ON LIBERTY AND CRIME

‘The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.’

The above text is Mill's harm principle from the classic essay On Liberty by John Stuart Mill, published in 1859. We would argue it remains the standard by which we can judge whether any intervention by the state over an individual's liberty is ethically just.

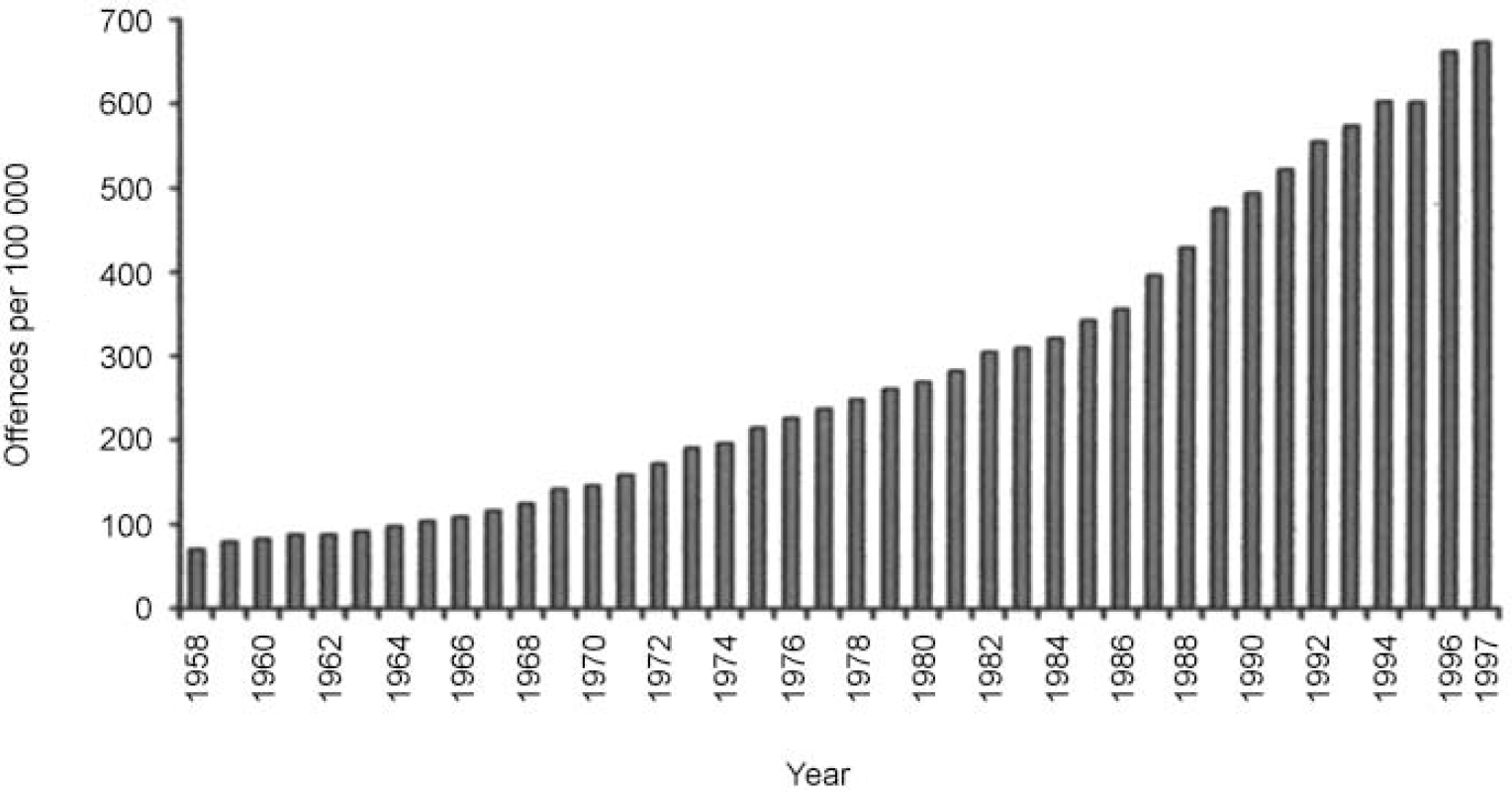

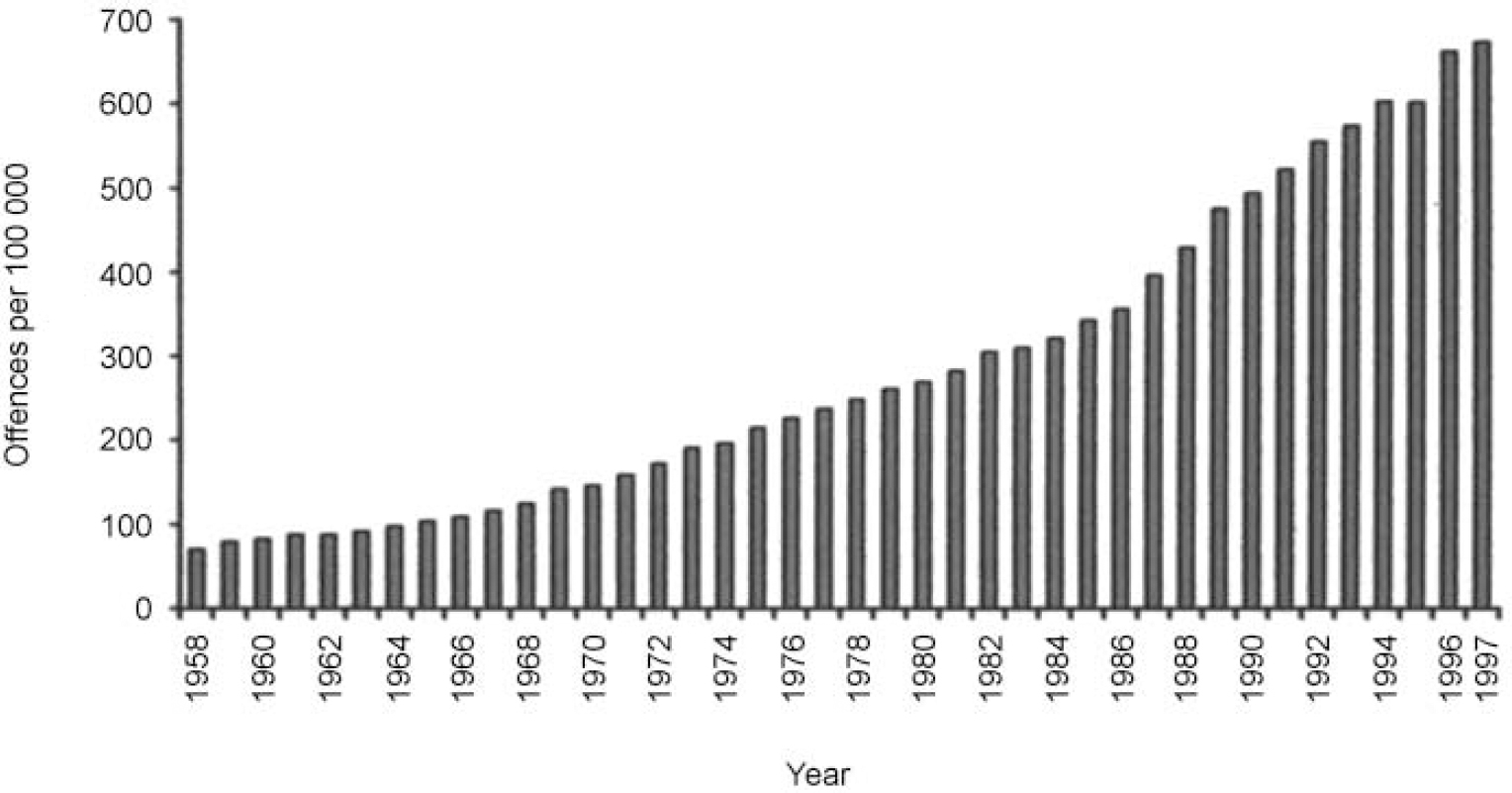

We are of the opinion that the state has grounds and urgent needs to intervene over the levels of violent crime in our communities. In England and Wales, recorded violent crime has been rising consistently for over 40 years (Reference TaylorTaylor, 1998; Fig. 1). The estimated cost of this violent crime in 1999 was £16.8 billion (Reference Brand and PriceBrand & Price, 2000). Alcohol misuse is estimated to contribute to 40% of violent crime, 78% of assaults and 88% of criminal damage (Reference DeehanDeehan, 1999), and alcohol is a contributing factor in approximately 50% of homicides (Reference Appleby, Shaw and SherrattAppleby et al, 2001). Recognition is also growing that crime committed by those who are mentally ill is commonly attributable to comorbid substance misuse, particularly of alcohol (Reference Rasanen, Tiihonen and IsohanniRasanen et al, 1998; Reference SoykaSoyka, 2000; Reference MullenMullen, 2000).

Fig. 1 Trend in recorded violent crime over 40 years in England and Wales. There were 69 recorded violent crimes per 100 000 people in the population in 1958; this figure rose to 674 in 1997. (From Reference TaylorTaylor, 1998, with permission.)

How can we efficiently and ethically reduce this violence?

We would argue that violent crime can be substantially tackled by making alcohol control the priority. We propose a revolutionary form of alcohol control, which would reduce levels of serious violent crime, reduce the prison population, be consistent with Mill's harm principle and be cost-effective.

SELECTIVE PROHIBITION

The system of selective prohibition that we propose is based on the use of identity cards to control access to alcohol. Such cards would allow identification of individuals who would be eligible to purchase alcohol and would allow people who have committed crimes while intoxicated to be effectively prohibited from doing so. Universal card carriage and acceptance would be required for such a practical yet controversial scheme to work. Plastic is already the preferred mode of payment and the addition of an identity card would be a minor inconvenience to the law-abiding majority. Vigorous policing of retail outlets with severe civil penalties would become practicable, while at the same time, criminals whose offending is related to consumption of alcohol would have their licence to buy alcohol either temporarily or permanently withdrawn. The aim is that the use of civil penalties as a therapeutic sanction at an early stage will help prevent worse crimes being committed which necessitate criminal penalties. Civil penalties are much less costly both to the individual and society. A powerful message of deterrence would be sent to those who might offend, and to the public who would become better informed of the risks of intoxication. People who tried to evade their prohibition or who committed further crimes while intoxicated would suffer proportionately more severe penalties. Similarly, penalties would apply to individuals who chose to assist their banned colleagues in purchasing alcohol.

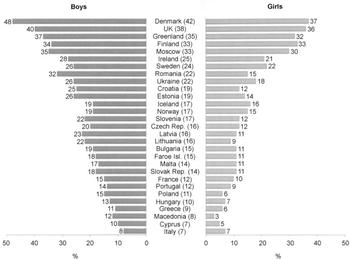

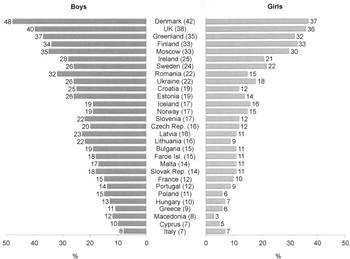

Besides criminals, the second group to be prohibited compulsorily from purchasing alcohol would be children. They should already be prohibited under the existing licensing laws. Evidence from the recent European School Survey Project (Reference Hibell, Andersson and AhlströmHibell et al, 2000; World Health Organization, 2001) on alcohol and other drugs suggests otherwise, with British children reporting almost the highest rate of misuse of alcohol in Europe (Fig. 2). To protect children, there is a temptation to make identity cards compulsory just for young people who are at the outset of their drinking career. This proposal is ethically unsound, however, as the responsibility should lie with the adult not the child. Children can only be protected effectively under a larger comprehensive scheme that involves the whole community and is rigorously enforced.

Fig. 2 Proportion of boys and girls in Europe who have been drunk at the age of 13 years or younger (means in parentheses). (From Reference Hibell, Andersson and AhlströmHibell et al, 2000, with permission.)

How could selective prohibition protect the mentally ill?

In addition to compulsory prohibition for the above groups, there would also be a voluntary scheme. People who are alcohol-dependent and who cannot cope with the unfettered access to alcohol in our society could elect to have their identity cards revoked. Impulsive purchase of alcohol and then fear of severe withdrawal are potent factors in their relapse into uncontrolled drinking. The altruism of the population in carrying identity cards would be interpreted as support and encouragement.

Those considered to be at risk of self-harm might also benefit from voluntary revocation. Heavy alcohol intake commonly accompanies periods of emotional distress and may precipitate acts of deliberate self-harm. Emotionally distressed individuals who can identify themselves as losing control might be willing to contemplate voluntary revocation as means of self-protection. In this way perhaps something could be achieved with the 76% of people committing suicide who have had no contact with mental health services in the year prior to their death (Reference Appleby, Shaw and SherrattAppleby et al, 2001).

Is this not the infamous ‘Prohibition’ which was tried unsuccessfully in the USA in the 1920s?

Selective prohibition is a highly refined version of prohibition, which should avoid some of the flaws of that ‘noble experiment’. With only a small proportion of the adult population prohibited at any one time, it is unlikely that a major black market in alcohol would develop. With society understanding the rationale for the exclusion of individuals, and seeing a real and substantial reduction in crime, such a scheme would hopefully become popular among the majority. Few would seek to undermine its operation.

Has anyone tried selective prohibition before?

An alternative to prohibition occurred in Sweden from the early 1920s to 1955. Ivan Bratt, a Swedish physician, devised a form of individual control for alcohol. It was based on a ration system where individuals were given an allowance of 4 litres of alcohol a month. Individuals had to buy their alcohol from only one outlet. If they offended while intoxicated, they could have their ration reduced or stopped. It was very successful in reducing overall consumption, admissions with medical problems related to alcohol, violent crime (by 60%), public drunkenness (by 70%) and the overall prison population. It was abandoned in favour of a system of higher taxation, which has not been so protective (Reference NycanderNycander, 1998).

Bratt's model of alcohol control is better in many ways than our current poorly integrated and enforced model. Selective prohibition would, we hope, have the efficacy of the Bratt model of combating crime, while the use of new technology would ensure greater freedom, making it more acceptable to the public. There would be no element of rationing of alcohol or of limiting the drinker to one vendor.

Who would oppose selective prohibition?

Selective prohibition is designed to maximise the protection of the weakest groups in society, minimise victimisation, and secure the best chances of rehabilitation for offenders. This high ethical standard would limit the challenge from possible opponents. Certainly, there is no incompatibility with European human rights legislation, with its emphasis on public safety and the due process of law.

Civil liberties groups might reflexively oppose the introduction of selective prohibition. We appreciate their real fears that any new power can be abused. This, however, is an argument against abuse, not new laws or an extension of the population's responsibilities. We would welcome their involvement in the practical design of selective prohibition and the introduction of any safeguards. We would suggest the involvement of an independent body to supervise the operation of the scheme in a similar manner to the Mental Health Act Commission. If civil rights groups could not be reconciled to the process, then their opposition might be counterbalanced by support from organisations who assist the many victims of alcohol misuse. Opposition from the retail industry, leisure industry and the drinks industry might be formidable. They would need to reassess their commercial interests, as selective prohibition would lead to an increase in their responsibilities, with the prospect of increased running and structural costs combined with decreased revenues.

Public opinion with its diverse sources might have ambivalent feelings towards selective prohibition. On the one hand it appeals strongly to the desire to punish wrongdoers and protect children; on the other, it confronts society painfully about its ‘favourite drug’. Public opinion cannot be guaranteed neither to fall firmly in support of selective prohibition nor against it. Hopefully, some sensible debate will be possible.

In summary, selective prohibition is ethically and scientifically sound, economically attractive, technically demanding and politically courageous. We appreciate that this is a controversial proposal, and for those who object to the views expressed in this editorial, we close with some more words from John Stuart Mill.

‘The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.’

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.