Many of the world’s women are unable to earn a living and support a family in equal and dignified conditions. Women suffer from segregation in low-paying and low-status jobs, often with long working hours. Women workers are overrepresented in the informal sector and they rarely hold upper management positions, even in sectors where they are numerous (International Labor Organization, 2010). Though most governments of the world have formally committed to advancing women’s economic equality, for example through support for the Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), actual state action to improve women’s economic opportunities remains uneven.

Some governments have reformed overtly discriminatory laws and adopted new provisions seeking to guarantee gender equality in hiring, firing, and other employment-related matters. Others have gone even further by creating mechanisms of enforcement, proactive measures to address inequality and discrimination, and policies that seek to identify and address the unique legal problems women workers confront. On the other hand, some governments do little to combat gender discrimination at work, and keep discriminatory labor laws on the books despite adopting guarantees of formal legal equality that might seem to conflict with those laws (for example, constitutional guarantees of equality).

In this chapter, we identify patterns of cross-national variation in the laws promoting women’s economic equality and analyze the politics behind these policies. We find that women’s organizing and their activism on their own behalf, combined with support from the international activist and international intergovernmental authorities, have advanced women’s legal status and rights in most areas, even more so than we expected when we first began studying these fields.

We define “economic equality” as a situation in which women are not disadvantaged vis–à-vis men in their efforts to gain a living and support a family. This implies that women are not discriminated against on the grounds of gender when it comes to access to work or the circumstances and structure of work (including recruitment, pay, and promotion), and that their gendered social positions – created by pregnancy, childbirth, or parental responsibilities, for example – do not stand in the way of their economic security.

Women’s economic equality is inherently important as a matter of justice. In addition, women’s work promotes the well-being of families and children, even in two-parent households. There is compelling evidence that women’s empowerment, measured by their ability to work outside the home, education, and access to resources, improves child well-being, produces socially desirable outcomes, and is even associated with greater parenting investments by men (Agarwal & Panda, Reference Agarwal and Panda2007; Agarwal, Reference Agarwal1997; Belsky, Bell, Bradley, Stallard, & Stewart-Brown, Reference Belsky, Bell, Bradley, Stallard and Stewart-Brown2006; Bianchi, Cohen, Raley, & Nomaguchi, Reference Bianchi, Cohen, Raley, Nomaguchi and Neckerman2004; Bohn & Campbell, Reference Bohn, Tebben and Campbell2004; Hobcraft, Reference Hobcraft1993; Hook, Reference Hook2006; Iversen & Rosenbluth, Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2010; Schuler, Hashemi, Riley, & Akhter, Reference Schuler, Hashemi, Riley and Akhter1996). Not all women’s work is empowering, however. Women’s work in larger, more formal places of employment produces better effects for families, children, and society as a whole than work in informal, temporary, and marginal positions (Kabeer, Reference Kabeer2012).

Disaggregating Economic Equality

To analyze state action to promote women’s economic equality, this chapter identifies three categories of policies (see Table 3.1) (cf. Mazur, Reference Mazur2002, p. 82). The first category involves the eradication of state-sponsored discrimination. This involves reform of laws and policies that officially discriminate against women by preventing them from working in certain types of jobs (such as those involving heavy machinery, vehicles, alcohol, or other “hazardous” activities) or under certain circumstances (at night or overtime work, and so on). Sometimes these restrictions are justified as being protective, though it is only women who are seen as being in need of protection. At other times they are justified in language that refers to the lack of appropriateness of such work for women. When governments make such distinctions among workers, they reinforce discriminatory social norms that undermine women’s position in the labor market and their access to economic security.

| Type of policy | Indicators |

|---|---|

| State-sponsored discrimination |

|

| Formal equality |

|

| Substantive equality |

|

The second category of policies involves guarantees of formal legal equality in the circumstances of work, including provisions on hiring, promotion, and training. Such policies may take the form of general statements about women’s rights to equal treatment in the workplace, and sometimes these provisions specify particular areas or dimensions to which they apply (hiring, promotion, pay, training, and so forth). Antidiscrimination and equal opportunity laws signify that the state recognizes the problem of gender discrimination and has created a normative framework to combat it. Yet sometimes governments adopt commitments to combat discrimination at work while continuing to uphold laws and tolerate practices that discriminate against women. The coexistence of contradictory bodies of law can persist for years, providing judges and employers different bases on which to make decisions and guide behavior. This phenomenon highlights the importance of considering policy areas as distinct dimensions of the legal regime rather than as developmental stages.

Formal legal equality is not sufficient to advance women’s status and rights. When women’s de facto position in the labor market puts them at a disadvantage, an understanding of equality limited to similar treatment can prolong gender subordination. Social norms, discrimination, and occupational segregation combine to prevent women’s equal access to work and equal working conditions. Many governments have thus adopted measures to promote “substantive equality,” which involves addressing gender-specific problems that constitute barriers to equality at work. Substantive equality policies include the creation of agencies and mechanisms to enforce equal opportunity legislation and of policies to help women in historical and harder-to-reach areas of women’s work (such as the informal sector or domestic work), as well as to increase women’s presence in male-dominated occupations or in managerial ranks.

The case of Japan, where gender discrimination in the workplace has been well documented, helps to illustrate the relationship among the different policy subtypes and the behavior each policy attempts to overcome. Before the time period of our study, Japanese law explicitly endorsed and permitted sex-based differential treatment. The Labor Standards Law of 1947 banned women from certain occupations deemed hazardous, prevented women from working at night, imposed restrictions on women working overtime, and required pre- and postnatal leave as well as nursing and childcare breaks during the workday (Parkinson, Reference Parkinson1989, pp. 608–9, fn. 1–5). Though the law prohibited wage discrimination, it permitted sex-based discrimination in hiring, promotion, training, benefits, recruitment, and job assignments. As a result, across the economy, firms treated men and women workers very differently. Men had higher status and access to superior training, promotion, and pay. It was normal for firms to require women to quit work when they married or had children. Women were rarely promoted to managerial or decision-making positions. Firms forced women to retire earlier than men (often by age thirty!) and tended to fire women workers first when downsizing (Cook & Hayashi, Reference Cook and Hayashi1980; Parkinson, Reference Parkinson1989; Schoppa, Reference Schoppa2008; Weathers, Reference Weathers2005).Footnote 1

It is important to note that these laws all operated in the context of the 1947 Constitution, which banned discrimination by sex. Article 14 stated: “All of the people are equal under the law and there shall be no discrimination in political, economic or social relations because of race, creed, sex, social status or family origin.” However, judges interpreted this provision to allow “reasonable and justifiable discrimination” due to gender role differentiation based on biological differences (Knapp, Reference Knapp1995, p. 97).

Japan’s first attempt to legislate formal sex equality in the workplace was the Equal Employment Opportunity Law (EEOL) of 1985. While feminists advocated the law, both business and unions opposed it. Unions in particular were against the removal of protective legislation (Knapp, Reference Knapp1995). The EEOL relaxed some (but not all) protective labor legislation; prevented firms from discriminating against women in benefits, education and training, retirement policies, and layoffs; and called on firms to endeavor to offer women equal opportunities and treatment in recruitment, hiring, job placement, and promotion. The Ministry of Labor published extremely detailed guidelines instructing firms on how to comply (Parkinson, Reference Parkinson1989).

Notwithstanding the symbolic importance of the 1985 EEOL legislation, it was widely viewed as having failed to curb sexist practices. One problem was that there were no enforcement mechanisms to make sure that firms attempted to recruit men and women into the same jobs. Effectively, nondiscrimination in the crucial areas of hiring and promotion applied only when women were in the same job category as men. Firms took advantage of this loophole by designing separate job categories for men and women. Men’s jobs had better pay, opportunities for promotion, and benefits than women’s jobs (Schoppa, Reference Schoppa2008, p. 59). What is more, gender-based two-track personnel systems were used in more than half of all large firms. In 1993, a group of women workers and lawyers called the “Women’s Circle” submitted a shadow report, entitled A Letter from Japanese Women, to the CEDAW committee of the United Nations, criticizing the EEOL in light of working conditions for women in Japan (Knapp, Reference Knapp1995). A Ministry of Labor study group concluded in 1995 that the law had encouraged gender stratification and called for reform (Weathers, Reference Weathers2005, pp. 74–6).

To correct these problems, the government promulgated a major reform of the EEOL in 1997. This version prohibited sex discrimination in all phases of employment (recruiting, hiring, and job placement), required employers to take measures to prevent sexual harassment, and advocated the use of positive action to promote women. The law also attempted to strengthen enforcement mechanisms by making it easier to use mediation and allowing the government to publicize names of offenders (Weathers Reference Weathers2005, pp. 77–8). The reform amended the Labor Standards Law to relax or abolish protective provisions for women except for those concerning maternity and menstrual leave. As a result, Japanese women over eighteen could work overtime and on night shifts (Hayashi, Reference Hayashi2005).

At the same time, government officials took some action to promote substantive equality. To raise awareness about the objectives of the law, they organized meetings between managers and union officials, shared information on the lack of women managers and gender wage gaps, granted awards to progressive firms, and encouraged sharing of best practices on family-friendly policies (Weathers, Reference Weathers2005, p. 78). But enforcement mechanisms remained weak and most cases were resolved through mediation. Still, a few significant cases in the early 2000s made news headlines, such as when courts ruled illegal the two-track personnel system at Nomura Securities.

By the middle of the decade, the use of gender-based two-track programs had begun to decline. However, women’s work remained precarious, as they constituted a disproportionate share of nonregular workers, including those working part time, on contract, and through a temporary agency. According to a government survey, women made up 64 percent of nonregular workers in 2014, who in turn made up 40 percent of the country’s workforce.Footnote 2

Japan’s experience suggests that policy actions to eradicate state-sponsored discrimination, endorse formal equality, and promote substantive equality constitute necessary conditions to establish the legal basis affirming women’s economic equality. Legal change in only one area is inadequate to promote equality. In fact, adoption of measures in all three areas will not lead to equality overnight. There must be mechanisms to insure compliance with equal opportunities legislation at all levels of society. In the United States, personnel managers at private companies were largely responsible for developing compliance mechanisms, and the best practices they developed for equal opportunity and diversity management diffused nationwide (Dobbin, Reference Dobbin2009). Yet decades later, women (and minorities) still hold only a small fraction of powerful positions in major firms. The struggle for equality in the workplace and other spheres is long and arduous.

Measuring Equal Opportunity Laws

To assess the degree of state-sponsored discrimination for each country, we asked:

(1) Are women prohibited from night work?

(2) Are women prohibited from overtime work?

(3) Are women prohibited from specific occupations by virtue of being women?

(4) Are there religious restrictions on women’s work?

(5) Are there prohibitions against employment (as opposed to special rights offered) that apply to those who are pregnant or were recently pregnant, breastfeeding mothers, or mothers of young children?

(6) Are there laws segregating workers by sex?

Legal regimes are awarded one point for each measure adopted, so that the highest possible score (a “6”) would reflect a regime characterized by all six prohibitions on women’s work while a regime that does none of these things is coded “0.” (No country discriminates on all six grounds, so the most discriminatory country scores a “4.”) We do not count provisions that provide special rights or opportunities to women, such as those that enable women to combine breastfeeding with work, as state-sponsored discrimination. These provisions offer women protections that open more doors for them. This is different from denying women opportunities because they are pregnant or because they are parents of young children, especially when this does not apply to similarly situated male parents.

In order to examine the degree of formal equality, we examined whether the legal regime guarantees equality and prohibits discrimination in all aspects of workplace operation. These must not be general guarantees but guarantees that apply specifically to women and men. We ask:

Are there laws against discrimination against women at work? Are these laws specifically about sex discrimination? Do they (and other measures guaranteeing equality) apply to:

(1) Wages and pay?

(2) Hiring?

(3) Termination of employment?

(4) Access to training?

(5) Equal rights to participate in workplace governance? Unions?

Legal regimes that have general antidiscrimination measures that do not specifically apply to any of these areas receive a “1.” Those that apply to all 5 areas, in addition to prohibiting discrimination in general, are coded “6.”

In addition to these measures of formal equality, we assessed the degree of state attention to substantive equality. Many legal scholars and political theorists have identified limitations to the notion of equality as formally similar or equivalent treatment. Sometimes “formal” equality takes a male norm as its reference point, which implies that women must behave exactly the same as men in order to obtain equal treatment (Boling, Reference Boling2015; Rhode, Reference Rhode1989; Young, Reference Young1990). By contrast, it may be necessary to deal with the distinctive particularities of women’s and men’s work and forms of life to advance equality. What is more, as noted in the discussion of Japan, equality can be understood to apply within occupational or status categories but not across them (with the consequence that equality is consistent with gender disparities). A broader, more robust perspective is necessary to expose gender inequality (Sheppard, Reference Sheppard2010).

Finally, formal guarantees often depend on complaint-based mechanisms of enforcement, which assume that legal guarantees will mostly work and that people will identify them and bring them to the attention of state agencies or the courts. An alternative approach is for the state to assume responsibility actively to monitor compliance with equality guarantees. The burden of identifying and rectifying problems lies with the state and not the victims of discrimination. Policies that go beyond formal guarantees to address the particular character of women’s work (for example, its informality or segregated character), or that seek to take an active rather than passive approach to equality guarantees, are examples of what we are looking for when we assess whether states aim to further substantive, or merely formal, inequality.

Not all governments that embrace laws on formal equality are as quick to adopt measures to promote substantive equality, such as protection for informal sector workers or enforcement mechanisms. Often, labor laws are not seen as applicable to categories of workers where large numbers of women are employed. In Nigeria, minimum wage requirements “do not apply to establishments where there are less than 50 workers or they are employed on a part-time basis or in seasonal employment” (Williams, Reference Williams2004, p. 250), which means they do not apply to the agricultural, seasonal and informal sectors where most women work. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the informal sector makes up more than half of nonagricultural employment, and women constitute more than half of informal sector workers in many economies (Chen, Reference Chen2001, Reference Chen2005). Yet informal sector and rural workers are usually excluded from the rights and protections of national labor laws, including minimum wages, maximum working hours, social security, disability, and so forth. In Egypt, the more than three million women working in farming are excluded from the protections of the New Unified Labor Law of 2003, a fact that has been noted by the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information. Ironically, this means that the most disadvantaged women workers in both developed and developing economies (such as women working in the informal sector as domestic workers, home workers, agricultural workers, and the like) are the people most difficult to reach with regulation, suggesting that innovative policy approaches may be necessary.

Labor laws, as well as other measures promoting gender equality, tend to suffer from lack of enforcement in general. A World Bank report (2013) noted that an important reason why Turkey has not achieved substantive equality in the workplace is because it lacks enforcement mechanisms for its antidiscrimination laws. As a result, employers have found numerous ways to circumvent these laws. Though our concept of substantive equality does not include enforcement or implementation, as noted, we do study the creation of government entities to monitor enforcement, which indicates that policymakers are cognizant of the limits of formal guarantees. To be sure, whether equality-enforcing bodies devised by the law actually operate as envisaged is a question of implementation, and we do not cover that issue in this book.

Laws and policies that treat men and women differently in order to overcome gender disadvantages do not violate principles of equality. For example, in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms adopted in 1982, section 15(1) is aimed at combatting discrimination. It reads: “Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.” Section 15(2), however, is aimed at ensuring that formal equality does not become an obstacle to the adoption and operation of laws intended to advance equality in practice, such as affirmative action policies. That section, which we might think of as being more oriented toward substantive equality, reads: “(2) Subsection (1) does not preclude any law, program or activity that has as its object the amelioration of conditions of disadvantaged individuals or groups including those that are disadvantaged because of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”Footnote 3

This third type of government action, the area of substantive equality,Footnote 4 addresses the specific problems that confront women in the labor market, and seeks to translate formal legal equality into effective legal equality. We measure this third dimension of government action by asking:

(1) Are there any legal or policy mechanisms to enforce guarantees of equality?

(2) Does the government demonstrate, in its policy and rhetoric, an awareness of and attention to the problems of women working in the informal sector? Are there any efforts to address their problems?

(3) Are there any efforts or mechanisms to ensure the applicability of labor laws to the informal sector? Are there provisions for the representation of informal sector workers in formal economic planning or business consultation processes? Are there policies or incentives to facilitate the self-organization of informal sector workers?

(4) Are there provisions for positive action to promote women’s work in nontraditional occupations? Job training?

(5) Does the government offer financial benefits or privileges to companies that promote women workers or to companies owned by women (such as provisions with respect to government contracting for women-owned businesses in the United States)?

Legal regimes characterized by more of these initiatives score higher; those with all five of these types of measures score a “5” while those with none score a “0.”

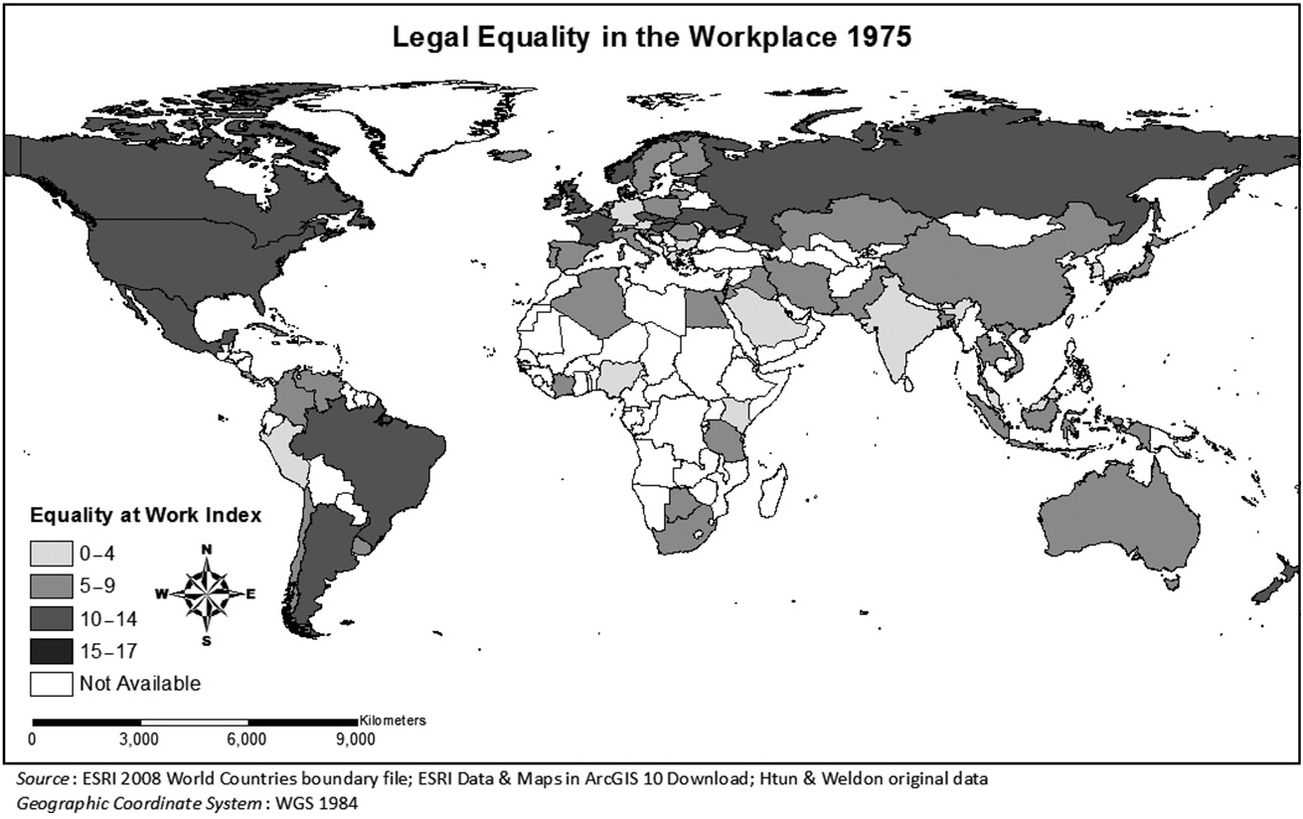

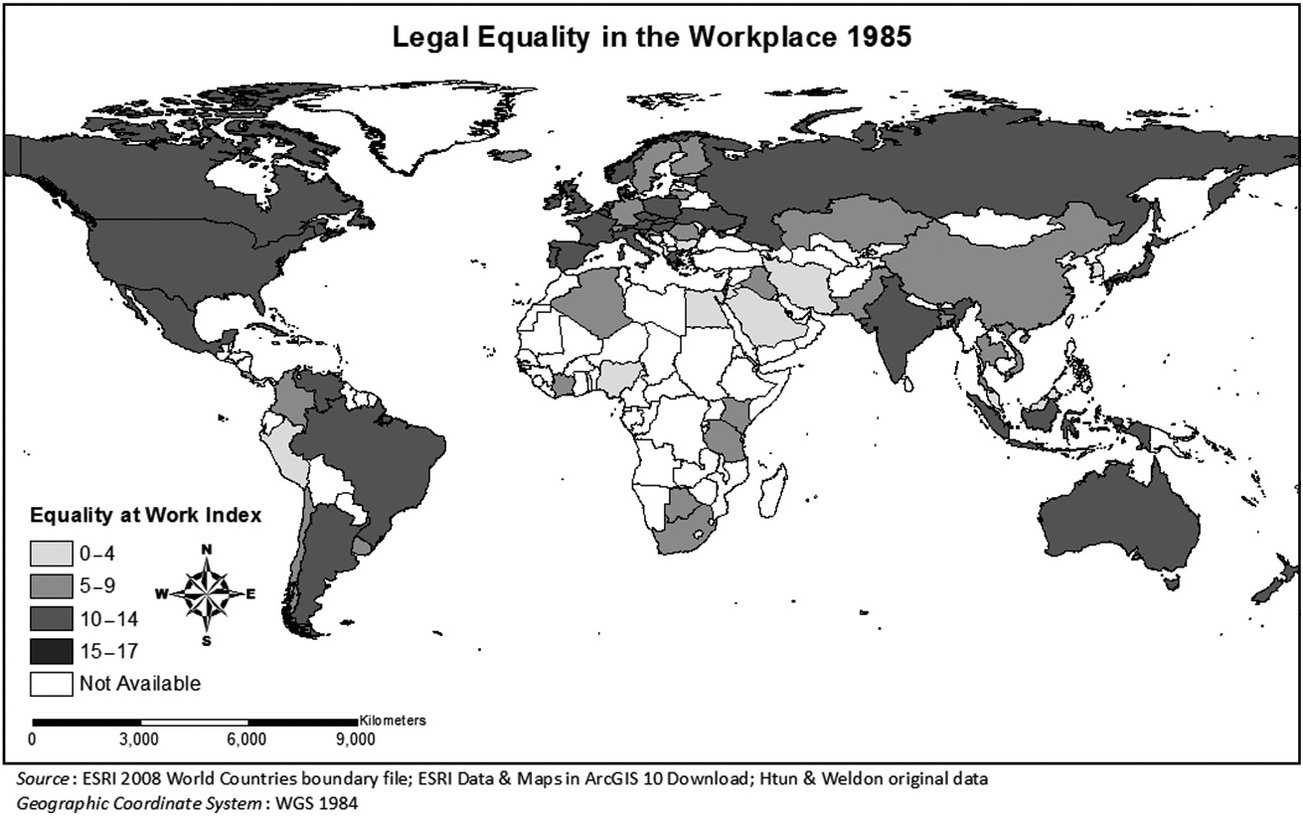

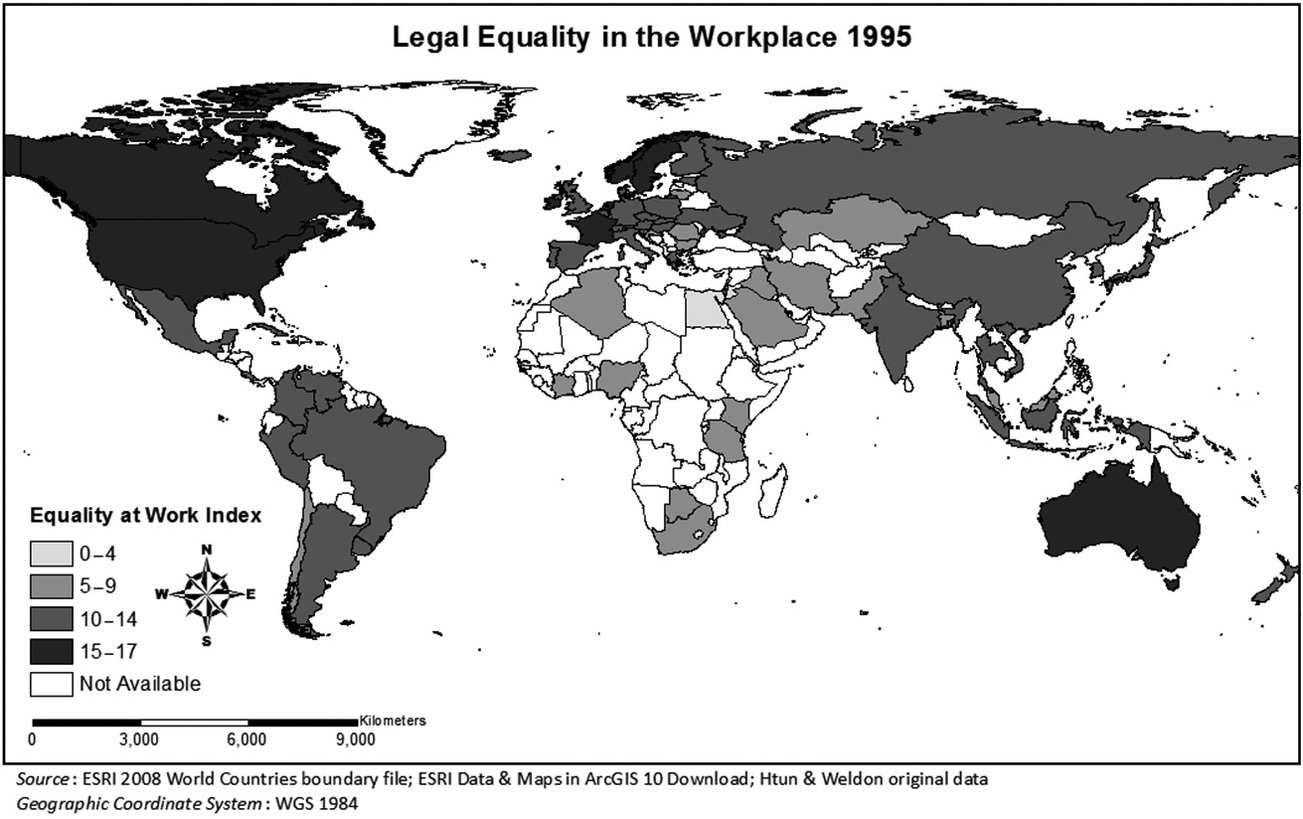

The Indices

We created a series of indices to measure and compare government action on equality at work. One measures state-sponsored discrimination. It ranges from 0 to 6, but relatively few countries adopt more than a few of these measures. We reverse the score here, so that states get points (maximum 6 points) when they do NOT discriminate in each of six possible areas. We call this index the Eradication of State Discrimination Index. We also created measures for formal and substantive equality. We assess formal equality by assigning one point for each aspect outlined (maximum of 6 points), and we assess substantive equality by summing the scores of dummy variables for the five items identified above (so, a maximum of 5 points for substantive equality). Our overall index of legal equality at work sums a country’s score in each of these areas, producing an index of equality that can range from 0 to 17 (though no country has a score lower than 2).

Table 3.2 summarizes some descriptive statistics and shows the mean values and standard deviation for each of the three subindices (top three rows) and the overall equality index (final row). It shows that the value of all indices has grown over time, especially with regard to formal equality. Table 3.3 examines these patterns more closely, by presenting the overall numbers of countries, per year, with each type of legal provision.

| 1975 | 1985 | 1995 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eradication of state-sponsored discrimination | ||||

| 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.7 | .9 | |

| (.98) | (.96) | (1.3) | (1.0) | |

| Formal equality | ||||

| 1.8 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 4.7 | |

| (2.2) | (2.4) | (2.2) | (1.0) | |

| Substantive equality | ||||

| .6 | .9 | 1.7 | 3.1 | |

| (.8) | (1.0) | (1.3) | (1.4) | |

| Overall equality index | ||||

| 7.3 | 8.5 | 10.5 | 12.9 | |

| (2.9) | (3.3) | (3.4) | (2.8) | |

Note: Higher values denote less discrimination. Standard deviations are in parentheses. Eradication of State-sponsored discrimination can hold values from 0 to 6. Legal equality index can hold values from 0 to 6. Substantive equality can hold values from 0 to 5. The Overall equality index is the sum of the Eradication of state-sponsored discrimination, Formal equality, and Substantive equality indices.

Table 3.3 National laws relating to women’s legal status at work. Number of countries with the legal provision in question, of a total of seventy

| Type of law | 1975 | 1985 | 1995 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Law against night work by women | 32 | 32 | 26 | 21 |

| Law against overtime work by women | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Law against women working in specific occupations | 28 | 28 | 29 | 23 |

| Religious restrictions on women’s work | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Ban on work for pregnant women | 10 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Law segregating workers by sex and occupation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Antidiscrimination provisions | 30 | 44 | 58 | 68 |

| General antidiscrimination on basis of sex | 29 | 44 | 57 | 68 |

| Laws requiring equal pay | 24 | 35 | 50 | 60 |

| Laws against sex discrimination in hiring | 15 | 27 | 40 | 48 |

| Laws against sex discrimination in firing | 14 | 22 | 35 | 45 |

| Laws against sex discrimination in training | 11 | 20 | 33 | 42 |

| Laws against sex discrimination in government workplace | 9 | 11 | 17 | 25 |

| Other laws against sex discrimination | 2 | 4 | 7 | 13 |

| Enforcement mechanism for equal work provisions | 20 | 28 | 41 | 59 |

| Policies promoting women’s status at work | 20 | 25 | 36 | 58 |

| Policies promoting women in nontraditional occupations | 2 | 5 | 22 | 47 |

| Policies addressing work in informal sector | 0 | 2 | 6 | 29 |

| Incentives to hire women or to advance sex equality | 0 | 1 | 11 | 23 |

Table 3.3 shows that, although the number of laws upholding state-sponsored discrimination declined overall, in some areas (such as religious restrictions on women’s work and sex segregation at work) the number of countries with discriminatory laws grew. With regard to formal equality, the pattern is more linear. In 1975, it was most typical not to take action to outlaw discrimination. A few countries had provisions against discrimination, but most had none (the median score for formal equality in 1975 was 0). By 2005, the opposite was true: Most countries had adopted laws to prohibit discrimination in about five of the six areas we examined. A similar story may be told about substantive equality: Most countries did nothing to advance substantive equality in 1975 (the median score is 0). By 2005, most governments had adopted three distinct kinds of measures to advance substantive equality, though there was less progress here than on formal equality.

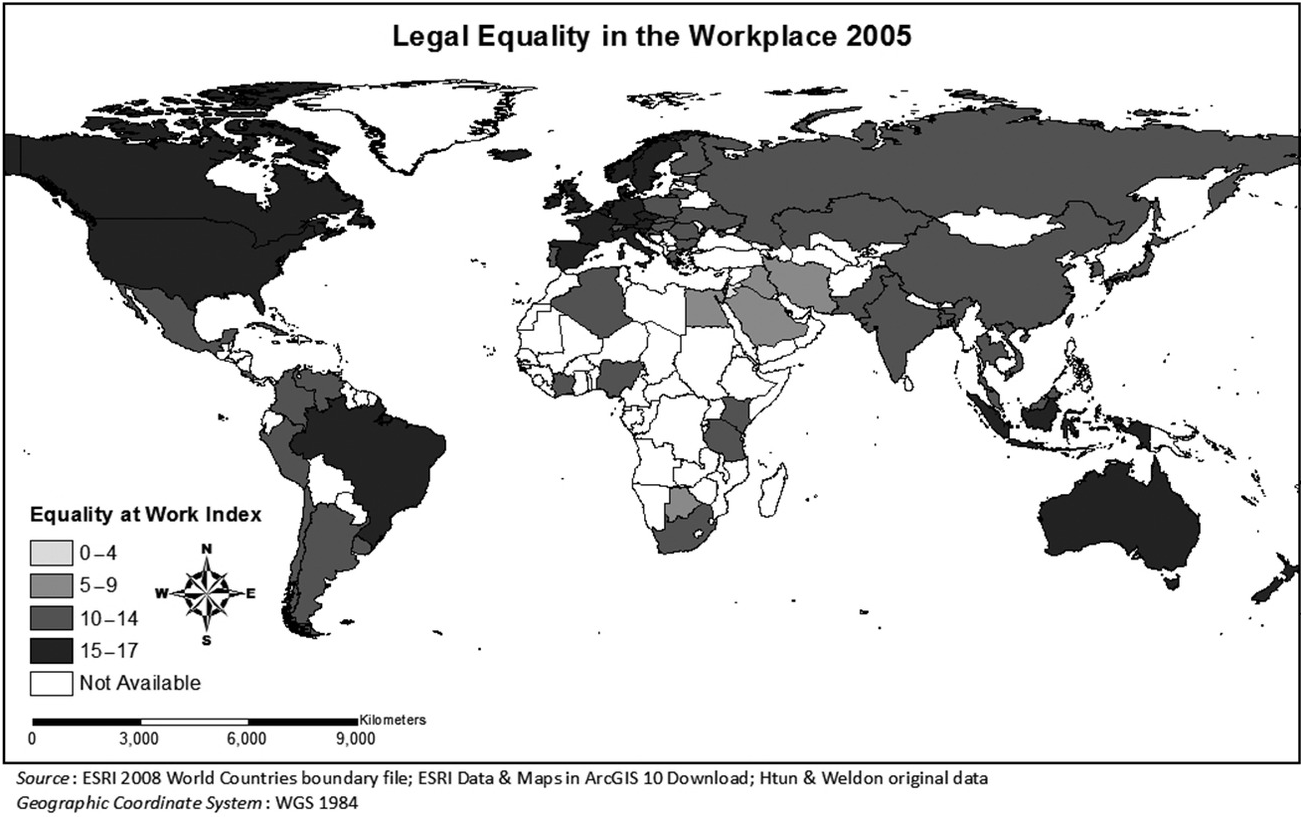

There is considerable regional variation in these trends. For example, in Latin America, state-sponsored discrimination declined, while in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) state-sponsored discrimination increased over the period, more than doubling. Formal and substantive equality also increased more slowly in MENA than in Latin America. Overall, Latin American countries have slightly less legal protection than most countries in our study, but the MENA countries have significantly less legal equality than Latin America and the global average for the countries in our study, as well as more state-sponsored discrimination. Figures 3.1–3.4 show maps displaying the scores on the overall equality index for the seventy countries of our study.

Figure 3.1 Legal equality in the workplace, 1975

Figure 3.2 Legal equality in the workplace, 1985

Figure 3.3 Legal equality in the workplace, 1995

Figure 3.4 Legal equality in the workplace, 2005

Explanation for Historical and Cross-National Variation

What factors help to account for historical changes and cross-national variation in laws shaping women’s status at work? Our typology, described in the first chapter of this book, suggests the ways in which the issue of legal status in employment is distinctive. We characterized women’s economic and workplace equality in our typology as a “nondoctrinal” and “status” issue, like violence against women. Economic equality is nondoctrinal, we reason, for it fails directly to touch upon major issues contemplated in religious scriptures and other texts. Religions have a great deal to say about women’s role in marriage, reproduction, and sexuality, with children, and so forth, but are quieter about women’s role in the public sphere of wage work. To be sure, the fact that many religions exalt women’s role as wife and mother would seem to imply skepticism about their participation in the world of wage work. But in fact, neither the Bible nor the Quran forbids women from working outside of the home. Both texts contain references to women who worked and call for their equal treatment, seemingly recognizing, as do international development agencies in the twenty-first century, that a woman’s ability to fulfill motherly and familial duties often turns on her access to wage work. Our typology thus predicts that, unlike family and abortion law, religious groups will tend not to mobilize to prevent change.

In addition, the typology characterizes laws shaping women’s economic equality as a “status” rather than a “class” issue. Our categorization may seem unusual, since a group’s position in relation to economic resources is precisely what defines a class in the Marxist sense (Wright, Reference Wright1997). The “status” provisions we study pertain to women as a category constructed by institutions of gender. This category cuts across social classes and the lines drawn by professionalization and social capital, which form the basis for modern class structures according to some contemporary, Marxist-influenced scholars such as Perrucci.Footnote 5 Most salient for us is the way that laws on women’s equality at work intervene in the officially defined status of women order to alter social roles and relations, shaping the allocation of rights and responsibilities in the workplace in the way that family law structures the balance of power in the home.

While there are several excellent works outlining differences in women’s employment law around the world (see, e.g., Cotter, Reference Cotter2004), few scholars have undertaken to explain global, or even cross-national, variation. Mazur (Reference Mazur2002), one of the few works to undertake a systematic cross-national study of the political processes driving these laws, provides an overview of the equal employment policies in thirteen advanced industrial states and analyzes the politics behind these policies in four countries: Ireland, Sweden, France, and Great Britain. Mazur finds that the key drivers behind equal employment policies include strategic partnerships between equality agencies, trade unions, and women in public office; authoritative equality agencies; and regional or transnational norms or initiatives (such as the European Union equality policy).

One of the only other comparative studies of policy adoption that examines sex discrimination law is Lindvert’s study of Sweden and Australia (Lindvert, Reference Lindvert2007). In general, Lindvert finds that “gendered policy logics” affect different issues in different ways, but points to specific differences in national policy regimes that shape approaches to sex discrimination. Sex discrimination law in Australia was adopted largely because of a combination of feminist activism, feminist bureaucrats, and international pressure from CEDAW. Feminist organizational skill in navigating the political system was particularly important. In Sweden, sex discrimination was advocated primarily by the Liberal Party, and neglected by Left parties and the unions. Lindvert points out, interestingly, that the gender equality unit in Sweden did not show much interest in promoting legislation on sex discrimination. To expand support for legislation, policy advocates abandoned a liberal, sex discrimination frame and adopted a more redistributive, equality frame, in addition to narrowing the focus of the bill so that it focused primarily on work, in order to secure final adoption (Lindvert, Reference Lindvert2007, p. 250).

These two works by Mazur (Reference Mazur2002) and Lindvert (Reference Lindvert2007) highlight the important role of feminist activists and feminist bureaucrats or agencies, while other studies have emphasized the role of women in other areas of government such as parliament (see Krook & Schwindt-Bayer, Reference Krook, Schwindt-Bayer, Waylen, Celis, Kantola and Weldon2013 for a review). The notion of a “triangle of empowerment” (Vargas & Wieringa, Reference Vargas, Wieringa, Lycklama a Nijeholt, Vargas and Wieringa1998), in which feminist pressure in multiple venues in state and society combines to constitute an avenue for the advancement of women’s rights, builds on these ideas. Feminist transnational activism has produced global treaties and agreements endorsing women’s equal rights at work. Article 11 of CEDAW, for example, calls on states to insure equal rights in all areas of work, including hiring, pay, promotion, training, and benefits. CEDAW also calls for ending pregnancy discrimination, while endorsing some protections for pregnancy, such as maternity leave and work–life balance policies.

The effects of international conventions and domestic activism are intimately entwined, as the discussion of Japan earlier in this chapter suggests, and as the discussion of Canada later in the chapter also illustrates. Mazur and Stetson describe the ways that domestic and international pressures combine and produce a “sandwich effect” (Mazur & McBride, Reference Mazur and McBride2007), in which political pressure exerted by women at the national level interacts with political pressure from the supranational level to stimulate the development of women-friendly policies (Keck & Sikkink, Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998; Van der Vleuten, Reference Van der Vleuten2013). The introduction of European equal pay and equal treatment legislation between 1975 and 1985, combined with national political pressure exerted by women’s movements, is an example of this “sandwich effect,” which has resulted in the modification of social security policies by national governments (Vleuten, 2007, pp. 89–96). This is similar to the boomerang effect documented by Keck and Sikkink (Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998), in which domestic feminist actors appeal to international bodies to pressure recalcitrant domestic governments to respect and promote human rights. Friedman similarly documents a “Pincer effect” in her work on regional advocacy (Reference Friedman2009), while Baldez (Reference Baldez2014) points to the analogy (coined by Javate de Dios) of a circle of empowerment as an alternative way to capture the international–domestic interaction.

The combined effect of international and domestic pressures, or the “sandwich effect,” is similar to the dynamic we found in the earlier analysis of policies on violence against women. Our work in this book explains why this dynamic is particularly powerful for status issues such as violence against women and equality at work, but less crucial for family law, abortion, reproductive rights funding, and social welfare-type policies, where religion and left politics complicate the story. In the rest of this section, we explain the theoretical basis for our explanation for (and model of) cross-national variation in laws shaping equality at work.

Feminist Movements

Promoting equality for women workers involves a fundamental reorientation of women’s social identities as well as normative visions of workers. What is at stake is a vision of women as full human beings and citizens entitled to equal rights in all spheres and endeavors. Put another way, equality at work requires adjusting our assumptions about human beings and workers to include women’s lives and roles. Working for pay is not incompatible with motherhood; rather, working enhances a woman’s ability to fulfill her motherly duties. Nor is working for pay secondary to motherhood and other traditional roles, something that women do merely to supplement family income. (Such a belief often justifies paying women less and passing them over for promotion.) Rather, working is part of being a woman, and being human. Women’s advocacy on their own behalf is crucial to the success of such a revisioning of women’s status (Htun & Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2010, Reference Htun and Weldon2012). Legal and policy changes that induce changes in the cultural and social meanings of women’s roles, as well as shifts in the status ordering of society, tend to involve women’s autonomous mobilization in domestic and global civil societies.

In the North Atlantic and Western European countries that were early to adopt legislation promoting equality at work, women’s movements played prominent roles. The story of equality legislation in Canada illustrates this process. Established feminist groups took up issues of employment in the 1960s against the background of human rights and labor movement activism (Timpson, Reference Timpson2002), and began to urge the government to adopt laws to advance equality. In 1964, Canada ratified the International Labour Organization’s Convention 111 on Discrimination in Employment and Occupation, which officially commits the government to developing a national policy (C111, 11.2). The Royal Commission on Equality in Employment (Abella Commission) was established in 1983; in 1984, it issued a sweeping report recommending major changes to Canadian law and policy and introducing the term “employment equity” (Canada. Royal Commission on Equality in Employment; Abella, Reference Abella1984) The Abella report acknowledged the influence of civil society groups and called for their continued involvement in the policy process. The Federal Employment Equity Act was adopted in 1986 under the conservative government of Brian Mulroney, who had made pay equity part of his electoral campaign (Mentzer, Reference Mentzer2002; Timpson, Reference Timpson2002). In the same year, the Supreme Court supported a case brought by feminist organizations in Quebec (Action Travail des Femmes, or ATF) that required employers to make efforts to promote women’s advancement in nontraditional jobs (C.N. v. Canada). The ATF argued that the Canadian National Railway hiring and promotion policies discriminated on the basis of sex contrary to section 10 of Canada’s Human Rights Act (Jhappan, Reference Jhappan2002).

In 1992, a parliamentary commission headed by a Conservative MP reviewed the Equity Act and made several recommendations for revision (Mentzer, Reference Mentzer2002). Then, in 1995, a revised Employment Equity Act was passed under the liberal government of Jean Chrétien. The new law improved enforcement by requiring that covered employers develop an employment equity plan with timetables and numerical goals, and designated the Canadian Human Rights Commission as the enforcement agency (Employment Equity Act of 1995, sections 28–31).Footnote 6

The origins and development of employment law in Canada show that feminist women’s groups, inspired and influenced by international developments such as declarations and conventions, were influential, at least initially, in keeping economic equality for women on the public agenda. Both Conservative and Liberal administrations were responsive to these demands when movement influence was at its height. Unions and Left parties were not particularly important advocates or catalysts for policy development.

It might appear that unions played more of a role in Israel. The country’s first employment discrimination case was brought by a woman flight attendant, who was supported by the working women’s section of the trade union Histadrut.Footnote 7 Yet apart from this case, there was not much change in women’s legal status at work in the country. Although there was a vibrant set of women’s organizations at the time, they focused more on service provision than on legal advocacy (Sharfman, Reference Sharfman, Nelson and Chowdhury1994; Mlundak, Reference Mlundak2009).

The main period of development of equal employment law in Israel occurred only later, in the mid-1980s, when a new focus on legal discrimination in many areas, including employment, emerged (Mlundak, Reference Mlundak2009). March of 1982 marked the formal establishment of the organization called the Israeli Feminist Movement, founded to achieve full equality between women and men and to eliminate discrimination in all areas of life, including employment (Sharfman, Reference Sharfman, Nelson and Chowdhury1994, p. 387). The mid-1980s saw the creation of the Legal Center for Women’s Rights in the Israeli Women’s Network, another major multipurpose feminist organization. With a combination of volunteer lawyers and staff, this center advocated legal change both through the Israeli Parliament (the Knesset) and the courts. Perhaps not surprisingly, the main developments on employment discrimination occurred in the late 1980s, with the 1987 Equal Retirement Age (Male and Female) Employees Law, the 1988 Equal Employment Opportunities Law, and the development of a more robust sexual harassment regime through amendments to the Civil Code (1990) and the 1995 amendment to the Equal Employment Opportunities Law (Halperin-Kaddari, Reference Halperin-Kaddari2003; Mlundak, Reference Mlundak2009; Raday, Reference Raday2009).

The South African Constitution, adopted in 1996, includes many guarantees against gender discrimination, largely reflecting the influence of the feminist advocates (Goetz, Reference Goetz1998). Women prevailed even in the face of advocacy by traditional leaders from the rural areas (Gouws & Galgut, Reference Gouws and Galgut2016). During the process of negotiation over constitutional provisions, the Women’s National Coalition wrote up an agenda for policies supporting women’s rights, called the “Charter for Effective Equality,” which came to be called the Women’s Charter. These included guarantees against gender discrimination (Article 9 of the 1996 Constitution) and, separately, guarantees of freedom to choose a trade, occupation, or profession or join a union (Article 22) (For discussion see Cotter, Reference Cotter2004, pp. 126–7). Article 181 establishes, among other things, the Commission for Gender Equality, and the functions of this body are laid out in Article 187 as including monitoring, investigating, lobbying, and reporting on gender equality.

During the first five years after the adoption of the 1996 constitution, feminist activists kept up the pressure, demanding further action on their agenda. The women’s section of the African National Congress (ANC) worked to ensure that the proposals contained in the Women’s Charter were implemented by backing, for example, the 1998 Employment Equity Act. This Act was championed by activists outside of parliament but had a more mixed reception among women parliamentarians, who split along party lines. Though the women’s section of the ANC supported the bill, both the opposition National Party and Liberal Party, including women members, opposed it, seemingly due to resistance to race-based affirmative action (Hassim, Reference Hassim2003).

In the United States, feminist organizing has also been critical to advancing women’s rights in employment, even though the adoption of the 1963 equal-pay act and the inclusion of sex discrimination in the 1964 Civil Rights Act came before the height of feminist organizing (Hoff, Reference Hoff1991). Both of these early measures were linked to feminist organizing behind the scenes and to activities by feminist bureaucrats and legislators to some degree,Footnote 8 but the feminist movement had not coalesced around a single set of goals at this point, and was divided or ambivalent about these measures in their various versions. Historically, some feminist activists and women’s rights advocates had opposed the eradication of state-sponsored discrimination in labor law, believing that the existence of so-called protective legislation advanced women’s rights. The desire to defend protective labor legislation motivated some feminists to oppose the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).Footnote 9 “Protective” or “prohibitive” labor legislation was also endorsed by male-dominated unions who wanted to preserve their access to jobs and their higher wages (Wolbrecht, Reference Wolbrecht2000).

Racial politics in the United States also complicated the discussion, as opponents of civil rights for African Americans supported the amendment to the Act that included language about “sex” as a prohibited basis for discrimination. For some supporters, including sex was seen as a way to weaken the Act (just as support for the ERA was seen as a way to weaken unions), while for others it was outrageous to prohibit discrimination on the basis of race but not sex, leaving “white women” in particular without any basis for complaining of discrimination. In some ways, passage of this important measure was as contingent on particular personalities (Howard Smith, Martha Griffiths) as on feminist organizing.

This pattern changed in the following decade, however. Governmental reluctance to follow through on the promise to eradicate sex discrimination represented by the Civil Rights Act spurred a wave of protest by feminists that led to important improvements in the legal regime governing women’s work. Indeed, in 1966, the National Organization for Women was formed to demand implementation of these laws, and waged a decade-long battle to give the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (the EEOC, the enforcement mechanism for the Civil Rights Act) the teeth needed to ensure compliance with prohibitions on sex discrimination. In 1967, the first “women’s liberation” group formed in Chicago and hundreds of local consciousness-raising and radical feminist groups began to organize. The same year, the Johnson Administration issued Executive Order No. 11375, which added “sex” to the categories upon which discrimination by federal contractors was not permitted. 1968 saw the formation of the Women’s Education and Action League (WEAL), the organization that filed the first ever sex discrimination lawsuit against the University of Maryland (Hoff, Reference Hoff1991, pp. 236–8). The creation of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women in 1969, and its report, strengthened the feminist movement, bringing disparate regional groups together to form a national movement (Duerst-Lahti, Reference Duerst-Lahti1989; Hoff, Reference Hoff1991).

This ascendant second-wave women’s movement demanded action on women’s rights, creating political pressure that led to the “spate of women’s rights legislation endorsed by the Ninety-Second Congress (1971–3)” (Hoff, Reference Hoff1991). In 1971, then Labor Secretary Shultz issued guidelines requiring all firms doing business with the government to create action plans for hiring and promotion of women. In the same year, Presidential Executive Order No. 11478 condemned sex discrimination by government agencies. Litigation over Title VII increased in the late 1960s, and “numerous lower-court decisions by 1970 not only approved changed EEOC guidelines but also voided a half-century of protective legislation, with Title VII interpretations expanding equal treatment of women in the workplace” (Hoff, Reference Hoff1991, p. 235).

Women’s movements were similarly important for the development of equal opportunity legislation in other advanced democracies. In Norway, a coalition of women’s groups pushed for the adoption of the Equal Status Act of 1978. Initially opposed by unions, and ultimately adopted under the rule of a conservative party, the Act was an important step toward legal equality for women in the workplace (Weldon, Reference Weldon2011). In Australia, the Women’s Electoral Lobby (WEL) was important to the passage of sex discrimination legislation such as the 1976 Sex Discrimination Act (Sawer & Unies, Reference Sawer1996). Swedish women’s groups were also important, alongside other groups, in influencing sex discrimination legislation (Lindvert, Reference Lindvert2007).

In each of these contexts, then, women’s independent organizing was an important part of the story of generating public attention and policy proposals related to women’s legal status at work, prompting the expectation that:

International Norms

Our discussion of the role of feminist movements showed that they often drew inspiration and support from international forces. Women’s movements working transnationally ensured that principles of equal rights were reflected in global treaties and agreements. As mentioned earlier, CEDAW addresses women’s legal status at work in Article 11, which calls on states parties to “take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the field of employment in order to ensure, on a basis of equality of men and women, the same rights.” Similarly, the Beijing Platform for Action, endorsed by the world’s governments in 1995, calls on states to “Promote women’s economic rights and independence, including access to employment, appropriate working conditions and control over economic resources” (Strategic objective F.1) and “eliminate occupational segregation and all forms of employment discrimination” (F.5).

CEDAW ratification provided the impetus for the first EEOL adopted in Japan, mentioned earlier. The Japanese government had originally not planned to sign CEDAW, but eventually caved to pressure and protests from women politicians, women’s groups at home and abroad, and the media (Knapp, Reference Knapp1995). The need to comply with the Convention helped overcome domestic political opposition, particularly from business interests (Simmons, Reference Simmons2009).

Australian feminists were similarly inspired by international events surrounding CEDAW in pursuing an expanded sex discrimination law in 1984 (Lindvert, Reference Lindvert2007). Similarly, as the earlier discussion of Canadian activism suggests, feminists often shaped their domestic legislative priorities in concert with, or relying on, international commitments made by their governments. Such commitments give feminists standing to demand that the government meet its promises.

In Chapter Two, we showed that regional norms and pressures were especially strong mechanisms for the diffusion of international norms on violence. Regarding work, regional mechanisms have been strongest in Europe. As early as 1975 and 1976, the European Economic Community adopted directives calling for equal pay for women and men and for their equal treatment in employment, working conditions, and vocational training, respectively. As European Union law and regional institutions gained strength, states were compelled to modify their domestic institutions to comply with equal rights directives and their progress was monitored by EU agencies (Council Directive 2000/78/EC).

In other regions, transnational mechanisms developed later. For example, the Organization of African Unity member states adopted the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights in 1981 in Nairobi, but the original text lacked specific measures addressing gender discrimination at work. These were affirmed only in 2003, when the Organization of African Unity adopted Article 13 of the Protocol on Women’s Rights.Footnote 10 Though it comes just at the tail end of our study, and therefore was not as well established as the European norms, we consider whether this regional norm in Africa also makes a difference.

Our discussion of international norms suggests that:

H2. National ratification of international and transnational conventions, agreements and declarations, such as CEDAW ratification, should be associated with more expansive legislation on women’s equal status at work.

H3. The presence of regional agreements, like those that apply to EU members and the African Protocol, should be associated with more expansive legislation on women’s equal status at work.

We expect CEDAW to become more powerful in later decades of our study period. Baldez (Reference Baldez2014) argues that the effects of the Convention gradually increased as CEDAW gained legitimacy, its interpretation and application grew clearer, the intrusion of external political considerations (such as the Cold War) diminished, and NGOs became more explicitly involved in the treaty compliance review process. As this suggests, CEDAW ratification is not a single event with immediate impact, but rather triggers a political process that develops over time.

Women’s Policy Agencies

Various studies have identified the role of women’s policy agencies in promoting equal employment legislation. Stetson and Mazur (Reference Stetson and Mazur1995, p. 3) define women’s policy machineries as “any structure established by government with its main purpose being the betterment of women’s social status.” These agencies, often founded in response to feminist demand, are theorized to be influential because they “allow the entrance of feminist ideas into the political debate, promote women’s interests, and give access to the women’s movement” (see also Bleijenbergh & Roggeband, Reference Bleijenbergh and Roggeband2007, p. 440; Mazur & McBride, Reference Mazur and McBride2007; Stetson & Mazur, Reference Stetson and Mazur1995; True & Mintrom, Reference True and Mintrom2001; Weldon, Reference Weldon2002a). During the United Nations Decade for Women (1976–85), approximately two-thirds of member states adopted women’s policy agencies (though of varying strength and prominence) to recommend and promote legal and bureaucratic reforms, and to administer public policies helping women (Sawer & Unies, Reference Sawer1996, p. 1).

The work of these agencies helped put women’s equality on national agendas. Often, directors and staff of women’s agencies lobbied legislators and state officials about women’s concerns. In Brazil, for example, the women’s policy agency in the 1980s (called the National Women’s Council) organized women delegates to the country’s constituent assembly into a “lipstick lobby” to make sure the new constitution upheld women’s rights in a variety of areas (Pitanguy, Reference Pitanguy, Lycklama, Vargas, Wieringa and Pitangui1996). They were successful: One of the first articles upholds the principle of equal rights for men and women and another article (point 20 under Article 7) calls for affirmative action in the form of “protection of the labor market for women through specific incentives, as provided by law.”Footnote 11

The impact of women’s policy agencies has been particularly visible in Australia. Australian feminists formed the WEL, a nonpartisan organization to press women’s policy demands, in 1972. They succeeded in getting a women’s advisor to the prime minister appointed, and then successfully pushed for the creation of the Office of the Status of Women (Sawer & Unies, Reference Sawer1996, pp. 4–5). Australian “femocrats” were able to secure numerous policy changes, primarily during periods of Labor governments. In 1975, the Sex Discrimination Act was passed, which created a complaints-based enforcement process. Ratification of CEDAW gave the government a basis for federal legislation on women’s rights (Sawer & Unies, Reference Sawer1996, p. 9). The 1984 Federal Sex Discrimination Act (Cotter, Reference Cotter2004, p. 96) created a Sex Discrimination Commissioner to oversee implementation. This year also saw the first women’s budget, and public service reforms introduced equal opportunity programs. The enforcement agency (HREOC) was charged with inquiring into complaints and carrying out research and education. In 1993, the provisions on sex discrimination were strengthened in the Commonwealth Sex Discrimination Act.

In some countries, as we noted in Chapter 2, women’s policy agencies are poorly designed, lack resources, and wield little influence or expertise. They may be mere window dressing or symbolic reforms aimed at making it look like action is being taken, when in fact nothing is being done. But elsewhere, agencies are important centers of expertise and resources, providing support to women’s advocacy groups and offering concrete policy proposals (Stetson & Mazur, Reference Stetson and Mazur1995; McBride & Mazur, Reference McBride and Mazur2010, Reference McBride and Mazur2011; Weldon, Reference Weldon2002a). Sometimes, they are given cross-sectoral influence and have access to political leaders. Again, we suggest, drawing on the literature, that policy agencies that are well-positioned and supported are the ones that are most likely to make a difference.

These experiences suggest that:

Left Parties

Whereas the political strength of unions and Left parties may be associated with class policies and other redistributive efforts, it is not likely to be the principal factor behind change in gender status policies such as legal equality for women at work. In fact, unions in some countries have opposed sex equality in the workplace, particularly the eradication of “protectionist” labor legislation. By banning women from certain occupations, such legislation reduced competition for male union members’ jobs (Wolbrecht, Reference Wolbrecht2000). Labor unions have sometimes been criticized for being poor advocates for working women, and Left parties have sometimes failed women more generally, failing to prioritize sex equality when it seems like other considerations may prevail. Both unions and Left parties have become important allies for women’s movements in many places, and on some policies, but on status issues Left parties have not been the instigators of change, and have even at times been opponents of advances in women’s rights.

Statistical Analysis

To explore these relationships and hypotheses, we analyzed the relationship between several independent variables and the dependent variable, our Index of Sex Equality in Legal Status at Work, which sums the index for state discrimination (coded so that less discrimination is better), formal legal equality, and substantive equality measures. Values range from 0 to 17 (though no state has a score lower than 2).Footnote 12 Our models included the factors mentioned earlier (feminist movements, CEDAW ratification, women’s policy agencies, Left parties) as well as several controls, including economic development, degree of democracy, a communist legacy, the presence of religious legislation, women in parliament, and women’s labor force participation. We used random effects regression analysis to take the panel structure of the data into account.Footnote 13 The results of the analysis are reported in Table 3.4.

| Model | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | |||||||

| Strong, autonomous feminist movement | .530** | .490** | .639*** | .492** | .650** | .660*** | .644*** |

| (.224) | (.223) | (.247) | (.224) | (.255) | (.248) | (.246) | |

| CEDAW ratification | .303 | .160 | |||||

| (.364) | (.372) | ||||||

| Regional agreement | 1.615*** | 1.493*** | 1.009** | 1.509*** | .980** | .869* | .994** |

| (.425) | (.434) | (.436) | (.429) | (.453) | (.446) | (.430) | |

| Effective women’s policy machinery | .773** | .098 | .645* | .141 | |||

| (.373) | (.373) | (.382) | (.377) | ||||

| Left party strength (cumulative) | .007 | ||||||

| (.004) | |||||||

| Official Religion | –1.190*** | –1.383*** | –1.211** | –1.256*** | –1.024** | –1.274*** | –1.198** |

| (.446) | (.447) | (.486) | (.448) | (.515) | (.477) | (.484) | |

| High Religiosity | -.076 | ||||||

| (.632) | |||||||

| Muslim Majority | -.786 | ||||||

| (.770) | |||||||

| Catholic Majority | .149 | ||||||

| (.581) | |||||||

| Women in Parliament (%) | .088*** | .094*** | .068*** | .080*** | .068*** | .073*** | .068*** |

| (.019) | (.019) | (.019) | (.020) | (.019) | (.019) | (.019) | |

| Former Colony | 2.002*** | 1.729*** | 1.651** | 1.844*** | 1.529** | 1.442** | 1.577** |

| (.595) | (.550) | (.704) | (.603) | (.739) | (.652) | (.681) | |

| GDP (logged) | 4.451*** | 4.368*** | 4.816*** | 4.289*** | 4.508*** | 4.443*** | 4.727*** |

| (.562) | (.496) | (.738) | (.570) | (.783) | (.755) | (.718) | |

| Communist | 1.064* | 1.521** | .862 | 1.251** | .905 | 1.290** | .920 |

| (.618) | (.627) | (.663) | (.629) | (.694) | (.653) | (.641) | |

| Female labor force participation rate | .026* | .023 | .022 | ||||

| (.014) | (.014) | (.015) | |||||

| CEDAW ratification (Lagged) | 1.275*** | 1.335*** | 1.316*** | 1.313*** | |||

| (.328) | (.332) | (.326) | (.316) | ||||

| Female labor force participation rate (Lagged) | .023 | .016 | |||||

| (.015) | (.017) | ||||||

| Observations | 254 | 258 | 196 | 254 | 196 | 199 | 196 |

| Overall R-squared | .620 | .608 | .645 | .624 | .655 | .637 | .648 |

| Number of Countries | 69 | 70 | 69 | 69 | 69 | 70 | 69 |

Notes: Estimates are from random effects regression models. Standard errors are in parentheses. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10, 5, and 1 percent levels, respectively.

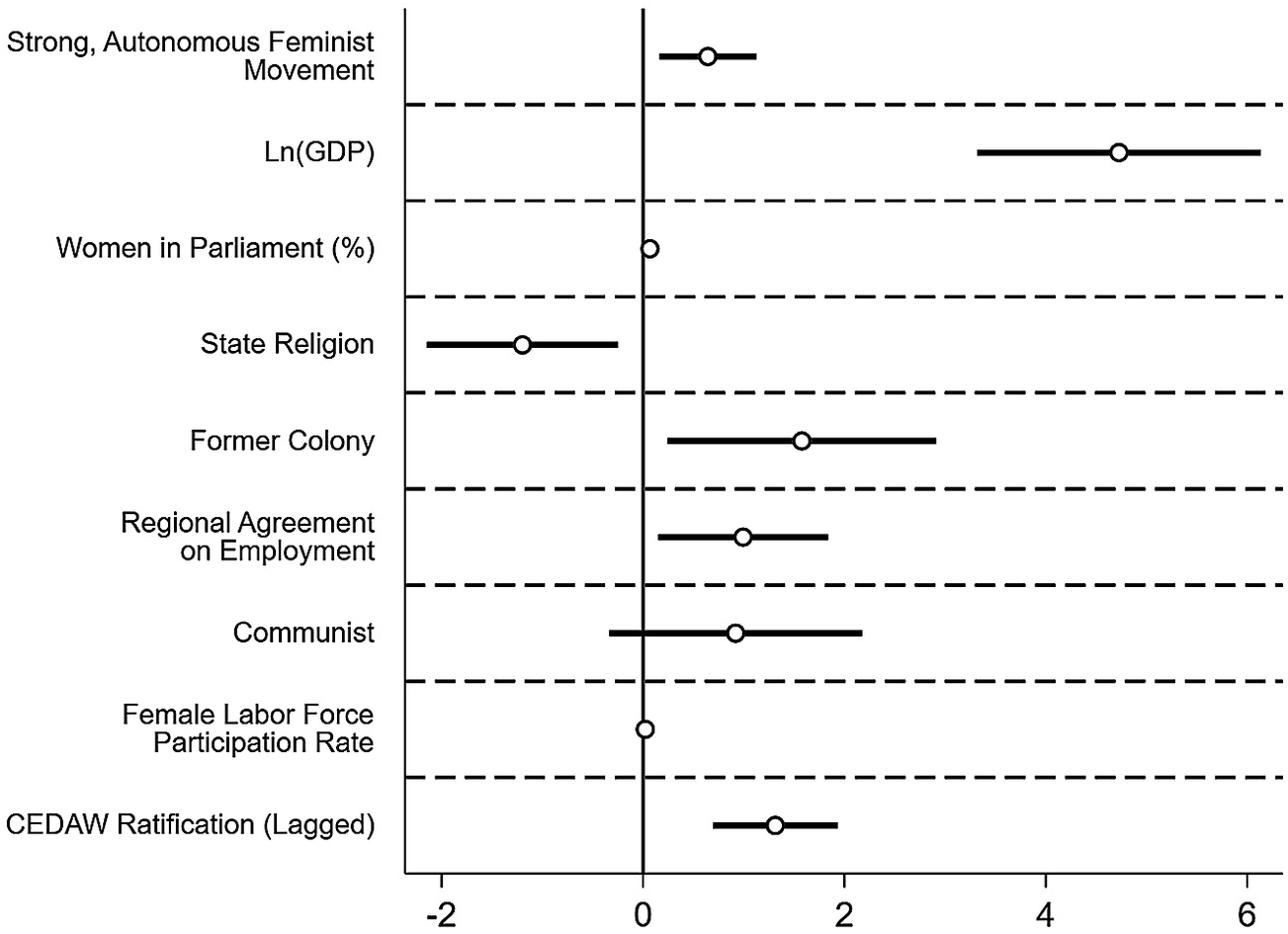

Table 3.4 reports seven models, designed to examine the effects of the various modeling strategies employed. Model 1 includes all the factors we explicitly theorized to be important as well as controls that are necessary to capture the relevant impact in this area (female labor force participation, logged GDP). All models include those factors we have argued were important earlier in the book (religious variables) whenever they are statistically significant. Model 2 introduces those factors thought to be important in the literature (women’s policy machineries) and Models 3 and 4 combine these elements, showing how they perform together. Model 5 demonstrates the impact of a range of religious variables, and Model 6 shows the (non-)impact of Left parties. Model 7 is the same as the first except that the CEDAW ratification variable is lagged. We discuss and compare these models and the variables in the models below. Figure 3.5 presents a coefficient plot of Model 7 in Table 3.4.

Figure 3.5 Coefficient plot of Model 7 of Table 3.4

As we expected, the sandwich model of strong, autonomous women’s movements and international and regional instruments working together to drive policy adoption is consistent with the patterns we see here. The strong, autonomous feminist movement has small but significant and positive impacts in each model. Other variables (such as GDP) have larger effects, but the direction and reliability of the association with women’s movements is important. Exploratory modeling revealed that the association with feminist movements was strongest in developed countries and for the range of policies we call “substantive equality.” This is precisely what we would expect, given our theoretical approach that focuses on movements as uniquely able to articulate women’s distinctive needs, and as key catalysts (but not the sole determinants) of government action to advance women’s legal status at work.

The impact of international norms and regional conventions is also part of the story. The discussion above pointed to CEDAW as particularly relevant, but especially over the longer term. Looking at the relationship between CEDAW ratification and immediate policy change revealed only small, positive but insignificant associations. Going back to our theoretical expectations, as well as the patterns observed in the case we discussed, suggests that CEDAW ratification took some time to have an effect. Our analysis of violence against women in Chapter 2 also suggested that CEDAW had a greater impact over time. Given this lag, we also examined whether looking at CEDAW ratification a decade out made more of a difference. We found that it did, and the lagged CEDAW ratification variable (in Models 6 and 7) proved to be a strong predictor of government action to promote women’s legal status in the workplace, adding additional areas of legal equality.

Regional conventions and agreements can sometimes be even more powerful drivers of women’s rights than international ones, especially when there are strong transnational networks of transnational activists (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2012). The literature points to EU agreements as being very influential for member states, and we find that EU membership has a small but positive and significant association with increased action to promote sex equality, as expected (not shown).

On the African continent, the Charter might also be thought of as an emergent norm. The protocol on women’s rights specifies several legal principles relating to equality at work. While the Charter itself had not reached a “tipping” point, and was not as well established as the EU mechanisms discussed, states that had signed on to the Women’s Rights protocol to the Charter might be thought of as early adopters, or norm-givers in the region. Our coding for regional agreements, then, also captures participation in the African protocol. The presence of a regional norm is associated with greater scope of action promoting women’s rights in employment, and controlling for regional influences helps refine the impact of CEDAW as a specific measure.

In several models (3, 5, 6, 7), both feminist activism and international norms (CEDAW ratification, lagged) are strongly associated with progressive policies. This result is consistent with either additive effects of CEDAW ratification (as we modeled them here) or interactive effects (as we modeled them in Chapter 2). In an additional model (not shown, but available in the replication files), we did not see the powerful effect of mutual magnification so clearly manifest.Footnote 14

Our analysis also offers some insights into why women’s policy machineries sometimes seem to matter and at other times do. The literature would lead us to expect that an Effective women’s policy machinery would be a good predictor of the likelihood of reform, but this relationship did not seem to hold consistently in the data (H2, Models 2, 3, 4, 5). The strength of the relationship (as reflected in the level of significance) between women’s policy machinery and legal equality varied across models, as did the size of the coefficient. Particularly when we controlled for the longer-term effects of CEDAW ratification (CEDAW ratification lagged), the relationship between policy machineries and legal equality appeared to be weaker, with smaller coefficients, suggesting that the effects of CEDAW ratification over time are tapping the same processes leading to establishment of women’s policy machineries, which is entirely possible. As we discussed, many such agencies were established as part of the process of complying with CEDAW, and so may be understood as part of the same phenomenon. Where CEDAW or other regional norms are already exerting an effect, the impact of women’s policy machinery may be less dramatic.

Our framework also leads us to expect that Left and labor parties are not associated with action on sex equality in this area. To explore this hypothesis, we investigated whether the strength of Left parties was associated with greater sex equality in laws governing women’s work (H4). Many scholars have used the strength of Left parties as a proxy for labor mobilization (e.g., Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). We found only statistically insignificant associations between Left parties in government and greater sex equality, whether we used a dummy variable for presence of a Left party (not shown), a measure of union density (available only for a smaller number of countries) (not shown), or a more refined measure of Left-party power capturing all the seats controlled by Left parties in the legislature and the cumulation of such influence over the decades (Model 6). None of these specifications revealed stronger relationships. We also tried other measures (such as potential labor power) and still failed to find a relationship (not shown).Footnote 15 As this suggests, there is no strong or statistically significant relationship between Left parties and sex equality laws, especially compared to the effects of women’s movements and international institutions. This result conforms to our expectations about women’s movements mattering more than Left parties for “gender status” policy issues.

We also expected religious factors to be less important here. This was true for most religious variables, but the impact of a constitutionally established religion did appear to have a consistently and significantly negative effect, being associated with about one fewer area of government action. Other religious factors, such as religiosity or religious denomination, had no association, as expected. This is in sharp contrast to other areas we have examined, where religious factors, regardless of the specific operationalization, showed consistently negative and frequently significant associations – effects that were robust across a variety of types of religious indicators and regardless of measure. The impact of constitutionally established religion here may be more reflective of the continuity of general institutional legacies associated with lack of change in the area of women’s rights, rather than religion per se.

The analysis of the variable for communism is even weaker. In the case of VAW, we found that communism suppressed women’s organizing and indirectly delayed action on women’s rights. For doctrinal policies, we expect (and find, in Chapter 4) that communist efforts to reduce the influence of religious institutions produced lasting effects on women’s rights. Such powerful, large, and consistent effects are not in evidence here, even though one might think that a communist legacy would be more direct for a work-related area like women’s legal status at work. We would think that communism would have had a mixed impact in this area, associated with the greater likelihood of reform of religiously inspired restrictions on women’s rights, but with support for formal egalitarian measures, and more weakly associated with substantive equality. The experience of communism was mostly associated with legal reforms in the expected direction (positive), but effects were small compared to the associations observed in other areas (see our analysis of family law) and the variable was significant in only a few models (Models 2, 4, and 6).

The percentage of parliamentary seats occupied by women was consistently significantly and positively associated with greater equality in laws governing the workplace. Differences over time and across countries of one standard deviation are associated with a bit less than one additional point on the scale. This suggests that a change of one standard deviation (ten percentage points more parliamentary seats occupied by women) would be associated with almost one additional sex equality measure, or area (or a bit less: .09*10= .9). Changes of such magnitude are rare, however, even over a decade, perhaps accounting for why the literature rarely points to women in government as a key element driving sex equality law in this area. A larger proportion of women in the legislature may make policy processes more amenable to the adoption of laws promoting women’s rights in the workplace (or vice versa), especially together with other actors and influences advocating such change, such as feminist movements, women’s policy agencies, and international and regional norms.

Some of the control variables exhibited less expected, if significant, results. A colonial experience was associated with greater sex equality as well, which was not expected. Perhaps this is the other side of the effect of constitutionally established religion, suggesting that discontinuities create opportunities for reform while continuities impede them when it comes to women’s rights in the workplace. Democracy level, using Polity measures, had no relationship at all with sex equality in workplace laws (not shown).

Although the positive impact of logged GDP was in the expected direction, the impact was more significant than one might have expected. National wealth, per capita, appears to have the strongest and largest association with legal equality than any other variable in the model. With a standard deviation of 1.09, a one-SD change in the variable is associated with about four or five additional areas of sex equality. For a dependent variable with a range of 17, this is a sizable effect (though clearly, other factors are also involved). Functional explanations are tempting to explore. Greater wealth translates into more economic opportunities for women and more demand for legal reform. Such a relationship should be picked up by the measure of female labor force participation, but that variable does not add much. Modernization explanations are also tempting, but one would expect to see stronger associations with religiosity and female labor force participation on that score. Also, the most prevalent legal barriers to women’s work are in the MENA region – a wealthier, if more religious, region. One conclusion might be that in wealthier countries, more women are in the paid labor market and so women’s movements focus more on these guarantees, while in developing countries, the informal nature of women’s work makes legal guarantees pertaining primarily to formal work less of a priority. Still, one would think that women’s labor force participation would be a proxy for this explanation as well. Nor can GDP be seen as a proxy for state capacity, which also seems to perform poorly in our models (not shown).

In the main, then, the results of statistical analysis for this issue-area conform to our expectations about the importance of autonomous feminist movements for a “gender status” policy issue such as women’s legal status at work. Since legal status is an issue affecting all women, regardless of their class background, ethnic identities, and other affiliations, and since it involves change in the meaning of women’s roles, we expected that autonomous feminist organizing would be associated with more expansive policies. We do not expect this to be the case with issues such as parental leave and childcare, which we will turn to in a later chapter. Though feminist movements care about, and have mobilized around, these issues, a broader coalition and more conducive contextual factors are necessary to initiate welfare state expansion and other changes in state–market relations.

Conclusion

Although this area of women’s rights relates to their economic autonomy and well-being, it is primarily a question of legal status and less one of class. For this reason, autonomous feminist organizing is a key driver of change, with international conventions adding weight to women’s claims. In addition, especially over the long term, international and regional norms as expressed in conventions and other agreements strengthen domestic actors seeking change and are particularly influential in those contexts where dependence on the international community is greater (for example, those countries more dependent on foreign aid). As we will see, however, when advancing gender equality fundamentally challenges the organization of state–market relationships, the story becomes quite different. We turn to this next dimension of economic rights in Chapter 5.

Are legal reforms sufficient to achieve economic equality? In Western countries, equal opportunity policy was perceived “simultaneously as a success and a failure” (Mazur, Reference Mazur2002, p. 82). Though equal legal status was achieved on the books, women did not gain parity with men in pay, organizational hierarchies, or meaningful work. This suggests that change in women’s legal status alone has not been enough to create conditions for economic equality. Though such policies shape the rights and circumstances of women in the workplace, they do not address the social conditions outside of wage work that shape women’s choices and employer decisions. To address such conditions, feminist activists have lobbied for an expansion of those social policies that help to make wage work and caregiving more compatible (work–life balance or reconciliation policy). In the next chapters, we focus more on the family, studying both family law (Chapter 4), which we characterize as a “doctrinal policy,” and publicly funded parental leave and childcare (Chapter 5), which we characterize as “class policies” that allocate public resources to alleviate the reproductive labor the gender system assigns to women as a class. Such policies alter state–market relations to help women (and men) simultaneously meet their caregiving and wage-work responsibilities.