Introduction

Over recent decades, European labour markets have transformed. Job insecurity has become more generalised, a process mostly derived from adjustment policies implemented to overcome a profitability crisis in the world economy that began in the 1970s. In the case of the labour market, focus has been placed on deregulation: legal frameworks regulating labour relations have been made lax in conjunction with dubious inspection practices, and this has facilitated the proliferation of irregular activities. In fact, ‘irregular work’ can be understood as the maximum expression of precarious work, which crystallises in various ways. The most serious effect of ‘irregular work’ has been the exclusion of employees from social security benefits.

Spain presents a paradigmatic case through which to observe the processes of labour deregulation. Although social security achievements have lagged behind those of other countries and were plagued with peculiarities, especially due to the Franco dictatorship which lasted until the early 1970s, the Spanish labour movement did manage to establish certain levels of social protection. The aim of these efforts was to alleviate the instability inextricably linked to the wage relationship. Social security provided workers with protection against market fluctuations and the bargaining and coercive power of employers. In more recent times, labour reforms have ostensibly weakened that protective framework through diverse measures aimed at promoting wage devaluation and worse labour conditions.

This article focuses specifically on the fraudulent use of certain legal forms (self-employment and internships) that usher a significant portion of salaried workers into the framework of the irregular economy. These are two of several ways by which precariousness has filtered into labour relations in the Spanish economy. It has been argued that legal forms such as the dependent self-employed worker respond to structural changes in labour relations that have undergone mutations due to technical and organisational changes. Hence, new rules have been required to regulate such ‘grey areas’Footnote 1 manifesting in labour markets, beyond the binary relationship between capital and labour.

This paper is based on Marxist analysis. In essence, it identifies recent trends in labour relations as increases in exploitation due to capital demands related to low profitability. From this approach, increased precariousness (as false self-employment and bogus internships) have supported the erosion of the wage share (WS) in Spain, which from 2009 to 2019 suffered a drop of 7%.Footnote 2

The article is structured into four sections, beginning with this brief Introduction. In the next section, the theoretical rudiments of the Marxist analysis are exposed as the best way to understand the causes behind increased precariousness followed by a study of how labour deregulation in Spain has followed the European Union (EU) guidelines. The subsequent section addresses the phenomena of ‘false self-employed workers’ and ‘bogus interns’. The paper ends with some conclusions and reflections on the subject.

A history of precariousness

How can the process of degradation of labour relations be understood? Conventional positions argue that social protections once achieved by the demands of the labour movement are now anachronistic and typical of an outdated stage of capitalism (Blanchard, Reference Blanchard2005, De la Dehesa, Reference De la Dehesa2005). Obviously, this position defends very specific interests. From alternative positions, it is considered that capitalism has undergone deep technical and organisational transformations, causing mutations in labour relations (Melle, Reference Melle2019). These new labour realities escape the traditional relationship between employer and employee, drawing new ‘grey areas’ between the poles that traditionally characterised the capitalist relations of production (Williams and Horodnic, Reference Williams and Horodnic2018). Taking such a position to the extreme, it has been argued that the process of growing precariousness in labour relations has given rise to a new social class, the ‘precariat’. Standing (Reference Standing2013) popularised this concept, emphasising that it represents a social class distinct from the traditional working class.

Beyond these positions, Marxist analysis recognises a close link between the main contradiction of accumulation, the tendential erosion of profitability, and the generalisation of job insecurity (Arrizabalo et al., Reference Arrizabalo, Pinto and Vicent2019). It is the operating logic of capitalist accumulation that generates increasing obstacles to the valorisation of capital. The main strategy deployed to alleviate the downward pressure by which profits are subjected has been wage devaluation, and this has been promoted through the precariousness of labour relations.

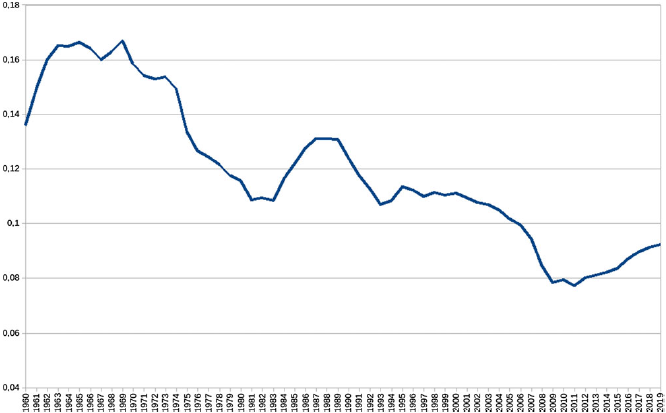

Figure 1 shows the downward structural trend experienced by the rate of profit, understood as the relationship between profits and capital invested in the Spanish economy over recent decades: it represents the central driver of capital accumulation.Footnote 3 Although the decline that the rate of profit showed is a tendency, it intensified when the crisis broke out. In fact, the profitability problem explains the macroeconomic dynamics that led up to the crisis: investment declined, and GDP fell (negative growth rates appeared in the third quarter of 2008).Footnote 4 Although the speculative boom is linked with the crisis, it represents a symptom of the stress on profitability, not the trigger factor (Mateo, Reference Mateo2022).

Figure 1. Rate of profit and crisis (1960 – 2019)

Source: own elaboration from AMECO.

To understand the dynamics of capitalist accumulation, it is necessary to start from a class approach. The relations characteristics of this mode of production are structured around two social classes: owners of the means of production and the waged/salaried workers. On the one hand, once wages have been paid, the owners of the means of production appropriate as profit the remaining new value generated by the labour force. On the other hand, salaried workers (excluded from ownership of the means of production) seek to guarantee their own subsistence by selling their ability to work. In return, they receive a fraction of the final new value in the form of labour income, i.e. a wage. Meanwhile, the other part of the new value is not paid – the surplus value, from which the profit of the owners derives. This is the essence of the process of exploitation, an objective phenomenon through which one social class appropriates a portion of the value produced by others.

Accordingly, wages are the price paid for a special commodity that companies need to produce goods: labour force. As with other commodities, labour theory of value is key to understanding how this price is determined. This theory establishes the value of the labour force as the main determinant of wages. The value of the labour force is based on the value of consumer goods that workers and their families need to ensure their social reproduction. Wages gravitate around this value, which depends on multiple factors of the specific social formation and, of course, on the dynamics of class struggle. Among these factors, the influence of the so-called Industrial Reserve Army (IRA), which reflects the relative overpopulation of workers according to the needs of capital, stands out (Marx, Reference Marx1867: 791).

The IRA is composed of those workers who cannot sell their labour force or those who can only partially sell it, obtaining in exchange less than its full value (Marx, Reference Marx1867: 794). This group includes unemployed workers, underemployed workers, informal workers,Footnote 5 and those who can only get a job when the economic cycle is expanding. In Marx’s own terms, the capitalist mode of production ‘always produces a relative surplus population of wage-labourers in proportion to the accumulation of capital’ (Marx, Reference Marx1867: 935). Thus, the presence of the IRA is both structural and permanent. The main function performed by the IRA is to exert downward pressure on the working conditions of all employees, especially in terms of wages. Rosdolsky (Reference Rosdolsky1978) points out that the existence of this reserve of workers is functional for capital because in addition to regulating the price of the labour force, i.e. wages, it provides reserves of living labour with which to serve the increased needs of such by capital.

The most vulnerable workers are those involved in the informal economy, such as domestic workers or many delivery workers linked to digital platforms. These positions are filled largely by irregular immigrants, allowing owners to employ them without contracts or job protection. As a consequence, these workers systematically suffer abuse. This precariousness especially affects women and young people, and therefore has an enormous impact on the working class as a whole.

Market competition forces individual capitals to systematic mechanisation. On the one hand, this phenomenon affects relations between classes: capital replaces workers with machines and, therefore, the former are forced to adapt to the rhythms of work imposed by the latter. On the other hand, mechanisation turns into the main strategy to reduce the unit costs of production as the key to improving individual competitiveness. Under the market competition inherent to capitalism each individual capital seeks to displace the others by appropriating a growing fraction of the total profit. Therefore, reducing individual production costs are the most effective means for each capital to improve profitability and market share.

Technical change modifies the cost structure of companies by increasing the so-called composition of capital, i.e. the ratio between constant capital (invested in the means of production) and variable capital (invested in the labour force). Thus, mechanisation implies that the fraction of variable capital will be smaller in relative terms. Considering that the labour force is the only productive force with the ability to generate new value and, consequently, surplus value, this dynamic tends to undermine the power of capital to produce profits (Boundi, Reference Boundi2014). Therefore, the perennial technical change due to competition and capitalist accumulation poses a shocking contradiction: despite being motivated by the search for bigger profitability, it diminishes the number of sources of surplus value. For this reason, capitalism shows a long-term tendency in the rate of profit to decline. Recent empirical evidence of this tendency is abundant: Roberts and Carchedi (Reference Roberts and Carchedi2018), Tapia (Reference Tapia2017), Roberts (Reference Roberts2016), Freeman (Reference Freeman2013), Carchedi (Reference Carchedi2012), Kliman (Reference Kliman2011).

Why does each individual capital tend to substitute (to the maximum possible extent) workers for the means of production, despite the dire consequences it has for accumulation in general? Fundamentally, this trend strengthens the control of companies over workers and, moreover, it allows each capital to aspire to obtain an increasing fraction of the surplus value produced globally, even if such a decision hinders the ability to generate new value for capital as a whole. Although this capacity is diminished, each individual capital that incorporates technical changes will reinforce its position in the process of appropriation of surplus value. Capitalism is not a planned system, but one in which accumulation comes from individualised decisions made by capitalists, each of whom considers only their own profitability.

The pressing tendency of the profit rate to fall can be partially counteracted through different processes. The main strategy for doing so is the intensification of the exploitation of workers as a way of expanding the unpaid share of new value produced by the labour force in order to increase the rate of surplus value. Along with this, each capital will also try to improve its position in the distribution of the overall surplus value.

From this theoretical perspective, it is possible to follow the logic underlying the sequence that has dominated the world economy through recent decades. Faced with the outbreak of a crisis resulting from declines in profitability, capital deployed a strategy of wage devaluation to improve the rate of surplus value and thus counteract the structural pressure that hangs over profitability (Arrizabalo, Reference Arrizabalo2014; Mateo, Reference Mateo2022). The generalisation of job insecurity is, therefore, nothing more than a mechanism that guarantees the wage devaluation that capitalist accumulation requires.

Consequently, the legal forms that are analysed in this paper, ‘bogus internships’ and ‘false self-employment’, do not obey new economic dynamics but rather the inherent need of capital to increase the degree of exploitation. These supposed ‘grey areas’ in labour markets between employers and employees are nothing more than the result of capital strategies to reduce labour costs, based on more intense conditions of exploitation (Thörnquist, Reference Thörnquist2015).

The European Union, labour deregulation, and precariousness

In order to fully understand its meaning, the increase in job insecurity must be contextualised as follows. The processes of deregulation by which labour markets have been subjected respond to the need of capital to intensify the conditions of exploitation. This does not simply represent one way among several to manage capitalism, but rather the only possible way by which to guarantee the system’s survival. Through job insecurity, the use of labour becomes cheaper, thus favouring profitability. As underemployment becomes more widespread, the IRA significantly exceeds the limits of open unemployment, affecting not only the groups directly involved in these forms of contracting but also the entire working class, due to the downward pressure it exerts on working conditions in general.

The processes of labour deregulation have generated new contractual modalities rather than regular full-time permanent contracts. These new employment contracts serve to degrade working conditions. In fact, precariousness has taken many more forms:

unwanted part-time jobs, real working hours longer than those signed, involuntarily temporary hiring, lack of social security coverage, subcontracting, the use of labor force for free or semi-free with the fraudulent figures of interns and similar, the non-recognition of the training of workers, etc. (Arrizabalo, Reference Arrizabalo2014: 446).

The EU institutions have adhered to the rhetorical argument that these deregulation processes do not necessarily imply a lower level of social protection for workers.Footnote 6 Combining this discourse with the mantra of competitiveness, they have sought to legitimise the labour deregulation processes they have promoted. Ever since the single market was launched with the Single European Act (SEA), along with the free mobility of capital that this implies, the pressure to deregulate labour markets in Europe has been reinforced. Subsequently, the convergence criteria of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) have served the same purpose. In the context of monetary integration, the EU institutions have weakened the framework for coordinating economic policies that remain in the hands of the states, including labour policies. This strategy calls for ever-tighter deregulation. The deployment of the European Employment Strategy falls within this framework.

Furthermore, the publication in 1994 of the White Paper on Growth, Competitiveness, Employment (European Commission, 1994) defined the growth strategy for European economies during subsequent decades. The reactivation of accumulation required the reduction of labour costs, for which it was necessary to eliminate the so-called non-wage labour costs, i.e. social security contributions. In this sense, this document was very explicit in identifying the bases on which to base economic growth, it being ‘necessary to guarantee an adequate rate of return to permit an increase in the investment ratio and hence in growth’ (European Commission, 1994: 12). To achieve that objective, the paper proposed ‘a considerable downward widening of the scale of wage costs in order to reintegrate those market activities which at present are priced out of it; a reduction in all other costs associated with taking on or maintaining labour, e.g. social security rules’ (European Commission, 1994: 59). In other words, to achieve the desired outcome, it became necessary to erode the social protections achieved in previous decades.

In the Green Paper on Modernising Labour Law to Meet the Challenges of the 21 st Century (European Commission, 2006), paramount importance was given to the deregulation of labour markets. It urged the EU member states to undertake measures to promote labour flexibility:

The traditional model of the employment relationship may not prove well-suited to all workers on regular permanent contracts facing the challenge of adapting to change and seizing the opportunities that globalisation offers. Overly protective terms and conditions can deter employers from hiring during economic upturns. Alternative models of contractual relations can enhance the capacity of enterprises to foster the creativity of their whole workforce for increased competitive advantage.’ (European Commission, 2006: 5)

Inevitably, this served to imbue labour relations with growing degrees of precariousness.

The European Semester, established as a reaction to the Eurozone crisis, was conceived with the same purpose. It is a mechanism by which EU Member States are obliged to submit their economic, budgetary, social, and employment policies to the EC for approval before implementation at the national level. Without such approval, governments cannot implement these policies. In fact, the coordination framework defined by the European Semester is not new, but rather reinforces that established by the Lisbon Strategy.

The emergence of atypical forms of hiring, such as the dependent self-employed worker, resulted from the increasing flexibility of labour markets (Eichhorst et al., Reference Eichhorst, Braga, Famira-Mühlberger, Gerard, Horvath, Kahanec and Kahancová2013). These processes have been accompanied by strong institutional support to promote both unpaid internships and self-employment.

Labour reforms carried out in Spain must be analysed within this context. Although these reforms have deepened since the outbreak of the Eurozone crisis, the measures implemented during the previous phase had been based on the same principles. The establishment of new forms of contracting, the deterioration of workers’ collective bargaining power, the reduction of severance payments, and, in general, a legislative framework more favourable to the interests of capital have been the main elements through which precariousness has been introduced into labour relations (Lorente and Guamán, Reference Lorente and Guamán2018).Footnote 7

EU institutions have always pointed to labour costs, which they consider high, for the serious incidence of unemployment in Spain. The guidelines launched to drive structural reforms of the labour market have therefore focused on this issue. For example, in the Commission Recommendation on the Broad Guidelines of the Economic Policies of the Member States and the Community for the 2003–2005 period, it is stated that ‘less regulation and more flexible work organization (…) would make it easier (…) for people to join the labour force’ (European Commission, 2003: 6). Consequently, it recommends to ‘promote more adaptable work organization and review labour market regulations’ (European Commission 2003: 7). Moreover, under the framework of the European Semester, EU institutions have been particularly belligerent against severance payments in the event of dismissal (European Commission 2017).

The European Central Bank (ECB) has also advocated the need to deregulate the labour market.Footnote 8 The measures demanded of the Spanish government by the Governing Council, during the hardest phase of the recession between 2010 and 2012 are particularly revealing. Decentralisation of collective bargaining, abolition of safeguard clauses aimed at maintaining the purchasing power of wages, wage moderation, and reduction of severance payments.Footnote 9 The degree of similarity between the ECB’s demands and the labour reforms implemented since then is very significant.

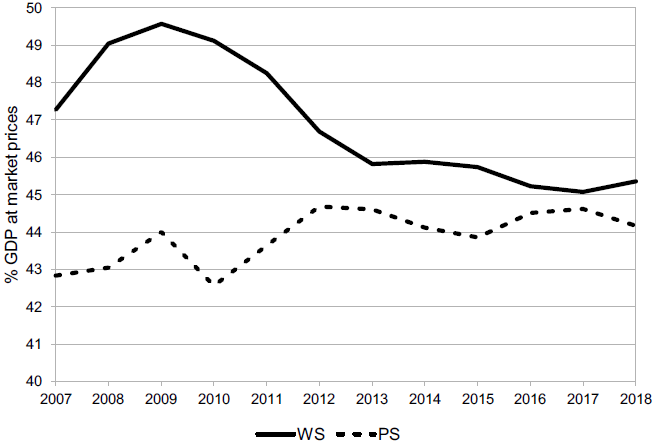

All of this has served to increase the degree of exploitation, visible in the pattern of income distribution when a functional perspective is adopted. Figure 2 shows clear trends: an increase in the relative weight of profits in total income (profit share, PS), to the detriment of the weight of wages (wage share, WS). The trajectory followed by WS offers an insight into wage involution resulting from the needs of capital to revive investment and economic growth.

Figure 2. Relative income distribution in Spain

Source: own elaboration based on INE data.

Bogus internships and false self-employment: precariousness and increasing exploitation

This paper focuses on the fraudulent use of the legal forms of self-employed workers and interns, two of the most significant forms which irregular employment has crystallised in the Spanish economy. When these legal forms are used fraudulently, employers do not declare to authorities the real terms defining the employment relationship, so as to reduce the cost of labour and thus leaving the worker unprotected. Normally, employment contracts signed under these conditions do not meet legal requirements.

In the Director Plan for Decent Work (2018 – 2020) of the Spanish Ministry of Labor and Social Security, the struggle against such operations is established as a priority. For both false self-employment and bogus internships, the real circumstances of the employment relationship do not correspond to the legal form they take.

The social protection of false self-employment and bogus internships is reduced, generating great instability for workers as they are deprived of the rights to which they are entitled by law. In both cases, these are effectively salaried workers who are not protected by the laws that regulate the salary relationship. Thus, these workers are subject to abusive working conditions, since the fraudulent use of these contractual forms violates the protection that labour law grants to employees, including their exclusion from collective bargaining.

Although the main victims are workers engaged on such contracts, overall, wage earners are also impacted, both by the downward pressure exerted on working conditions in general, and the loss of financial resources that these contractual forms imply for the Social Security system.

Bogus internships

Discourse on the need to reduce labour costs as the means by which to promote the employment of young people has taken hold in Spain’s public institutions.Footnote 10 A significant proportion of young people have been forced to access the labour market through internships. In these positions, an interesting confusion arises between training and employment, with the aim of obtaining very cheap, even free labour to reduce labour costs.

The regulation of internships is much more diffuse than general labour relations laws. In addition, each type of internship has its own specific rules. Indeed, a trainee may or may not even be considered as a ‘worker’. In the former case, specific contractual forms exist that allow the worker to be provided with practical experience and theoretical training that he or she may lack. Such contractual forms cheapen the labour force under the alibi that the job provides workers with needed experience or professional training. Both legal forms imply a high degree of precariousness for workers, since they allow employers to pay a remuneration lower than the Minimum Interprofessional Wage (Salario Mínimo Profesional, SMI). In addition, this type of contract does not guarantee job stability for young workers: in ‘2017 only 33% of internship contracts and 7% of training contracts ended up becoming permanent’ (CCOO, 2018: 6). Fraud perpetrated through internships has spread, despite the fact that the 2012 labour reform made the requirements for using these employment contracts even more flexible. Specifically, the reform extended the maximum age for these contracts from 25 to 30 years, provided that the unemployment rate exceeds 15%. Even so, the use of the labour force at a much lower price explains the substitution of salary contracts by internships.

Fraud is mainly concentrated in internship programs that complement a training plan, such as non-curricular university internships and job training, or internships that integrate with training, such as the vocational training cycle and curricular university internships. The EU institutions have promoted this type of internship through the Youth Guarantee Plan, believing that it represents an ideal instrument to promote the employment of Europe’s youngest workers (Sanz de Miguel, Reference Sanz de Miguel2019). This framework has been used by capital to cover up salary relationships under practice agreements that, for the most part, do not even recognise economic compensation to the worker (RUGE-UGT, 2021).

Young people have been the main victims of these types of agreements, which hide wage relations in the form of internships. The deception is not very sophisticated. Although interns actually perform work similar to that of other company employees, their internship agreements only include training tasks. Legally, the criterion to differentiate an employee from an intern is clear: the latter must perform a training activity and be excluded from performing tasks inherent to the professional category for which he/she is being trained. However, in an effective way, it is common for this criterion to be blurred, and for interns to perform tasks that are not their own, diluting the training activity undertaken in an ordinary working day. Thus, employers are able to use parts of the workforce free or semi-free, i.e. youth labour, to fulfil the need for cheap cost labour.

Internships have even been exploited by some training schools, many of them virtual, to generate business through offering training plans which make it possible to hide the employment relationship within an internship agreement. People looking for a job may be offered only non-work practices, where they must enroll in a course that does not interest them to gain access to work. This means that a worker may be compelled to pay to work.

In this type of relationship, working conditions are usually abusive. Due to the highly vulnerable situation of these workers, they often endure longer working hours than agreed upon, along with insufficient or totally absent social protection, and little or no financial compensation, etc. Many of these employment relationships, like most curricular university internships, are unpaid, and those that are paid have an average compensation of EUR 400, well below the minimum wage (RUGE-UGT, 2021).Footnote 11 In addition, it is common that the intern does not receive the professional training specified in the contract (European Commission, 2013a, 2013b). Therefore, in this type of situation, the fraud is twofold: the employment relationship that really corresponds is not recognised (with all that this implies), and the intern does not receive the training agreed upon.

The irregular nature of these contracts makes it very difficult to obtain precise quantitative information on their incidence, although it is estimated that they are among the most widespread fraudulent practices in Europe (Eurofound, 2016).

According to Social Security data, in 2018, there were 866, 079 people carrying out paid university and professional training non-work internships in Spain. It is estimated that the impact in terms of employment is very significant, reaching 296, 310 jobs per year, which represents a reduction in the total compensation of employees of EUR 4.25 billion. The loss of resources for Social Security is over EUR 1 billion (RUGE-UGT, 2021).

False self-employed workers

Something similar occurs with self-employment. Despite being formally self-employed by having a commercial relationship with a company, the worker actually has a disguised wage relationship with that company. In fact, through this type of contract, capital avoids the payment of Social Security contributions typical of salaried work, although the worker maintains a relationship of dependence with what may be his main (or only) client (Serrano, Reference Serrano2016). The apparent independence derived from the type of contractual relationship linking self-employed workers to a company is further diluted when the identity of the real payers of these workers is ascertained.

Moreover, with this approach, the employer prevents the working conditions of the self-employed from being covered by collective bargaining and can therefore terminate the business relationship when the company deems it appropriate, thus avoiding the need for severance payments.Footnote 12 Employers also hinder the union organisation of workers, to whom they can transfer the risks of business activity (Eichhorst et al., Reference Eichhorst, Braga, Famira-Mühlberger, Gerard, Horvath, Kahanec and Kahancová2013, Thörnquist, Reference Thörnquist2015). According to Williams and Horodnic (Reference Williams and Horodnic2018), labour costs can be reduced by 13.8% through this type of operation.

In this case, the regulatory framework favours fraudulent use. To this end, the Statute of the Self-Employed Worker introduces the figure of the dependent self-employed worker (TRADE), an oxymoron that promotes the fraudulent use of the figure of the self-employed worker by companies.Footnote 13 To be included in this category, the self-employed must receive at least 75% of their income from a single client.Footnote 14 In such cases, workers carry out their activity under a strong and frequently exclusive financial dependence on the client company that hires them, which is typical of a salary relationship. Thus, they are formally recognised as independent workers when in fact they are not.

False self-employment has also proliferated through the fraudulent use of the figure of the associated worker, a legal form linked to cooperatives. The aim is to take advantage of the right that the regulations grant to cooperatives to choose the applicable social security regime. In this way, labour relations are masked under the mercantile laws that regulate these legal forms (ITySS, 2019).

The creation of the figure of the dependent self-employed worker was promoted by the European Commission. The aforementioned Green Paper states that the establishment of these new contractual forms responds to a new economic reality: ‘The traditional binary distinction between “employees” and the independent “self-employed” is no longer an adequate depiction of the economic and social reality of work’ (European Commission, 2006). It is suggested that this new contractual form responds to labour changes resulting from certain technical or organisational changes.

This legal form recognises certain rights for workers, related to social security, and even the possibility of regulating working conditions through collective agreements reached between companies and self-employed associations. However, it has a regressive character because, in reality, these are workers who for the most part effectively operate as salaried employees and should be protected as such. From this point of view, dependent self-employment merely provides legal cover for a fraudulent situation.

Although this type of employment has proliferated in recent years in activities linked to digital platforms, such as couriers, its presence transcends the borders of this sector. Precisely due to the fact that such employment has spread in branches linked (in one way or another) to new forms of work organisation, some authors have sought to justify the development as responding to realities that transcend traditional labour relations. For example, Perulli (Reference Perulli2003) points out that these new trends have contributed to the generation of jobs located in an intermediate position between subordinate work and self-employment.

Sanz de Miguel (Reference Sanz de Miguel2019) also argues that the personal and organisational autonomy enjoyed by certain workers justifies that their relationship with the capitalist does not fit into the traditional salary relationship. The emergence of this type of worker would be justified in that, from an

‘economic and social point of view, it cannot be said that the figure of the current self-employed worker coincides with that of a few decades ago (…) self-employment is proliferating (…) in high value-added activities, as a consequence of the new organizational developments and the spread of ICT, and constitutes a free choice for many people who value their self-determination’ (Law 20/2007: Preamble).

In this case, the phenomenon may be taken as purely technical, and not a social issue, with the benefit of representing a free and voluntary decision made by the worker.

However, the social reality is more complex: regardless of the technical characteristics that define the content of these jobs, the illusion of independence that some of these workers seem to enjoy hides the discipline characteristic of the wage relationship. Recent court rulings have recognised that couriers linked to digital platforms are in fact false self-employed who have lost the basic protection offered by an employment contract.Footnote 15 The mediation of digital platforms, which appear in a significant fraction of these labour relations, does not imply a new scheme for labour relations. As has occurred all throughout the history of capitalism, capital uses new technologies to defend its own interests.

Under this type of relationship, precarious conditions are generalised to broader layers of the working class. The limits that labour law draws to exploitation processes are transgressed through the fraudulent use of this contractual form. While labour law recognises that the worker is the vulnerable pole within the salary relationship establishing certain elements for his or her protection (unemployment benefits, severance payments, etc.), commercial law regulates relationships between equals: some companies are suppliers and others are customers. The relationship between employee and company is both unequal and asymmetrical, thus treating the relationship as if it were balanced only serves to enshrine the worker’s vulnerability.

There is also no systematic record of those workers who may be in this situation. The main self-employed associations in Spain have denounced the records of the State Public Employment Service (SEPE) as underestimating the real number of dependent self employed: slightly over 10,000 in 2017 compared to the 228, 900 self-employed workers which the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) points out did not have more than one client during that year. García and Román (Reference García and Román2019) estimate using Eurofound data that Spanish non-salaried employment dependent on a single client accounted for 12% of the total number of self-employed workers in 2017.Footnote 16

Available estimates for the EUFootnote 17 suggest that, this type of employment relationship abounds in productive branches of the economy that are highly significant for Spain. Real estate, construction, hotels, restaurants, tourism, and entertainment are the sectors in which the presence of false self-employment is highest. Within Europe, the incidence is also very high: only 53% of self-employed workers without employees were genuinely self-employed (Williams and Lapeyre, Reference Williams and Lapeyre2017).

Conclusions

The precariousness of labour relations expresses the growing need for capital to exploit workers, with wage devaluation being the main method used to try to counteract the downward pressure on profitability.

In recent decades, labour reforms implemented in the Spanish economy have facilitated the generalisation of precarious hiring conditions. The laxity of the new legal framework that regulates labour relations – especially since the labour reforms of 2010 and 2012 – together with the weakness of the labour inspection system explains the growing misuse of some contractual forms. Capital systematically uses such fraudulent mechanisms with the aim of promoting wage devaluation through avoiding the Social Security obligations. The irregular use of these contractual forms has a strong impact on social protection systems, since it implies a reduction in the resources dedicated to their financing.

In this context, the fraudulent use of self-employment and internships has spread, with these contractual forms being just two of many that precariousness takes. The growth in false self-employment and bogus internships obeys the logic of capital to improve competitiveness through reducing the so-called non-wage labour costs.

Under both contractual forms, workers find themselves in an extremely fragile position, with very low levels of income and without the protection offered by Social Security (which, in the case of the false self-employed, they must pay for themselves). Neither situation is justified by technical innovations, even if these forms are sometimes linked to activities supported by new technologies. Appealing to technological change is nothing more than a way of covering up the fact that these are contractual forms of precariousness in labour relations.

In the case of interns, fraud mainly affects younger workers, who find it increasingly difficult to fully integrate into the labour market. Their training needs are often not met, jeopardising their future prospects. Capital, on the other hand, enjoys lower costs by largely avoiding the payment of Social Security contributions.

The proliferation of self-employment is even more intense, due to its quantitative incidence and the legal support that capital finds in the legal form of TRADE. Through this type of contract, capital avoids the obligations derived from hiring salaried workers and places labour relations in the sphere of commercial law, outside of its own social responsibility. Thus, capital once again avoids Social Security contributions and other rights provided for in collective bargaining, which imply higher labour costs. Moreover, by formally establishing itself as a ‘client’, capital places itself on a false plane of equity with the worker. However, these workers remain in a position of subordination and dependence, their vulnerability exacerbated by having to finance their own social protection and through a lack of protection offered by the Workersʼ Statute to employees.

These two irregular practices (false self-employed and bogus internships) are significant in understanding the increasing incidence of working poor in Spain. According to Eurostat, the percentage of employed workers whose income level did not exceed the poverty line rose from 12.1% in 2011 to 20.2% as of 2019.Footnote 18

However, the impact of these practices is not limited to only those workers directly affected by them. On the one hand, such practices imply a reduction in resources for financing social security systems. On the other hand, they reinforce the downward pressure on the working conditions of all salaried workers.

As long as profitability remains at the heart of the organisation’s economic activity, any expectation of change to the current situation is illusory (although labour struggles, such as those of couriers, allow some partial victories). The generalisation of labour precariousness is, after all, the result of the objective needs of capital: in no case can precariousness be considered a merely conjectural phenomenon, much less an error in the management of economic policy, which simply obeys the need for driving down wage costs.

Funding statement

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Xabier Arrizabalo Montoro ([email protected]) holds a PhD in Economics (Complutense University of Madrid, UCM), a Master’s Degree in Planning, Public Policies and Development (CEPAL-ILPES, United Nations, Santiago de Chile), a degree in Sociology (UCM), and a degree in Economics (UCM). A tenured Professor at UCM since 1993, Director of the Instituto Marxista de Economía (IME) since 2014 and Co-Director of Research Group in Political Economy Capitalism and Uneven Development. Director of Continuous Training Degree Critical Analysis of Capitalism: Marxist Method and His Application to the Research of Current Global Economy (UCM). Xabier is the author of many publications, in particular the book Capitalism and World Economy (two editions in Spanish, one in French, and soon in English and Portuguese). He is also a participant in many international congresses and other academic activities across many universities around the world.

Mario del Rosal Crespo ([email protected]) holds a PhD in Economics (Complutense University of Madrid, UCM) and a Degree in Politics (National University if Distance Education, UNED). He is Professor at the UCM. Author of several articles and chapters about the European economy, Marxist economics, and monetary theory. He is a researcher at the Instituto Marxista de Economía.

Francisco Javier Murillo Arroyo ([email protected]) holds a PhD in Economics (Complutense University of Madrid, UCM), and he is Professor at UCM. Author of the book Marxist Analysis of the ‘Spanish miracle’ (2019, Madrid: Maia) and several articles about income distribution and wages. He is a researcher at the Instituto Marxista de Economía.