lockeman, Metcalfe and Aggarwal2013), evidence indicates a lack of appropriate and inclusive health and social care and support for those who require it (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Bern-Klug, Krame and Saunders2010; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Beckerman and Sherman2010; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Harold and Boyer2011; Knochel et al., Reference Knochel, Quam and Croghan2011; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Sharek and Glacken2016; Hafford-Letchfield et al., Reference Hafford-Letchfield, Simpson, Willis and Almack2018). This may be compounded by stigma and discrimination continuing into their later life (Sharek et al., Reference Sharek, McCann, Sheerin, Glacken and Higgins2015; Zella and Arms, Reference Zella and Arms2015; Sekoni et al., Reference Sekoni, Gale, Manga-Atangana, Bhadhuri and Jolly2017). Research has revealed gaps in education and training which could equip the care workforce with better knowledge, skills and confidence on LGBT+ issues in ageing and to address heteronormative and cisgendered assumptions in care provision (Gendron et al., Reference Gendron, Maddux, Krinsky, White, Lockeman, Metcalfe and Aggarwal2013; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Rebbe, Gardella, Worlein and Chamberlin2013; Porter and Krinsky, Reference Porter and Krinsky2014; Pack and Brown, Reference Pack and Brown2017). The content of curricula and the learning resources relied upon may not address LGBT+ issues (Gendron et al., Reference Gendron, Maddux, Krinsky, White, Lockeman, Metcalfe and Aggarwal2013; Sirota, Reference Sirota2013) and/or lack diversity when it does (Frederick-Goldsen et al., Reference Fredriksen-Goldsen, Hoy-Ellis, Goldsen, Emlet and Hooyman2014; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Downes, Sheaf, Bus, Connell, Hafford-Letchfield, Jurček, Pezzella, Rabelink, Robotham, Urek, Der Vaart and Keogh2019; Jurček et al., Reference Jurček, Downes, Keogh, Urek, Sheaf, Hafford-Letchfield, Buitenkamp, van der Vaart and Higgins2021).

This paper describes an initiative that sought to address this gap in professional education through a transnational collaboration with key stakeholders across four European countries. The aim was to explore and document best practices for educators and learners in health and social care from those best able to inform them, and to enable better engagement with the delivery of more inclusive LGBT+ aged care.

Background

As the ageing population increases in Europe, the diversity of those requiring support has also increased (United Nations, 2017). Research demonstrates that LGBT+ people in later life report poorer health than the general population and have worse experiences of care (Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Willis, Fish, Hafford-Letchfield, Semlyen, King, Beach, Almack, Kneale, Toze and Becares2020). This is irrespective of whether they are accessing cancer, palliative/end-of-life (Almack et al., Reference Almack, Seymour and Bellamy2010; Higgins and Hynes Reference Higgins and Hynes2019), dementia and/or mental health services (Price, Reference Price2010; McGovern, Reference McGovern2014). LGBT+ older people for a number of reasons may not have the expansive family networks of support as they enter old age when compared to people who do not identify as LGBT+ (Choi and Meyer, Reference Choi and Meyer2016; O'Reilly et al., Reference O'Reilly, Hafford-Letchfield and Lambert2018). This may lead to more loneliness and isolation, which has been associated with poorer mental and physical health and avoidance of accessing timely support (Frederick-Goldsen et al., Reference Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Barkan, Muraco and Hoy-Ellis2013; King et al., Reference King, Santos and Crowhurst2017, Reference King, Almack and Jones2019). Studies also indicate that their life stories and relationships are overlooked and undervalued when they interact with care services (Almack et al., Reference Almack, Seymour and Bellamy2010; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Sharek, McCann, Sheerin, Glacken, Breen and McCarron2012; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, King, Almack, Suen, Bailey, Fish and Karban2015).

These inequalities in outcomes are attributed to a number of issues, including a lifetime of exposure to prejudice and discrimination resulting in ‘minority stress’ (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003) and/or use of adaptive or compensatory behaviours such as problematic substance use (Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Willis, Fish, Hafford-Letchfield, Semlyen, King, Beach, Almack, Kneale, Toze and Becares2020). The anticipation or experience of discriminatory attitudes among care providers in the form of heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia and transphobia also contributes to delay in access and a lower uptake of health services (Hinchliff et al., Reference Hinchcliff, Gott and Galena2005; Irwin, Reference Irwin2007; Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Almack and Walthery2018; Willis et al., Reference Willis, Raithby, Maegusuku-Hewett and Miles2018). Lack of inclusive care has been linked to conflicting religious and cultural beliefs (Brown and Cocker, Reference Brown and Cocker2011; Barnes and Meyer, Reference Barnes and Meyer2012), to ageist attitudes in relation to sexuality and ageing (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Schouten and Henrickson2018; Gewirtz-Meydan et al., Reference Gewirtz-Meydan, Hafford-Letchfield, Ayalon, Benyamini, Biermann, Coffey, Jackson, Phelan, Voß, Geiger and Zeman2018), and a lack of awareness of the need to tailor health and social care, particularly within care homes (Hafford-Letchfield et al., Reference Hafford-Letchfield, Simpson, Willis and Almack2018; Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Almack and Walthery2018; Willis et al., Reference Willis, Raithby, Maegusuku-Hewett and Miles2018). The provision of affirmative care for LGBT+ older people has been firmly linked to the need for awareness and targeted education and training supported by policies and benchmarking standards (Bell et al. Reference Bell, Bern-Klug, Krame and Saunders2010; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Beckerman and Sherman2010; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Harold and Boyer2011; Knochel et al., Reference Knochel, Quam and Croghan2011; Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Sharek and Glacken2016). Two systematic reviews of LGBT+ ageing education (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Downes, Sheaf, Bus, Connell, Hafford-Letchfield, Jurček, Pezzella, Rabelink, Robotham, Urek, Der Vaart and Keogh2019; Jurček et al., Reference Jurček, Downes, Keogh, Urek, Sheaf, Hafford-Letchfield, Buitenkamp, van der Vaart and Higgins2021) focused on pedagogic principles and outcomes from interventions used to educate the health and social care workforce. Recommended areas for improvement included giving attention to curriculum content, teaching and assessment strategies that overcome barriers to their inclusion. These two reviews call for more explicit standards, benchmarks and learning outcomes within professional education on ageing inequalities and broader issues of care that impact on LGBT+ populations (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Downes, Sheaf, Bus, Connell, Hafford-Letchfield, Jurček, Pezzella, Rabelink, Robotham, Urek, Der Vaart and Keogh2019; Jurček et al., Reference Jurček, Downes, Keogh, Urek, Sheaf, Hafford-Letchfield, Buitenkamp, van der Vaart and Higgins2021). Most importantly, diversification of intervention content and patient and public involvement in the design, delivery and evaluation of educational interventions could improve efforts and have a more sustained impact on LGBT+ ageing inequalities (Jurček et al., Reference Jurček, Downes, Keogh, Urek, Sheaf, Hafford-Letchfield, Buitenkamp, van der Vaart and Higgins2021). Further, LGBT+ older people do not form a homogenous group and have multiple and complex identities including, ethnicity, gender, disability, class, geographic location, religion and age (King et al., Reference King, Santos and Crowhurst2017, Reference King, Almack and Jones2019). Intersectional approaches to understand how belonging to a number of different minority populations can lead to increased resilience and unique positive ways of being (Leonard and Mann, Reference Leonard and Mann2018; King et al., Reference King, Almack and Jones2019). All of these factors are important for how health and social care professionals’ work with LGBT+ older people and how they acquire the knowledge and skills to do so.

Background to the BEING ME programme

The BEING ME programme funded by the European Union (EU) ‘Erasmus Plus’ involved collaboration between four EU countries: The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and Slovenia. This project advocated for better inclusion of LGBT+ people in later life as they approach or use care services, by giving attention to the role of education and training of the care workforce. Collaborating on an international level enabled the identification and sharing of multiple methods and good practices in professional and vocational education and capitalised on partners' existing experience and expertise. In recognising different sources of knowledge through wider engagement, such partnerships can offer richer opportunities and processes for intercultural dialogue with mutual benefits (King, Reference King2015; Durose et al., Reference Durose, Beebeejaun, Rees, Richardson and Richardson2016; King et al., Reference King, Almack and Suen2018). The project envisaged bringing these together in the form of a formal resource or toolkit.

Programme aims and objectives

The broader aims of the BEING ME programme were:

(1) To define the field of interest by scoping the range of experience, knowledge and perspectives of different stakeholders on the current challenges for LGBT+ people growing older in relation to their health and social care needs.

(2) To identify the current opportunities, priorities and methods of learning about LGBT+ older people within health and social care curricula and to identify any gaps.

(3) To construct a vision of best practice in relation to curriculum, pedagogy, learning experiences and supporting learners, and to identify any barriers or enablers in meeting the learning needs of those working with LGBT+ older people.

(4) To translate these into recommendations and tangible resources for improving education, training and learning opportunities for those involved with LGBT+ ageing and to consider how they might be implemented and evaluated.

Methodology

The approach used to achieve these wider project aims was the ‘World Café’ method. The World Café model enabled a co-productive approach across both process and outcomes when searching for best practices by bringing people with experience and expertise in LGBT+ ageing and education together. The World Café methodology is based on the principles and format developed by the World Café Community Foundation (2015) which seeks to create a living network of collaborative dialogue around questions that matter in the real world (Brown and Isaacs, Reference Brown and Isaacs2005). This approach builds on the assumption that

people already have within them the wisdom and creativity to confront difficult challenges. It supposes that the answers we need are already available to us, and that working together can provoke us to see new ways to make a difference in our lives and work. (World Café Community Foundation, 2015: 2)

On a practical level, the World Café involves powerful learning exchange in small groups. It delivers creative ways to stimulate activity and promote collective learning (Anderson, Reference Anderson2011) and draws on constructivist knowledge through social interaction in a relaxed friendly environment (Tan and Brown, Reference Tan and Brown2005). Six key principles (Brown, Reference Brown2002) were used to guide Café organisers through the process of hosting a World Café for this project: (a) creating a hospitable space; (b) exploring questions that matter; (c) encouraging everyone's contribution; (d) connecting diverse people and ideas; (e) listening together for insights, patterns and deeper questions; and (f) making collective knowledge visible.

Participant recuitment and sample

Two World Cafés were hosted during a six-month period in early and late 2018 in two of the EU partner localities: The Netherlands (World Café 1 (WC1)) and the Republic of Ireland (World Café 2 (WC2)).

We conducted participant recruitment purposefully and intentionally through each of the four partner country's networks. The target participants included LGBT+ lay older people, educators, and health and social care professionals.

LGBT+ lay participants were recruited from an LGBT+ national community organisation in Ireland and an LGBT+ national network in The Netherlands. The inclusion criteria was that the individual should be aged 60+. The project partners were from educational institutions, which enabled them to recruit educational and health and social care professionals through their own faculty and by reaching out to organisations aligned with their institution. While all participants received funding to enable them to travel and engage with the World Café, recruitment was limited by the funding guidelines and financial allocation. In total, 37 people attended WC1 and 41 people attended WC2 from across the four countries. In addition, 12 of the EU project partnership members provided facilitation for both World Cafés.

Prior to attendance at each Café, participants were sent a participant information sheet and invited to complete a short pre-Café online survey using Qualtrics software (https://www.qualtrics.com/). This enabled the project team to identify the participant's prior knowledge and experience of the topics and to capture some open commentary on their motivation for attending.

In terms of profile,Footnote 1 at WC1 46 per cent of participants were LGBT+ lay community members, 44 per cent were educators/trainers, 8 per cent were care professionals and 2 per cent were policy makers or researchers. Within the LGBT+ lay community members, 25 per cent identified as lesbian and 21 per cent identified as gay. Across participants in the other categories, 18 per cent identified as heterosexual, 9 per cent as bisexual, 12 per cent as gay, 6 per cent as lesbian and the remainder did not respond or ‘preferred not to say’.

At WC2, 52 per cent of participants were LGBT+ lay community members, 32 per cent were educators/trainers and the remainder were care professionals including 1 per cent involved with policy making. The survey criteria was slightly amended for WC2. Across all participants, 32 per cent identified as heterosexual, 16 per cent identified as bisexual, 12 per cent identified as gay, 12 per cent identified as lesbian, 4 per cent stated ‘preferred not to say’ and the remainder gave no response. Across all participants, 40 per cent identified as cisgender, 8 per cent as transgender, 4 per cent as gender non-conforming, 4 per cent as ‘other’ and the remainder selected ‘prefer not to say’ or gave no response. Information on gender identities was collected for WC2 only.Footnote 2

The age range for participants was 26–80 years across both events (WC1 and WC2) and the majority (96%) were White European.

The World Café process and evaluation

The format involved having one big dynamic Café comprising a minimum of six small Café tables, each of which contributed to the larger network of live discussion. This iterative process provided the core mechanism for sharing our collective knowledge and shaping authentic conversations.

The first Café (WC1) was hosted in a private conference facility. It started with a storytelling session through the facilitated media of song, music and theatre, which ‘set the scene’ and provided an icebreaker for participants. The session was improvisatory to facilitate participants’ voices using an arts-based method. Storytelling is cited as one of the most effective ways of transferring social knowledge between generations (International Longevity Centre UK, 2011) and reflects an older tradition in education (Obedin-Maliver et al., Reference Obedin-Maliver, Goldsmith, Stewart, White, Tran, Brenman, Wells, Fetterman, Garcia and Lunn2011). The storytelling session facilitated extensive support from within the listening group and set a positive tone for the remainder of the process. The second Café was hosted in an LGBT+ community space and again some shorter icebreaker activities in the form of short introductory games were used, as most people already knew each other. Both Cafés established ground rules at the beginning, to enable safe and mutually respectful working practices. Café sessions followed structured ‘rounds’ during which each table addressed the same pre-set question/s. Participants were allocated to tables to balance the contribution from each stakeholder group. Two members of the project team facilitated each table and remained as independent as possible except to guide and enable. The Cafés were conducted in English and the facilitators supported communication where there were language differences.

At the end of the round, the facilitators from each Café table gave summative feedback to the World Café and then participants rotated to different tables, so that by the end the day most participants had met each other. The World Café ended with a formal debriefing and participants attended an evening social activity to enable networking and consolidation of relationships developed.

During the four-month period between each Café, the project team endeavoured to maintain continuity in participation. Securing attendance of some of the same people at both Cafés enabled us to enrich the themes developed in the first Café, as well as capitalise on the positive relationships established. However, not all participants attending WC1 could attend WC2 and their was inevitably some dropout due to arising circumstances. In this case, partners for substitution, resulting in some new participants, conducted further outreach. In addition, a ‘newsletter’ summarising the key outcomes of the first Café was sent to participants with the second pre-attendance survey.

Data collection

We evaluated the project by capturing detailed data during the pre-planned structure and process of engagement with the World Cafés. The project team met ahead of both Cafés to rehearse facilitation and data collection. Data were collected to both inform and measure progress against the broader project aims as well evaluating participants’ experiences of the process.

In WC1, data collected during this process consisted of handwritten contemporary notes made by participants and facilitators during Café-themed discussions, collated participant responses to key questions on flip charts and individual Post-it Notes. The focus of WC2 was on the generation and development of co-produced learning resources based on stimulus materials that individual participants were invited to contribute. The definition of a ‘resource’ was very flexible to capitalise on the different experiences and perspectives. For example, a resource could emerge from a reading or an activity that participants had tried, a selected media clip or visual source, or drawn from their own stories and personal experiences. Some brought several resources. The Café sessions were then structured using a step-by-step guide, which developed these ‘resources’ through a group process. Data from these discussions were captured through handwritten notes by the facilitator at each Café table.

A post-Café evaluation of participants’ experience of the Café process was conducted at the end of each Café in English using a paper-based survey questionnaire (WC1: N = 35; WC2: N = 31).

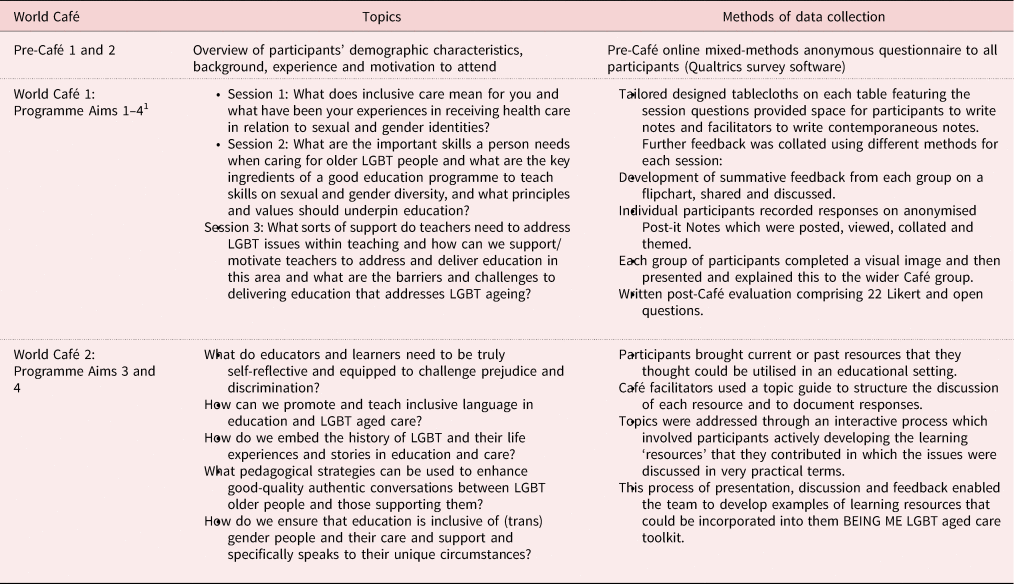

Table 1 provides detail on how the topics discussed were mapped to the four project aims and methods of data collection for both Cafés.

Table 1. Overview of the aims, content, topics and methods of data collection and analyses for both World Cafés

Note: 1. Programme aims: (1) to define and scope the field of interest, experience, knowledge and perspectives of different stakeholders; (2) to identify the current opportunities, priorities and methods of learning about LGBT+ older people; (3) to construct a vision of best practice and its barriers for curriculum, pedagogy, learning experiences and supporting learners; and (4) to translate these into recommendations and tangible resources for improving education, training and learning opportunities.

Ethical statement

The Ethics Committee in the School of Nursing & Midwifery, Trinity College, Dublin granted approval to collect data from Café participants at different points in the programme to enable a full evaluation of how far the programme achieved its aims. Participation was voluntary and not dependent on giving consent to provide data (all participants gave consent however). Project team members obtained informed written consent from the participants in advance. Consent was repeated verbally on the day of the Café. Permission included the taking of pictures and collection of written notes throughout the day.

All text-based sources (i.e. flipcharts, Post-it Notes, facilitator's notes, tablecloth notes) were immediately photographed and scanned at the end of each Café, so they could be stored online. The originals were then destroyed. All data were anonymised at source and any names and identifying features were removed before analysis. All data were stored on a university server with password protection and in accordance with General Data Protection Regulations (Information Commissioners Office, 2018).

Overall data management was co-ordinated by TH-L, AP and SC. The post-Café surveys were co-ordinated by MU and AJ. The online and post-Café paper surveys were anonymised at source.

Data analysis

The pre- and post-Café surveys were analysed by MU, AJ and THL using descriptive statistics together with thematic analysis of any comments made in response to some open questions.

The remaining data sources (as documented in Table 1) were typed into free-hand text by TH-L. This text was then coded deductively as a whole by TH-L and AP and moderated by SC. The guiding framework for qualitative analysis was based on the 8 key topics used to structure Café discussion (see Table 1) mapped to the four programme aims. Further coding of keywords, relevant quotations and examples were then labelled in the text and arranged into inductive themes. These themes were listed and shared with the wider project team for comment and reflection. A virtual team meeting was held to discuss the data analysis and to resolve any differences. TH-L then summarised these into the final agreed themes as outlined below. Three main themes emerged from across the WC1 and WC2 dataset. These concerned inclusive care, education principles, values and environment, and how to address the challenges and support needed by educators to promote LGBT+ in education about ageing care.

Findings

The pre-Café survey asked participants about their motivation for attending the World Café. Responses clustered around the desire to use personal experience to inform education, to embrace one's own curiosity, to do something to allay fears of using services in the future that might not be inclusive, the desire to share and learn from others outside the participant's immediate experience, and to improve and contribute to new developments in learning for self and others. Some people were very specific, e.g. to take up the opportunity to address the lack of education on transgender issues, to learn more about ageing, to feel more confident with terminology and to develop ‘new epistemologies’.

Theme 1: Inclusive care for sexual and gender identities

In WC1, participants identified a range of perspectives and challenges on the notion of ‘inclusive care’. Sub-themes focused on the specific principles and values required to achieve care inclusive for LGBT+ ageing as well as on the environment or culture in which care is accessed and delivered, particularly in relation to ‘coming out’.

Participants described ‘inclusive’ care as a difficult concept to define for LGBT+ populations given its commonalities with what older people expect from their care. They were of the view that the definition needed to be contextualised within current inefficiencies and start with the person, not the service, and encompass all staff coming into contact with LGBT+ older people, e.g. ancillary staff who are essential members of the caring team. Emphasis was placed on providers having an open approach, which incorporated direct consultation with people on how they would like to receive their care. There were also several strands relating to the importance of not stigmatising LGBT+ identities or seeing their needs as problematic.

The participants stated that it was not enough that care staff were able to recognise different identities, but participants stressed the importance of how staff gave these identities ‘real value’. Those with experience felt that it was a few staff that were responsive, but asserted that all staff had responsibility for familiarising themselves with the issues associated with gender and sexual diversity. Familiarisation was about having a genuine interest in the personal stories of those they were supporting, having an appropriate ‘mind-set’ and a good command of inclusive language used in a confident way. Inclusive care was about going beyond glib statements, lip service or ‘ticking boxes’, and being willing to challenge and be challenged in a positive way. Staff were expected to be aware of heteronormativity, presumed cisgenderism and heterosexism by being able to take a purposeful stance and to move away from what is seen as ‘the norm’ as opposed to what is different or not different.

Some participants spoke of being able to ‘feel’ the atmosphere or culture of a service even if the impact of discrimination was not easy to observe or articulate. While they valued some level of curiosity from others, they stressed the importance of respect and not being intrusive. One participant described inclusive care as being able to foster a deeper understanding of individuality; another stated:

Older people often introduce their partners as ‘a friend’ and then workers look for the family members and decisions are made when we should be talking to their friend. (LGBT+ lay community member, WC1)

Participants were of the view for an inclusive culture of care to develop, providers/professional needed to be familiar with people's rights and knowledge of national and international legislation, including acting to promote these rights. In their view, staff should be skilled in articulating and in making an argument as to why LGBT+ needs might merit ‘special treatment’, especially to people with control over resources. This also required an ability to learn from mistakes as well as sharing good experiences within services.

Given these expectations, participants shared mixed experiences of care settings. Examples were given of patients with gender-diverse identities protesting about being placed in a gendered hospital ward without any consultation or choice. They spoke of being deliberately isolated from other patients if they disclosed their gender identity or staff called their gender into question. Others reported ‘people being nasty about homosexuality’, and reiterated feelings of isolation, loneliness, vulnerability and embarrassment, with many reiterating a common experience of ‘going back into the closet’. Another example was the ignorance of care home staff towards sexual or intimate contact between same-sex partners in care homes and in one situation misinterpreting this as putting residents at risk and resulting in raising safeguarding concerns.

While many of the negative experiences were particular to hospital settings, some reported good experiences with family doctors and other health-care staff who provided advocacy in some difficult situations. In relation to coming out, some LGBT+ participants said that they did not always want to come out to everyone, but they did so to ensure that their partner was consulted, involved and that any care home placements accommodated their personal relationships. They spoke of looking for ‘signals’ in care homes of acceptance, as one person put it, ‘having to start again when you go into a care home’. Regarding ‘coming out’, one participant reflected:

People don't have a relaxed look once they realise I am gay, and are wary about what to say. They need to have to think ahead about how they are going to look after me. (LGBT+ lay community member, WC1)

Participants talked about ‘having space to come out’ which was dependent on the skill and demeanour of the staff member. Some staff were described as not being comfortable in acknowledging or discussing everyday issues associated with different sexual and gender identities. This was crucial where participants wanted their partners and people from their personal network more explicitly involved in decision making about their care. Participants suggested training professionals in the use of open questions such as ‘Who is in your network?’ and ‘Who are you closest to?’ Concerning developments in identifying gender identities as part of care, participants felt that this often leads to ticking a box confirming sexual or gender identities. This in turn results in other aspects of their identities being ignored when sexuality or gender is focused on. A debated aspect of this discussion concerned the most appropriate time to ask these questions, for example:

Not everybody wants to be in a box, but we need to be in a box to notice us. (Comment during sharing of group image, WC1)

Participants agreed that their intimate and sexual selves often become more invisible as they age. This was disappointing for those LGBT+ older people who had already fought for their rights during their lifetime, as one older gay man stated:

Some people are growing old with HIV – and so there is a lot of hope – we need to share our history and begin earlier with the young people. (LGBT+ lay community member, WC1)

The context in which care is developed and provided can also make a difference to its inclusiveness. Participants gave many examples of national political situations where the social climate will influence what is actually possible. Examples were given of religious influences specific to Slovenia and Ireland. One example described highly dependent older people being taken to attend religious services without any consultation due to cultural expectations.

It was noted that in care homes, acceptance and general knowledge of gender identity issues are still very limited and bi-sexuality and intersex identities are not discussed.

Theme 2: Education principles, values and environment

Within this theme, participants elaborated on the significance of the educator and the desired attributes of an authentic learning environment. Sub-themes focused on the importance of communication skills using accurate language and terminology, and being able to address intersectionality. This theme also picked up on the values and culture of the learning environment through involvement of the LGBT+ community in education and creating reflective learning practices. These both referred to learners and their educators.

In terms of the principles and values underpinning education on sexual and gender diversity, these were identified as ‘Nothing about us without us’, respect collaboration, advocacy, openness to learn and intention to challenge discrimination. Human rights were asserted as the basis of setting standards and their legislative authority. Notions of freedom, privacy, non-discrimination, equality, equal access, inclusiveness, non-judgemental, dignity, the right to personal development, integrity and diversity were keywords used in the data. Participants also felt that human rights should be embedded within all levels of care from prevention to intervention in ageing education and this would support greater embeddedness of LGBT+ issues in the ageing curriculum.

Participants’ were asked to use Post-it Notes to prioritise skills and attributes seen as important for caring for an older person from the LGBT+ community. Frequency counts highlighted significant words. The top ones were warmth, nurturing, sensitivity, accurate and reflective listening, compassion, patience, curiosity and adaptability. Further discussion on communication skills in the Café table revealed the need for people to ‘learn how to listen’ and ‘pick up on subtle signals’ about the presenting situation and being more aware of one's own assumptions and the ability to disarm another person. One person articulated this as ‘thinking outside the box’ and ‘taking a holistic whole-person approach’ (social work educator, WC1).

The need for these skills and attributes fed into a wider discussion about the key ingredients of an education programme that would support the development of such skills in working with sexual and gender diversity. Critical reflection was cited several times as a key attribute for educators themselves. This referred to educators being comfortable with not knowing everything. They need to offer space for discussion and actively facilitate the transfer of knowledge within the learning environment and its culture. Reflecting some of our own experiences during the World Café overall, participants made many observations about education needing to be fun, and at times light-hearted. These were seen as key to facilitating active engagement in the area of learner-centred approaches combined with teaching methods that avoid ‘preaching’ but which embed LGBT+ ageing topics throughout the curriculum, in both an explicit and implicit manner.

A consistent sub-theme was the importance of exchanging knowledge and skills through collaboration with LGBT+ advocates and allies by involving people from LGBT+ groups in curriculum design, training and evaluation. These reflected much of the data that sought to explore how people learn about LGBT+ lives rather than following guidance and ‘box ticking’. This engagement with process-oriented methods of learning also extended to cross-disciplinary learning in health and social care. In both WC1 and in the exchange of learning materials in WC2, the introduction of life stories and lived experiences were commonly used, often drawing on arts-based pedagogies such as drama, literature, visual art and comedy to increase their accessibility and impact.

Participants described the engagement with critical reflection, on oneself and in the learning context, as key to effective processing of good learning experiences for learners. Some attention was given to learning in the health and social care workplace given that considerable learning in professional education takes place in practice settings. These might be enhanced through student reflective logs, role-play, case studies, podcasts and activities that focus on personal and professional values, perhaps using improvisation. These formed many examples of the practical resources generated and discussed in WC2.

Within this theme, participants talked about the usefulness of blended learning by using online discussions to provide learners with the opportunity to talk about difficult topics where they might be too embarrassed to ask in front of others. This might involve the use of a private ‘space’ for people to post questions that could be then aired through anonymous structured facilitation. Again, this related to people having enough space to feel safe and to challenge homophobia, biphobia and transphobia through educational opportunities. These could be linked to intersectionality of sexuality – race, disability and culture, for example – and placed in a broader context to support awareness of LGBT+ history and political activism. Again, within this theme, participants asserted the need to acknowledge the strengths of the community rather than just the pathologies or disadvantages experienced by older LGBT+ populations.

Specific skills were recommended as vitally important to include in the curriculum and its delivery, such as the use of nurturing skills for LGBT+ people who may have experienced trauma during their personal history, both emotionally and socially; further, the importance of including epistemology and language (older people, gay, lesbian, etc.) to demystify terms using both good examples and bad examples; and having a clear focus on the epistemological basis of language used within education and utilising teaching methods and discussion in a cumulative approach to transfer these. Again, participants raised the importance of engaging with sexuality, intimacy and ageing as a broader topic beyond sexual or gender diversity by integrating LGBT+ rights within sex and relationship education. Some participants stressed the importance of educators familiarising themselves with caring for trans and non-binary older people as a matter of urgency and ensuring explicit inclusion in any curriculum or learning strategies. Queer theory is often ignored or marginalised.

Theme 3: Challenges and support needed for educators to address LGBT+ ageing

Having identified skills and attributes, within this theme, participants addressed what type of support educators themselves need to address LGBT+ issues within teaching on ageing. Sub-themes illustrated challenges at the level for individual educators, the policies of the educational institution and on how far education links with LGBT+ service users and communities.

Some barriers and challenges for including sexual and gender diversity in education of health and social care practitioners were identified. These were noted as fear and bullying, the religion and cultural backgrounds of educators and learners, institutional resistance including lack of management support, student resistance to learning, lack of space in a crowded curriculum and negativity towards the topic. This included sanctions from external stakeholders who may not see LGBT+ education as a priority. One practice educator wrote:

We need a deeper understanding of individuality that goes beyond lip service and ticking boxes. Staff to be passionate and curious, and to avoid a legalistic approach. The patient must be consulted if problems arise as a result of discrimination and how to do this well is part of the problem. (Social care practitioner educator, WC2)

To support and motivate teachers to address and deliver education in this area some of the recommendations included: ‘training the trainers’ programmes, the integration of LGBT+ with anti-bullying programmes, providing relevant educational material, drawing on LGBT+ leaders as role models and embedding the topics into the mainstream curriculum. It was felt important to engage with LGBT+ students to use their experience to review and structure any programmes of learning and to learn from their own stories and experiences. Again, creativity in learning strategies through visual and other creative media was experienced as being effective in facilitating empathy and student engagement.

Participants made the following suggestions for progression and change: greater exposure to LGBT+ service users and communities, cultural change in the form of creating safer environments, adhering to legislation and policy, having champions and role models, and challenging heteronormativity in all teaching practice. The use of narrative approaches came up constantly in the data.

Secondly, in WC2, the data gave a steer and emphasis on supporting educators’ skills. Those involved in learning and teaching will need to develop their own skills in facilitating this area, permission and support to develop these skills, and a guide to their implementation. They suggested the potential for generating short instructive videos on teaching experiences. They cited being able to manage the process of learning, and manage potentially challenging conversations as necessary to develop educators’ confidence and to support successful outcomes.

Finally, the design of assessment strategies should facilitate testing learners’ understanding and learning appropriate to the target learners. Participants articulated the need for a conceptual map of how to include LGBT+ aged care in the design, implementation and assessment of health and social care curriculum would help to embed as both as a specialist topic and mainstream topic. One educator noted:

Why don't professional standards include LGBT+? (Health educator, WC2)

Concerning education policies echoed in Theme 2, some participants highlighted the particular ironies that can occur with teachers with LGBT+ identities, and how safe it was for them to be out in their education environments and the extent to which they contributed their own knowledge as experts by experience. Educators need support when facing prejudice in the classroom as well as to support their own development as educators to help combat these deficit experiences. The environment was described as key to engagement, e.g. the ability to provide resources to promote inclusivity and the availability of discursive space combined with strategic vision, which are owned by the institution and establish a context for change.

Participant evaluation of World Cafés

A mixed-methods post-Café survey was conducted (WC1: N = 35; WC2: N = 31). This enabled the team to reflect and review the participants’ experience of the World Café process.

Descriptive data using Likert scales revealed that the majority of the participants in both events rated the World Café method positively in being able to meet the objectives of the programme. These were ‘highly satisfactory’ (60% in WC1 and 68% in WC2) or ‘mostly satisfactory’ (34% in WC1 and 32% in WC2). Seventy per cent (in WC1) and 77 per cent (in WC2) of participants agreed with the statement ‘the climate within the group was conducive to open discussion’.

In relation to the qualitative data from the survey from the open commentary, participants emphasised two factors. Firstly, equality among the participants, which they illustrated with comments such as ‘nobody's opinion was more important than the one of the others’ and sensibility towards ‘inclusion of non-native English speakers’. Secondly, a safe and open atmosphere, where ‘there was space for everyone to share their point of view’, ‘warm and accepting atmosphere’, ‘nobody judged you’, ‘everyone was really open minded’ and ‘everyone was really into the subject and wanted to contribute’.

In relation to the Café facilitators, participants added comments such as ‘facilitators made sure everyone had their say’, ‘the facilitators invited and encourage those less engaged’ and groups were small enough to enable everyone's viewpoints to be heard.

In relation to the outcomes of the Cafés for individual participants, open comments were themed in three areas:

(1) Best practices: being able to identify experiences and gaps in learning about LGBT+ older people.

(2) Education: education methodologies and curriculum, such as designing curriculum and pedagogies, content, what and how to address LGBT+ in the classroom, and ideas for learning materials.

(3) Strategies: strategies to overcome barriers to inclusion of LGBT+ education, factors that support or hinder the inclusion of LGBT+ education, and educating the educators.

Participants of WC1 specifically appreciated the opening improvisatory activities to promote sharing personal stories, e.g. ‘the emotional involvement resulting from the theatre and group reflections promoted open and frank participation in all discussions’. Participants of both WC1 and WC2 especially pointed out the collaborative nature of the World Café method, its inclusiveness, and being an enjoyable way to share multiple ideas and generate new resources. They used descriptions such as ‘fun’, ‘enjoyable and creative’, ‘stimulated all senses’, ‘provocative’, ‘inclusive’ and ‘great way to gather lots of info and opinions of many people from different backgrounds’.

Some participants expressed reservations about how much influence they had in ensuring that the knowledge gathered would have impact and whether some of the nuances of the contributions had been lost. They also suggested that more attention could have been given to the diverse need of each group (lesbian, gay, transsexual, bisexual and other minority groups within the sexual and gender-diverse population). One participant in WC2 observed that the event was ‘a bit monocultural’ and greater effort to reach out to black and minority ethnic communities remained an ongoing concern.

Discussion

This paper aimed to share the project team's experiences of exploring, developing and capturing best practices in relation to preparing future care professionals to work more effectively with older people from LGBT+ communities. Seventy-eight people across four EU countries came together on two occasions to consult and progress education, learning and teaching on LGBT+ ageing care based on their direct experiences and skills in problem solving. The Café process facilitated a blending of existing information with participants’ own experiences and expertise. Gendron et al. (Reference Gendron, Maddux, Krinsky, White, Lockeman, Metcalfe and Aggarwal2013) recommended that programming developed to educate professionals and providers of services in later life on issues related to ageing as an LGBT+ adult should be evaluated thoughtfully to show both efficacy and impact.

The World Café method enabled a process of structured learning and knowledge exchange between stakeholders. The engagement of older people's voices from the LGBT+ community who asserted their own narrative reinforces the need for critical pedagogies in education (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Downes, Sheaf, Bus, Connell, Hafford-Letchfield, Jurček, Pezzella, Rabelink, Robotham, Urek, Der Vaart and Keogh2019). Translating personal lives and experiences into wider discourses on ageing can be valuable ingredients for learning. For example, educators find it a challenge to listen, analyse and prioritise the experiences of LGBT+ ageing and to prioritise these in the curriculum. However, based on the contributions made, the importance of inclusion of LGBT+ human rights when learning about ageing reflected much of the research already echoed in the literature. There is a strong case for involving LGBT+ older people in the design and discussion of any education based on our World Café experience. When discrimination is common and survival depends on being able to cope with (potential) exclusion every day, it may be psychologically helpful to suppress or deny such daily negative experiences. In developing co-productive and collaborative methods within educational projects such as this one, there is potential to consider the relations between daily experience and social exclusion with the sense of citizenship and human rights. Purposeful engagement with potential or actual service users and patients in education has the potential to become an effective educational and advocacy tool in its own right (Pelts and Galambos, Reference Pelts and Galambos2017). It was empowering to collaborate with those able to influence the design and delivery of educational interventions as we did in the World Cafés.

There were three key outcomes achieved in the project as a whole but which achieved good foundational status through the World Café method. Firstly, the project team were able to identify 15 best practice principles in developing LGBT+ cultural competence in health and social care education (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Downes, Sheaf, Bus, Connell, Hafford-Letchfield, Jurček, Pezzella, Rabelink, Robotham, Urek, Der Vaart and Keogh2019). These principles were based on recommendations made by Café participants to support and empower educators working in health and social care to foster LGBT+ curricula.Footnote 3 The principles provide a focus for educators in setting out a respectful and positive learning environment. This is necessary to support learners to understand the source and impact of their own prejudices and to develop cognitive and emotional competence by using a variety of teaching strategies.

The second outcome included the generation of tailored co-produced educational resources. During WC1 but specifically in WC2, the project team discovered that there was already a wealth of resources that can be embedded into professional and vocational education. However, having the space, time and engagement was extremely valuable to search, capture, audit and annotate these through stakeholder collaboration. In WC2, participants identified and discussed the application of existing Web resources or hubs on LGBT+ ageing. They brought with them relevant content: visual media and materials, readings, quizzes and games. This emphasised the priorities for developing educators’ and learners’ confidence in how to utilise these resources by giving more attention to the process and outcomes of active learning in addition to the information provided.

The findings from this project and its chosen process for evaluation underpin the essential nature of research- or evidence-informed teaching, which can become merely rhetorical within the neoliberal university (Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Crane, Loomis, Jacobsen, Mott, Dubane and Zupan2015). One of the challenges for professional and vocational education has also been to have educators versed in the reality of practice contexts, keeping up to date with service developments and ensuring effective partnerships to achieve these goals. More radically, leadership is required to explore possible strategies to intervene in and disrupt various forms of oppression that play out through the neoliberalisation of education and the consistent exclusion of LGBT+ and intersectionality within care education.

Thirdly, best practices involve improving the knowledge and capabilities of future care professionals in relation to LGBT+ affirmative practice. Through the experiences of the people involved in the BEING ME project, we sought to underpin education with a person-in-environment perspective. This acknowledges the historical context of older LGBT+ people's lives as well as addressing the unique needs of minority groups within these diverse identities. A key practice emphasised throughout the World Cafés was that LGBT+ issues in ageing care need to be set in the context of holistic and person-centred models as well as integrated with a more open discussion about older people's sexuality generally. All older people require their individuality to be recognised and, in doing so, the diversity of individuality and the experiences of all can be respected (Pugh, Reference Pugh2005). There is an urgent need to develop detailed practices on how culture, religion and ethnicity may affect the delivery of education, which has only been touched on within our work so far.

One of the problems for contemporary education is the challenge for educators trying to balance over-invested curricula and the competing demands from professional bodies on what must, or should be, included. Achieving a good balance between the content of curricula with attention to the learning process itself is essential to the skills to apply learning to practice. In best practice terms, we learned that there is a need for balance between didactic teaching methods for imparting factual information with the use of interactive methods that effect attitudinal change and increase participants’ comfort and confidence. Both are needed to ensure that learners and practitioners take responsibility for their own learning needs and are actively involved in identifying, developing and assessing their own learning to improve practice in the area of LGBT+ aged care.

Finally, at a practical level, by working together closely, we were able to generate a diverse range of useful resources that are rooted in participants’ direct experiences, knowledge and skills. These have since formed the basis for developing a best practices educational toolkit which has since been made freely available on the project website based on the best practices identified.Footnote 4

In the closing session of WC2, participants were asked to identify what would be most essential and desirable to include in the development of a best practices toolkit for LGBT+ aged care. Examples included the structured provision of stimulus material with guidance that addressed the suggested target audience, level of education, and linked to desired outcomes such as skills and underpinning knowledge. They also suggested providing a summary of some of the ‘tips and tricks’ discussed in the World Cafés to aid teaching facilitation. Other suggestions were for the provision of additional sources to extend learning and to provide tools for educator and learner evaluation.

Limitations

The methods used for harvesting contributions from the Café were largely successful, albeit these were conducted in English. It was a challenge to keep going at a pace to capture all the contributions but also to make sure everyone was included. The Erasmus leadership team provided interpretation and translation. Secondly, the nature of the data drawn upon in the evaluation inevitably lacked the robust standardised data collection reserved for more formal research projects. We took steps along the way to ensure consistency in our documentation and interpretation to represent both process and outcomes as transparently as possible. Inevitably, limited time in the Café sessions meant that more indepth or focused topics within LGBT+ ageing were not always achieved. Despite our conscious effort to highlight explicitly bisexual and tran's issues, these warranted more specialist consultations.

Conclusion

Through a process of learning and exchange during two World Cafés, best practices in pedagogic approaches (the method and practice of teaching) emerged. The first World Café provided an abundance of information in relation to people's hopes, experiences, expectations and vision for the education and training of care professionals when working with older people from LGBT+ communities. There were consistent themes, which emerged within and across the sessions and data collected, which reiterated the importance of inclusivity in the teaching and learning of professionals, which was all-encompassing across intersectionality. Whilst sexuality, gender and sexual identities were essential to person-centred care, they were also part and parcel of other identities, culture and lifestyles, and also needed to be engaged with in relation to the individual person, their history and current needs. Given the wide-ranging evidence accumulating in this field, many of our findings on what constitutes inclusive care were not new. We were, however, able to focus on how LGBT+ issues need to be assertively and purposefully injected into the health and social care curriculum. Combined with ageism, these are not given important status in relation to other equality actions and diversity issues in care, and warrant positive action.

In going forward, we have noted that there may currently be a dependence on the commitment of individual educators, and overreliance on those who identify as LGBT+ themselves, to lead these much-needed developments. Inclusivity should reflect LGBT+ issues associated with ageing throughout the health and social care curriculum. Moreover, LGBT+ issues are not just LGBT+ people's business, they need to be everyone's business and as such all educators must be trained in teaching LGBT+ issues and its scholarship. More research is needed on the culture and support needed within educational environments to overcome these alongside other barriers in teaching and learning. These may stem from a lack of interest and support from managers or colleagues, religious beliefs and bullying, both overt and including micro-aggressions.

At the same time training, education and awareness of LGBT+ issues are key to challenging negative attitudes, and these associations need to be explicitly recognised and dealt with. The commitment shown to the World Cafés in this project demonstrates the importance of role modelling and LGBT+ education by building alliances, particularly those which share experiences and partnerships, which in turn facilitate engagement with the experiences of LGBT+ service users. These personal experiences, as illustrated in the formal evaluation, were instrumental when challenging personal beliefs and discrimination.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to the people who gave up their time and shared their experiences generously throughout this project.

Author contributions

All of the authors contributed fully to the project work reported here in its conception, design and implementation. TH-L was responsible for drafting the paper and its main content. MU and AJwere responsible for adding the World Café evaluation. AH, BK and MU provided significant support for writing and the remaining team members provided reading, revision, editing and proofing of the paper in all of its aspects.

Financial support

This work was supported by EU Erasmus KA2 /KA202-Cooperation (for Innovation and the Exchange of Good Practices and Strategic Partnerships for vocational education and training).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.