Key concepts in n-of-1 trials

n-of-1 trials are arguably the future of evidence-based care in schizophrenia. An n-of-1 trial is simply a prospective crossover study of a single patient exposed to different treatment conditions. For example, repetitively comparing a treatment (A) against no treatment (B) (AB, BA) or comparing treatment A against no treatment, against a second treatment C (AB, AC). n-of-1 trials are particularly useful for chronic conditions that are relatively stable over time and where substantial clinical uncertainty exists over the best treatment – such as choice of antipsychotic or other treatment selection in schizophrenia.

n-of-1 trials are very similar to normal ‘trial and error’ clinical practice but with additional measures to reduce bias. Key measures include: balanced treatment v. comparison sequence assignment (which may be aided by randomisation if a large number of treatment blocks are used), blinding (to the extent to which this is possible), and systematic outcome measurements.Reference Kravitz and Naihua1 For psychotropic medications where onset and cessation of effect are slow, building in appropriate run-in and wash-out periods to the design is also important.

Relevance to schizophrenia

n-of-1 trials have existed for decades yet are only now becoming increasingly important in psychiatry and other branches of medicine for three main reasons. First, the improved understanding of the genetic determinants of disease means that personalised treatment based on a patient's particular genetic risk factors is now a reality for some (for example in cancerReference Jackson and Chester2 and epilepsyReference Pierson, Yuan, Marsh, Fuentes-Fajardo, Adams and Markello3) and likely to be available to all in years to come.Reference Davies4 Conceivably thousands of individualised treatments may be indicated to treat highly penetrant ultra-rare or de novo genetic variants associated with a large proportion of severe intellectual disability,Reference McRae, Clayton and Fitzgerald5 autismReference Iossifov, Roak and Sanders6 and, to a lesser extent, schizophrenia.Reference Singh, Walters and Johnstone7 The discovery of auto-antibodies against neurotransmitter receptors underlying a subset of psychotic disorders that previously could have been diagnosed as schizophrenia also emphasises that schizophrenia is not a homogeneous entity.Reference Ellul, Groc, Tamouza and Leboyer8 The uncovering of the likely heterogeneity of mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia means a robust method of assessing response to treatment is required at the individual level, in addition to the group.

Second, n-of-1 trials are the epitome of patient-centred care. They can be used to help those patients whom randomised controlled trials fail: those with comorbid physical, mental or substance use problems, those requiring concurrent medication and those at the extremes of age. Many of these limitations of generalisability apply in medication trials in schizophrenia. n-of-1 trials remove the altruistic component of trial participation and give benefit direct to the individual, which is particularly important for vulnerable groups. Further, n-of-1 trials are easily adaptable to patient preference in terms of interventions trialled and outcome measures assessed. This is important because patient engagement improves outcomes in chronic illnessReference Clayman, Bylund, Chewning and Makoul9 and participation in n-of-1 trials for conditions such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder can increase empowerment and feelings of control.Reference Nikles, Clavarino and Del Mar10

Finally, n-of-1 trials are coming of age as technology to facilitate the systematic assessment of health outcomes is increasingly affordable and available. Regular assessment of predefined measures of response and harm is a key component of an n-of-1 trial. Historically, this has been a resource-intensive process requiring frequent clinician–participant interactions, but the availability of smart phones and ancillary devices (able to record measures such as heart rate, vocal stress and electroencephalograms) means that regular assessment of both physiological and subjective parameters is now much more readily available. Such technology has been harnessed by a recent n-of-1 trial series assessing the impact of statins on muscle painReference Shun-shin and Francis11 and self-monitoring mobile phone applications are already showing feasibility and benefit in mental health disorders,Reference Donker, Petrie, Proudfoot, Clarke, Birch and Christensen12 including psychotic conditions.Reference Palmier-Claus, Ainsworth and Machin13

People with schizophrenia are therefore a key group who are likely to benefit from n-of-1 trials. However, the number and value of existing n-of-1 trials in this patient group is currently unknown. We thus systematically reviewed the available literature on n-of-1 trials in patients with schizophrenia to establish how commonly they are used, the approach to their application, the acceptability of the method to the patient group, and the strengths and weaknesses of existing trials. Our findings aim to inform and improve n-of-1 trials in schizophrenia in the future.

Method

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched MEDLINE (Ovid interface, Ovid MEDLINE in-process and other non-indexed citations and Ovid MEDLINE 1946 onwards), Embase (Ovid interface, 1980 onwards), Cochrane Library (Wiley online platform), Web of Science (core collection) and PsycINFO (Ovid interface 1987 to current) for relevant articles indexed as of 2 February 2017. The following search terms were used (“N-of-1” OR “single patient trial” OR (“individual” OR “single” OR “within”) AND (“patient” or “participant” or “subject”)) OR (“case stud*” AND “experiment”)) AND (“schizophrenia” OR “Psychotic” OR “neuroleptic malignant syndrome” OR “dyskinesia”), and their synonyms, as described in Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.70. Papers citing influential early ‘n-of-1’ publicationsReference Guyatt, Sackett and Adachi14–Reference Guyatt, Sackett, Taylor, Chong, Roberts and Pugsley16 were also screened for their own eligibility.

All titles and abstracts yielded by the searches were screened by A.J.S., with a random sample of 10% screened by C.D. and discrepancies resolved by discussion. The full texts were screened by A.J.S. We included any peer-reviewed studies that exploited an n-of-1 study design as a treatment trial for an individual patient with schizophrenia. We defined n-of-1 studies as those that adhered to the definition described in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for reporting N-of-1 Trials (CENT) 2015 – a single participant trial, using a repeated series of treatment challenge and withdrawal, where one cycle (A) is the intervention being investigated and the other (B) is either a comparative treatment, a control or no intervention.Reference Vohra, Shamseer and Sampson17 Studies that provided insufficient trial detail or were not published in English were excluded.

Data were extracted independently by A.J.S. and K.F.M.M. Data extracted from each study were: first author, year of publication, country of study, duration of study, patient characteristics (age, sex and diagnosis), trial design, intervention(s) used, comparator used, blinding measures, primary outcome measures, method of analysis, results and other outcomes. We adapted the CENT 2015 checklistReference Vohra, Shamseer and Sampson17 to assess how well the studies were reported (Supplementary Table 1). We also assessed the quality of studies using the Cochrane risk of bias criteria, commonly used when assessing clinical trials.Reference Higgins, Altman and Sterne18 See Supplementary Table 2 for the PRISMA checklist for this review. We did not register a review protocol. Ethics committee approval was not required.

Results

Study characteristics

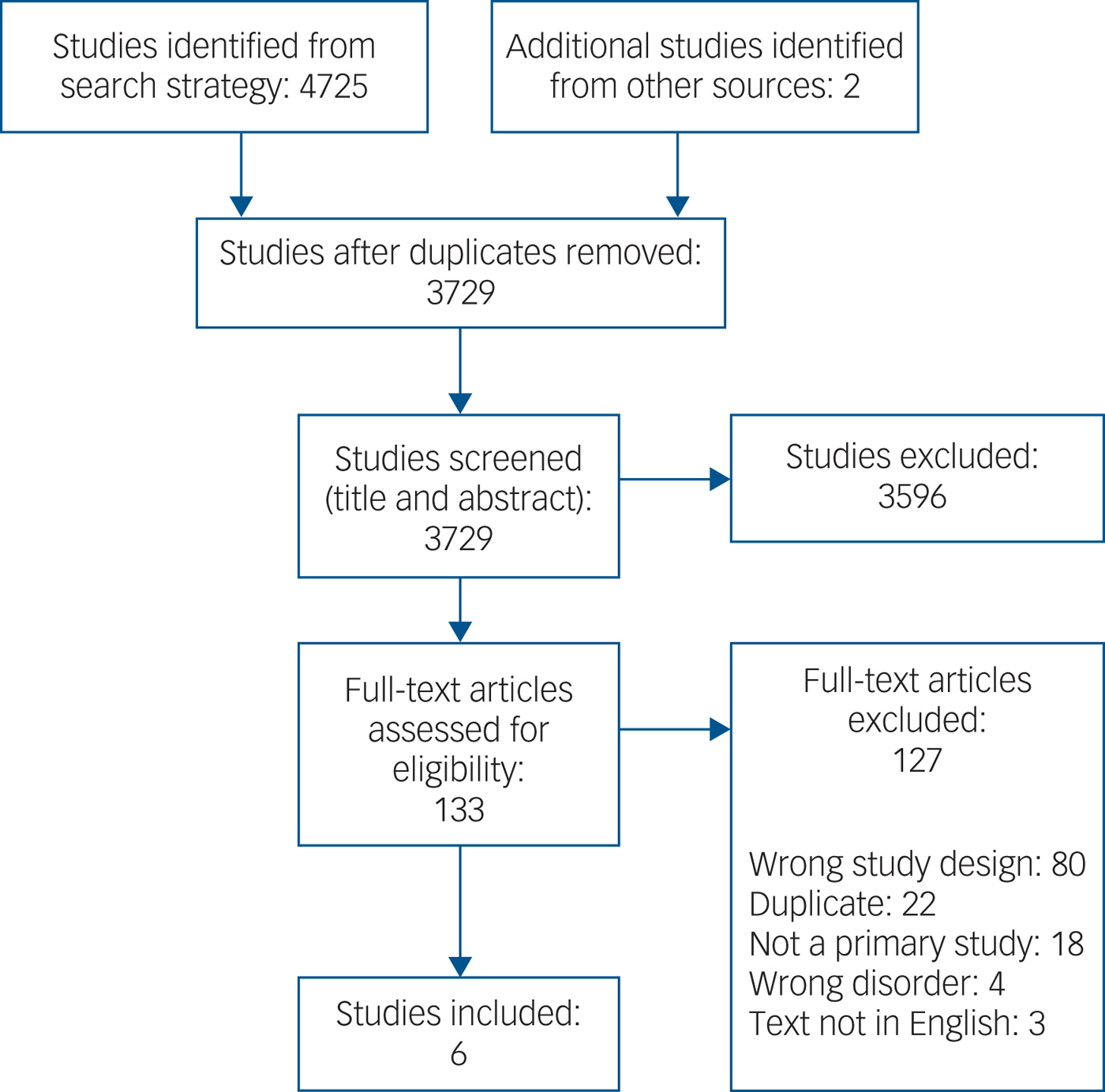

We assessed 4727 citations, of which six studies met inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The included studies are summarised in Table 1.

Fig. 1 Study selection.

Table 1 Study characteristics with key patient data

Five studies reported on a single patient: three men and two women. One study reported an n-of-1 series involving four participants (two men and two women). All participants had received a diagnosis of schizophrenia and were stabilised on antipsychotic medication. Patient ages ranged from 18 to 55 years old, and each had a prolonged history of psychosis and psychiatric intervention, ranging from 2 to 22 years. As expected, each patient's presenting problem, the rationale for employing an n-of-1 approach and the discrete objectives for using each intervention differed greatly between studies.

Study length ranged from 8 to 30 weeks, although one study failed to report duration. Trial designs were diverse with minimal replication: two of the studies adopted an ABAB crossover design,Reference Alford19, Reference MacEwan, Ehmann, Khanbhai and Wrixon20 two an ABA reversal design,Reference Kay and Opler21, Reference Gorczynski, Faulkner, Cohn and Remington22 one an ABAC designReference Done, Frith and Owens23 and one a BAB design.Reference Blanco-Lopez, Cudeiro-Blanco, Iglesias, Gago and Cudeiro24 The nature of interventions trialled was also wide ranging: two studies investigated pharmacological interventions (L-dopaReference Kay and Opler21 and donepezilReference MacEwan, Ehmann, Khanbhai and Wrixon20), two a psychological intervention (‘social reinforcement-assisted cognitive intervention’Reference Alford19 and exercise counsellingReference Gorczynski, Faulkner, Cohn and Remington22), and two a physical intervention (ear plug and transcranial magnetic stimulation). Comparison phases were varied, comprising a mixture of placebos (inactive tablet,Reference Kay and Opler21 ear plug in opposite ear,Reference Done, Frith and Owens23 normal conversationReference Alford19) and treatment as usual.Reference MacEwan, Ehmann, Khanbhai and Wrixon20, Reference Gorczynski, Faulkner, Cohn and Remington22, Reference Blanco-Lopez, Cudeiro-Blanco, Iglesias, Gago and Cudeiro24

Two studies reported blinding measures, with one blinding both the patient and the evaluating physician,Reference Kay and Opler21 and the other only blinding the secondary outcome assessors.Reference Alford19 Of the other four studies, one discloses that no blinding occurredReference MacEwan, Ehmann, Khanbhai and Wrixon20 and the others fail to declare whether or not any measures of blinding were applied.Reference Gorczynski, Faulkner, Cohn and Remington22–Reference Blanco-Lopez, Cudeiro-Blanco, Iglesias, Gago and Cudeiro24

Outcome measures largely comprised assessments of psychological functioning; three papers used standardised assessments and the other three tailored their outcome measures to the individual patient and intervention in question (Table 1). Four of the studies employed both subjective and objective outcome measures.Reference Alford19–Reference Gorczynski, Faulkner, Cohn and Remington22 In one case the objective measure (frequency of exercise via an accelerometer) showed no benefit from the intervention, in contrast to some of the self-report measures.Reference Gorczynski, Faulkner, Cohn and Remington22 Frequency of collection of outcome measures varied considerably. The description of results and analytical measures were largely underreported or underemployed: three papers offered graphical and tabulated data and a qualitative summaryReference Alford19, Reference MacEwan, Ehmann, Khanbhai and Wrixon20, Reference Gorczynski, Faulkner, Cohn and Remington22 but did not report comprehensive raw data scores. Statistical tests were employed by three studies but lacked both full reporting of the tests and the raw data used.Reference Kay and Opler21–Reference Done, Frith and Owens23 One study gave a selective sample of raw data only.Reference Blanco-Lopez, Cudeiro-Blanco, Iglesias, Gago and Cudeiro24

Five of the studies had positive outcomes for the intervention under investigation; two papers that reported statistical analysis showed some statistically significant benefit of the experimental treatment in questionReference Kay and Opler21, Reference Done, Frith and Owens23 whereas the studies which described outcomes qualitatively described a trend of improvement. The study reporting on exercise counselling had mixed findings: it did not find an objective benefit of the intervention but did find some improvement in self-report measures.Reference Gorczynski, Faulkner, Cohn and Remington22 One paper reported that their patient continued on the treatment that was being assessedReference MacEwan, Ehmann, Khanbhai and Wrixon20 and one study found that the outcome remained highly positive several months later without any further intervention required.Reference Blanco-Lopez, Cudeiro-Blanco, Iglesias, Gago and Cudeiro24 Two other studies reported qualified positive outcomes of follow-up assessmentsReference Alford19, Reference Done, Frith and Owens23 but did not indicate if the treatment under investigation was continued.

Quality assessment

Currently, there are no standardised measures for quality assessment in n-of-1 trials so we assessed studies using a standard measure of risk of bias often used in assessments of randomised controlled trialsReference Higgins, Altman and Sterne18, Reference Higgins, Altman and Gøtzsche25 (Table 2). Overall, the trials were assessed as at high risk of bias, with reduced quality because of insufficient reporting of trial detail, insufficient blinding and insufficient numbers of replications of treatment pairs, without opportunity for randomisation or counterbalancing. We also used the CENT 2015 checklist to provide a measure of the completeness and clarity of the reporting of the included studies, which again highlighted gaps in reporting (see Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2 Cochrane risk of bias table, modified for n-of-1 trials

X, high risk; ?, unclear risk; ✓, low risk.

Discussion

Main findings

The most prominent finding of this review is the paucity of n-of-1 trials in the current schizophrenia literature. We found only six studies that corresponded to our inclusion criteria, indicating that the increasing recognition of n-of-1 trials and declarations of interest in personalised psychiatry has not yet translated to research in schizophrenia. Comparison of the key study characteristics reveals the variability in methodological and interventional approaches adopted in such trials: we found one study investigating whether or not an ear plug could reduce auditory hallucinations, one assessing whether transcranial magnetic stimulation could reduce auditory hallucinations, one testing if L-dopa could alleviate negative symptoms, one assessing adjunctive use of donepezil, one using a cognitive intervention to alter delusional beliefs and one assessing the benefits of exercise counselling on activity. The studies encompassed the spectrum of psychiatric treatment modalities, which is promising, indicating this form of trial is viable in the investigation of the range of interventions that are often considered in the complex management of schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders. None of the trials reported any adverse effects, or any issues with patient adherence or acceptability, and they mainly reported positive outcomes, suggesting that such trials are both feasible and potentially valuable in patients with schizophrenia.

Risk of bias

The studies were, however, all considered to be at high risk of bias, largely because of a lack of clarity and depth in their reporting and because they did not include key design features such as blinding and counterbalanced treatment conditions. Our results are similar to comprehensive reviews looking at n-of-1 trials across the medical literature, suggesting these issues need addressing throughout medicine.Reference Punja, Bukutu and Shamseer26, Reference Gabler, Duan, Vohra and Kravitz27 All but one of the studies were published before trial reporting guidelines,Reference Vohra, Shamseer and Sampson17 and the availability of these should improve future n-of-1 trial reporting.

Blinding of the treatment provider and to a lesser extent the patient will always be more difficult in studies providing non-pharmacological interventions, whether the study is a randomised control trialReference Boutron, Tubach, Giraudeau and Ravaud28 or an n-of-1 trial. However, blinding of outcome assessors remains possible, and this also was lacking in the majority of studies.

Additional areas that all of the studies here could have improved on would have been to reduce the risk of bias because of natural variation over time by having more replication cycles (the largest number of cycles was two) and by counterbalancing the treatment and comparison arms (e.g. AB, BA rather than AB, AB). Longer trial durations would also have reduced the risk of measuring placebo and Hawthorne (halo) effects (change in behaviour simply because of the attention received through being a research participant).Reference McCambridge, Witton and Elbourne29 However, one trial found complete resolution of symptoms following the second round of treatment, suggesting that further treatment cycles would be a waste of resource and even potentially harmful. Further, psychological interventions by their nature are designed to have effects with duration beyond the period of treatment, limiting the potential for multiple within-patient replications. The diversity of even the small number of n-of-1 trials considered here highlights the difficulty in dictating quality standards that balance rigour with feasibility.

Use of patient-reported outcomes

Another challenge for future n-of-1 trials is to harness the potential power of patients reporting their own outcomes (e.g. via smart phones) while also ensuring objective assessments. Of the four studies that reported both subjective and objective measures, the findings conflicted in one. Overreliance on subjective assessment can occur in group trials as well as n-of-1 trials, but n-of-1 trials are made particularly vulnerable by their highly patient-centred, sometimes bespoke and often low-resource nature. Patient satisfaction with an intervention is important, but it is not the same as effectiveness.

Limitations

We designed a comprehensive search strategy to ensure we captured all examples of n-of-1 treatment trials in patients with schizophrenia that conformed to our definition; however, it is possible we overlooked some relevant examples. One reason for this, and an area of n-of-1 trials that needs work, is the lack of consensus in the nomenclature; there is no widely accepted, single definition of what constitutes an n-of-1 methodology, with various opinions on a number of fundamental aspects including the necessity for blinding and randomisation and the requisite number of treatment cycles.Reference Kravitz and Naihua1, Reference Shamseer, Sampson and Bukutu30 This variation reflects the adaptability and diversity of n-of-1 methodology, with different approaches and durations required for trials using pharmacological v. psychological interventions, interventions with a substantial v. a subtle impact, conditions with rapid v. slow symptom responses and medications with short v. long speeds of onset and discontinuation.

Furthermore, none of the papers included in this review explicitly identify themselves as an n-of-1 trial; instead they designate themselves as ‘a single-subject experimental study’ (two studies), ‘a single-case experimental analysis’, a ‘single patient study’ and ‘an experimental design case study’, so although they do conform to the CENT 2015 definition of n-of-1 trials this is perhaps more by accident than by design. This means it can be challenging to pick out such studies in the literature. We will also have missed any studies published in a language other than English, and any non-peer-reviewed studies in the ‘grey literature’.

It is also highly probable that not all n-of-1 trials that are executed are published because of a lack of awareness of their potential broader clinical value as, by design, they result in findings that defy simple generalisation, meaning motivation to publish results may not be high. This is particularly likely to be the case with negative findings, potentially placing n-of-1 trials at higher risk of publication bias than trial designs in which pre-registration is the expectation. Although the purpose of n-of-1 trials is to objectively determine the optimal intervention for an individual using data-driven criteria, generalisability and population-level clinical value can be achieved by combining data from series of comparable n-of-1 trials using meta-analytic statistical approaches, predominantly Bayesian.Reference Zucker, Schmid, McIntosh, D'Agostino, Selker and Lau31, Reference Duan, Kravitz and Schmid32 Similar statistical approaches have also been developed to interpret data from related trial methodologies such as sequential multiple assignment randomised trials (SMART)Reference Shortreed, Laber, Stroup, Pineau and Murphy33 (e.g. the CATIE studyReference Stroup, Mcevoy and Swartz34), which could be viewed as n-of-1 trials with a predefined sequence of treatment options and decision points, and individual participant data meta-analysis.Reference Riley, Lambert and Abo-Zaid35 n-of-1 trials therefore represent a method flexible enough for individual treatment optimisation that could also be standardised for wider research into subsets of the population. Awareness of this value should encourage their use, and may reassure pharmaceutical companies and regulatory bodies that n-of-1 trials can provide evidence strong enough to support marketing and licensing decisions for specific groups.

Future directions

Despite the many potential benefits of n-of-1 trials, there has not yet been a rise in such studies in the field of schizophrenia. Our review suggests this is not because of a lack of feasibility or utility but perhaps a lack of awareness of their value and the availability of a formalised approach to their design and conduct. Resources are now available for researchers to effectively plan, execute and analyse such trials, allowing them to attain valuable results for their patients, and potentially the wider population of those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. We hope that the next decade will see a blossoming of high quality n-of-1 trials of various therapeutic strategies in the management of schizophrenia and related conditions.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.71.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the Wellcome Trust 4-year PhD programme in Translational Neuroscience – training the next generation of basic neuroscientists to embrace clinical research (Ref: 108890/Z/15/Z) (A.J.S. and C.D.), and by a postdoctoral clinical lectureship awarded to K.F.M.M. by NHS Education for Scotland and the Chief Scientist Office (Ref: PCL/17/01). No funder had a role in study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, writing of the report or decision to submit for publication.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Steff Lewis for helpful early discussions and Marshall Dozier for advice on search strategy

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.