People who are older aren't paying as much attention because

they will not be as affected. They don't take us children

seriously, but we want to show them we are serious.

Ayakha MelithafaFootnote 11. INTRODUCTION

Young people today exercise powerful political, moral, and social influence in global efforts to address climate change. In September 2019, a global coalition of school students organized a global strike under the Fridays For Future (FFF) campaign, which mobilized 7.6 million participants across 6,000 protest events in 185 countries.Footnote 2 Since July 2020, United Nations (UN) Secretary General António Guterres meets every few months with a Youth Advisory Group on Climate Change.Footnote 3 Children and young people have become founders and leaders of influential environmental action groups, from the Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change to the Sunrise Movement in the United States (US). While these branches of the youth climate movement are increasingly the subject of scholarship and critical attention, one tool in the arsenal of young people against global warming remains under-examined: strategic litigation.

Thirty-three rights-based climate cases – 26% of those filed globally prior to 2021 – have involved plaintiffs who are children under the age of 18, a children's non-governmental organization (NGO), or a class of children. Many also involve ‘youth’ plaintiffs.Footnote 4 This approach to strategic climate litigation at the international, regional, and national levels is rooted both in the increasing prominence and power of youth climate activists, and in the convergence of climate governance with children's rights. While others have identified this as an important development,Footnote 5 its origins and its implications for child rights have not yet been closely examined. This article therefore contextualizes this body of ‘youth-led’ litigation and examines its implications for child rights specifically, rather than human rights generally, rooted in the broader literature on strategic climate litigation and children's rights.

Section 2 situates this growing body of youth-led litigation within its broader legal and political history, linking developments in international climate governance and child rights advocacy with youth organizing around environmental and climate justice. Section 3 outlines the methodology used to investigate whether these cases serve to advance (or undermine) the rights of children. To answer this question, Section 4 looks at the legal arguments in each case, providing jurisdiction-specific analysis of the arguments that were presented, not presented, and addressed by the court. Section 5 then examines how children's rights are advanced through their participation in legal processes.

Several conclusions emerge from this analysis. Firstly, child claimants are particularly well placed to bring powerful claims for intergenerational justice in climate litigation. Nevertheless, as a legal and social category, ‘children’ are not interchangeable with ‘future generations’ and child rights arguments are currently under-utilized in youth-led climate cases. Climate litigators should make arguments wherever possible that are specific to children as a demographic. Secondly, it is ethically problematic that we currently have no empirical understanding of how child claimants are affected by this litigation and advocacy. The involvement of children has potential trade-offs and risks, which remain under-addressed. Yet, it also has significant potential to strengthen and shape their critical role as stakeholders in climate solutions, particularly when linked explicitly with the actions and priorities of the broader youth climate movement.

2. BACKGROUND

We are in an age of growing climate disorder. In a review of the available climate science, 16 leading experts concluded in 2021 that ‘future environmental conditions will be far more dangerous than currently believed. The scale of the threats to the biosphere and all its lifeforms – including humanity – is in fact so great that it is difficult to grasp for even well-informed experts’.Footnote 6

Climate change disproportionately affects children's physical and mental health and development.Footnote 7 Their bodies and minds are evolving, making them more vulnerable. They are disproportionately affected by extreme weather events, food and water insecurity, air pollution, and extreme heat.Footnote 8 Natural disasters, climate-related displacement and loss of family income and livelihoods also affect their rights to an education and to play, to be free of child labour, exploitation, and early marriage.Footnote 9 As Gibbons notes, this ‘de facto discrimination against children is compounded by de jure exclusion of their concerns from global [United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)Footnote 10] instruments and policy processes, and from national policies and instruments of climate change adaption’.Footnote 11 Children cannot vote for candidates who propose more progressive climate policy. Though funders, government and civil society now widely apply a gender-based lens to policy and programming, the use of an age-specific lens is rare. Only 42% of all nationally determined contributions make direct reference to children or youth, and only 20% mention children specifically.Footnote 12

Lawyers have sought to address the climate crisis through the courtroom since the 1980s. A recently identified subgroup of this advocacy alleges violations of human rights, dubbed climate litigation's ‘rights turn’.Footnote 13 Rodríguez-Garavito argues that this rights turn was facilitated by the convergence of ‘two very different and distinct global regulatory regimes – climate governance and human rights … [which opened] fresh legal opportunities and additional mobilization frames’.Footnote 14 The Paris AgreementFootnote 15 was a crucial moment in this convergence, supplying underlying legal logic for many subsequent human rights-based cases that address climate change.Footnote 16

Opportunities and mobilization frames have also emerged from the convergence of climate governance and children's rights, a subcategory of human rights law grounded in the field's most widely ratified treaty, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).Footnote 17 Historically, children have not been explicitly accounted for in environmental standards, lawmaking, or rights discourse.Footnote 18 The Paris Agreement marked the first occasion on which states were formally asked to consider the rights of children when taking climate action.Footnote 19 Cocco-Klein and Mauger note that, while significant, this was an incomplete victory: the obligation was located in the non-binding Preamble; it did not hold states accountable to protect children's rights; and it overlooked the potential of children to contribute to climate action.Footnote 20

Since 2015, efforts to integrate children's environmental rights in climate governance and international law have gained steam. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC Committee) has taken a central role in this process, dedicating its 2016 Day of General Discussion to children's rights and the environment.Footnote 21 In 2017 and 2018, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)Footnote 22 and the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, John Knox, published documents on children's environmental rights.Footnote 23 Knox outlined three types of state obligation in this context: (i) educational and procedural obligations to consider the views of children and provide for effective remedies; (ii) substantive obligations to protect children from environmental harm by ensuring that the best interests of children are respected; and (iii) obligations of non-discrimination. A coalition of prominent child rights activists, advocates and institutions – known as the Children's Environmental Rights Initiative (CERI) – subsequently formed under the auspices of the Rapporteurship on Human Rights and the Environment.Footnote 24 CERI has coordinated the Intergovernmental Declaration on Children, Youth and Climate Action, which was first presented to state leaders at the UN Human Rights Council session on 30 June 2020, with 15 state signatories as at early 2022.Footnote 25 In 2021, the CRC Committee announced that it will issue a General Comment on children's rights and the environment.Footnote 26

This international legal mobilization has been accompanied by a dramatic strengthening of the youth climate movement. Young people have engaged in environmental activism for decades;Footnote 27 however, this demographic is increasingly recognized as a ‘powerful force for change’.Footnote 28 Young people are engaged in national electoral politics,Footnote 29 taking a central role in advancing progressive policies such as the Green New Deal.Footnote 30 They are engaged in activism, leading the #FridaysforFuture movement, organizing a student movement for fossil fuel divestment,Footnote 31 and engaging in climate governance at the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC.Footnote 32 Indigenous youth climate activism, though understudied, is an influential part of this picture.Footnote 33 Youth organizing has the potential to increase engagement exponentially on climate change across families, communities and policy.Footnote 34 Scholarship on civic engagement shows that those who ‘become engaged at a younger age are more likely to stay engaged in volunteerism and politics throughout their lives’.Footnote 35

Young people, for several years, have been involved in litigation to address environmental harm.Footnote 36 A prominent example is the 1993 case of Minors Oposa v. Secretary of the Department of Environmental and Natural Resources, in which the Supreme Court of the Philippines ruled in favour of a class of children (represented by their parents) who sought to cancel timber operations in the area where they lived, relying on a constitutional provision protecting the right to a healthy environment.Footnote 37 Youth-led cases, however, are still relatively scarce, in large part because of the dramatic challenges that children and young people face in accessing court systems.Footnote 38 Some barriers to justice are situational. There is almost a total absence of education for children to inform them of potential legal avenues to remedy infringements of rights.Footnote 39 Moreover, the financial burdens of litigation exclude it as a viable option for most, especially for marginalized children. Other barriers are legal. Historically, children were treated as ‘objects and not subjects of the law’, treated as the property of their parents rather than rights-bearing individuals.Footnote 40 Although there is now almost universal recognition that children are legal persons with their own interests,Footnote 41 they are still overwhelmingly required to approach courts through a guardian ad litem, who instructs the lawyer and makes decisions on how to proceed. Very few countries have nuanced rules that account for the different and evolving capacities of individual children in legal processes.Footnote 42

There has been considerable attention paid to children's participation in criminal proceedings and the treatment of child victims and witnesses in such proceedings.Footnote 43 However, the participation of children in civil proceedings has largely been limited to a few contexts. The CRC General Comment No. 12 on the right to participation, for example, lists only three ‘main issues which require that the child be heard’: (i) divorce and separation; (ii) separation from parents and alternative care; and (iii) adoption and fakalah of Islamic law.Footnote 44 The recent increase in children and young people utilizing legal systems to defend their rights in the context of climate change suggests that this ‘right to be heard’ implicates a much broader range of issues. This remains a serious gap within the children's rights literature.

3. METHODOLOGY AND OVERVIEW OF YOUTH-LED CASES

The ‘youth-led’ cases reviewed (listed below in Table 1 at the end of the article) were sourced from Rodríguez-Garavito's work in cataloguing the cases filed in judicial or quasi-judicial bodies at the international and national levels that explicitly refer to both climate change and human rights in their submissions or decisions. To understand how child rights play a role in this litigation, each case was reviewed to identify (i) whether children's rights are incorporated in the relevant jurisdiction; (ii) any child rights arguments advanced in the case, either substantive or procedural;Footnote 45 and (iii) the treatment of those arguments in any decisions. To understand how the involvement of children in this litigation had an impact on rights, a review was conducted of publicly available information on the role that claimants took in advocacy campaigns surrounding these cases, as well as academic and grey literature on child participation, the youth climate movement and strategic litigation, particularly litigation which addresses climate change and children's rights.

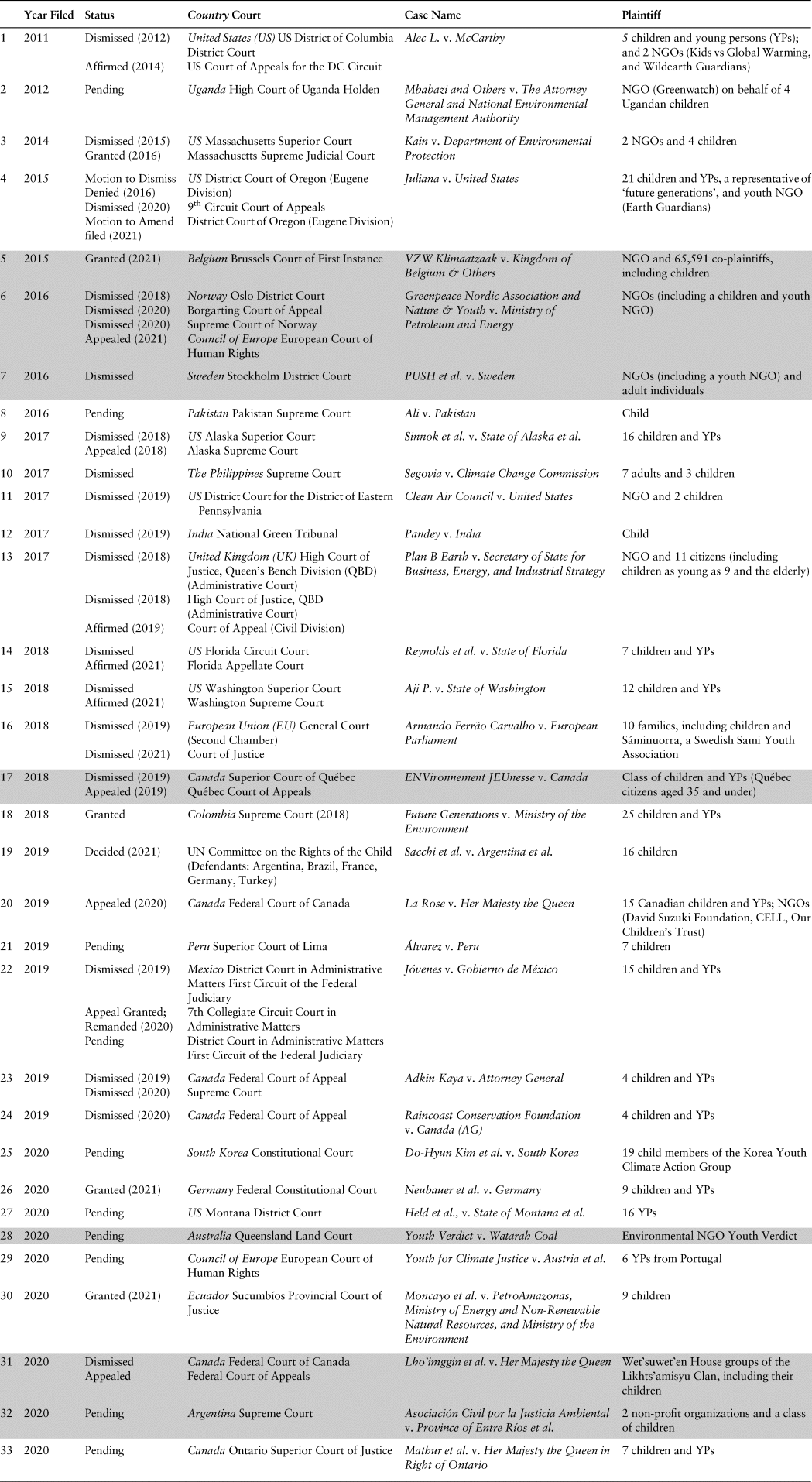

Table 1 Youth-Led Climate Cases Filed before 2021

Source Table drawn from Rodríguez-Garavito, n. 14 above.

Note Cases initiated only by organizations or a class, with no individually named child plaintiffs, are highlighted in grey.

‘Youth-led’ is defined to include cases involving plaintiffs who are (i) named children and young people, (ii) an NGO led by children and young people, or (iii) a class of children and young people.Footnote 46 Note that the cases included all involve ‘children’, defined by the CRC to include those under the age of 18. However, the analysis also encompasses ‘young people’, a similar socially constructed category: while the UN defines this group to include those between 15 and 24,Footnote 47 the typical upper age limit for membership within youth climate organizations is 35.Footnote 48

By the end of 2020, 33 youth-led cases had been filed across 21 countries and supranational forums, representing 26% of the 126 rights-based climate cases initiated during that time.Footnote 49 In 27 of these cases, children and young people are joined as named plaintiffs represented by their legal guardians, while seven cases involve youth non-profit organizations or a class. Following Rodríguez-Garavito, cases are included only where they specifically mention fundamental rights.Footnote 50

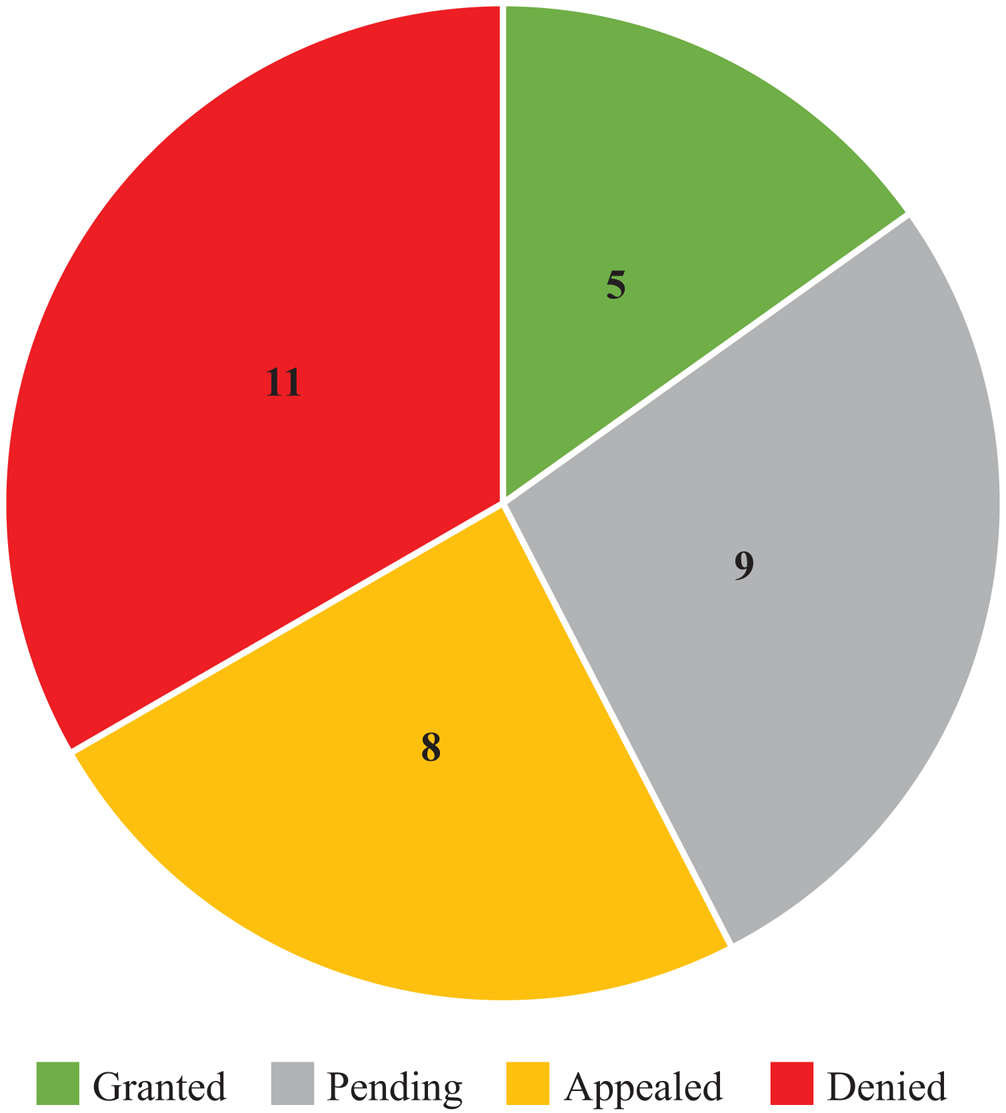

The plaintiffs all challenge the climate actions and omissions of sovereign states, save one that targets a fossil-fuel corporation.Footnote 51 Parker and co-authors note that the majority of youth-led climate cases challenge insufficient efforts to reduce carbon emissions and meet climate commitments, while a minority challenge specific regulatory approvals that are expected to have dramatic climate impacts.Footnote 52 As shown in Figure 1, five cases thus far have been successful,Footnote 53 while eleven remain pending review, eight are on appeal, and nine have been dismissed.

Figure 1 Status of Youth-Led Rights-Based Climate Cases Filed before 2021

4. LEGAL ARGUMENTS IN YOUTH-LED CLIMATE LITIGATION

In 2019, 16 children filed a petition through their legal guardians with the communication mechanism of the CRC Committee (CRC Petition) against Argentina, Brazil, France, Germany, and Turkey.Footnote 54 This mechanism allows for the consideration of complaints of potential treaty violations.Footnote 55 The plaintiffs alleged that the actions and inactions of member states on climate change violate their rights – to life, health, culture, and respect for their best interests – and violate the affirmative obligations imposed on states to ensure intergenerational equity and prevent foreseeable human rights infringements.Footnote 56 In October 2021, the Committee declared the petition inadmissible on the ground that the plaintiffs had not exhausted available remedies in the national courts. Nevertheless, the Committee affirmed that ‘states have heightened obligations to protect children from foreseeable harm’.Footnote 57

This section examines the legal arguments advanced in youth-led cases. It does not focus on claims more typically advanced in rights-based climate lawsuits with adult plaintiffs, such as violations of the rights to life, dignity and health, and to a clean and healthy environment.Footnote 58 Rather, the section looks at arguments based on the principle of intergenerational equity. In addition, it discusses the arguments specific to children's rights, reviewing the extent to which those rights could be invoked and have been invoked to date. Overall, youth-led climate cases currently under-utilize arguments for children's rights.

4.1. Intergenerational Equity and Future Generations

All but threeFootnote 59 of the youth-led climate cases filed to date have made arguments based on the principle of intergenerational equity – that is, arguments that the action or inaction at issue unlawfully prioritizes the present over the future. As Brown Weiss has written, this principle demands that each generation is able to meet its own needs through the conservation of access, diversity and quality of planetary resources.Footnote 60 Intergenerational equity is not only relevant for children; some rights-based climate cases with adult petitioners have relied on the concept.Footnote 61 The principle does not appear in the CRC, but is affirmed in both the UNFCCCFootnote 62 and the Paris Agreement.Footnote 63 Nevertheless, the concept is particularly relevant for children, who bear no responsibility for the climate crisis but will disproportionately suffer its escalating harm. This section argues that children are particularly well placed to invoke intergenerational equity in their claims.

There are two approaches to enforcing intergenerational equity. The first is the public trust doctrine, used by the campaign coordinated by the US Our Children's Trust. This doctrine enshrines the government obligation to manage public resources within its jurisdiction in a sustainable way, resources that include the atmosphere.Footnote 64 Public trust obligations are related to, but distinct from the second approach to intergenerational equity (taken by 58% of cases), which focuses on the human rights held by future generations – from dignity to health – and government obligations to protect against violations of those rights associated with climate change. Plaintiffs who adopt this second approach in domestic courts rely on references to future generations in statutory law or in national constitutions, in the hope that the courts will ‘interpret these provisions and transform them into legally enforceable rights’.Footnote 65

Rights of future generations have been central to three of the five successful cases filed to date. In April 2021, the German Constitutional Court in Neubauer v. Germany granted a challenge brought by nine young people and children (represented by guardians) to the German government's emissions reduction plan.Footnote 66 The Court held that this plan violated Article 20a of the German Basic Law, which says that the state ‘shall protect the natural foundations of life and animals’ in a way that is ‘mindful of its responsibility toward future generations’.Footnote 67

To make this broadly phrased right justiciable, the Court read Article 20a as requiring, at a minimum, adherence to Germany's commitment under the Paris Agreement to maintain certain global temperature targets, which limited Germany to a finite ‘budget’ of GHG emissions.Footnote 68 The government's emissions plan specified targets only until the year 2031. Leaving future reductions unarticulated allowed current generations to consume an unfairly large portion of the country's total emissions ‘budget’. This left ‘[later] generations with a drastic reduction burden [that] exposed their lives to comprehensive losses of freedom’.Footnote 69 The Court also acknowledged that, while the state typically enjoys a measure of discretion in implementing broadly phrased rights, this discretion is limited where democratic processes provide inadequate checks on political decision making. Here, it found that ‘future generations … naturally have no voice of their own in shaping the current political agenda’.Footnote 70

There are at least two main reasons why children are well placed to advance powerful claims for future generations. The first relates to legal standing, as courts are open to considering children as members of future generations. In Neubauer, for example, the Court found that the ‘complainants [have standing because they] are not asserting the rights of people who have not yet been born … Rather, [they] invoke their own fundamental rights’.Footnote 71 Similarly, the Colombian Supreme Court ruled in 2018, in Future Generations v. Ministry of the Environment et al., that rates of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest and resulting temperature increases violated the fundamental rights of future generations.Footnote 72 The Court noted in its ruling that the scope of fundamental rights included ‘future generations, including the children who brought this action’, a group of 25 plaintiffs aged between 7 and 25.Footnote 73 Nevertheless, as Parker and co-authors note, standing and justiciability remain significant challenges to the success of youth-led, rights-based litigation.Footnote 74 This is true for all forms of rights-based litigation.Footnote 75

In contrast, other courts have been reluctant to recognize the rights of people not yet born and have avoided addressing the legal standing of future generations. For example, the plaintiffs in the constitutional case of Juliana v. United States, filed in 2015 in the US Federal Court, included a group of 21 young people and children (represented by guardians) who were aged between 8 and 19 at the time of filing, as well as a ‘guardian for future generations’, the adult scientist James Hanson. The District Court judge declined to address the question of legal standing for future generations because the youth plaintiffs had established current harm.Footnote 76

The second advantage of involving children in efforts to protect the rights of future generations is that these claimants can mitigate the potential unintended implications for reproductive rights. If climate change unacceptably threatens the rights of the unborn, including the right to life, then abortion could also violate those rights. Sterba made this argument in 1980, writing that ‘many of the arguments offered in support of abortion on demand by [liberals] are actually inconsistent with a workable defence’ of ‘the rights of future generations to a fair share of the world's resources’.Footnote 77 Sterba concluded that ‘the only morally acceptable way for liberals to avoid this inconsistency is to moderate their support for abortion on demand’.Footnote 78

To give an example, access to abortion is currently legal in Colombia only in limited cases which include rape, incest, and protection of the mother's health. Those who oppose the expansion of this right could feasibly employ the conclusion of the Colombian Supreme Court in Future Generations v. Ministry of the Environment et al. that there is a legal obligation to protect the right to life ‘for our children and for future generations’.Footnote 79 However, there is a strong counter-argument here. The right to life for future generations is not a ‘right to be born’, but rather a right to life-sustaining conditions for those who are already living, including the child plaintiffs. Additionally, the Supreme Court ascribed other rights to future generations that the unborn could not logically hold, such as the right to freedom.Footnote 80

4.2. Children's Rights Arguments

Notwithstanding the advantages of treating children as members of future generations to advance intergenerational equity, children are actual citizens in the present day. It is the responsibility of the lawyer to address their interests in the petition fully, making arguments specific to their experiences. While arguments for intergenerational equity address the drastically unequal burden of the climate crisis across time, they do not fully address the disproportionate types of climate harm that children face now.

While states enjoy a measure of discretion in setting environmental standards that respect human rights, this discretion is limited with regard to children by the state's substantive and procedural obligations under the CRC and obligations of non-discrimination.Footnote 81 However, the children's rights claims available to litigants depend on context. Jurisdictional rules limit how and where children's environmental claims may be argued. While almost every state in the world has ratified the CRC – the US being a glaring exception – the manner and extent to which these entitlements are incorporated into national law varies.Footnote 82 Firstly, the CRC can be invoked directly in jurisdictions where treaties are automatically incorporated into national law, or where the CRC has been implemented through enabling legislation. This is the case in ten of the 21 national jurisdictions where youth-led climate cases have been brought.Footnote 83 In some states, such as Norway, incorporated treaties take precedence over national laws; in others, such as Germany, the CRC is subordinate to the Constitution and may be altered by subsequent federal law.

Secondly, children's rights protections can be invoked wherever they are separately articulated. For example, although Australia has not incorporated the CRC, the Queensland Human Rights Act 2019 states that every child has the right to protection that is in the child's best interest.Footnote 84 Importantly, separately articulated children's rights are not always directly relevant to climate litigation, such as guarantees to provide education free of cost. O'Mahony notes that visible constitutional provisions for children may not treat children as independent, autonomous rights holders and they may be enforceable only through an administrative body, or not at all.Footnote 85

Lastly, even in jurisdictions where the CRC is not incorporated and the constitution makes no mention of children, litigants in rights-based climate cases can advance protection for children if age is an accepted ground for discrimination claims. Age-based discrimination, or ‘ageism’, is not explicitly mentioned in the CRC.Footnote 86 Yet, climate change has disproportionate effects on children's rights: litigants in some circumstances can leverage well-established equal protection precedents to address this discrepancy.

It is not always possible for litigants in youth-led climate litigation to advance children's environmental rights explicitly, but cases to date still under-utilize viable child rights arguments that could successfully be invoked in climate change litigation. In many instances, plaintiffs in jurisdictions where children's rights are enforceable have advanced none of these claims.Footnote 87 For example, in a case filed in 2016 in Norway, People v. Arctic Oil, a child and youth organization challenged oil licences approved by the government as violating Article 112 of the Norwegian Constitution, which states that the right to a healthy environment will be safeguarded for future generations.Footnote 88 The case did not mention the CRC, which is directly applicable in Norwegian law and takes precedence over conflicting national statutes, or Article 104 of the Constitution, which provides explicit protection for children's rights, including the best-interests principle.Footnote 89

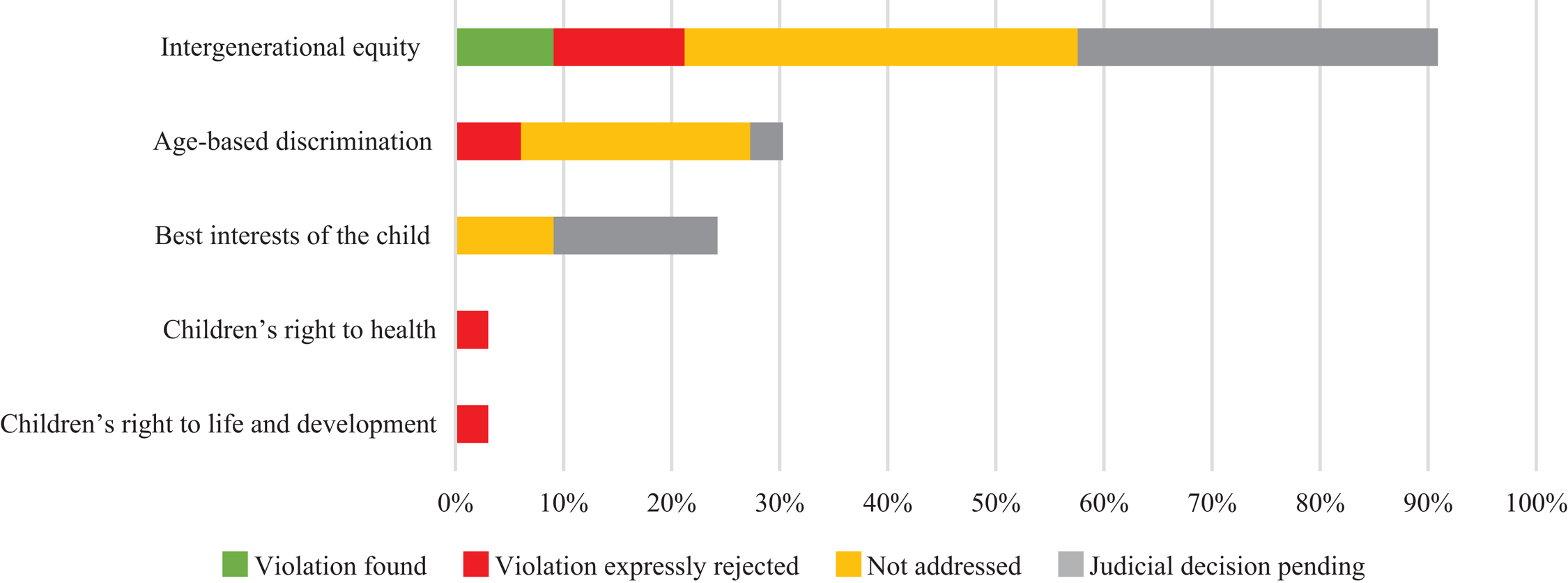

As shown in Figure 2, the range of children's rights invoked has been narrow, consisting mainly of age-based discrimination claims and arguments for children's rights to have their best interests considered as a primary matter, as enshrined in Article 3 CRC and many national and regional instruments.Footnote 90 In the sole case where additional children's rights were invoked, prevailing Belgian law did not give direct effect to the cited provisions of the CRC (rights to development and health).Footnote 91 Thus, while the Belgian court ruled in VZW Klimaatzaak v. Kingdom of Belgium & Others that the government's climate change policy had breached the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR),Footnote 92 it was not found to have violated children's rights.Footnote 93 Similarly, states’ procedural obligations towards children's environmental rights have not been relied on in youth-led climate litigation.Footnote 94 Children's right to be heard on issues that affect them, articulated in Article 12 CRC, is enforceable in 11 jurisdictions in which youth-led cases have been brought.Footnote 95 Only in the CRC Petition, however, did the claimants request that the respondents ‘ensure the child's right to be heard [in all] efforts to mitigate or adapt to the climate crisis’.Footnote 96

Figure 2 Substantive Arguments Advanced in Youth-focused Rights-based Climate Litigation, and their Treatment by Courts

In eight cases, claimants alleged violations of the best interests principle, but no court has yet explicitly addressed this argument. The Court in Neubauer held that respect for the foundations of life for future generations required time-sensitive implementation of the Paris temperature targets, failing which unconstitutional harm was reasonably foreseeable. Similarly, respect for children's best interests is inimical to a world with dangerous levels of global warming. As the CRC Committee held in its decision on the children's climate petition, ‘the potential harm of the [various] State part[ies] acts or omissions regarding the carbon emissions originating in [each state's] territory was reasonably foreseeable’.Footnote 97 Though this ruling is confined to admissibility and the decision is not binding in national courts, it illustrates the clear link between inadequate climate action and children's rights.

Similar logic applies to claims based on children's ‘inherent right to life … survival and development’, enshrined in Article 6 CRC and various national constitutions.Footnote 98 This would be a new approach: courts have not yet upheld the child's right to development. Peleg has argued that this right protects and promotes the fulfilment of children's human potential to the maximum extent possible,Footnote 99 a composite right that encompasses but extends beyond protection of children's physical, mental, moral, social, cultural, spiritual, personality and talent development. The human potential of children is foreseeably harmed by climate change.

The best-interests principle and the right to development are both balancing principles. Historically, no binding and specific substantive obligations have attached to the best-interests principle, even in its more traditional realms of family disputes and medical decision making.Footnote 100 Nevertheless, other climate cases have determined justiciable limits on formerly ambiguous guarantees by relying on evidence of climate harm of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The link between foreseeable harm and children's rights may be less clear, however, where an individual policy or project is challenged, rather than national emissions standards. This was an issue in a recent case based on tort law, rather than human rights, brought by eight young people in Australia. In Sharma v. Minister for the Environment, a Federal Court held that the Minister for the Environment owes a novel duty of care to children who might suffer potential ‘catastrophic harm’ from the climate implications of approved projects.Footnote 101 Nevertheless, the Court did not find that approval for the project in question – a coal mine extension – foreseeably caused catastrophic harm which violated the duty of care. The Minister for the Environment later reiterated its approval for the project and in 2022 a full Federal Court overturned the earlier decision.Footnote 102 Each writing separately, the judges held that the plaintiffs could not make out the essential grounds of a common law negligence claim.Footnote 103

The Sharma case underscores the importance of a rights-based approach to balancing children's rights against climate harm. Even the lower court's favourable decision was based on children's ‘special vulnerability’ and innocence, and not their affirmative rights. The Court did not conduct a best-interests analysis of the Minister's decision or order the government to conduct such an analysis by measuring, publishing and justifying the impacts of the mine on children.Footnote 104

In contrast to the above-mentioned arguments for substantive environmental rights, several youth-led cases have argued, thus far without success, that climate change creates age-based discrimination. Six of nine such claims were brought in the US, which has narrow equal-protection jurisprudence. In Juliana v. United States, the plaintiffs argued that government climate actions violate constitutional non-discrimination guarantees, ‘impos[ing] significant risks and injury to children's well-being for matters beyond their control’. This was rejected in part by the District Court, which noted that the equal protection precedent excludes children as a protected category.Footnote 105 The other three cases were brought in Canada, where discrimination claims based on age historically have been rejected on the grounds that children have vulnerabilities that can require differential treatment by the state,Footnote 106 such as laws that regulate when young people can engage in different kinds of work.

It is possible, however, that an ageism claim would be feasible in other jurisdictions. In Ecuador, for example, Article 23 of the Constitution explicitly prohibits discrimination on the grounds of age. Jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) also suggests that the personal scope of non-discrimination law can encompass children.Footnote 107 As Kaya argues, both the personal and material scope of non-discrimination law can encompass types of climate-related harm: either in states the constitutions of which prohibit discrimination without articulating how that prohibition applies; where non-discrimination is a general principle of law; or where forms of legal protection for private and family life or housing are applied in conjunction with non-discrimination guarantees.Footnote 108 Nevertheless, an important limitation of age-based discrimination claims is that ageism does not describe the differential burdens of climate change between children: its impacts on children of different genders, ethnic backgrounds, economic status, etc. To intervene, the law demands a clear causal link between action and injury, and these inequalities are not only the result of climate change. Youth-led climate cases should therefore bring ageism claims in conjunction with other claims, and highlight disparities between children by selecting plaintiffs from marginalized constituencies and elevating their unique experiences through advocacy.

In sum, children and youth claimants are particularly well placed to advance powerful arguments for greater legal protection for future generations and to avoid some of the risks that this approach might create. Still, the future-generations framing fails to generate much-needed attention on the present-day exclusion of children's vulnerabilities from environmental law and policy. Courts, thus far, have been unwilling to define enforceable obligations relating to children's rights in climate litigation. In the handful of occasions on which courts have expressly addressed these arguments, they have dismissed them. The pending CRC Committee General Comment on children's rights and the environment will substantially assist advocates in seeking to rely on children's rights provisions in climate cases, providing an authoritative interpretation of state obligations under the CRC towards children in the context of the crisis. As climate change progresses and its impacts on children intensify, the foreseeable harm between climate inaction and children's rights will become harder to ignore.

Youth-led litigation should, wherever possible, advance arguments specific to children as a demographic as well as arguments for intergenerational equity. The potential arguments explored here are not exhaustive. One could also imagine climate cases based on the children's right to education, for example. Child-specific arguments are important not only because they could maximize the likelihood of success; they also avoid instrumentalizing children to seek results that incompletely address their experiences. A legal declaration that climate action must respect the best interests of children or their right to development, or that it must not discriminate against children, would directly support efforts to include special consideration of children's needs in a wide range of climate policies, from adaptation to environmental education in schools.Footnote 109

5. PARTICIPATION OF CHILDREN IN CLIMATE LITIGATION

The first case involving child plaintiffs that used rights-based arguments to address the climate crisis was a constitutional case filed in 2011 by the Oregon-based Our Children's Trust against the US government.Footnote 110 Among the five child plaintiffs was 16-year-old Alec Loorz, an activist and founder of the non-profit organization Kids vs Global Warming and of iMatter, a series of coordinated youth climate strikes which took place that year across 25 countries.Footnote 111 Like Loorz, many of the plaintiffs in youth-led climate cases are engaged in several forms of climate advocacy.

This section argues that the involvement of children and youth in strategic climate litigation can itself meaningfully contribute towards fulfilment of children's procedural environmental rights, elevating the role of this demographic as key stakeholders in and implementers of climate solutions. This is true both directly for the plaintiffs and indirectly for the broader youth climate movement. Nevertheless, such benefits from participation are not possible without fully contending with the potential costs, risks and trade-offs involved. There is no published empirical research into these claimants that explores their perspectives on climate litigation: whether it achieves their goals; how it could be improved; their relationship with the legal system.Footnote 112 This inhibits the development of best practices to guide whether to involve children at all, and allow lawyers, guardians and other relevant actors to best support these plaintiffs’ goals and mitigate any risks during litigation.Footnote 113 Absent this research, this section outlines some potential benefits and risks associated with children's involvement in climate litigation, using public information on the advocacy conducted by child claimants, as well as the literature on strategic litigation and child participation.

5.1. Benefits: The Right to be Heard and Citizenship from Below

There are two principal benefits in involving children and young people as plaintiffs in climate litigation. Firstly, the strength of the youth climate movement illustrates the powerful ideas and moral authority that young people contribute to this issue. Secondly, children have a ‘right to be heard’ on issues that affect them, as recognized in Article 12 CRC. When seen in its best light, participation in strategic climate litigation by children – a constituency that cannot vote – allows them to assert their full citizenship, the kind of ‘republican citizenship’ that Liebel describes as enabling individuals to become active participants in society, not just passive recipients of governmental services.Footnote 114 Liebel writes that this ‘citizenship from below’ is possible where children's actions are not limited to claims for protection, benefits and participation in spaces predefined by adults, but are instead grounded in self-organization and ‘the possibility of a formative part that children can play in society’.Footnote 115

What does the ‘right to be heard’ mean in the context of strategic litigation? Article 12 CRC states that every child capable of forming his or her own views has a right to have those views heard and given due weight according to their maturity on all issues that affect them, including in judicial proceedings. Lansdown argues that this translates within the legal system into four participation rights: to be informed; to express an informed view; to have that view taken into account; and, where maturity allows, to be a joint decision maker.Footnote 116 This applies to all parts of the litigation: case strategy, media and advocacy strategy, and the adjudication process itself, typically including a written statement or appearance as a witness. It also includes any enforcement and oversight where cases are successful. The Colombian Supreme Court, for example, ordered the government to formulate an ‘intergenerational pact for the life of the Colombian Amazon’ with ‘active participation of the plaintiffs’ that would adopt measures aimed at reducing deforestation to zero and GHG emissions.Footnote 117

Children who participate indirectly through an institutional plaintiff or class will not all have an opportunity to give input on case strategy or participate in court proceedings. Nevertheless, they can be closely involved in advocacy. One example is the Norwegian case, People v. Arctic Oil, brought by Greenpeace Norway and Nature & Youth (Natur og ungdom), Norway's largest environmental organization for young people, with 7,672 members and 88 local chapters as at the end of 2015.Footnote 118 After litigation was commenced in 2016, Nature & Youth trained ‘lawsuit ambassadors’, who raised awareness about the case by lobbying local officials and holding events.Footnote 119 Members organized a demonstration on the day before the Norwegian Supreme Court hearing where young people nationwide lit candles to create awareness that oil drilling in the Arctic violates the Constitution.Footnote 120

Individually named plaintiffs will have various opportunities for involvement, potentially mediated by their legal guardians and lawyers. For example, Juliana v. United States involved 21 young persons, aged between 8 and 19 at the time of filing, who became the public face of the action.Footnote 121 The non-profit witness collaborated with Our Children's Trust to produce short documentaries on several plaintiffs, which were shown everywhere from President Obama's Oval Office to the prestigious Wildscreen Festival.Footnote 122 The plaintiffs appeared in congressional hearings and lobbied politicians, regularly speaking with major national and international media outlets about the case and its aims.Footnote 123 Many claimants have since become prominent activists.Footnote 124 Similarly, the lawyers on the petition to the CRC Committee note that the 16 child claimants:

report a sense of empowerment in engaging in the UNCRC process, and are sought after to regularly speak at international and other events. They have formed an advocacy hub which networks widely with youth climate education portals globally, actively write letters to State leaders … and are part of formulating new strategies for engagement and inclusive climate policy at the diplomatic and legal levels.Footnote 125

These examples suggest that youth-led climate litigation can contribute indirectly to the youth climate movement and also offer direct benefits for the individual plaintiffs: learning or long-term career opportunities, as well as a sense of personal fulfilment and purpose.

5.2. Inherent and Avoidable Risks

While children's involvement in climate litigation has the potential to further their procedural rights, their involvement also carries potential costs, risks and trade-offs. There is a total lack of empirical research on this subject, research that is necessary for legal practitioners to mitigate harm responsibly. This section outlines a few possible drawbacks of children's involvement, extrapolating from the existing literature on strategic litigation, child participation and protection. While these potential drawbacks are serious, they do not make a case against children's involvement in climate litigation. Instead, they underscore the need for more inclusive legal systems.

Firstly, strategic climate litigation is time- and energy-intensive. This creates opportunity costs for young people who are still in education. For example, the defence in Juliana v. United States employed procedural tactics which meant the case never went to trial throughout six years of traversing the federal courts. Secondly, past work has shown that child activists, such as Greta Thunberg and Emma Gonzales, are exposed to significant levels of criticism and bullying in physical and digital spaces.Footnote 126 The level of public scrutiny and opposition generated by these climate cases can be high, potentially taking a toll on these plaintiffs in a similar way. The same reasons that make children particularly vulnerable to climate impacts – their ongoing physical and emotional development – may increase their susceptibility to these messages.

Thirdly, the legal process itself can disempower or generate cynicism. This outcome lies partly within the control of the lawyers and whether they ensure the meaningful involvement of children. This work, especially when undertaken in coordination with guardians, is particularly time-intensive and plaintiffs’ lawyers are often under-resourced. Some risks are inherent in the legal system. Not only are the timelines long, but also the scope and probability of available remedies are limited.Footnote 127 Even if a case is successful and the defendant is ordered to take bold climate action, the likelihood that this will measurably improve the plaintiffs’ lived experiences of the climate crisis remains slim. When, in December 2020, the Norwegian Supreme Court chose not to invalidate the government's oil licences in People v. Arctic Oil, Greta Thunberg (who substantially funded the case) noted that the decision ‘just proves that the climate and ecological crisis cannot be solved within today's systems. There are no tools, no laws nor regulations that keep us from destroying the living conditions for life on this planet as we know it’.Footnote 128

Putting a child's name on a lawsuit does not singlehandedly transform his or her relationship with climate change. Bartlett has analyzed children's involvement in local initiatives for climate advocacy and found that such programmes are often isolated events with no long-lasting legacy.Footnote 129 Given that climate change is the product of deep social inequality, Bartlett argues that effective actions to empower children on this issue must form ‘part of a wider culture of participation’.Footnote 130 Similarly, children's participation in climate lawsuits may benefit them most – or harm them least – if it involves meaningful engagement in advocacy external to the case. The scholarship on strategic litigation consistently confirms that the positive societal impacts of cases are also maximized through ‘integrated advocacy’ strategies that combine ‘media engagement to shape and promote the narrative, community organizing to mobilize effected communities and their allies, and interdisciplinary collaborations to [shape] polic[y] and practice’.Footnote 131

Again, the broader literature is silent on when and how litigation disempowers young plaintiffs. It is possible that children may be better placed to withstand public backlash if they have prior experience of climate advocacy, or greater personal stake in the issue given personal experiences of climate injustice. Involving a youth organization may also provide a buffer and support network. Yet, strategic litigators will generally choose their plaintiffs based, first, on whether they can overcome the hurdle of standing – that is, the ability to advance the suit. Children with greater climate privilege may be a better fit in this respect; not all legal systems grant organizations standing, and a case with an institutional face may garner less public attention or empathy than one with a human face.

Importantly, many of the potential challenges scoped here are not exclusive to the young. Engaging with powerful, hierarchical and conservative institutions to address complex problems can generate cynicism in adults and children alike. Strategic litigation has long been criticized for instrumentalizing and tokenizing plaintiffs. For example, Bell wrote of school desegregation litigation in the US that lawyers ‘mak[e] decisions, set priorities, and undertak[e] responsibilities that should be determined by their clients and shaped by the community’.Footnote 132 Additionally, some trade-offs may be real but inappropriate for adults to resolve on behalf of children: for example, whether long hours spent on legal mobilization are contrary to the child's best interests.

The strength of the youth climate movement clearly indicates that children want a seat at the table on this issue. Thus, rather than implying that children should not be involved in the courtroom at all, these potential challenges raise the question of how legal spaces themselves – crucial fora for addressing climate change – should change to accommodate them.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The climate emergency presents an unprecedented challenge to children's rights. Litigation is one critical avenue, among many, to prevent, mitigate, and address the present and future damage. The need for these actions will only grow as climate disorder intensifies. This article has argued that the growing involvement of children and young people in climate litigation has the potential to advance children's rights both inside and outside the courtroom. However, that potential is currently underdeveloped. The focus on intergenerational justice in legal arguments is highly effective. However, it should not crowd out other substantive legal claims specific to children's rights. Climate litigation can also allow politically disenfranchised young people to participate meaningfully in and shape climate outcomes. Yet, the lack of empirical knowledge around the experiences of these young plaintiffs potentially obscures any negative impacts from their involvement. Overall, international, regional, and national strategic litigation can place children front and centre in our collective response to the climate emergency, both as advocates and as victims, while institutionalizing protection for children's rights.