In a letter to the Morning Post in 1864, a Londoner bemoaned the plague of street musicians, especially organ-grinders, and the threat they posed to the peace and quiet of the metropolis. The correspondent was particularly peeved that, despite laws regulating other aspects of the soundscape, street musicians had evaded legal entanglement:1 ‘The trifling nuisances of old times, such as the dustman’s bell (and I believe even the muffin bell), the newsman’s horn, the cry of “sweep”, and many others have been prohibited. Why not forbid street music – or at least give the power, to any inhabitant within hearing to order the removal of the nuisance?’2 As the grumbling author suggests, Londoners did not hear this nuisance as particularly novel, but found street musicians to be far worse than previous ‘trifling’ noises. In their complaints, Londoners located street music within a longer historical context and the soundscapes of their own memory. By the 1850s and 1860s some had lived long enough to witness the disappearance of the sounds of ‘old times’ from London during the early nineteenth century. News-horns, which had been the focus of complaints and the subject of various orders by the governing bodies of the City of London since the 1790s, were finally banned for good in the City of London and its liberties in 1833,3 with the sweep’s cry outlawed a year later.4 The thrust of this earlier legislation was then reiterated in 1839, when the Metropolitan Police Act banned both the dustman’s bell and the muffin-boy’s bell from London.5 Finally, the postman’s bell – which had existed since the 1710s – was discontinued by the post office in 1846.

These disappearances might not seem surprising. Histories of urban soundscapes have frequently fixated on historical fights against noise. Both noise and sensitivity to unwelcome sound seem to have consistently expanded over time.6 Yet from the vantage point of the 1860s, the disappearance of bells and horns was not celebrated but lamented. As an article in Punch reflected on the Morning Post’s curmudgeonly communication:

There is something to be said for the dustman’s bell, the muffin-bell, the newsman’s horn, and the cry of the sweep. These noises were occasional, temporary, not atrocious, and absolutely intolerable; and they were useful noises. The organ-grinder’s noise … is of no use to anybody, affords no one much gratification, and only serves little to amuse the idleness of a few idiots.7

In this telling, it was not that professional Londoners wanted silence rather than noise; it was that street music was not useful or predictable. The key objection of one of street music’s fiercest critics in the 1860s, Charles Babbage, was that it ‘rob[bed] the industrious man of his time’.8 Street music, unlike the bells and horns of Georgian London, did not bear news, act as a reminder, or proffer goods and services. The sounds of ‘old times’, as described in Punch, were helpful: their rhythmic, staccato presence in Londoners’ lives meant that they were familiar and reliable, and helped structure the urban soundscape. This chapter focuses on one of these vanished sounds of Georgian London – the news-horn. We begin with its creation, from a coupling of postal practices and newspaper marketing. We then follow its life through eighteenth-century streets. Finally, we trace its eventual death at the hand of legislators and its powerful afterlife in the memories of Victorian Londoners.

In tracing the sound of the news-horn, this essay advances two arguments. Firstly, rhythmic temporality was central to how Londoners perceived the soundscape of their city in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This also structured how sounds made their way into texts. News-horns were central to the shifting temporalities of news in the eighteenth-century city. They were part of a series of sounds that created affective rhythms of anxious expectation for news and emotional release on its arrival. During the 1790s an evangelical insistence on silent Sundays and a mercantile concern for the clockwork sounds of business clashed with the quickening rhythms of wartime news. During the 1830s the news-horn disappeared altogether. It was at these points, when the news-horn’s rhythms broke down, sped up, or clashed with other acoustic temporalities, that its sound resonated through the records of urban governance, magazines, newspapers, and satirical prints. Londoners described the quotidian urban soundscape when they were forced, like Henri Lefebvre’s rhythmanalyst, to re-hear it outside their daily listening habits.9 These moments help explain the functional utility of sound for eighteenth-century urbanites.

Secondly, the disappearance of the news-horn signalled a wider shift in London’s sense-scape. Scholarship on Victorian views of their Georgian predecessors has tended to focus on the positivity or negativity of their appraisals and forms of intellectual and literary influence.10 The news-horn offers another story. It was implicated in a series of conflicts over the timeliness of urban sound that came to a climax during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. These conflicts, which resulted in much of the early nineteenth-century’s legislative assault on horns and bells, produced a temporal rupture in London’s soundscape. In the period from the 1830s to the 1860s, writers on London used this rupture to develop a distinction between the ‘old’ times of Georgian London, signified by the soundscape of the Napoleonic Wars, and the new London of the mid-nineteenth century. They described a shift from staccato, timely sounds to a buzzing, constant, and unpredictable noise. The disappearance of many temporal markers removed elements which had previously structured the urban soundscape.

The historiography of urban sound has tended to locate the birth of auditory modernity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Developments in acoustics, sound recording, and telephony and the arrival of the automobile all produced significant changes in the soundscape – defined as both sounds and ways of listening.11 The implication is that the period that preceded the 1870s, before the technologizing of sound, was ‘early’ modern. Following the news-horn’s trail offers a different story, in which Londoners located a profound sense of auditory change in the early nineteenth century that added to their sense of Georgian London’s distinctiveness from its Victorian successor. The urban soundscape, still reverberating in the heads of mid-nineteenth-century writers, was one way in which Victorians were haunted by their Georgian past.

The Pastness of the Post-Horn’s Present

The news-horn was a relatively late arrival in eighteenth-century London, but it had some notable precedents. The most obvious of these was the post-horn. In the mid-sixteenth century the post-horn would have been blown only at the end of a town to clear the way for the speeding post-boy carrying official letters. Proclamations in 1583 and 1584 gave official protection to private letters in a public post, and the new public-ness of the post was announced by the more regular blowing of the post-horn and by the image of the horn itself. Post-houses were indicated by the sign of the horn outside the door.12 Each post-boy was instructed to ‘blow his horn so oft as he meeteth company, or passeth through a town, or at least thrice a mile’.13 With the rise of the mail-coach from 1784 onwards the post-boy’s horn did not disappear but fell into the hands of the mail-coach guard. It continued to announce the arrival of news, and its constant sound on highways and byways warned other travellers to vacate the road as the mail-coach sped by.14

The association between the sound of the post-horn and news was already apparent during the seventeenth century. In the 1630s the post office arranged regular weekly dispatches from London,15 and by the 1640s and 1650s posts departed twice weekly from the capital, bringing newsbooks with them.16 The 1690s saw the tri-weekly post joined by a series of new tri-weekly papers, published on the morning of the post to make possible their swift circulation.17 The intimate connection was recognized in the titles of papers: The Post Boy, the Flying Post, and The London Post. In the seventeenth century the Clerks of the Road began to use their franking privileges to send newspapers across the country free of charge, and by the mid-eighteenth publishers paid them to do so.18 By the 1750s, the six daily London newspapers were matched by a daily postal network that stretched across the country.19

The post-boy’s horn was thus an increasingly common sound on eighteenth-century roads and streets. But it could also be found on the printed page of newspapers, either in the masthead or indented at the beginning of the first article of an issue. In the 1640s a flurry of news-sheets contained large woodcuts of mounted post-boys blowing horns.20 The Post Boy, The London Mercury, The British Spy, The Middlesex Journal, and Bell’s Weekly Messenger are just a few examples of newspapers carrying images of horse-bound post-boys blowing their horns.21 On the masthead of The Old Post-Master a bearded post-man blows his horn as he rides, with the words ‘Great News’ flourishing, upside down, from the end of his horn.22 Even where the post-boy was absent, eighteenth-century newspapers still featured tubular sounds, in the form of Fame and her trumpet.23 Fame stood in for the newspaper press in satirical prints, loudly trumpeting virtue and exposing corruption.24 By the early eighteenth century the sound of the newspaper was that of the post-horn.

The post-horn is significant for an understanding of the relationship between news and time in the eighteenth century. The twanging horn compressed time and space in a way that made printed news feel more immediate. The potential for news-hawkers’ cries to alter the affective atmosphere of the city could already be detected in the early eighteenth century, when it was lamented that ‘a bloody battle alarms the town from one end to another in an instant. Every motion of the French is published in so great a hurry, that one would think the enemy were at our gates.’25

The same could be said of the post-horn. Newspapers frequently reported both the news and the manner of its travel. Reports of military victories and defeats were replete with postillions roving across the Continent and blowing their horns as they went.26 The columns of military news started with phrases such as ‘This moment arrives … preceded by six Post Boys blowing their Horns.’27 The sound of the post-horn put the reader in the action, collapsing two moments of news delivery – on English streets and at the scene of a battle – together. Yet the dating of accounts, frequently many days before the publication of the newspaper itself, also announced their anachronism: the sound of the post-horn beyond the reader’s home was both new and, by the time the reader had started reading the newspaper, already old. In an 1800 copy of a print from 1772, morning news-readers gathered near their village inn to read the morning paper, but the sign of the inn – the ‘Bugle Horn’ – gestured to the departed sound of news.28

The news-horn, on the page and on the street, indicated the ephemerality of print intelligence. This was amplified by comparisons between the post-horn and Fame’s trumpet. The British post-boy’s horn, like that belonging to Fame, was a long and thin instrument. In some early eighteenth-century newspapers, the placement of the post-boy with his horn and Fame with her trumpet on either side of the masthead encouraged comparison.29 Fame herself was sometimes represented as akin to a post-boy, intruding on Time’s quiet with her trumpet and instructing him in the latest news.30 Post-boys and post-horns were also portrayed as Fame’s messengers.31 The creation of contemporary fame through advertising ‘puffs’ and the puffing of the post-boy’s horn offered the potential for further analogies,32 and newsmen encouraged the comparison. Surviving New Year addresses, single sheets printed from the 1750s onwards for newsmen to distribute to their customers, were headed by images of Fame blowing her trumpet.33

The ephemeral echo of the news-horn represented the past-ness of the present that newspapers constructed. During this period Fame’s trumpet was frequently compared to an echo, ranging across continents and historical time.34 Likewise, the post-horn’s sound was an echo encoded in different forms, from military postillions to post-boy, to the woodcut and text on the newspaper’s page. This echo, an insistently historical record of time passed, reinforced the feeling of being caught between multiple temporalities that eighteenth-century news evoked.35 Scholars have argued that the development of newspapers in this period created a new experience of time: a de-temporalized contemporaneity that separated present from the past or future and divided history from news.36 Yet the news-horn fostered an experience of news in which past and present were connected: it produced a feeling that individuals were living in and through history.

By the mid-eighteenth century the post-horn had developed an expectant rhythm of emotional anticipation and release,37 and the horn’s complex temporality reinforced the affective rhythms that it created. Hearing the instrument’s signal induced a desire for news. In 1723 Joseph Addison wrote of being distracted ‘by a Post-Boy, who winding his Horn at us … I shall long to see the next Gazette’.38 The post-horn’s absence created anticipation of its arrival. The labouring poet Mary Leapor, awaiting a response to the verses she had sent to London, was ‘apprehensive of Fits at the sound of the Post-horn’.39 Similar affective rhythms applied to the newspapers that post-boys carried. A description of the stereotypical country gentleman, who was ‘anxious about the affairs of the nation’, noted that he was ‘miserable’ three days of the week without news, but ‘his spirits revive at the sound of the post-horn, when the mail brings him the London Evening Post’.40

The sound of the post-horn was a resonant container for emotion, filled by the anxieties and hopes of waiting readers and prospective writers, and produced an affective rhythm that was yoked to postal timetables. In 1795 a periodical correspondent asserted that ‘the sound of the horn … is more delightful to my ear than the softest touches of music attuned by harmony’.41 In contrast to Leapor’s anxious waiting, here the post-horn’s call was desirable and the anticipation described as positive. The precise emotions produced by the post-horn, when sounded and when silent, were not the same. However, they were part of the same affective rhythm. In The Task, Cowper portrayed the post-boy as a neutral vehicle for epistolary affect, ‘indiff’rent whether grief or joy’, whose ‘twanging horn’ both signified the post’s appearance and ignited Cowper’s reflection on its emotive potential.42

The News-Horn Arrives in the Metropolis

During the 1770s the sound of news in towns and cities began to change as the post-horn was joined by – or rather became – the news-horn. The proliferation of newspapers in London created a competitive market for news. In 1772 John Bell, John Trusler, and Henry Bate joined together to publish the Morning Post. With the competition for readers high, newspapers had to distinguish themselves in new ways. From the beginning Bell, Bate, and Trusler provided the hawkers of their new paper with horns, like those used by post-boys, which they would blow as they wandered the street selling their wares. Bate and Trusler even dressed up as the news-boys themselves on a visit to the Pantheon Masquerade in 1772.43 By February 1773 other masquerade guests were mimicking the Morning Post costume: one Mr Dawes dressed as ‘a Black Messenger to the Morning-Post’ and ‘blew his horn as much out of tune as the person he represented usually does in the street’.44 By this time, the association between news-hawkers and the post-, now news-, horn was common metropolitan knowledge.

At first aggrieved newsmen attacked this innovation. After Bell, Trusler, and Bate dismissed them, the Post’s printers Corral, Bigg, and Cox began to produce their own rival Morning Post. Corral, Bigg, and Cox felt particularly aggrieved by Bell’s tactics. Before the 1770s the horn had been connected to the postal delivery of news rather than to hawking it on the streets. Those newspaper mastheads from the early to mid-eighteenth century that depicted news-hawkers rather than post-boys portrayed men walking and crying papers without the aid of trumpets.45 Cox and Corral complained that Bell had hired ‘a pack of vagabonds, clothed them like anticks, and sent them blowing horns about the town’ and that, because of this, long-standing newsmen found themselves ‘robbed in part of their daily bread and injured in their respective news-walks’.46 Bell’s innovations disrupted the perambulatory rhythms of newspaper selling.

Cox and Corral were eventually forced to change their title to New Morning Post in 1777.47 But this was not before Bell responded to the competition by kitting out the Morning Post’s news-boys with a new uniform to accompany their news-horns. In 1776 Horace Walpole witnessed the Post’s hawkers in a show of strength on London’s streets and ‘concluded it was some new body of our allies, or a regiment newly raised’.48 These liveried, trumpeting news-boys played on the existing connections of military postillions with domestic post-boys that had developed in earlier in the century. Yet now, rather than being linked to the post alone, they were let loose to roam the streets of London.

At first the complaints about the news-horns were few. The timing of their use, announcing the publication of the morning edition of the paper, fitted into the existing rhythms of the London soundscape. In 1776 one ‘Momus’ penned a letter from the perspective of a country-dweller who had moved to London. The gentleman’s attempts at sleep were ruined by a series of morning sounds that began with bawling chairmen, followed by the dustman’s bell, the chimney-sweep’s cry, the milk-women’s screams, and the rattling of carriages. But it ended with ‘Morning-Post horn, which awakes as thoroughly as the last trumpet: in fact, it is the concluding argument to every attempt to sleep’.49 While annoying for the country-dweller, for the urbanite the sound of the news-horn fitted into a recognizable daily rhythm of sounds.

In the late eighteenth century, Britain’s rapidly growing and increasingly mobile population created the context in which ever greater numbers of individuals were strangers, not just to each other but to the rhythms of their sensory surroundings.50 Travelling ears were more likely than those of city dwellers to hear less intelligible soundscapes as offensive noise. Irritation at the post-horn was represented as the product of this mismatch. Of course, Momus was undoubtedly a Londoner writing for a metropolitan audience. He therefore had to imagine himself into the ears of a country visitor in order to describe the city’s sounds. This trope was not unusual. The 1814 Something Concerning Nobody played on the same joke. In a chapter on hearing, ‘Nobody’ goes on an extended trip to the country, but ‘upon his return to London’ he does not ‘relish the loud blasts from the horn of the newsman’, which ‘incessantly annoyed him’.51 ‘Nobody’, that is to say no Londoner, heard the sound of the news-horn, since Londoners had quickly become used to its daily rhythms. Writers also deployed the same joke the opposite way around. When the stereotypical cockney ‘Timothy Trudge’ visited a country retreat, he thought that the birds were ‘bow bells a ringing’ and the ‘tanta-a-rara’ of the ‘hunter’s shrill horn’ was the ‘the horn boys, retailing newspapers’.52 The misidentification of sound sources came from the confusion of country and city lives.

In the 1770s complainants about news-horns were represented as non-Londoners: either over-sensitive oddballs who failed to grasp the necessity of news-noise or country bumpkins who were unhabituated to its rhythms. In the 1774 play The Choleric Man the unusually angry Mr Nightshade – having affronted his family and every one of his country neighbours – visits his brother in the city. The play climaxes with an incident in which Mr Nightshade knocks a news-boy to the ground, after the latter has blown ‘a damn’d blast on his horn, point blank into my ear, flourishing his newspapers full in my face’. Nightshade’s interlocutors are incredulous – does he not know that circulation of news ‘as necessary to the city as the circulation of cash?’53 In an attempt to reform his unruly passions Nightshade’s relatives pretend that the news-boy is dead and, in closing, the choleric man swears to reform his ways. In Nightshade there were echoes of Ben Jonson’s 1609 character Morose, another over-sensitive set of ears, who lived down a little alleyway that rumbling carts and London cries could not reach.54 Yet in Jonson’s play Morose’s auditory sensitivity was a side-line to the main plot. In The Choleric Man Nightshade’s irritable listening provided the main moral lesson of the performance: that city life required the control of the passions and the senses.

The Soundscape Out of Joint

By the 1780s the proliferation of newspapers (and the hawkers trumpeting them) had produced a soundscape defined by the constant sounds of news as more newspapers adopted the Post’s advertising strategy.55 Morning, noon, and evening all saw the publication of multiple papers and editions. Technically it was illegal to sell newspapers on Sundays, but from 1779 a range of Sunday newspapers emerged, and by 1812 there were eighteen such publications in London.56 George Crabbe’s ‘The Newspaper’, written in 1785 and republished in 1807, depicted an urban culture of news in which ‘Post after post succeeds, and, all day long, / Gazettes and Ledgers swarm, a noisy throng’, all sold by the ‘rattling hawker’ with his horn.57

The affective rhythm of news established in the first half of the eighteenth century escalated in the context of the war against Revolutionary France.58 The sound of the mail-coach, bringing newspapers to the provinces, was described as a form of emotional contagion, linking the nerves of the body politic to the passions of subjects anxious for news.59 News from the Continental conflict came thick and fast, and the sound of London’s news-horns – accompanied by the hawkers’ cries of ‘Great News!’ and ‘Bloody News!’ – intensified. The metropolitan soundscape was rendered ill at ease by war, and the sound of the news-horn was almost constant. The multitude of newspapers, with their many editions, fed off a metropolitan readership sensitized by war to the anxious affect of news. Before the 1790s the news-horn had been part of a eurythmic soundscape in which several interlinked sounds worked in tandem, but the war undid that balance. In 1828 a writer to the Mirror of Literature described the 1790s thus: ‘newsmen’s horns so far transcended the united noises of all other vociferications, that the magistrates of the city … found it necessary to legislate specifically against them. No other trade could gain a hearing, so incessant and obstreperous were their blasts.’60 The temporal fixity of the news-horn was deteriorating. Yet by the mid-1790s, as the quotation above suggests, the news-horn was also creating a sense of arrythmia within the London soundscape as its sound clashed with other metropolitan rhythms.

In 1796 news-horns suddenly appeared in the records of civic governance. The complaints surfaced in the annual wardmotes. By the mid-eighteenth century wardmotes had largely lost their earlier role in prosecuting urban nuisance, and from the 1750s onwards many wardmotes failed to present any nuisances at all. It was thus especially significant that in the presentments for 1796 several wards, hitherto almost completely silent on auditory nuisances, issued complaints about news-horns. The wards of Bridge, Castle Baynard, Cordwainer, Cornhill, and Cripplegate Within all offered complaints,61 and the rash of presentments were reported in the newspapers.62 The minutes and journals of ward and civic government are frustratingly silent on specifics, the actions on news-horns possibly being lost within generic references to nuisance.63 However, two complaints reverberate from the civic documents. Both demonstrated the news-horn’s arrhythmia-inducing influence. The first came from Cornhill: ‘the practice of sounding horns by the hawkers of newspapers and other publications is … a serious evil to the merchants and traders who frequent the royal exchange which being the great centre of commerce should be particularly guarded from unseasonable noise and interruption’.64 The staccato sound of the news-horn and the cries of ‘great news’ and ‘bloody news’ were antithetical to the soundscape cultivated in the Royal Exchange. This was a space of news, which was crucial to the negotiation of trade, credit, and insurance. But the sound of the exchange was a measured buzz and the ‘busy hum of a hundred voices’.65 Here trade relied on the direct oral transmission of news, contained in packets and letters from across the globe, from mouth to ear. The only interruption to this soundscape was supposed to come from the chimes of the exchange’s clock. This clock, using four bells, struck the quarters and the hours, repeating the latter at the half hour. The tunes played by the chimes included the ‘104th Psalm’, ‘God Save the King’, ‘Britons Strike Home’, and ‘There’s Nae Luck aboot the Hoose’.66 These chimes located the Royal Exchange at the commercial centre of a Protestant, British, imperial London, and their sound helped manage the mercantile clock time on which business depended. The cries of ‘dreadful news’ dented the confidence in British imperial power that the chimes aimed to inculcate.

Not only was the sound of the news-horn untimely and interruptive; it was also a reminder of the unpredictability and unreliability of the news on which merchants and investors relied.67 Public and mercantile credit depended on a constant performance of solidity and trustworthiness, a performance embodied in the workings and architecture of spaces such as the Royal Exchange and the nearby Bank of England.68 Yet news-horns required an anxious uncertainty for their advertising to work: they simply announced that news existed, not what it was.69 The news-boys’ patter worked by constantly asserting the novelty of their news and its great, bloody, or dreadful qualities. But these cries, like the news-horn, failed to tell listeners whether the news was truly fresh or what it portended. Some Londoners felt aggrieved by the news-boys who resold old papers as a ‘second edition’.70 News-boys were ‘proclaiming “great and extraordinary news,” when the papers they have for sale contain not a single article either of novelty or of interest’.71 The sound of the news-horn no longer guaranteed the freshness of news. It therefore disrupted the circulation of intelligence on which the Royal Exchange relied.

Cornhill was not the only ward to complain: other wardmotes grumbled that news-horns ‘do disturb the peace of the inhabitants and interrupt them in public worship on the Lords day’.72 The inquest jury of Cripplegate Within sounded what was to become a keynote in attacks on the Sunday press. With the growth of the Sunday newspapers, the news-horn disrupted the solemnity of Sunday worship. In response to the wardmote’s inquests, the Court of Aldermen ordered the Town Clerk to write to the Lord Mayor and request that he ‘take such measures as his lordship shall be advised to put a stop to such evils and disturbances and punish all persons who shall be guilty of’ using news-horns.73 Later commentators suggested that – if not in Westminster then at least in the City of London – news-horns had been ‘put down’ in the late 1790s.74

Yet the news-horn continued to punctuate London’s Sunday soundscape. In 1799 Lord Belgrave, William Wilberforce, and their evangelical allies unsuccessfully attempted to pass a bill in parliament that reinforced legal restrictions on Sunday newspapers. The evangelical press continued to complain that hawkers and mail-coaches blew their horns ‘even during the time of divine service’,75 causing an ‘offence to the feelings of all who retain any reverence for the sabbath, or any desire of observing it’.76 Evangelical critics identified the central problem with regulating news-horns. The sound of the news-horn spread easily, making it even more difficult to control: ‘every lad who can blow a horn has only to furnish himself with a quantity of the papers’ and thereby ‘add considerably to the profanation of the day’.77 It was easier to attach noise to the longer list of neighbours’ grievances against a particularly rabble-rousing establishment, but the frustratingly mobile news-boy presented a more difficult prospect.

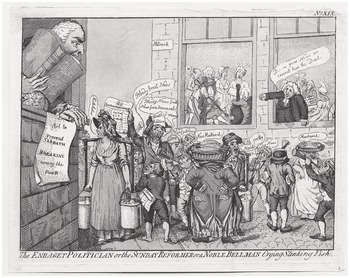

For some readers this seemed an insignificant trifle. Satirists mocked evangelical concerns about the ‘naughty newsmen … blowing the horn of sinfulness before them!’78 The parliamentary proposals met with vociferous opposition, especially from Richard Brinsley Sheridan, who made a telling point about the hypocrisy of a parliament that legislated for a selective Sabbatarian silence by restricting news-horns but not ‘routs, card-parties, concerts, &c.’79 The satirists leapt on this double-standard. Isaac Cruikshank produced a print that riffed on Hogarth’s Enraged Musician, swapping out the French musician for the evangelical politician as the new enemy of popular street culture (see Figure 5.1). Part of the problem with the news-horn was that its sound revealed the acoustic porosity of the built environment: it disturbed both the domestic quietude of the home and silent solemnity of church services. With the sash-windows of Grosvenor House wide open and a concert taking place inside, Cruikshank suggested that the noise of aristocratic sociability was just as loud and potentially disturbing to others as the sounds of news-hawkers.

Figure 5.1 Isaac Cruikshank, ‘The Enraget [sic] Politician or the Sunday Reformer or a Noble Bellman Crying Stinking Fish’, 1799. Hand-coloured etching on paper, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, 799.06.25.04.

Beginning in the 1810s, a creeping programme of legislation slowly enlarged the times and places in which the news-horn was declared illegal. An 1813 act bolstering the powers of the Marylebone improvement commission enacted a penalty for anybody blowing a news-horn on any Sunday or religious holiday during the ‘Time of Divine Service’.80 An 1812 act amended this to include stagecoach and mail-coach horns.81 An 1816 act for building a new parish church and chapel in St Pancras extended this prohibition in the parish to the whole of any Sunday or holiday.82 The same provision then appeared in acts for building other new London churches.83 By 1822 this provision had been extended beyond the sabbath to include ‘any time’. This wider provision was included in a slew of subsequent improvement and church building acts. It was also included in later metropolitan police acts.84 By the late 1830s the illegality of news-horns in much of the metropolis – indeed in many other towns and cities across the country – was an established fact.

The news-horns did not go quietly or without resistance. Newspapers reported problems with regulating newsmen. In Liverpool banishing horns led to people missing the newsmen and to accidents with mail-coaches that could no longer warn pedestrians of their passing: ‘why’, one local paper asked, did the authorities not ‘control the excess – the nuisance – and not the good use of the horn?’85 In Bristol the town council initially refused to censure newsmen for using their horns because those ‘desirous of having a paper on their breakfast table must otherwise station a servant at the door to watch for the arrival of the newsman’.86 Finally, in London a constable informed the inhabitants of Marlborough Street that ‘if they blew a horn, then they would be liable to punishment; but they could not be punished for merely making a noise with their maxillary organ’.87

In 1828 one Londoner complained that ‘in no respect has the liberty of the subject degenerated to such outrageous license, as in this very particular noise’. It was as if ‘dissonance was a fundamental article of Magna Carta, and silence as unconstitutional as ship money’.88 In one respect this author was right, since the freedom of speech – including the cries of hawkers – was more difficult to legislate against than the instruments of street musicians. In the 1840s and 1850s the implementation of legislation proved difficult with the policing resources then available.89 The news-boys lost their horns, yet they carried on crying the news.90

The Sound of Old Times

With the end of the Napoleonic Wars the news-horn continued to transform the feelings of its listeners, but now it exhibited a different relationship between temporality and feeling. The end of the conflict left Britain already nostalgic for the ‘battle-sound’ of a time when the ‘post-boy’s horn the laurell’d record’ told.91 The news-horn held on until the late 1830s in many parts of the country, yet it came to be remembered as the sound of wartime and therefore of ‘old times’. In the 1840s Henry Mayhew included the newspaper seller among the street criers described in his London Labour and the London Poor. One interviewee described the news-horn as the sound most representative of ‘what is emphatically enough called the “war-time”’.92 The disappearance of the news-horns that had ‘announced … the martial achievements of the modern Marlborough’ was an indication that ‘times are not as they were’.93 With peace, the news-horn’s sound became an antiquarian curiosity for amateur archaeologists, an artefact linked to a time ‘during the war’.94 When Thackeray evoked the anxious atmosphere of wartime London in the Napoleonic era he turned to ‘the newsman’s horn blowing down Russell Square about dinner-time’.95 In the final 1850 version of The Prelude Wordsworth replaced the arboreal metaphor for rumour found in the 1805 version with the trumpeting newsman: ‘in every blast’ of the ‘street-disturbing newsman’s horn’ the British had found ‘a great cause record or prophecy’ of France’s ‘utter ruin’.96 By the late 1830s the horn’s disappearance was not celebrated but lamented. In his survey of London Charles Knight lamented the loss of these arrhythmical sounds, since they had done ‘something to relieve the monotony of the one endless roar of the tread of feet and the rush of wheels … The horn that proclaimed extraordinary news, running to and fro’ among peaceful squares and secluded courts, was sometimes a relief.’97 That relief was remembered, through the rose-tinted spectacles of Britain’s victory in 1815, as a source of celebration rather than aggravation. Mayhew’s interviewees in the 1840s still recalled the news-horn’s sound on the streets that surrounded them, but by the 1860s their numbers were thin. Lost to the hearer, the news-horn was fixed in print: ‘we see it only on the face of one of our weekly newspapers’.98 Its sound no longer rebounded between the street and the printed page. The horn’s echo lost the reverberating qualities it had acquired in the eighteenth-century culture of news, and by the end of the 1840s its sound had fallen into an irretrievable past.

Conclusion: Generational Rhythms

The news-horn’s history reveals much about the temporality of news and sound in the eighteenth-century city. An influential strain of historiography has posited that newspapers in this period created a modern sense of contemporaneity that unified people across geographical boundaries in an elongated ‘now’, which was separated from past and present.99 However, recent work has suggested that in fact news culture was decidedly post-modern, with its multitude of competing temporalities.100 The news-horn fitted within this post-modern culture of news: its main effect was to rupture and re-arrange time. In this sense its sound might be described as sublime. Indeed, the cries that accompanied it – of ‘great’, ‘extraordinary’, and ‘dreadful’ news – shared their language with the affective vocabulary of Enlightenment aesthetics. In the late eighteenth century, Johann Gottfried Herder suggested that sublime sounds had the power to suddenly transplant individuals into different temporalities: ‘all at once the thread of our thoughts and moments of time is torn apart’.101 This was precisely the feeling that the news-horn conveyed as it blazed along the street and its blast interrupted the thoughts of passers-by.

The news-horn produced a feeling of temporal dislocation in its hearers, but the nature of that feeling shifted over time. Sensitization and habituation are fundamental in dictating what traces of the sensory past end up in the archive.102 Yet linking individual habitus to wider shifts is a difficult task. Studies tend to do one or the other.103 The case of the news-horn suggests that sensory historians might productively link the two through examining generations, the lifespans of sets of individuals, when considering processes of sensory change.104 This chapter is also an argument for another way in which scholars might write more nuanced and convincing histories of the urban soundscape. In particular it has argued for the utility of rhythm and rhythm analysis for historicizing the senses and the city. Histories of listening have tended to draw on a fairly narrow range of narrative emplotments. One traces new sounds which encouraged new ways of listening: for example, amplification or the automobile.105 At times this can come close to the auditory equivalent of technological determinism.106 The other unveils how new modes of listening developed from beyond the realm of auditory culture. This represents auditory shifts as the consequence rather than the cause of change, the flotsam and jetsam produced by, for example, the rise of the middle class or the proliferation of print.107 The two approaches share a tendency to reify older narratives, simply adding the senses to our appreciation of an entrenched period, event, or moment.

This chapter has offered another approach. To describe the news-horn’s rise and fall as the fate of a novel sound or the product of a new way of listening would be inadequate. The sound had been heard on the highways and byways of England since the sixteenth century, and the affective rhythms of listening it inculcated had existed since the late seventeenth century. What changed was the speed and durability of those rhythms. During the 1790s they sped up to such an extent that they broke down and came into conflict with the daily rhythms of the street, the weekly rhythms of the sabbath, and the busy hum of London’s merchants and financiers. Long-existing sounds and rhythms of listening came into conflict. The result was the enforced disappearance of the news-horn from London’s streets. A range of other sounds – from the sweep’s cry to the postman’s bell – followed. For those who had lived to see them disappear, what remained was a new London soundscape, characterized by a roaring blanket of sound.