Is not the system of private property in land chargeable with murder?

How does a scholar of British Romanticism end up writing a book about Black Caribbean geographies? The project began by exploring how Romantic-era working-class class writers, such as William Cobbett and John Clare, were writing against the enclosure of the commons by imagining new ways to develop commons in Great Britain. Places where ordinary people farmed and lived communally, commons have been described by Peter Linebaugh, whose materialist approach to the topic emphasizes that commons were created “through labor with other resources; it does not make a division between ‘labor’ and ‘natural resources.’”1 Inspired by his ecological reading of the commons, I initially decided to add a chapter on the critically neglected Black British writer Robert Wedderburn. Accustomed to grappling with working-class periodicals, particularly Cobbett’s Register, my attention was drawn to a line in the last issue of Wedderburn’s Axe Laid to the Root, in which he prophesied a growing movement toward abolition in Kingston, Jamaica: “The free Mulattoes are reading Cobbett’s Register, and talking about St. Domingo” (6.90).2 Wedderburn’s vision of a transatlantic alliance between Cobbett’s agrarian radicalism and West Indian slave revolts gestured toward a global, transracial solidarity absent from Cobbett’s politics. Moreover, since Wedderburn’s imagined transatlantic collaboration was a performance for his primarily white, working-class audience in London, Wedderburn was – beyond aligning interests – championing Black, West-Indian resistance against slavery as a model for his white audience. In the turbulent and repressive era of the 1810s, just before the Peterloo Massacre, Wedderburn imagined new ways of creating commons, like William Cobbett and John Clare. Yet Wedderburn’s commons were based quite differently on long-established African-Jamaican land use and food sovereignty practices. To explore Wedderburn’s vision fully, I put aside the first project. Robert Wedderburn, Abolition, and the Commons follows the political thought of Robert Wedderburn, whose advocacy for Black, place-based opposition to slavery provides an innovative lens for reading Romantic-era political prose, slave narratives, and travel writing.

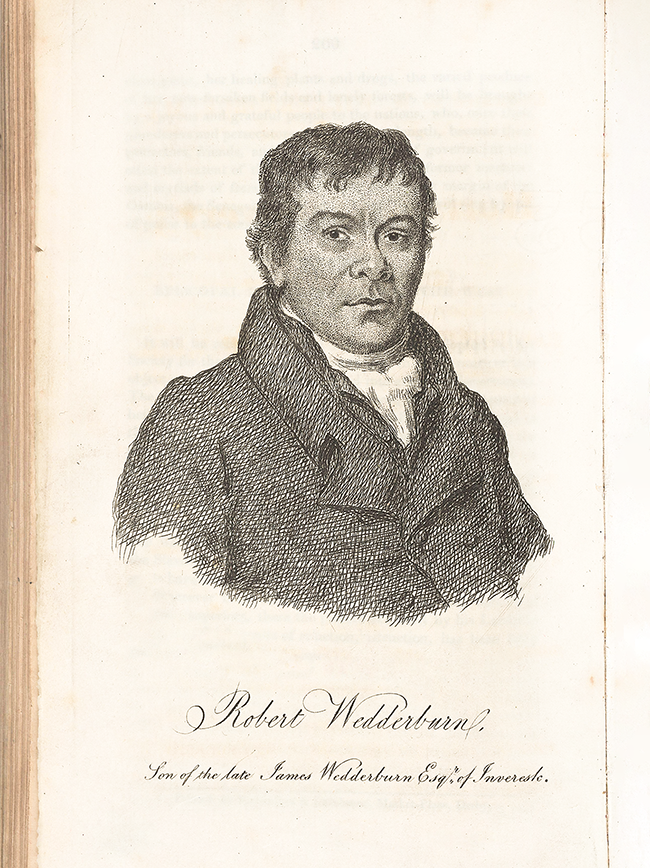

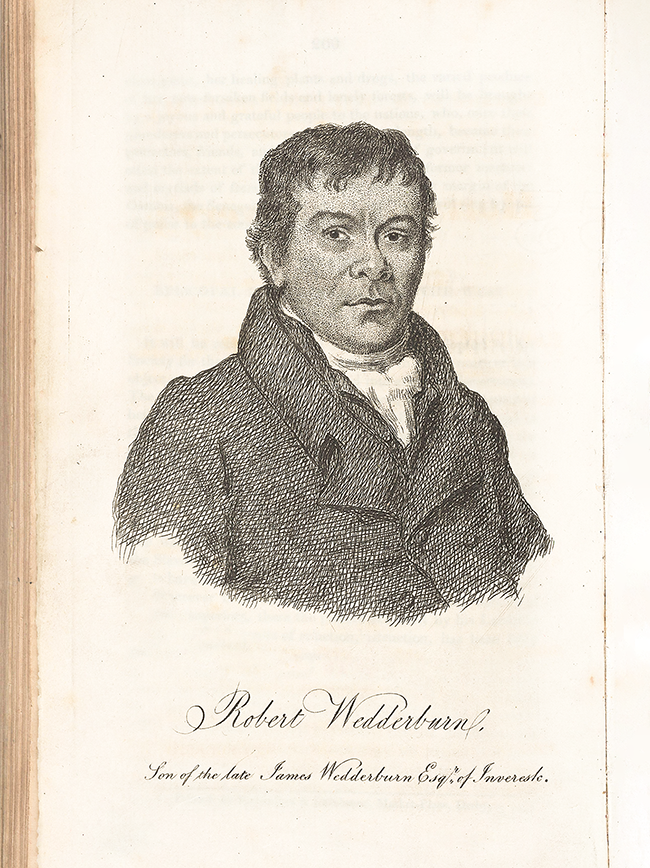

Robert Wedderburn was born in 1762, and his mother, Rosanna, was his father’s enslaved house manager (Figure I.1). His father, the Scots planter James Wedderburn, owned several large sugar plantations in the Westmoreland parish of Jamaica. When Rosanna was pregnant with Robert, James Wedderburn sold her to another enslaver. Throughout the rest of his life, he refused to acknowledge or support Robert, except to manumit him and his brother James for £200.3 Although he was not enslaved, Wedderburn was raised by his enslaved mother and grandmother. He further witnessed the violence of slavery as he matured into adulthood as a jobbing millwright who traveled to many parts of Jamaica. Wedderburn joined the Royal Navy at age sixteen and migrated to London, where he united with other African, Irish, and lower-class English people in London’s ultra-radical networks. In 1817, he became the de facto leader of the Spencean Philanthropists, a group dedicated to achieving social equality by ending private property in land, after the former leader was jailed for his political activities under the suspension of habeas corpus.4 Wedderburn’s significant publications were written after this moment: his working-class periodical of 1817, Axe Laid to the Root, and his 1824 life narrative, The Horrors of Slavery.

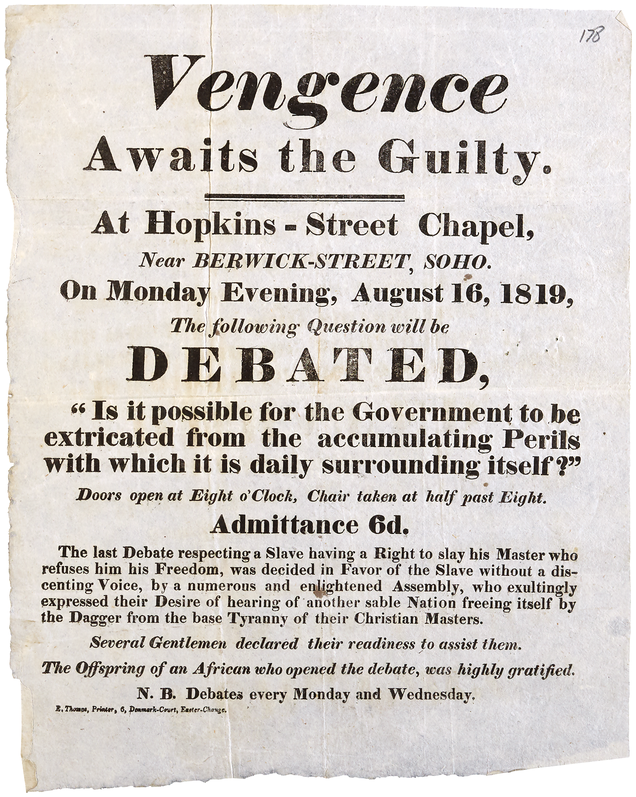

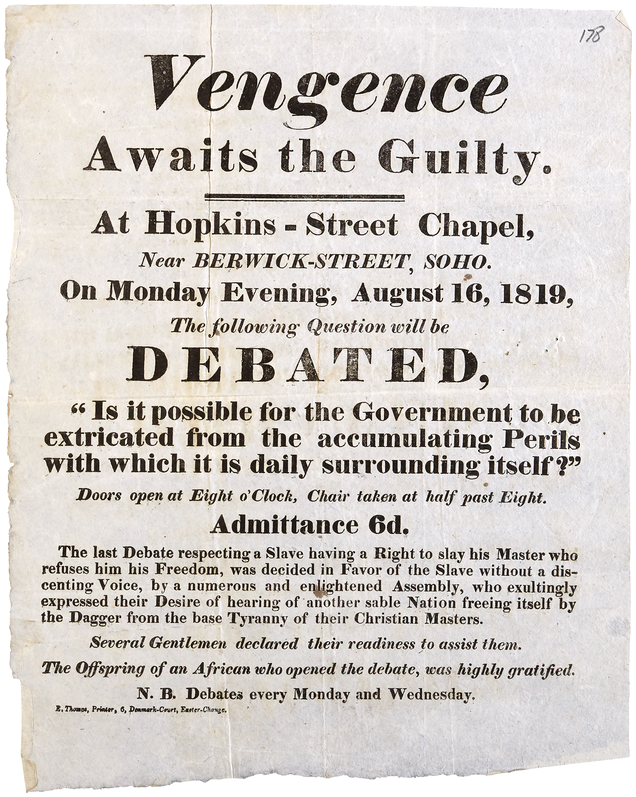

As a leader of the Spencean Philanthropists, Wedderburn became well known for his preaching and public debates at his Hopkins Street Chapel in Soho, London.5 In many ways, Wedderburn’s debates followed ultra-radical traditions. As Iain McCalman points out, “the Spenceans’ preference for the tavern debating club as a radical organisation and strategy linked them with long-established popular traditions.”6 Wedderburn’s topics for debate, however, were anything but traditional. For example, his topic “Can It Be Murder to Kill a Tyrant?” and “Has a Slave an Inherent Right to Slay His Master, Who Refuses Him His Liberty?” evoked slave rebellion as an ethical model of liberation for his white audience (Figure I.2). In an intellectual milieu when proslavery writers resisted the end of slavery, and antislavery activists desired an “emancipation from above” that was administered and controlled by British colonial and commercial interests, Wedderburn’s championing of abolition from below through slave revolt marked a startling departure from mainstream politics.

Figure I.2 Handbill advertising a debate on August 9, 1819, “Can It Be Murder to Kill a Tyrant?”

Wedderburn’s debate about slave revolts occurred at a significant moment, just one week before the Peterloo Massacre. Like Henry Hunt and other working-class activists, Wedderburn escalated his rhetoric precisely then, establishing his participation in this quasi-revolutionary cusp in British working-class history. A handbill for Wedderburn’s next debate, scheduled on the same day as the Peterloo massacre, August 16, 1819, reported that at the previous week’s debate, the assembly gathered at his Hopkins Street Chapel decided in favor of slave revolt (Figure I.3). Wedderburn’s summary of the debate alluded to the Haitian Revolution, boasting that the assembly of working-class men “expressed their Desire of hearing of another sable Nation freeing itself by the Dagger from the base Tyranny of their Christian masters.” By calling for another Haitian Revolution, this time in the British West Indies, Wedderburn expressed moral outrage against the British system at home and slavery in the colonies while proposing a different, distinctly African-Caribbean version of a more just society.7 A government spy report written on August 10, 1819, recorded the debate and suggested Wedderburn was a threat to the British government: “After noticing the Insurrections of the Slaves in some of the West India Islands he said they fought in some instances for twenty years for ‘Liberty’ – and he then appealed to Britons who boasted such superior feeling and principles, whether they were ready to fight now for but a short time for their Liberties.”8 Inflammatory spy reports led to Wedderburn’s arrest; he was jailed for sedition during the Peterloo Massacre. After his release on bail, Wedderburn “did not flinch,” as McCalman aptly puts it, and he continued the debates.9 However, within months, he was arrested again.

Although the jury recommended mercy, Wedderburn was given a two-year sentence for blasphemous libel in 1820. At his sentencing, the solicitor general declared, “the defendant is a most dangerous character, because he certainly possesses considerable talents, and those too of a popular nature, and calculated to do much mischief amongst the class of people to whom he was in the habit of addressing himself.”10 The idea that Wedderburn was dangerous precisely because he was too talented and popular indicates that when he published his abolitionist life narrative, The Horrors of Slavery, in 1824, he had a significant following. He continued to depart from mainstream politics by publishing his life narrative as an inexpensive pamphlet within ultra-radical circles, thereby avoiding the demand to edit his narrative to suit the political ambitions of white abolitionists. Other Romantic-era slave narratives, such as Olaudah Equiano’s The Interesting Narrative (1789) and The History of Mary Prince (1831), were, to varying degrees, prompted, edited, and published by antislavery activists in England. Untethered by political demands for middle-class respectability and patriotism, Wedderburn introduced himself on the title page of Horrors of Slavery as “Late a Prisoner in His Majesty’s Gaol”: a representation of his life, reiterated in the narrative, that radically tracked the horrors of racialized slavery on a West Indian plantation to incarceration in an English prison. Horrors of Slavery also celebrated the rebellious practices of his enslaved mother, Rosanna, and his grandmother, Talkee Amy, as the sources of his emancipation from slavery rather than his residence on English soil.

While Romantic-era readers and government spies were alert to his presence, Wedderburn figures only marginally in contemporary Romanticist criticism. Wedderburn’s work may have been neglected, in part, because of intractable questions about his authorship. In this book, Wedderburn’s political theory will be discerned chiefly through his publications Axe Laid to the Root and Horrors of Slavery. However, there are other pamphlets and articles associated with his name. His first pamphlet, an antinomian political commentary, Truth Self-Supported (ca. 1802), was likely dictated to his publishers due to his illiteracy at the time.11 Even if Truth Self-Supported was heavily edited and transcribed, Wedderburn returned to similar antinomian and anticlerical themes in the 1820s. Most scholars agree that he wrote the short satire “The Holy Liturgy,” published in Richard Carlile’s The Lion (1828). An anti-clerical satire published under his name, Cast-Iron Parsons (1820), however, was likely ghostwritten by the freethinker and pornographer George Cannon, alias Erasmus Perkins. Wedderburn’s “radical patron” and collaborator, Cannon also wrote and then published Wedderburn’s defense for his trial for blasphemy in 1820.12 Unfortunately, Cannon’s “defense” was so defiant as to ensure Wedderburn’s imprisonment. Ryan Hanely notes, “historians have tended to represent the relationship between the two men as more mutually beneficial than was actually the case.”13 Moreover, questions about whether Cannon merely transcribed and polished or completely invented Wedderburn’s defense remain. These questions are additionally complicated by the collaborative nature of ultra-radical print culture, which, Eric Pencek argues, emerged “in opposition to the underlying assumptions that go with individual authorship.”14 Wedderburn’s embrace of collaborative authorship in opposition to private property challenges scholarship about his work.

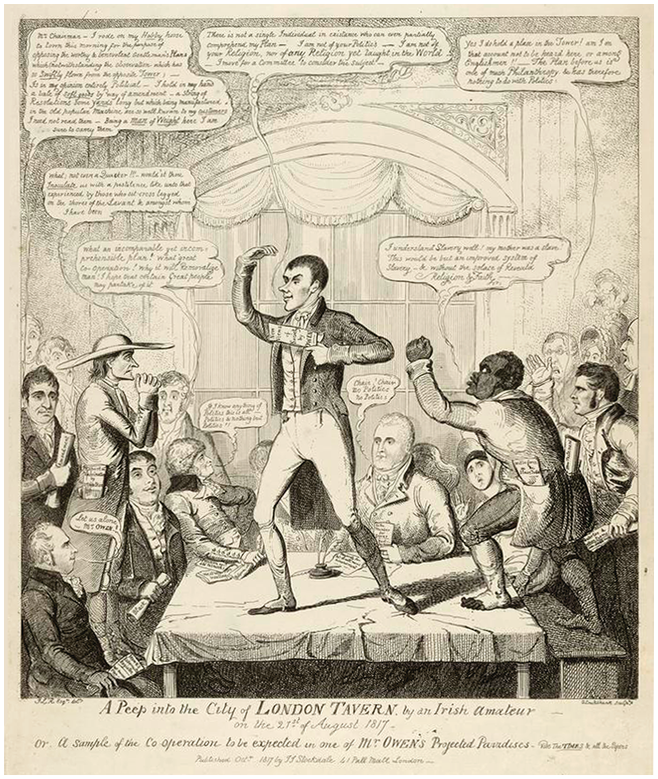

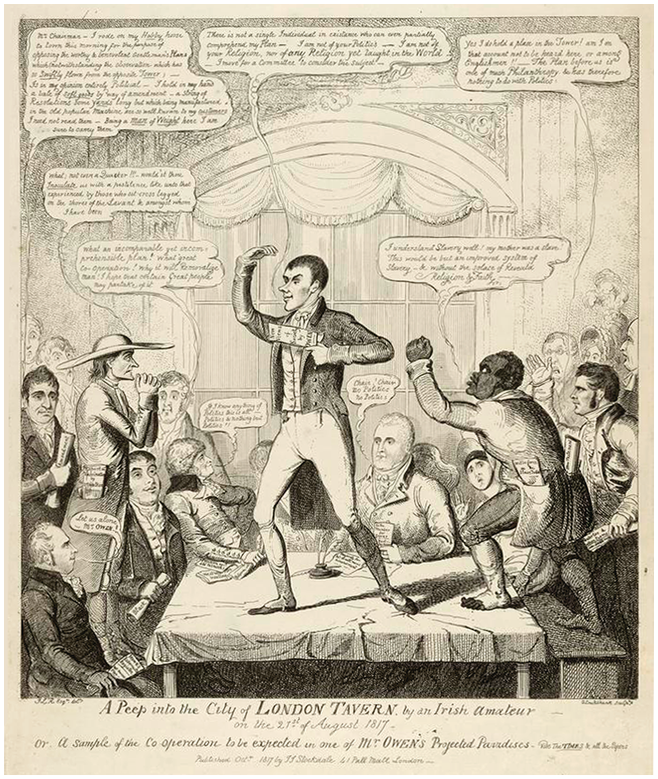

Although uncertainty about the individual authorship of some texts within Wedderburn’s oeuvre should be acknowledged, it should not be a barrier to analyzing the primary textual artifacts associated with him. As literary analysis instead of biography, this book does not detail every facet of Wedderburn’s long, complicated, communal life and publications. Robert Wedderburn, Abolition, and the Commons limits its focus to Wedderburn’s political contributions to Romantic print culture in the turbulent years before and after the Peterloo Massacre, Axe Laid to the Root (1817) and Horrors of Slavery (1824). Scholars agree that Wedderburn authored these texts because their content aligns with the Home Office’s documentation of his speeches.15 The government spy reports on his speeches verify the content and influence of Wedderburn’s political activism, yet they are part of a repressive discourse intended to criminalize his politics. This book minimizes reliance on them. Another marker of Wedderburn’s prominence during the years in which he wrote Axe Laid to the Root and Horrors of Slavery can be found in two caricatures by one of the Romantic period’s “undisputed masters” of caricature, George Cruikshank.16 A Peep into the City of London Tavern (1817) featured Wedderburn prominently alongside well-known radicals, and The New Union Club (1819) represented Wedderburn in alliance with abolitionists William Wilberforce and Zachary Macaulay. Both caricatures expressed anxiety about the extent and influence of Wedderburn’s distinctively Black perspective on radicalism and abolition.

A Peep in the London Tavern (1817) was intended to mock the working-class movement toward “cooperation” by emphasizing significant differences in radical thought (Figure I.4). At the center of the caricature, the utopian proto-socialist Robert Owen stands on a table holding a copy of his A New View of Society (1813–16). A crowd has gathered to hear Owen speak, and several audience members, including the well-known radicals William Hone, Major John Cartwright, and Thomas Wooler, can be identified through their word bubbles. Wedderburn alone has risen above the other radicals by standing and stepping onto the table from which Owen speaks. Wedderburn contends, “I understand Slavery well! my mother was a slave. This would be but an improved system of Slavery – & without the solace of Revealed Religion & Faith.”17 Wedderburn must have been so well known that his biographical background would identify him to Cruikshank’s audience even beyond London’s radical circles.

Although Cruikshank would hardly have been sympathetic to Wedderburn’s views, the word bubble correctly noted that Wedderburn’s political thought emerged from his observation of enslaved Black women’s strategic resistance to slavery. Wedderburn critiqued Owen’s plan as “an improved system of Slavery,” which astutely pointed out that Owen’s moral concerns were limited to British workers in cotton mills while eliding the industry’s dependence on American slavery for cotton. Cruikshank’s summary of Wedderburn’s critique uncannily anticipates Michael Morris’s argument that Owen’s improvements for textile workers were “a node in the global history of cotton” that illustrated British “improvement” at home depended on transatlantic slavery.18 Wedderburn’s publications demonstrate that he was indeed part of the political discussion about Owen’s New View. His Forlorn Hope, a co-produced cheap weekly periodical published the same month as this caricature, accused Owen of being a “tool of the landholders” who hid the government’s “inability to redress” the condition of the lower classes. Insisting that English workers must do more than cooperate to negotiate better pay, Wedderburn argued, “private property in land has been the cause of all the blood which has been shed in the last fifty years.”19 In other words, private property was the root of oppression, and liberation could be won only through land reparations that restored the commons and common rights throughout the British Empire, in Great Britain, Ireland, and, crucially, the West Indies.20

Like others in the crowd, Wedderburn can be further identified through the texts he carried with him, the Bible and William Wilberforce’s antislavery writings. Wedderburn’s status as a Black abolitionist was highlighted to distinguish him as a suspicious outsider to working-class politics whose ideas of transatlantic emancipation fit uneasily, if at all, with other working-class radicals. Although Cruikshank accurately depicted how Wedderburn’s political thought emerged, quite proudly, from his identity as the child of an enslaved woman and his lived experiences as a Black man in Jamaica, Wedderburn was an emancipationist who focused on land reparations instead of legal rights. He disagreed with Wilberforce’s paternalist plan for a gradual transition from slavery to wage labor because it was designed to leave the colonial plantation economy intact. The idea that Wedderburn had Wilberforce “in his pocket” to back up his beliefs effectively denies Wedderburn’s status as an original political theorist, and, moreover, reiterates a persistent misunderstanding of abolition that conflates the work of most antislavery activists with the position of William Wilberforce.21 Cruikshank’s racialized caricature of Wedderburn’s physical features and behavior represent him as out of place and even menacing. Wedderburn waves his fist angrily while encroaching on Owen’s space by stepping off his bench and placing his foot on the table. McCalman argues that his shoeless foot with bare toes sticking through the worn-out sock is meant to juxtapose Wedderburn’s “ragged” appearance with Owen’s neat dress.22 Cruikshank minimizes Wedderburn’s significant intellectual challenge to both English radicalism and abolition by depicting Wedderburn’s disagreement with Owen as ill-mannered and physically aggressive. However, Wedderburn’s foot on the table next to Owen demonstrates that his political ideas were a possible, even formidable, challenger to Owen’s plans for reform.

Robert Wedderburn, Abolition, and the Commons endeavors to place Wedderburn’s political thought at the center of that table instead of on the shoeless, tattered margins. By pulling Wilberforce “out of his pocket,” Wedderburn’s theories of abolition are revealed as a critique, not a celebration, of European concepts of freedom. For example, in Axe Laid to the Root, Wedderburn published a fictionalized open letter to Miss Campbell, a Jamaican Maroon, that argued, “yes, the English, in the days of Cromwell, while they were asserting the rights of man at home, were destroying your ancestors then fighting for their liberty” (4.54). Wedderburn challenged his white audience by asserting that the “rights of man” were accomplished while actively “destroying” the liberties of the Jamaican Maroons (and other colonized peoples, for he wrote about Cromwell’s devastation of the Irish as well). Wedderburn confronts his readers with the dark underside of Romanticism’s rights and radicalism, founded alongside and even because of Europe’s imperialist land grabs and plantation slavery.

Moreover, by drawing on history as far back as the establishment of Jamaica as a British colony in 1655, Wedderburn emphasized that the expansion of the British empire also forced Black people in Jamaica to develop other forms of freedom in autonomous Maroon communities, where abolition and decolonization were already underway. Wedderburn centered Black histories and subjectivity while writing about British history and politics. Bakary Diaby recommends examining Black Romantic subjectivity because it would provide a model of revolution that “entail[s] having a revolutionary fragility forged by the oppressive weight of repressive power, a fragility in stark contrast to the reactive one that wields such power.”23 Many of the histories elaborated in Wedderburn’s writing, such as the flight of the Jamaican Maroons or his enslaved mother’s liberation tactics, drew upon and advocated for the efficacy of such “revolutionary fragility.”

Robert Wedderburn, Abolition, and the Commons is indebted to the work of Manu Samriti Chander, who argues, “perhaps paradoxically, we need to cede Romanticism to its unacknowledged participants, those whose challenges to the field will also define it.”24 This book follows the political thought and activism of one unacknowledged participant, Robert Wedderburn, who proposed a model of freedom that profoundly reverses the white abolitionist belief that European models of liberty will eventually spread to the Caribbean. Wedderburn instead highlights Black Jamaican practices of freedom in collective slave revolt, Maroon villages, and traditional subsistence agriculture. Using Wedderburn’s oeuvre as a “challenge to the field” of Romanticism, as Chander suggests, this book then rereads more familiar Romantic-era texts in light of the Black abolitionist geographies that Wedderburn introduced to his London audiences.25 For example, Wedderburn’s ideas about land-based freedom expose dramatic struggles over the provision grounds of enslaved laborers in Matthew Lewis’s Journal of a West India Proprietor. Wedderburn’s vindication of the freedom practices of his enslaved mother and grandmother in Horrors of Slavery, when read alongside The History of Mary Prince, prompts a reassessment of the influential tactics of Black women’s activism in the abolition of slavery. Although Cruikshank represented Wedderburn’s politics as a hostile outlier to even the most radical thought, this book invites Wedderburn’s ideas into the political and textual histories of the Romantic period.

Wedderburn, Romanticism, and Black Studies

My reading of Wedderburn’s life and writing is indebted to two distinct groups of scholars: scholars of Romantic-era working-class writers and scholars working in Black Atlantic studies. Malcolm Chase notes that Wedderburn participated in working-class agrarian movements toward a “People’s Farm,” which advocated for the restoration of the commons and a radical redistribution of land in England.26 Iain McCalman’s extensive archival research on Wedderburn’s role in English radicalism is documented in Radical Underworld and his book-length collection of excerpts from Wedderburn’s writing, Horrors of Slavery and Other Writings, by Robert Wedderburn. More than any other scholar, he laid the groundwork for understanding Wedderburn’s influence in early nineteenth-century London. About Axe Laid to the Root, McCalman writes, “the periodical’s most important contribution to popular radical ideology came from its sustained attempt to integrate the prospect of slave revolution from the West Indies with that of working-class revolution in England.”27 In addition to being a writer, Wedderburn was a famous orator who staged public debates. Michael Scrivener argues that Wedderburn’s writing and oratory were both uniquely dialogic. Instead of using a singular voice, his thought was articulated through “a vivid performance of different roles.”28 David Worrall likewise emphasizes Wedderburn’s oral debates. He asserts that “the forum in which Robert Wedderburn most vociferously developed his anticolonialist and revolutionary polemic was in a ruined loft in Soho’s Hopkins Street.”29 This body of ground-breaking scholarship on Romantic-era working-class politics sought to include Wedderburn in the network of early nineteenth-century ultra-radicalism and print culture, so it tends to interpret Wedderburn’s political writing as neatly aligning with or even derivative of white ultra-radical activists, such as his friend Thomas Spence.

The second group of scholars who have written about Wedderburn study Black British writers and Caribbean slave narratives. Often, this scholarship focuses on Horrors of Slavery (1824) and Wedderburn’s sense of identity as a formerly enslaved, mixed-race person traversing London. Alan Rice attests to the cultural hybridity of Wedderburn’s “unique and splendidly polyglot transatlantic dialect.”30 Helen Thomas suggests that by foregrounding his mixed-race identity, Wedderburn’s “work exceeded and, in a sense, exacerbated, the parameters of spiritual discourse contained within earlier slave narratives.”31 Also noting his spiritual, prophetic style, Sue Thomas highlights Wedderburn’s lively mixture “of both life writing and jeremiad,” which sets a different tone from other West Indian slave narratives, particularly Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative.32 More recently, Michael Morris reads Wedderburn within the context of his Scottish father, James Wedderburn. The elder Wedderburn fled Great Britain to make new fortunes in Jamaica following the execution of his father after the Battle at Culloden in 1746.33 Ryan Hanley situates Wedderburn within the publishing history of other Black British writers from the Romantic era, such as Equiano and Quobna Ottobah Cugoano, arguing that “unlike earlier black writers, Wedderburn never courted the approval of, or support from, ‘respectable’ authority figures, either within or peripheral to his own networks.”34

While indebted to scholarship that situates Wedderburn either within working-class or Black Atlantic histories, this book is invested in bringing these strands of scholarship together to treat Wedderburn as a political theorist who brought distinctly African-Caribbean knowledge to his lower-class audiences in London. Wedderburn innovatively incorporated his life narrative into the realm of British working-class politics. Like me, Raphael Hoermann marvels that more work has not been done to take Wedderburn’s political thought seriously. He conjectures that Wedderburn’s “constant deliberate slippage between race and class and his call for violent transatlantic revolution might have contributed to his silencing.”35 For example, in Manisha Sinha’s exhaustive transatlantic history of abolition, Wedderburn’s work is discussed in only two paragraphs. Although Sinha laments that his work “has been ignored by historians of abolition,” she only briefly acknowledges that his work provides “a blueprint for a postemancipation utopian black polity” without further explanation.36 This book seeks to unravel and explain the troubling liminal dimensions of Wedderburn’s utopian Black polity.

As a Black man who was formerly enslaved and as an impoverished working-class London radical who experienced persecution under British law, Wedderburn’s writing appears to slip problematically between “wage slavery” and West Indian slavery. By celebrating the place-based freedom practices of enslaved people as worthy of emulation, Wedderburn, at first, appears to resonate with proslavery writers who sought to justify slavery as humane, or alternately, with working-class writers who claimed enslaved people in the West Indies had better living conditions than English workers. Elizabeth Bohls’ argument that “the politics of slavery … played out to a significant degree as a politics of place” helps to explain why Wedderburn’s politics did not resemble British abolitionist views.37 Bohls notes that Romantic-era colonial histories and proslavery texts employed the landscape aesthetics of the picturesque to obfuscate the brutal reality of slavery in the West Indies. On the other hand, British abolitionists acknowledged slavery’s brutality, but they also carefully contained that brutality within the geographic boundaries of the West Indies to reassure readers that freedom and opportunity reigned for all in England. In other words, antislavery activists imagined freedom as a transplant: British liberal freedoms, which resided in England, would be planted in the West Indies and extended to enslaved people. Wedderburn jettisoned the geographic paradigms of both antislavery and proslavery writers by insisting that Black place-based freedom practices in the West Indies were superior to British individualist freedoms.

Deciphering Wedderburn’s celebration of Black geographies, in which land-based West Indian insurrection was an essential touchstone, requires a turn toward scholarship in Caribbean and Black studies. Wedderburn’s lived experiences with enslaved people in Jamaica taught him about resistance to the emergent plantation economy. C. L. R. James argues,

wherever the sugar plantation and slavery existed, they imposed a pattern. It is an original pattern, not European, not African, not a part of the American main, not native in any conceivable sense of that word, but West Indian, sui generis, with no parallel anywhere else.38

On his father’s sugar plantations and then on the docks of Kingston, Wedderburn negotiated and observed the frontiers of the Caribbean plantation economy. To be economically viable, sugar production required large monoculture farms. Eric Williams notes that the rise of sugar plantations was responsible for “changing flourishing commonwealths of small farmers into vast sugar factories owned by a camarilla of absentee capitalist magnates and worked by a mass of alien proletarians.”39 While the movement to large-scale agriculture was taking place across the British empire, West Indian plantations were distinctive because, Sidney Mintz explains, “so much of the industrial processing of the cane was also carried out on the plantations.”40 In addition to his experiences on sugar plantations, Wedderburn explains that in his early work as a jobbing millwright, he was able to travel through many parts of Jamaica:

Though only a lad, I was yet capable of making observations on passing occurrences; being reared in Kingston, and having also lived eighteen months in Spanish town, and the like period in Port Royal; possessing an inclination to rove, gave me a still better opportunity to observe the manners and customs of that country.41

From Jamaica’s port cities to rural plantations, Wedderburn’s experiences with agro-industrialist plantation slavery provided highly sophisticated insights into the workings of Great Britain’s economy that were unavailable to most London radicals. If the large commodity plantation is a land-based form of control that reorganized environmental and social relationships, the African-Jamaican place-based freedoms championed by Wedderburn, on the provision grounds of enslaved people and in Maroon villages, offered a radically different, decolonial foundation for radical politics.

Wedderburn insisted that abolition must be grounded in land and food sovereignty, and not just the law. His view resonates with Sylvia Wynter’s distinction between narratives of the plantation versus those of the provision grounds. Provision grounds were plots of land given to enslaved people in the Caribbean to grow their own food. Outside of the plantation’s gaze and near mountains unsuitable for growing commodity crops, the provision grounds were located outside of the view and control of plantation overseers. As enslaved and formerly enslaved people cultivated common culture and traditional knowledge on the provision grounds, they developed distinct Black geographies that countered the dehumanizing experiences of plantation slavery. Wynter explains:

For African peasants transplanted to the plot all the structure of values that had been created by traditional societies of Africa, the land remained the Earth – and the Earth was a goddess; man used the land to feed himself; and to offer first fruits to the Earth; his funeral was the mystical reunion with the earth. Because of this traditional concept the social order remained primary. Around the growing of yam, of food for survival, he created on the plot a folk culture – the basis of a social order – in three hundred years.42

In Wynter’s view, the provision grounds were sites of hybrid creole culture that remained tied to West Indian land and African traditions. Rarely pictured on planters’ maps, these Black geographies became, Wynter argues, “a source of cultural guerilla resistance to the plantation system.”43 Drawing on Wynter, scholars of Black geographies explore how liberation from slavery was “as much about the struggles over physical geographies as it is about consciousness, cultural refusals, and discourse.”44 Fundamentally opposed to the abolition imagined by Wilberforce, in which freedom was a gift that required continued obedience to Britain’s colonial rule, Black geographies were and are, as Katherine McKittrick notes, a “poetics that envisions a decolonial future.”45

The Black geographies championed by Wedderburn, such as those of the provision grounds and Maroon settlements, contested private property by building reparative commons. Alex A. Moulton notes, “these communities and farming plots enabled the (re)constitution of a commons and were sites of repair; spaces where African identities were reformed into New World Black identities.”46 Like Moulton, Wedderburn represented Black geographies in Jamaica as “sites of repair” that inspired his transatlantic political theory: He argued, “the state of society, truly desirable by the enlightened philanthropists, in which the monopoly of the common benefits of nature would be unknown, and every man able to procure his subsistence with a healthy exertion of labour, could have the leisure to cultivate his intellect, and liberty to expand his virtue” (Axe 3.46). In his view, freedom required access to communally held land, which enabled equity in accessing “the common benefits of nature,” healthy homes, food, and leisure. When Wedderburn argued that justice must include “an equal share of the profit of the land and its appurtenances,” he outlined and championed African-Jamaican Black geographies as both literal places and as stories that advocated for restoring land to dispossessed people. The radical nature of “staying put” on the land continues in Jamaica, where, Rachel Goffe argues, the “squatter” is “an ancestor of Black radical traditions that have long run counter to plantation logics of property, surveillance, and disposability.”47

Arguing that freedom was found in actively reclaiming or “squatting” on colonial land rather than appealing to the law, Wedderburn told stories of liberatory Black geographies to his working-class London audience. Like the contemporary abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Wedderburn argued that “freedom is a place.”48 Colonizer maps rarely included Black geographies, but the project of reimagining colonial land was often noted in writing. Judith Madera, for example, proposes that African American literature can be understood as a project of remapping. She claims, “to gain representation in the symbolic structures of white territorialization, black authors had to write over white principles of containment. They had to dismantle dominant organizational codes of place.”49 Robert Wedderburn wrote against the dominant discourse of colonial land grabs and plantation monoculture to suggest that African Caribbean people were already cultivating abolitionist, decolonial futures through communally held land.

Rereading Romanticism’s Planter Picturesque

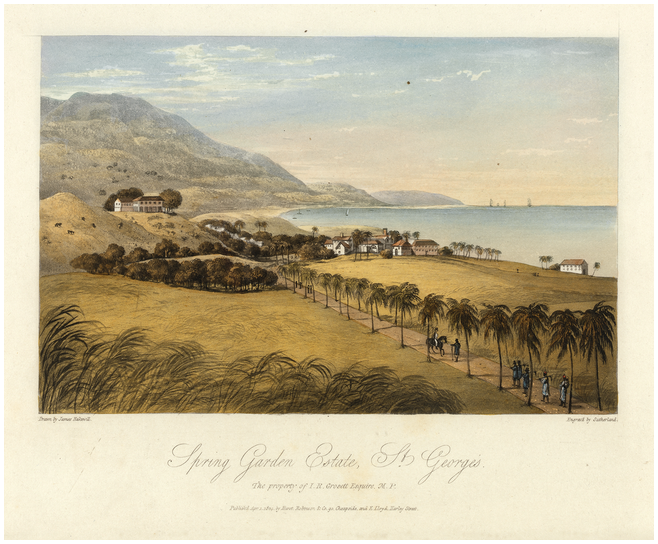

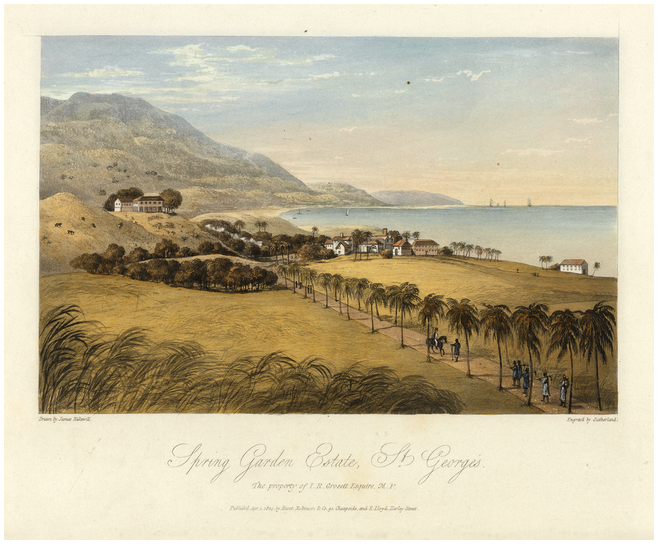

Awareness of the Black abolitionist geographies championed by Wedderburn uncovers new critical readings of Romantic-era natural histories of Jamaica. John Barrell surmises that most Romantic-era representations of landscape were “expressions of an attempt to occupy, so to speak, the place to which they were applied; to appropriate it and to destroy in it what was unknown.”50 Colonial natural histories were additionally compelled to assuage the conscience of the British public by erasing the toil and suffering of enslaved people. The planter picturesque, according to Elizabeth Bohls, “used landscape aesthetics to reimagine the traces of trauma in the form of aesthetic appeal.”51 A notable example of the planter picturesque can be found in James Hakewill’s Picturesque Tour of the Island of Jamaica (1825), a book of “seductively beautiful” illustrations of peaceful, pastoral plantations where human figures are “mere staffage – that is, human decoration – in the best picturesque tradition.”52 Hakewill’s illustration of the Spring Garden Estate in St. George’s parish presents the plantation as a lush environment strictly controlled by orderly straight lines and buildings (Figure I.5). All visible human figures are walking on a straight, narrow paved road that facilitates the export of plantation commodities while maintaining order. The ripe sugar cane to the left side of the engraving wave as if in motion, which, like other images that deploy the planter picturesque, as Evelyn O’Callaghan observes, seeks to “naturalize colonial transplantation, masking the materialist matrix of the plantation economy by imposing an aesthetic screen of picturesque composition.”53 Mountains rise in a blurred distance, the sites of the Black geographies of the provision grounds and Maroon communities that functioned outside of the gaze and logic of the plantation. Nathan K. Hensley argues, “traces of such halfway freedoms exist in the white supremacist archive only as minor notes, blank spaces–in Hakewill’s work, arguably not at all.”54 However, by reading Hakewill alongside Wedderburn, the contours of the minor notes of freedom and resistance become more visible.

The written description accompanying the illustration includes the places and practices of New World Black communities:

This estate contains nearly three thousand acres of land, of which five hundred and eighty are in cane cultivation of plants and ratoons. On it are six hundred negroes; many of them settled on it from father to son, and who regard their houses and provision grounds (of which they have between three and four hundred acres) as an inheritance, the possession of which they enjoy with uninterrupted security. With their surplus produce, and their pigs and poultry, they supply even to the distance of Anotto Bay, and from this traffic derive a very considerable profit.55

Not illustrated because they do not fit into the planter picturesque, Hakewill wrote of aspects of the provision grounds that Wedderburn championed. First, they established kinship, evolving into “family grounds” that were communally possessed and utilized. Material representations of kinship undermined slavery because, as Orlando Patterson proposes, slavery’s “natal alienation” severed “all formal, legally enforceable ties of ‘blood,’ and from any attachment to groups or localities other than those chosen for him by the master.”56 Second, these grounds were so productive that an internal market thrived in accommodating the surplus. Elizabeth DeLoughrey argues that the provision grounds “supported a vibrant internal market economy in which slaves provided the majority of the region’s subsistence and gained significant amounts of currency, autonomy, and even freedom.”57 Due to the abundant success of the Black ecological project of the provision grounds, Caribbean internal markets became a viable alternative to the capitalist economy. Third, enslaved people accumulated profit from this practice. The idea that enslaved people could rightfully earn property through the provision grounds and internal markets but still be property themselves becomes a repeating, troubling, and glaring contradiction in British writing about slavery in the West Indies.

Undoubtedly, Hakewill and other proslavery writers documented the provision grounds and internal markets as part of a larger argument that West Indian slavery was humane and desirable. Yet simultaneously, the narrative reveals Black geographies that challenge slavery. Planters rarely visited provision grounds, which tended to be located one to ten miles away from the plantation on land unsuitable for commodity crops. In a liminal space outside the plantation and next to the mountains, enslaved people had a margin of freedom. In his introduction to the book, Hakewill expressed anxiety about mountain grounds that had not been fully colonized: He noted that the colony of Jamaica spanned over 2,724,265 acres, yet over 1,914,809 of these acres remained “mountains” that were uncultivated.58 He urged for more enclosure and colonization because, in Great Britain as well as the Caribbean, as Barrell notes, “the enclosure of uncultivated land, with the object of cultivating it, was a way of bringing it into that part of the landscape which because it was cultivated was known, and no longer hostile.”59 Indeed, the potential hostility of the unenclosed Jamaican mountains was used to justify Hakewill’s argument that slavery must continue.

Concerning this geography, Hakewill asked a probing question that would become a crisis after emancipation: “Suppose the negro emancipated, what motive would he have for working?” He directly expressed concern that the geography and climate of Jamaica might facilitate freedom from wage labor for capitalist agriculture:

Unlike the peasant of Europe, who if he do not work must starve, he [the Jamaican laborer] has only to betake himself to the woods, where, if no law gives the power of dislodging him, he will immediately find himself at ease, and look at perfect indifference on all beyond his hut and his plantain ground.60

The provision grounds were a threat not only to plantation slavery but wage-labor plantation futures. In Wedderburn’s oppositional political history, “perfect indifference” to the colonial plantation economy required access to land. Hakewill implied it was merely the tropical climate of Jamaica that allowed Black people to subsist outside of the global food system because the survival of African-Caribbean land-based commons and markets challenged one of European enslavers’ primary assumptions, that Africans were “bereft of farming skills and knowledge, and were given these skills and knowledge by white planters.”61 Both ecologically and culturally, the mountains provided an alternative to the monoculture of the sugar cane plantation. Hakewill’s fears demonstrate why Wedderburn was a champion of the African-Jamaican provision grounds and Maroon communities.

Countering the Romantic picturesque, Wedderburn’s political writing often represented freedom through an abolitionist grotesque, moments in which the produce generated by Black agricultural and ecological knowledge invaded the boundaries of plantations. By putting Wedderburn in dialogue with other Romantic-era texts, this book explores numerous instances where plantations were terrorized, not by scarcity or ineptitude, but by the success of Black geographies. For example, Matthew Lewis documented that the people he enslaved kept innumerable pigs that, when loosed, destroyed his sugar cane as quickly as a fire, and Queen Nanny of the Maroons grew pumpkins almost overnight, reterritorializing British land and nourishing an army of Jamaican Maroons. Jamaica’s prolific pumpkins continued to trouble the British imagination even after abolition, as Thomas Carlyle vividly portrayed in his racist depiction of “Quashee” surrounded by pumpkins, food that provided freedom from the compulsion to work for a wage on British sugar plantations.62 The following chapters explore these and other Romantic-era Black geographies in detail.

Chapter 1 discusses the political ideas outlined in Wedderburn’s Axe Laid to the Root (1817), an inexpensive weekly periodical for working-class readers that Wedderburn wrote and published as he rose to leadership of the Spencean Philanthropists in 1817. Axe Laid to the Root instructed its white, lower-class readers about the radical potential of African-Jamaican land and food-based liberation. The provision grounds, plots set apart from the plantation for enslaved people to grow their own food, were a source of resistance to plantation capitalism, providing food sovereignty and communal identity. The ecological knowledge of the Jamaican Maroons was another source of resistance to plantation economies. Finally, Wedderburn’s writing in “cheap” periodicals aspired to cultivate a transatlantic alliance between the English lower classes, the colonized Irish, and free and enslaved people in Jamaica. The chapter concludes by discussing George Cruikshank’s The New Union Club, which features Wedderburn as a central figure within abolitionist circles. Despite Cruikshank’s intention to dismiss him as a crude entertainer, Wedderburn remained a prominent figure in the caricature, a reminder that Wedderburn’s Axe Laid to the Root supplemented his influential preaching and public debates in London. Wedderburn attempted to persuade his white lower-class audience that Black resistance was a viable political strategy, destabilizing the white abolitionist view that liberation would arise from transporting English freedoms to the colonies and extending them to enslaved people.

Chapter 2 explores how Wedderburn’s view of Black-led abolition was further outlined in his life narrative, The Horrors of Slavery (1824). The narrative initially emerged as a series of letters that Wedderburn wrote to a working-class periodical, Bell’s Life in London, after the editor had questioned whether plantation owners would ever enslave their own mixed-race children. The question prompted Wedderburn to share his life story, in which he represented himself as a “product” of plantation slavery and testified to his father’s sexual and moral depravity as a “slave-dealer.” Although the letters prompted threatening replies from his white half-brother, Andrew Colvile, Wedderburn defiantly republished the Bell’s Life letters as a pamphlet sold by the ultra-radical booksellers Richard Carlile and Thomas Davison. Horrors of Slavery radically tracked his life from the horrors of slavery on a West Indian plantation to his harsh sentence of solitary confinement in an English prison for blasphemous libel. Horrors argued that freedom from slavery was haunted by an unrepaired traumatic past and ongoing prosecution by the British government, making it an essential supplement to more commonly studied Romantic-era slave narratives, such as Equiano’s Interesting Narrative.

Horrors of Slavery also announced an antislavery politics largely unacknowledged by Romantic-era abolitionists: place-based, self-liberation led by Black women. Chapter 3 proposes that Wedderburn significantly reworked the Romantic, abolitionist figure of the sorrowful, enslaved Black mother by celebrating his African-Jamaican mother and grandmother’s communal, place-based resistance to slavery. Wedderburn’s mother, Rosanna, demanded that his enslaver father manumit him. His grandmother, Talkee Amy, was a skilled higgler and obeah woman who, in Wedderburn’s terms, “trafficked on her own account.” Similar freedom practices are then traced throughout The History of Mary Prince (1831). Mary Prince’s repeated petit marronage demanded enslavers’ acknowledgment of her kinship with her parents and husband. As a West Indian higgler, like Talkee Amy, Prince used the produce from the provision grounds of the enslaved to assert freedom in fugitive markets. Instead of representing an individual’s journey from enslavement to British liberal freedom, Wedderburn and Prince’s life narratives do the reverse; they were both Black and British, lived in London, and brought stories of Black women’s place-based freedom practices to a white audience.

Guided by Wedderburn’s argument that land-based freedom must be guarded “above all” for Black self-emancipation, Chapter 4 asserts that tensions over provision grounds permeated Matthew Lewis’s encounters with enslaved people in his Journal of a West India Proprietor (1818, published in 1834). When Matthew Lewis arrived at his Cornwall plantation in Westmoreland, Jamaica, the people on his estate celebrated for two days. Lewis was flattered by the fawning and praise, but the celebration quickly shifted to negotiations for more time at the provision grounds. After granting an additional day per week on the provision grounds as “a matter of right,” Lewis documented that enslaved people were growing poisons, unleashing fires, harboring crowds of destructive livestock, and providing sustenance for self-liberated Black people. Despite noting these dangers, Lewis wrote to William Wilberforce detailing his plan for emancipation by giving enslaved people his plantation as reparations, a proposal he feared to be “dangerous to the island.” Lewis’s Journal recorded that his plantations were undermined, not by overt rebellion, but rather by the success of the Black ecological project: The botanical and animal ecologies of the provision grounds were anticipatory abolitionist commons that would be drawn upon in the coming emancipation.

Black abolitionist geographies were cultivated to their fullest extent in Maroon villages. Chapter 5 moves backward in time to trace the Maroons’ decolonial relationship with the environment, starting with Queen Nanny, a leader in the First Maroon War and a present-day National Hero of Jamaica. Narratives of Nanny’s warfare against the British noted that her fight included growing pumpkins in the rugged Blue Mountains. The chapter then turns to a critically neglected Romantic-era text, R. C. Dallas’s History of the Maroons (1803). Although primarily a military history, Dallas repeatedly admired the Maroons’ communal “superabundance.” Similarly, J. G. Stedman’s Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition (1796), accompanied by William Blake’s illustrations, described Maroon settlements as viable, sustainable societies that were notable alternatives to plantation capitalism. The Maroons’ agricultural and culinary “superabundance,” documented by Dallas, Stedman, and Blake alike, suggests a Romantic-era ecological critique rooted in communal decolonial practices, which supplements the Romantic figure of the solitary walker who critiques society by communing with nature.

Chapter 6 proposes that the provision grounds continued to trouble the Victorian imagination because, as Malcom Ferdinand observes, it was “an abolition of slavery on the condition that the colonial plantation continues.”63 The radical nature of Black-led agriculture emerged vividly after the abolition of slavery in 1834 when newly freed Black people challenged the plantocracy by staying put on their communal provision grounds. For example, letters from the overseer on Lord Holland’s Jamaica estate documented that formerly enslaved people viewed their homes and provision grounds as a commons, so “they cannot think of paying any rent.” Both antislavery and proslavery writers developed strategies for displacing Black Jamaicans from their land. Abolitionist Joseph Sturge, for example, recommended importing provisions from Haiti to weaken Jamaica’s internal markets and make workers dependent on wages. Thomas Carlyle’s notorious “Discourse” (1849) seethed with racist rage focused on “Quashee” surrounded by pumpkins, a synecdoche for independent, agriculturally successful Black people. In Carlyle’s essay, the planter picturesque becomes an abolitionist grotesque of “waste fertility,” an environment of seemingly out-of-control plants and animals swarming around free Black people unwilling to participate in Britain’s wage labor economy. Carlyle’s coinage of “waste fertility” inadvertently illustrated the Black geographies championed by Wedderburn.

The Conclusion reads Wedderburn’s final pamphlet, An Address to the Lord Brougham and Vaux (1831), as a contribution to the early nineteenth-century political “war of representation” about whether Black people in the West Indies would be willing to work for wages after emancipation. Although seeming to reiterate the proslavery claim that enslaved people in the West Indies had better living conditions than European wage laborers, Wedderburn’s vision of dwelling on the land outlined a nuanced, speculative decolonial future. The conclusion finally argues that narratives of the Romantic revolutionary age should include Black abolitionist geographies, a revolution cultivated on common land with pigs, pumpkins, and yams.

Wedderburn’s Black geographies were not spectacular, nor did they have the overt insurrectionist telos of stories that dominate histories of Black self-emancipation, such as Tacky’s War or the Haitian Revolution. David Scott observes that Wedderburn was a “conscript of modernity,” working within limitations that may chafe against scholarly and political desires for revolutionary clarity and heroic action toward the abolition of slavery. Attention to Wedderburn’s place-based, communal freedoms responds to Scott’s call for “a story more attuned to the productive ways in which power has shaped the conditions of possible action, more specifically, shaped the cognitive and institutional conditions in which the New World slave acted.”64 The provision grounds functioned precisely this way: They were shaped by the conditions of power, as the planters allotted them, and then enslaved people created freedom practices within them. Malcom Ferdinand provocatively argues that emancipation erased such Black geographies. He claims, “the vitality present in the breaking of chains and in mad dashes took precedence over the patience of planted yams and paced-out forests.”65 Wedderburn’s writing invites us to reconsider the political importance of the insurgent multispecies communities of planted yams and forest paths forged by Black people in the West Indies under the dehumanizing system of slavery. At the same time, it is paramount to avoid creating an idealized version of these difficult-to-carve-out spaces. Jenny Sharpe warns, “an uncritical celebration of slave resistance and resilience risks overlooking the conditions of subjugation and dehumanization that in many instances prevented an opposition to slavery, overt or otherwise.”66 To avoid overlooking the painful, circumscribed conditions of plantation slavery, this book attempts, as Saidiya Hartman suggests, to “represent the various modes of practice without reducing them to conditions of domination or romanticizing them as pure forms of resistance.”67

With those caveats in mind, this book attempts to recover Wedderburn’s place in politics, challenging redemptive histories of abolition that focus on Wilberforce and other white antislavery activists as heroic figures.68 Wedderburn’s abolitionist geographies found a place in the Romantic era so prominent that he was depicted in caricatures with other well-known radicals, spied upon by the British government, and even jailed for his influence. While his treatment was in keeping with the paranoid repression of the post-Waterloo era, the response to his activism still suggests that scholars should take his work more seriously. Wedderburn’s writing provides a rare glimpse into what Vincent Brown describes as “an oppositional political history taught and learned on Jamaican plantations – a radical pedagogy of the enslaved – shaped the slaves’ goals, strategies, and tactics as they rehearsed bygone battles and considered future possibilities.”69 By centering that oppositional pedagogy, Robert Wedderburn, Abolition, and the Commons attends to stories of Black Caribbean practices of freedom that can productively challenge and stretch Romantic-era narratives about the landscape, the abolition of slavery, and radical politics.