Self-harm refers to a range of behaviours with a non-fatal outcome in which an individual intentionally causes harm to themselves, irrespective of the motivation or degree of suicidal intent.1 It is the strongest risk factor for completed suicide, especially when repeated,Reference Owens, Horrocks and House2,Reference Zahl and Hawton3 and places a heavy cost burden on healthcare systems.Reference Sinclair, Gray, Rivero-Arias, Saunders and Hawton4 It is one of the most common reasons for accident and emergency (A&E) visits, accounting for over 200 000 visits every year in England alone.Reference Clements, Turnbull, Hawton, Geulayov, Waters and Ness5 However, most self-harm occurs in private and does not come to the attention of clinical services, so its true prevalence is unknown.Reference Geulayov, Casey, McDonald, Foster, Pritchard and Wells6 The national suicide prevention strategy for England identifies the management and reduction of self-harm as a priority area for action and a key progress indicator.7

Problems with outcome measurement

People's reasons for self-harming are wide-ranging and complex,Reference Klonsky8,Reference Edmondson, Brennan and House9 and the interventions offered to those who self-harm are diverse. They include drug treatments targeting underlying psychiatric conditions and psychosocial interventions mainly targeting cognitions and behaviour, but despite huge research effort there remains little evidence to guide clinical decision-making. A recent series of Cochrane reviews found no evidence of effectiveness for any pharmacological treatments in adults,Reference Hawton, Witt, Taylor Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell and Hazell10 only moderate evidence for some psychosocial interventions in adults,Reference Hawton, Witt, Taylor Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell and Hazell11 and no compelling evidence for either in children and adolescents.Reference Hawton, Witt, Taylor Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell and Townsend12 These results raise questions about whether it is the interventions that are flawed or the trial science. Reviews repeatedly point to small participant numbers as a contributory factor, but an alternative explanation may lie in the selection of outcomes and the means whereby they are measured.Reference Owens13

The most commonly used primary outcome is reduction in repetition of self-harm, which is frequently measured by way of a proxy, namely hospital presentations. Psychometric scales of depression, anxiety, hopelessness and suicidal ideation also feature regularly. Other outcomes selected for measurement are heterogeneous, including such diverse measures as fear, aggression, alcohol use, ‘emotional clarity’ and ‘trauma-related guilt cognitions’.Reference Hawton, Witt, Taylor Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell and Hazell10–Reference Hawton, Witt, Taylor Salisbury, Arensman, Gunnell and Townsend12 The variety of clinical and non-clinical problems experienced by people who self-harm may make it necessary for trials to measure a number of different outcomes.Reference Hawton and Sinclair14 Nonetheless, single small trials have been known to include as many as ten different measures, some of which appear to have no strong theoretical basis. Such practice places a heavy burden on trial participants, increasing the likelihood of attrition. More seriously, it suggests lack of clarity about what interventions are designed to do and lack of consensus within the field about what outcomes are important. Without the latter, it is difficult to develop interventions that adequately address the needs of this population.

The importance of patient perspectives

Problems of heterogeneity in the selection of outcomes for measurement has long been recognised, and in many clinical specialities has led to the development of core outcome sets.Reference Felson, Anderson, Boers, Bombardier, Chernoff and Fried15 These establish an agreed set of outcomes to be measured and reported as a minimum in all trials of interventions for a given condition, and are widely advocated as a way of simplifying and standardising trial design and improving comparability of results.Reference Clarke16–18 They need to be based on consensus between all stakeholders, including patients. Patients often have very different ideas from clinicians about what they want treatments to achieve, and their views on what outcomes are important are not always reflected in trials.Reference Staniszewska19 When trials measure outcomes that are of interest to clinicians and scientists but do not take account of patient perspectives, the resulting evidence lacks relevance and fails to support well-informed shared decision-making.Reference Gandhi, Murad, Fujiyoshi, Mullan, Flynn and Elamin20

Little is known about what outcomes matter to people who self-harm. As part of a broader investigation of challenges in the conduct of self-harm research and as a prelude to the development of a core outcome set, we asked people with histories of self-harming behaviour for their views on some of the outcome measures in current use, and on the sort of changes they would want interventions to bring about for them.

Method

Design

We conducted a qualitative interview study in order to elicit the views of people with lived experience of self-harm. All aspects of the study were informed by a patient and public involvement process.21 At an initial stakeholder workshop, self-harm service-user representatives identified the need for more meaningful trial outcomes as a research priority. This was followed by a series of publicly advertised discussion groups (co-ordinated by R.D., L.F. and N.S.) to refine the focus and study design. Two service-user representatives (L.F. and N.S.) sat on the project advisory group.

Participants and recruitment

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 18 or over and had attended A&E for self-harm within the past 3 years. We recruited participants through both hospital and community settings in order to capture as wide a range of experiences as possible. Members of the liaison psychiatry team in the A&E department of a large city hospital identified eligible patients, introduced the study and asked whether they were willing for their contact details to be passed to a researcher. A community-based, voluntary-sector self-harm support service in the same city displayed an advert for the study in its premises and on its website, and sent information to all members of its mailing list. The advert was also disseminated via Twitter. Those who responded were sent a letter, information sheet, reply slip and prepaid envelope.

Data collection

Participants took part in a single interview, with the option of face-to-face, telephone or email, and all provided written consent. Face-to-face and telephone interviews lasted up to an hour and were audio-recorded and transcribed. Transcripts of email interviews were generated automatically. All interviews were conducted by F.F. and followed the same semi-structured topic guide, designed to explore participants' views on the outcome measures currently used in trials of interventions for self-harm, what ‘improvement’ would mean to them and how it might be measured (see supplementary data 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.93).

Analysis

Transcripts were anonymised and analysed using thematic analysis, in combination with a framework approach.Reference Braun and Clarke22–Reference Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid and Redwood24 Two members of the team (C.O. and F.F.) read all the transcripts closely in order to become familiar with the data and generate possible codes. These included some a priori codes reflecting interview questions and others resulting from inductive or open coding. These were discussed with members of the wider team and then applied to the complete data-set, first using NVivo software to code transcripts, and later charting the material using Excel to create a matrix of rows (participants) and columns (themes and subthemes) and populating it with summarised data segments and interpretive notes (see supplementary data 2).Reference Gale, Heath, Cameron, Rashid and Redwood24 This framework method provides a ‘viewing platform’ from which to survey the entire coded data-set, enabling comparisons within and across cases (participants) and identification of higher-level conceptual themes.Reference Ritchie and Lewis23 The final stage involved visual mapping of themes and subthemes, during which they were further refined, and working via a series of iterations towards a final analytic narrative.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by South West – Frenchay NHS Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 16/SW/0296). All participants gave written informed consent to interview.

Results

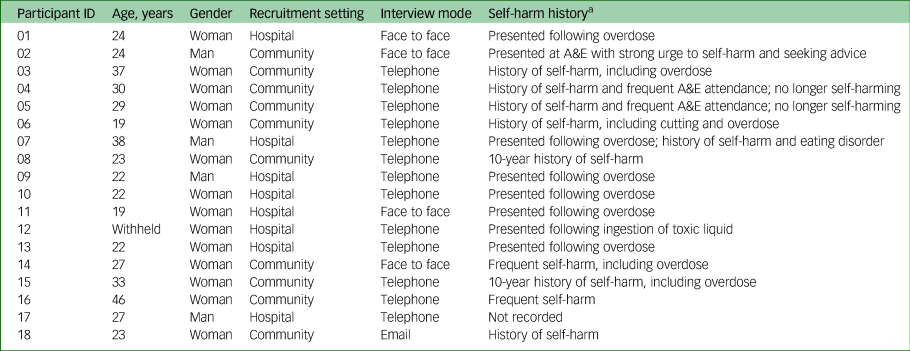

We recruited 18 participants: 8 from a hospital A&E department and 10 through community settings. There were 14 women and 4 men. The average age was 27 years (range 19–46; hospital average, 24 years; community average, 29 years). The majority of participants in both groups had attended A&E for self-harm more than once during the past 3 years (hospital 6/8; community 7/10). Two of the community participants reported that they were no longer self-harming, after having done so for many years. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. We present our findings under two broad headings: challenges to the validity of current outcome measures, and differences in the conceptualisation of outcomes and measures.

Table 1 Participant characteristics

A&E, accident and emergency.

a Details of hospital-recruited participants were supplied by the clinical team. Community-recruited participants were allowed to disclose as much or as little as they wished about their self-harming history.

Challenges to the validity of current outcome measures

‘Obviously, I guess the best outcome would be that people stop self-harming.’ (Participant 02)

‘I haven't self-harmed for a really long time … It's such an awful thing … The further I got from it the better I was, definitely.’ (Participant 05)

Some participants, like those cited above, stated that ‘quitting’ self-harm was their long-term goal and that reduction in frequency (how often they were self-harming) could be a useful measure of progress towards it. However, they were all quick to qualify this or add a ‘but’, pointing out that the relationship between self-harm and mental health was not straightforward and that it was wrong to assume that less frequent is necessarily better. Likewise, measuring benefit by means of reduction in frequency of hospital presentations was seen as problematic, as was the use of standardised scales purporting to measure depression and anxiety. We identified five cross-cutting themes representing challenges to the validity and meaningfulness of outcome measures currently used in self-harm trials, with two further themes relating to the context in which participants’ views were framed. Figure 1 presents a visual representation of these findings.

Fig. 1 Challenges to the validity of current outcome measures.

Severity versus frequency

The issue of severity was raised repeatedly and was seen as being in an inverse relationship to frequency: the more frequent the self-harm, the less serious it was likely to be, and vice versa. When discussing acts of self-harm, participants typically distinguished between ‘big ones’ (acts of violent or severe self-harm, possibly with suicidal intent), which are less frequent but more injurious, and ‘little ones’ (superficial wounds or small overdoses), which are more frequent but less serious. They stressed that frequency by itself meant nothing:

‘It could be that you're doing it less often but it's more severe, and is that really an improvement? … Like, if it's less frequent and less severe, then that's an improvement.’ (Participant 06)

One participant explained that the longer she resisted the urge to self-harm the more the tension built up inside her, eventually resulting in a suicide attempt or major injury, and questioned whether this meant that she was ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than someone who gave in to their urges more frequently but inflicted less damage.

It was clear from participants’ accounts that not all acts of self-harm are regarded as equal and that, if researchers are only interested in counting episodes, there are questions as to what ‘counts’ – how serious an act needs to be and what methods qualify for inclusion. Some suggested that they would not count head-banging or biting, for example. Others were reluctant to discount even the most minor forms of self-harm, stating that, although they may not result in visible injury, they were still experienced as troubling and were indicative of distress.

Severity of injury was also seen to have a bearing on frequency of hospital visits, and therefore on the visibility of self-harm, as only the ‘big ones’ were likely to require medical treatment. Thus, a reduction in frequency of A&E visits might signify a reduction in severity, but not necessarily in frequency of self-harm. One participant noted that the severest injuries were not always intentional:

‘The only time you'd go to hospital is if it was really severe. So you're not actually measuring when they're self-harming, you're only measuring things like when they had an accident and it got too deep.’ (Participant 07; our emphasis)

It was clear that severity of injury and need for medical attention was a matter of individual judgement on each separate occasion, and was always influenced by a number of factors, including previous experiences of treatment, feelings of shame and embarrassment, and skill in self-management of wounds (see Self-management skills). Perceived healthcare failures, including previous A&E treatment that was experienced as hostile or punitive, were likely to result in avoidance of hospital care.

Behavioural substitution

A closely related theme was that of substitution, or switching from one type of behaviour to another. Nearly all participants stated that a reduction in frequency of more typical behaviours, such as cutting and overdosing, was by itself no indication of improvement. Individuals may have switched to alternative methods, possibly less overt and less likely to require medical treatment, or to other equally maladaptive behaviours, such as excessive drinking or disordered eating (bingeing or starvation). This again raised the question of what ‘counts’ when counting instances of self-harm. Participants stressed that researchers should pay closer attention to what people are doing instead of self-harming, as alternative coping strategies may be positive or negative:

‘So [a good outcome] would be utilising more positive coping strategies.’ (Participant 03)

Positive coping strategies may include seeking help, which increases the visibility of self-harm and thus may produce an apparent rise in frequency, but this would be a misrepresentation of what is happening, suggesting a poorer rather than a better outcome.

Switching services may skew trial results in the opposite direction by reducing visibility. One participant noted that reduction in A&E visits would be a false marker of progress for her because she had been making more use of alternative services. The frequency of her help-seeking had not reduced, but the fact that she was no longer using statutory services might make it appear to have done so:

‘So instead of going to a proper hospital I go to the crisis house, and to me that's not really a measure of success.’ (Participant 15)

Self-management skills

It was clear that some participants had become skilled in self-administered wound care and that this, combined with other factors such as shame and previous poor experiences of hospital care, affected frequency of presentation at A&E:

‘As time goes on I go to hospital less frequently … . There are times when I should go, but I've become better at dealing with it myself, better at first aid, so I don't feel the need.’ (Participant 06)

One participant explained that when she was younger she was terrified by the idea of going to A&E and hardly ever did so, but that she now regarded hospital avoidance as irresponsible. She explicitly challenged the notion of reduction in hospital visits as an indicator of progress, believing instead that getting proper hospital care represents good coping behaviour. Another participant, who had gone to A&E seeking help to overcome a violent urge to self-harm, highlighted the role of A&E as a place of safety and means of self-harm prevention. As noted above, the adoption of better coping strategies, including seeking medical care, may have the paradoxical effect of heightening visibility and thus suggesting that self-harm has increased when in fact it may have decreased or stayed the same.

Self-harm as means of survival and affect regulator

Participants highlighted the function of self-harm as a means of survival, pointing out that some people self-harm in order to stay alive and that, although stopping self-harming might appear to be a good outcome, there were risks involved in relinquishing one's survival tool. As noted earlier, reducing the frequency of recurrent, minor forms of self-harm may result in more extreme injury:

‘If it's a habit and then you stop the habit, what happens in a crisis time? Like, if they haven't got that, do they just completely slash their leg open?’ (Participant 11)

Another highlighted the function of self-harm as an affect regulator, describing how it elevated her mood, masking symptoms of depression and giving her a false sense of wellness. She suggested that self-report measures might capture that elation and interpret it as improvement (and as attributable to a therapeutic intervention), but that such an assessment would be wrong:

‘I felt like I was doing well in life because I had this way of surviving, and [when] I was doing it I felt better and felt I could live through the next day, and I wouldn't have rated myself as depressed at all … Now I look back and think, obviously I was so depressed that I needed that, but at the time I thought, “I'm fine, I'm surviving”.’ (Participant 05)

Secrecy and strategic self-presentation

Secrecy emerged as a recurrent theme in participants' accounts. The practice of ‘keeping it hidden’ was seen to have a direct bearing on the extent to which the frequency of both self-harming acts and self-harm-related hospital visits could be reliably measured. Participants noted that it was up to the individual to decide not only whether or not to seek hospital treatment, but also whether or not to reveal the self-inflicted nature of the injury when they do. They admitted both to self-harming in secret and to being less than honest about it when they were forced to seek medical care:

‘They [hospital staff] do ask you, “Have you self-harmed before?” “No, of course not, these are some other sort of injuries”.’ (Participant 01)

The issue of honesty also arose in relation to self-report questionnaires, typically measuring depression and anxiety, which are commonly used in research and clinical practice. Although some participants defended the use of these, believing that plotting their ups and downs over time could be helpful, others complained of frustration or fatigue arising from their routine, uncritical use, particularly when mental distress was manifest. Nearly all participants commented that reliable measurement of mood is contingent upon honesty, stating that how much they revealed about their mental state could vary from one occasion to another and was determined by their own overriding need or purpose at that time. They reported responding strategically, both on questionnaires and in other clinical contexts, either downplaying or exaggerating their distress in order to achieve particular ends:

‘However honest I try to be, I feel like I end up manipulating the result in one way or another, and a lot of people I speak to feel the same.’ (Participant 02)

One participant described how she had been concealing her self-harm and avoiding A&E for some time, for fear that she would be stopped from going to university. While she needed to be seen to be coping, others described needing to be seen to be struggling. Either way, they were seeking to control how others perceived them by reducing or increasing the visibility of their self-harm. Within a context of scarce resources, high thresholds for clinical care and perceived healthcare rationing, participants described how they sometimes made a show of their self-harm, escalating its severity and inflating their scores on depression/anxiety scales in order either to win access to care or to prevent valued services being withdrawn. This too was regarded as a means of survival:

‘You'd exaggerate it a bit just so people would take you a bit more seriously … You want the help and … there are limited places and obviously they're going to give them to the ones that are most in need.’ (Participant 09)

One participant gave a graphic account of how she had gambled with her life, taking a huge and potentially lethal overdose, as a result of which she was now receiving the highest level of mental healthcare. While admitting the risk she had taken, she believed that she had had no other option:

‘You feel like you have to prove how much you're suffering … I think I have to prove it in order to access services … because no-one really takes any action until you've actually done something and then you get people really listening to you … It just feels like actions speak so much louder than words.’ (Participant 15)

Other participants, also mindful of the scarcity of healthcare resources, spoke of the need to use hospital time responsibly and suggested that this might deter them from attending A&E.

Differences in the conceptualisation of outcomes and measures

Participants did not find it easy to articulate what ‘improvement’ meant in relation to self-harming behaviour or how it should be measured, and were often only able to answer after the question had been posed several times in different ways. Even then, their answers lacked clarity and seemed to conflate measures of improvement with means of improvement. Although at first this appeared to be a limitation of the data, closer analysis suggested that participants were not actually confused but were conceptualising outcomes and measures in a radically different way. Figure 2 presents a visual representation of key differences, described in more detail below.

Fig. 2 Conventional versus user-defined outcome measures.

Indicators of improvement

We identified three broad areas of user-defined outcomes, all of which focus on positive behaviours or achievements, rather than simply on not self-harming.

General functioning or the ability to perform activities of daily living and engage in normal self-care emerged strongly in participants’ accounts of what is important to them, and was regarded as an indicator that things were getting better:

Interviewer: ‘So what's a sign to you that things are going well or that you're improving?’

Respondent: ‘For me it's that the flat is tidy and that I'm at work when I should be, I'm wearing clean clothes and I'm washing every day and things like that … ‘cos they're the first things that fall through, aren't they, if you're not feeling very well. For me anyway, like I'll just not get out of bed … I'll overeat or I'll just eat snacks and crisps and sweets and stuff like instant foods … So that's how I know I'm feeling good.’ (Participant 11)

Social participation also featured prominently. Participants characterised their bad times in terms of withdrawal and being ‘closed off’, whereas improvement was marked by being more open and outgoing, seeing family and friends and pursuing hobbies and interests. This was a sign of having more energy and motivation, which was associated with ‘being in a good place’. One participant noted that such activity is noticeable by others and that asking close friends and relatives might sometimes be more useful than relying on self-report measures:

‘It's something that can be identified by someone close to you, because I live with my mum and she often picks up on things before I do … I tend to withdraw when I'm in a low mood, and if I'm a bit more open and engaged that would be an indicator that there is improvement.’ (Participant 08)

A third area of user-defined outcomes concerned engagement with services. Several participants stated that proactively seeking healthcare or attending therapy sessions were signs of progress. These signified improving energy levels, as well as a commitment to recovery and self-care. Participants reported that when they were unwell they would miss appointments or fail to collect repeat prescriptions. Being able to engage with services and adhere to medication was therefore seen as a key marker of improvement. Some noted that this was at odds with the thinking currently underpinning trials of interventions for self-harm, in which not utilising hospital services is seen as the positive outcome. Participants regarded this as deeply puzzling:

‘I mean [people who self-harm] should be getting all the help they can possibly get.’ (Participant 10)

Measure or means (or both)?

What was striking in the way participants talked about each of these potential outcome domains was their tendency to slip from talking about these things as measures of improvement into language that implied they were also a means of improvement, and back again. The following is an example:

‘When I was really unwell I just wouldn't get up and go [to therapy] … But actually when you look at my attendance record, once I started going every single week I was getting so much better. So I think engaging in services is quite a good measurement … I guess it's the same about medication compliance … because when I picked up my repeat prescript every month and saw my GP [general practitioner] and got into that pattern of accepting help and taking my medicine, I definitely improved … and that's something that's easy to measure.’ (Participant 05)

The participant is saying that attendance and adherence are positive outcomes in themselves and as such can be used as measures of improvement (‘when I was really unwell I just wouldn't get up and go’), and at the same time that they are the means whereby the improvement is achieved (‘when I got into that pattern of taking my medicine, I definitely improved’).

Another participant, when asked how he would measure improvement, or what kind of things might indicate to him that he was doing better, talked about how he had found the courage to go off travelling (indicator), and how he had come back a ‘completely different man’ (the activity itself had brought about further positive change).

This suggests a more constructive way of thinking about outcomes than has hitherto been seen. Conventional trial outcomes are conceived as ends in themselves and, because they focus on not self-harming and not returning to A&E, they leave a behavioural void in which participants may well ask, ‘What are we supposed to do instead?’ The user-defined outcomes proposed by our participants, on the other hand, take the form of activities and achievements, small practical triumphs that can be celebrated in themselves, but which may in addition have an ongoing positive effect and be a means of sustained improvement (Fig. 2).

Discussion

These frank interviews given by people who self-harm contain a number of challenges to the validity of the main outcome measures used in trials of interventions for this population, calling into question both the logic behind the use of these measures and their ability to capture what is actually happening. Our data suggest that the use of these measures is based on a set of flawed assumptions, namely that fewer recorded self-harm episodes, fewer visits to A&E and improved scores on mood-rating scales reflect genuine improvements in the lives and mental well-being of those who self-harm. Our findings also draw attention to a complex array of extraneous factors (severity of self-harm, behavioural substitution, self-management of wounds, the affect-changing power of self-harm itself and strategic self-presentation) that affect our ability to make accurate measurements and may seriously confound trial results.

An observed reduction in either self-harm or A&E presentations may mean a great many things. It may be a high-risk outcome, associated with increased likelihood of severe injury or suicide, and it may be illusory, merely reflecting a reduction in the visibility of certain behaviours. Conversely, an observed increase, particularly in A&E visits, may not be the negative outcome we assume it to be. It may signify less concealment, less service avoidance and increased willingness to accept help, which participants regard as positive signs. This highlights the seemingly perverse logic of self-harm trials, which appear, at least to some participants, to be intent on keeping people out of services that are designed to help them. Although understandable in view of the pressure to demonstrate healthcare cost savings, the high value accorded in self-harm trials to reducing hospital visits conflicts with a wider public health discourse that seeks to encourage help-seeking. It may also perpetuate among vulnerable individuals the perception of healthcare rationing, which, as our data show, can drive them to desperate lengths, risking their lives in order to prove their need.

Health behaviours pose special challenges for outcome measurement because of the complex functions they perform for those who engage in them, the invisible motivational pathways that give rise to them, and the often hidden nature of the behaviours themselves. They differ in these respects from physical diseases, in which signs and symptoms are involuntary and observable. Our study shows not only the extent to which those who engage in troubling health behaviours are able to control what others see and quantify, but also provides reasons why they may sometimes conceal and at other times display both the behaviours and the underlying cognitive–emotional states.

These findings fit with Nock's distinction between the intrapersonal (affect-regulating) and interpersonal (communicative) functions of self-harm, the former being more likely to be associated with concealment and the latter involving visible display.Reference Nock25 They also both confirm and augment Geulayov and colleagues' suggestion of a ‘tip of the iceberg’ situation with regard to self-harm.Reference Geulayov, Casey, McDonald, Foster, Pritchard and Wells6 Geulayov et al distinguish between overt (fatal and hospital-presenting) and covert (community-occurring) self-harm and demonstrate the extent to which this limits our ability to measure overall incidence. Our findings show that our ability to measure trial outcomes is also limited to those acts and affects that participants allow us to see – those they choose for their own reasons, including self-preservation, to render visible.

Implications for future research and intervention development

The randomised controlled trial is the gold-standard design for evaluating healthcare interventions. However, our study highlights a number of fundamental tensions between trial science and the lived experience of people who self-harm.

Randomised controlled trials are predicated on a ‘paradigm of order’, in which variables are controllable and effects predictable.Reference Geyer and Rihani26 Behaviours such as self-harm are complex, disorderly and unpredictable, although close examination may reveal that they possess a logic all of their own. Our findings certainly suggest, as do other qualitative studies,Reference Edmondson, Brennan and House9 that people who self-harm have very cogent reasons for behaving in the ways they do and very clear personal goals, but these are not well aligned with conventional trial outcomes. Nor are they necessarily amenable to measurement using standardised means, because of their sometimes personal and idiosyncratic nature.

The answer is not to abandon trials but to recognise their problematic nature and to mitigate the risk of spurious or misleading results. This can be done in a number of ways. The first is to incorporate thoroughgoing process evaluation, using in-depth qualitative methods to tease out what is really happening and what any observed effects might mean. The second is to conduct robust patient and public involvement at the very earliest stage of trial design to ensure the inclusion of outcomes that are relevant and meaningful to those who self-harm. This may also help to improve recruitment rates and reduce respondent burden. The development of a core outcome set for self-harm trials remains a long-term goal. It is beyond the scope of this article to describe the core outcome set development process, which is well-documented elsewhere,Reference Williamson, Altman, Blazeby, Clarke, Devane and Gargon17 but the present study suggests that achieving consensus between different stakeholder groups (clinicians, researchers and people who self-harm) will not be easy.

Meanwhile, intervention developers should focus on understanding and targeting user-defined outcomes. By doing so, we may be able to move from quick ‘fixes’ that may look promising but leave a dangerous behavioural void to providing people with the means to make tangible changes in their everyday lives, thereby sustaining positive effects and contributing to their own ongoing recovery.

Limitations of the study

Our sample was small and drawn from one English provincial city. We collected limited data on demographics, number of self-harm episodes or motivation for self-harming, and did not distinguish between self-harm with intent to die and non-suicidal self-injury.

The discussion of outcomes formed only one part of a longer interview covering other trial-related issues, including recruitment practices. Participants found it conceptually challenging and some of them struggled to formulate their thoughts, particularly about what outcomes were important to them. We recognise that we may not have fully captured their views and that further in-depth work is needed. Nonetheless, to our knowledge this is the first study to investigate what people with histories of self-harm think about trial outcomes, and it provides further valuable insight into their everyday worlds.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.93.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West (NIHR CLAHRC West). K.T. is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Postdoctoral Fellowship: PDF-2017-10-068. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who participated in the research or helped with recruitment, and those who helped shape the study through the patient and public involvement work. We had many helpful discussions along the way with Professor David Gunnell, who also commented on an earlier draft of this manuscript, and we are grateful for his advice.

Author contributions

C.O. formulated the question (with K.T.), advised on study design, led the analysis of data and wrote the manuscript. F.F. conducted the interviews, assisted with early analysis of data and commented on written drafts. S.R. managed the project, contributed to study design and commented on written drafts. R.D. led the patient and public involvement (PPI) work, advised on study design and recruitment, and commented on written drafts. L.F. facilitated PPI work, advised on study design, supported community recruitment and commented on findings and written drafts. N.S. facilitated PPI work, advised on study design, supported community recruitment and commented on findings and written drafts. S.W. advised on design and conduct of the study, facilitated hospital recruitment and commented on early drafts. L.B. advised on study design, assisted with early analysis of data and commented on written drafts. K.T. formulated the question (with C.O.), contributed to study design, analysis and interpretation of data and commented on written drafts. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.