Adolescence is a critical period for mental disorders, with a high percentage of all lifetime mental disorders detected for the first time by age 14 years(Reference Kessler, Berglund and Demler1). Globally, approximately 20 % of children and adolescents have mental disorders or mental health-related problems, and half of these cases are diagnosed before the age of 14 years(Reference Patel, Flisher and Hetrick2). During this period, mental health is strongly related to other developmental and health conditions. Investigations of clinic and community samples report that depression in adolescence can predict further problems by influencing quality of life, academic performance, social activities and even obesity in later life(Reference Mufson, Weissman and Moreau3–Reference Goodman and Whitaker6). It has been reported that there is a high co-occurrence of depression and general anxiety disorders in adolescents(Reference Kessler, DuPont and Berglund7). Brady and Kendall(Reference Brady and Kendall8) performed a literature review regarding anxiety and depression in children and adolescents and estimated that 15·9–61·9 % of children with anxiety or depression had co-morbid anxiety and depressive disorders. Because the prevalence of mental disorders is high and causes effects on the physiological and psychological development of adolescents, the prevalence of mental disorders has become a major health problem(Reference Patel, Flisher and Hetrick2). Therefore, it is necessary to understand potential risk factors for mental health disorders in young people in an effort to formulate appropriate measures for early prevention and intervention.

Diet is usually investigated in lifestyle-mediated diseases(Reference Hu, Manson and Stampfer9). In recent years, dietary patterns have been the subject of increased attention in the field of adolescent mental health. Researchers noticed that inadequate nutrition and poor diet quality (fast food, confectionery items, animal foods) are more frequently associated with mental problems(Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby10–Reference Howard, Robinson and Smith15). A cross-sectional relationship between diet quality and depression was verified in a large sample of adolescents from a diverse range of sociodemographic backgrounds(Reference Jacka, Kremer and Leslie13). The intakes of fruit, vegetables, meat, snacks and other healthy foods were also assessed and shown to be related with mental or physical disorders in adolescents(Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby10, Reference Li, Zhang and McKeown16, Reference O'Sullivan, Robinson and Kendall17). Unlike other diet research methods, dietary pattern analysis is used for characterizing the whole diet in combination. The use of FFQ has been validated in adolescents, sometimes even better than the 24 h recall approach(Reference Slater, Enes and Lopez18). FFQ can capture complex behaviours and potentially interactive effects among special nutrients that might impact mental health(Reference Jones-McLean, Shatenstein and Whiting19). However, there are only a limited number of studies evaluating the association between special dietary patterns and mental disorders in adolescents(Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby10, Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini20). For example, in a recent study conducted in adolescents aged 13–15 years, Oddy et al.(Reference Oddy, Robinson and Ambrosini20) suggested that an increased adherence to a Western dietary pattern was associated with higher scores on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), resulting in poorer mental health.

Adolescence is a stage when independence is established. Certain dietary patterns may be adapted by adolescents and might be followed for a long period. Consequently, unhealthy dietary patterns during youth would have profound implications for well-being in adulthood. In China the lifestyle and dietary habits of adolescents have changed in recent decades. Specifically, a higher percentage of urban adolescents consume more fast foods and sweetened beverages(Reference Wang, Zhai and Du21). There are few studies that have assessed the role of dietary patterns with respect to adolescent mental health in China. Therefore, we determined the associations between major dietary patterns and the prevalence of depression and anxiety among Chinese adolescents.

Methods

Sample and procedures

The aerobic exercise intervention study is a school-based study investigating the effect of aerobic exercise on adolescent mental health which was conducted from September 2010 to October 2010 in Bengbu, Anhui Province, China.

The sampling scheme was a one-stage random cluster sample. The cluster sampling frame comprised all twenty-one junior schools in Bengbu city. We randomized four of twenty-one junior high schools (grades 7–9) on the basis of a computer-generated random number table that was in the hands of a person not involved in the study. All students and their parents in the four schools gave informed consent. A self-administered questionnaire survey was administered a week before anthropometric measurements were made. According to anonymous and voluntary participation, students completed questionnaires during one class period (45 min) without interruptions. The students’ height, weight and waist circumference were measured and recorded by trained postgraduate students and school physicians. As of November 2010, 5340 students had completed the baseline questionnaire. There were 265 students who had incomplete anthropometric data and fifty-eight incomplete questionnaires (more than 15 % of information was missing). Fourteen students were excluded for receiving psychotropic medications or mental health treatment during the study period or had a history of substance abuse. A total of 5003 students were available at baseline for follow-up. For the present study we analysed data collected at baseline only.

Instruments

Dietary assessment

Habitual dietary patterns were assessed by a comprehensive and self-administered FFQ, which was designed to measure the dietary habits of the adolescents. The time of consumption for each food or food group per week was determined. According to the dietary features of the target population, the FFQ was modified on the basis of a previous questionnaire(Reference Wang, Popkin and Zhai22). The FFQ included thirty-eight food items which are commonly consumed by Chinese adolescents. Each item represents a food group. Students were asked to indicate the consumption frequency during the previous 7 d that best described their intake. There were five frequency options, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘9 or more times’ per 7 d, excluding alcoholic beverages. Each option was scored as follows: ‘never eat’ = 0; ‘1–3 times’ = 1; ‘4–5 times’ = 2; ‘6–8 times’ = 3; and ‘more than 8 times’ = 4. The FFQ focused only on the frequency of each food item, and information on the portion size was not included.

Depression and anxiety assessment

Depression symptoms were measured by the Chinese version of the Depression Self-rating Scale for Children (DSRS), as developed by Birleson(Reference Birleson23). The DSRS was adapted to children 8–16 years of age and contained eighteen items, of which students self-reported the frequency of each item during the last week(Reference Birleson23, Reference Linyan, Kai and Yan24). Each item response was rated on a 3-point scale from ‘never’ to ‘more frequent’. A cut-off score of 15 was used to screen depression symptoms among children and adolescents. The scale has been validated, having content reliability in local children and young adolescents. The test–retest reliability, the split-half and Cronbach's α were in the range 0·53–0·73. The total score of the scale also showed a significant correlation with the corresponding subscale of the CBCL (r = 0·49–0·58) and the subscale of the Paiers–Harris Children's Self-concept Scale (r = 0·60–0·68; P values both <0·05)(Reference Linyan, Kai and Yan24).

The instrument used to screen anxiety symptoms of the students was the Chinese version of the Screen Scale for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED), as designed by Birmaher et al.(Reference Birmaher, Khetarpal and Brent25), which contained forty-one items allocated to five dimensions: somatic/panic; generalized anxiety; separation anxiety; social phobia; and school phobia. Students were asked to answer the frequency with which they experienced each symptom using a 3-point scale (0 = ‘almost never’, 1 = ‘sometimes’ and 2 = ‘often’). If the total score is more than 23, an anxiety disorder is screened. The validity and reliability of the SCARED (Chinese version) have been validated in a previous study(Reference Birmaher, Brent and Chiappetta26). The Chinese version of the scale also demonstrated good internal consistency, test–retest reliability (intra-class correlation coefficient = 0·46–0·77 over 2 weeks and 0·24–0·67 over 12 weeks) and good validity between anxiety and non-anxiety disorders(Reference Su, Wang and Fan27).

Anthropometric measurements

Measurements were performed by a team of trained nurses and interviewers who used the same standard methods in the baseline study. Body height, weight and waist circumference were measured. Positioning of the body was standardized by asking the student to stand straight without shoes and with the heels placed together. Weight was measured to the nearest 0·1 kg using an electronic body weight meter. Students were asked to wear light clothing and empty their bladder. Height was measured to the nearest 0·1 cm with a manual height board. Waist circumference was measured 1 cm above the umbilicus with a standard tape measure to the nearest 0·1 cm. The height and waist circumference were measured twice, and the mean value was recorded. BMI (kg/m2) and waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) were calculated to assess whether students were obese/overweight.

Covariate assessment

The sociodemographic information included age, gender, grade, family income, number of siblings, and maternal and paternal education. The family income was self-reported and classified in three levels ranging from ‘low’ (score = 1) to ‘high’ (score = 3). Maternal or paternal education was classified in four levels as follows: primary schooling or illiterate (score = 1); secondary schooling (score = 2); university or other tertiary qualification (score = 3); unknown (scored = 4). Physical activity was assessed based on the following question: ‘How many days in the past week have you had at least one moderate physical activity (i.e. an activity that leaves you out of breath or feeling tired some of the time) for 60 min or more (never/1 d/2 d/ 3 d or more)?’(Reference Prochaska, Sallis and Long28).

Statistical analysis

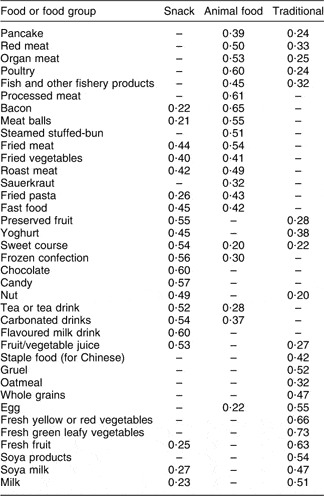

We used factor analysis (principal components) to derive dietary patterns based on the FFQ. Thirty-eight food items were entered into the factor analysis, and rotated by orthogonal transformation (varimax rotation) to maintain uncorrelated factors and greater interpretability. Inter-item reliability for each factor was assessed by Cronbach's α coefficients (Cronbach's α for the FFQ was 0·895 in the present study). Items were excluded for the absolute value of factor loading <0·2 (Table 2). We determined to retain three factors according to the eigenvalues in the scree plot, which accounted for 34·78 % of the variance in the dietary information. The three factors were labelled as ‘traditional’, ‘snack’ and ‘animal food’, and scores were saved as variables in the data set. For further statistical analyses, factors were treated categorically (tertiles). Trend associations between categorically demographic variables and dietary patterns were assessed using χ 2 analysis. Means (and standard errors) of BMI, WHtR and age were calculated according to tertile of dietary pattern scores using ANOVA, and BMI and WHtR were adjusted for age and gender.

Bivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the odds of sociodemographic variables for mental disorders. Multinomial logistic regression models, with all three dietary patterns entered simultaneously as exposure variables, and categorical ‘pure’ depression (depression without anxiety), ‘pure’ anxiety (anxiety without depression) and coexisting depression and anxiety as dependent variables, were fitted to determine the confounder-controlled association of the three dietary patterns with self-reported mental problems. In each dietary pattern the lowest tertile was designated as the reference group. Statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS statistical software package version 10·0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences were considered significant if P < 0·05.

Results

We assessed 2606 boys and 2397 girls in the present study. The mean age at recruitment was 13·21 (sd 0·99) years. Three dietary patterns were extracted from thirty-eight food groups (Table 1) in the FFQ using principal component analysis: snack, animal food and traditional. The factor-loading matrices for the three patterns are listed in Table 2. The snack dietary pattern was composed mainly of preserved fruit, a sweet course, frozen confection, yoghurt, chocolate, candy and carbonated drinks. The animal dietary pattern consisted of red meat, organ meat, processed meat, fried meat and other Chinese meat dishes. The traditional dietary pattern is a typically healthy and recommended diet, and included foods such as gruel, oatmeal, whole grains, fresh yellow or red vegetables, fruit and soya milk.

Table 1 The thirty-eight food items in the FFQ with examples

Table 2 Factor-loading matrix for the major factors (diet patterns) identified using food consumption data from the FFQFootnote *: adolescents (n 5003) aged 11–16 years, Bengbu, China, 2010

* Absolute values <0·20 were not listed in the table for simplicity. ‘Bread’ item was excluded.

The distribution of students’ sociodemographic and anthropometric characteristics across the three dietary patterns is shown in Table 3. A higher consumption of the snack dietary pattern was associated with female gender, being an only child in the family, higher level of maternal and paternal education, and age- and gender-adjusted lower BMI and WHtR. An increased frequency of consuming the animal dietary pattern was generally associated with male gender, being an only child in the family, lower level of maternal and paternal education, older age, and age- and gender-adjusted lower BMI and WHtR. Among those who followed a traditional dietary pattern, higher scores were associated with female gender, being an only child in the family, higher family income, higher maternal and paternal education level and younger age.

Table 3 Distribution of demographic/anthropometric characteristics according to tertile of dietary pattern scores: adolescents (n 5003) aged 11–16 years, Bengbu, China, 2010

T1, lowest tertile of dietary pattern's score; T2, intermediate tertile of dietary pattern's score; T3, highest tertile of dietary pattern's score; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio.

*ANOVA was used for continuous variables and the χ 2 test for categorical variables to calculate P for trend across categories of dietary pattern.

†Values were unadjusted.

‡P value adjusted for age and gender.

Table 4 contains data on the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders and the associated sociodemographic and anthropometric characteristics. The prevalence of depression, anxiety and coexisting depression and anxiety was 11·2 %, 14·6 %, and 12·6 %, respectively. A high risk of depression or anxiety was associated with girls, being an only child in the family, low maternal and paternal educational level, low family income and lack of physical activity.

Table 4 Association between demographic/anthropometric characteristics and pure depression, pure anxiety and coexisting depression and anxiety: adolescents (n 5003) aged 11–16 years, Bengbu, China, 2010

WHtR, waist-to-height ratio.

*Depression self-rating scale score ≥15.

†Child anxiety related emotional disorders scale score ≥23.

‡Self-reported variables.

Table 5 shows that the prevalence of mental disorders, especially coexisting depression and anxiety, was associated with higher tertiles of the snack and animal food dietary pattern scores; however, an inverse correlation was observed between the traditional dietary pattern and depression and anxiety.

Table 5 Prevalence of mental symptoms by tertile of dietary pattern scores: adolescents (n 5003) aged 11–16 years, Bengbu, China, 2010

T1, lowest tertile of dietary pattern's score; T2, intermediate tertile of dietary pattern's score; T3, highest tertile of dietary pattern's score.

Results from multiple logistic regression analyses, with all three dietary patterns entered simultaneously as exposure variables, and categorical pure depression, pure anxiety and coexisting depression and anxiety as outcomes, demonstrated that the highest tertile scores in the snack dietary pattern were associated with higher odds for depression and anxiety disorders, associations which were strengthened by all adjustments for age, gender, maternal and paternal education, family income, BMI and physical activity in model 3 (Table 6). The traditional dietary pattern was associated with decreased odds for the three categories of mental disorders in the unadjusted and adjusted analyses.

Table 6 Odds ratios (95 % confidence intervals) from multiple logistic regression models for pure depression, pure anxiety and coexisting depression and anxiety according to tertile of dietary pattern scores adolescents (n 5003) aged 11–16 years, Bengbu, China, 2010

T1, lowest tertile of dietary pattern's score; T2, intermediate tertile of dietary pattern's score; T3, highest tertile of dietary pattern's score.

*T1 as reference group in all models.

†Model 1: unadjusted.

‡Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, maternal education, paternal education, family income and BMI.

§Model 3: adjusted per model 2 plus physical activity.

Discussion

In the present cross-sectional study among Chinese students attending junior high school, we have demonstrated a relationship between major dietary patterns and mental disorders. We used factor analysis to identify three major dietary patterns, specifically snack, animal food and traditional dietary patterns, which explained 35 % of the variance. The value was low but similar to the outcomes in previous studies(Reference Hu, Rimm and Smith-Warner29, Reference Newby and Tucker30).

High intakes of snacks and animal foods were shown to be associated with mental disorders, and a high intake of a traditional diet was associated with a decreased likelihood of mental disorders. These findings provide a new viewpoint for a multi-focus intervention aiming to improve mental health in Chinese adolescents.

The results suggest that high consumption of unhealthy diets (animal food and snack patterns), rich in energy-dense but nutrient-poor foods and snacks, is associated with a higher risk of depression and anxiety. These findings are in agreement with two recent epidemiological studies(Reference Crawford, Khedkar and Flaws31, Reference Liu, Xie and Chou32). Specifically, a positive correlation was shown between snack food intake and mental disorders among adults and older adolescents. Evidence from an observational study in Asian countries suggests that there is a correlation between sugar consumption and the annual rate of depression(Reference Westover and Marangell33). In a survey of 2579 Chinese college students, the relationship between food consumption frequency, perceived stress and depression was studied, and a higher intake of snack foods was shown to be significantly associated with depression(Reference Liu, Xie and Chou32). Overconsumption of snacks may contribute to excessive energy, fat and sugar intakes in adolescents, and snacks provide few of the micronutrients which are essential for optimal neurotransmitter function and involved in the pathologies of various psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, panic disorder and personality disorders(Reference Stein and Stahl34, Reference Wallin and Rissanen35).

In the current study gender was an important determinant of intake with respect to snack diets. Girls consumed more snack foods than boys. The findings are also supported by previous conclusions that females were ambivalent towards eating snacks, perceiving snacks as unhealthy, but preferred to eat especially under stress(Reference Grogan, Bell and Conner36, Reference Zellner, Loaiza and Gonzalez37). However, other authors have reported in Australian children and adolescents that boys had more extra food intake compared with girls(Reference Rangan, Randall and Hector38).

The traditional diet pattern, consisting of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, rice and some soya products, was inversely associated with the prevalence of psychological symptoms in our study. The findings herein are supported by findings from the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) prospective cohort study(Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Henriquez and Bes-Rastrollo39). In the SUN study adherence to a Mediterranean diet, ensuring adequate intakes of fruits, nuts, vegetables, cereals, legumes and fish, was considered an important protector against depression in adolescents(Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Henriquez and Bes-Rastrollo39). In addition to the aforementioned whole diet patterns, increased intakes of individual foods, such as vegetables, fruits, dairy and cereals, have also been linked with promoting or maintaining a healthy mental status(Reference Nemets, Nemets and Apter40–Reference Kaplan, Fisher and Crawford43). In the 1970 British cohort study(Reference Batty, Deary and Schoon44), children with higher mental abilities reported more frequent intakes of fruits, vegetables, wholegrain bread and low-fat meats, but lower intakes of chips, non-wholegrain bread and snacks as adults. In recent years, Western foods have become more available and popular among children and adolescents relative to traditional diet alternatives(Reference Birleson23, Reference Adair and Popkin45). Therefore, we suggest that further research regarding the impact of a decreased intake of healthy foods on mental disorders is needed.

With respect to the validity of capturing complex behaviours and potentially interactive effects among special nutrients that might impact mental health, there is growing recognition that special dietary patterns and their effects on mental health should be of concern in adolescents. In a recent study in Australia, Robinson et al.(Reference Robinson, Kendall and Jacoby10) examined lifestyle and demographic factors to identify the associations with mental problems (withdrawal, anxiety and depression, somatic complaints, delinquency, aggression) among younger adolescents. Six food groups were derived from a 212-item FFQ. The authors concluded that a higher intake of a ‘meat food’ diet pattern and an ‘extra food’ diet pattern (such as takeaway and snack foods) were significantly associated with a higher score on the Child Behaviour Checklist for Ages 4–18.

Although many studies have indicated a relationship between diet and mental disorders, the mechanisms are still not well understood. Some researchers have attempted to explain how diet and nutrition modulate biological processes underpinning mental disorders(Reference Bourre46, Reference Engelhart, Geerlings and Ruitenberg47); individual nutrients are often highlighted. Nutrients such as vitamin C, vitamin B12, folate, n-3 fatty acids and α-linolenic acid, flavonoids and Zn have been verified to maintain psychological well-being. A recent finding also suggested that trans-unsaturated fatty acids have a dose–response effect on clinical depression(Reference Sánchez-Villegas, Verberne and De Irala48). Therefore, the intake of special nutrients is often considered a mediator of the association between whole diet and mental problems(Reference Bjelland, Tell and Vollset49–Reference Ng, Berk and Dean52).

In the current study the prevalence of depression, anxiety and coexisting depression and anxiety was 11·2 %, 14·6 %, and 12·6 %, respectively. The rates of depression, anxiety and coexisting depression and anxiety are in agreement with previous studies regarding psychological symptoms. For example, by using the self-rating scale of the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition) for major depression symptoms, the prevalence of depression was 18·9 % and 17·0 %, respectively, among 15- and 17-year-old adolescents in Sweden(Reference Sjoberg, Nilsson and Leppert53). In the present study we screened mental symptoms by using psychological scales rather than clinical diagnostic criteria. Thus, the observed prevalence of mental symptoms was indeed higher than that of major depression and anxiety(Reference Roberts, Roberts and Chen54). As a result, the interpretation of the results should be made with caution. In recent decades, Chinese society has experienced a massive socio-economic change and culture shock. Added to intense competition in education, psychological and behavioural problems are gradually increasing in the adolescent population. The high prevalence of depression and anxiety in the present findings also reveals that promoting adolescent mental health is needed in China.

There were several limitations in our study. The study had a cross-sectional design, which limited the conclusions to aetiological inferences that unhealthy dietary patterns may lead to mental conditions. Unhealthy food choices may be compensatory mechanisms for mental disorders, rather than a causative factor. It has been shown that depressed individuals report greater preferences for carbohydrates (especially high-carbohydrate foods), increased serotonin release and relief of stress(Reference Wurtman and Wurtman55), compared with individuals without depression. Therefore, in a further study, a longitudinal design would preclude reverse causality existing in the findings. Except for morphological indices, all other information was self-reported by adolescents and subject to social desirability bias. The rate of unhealthy diets or other risk behaviours may be underestimated. The study used psychological screening scales rather than clinical diagnostic criteria to evaluate depressive symptoms and anxiety, which might lead to an overestimate of the incidence of depression or anxiety in adolescents. The adolescents who participated in the study were mainly from urban areas with Han nationality and lived in the same city, thus affecting the sample representation and further generalization of the results. There are various kinds of foods in the Chinese diet such that it is difficult for younger adolescents to recall portion size of foods they have eaten several days before. The FFQ was designed so that interviewees could provide answers more easily, without information on the portion size of each food item. As a result, the FFQ is limited with respect to the variability of the food consumption. It is impossible to rule out residual confounding or information bias by family variables as a factor in these findings.

Conclusions

Our study was designed to determine the association between overall diet and depression and anxiety symptoms in a large sample of Chinese adolescents. It was found that the snack and animal food patterns were associated with a high risk of depression and anxiety, while the traditional diet pattern was associated with a low risk for them after adjustment for relevant confounders. The study provided epidemiological evidence of a robust association of traditional, snack and animal food diets with mental symptoms in Chinese urban adolescents. Additional cohort studies involving dietary patterns and mental disorders in Chinese children and adolescents are warranted to investigate the predictive effect of habitual dietary behaviours on mental health in adolescence, as well as adulthood.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 30972494, 81072310, 30901202 and 30901203). The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors’ contributions were as follows. Conception and design: F.-B.T., J.-H.H., T.-T.W. and H.C.; acquisition of data: T.-T.W., H.C., J.-L.F., L.H., Q.-W.Q. and Y.S.; drafting of the manuscript: T.-T.W.; final approval of the manuscript: T.-T.W., F.-B.T. and J.-H.H.; statistical expertise: T.-T.W., J.-H.H. and F.-B.T. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data.