Understanding if and when constituent groups are represented in their legislatures are fundamental questions in understanding democracy and representation in the United States and around the world, and have long been a fixture in legislative scholarship. Though there are a number of studies that demonstrate the representational inequality that exists for members of disadvantaged groups such as racial minorities or the poor (e.g., Reference Griffin, Newman and WolbrechtGriffin and Newman, 2008; Reference CarnesCarnes, 2013), gaps remain in the literature surrounding the situations in which members of Congress actually do engage in representational actions benefiting these groups. The passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, the GI Bill, Medicare and Medicaid, the Equal Rights Amendment (which did pass through Congress, even if it was not ratified), the Violence Against Women Act, and others are a testament to the fact that Congress at times attends to the needs of disadvantaged groups. Yet, there is not a clear picture of when and why this happens. Who, then, are these members of Congress that make the choice to fight on behalf of the disadvantaged?

In this chapter, I review the current state of the literature around congressional representation and develop a theory for when and why members of Congress choose to form a reputation as a disadvantaged-group advocate. In doing so, I reexamine how scholars have conceptualized the representational relationship between members of Congress and their constituents, and offer a more realistic portrayal that takes into account the knowledge and goals of both members and citizens. This chapter also offers a specific and bounded definition for what counts as a disadvantaged group, and presents a nuanced categorization scheme within this classification based on how deserving of government assistance a group is perceived to be. After laying this definitional foundation, I then offer a broader theory explaining when and why members of Congress make the choice to foster a reputation as a disadvantaged-group advocate. This theory introduces the concept of the advocacy window as a means of understanding the constraints a member of Congress faces when making these representational decisions, as well as how different types of members respond to these constrictions. The chapter concludes by discussing the important differences between the House and the Senate, and their implications for when and why legislators working within these institutions choose to build reputations as advocates for the disadvantaged.

2.1 Prior Literature

A fundamental, perennial pursuit for political scientists has been determining the extent to which our political institutions are representative of the people. Particularly for an institution like the US Congress, designed to be a representative body that is responsive to the needs and desires of constituents, it is of great interest to know whether it lives up to that intended purpose. For many decades, political scientists and theorists have been focused on unlocking the true nature of the relationship between representative and represented, and attempting to elucidate the most important connecting threads. This exploration has focused principally on the answers to three questions. First, who is it that is being represented? Second, what are the means by which representation happens? Third and finally, what is the quality of the representation provided?

2.1.1 Defining Constituency

There is a long history of work evaluating the dyadic relationship that exists between members of Congress and their constituents (Reference MintaMiller and Stokes, 1963; Reference Cnudde and McCroneCnudde and McCrone, 1966; Reference FirthFiorina, 1974; Reference LawlessKuklinski and Elling, 1977; Reference Erikson and WrightErikson, 1978; Reference MilerMcCrone and Kuklinski, 1979; Reference Weissman, Pratt, Miller and ParkerWeissberg, 1979; Erikson and Wright, 1980; Reference Canes-Wrone, Brady and CoganCanes-Wrone et al., 2002). The object behind all of these projects is to determine the extent to which a member’s ideology or legislative actions align with the interests and opinions of the entire geographic constituency. But, more often than not, members tend to envision their constituency not as one cohesive entity, but rather parcel it out into smaller constituencies of interest. Richard Fenno, in Home Style, finds that the majority of the members of Congress he follows tend to describe their constituencies in terms of the smaller groups that make them up. He states that “House members describe their district’s internal makeup using political science’s most familiar demographic and political variables: socioeconomic structure, ideology, ethnicity, residential patterns, religion, partisanship, stability, diversity, etc. Every congressman, in his mind’s eye, sees his geographic constituency in terms of some of these variables” (p. 2). More recent research confirms that members of Congress see their districts in terms of subconstituencies, and emphasizes that the critical factor in understanding congressional representation is which of these smaller components of a constituency are being recognized and attended to (Reference BishinBishin, 2009; Reference MilerMiler, 2010).

Given the crucial role that groups and group membership play in politics and political understanding, this subconstituency focus is not surprising. A plurality of the electorate root both their party identification (Reference Griffin and NewmanGreen et al., 2002) and their broader political understandings in terms of group identities (Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and StokesCampbell et al., 1960; Reference Converse and ApterConverse, 1964; Reference ConoverConover, 1984; Reference RappPopkin, 1991; Reference MacDorman and MathewsLewis-Beck et al., 2008). Recognizing this, it would make sense that members of Congress also base their representational strategies around the groups in their district to whom they must appeal for their own reelection. Previous scholars seeking to evaluate the impact of constituent groups upon member behavior have acknowledged this, but they have tended to evaluate groups in isolation, be it nonvoters (Reference Griffin and NewmanGriffin and Newman, 2005), primary voters (Reference Brady, Han and PopeBrady, Han, and Pope, 2007), African Americans and Latinos (Reference Griffin, Newman and WolbrechtGriffin and Newman, 2008), or the poor (Reference BartelsBartels, 2008). Rather than looking at one single group, this project examines a larger category of groups – those that are at a systematic disadvantage in society. By expanding beyond the study of a single group, this project is able to present a general theory for when and why members of Congress choose to serve as advocates for disadvantaged groups more broadly.

2.1.2 What Does It Mean To Be Represented?

The next critical aspect of research into relationships between a member of Congress and their constituents focuses on the means by which representation occurs. This question has motivated a large number of studies. Each of these studies puts forward some concept of relevant constituent issues or beliefs and some measure of member actions or positions relevant to those issues or beliefs. Identifying the interests of constituent groups is challenging, with most previous studies taking one of two approaches. The first approach is to use aggregated survey responses to questions about specific policy or ideological preferences. Policy preferences tend to be determined either by questions that ask about the relative levels of spending that are preferred or by questions that describe a bill that came up for a vote in Congress and then ask whether the survey respondent would have liked their representative to have voted yes or no (Reference Alvarez and GronkeAlvarez and Gronke, 1996; Reference Wright, Erikson and McIverWilson and Gronke, 2000; Reference Hutchings, McClerking and CharlesHutchings, 2003; Reference Clinton and TessinClinton and Tessin, 2007; Reference Ansolabehere and JonesAnsolabehere and Jones, 2010). Those that use ideological preferences rely on measures asking respondents to self-identify their own ideological position on a seven-point Likert scale from very conservative to very liberal (Reference SulkinStimson, MacKuen, and Erikson, 1995; Reference StimsonStimson, 1999, Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson2003; Reference Griffin and NewmanGriffin and Newman, 2005). The second approach is to make assumptions about what policies would be in the best interests of the group, given the primary challenges that the group tends to face (Reference Uslaner and BrownThomas, 1994; Reference Bratton and HaynieBratton and Haynie, 1999; Reference RileyReingold, 2000; Reference SwersSwers, 2002, Reference Szaflarski and Bauldry2013; Reference Bratton, Haynie and ReingoldBratton et al., 2006; Reference BurdenBurden, 2007; Reference CarnesCarnes, 2013).

Each of these methods has advantages and disadvantages. Using survey responses alleviates the pressures of having to make assumptions about what is in a constituency’s best interests, but it also asks a great deal of respondents in terms of political knowledge and awareness. A large number of studies, extending back to Campbell, Converse, Miller, and Stokes’ The American Voter (Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960), highlight the degree to which the average American struggles to think in ideological terms, while others emphasize the low levels of political sophistication displayed (Reference Converse and ApterConverse, 1964; Reference DodsonDelli Carpini and Keeter, 1996). The second method sidesteps these knowledge-related concerns, but it relies upon assumptions about what a particular group needs.

Predetermining from the top-down what is or is not in a group’s best interest is not inherently a bad thing from a research design perspective, if the goal is to reasonably reflect the means by which a member of Congress might go about determining group interests. While members of Congress do engage in some of their own internal polling, they are not able to do so on every issue, and their results are just as likely to be plagued by the information asymmetry present in external polling. Given the amount of time and effort put into getting to know their districts, it seems highly likely that members of Congress would trust their own instincts when it comes to group interests, and when uncertainty exists, consult with an interest group advocating on the group’s behalf. Because this project is rooted in member behavior and member assumptions, I allow members to set their own determination of what it means to represent a constituent group. This insures that each of the different iterations for how members may choose to represent a given group can be captured, without artificially restricting what “group interests” should be.

When it comes to the member behavior side of the equation, most studies evaluating the congruency between member actions and constituent preferences focus on roll call votes (Reference MintaMiller and Stokes, 1963; Wright, Erikson, and McIver, 1987; Reference BartelsBartels, 1991; Reference Clinton, Jackman and RiversClinton, Jackman, and Rivers, 2004; Reference Griffin and NewmanGriffin and Newman, 2005). These votes are unquestionably important, as they determine policy outputs – the laws that actually end up being passed and affecting people’s lives. But they also necessarily require collective action. A bill being passed cannot be attributed to the actions of a single representative responding to their constituents. Moreover, most bills never make it to this stage. The bills that are voted on for final passage are, in most cases, acceptable to the majority party and its leadership (Cox and McCubbins, 2007). Thus, to have a more complete picture of the ways in which a member of Congress can represent their constituents, actions further upstream in the policy-making process must be taken into account (Reference Schiller and BiancoSchiller, 1995; Reference CanonCanon, 1999; Reference Bratton and HaynieBratton and Haynie, 1999; Reference SwersSwers, 2002, Reference Szaflarski and Bauldry2013; Reference CarnesCarnes, 2013).

These behaviors, including bill sponsorship and cosponsorship, committee work, and speeches on the floor of the chamber, are particularly consequential for representation, because they are either actions that members can take entirely of their own volition or actions that require the cooperation of a limited number of colleagues. For example, any member can decide to sponsor whatever bill they so choose, regardless of what other members are doing. To cosponsor a bill, it is only required that one other member have proposed it first. Working on a bill in committee requires the consent of the committee chair, but the preferences of the broader chamber do not always need to be taken into account. Releasing a statement to the press or using social media, on the other hand, is something a member can choose to do without consulting any other members of Congress. Similarly, members have various opportunities to speak on the floor on topics of their choosing.

A recognition of the assortment of actions that members can take and the varying importance of each are crucial to developing a holistic picture of the means by which representation happens. That said, representation is by its very nature an interplay between elected officials and their constituents back home. Lawmakers are aware of the fact that their constituents are hardly watching their every move and will frequently have little to no idea about the day-to-day activities within the legislature. Knowing this, legislators must consciously work to develop an identity and a reputation that can penetrate down to the constituent level, even if most of their actions themselves remain unknown. Therefore, to really understand a member’s representational focus, one must examine the reputation that they craft and the group interests that are central to it.

Reputation is broadly considered to be important, and legislative scholars widely acknowledge that lawmakers strategically hone a reputation that is advantageous to them. However, there has not been an attempt to quantify reputation separate and apart from actions like voting, bill sponsorship, or constituent communication. These actions doubtless influence a member’s reputation but do not give the whole picture. Reputation is something that a lawmaker works at by engaging in certain behaviors and rhetoric, but it is through middlemen like the press that constituents actually get a sense of member reputation (Reference SchillerSchiller, 2000a, Reference Sellers2000b). This study departs from the trend of focusing on behavioral outputs alone, instead choosing to evaluate member reputations as filtered through a third-party source – allowing for member reputations to be evaluated through the use of a medium that reflects the primary means by which constituents gain information about their member of Congress. Chapter 3 is devoted to providing a detailed accounting of precisely what a legislative reputation is, explaining why members concentrate their energy upon cultivating these reputations, and demonstrating how many legislators actually have reputations as disadvantaged-group advocates across both chambers of Congress.

Previous work has examined the effort that members put in to being perceived as effective lawmakers (Frantzich, 1979; Reference FiorinaFenno, 1991; Reference Schiller and BiancoSchiller, 1995; Reference Volden and WisemanVolden and Wiseman, 2012, Reference Warshaw and Rodden2018), and how well that effort is reflected in their reputations as members who can get things done. However, as highlighted earlier, to be effective in the legislature – to actually move legislation through the chamber and pass it – is necessarily a collective act. Therefore, a member’s individual reputation must be more than just effectiveness; it is also based in the groups on whose behalf they focus their efforts. Not all efforts, of course, are created equal. Thus, to truly understand the representation a member offers, one must recognize which group a member is working on behalf of, as well as the extent of those efforts, particularly relative to their other work within the legislature. Though not done through the explicit lens of legislative reputation, a number of studies have sought to address this third component of the representational equation: What is the quality of representation provided, and how does this vary across important group divisions in American society?

2.1.3 Inequalities in Representation

The next piece that must be determined, then, is who reaps most of the benefits from the representational efforts of members of Congress. To a large degree, the same groups that are advantaged in American society broadly are also more likely to see their interests and preferences reflected in the acts of their members of Congress. White Americans (Reference Griffin, Newman and WolbrechtGriffin and Newman, 2008), men (Reference Grossman and HopkinsGriffin, Newman, and Wolbrecht, 2012), and the wealthy (Reference BartelsBartels, 2008; Reference Glassman and WilhelmGilens, 2012; Reference Miller and StokesMiler, 2018) are far more likely to see legislators working on their behalf. While it is well established that disadvantaged groups in society, such as the poor, racial and ethnic minorities, and women,Footnote 1 tend to receive less attention to their interests, there is a noticeable void in the literature when it comes to examining the instances in which disadvantaged groups do receive representation, and the conditions under which members of Congress choose to act as their advocates.

An exception to this literature gap are the studies in which researchers have investigated the advantages (or disadvantages) of increasing the number of representatives who are themselves members of a disadvantaged group. In most cases, this work focuses on female (Reference DoviDolan, 1997; Reference SwersSwers, 2002, Reference Szaflarski and Bauldry2013; Reference Lax and PhillipsLawless, 2004; Reference DolanDodson, 2006); African American (Reference CanonCanon, 1999; Reference Gay and TateGamble, 2007; Minta, 2009); Latino (Reference HutchingsHero and Tolbert, 1995; Reference BrattonBratton, 2006; Minta, 2009); blue-collar (Reference CarnesCarnes, 2013); or, more recently, lesbian, gay, or bisexual members of Congress (Reference Hamilton, Madison, Jay and GoldmanHaider-Markel, 2010).Footnote 2 Reference BurdenBurden (2007) demonstrates that personal experiences can impact and shape legislative priorities. Descriptive representation scholars, in turn, argue that the experience of being a part of a disadvantaged group – which includes confronting systemic barriers in society that those outside of the group have not faced – provides a unique perspective that is unlikely to be matched by a representative who has not shared a similar experience (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 1998; Reference MatthewsMansbridge, 1999; Reference DuncanDovi, 2002). What these scholars find is that descriptive representatives are more likely to try to get group interests on the legislative agenda (Reference CanonCanon, 1999; Reference SwersSwers, 2002, Reference Szaflarski and Bauldry2013; Reference BrattonBratton, 2006) and to raise group priorities in committee markup sessions (Reference SwersSwers, 2002), floor speeches (Reference CanonCanon, 1999; Reference SwersSwers, 2002; Reference Park, Gelman and BafumiOsborn and Mendez, 2010), and hearings (Reference EriksonEllis and Wilson, 2013) more often than other members.

2.2 Representing the Disadvantaged

This project develops a broader theory of when and why members of Congress choose to advocate for disadvantaged groups. This theory centers on the pivotal role that a group-centered legislative reputation plays in the representation that groups receive, and integrates the important and differential impacts of constituency effects, descriptive representation, and institutional differences within the House and the Senate. The sections that follow lay out a clear definition for what counts as a disadvantaged group and argue for the important distinctions among these groups in terms of how deserving of government assistance they are perceived to be. Then, I introduce the concept of the advocacy window as a means of understanding how group size and group affect within a state or district can drive the representational decisions that members make, and highlight how these effects are conditioned by perceptions of group deservingness. Finally, the chapter illustrates how the institutional differences between the House and the Senate can alter the calculus behind members’ reputational decision-making.

2.2.1 The Group-Centric Nature of Representation

Members of Congress put a great deal of effort into cultivating a political and legislative reputation as a senator or representative. This reputation is derived from focused actions that the individual takes within Congress and is reinforced through interactions with constituents and with the media. For some members, these reputations are built exclusively on policy, as with someone who is known for being an expert on health care or taxation. For select members, reputation is built on politics and strategy, as is often the case with members who hold positions in party leadership. For most others, reputation comes as an advocate for a constituent group, such as farmers, women, or organized labor. For many members, reputations are multifaceted and may contain more than one of these elements, though overarching priorities are often readily apparent. This project focuses on members who develop a reputation as a group advocate.

Groups and group affiliation are and have been a critical component of American political thinking. For decades, research has consistently shown that most Americans do not think in constrained ideological terms and instead make political decisions based upon group identities and group conflicts (Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and StokesCampbell et al., 1960; Reference Griffin and NewmanGreen et al., 2002; Reference MacDorman and MathewsLewis-Beck et al., 2008). Thus, it makes sense that members of Congress would seek to develop reputations based upon advocating for specific groups in society, as that is one of the primary ways in which individuals make political evaluations. Understanding how the formation of a reputation as a group advocate serves as one of the central means by which members of Congress are able to communicate their priorities back to their constituents can provide important insight into the representation of many groups in American society.

Although this conceptualization of members as conscious builders of reputations as group advocates has broad utility, this book is focused on the specific choice that members make to build reputations as advocates for disadvantaged groups. Reputation formation in the context of the representation disadvantaged groups receive is particularly consequential and worthy of further study. The very real challenges faced by members of disadvantaged groups, as laid out in Chapter 1, are undeniable. The government has repeatedly recognized that marginalized and disadvantaged groups face additional barriers relative to non-group members, and thus require additional protections. Given this, in the aggregate, it is intellectually and morally desirable that these groups are represented within the legislature, and that their needs are not ignored. But at the level of an individual member, the circumstances under which this representation would actually occur are much less clear.

2.2.2 The Crucial Puzzle behind Disadvantaged-Group Advocacy

Members of Congress do not have infinite time, and their constituents do not have an infinite capacity to process every detail of their work within the legislature. For this reason, all members must make choices about the groups on which they are going to focus the bulk of their attention. Most districts (and nearly all states) contain a vast assortment of constituent groups: small business owners, suburban families, racial/ethnic minorities, farmers, veterans, women, manufacturers, seniors, and a great many others. It is impossible for a single member to create a legislative reputation as an advocate for all of these groups. Thus, they must make explicit decisions about which groups to prioritize as a part of their reputation, frequently with an eye toward the greatest potential electoral benefit. It therefore seems intuitive that members’ best approach to winning elections would simply be to spend all of their time working on behalf of the largest and most popular groups in their district or state.

In practice, however, this is not a hard-and-fast rule. While large and popular groups – like the middle class – do receive a lot of attention (both rhetorical and substantive) from members of Congress, some members do sometimes choose to develop reputations as advocates for groups that are not necessarily the biggest or most well regarded within a state or a district. The select group of members who make the decision to incorporate disadvantaged-group advocacy into their legislative reputations tends to be a prime example of this dynamic at work. So what drives them to do this?

While it certainly has normative appeal for members of Congress to advocate on behalf of disadvantaged groups, why they would choose to do so has not been adequately explained. Again, in an ideal world, a legislator may very well want to equally represent all groups present in their district. But in reality, choices have to be made, particularly when some group interests are seen as being at odds with others. For this reason, the calculus around deciding to become an advocate for disadvantaged groups can become especially complicated. Because of the precarious position held by a number of disadvantaged groups in society, members must draw a balance between seeking to draw in voters who are themselves members of a disadvantaged group or who view that particular group sympathetically and those voters who look upon assisting these groups with dismay.

Some preliminary evidence of this important relationship between public opinion and constituency presence comes from Reference HawkesworthHansen and Treul, (2015). Though they focus solely on the representation of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) Americans, the authors make a new and important contribution to our understanding of group representation by showcasing the interplay between district opinion and group size on the quality of representation a group receives. They find that while the size of the LGB population in a district has a positive effect on the substantive representation (measured through bill sponsorship) the group receives, the impact of constituency size on symbolic representational actions (measured as caucus membership and position taking) is conditioned by public opinion on same-sex marriage. However, there are some idiosyncrasies to studying the LGB community that limit how broadly these findings can be applied. In particular, the LGB community is fairly unique among disadvantaged groups in having a single, uncomplicated policy – legalizing same-sex marriage – that has often been used as a proxy for opinions regarding the group itself.

This project expands upon these ideas in three important ways. First, I argue that it is not constituent feelings toward specific policies that matter most in reputation building, but rather the feelings toward the disadvantaged group more broadly. Given that most constituents have little specific knowledge of policy, the nuances between various policy proposals are likely to be lost. Thus, I make the case that the level of hostility or affinity toward a group within a district shapes whether or not serving that group’s interests are actively incorporated into a member’s reputation. Second, by using a member’s reputation as a group advocate as the measure of representation, I can more cohesively incorporate a variety of substantive and symbolic actions. Third, I examine a number of different disadvantaged groups that have varying levels of societal esteem, allowing for a generalized theory of how district opinion impacts the representation of disadvantaged groups.

2.2.3 Disadvantaged Groups in the United States

Disadvantaged groups are those groups that face additional societal barriers, particularly a history of discrimination. The groups I examine in this book are: (1) the poor, (2) women, (3) racial/ethnic minorities, (4) veterans, (5) the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community,Footnote 3 (6) seniors (Americans over age 65), (7) immigrants, and (8) Native Americans. Nearly all of these groups are members of particular classes afforded nondiscrimination protections by United States federal law.Footnote 4 The one group that is included in this project but excluded from federal nondiscrimination laws is the poor. However, though protections for people in poverty are not currently enshrined in federal law, many states, counties, and cities include statutes prohibiting discrimination on the basis of income level. The presence of these nondiscrimination protections at the state and local level, as well as the challenges facing those in poverty with regard to food security, safe housing, quality education and adequate healthcare merit the inclusion of the poor within the category of “disadvantaged groups.” Altogether, this provides a clear case for why each of these groups are included under the banner of “disadvantaged,” as the purpose of these federal and state laws is to offer legal protection to groups that are at risk of receiving unequal treatment by non-group members.

This is not to say that all disadvantaged groups are the same, or even that all members of the group are disadvantaged to an equivalent degree. In no way does this project make the claim that, for example, veterans are as equally disadvantaged in American society as racial and ethnic minorities, nor does it attempt to create a hierarchy of disadvantage, which would be impossible (particularly given that these group identities are not exclusive to one another). Rather, the use of the term disadvantaged makes the assumption that an average group member faces a higher degree of systemic challenges than the average non-group member. Disadvantaged groups, then, are a broad category that implies that as a result of the group trait, additional barriers to success in American society are in place that are not present for non-group members.

The inclusion of veterans as a disadvantaged group, for instance, is an important example of this. Veterans may be frequently venerated at ballparks and Veterans’ Day parades, but still must navigate special obstacles to integrating back into civilian life and finding appropriate employment when compared to the average American who did not serve in the military. They also face higher instances of physical disabilities and mental health conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, which can place additional barriers on their path to success relative to non-veterans. Again, this acknowledgement that veterans can be subjected to these additional societal barriers is not to paint with a single broad brush and declare that all hardship is created exactly equal. Not all veterans deal with the same challenges, and even their treatment by society at large has not remained constant over the course of the last three-quarters of a century. Service members returning from World War II received a different kind of welcome from those who returned home from the Vietnam War, which is yet different from those coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan.

The other groups analyzed in this project also exhibit varying degrees of heterogeneity both within and across groups when it comes to the form of additional societal barriers they face. But in all cases, it remains true that the average member of a disadvantaged group must overcome challenges that the average American who is not a member of that disadvantaged group need not address. The primary concerns of a middle-class Black family in suburban Atlanta may be quite different from those of a single, young, Black man in Indianapolis. But nonetheless, each must still combat additional barriers stemming from racial discrimination and the vestiges of centuries of systemic segregation that do not negatively impact white Americans in a comparable way. As another example, a married woman with children may not feel the impacts of the gender wage gap as strongly as a single woman with children, but neither is immune from the negative consequences of gendered expectations or sexism.

In sum, people belonging to each of these groups (seniors, veterans, racial/ethnic minorities, LGBTQ individuals, immigrants, Native Americans, women, and the poor) face challenges above and beyond those faced by non-group members that serve to put them at a disadvantage relative to other members of American society. The federal government (or in some cases, state and local government), in recognition of these disadvantaged positions, offers unique protections to members of these groups. In doing so, they acknowledge the need for the government to intervene to at least some degree on their behalf to provide them with a more equivalent opportunity to be successful in American society. But, while the presence of some form of relevant disadvantage is consistent across all of these groups, as discussed in the preceding paragraphs, the exact nature and intensity of the barriers facing these groups can vary widely. The next section explores the extent to which these groups face different levels of receptivity from the public at large regarding the government’s assisting them in overcoming the barriers they face, and the impact that this perceived deservingness can have on the representation group members receive.

2.2.4 Perceived Deservingness of Government Assistance

Not all disadvantaged groups in the United States are held in the same level of esteem. Among the groups examined here, there are clear differences in how different groups are perceived, and in the extent to which they are broadly considered to be deserving or undeserving of government assistance by the public at large. This section lays out a categorization scheme based upon how deserving of government assistance a disadvantaged group is generally considered to be. These disadvantaged groups fall into three broad categories: groups with a high level of perceived deservingness of government assistance, groups with a low level of perceived deservingness of government assistance, and groups for which the perceived level of deservingness is more mixed.

These perceived categories of groups are rooted in broader societal beliefs regarding the extent to which a group has sacrificed and thus earned assistance from the government, or whether the group is perceived as seeking something extra from the government. Veterans who have trained and/or fought on behalf of the US are largely seen as being owed not just gratitude, but actual benefits in exchange for their service. Similarly, seniors are considered to be deserving of a government safety net as a reward for a lifetime as a hard-working American taxpayer.

At the same time, resentment and lack of willingness to acknowledge historic (and current) discrimination also play into these impressions, particularly for groups that are less favorably regarded. Discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities and corresponding feelings of racial resentment among white Americans in both political parties results in a context where a considerable portion of US citizens consider further government assistance to these groups to be undeserved and unnecessary. Despite the considerable increase in the support for equal treatment of LGBTQ individuals in the last few years, they are still regarded with suspicion or animosity by a significant percentage of the country.Footnote 5 This was even truer in the 2000s, when the cultural wedge issue of the 2004 election was a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage.

For other groups, such as women, immigrants, Native Americans, and the poor, the public’s sense of deservingness is more mixed. Feelings toward the poor are pulled by the competing values of providing equal opportunity (this is particularly true for programs serving poor families and children) and lionizing the power of hard work. These dynamics were front and center in the debate over changes to the Medicaid program in the proposed Republican health-care bill during the summer of 2017, where some members made the case for protecting the most vulnerable, while others argued that poor life choices were the cause of health problems. Similarly, opinions about immigrants revolve around both the positive personal connections to being a “nation of immigrants” and the fears of demographic change in the US. Competing views about government assistance for women are present in the dual popularity of “girl power” initiatives and concerns that men are in fact being disadvantaged or treated unfairly. Finally, going back to the nation’s founding, a fictionalized version of Native Americans has held a venerated place as an important symbol in American culture, while the actual suffering of native people has consistently been ignored or attributed to personal failing.

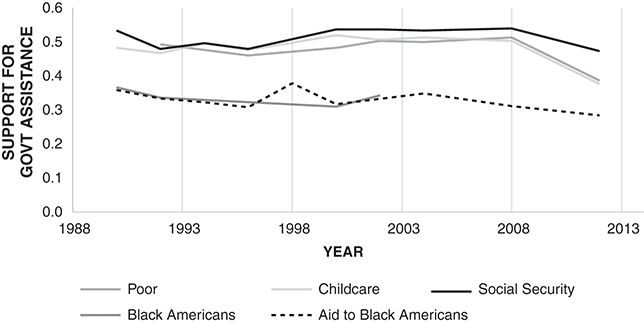

Support for this broad categorization scheme can be seen in Figure 2.1. Though there is no survey data available that directly asks about how deserving of government assistance each of these disadvantaged groups is perceived to be, this figure shows a close approximate for at least one of the groups in each of the three deservingness categories. Figure 2.1 utilizes the American National Election Study (ANES) time series data to show the varying levels of support for increasing government funding for the poor, blacks,Footnote 6 childcare, and Social Security. For the purposes of this example, support for additional government funding for childcare is taken as a rough proxy for government assistance for women, while support for additional Social Security funds are taken as a proxy for government assistance for seniors. Spending on the poor and Black Americans (as well as questions asking about government aid to blacks without specifying spending levels) are a more straightforward approximate of support for the government doing more to help these groups, with Black Americans operating as a proxy for racial/ethnic minorities more broadly.

Figure 2.1 Average national support for increases in government spending For the Poor, Childcare, Social Security, and Black Americans, 1990–2012.

Note: Figure shows the average level of support by year for increasing government spending on behalf of the poor, blacks, childcare, and social security. Also included in the figure is the average level of support for the government doing more to help Black Americans (as opposed to Black Americans being left to help themselves). This measure follows almost exactly the same trajectory as the level of support for increased funding for Blacks, but was asked in a greater number of years. All data come from the American National Election Study’s time series data, and is weighted to be nationally representative.

As seen in Figure 2.1, support for government assistance to Black Americans is consistently lower than the other groups evaluated. This is in accordance with the expectation that racial/ethnic minorities will mostly be seen by the general public as less deserving of government assistance. Government support for seniors, seen through the proxy of support for increased government funding for Social Security, is consistently at the highest levels of perceived deservingness of government assistance. This demonstrates that classifying seniors as being generally seen as worthy of government help is appropriate based on the data available. Women and the poor, however, both see levels of support that fall somewhere between that for racial/ethnic minorities on one end and seniors on the other.

Categorizing these groups on the basis of their perceived deservingness of government assistance offers important insight into how public opinion about a group can affect the quality of representation that group members receive. These broad, national-level feelings about different disadvantaged groups’ deservingness of government help are important because they shape the environment in which representatives make decisions about which groups to incorporate into their legislative reputations. Groups that are generally considered to be less deserving of assistance represent a riskier selection for a member of Congress, especially compared to those groups that are considered to be highly deserving of help from the government, because their constituents are more likely to angered by their representative expending so much energy on behalf of a group that has not “earned” it.

In the next section, I use this categorization scheme to offer important insight into the quality of reputation that a group will receive, and the ways in which public opinion can condition the impact of group presence within a state or district. Specifically, I introduce the concept of the advocacy window to explain how the average level of positive or negative feelings in a state or district toward a group can condition the effects of the size of the disadvantaged group within the constituency, and discuss the specific hypotheses that can be derived from this theory. I also discuss how the advocacy window is expected to work differently for disadvantaged groups with varying levels of perceived deservingness of government assistance.

2.3 Representation and the Advocacy Window

Broadly speaking, the size of a group within a district should increase the likelihood that a representative will choose to include advocacy on behalf of that group as an important component of their legislative reputation. I will refer to this as the group size hypothesis. Members must be strategic in their choices about which groups on whose behalf to advocate. Thus, having a larger group presence in a state or district (and thus a greater potential electoral benefit to offering visible representation of this group) should make a member much more likely to prominently include this group in their legislative reputation than a member representing an area with a small group presence.

Similarly, as feelings toward a group within a state or district – the ambient temperature – become warmer, members should also be more likely to incorporate group advocacy into their reputation. This, I will subsequently call the ambient temperature hypothesis. Though there is expected variation in the effects of ambient temperature based on how deserving of government assistance a group is perceived to be, on average, reputations for group advocacy should be more common in states or districts with higher ambient temperatures than lower ambient temperatures. For a closer look at the nuanced ways in which group size and ambient temperature can interact with one another to drive the choices members make about which groups to advocate for, I next introduce and explain the concept of the advocacy window.

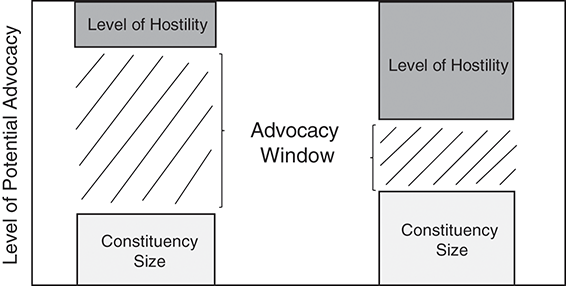

2.3.1 The Advocacy Window

The advocacy window is a means by which to conceptualize the amount of discretion that a representative is able to exercise in terms of how much of their reputation they wish to devote to a particular disadvantaged group, once group size and ambient temperature are taken into account. The percentage of group members in a district or state essentially acts as a floor, where members of Congress are expected to provide at least that much representation (which, below a certain point, is unlikely to influence the reputation that member chooses to cultivate). Public opinion regarding a group in a district, however, acts as a ceiling – if the group is well regarded, there are no limits to the amount of effort that could acceptably be put in on behalf of group members, but if the group is poorly regarded, the level of advocacy that would be accepted without putting the member in electoral danger is tamped down. Figure 2.2 demonstrates this relationship.

Figure 2.2 The advocacy window

Note: This figure demonstrates the conceptualization of the advocacy window. The advocacy window can be understood as the degree of latitude that a member of Congress has to incorporate group advocacy into their legislative reputation without suffering clear electoral damage once the size of the group within a district have been taken into account.

The space in between the floor and the ceiling is what I am referring to as the advocacy window. The advocacy window is essentially the potential amount of acceptable, additional work that a member can do on behalf of a disadvantaged group, if they so choose, without damaging their chances electorally.Footnote 7 If the level of public disdain for a group is low, then even if the constituency group within a district is small, a member of Congress would still have a great deal of discretion over the degree to which they integrate group advocacy into their legislative reputation. But if public disdain for a group is high, the advocacy window is likely to be small, even if the constituent group within a district is moderately sized. This theoretical framework is in line with the empirical findings of Reference JacobsonHutchings, McClerking, and Charles (2004), indicating that the impact of Black constituency size on congressional support varies across areas with high levels of racial tension.

While this analogy holds for the vast majority of cases, there are instances in which group size can actually exceed the ambient temperature within a district. Much like a house in which the roof has collapsed, members in these districts find themselves in a treacherous space without a perfect solution. I expect that in these rare cases, the damned-if-they-do, damned-if-they-don’t nature of the district environment will result in other factors such as member characteristics or partisanship taking precedence.

2.3.2 Perceived Deservingness of Assistance and the Advocacy Window

To this point, this chapter has highlighted both the district/state specific ambient temperature toward a group as well as a broader, more national sense of how deserving of government assistance a group is perceived to be as each having an important impact on the representation a group receives. While these two elements may be related to one another, it is important to note that these are in fact distinct concepts. Regardless of the group being evaluated, there is going to be some variation from district to district when it comes to the ambient temperature toward this group.Footnote 8 These changes are what are captured by the ceiling of the advocacy window. The broader conceptions of the deservingness of a group when it comes to government assistance, on the other hand, are a shaping force across all districts. These more general categorizations essentially describe the risk environment, and help to dictate how a member will respond to the advocacy window they face within their district.

Groups that are somewhat universally considered to be deserving, like military veterans or seniors, will find more ready advocates within the legislature, with variations in ambient temperature having less impact on constituency size effects. This is not to say that having more members of this group does not increase the likelihood of a member being an advocate, but that smaller numbers and changes are required for that to happen. For a disadvantaged group widely considered to be deserving, there may exist a potential boost to a member of Congress who firmly integrates providing for the group’s needs into their legislative reputation. For example, constituents may be more likely to support a member who focuses on serving the needs of veterans, because they consider it to be a worthwhile use of government time and effort, even if they are not veterans themselves. Because of this potential boost, being a descriptive representative should be less necessary for a member to formulate a reputation as an advocate.

For groups where the sense of deservingness of government assistance is more mixed or party dependent, such as immigrants or the poor, I expect that constituent group size would have a large impact on whether or not a member becomes an advocate,Footnote 9 but that this effect would be minimally mitigated by its interaction with district ambient temperature regarding that constituent group. Unlike with those groups deemed widely deserving, if feelings toward a group are fairly mixed or of a more neutral variety, I would expect that the group’s presence within a district or state would be the driving factor behind advocacy. Given the more neutral level of public regard, where advocacy is not seen as a clear electoral positive or negative, I expect that a member’s party or experiences as a descriptive representative will be a large contributor to a member cultivating a reputation as a group advocate.

In the final category, for groups that are considered to be markedly less deserving of assistance, I expect that ambient temperature toward the group puts in place a large barrier to advocacy that is only cleared when a very large percentage of group members are present within a district. If public regard for a group is low, then members advocating for this group will receive no electoral boost or additional benefit from individuals who do not belong to the group. In fact, if a disadvantaged group is actively disliked, advocating for that group’s needs could even backfire on a member so as to reduce the electoral support they might otherwise have received.

2.3.3 Party Effects

A key theoretical expectation for this project is that this reputation building on the part of disadvantaged groups should not be the exclusive purview of members of only one political party. Both Democrats and Republicans will have at least some disadvantaged group members in their states and districts, and thus some level of representation is expected. Reputations for group advocacy are also not bound by particular means that may be sought to address the challenges facing disadvantaged groups, but rather by the act of seeking to address those needs in and of itself. This means that policy strategies preferred by Republicans and those preferred by Democrats each could be used in service to building a reputation as a disadvantaged-group advocate.

However, while potential reputations for disadvantaged-group advocacy are not explicitly tied to one party or another, there are some reputations that may be more common among one party than another. This is particularly true when considering advocacy on behalf of Black Americans. As Katherine Tate explains in her book Concordance, since the 1970s, the needs of Black Americans have gradually moved from being the primary focus of sometimes radical advocates within the Congressional Black Caucus to being firmly within the mainstream agenda of the Democratic Party. Given these changes over time, I expect that reputations for the advocacy of racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to be found among Democrats than Republicans.

2.3.4 Descriptive Representatives

In all cases, I expect that being a descriptive representative of the group is a factor that will make a representative more likely to foster a reputation as an advocate for that group. I expect, however, that this effect will be the most readily apparent for members who represent a district with a large advocacy window. Given that a descriptive representative’s knowledge and affinity for the group tends to exceed that of non-group members, I anticipate that they will more likely aim for the ceiling when facing a broad advocacy window and base their reputation in advocacy for that marginalized group. In accordance with Reference MatthewsMansbridge’s (1999) predictions about when descriptive representation should be most important, a member’s own personal experience with discrimination or marginalization will make them more likely to risk any negative consequences that come from being a group advocate. Thus, given this potential risk, descriptive representatives should be more likely to take advantage of an expanded advocacy window to cultivate a reputation as an advocate.

2.4 Legislative Reputations in the House and the Senate

Given the institutional distinctions between the House and the Senate, there should be some differences in how members make decisions about which groups to include in their legislative reputations. Members of the House are considered to be specialists, at least compared to senators. Being a part of a 435-member body means that members are prone to develop narrow legislative identities and address very specific issues, groups, and policies. House districts also tend to be more homogeneous than those of the Senate (though this is not true in all cases).Footnote 10 This means that House districts are more likely to be spaces in which members of disadvantaged groups are concentrated. Coming from a more homogeneous district also minimizes the likelihood that advocating for one group in particular will provoke conflict. For these reasons, I expect that members of the House are more likely to formulate a reputation around being an advocate for a marginalized group than a member of the Senate, and that they will devote a larger portion of that reputation to advocating for the group.

In the Senate, members have far more freedom to be entrepreneurial in their legislative approach. Not only do they serve on more committees than House members, it is not unusual for senators to propose legislation outside of their specific committee-driven areas of expertise. The ability to offer non-germane amendments to legislation assists in this. Because members of the Senate tend to be generalists, this gives them a lot more latitude in the groups that they choose to represent. As a result, senators have a high level of discretion to hone their legislative reputation strategically, which provides incentives to incorporate as many “safe” groups into their legislative reputations as possible. Therefore, it is expected that Senators will more likely opt for a more superficial form of group advocacy, rather than devoting a large share of their energies toward working on behalf of any particular group.

For a large portion of American history, political theorists regarded the Senate as the protector of minority groups against the popular majorities in the South. Those assumptions that minority interests are somehow linked with the interests of smaller states, however, are highly problematic, particularly where racial/ethnic minorities are concerned (Reference Delli Carpini and KeeterDahl, 1956; Reference LeighleyLee and Oppenheimer, 1999; Reference Lewis-Beck, Jacoby, Norpoth and WeisbergLeighley, 2001). Compared to the House, senators are more likely to be running scared – the electoral margins tend to be smaller for senators, and their seats more competitive. So, there also are more risks for senators in developing a reputation as an advocate for an unpopular group, especially if the group’s members are not sufficiently numerous to compensate for any losses to the senators’ electoral coalition that might result from that advocacy. Given this, I hypothesize that the increased electoral vulnerability of most senators relative to most members of the House will make senators less likely to become advocates of disadvantaged groups in general, and that this will be particularly acute for groups who are not considered to be broadly deserving of government assistance, such as racial/ethnic minorities.

2.5 Conclusion

This chapter reviewed the ways that previous research has understood the representational relationship, and offered a more realistic conceptualization of representation that takes into account the type of information that members of Congress and their constituents could actually be expected to know. It presented a new, integrated theory of when and why members choose to represent the groups that they do, with a special focus on disadvantaged groups. In doing so, it recognizes that not all members of disadvantaged groups are considered to be equally deserving of assistance from the government by society at large, and that those different categorizations of deservingness have an impact on which members of Congress are willing to develop a reputation as a group’s advocate.

Each state or district has an advocacy window, which represents the degree of latitude that a member of Congress has in making decisions about how extensively to incorporate disadvantaged-group advocacy into their legislative reputations. After the size of a group within a district or state is taken into account, members rely upon their own discretion to determine the level of group representation to offer, which is conditioned by the ambient temperature toward a group within that state or district. For all but those disadvantaged groups that are held to be the most highly deserving of assistance, such as seniors and veterans, cross-state or district variations in how favorably the rest of the district feels toward a group is expected to have a conditioning effect on how likely it is that a member will choose to include advocacy on behalf of that group into their legislative reputation. This should be most acutely felt for disadvantaged groups such as the LGBTQ community or racial/ethnic minorities that are viewed as less sympathetic by broad swathes of the American public.

The next chapter examines the critical role that legislative reputations play in the ways that groups are represented in Congress. It makes a case for legislative reputation as one of the primary conduits of representation, and offers a clear definition and operationalization for what legislative reputations are, as well as what they are not. Finally, it demonstrates the incidence of members with legislative reputations for serving the disadvantaged across a sampling of Congresses. It highlights the variation in the primacy of each group to a member’s reputation, and showcases the partisan and House-Senate differences in the types of reputations members form.