Tokens form one of the many media of everyday life through which overlapping identities were created, consolidated and performed. An individual possessed multiple identities throughout their life course; someone might have identified with a particular group or been classified into a particular category by others. A person in the Roman world might possess overlapping identities related to class, geographic region, work, gender, family, the military, cult, communal associations, or another type of community. One or more of these identities might come to the fore at different moments in a person’s life – a sense of belonging to a particular group, after all, is actively constructed and contested over time.Footnote 1

Rather than seeing ‘identity’ as a static concept to analyse, sociologists have suggested that instead we might examine the processes through which identities are (or are not) enacted. This focus on process offers a fruitful path to best capture the lived experience of particular individuals. Brubaker advocated an approach he termed ‘Groupness’, the study of moments of intense solidarity and cohesion amongst a particular group of people. These events might fail in enacting identity, but even if successful remain only a passing moment in time: the solidarity or cohesion felt during a particular occasion may not endure once the event is over.Footnote 2 A focus on the processes of group-making uncovers the mechanisms by which, and events in which, identities might become salient – that is, the situation in which a particular identity is invoked or performed.Footnote 3

If we are correct in seeing tokens as objects used for particular moments in time, then they form an ideal source to begin reconstructing ‘Groupness’ – the way in which feelings of cohesion and community might manifest during a particular occasion. Throughout an event different identities might be activated (i.e. become salient). Indeed, many tokens seem to have been designed in a way to call forth particular identities in the user, through the use of imagery and language designed to speak to participants (e.g. representations of worshippers of different types, the presence of chants). Such strategies may reflect an implicit understanding on behalf of token makers that ‘Groupness’ might fail – material culture was thus employed to actively facilitate feelings of community and cohesion.

Events and their associated material culture played an important role in the creation and performance of different identities.Footnote 4 The connection of artefacts to identity in the Roman world has already received significant attention within scholarship; many of the coins of the Roman provinces, for example, are now understood as elite expressions of civic identity particular to a local region.Footnote 5 But among the voluminous outputs on the topic of ancient identities, the role of tokens in this process, and the types of identities these artefacts reveal, has not featured at all. This chapter begins to address this lacuna by exploring what tokens can reveal about the differing identities of individuals in Italy, and the processes by which these identities might be activated at particular moments in time.

The designs of tokens from across the Roman Empire reveal that they could form a vehicle for the expression of different types of identity: civic, tribal, cultic or individual identity, for example. A series of Gallo-Roman lead tokens carry direct reference to settlements or tribes, including the settlement of Ricciaco (modern day Dalheim-Pëtzel), the Alisienses, Ambiani and Lingones.Footnote 6 Tokens in Egypt might also carry city names accompanied by imagery of local significance: tokens of Memphis, for example, carry imagery connected to the main cult in the region, the Apis bull, and those from Oxyrhynchus represent the local cult of Athena-Thoeris.Footnote 7 A lead token found in Tunisia carries the legend GENIO TVSDRITANORV, a reference to the Genius or embodiment of the people of Thysdrus.Footnote 8 Tokens from Roman Athens carry imagery intended to enhance the prestige of the issuers, with imagery perhaps consciously chosen to underline the divine ancestry or familial standing of the individuals concerned.Footnote 9 Among the imagery found on lead tokens from Ephesus are a bee, a stag and the famous cult statue of Artemis of Ephesus, images that were also found on the provincial coinage of the city and were emblems of civic identity.Footnote 10 The use of tokens to activate and/or consolidate different identities in Italy explored here is thus part of a broader phenomenon.

Tokens form an important corpus of material from which to uncover everyday expressions of identities within Rome and Italy.Footnote 11 Importantly, their decentralised production means that they offer glimpses into the experiences of individuals who are not necessarily well represented in our surviving textual evidence: women or collegia for example. The imagery and legends selected for tokens used in hyperlocal contexts reveal the ways in which everyday material culture was marshalled for ‘Groupness’, those moments in which particular identities might be made salient. This chapter begins with a consideration of what tokens can reveal about civic identities in both Rome and Ostia, before moving on to consider the display of other identities (those formed through work, family, or office-holding, for example). As Rebillard notes, an individual might experience multiple identities, which might be activated simultaneously or successively.Footnote 12 The multiplicity of different types of identities expressed on tokens offers the historian an insight into the plural nature of identity for individuals in Roman antiquity.

The City of Rome

Several lead tokens reference the Genius populi Romani, the divine personification of the people of Rome. This figure had previously appeared on coinage of the Republic to emphasise the sovereignty and agency of the Roman people; the Genius is variously shown as a youthful male portrait accompanied by a sceptre, holding a cornucopia and crowning Roma with a wreath, or holding a cornucopia and sceptre and being crowned by Victory.Footnote 13 The figure of the youthful male carrying a cornucopia continued into the imperial period. The Genius was an important focal point of identity, both for Rome’s inhabitants and for provincial representations of Roman power.Footnote 14 In addition to the youthful male Genius, the embodiment of the Roman people was also communicated via the medium of text. Remarkably, several Roman tokens carry nothing but text, referring to the Genius populi Romani via an abbreviated Latin legend: G P, G P R or G P R F, with the last F acting as an abbreviation of the phrase feliciter (well wishes).Footnote 15 Figure 3.1 bears the abbreviation GPR on one side with the word feliciter spelt out in full on the other. The use of feliciter recalls the tokens discussed in Chapter 2, which express good wishes for the emperor. Similar to those pieces, these tokens are likely artefacts created as part of a larger event or festival.

Figure 3.1 Pb token, 14 mm, 12 h, 2.57 g. GPR / FELICITER around.

The legend G·P·R had earlier accompanied a representation of the Genius of the Roman people on the coinage of the Republic.Footnote 16 The letters G P R F also appear as a stamp on Roman lamps, and appear on marble inscriptions in Rome and Ostia – this particular combination of letters was evidently well used and recognised.Footnote 17 The ways in which this abbreviated phrase might form part of daily life can be found in a painted inscription (titulus pictus) in the insula Vitaliana on the Esquiline hill in Rome.Footnote 18 The inscription, the only evidence for the name of this particular insula, is placed within a tabula ansata in a room that is decorated with black and white mosaic pavement and which dates to the second century AD. The inscription is a dedication by the officinator of the insula P. Tullius Febus, with G P R F placed on the dovetails of the tabula ansata (G P on left, R F on right). Beneath the inscription a large coiled snake (perhaps a representation of the genius loci) was painted facing right; the inscription and snake sit within a broader painted decorative scheme in the room that involves floral and fruit garlands, and a rooster.Footnote 19 Without further information it is difficult to know the precise use of this room, but it contains an expression of civic identity in a very local context, perhaps juxtaposed against the Genius of the locality in the form of a snake. As well as the image of the youthful male Genius, one can argue that the identity of the Roman people was also shaped by three or four letters: the G P R or G P R F repeated in numerous contexts throughout the city. Glancing at these letters in an insula, on a lamp or on a token would have reinforced to the viewer their location within the broader community of Rome. Such everyday encounters (which Billig called ‘banal nationalism’), reminding individuals of their place within a particular group, was an important process in maintaining identity.Footnote 20

At times the textual representation of the Genius of the Roman people on tokens is playfully combined with a figurative form. On one token type the Genius is shown holding a patera and cornucopia. On the other side of the token this representation is clarified as P(opuli) R(omani); the token might then be read in its entirety as Genius (represented as a figure) P(opuli) R(omani).Footnote 21 On other tokens both the figurative and textual reference to the Genius of the Roman People are present; these combinations may have served to further underline the meaning of the letters G P R.Footnote 22 The embodiment of the Roman people was thus expressed through figurative or textual form. Other identities might also be expressed via abbreviated text, as explored throughout the rest of this chapter: through the use of abbreviated tria nomina, for example, or through abbreviated references to particular legions (e.g. LEG I, LEG II or L. II).Footnote 23

Among the types that appear on tokens in connection with the Genius of the Roman People are: Roma, Victory, Fortuna, Venus, Pietas sacrificing over an altar, a modius, a palm branch, numbers (IIII, XVI) and legends (e.g. PSO).Footnote 24 The representations of Venus and Fortuna are of particular interest given what we know of the cult to the Genius populi Romani in Rome. Cassius Dio mentions that a temple to the Genius populi Romani stood in the Roman forum.Footnote 25 The fasti fratrum Arvalium and the fasti Amiternini record that on 9 October sacrifices were made to the Genius publicus, Fausta Felicitas, and Venus Victrix on the Capitoline Hill.Footnote 26 Coarelli has suggested that three temples to these precise deities stood on the location of the so-called ‘Tabularium’, a complex planned by Sulla and completed by Q. Lutatius Catulus.Footnote 27 Coarelli further suggested that the well-known ‘Venus Pompeiana’ painting (showing Venus in an elephant quadriga with the Genius of Pompeii on her left and Fortuna with rudder and cornucopia on her right) might also reflect this Roman triad – the figure carrying a cornucopia and rudder, currently identified as Fortuna, may in fact be Felicitas according to this theory.

Although any conclusions must remain hypothetical given the state of the evidence, one token type might provide evidence to support Coarelli’s suggestion. One side carries the legend G P R F around in a circle, while the other shows a female figure standing holding a cornucopia and rudder accompanied by the legend FEL.Footnote 28 Rostovtzeff noted the abbreviated legend might refer to Fel(icitas) or Fel(ix). FEL might have been placed on the token to indicate that the figure shown is not Fortuna but Fausta Felicitas, who shared a day of celebration with the Genius of the Roman People. Another token shows a female figure holding a cornucopia and rudder standing left, accompanied by the legend FELICIT, which may communicate feliciter or name the figure as Felicitas.Footnote 29 These specimens lend further weight to Coarelli’s suggestion that the image of Fausta Felicitas was that of a female deity carrying a rudder and cornucopia.

Venus also appears on tokens in conjunction with the Genius populi Romani, but the form taken is that of Venus emerging from the bath with her hands raised to her hair. Venus Victrix, by contrast, normally appears accompanied by a helmet and shield, at least on numismatic representations.Footnote 30 The appearance of the goddess on these particular tokens, then, is unlikely to have been a representation of Venus Victrix. The representation of Venus Victrix with a helmet and spear does occur on a token. The other side of this token issue bears a goddess holding a cornucopia and a rudder; whether this is Fortuna or Fausta Felicitas is difficult to say.Footnote 31

Tokens thus formed a medium that carried representations of the embodiment of the Roman people (Genius), and which actively expressed well wishes for the inhabitants of the city. The cry of feliciter may also have served to evoke a response from the user, similar to the chants discussed in Chapter 2. One imagines these tokens were used during localised celebrations on 9 October or similar occasions: that the expression G P R F is found elsewhere in Rome reveals it was deployed in multiple contexts. The representation of the Genius populi Romani accompanied by legends consisting of three letters, likely to be abbreviated tria nomina or other abbreviated forms of names, suggests the creation of tokens of this kind by different individuals for different occasions.Footnote 32 The expression of the Genius of the Roman People on tokens, whether in figurative or textual form, would have contributed to an overall sense of community at a particular event. The sense of ‘belonging’ to the populace of Rome could be evoked and consolidated through particular moments that created a strong sense of cohesion (e.g. communal sacrifice), while the everyday materiality of Rome would have served to remind individuals of their identity on a daily basis.

Tokens conferred benefaction and privilege to particular individuals. Those with a token and access to what it represented formed an ‘in’ group, set in contrast to the ‘out’ group who possessed no token; the overall effect would have contributed to a sense of community within the ‘in’ group. The imagery placed on a token was likely inspected by users – this would have included those who held the privilege the token conferred, and the individual accepting the token in exchange for the benefaction it represented. The message on a token would thus have enhanced the experience of a particular event, its materiality acting upon users to enhance feelings of solidarity and belonging.

Tokens also show the goddess Roma and foundation myths associated with the city of Rome. Figure 3.2 shows Roma seated on one side, with the expression G P R F on the other, an indication of how expressions of good cheer for the Genius of the Roman People might encompass additional expressions of the city’s identity. A token of this type was amongst those found in the Tiber in Rome.Footnote 33 On TURS 1082 the Genius of the Roman People stands alongside Roma; the other side of the token bears the legend IAN|VAR, likely a reference to the month of January or Ianuarius. The she wolf and twins also occurs as a type paired with various other images, including the Ficus Ruminalis, the fig tree that reportedly stood at the Lupercal on the spot Romulus and Remus came ashore from the Tiber (Figure 3.3).Footnote 34 Aeneas, accompanied by Ascanius and Anchises, is represented on several tokens, as is the myth of Mars descending to Rhea Silvia.Footnote 35 Tokens thus formed a medium for the expression of foundation myths and other imagery associated with civic identity. In this way they possess similarities to provincial coinage and the official coinage of the Roman mint.Footnote 36 But unlike coins, these pieces were small in number and likely viewed by a limited audience. Unlike coinage, which contributes to a sense of community through repeated circulation over time, tokens served to enhance the experience and feeling of community associated with a particular moment in time.

Figure 3.2 Pb token, 19.5 mm, 12 h, 2.48 g. Roma seated right holding Victory in left hand and spear in right / G P R F around.

The Tiber, which snaked through the city of Rome and formed an important channel for the movement of goods and people, also appears on tokens. As with the major rivers of other cities, the Tiber formed a central component in the formation of identity in Rome; the personified deity of the river, Tiberinus, famously spoke to Aeneas in Virgil’s Aeneid, for example.Footnote 37 The river god also appears on Roman coinage, reclining and wearing a crown of reeds, variously accompanied by a prow, an urn from which water flows, and reeds.Footnote 38 The presence of the Tiber indicates a specific location on the saecular games coinage of Domitian and Septimius Severus (sacrifices took place during these games by the Tiber river).Footnote 39 The connection of the river to identity in Rome is perhaps best expressed on a coin series struck under Vespasian. The reverse of these coins shows Roma seated right on Rome’s seven hills, with Romulus and Remus suckling from the wolf below and the Tiber river reclining on lower right of the coin holding a long reed.Footnote 40 The colossal statue of the Tiber now in the Louvre shows the river reclining holding a rudder and cornucopia accompanied by the wolf and twins, underlying the connection between the river and Rome’s foundation.Footnote 41

The small number of tokens from Rome and Ostia showing river deities suggest the Tiber was conceptualised in multiple ways. One type shows a reclining river deity accompanied by the legend TIB, presumably a reference to the river Tiber or his personified form Tiberinus. The other side of the token shows the deities Fortuna and Mercury, perhaps an expression of the wealth and commerce the river brought to Rome.Footnote 42 The same legend (TIB) occurs on a token that carries on the other side what Rostovtzeff described as a Genius seated holding a patera and an urn from which water flows.Footnote 43 The combination of image and legend here suggests that what is represented is the Genius of the Tiber, or perhaps one of its outlets (an aqueduct or fountain). The urn with water flowing from it is an attribute of rivers and springs, but the addition of a patera and the lack of reeds here suggest it is a Genius who is shown rather than Tiberinus.Footnote 44 This same Genius, holding a patera and an urn that spills water, is also found on a token with a branch or tree on the other side; on this specimen the Genius appears to also have a modius on his head.Footnote 45 In yet another representation, the Genius is shown holding two corn-ears (or perhaps it is a V) and the urn, with the legend M | DM on the other side.Footnote 46 This representation of the Genius of the Tiber (or one of its offshoots) appears to be unique to tokens among surviving material culture. The modius and corn-ears may reference the role of the Tiber in facilitating the supply of grain to Rome.

Iconographic innovation can be found on another token type, which shows a male figure draped from the waist down, holding a cornucopia and reed, with his left foot on a rock (Figure 3.4). One imagines that this also is a representation of the Tiber or one of its outlets, but unusually the figure is shown standing rather than reclining. As noted above, Tiberinus might be portrayed with a variety of attributes, but these occurrences all show the deity reclining. The standing representation of the river might have referenced a now lost statue; the Nile is frequently portrayed standing on coins of Alexandria and one imagines this variation must have existed for the Tiber as well.Footnote 47 This particular image may have been more resonant than a reclining Tiberinus for the community using the tokens; it might have referenced a very particular statue and/or location within Rome as opposed to the Tiber more generally. Just as particular attributes served to make Graeco-Roman deities ‘local’ (e.g. the addition of the labrys to Athena on tokens at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt), so too might the alterations to the representation of the Tiber we find on material culture in Rome represent hyperlocal iterations of the river in the city.Footnote 48 The meaning of the legend on this token issue remains a mystery.

Figure 3.4 Pb token, 20 mm, 9 h, 3.9 g. River deity, draped from the waist down, standing right with left foot on rock holding a long reed in his right hand and cornucopia in left; CGA on left and FT on right / VES between two palms or branches.

A river god, most likely the Tiber, appears in yet another iconographic iteration on Figure 3.5.Footnote 49 Here the deity reclines on an urn, with a reed curving up and around him, and a dolphin swims beneath. A more worn token that seems to belong to the same series shows the river god with a reed curving up around him on either side (no legend), and Victory accompanied by the legend V A.Footnote 50 This variation in design can be explained by the fact these tokens were made from moulds; this allowed for deviation within a particular series, as explained in Chapter 1. The addition of the dolphin to the scene is significant here, since the feature is not normally associated with rivers or the Tiber.

Figure 3.5 Pb token, 19 mm, 12 h, 2.43 g. River god reclining left, left arm leaning on urn from which water flows; reed on right curving above the god’s head, dolphin swimming right below. ARA around on left / Victory, standing left with wreath in extended right hand and palm branch in left. C on left, ligate VR on right.

This is evident from the series of coins struck under Nero showing the harbour at Ostia with a reclining deity placed at the bottom of the scene (Figure 3.6). This figure is identified in the RIC as the river Tiber holding a rudder and reclining on a dolphin. But the dolphin is more often used to reference the ocean. As a result, the reclining figure on Nero’s coinage has convincingly been re-identified as a personified representation of the harbour at Ostia.Footnote 51 Indeed, the representation of a similar figure on coinage of Pompeiopolis (Cilicia), reclining on a dolphin and holding a rudder as part of a harbour scene seems to confirm the identification. The relative rarity of the image and the fact that it appears in reference to these two distinct harbours suggests, as Boyce argued, that this is a particular deity associated with a place where rivers flowed into the ocean.Footnote 52 Indeed, if the dolphin had a specific association with seafaring in Ostia, then its use on tokens that show sailing vessels on the other side may have been intended as a specific reference to the fact that these were ocean-going vessels.Footnote 53

Figure 3.6 AE sestertius, c. 35 mm, 6 h, 27.69 g. Laureate head of Nero right, with aegis on neck, NERO CLAVD CAESAR AVG GER P M TR P IMP P P around / View of the harbour at Ostia, AVGVSTI above, POR OST beneath flanked by S C. RIC I2 Nero 178.

To return to the token shown in Figure 3.5, the presence of the urn and reeds indicate that it is a river god shown here. But the presence of the dolphin alludes to the fact that the river, which we might interpret as the Tiber, is connected to the ocean, evoking Rome’s harbour in the mind of the user. The token, issued by a curator (CVR), again utilised an inventive (and an otherwise unknown) combination of imagery to evoke a particular vision of the Tiber that emphasised the connection of Rome to her harbour and the ocean that ensured her supplies. The multiple representations of the Tiber on tokens likely reflects the fact that these tokens were created by a variety of individuals, representing particular groups who each may have possessed a slightly different vision of the river so central to their city. In this sense the Tiber can be viewed as a ‘shared image’, the meaning of which was extended by different users. When different groups widened the semantic meaning and associations of the Tiber, the image of the river became a powerful community-building tool that was able to engage a variety of people, all of whom connected with the image, even if each held different associations.Footnote 54 The multiplicity and malleability of representations of the Tiber show how images can be deployed to engage a broader variety of individuals than a single static, carefully controlled image.

We also find much more localised expressions of identity. At least three tokens appear to carry direct references to the regions of Rome: regio III, VI and XIII.Footnote 55 Augustus had divided the city into fourteen regions (regiones) and numerous neighbourhoods (vici) also existed; each region and vicus received annually elected magistrates.Footnote 56 In spite of the regional divisions being imposed from the ‘top down’, so to speak, the repeated reference to particular regions in inscriptions, including tokens, suggest that Romans nonetheless identified with their region, and might act communally within this grouping, at times in conjunction with other regiones in the city.Footnote 57 Individuals also formed social bonds within their neighbourhood or vicus, and we find expressions of identity at this level on tokens. One token carries the legend VICI accompanied by the figure of a Genius. The type must, as Rostovtzeff surmised, represent the Genius of the neighbourhood (Figure 3.7). The vici served as focal points for communal activity within Rome, particularly among the lower classes and during the Compitalia held in honour of the lares placed at the crossroads, as well as in connection with the worship of the imperial family.Footnote 58 The material expression of these communities can be found in the shrines (compita) and altars erected in these locations, as well as on other items of everyday life, like the tokens presented here.Footnote 59 The presence of snakes on several token series also hints at representations of local shrines and locations, since snakes might represent the Genius of a place and are represented in association with the altars of lares on other media (for example the fresco of the Lararium at VII.6.3 in Pompeii).Footnote 60

Figure 3.7 Pb token, 13 mm, 12 h, 1.36 g. Genius standing left holding cornucopia in left hand and patera in right, VICI around on right / Hercules standing left holding club in right hand and lion skin over left.

Tokens also express more informal formulations of local areas. The regionary catalogues of late antiquity name each region of Rome in relation to a specific feature of the area, for example Regio XI Circus Maximus. Since no earlier sources survive for such naming conventions it is unclear whether this practice was created during the compilation of these texts, or whether the catalogues recorded existing, unofficial, terminology.Footnote 61 The third region of Rome was labelled Isis et Serapis in the catalogues, after the temple (and street) in the region. In this context a lead token carrying the legend AB | ISE ET | SERAP is of interest – it likely refers to the street leading away from the temple of Isis and Sarapis that gave the third region its name.Footnote 62 The other side of the token shows the god Harpocrates with his hand raised to his mouth; the combination reveals an expression of very local identity shaped by the topography of the city. Indications of location are found on other epigraphic monuments in Rome; for example a cippus from region VII records the location ad tres silanos, presumably referencing three fountains within the area.Footnote 63 Suetonius records that Domitian was born at the street called the Pomegranate in the sixth region.Footnote 64 Rome was full of such local names, and associated local communities.

These local expressions of identity can be found on several other tokens. Several express a location in relation to Mars: one carries the legend REG MAR (regio Martis?), another carries the legend AD MART and another A MART. These tokens all carry imagery of the god Mars as well; the phrase ad Martis refers to the area surrounding the temple to Mars in Rome on the via Appia between the first and second milestones from the Porta Capena.Footnote 65 One wonders whether the representation of Mars on the tokens, leaning on a spear with one hand and resting his other hand on a shield at his feet, represents the cult statue within this temple.Footnote 66 A token also records the location ad nucem. Here the meaning of the legend is further elaborated by the representation of a nut next to the legend and a nut tree on the other side.Footnote 67 Pallacina also appears on tokens, although whether the legend PALLACIN refers to the vicus or the bathing establishment in that district is open to debate.Footnote 68 A particular location and associated identity might also be represented via imagery alone. Figure 3.8, with a recorded findspot of Rome, shows three statues of Fortuna standing side by side, a likely reference to the location ad tres Fortunas.

Figure 3.8 Pb token, 15 mm, 6 h, 1.92 g. Three Fortunae standing left, each holding a cornucopia in their left hand and a rudder in their right / A left hand with thumb and index finger touching; SAT on left, A or uncertain object (prow?) on right.

The temple of the three Fortunae was located on the Quirinal, close to the Porta Collina, and Vitruvius records that the area was named ad tres Fortunas after the temple.Footnote 69 The hand shown on the other side of the token is reminiscent of cameos and gems that show a hand pinching an ear as an embodiment of memory.Footnote 70 But here there is no ear, and so a more likely explanation is that the hand represents the number ten. The so-called ‘finger calculus’ is known from antiquity and the middle ages. A series of bone and ivory gaming pieces reveal that the Romans counted on their fingers in a manner that was preserved into the middle ages, but which was different from the method used in contemporary Western society.Footnote 71 These gaming pieces carry the finger sign on one side and the corresponding number inscribed in Latin on the other; the number ten is represented by a left hand with the thumb and index finger touching with the remaining three fingers extended, as on Figure 3.8. The token thus uses imagery alone to communicate two phrases: ad tres Fortunas and X.

The legend to the left of the hand reveals a possible context for the token: the Saturnalia. The chant associated with this festival, io Saturnalia io, was abbreviated to IO SAT IO on tokens, and is discussed more fully in Chapter 4. One possible context for the objects discussed in this section is revealed: these tokens may have been used during very local events held in the context of broader festivals across the city. These events were occasions that sought to activate the identity of particular neighbourhoods and regions, and the iconography chosen for tokens played a role in this process. Alongside a broader sense of ‘belonging to Rome’, inhabitants of the city also belonged to communities arranged by smaller neighbourhoods or streets. Overlapping identities connected to different types of community within the city meant that, depending on the occasion, an individual might emphasise their membership in one community over another at a particular moment in time.

Maritime Identity in Ostia and Portus

The tokens found at Ostia also reveal overlapping identities. The nature of civic and local identity in Ostia has, surprisingly, not seen the same level of analysis as other regions of the Roman Empire. As Bruun observes, this may be because Ostia lacks an obvious corpus of sources for such a study. Ostia’s close relationship with Rome has also led to the port town being treated as a suburb of the capital.Footnote 72 Rome was important in the construction of Ostian identity: Ostia was the first colonia of Rome, reportedly founded by Rome’s fourth king Ancus Marcius.Footnote 73 But Ostia’s role as a key port also shaped civic identity, a sense of ‘Ostianness’. Bruun has observed the ‘maritime mentality’ of Ostia’s inhabitants, witnessed in epigraphic evidence and material culture: Bruun notes here the imagery of boats, lighthouses, anchors, tridents, dolphins and other aquatic divinities and animals in mosaics, sarcophagi, graffiti, lamps and tokens across the town.Footnote 74 In fact, the evidence for a sense of ‘Ostianness’ is rich when one begins to examine the remains of the town more closely. The tokens found in Ostia and referencing the settlement have had only a minor role in discussions of Ostia’s civic identity, but they are a powerful corpus of evidence from which to uncover the different communities and identities in the town.

References to Ostia in material culture frequently depict the harbour’s lighthouse, and it is unsurprising to find this represented on tokens as well. The lighthouse appears in several mosaics in Ostia, as well as in marble reliefs, graffiti, a wall painting and on imperial coinage referring to the grain supply.Footnote 75 On tokens the lighthouse is paired with a variety of legends and imagery that name the port and allude to the maritime nature of the settlement. Figure 3.9, for example, shows a lit lighthouse of three tiers with the letters P T; Rostovtzeff convincingly suggested this should be understood as P(ortus) T(raianus) (although we might resolve the legend as Portus Traiani). The other side of the token shows Neptune in a hippocamp biga, a reference to the ocean. The lighthouse and the legend suggest that Ostian civic identity must have incorporated the harbour, initially built under Claudius and then enlarged under Trajan, when it became known as the Portus Traiani.Footnote 76

Figure 3.9 Pb token, 14×12 mm, 3 h, 3.07 g. Lit lighthouse of three tiers, P on left, T on right / Neptune, holding trident in right hand, riding right in a biga of hippocamps; star above.

A lighthouse of three tiers also appears on a token with the other side carrying the retrograde legend TR|AI.Footnote 77 The lighthouse, at times accompanied by the legend TI S, is paired with a seated Fortuna in one series (Figure 3.10; the meaning of the legend is unknown).Footnote 78 The image of the lighthouse is also accompanied by the legend ANT, which Rostovtzteff suggested might refer to portus Antoniniani.Footnote 79 One token displays the lighthouse on one side and a ship sailing on the other.Footnote 80 A specimen now preserved in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Palestrina pairs the lighthouse with a semi-circular object with a handle (?) on the other side.Footnote 81 Another type, found in the Terme sulla Semita dei Cippi in Ostia, shows a three-tiered lighthouse on one side and a nude figure standing frontally on the other.Footnote 82 The representation of the lighthouse at Portus on material culture at Ostia varies in terms of the number of storeys and other features (e.g. in the Piazzale delle Corporazioni it is variously shown with three, four, five or six storeys, or only the top of the lighthouse is represented). On tokens, however, the representation seems quite standardised: of the known representations to date, each has three or four (Figure 3.10) storeys.

Figure 3.10 Pb token, 24 mm, 12 h, 5.69 g. Lit lighthouse of four tiers, TI on left, S on right / Fortuna seated left holding cornucopia in left hand and rudder in right.

Tokens showing the lighthouse and Fortuna have reported findspots in several locations in Ostia. An example of the variant with the legend TI S (Figure 3.10) was found during the excavations of a taberna in the Baths of Neptune, with another specimen found in the Terme di Serapide, and a third in the Terme bizantine.Footnote 83 Another of the same type possibly came from the excavation fill outside the ruins of the city, and yet a further possible example, too worn for precise identification, was found in the Basilica Portuense at Portus in a late antique context.Footnote 84 Three of these finds come from bath contexts, as does the find from the Terme sulla Semita dei Cippi mentioned above. The bath contexts may simply reflect the fact that money (and tokens) are frequently lost down drains in these buildings. Significantly, however, the finds reveal that the same type of token was carried by individuals into different bathing establishments across Ostia. If these tokens were to be redeemed for participation in an event or for a particular good, they were distributed in advance of the occasion.

Alternatively, these tokens may have been used within the economy of the bathhouse itself. As discussed in further detail in Chapter 5, there is good evidence to suggest that tokens were used within bathhouses in Rome and Ostia, likely as an internal accounting mechanism to be exchanged for food, drink or services. The existence of the same token type in multiple establishments may reflect the fact that tokens from one bathhouse may have been reused in another to cut down on manufacturing costs, or that a particular workshop may have manufactured the same type for multiple groups. Alternatively, the tokens with the lighthouse might have represented a civic level of benefaction – the granting of admission to bathing establishments across the town, although the precise findspots of these pieces suggest they were used and lost within the bathhouse rather than acting as an entry ticket. In any of these scenarios, the civic nature of the imagery chosen – a lighthouse and the goddess Fortuna – must have facilitated the acceptance of this particular token type. The imagery would be easily recognisable to the inhabitants of Ostia, and each user would find meaning in the type in a way not possible with a token naming a specific bathing establishment, for example, or a particular local organisation. Tokens in Roman Egypt also display this dual approach to imagery: the image of Nilus, for example, is found on tokens that travelled across the province, while other types possessed very specific imagery and are only found in one location (e.g. the representation of Athena-Theoris with labrys is only found on tokens at Oxyrhynchus).Footnote 85 The representation of the lighthouse within daily life (whatever the specific context) must have reinforced a particular maritime sense of ‘Ostianness’, also seen in the mosaics of the Piazzale delle Corporazioni and the other representations across the town.

Three tokens carrying an image of the lighthouse at Ostia were reported to Rostovtzeff by Gauckler as having been found in Hadrumetum in North Africa; two were specimens carrying the design of the ‘lighthouse / Fortuna seated’, and one was of the ‘lighthouse / ANT’ type.Footnote 86 The colony of Hadrumetum was an important source of grain for Rome and movement between the two port towns must have been regular, which would explain how the tokens ended up so far from their place of manufacture. The tokens might have been converted into a type of emergency small change, or else might have been carried by merchants as mementoes or items they intended to redeem at a later date. In this context it is worth noting that among the tokens preserved in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Palestrina there are five tokens from Egypt (Figure 3.11).Footnote 87 Since the collection was seized as the proceeds of illegal excavation activity, we cannot know the precise findspots of these items, but it is very likely these pieces were found in Italy. Indeed, the existence of migrants and merchants in Portus and Ostia is well established: the Isiac association of Portus, for example, seems to have been founded and dominated by individuals from Alexandria in Egypt.Footnote 88 Tokens rarely travelled between settlements, although there are several cases where tokens travelled (in small number) from one port to another, a reflection of the much broader exchange of people and goods that took place in these towns.Footnote 89 Stannard’s analysis of a series of quadrangular bronze tokens found at both Ostia and Minturnae has also demonstrated that tokens moved between ports within Italy; Stannard suggested these particular pieces were connected to the workings of the ports and connected river systems.Footnote 90

Figure 3.11 Pb token of Oxyrhynchus, 23 mm, 11 h, 13.70 g. Bust of Athena right wearing Corinthian helmet; linear border / Nike standing right on globe holding wreath in extended left hand and palm branch in right; linear border. cf. Milne 5291 for a token of the same type, found at Oxyrhynchus.

A civic identity closely tied to the maritime activity of Ostia is also indicated by other tokens that carry nautical imagery and variations on the legend Traianus. The legend may refer to the emperor Trajan, but the juxtaposition of the legend and maritime imagery suggests a reference to the Portus Traiani is more likely. Indeed, epigraphic evidence attests to the fact that the inhabitants of a quarter around Trajan’s port were known as Traianenses, ‘those of Trajan’.Footnote 91 The legend TRAIANI (‘of Trajan’) is also found on tokens accompanying imagery of Apollo and Fortuna.Footnote 92 The Latin might refer to the fact that the token was issued on behalf of Trajan, but it might equally refer to a group who identified with a particular area of Portus, or it might reference portus Traiani more broadly. The legend TRAIANVS was reported on a token now lost, which carried a tuna fish on one side and Neptune holding a dolphin and trident on the other, a likely reference to the port of the emperor.Footnote 93 A new type found amongst the collection now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Palestrina shows what appears to be an elephant on one side and the legend TRAIANAS on the other.Footnote 94 TURS 947, decorated with a ship (cydarum) on one side and the legend PT on the other may equally refer to Portus Traiani, as on Figure 3.9. Without recorded findspots for these token types we cannot know for certain whether they referred to particular groups within Ostia and Portus, but the evidence suggests that this is probable.

Tokens showing two or three people in a boat on one side and the legend TRA on the other are also known (Figure 3.12). The legend again might refer to some form of the word Traianus, but we cannot rule out an abbreviation of traiectus, a place where one could cross the river at Ostia via ferry; various groups provided this service. Without further find information it is difficult to say more; one token with the legend TRA on one side and three palm branches on the other was found in the Tiber in Rome.Footnote 95

Figure 3.12 Pb token, 24 mm, 6.12 g. Two people in a boat (cymba), fish beneath/ TRA.

Only one token type specifically names Ostia. Side a of this token shows a bare male head right, accompanied by the legend GAL AVG (a reference to Galba Augustus), while the other side shows Ceres seated holding a sceptre and corn-ears, accompanied by the legend OSTIAE.Footnote 96 The use of the genitive might indicate that this was a token of Ostia, but equally the token may be referencing grain that came from the port. The combination of Galba and Ceres, along with the reference to Ostia, brings to mind the massive Horrea Galbae, a large warehouse complex in Rome that served as a depot for grain and other goods, including the annona publica. The complex was probably first known as the Horrea Sulpicia, but was renamed after Galba (who was of the Sulpician gens) during his reign, when the complex came under imperial control.Footnote 97 Both Trajan and Galba oversaw activity that directly influenced the experience of Ostia’s mercantile inhabitants and which consequently shaped their everyday experience and identity. Whether this token series, and the TRA tokens discussed above, were issued by inhabitants of Ostia or on behalf of the emperor, their existence, and the activities that led to their creation, would have served to further a particular ‘Ostian’ sense of community.

Status and Self-Portrayal in Rome and Ostia

Many tokens from Rome and Ostia bear the name of individuals, both men and women, as well as references to particular gentes.Footnote 98 Figure 3.13, for example, bears the name M(arcus) Antonius Glaucus. Tokens of this kind not only expressed emotions and ideologies associated with a particular moment, but also reinforced the prestige of the individual responsible for the token and the benefaction it represented. In addition to carrying the names of individuals, tokens could carry portraits, or representations of paraphernalia associated with a person’s office or occupation. Several tokens carry types that are otherwise only found on gems, suggesting that the imagery of a person’s seal (or glass paste) might be used to reference a particular individual. In general, with a few exceptions, the individuals named on tokens are not otherwise known.Footnote 99 This is unsurprising: tokens generally appear to have been issued by lower magistracies in charge of games and distributions, as well as individuals involved in communal associations, bathhouses or other commercial establishments. The corpus of material thus provides an invaluable insight into individuals from the Roman world who are otherwise absent from the remaining historical record.

Figure 3.13 Pb token, 20 mm, 6 h, 4.26 g. M in the centre of the token, ANTONIVS GLAVCVS around / Vulcan standing left holding sceptre in left hand and mallet in right.

In fact, the full mass of individuals named on lead tokens may not have been fully recognised. Many tokens from Rome and Ostia carry legends of two or three letters; these may very well be abbreviated tria nomina (with two letters perhaps referring to women, for whom the praenomen was abandoned relatively early in Roman history).Footnote 100 Graffiti, amphora labels and personal stamps from the Roman world reveal that in circles where an individual was well known, initials might be used to represent a particular person. In Pompeii, for example, graffiti referred to individuals by their initials (e.g. LVP), as did campaign posters: one example of the latter on the Via dell’Abbondanza highlights the candidacy of one CIP.Footnote 101 This same practice is found in Ostia, where graffiti reveals that one LCF ‘was here’.Footnote 102 The combinations of two and three letter legends found on many tokens may thus have acted as a reference to the name of an individual; these tokens were likely used within a small community and a specific context, where the identity of the issuer would have been recognised. Indeed, two token types carry the legend LCF, the first accompanied by a camel on the other side and the second the legend LAM.Footnote 103 This is not to suggest that the LCF of the tokens and the graffito in Ostia are one and the same; rather the example demonstrates the practice of naming conventions within daily life. The surviving corpus of tokens may reference far more individuals than has previously been realised.

Tokens also carry the names and portraits of women. A series of tokens was issued by a woman called Hortensia Sperata: two tokens of 19–20 mm in diameter carry the legend HORTENSIA SPERATA or HORTE·SPER· around in a circle on one side. The other side of the tokens are decorated with a palm branch within a wreath. Smaller tokens (13–15 mm) have an abbreviated legend: HOR in a line on one side and SPE or SP on the other.Footnote 104 Hortensia may have required two different sizes of token (19–20 mm and 13–15 mm), with each size equating to a different good or value. The differing diameters of the tokens were further underscored by the use of different designs for each size. A token mould half found on the Esquiline Hill in Rome reveals that tokens of different sizes might be cast at the same time. This mould half had two sets of channels, for two sets of tokens: a 17 mm piece with the legend LVE and a 9 mm piece with the same legend ligate.Footnote 105 A Hortensia Sperata is known from a funerary inscription in Antium that she erected to Lucius Hortensius Asclepiades, but there is no reason to identify this woman with the token issuer.Footnote 106 The palm branch and wreath, also found on other tokens, evoke a festive feeling.

A Domitia Flora is also named on a token issue, as is an Aelia Septimi, Iulia Iust(a) and a Livia Meliti(ne), amongst others.Footnote 107 One token issue names Iunia, with the other side carrying the representation of a sistrum, perhaps referencing a context connected to Isis.Footnote 108 Other women may also be named, but in several cases it is impossible to distinguish between the name of a gens and that of a woman. A token with the legend APRO|NIA, for example, may refer to an individual woman or the gens of the same name; the representation of Fortuna on the other side of the token offers no clues as to which interpretation is correct.Footnote 109 Similarly the IVL|IA that appears on a token with the representation of a palm branch and corn-ear on the other side may reference an individual or a broader family.Footnote 110 Two token issues have the legend OP|PIA; the first carries an image of Fortuna on the other side, the second a female portrait. This may indeed be a representation of a woman named Oppia.Footnote 111 Given that women were generally known by the feminine form of their familial names, one imagines this slippage between a woman and her family was something experienced more broadly in the Roman world. Several tokens also bear female portraits without accompanying legends; one imagines these are representations of particular individuals. Figure 3.14, for example, shows a female portrait likely to be of the second century AD, since the hair is plaited and coiled on top of her head in the fashion of this era.Footnote 112 The absence of an identifying legend accompanying the portrait also echoes the trend of imperial tokens from the second century, in which emperors are shown but not named (discussed in more detail in Chapter 2). Women are also occasionally named on provincial coinage, either because they held eponymous offices, or in their capacity as priestesses; one imagines that both the coinage-issuing priestesses and the token-issuing women of Roman Italy were the sponsors of particular benefactions of varying value.Footnote 113

Figure 3.14 Pb token, 22 mm, 12 h, 8.09 g. Female bust right / B|VVPP.

Hemelrijk’s study of female patronage demonstrated that, like their male counterparts, women had reduced opportunity for the very prominent display of public benefaction in Rome because of the extensive influence and control of the imperial family; it was rather prosperous and densely populated towns outside of Rome that offered greater opportunity for visible participation in civic life and public commemoration.Footnote 114 Also like their male counterparts, women did partake of the civic life available to them in Rome, even if they were restricted in the types of public benefaction and commemoration available. Within this new landscape, both men and women performing an act of euergetism may have decided to underscore their munificence and prestige through the issuing of tokens, a small artefact that marked the occasion in a cityscape otherwise dominated by the imperial family.

Male portraits also appeared on tokens, and partnership between individuals was expressed. A token from the Tiber river, for example, carried a female portrait on one side accompanied by the legend CVRTIA FLACCI, with a male portrait accompanied by the legend FLACCVS on the other; one imagines a familial pairing is represented here.Footnote 115 Two individual men might also be named alongside each other, perhaps indicating a shared act of euergetism. This might take the form of both individuals being named on one side of the token (e.g. TURS 1495, with the legend SEVERI | ET | CRISPI), or a name given on each side of the token (e.g. TURS 1417, with the legend FLAC|CVS within a wreath on one side and GAL|LVS within a wreath on the other). Alternatively, both individuals may be named and provided with a portrait, as found on Figure 3.15.

Figure 3.15 Pb token, 18 mm, 12 h, 3.16 g. Male bust right, VERRES around / Male bust right, PROCVLVS around.

Male portraits might also appear without an identifying legend. Pairs of individual portraits (male-male or male-female) also appear on the same side of a token facing each other.Footnote 116 These tokens formed statements of connection between individuals. The representation of a portrait and legend naming an individual on a monetiform object closely resembles representations of the emperor on coinage; the phenomenon is also present on orichalcum tokens as shown and discussed in Figure 1.4.Footnote 117 In the same way that lower classes might use glass pastes to emulate the otherwise elite practice of gem wearing, so too tokens may have afforded the opportunity for individual Romans to present themselves in a manner similar to the emperor. The particular framework of representation, on an object that looked very similar to a coin, might have served to heighten the sense of prestige associated with the token and the benefaction it represented. Incidentally, the clear imitation of certain aspects of coinage clearly demonstrates the role this medium had in influencing the identities and mentalities of those who lived in the Roman Empire.

Full body representations of individuals are also found. Figure 1.8, for example, was issued by one Marcus Valerius Etruscus, son of Marcus. Rostovtzeff identified the figure on the token as Mercury, but he does not carry a caduceus and is wearing a toga; the representation may then be of Etruscus himself carrying a purse, a visual manifestation of the munificence the token represents. The entire image recalls a togate statue, and this elite medium may have been an intentional reference adopted here to communicate status.

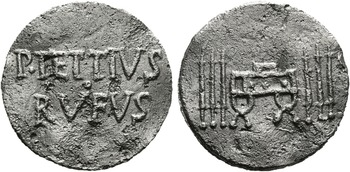

Several token types specifically reference the office of the token issuer, a practice that served to emphasise the status of the individual. One example is that issued by Publius Tettius Rufus, whose token series displayed a curule chair flanked by fasces (Figure 3.16).Footnote 118 Rostovtzeff identified this individual with the Tettius Rufus who was praetor in the first century AD; he further compared the token with a coin series struck by Livineus Regulus in the late Republic (Figure 3.17).Footnote 119 Crawford believed that this coin type, and others struck by Regulus showing a beast fight and modius with corn-ears, referred to the curule office of two of Regulus’ ancestors and the activities they performed as aediles.Footnote 120 The parallel with Republican coinage is instructive, particularly on a token that likely dates to the first century AD. Moneyers in the Roman Republic utilised coinage as vehicles to communicate familial history and prestige; towards the end of the Republic coinage was also frequently utilised to communicate contemporary ideologies.Footnote 121 Under Augustus individual references to moneyers and their familial history gradually disappeared from Roman coinage, part of the broader movement towards the control of public monuments by the emperor.Footnote 122 But although references to moneyers disappear from Roman coinage, we still find references to office holding elites on tokens. During the imperial period these artefacts were able to operate in a communicative manner similar to the coinage of the Republic, albeit on a much reduced scale.

Figure 3.16 Pb token, 22 mm, 12 h, 2.78 g. P·TETTIVS | RVFVS / Curule chair with three fasces on either side.

Figure 3.17 AR denarius, 4 h, 4.02 g, 42 BC. Bare head of Regulus right, REGVLVS PR. Border of dots / Curule chair with three fasces on either side, L·LIVINEIVS above, REGVLVS below.

A variety of offices, both civic and religious, are referenced on lead tokens. Another representation of a curule chair flanked by three fasces appears on the token of one Herenn(ius) Ruf(us) who names himself as curator.Footnote 123 The curule chair also appears on a token with a male portrait on the other side, presumably the office holder and token issuer.Footnote 124 A lituus, the emblem of an augur, appears on a token of M CAV|C·LF, which Rostovtzeff noted likely referred to a Marcus Caucidius or Caucilius, son of Lucius.Footnote 125 The lituus also appears on a token with the legend PCI, and another with SA, perhaps the initials of individuals, as well as on other types.Footnote 126 That an individual might reference their religious office while issuing a token is demonstrated by one T. Cornelius Paetus, whose tokens name him as both pontifex and curator (the other side carries the portrait of Tiberius and the legend TI AVGVSTVS).Footnote 127 Priestly offices are also referenced by the apex, worn by pontifices, flamines and salii.Footnote 128 One token carries an apex on one side and the legend PPS on the other, the three letters perhaps an abbreviated tria nomina.Footnote 129 An apex also appears on a token with what Rostovtzeff reported was perhaps a priestly attendant on the other side; another appears next to a palm branch on a token that bears Victory inscribing a shield on a column on the other side.Footnote 130 A token of this last type was recovered from the Tiber in Rome in the nineteenth century, while a mould half for making tokens decorated with a lituus has been found at Ostia.Footnote 131

But while some tokens referenced particular offices, many more tokens naming individuals carried imagery connected to prosperity. Fortuna, Mercury and Victory, for example, are found on numerous specimens.Footnote 132 These same expressions of luck are found on Roman wall paintings; a shop in Pompeii on the street of Mercury, for example, had painted in the doorway an image of Mercury and Fortuna facing each other, a double statement of luck.Footnote 133 The choice of deities that evoked prosperity on tokens may be connected to their use context (e.g. festivals or feasting), or these may be the tokens of individuals who had not managed to hold an office.

The moneyers of the Roman Republic had also used visual puns to communicate their names, images called ‘canting types’ in numismatics. The moneyer Lucius Aquillius Florus, for example, placed a flower on some of the coins issued under his authority, while the moneyer Quintus Pomponeius Musa placed images of the muses on his coinage.Footnote 134 This visual expression of a name (and hence a personal identity) is also found on other media in the Roman world: Pliny records that the architects of the porticus Octaviae, having been denied the right to be commemorated in an inscription, signed their names on a column with the image of a lizard (saura in ancient Greek) and a frog (batrachos), visual puns on their names Saura and Batrachus.Footnote 135 The remains of a bronze bench from the Forum of the Baths in Pompeii included legs shaped like a calf’s legs, accompanied by the inscription M. NIGIDIVS VACCVLA P.S (a vaccula in Latin was a young cow, the P.S. is to be understood as p(ecunia) s(ua), ‘at his own expense’).Footnote 136 Tombstones also carried such references: representations of mice were at times placed on the tombstones of individuals with the name Mus, and one Tiberius Octavius Diadumenianus was referenced on his tombstone through a representation of Polykleitos’ Diadoumenos statue (‘diadem bearer’).Footnote 137

It is thus unsurprising to find canting types on tokens of the imperial period. The token of a Publius Glitius Gallus displays the name and portrait of Gallus on one side and a rooster carrying a wreath and palm branch on the other (gallus was Latin for rooster) (Figure 3.18). Rostovtzeff believed this was the Gallus named in the conspiracy of Piso, but another Publius Glitius Gallus is also known from the first century AD; equally this may be a third, otherwise unknown, individual.Footnote 138 A token with the legend AQ|VIL on one side and an eagle (in Latin aquila) on the other is also a further probable canting type.Footnote 139 One P. Asellius Fortunatus issued a token with a representation of Fortuna on one side and a star and crescent on the other.Footnote 140 A calf was also depicted on a token accompanied by the legend VITLA, which Rostovtzeff interpreted as the name Vit(u)la.Footnote 141

Figure 3.18 Pb token, 19 mm, 12 h, 2.66 g. Male head right, P GLITI GALLI around / Rooster standing right holding a wreath and palm branch.

There may be many more instances of visual punning that we can no longer recognise: if a calf or a mouse appears on a token without an accompanying name, we cannot know if the image served as a visual pun on the name of an individual. The (possible) use of visual puns without accompanying legends might have occurred because the meaning would have been self-evident to the user, who knew the name of the token issuer. The use of such puns may have been designed to bring a smile to the face of the user (particularly in the case of the wreath-toting rooster), or to further emphasise the individual responsible for the particular benefaction.

Moneyers in the Roman Republic could select coin types that reflected the prestige and achievements of their gens. Tokens presumably offered a similar communicative opportunity. And yet there seem little, if any, token types connected to familial history. There may be several reasons for this divergence. In spite of their similar physical appearance, coins and tokens may have been conceived of very differently in the Roman world: while Republican coinage was linked to Juno Moneta and Roman memory, tokens may have had different associations, and hence attracted a different type of design.Footnote 142 There may also have been a shift in self-presentation in the imperial period. In the Republic moneyers, at the beginning of their careers, were limited to representations of ancestral achievement. But under the principate, which focused on the achievements of a living individual, elite self-representation shifted. Augustus and his successors presented themselves as models of patronage to be imitated; instead of civil war or military conflict, elite competition and display focused upon public benefaction. Those who participated in such activity also widened, with an increased number of equestrians and decurions undertaking these activities.Footnote 143 The position of token issuers, who may have been participating in an act of euergetism for a particular group, was very different to that of moneyers in the Republic, and this context may have resulted in a preference to emphasise the individual rather than the historical achievements of a gens.

Several token types are very close or identical to the designs found on gems and glass pastes. These objects were often incorporated into signet rings and used as seals, forming a visual representation of a particular person. Worn on the body, the objects (and their imagery) were personal markers of status and identity.Footnote 144 Many of the designs on tokens, gems and glass pastes are drawn from a broader repertoire of imagery within the Roman world: from political and elite images, from imagery considered to have protective properties, the imagery of deities, of the circus, and of objects encountered in daily life.Footnote 145 In his exploration of the practice of everyday life, de Certeau examined the effect individuals have on their environments. By adopting and manipulating the elite culture around them, he argued that people might make this ‘language’ their own. What is not chosen in this context is as significant as what is chosen.Footnote 146 Viewed from this perspective, the selection of particular elite images for use in a non-elite context (whether on a glass paste, or a token issued by someone outside the elite) are powerful acts that transform imagery, making it significant to the identity of an individual or group.Footnote 147 But the frequency with which other, non-elite, imagery is chosen (e.g. allusions to chariot racing, Fortuna, or mice) should also be kept in mind. Although some individuals chose to represent themselves via particular elite imagery, others, it seems, found other representations more meaningful in this context.

Given the parallels in imagery between gems and tokens we cannot rule out the idea that some designs on tokens may have been intended to replicate the issuer’s intaglio stamp, which would have been used in other contexts and recognised within a certain circle as representative of a particular individual. Indeed, tokens and seals that carried the signet ring design of a particular individual might be viewed as ‘media of the body’ in that they acted to extend the presence of a particular person in time and space.Footnote 148 In Roman Athens, tokens were often countermarked with particular designs (e.g. ‘stork and lizard’ and ‘dolphin’) thought to reflect particular issuers.Footnote 149 Alternatively, similar to glass pastes, tokens may have formed an accessible medium for those outside the elite to display the types of imagery seen on more expensive media. The image of an ant seen from above (at times carrying a seed), for example, is known on tokens, gems and glass pastes.Footnote 150 On tokens the ant is paired with legends that might be names (e.g. LAR on TURS 455), imperial imagery (e.g. a Capricorn, TURS 488), as well as more obvious references to individual and familial identity (e.g. the legend AVRELIAE on TURS 1141). These different iterations of the same image (ant), combined with different imagery and legends, reflect the process of appropriation that took place in the Roman world, as a language of images was manipulated to express particular identities.

Some tokens carried fantastical and humorous imagery, which is also found on gems. The image of an elephant emerging from a shell, for example, is found on both media (Figure 3.19).Footnote 151 On the image reproduced here the design is paired with Victory; an elephant emerging from a shell is also paired with a phoenix and appears on the lead tokens of Ephesus.Footnote 152 A token in Berlin appears to show a rhinoceros emerging from a shell, with the legend SPE on the other side – various animals emerging from shells served as a popular motif for gems.Footnote 153 The gryllus or caricature is also found on tokens, consisting of a creature with the head of a horse, legs of a rooster and a body made up of a mask of Silenus and a ram’s head (Figure 3.20). The same image is also known from gems.Footnote 154 These fantastical representations fall into the same category as other comical and absurd imagery, for example mice in chariots. Although the humour of these representations might have appealed to the owners of these pieces, the imagery also had the potential to serve an apotropaic function.Footnote 155 The imagery chosen for intaglios and tokens therefore might simultaneously communicate a particular identity and protect the individual concerned. These images may also have expressed a desire for prosperity, similar to the imagery of Fortuna and Mercury mentioned above.Footnote 156

Figure 3.19 Pb token, 18 mm, 12 h, 3.28 g. Victory standing right with wreath in right hand and palm branch in left / Head of an elephant emerging from a shell right.

Figure 3.20 Pb token, 19 mm, 12 h, 5.73 g. Helmeted bust right of Roma or Minerva right / Fantastic creature with the head of a horse, legs of a rooster, mask of Silenus on the right side, and a ram’s head on the left; sceptre behind.

Identity might also be communicated through language. Although the overwhelming majority of tokens from Italy bear legends in Latin, several token series are in Greek. These might carry references to individuals or a gens: the ΙΟΥΛ on TURS 1250 is likely a reference to a Julius, or the Julian clan. The design of this token is linked to the cult of Asclepius through the representation of the head of the deity and his serpent-entwined staff. Another token bears the legend ΔΙΟ|ΓΕΝ, a probable reference to a Diogenes (Fortuna is shown on the other side).Footnote 157 Figure 3.21 shows a bare male head facing right, accompanied by the legend CWC|IOY on the other side. Rostovtzeff identified this as the Gaius Sosius who originally served as a general of Marc Antony before defecting to Octavian and who was responsible for the temple of Apollo Sosianus in Rome.Footnote 158 The style of the portrait is appropriate for the time period of Sosius’ life; indeed, the image is reminiscent of the upward-gazing portraits of Alexander the Great. The choice of Greek for these tokens was not only a statement of identity on behalf of the issuer, it was also a statement made by the creator of the token for his audience: the users of these pieces presumably also knew Greek (or else would have known enough to have been suitably impressed by the appearance of Greek in this context).

Figure 3.21 Pb token, 19 mm, 12 h, 4.96 g. CWC|IOY / Bare male head right (Gaius Sosius?).

Indeed, the frequent use of (often very abbreviated) legends on tokens is an important source of evidence for levels and types of literacy in antiquity. The use of legends on tokens, particularly on tokens that carry nothing but a legend as in Figure 3.1, suggests that both the creators and users of tokens were able to recognise these brief texts. The closest parallel to the abbreviated and frequently (to modern eyes) cryptic combinations of letters found on tokens are perhaps the painted inscriptions (tituli picti) carried on amphorae.Footnote 159 When examining these inscriptions, Woolf advocated seeing writing as a set of graphic symbols to be interpreted, with different types of writing (commercial, funerary, military inscriptions) employing different conventions to communicate their message to the reader. Woolf focused on the painted messages on Dressel 20 amphorae, which required an understanding of the conventions and systems used by all those involved. Similarly, the creators and users of tokens were likely to have understood the conventions of this particular medium: abbreviated tria nomina, for example, the occasional use of interpuncts to distinguish between words (e.g. between P and Tettius on Figure 3.16), and recognising that the central dot on these artefacts was related to manufacture rather than any specific message (see Chapter 1).

Indeed, given that tokens were manufactured for a specific audience, only a relatively small group of people needed to understand the conventions employed; the varying designs of tokens between regions suggests that, unlike Dressel 20 amphorae, the semiotic system was local to a particular region. In the Latin-speaking West, regions might produce semiotic conventions for tokens within the broader framework of everyday Latin, but each development appears to have been unique. For example, the tokens of Lyon utilise two and three letter Latin legends that appear to be tria nomina, but the tokens of this region also make greater use of accompanying signs (e.g. palm branches or ivy-leaves) than similar tokens found in Rome and Ostia.Footnote 160 The local form and design of tokens, in this sense, must also have contributed to a sense of local community through semiotic conventions.

Identity through Work

A wide variety of material culture attests to the fact that many in the Roman world identified themselves through their work. Funerary monuments might display the deceased at work, or specifically mention their vocation.Footnote 161 The tomb of Eurysaces the baker at the Porta Maggiore in Rome epitomises this phenomenon: this large tomb carries cylindrical spaces which are thought to represent the cavities in which dough is kneaded, the activities of the bakery are shown in relief towards the top of the tomb and Eurysaces is named as a baker (pistor) and contractor (redemptor) in the inscription.Footnote 162 Tokens too carry statements of identity that refer to work. In several instances tokens and their imagery also appear to have reinforced feelings of belonging between members of a collegium. This is explored here through two case studies: representations of porters (saccarii), and the tokens referring to the coachmen (cisiarii) who ferried individuals between Ostia and Rome.

Several tokens carry images of saccarii, the porters who carried goods from ships to warehouses along the docks in Ostia and Portus.Footnote 163 Figure 3.22 is one such example, issued by an individual named Quintus Fabius Speratus (otherwise unknown). A saccarius is also portrayed on lead tokens accompanied by the legend AGM or OBB on the other side, or the representation of three corn-ears.Footnote 164 Although one might be tempted to link these lead tokens with the mechanics surrounding the operations of the port, these specimens are more likely to be connected to acts of communality and euergetism.Footnote 165 If we accept that the three letter legends AGM and OBB may be initials (although we cannot be certain), then three out of the four token types carrying representations of saccarii appear to carry personal names, likely advertising an act of munificence for a broader group. There is enough evidence to suggest the saccarii of Portus had joined together into a larger, more formal community – the Theodosian code mentions an organisation which might well be a collegium, corpus, sodalicium or similar association, while epigraphic evidence suggests a funerary organisation for this group of workers.Footnote 166 Commensality, for example communal banquets, would have acted as an occasion in which the identity of the group was made salient and internal hierarchies reinforced; if tokens played a role on these occasions their imagery would have served to further this process.Footnote 167 The representation of saccarii at work in numerous port scenes (e.g. carrying sacks of ‘things’ (res) on the Isis Giminiana fresco found in a tomb from the Porta Laurentina) demonstrates that these workers had a specific iconography, and were seen as integral to the harbour and its operations.

Figure 3.22 Pb token, 18 mm, 12 h, 3.21 g. Saccarius standing left holding a sack or dolium on his shoulders and with right arm raised / Q·FAB·SPE around.

An orichalcum token also shows a saccarius carrying an amphora over his shoulder (Figure 3.23).Footnote 168 The issue is part of a broader series of orichalcum tokens (including the so-called spintriae) issued during the Julio-Claudian period, likely by a workshop in Rome that produced pieces for a variety of individuals or groups.Footnote 169 The saccarius is nude and decidedly more heroic-looking than on the lead token, although amphora-carrying saccarii are also shown nude on marble reliefs. Figure 3.24, for example, shows nude saccarii each carrying an amphora off a ship. The porters walk towards three officials, one of whom gives the rightmost saccarius an object. The object was thought by Rickman to be a token; he suggested this was a method of ensuring the number of amphorae leaving the ship was the same as that entering the warehouse.Footnote 170 The precise shape of the object is difficult to discern, but it does not appear to be a small circular token; rather it seems a longer, more rectangular object.

Figure 3.23 Orichalcum token, 20 mm, 5 h, 7.3 g. Laureate head of Augustus left, within wreath / Saccarius standing front holding an amphora over his shoulder; XV in field right. Cohen vol. VIII, 254 no. 101, BnF 16979.

Figure 3.24 Marble relief showing saccarii offloading amphorae from a ship, 43×33 cm. Found in Portus, now in the Torlonia collection (inv. no. 428).

High quality orichalcum tokens and marble reliefs might be thought beyond the financial means of harbour porters, but Virlouvet makes a convincing case that the group comprising the saccarii may have also included the officials involved in the transport and distribution of goods beyond the port. The monopoly afforded the saccarii in the Theodosian Code, as well as the honours and activities recorded for saccarii in Italy and elsewhere in the Empire (e.g. reserved seats in the theatre at Smyrna, a statue at Perinthus) suggests this group was wealthier than scholarship has traditionally thought.Footnote 171 The token and the relief, then, might have been created by one of the saccarii, or else the physical identity of these workers was utilised by another group to communicate a port scene, or the abundance of supplies their work ensured.

Virlouvet notes that although saccarii frequently appear in mosaics, frescoes and reliefs, they rarely have a central role – the tokens are important exceptions to this rule.Footnote 172 Their presence in the ‘background’ of life in Rome’s ports was also physically manifest in the small terracotta figures of saccarii found throughout Ostia. Martelli’s study of the findspots of these pieces led her to suggest that these were representations of the Genius of the college of the saccarii; if she is correct we may also have a Genius represented on the lead tokens discussed above (Figure 3.22). In Ostia, these small statues are mainly found in public places: in niches and locations frequented by numerous people. Whoever erected these figures and whatever their motivation, it is clear that the image of a saccarius formed an important backdrop to Ostia; we should not be surprised, then, that they figure so frequently in port scenes.Footnote 173 The figure of the saccarius was not only important to the identity of the porters and their associates, but to the maritime identity of Ostia as a port settlement.

The second example I wish to explore is the assemblage of tokens found in the baths of the cisiarii in Ostia. The cisiarii were drivers who transported passengers between Ostia and Rome, named for their two-wheeled vehicle, the cisium.Footnote 174 A bathhouse that may have belonged to the collegium of these drivers (perhaps of a semi-public character) has been excavated on the north side of the Decumanus in Ostia, near the Porta Romana.Footnote 175 Although the baths and their finds have not yet been studied in detail, the surviving decoration reveals a scheme that evoked bathing, the sea, diversion and entertainment, as well as the work of the cisiarii themselves. In the frigidarium (Room C) a black and white mosaic depicts city walls at the very edge of the room, likely representing Rome, and a second set of city walls are placed in the centre, likely representing Ostia. Between these walls cisiarii are depicted with their carriages, with the names of the mules at times included.Footnote 176 Mosaics in other rooms carry maritime motifs (room B), representations of athletes (room E) and a scene of an animal fight (room A). Stucco reliefs in room F depict gorgoneia, sea monsters, Nereids, Mercury and erotes. The entirety communicates to the user a setting of relaxation and entertainment within a port city at the gate where the cisiarii presumably collected and dropped off their customers.