Reduced enjoyment of pleasant experiences and increased impact of negative emotions are observed clinically in depression and in borderline personality disorder (BPD). Reference Reed, Fitzmaurice and Zanarini1 Surprisingly, previous laboratory studies do not support a link between depression and reduced pleasantness ratings to biological rewards, such as sucrose solutions (for example see Swiecicki et al Reference Swiecicki, Zatorski, Bzinkowska, Sienkiewicz-Jarosz, Szyndler and Scinska2 ). However, patients with depression could be more sensitive to negative primary inputs. Reference Leppanen3 Few studies have used aversive stimuli in the evaluation of taste in depression, and no studies have been carried out to evaluate hedonic ratings of tastes in BPD in spite of clinically observable aberrant emotional processing and increased state and trait disgust. Reference Schienle, Haas-Krammer, Schoggl, Kapfhammer and Ille4 We hypothesised that patients with BPD and depression would differ from healthy controls in their pleasantness and disgust ratings to positive and especially negative taste stimuli.

Method

A total of 29 women with DSM-IV 5 major depressive disorder, 17 women with DSM-IV BPD and 27 female healthy controls took part in the study, which was approved by the Cambridgeshire 4 National Health Service research ethics committee; all participants provided written informed consent. Additional details, including statistical data, are provided in the online supplement. Evaluation of taste consisted of participants taking a sip, but not swallowing, from a cup with 10 ml of orange juice, quinine dihydrochloride at 0.006 mol/L or water. Participants had to maintain the liquid in the mouth for 5 s, rate the disgust and pleasantness produced using two visual scales (online Fig. DS1) and rinse their mouths with water. Order of liquids was counterbalanced across participants. Clinical evaluation was completed prior to the taste experiment. Statistical analysis (see online supplement for details) aimed to evaluate the association between taste disgust and disgust as measured using two clinical rating scales: the Self-Disgust Scale (SDS) Reference Overton, Markland, Taggart, Bagshaw and Simpson6 and the Disgust Scale Revised (DSR). Reference Olatunji, Williams, Tolin, Abramowitz, Sawchuk and Lohr7

Results

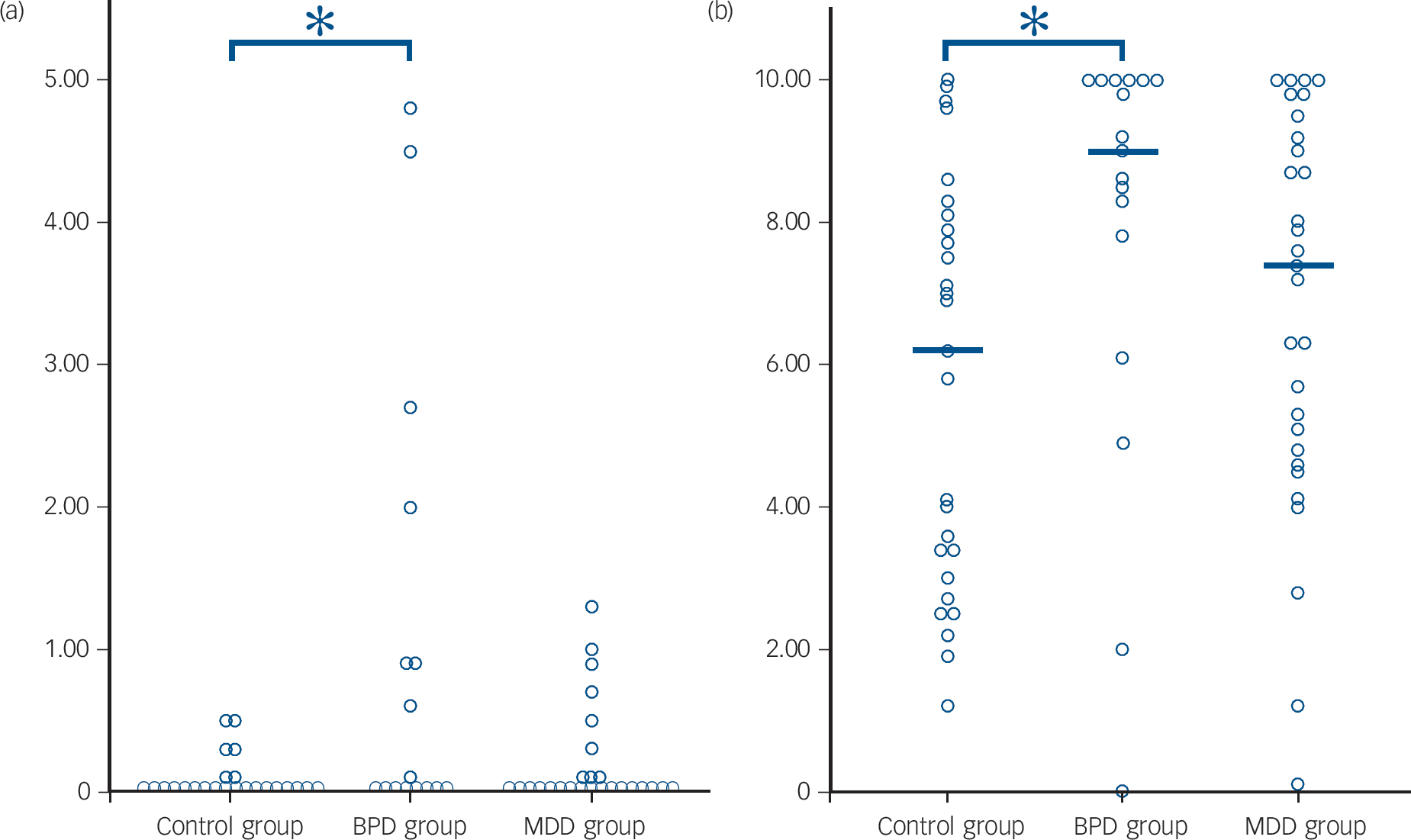

Overall differences between the three conditions in pleasantness and disgust ratings followed predictions across all participants. Quinine was highly unpleasant and disgusting, juice was highly pleasant and not disgusting and water was neither pleasant nor disgusting. Pleasantness and disgust ratings correlations were all significant. Regarding differences between groups, the BPD group rated both quinine and juice (but not water) as more unpleasant and disgusting than the control group, but no differences were found between the depression and control groups (all P<0.05; see online Tables DS8 and DS9, and Fig. 1). Increased self-disgust was significantly correlated (Spearman's ρ = 0.5) with greater disgust ratings after the intake of orange juice in the BPD group (Table DS10). However, disgust propensity did not correlate with ratings in this group and all correlations were non-significant in the depression group.

Fig. 1 Scatter plot with the (a) juice and (b) quinine disgust ratings stratified by group.

The horizontal brackets with asterisks indicate significant group differences and the horizontal lines group medians. BPD, borderline personality disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Discussion

We found that in the BPD group there were abnormal pleasantness and disgust ratings after the intake of biological stimuli, whereas no differences between the depression and control groups were found. Our findings indicate that the hedonic experience of both positive and negative taste stimuli is negatively biased in BPD. This novel result is in line with clinical findings in the disorder, as people with BPD report more dysphoric and less positive affective cognitive states. Reference Reed, Fitzmaurice and Zanarini1 Current diagnostic criteria for the disorder include affective instability, recurrent self-threatening behaviours and chronic feelings of emptiness, all of which could be related to negative perceptions of the environment.

The lack of evidence for a differential effect in the case of depression is also in line with most of the existing literature on enjoyment of pleasant tastes; Reference Swiecicki, Zatorski, Bzinkowska, Sienkiewicz-Jarosz, Szyndler and Scinska2 however, our study also shows that there were no differences between the depression group and the control group in evaluation of a disgusting taste. A limitation of our study and the prior depression studies is that sample sizes were small; hence, either there is no true difference in the ratings for chemosensory stimuli between people with depression and controls or the effect is small, suggesting that the basis of anhedonia reported in depression is complex. For example, it could be that clinically observed anhedonia in depression is primarily related to social anhedonia. Alternatively, clinical assessments of anhedonia may confound motivational, anticipatory and mnemonic aspects of enjoyment with consummatory ‘in the moment’ pleasure; the latter is assayed by our laboratory taste task and may be comparatively intact in depression. Reference Dillon, Rosso, Pechtel, Killgore, Rauch and Pizzagalli8

In the BPD group, questionnaire-measured self-disgust, but not disgust propensity, correlated with laboratory-rated disgust to juice stimuli. Self-disgust indicates a context-free negative evaluation of the self (shame feelings) and also negative views about one's actions (guilt), Reference Overton, Markland, Taggart, Bagshaw and Simpson6 and it is greatly enhanced in BPD. Self-disgust may be felt as an embodied experience instead of an abstract sensation, to the point of producing negative physical sensations such as nausea, and is often triggered by external events. Reference Powell, Overton and Simpson9 Our finding of an association between self-disgust and juice-disgust indicates close links between sensory processing and self-identity in BPD, and may suggest that basic physiological disturbances play a role in the origins of self-disgust in this disorder. Previous research indicates that self-disgust is correlated with overall symptom severity in BPD and eating disorders, Reference Ille, Schoggl, Kapfhammer, Arendasy, Sommer and Schienle10 which could indicate similar mechanisms within the two disorders. Reference Zanarini, Reichman, Frankenburg, Reich and Fitzmaurice11 We speculate that in BPD self-disgust is so heightened that it may impair the enjoyment of stimuli that are ordinarily considered as pleasant. Alternatively, a fundamental abnormality in processing external sensory stimuli may contribute to a negative sense of self in BPD. The less positive ratings could also be related to other group-specific factors, such as an increased history of trauma in the BPD group. Reference Schienle, Haas-Krammer, Schoggl, Kapfhammer and Ille4,Reference Rusch, Schulz, Valerius, Steil, Bohus and Schmahl12 Our results emphasise the significance of disgust – both of the self and of external stimuli – in BPD, and highlight a role for assessment of disgust in the diagnosis and management of this condition. Reference Schienle, Haas-Krammer, Schoggl, Kapfhammer and Ille4

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.