1. Introduction

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) is a large international collaboration, with the goal of building the world’s largest and most powerful radio telescope. The first phase of the SKA (‘SKA1’) will begin operations in the early 2020s and will comprise two separate arrays: SKA1-Low, which will consist of around 130 000 low-frequency dipoles in Western Australia, and SKA1-Mid, which will be composed of ![]() $\sim$200 dishes in the Karoo region of South Africa (Dewdney et al. Reference Dewdney, Turner, Braun, Santander-Vela, Waterson and Tan2016; Braun Reference Braun2017). The second phase, SKA2, will be an order of magnitude larger in collecting area than SKA1 and will take shape in the late 2020s.

$\sim$200 dishes in the Karoo region of South Africa (Dewdney et al. Reference Dewdney, Turner, Braun, Santander-Vela, Waterson and Tan2016; Braun Reference Braun2017). The second phase, SKA2, will be an order of magnitude larger in collecting area than SKA1 and will take shape in the late 2020s.

The science case for the SKA is extensive and diverse: the SKA will deliver spectacular new datasets that are expected to transform our understanding of astronomy, ranging from planet formation to the high-redshift Universe (Bourke et al. Reference Bourke2015). However, the SKA will also be a powerful machine for probing the frontiers of fundamental physics. To fully understand the SKA’s potential in this area, a focused workshop on ‘Fundamental Physics with the Square Kilometre Array’Footnote a was held in Mauritius in May 2017, in which radio astronomers and theoretical physicists came together to jointly consider ways in which the SKA can test and explore fundamental physics.

This paper is not a proceedings from this workshop, but rather is a white paper that fully develops the themes explored. The goal is to set out four broad directions for pursuing new physics with the SKA and to serve as a bridging document accessible for both the physics and astronomy communities. In Section 2, we consider cosmic dawn and reionisation, in Section 3 discuss strong gravity and pulsars, in Section 4 we examine cosmology and dark energy, and in Section 5 we review dark matter (DM) and astroparticle physics. In each of these sections, we introduce the topic, set out the key science questions, and describe the proposed experiments with the SKA.

2. Cosmic dawn and reionisation

Cosmic dawn represents the epoch of formation of the first stars and galaxies that eventually contributed to the reionisation of the Universe. This period is potentially observable through the 21-cm spin-flip transition of neutral hydrogen, redshifted to radio frequencies. In this section, we provide an overview of the ways in which we can use upcoming SKA observations of cosmic dawn and of the epoch of reionisation (EoR) to place constraints on fundamental physics. These include the possible effects of warm dark matter (WDM) on the 21-cm power spectrum during cosmic dawn, variations of fundamental constants such as the fine structure constant, measurements of the lensing convergence power spectrum, constraints on inflationary models, and cosmic microwave background (CMB) spectral distortions and dissipation processes. We describe foreseeable challenges in the detection and isolation of the fundamental physics parameters from the observations of cosmic dawn and reionisation, possible ways towards overcoming them through effective isolation of the astrophysics, synergies with other probes, and foreground removal techniques.

2.1. Introduction

Cosmologists seek to use the Universe as an experiment from which to learn about new physics. There has already been considerable success in extracting fundamental physics from the CMB and from large-scale structure (LSS) measurements from large galaxy surveys. These CMB and LSS observations cover only a small fraction of the total observable Universe, both in terms of cosmic history and observable volume. A promising new technique for providing observations over the redshift range ![]() $z=3-27$ is by measurements of the 21-cm hyperfine line of neutral hydrogen, which can be observed redshifted to radio frequencies detectable by the SKA (Koopmans et al. Reference Koopmans2015).

$z=3-27$ is by measurements of the 21-cm hyperfine line of neutral hydrogen, which can be observed redshifted to radio frequencies detectable by the SKA (Koopmans et al. Reference Koopmans2015).

Since hydrogen is ubiquitous in intergalactic space, 21-cm observations offer a route to mapping out fluctuations in density, which contain information about cosmological parameters. As the 21-cm line is affected by various types of radiation, observing it gives a way to detect and study some of the first astrophysical objects, including stars and black holes (BHs). Once detected, the 21-cm signal might also provide information about the high-redshift Universe that can constrain other physics, such as the effects of WDM, annihilation or scattering of DM, the variation of fundamental constants, and possibly also tests of inflationary models (Pritchard et al. Reference Pritchard2015).

These are exciting times for cosmic dawn and reionisation, as the pathfinder experiments Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) (Patil et al. Reference Patil2017), Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) (Dillon et al. Reference Dillon2015), Precision Array for Probing the Epoch of Reioniization (PAPER) (Ali et al. Reference Ali2015), and Hydrogen Epoch of Reionisation Array (HERA) (DeBoer et al. Reference DeBoer2017) have begun to collect data and set upper limits on the 21-cm power spectrum, while Experiment to Detect the Epoch of Reionization Signature (EDGES) has reported a tentative detection (Bowman et al. Reference Bowman, Rogers, Monsalve, Mozdzen and Mahesh2018). It is likely that in the next few years, the cosmological 21-cm signal will open a new window into a previously unobserved period of cosmic history.

The rest of this section is organised as follows. In Section 2.2, we present a brief overview of the theory and observations related to cosmic dawn and the EoR, and the various physical processes that influence the magnitude of the signal from these epochs. We summarise the status of observations in the field, including the upper limits to date from various experiments. We also provide a brief overview of the upcoming observations and modelling of the reionisation epoch. In Section 2.3, we review aspects of fundamental physics that can be probed with the SKA, and in Section 2.4 we discuss some of the challenges to doing this. We provide a summary in Section 2.5.

2.2. Cosmic dawn and reionisation: Theory and observations

2.2.1 Overview of the 21-cm signal

The 21-cm line of neutral hydrogen corresponds to the transition between the singlet and triplet hyperfine levels of its electronic ground state, resulting from the interaction of proton and electron spins. The resulting transition has a rest frame frequency of 1.4 GHz, that is, a wavelength of 21 cm. The electric dipole transition between the ground and excited hyperfine levels is forbidden due to parity; the lowest order transition occurs via a magnetic dipole, owing to which the triplet level has a vacuum lifetime of ![]() $\simeq\! 11 \ {\rm Myr}$. Due to this long lifetime, the dominant channels for the decay of the excited levels are either non-radiative (atomic collisions; Allison & Dalgarno Reference Allison and Dalgarno1969; Zygelman Reference Zygelman2005) or depend on the existing radiation field (stimulated emission by CMB photons, or optical pumping by UV photons; Wouthuysen Reference Wouthuysen1952; Field Reference Field1958). This makes the relative population of the hyperfine levels a sensitive probe of the thermal state and density of the high-redshift intergalactic medium (IGM) and of early sources of ultraviolet radiation (Sunyaev & Zeldovich Reference Sunyaev and Zeldovich1975; Hogan & Rees Reference Hogan and Rees1979; Madau et al. Reference Madau, Meiksin and Rees1997).

$\simeq\! 11 \ {\rm Myr}$. Due to this long lifetime, the dominant channels for the decay of the excited levels are either non-radiative (atomic collisions; Allison & Dalgarno Reference Allison and Dalgarno1969; Zygelman Reference Zygelman2005) or depend on the existing radiation field (stimulated emission by CMB photons, or optical pumping by UV photons; Wouthuysen Reference Wouthuysen1952; Field Reference Field1958). This makes the relative population of the hyperfine levels a sensitive probe of the thermal state and density of the high-redshift intergalactic medium (IGM) and of early sources of ultraviolet radiation (Sunyaev & Zeldovich Reference Sunyaev and Zeldovich1975; Hogan & Rees Reference Hogan and Rees1979; Madau et al. Reference Madau, Meiksin and Rees1997).

Radio observations of this line are frequently used to map the velocity of neutral hydrogen (H i) gas in the Milky Way or in nearby galaxies, but currently it has not been detected in emission at redshifts ![]() $z>1$. When considering the 21-cm line as a cosmological probe, it is standard to describe the measured intensity in terms of a brightness temperatureFootnote b and to consider the observed brightness temperature relative to some background source, typically either the CMB or a radio-bright point source. For cosmology, it is most useful to consider the case of the CMB backlight, for which the 21-cm signal will then take the form of a spectral distortion over the whole sky.

$z>1$. When considering the 21-cm line as a cosmological probe, it is standard to describe the measured intensity in terms of a brightness temperatureFootnote b and to consider the observed brightness temperature relative to some background source, typically either the CMB or a radio-bright point source. For cosmology, it is most useful to consider the case of the CMB backlight, for which the 21-cm signal will then take the form of a spectral distortion over the whole sky.

The observable quantity is the brightness temperature, ![]() $\delta T_{\rm b}$, of the 21-cm line against the CMB, which is set by radiative transfer through H i regions. The brightness temperature of 21-cm radiation can be expressed as

$\delta T_{\rm b}$, of the 21-cm line against the CMB, which is set by radiative transfer through H i regions. The brightness temperature of 21-cm radiation can be expressed as

$$

\begin{align}

\nonumber\\[-10pt] \delta T_{b}(\nu) &= \frac{T_{s} -

T_{\gamma}}{1+z} (1 - e^{-\tau_{\nu_0}}) \nonumber \\[3pt]

& \approx 27 x_{\rm H {i}} (1+\delta_{b}) \left(\frac{H}{dv_r/dr + H}\right)

\left(1 - \frac{T_{\rm cmb}}{T_{s}} \right) \nonumber \\[3pt]

& \times \left( \frac{1+z}{10} \frac{0.15}{\Omega_{\rm m}

h^2}\right)^{1/2} \left( \frac{\Omega_b h^2}{0.023} \right) {\rm

mK},

\label{eqn1}\end{align}

$$

$$

\begin{align}

\nonumber\\[-10pt] \delta T_{b}(\nu) &= \frac{T_{s} -

T_{\gamma}}{1+z} (1 - e^{-\tau_{\nu_0}}) \nonumber \\[3pt]

& \approx 27 x_{\rm H {i}} (1+\delta_{b}) \left(\frac{H}{dv_r/dr + H}\right)

\left(1 - \frac{T_{\rm cmb}}{T_{s}} \right) \nonumber \\[3pt]

& \times \left( \frac{1+z}{10} \frac{0.15}{\Omega_{\rm m}

h^2}\right)^{1/2} \left( \frac{\Omega_b h^2}{0.023} \right) {\rm

mK},

\label{eqn1}\end{align}

$$ where ![]() $T_s$ is the gas spin temperature,

$T_s$ is the gas spin temperature, ![]() $\tau_{\nu_0}$ is the optical depth at the 21-cm frequency

$\tau_{\nu_0}$ is the optical depth at the 21-cm frequency ![]() $\nu_0$,

$\nu_0$, ![]() $x_{\rm H {i}}$ is the neutral hydrogen fraction of the IGM,

$x_{\rm H {i}}$ is the neutral hydrogen fraction of the IGM, ![]() $\delta_{b}({\bf x},

z) \equiv \rho/\bar{\rho} - 1$ is the evolved (Eulerian) density contrast of baryons, H(z) is the Hubble parameter,

$\delta_{b}({\bf x},

z) \equiv \rho/\bar{\rho} - 1$ is the evolved (Eulerian) density contrast of baryons, H(z) is the Hubble parameter, ![]() $dv_r/dr$ is the co-moving gradient of the line-of-sight component of the peculiar velocity, and all quantities are evaluated at redshift

$dv_r/dr$ is the co-moving gradient of the line-of-sight component of the peculiar velocity, and all quantities are evaluated at redshift ![]() $z=\nu_0/\nu - 1$;

$z=\nu_0/\nu - 1$; ![]() $\Omega_b$ is the present-day baryon density and h is the present-day Hubble factor. Therefore, the brightness temperature of the 21-cm line is very sensitive to the spin temperature of the gas and to the CMB temperature (Mesinger et al. Reference Mesinger, Furlanetto and Cen2011).

$\Omega_b$ is the present-day baryon density and h is the present-day Hubble factor. Therefore, the brightness temperature of the 21-cm line is very sensitive to the spin temperature of the gas and to the CMB temperature (Mesinger et al. Reference Mesinger, Furlanetto and Cen2011).

The 21-cm line is a unique window into cosmological epochs at which the Universe is dominantly composed of neutral hydrogen atoms. These encompass the period from cosmological recombination (a redshift of ![]() $z = 1100$, or a proper time of

$z = 1100$, or a proper time of ![]() $0.38 \ {\rm Myr}$ after the Big Bang) to the end of the reionisation era (a redshift of

$0.38 \ {\rm Myr}$ after the Big Bang) to the end of the reionisation era (a redshift of ![]() $z \simeq 6$, or a proper time of

$z \simeq 6$, or a proper time of ![]() $\simeq 1.2 \ {\rm Gyr}$ after the Big Bang). Except for the last epoch, the rest of this period is unconstrained by current observations and is fertile ground for exploration with new observations. There are several processes that contribute to the evolution of the brightness temperature of the 21-cm radiation. Observations of the brightness temperature, either through direct imaging or statistical measures of its fluctuations, can then inform us about the physical state of the neutral gas and the nature of its perturbations (Koopmans et al. Reference Koopmans2015).

$\simeq 1.2 \ {\rm Gyr}$ after the Big Bang). Except for the last epoch, the rest of this period is unconstrained by current observations and is fertile ground for exploration with new observations. There are several processes that contribute to the evolution of the brightness temperature of the 21-cm radiation. Observations of the brightness temperature, either through direct imaging or statistical measures of its fluctuations, can then inform us about the physical state of the neutral gas and the nature of its perturbations (Koopmans et al. Reference Koopmans2015).

1. During the period from ![]() $z \simeq 1100$ to

$z \simeq 1100$ to ![]() $z \simeq 200$, the gas temperature is kept close to that of the CMB by Thomson scattering of residual free electrons (Chluba & Sunyaev Reference Chluba and Sunyaev2012). Atomic collisions and optical pumping by Lyman-

$z \simeq 200$, the gas temperature is kept close to that of the CMB by Thomson scattering of residual free electrons (Chluba & Sunyaev Reference Chluba and Sunyaev2012). Atomic collisions and optical pumping by Lyman-![]() $\alpha$ photons from the epoch of cosmological recombination can lead to a small but non-negligible brightness temperature in the 21-cm line (Fialkov & Loeb Reference Fialkov and Loeb2013; Breysse et al. Reference Breysse, Ali-Haïmoud and Hirata2018).

$\alpha$ photons from the epoch of cosmological recombination can lead to a small but non-negligible brightness temperature in the 21-cm line (Fialkov & Loeb Reference Fialkov and Loeb2013; Breysse et al. Reference Breysse, Ali-Haïmoud and Hirata2018).

2. The epoch from ![]() $z \simeq 200$ to

$z \simeq 200$ to ![]() $z\simeq30$ is known as the Dark Ages; through this period, the CMB temperature and the gas temperature differ substantially, and atomic collisions are sufficiently fast to set the spin temperature to the latter and lead to a 21-cm signal at a detectable level. The amplitude of the signal is set by the linear evolution of fluctuations on large scales (Loeb & Zaldarriaga Reference Loeb and Zaldarriaga2004; Lewis & Challinor Reference Lewis and Challinor2007) and the bulk flows that set the baryonic Jeans scale (Tseliakhovich & Hirata Reference Tseliakhovich and Hirata2010; Ali-Haïmoud et al. Reference Ali-Haïmoud, Meerburg and Yuan2014). If detected, the 21-cm signal from this epoch would be the ultimate probe of primordial cosmological fluctuations. Assuming cosmic variance limits, the 21-cm signal could probe extremely faint inflationary gravitational wave (GW) backgrounds (down to tensor-to-scalar ratios of

$z\simeq30$ is known as the Dark Ages; through this period, the CMB temperature and the gas temperature differ substantially, and atomic collisions are sufficiently fast to set the spin temperature to the latter and lead to a 21-cm signal at a detectable level. The amplitude of the signal is set by the linear evolution of fluctuations on large scales (Loeb & Zaldarriaga Reference Loeb and Zaldarriaga2004; Lewis & Challinor Reference Lewis and Challinor2007) and the bulk flows that set the baryonic Jeans scale (Tseliakhovich & Hirata Reference Tseliakhovich and Hirata2010; Ali-Haïmoud et al. Reference Ali-Haïmoud, Meerburg and Yuan2014). If detected, the 21-cm signal from this epoch would be the ultimate probe of primordial cosmological fluctuations. Assuming cosmic variance limits, the 21-cm signal could probe extremely faint inflationary gravitational wave (GW) backgrounds (down to tensor-to-scalar ratios of ![]() $r \sim

10^{-9}$; Masui & Pen Reference Masui and Pen2010; Book et al. Reference Book, Kamionkowski and Schmidt2012) and low levels of primordial non-gaussianities (down to parameters

$r \sim

10^{-9}$; Masui & Pen Reference Masui and Pen2010; Book et al. Reference Book, Kamionkowski and Schmidt2012) and low levels of primordial non-gaussianities (down to parameters ![]() $f_{\rm NL} \simeq

0.03$; Cooray Reference Cooray2006; Pillepich et al. Reference Pillepich, Porciani and Matarrese2007; Joudaki et al. Reference Joudaki, Doré, Ferramacho, Kaplinghat and Santos2011; Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Ali-Haïmoud and Kamionkowski2015). Due to the low frequencies of the signal from this epoch, the observational prospects are not promising in the short to medium term.

$f_{\rm NL} \simeq

0.03$; Cooray Reference Cooray2006; Pillepich et al. Reference Pillepich, Porciani and Matarrese2007; Joudaki et al. Reference Joudaki, Doré, Ferramacho, Kaplinghat and Santos2011; Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Ali-Haïmoud and Kamionkowski2015). Due to the low frequencies of the signal from this epoch, the observational prospects are not promising in the short to medium term.

3. The period covering redshifts ![]() $z \simeq 30-15$ is called the cosmic dawn epoch, owing to the birth of the first stars (in sufficient numbers to affect 21-cm observations). The radiation emitted by these first sources significantly changes the nature of the mean and fluctuating 21-cm signal due to two main reasons: (i) optical pumping of the hyperfine levels due to Lyman-

$z \simeq 30-15$ is called the cosmic dawn epoch, owing to the birth of the first stars (in sufficient numbers to affect 21-cm observations). The radiation emitted by these first sources significantly changes the nature of the mean and fluctuating 21-cm signal due to two main reasons: (i) optical pumping of the hyperfine levels due to Lyman-![]() $\alpha$ photons, known as the Wouthuysen–Field effect, which serves to couple the spin temperature of the gas to the ambient Lyman-

$\alpha$ photons, known as the Wouthuysen–Field effect, which serves to couple the spin temperature of the gas to the ambient Lyman-![]() $\alpha$ radiation (Hirata Reference Hirata2006), and (ii) heating of the gas by X-rays (Furlanetto Reference Furlanetto2006; Pritchard & Furlanetto Reference Pritchard and Furlanetto2007; Fialkov et al. Reference Fialkov, Barkana and Visbal2014). In addition, non-linear structure formation (Ahn et al. Reference Ahn, Shapiro, Alvarez, Iliev, Martel and Ryu2006; Kuhlen et al. Reference Kuhlen, Madau and Montgomery2006) and baryonic bulk flows (Visbal et al. Reference Visbal, Barkana, Fialkov, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2012; McQuinn & O’Leary Reference McQuinn and O’Leary2012; Fialkov et al. Reference Fialkov, Barkana, Visbal, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2013) imprint their effects on the signal. Primordial magnetic fields can also lead to features in the cosmological 21-cm signal during these epochs (Shiraishi et al. Reference Shiraishi, Tashiro and Ichiki2014).

$\alpha$ radiation (Hirata Reference Hirata2006), and (ii) heating of the gas by X-rays (Furlanetto Reference Furlanetto2006; Pritchard & Furlanetto Reference Pritchard and Furlanetto2007; Fialkov et al. Reference Fialkov, Barkana and Visbal2014). In addition, non-linear structure formation (Ahn et al. Reference Ahn, Shapiro, Alvarez, Iliev, Martel and Ryu2006; Kuhlen et al. Reference Kuhlen, Madau and Montgomery2006) and baryonic bulk flows (Visbal et al. Reference Visbal, Barkana, Fialkov, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2012; McQuinn & O’Leary Reference McQuinn and O’Leary2012; Fialkov et al. Reference Fialkov, Barkana, Visbal, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2013) imprint their effects on the signal. Primordial magnetic fields can also lead to features in the cosmological 21-cm signal during these epochs (Shiraishi et al. Reference Shiraishi, Tashiro and Ichiki2014).

4. Finally, during the epochs covered by ![]() $z \simeq 15-6$, the ionising photons from the radiation sources lead to the permeation of HII regions, and the mean signal drops, reaching close to zero as reionisation is completed.

$z \simeq 15-6$, the ionising photons from the radiation sources lead to the permeation of HII regions, and the mean signal drops, reaching close to zero as reionisation is completed.

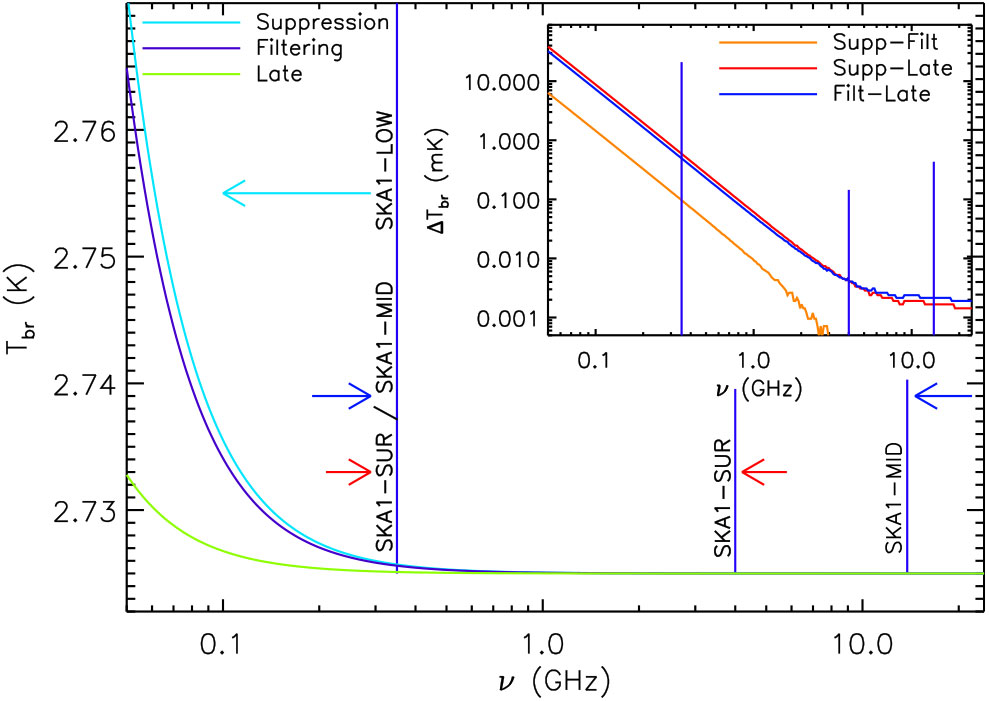

Significant progress has been made in condensing these rich astrophysical effects into simple semi-analytical prescriptions that capture the large-scale features of the 21-cm signal during this period (Furlanetto et al. Reference Furlanetto, Zaldarriaga and Hernquist2004a,b; Mesinger & Furlanetto Reference Mesinger and Furlanetto2007; Mesinger et al. Reference Mesinger, Furlanetto and Cen2011; Visbal et al. Reference Visbal, Barkana, Fialkov, Tseliakhovich and Hirata2012). For a fiducial model described by Mesinger et al. (Reference Mesinger, Furlanetto and Cen2011) and developed with the publicly available code 21CMFAST, the various evolutionary stages of the signal are illustrated in Figure 1. The terms in the figure denote the spin temperature of the gas ![]() $T_s$, the CMB temperature

$T_s$, the CMB temperature ![]() $T_{\gamma}$, and the gas kinetic temperature

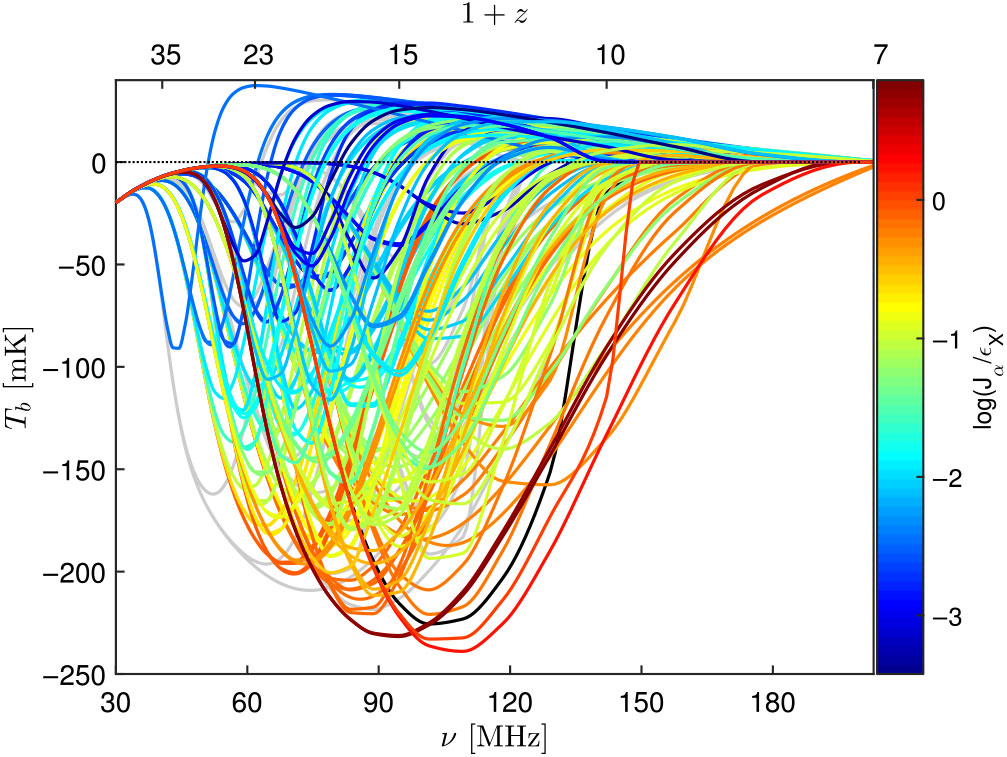

$T_{\gamma}$, and the gas kinetic temperature ![]() $T_K$; the figure illustrates astrophysical effects on the signal that include decoupling from the CMB, the Wouthuysen–Field coupling, and X-ray heating. Figure 2 shows the wide range of possibilities for the sky-averaged signal (‘the 21-cm global signal’). Its characteristic structure of peaks and troughs encodes information about global cosmic events. Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Fialkov, Barkana and Lotem2017) discussed 193 different combinations of astrophysical parameters, illustrating the great current uncertainty in the predicted 21-cm signal.

$T_K$; the figure illustrates astrophysical effects on the signal that include decoupling from the CMB, the Wouthuysen–Field coupling, and X-ray heating. Figure 2 shows the wide range of possibilities for the sky-averaged signal (‘the 21-cm global signal’). Its characteristic structure of peaks and troughs encodes information about global cosmic events. Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Fialkov, Barkana and Lotem2017) discussed 193 different combinations of astrophysical parameters, illustrating the great current uncertainty in the predicted 21-cm signal.

Figure 1. Evolution of spin temperature ![]() $T_s$, gas temperature

$T_s$, gas temperature ![]() $T_K$, and CMB temperature

$T_K$, and CMB temperature ![]() $T_{\gamma}$. This figure is taken from Mesinger et al. (Reference Mesinger, Furlanetto and Cen2011).

$T_{\gamma}$. This figure is taken from Mesinger et al. (Reference Mesinger, Furlanetto and Cen2011).

Figure 2. The 21-cm global signal as a function of redshift, for the 193 different astrophysical models discussed in Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Fialkov, Barkana and Lotem2017). The colour (see the colour bar on the right) indicates the ratio between the Ly![]() $\alpha$ intensity (in units of erg s–1 cm–2 Hz–1 sr–1) and the X-ray heating rate (in units of eV s–1 baryon–1) at the minimum point. Grey curves indicate cases with

$\alpha$ intensity (in units of erg s–1 cm–2 Hz–1 sr–1) and the X-ray heating rate (in units of eV s–1 baryon–1) at the minimum point. Grey curves indicate cases with ![]() $\tau>0.09$, and a non-excluded case with the X-ray efficiency of X-ray sources set to zero; these cases are all excluded from the colour bar range. Figure taken from Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Fialkov, Barkana and Lotem2017).

$\tau>0.09$, and a non-excluded case with the X-ray efficiency of X-ray sources set to zero; these cases are all excluded from the colour bar range. Figure taken from Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Fialkov, Barkana and Lotem2017).

The most robust way of probing cosmology with the brightness temperature may be redshift-space distortions (RSDs); (Barkana & Loeb 2005 a; Furlanetto et al. Reference Furlanetto2009); see however Shapiro et al. (Reference Shapiro, Mao, Iliev, Mellema, Datta, Ahn and Koda2013) and Fialkov et al. (Reference Fialkov, Barkana and Cohen2015). Alternatively, a discussion of the bispectrum is provided by Saiyad Ali et al. (Reference Saiyad Ali, Bharadwaj and Pandey2006). More futuristic possibilities include probing extremely weak primordial magnetic fields (![]() $\sim\! 10^{-21} \ {\rm G}$ scaled to

$\sim\! 10^{-21} \ {\rm G}$ scaled to ![]() $z=0$) using their breaking of the line-of-sight symmetry of the 21-cm power spectrum (Venumadhav et al. Reference Venumadhav, Oklopˇci´c, Gluscevic, Mishra and Hirata2017) and inflationary GWs through the circular polarisation of the 21-cm line (Hirata et al. Reference Hirata, Mishra and Venumadhav2018; Mishra & Hirata Reference Mishra and Hirata2018).

$z=0$) using their breaking of the line-of-sight symmetry of the 21-cm power spectrum (Venumadhav et al. Reference Venumadhav, Oklopˇci´c, Gluscevic, Mishra and Hirata2017) and inflationary GWs through the circular polarisation of the 21-cm line (Hirata et al. Reference Hirata, Mishra and Venumadhav2018; Mishra & Hirata Reference Mishra and Hirata2018).

2.2.2. Status of 21-cm experiments

Observational attempts to detect the cosmological 21-cm signal have made significant progress in the last few years, with upper limits from interferometers beginning to make contact with the space of plausible models. Broadly speaking, there are two classes of 21-cm experiments: those attempting to measure the sky-averaged ‘global’ 21-cm signal and those attempting to measure the 21-cm brightness temperature fluctuations. A natural comparison is to the CMB where some experiments target either spectral distortions to the CMB blackbody (BB), while others measure CMB anisotropies.

Experiments targeting the global signal include EDGES (Bowman et al. Reference Bowman, Morales and Hewitt2008), SARAS (Patra et al. Reference Patra, Subrahmanyan, Raghunathan and Udaya Shankar2013), LEDAFootnote c, SCI-HI (Voytek et al. Reference Voytek, Natarajan, Jáuregui García, Peterson and López- Cruz2014), and a proposed lunar experiment DARE (Burns et al. Reference Burns2012). To detect the 21-cm global signal, in principle, only a single radio dipole is necessary, as its large beam will average over fluctuations to probe the averaged all sky signal. For these experiments, raw sensitivity is typically not the limiting factor; the main challenges are twofold—ensuring absolute calibration of the dipole and removing foregrounds.

In Bowman et al. (Reference Bowman, Morales and Hewitt2008), EDGES reported the first lower limit on the duration of reionisation by searching for a sharp step in the 21-cm global signal, which is, in principle, distinguishable from the smooth foregrounds (Pritchard & Loeb Reference Pritchard and Loeb2010). More sophisticated techniques have been developed based upon forward modelling the signal, foregrounds, and instrument response in a Bayesian framework and prospects appear to be good (Harker et al. Reference Harker, Pritchard, Burns and Bowman2012).

Recently, EDGES reported a detection of the 21-cm global signal in absorption at a frequency of 78 MHz, corresponding to the redshift ![]() $z \sim 17$ (Bowman et al. Reference Bowman, Rogers, Monsalve, Mozdzen and Mahesh2018). The absorption profile was flattened, with an amplitude about twice that predicted by several current models. The signal amplitude could possibly be evidence of interactions between (a subcomponent of) DM and baryons (e.g., Barkana Reference Barkana2018; Barkana et al. Reference Barkana2018; Muñoz & Loeb Reference Muñoz and Loeb2018), which may have led to cooling of the IGM prior to reionisation. Further investigation, as well as independent confirmation from other facilities, would lead to exciting prospects for constraining fundamental physics.

$z \sim 17$ (Bowman et al. Reference Bowman, Rogers, Monsalve, Mozdzen and Mahesh2018). The absorption profile was flattened, with an amplitude about twice that predicted by several current models. The signal amplitude could possibly be evidence of interactions between (a subcomponent of) DM and baryons (e.g., Barkana Reference Barkana2018; Barkana et al. Reference Barkana2018; Muñoz & Loeb Reference Muñoz and Loeb2018), which may have led to cooling of the IGM prior to reionisation. Further investigation, as well as independent confirmation from other facilities, would lead to exciting prospects for constraining fundamental physics.

In parallel, several new radio interferometers—LOFAR, PAPER, MWA, HERA—are targeting the spatial fluctuations of the 21-cm signal, due to the ionised bubbles during cosmic reionisation as well as Lyman-![]() $\alpha$ fluctuations (Barkana & Loeb Reference Barkana and Loeb2005b) and X-ray heating fluctuations (Pritchard & Furlanetto Reference Pritchard and Furlanetto2007) during cosmic dawn. These telescopes take different approaches to their design, which gives each different pros and cons. LOFAR in the Netherlands is a general purpose observatory with a moderately dense core and long baselines (in the case of the international stations, extending as far as Ireland). The MWA in Western Australia is composed of 256 tiles of 16 antennas distributed within about 1-km baselines. PAPER (now complete) was composed of 128 dipoles mounted in a small dish and focused on technological development and testing of redundant calibration. HERA in South Africa will be a hexagonal array of 330

$\alpha$ fluctuations (Barkana & Loeb Reference Barkana and Loeb2005b) and X-ray heating fluctuations (Pritchard & Furlanetto Reference Pritchard and Furlanetto2007) during cosmic dawn. These telescopes take different approaches to their design, which gives each different pros and cons. LOFAR in the Netherlands is a general purpose observatory with a moderately dense core and long baselines (in the case of the international stations, extending as far as Ireland). The MWA in Western Australia is composed of 256 tiles of 16 antennas distributed within about 1-km baselines. PAPER (now complete) was composed of 128 dipoles mounted in a small dish and focused on technological development and testing of redundant calibration. HERA in South Africa will be a hexagonal array of 330 ![]() $\times$ 14 m dishes and, like PAPER, aims to exploit redundant calibration.

$\times$ 14 m dishes and, like PAPER, aims to exploit redundant calibration.

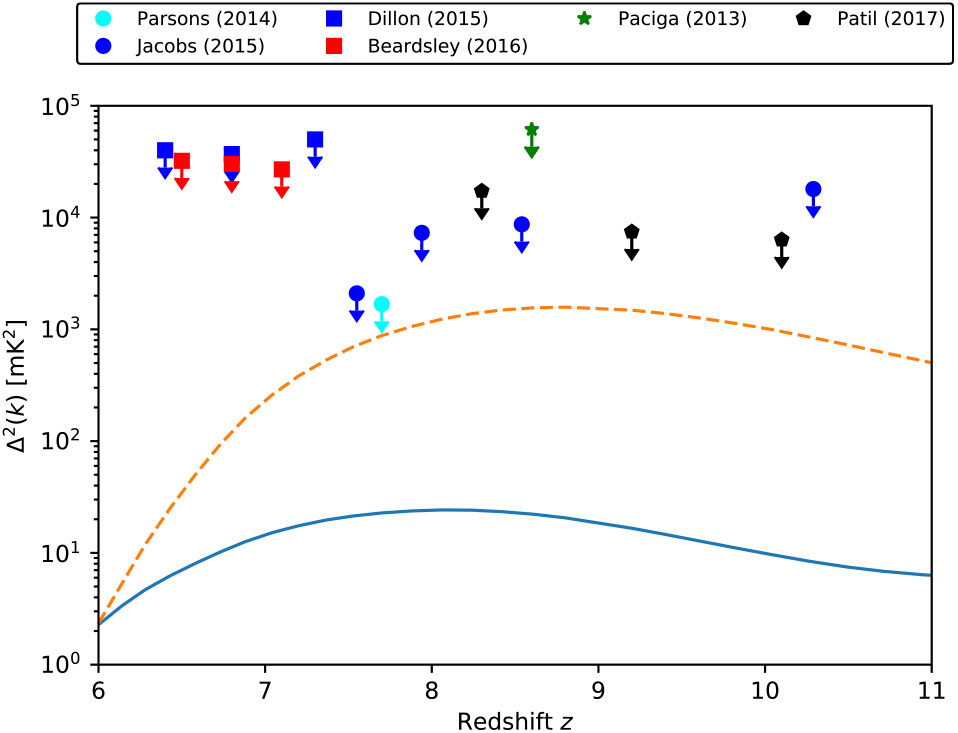

These experiments have begun setting upper limits on the 21-cm power spectrum that are summarised in Figure 3. At present, the best constraints are about two orders of magnitude above the expected 21-cm power spectrum. However, as noted earlier, there is considerable uncertainty in these predictions, and in the case of an unheated IGM, a much larger signal can be produced. Pober et al. (Reference Pober2015) interpreted now-retracted upper limits from Ali et al. (Reference Ali2015) as a constraint on the IGM temperature, ruling out an entirely unheated Universe at ![]() $z=8.4$. The current upper limits typically represent only a few tens of hours of integration time, compared to the

$z=8.4$. The current upper limits typically represent only a few tens of hours of integration time, compared to the ![]() $\sim\!1000$ h needed for the desired sensitivity. Systematic effects, especially instrumental calibration, currently limit the amount of integration time that can be usefully reduced. Overcoming these limitations is the major goal of all these experiments and steady progress is being made.

$\sim\!1000$ h needed for the desired sensitivity. Systematic effects, especially instrumental calibration, currently limit the amount of integration time that can be usefully reduced. Overcoming these limitations is the major goal of all these experiments and steady progress is being made.

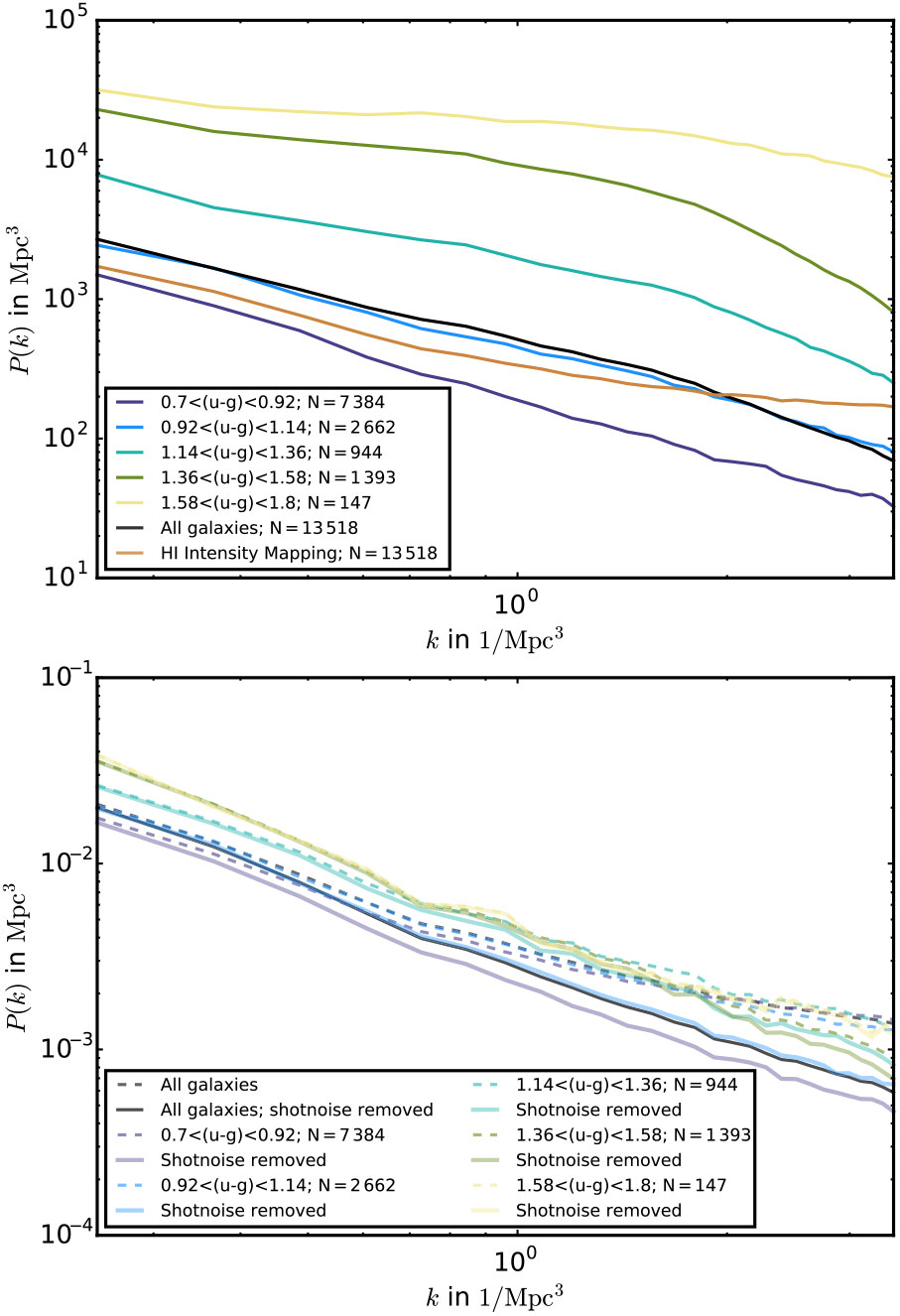

Figure 3. Summary of current constraints on the 21-cm power spectrum as a function of redshift. Since constraints are actually a function of both redshift and wavenumber k, only the best constraint for each experiment has been plotted. Here are plotted results for GMRT (Paciga et al. Reference Paciga2013), PAPER32 (Parsons et al. Reference Parsons2014; Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs2015), MWA128 (Dillon et al. Reference Dillon2015; Beardsley et al. Reference Beardsley2016), and LOFAR (Patil et al. Reference Patil2017). Two comparison 21-cm signals calculated using 21CMFAST are shown to give a sense of the target range—one with fiducial values (solid blue curve) and a second with negligible heating (dashed orange curve).

2.3. Fundamental physics from the EoR

In the previous section, we listed the main astrophysical and cosmological processes that contribute to the brightness temperature evolution of the 21-cm signal and the status of the EoR 21-cm experiments. In this section, we provide glimpses into the details of some of the important constraints on fundamental physics that may be garnered from the EoR and cosmic dawn.

2.3.1. Cosmology from the EoR

A key advantage of 21-cm observations is that they open up a new epoch of cosmological volume containing many linear modes of the density field, which can greatly increase the precision of cosmological parameter constraints. Typically, cosmology enters into the 21-cm signal through its dependence on the density field, so that the 21-cm signal can be viewed as a biased tracer in a similar way to low-redshift galaxy surveys. The challenge is that obtaining fundamental physics from the 21-cm signal requires disentangling the ‘gastrophysics’—the effect of galaxies and other astrophysical sources on the hydrogen gas—from the signature of physics. This is not an easy challenge, since the effect of astrophysics is typically dominant over that of fundamental physics effects, which are often subtle and desired to be measured at high precision. At this moment in time, our understanding of the nuances of both the 21-cm signal and the observations is still relatively limited, but there are reasons for some optimism.

Broadly speaking, there are several routes to fundamental physics from the 21-cm signal:

1. Treat the 21-cm signal as a biased tracer of the density field, and via joint analysis, constrain cosmological parameters.

2. Look for the direct signature of energy injection by exotic processes in the 21-cm signal, which is sensitive to the cosmic thermal history.

3. The clustering of ionised regions or heating will reflect the underlying clustering of galaxies, and so will contain information about the density field, for example, non-gaussianity signatures or the lack of small-scale structure due to WDM.

4. Line-of-sight effects, such as weak lensing or the integrated Sachs–Wolfe (ISW) effect, where the 21-cm signal is primarily just a diffuse background source.

5. Look for unique signatures of fundamental physics, for example, the variation of the fine structure constant, which do not depend in detail upon fluctuations in the 21-cm brightness.

21-cm observations may also be useful in breaking degeneracies present in other datasets (Kern et al. Reference Kern, Liu, Parsons, Mesinger and Greig2017). For example, measurements of the reionisation history may allow the inference of the optical depth to the CMB, breaking a degeneracy with neutrino mass (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Pritchard, Allison, Parsons, Seljak and Sherwin2016).

2.3.2. Exotic energy injection

As discussed in Section 2.2.1, the 21-cm signal is sensitive to the underlying gas temperature through the 21-cm spin temperature. This makes the 21-cm line a rather unique probe of the thermal history of the Universe during the EoR and the cosmic dawn. Provided that the IGM temperature is not too much larger than the CMB temperature (so that the ![]() $1 -

T_{\rm CMB}/T_s$ term retains its dependence on

$1 -

T_{\rm CMB}/T_s$ term retains its dependence on ![]() $T_s$), we can use the Universe as a calorimeter to search for energy injection from a wide range of processes. Distinguishing different sources of heat will depend upon them having unique signatures in how that energy is deposited spatially or temporally.

$T_s$), we can use the Universe as a calorimeter to search for energy injection from a wide range of processes. Distinguishing different sources of heat will depend upon them having unique signatures in how that energy is deposited spatially or temporally.

After thermal decoupling at ![]() $z\sim150$, the gas temperature is expected to cool adiabatically, with a phase of X-ray heating from galaxies warming the gas, before the photoionisation heating during reionisation raises the temperature to

$z\sim150$, the gas temperature is expected to cool adiabatically, with a phase of X-ray heating from galaxies warming the gas, before the photoionisation heating during reionisation raises the temperature to ![]() $\sim\!10^4{\,\rm K}$ (e.g., Furlanetto Reference Furlanetto2006; McQuinn & O’Leary Reference McQuinn and O’Leary2012). There is considerable uncertainty in these latter stages, which depend upon poorly known properties of the galaxies and the cosmic star formation history.

$\sim\!10^4{\,\rm K}$ (e.g., Furlanetto Reference Furlanetto2006; McQuinn & O’Leary Reference McQuinn and O’Leary2012). There is considerable uncertainty in these latter stages, which depend upon poorly known properties of the galaxies and the cosmic star formation history.

Many authors have put forward possible sources of more exotic heating, including annihilating DM (e.g., Furlanetto et al. Reference Furlanetto, Oh and Pierpaoli2006; Valdés et al. Reference Valdés, Evoli, Mesinger, Ferrara and Yoshida2013), evaporating primordial black holes (PBHs) (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Dutta, Gao, Strigari and Watson2017; Mack & Wesley Reference Mack and Wesley2008), cosmic string wakes (Brandenberger et al. Reference Brandenberger, Danos, Hernández and Holder2010), and many more. In many cases, these might be distinguished from X-ray heating by (a) occurring before significant galaxy formation has occurred or (b) by depositing energy more uniformly than would be expected from galaxy clustering. Incorporation of DM annihilation models into simulations of the 21-cm signal suggests that plausible DM candidates might be ruled out by future 21-cm observations (Valdés et al. Reference Valdés, Evoli, Mesinger, Ferrara and Yoshida2013). Ultimately, the physics of how DM annihilation produces and deposits energy as heating or ionisation is complex and requires consideration of the decay products and their propagation from the decay site into the IGM (Schön et al. Reference Schön, Mack, Avram, Wyithe and Barberio2015).

Note that DM candidates may modify the thermal history through their effect on the distribution of galaxies too, as discussed in the next section.

2.3.3. Warm DM effects

WDM is an important alternative to the standard cold dark matter (CDM) candidate. Although there have been a series of studies on the constraints on the mass of the WDM, a large parameter space is still unexplored and is possible in principle. These existing constraints include the lower limit on the mass of a thermal WDM particle (![]() $m_{X}\geq 2.3\, \rm{keV}$) from Milky Way satellites (Polisensky & Ricotti Reference Polisensky and Ricotti2011) and from Lyman-

$m_{X}\geq 2.3\, \rm{keV}$) from Milky Way satellites (Polisensky & Ricotti Reference Polisensky and Ricotti2011) and from Lyman-![]() $\alpha$ forest data (Narayanan et al. Reference Narayanan, Spergel, Davé and Ma2000; Viel Reference Viel, Williams, Shu and Menard2005; Viel et al. Reference Viel, Becker, Bolton, Haehnelt, Rauch and Sargent2008).

$\alpha$ forest data (Narayanan et al. Reference Narayanan, Spergel, Davé and Ma2000; Viel Reference Viel, Williams, Shu and Menard2005; Viel et al. Reference Viel, Becker, Bolton, Haehnelt, Rauch and Sargent2008).

A possible effect of WDM during the reionisation and cosmic dawn epochs is distinguishable from both the mean brightness temperature and the power spectra. The key processes that are altered in the WDM model are the Wouthysen–Field coupling, the X-ray heating, and the reionisation effects described in Section 2.2.1. This is because the WDM can delay the first object formation, so the absorption features in the ![]() $\delta T_{b}$ evolution could be strongly delayed or suppressed. In addition, the X-ray heating process, which relies on the X-rays from the first generation of sources, as well as the Lyman-

$\delta T_{b}$ evolution could be strongly delayed or suppressed. In addition, the X-ray heating process, which relies on the X-rays from the first generation of sources, as well as the Lyman-![]() $\alpha$ emissivity, can be also affected due to the delayed first objects (see also Figure 7 of Pritchard & Loeb Reference Pritchard and Loeb2012). Of course, the magnitude of the effects depends on the scale of interest. Finally, reionisation is also affected because the WDM can delay the reionisation process, and therefore affect the ionisation fraction of the Universe at redshift

$\alpha$ emissivity, can be also affected due to the delayed first objects (see also Figure 7 of Pritchard & Loeb Reference Pritchard and Loeb2012). Of course, the magnitude of the effects depends on the scale of interest. Finally, reionisation is also affected because the WDM can delay the reionisation process, and therefore affect the ionisation fraction of the Universe at redshift ![]() $\sim\!10$ (Figures 8 and 9 of Barkana et al. Reference Barkana, Haiman and Ostriker2001).

$\sim\!10$ (Figures 8 and 9 of Barkana et al. Reference Barkana, Haiman and Ostriker2001).

Examples of the effects of WDM models on the spin temperature of the gas will be discussed in Section 5.2.3. For the case of WDM, the spin temperature, ![]() $T_{\rm S}$, stays near the CMB temperature,

$T_{\rm S}$, stays near the CMB temperature, ![]() $T_{\gamma}$, at redshift

$T_{\gamma}$, at redshift ![]() $z>100$. The absorption trough occurs due to the fact that at a later stage, the X-ray heating rate surpasses the adiabatic cooling. Initially, the mean collapse fraction in WDM models is lower than in CDM models, but it grows more rapidly in the heating of gas.

$z>100$. The absorption trough occurs due to the fact that at a later stage, the X-ray heating rate surpasses the adiabatic cooling. Initially, the mean collapse fraction in WDM models is lower than in CDM models, but it grows more rapidly in the heating of gas.

The mean brightness temperature as a function of redshift (frequency) for such WDM models with ![]() $m_{\text{X}}=2,\,3,\,4\,\text{keV}$, respectively, is explored by Sitwell et al. (Reference Sitwell, Mesinger, Ma and Sigurdson2014) and elaborated on in Section 5.2.3. It is shown that if the WDM mass is below the limit

$m_{\text{X}}=2,\,3,\,4\,\text{keV}$, respectively, is explored by Sitwell et al. (Reference Sitwell, Mesinger, Ma and Sigurdson2014) and elaborated on in Section 5.2.3. It is shown that if the WDM mass is below the limit ![]() $m_{\text{X}}<10\,\text{keV}$, it can substantially change the mean evolution of

$m_{\text{X}}<10\,\text{keV}$, it can substantially change the mean evolution of ![]() $\overline{T}_{\rm b}(z)$.

$\overline{T}_{\rm b}(z)$.

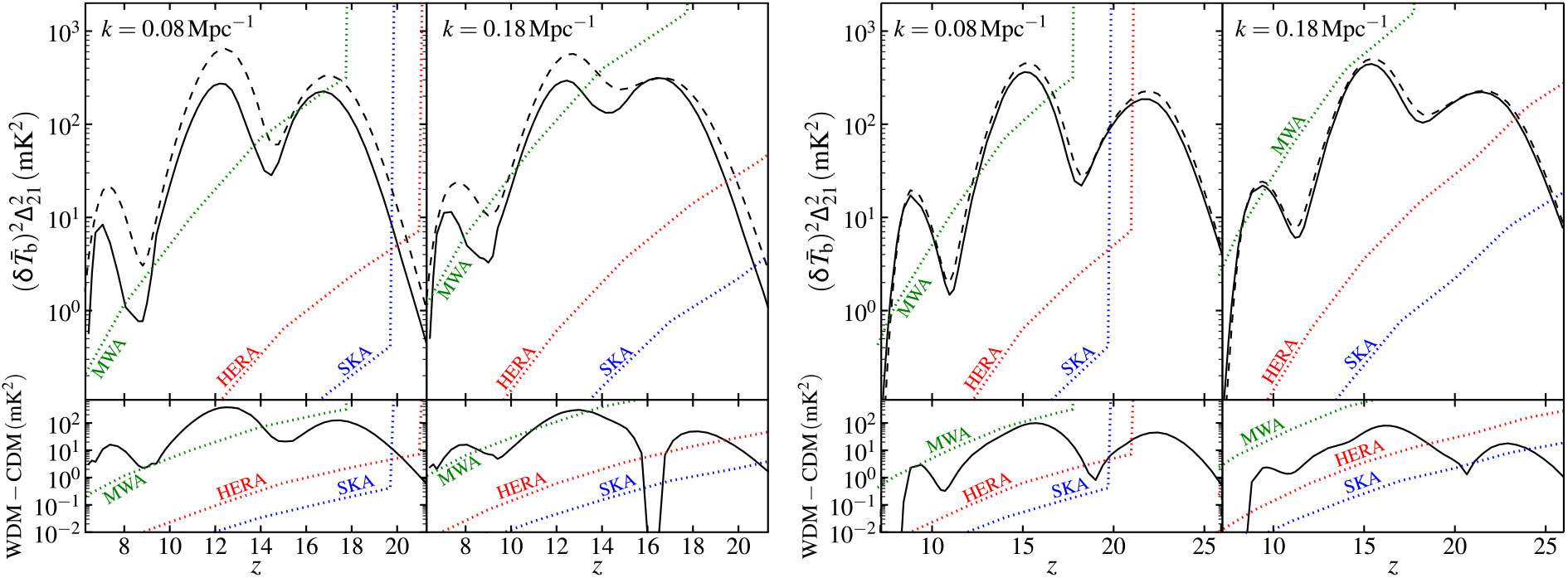

In addition to the mean temperature evolution, Sitwell et al. (Reference Sitwell, Mesinger, Ma and Sigurdson2014) also explored the power spectrum of WDM models, and showed a three-peak structure in ![]() $k=0.08

$ and

$k=0.08

$ and ![]() $k=0.18 \, \text{Mpc}^{-1}$ modes, which are associated with inhomogeneities in the Wouthuysen–Field coupling coefficient

$k=0.18 \, \text{Mpc}^{-1}$ modes, which are associated with inhomogeneities in the Wouthuysen–Field coupling coefficient ![]() $x_{\alpha}$, the kinetic temperature

$x_{\alpha}$, the kinetic temperature ![]() $T_{\rm K}$, and the ionisation fraction

$T_{\rm K}$, and the ionisation fraction ![]() $x_{\text{HI}}$, from high to low redshifts. As discussed in detail in Section 5.2.3, the power at these specific modes can be boosted, depending upon the mass of the WDM particle.

$x_{\text{HI}}$, from high to low redshifts. As discussed in detail in Section 5.2.3, the power at these specific modes can be boosted, depending upon the mass of the WDM particle.

These variations in the mean temperature and fluctuations can be measured and tested using current interferometric radio telescopes. Mesinger et al. (Reference Mesinger, Ewall-Wice and Hewitt2014) and Sitwell et al. (Reference Sitwell, Mesinger, Ma and Sigurdson2014) showed forecasts for the 1-![]() $\sigma$ thermal noise levels for 2 000 h of observation time for the MWAFootnote d, the HERAFootnote e, and for SKA1-Low. On the other hand, there are major uncertainties in the evolution of high-redshift star formation (in low-mass halos in particular), with a potentially complex history due to various astrophysical feedback mechanisms [including photo-heating, Lyman–Werner radiation (photons capable of dissociating molecular hydrogen), and supernova feedback; the latter includes hydrodynamic and radiative feedback as well as metal enrichment]. The estimates do indicate that next-generation radio observations may be able to test the excess power in the power spectra of brightness temperature for

$\sigma$ thermal noise levels for 2 000 h of observation time for the MWAFootnote d, the HERAFootnote e, and for SKA1-Low. On the other hand, there are major uncertainties in the evolution of high-redshift star formation (in low-mass halos in particular), with a potentially complex history due to various astrophysical feedback mechanisms [including photo-heating, Lyman–Werner radiation (photons capable of dissociating molecular hydrogen), and supernova feedback; the latter includes hydrodynamic and radiative feedback as well as metal enrichment]. The estimates do indicate that next-generation radio observations may be able to test the excess power in the power spectra of brightness temperature for ![]() $m_{\text{X}}<10 \, \text{keV}$ models over a wide range of redshifts. The SKA, in particular, will provide a unique prospect of measuring the mean brightness temperature and the 21-cm power spectrum out to

$m_{\text{X}}<10 \, \text{keV}$ models over a wide range of redshifts. The SKA, in particular, will provide a unique prospect of measuring the mean brightness temperature and the 21-cm power spectrum out to ![]() $z\simeq 20$. However, distinguishing WDM from CDM will require a clear separation from possible astrophysical effects.

$z\simeq 20$. However, distinguishing WDM from CDM will require a clear separation from possible astrophysical effects.

2.3.4. Measuring the fine structure constant with the SKA using the 21-cm line

The standard model of particle physics fails to explain the values of some fundamental ‘constants’, like the mass ratio of the electron to the proton, the fine structure constant, etc. (see e.g., Uzan Reference Uzan2011). Dirac (Reference Dirac1937) hypothesised that these constants might change in space as well as in time. Studies using the optical spectra of distant quasars indicated, controversially, the existence of temporal (e.g., Webb et al. Reference Webb, Murphy, Flambaum, Dzuba, Barrow, Churchill, Prochaska and Wolfe2001) and spatial (e.g., Webb et al. Reference Webb, King, Murphy, Flambaum, Carswell and Bainbridge2011) variations in the fine structure constant, ![]() $\alpha$ (but see also Srianand et al. (Reference Srianand, Chand, Petitjean and Aracil2004) and the more recent results of Murphy et al. (Reference Murphy, Malec and Prochaska2016) suggesting no significant cosmological variations. However, these results may be in tension with terrestrial experiments using optical atomic clocks, which set a very stringent limit on the temporal variation of

$\alpha$ (but see also Srianand et al. (Reference Srianand, Chand, Petitjean and Aracil2004) and the more recent results of Murphy et al. (Reference Murphy, Malec and Prochaska2016) suggesting no significant cosmological variations. However, these results may be in tension with terrestrial experiments using optical atomic clocks, which set a very stringent limit on the temporal variation of ![]() $\alpha$ (Rosenband et al. Reference Rosenband2008). Investigation along these lines has great significance to our understanding of gravitation through the underlying equivalence principle (Shao & Wex 2016), as well as fundamental (scalar) fields and cosmology (Damour et al. Reference Damour, Piazza and Veneziano2002). It could also provide an intriguing clue to the outstanding ‘cosmological constant problem’ (Parkinson et al. Reference Parkinson, Bassett and Barrow2004).

$\alpha$ (Rosenband et al. Reference Rosenband2008). Investigation along these lines has great significance to our understanding of gravitation through the underlying equivalence principle (Shao & Wex 2016), as well as fundamental (scalar) fields and cosmology (Damour et al. Reference Damour, Piazza and Veneziano2002). It could also provide an intriguing clue to the outstanding ‘cosmological constant problem’ (Parkinson et al. Reference Parkinson, Bassett and Barrow2004).

In the case that ![]() $\alpha$ varies as a function of time (e.g., as a cosmologically evolving scalar field), the evolution could be non-monotonic in general. Therefore, it would be greatly beneficial if we could measure

$\alpha$ varies as a function of time (e.g., as a cosmologically evolving scalar field), the evolution could be non-monotonic in general. Therefore, it would be greatly beneficial if we could measure ![]() $\alpha$ at various redshifts. The quasar spectra and optical atomic clocks mentioned previously only probe

$\alpha$ at various redshifts. The quasar spectra and optical atomic clocks mentioned previously only probe ![]() $\alpha$ at moderate redshifts,

$\alpha$ at moderate redshifts, ![]() $0.5 \lesssim z \lesssim 3.5$ and

$0.5 \lesssim z \lesssim 3.5$ and ![]() $z \simeq 0$, respectively. Hence, reionisation and cosmic dawn provide an interesting avenue to probe the possibility of a varying

$z \simeq 0$, respectively. Hence, reionisation and cosmic dawn provide an interesting avenue to probe the possibility of a varying ![]() $\alpha$ at large z. Because of its high resolution in radio spectral lines, SKA1-Low has good prospects to use them (e.g., lines from Hi and the OH radical) to determine

$\alpha$ at large z. Because of its high resolution in radio spectral lines, SKA1-Low has good prospects to use them (e.g., lines from Hi and the OH radical) to determine ![]() $\alpha$ (Curran Reference Curran, Lobanov, Zensus, Cesarsky and Diamond2007; SKA Science Working Group 2011). The covered redshifts for SKA1-Low will be, for example,

$\alpha$ (Curran Reference Curran, Lobanov, Zensus, Cesarsky and Diamond2007; SKA Science Working Group 2011). The covered redshifts for SKA1-Low will be, for example, ![]() $z

\lesssim 13$ for the Hi 21-cm absorption and

$z

\lesssim 13$ for the Hi 21-cm absorption and ![]() $z \lesssim 16$ for the ground-state 18 -cm OH absorption (Curran et al. Reference Curran, Kanekar and Darling2004). Khatri & Wandelt (Reference Khatri and Wandelt2007) proposed another method to measure

$z \lesssim 16$ for the ground-state 18 -cm OH absorption (Curran et al. Reference Curran, Kanekar and Darling2004). Khatri & Wandelt (Reference Khatri and Wandelt2007) proposed another method to measure ![]() $\alpha$, through the 21-cm absorption of CMB photons. They found that the 21-cm signal is very sensitive to variations in

$\alpha$, through the 21-cm absorption of CMB photons. They found that the 21-cm signal is very sensitive to variations in ![]() $\alpha$, such that a change of 1% in

$\alpha$, such that a change of 1% in ![]() $\alpha$ modifies the mean brightness temperature decrement of the CMB due to 21-cm absorption by

$\alpha$ modifies the mean brightness temperature decrement of the CMB due to 21-cm absorption by ![]() $\gtrsim5\%$ over the redshift range

$\gtrsim5\%$ over the redshift range ![]() $30 \lesssim z

\lesssim 50$. It also affects, as a characteristic function of the redshift z, the angular power spectrum of fluctuations in the 21-cm absorption; however, the measurement of the angular power spectrum at these redshifts (corresponding to the Dark Ages) would require lower frequency observations than those from the SKA. In summary, constraints on the variation of

$30 \lesssim z

\lesssim 50$. It also affects, as a characteristic function of the redshift z, the angular power spectrum of fluctuations in the 21-cm absorption; however, the measurement of the angular power spectrum at these redshifts (corresponding to the Dark Ages) would require lower frequency observations than those from the SKA. In summary, constraints on the variation of ![]() $\alpha$ at various redshifts will significantly advance our basic understanding of nature and might provide clues to new physics beyond the standard model (Uzan Reference Uzan2011).

$\alpha$ at various redshifts will significantly advance our basic understanding of nature and might provide clues to new physics beyond the standard model (Uzan Reference Uzan2011).

2.3.5. Cosmic shear and the EoR

Important information on the distribution of matter is encoded by weak lensing of the 21-cm signal along the line of sight to the EoR (Pritchard et al. Reference Pritchard2015). Zahn & Zaldarriaga (Reference Zahn and Zaldarriaga2006) and Metcalf & White (Reference Metcalf and White2009) showed that a large area survey at SKA sensitivity might have the potential to determine the lensing convergence power spectrum via the non-gaussianity of 21-cm maps. It remains to be seen over what area SKA-Low surveys might have the sensitivity to measure cosmic shear, but the proposed deep EoR survey over 100 deg![]() $^2$ should be sufficient. This would measure how DM is distributed in a representative patch of sky, something feasible only with galaxy lensing towards unusually large galaxy clusters. This might offer the chance to match luminous matter with overall mass, thereby constraining the DM paradigm.

$^2$ should be sufficient. This would measure how DM is distributed in a representative patch of sky, something feasible only with galaxy lensing towards unusually large galaxy clusters. This might offer the chance to match luminous matter with overall mass, thereby constraining the DM paradigm.

The convergence power spectrum can be estimated using the Fourier space quadratic estimator technique of Hu (Reference Hu2001), originally developed for lensing data on the CMB and expanded to 3D observables, that is, the 21-cm intensity field ![]() $I(\theta,z)$ discussed by Zahn & Zaldarriaga (Reference Zahn and Zaldarriaga2006) and Metcalf & White (Reference Metcalf and White2009).

$I(\theta,z)$ discussed by Zahn & Zaldarriaga (Reference Zahn and Zaldarriaga2006) and Metcalf & White (Reference Metcalf and White2009).

The convergence estimator and the corresponding lensing reconstruction noise are derived under the assumption that there is a gaussian distribution in temperature. This will not completely hold for the EoR, since reionisation introduces considerable non-gaussianity, but acts as a reasonable approximation.

The benefit of 21-cm lensing is that one can combine data from multiple redshift slices. In Fourier space, fluctuations in temperature (brightness) are separated into wave vectors normal to the sightline ![]() $\mathbf{k_\perp}=\mathbf{l}/r$, with r the angular diameter distance to the source redshift, and a discretised parallel wave vector

$\mathbf{k_\perp}=\mathbf{l}/r$, with r the angular diameter distance to the source redshift, and a discretised parallel wave vector ![]() $k_\parallel =

2\pi j/\mathcal{L}$, where

$k_\parallel =

2\pi j/\mathcal{L}$, where ![]() $\mathcal{L}$ is the depth of the volume observed. Considering modes with different values of j to be orthogonal, an optimal estimator results from combining the estimators from separate j modes without any mixing. The reconstruction noise of 3D lensing is then (Zahn & Zaldarriaga Reference Zahn and Zaldarriaga2006):

$\mathcal{L}$ is the depth of the volume observed. Considering modes with different values of j to be orthogonal, an optimal estimator results from combining the estimators from separate j modes without any mixing. The reconstruction noise of 3D lensing is then (Zahn & Zaldarriaga Reference Zahn and Zaldarriaga2006):

$$

\begin{equation}

N(L,\nu) =\left[\sum_{j=1}^{j_{\rm max}}

\frac{1}{L^2}\int \frac{d^2\ell}{(2\pi)^2} \frac{[\mathbf{l} \cdot \mathbf{L}

C_{\ell,j}+\mathbf{L} \cdot (\mathbf{L}-\mathbf{l})

C_{|\ell-L|,j}]^2}{2 C^{\rm tot}_{\ell,j}C^{\rm

tot}_{|\mathbf{l}-\mathbf{L}|,j}}\right]^{-1}.

\label{eqn2}

\end{equation}

$$

$$

\begin{equation}

N(L,\nu) =\left[\sum_{j=1}^{j_{\rm max}}

\frac{1}{L^2}\int \frac{d^2\ell}{(2\pi)^2} \frac{[\mathbf{l} \cdot \mathbf{L}

C_{\ell,j}+\mathbf{L} \cdot (\mathbf{L}-\mathbf{l})

C_{|\ell-L|,j}]^2}{2 C^{\rm tot}_{\ell,j}C^{\rm

tot}_{|\mathbf{l}-\mathbf{L}|,j}}\right]^{-1}.

\label{eqn2}

\end{equation}

$$ Here, ![]() $C^{\rm tot}_{\ell,j}=C_{\ell,j}+C^{\rm N}_\ell$, where

$C^{\rm tot}_{\ell,j}=C_{\ell,j}+C^{\rm N}_\ell$, where ![]() $C_{\ell,j}=[\bar{T}(z)]^2P_{\ell,j}$ with

$C_{\ell,j}=[\bar{T}(z)]^2P_{\ell,j}$ with ![]() $\bar{T}(z)$ the mean observed brightness temperature at redshift z due to the mean density of HI and

$\bar{T}(z)$ the mean observed brightness temperature at redshift z due to the mean density of HI and ![]() $P_{\ell,j}$ is the associated power spectrum of DM (Zahn & Zaldarriaga Reference Zahn and Zaldarriaga2006).

$P_{\ell,j}$ is the associated power spectrum of DM (Zahn & Zaldarriaga Reference Zahn and Zaldarriaga2006).

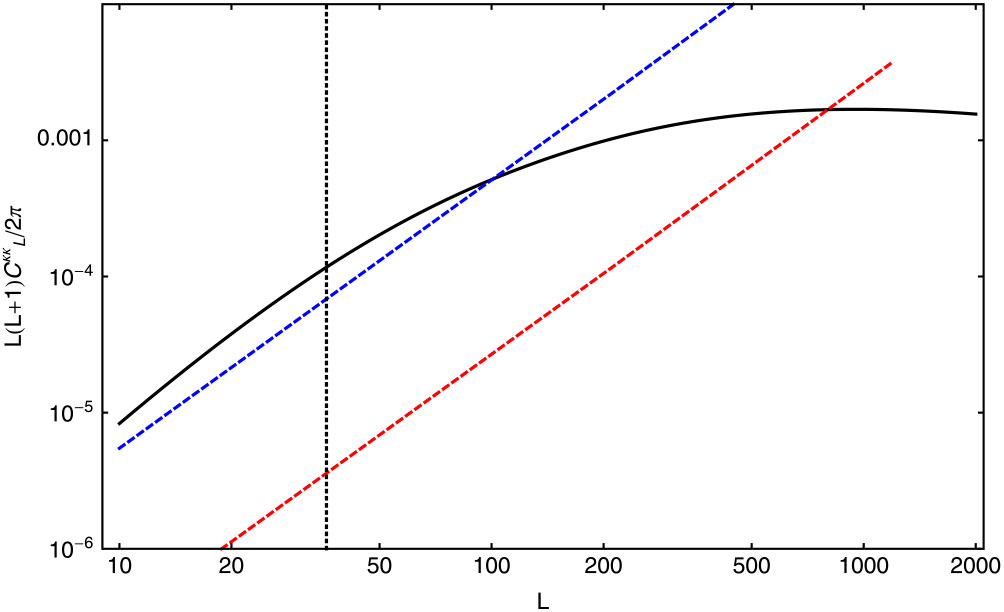

Figure 4 gives a sense of the sensitivity to the convergence power spectrum that might be achieved with SKA-Low after 1 000 h integration on a 20-deg![]() $^2$ field. It should be feasible to measure the signal associated with lensing over a range of angular scales. Increasing the survey area would allow access to large angular scales, where the signal-to-noise is the greatest. This measurement would be significantly improved with the larger sensitivity of SKA2 (Romeo et al. Reference Romeo, Metcalf and Pourtsidou2018). For redshifts after reionisation, the power spectrum of weak lensing should be better measured using SKA-Mid and the 21-cm intensity mapping (IM) approach discussed above, but covering a much wider sky area (Pourtsidou & Metcalf Reference Pourtsidou and Metcalf2014).

$^2$ field. It should be feasible to measure the signal associated with lensing over a range of angular scales. Increasing the survey area would allow access to large angular scales, where the signal-to-noise is the greatest. This measurement would be significantly improved with the larger sensitivity of SKA2 (Romeo et al. Reference Romeo, Metcalf and Pourtsidou2018). For redshifts after reionisation, the power spectrum of weak lensing should be better measured using SKA-Mid and the 21-cm intensity mapping (IM) approach discussed above, but covering a much wider sky area (Pourtsidou & Metcalf Reference Pourtsidou and Metcalf2014).

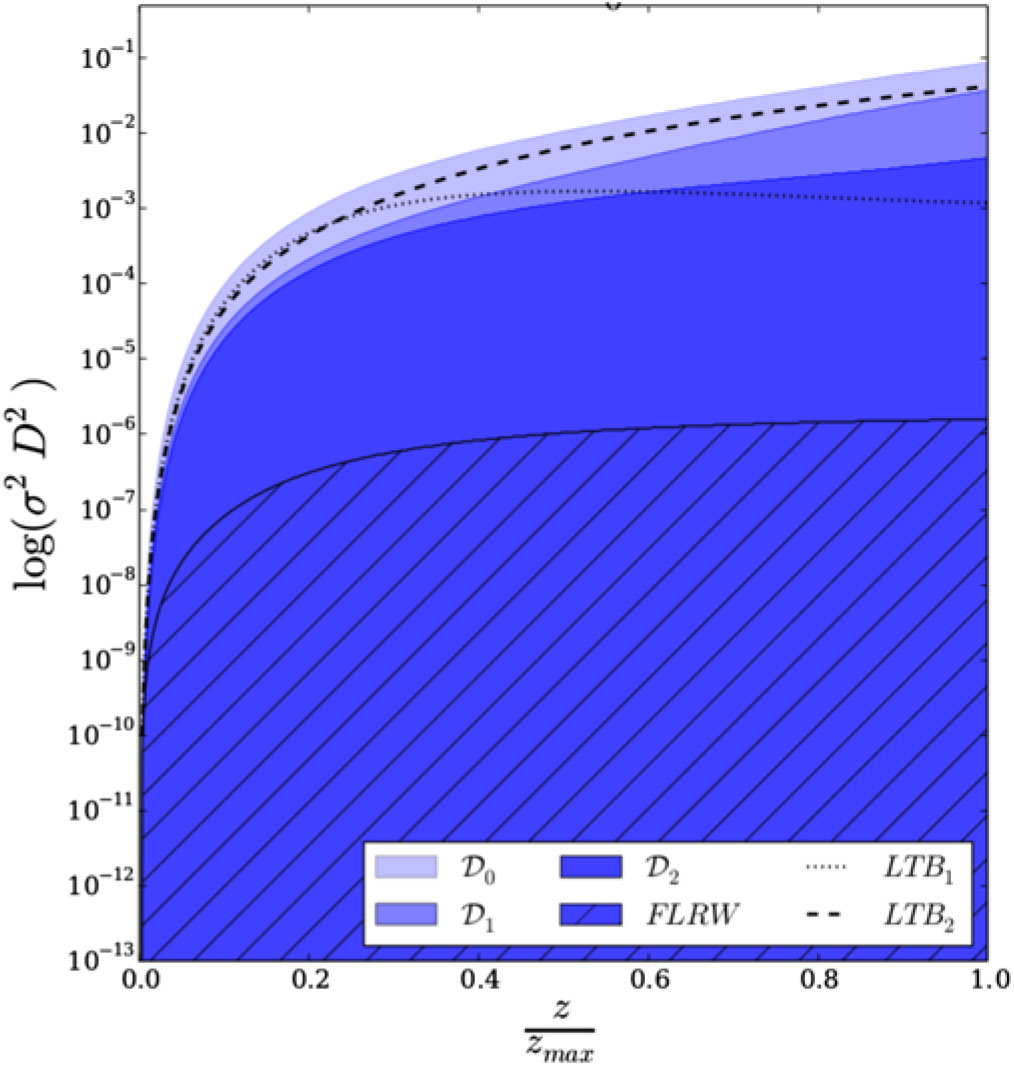

Figure 4. The solid black line shows the power spectrum of the lensing convergence field, ![]() $C^{\kappa \kappa}_L$, for sources at

$C^{\kappa \kappa}_L$, for sources at ![]() $z=8$; dashed lines indicate the noise associated with lensing reconstruction,

$z=8$; dashed lines indicate the noise associated with lensing reconstruction, ![]() $N_L$. The blue dashed line is for SKA1-Low with ten 8-MHz frequency bins around

$N_L$. The blue dashed line is for SKA1-Low with ten 8-MHz frequency bins around ![]() $z=8$, covering redshifts from

$z=8$, covering redshifts from ![]() $z \simeq 6.5$ to

$z \simeq 6.5$ to ![]() $z \simeq 11$. The red dashed line is the same but for SKA2-Low. The vertical line represents an estimate of the lowest possible value of L accessible in a 5-by-5 degree field. Regions where noise curves fall below

$z \simeq 11$. The red dashed line is the same but for SKA2-Low. The vertical line represents an estimate of the lowest possible value of L accessible in a 5-by-5 degree field. Regions where noise curves fall below ![]() $C^{\kappa \kappa}_L$ indicate cases for which the typical fluctuations in the lensing deflection should be recoverable in a map. Figure taken from Pritchard et al. (Reference Pritchard2015).

$C^{\kappa \kappa}_L$ indicate cases for which the typical fluctuations in the lensing deflection should be recoverable in a map. Figure taken from Pritchard et al. (Reference Pritchard2015).

2.3.6. Integrated Sachs–Wolfe effect

In Section 2.2.1, we provided an overview of the 21-cm brightness temperature fluctuation and its dependence on cosmological and astrophysical parameters. While we have thus far focused on high redshifts, it will be possible to use 21-cm measurements from after reionisation in order to obtain constraints on various cosmological models. In this case, the 21-cm emission comes from hydrogen atoms within galaxies. The intensity (or equivalently temperature) fluctuations can be mapped on large scales, without resolving individual galaxies; this measurement is known as 21-cm IM. In this section, we consider using the post-reionisation power spectrum of the temperature brightness measured by the SKA, and the cross-correlation of SKA IM measurements with SKA galaxy number counts, in order to detect the ISW effect. As examples of measurements that can be obtained with this observable, we look at the IM constraining power to test statistical anisotropy and inflationary models.

Raccanelli et al. (Reference Raccanelli, Kovetz, Dai and Kamionkowski2016a) presented a study on using the cross-correlation of 21-cm surveys at high redshifts with galaxy number counts; the formalism and methodology is described in that paper. The use of 21-cm radiation instead of the (standard) CMB can provide a confirmation of the detection of the ISW effect, which will be detected by several instruments at different frequencies at the time, and hence influenced by different systematics.

The ISW effect (Sachs & Wolfe Reference Sachs and Wolfe1967; Crittenden & Turok Reference Crittenden and Turok1996; Nishizawa Reference Nishizawa2014) is a gravitational redshift due to the time evolution of the gravitational potential when photons traverse underdensities and overdensities in their journey from the last scattering surface to the observer. This effect produces temperature fluctuations that are proportional to the derivative of gravitational potentials.

The ISW effect has been detected (Nolta et al. Reference Nolta2004; Pietrobon et al. Reference Pietrobon, Balbi and Marinucci2006; Ho et al. Reference Ho, Hirata, Padmanabhan, Seljak and Bahcall2008; Giannantonio et al. Reference Giannantonio, Scranton, Crittenden, Nichol, Boughn, Myers and Richards2008a; Raccanelli et al. Reference Raccanelli, Bonaldi, Negrello, Matarrese, Tormen and de Zotti2008; Giannantonio et al. Reference Giannantonio, Crittenden, Nichol and Ross2012; Planck Collaboration et al. 2014a; Reference Collaboration2016f) through cross-correlation of CMB maps at GHz frequencies with galaxy surveys. It has also been used to constrain cosmological parameters (Giannantonio et al. Reference Giannantonio, Scranton, Crittenden, Nichol, Boughn, Myers and Richards2008b; Massardi et al. Reference Massardi, Bonaldi, Negrello, Ricciardi, Raccanelli and de Zotti2010; Bertacca et al. Reference Bertacca, Raccanelli, Piattella, Pietrobon, Bartolo, Matarrese and Giannantonio2011; Raccanelli et al. Reference Raccanelli2015).

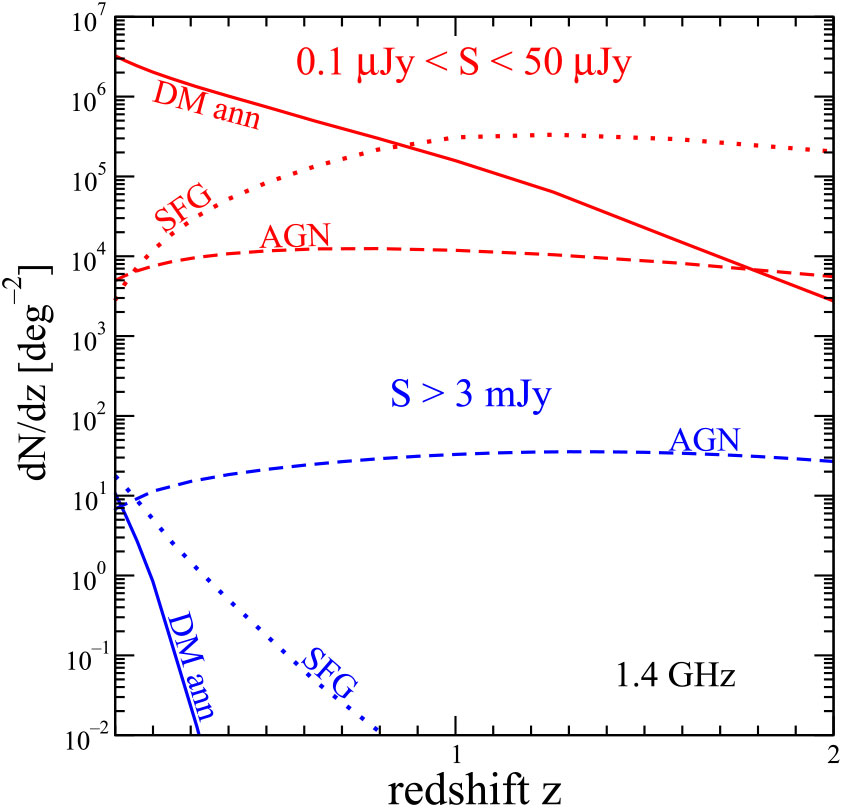

Similar to the CMB, the 21-cm background at high redshifts, described by the brightness temperature fluctuation in Section 2.2.1, will also experience an ISW effect from the evolution of gravitational potential wells (see Figure 5). The dominant signal present is that of unscattered CMB photons, and therefore its late-time ISW signature is highly correlated with the signature at the peak CMB frequencies. A complementary measurement at 21-cm frequencies is promising as it represents an independent detection of the ISW effect, measured with different instruments and contaminated by different foregrounds. As the 21-cm background is set to be observed across a vast redshift range by upcoming experiments, there should be ample signal-to-noise for this detection. The ISW effect on those CMB photons that do interact with the neutral hydrogen clouds at high redshifts provide a source of observable signal. Assuming the CMB fluctuations can be efficiently subtracted from the 21-cm maps, this signal can potentially be detected in the data as well.

Figure 5. Illustration: Radiative transfer of CMB photons through neutral hydrogen gas clouds induces fluctuations at 21-cm frequencies (due to absorption or emission, depending on the relative temperatures of the IGM and the CMB). The majority of the signal is comprised of unscattered CMB photons at the Rayleigh-Jeans tail of its BB spectrum. These photons later undergo line-of-sight blue- or red-shifting as they travel through the evolving gravitational potential wells. Figure taken from Raccanelli et al. (Reference Raccanelli, Kovetz, Dai and Kamionkowski2016a).

To detect the ISW effect, one would cross-correlate the brightness temperature maps with galaxy catalogues. In the case when the photons are unscattered, the detection is more difficult to obtain. The detection depends on a series of parameters of the 21-cm detecting instrument, such as the observing time, the frequency bandwidth, the fractional area coverage, and the length of the baseline. The results weakly depend on the details of the galaxy survey used. Different surveys give slightly different results, but do not lead to a dramatic change in the overall signal-to-noise ratio. Targeting specific redshift ranges and objects could help. The main advantage for detecting the ISW effect is due to the large area of the sky covered. If we assume the standard general relativity (GR) and ![]() $\Lambda$ cold dark matter (

$\Lambda$ cold dark matter (![]() $\Lambda$CDM) cosmology, the ISW effect is mostly important during the late-time accelerated phase, so low-redshift galaxies are to be targeted. The use of a tomographic analysis in the galaxy catalogue and the combination of different surveys (see e.g., Giannantonio et al. Reference Giannantonio, Scranton, Crittenden, Nichol, Boughn, Myers and Richards2008a; Bertacca et al. Reference Bertacca, Raccanelli, Piattella, Pietrobon, Bartolo, Matarrese and Giannantonio2011) can improve the detection of the signal in the case of the LSS-CMB correlation.

$\Lambda$CDM) cosmology, the ISW effect is mostly important during the late-time accelerated phase, so low-redshift galaxies are to be targeted. The use of a tomographic analysis in the galaxy catalogue and the combination of different surveys (see e.g., Giannantonio et al. Reference Giannantonio, Scranton, Crittenden, Nichol, Boughn, Myers and Richards2008a; Bertacca et al. Reference Bertacca, Raccanelli, Piattella, Pietrobon, Bartolo, Matarrese and Giannantonio2011) can improve the detection of the signal in the case of the LSS-CMB correlation.

2.3.7. Statistical anisotropy

Most inflationary models predict the primordial cosmological perturbations to be statistically homogeneous and isotropic. CMB observations, however, indicate a possible departure from statistical isotropy in the form of a dipolar power modulation at large angular scales. A 3![]() $\sigma$ detection of the dipolar power asymmetry, that is, a different power spectrum in two opposite poles of the sky, was reported based on analysis of the off-diagonal components of Please provide the expansion for “WMAP” if necessary. angular correlations of CMB anisotropies with Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe and Planck data on large scales (Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Banday and Gorski2004; Gordon et al. Reference Gordon, Hu, Huterer and Crawford2005; Eriksen et al. Reference Eriksen, Banday, Gorski, Hansen and Lilje2007; Gordon Reference Gordon2007; Planck Collaboration et al. Reference Collaboration2014b; Akrami et al. Reference Akrami, Fantaye, Shafieloo, Eriksen and Hansen2014; Planck Collaboration et al. Reference Collaboration2016e; Planck Collaboration et al. Reference Collaboration2016e,c; Aiola et al. Reference Aiola, Wang, Kosowsky, Kahniashvili and Firouzjahi2015). The distribution of quasars at later times was, however, studied by Hirata (Reference Hirata2009), and showed an agreement with statistical isotropy on much smaller angular scales.

$\sigma$ detection of the dipolar power asymmetry, that is, a different power spectrum in two opposite poles of the sky, was reported based on analysis of the off-diagonal components of Please provide the expansion for “WMAP” if necessary. angular correlations of CMB anisotropies with Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe and Planck data on large scales (Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Banday and Gorski2004; Gordon et al. Reference Gordon, Hu, Huterer and Crawford2005; Eriksen et al. Reference Eriksen, Banday, Gorski, Hansen and Lilje2007; Gordon Reference Gordon2007; Planck Collaboration et al. Reference Collaboration2014b; Akrami et al. Reference Akrami, Fantaye, Shafieloo, Eriksen and Hansen2014; Planck Collaboration et al. Reference Collaboration2016e; Planck Collaboration et al. Reference Collaboration2016e,c; Aiola et al. Reference Aiola, Wang, Kosowsky, Kahniashvili and Firouzjahi2015). The distribution of quasars at later times was, however, studied by Hirata (Reference Hirata2009), and showed an agreement with statistical isotropy on much smaller angular scales.

A significant detection of deviation from statistical isotropy or homogeneity would be inconsistent with some of the simplest models of inflation, making it necessary to postulate new physics, such as non-scalar degrees of freedom. It would, moreover, open a window into the physics of the early Universe, thus shedding light upon the primordial degrees of freedom responsible for inflation.

The off-diagonal components of the angular power spectrum of the 21-cm intensity fluctuations can be used to test this power asymmetry, as discussed in detail by Shiraishi et al. (Reference Shiraishi, Muñoz, Kamionkowski and Raccanelli2016). One can also constrain the rotational invariance of the Universe using the power spectrum of 21-cm fluctuations at the end of the Dark Ages. The potential ability to access small angular scales gives one the opportunity to distinguish the dipolar asymmetry generated by a variable spectral index, below the intermediate scales at which this vanishes. One can compute the angular power spectrum of 21-cm fluctuations sourced by the dipolar and quadrupolar asymmetries, including several non-trivial scale dependencies motivated by theories and observations. By the simple application of an estimator for CMB rotational asymmetry (Pullen & Kamionkowski Reference Pullen and Kamionkowski2007; Hanson & Lewis Reference Hanson and Lewis2009), we can forecast how well 21-cm surveys can constrain departures from rotational invariance. Results for dipolar and quadrupolar asymmetries, for different models and surveys, are discussed by Shiraishi et al. (Reference Shiraishi, Muñoz, Kamionkowski and Raccanelli2016), who show that the planned SKA may not reach the same precision as future CMB experiments in this regard; however, an enhanced SKA instrument could provide the best measurements of statistical anisotropy, for both the dipolar and quadrupolar asymmetry.

The SKA could, though, provide some constraining power for asymmetry parameters since 21-cm measurements have different systematics and come from an entirely different observable compared to the CMB. Moreover, 21-cm surveys provide an independent probe of broken rotational invariance, and as such, would help in disentangling potential biases present in previous CMB experiments.

2.3.8. Tests of inflation

Measurements of IM from SKA can be used to constrain inflationary models via limits on the matter power spectrum, in particular the spectral index and its ‘running’.

Single-field slow-roll inflation models predict a nearly scale-invariant power spectrum of perturbations, as observed at the scales accessible to current cosmological experiments. This spectrum is slightly red, showing a non-zero tilt. A direct consequence of this tilt are non-vanishing runnings of the spectral indices, ![]() $\alpha_s=\mathrm d n_s/\mathrm

d\log k$, and

$\alpha_s=\mathrm d n_s/\mathrm

d\log k$, and ![]() $\beta_s=\mathrm d\alpha_s/\mathrm d\log k$, which in the minimal inflationary scenario should reach absolute values of

$\beta_s=\mathrm d\alpha_s/\mathrm d\log k$, which in the minimal inflationary scenario should reach absolute values of ![]() $10^{-3}$ and

$10^{-3}$ and ![]() $10^{-5}$, respectively. This is of particular importance for PBH production in the early Universe, where a significant increase in power is required at the scale corresponding to the PBH mass, which is of order

$10^{-5}$, respectively. This is of particular importance for PBH production in the early Universe, where a significant increase in power is required at the scale corresponding to the PBH mass, which is of order ![]() $k \sim 10^5$ Mpc–1 for solar mass PBHs (Green & Liddle Reference Green and Liddle1999; Carr Reference Carr2005). It has been argued that a value of the second running

$k \sim 10^5$ Mpc–1 for solar mass PBHs (Green & Liddle Reference Green and Liddle1999; Carr Reference Carr2005). It has been argued that a value of the second running ![]() $\beta_s = 0.03$, within 1

$\beta_s = 0.03$, within 1![]() $\sigma$ of the Planck results, can generate fluctuations leading to the formation of

$\sigma$ of the Planck results, can generate fluctuations leading to the formation of ![]() $30\, {\rm M}_{\odot}$ PBHs if extrapolated to the smallest scales (Carr et al. Reference Carr, Kühnel and Sandstad2016).

$30\, {\rm M}_{\odot}$ PBHs if extrapolated to the smallest scales (Carr et al. Reference Carr, Kühnel and Sandstad2016).

The measurements of 21-cm IM can be used to measure these runnings. A fully covered 1-kilometre-baseline interferometer, observing the EoR, will be able to measure the running ![]() $\alpha_s$ with

$\alpha_s$ with ![]() $10^{-3}$ precision, enough to test the inflationary prediction. However, to reach the sensitivity required for a measurement of

$10^{-3}$ precision, enough to test the inflationary prediction. However, to reach the sensitivity required for a measurement of ![]() $\beta_s\sim 10^{-5}$, a Dark Ages interferometer, with a baseline of

$\beta_s\sim 10^{-5}$, a Dark Ages interferometer, with a baseline of ![]() $\sim\! 300$ km, will be required. Detailed analyses of 21-cm IM experiments forecasts for this (including comparisons with CMB and galaxy surveys) measurements have been made recently (Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Kovetz, Raccanelli, Kamionkowski and Silk2017; Pourtsidou et al. Reference Pourtsidou, Bacon and Crittenden2017; Sekiguchi et al. Reference Sekiguchi, Takahashi, Tashiro and Yokoyama2018).

$\sim\! 300$ km, will be required. Detailed analyses of 21-cm IM experiments forecasts for this (including comparisons with CMB and galaxy surveys) measurements have been made recently (Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Kovetz, Raccanelli, Kamionkowski and Silk2017; Pourtsidou et al. Reference Pourtsidou, Bacon and Crittenden2017; Sekiguchi et al. Reference Sekiguchi, Takahashi, Tashiro and Yokoyama2018).

2.3.9. Free-free emission from cosmological reionisation

As we know, the CMB emerges from the thermalisation epoch, at ![]() $z \sim

10^{6}-10^{7}$, with a BB spectrum thanks to the combined effect of Compton scattering and photon emission/absorption processes (double Compton and bremsstrahlung) in the cosmic plasma, which, at early times, are able to re-establish full thermal equilibrium in the presence of arbitrary levels of perturbing processes. Subsequently, the efficiency of the scattering and above radiative processes decreases because of the expansion of the Universe and the consequent combined reduction of particle number densities and temperatures, and it was no longer possible to achieve the thermodynamical equilibrium.

$z \sim

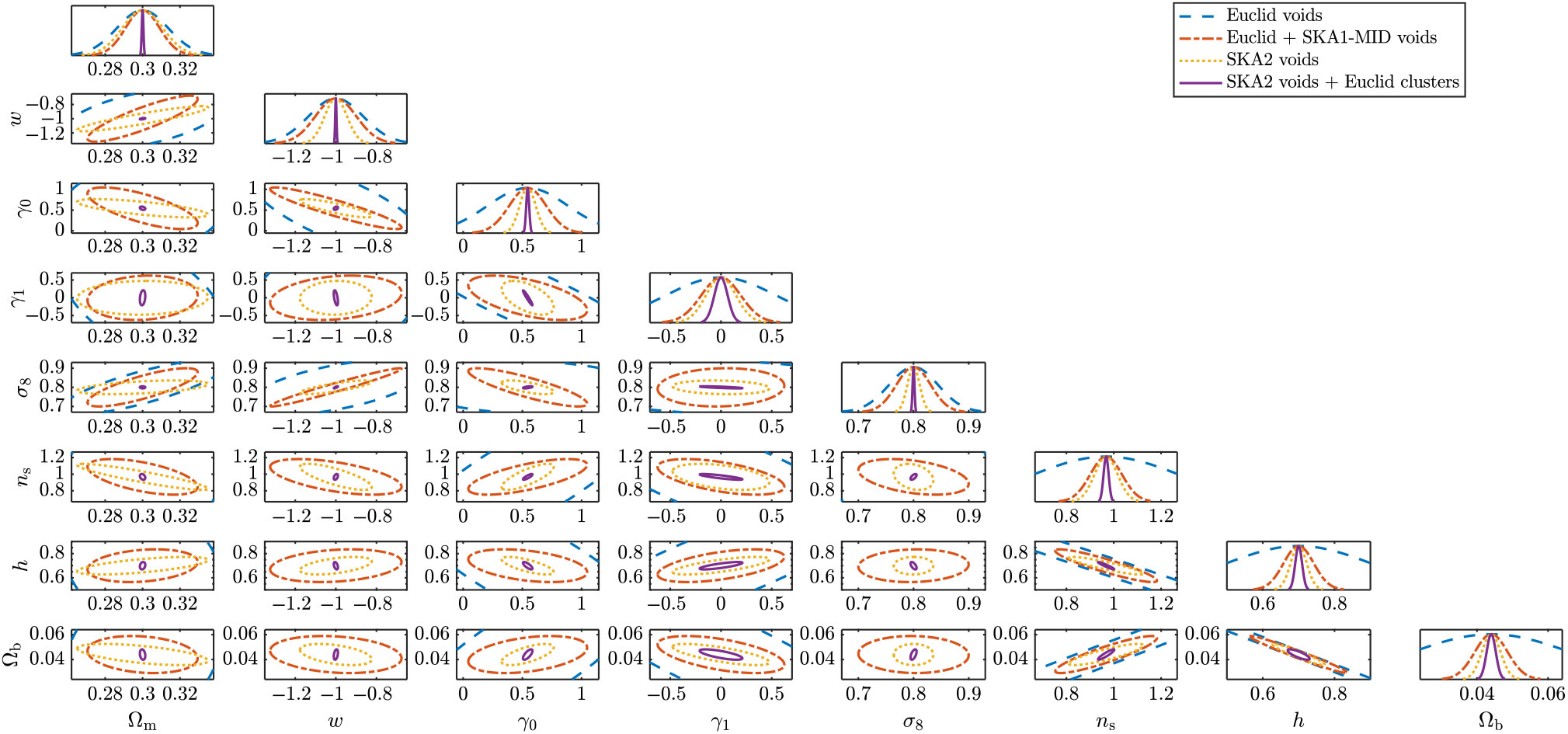

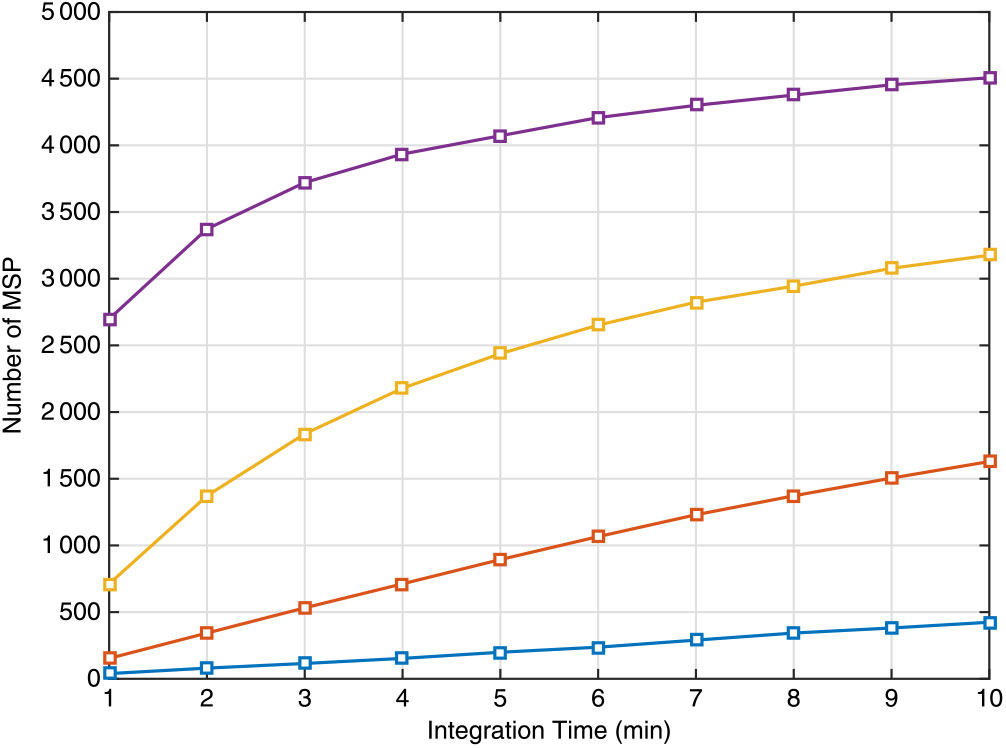

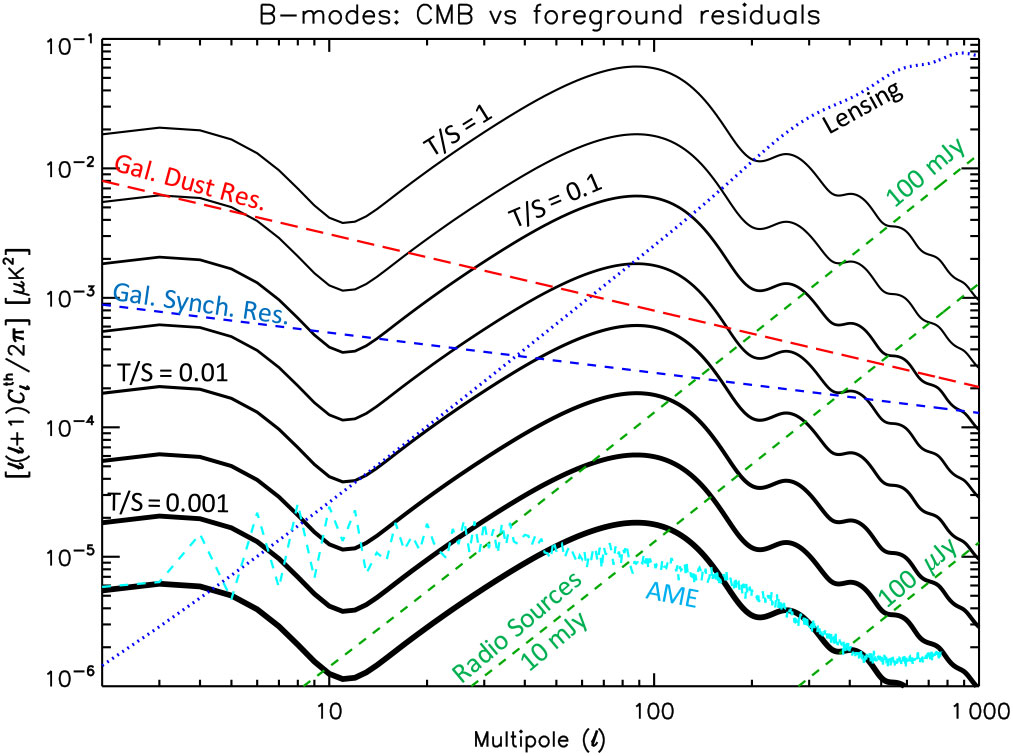

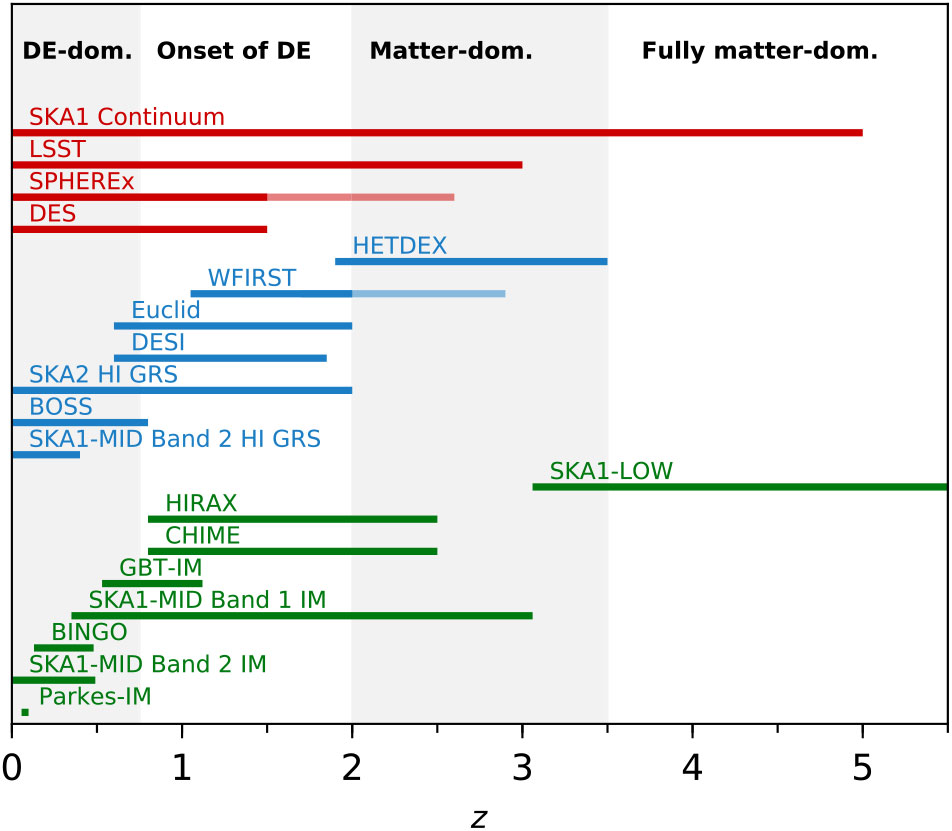

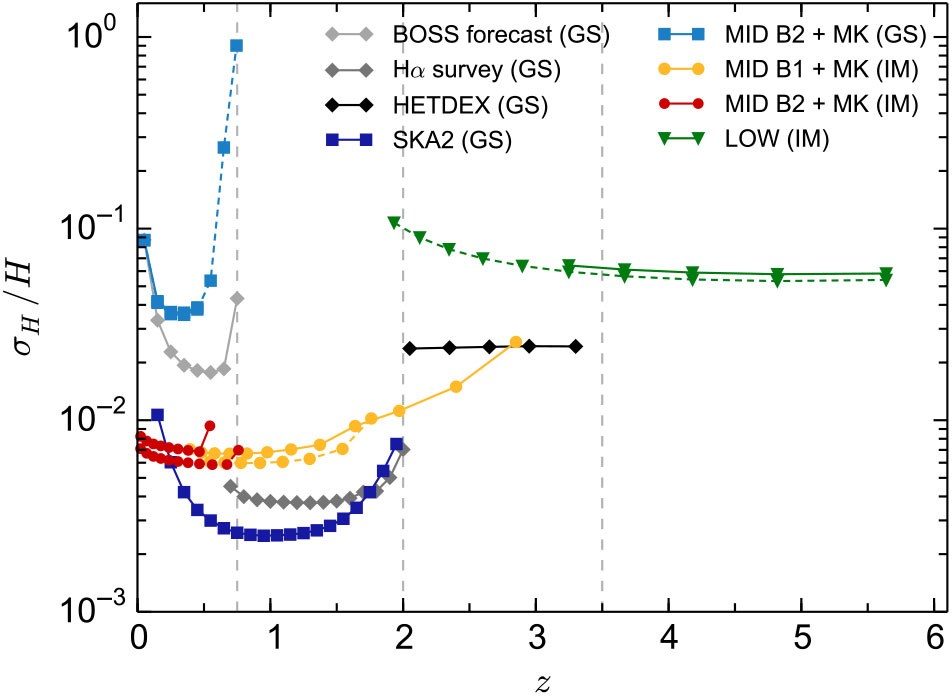

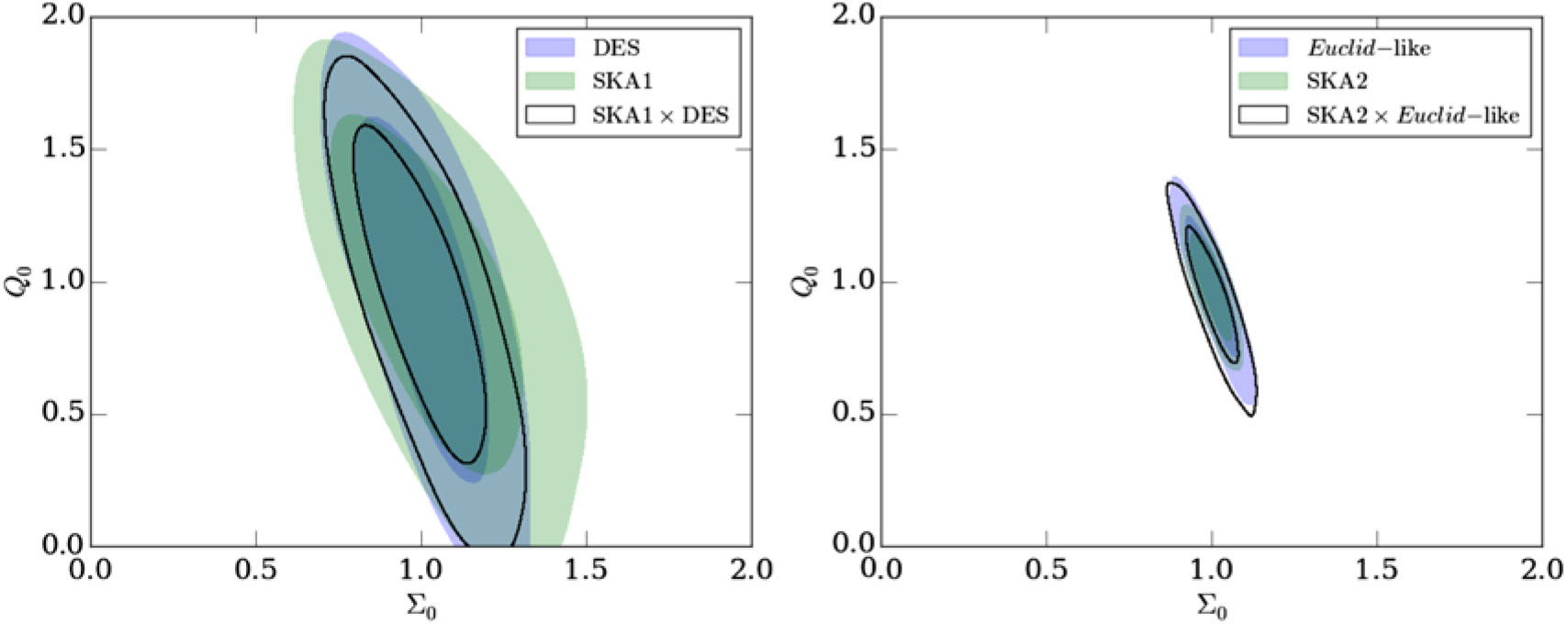

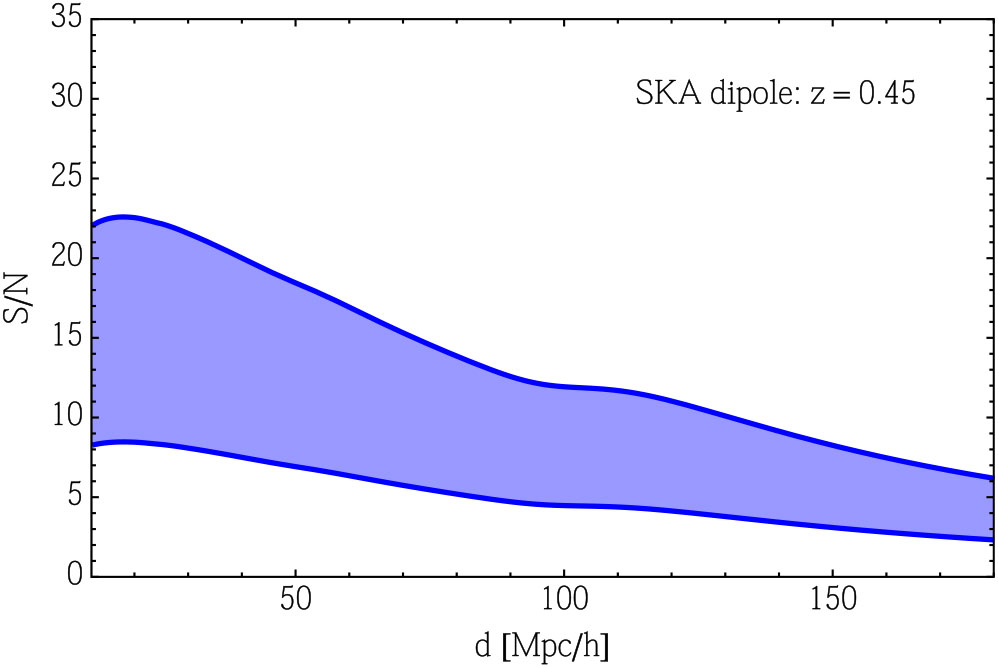

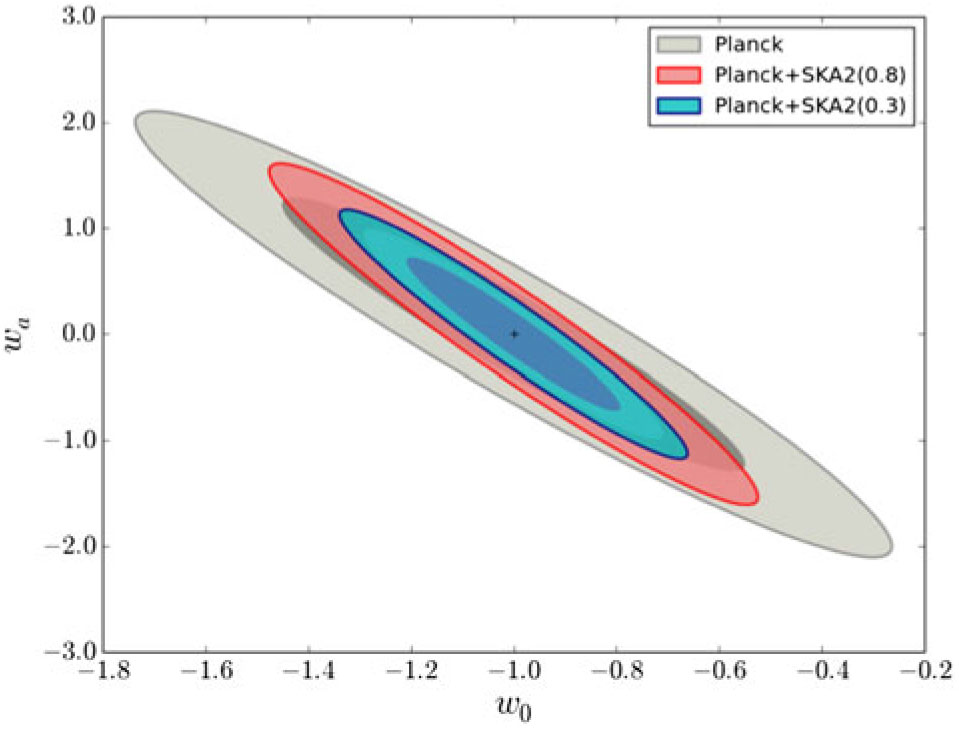

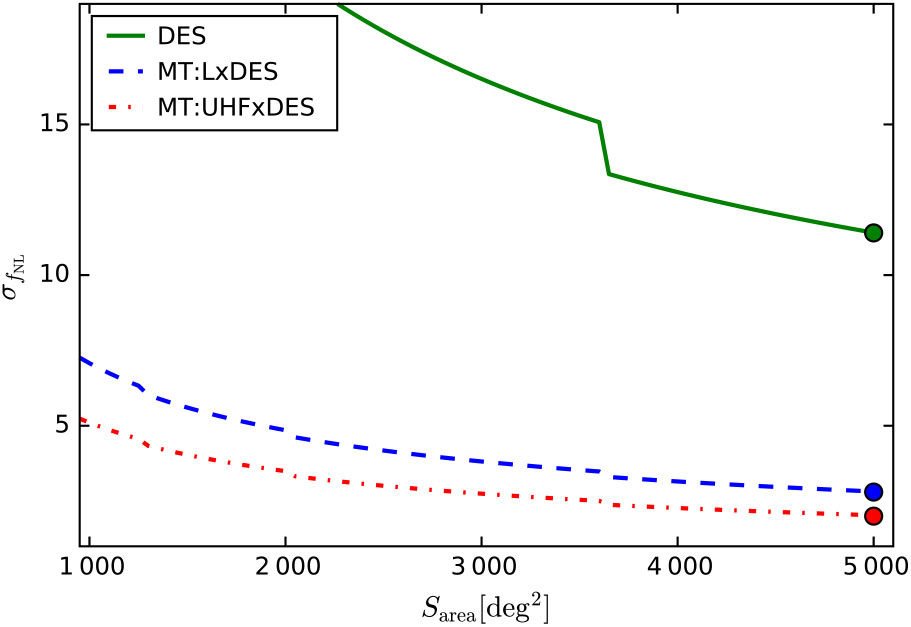

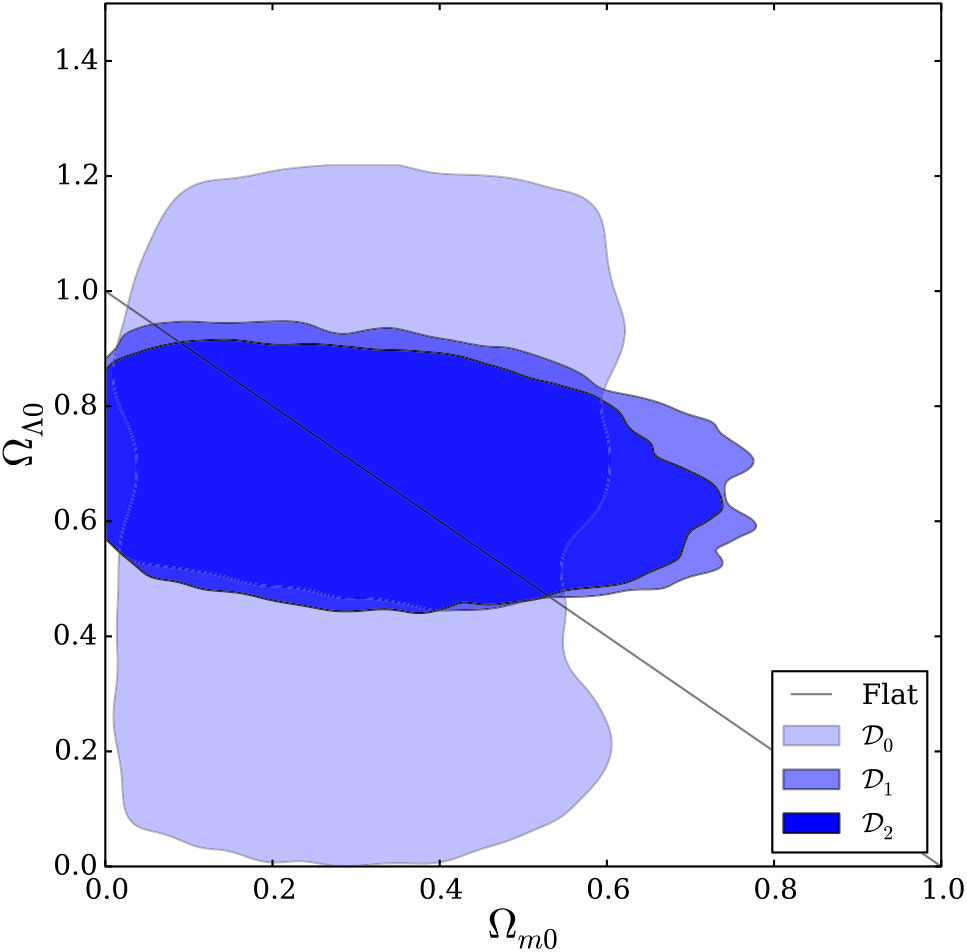

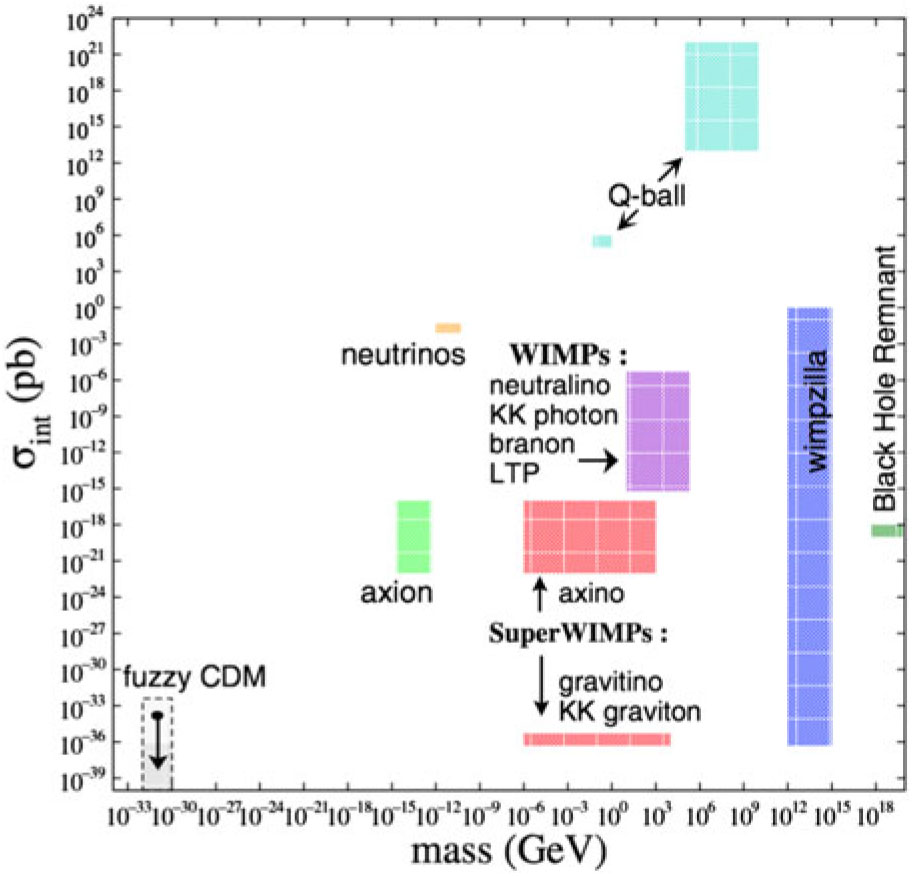

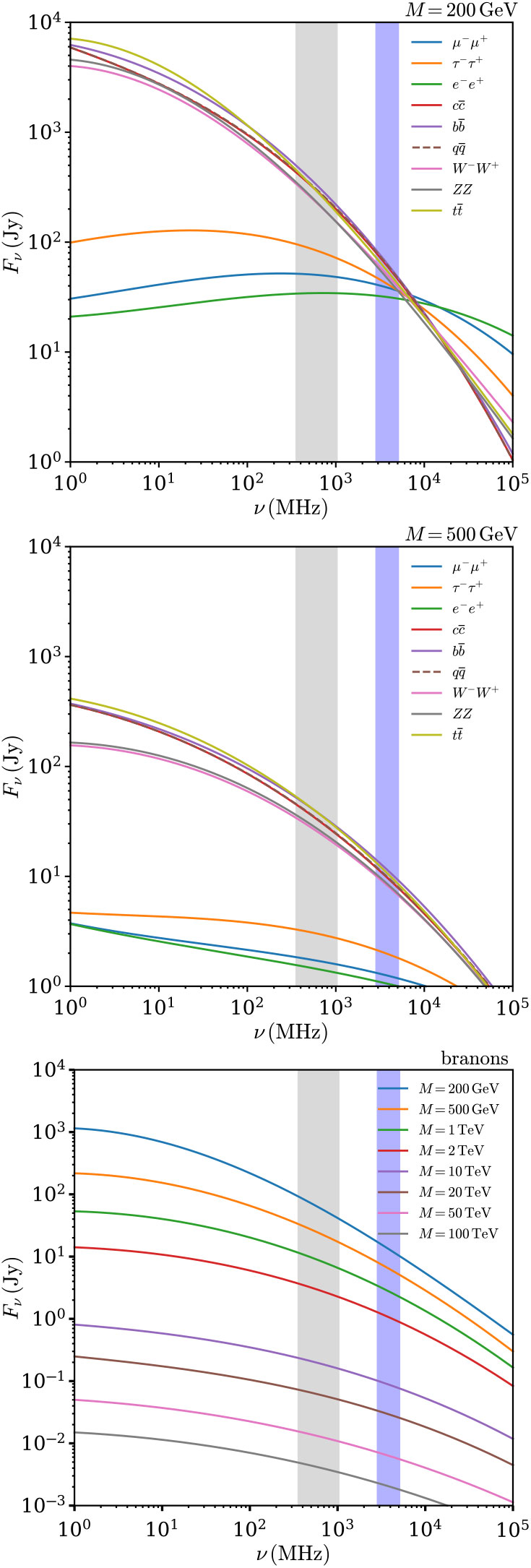

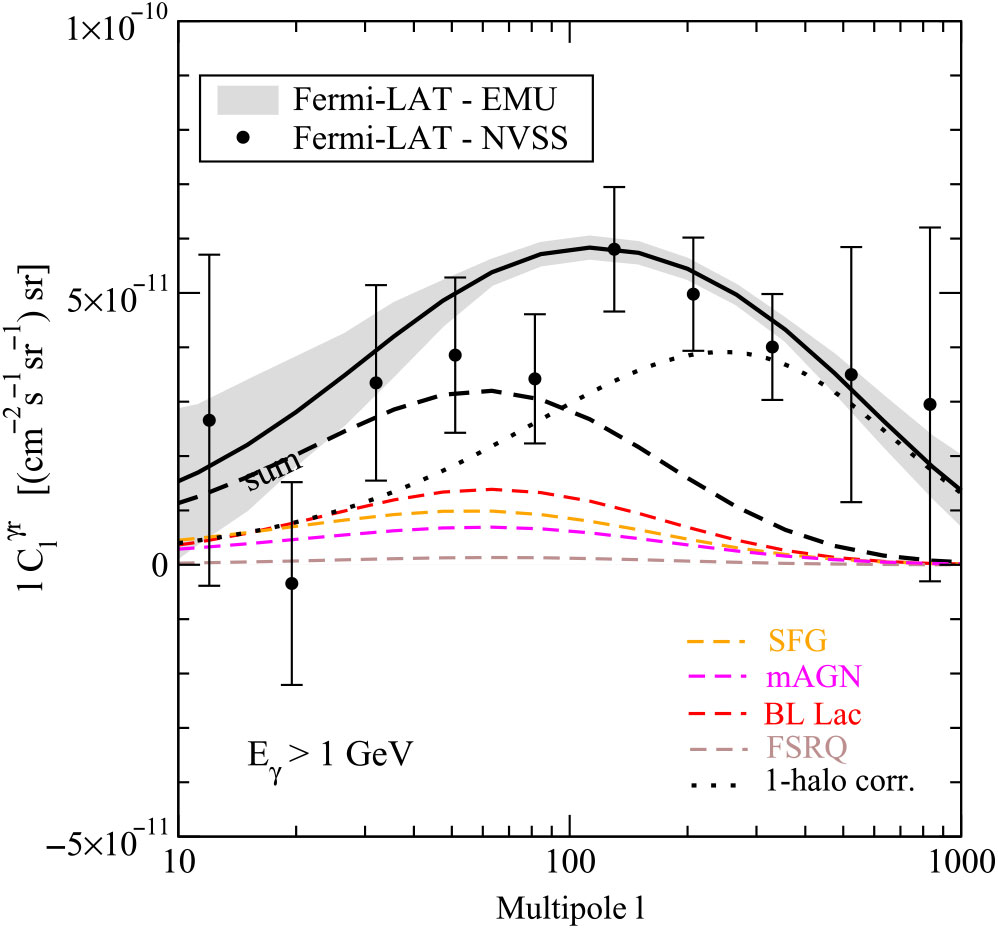

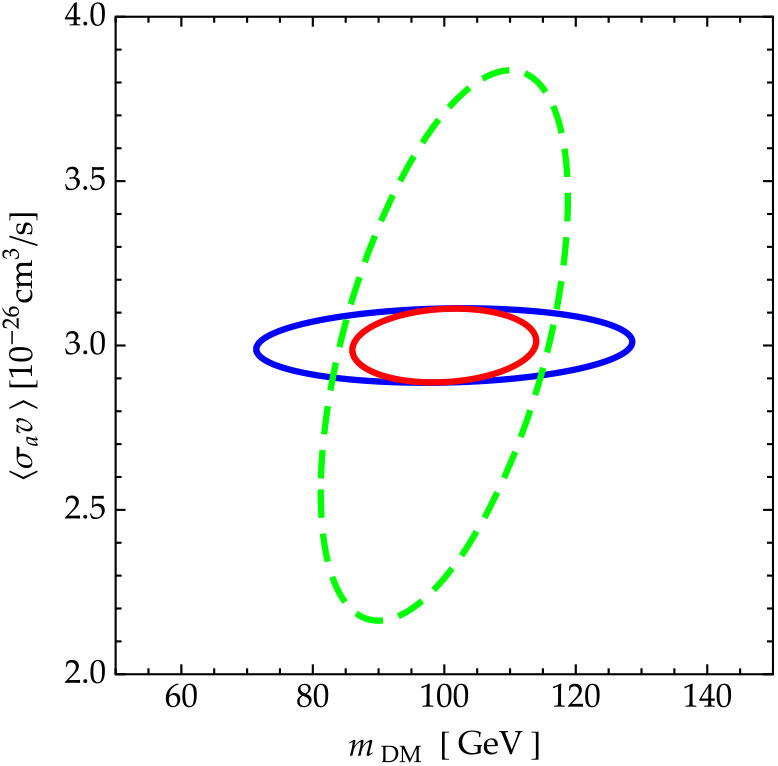

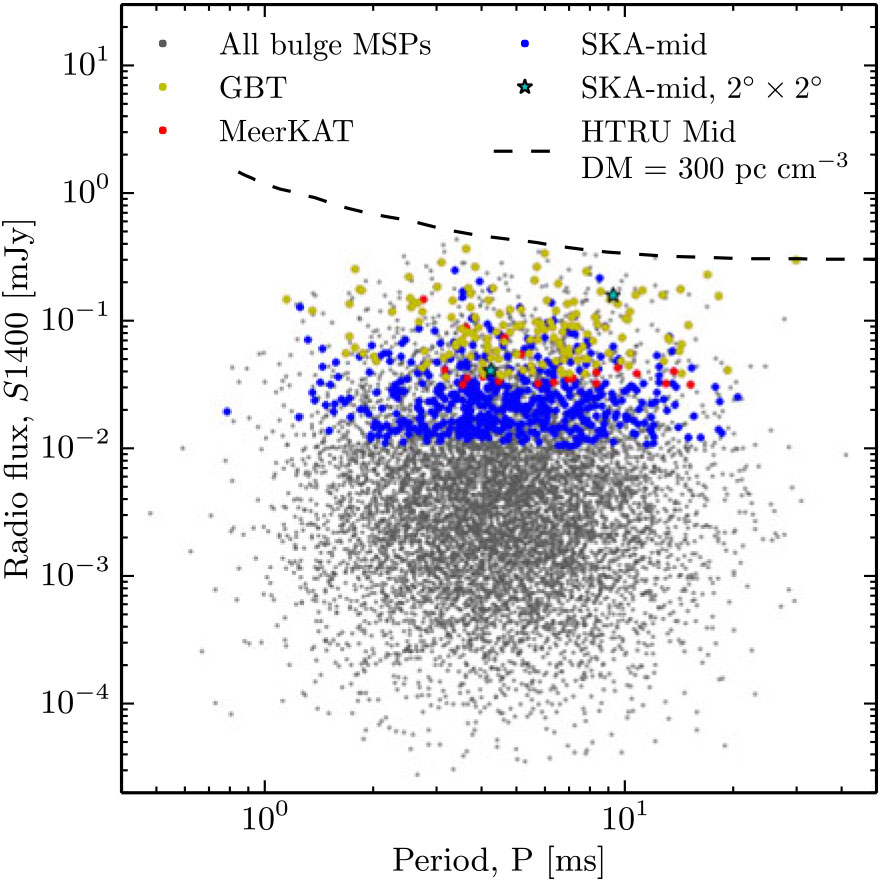

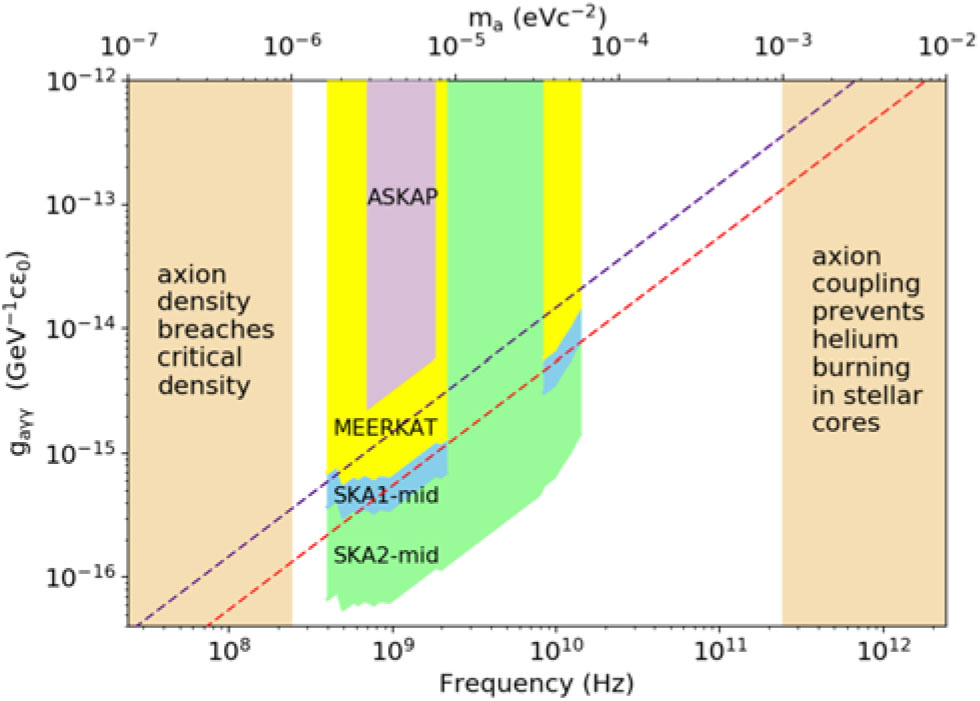

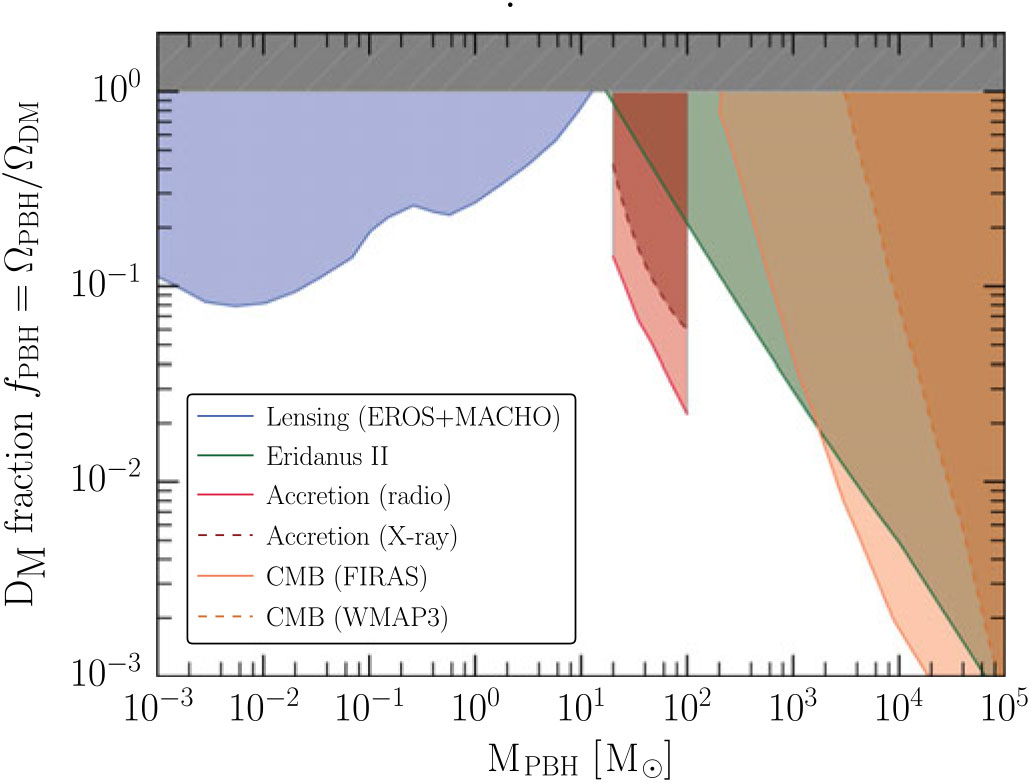

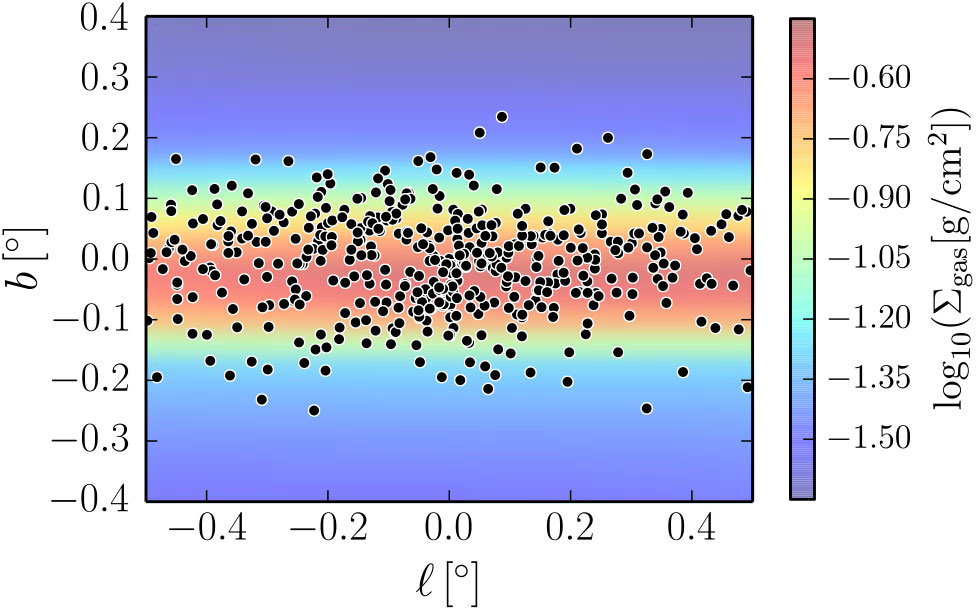

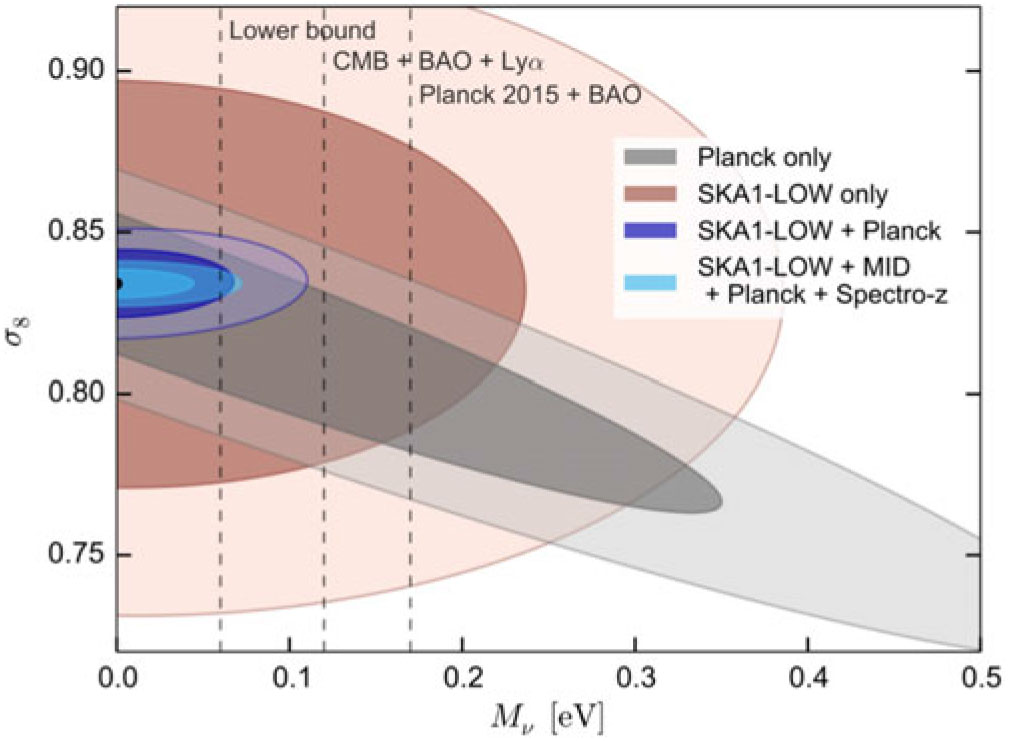

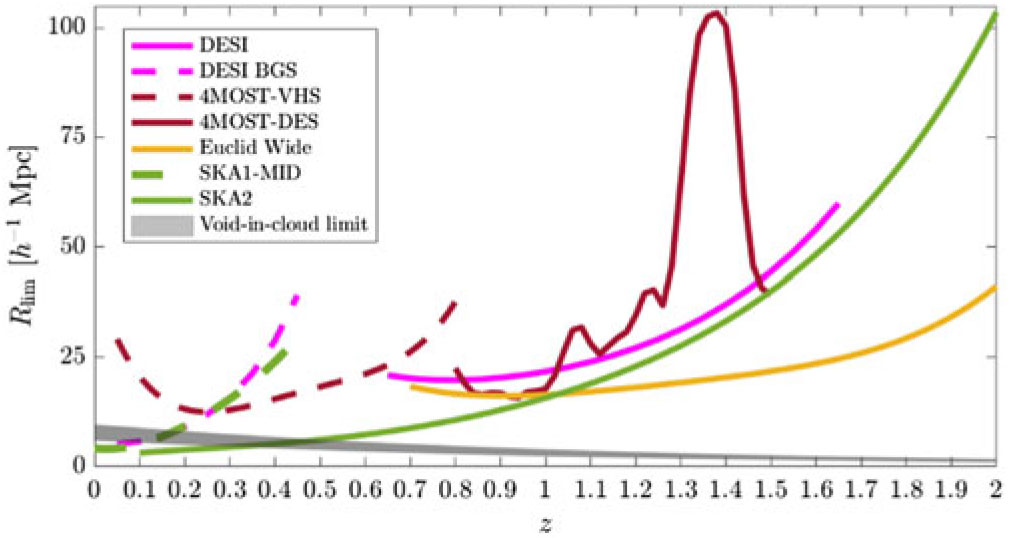

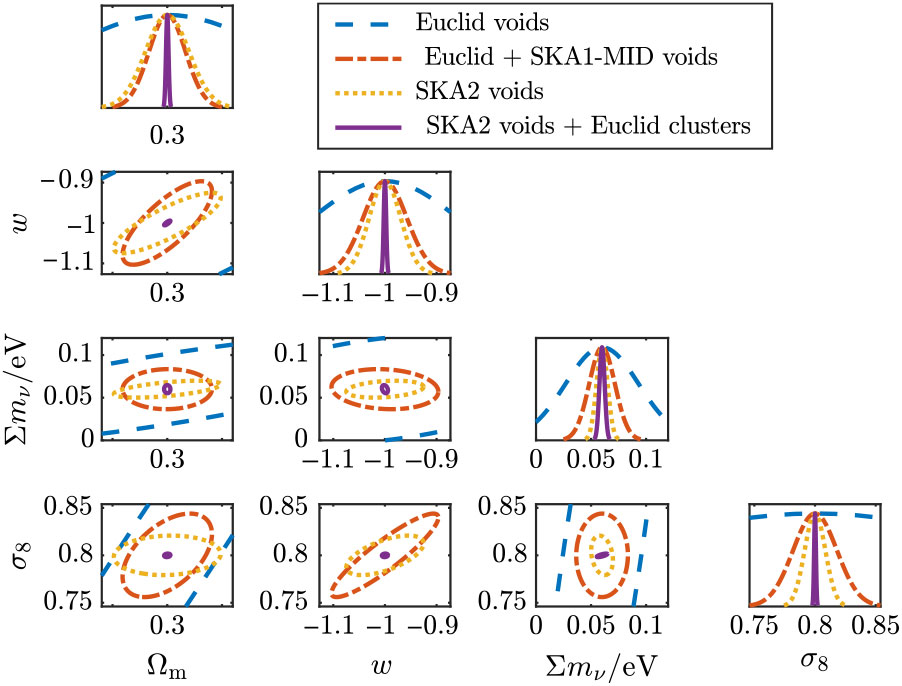

10^{6}-10^{7}$, with a BB spectrum thanks to the combined effect of Compton scattering and photon emission/absorption processes (double Compton and bremsstrahlung) in the cosmic plasma, which, at early times, are able to re-establish full thermal equilibrium in the presence of arbitrary levels of perturbing processes. Subsequently, the efficiency of the scattering and above radiative processes decreases because of the expansion of the Universe and the consequent combined reduction of particle number densities and temperatures, and it was no longer possible to achieve the thermodynamical equilibrium.