1. Introduction

Since the first crystal structure of myoglobin (Kendrew et al. Reference Kendrew, Bodo, Dintzis, Parrish, Wyckoff and Phillips1958), the three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction image of T4 bacteriophage tails by electron microscopy (EM) (De Rosier & Klug, Reference De Rosier and Klug1968), and the solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of proteinase inhibitor IIA (Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Havel and Wuthrich1985), structural biology has made tremendous strides toward revealing intimate atomic level details that guide the function of biological molecules. We live at a time when we know the structures of more than 120 000 (and counting – Source: http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/statistics/holdings.do) biological macromolecules, when we can visualize the inner workings of the ribosome (Ben-Shem et al. Reference Ben-Shem, Garreau DE Loubresse, Melnikov, Jenner, Yusupova and Yusupov2011), or the nucleosome interactions that preserve the integrity and identity of our genome (Luger et al. Reference Luger, Mader, Richmond, Sargent and Richmond1997). At the same time, advances in instrumentation engineering have pushed the frontiers of structural biology methodologies and have allowed experiments and accomplishments that would have been unthinkable 30 years ago. Thus, it is now possible to record high-resolution movies of fast protein motions using X rays (Tenboer et al. Reference Tenboer, Basu, Zatsepin, Pande, Milathianaki, Frank, Hunter, Boutet, Williams, Koglin, Oberthuer, Heymann, Kupitz, Conrad, Coe, Roy-Chowdhury, Weierstall, James, Wang, Grant, Barty, Yefanov, Scales, Gati, Seuring, Srajer, Henning, Schwander, Fromme, Ourmazd, Moffat, Van Thor, Spence, Fromme, Chapman and Schmidt2014), obtain cryo-EM electron density maps at sub 3 Å resolution (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Veesler, Cheng, Potter and Carragher2015; Merk et al. Reference Merk, Bartesaghi, Banerjee, Falconieri, Rao, Davis, Pragani, Boxer, Earl, Milne and Subramaniam2016), or record multidimensional NMR spectra of protein crystals (Igumenova et al. Reference Igumenova, Mcdermott, Zilm, Martin, Paulson and Wand2004). Yet, the task in front of the structural biologist is getting harder and harder. The wealth of structural, biochemical and biological data has revealed that many mammalian cellular proteins are very large (>50 kD) (Brocchieri & Karlin, Reference Brocchieri and Karlin2005), that they are often part of complex assemblies composed of many interchangeable molecular players, and that their function is often defined and regulated by an intricate layer of post-translational modifications (PTMs). In addition, many disease-related biological macromolecules do not have a defined secondary or tertiary structure at all, and function, instead, through intrinsic disorder and numerous weak, transient interactions (Hyman et al. Reference Hyman, Weber and Julicher2014; Tompa, Reference Tompa2012). To make sense of this complicated, multilayered and often chaotic biological world, the structural biologist will become more and more dependent on the ability of protein engineers to faithfully and efficiently reproduce this complexity in the test tube.

Analogous to the advances in instrumentation design and engineering that have allowed structural biology to travel far, the tools of protein engineering have also become much more sophisticated, efficient and ultimately broader in scope over time. It is now possible to routinely synthesize polypeptide chains that are 50 amino acids long, to stitch them together into much longer chains without leaving any chemical scars (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Muir, Clark-Lewis and Kent1994), and to decorate them with PTMs, biophysical probes and chemical moieties that perturb or enhance their function. It is also possible to ‘persuade’ the cellular protein synthesis machinery to produce polypeptide chains incorporating completely unnatural amino acids, thus expanding the genetic code of engineered living organisms (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Brock, Herberich and Schultz2001). The current protein engineering toolbox contains many biocompatible chemical reactions, proteins with unique polypeptide ‘stitching’ abilities, and concepts and ideas that might ultimately prove essential in solving the interesting and relevant structural biology problems of today (Fig. 1). As the structural biologist might not be aware of all the current developments in protein chemistry, we intend this review as a resource that describes the state-of-the-art protein engineering tools, keeping an eye on the past and future to provide context for their limitations and the exciting new possibilities that undoubtedly lie ahead. We start with a very brief overview of recent advances in X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM and NMR, and outline challenges where the tools of protein engineering might be the most impactful. We then describe the contents of the molecular engineering toolbox that allow the construction of large modified proteins and complex macromolecular assemblies. We continue with a discussion of the concepts and ideas that directly concern structural biology methodology development. Our monograph ends with an outlook toward emerging trends in structural and chemical biology and exciting new developments that will guide the two fields in the future.

Fig. 1. Molecular engineering toolbox for the structural biologist.

2. Advances and challenges in structural biology

2.1 X-ray crystallography

The workhorse of structural biology, X-ray crystallography, is more than 100 years old and has contributed nearly 90% of the macromolecular structures deposited in the PDB (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/statistics/holdings.do). Protein engineering has long been part of the everyday life of the crystallographer as mutations, truncations and fusion proteins are often required to ‘trick’ proteins into adopting a crystal form. There are many crystal structures of proteins containing PTMs or their analogs, and chemical approaches are often used to trap interesting functional states, stabilize dynamic interactions or aid the formation of crystals (e.g. racemic crystallography (Yeates & Kent, Reference Yeates and Kent2012)). Yet, the voracious need to test hundreds if not thousands of single crystal growth conditions has certainly challenged the protein chemist to optimize her tools and deliver relevant samples with much greater yields. Recent instrumentation developments such as X-ray free-electron lasers may potentially alleviate this need as these sources allow the acquisition of room-temperature data from easier to obtain micro-, nano- and 2D crystals (Neutze et al. Reference Neutze, Branden and Schertler2015). Currently, there is also a growing demand for the construction of homogeneous, chemically well defined and stable complex biological assemblies such as those relevant for chromatin biology, for example.

2.2 Cryo-EM

Exciting developments in the last few years have propelled cryo-EM into the spotlight and turned this method into a mainstream and vital structural biology technique that can achieve crystallographic resolution (Cheng, Reference Cheng2015; Nogales, Reference Nogales2016). The commercialization of direct electron-detection cameras has allowed the acquisition of images with higher contrast and fast readouts that can overcome beam-induced motion and radiation damage (Brilot et al. Reference Brilot, Chen, Cheng, Pan, Harrison, Potter, Carragher, Henderson and Grigorieff2012; McMullan et al. Reference Mcmullan, Chen, Henderson and Faruqi2009). On the other hand, improvements in data analysis approaches have made it possible to characterize heterogeneous samples and even rare structural states (Fernandez et al. Reference Fernandez, Bai, Hussain, Kelley, Lorsch, Ramakrishnan and Scheres2013; Scheres, Reference Scheres2012). Coupled with other cryo-EM advantages (no need for crystallization and only small amounts of sample required), these advances have made it possible to obtain subnanometer (and in some cases <3 Å) resolution maps of integral membrane proteins (Matthies et al. Reference Matthies, Dalmas, Borgnia, Dominik, Merk, Rao, Reddy, Islam, Bartesaghi, Perozo and Subramaniam2016), biological polymers (von der Ecken et al. Reference Von der Ecken, Muller, Lehman, Manstein, Penczek and Raunser2015), chromatin (Song et al. Reference Song, Chen, Sun, Wang, Dong, Liang, Xu, Zhu and Li2014), as well as biological assemblies such as the transcription and translation initiation complexes (Fernandez et al. Reference Fernandez, Bai, Hussain, Kelley, Lorsch, Ramakrishnan and Scheres2013; He et al. Reference He, Fang, Taatjes and Nogales2013; Plaschka et al. Reference Plaschka, Hantsche, Dienemann, Burzinski, Plitzko and Cramer2016). In this context, protein chemistry and engineering can have a tremendous benefit for the cryo-EM structural biologist in the design and construction of relevant biological samples such as post-translationally modified proteins. Perhaps more importantly, however, chemical biology approaches such as cross-linking can allow the preparation of samples that are more robust and do not fall apart during sample vitrification. The addition of cross-linkers can also be extremely useful in integrated cryo-EM/mass-spec structural approaches for samples where the high-resolution identification of protein–protein interfaces might not be possible (Leitner et al. Reference Leitner, Faini, Stengel and Aebersold2016).

2.3 NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy detects the magnetic properties of nuclei in molecules, which in turn provide a window into their surrounding chemical environment. Uniquely suited to probe molecular structure and dynamics in solution at physiologically relevant conditions (temperature, pH and salts) and ultimately non-destructive in its readout, NMR spectroscopy has long been battered by its intrinsically low sensitivity. The introduction of ‘NMR-visible’ isotopic labels into biological macromolecules has become a standard practice in the field, and efficient molecular engineering approaches that allow the installation of nuclear isotopes at specific positions within the polypeptide or polynucleotide chain are highly desirable. Recent advances such as (methyl)-TROSY and dark-state exchange saturation transfer experiments have pushed the molecular size limits of solution NMR into the MDa regime (Fawzi et al. Reference Fawzi, Ying, Ghirlando, Torchia and Clore2011; Pervushin et al. Reference Pervushin, Riek, Wider and Wuthrich1997; Tugarinov et al. Reference Tugarinov, Hwang, Ollerenshaw and Kay2003), while the rapid instrumentation and pulse sequence developments in magic angle spinning NMR have made it possible to pursue the structures of large biological polymers such as amyloid fibrils (Fitzpatrick et al. Reference Fitzpatrick, Debelouchina, Bayro, Clare, Caporini, Bajaj, Jaroniec, Wang, Ladizhansky, Muller, Macphee, Waudby, Mott, De Simone, Knowles, Saibil, Vendruscolo, Orlova, Griffin and Dobson2013; Lu et al. Reference Lu, Qiang, Yau, Schwieters, Meredith and Tycko2013; Wasmer et al. Reference Wasmer, Lange, Van Melckebeke, Siemer, Riek and Meier2008), bacterial secretion needles (Loquet et al. Reference Loquet, Sgourakis, Gupta, Giller, Riedel, Goosmann, Griesinger, Kolbe, Baker, Becker and Lange2012), membrane proteins embedded in their native lipid environments (Cady et al. Reference Cady, Schmidt-Rohr, Wang, Soto, Degrado and Hong2010; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Munro, Shi, Kawamura, Okitsu, Wada, Kim, Jung, Brown and Ladizhansky2013), or even the molecular composition of bones (Chow et al. Reference Chow, Rajan, Muller, Reid, Skepper, Wong, Brooks, Green, Bihan, Farndale, Slatter, Shanahan and Duer2014). Thus, molecular engineering approaches can have a profound impact on the assembly of homogeneous, isotopically labeled and yet native substrates for structural investigation by in vitro NMR. Also, uniquely suited to probe structure and dynamics in the cellular milieu (Burz et al. Reference Burz, Dutta, Cowburn and Shekhtman2006; Frederick et al. Reference Frederick, Michaelis, Corzilius, Ong, Jacavone, Griffin and Lindquist2015; Inomata et al. Reference Inomata, Ohno, Tochio, Isogai, Tenno, Nakase, Takeuchi, Futaki, Ito, Hiroaki and Shirakawa2009; Sakakibara et al. Reference Sakakibara, Sasaki, Ikeya, Hamatsu, Hanashima, Mishima, Yoshimasu, Hayashi, Mikawa, Walchli, Smith, Shirakawa, Guntert and Ito2009), NMR spectroscopy can benefit tremendously from chemical and molecular biology techniques that allow the specific isotopic labeling of macromolecules in the cell.

3. Molecular engineering toolbox for complex biological samples

Before we delve into the chemistry, it is important to note that the methods described below complement the well-established molecular biology framework that allows the manipulation of protein sequences at the genetic level. Such manipulations can now be achieved in several different organisms ranging from bacteria (Escherichia coli, Lactococcus lactis), yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris), insect cells, and stable mammalian expression cell lines such as HEK293 and CHO. Thus, we will start with review of the methodologies that can selectively modify natural amino acids introduced at specific protein positions with site-directed mutagenesis. We will then describe tools that can be used to ligate modified peptides and proteins into longer polypeptide chains, including native chemical ligation (NCL), inteins and transpeptidases. We will then discuss the molecular engineering toolbox afforded by incorporation of unnatural amino acids by amber suppression. These chemical and genetic tools give chemists the ability to position bio-orthogonal reactive handles into polypeptide chains with extraordinary precision and control, and we will end this section with discussion of bioconjugation approaches that take advantage of this rapidly evolving expertise.

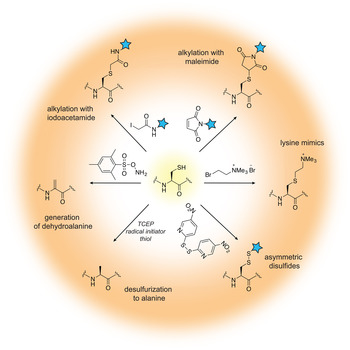

3.1 Cysteine chemistry

The field of protein chemistry would have been very different in a world without cysteines. Indeed, many of the protein chemistry tools that exist today have been developed to exploit the reactivity of the cysteine sulfhydryl group that uniquely stands out among a sea of other protein side-chains. Cysteines are relatively rare in Nature (<2% abundance), and their high nucleophilicity makes them good candidates for the development of selective chemical reactions that work well in protein compatible conditions (aqueous solution, physiological pH and temperature). Generally, these reactions can be divided into three types: (1) cysteine alkylations, (2) oxidations and (3) desulfurization reactions, each providing a unique way to exploit the reactivity of this amino acid and a pathway to build proteins with distinct and desirable properties (reviewed in (Chalker et al. Reference Chalker, Bernardes, Lin and Davis2009; Spicer & Davis, Reference Spicer and Davis2014)) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Chemical modification of cysteine residues.

Alkylation reactions have long been used to modify cysteine containing proteins and rely on familiar reagents such as iodoacetamide and maleimide. By careful control of the buffer pH, these electrophiles can selectively react with the cysteine sulfhydryl group and tether additional functionalities to the protein of interest. Iodoacetamides and other α-halocarbonyls, for example, have been used to attach carbohydrate moieties to proteins and create glycoprotein mimics (Macmillan et al. Reference Macmillan, Bill, Sage, Fern and Flitsch2001; Tey et al. Reference Tey, Loveridge, Swanwick, Flitsch and Allemann2010). Maleimides, on the other hand, are commercially available and user-friendly means to add spectroscopic probes to proteins, including fluorescent, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) labels. Aminoethylation of cysteines also provides a cheap and convenient way to generate lysine methylation analogs, available in the mono-, di- and tri-methylation states (Simon et al. Reference Simon, Chu, Racki, De La Cruz, Burlingame, Panning, Narlikar and Shokat2007). In recent years, the chemist's attention has turned toward the development of more advanced cysteine bioconjugation protocols that circumvent, for example, the reversibility of maleimide additions in the presence of external bases and thiols (Lyon et al. Reference Lyon, Setter, Bovee, Doronina, Hunter, Anderson, Balasubramanian, Duniho, Leiske, Li and Senter2014), or provide the opportunity to conjugate additional functionalities (such as aryl groups) under an expanded range of reaction conditions (Vinogradova et al. Reference Vinogradova, Zhang, Spokoyny, Pentelute and Buchwald2015).

Cysteine oxidation in the protein context is usually associated with the formation of disulfide bonds, a unique structural transformation with often dramatic consequences to protein function. In the test tube, disulfide bonds are very easy to build – all that is required is basic pH and exposure to air. Furthermore, the reaction is fast and does not require large excess of reagents. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that protein chemists often exploit disulfide bonds as means to attach useful functionalities to proteins of interest. The challenging aspect of such protocols is to ensure that only the desired disulfide bonds are formed and the final product is not a mixture of homo- and heterodimer species. A common strategy used to alleviate this problem relies on controlled cysteine activation and disulfide exchange based on the lower pKa of aromatic thiols. In this case, a selected cysteine side-chain can be activated (and protected) at low pH with the aromatic thiol, and upon addition of the other thiol-containing component and increase in pH, the aromatic disulfide bond is exchanged with the desired connectivity (Pollack & Schultz, Reference Pollack and Schultz1989; Rabanal et al. Reference Rabanal, Degrado and Dutton1996). This strategy has found diverse applications ranging from the design of cytochrome peptides (Rabanal et al. Reference Rabanal, Degrado and Dutton1996) to the tethering of ubiquitin moieties to various proteins (Chatterjee et al. Reference Chatterjee, Mcginty, Fierz and Muir2010; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Ai, Wang, Haracska and Zhuang2010a; Meier et al. Reference Meier, Abeywardana, Dhall, Marotta, Varkey, Langen, Chatterjee and Pratt2012). Other activating molecules include methanethiosulfonates, glycosyl and allylic thiols with applications in protein glycosylation, prenylation and sulfenylation (Gamblin et al. Reference Gamblin, Van Kasteren, Bernardes, Chalker, Oldham, Fairbanks and Davis2008; Grayson et al. Reference Grayson, Ward, Hall, Rendle, Gamblin, Batsanov and Davis2005; van Kasteren et al. Reference Van Kasteren, Kramer, Jensen, Campbell, Kirkpatrick, Oldham, Anthony and Davis2007).

While the formation of disulfide bonds is fast and facile, they are just as easily destroyed in the presence of common biochemical reducing reagents or in the cellular environment where glutathione is present at high concentrations. If compatible linkages are desired, it is possible to convert the disulfide to a thioether bond, which is stable under reducing conditions. This is essentially a desulfurization reaction that proceeds with the formation of a dehydroalanine intermediate. Dehydroalanines, on the other hand, can be useful stepping stones to a vast number of protein PTMs, reactions that will be discussed in more detail in Section 3.7. Another key desulfurization reaction involves the conversion of cysteine to alanine. This transformation, discussed in more detail in Section 3.3, is particularly important for NCL, as it allows the construction of polypeptide chains without cysteine ‘scars’.

Cysteines are relatively rare in polypeptide chains and are usually essential for protein function. Thus, the outstanding challenge for the protein chemist is to find new approaches and reaction conditions that target only the desired residues in a polypeptide chain. Many of these efforts are focused on the search of suitable peptide sequences that can provide the necessary amino acid context for tuning side-chain reactivity. For example, Tsien and co-workers have developed tetra-cysteine motifs that can be selectively targeted with biarsenic reagents, including in living cells (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Adams and Tsien1998). Pentelute and co-workers, on the other hand, have reported the so-called ‘π-clamp’ sequence (Phe–Pro–Cys–Phe) that reacts preferentially with perfluoroaromatic moieties in aqueous solvents (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Welborn, Zhu, Yang, Santos, Van Voorhis and Pentelute2016a). Excellent selectivity can be obtained by replacing cysteine with selenocysteine (reviewed in (Metanis et al. Reference Metanis, Beld, Hilvert and Rappoport2009; Yoshizawa & Bock, Reference Yoshizawa and Bock2009), a rare natural amino acid that shares many of the desirable properties of the cysteine side-chain, yet is more acidic and substantially more reactive at lower pH (selenol pKa is ~5·2 versus 8·3 for thiols).

3.2 Chemical modification of other amino acids

In addition to cysteine, several other natural amino acids present functional groups that can be targeted for protein modification (reviewed in (Basle et al. Reference Basle, Joubert and Pucheault2010; Spicer & Davis, Reference Spicer and Davis2014)). These include lysine, tyrosine, arginine, glutamate, aspartate, serine, threonine, methionine, histidine and tryptophan side-chains, as well as N-terminal amines or C-terminal carboxyls (Basle et al. Reference Basle, Joubert and Pucheault2010; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Berti and Adamo2016; Lin et al. Reference Lin, Yang, Jia, Weeks, Hornsby, LEE, Nichiporuk, Iavarone, Wells, Toste and Chang2017). The modification of these residues is less precise as they are significantly more abundant than cysteine, yet, some selectivity can be achieved in a context-dependent manner. The primary amines of lysine side-chains are often popular targets due to favorable reaction kinetics that can be achieved with activated esters such as N-hydroxysuccinimide (Kalkhof & Sinz, Reference Kalkhof and Sinz2008) (Fig. 3a ), isothiocyanates (Nakamura et al. Reference Nakamura, Kawai, Kitamoto, Osawa and Kato2009), or aldehydes in a reductive alkylation reaction with sodium cyanoborohydride (Jentoft & Dearborn, Reference Jentoft and Dearborn1979; McFarland & Francis, Reference Mcfarland and Francis2005). Since these reactions usually modify all accessible lysine side-chains, they can be used in applications that require multiple modifications (e.g. therapeutic protein conjugates) or in protein cross-linking for mass spectrometry analysis (Holding, Reference Holding2015). An example of a more discriminating lysine-based modification strategy involves the 6π-aza-electrocyclization reaction with unsaturated aldehyde esters that targets solvent-accessible lysine residues with excellent selectivity and reaction kinetics, and has been used for the attachment of fluorescent or positron emission tomography probes (Tanaka et al. Reference Tanaka, Kitadani and Fukase2011). Yet, further selectivity can be achieved by discriminating the lower pKa of N-terminal amino groups (~8) from the pKa of the ε-amine of a lysine side-chain (~10·5). The identity of the N-terminal amino acid may further change the reactivity of the α-amine, although more general modification strategies have been developed. For example, functionalized ketenes can preferentially react with the α-amine in the context of 13 different N-terminal amino acids (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Ho, Chong, Leung, Huang, Wong and Che2012), while 2-pyridinecarboxyaldehydes provide efficient and specific N-terminal labeling for all amino acids except proline (MacDonald et al. Reference Macdonald, Munch, Moore and Francis2015) (Fig. 3b ). The unique reactivity of the N-terminus is also central to the mechanism of native chemical ligation, discussed in Section 3.3.

Fig. 3. Chemical modification of natural amino acids. (a) Modification of lysine ε-amines with activated esters such as N-hydroxysuccinimide. (b) Modification of terminal α-amines with 2-pyridinecarboxyaldehydes. (c) Three-component Mannich reaction for tyrosine modification at the ortho-position. (d) Coupling of carboxyls and amines with carbodiimides such as EDC.

A set of chemical reactions has also been developed for the specific modification of the aromatic electron-rich tyrosine side-chain. The selectivity of tyrosine-focused reactions usually exploits the low exposure of this residue on native protein surfaces and its susceptibility to oxidation (ElSohly & Francis, Reference Elsohly and Francis2015; Seim et al. Reference Seim, Obermeyer and Francis2011). In particular, modification of the ortho-position can be achieved with diazonium salts (Schlick et al. Reference Schlick, Ding, Kovacs and Francis2005) or the three-component Mannich-type reaction with aldehydes and anilines (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Whitaker and Francis2004; McFarland et al. Reference Mcfarland, Joshi and Francis2008) (Fig. 3c ). While some side-reactions have been known to occur, it has been possible to optimize the selectivity of the Mannich-type reaction to achieve efficient modification of a single tyrosine residue with an EPR spin label in the presence of disulfide and tryptophan functionalities (Mileo et al. Reference Mileo, Etienne, Martinho, Lebrun, Roubaud, Tordo, Gontero, Guigliarelli, Marque and Belle2013). Proteins containing few surface exposed tyrosine residues can also be modified at low concentrations (5 µM) in aqueous solvents with π-allylpalladium reagents (Tilley & Francis, Reference Tilley and Francis2006).

Carboxyl groups in glutamate and aspartate side-chains can be targeted with water-soluble carbodiimides such as N-ethyl-3-N′-N′-dimethylaminopropylcarbodiimide (EDC) (Fig. 3 d). In what is essentially a standard peptide coupling reaction, this reagent pairs carboxyls and amines in a covalent amide bond under aqueous conditions in a pH-dependent manner (Gilles et al. Reference Gilles, Hudson and Borders1990). Commonly employed as a cross-linking reagent for the identification of protein–protein interactions in biochemical assays and mass spectrometry, EDC can also be used to modify protein assemblies such as viral capsids with a variety of functional and biophysical probes (Schlick et al. Reference Schlick, Ding, Kovacs and Francis2005). While EDC-based reactions do not discriminate between side-chain and C-terminal carboxyl groups, unique reactivity at the C-terminus can be generated by replacing the carboxyl functionality with a thioester, as discussed in the sections below.

3.3 Native chemical ligation

The unique reactivity of the cysteine side-chain and the positional control afforded by the protein N- and C-termini are at the heart of a simple, yet powerful, chemical reaction that allows the construction of native polypeptide chains from peptide-building blocks. This methodology, called NCL (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Muir, Clark-Lewis and Kent1994), grants unprecedented control over the chemical functionalities that can be introduced in a polypeptide chain and is a fundamental tool in the repertoire of protein chemists. NCL simply requires two components with the following properties: (1) a peptide with a C-terminal thioester, and (2) a peptide with an N-terminal cysteine residue (or functional equivalent). When these components are mixed, the cysteine side-chain attacks the thioester of the other peptide, resulting in the formation of an intermolecular thioester (Fig. 4). This intermediate rapidly and irreversibly rearranges to form a native peptide bond, thus ligating the two fragments. Since both peptides can be produced by solid-phase peptide synthesis, virtually any modified natural or unnatural amino acid, spectroscopic probe, cross-linker or isotopic label can be incorporated at a well-defined position into the ligated sequence (Dawson & Kent, Reference Dawson and Kent2000). Moreover, in contrast to biosynthetic approaches such as amber suppression (see Section 3.6), there is no practical restriction on the number, or type, of unnatural amino acids that can be introduced – this point is driven home by the total synthesis of enantiomeric proteins composed of all D-amino acids (Mandal et al. Reference Mandal, Uppalapati, Ault-Riche, Kenney, Lowitz, Sidhu and Kent2012). The remarkable chemoselectivity of the NCL reaction means that ligations can be performed under aqueous conditions in the presence of internal cysteine residues. NCL is also compatible with protein denaturants or detergents allowing the construction of aggregation prone polypeptide chains or even polytopic membrane proteins (Hejjaoui et al. Reference Hejjaoui, Butterfield, Fauvet, Vercruysse, Cui, Dikiy, Prudent, Olschewski, ZHANG, Eliezer and Lashuel2012; Kwon et al. Reference Kwon, Tietze, White, Liao and Hong2015; Valiyaveetil et al. Reference Valiyaveetil, Leonetti, Muir and Mackinnon2006). The fragment bearing the N-terminal cysteine can also be produced recombinantly, usually preceded by a cleavable tag or fusion protein to avoid N-terminal cysteine processing complications in bacteria. Alternatively, the thioester component can be generated recombinantly with the help of proteins called inteins (Muir et al. Reference Muir, Sondhi and Cole1998) (see Section 3.4). It is also possible to perform sequential NCL reactions, allowing three or more building blocks to be assembled in a regioselective fashion (Mandal et al. Reference Mandal, Uppalapati, Ault-Riche, Kenney, Lowitz, Sidhu and Kent2012; Torbeev & Hilvert, Reference Torbeev and Hilvert2013). These advances thus allow the construction of considerably larger polypeptide chains that would be accessible from two synthetic peptides alone.

Fig. 4. Native chemical ligation at cysteine followed by desulfurization to alanine for the construction of larger polypeptide chains without any ‘scars’.

While NCL results in a native peptide bond, the required cysteine may still produce an unwanted ‘scar’ at the ligation junction – i.e. in cases where the target does not contain a native cysteine at an appropriate ligation point. If the final ligation product does not contain other cysteine residues, then the undesirable cysteine can be converted to alanine in a subsequent desulfurization step. Options for desulfurization reactions include reduction with metals or radical desulfurization mediated by the familiar tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) reagent (Dawson, Reference Dawson2011; Wan & Danishefsky, Reference Wan and Danishefsky2007; Yan & Dawson, Reference Yan and Dawson2001). Selective desulfurization reactions are also possible in the presence of other cysteine residues, provided that compatible protecting groups are used on the non-targeted cysteine side-chains (Ficht et al. Reference Ficht, Payne, Brik and Wong2007; Pentelute & Kent, Reference Pentelute and Kent2007). Alternatively, selective ligation and desulfurization of selenocysteine can provide additional sequence positional control (Hondal et al. Reference Hondal, Nilsson and Raines2001; Reddy et al. Reference Reddy, Dery and Metanis2016). Today, desulfurization has become a routine part of NCL protocols and the abundant alanine residue is a commonplace choice for a ligation site. To expand the junction amino acid set, a more advanced strategy involves the incorporation of β- and γ-thio amino acids. These moieties replace the cysteine-like residue at the N-terminal position, and provide a reactive thiol for trans-thioesterification. Desulfurization protocols can then produce the desired native side-chain. While ligations at such sites proceed more slowly due to increased steric hindrance, NCL can now be performed at phenylalanine (Crich & Banerjee, Reference Crich and Banerjee2007), valine (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wan, Yuan, Zhu and Danishefsky2008; Haase et al. Reference Haase, Rohde and Seitz2008), leucine (Harpaz et al. Reference Harpaz, Siman, Kumar and Brik2010; Tan et al. Reference Tan, Shang and Danishefsky2010), threonine (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Zhu, Wan and Danishefsky2010b), lysine (El Oualid et al. Reference El Oualid, Merkx, Ekkebus, Hameed, Smit, De Jong, Hilkmann, Sixma and Ovaa2010; Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Haj-Yahya, Olschewski, Lashuel and Brik2009; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Pasunooti, Li, Liu and Liu2009), proline (Shang et al. Reference Shang, Tan, Dong and Danishefsky2011), glutamine (Siman et al. Reference Siman, Karthikeyan and Brik2012), arginine (Malins et al. Reference Malins, Cergol and Payne2013), tryptophan (Malins et al. Reference Malins, Cergol and Payne2014), aspartate (Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Chan, Radom, Jolliffe and Payne2013), glutamate (Cergol et al. Reference Cergol, Thompson, Malins, Turner and Payne2014) and asparagine (Sayers et al. Reference Sayers, Thompson, Perry, Malins and Payne2015). Work also continues on more streamlined ligation/desulfurization approaches that remove purification steps and increase the yield of ligated products (Moyal et al. Reference Moyal, Hemantha, Siman, Refua and Brik2013; Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Liu, Alonso-Garcia, Pereira, Jolliffe and Payne2014).

The preceding discussion highlights just a few of the many refinements and extensions the NCL strategy has undergone since its introduction over 20 years ago (Harmand et al. Reference Harmand, Murar and Bode2014; Malins & Payne, Reference Malins and Payne2015). As a consequence of this massive effort, the technique has become a central tool in protein science, having been applied to literally hundreds of protein targets. Of particular relevance here, it has provided the raw materials for numerous structural biology studies that have employed a broad range of spectroscopic or crystallographic methods (Fig. 5) (Grosse et al. Reference Grosse, Essen and Koert2011; Kent et al. Reference Kent, Sohma, Liu, Bang, Pentelute and Mandal2012; Muralidharan & Muir, Reference Muralidharan and Muir2006). In general, the ability to modify any atom in the protein of interest with the precision afforded by synthetic organic chemistry is enormously powerful for dissecting protein function, especially when combined with high-resolution structural approaches such as NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. Thus, we imagine that NCL will continue to evolve as an approach and be integrated into structural biology campaigns.

Fig. 5. Examples of constructs prepared by NCL and EPL for X-ray crystallography studies. (a) D-alanine was introduced at position 77 in the sequence of the potassium channel KcsA to elucidate its ion selectivity mechanism (Valiyaveetil et al. Reference Valiyaveetil, Leonetti, Muir and Mackinnon2006) (PDB ID: 2IH3). (b) Acetylated lysine (Ac) was incorporated at postions 401 and 408 in S-Adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (SAHH) to evaluate the structural basis of enzyme inhibition (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Kavran, Chen, Karukurichi, Leahy and Cole2014b) (PDB ID: 4PFJ). (c) Chemical synthesis of HIV protease afforded the site-specific incorporation of unnatural amino acids such as 2-aminoisobutyric acid to modulate conformational dynamics and catalysis (Torbeev et al. Reference Torbeev, Raghuraman, Hamelberg, Tonelli, Westler, Perozo and Kent2011) (PDB ID: 3IAW). (d) Semi-synthesis of Mxe GyrA and the installation of β-thienyl-alanine instead of the native histidine at position 187 provided a route to trap the branched intermediate of the intein (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Frutos, Bick, Vila-Perello, Debelouchina, Darst and Muir2014b) (PDB ID: 4OZ6).

3.4 Inteins

Inteins (intervening proteins) are a peculiar group of proteins that can excise themselves from a larger precursor polypeptide chain, a process that leads to the formation of a native peptide bond between the flanking extein (external protein) fragments. This auto-processing event, called protein splicing, is analogous to the self-splicing of RNA introns and is spontaneous, i.e. it does not require external factors or ATP. Since they were first discovered in the early 1990s (Hirata et al. Reference Hirata, Ohsumk, Nakano, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Anraku1990; Kane et al. Reference Kane, Yamashiro, Wolczyk, Neff, Goebl and Stevens1990), thousands of putative intein domains have been identified in the genomes of many unicellular organisms and viruses, with some containing multiple inteins in their genomes or even within the same gene (Perler, Reference Perler2002; Shah & Muir, Reference Shah and Muir2014). A small fraction of the known inteins has an even more curious property – the intein is split into two fragments, each fused to a separate extein fragment (the N- and C-exteins) (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Hu and Liu1998). These intein fragments, called split inteins, are transcribed and translated separately, and upon a spontaneous and non-covalent association in the cellular milieu, they carry out protein splicing in trans to unite the extein fragments into a single polypeptide chain. While it is known that many inteins are embedded within essential protein genes (such as DNA or RNA polymerase, ribonucleotide reductase or metabolic enzymes), their evolutionary origins and biological significance remain mysterious, and only a small percentage of the identified intein domains have been carefully characterized (Pietrokovski, Reference Pietrokovski2001; Shah & Muir, Reference Shah and Muir2014). Despite these big gaps in our knowledge, the unique reactivity of inteins has turned them into a versatile and transformative tool in protein chemistry and chemical biology. For a detailed overview of intein applications, we refer the interested reader elsewhere (Shah & Muir, Reference Shah and Muir2014; Topilina & Mills, Reference Topilina and Mills2014; Volkmann & Mootz, Reference Volkmann and Mootz2013; Wood & Camarero, Reference Wood and Camarero2014). Here, we will focus on aspects of intein function that would be of use to the structural biologist looking to install site-specific PTMs, segmentally label proteins with NMR isotopes, or aid the purification of recombinant polypeptides. Inteins have come a long way since their first applications in structural biology (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Ayers, Cowburn and Muir1999; Yamazaki et al. Reference Yamazaki, Otomo, Oda, Kyogoku, Uegaki, Ito, Ishino and Nakamura1998), so we will end this section with a discussion of the current members of the intein toolbox and research directions taken to circumvent their limitations.

3.4.1 The intein splicing mechanism

Despite the low-sequence homology of known intein domains, they share a common protein splicing mechanism that relies on several conserved residues in the intein/extein polypeptide (Fig. 6a ) (Volkmann & Mootz, Reference Volkmann and Mootz2013). One of these key residues is a cysteine (or in some cases a serine) at position 1 of the intein sequence. This nucleophilic side-chain attacks the amide carbon of the N-extein at position −1 (Fig. 6b ) resulting in an N to S(O) acyl shift and the formation of a linear thio(oxy)ester intermediate. This intermediate is subject to a nucleophilic attack by a side-chain (cysteine, serine or threonine) at position +1 on the C-extein leading to trans-(thio)esterification and the generation of a branched intermediate. The branched intermediate is resolved through the cyclization of the C-terminal asparagine of the intein and results in intein excision from the polypeptide chain. Next, the spliced exteins quickly undergo an S(O) to N acyl shift to form a native peptide bond (i.e. identical to the last step in NCL). The protein splicing mechanism is facilitated by several conserved threonine and histidine residues occupying strategic positions in the intein structural fold (Frutos et al. Reference Frutos, Goger, Giovani, Cowburn and Muir2010). The efficiency and kinetics of the splicing mechanism may also depend on the identity of the residues immediately flanking the intein placing important constraints on the choice of ligation junction (Cheriyan et al. Reference Cheriyan, Pedamallu, Tori and Perler2013; Iwai et al. Reference Iwai, zuger, Jin and Tam2006; Shah et al. Reference Shah, Dann, Vila-Perello, Liu and Muir2012).

Fig. 6. Intein structure and mechanism. (a) Intein/extein residues important for splicing. (b) Protein splicing mechanism of contiguous inteins. In some cases, the hydroxyl groups of Ser/Thr act as nucleophiles in the first two steps.

3.4.2 Applications in protein engineering

Expressed protein ligation (EPL) is an extension of NCL that employs a contiguous intein to recombinantly generate a protein bearing a C-terminal thioester (Muir et al. Reference Muir, Sondhi and Cole1998). In this case, the N-extein is fused to a modified intein construct lacking the ability to perform trans-thioesterification. Instead, this step is performed by an exogenously added thiol, resulting in cleavage of the N-extein α-thioester intermediate (Fig. 7a ). The resultant thioester can be used in NCL reactions as described in Section 3.3, while the recombinant origin of this fragment allows the construction of much larger semi-synthetic proteins as compared to total chemical synthesis by NCL. The efficiency of thioester generation rests on the propensity of the intein to avoid unwanted side reactions that result in premature N-extein cleavage and hydrolyzed products, problems that can be alleviated by the use of streamlined EPL protocols (Vila-Perello et al. Reference Vila-Perello, Liu, Shah, Willis, Idoyaga and Muir2013). Alternatively, hydrolysis of the N-extein under slightly basic conditions can be exploited in the so-called tagless protein purification protocols (Batjargal et al. Reference Batjargal, Walters and Petersson2015; Guan et al. Reference Guan, Ramirez and Chen2013; Southworth et al. Reference Southworth, Amaya, Evans, Xu and Perler1999) (Fig. 7b ). In this case, the protein of interest is fused to an intein carrying the appropriate mutations and a suitable purification tag. The tag can be used for affinity column enrichment of the construct, followed by increase in the buffer pH. This results in the release of the tagless protein while the intein remains on the column.

Fig. 7. Protein engineering with inteins. (a) Expressed protein ligation. (b) Tagless protein purification. (c) Protein trans-splicing and recombinant production of segmentally isotopically labeled proteins.

Harnessing the protein trans-splicing (PTS) process mediated by split inteins offers an alternative approach to the ligation of polypeptide building blocks (Fig. 7c ). Natural split inteins are especially attractive in this regard due to the extremely high affinity between the fragments (Shah et al. Reference Shah, Vila-Perello and Muir2011, Reference Shah, Eryilmaz, Cowburn and Muir2013) – this renders the ligation reaction less dependent on reagent concentration as compared to strictly chemical processes like NCL/EPL. Using orthogonal split intein pairs, it is also possible to perform one-pot three-piece ligations (Carvajal-Vallejos et al. Reference Carvajal-Vallejos, Pallisse, Mootz and Schmidt2012; Shah et al. Reference Shah, Vila-Perello and Muir2011; Shi & Muir, Reference Shi and Muir2005) resulting in the regiospecific assembly of the associated extein building blocks. While most natural split inteins have N- and C-fragments that are relatively large, it is possible to generate artificially split inteins that are as short as six or eleven residues (Appleby et al. Reference Appleby, Zhou, Volkmann and Liu2009; Ludwig et al. Reference Ludwig, Pfeiff, Linne and Mootz2006). There is also an efficient natural split intein pair (AceL–TerL) where the N-intein fragment is only 25 amino acids long (Thiel et al. Reference Thiel, Volkmann, Pietrokovski and Mootz2014). Thus, it is now possible to use PTS with both synthetic or recombinant intein fragments and to install a wide range of N- or C-terminal chemical modification, including biophysical probes. One of the most important applications of PTS in structural biology is protein segmental isotopic labeling discussed in Section 4.2. Other applications include the cyclization of proteins and peptides (Lennard & Tavassoli, Reference Lennard and Tavassoli2014; Scott et al. Reference Scott, Abel-santos, Wall, Wahnon and Benkovic1999), conditional protein splicing (Mootz et al. Reference Mootz, Blum, Tyszkiewicz and Muir2003; Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz, Saez, Young and Muir2007), and protein semi-synthesis in cells (David et al. Reference David, Vila-Perello, Verma and Muir2015).

3.4.3 Toward fast and promiscuous inteins

The first intein tools were introduced in the mid-to-late 1990s. One of the ‘early’ inteins, the 198-residue gyrase A intein from Mycobacterium xenopi (Mxe GyrA) (Southworth et al. Reference Southworth, Amaya, Evans, Xu and Perler1999), still used today, exhibits many desirable properties for applications in protein engineering – it is relatively small, can be efficiently expressed in E. coli, works in moderate concentrations of denaturants and its activity can be controlled with temperature. The first ‘natural’ split intein was discovered in 1998 in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 (Ssp) where it was found to ligate two fragments of the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase III (DnaE) (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Hu and Liu1998). This discovery paved the road to more efficient protein trans-splicing and opened the way to using split inteins in other applications such as the cyclization of proteins and peptides and the creation of large cyclized libraries for potential therapeutic applications (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Abel-santos, Wall, Wahnon and Benkovic1999).

While these first generation intein tools were certainly enabling (Vila-Perello & Muir, Reference Vila-Perello and Muir2010), they were not without their limitations – in retrospect, one could even say they were rather fussy and slow. For example, depending on the fusion partners, splicing (or thiolysis) could take hours to days and was often inefficient (Muralidharan & Muir, Reference Muralidharan and Muir2006). These ‘idiosyncrasies’ constrained the application of inteins in structural biology and fueled the search for faster, more promiscuous and efficient inteins. Several important discoveries in the mid-2000s challenged the view that all natural inteins are inefficient and slow. A genomic study of cyanobacterial genes expanded the DnaE intein family (Caspi et al. Reference Caspi, Amitai, Belenkiy and Pietrokovski2003) and the characterization of one newly discovered member, the DnaE intein from Nostoc punctiforme (Npu) revealed a few surprises. This split intein could perform protein trans-splicing reactions in vitro on a minute timescale and was much more tolerant to sequence deviations on the attached exteins than Ssp ((Iwai et al. Reference Iwai, zuger, Jin and Tam2006; Zettler et al. Reference Zettler, Schutz and Mootz2009). Now we know that many members of the DnaE family are fast (Shah et al. Reference Shah, Dann, Vila-Perello, Liu and Muir2012), thus greatly expanding the choice of natural intein tools for the efficient generation of protein α-thioesters for EPL or the ligation of protein fragments in PTS (Table 1). Furthermore, efficient natural split inteins that are not part of the DnaE family have also been discovered and these include the gp41-1 and gp41-8 inteins (with insertion sites in the gp41 DNA gyrase gene), the IMPDH-1 intein (splitting a gene coding for inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase), the NrdJ intein (splitting the gene coding for the ribonucleotide reductase subunit NrdJ) (Carvajal-Vallejos et al. Reference Carvajal-Vallejos, Pallisse, Mootz and Schmidt2012), and the AceL–TerL pair (discovered in metagenomics data from the antarctic permanently stratified saline Ace Lake) (Thiel et al. Reference Thiel, Volkmann, Pietrokovski and Mootz2014). These proteins bring more diversity to the intein molecular engineering toolbox, including splicing rates that are an order of magnitude faster than those for NpuDnaE; N- and C-intein fragments that are relatively short and can be made by peptide synthesis rather than recombinantly; the option of utilizing serine instead of cysteine at the +1 position; and the possibility of exploiting orthogonality in one-pot multi-piece ligations.

Table 1. Intein toolbox for protein semi-synthesis

* Optimal splicing kinetics in the presence of native sequences at the immediate intein-extein junctions. Variation from this sequence context can lead to less efficient splicing. See also ref. (Shah & Muir, Reference Shah and Muir2014).

Careful biochemical characterization of newly discovered inteins has provided insights into the principles governing fast splicing and extein tolerance. For example, a batch mutagenesis approach that compared the slow split intein DnaE family member Ssp and the fast Npu split intein revealed that speed is determined by a handful of ‘accelerator’ residues located in the second shell of the folded protein, adjacent to the intein active site (Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Brown, Shah, Sekar, Cowburn and Muir2016). These residues were used as a filter in an informatics analysis of the DnaE sequence database, leading to the identification of several dozens of other split inteins predicted to support ultrafast splicing. A consensus split intein sequence, termed Cfa, was then derived from this putative fast set and was found to possess quite remarkable properties; in addition to splicing faster than Npu at ambient conditions, Cfa is extremely robust, maintaining efficient activity at 80 °C or in the presence of up to 4 M guanidinium chloride or 8 M urea. As a result of these attributes, Cfa was found to be a superior tool for several PTS applications (Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Brown, Shah, Sekar, Cowburn and Muir2016).

3.5 Sortases

Sortases are a class of cysteine transpeptidases responsible for the attachment of virulence proteins to the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria (Mazmanian et al. Reference Mazmanian, Liu, Ton-That and Schneewind1999). They are also involved in the polymerization of pilin subunits to form the pilus structures responsible for bacterial attachment to the host and biofilm formation (Mandlik et al. Reference Mandlik, Swierczynski, Das and Ton-That2008). As important players in bacterial virulence, they have evolved to recognize a specific sorting sequence (LPXTG in the case of Staphylococcus aureus) and to attach the virulence factor to the cell wall using a pentaglycine cross-bridge (Ton-That et al. Reference Ton-That, Mazmanian, Faull and Schneewind2000). Naturally, sortases are of a considerable interest as drug targets, but they have also become an important and versatile protein engineering tool (Mao et al. Reference Mao, Hart, Schink and Pollok2004). Most sortase-based applications utilize the soluble fragment of wild-type or modified sortase A from S. aureus. These enzymes recognize the LPXTG motif and use their catalytic cysteine residue to cleave between the threonine and glycine backbone within the recognition sequence (Fig. 8). The cleavage reaction involves a thioacyl intermediate similar to the intermediates generated by cysteine proteases (Aulabaugh et al. Reference Aulabaugh, Ding, Kapoor, Tabei, Alksne, Dushin, Zatz, Ellestad and Huang2007). Unlike the water molecules employed by proteases, however, sortases use a nucleophilic attack from the N-terminus of an oligoglycine motif to create a peptide bond between the acyl donor and acceptor. This results in the ligation of polypeptide chains that are subsequently connected with a LPXT(G)5 linker. The sortase mechanism also requires binding of Ca2+ to a dynamic loop of the enzyme, an event that slows down the loop motion and allows enough time for the substrate to find the catalytic site (Naik et al. Reference Naik, Suree, Ilangovan, Liew, Thieu, Campbell, Clemens, Jung and Clubb2006). Another peculiarity of sortase-based ligations is their reversibility: the generated ligation site has the recognition sequence LPXTG and can serve as an acyl donor, while the released fragment contains an aminoglycine acyl receptor. Thus, to obtain efficient ligations, the donor or acceptor polypeptide chain typically has to be added in large excess (Guimaraes et al. Reference Guimaraes, Witte, Theile, Bozkurt, Kundrat, Blom and Ploegh2013).

Fig. 8. C-terminal protein labeling with sortase. The acyl donor requires the LPXTG recognition motif, while the acyl acceptor often contains a pentaglycine sequence.

Analogous to intein technology development, sortases have considerably improved as protein engineering tools since their introduction in 2004 (Antos et al. Reference Antos, Truttmann and Ploegh2016). The sortase-based protein engineering toolbox now contains evolved variants that exhibit much faster kinetics or that eliminate Ca2+-dependence (albeit at the cost of slightly reduced enzyme activity) (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Dorr and Liu2011; Hirakawa et al. Reference Hirakawa, Ishikawa and Nagamune2015; Wuethrich et al. Reference Wuethrich, Peeters, Blom, Theile, Li, Spooner, Ploegh and Guimaraes2014). There are also alternatives based on S. aureus sortase A or homologs from other organisms that can recognize variations of the LPXTG motif and/or allow non-glycine amino acids as the acyl acceptor (Antos et al. Reference Antos, Truttmann and Ploegh2016; Dorr et al. Reference Dorr, Ham, An, Chaikof and Liu2014; Glasgow et al. Reference Glasgow, Salit and Cochran2016). To increase the yields of the ligation reaction, several clever strategies have been employed. In situations where the released aminoglycine peptide fragment is relatively small, it can be removed by dialysis or centrifugation while the reaction is proceeding (Freiburger et al. Reference Freiburger, Sonntag, Hennig, Li, Zou and Sattler2015). Affinity immobilization strategies or flow-based platforms have also been used for the selective removal of reaction components (Policarpo et al. Reference Policarpo, Kang, Liao, Rabideau, Simon and Pentelute2014; Warden-Rothman et al. Reference Warden-Rothman, Caturegli, Popik and Tsourkas2013). Alternatively, the equilibrium of the reaction can be controlled by ligation product or by-product deactivation. In the first case, a WTWTW motif was added to the donor and acceptor, and upon ligation this sequence promoted a stable hairpin at the ligation junction, rendering the site inaccessible for cleavage (Yamamura et al. Reference Yamamura, Hirakawa, Yamaguchi and Nagamune2011). In the latter case, the acyl donor glycine was chemically modified such that upon release, chemical rearrangements occurred on the by-product transforming it into a poor nucleophile (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Luo, Flora and Mezo2014a; Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Webb and Turnbull2014).

One important advantage of sortase-based ligations is that the acyl donor and acceptor polypeptide chains can be very short (only the LPXTG tag is required on the donor, and the oligoglycine motif is necessary on the acceptor) and thus are easily accessible by solid-phase peptide synthesis. Therefore, N- and C-terminal labeling reactions of large proteins are relatively straightforward (assuming by-products are efficiently removed) (Guimaraes et al. Reference Guimaraes, Witte, Theile, Bozkurt, Kundrat, Blom and Ploegh2013; Theile et al. Reference Theile, Witte, Blom, Kundrat, Ploegh and Guimaraes2013). Larger polypeptides, on the other hand, can be expressed recombinantly with the appropriate donor and acceptor tags and the ligation reaction unites them in a single polypeptide chain with an LPXT(G) n ‘scar’. In such cases it is recommended that the ligation junction is chosen on an unstructured region where it will not affect the function and/or fold of the protein and will be accessible to the sortase catalytic site (Guimaraes et al. Reference Guimaraes, Witte, Theile, Bozkurt, Kundrat, Blom and Ploegh2013). Such reactions can be applied to create polymers and cyclized polypeptides (van ‘t Hof et al. Reference Van ‘T Hof, Hansenova Manaskova, Veerman and Bolscher2015), or to stitch together domains into bifunctional or segmentally labeled proteins (Matsumoto et al. Reference Matsumoto, Furuta, Tanaka and Kondo2016; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Milbradt, Embrey and Bobby2016; Witte et al. Reference Witte, Cragnolini, Dougan, Yoder, Popp and Ploegh2012). Sortase-based labeling has also been used in the functionalization of solid supports, nanoparticles, antibodies or cell surfaces, as well as in the labeling of proteins in vivo. We refer the interested reader to several comprehensive reviews on the subject (Popp & Ploegh, Reference Popp and Ploegh2011; Ritzefeld, Reference Ritzefeld2014; Schmohl & Schwarzer, Reference Schmohl and Schwarzer2014).

The success of sortase-based ligations has stimulated efforts to discover other protein ligases with expanded capabilities. A promising candidate is butelase-1, which was isolated from the plant Clitoria ternatea (Nguyen et al. Reference Nguyen, Wang, Qiu, Hemu, Lian and Tam2014). Butelase-1 is the fastest ligase known with catalytic efficiencies as high as 542 000 M−1 s−1. Furthermore, it only requires the recognition sequence NHV on the acyl donor and produces ligation junctions with a minimal ‘scar’ (NX). Currently, the major limitation of this technology is that the enzyme is not available in recombinant form, and therefore has to be extracted and purified from the native plant (Nguyen et al. Reference Nguyen, Kam, Loo, Jansson, Pan and Tam2015). There are, however, evolutionary related ligases that may be more amenable to protein engineering approaches (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Wong, Nguyen, Tam, Lescar and Wu2017).

3.6 Genetic code expansion

After billions of years of evolution, Nature has engineered extraordinary functional diversity into proteins with only 20 amino acid building blocks. Yet, many of these building blocks are often modified post-translationally, clearly indicating the need of living organisms to enhance and modulate their protein repertoire with additional chemical functionalities. There are also organisms from all domains of life that can produce and incorporate other building blocks into their proteins. This includes selenocysteine, often called the 21st amino acid that provides a unique reactive site for precise tuning of biological function in cells. Interestingly, this amino acid is incorporated into proteins by a natural reassignment of the UGA stop codon coupled with the recognition of a specific structural element on the mRNA transcript known as the selenocysteine-insertion sequence (reviewed in (Metanis et al. Reference Metanis, Beld, Hilvert and Rappoport2009; Yoshizawa & Bock, Reference Yoshizawa and Bock2009)). Similarly, there are methane producing Archaea species that have evolved a specialized tRNA/aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (tRNA/aaRS) pair to exploit the UAG stop codon and insert pyrrolysine site-specifically into certain methyltransferase proteins (Srinivasan et al. Reference Srinivasan, James and Krzycki2002). Exploiting the natural translation machinery, protein engineers have worked hard to ‘persuade’ living organisms to incorporate additional building blocks into polypeptide chains (reviewed in (Liu & Schultz, Reference Liu and Schultz2010)). One approach involves the use of cell lines that are auxotrophic for one of the 20 amino acids, for example methionine, and that will only grow when the missing amino acid is included in the culture medium. Replacing this amino acid with a close structural analog that is utilized by the wild-type aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, results in incorporation of the unnatural amino acid (UAA) into overexpressed proteins. Since this results in global incorporation of the UAA, this approach is often used for the replacement of rare amino acids with their structural analogs. For example, methionine can be substituted with selenomethionine to provide a heavy atom for phasing crystallographic data (Barton et al. Reference Barton, Tzvetkova-Robev, Erdjument-Bromage, Tempst and Nikolov2006; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Hendrickson, Crouch and Satow1990).

A second approach involves the semi-synthesis of tRNAs that are pre-loaded with the UAA of interest (Hecht et al. Reference Hecht, Alford, Kuroda and Kitano1978; Noren et al. Reference Noren, Anthony-cahill, Griffith and Schultz1989). These tRNAs have been used in in vitro translation systems that bypass the need for a matching aaRS, and since the identity of the UAA is decoupled from the information content of the tRNA, any coding or blank codon can be used for reassignment (Cornish et al. Reference Cornish, Benson, Altenbach, Hideg, Hubbell and Schultz1994; Judice et al. Reference Judice, Gamble, Murphy, De Vos and Schultz1993; Koh et al. Reference Koh, Cornish and Schultz1997). While the semi-synthesis of acylated tRNAs can be technically challenging, more efficient production strategies have been developed. This includes flexizymes, flexible tRNA acylation ribozymes that accept a versatile range of aminoacyl substrates and tRNAs with different sequences (Goto et al. Reference Goto, Katoh and SUGA2011). Pre-loaded tRNAs can also be injected or transfected directly into living cells (England et al. Reference England, Zhang, Dougherty and Lester1999; Kohrer et al. Reference Kohrer, Yoo, Bennett, Schaack and Rajbhandary2003), although the success of such strategies has been limited by their short lifetimes in the cellular environment and challenges associated with in-cell delivery.

Today, UAA incorporation in living cells is almost exclusively performed following the strategy introduced by Peter Schultz and co-workers in 2001 (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Brock, Herberich and Schultz2001). This methodology, commonly referred to as amber suppression, relied on the development of an orthogonal tRNA/aaRS pair that could be expressed in E. coli and was used to incorporate O-methyl-L-tyrosine into dihydrofolate reductase with 99% fidelity. In the 15 years since this landmark study, the unnatural building block palette for genetic incorporation has grown more than 100 amino acids strong (Lang & Chin, Reference Lang and Chin2014; Liu & Schultz, Reference Liu and Schultz2010; Neumann-Staubitz & Neumann, Reference Neumann-Staubitz and Neumann2016). This includes amino acids carrying natural modifications (e.g. phosphoserine or acetyllysine), biophysical and structural probes, cross-linkers, reactive handles for bio-orthogonal reactions, and site-specific protein engineering functionalities that can modify their attendant proteins upon a specific cellular or chemical cue. Here, we describe the basic principles of the technology, review UAAs of particular interest to the structural biologist, and discuss current limitations and efforts to improve the efficiency of UAA incorporation.

3.6.1 Amber codon suppression in living cells

The successful incorporation of an UAA into a protein synthesized by a living cell requires several important considerations and components (Fig. 9a ). First and foremost, the UAA of interest must be chemically and metabolically stable, cell permeable or otherwise biosynthetically accessible in the cellular environment. It also must be tolerated by the ribosome and the cellular elongation factors without being recognized as a substrate by any of the endogenous synthetases. The UAA then requires its own unique codon, with the amber stop codon (UAG) being a popular choice due to its low occurrence in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. The successful site-specific incorporation of the UAA, however, rests on the presence of a dedicated tRNA/aaRS pair that is highly specific for the UAA of interest, yet orthogonal in the context of all endogenous tRNA/aaRS pairs. Developing such pairs for a chemically diverse set of UAA is currently one of the time consuming and difficult steps of this technology. Since tRNA recognition by aaRS is often species specific, it is sometimes possible to import a heterologous pair into the cell of interest and use it as a starting point to build orthogonality and specificity into the system. For example, many UAA incorporation systems in E. coli are based on the heterologous tRNATyr/TyrRS pair from Methanococcus jannaschii, while the tRNATyr/TyrRS and tRNALeu/LeuRS pairs from E. coli have been used in eukaryotic cells (reviewed in (Chin, Reference Chin2014)). The tRNAPyr/PyrRS pair from methanogenic bacteria that can incorporate pyrrolysine has also been a very useful tool, as it is orthogonal in E. coli, yeast and mammalian cell lines, and has allowed the incorporation of many lysine-based UAAs, including acetyllysine (Neumann et al. Reference Neumann, Peak-Chew and Chin2008). While these systems provide a useful starting point, it is usually necessary to use mutagenesis and rounds of negative and positive selection to improve on the selectivity and orthogonality of the pair. Directed evolution approaches can also be used for the generation of de novo tRNA/aaRS pairs, or to expand the function of other components of the translational machinery (reviewed in (Chin, Reference Chin2014)). Once an appropriate tRNA/aaRS pair is developed, however, the practical implementation of amber suppression for the UAA is relatively straightforward. E. coli cells, for example, can be transformed with two plasmids: (1) a plasmid encoding the protein of interest and an appropriate point mutation with the amber TAG codon, and (2) a plasmid carrying the appropriate DNA sequence to produce the optimized tRNA/aaRS pair. After addition of UAA to the media, gene expression is induced for both plasmids and the UAA is incorporated into the protein of interest by the bacterial translational machinery. To separate the full-length protein from prematurely truncated species, often a purification tag is added to the protein C-terminus – notably, these can involve ‘silent’ intein- or sortase-based purification tags (Batjargal et al. Reference Batjargal, Walters and Petersson2015; Warden-Rothman et al. Reference Warden-Rothman, Caturegli, Popik and Tsourkas2013). Well-established protocols for UAA incorporation are now available for yeast (Hancock et al. Reference Hancock, Uprety, Deiters and Chin2010), mammalian (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Groff, Guo, Ou, Cellitti, Geierstanger and Schultz2009) and insect cells (Koehler et al. Reference Koehler, Sauter, Wawryszyn, Girona, Gupta, Landry, Fritz, Radic, Hoffmann, Chen, Zou, Tan, Galik, Junttila, Stolt-Bergner, Pruneri, GYENESEI, Schultz, Biskup, Besir, Benes, Rappsilber, Jechlinger, Korbel, Berger, Braese and Lemke2016; Mukai et al. Reference Mukai, Wakiyama, Sakamoto and Yokoyama2010b) and amber suppression can even be performed in multicellular organisms including C. elegans (Greiss & Chin, Reference Greiss and Chin2011), D. melanogaster (Bianco et al. Reference Bianco, Townsley, Greiss, Lang and Chin2012), mice (Ernst et al. Reference Ernst, Krogager, Maywood, Zanchi, Beranek, Elliott, Barry, Hastings and Chin2016; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Kawaguchi, Coin, Xiang, O'leary, Slesinger and Wang2013) and plants (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhang, Sun, Pan, Zhou and Wang2013b).

Fig. 9. Unnatural amino acid (UAA) incorporation by amber suppression. (a) An orthogonal aminoacyl tRNA synthetase charges a matching tRNA with the UAA of interest. The ribosome incorporates the UAA into a growing polypeptide chain by decoding the amber stop codon (UAG) on the messenger RNA. The UAA toolbox includes UAAs that represent (b) protein post-translational modifications, (c) spectroscopic probes, (d) cross-linkers, (e) bio-orthogonal reactive handles.

3.6.2 The amber suppression toolbox

The amber suppression toolbox contains many UAAs designed with structural biology applications in mind (Fig. 9b–e ). For example, heavy atoms can be incorporated site-specifically for solving the phase problem in X-ray crystallography – appropriate UAAs include p-iodo-L-phenylalanine (Xie et al. Reference Xie, Wang, Wu, Brock, Spraggon and Schultz2004) and 3-iodo-L-tyrosine (Sakamoto et al. Reference Sakamoto, Murayama, Oki, Iraha, Kato-Murayama, Takahashi, Ohtake, Kobayashi, Kuramitsu, Shirouzu and Yokoyama2009), as well as metal-ion chelating amino acids (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Spraggon, Schultz and Wang2009b). For NMR spectroscopists, amber suppression offers a relatively cheap and efficient way to install site-specific isotopic labels in otherwise unlabeled proteins. Many of the NMR ‘friendly’ UAAs are fluorinated derivatives that exploit the unique spectroscopic properties of 19F as a reporter of global protein folding and dynamics (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Cellitti, Hao, Zhang, Jahnz, Summerer, Schultz, Uno and Geierstanger2010; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Yu, Liu, Qu, Gong, Liu, Li, Wang, He, Yi, Song, Tian, Xiao, Wang and Sun2015). Similarly, amber suppression has been used to install nitroxide spin labels for distance measurements by EPR, thus overcoming the problems often associated with cysteine-based approaches (Park et al. Reference Park, Wang, Radoicic, De Angelis, Berkamp and Opella2015; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Fedoseev, Bucker, Borbas, Peter, Drescher and Summerer2015). More importantly, however, amber suppression is a living cell protein engineering tool; thus, it is ideally suited for NMR or EPR studies designed to follow the structural fate of proteins in the cellular milieu.

Of particular interest to the structural biologist are UAAs carrying natural PTMs. Currently, amber suppression can directly incorporate the following modifications: phosphoserine (Rogerson et al. Reference Rogerson, Sachdeva, Wang, Haq, Kazlauskaite, Hancock, Huguenin-Dezot, Muqit, Fry, Bayliss and Chin2015), acetyllysine (Neumann et al. Reference Neumann, Peak-Chew and Chin2008), several lysine acylations (Gattner et al. Reference Gattner, Vrabel and Carell2013; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Kang, Kim, Chatterjee and Schultz2012), phosphotyrosine (Fan et al. Reference Fan, Ip and Soll2016) and sulfonated tyrosine (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Brustad, LIU and Schultz2007). To expand this toolbox, however, amber suppression can be used to install a reactive handle at the position of interest, and then the appropriate modification can be chemically generated after protein purification. Using this strategy, for example, the UAA δ-thiol-lysine can be incorporated, followed by traceless attachment of a ubiquitin moiety with NCL (Virdee et al. Reference Virdee, Kapadnis, Elliott, Lang, Madrzak, Nguyen, Riechmann and Chin2011). Similarly, methylated lysines can be generated by the incorporation of a suitable pre-cursor UAA (Nguyen et al. Reference Nguyen, Garcia Alai, Virdee and Chin2010; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zeng, Kurra, Wang, Tharp, Vatansever, Hsu, Dai, Fang and Liu2017). Phosphoserine, on the other hand, can serve as a starting point for the generation of dehydroalanine, which in turn can be converted into a number of modified side-chains (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Bower, Chalker, Bernardes, Wiewiora, Ng, Raj, Faulkner, Vallee, Phanumartwiwath, Coleman, Thezenas, Khan, Galan, Lercher, Schombs, Gerstberger, Palm-Espling, Baldwin, Kessler, Claridge, Mohammed and Davis2016).

Amber suppression also allows the facile installation of site-specific cross-linkers, a valuable tool for the identification of protein–protein and protein–ligand interactions both in vitro and in vivo. There are several options for UV-activatable cross-linkers that exploit different cross-linking mechanisms, and afford temporal and spatial control of the reaction. The oldest members of this toolbox are p-benzophenylalanine (Chin et al. Reference Chin, Martin, King, Wang and Schultz2002a) and p-azido-L-phenylalanine (Chin et al. Reference Chin, Santoro, Martin, King, Wang and Schultz2002b), both available for bacterial and eukaryotic systems, and extensively used for cross-linking experiments of purified proteins or in the cellular environment. More recently, diazirine-modified lysine-based amber suppression systems have been developed (Ai et al. Reference Ai, Shen, Sagi, Chen and Schultz2011; Chou et al. Reference Chou, Uprety, Davis, Chin and Deiters2011; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Lin, Song, Liu, Fu, Ge, Fu, Chang and Chen2011), exhibiting superior cross-linking efficiency, smaller structural perturbation effects and ideally suited for cross-linking experiments of lysine-rich proteins such as histones. UAAs that can cross-link proteins to nucleic acids are also available, and these include p-benzophenylalanine (Winkelman et al. Reference Winkelman, Vvedenskaya, Zhang, Zhang, Bird, Taylor, Gourse, Ebright and Nickels2016), and a furan-based cross-linker activated upon red-light irradiation (Schmidt & Summerer, Reference Schmidt and Summerer2013). Interestingly, p-azido-L-phenylalanine can also serve as an infrared (IR) spectroscopy probe, and as such can be used to report on the structural transitions of a protein along its activation pathway (Ye et al. Reference Ye, Zaitseva, Caltabiano, Schertler, Sakmar, Deupi and Vogel2010). Similarly, para-cyanophenylalanine can be installed as a site-specific and sensitive vibrational probe of ligand binding (Schultz et al. Reference Schultz, Supekova, Ryu, Xie, Perera and Schultz2006).

A significant fraction of the amber suppression UAA library has been designed for imaging and fluorescence-based biophysical applications. Some fluorescent UAAs can be incorporated directly into polypeptide chains and these include coumarin- and dansyl-based modifications (Kuhn et al. Reference Kuhn, Rubini, Muller and Skerra2011; Summerer et al. Reference Summerer, Chen, Wu, Deiters, Chin and Schultz2006), as well as environmentally sensitive aminonaphthalene-based probes available for both yeast and mammalian applications (Chatterjee et al. Reference Chatterjee, Guo, Lee and Schultz2013a; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Guo, Lemke, Dimla and Schultz2009a). More commonly, however, optical probes are attached site-specifically using bio-orthogonal reactions. In this case, amber suppression is used to install a reactive handle at a site in the polypeptide chain, while the fluorescent probe is modified with a compatible reactive functionality. The conjugation reaction can be carried out in vitro with purified components, or the optical label can be added to the media and/or delivered into cells for bio-orthogonal reaction chemistry within the cellular milieu. While this places important UAA-fluorescent label design constraints with respect to cell permeability, chemical stability and reaction kinetics, this approach allows the incorporation of optical labels that work at a variety of wavelengths, amid reduced background fluorescence. Currently, UAAs with a diverse set of functionalities for bio-orthogonal reactions are available (reviewed in (Lang & Chin, Reference Lang and Chin2014)), and it is likely that this list will become much more expansive in the future as new fast and specific bio-compatible approaches are developed (Section 3.7).

3.6.3 Limitations and future directions

The remarkable plasticity of the natural and evolved cellular protein synthesis machinery has allowed chemical biologists to create a large and diverse set of UAAs that can be incorporated into biological polymers assembled in vivo. Yet, the incorporation of many of these UAAs is inefficient, context dependent and essentially limited to the inclusion of a single modification per protein. Since UAA incorporation relies on the reassignment of natural stop codons, the suppressor tRNAs compete for binding sites with the endogeneous release factors that terminate translation. Therefore, truncations of the desired protein are often produced, resulting in compromised yields, complicated purification protocols and potential toxicity for the recombinant cell. In E. coli, translation termination involves release factor protein 1 (RF1) responsible for recognition of ochre (UAA) and amber (UAG) stop codons, and release factor protein 2 (RF2) that identifies ochre (UAA) and opal (UGA) stop codons. Thus, it has been possible to engineer bacterial strains that lack RF1 to enhance amber codon translation efficiency, and in particular improve the incorporation of the same UAA at multiple positions in the protein sequence (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Xu, Shen, Takimoto, Schultz, Schmitz, Xiang, Ecker, Briggs and Wang2011; Mukai et al. Reference Mukai, Hayashi, Iraha, Sato, Ohtake, Yokoyama and Sakamoto2010a). These strains, however, can be problematic as misincorporation of glutamine and codon skipping have also been reported (George et al. Reference George, Aguirre, Spratt, Bi, Jeffery, Shaw and O'donoghue2016). More dramatically, organisms can be genomically recoded to replace the UAG codon completely with the synonomous UAA stop codons, and free this new unique codon for more efficient amber suppression (Lajoie et al. Reference Lajoie, Rovner, Goodman, Aerni, Haimovich, Kuznetsov, Mercer, Wang, Carr, Mosberg, Rohland, Schultz, Jacobson, Rinehart, Church and Isaacs2013).

Protein yields are also affected by the lower efficiency of the evolved synthetases and suboptimal interactions of the tRNA with the wild-type elongation factors and ribosomes. These problems can be partially alleviated by the design of more efficient plasmid systems that have optimized promoters and can produce higher copy numbers of the synthetase and the tRNA. For example, the pEVOL and the pUltra plasmids have significantly increased incorporation efficiency in E. coli (Chatterjee et al. Reference Chatterjee, Sun, Furman, Xiao and Schultz2013b; Young et al. Reference Young, Ahmad, Yin and Schultz2010). For mammalian cells, protein expression is further affected by the transfection efficiency of the delivered constructs, thus it is usually desirable to incorporate all of the necessary genetic components (multiple copies of the synthetase and tRNA, gene of interest, engineered release factor, etc.) on the same plasmid ((Cohen & Arbely, Reference Cohen and Arbely2016). Baculovirus vectors that can deliver a large cargo of genetic material (>30 kb) to a variety of mammalian cells have also been developed for more efficient UAA incorporation (Chatterjee et al. Reference Chatterjee, Xiao, Bollong, Ai and Schultz2013c; Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Lewis, Igo, Polleux and Chatterjee2016). To avoid the heterogeneous expression levels associated with transient transfection and viral transduction altogether, the creation of stable mammalian cell lines capable of defined UAA incorporation is highly desirable and efforts have already been undertaken in this regard (Elsasser et al. Reference Elsasser, Ernst, Walker and Chin2016; Tian et al. Reference Tian, Lu, Manibusan, Sellers, Tran, Sun, Phuong, Barnett, Hehli, Song, Deguzman, Ensari, Pinkstaff, Sullivan, Biroc, Cho, Schultz, Dijoseph, Dougher, Ma, Dushin, Leal, Tchistiakova, Feyfant, Gerber and Sapra2014).