Diagnosis is fundamental to psychiatric treatment, yet there has been little research on the impact that diagnosis has on people with mental health problems. The diagnoses associated with the experience of psychosis, especially schizophrenia, can be particularly stigmatising, but little is known about the impact receiving a diagnosis has on people. The existing research has shown that diagnosis can have both a positive and negative impact on an individual. Reference Hayne1 Hayne looked specifically at the experience of diagnosis by exploring clients’ perspectives on being named mentally ill. Reference Hayne1 She found that diagnosis was very powerful but acknowledged that the effects could be contradictory; on the one hand legitimising personal characteristics and on the other de-legitimising the self. The research identified the potentially positive effects of diagnosis by making illness evident and treatment possible but emphasised that if diagnosis is to be helpful it needs to be transmitted in a way that makes people feel more knowledgeable.

Other research in the area has emphasised some of the negative aspects of diagnosis, particularly those associated with the impact of stigma. Reference Vellenga and Christenson2–Reference Dinos, Stevens, Serfaty, Weich and King5 Research has shown that stigma towards people with mental health problems is widespread Reference Byrne6,Reference Byrne7 and that it is particularly prevalent for those with a psychosis-related diagnosis. Reference Dinos, Stevens, Serfaty, Weich and King5 Research on the experience of stigma by those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia has shown that they face prejudice and discrimination from a range of sources in society. Avoidance/withdrawal was found to be a widespread coping strategy for stigma leading to social isolation and social exclusion. Reference Knight, Wykes and Hayward4

The aim of this study was to explore the impact of diagnosis on people who experience psychosis from a service-user perspective. The research was user-led, in that service users controlled all stages of the research project.

Method

Participants

The participants were people with experience of psychosis and diagnosis who use/have used services within Bolton, Salford and Trafford Mental Health Trust (now Greater Manchester West NHS Foundation Trust). They were recruited though local mental health groups and psychology services, and selected by convenience sampling. The eight people who were interviewed (six male and two female) were aged between 18 and 65 years (actual ages of participants were as follows: 21, 26, 28, 32, 37, 45, 49 and 59 years of age). Six were White British and two were African–Caribbean. The participants had received a range of diagnoses including bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorder. Some participants had received multiple diagnoses.

Procedure

The research was conducted by two service user researchers (E.P. and M.K.). Research supervision was provided by clinical psychologists (M.W. and A.P.M.). A steering committee of local service users was established to support the user researchers and to decide about the topic, provide guidance on the design of the research and have input into the analysis. It was agreed to conduct semi-structured interviews to obtain in-depth data on people's experience.

The interview schedule was designed by the user researchers with the guidance of the steering committee. It provided a guide to the topics covered in the interview. Participants were asked about their experience of diagnosis, their knowledge about their diagnosis, how they felt when they were first diagnosed and how their diagnosis affected them. They were asked to identify what had been helpful and unhelpful about their diagnosis. Finally, they were asked about their experience of stigma and discrimination. The participants were interviewed individually by one of the user researchers. The interviews lasted between 20 and 60 min. Each interview was audiotaped with the consent of the participant and transcribed verbatim.

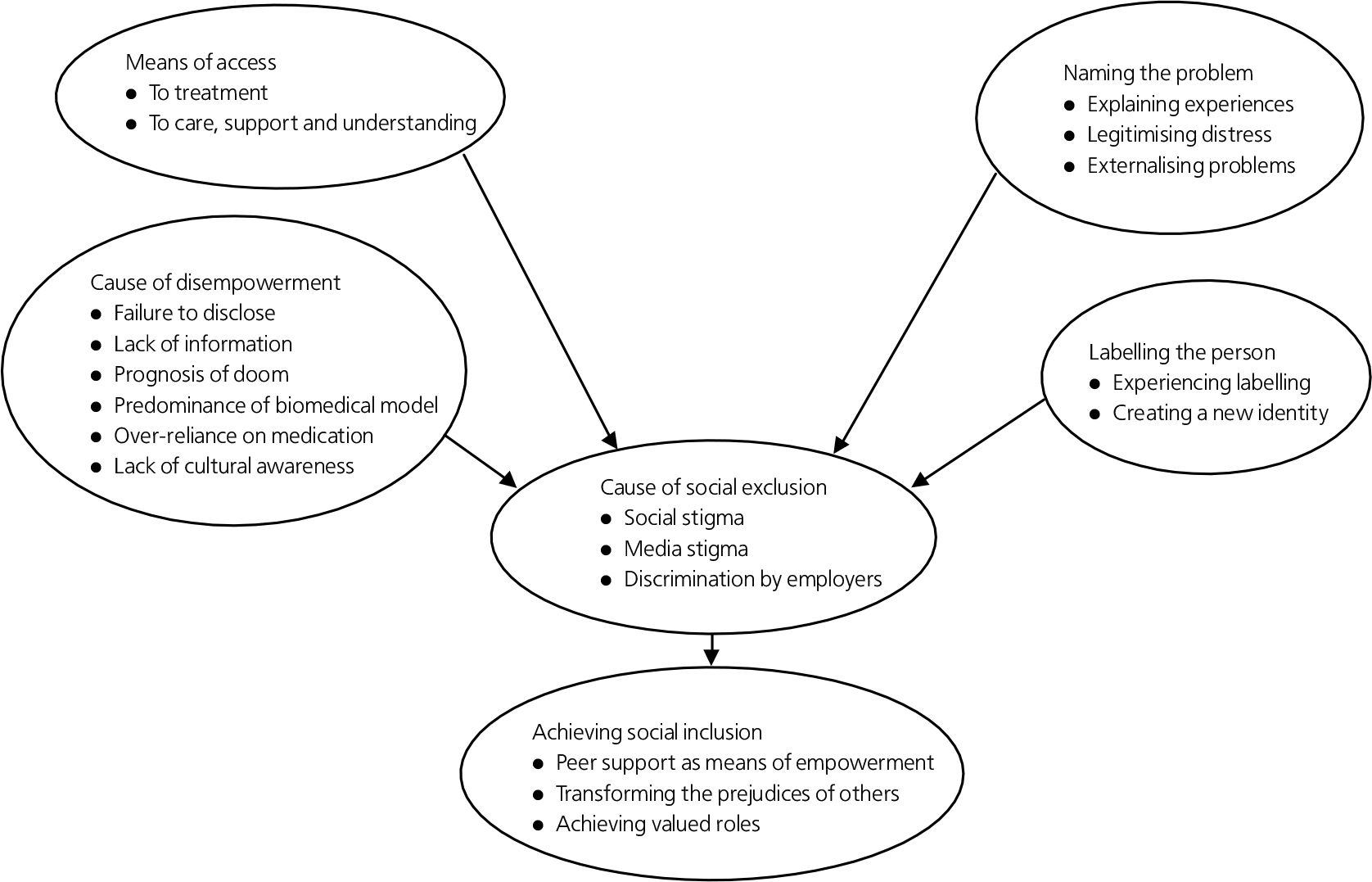

Fig. 1. Impact of diagnosis: key themes and subthemes.

Data analysis

Interpretative phenomenological analysis was the method used to analyse the data. Reference Smith, Osborn and Smith8 This is a method that is particularly suited to the exploration of subjective experience as it is concerned with gaining ‘an insider perspective’ on the area being studied in order to understand it from the perspective of the person experiencing it. At the same time, it recognises the role of the researcher as an interpreter in making sense of another person's experiences. Each transcript is then analysed individually in order to identify emerging themes. Once the analysis of all the transcripts is complete, the final key themes and subthemes are identified and agreed upon. The appropriateness and reliability of the themes is tested initially through discussion between the two user researchers. The final key themes and subthemes together with the corresponding data are considered by both the supervisory team and the steering committee for their relevance and reliability.

Results

The analysis produced a set of 6 key themes and 19 subthemes, which are graphically represented in Fig. 1. In the discussion, each of the key themes is illustrated with a quote and discussed in greater detail with reference to the subthemes. The contradictory nature of the themes reflects the fact that the research found that the impact of diagnosis could involve both positive and negative elements. Some people will experience diagnosis more positively or negatively than others but for all there were both elements present to a greater or lesser degree in their experience.

Means of access

They realised that there was something seriously wrong and eventually they sat down with me and talked to me and it was then that I opened up and said to them, look this is what has happened to me, these things have happened, I’ve tried to kill myself, just little things like that. (Tom)

For some, diagnosis had been experienced positively as a means of access to treatment. The treatment generally involved medication and for some individuals it also involved access to psychological therapies such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). For some having a recognised diagnosis meant that they received more care, support and understanding both from mental health professionals and family and friends.

Cause of disempowerment

I think when I was diagnosed with irritable bowel I didn't know what irritable bowel was… but I got given so much information and I got a bowel specialist, I got everything thrown at me that I needed in order to deal with that chronic condition. With this [a diagnosis of bipolar disorder] which is far more serious I got a packet of lithium and put out on the streets. (John)

However, for others, diagnosis had primarily been a cause of disempowerment. Some of the people interviewed had experience of a diagnosis not being disclosed to them and only found out second hand. Where diagnosis was disclosed, sometimes the lack of information that accompanied that disclosure was one of the main causes of disempowerment. Lack of information meant participants often experienced diagnosis as ‘a prognosis of doom’ about their future. The research also found that the predominance of the biomedical model and an overreliance on medication as sole treatment could be disempowering to service users. For the Black participants, a reported lack of understanding and awareness about cultural difference also contributed to their sense of disempowerment.

Naming the problem

I feel that there's an illness… but I do really. It's not me as such it's something that's on top of me. (Joan)

Diagnosis could provide a helpful framework for individuals to understand and explain their experiences of mental distress. Some participants described the experience of receiving a diagnosis as ‘a relief’ to finally know what was wrong with them. They felt that a diagnosis helped to legitimise their experience of mental distress and it enabled them to gain more support and understanding from family and friends. Diagnosis also provided a means for people to externalise their problems rather than feeling they were personally responsible for them. It was helpful for them to understand their distressing experiences as being a product of an illness that was something separate from the self.

Labelling the person

I just thought schizophrenic people go round murdering and raping people, you know. I didn't know nothing properly about schizophrenia at that time so that's my initial thought. I can remember actually being told… I wasn't well at the time. I went absolutely bananas you know, yeah, throwing the bloody furniture everywhere. They pinned me down, give me injection and… because they were trying to tell me I got schizophrenia and… I’m not schizophrenic, do you know what I mean. (Paul)

In contrast, diagnosis also involved an element of labelling, which was usually stigmatising. Where a lack of information accompanied a diagnosis, the process was more likely to be experienced negatively as the labelling of the individual. The experience of being diagnosed could also lead to the creation of a new identity as ‘a schizophrenic’, for example, which could hinder the recovery process. There is evidence from the interviews that people alternate between referring to their diagnosis as something they have, ‘I’ve got bipolar’, and something that they are, ‘I’m bipolar’. This suggests that the ability of diagnosis to serve the function of externalising peoples’ problems as an illness and protecting their concept of ‘self’ is never fully realised.

Cause of social exclusion

I lost all my friends… yes I lost them all… it was just being in hospital and then when I did come out of hospital they would taunt me and I would have side-effects. I had side-effects from shaking, like this, and you know they would taunt me about, you know. I just lost all my friends with being in hospital. (Paul)

Regardless of whether diagnosis is experienced positively as ‘a means of naming the problem’ or more negatively as ‘a cause of labelling the person’ it was found to be a potential cause of social exclusion for all. Participants talked about the social stigma of having a diagnosis. Some participants had lost friends as a result of their experience of mental health problems and diagnosis. Many participants noted they were wary of telling new people they met about their diagnosis due to stigma and discrimination. Most participants were also concerned about being open about their diagnosis to potential employers for fear of discrimination.

Achieving social inclusion

I chatted to quite a few people, a lot of people, with that diagnosis and it kind of helped because you could be so open about it and it was such a relief to be able to say, you know what, this happens to me and recognising that… everyone kind of experiences similar things and it's quite comforting to know. That really helped me sort of come out with a lot of things in my life and change my life. I felt right, you know, this is who I am and I am quite proud of the fact that this is who I am. Whereas before I wouldn't discuss it with anyone, I’d just disappear for three months and people would be like where's she gone, you know, now I’d be quite open about it and going for a job I was quite open about what my diagnosis was. (Sarah)

Despite the fact that that all the participants experienced elements of social exclusion as a result of their mental health problems and diagnosis, many went on to forge new social networks and achieve valuable roles in society. Peer support was an important means of empowering participants to be able to do this. Participants’ willingness to be open about their experience of mental health problems and diagnosis also helped to transform the prejudices of people they met. Finally, despite the stigma and discrimination that participants faced in society, they went on to achieve valued roles in both paid voluntary work and employment.

Discussion

Findings

The findings highlight the contradictory nature of the impact of diagnosis. This broadly translates as a ‘means of access’ v. a ‘cause of disempowerment’ and as ‘naming the problem’ v. ‘labelling the person’. Although some participants experienced receiving a diagnosis as a predominantly positive experience, they still identified it, as other participants did, as a ‘cause of social exclusion’. However, despite the experience of stigma and discrimination, participants were successful in ‘achieving social inclusion’ through rebuilding social networks and achieving valued roles in society.

The contradictory nature found in the impact of diagnosis is consistent with other research carried out in the area. Reference Hayne1 The stigma and discrimination identified by the research is also highlighted in other studies. Reference Vellenga and Christenson2–Reference Dinos, Stevens, Serfaty, Weich and King5 Whereas research on recovery has shown the importance of empowerment, rebuilding social support and active participation in life, Reference Pitt, Kilbride, Nothard, Welford and Morrison9 stigma and discrimination serve to lower self-esteem, create social isolation and reduce social roles. Reference Knight, Wykes and Hayward4–Reference Byrne7 Therefore the effects of stigma resulting from a diagnosis can play a role in relapse and hinder the recovery process.

Strengths and limitations

The user-led nature of the research ensures that the topic under investigation is one of concern and interest to services users. Given the importance of diagnosis to psychiatric treatment for psychosis and its potentially stigmatising effects, it is perhaps surprising that more research has not been carried out in this area. In that respect, the research makes a valuable contribution to extending our knowledge about the impact of diagnosis on people who experience psychosis. However, it is a small, exploratory piece of research only and the main limitation must be the inability to generalise from such a small sample size. The participants were recruited mainly through service-user groups and their involvement in such groups may make their experiences less representative of service users. There is clearly a need for a larger quantitative study investigating the impact of diagnosis with a representative sample. Diagnosis has an impact too on the family and friends of the individual diagnosed and research in this area would also be valuable.

Implications

The study has particular implications for psychiatrists in their role in imparting diagnosis. The aim should be to maximise the potentially positive role that diagnosis can have for service users while minimising the more negative aspects. There is clearly a sensitive decision to be made about when to impart a diagnosis in relation to an individual's illness (e.g. in early phases of psychosis, it can be very difficult to establish an accurate diagnosis, and this has led to a recommendation that services embrace diagnostic uncertainty). 10 Imparting a diagnosis effectively requires some understanding of the potentially damaging impact that diagnosis can have on a person's sense of self and ability to lead a full life. In acknowledgement of this, there needs to be sufficient time spent in both explaining a diagnosis and exploring the impact it has on a particular individual, their life and relationships.

Information on what a diagnosis means is particularly important at the time of diagnosis. Many service users will have little knowledge about different diagnoses and receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia, for example, can be a frightening experience if not explained properly at the time. Individuals are often left to their own devices to search for information and support networks. This is particularly difficult for an individual if they are unwell at the time of diagnosis. There is no doubt that the information and support networks are out there. MIND, for example, publish their own information booklets on various mental health problems and there are a range of support organisations for people with different diagnoses. There is an urgent need for a more systematic approach to information giving in relation to psychiatric diagnosis within the NHS, including some acknowledgement of limitations such as difficulties regarding predictive validity.

It is also important that a diagnosis is imparted with a sense of hope for recovery. Research on recovery identifies the importance of ‘hope for a better future’ in promoting recovery. Reference Pitt, Kilbride, Nothard, Welford and Morrison9 This current research indicates that for some people when this did not happen, diagnosis was experienced as ‘a prognosis of doom’. The recovery literature emphasises the importance of relationships between mental health professionals and service users being ‘hope inspiring’, Reference Repper and Perkins11 and this is particularly important in relation to diagnosis. Diagnoses should be imparted and discussed positively as a tool to aid recovery rather than as a life sentence to illness and exclusion.

Peer support is identified by the research as important in normalising a diagnosis and providing individuals with hope that they can recover. Being able to meet people with a similar diagnosis can be crucial as a means of sharing experiences and inspiring hope for the future. The benefits of psychoeducation groups are recognised and there should be far greater opportunity to participate in these at the time of diagnosis. Self-help groups too provide a similar function and information on their availability locally should be widely available at the time of diagnosis and during the course of treatment.

Finally, there is a need for more training for mental health professionals on the impact of diagnosis and the support individuals need in relation to their diagnosis. The dearth of research in this area is unfortunately a sad indication of the importance placed on this area within the current services. Mental health services are increasingly emphasising the importance of promoting recovery and social inclusion. If mental health professionals are to respond effectively to this they require a better understanding of the impact that diagnosis can have on individuals and their lives. Only through incorporating this knowledge into their practice will they be able to genuinely support service users in their recovery and help to facilitate their participation in society on an equal basis.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the individuals who participated in this research and the members of the steering committee who provided advice and support throughout the project.

Sadly, Martina Kilbride died following the completion of this research; she had strong views about diagnosis and the other authors would like to dedicate this article to her memory.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.