1. Introduction

The petition system of representative bodies is one of the most conventional methods by which citizens can convey their desires (Bochel, Reference Bochel2012). Petitions can be presented to various governmental bodies, encompassing legislative and executive branches, or both simultaneously, which means that petitioners can choose their addressee from among public entities that have direct administration over a particular subject and call on them to act. However, because legislative bodies are expected to exert political influence ‘by the ‘power of convincing arguments’ and by the means of institutional reputation’ to achieve the petitioner's purpose (Lindner and Riehm, Reference Lindner and Riehm2011: 3), citizens also have filed petitions that concern matters under both the legislature's authority and the jurisdiction of other government departments.

Scholars have posited that petitioning the legislature may be an effective strategy for advancing a particular campaign over the long term, or, more generally, for increasing awareness of issues and forging networks with political actors (Bochel, Reference Bochel2012, Reference Bochel2013, Reference Bochel2020; Riehm et al., Reference Riehm, Böhle and Lindner2014; Angus, Reference Angus2018; Leston-Bandeira, Reference Leston-Bandeira2019; Rosenberger et al., Reference Rosenberger, Seisl, Stadlmair and Dalpra2022). At the same time, inquiries in numerous democracies have examined whether legislatures have genuinely implemented the policy contents of successful petitions. Motivating these inquiries is the fact that the act of legislative adoption, which represents the expression of parliamentary majority support for the petition's content, is typically not legally binding and, thus, passing a petition does not guarantee that administrative bodies will respond positively to it (Takeuchi, Reference Takeuchi1973; Leston-Bandeira, Reference Leston-Bandeira and Norton2002; Palmieri, Reference Palmieri2008; Riehm et al., Reference Riehm, Böhle and Lindner2014). For example, in 2015, Japan's Mie Prefectural Assembly adopted a petition that requested the enactment of an ordinance to regulate the importation of construction waste soil. Yet three years later no progress had been made. Dissatisfied with the outcome, the petitioner submitted the same request to the governor in December 2019.

Using observations at the Japanese prefectural level, we examine whether adoption by the legislature over the short term is associated with the achievement of petition goals. Because of formal power imbalances (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2009: 14; Yamamoto, Reference Yamamoto, Yongnian, Fook and Wilhelm2014: 155), local assemblies rely on the governor's branches for assistance in budgeting and policy implementation. Consequently, the adoption of a petition by a prefectural assembly does not automatically lead to its implementation; instead, adoption requires the cooperation of other organizations, such as administrative departments and agencies. Determining whether prefectural petitions in Japan are implemented after legislative adoption is often difficult.

Governors hold the exclusive power to draft budgets, and 97% of bills are introduced under the name of a governor (Hasegawa, Reference Hasegawa2017: 112). Many Japanese believe that significant decisions regarding legislation in Japanese local politics are reached outside of regular sessions and, consequently, that the assembly's roles in the legislation is often ‘shielded from public view’, making it difficult for petitioners to ascertain whether their petitions influence policymaking (Brett, Reference Brett1957: 33). Whether in Japanese local politics there is a correlation between an assembly's formal adoption of a petition and that petition's subsequent actualization by executives is a subject of ongoing speculation and debate.

Studying the petition process in Japan is advantageous because much information is available about petitioners. Consequently, we carry out a quantitative study using extensive data.Footnote 1 We designed our original mail survey after examining disclosed petition documents. Survey respondents were former petitioners – individuals who we expect had the most comprehensive knowledge of petition-related information, including whether the content of petitions was eventually realized. Our approach helps us overcome the difficulty of collecting relevant data. This challenge, recognized by others (Imabashi, Reference Imabashi1980; Riehm et al., Reference Riehm, Böhle and Lindner2014), is not limited to Japan. As Riehm et al. (Reference Riehm, Böhle and Lindner2014: 96) have observed, ‘there is no summary information on how often the Federal Government has followed the vote of the German Bundestag on a petition’.

Suspecting that policy implementation can be advanced by political activities other than petitioning (e.g., contacting the governor or the mass media), we assessed the correlation between petition adoption and policy implementation while controlling covariates that could affect implementation. Key findings reveal that petitions are likely to be realized if the legislature expresses its approval; this includes policies within the purview of the Governor's branches. Our findings regarding petitioners' efforts to ensure that their desires (in addition to being formally submitted) are eventually adopted by a legislative body could point the way towards greater short-term policy responsiveness outside of election seasons. Our review of several specific petition cases also suggests that disclosing petition-related information, such as progress reports for adopted petitions, could potentially improve the accountability of responsible administrative departments or agencies. These conclusions might allow local assemblies to re-evaluate their ability to collaborate with or control a governor through the petition process in Japanese politics.

2. The Japanese petition system and its policy influence

The term ‘petition’ in Japanese can be broadly translated into seigan or chinjyō. Our study focuses exclusively on seigan because our emphasis is institutionalized petitions. Chinjyō, characterized as non-statutory, predominantly refers to political requests as de facto actions.Footnote 2 Figure 1 depicts the typical sequence of events through which petitions, known as seigan, are processed in Japanese prefectural assemblies.

Figure 1. Petition process in Japanese prefectural assemblies.Footnote 3

In the Japanese seigan system, regardless of whether one is petitioning a local assembly or the National Diet, the petitioner is required to secure sponsorship from one or more elected members of the legislature before submission. In Japanese, securing sponsorship is known as shōkai, or ‘introduction’. The submitted petitions are initially discussed and voted upon within the relevant committee and then at the plenary session. If at the plenary session petitions to the local assemblies are adopted with a majority vote, they are typically addressed through one of two methods. The first approach involves passing and sending a resolution to the National Diet or the relevant government ministries. The second method is to forward the contents of the petitions to the administrative departments or agencies of the prefecture. In the latter case, progress reports are commonly provided to the assemblies before the next session, as stipulated in Article 125 of the Local Autonomy Act. It is worth repeating, however, that due to the non-binding nature of petition adoption, this step may become a mere formality if administrative officials in the relevant departments or agencies fail to acknowledge their ability to act or are unwilling to do so.

In previous comparative studies scholars have described the intermediate role that legislators play in the petition's submission stage as the ‘member of parliament (MP) filter’ or the ‘sponsorship model’ (Riehm et al., Reference Riehm, Böhle and Lindner2014: 18–19). In the absence of a specialized committee for petitions, the petition system in this sponsorship model plays a relatively passive role in influencing policy. This system is analogous to the paper petitions in the UK House of Commons before 2015, which were characterized as a ‘descriptive system’ that emphasized recording people's desires. In contrast, petition systems in devolved legislatures, such as the Scottish Parliament, tend to have a greater influence on policy (Bochel, Reference Bochel2013). Furthermore, an analysis by Riehm et al. (Reference Riehm, Böhle and Lindner2014: 205–206) indicates that these systems may be less responsive and less obligatory than those that have a petition committee but no MP filter.

Nonetheless, Japanese prefectural assemblies have voted on and adopted a considerable number of petitions. Japanese prefectures have a demonstrated proactive tendency to adopt petitions from their citizens (Todofuken Gikai Teiyou Vol. 3–Vol. 14). Over four years, following the return of Okinawa Prefecture to Japan (1972–1976), the 47 prefectural assemblies adopted 34% of the 10,172 petitions submitted to them by the public. Since then, the number of petitions submitted has gradually declined, with the average annual number approaching 968 between 2009 and 2018. At the same time, the adoption rate has remained relatively stable at 34%. Notably, this rate is very high compared to the rates observed during the same period in the House of Representatives (9%) and House of Councilors (5%).Footnote 4 This high rate of adoption raises the question: How often are these adoptions translated into action?

Several studies have examined the effectiveness of Japan's legislative petition process, with a particular focus on local assemblies. These include scholarly studies of Japanese local assemblies from the post-war Showa period (1945–1989), although these are largely confined to studies of individual municipalities. Some researchers observe that petitioners believed their petitions were relatively effective (Mitsui, Reference Mitsui1976; Mitsui and Kawamura, Reference Mitsui and Kawamura1978). For example, Mitsui and Kawamura (Reference Mitsui and Kawamura1978), in a survey of 30 groups in the Toshima Ward, found that 61.5% of respondents believed that filing a petition effectively solved their problems. It is unclear, however, whether petitioners used the successful implementation of a petition as the sole criterion for evaluating its effectiveness or whether they employed a different standard for their assessment.

Meanwhile, investigations of the percentage of petitions implemented following legislative adoption reveal inconsistent results that range from 22% (Takeuchi, Reference Takeuchi1973) to 80% (Imabashi, Reference Imabashi1980). Takeuchi (Reference Takeuchi1973) analysed petitions from Setagaya Ward that concerned living conditions, such as improving roads, rivers, and parks. Of the 140 petitions sent to the executive branch after adoption, only 47% resulted in progress reports. Additionally, less than half of the petitions with reports proposed specific measures. Imabashi (Reference Imabashi1980), who recognized the limitations of relying solely on progress reports, made direct inquiries to administrative officials a year or more after the adoption of particular petitions. Imabashi found that more than half of the petitions in Mito City from 1977 to 1978 were partially or fully implemented, while approximately 10% of the adopted petitions were incorporated into the city's three-year execution plan. However, given that administrative officials were asked to describe their own actions, there is a potential for social desirability bias, wherein the respondent's answer suggests they handled the petitions' requirements with the utmost attention, whether or not they did so.

These discrepancies and limitations in previous research suggest that to reconcile conflicting claims and achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of the petition process in Japan, a focused study of two key issues is needed. First is the challenge of obtaining data about the policy result of petitions following legislative decisions (Imabashi, Reference Imabashi1980: 10; Riehm et al., Reference Riehm, Böhle and Lindner2014: 96). To correctly reflect the entire population of the petition system, we would need information about the frequency of the realization of both adopted and non-adopted petitions. But non-adopted petitions are not reported, and so, for the purpose of this study, existing government documents have only limited utility.

The second critical issue concerns the potential for confounders to bias the results. In this case, the confounding variable is any variable related to both the assemblies' adoption of a petition and the petition's implementation of it. Examples include a petitioner's aggregate political activities and the relationship between the legislator who sponsors the petition and the governor. This issue has previously been identified in the literature, including in Seigan Sēdo to Sono Kōka [Petitions System and the Effectiveness] 1950, a Japanese publication, and in other publications (Leston-Bandeira, Reference Leston-Bandeira and Norton2002: 142; Hough, Reference Hough2012: 487). Perhaps the idea that petitions are ineffective persists because, to date, neither of these two issues has been adequately addressed. Thus, further examination of the issues is warranted.

3. Case studies and hypotheses

3.1 Empirical hints: petition cases in the Akita Prefectural Assembly

To provide a deeper understanding of how petitioners and legislators engage with the petition process, we now examine petitions brought before the Akita Prefectural Assembly, which called upon the prefectural government to take action to raise awareness of breast cancer. Our objective is to identify the mechanisms that facilitate or impede the successful adoption and implementation of petitions. We examine the Akita cases because they appear to have been submitted independently of interest groups and political advocacy groups. Additionally, after the petition's wording was subtly modified, the attitudes of political parties towards the petitions shifted, suggesting that the Assembly's position was not predetermined and that the decision-making process was not heavily influenced by extremist ideology. Information about the petition was collected from several sources, including official documents, such as the assembly minutes, and in-depth interviews with members of the Akita Prefectural Assembly, the secretariat, and the petitioner.Footnote 5

In June 2016, a resident of Akita Prefecture presented two petitions to the Akita Prefectural Assembly. The first asked the government to encourage employers to include breast cancer screenings in employees' medical checkups and educate employees about the disease's symptoms and self-examination techniques. The second petition called for the government to promote breast cancer-related education for female high school students.Footnote 6 The petitioner's motivation for filing these petitions stemmed from the loss of his daughter in 2015. Her death from breast cancer prompted him to reflect on the lack of education she received about the disease during her lifetime and the absence of a breast cancer screening component in her workplace health checkup plan.

The petitioner, a supporter of the Social Democratic Party in the Akita Prefectural Assembly, asked Hitomi Ishikawa, a member of that party, to sponsor his petitions. Although the Social Democratic Party was favourably regarded by the governor, it was a minority party: the party held only 9% of the Assembly's seats. To pass, the petitions needed the support of other factions, particularly the Liberal Democratic Party, which held an absolute majority in the assembly. Therefore, Ishikawa personally visited each faction, including the Liberal Democratic Party, elucidating the petitions' points and soliciting support before the petitions were referred to the relevant committees. Additionally, she reached out to members of the nonpartisan assembly group on cancer (Akita-ken gan taisaku suishin giin renmei), asking them to endorse the petitions. Meanwhile, the petitioner visited the Office for Cancer Control of the Akita prefectural government to inquire about its position before the committee deliberated. He also wanted to personally articulate his request to those working in the office that had jurisdiction over cancer-related matters.

Despite these efforts, the committee failed to adopt the petitions, which were left for ‘continuing review (keizoku shinsa)’. Nevertheless, some assembly members attempted to sustain the discussion. At an interpellation session with the governor in December 2016, Ishikawa advocated for the need to educate young women about breast cancer. She then asked about the anticipated role of businesses in cancer prevention policy. The governor responded, ‘I have directly urged businesses to create opportunities for cancer screening in the workplace through the Cancer Screening Promotion Council’ (Akita Prefectural Assembly, 2016). In June 2017, Mari Kato, another member of the Social Democratic Party, spoke at the Budget Special Committee about the significance of detecting breast cancer early, posing pertinent questions to the Department of Health and Welfare manager. In September 2018, the petitioner removed from the initial petition wording he felt was not aligned with the views of other factions. He resubmitted it,Footnote 7 and the petition for breast cancer screening during employees' medical check-ups was adopted.

The petition that advocated for breast cancer education in high schools did not advance during the assembly's term because the legislative period expired. It was resubmitted in June 2019. The prospect of the petition's potential adoption was raised in February 2020 following the release of survey findings by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology.Footnote 8 At the time, Akita Prefecture had the highest cancer mortality rate in Japan. The survey also indicated that the prefecture ranked 46th out of 47 prefectures in its implementation of cancer education programmes in schools. The survey results confirmed that the petitioned programme was needed. Ishikawa, the sponsoring member of the petition, highlighted this point during an interpellation session with the Superintendent of the Education Bureau.

In September 2020, members of the Liberal Democratic Party continued to debate the issue in the Education and Public Safety Committee. Of particular concern was the possibility that students would be uncomfortable with the realistic-looking breast model that would serve as an educational tool for physical and visual inspections. Discussants also noted that the self-exam could generate false positives, causing unnecessary anxiety among students. Again, the petition was identified as a subject for ‘continuing review’. Thereafter, the petitioner removed the problematic sections from the petition and resubmitted it in February 2021. In March, the assembly adopted it without further debate.

After the petitions were adopted, neither the petitioner nor the assembly member made any notable attempts to engage in substantial dialogue or pressure the responsible departments of the prefectural government. Instead, they simply waited for the administrative process to end. When the petitions were adopted, the affected departments issued progress reports on both petitions during the subsequent regular session. The report on the first petition revealed that Akita Prefecture had enlisted the Akita Foundation for Healthcare, a specialized organization that provided medical examinations, to disseminate informational leaflets about breast cancer and self-examination methods during workplace health checkups. The petitioner expressed dissatisfaction with this result, noting that it fell short of the original petition's objective of directly encouraging business participation in the policy. Instead, the result was achieved indirectly through medical check-up institutions. According to written records, the decision was intended to increase efficiency in the two medical institutions that conducted most health check-ups in Akita Prefecture. The decision to distribute leaflets to workers, directly inspired by the petition, was distinct from the long-standing Pink Ribbon Campaign that the prefectural government had developed to encourage breast cancer screening among residents. According to the second petition's progress report, breast cancer education would be incorporated into the broader framework of cancer education, leveraging existing policies such as cancer education in schools, which in Japanese are called gan kyōshitsu. The implementation of targeted measures that focused solely on breast cancer education was not adopted.

3.2 Theory and hypotheses

What insights do these practical petition cases offer into the nature of the legislative process during the adoption and implementation of petitions? One might posit that the practice of submitting petitions via the intermediaries of legislators leads legislators to pressure administrative officials to take action once petitions have been formally adopted. However, actual petition cases undermine the expectation that direct political pressure is a mechanism that translates adoption into implementation. In everyday petition cases, such as those concerning breast cancer in Akita, legislators often do not appear to take concrete political action after passing a petition. The observed tendency is not contingent on the party affiliation of the members who sponsor the petition. Eiko Okuno, chairperson of the Policy Research Council of the Federation of Toyama Prefecture's Liberal Democratic Party, has stated that the implementation of the petition after its adoption is primarily driven by the weight of the petition system process rather than by arbitrary political interventions.Footnote 9

Instead, it can be reasonably inferred that the disclosure of the petition process through its written procedure and official records improves the likelihood of petition implementation. These procedures compel related departments to publicly express their commitment to the petitions' purposes. In the petition cases of Akita Prefecture, we find two instances where executive branches were required to communicate their position publicly.

The first occurred during the response of the governor and officials to an assembly member's question in an interpellation session. The second involved progress reports that describe implementation efforts made and planned by the executive branches. Executive branch officials who deal with petitions within the framework of citizens' constitutional and legal rightsFootnote 10 feel honour-bound to carefully examine the implementation of petitions.

Of course, petition progress reports from relevant departments and agencies do not necessarily ensure that immediate petition fulfillment will be achieved. In part, this reflects the fact that such reports are typically issued close to the time of adoption – usually about three months after the petition is adopted in prefectures (Todofuken gikai Teiyou Vol. 14: 119). Given that petitions do not always include requests that can be dealt with quickly (particularly in the case of petitions related to the budget), reports mainly pledge how the officials intend to act going forward. Indeed, a bureaucrat from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications remarked that progress reports tend to refrain from explicitly stating that government departments and agencies are unable to meet petition requests, even when the requests are deemed unfeasible.Footnote 11 Accordingly, reports frequently employ in their descriptions terminology such as ‘plan (keikaku)’, ‘examining (kento)’, ‘will continue to work on (torikunde-iku)’, or ‘will endeavor (tsutomete-iku)’.

As Fry (Reference Fry1995: 187–188) observes, ‘An individual can only be accountable for that which he or she publicly promises to do for or with another (or others).’ A tangible expression of executive branch commitment provides a basis for holding officials accountable for their actions; this is particularly important given that local bureaucrats' actions often occur behind the scenes away from legislative oversight (Kanai, Reference Kanai2018). Complicating matters further, organizations can face intertwined expectations and conflicting accountabilities that negatively impact policy performance (Romzek and Dubnick, Reference Romzek and Dubnick1987; Koppell, Reference Koppell2005; Kim and Lee, Reference Kim and Lee2010). Petitions are initiated by residents or local interest groups and then adopted by a majority of the assembly, reflecting a consensus reached by diverse stakeholders. Petitions that include shared and agreed-upon actions can hold officials accountable and, consequently, improve administrative performance.

However, it is not always clear whether executive departments have acknowledged their duty to embrace the purposes of adopted petitions, particularly when those purposes directly conflict with key government policies. Other petition cases illustrate how progress reports, which are official petition records, serve as evidence of accountability. At a March 2007 press conference, Sukeshiro Terata, the governor of Akita Prefecture, confirmed that a plan of local taxes was needed to implement a programme of childcare and education called ‘Kosodate zei’, and in 2009, he announced his intention to introduce the tax (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 2007). Almost immediately, in June, two petitions opposing the governor's plan were submitted, and in September, the Akita Prefectural Assembly adopted them. In progress reports published in December, ahead of the 3rd opinion polls for residents planned for January (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 2008), the governor and his administration acknowledged, first, that the plan might not fully meet the needs of residents and, second, that further discussion was needed. The report promised: ‘We will review our policy projects based on the needs of Akita citizens and present a vision that clarifies the outlook for financial resources.’

In another example, the Nagasaki prefectural assembly adopted in February 2011 a petition that asked the governor to visit and worship at Gokoku Shrine. The petition, which required the governor to adhere to a specific religious code of behaviour, was potentially problematic because it concerned the complex relationship between religion and government. The petition's progress report indicated that the governor reaffirmed a past decision to favour non-religious memorial services for the war dead. However, he also expressed a willingness to acknowledge and honour in the future the spirits at Gokoku Shrine, stating ‘With regards to the expression of respect and gratitude for the spirits of war enshrined at Gokoku Shrine, it is our intention to respond to the petition at the appropriate opportunity, taking into account the stated purpose of the petition.’

In summary, the process by which petitions are adopted includes documentation that discloses how the petition garnered majority support in the legislature and details the efforts made and planned by governmental departments. As noted above, progress reports do not strictly guarantee petition implementation,Footnote 12 and they usually are provided only once a few months after the petition's adoption. Nevertheless, progress reports indicate the commitment of officials to future efforts aligned with the petition's purpose. Thus, local government records generated during the petition process can pressure executive branches to acknowledge that they are responsible for adopting petitions, and this, in turn, can move these branches towards petition implementation. Consequently, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Legislative adoption of a petition significantly correlates with an increased likelihood of its implementation.

The likelihood of implementation can vary depending on the petition type. We have discussed the potential challenges associated with implementing petitions that call for administrative action by the prefecture. Since bureaus and departments carry out these petitions within the prefectural administration, the assembly can hardly take sole credit for fulfilling the petitioners' requests; in fact, to a large extent they contribute to the realization of petitions only indirectly.

Nonetheless, a petition can call for non-binding resolutions that are designed to encourage an assembly to declare a position on a specific issue. Such resolutions, if adopted, usually are forwarded to the National Diet or central government ministries and agencies. Resolutions express the collective will of the representative body regarding local, national, and global issues (Toki, Reference Toki1982). An example is a resolution submitted by Toyama prefecture in 2020 that encouraged the Japanese government to sign the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Once petitions calling for a resolution are adopted, they encounter less institutional opposition because passing resolutions only requires approval from a majority of the assembly. This leads to the next hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The adoption of petitions that call only for passing resolutions significantly correlates with a greater likelihood of implementation than petitions involving administrative actions.

4. Estimation

4.1 Data

This study, which uses a dataset from a mail survey of petitioners, focuses on the petitions that petitioners individually lodged in prefectural assemblies between January 2019 and March 2020.Footnote 13 We obtained variables related to each petition, including the result of the corresponding legislative decisions, the degree of realization, the type of petition, whether the governor's party sponsored the petition, the governor's stance, and political activities conducted to advance the policy implementation. Table 1 presents the summary statistics of the variables in the data. A total of 31.3% of respondents indicated that their petitions had been either fully or partially realized, while 34.2% reported that they had been adopted.

Table 1. Summary statistics

4.1.1 Dependent variable

We constructed the dependent variable of interest as Realize1 (Y, hereafter), using the variable Realize from the survey. The variable Realize is a petition realization measure that runs as 1 (Unrealized), 2 (Close to Being Unrealized), 3 (Neither), 4 (Somewhat Realized), and 5 (Realized). To simplify interpretation we standardized the variable from a 1 to 5 integer scale to a 0–1 rational-number scale. Thereafter, we defined Y as 1 if realize is higher than 0.51 so that 0.75 (Somewhat Realized) and 1.0 (Realized) is 1, while 0 (Unrealized), 0.25 (Close to Being Unrealized), and 0.5 (Neither) is 0.

Notably, respondents' subjective criteria could interfere in measuring the degree of realization (what it means to be realized and unrealized). To minimize variation in how respondents interpreted the concept of realization, our survey provided specific examples that illustrated the meaning of key concepts. The following example illustrates our approach: ‘What has been the status of your petition since the legislative decision? Please circle the closest of the options that follow: 1. “Realized (The petition was (to be) implemented, budgeted for, or passed as a resolution)”; 2. “Somewhat realized (The petition is under negotiations with relevant departments of the administration, etc.)”; 3. “Cannot say either way”; 4. “Somewhat unrealized (Relevant departments responded that they are willing to consider or make efforts, but no progress has been made, etc.)”; 5. “Unrealized (Relevant departments concluded that it is premature or difficult to implement the petition or refused to pass a resolution, etc.).”’

Our survey also posed an independent question about subjective satisfaction with the petition's effectiveness (apart from the realization status): ‘How effective do you believe petitions are in fulfilling your needs?’ Surprisingly, 79% of the respondents answered they are ‘effective’ or ‘somewhat effective’, while 10% said neither, and 11% responded that they have ‘no effect at all’ or are ‘not very effective’. In other words, most petitioners expressed a certain level of satisfaction with the effectiveness of their petition action. This result is 30 percentage points higher than the rate of positive responses regarding the degree of realization. This suggests that the realize variable is not simply a projection of the petitioners' subjective satisfaction with their petition action.

4.1.2 Independent variable

Our main independent variable of interest is Adopt1. In response to the question ‘What was the legislative decision of the petition? Please circle the closest one,’ those who responded to our survey were asked to choose between six options: ‘Adopted’, ‘Partially Adopted’, ‘Undelivered’, ‘Partly rejected’, ‘Rejected’, and ‘Withdrawal’.

We primarily rely on Reference TsujiTsuji's (2006: 246) research to classify and define legislative decisions about petitions. ‘Adopted (Saitaku)’ means that the majority of the assembly has approved the entire content of the petition, while ‘Rejected (Fusaitaku)’ indicates that none of the petition's content garnered support from the majority. ‘Undelivered (Shingi miryō)’ refers to a state in which no portion of the petition has been either adopted or rejected. Some local assemblies prefer to leave the petitions as ‘undelivered’ rather than directly rejecting them. According to Hayashi (Reference Hayashi2019), some legislatures prefer this practice because it shows consideration to legislators whose reputation could suffer if a petition were rejected.

Furthermore, some assemblies decide to adopt or reject only parts of a petition. ‘Partly adopted (Ichibu saitaku)’ means that only a portion of the petition is adopted. Likewise, ‘Partly rejected (Ichibu fusaitaku)’ denotes that only a portion of the petition is rejected, while the rest remains undelivered. Additionally, petitioners can withdraw their submissions before obtaining the legislature's official deliberation results. A common reason for the ‘withdrawal (Torisage)’ of a petition is the desire to make revisions and resubmit, particularly when assemblies have kept the petition undelivered and postponed a decision.

Adopt1 and Y are constructed in the same manner. We used the variable Adopt, which offers the following options: 1 (Rejected), 2 (Partly Rejected), 3 (Undelivered; no part of it being adopted or rejected or Withdrawal), 4 (Partly Adopted), and 5 (Adopted). We rescaled it from a 1–5 integer to a 0–1 rational number scale and defined Adopt1 as an indicator of a partly or fully adopted petition, as applied to the definition of Y.

Furthermore, we included a petition type indicator, Action, to assess whether the degree of realization changes between the two types of petitions. In Japan, the two principal methods by which assemblies address petitions are by requesting action from another governmental body or by issuing a resolution. Our survey asked respondents, ‘Which of the following applies to the petition by you or your organization submitted? Please circle all that apply.’ If a respondent selected the option ‘action by prefectural administration’ (todōfuken gyōsei ni kansuru seigan), the Action variable is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, if the respondent only selected ‘resolution or written opinion’ (ikensyo matawa ketsugi no hatsugi), the Action variable is set to 0.

We also considered six covariates that could affect the realization of petitions. We controlled, first, the prefectural fixed effectFootnote 14 and, second, the timing of submitting the petition (to control the time effect).Footnote 15 We also controlled, third, a political factor: a dummy variable indicating whether any assembly member from the governor's ruling party sponsored the petition (Sponsor_yotou).Footnote 16 An analysis of petitions from several prefectural assemblies in the late 1990s suggests that sponsorship by the governor's ruling party was closely tied to the results of the adoption vote (Tsuji, Reference Tsuji2006). Furthermore, in more than half of the prefectures, when preparing the budget, it is customary to invite the ruling party to submit requests (Kobayashi et al., Reference Kobayashi, Nakatani and Kim2008: 34). We infer from this practice that petitions sponsored by members of the governor's party in power benefit from a certain level of cooperation from executive branch officials.

We also controlled the types of political activities that petitioners engage in other than petitioning. For instance, petitioners who have direct contact with administrative officials have the opportunity to persuade those officials that the causes petitioned are necessary and significant. Conversely, efforts to attract media coverage may have a negative correlation with the realization of petitions over the short term because such activity is often geared towards mobilizing potential petition supporters as part of broader social movements (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2016). Consequently, we included, fourth, a dummy variable that indicates concurrent political activities, including contacts with the governor and/or local administrators (Inside lobby); fifth, contact with members of the National Diet (Diet lobby); and sixth, contact with/exposure to the mass media, posting of opinion advertisements, and/or holding a rally (Outside lobby).

To generate dummies, we asked, ‘How often have you taken the following actions to realize the case you are pursuing in this petition?’Footnote 17 These variables are assigned a value of 1 if the petition indicates ‘very often’ or ‘often’ in any of the political activities and 0 if it indicates ‘sometimes,’ ‘rarely,’ or ‘not at all’ in all of the activities.

4.2 Econometric model

We regressed the following model to estimate the connection between the petition's adoptions (Adopt1) and their implementation (Y):

Where the time dummy f captures the time-fixed effects, prefecture-specific dummy c captures the prefecture-fixed effects, and X is the set of covariates defined in the various contexts. We included petition indicators Adopt1 and Action with their interaction terms so that we do not have to split the sample. We calculated the average marginal (partial) effects for each petition type to measure the correlation between a legislature's adoption of petitions and ex-post policy implementation.

The model specification with this interaction term allows us to estimate the parameters of interest without splitting the sample. For example, the average impact of adoption for petitions asking for administrative action (Action = 1) is identified by β 1 + β 3. Similarly, the impact from the other subgroup asking only for non-binding resolutions (Action = 0) is given by β 1. The overall effect of both types of petitions is estimated by β 1 + β 3 ⋅ E(Action). Since we are expecting larger magnitudes from the petitions with non-binding resolutions than in administrative action cases, we expect β 3 to be negative. Because the overall impact is a weighted average of two types, we also assume that overall estimates should fall somewhere between the impact from the non-binding resolution subgroup and the impact from the administrative action subgroup.

5. Results

5.1. Estimation result

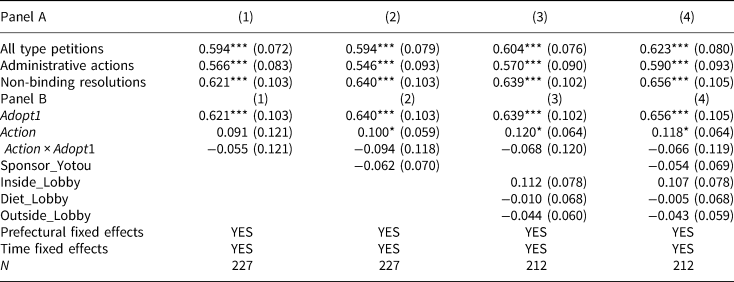

Table 2 presents the estimation results for each of the model specifications. Panel A shows the parameters of interest, while Panel B presents the estimated coefficients of our main regression. Before turning to the main result, we briefly discuss how we constructed Panel A. As noted in the previous section (4.2. Econometric Model), the estimate for the non-binding resolutions subgroup is measured by the coefficient of Adopt1 ($\widehat{{\beta _1}}$![]() ). For example, column (1) of Table 2 shows that Non-binding Resolutions of Panel A has the same number as Adopt1 (0.621) in Panel B. The result for the administrative action subgroup is calculated by summing the Adopt1 and Action coefficients ($\widehat{{\beta _1}} + \widehat{{\beta _3}}\;$

). For example, column (1) of Table 2 shows that Non-binding Resolutions of Panel A has the same number as Adopt1 (0.621) in Panel B. The result for the administrative action subgroup is calculated by summing the Adopt1 and Action coefficients ($\widehat{{\beta _1}} + \widehat{{\beta _3}}\;$![]() ). From Table 2 column (1), one can easily confirm that the summation of two coefficients (0.621 and −0.055) sums up to the Administrative Actions result (0.566). Finally, the overall impact for both types of petitions is a weighted average of two coefficients, where the interaction term is multiplied by the share of administrative action petitions. Since the share of administrative action petitions is approximately 0.4889 in Table 2 column (1), the All Type Petitions estimate fits into the middle of the other two subgroups (0.621 − 0.055 ⋅ 0.4889 ≈ 0.594).

). From Table 2 column (1), one can easily confirm that the summation of two coefficients (0.621 and −0.055) sums up to the Administrative Actions result (0.566). Finally, the overall impact for both types of petitions is a weighted average of two coefficients, where the interaction term is multiplied by the share of administrative action petitions. Since the share of administrative action petitions is approximately 0.4889 in Table 2 column (1), the All Type Petitions estimate fits into the middle of the other two subgroups (0.621 − 0.055 ⋅ 0.4889 ≈ 0.594).

Table 2. Regression analysis of the relationship between adoption and realization

The standard errors are in parentheses. *** P < 0.01; ** P < 0.05; * P < 0.10; The OLS standard errors are heteroscedasticity-robust.

As is evident in Panel A, irrespective of the type of petition (whether it requires non-binding resolutions or administrative actions) or model specification, the adoption of the petition is significantly correlated with its realization. The result, shown in the first row regarding All Type Petitions, reveals that adopting the petition can increase the probability of its realization by about 60 percentage points, with estimates ranging from 0.594 to 0.623. Across the models from (1) to (4), their significance at the 1% level does not rely on covariate selection on the governor's ruling party sponsorship and various lobby activities. Similarly, the results of both Administrative Actions and Non-binding Resolutions in the second and third rows show significant correlations between the adoption of petitions and their realization. This indicates that the result of All Type Petitions is supported by the significant correlation for both types.

For a petition requesting a specific administrative action, the overall coefficients are weak compared to those for All Type Petitions, but the adoption still has a strong correlation with their realization. For example, regarding model (4), when controlling all covariates and two-way fixed effects, OLS suggests that the adoption of a petition involving administrative actions can increase the realization probability by 59%. Notably, all results in the second row retain similar coefficients across all models and are all significant at the 1% level. This correlation between petition adoption and administrative implementation indicates that legislative and administrative bodies have collaborated to address their citizenry's concerns through the petition process, despite the dual representation and formal power imbalances inherent in the prefectural government.

For a petition that requests only non-binding resolutions, we would obtain the same intuition as those of administrative actions, but with an even higher magnitude. For example, in Model (1) with only two-way fixed effects, the probability that the petition will be realized increases to 62.1%, and the result is statistically significant at the 1% level. In summary, it is highly probable that resolutions will be transmitted to the National Diet or ministries once petitions calling for the resolutions have been adopted.

Note that the estimation result coincides with the two hypotheses presented in section 3.2.: The adoption of a petition is associated with its realization, and the results are consistent irrespective of model specification and petition types. We could also obtain the following result: relative to petitions that ask for administrative actions, the adoption of petitions that ask for a non-binding resolution is strongly correlated with their realization.

5.1. Robustness check

To assess the robustness of our results, we conducted an additional analysis in which the governor's opinion (or ‘stance’) about the petition was controlled. Specifically, if a respondent chose ‘Completely disagree’ or ‘Disagree’ to the question ‘What do you think the governor's stance is on this petition?,’ the variable Governor Oppose is 1. In contrast, if the respondent chose ‘Somewhat agree’ or ‘Agree,’ then the variable Governor Support is 1. Both are 0 if ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ was chosen.

Because this variable is highly endogenous to the realization of the petition, it must be interpreted carefully. When a governor does not hold a firm opinion about the subject matter of a petition, petitioners can gauge the governor's position based on the outcome of the administrative implementation. For instance, petitioners can conclude that a governor is opposed to their petitions if the executive official does not manage their requests satisfactorily. Despite the limitations of ex-post evaluations, we incorporated a new covariate, Stance of the Governor, into our model and regressed the main equation as we did in Table 2.

Table 3 presents the results with variables of the governor's position. The findings demonstrate that an agenda supported by the governor has a greater probability of being realized than an agenda opposed by the governor. When the governor's stance is included, the statistical significance of the correlation between the petition's adoption and its realization is reduced. However, these correlations remain statistically significant only at the 5% level. The estimation results in Table 3 suggest that adoption of a petition is correlated with an increased likelihood (a 20 percentage point increase on average) that the petition will be realized.

Table 3. Regression analysis with variables of the governor's stance on the petition.

The standard errors are in parentheses. *** P < 0.01; ** P < 0.05; * P < 0.10; The OLS standard errors are heteroscedasticity-robust.

6. Conclusion

Although the petition system is widely regarded as a ‘parliamentary black hole’ (Hough, Reference Hough2012: 480), our results, which focus on Japanese prefectures, identify a significant correlation between the adoption of petitions and their subsequent implementation. Notably, petitions requiring administrative action and those that seek legislative resolutions exhibit a correlation between adoption and subsequent implementation. This trend persists even after controlling for covariates such as whether a member of the governor's party sponsored the petition, what political activities petitioners engaged in, and regional and time-fixed effects.

These findings suggest that individuals and groups exercising their constitutional rights can affect policy through the petition process. The procedural components of petition adoption foster accountability among executive officials, and this increases the likelihood that petitions will be implemented, which, in turn, improves democratic responsiveness in Japanese local politics. The petition process is a platform for residents, assembly members, and executive branches to share broad policy goals and demonstrate their commitment.

Our study has three limitations. First, our dependent variable, the degree of realization, is intended to minimize errors that arise from respondents' different interpretations of each option, and to this end, we provide illustrative examples. However, this variable may reflect some subjectivity influenced by petitioners' evaluations. Second, because of methodological constraints, we could not assess the reliability of our survey results against alternative methods of measuring implementation. Third, while our model included several covariates, the issue of causal inference remains unresolved.

Future research should examine in greater detail the causal relationship between the disclosure of petition-related information and increased administrative accountability for policy implementation. Additionally, it would be useful to study the dynamics of policy effectiveness in countries that, to achieve procedural transparency, have reformed their petition systems; this, too, would lead to a greater understanding of the underlying mechanism.

Lastly, we discuss what our findings imply about the right to petition in Japan. The scholarly interpretation of this right has evolved from emphasizing nondiscriminatory access (jueki-ken) to advocating political participation and the expectation that petitions will be addressed through good faith practices (sanseiken-teki-kenri) (Ichikawa, Reference Ichikawa1997; Hayashi, Reference Hayashi2019). The latter have broadened the scope of the right to petition and established it as a fundamental norm that guarantees dedicated legislative deliberations and a faithful reporting of progress (Hayashi, Reference Hayashi2019: 32). In the context of the ongoing reinterpretation of the right to petition, our analysis provides empirical evidence of the extent to which normative arguments in constitutional theories operate in practical political settings, particularly as these concern legislatively backed petitions.

Funding statement

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 19J22864.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The details of our survey process and content were approved by the internal ethics committee of the University of Tokyo. Ethical Review Committee for Experimental Research involving Human Subjects (Project no. 773: Approved 18 August 2021).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HJIDDC (URL: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/HJIDDC)

Appendix

A. Further robustness checks

Operationalizing the degree of realization when the reliability of the variable is assessed is a challenge. Regarding the Adopt variable, we can verify the reliability of the responses by cross-referencing them with parliamentary documents. Examining the adoption results for each petition, we found nine responses that exhibited discrepancies.Footnote 18 Subsequently, we repeated the same analysis after excluding the nine observations. Table A1 presents the estimation results. Compared to Table 2, the coefficients exhibit greater values. However, they retain general significance at the 1% level and a pattern of lower coefficients for administrative action petitions than for non-binding resolutions.

Table A1. Regression analysis after excluding observations with discrepancy

B. Sampling the survey and potential bias

Within the scope of our research, there are a total of 684 petitions (excluding duplicates) that were submitted to Japanese prefectural assemblies.Footnote 19 605 petitions had a known petitioner address, and surveys were mailed to these addresses. The petitioners for the remaining 79 petitions did not receive a survey because their prefectures declined to reveal petitioners' addresses, citing personal information concerns. 228 petitioners responded to our survey.

Given, first, that not all petitions were included in our questionnaire and, second, our modest response rate, we investigated potential bias in three different levels of observed data: (1) all petitions (684); (2) the sampled population (605); and (3) all respondents (228). We examined systematic bias in our data because some assemblies and assembly secretariats might be inclined to release information about adopted and resolved petitions but withhold information about unresolved or rejected petitions for fear that the latter could lead to a citizen backlash. Moreover, it is plausible that citizens content with the legislative outcomes of their petitions might respond more frequently to our surveys than those dissatisfied because their petitions were rejected.

To investigate potential bias in our data, we determined whether petitioner information was more likely to be disclosed in the case of petitions adopted by assemblies and whether in the same group, the rate of survey responses was higher. Adoption rates in our data across all samples indicate no apparent systematic bias in the petition adoption results in the three levels of observed data. As one can see from Table B1, there were 684 petitions submitted during the period under our investigation, and 35.09% of them were found adopted. Among the 605 petitions surveyed, the adoption rate was 33.20% when petitioners with unspecified information were excluded. Among respondents, the rate was 34.21%, according to their reports.

Table B1. Adoption rate across three stages