Introduction

In this article, we explore the incentives and deterrents to long-term care (LTC) supply in two local markets in England. The supply of LTC is of increasing relevance in many countries because of the interwoven issues of rising demand from an ageing population, insufficient workforce and the crossroads the LTC market lies on between public and private sectors (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Llena-Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011; Gori et al., Reference Gori, Barbabella, Campbell, Ikegami, d’Amico, Holder, Ishibashi, Johansson, Komisar, Theobald, Gori, Fernandez and Wittenberg2015). Widespread reform of LTC has occurred in many countries, including England, largely in an attempt to address the challenges faced with an increasing demand for services (Pavolini and Ranci, Reference Pavolini and Ranci2008).

In England, privatisation of LTC delivery occurred during the 1980s and throughout the 1990s, which led to a growth in care home supply from the independent sector (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Hardy and Forder2001). Care home supply has remained fairly stable over the last decade, with around 450,000 beds available for the elderly in the LTC sector (LaingBuisson, 2015). However, there has been a fall in beds over time relative to the elderly population and the availability of care home places varies across the country, due to local need and socioeconomic characteristics, supply conditions (e.g. labour supply), and local government policy (Allan and Nizalova, Reference Allan and Nizalova2020). Despite this, the care homes market remains competitive overall, with most of the population within range of a selection of care homes (Forder and Allan, Reference Forder and Allan2014; Competition and Markets Authority, 2017).

Following the growth in private sector delivery of care home support, there was a rapid growth in private domiciliary care (or home care) supply from the 1990s as policy moved towards the use of less costly care at home and in the community (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Hardy and Forder2001). This growth in supply has been maintained over time as policy continues to promote prevention and living well in the community (Department of Health and Social Care, 2018). In 2018 there were over 400,000 care workers estimated to be providing LTC in the home to over 600,000 individuals in England (Skills for Care, 2019; UK Home Care Association, Reference Home Care Association2019).

Despite the rapid increase in independent sector supply, there is currently limited research into the factors that influence LTC supply in England and, generally, these examine only one form of care. For example, Glendinning (Reference Glendinning2012) discussed the implications of increased marketization and policy changes for domiciliary care providers and Bottery (Reference Bottery2018) drew together research from three separate studies analysing domiciliary care supply in England through interviews with stakeholders. Care home supply research is either older (e.g. Netten et al., Reference Netten, Williams and Darton2005) or more quantitative in nature (e.g. Forder and Allan, Reference Forder and Allan2014). Additionally, research has examined LTC supply from the policy (e.g. Needham et al., Reference Needham, Hall, Allen, Burn, Mangan and Henwood2018; Glasby et al., Reference Glasby, Zhang, Bennett and Hall2020) and employee perspective (e.g. Hussein, Reference Hussein2017; Read and Fenge, Reference Read and Fenge2019).

It is in this context that we report the findings from a study assessing the incentives and deterrents to LTC supply for two local authorities (LAs) in England using stakeholder interviews. The study was part of a wider project assessing regional market dynamics in LTC in England, with an overall aim of gaining a better understanding of factors that affect changes in LTC supply in local markets. A second study assessed local care home supply across the country over time and quantitatively analysed the relationship between local public spending and care home supply (Allan and Nizalova, Reference Allan and Nizalova2020). Whilst the study we are reporting on included extra care housing (see Allan and Darton, Reference Allan and Darton2020), in this article we focus on the two primary forms of LTC, domiciliary care and residential care homes (i.e. those with and without nursing care).

Methods

The LAs selected for the study were Bristol and Kent. These were chosen because: the LAs have different government structures (Bristol is a unitary authority and Kent is a two-tiered county council) and differ in geographical size (Bristol is a large city in South West England, Kent a large county in South East England); both LAs vary in their socioeconomic characteristics, with areas of both high wealth and deprivation; and for pragmatic cost and time considerations.

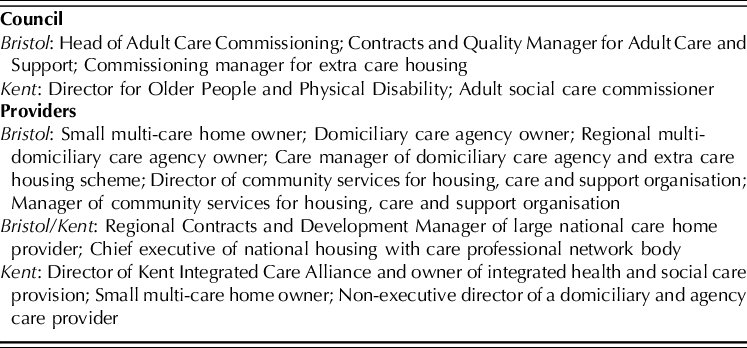

Following ethical approval for the project from the University of Kent SRC ethical research panel (SRCEA 203), we sought to interview LA and provider stakeholders. Initially recruitment focussed on council representatives from both authorities, who were contacted and recruited by e-mail, before contacting providers via council representatives. In Bristol, providers were recruited via an e-mail advert and in Kent we recruited interviewees from the Kent Integrated Care Alliance (KICA). The interviewees included commissioners and directors of adult social care in the relevant councils as well as owners and managers of different forms of LTC (see Table 1).

Table 1 List of interview participants

We interviewed sixteen participants between October and December 2018. The interviews were face-to-face and lasted approximately one hour. Interviews were recorded following appropriate consent from interviewees, and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were semi-structured using a topic guide with key themes, which was used as a framework for discussion. The guide was informed both by the relevant LA market position statements (MPS) and taking into account the views on priorities for the project from two lay representatives.

The authors conducted the interviews and data analysis throughout. Given the relatively small number of interviews, the themes and links between the themes were explored through reading and re-reading of the transcripts and discussions between the authors on their perspectives of the interviews. Included in this article are data from the interviews, with quotations labelled according to the stakeholder’s role in the market.

Local market context

In England, demand for LTC of the elderly comes from two main sources: private, self-funders, who fund their own care, and public funding through LAs for those that cannot afford to support fully their care requirements (and meet need requirements), with small proportions funded by NHS and charities (Care Quality Commission, 2019). Price is not regulated and varies considerably by region and funding type – self-funders pay a premium compared to those supported by LA-funding (Competition and Markets Authority, 2017; UK Home Care Association, Reference Home Care Association2019). Quality of care is regulated by the Care Quality Commission (CQC), the national health and social care regulator.

From the relevant MPS, the broad approach of both LAs, as elsewhere, is to reduce reliance on care homes through supporting people to live in their own homes and by encouraging the development of extra care housing (Kent County Council, 2014; 2016; Bristol City Council, 2018). Bristol City Council (BCC) and Kent County Council (KCC) supported around 5,500 and 34,000 adults, respectively (Kent County Council, 2016; Bristol City Council, 2018). From CQC data, there were fifty-six domiciliary care agencies registered in Bristol and 227 in Kent. Bristol had 113 care homes (sixty-seven of these registered to deliver services to older people) and Kent 575 (362). BCC contracted ‘main’ and ‘secondary’ providers of home care, whereas KCC had nineteen (initially twenty-three) contracted providers for 85 per cent of services, with the remaining services contracted on an individual basis from fifty other providers (Kent County Council, 2016; Bristol City Council, 2018). Bristol’s MPS outlined that there were problems with sourcing supply for domiciliary care, and that the council worked with ninety-one care homes, some of these outside their boundaries. KCC outlined that there was an oversupply/undersupply of residential and nursing care in different parts of the county (Kent County Council, 2014).

The findings from the interviews are reported in three main topic areas: demand, stakeholder relationships, and staffing.

Demand

Demand for care home places close to previous residence or family kept markets fairly small in geographical area, i.e. limited to specific parts of Bristol and Kent. For example, a provider in Bristol had little demand for places from South Gloucestershire (the local authority which immediately borders Bristol to the north). Similarly, the domiciliary care providers we interviewed generally served small geographic markets, although some did work across Bristol or wider parts of Kent. Given population demographics, demand for services is high and projected to increase in both LAs. This has two main implications for the demand for services, particularly from those requiring LA support. First, as was discussed by providers of both forms of LTC, the level of needs, particularly of those supported by public-funding, has risen greatly over time. For care homes, this has potential implications for occupancy from reduced length of stay and costs, e.g. increased staffing. For domiciliary care, increased needs have to be met using the same amount of time on visits. Services which had previously been domiciliary care and home help (shopping, cleaning, etc.) were generally now only the former.

…the sort of people that are coming to residential care these days would without a doubt have been [in] nursing care fifteen years ago, without a doubt. (Small multi-care home owner, Kent)

Second, the price paid by the councils was usually lower than was paid by self-funders. Virtually all providers supported some level of LA-funded clients and there was genuine concern around viability for some of the providers if fees paid by LAs were not increased. In Bristol, a provider suggested that care home fees of those paying privately could be double that paid by the council, whilst domiciliary care would cost a private payer around £4 an hour more. In Kent, providers interviewed suggested that the fees paid by the council were linked to supply in an area.

Further issues surrounded publicly-funded demand. There was general preference from interviewed providers for private payers due to price differences and also increased administrative burden and delays in payments.

If you’re dealing with a private payer…you get your fee, they get their service and it’s quite straight forward. But for Local Authority funded payers, it’s so much admin… (Small multi-care home owner, Bristol)

For prospective demand, one provider in Bristol felt that third party top-ups (family members contributing further to ‘top-up’ LA support) were discouraged; and in Kent it was alluded to by a provider that prospective clients received a list of care homes ordered in ascending price. Additionally, a single price was seen as problematic by one provider as care homes may have different sized rooms and amenities within them.

Stakeholder relationships

The relationships between stakeholders were obviously important in both markets, with providers often mentioning that their expertise could be utilised through partnership.

Councils

The relationships between providers and councils were seen to be moving in opposite directions in each LA. In Kent, it was felt by KCC and providers that the relationship was improving, with greater consultation and a better understanding of the private sector.

…we’re working more closely together, so an example being with our Care and Support in the Home tender which has gone out recently…we developed the specification and we shared it with the market and we got their feedback. (Adult social care commissioner, Kent)

I do think our Local Authority have got the vision to ensure that things are done differently, I think we’ve got good leadership now…[that] understands really well what the private market bring to the table. (Owner of Integrated health and social care provision, Kent)

Whereas, in Bristol, partnership arrangements had been abandoned and providers felt there was no longer a forum in which to discuss matters jointly. Domiciliary care providers had little opportunity to meet colleagues, and across provision types it was felt that there was a preference for the LA to work with non-profit providers.

…we’re in a period of trying to re-engage and develop [a] different kind of more collaborative relationship with all of our markets, and I guess it would be honest to say it’s a kind of slightly mixed bag… (Head of Adult Care Commissioning, Bristol)

I think they thought we were just keeping all the money, but we didn’t, we used that [higher funding from LA] to be able to raise the standards and increase the levels of staff to cater for the levels of need. (Small multi-care home owner, Bristol)

Across the two LAs, there was concern about levels of funding and planning around funding. For example, KCC was considering introducing increased funding to help alleviate pressure on the health system in the winter, but domiciliary care providers suggested this assumed they were able to simply expand and contract staffing as necessary. The level of funding of domiciliary care could imply that staff should be paid below the National Living Wage (NLW, a national minimum wage rate for those aged twenty-three and over). Contracts were often for time and task, which meant there was little to no allowance for travel time, and this was a greater issue in more rural areas. Generally, although providers recognised LA financial constraints, the day-to-day pressures on their services made them question the direction of policy. Enabling residents to control their own lives and care was seen primarily as cost-cutting in response to financial imperatives.

CQC

The relationship between providers and the CQC was discussed in terms of the increased cost to regulation – fees for domiciliary care providers especially had risen sharply – and particularly the quality rating system, where a provider receives an overall rating of ‘Inadequate’, ‘Requires improvement’, ‘Good’ or ‘Outstanding’. For care homes, providers still saw the visit to their home as the key element for prospective clients, and across both forms of LTC provision there was belief that many prospective clients were still unaware of CQC.

…when we’ve perhaps had ‘Requires improvement’ on an inspection report…you think…is that going to affect us? But realistically, it doesn’t seem to have as big an impact as I would even expect it to. (Small multi-care home owner, Bristol)

There was some feeling that this lack of impact of the rating may depend on location and levels of competition. An example was given of a care home in rural Kent that seemed happy to have a ‘Requires improvement’ rating as they could still charge self-funding prices and had no vacancies.

However, some providers did have concerns around the four-tier system of the quality ratings and the implications this could have for demand.

The difference between ‘Good’ and ‘Requires improvement’ to the human brain…is significant. If I was helping my dad to be placed in a care home and I saw ‘Requires improvement’, I would think that is well below average, well below standard. (Regional Contracts and Development Manager of large national care home provider, Bristol/Kent)

There were also worries across different LTC services about how providers were assessed for their ratings. A few examples were given of receiving a lower rating from individual cases of personal error, where a mistake does not reflect the overall service.

…because we didn’t do that on the paper [for] the one single client we were rated down to requiring improvement in both ‘Safe’ and also ‘Well-led’. (Domiciliary care agency owner, Bristol)

Staffing

A key priority noted by providers was the maintenance of a core of longstanding staff. The majority of care staff was female, often with family commitments. This had a challenging impact on supply of care, with daily and seasonal variability in work availability. For domiciliary care in particular, the busiest time of day was 7:00–9:00, but staff with children had difficulty in finding childcare arrangements during this period. Similarly, school holidays presented problems, whilst several providers further indicated that there was no point in advertising for staff in the pre-Christmas period.

Location could also impact on staffing availability. Within urban areas, domiciliary care staff tended to live relatively close to their clients, meaning that some could operate without personal transport. Where care staff lived close to their clients it was possible to schedule visits quite efficiently, although confidentiality issues might prevent wanting to provide care in their own community. However, for both LAs there were providers that required potential staff to have their own transport due to their location, serving more dispersed areas or areas with limited public transport.

These time and seasonality issues naturally put pressure on the aforementioned core staff that could be relied upon to be available to work the difficult periods, and a provider in Kent noted that this can lead to burnout and losing staff, particularly as providers could not pay more to reflect this effort.

We put a lot more pressure…on the good staff, you know, you only ever ring the good staff on a Friday night at seven o’clock because they’re the ones that are going to do it. You can only do that for so long. (Owner of Integrated health and LTC provision, Kent)

For the larger county of Kent, there were distinct staffing issues in different parts of the county. For example, there was higher unemployment and socio-economic deprivation in certain areas (e.g. the Thanet district). In these areas, there was a lack of appropriate staff to open nursing homes given LA budget constraints and lack of self-fund demand, but there was strong supply of staff for domiciliary care. Further, in West Kent there were issues with staff leaving to go to jobs in neighbouring areas (London, Medway). In areas of full employment it could be very difficult to attract potential employees in to LTC. This could limit the available pool of potential workers, something which domiciliary care providers linked to any potential growth plans.

The other thing is the supply of care staff. [W]e’re a good employer, and therefore we don’t have a huge amount of difficulty in recruiting, but I’m very conscious there’s a fixed pool of people in any location who work in care and are willing to do so. (Regional multi-domiciliary care agency owner, Bristol)

Overall, having an appropriate level of staff was a constant issue for virtually all providers, with high levels of staff turnover, particularly within the first year of employment.

The majority of care staff in both local authorities were from the UK. The extent to which services employed non-UK staff varied between areas and there was considerable uncertainty about the future availability of non-UK staff in the light of Brexit. Providers were also uncertain about the possibility of expanding the employment of UK-based care staff given a lack of supply.

Support for staff was recognised as essential. Training and promotion from care staff positions to supervisory and management roles was regarded as an important means of valuing staff, as well as ensuring that trained senior staff were available to step in for any staff shortages. Providers were willing to support their staff in obtaining relevant qualifications and a number were explicit about encouraging staff to seek career advancement outside the provider organisation if that was what the person wanted. However, some providers were becoming concerned about the costs of providing training and qualifications.

Providers felt that pay rates they offered were constrained by the contractual rates offered by the LAs. In Kent, recruitment issues in domiciliary care had been helped to some extent by KCC putting money in to specifically increase pay for workers, whilst BCC had previously had problems with the supply of domiciliary care because of low hourly rates.

It all depends on how forthcoming the council is…that’s essentially where the problem is, we have to be able to pay the staff a wage that is showing that we value their work, but also that enables them to pay their bills. (Domiciliary care agency owner, Bristol)

Providers paid at least the NLW, or slightly more if they were able to do so. Some care staff moved from job to job quite frequently, incentivised by small increases in pay. Providers recognised the difficult nature of care work and that they needed to pay higher salaries for more experienced and more senior staff, although there was some concern that pay differentials were reduced due to payment of the NLW. For example, a care home provider in Bristol now paid the same wage for carers irrespective of qualifications. However, qualifications were still seen to stand staff in good stead for future progression (e.g. to senior carer).

Discussion

This article has assessed the incentives and deterrents to the supply of LTC in two LAs in England through qualitative analysis of interviews with LA and provider representatives. The two LAs had different governmental and geographical structures which enabled the study to explore differences and similarities facing LAs more generally. Additionally, by interviewing stakeholders from both care homes and domiciliary care, we could assess differences across LTC type. Our findings suggest that demand, staffing and relationships between stakeholders are important factors in the effective provision of LTC. The issues facing each LA were broadly similar, although naturally the implications of these can be stronger for the larger LA, e.g. lack of qualified staff in certain areas.

The study also found that, generally, the issues facing different LTC provider types were similar and we therefore can draw out important areas of concern that may impact on all forms of LTC supply across England. On the demand side, the ageing population would appear positive for future supply. However, demand for (different forms of) LTC will vary across England affecting what forms of care are available locally. A further issue is public funding for those unable to fully afford their own care. In concurrence with the ageing population, the last ten years has seen public funding austerity, where funds to LAs from central government have been cut, and LTC budgets have fallen in real terms in consequence (Glasby et al., Reference Glasby, Zhang, Bennett and Hall2020). This is then exacerbated by LAs’ strong market position as dominant purchasers where they can push down the price paid for services (Allan and Nizalova, Reference Allan and Nizalova2020; Allan et al., Reference Allan, Gousia and Forder2021). This concern for LTC supply is not new, however (e.g. Netten et al., Reference Netten, Williams and Darton2005). A more recent concern is the market shaping responsibilities LAs now have, which will also impact greatly on available forms of LTC supply (Needham et al., Reference Needham, Hall, Allen, Burn, Mangan and Henwood2018). Added together, these factors mean that LAs’ relationships with providers will be crucial. The findings from this study support the importance of these relationships, with providers suggesting problems in communication, a lack of co-production in the development of tendering processes and a lack of trust of for-profit enterprises in Bristol that put added pressure on suppliers. The effect of these pressures may have played some role in the issues the council faced in sourcing domiciliary care supply.

Further, we found concerns over the cost to providers of CQC regulation and particularly with the rating system, which can have unexpected effects on providers (Rendel et al., Reference Rendel, Crawley and Ballard2015). The aim of increasing consumer information is juxtaposed with the four-tier system of rating and the evidence from some stakeholders of ‘small’ errors causing lower ratings. If this were widespread, it would suggest information is not clear for consumers and that gains from the rating system could be minimal. That there may be differences in the effect of the rating system on providers by location is also a potential supply concern. However, a positive relationship has been found between CQC quality ratings and both care home viability and resident outcomes (Allan and Forder, Reference Allan and Forder2015; Towers et al., Reference Towers, Palmer, Smith, Collins and Allan2019), suggesting that the system works broadly as intended. Overall, our findings suggest a tension between what providers expect from a rating system and the current CQC system which could be explored further in future research.

Inevitably, local LTC supply is highly dependent on staffing. Staff are the vital component in LTC, providing care to those requiring it in a co-productive manner, with strong caring motives and interpersonal skills (Hussein, Reference Hussein2017). Research evidence supports that staff and staffing factors can improve quality in LTC (e.g. Dellefield et al., Reference Dellefield, Castle, McGilton and Spilsbury2015; Allan and Vadean, Reference Allan and Vadean2021). We have found that ensuring adequate staffing is an ongoing issue. Maintaining supply is both time and seasonality dependent for many of the providers we interviewed, particularly in domiciliary care. Further, recruitment is a continuous process with high levels of staff turnover. The UK’s withdrawal from the EU was a concern for the provider stakeholders we interviewed, which supports recent findings (Read and Fenge, Reference Read and Fenge2019). Some providers interviewed saw LAs as only viewing supply issues in financial terms, thinking that putting extra funds into the system will automatically raise supply. The extent to which this would happen is open to question given the staffing issues raised here.

We also found that pay, training and progression were crucial for LTC staff. The introduction of the NLW has increased pay, which is a positive, but it has also meant that there has been a compression in wages, with more senior staff being paid a smaller premium (Vadean and Allan, Reference Vadean and Allan2021). Providers do not have the ability to increase pay of their own volition given the funding they receive from LAs. This is an important point – many firms want to remunerate and support their staff in line with their efforts. This seems at odds with what could be occurring in a market system, where higher quality services could pay better wages, especially given the consistent issues with staff turnover and job vacancies throughout the country (Skills for Care, 2019).

Limitations

This was a small study within a larger project exploring regional market dynamics, which limited the scope of the research. We did not interview service users, individual employers of carers, personal assistants, nor representatives of CQC or large provider organisations, e.g. Care England. Given the size of the study, only a limited number of stakeholders were involved and we were unable to fully assess any differences between private and not-for-profit providers. The small sample size added to the fact that providers that took part in interviews were those that expressed an interest meant the findings may not represent the views of all providers in the two markets studied. Finally, there were only two LAs studied in the project, potentially limiting national applicability. However, overall, the themes and problems that arose from the interviews matched issues also raised at national level, e.g. payment for travel time, and were in line with other studies (e.g. Bottery, Reference Bottery2018). This would suggest that study findings are of value at both local market and national level.

As has been seen with the recent Covid-19 pandemic, the availability of LTC across the country is crucial for the health and LTC outcomes of the population. The pandemic has resulted in many stakeholders expressing increased concerns around the viability of LTC markets in England (ADASS, 2020; Bottery, Reference Bottery2020). This research took place prior to the onset of the pandemic and future research would be needed to assess the effects this has had on LTC supply.

Conclusion

The supply of LTC in England depends on demand, workforce and policy decisions, and these will play an important part in incentivising or deterring providers. In particular, staff are the vital component and, in a sector with high levels of staff turnover and job vacancies, acknowledging the hard work of the staff with better pay and conditions is likely to be beneficial for the LTC sector. Achieving better pay and conditions for the LTC workforce would require increased public funding, and given ongoing issues such as Covid-19 and Brexit this may be unlikely in the short to medium term.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to all provider and LA representatives that gave their time to be interviewed. The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme (Reference PR-PRU-103/0001 and PR-PRU-1217-21101). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.