The literature in the field of public health has reported numerous health benefits associated with greater consumption of fruit and vegetables (F&V) and lower consumption of ultra-processed foods( Reference Wang, Ouyang and Liu 1 , Reference Monteiro, Levy and Claro 2 ). The individual’s ability to make healthy food choices is determined by the foods available and accessible. Interventions that can influence food-related processes, such as urban gardens, help promote healthy choices. Access to urban gardens appears to be an important determinant of local availability of F&V( Reference Kamphuis, Giskes and de Bruijn 3 ). Therefore, the objective of the present review was to identify and summarize studies that have reported the influence of participation in urban gardens on food and nutrition-related outcomes.

Studies have reported that daily F&V intake promotes health( Reference Boeing, Bechthold and Bub 4 ). The WHO recommends a minimum consumption of 400 g of F&V daily to prevent chronic diseases, such as CVD, cancer, diabetes type 2 and obesity( 5 ). However, a large proportion of the world’s population has low F&V intake. Data on 196 373 adults from fifty-two low- and middle-income countries showed that about 78 % of men and women fail to meet the WHO daily recommended intake of F&V( Reference Hall, Moore and Harper 6 ). Empirical evidence on environmental influences on F&V consumption indicates that good local availability, such as access to gardens, appears to have a positive influence on consumption( Reference Kamphuis, Giskes and de Bruijn 3 ).

In the last 20 years, the community gardening movement has grown rapidly in many countries and, together with producers’ markets, organic markets, slow food, fair trade and food cooperatives, among others, it forms the Food Movement driven by the community at large( Reference Walter 7 ). Food Movement can be understood as an urban social movement that struggles to identify eaters primarily as citizens as opposed to consumers, and it promotes a food security strategy( Reference Walter 7 , Reference Levkoe 8 ). Community gardens, in the Food Movement context, can offer ‘opportunities for collective learning about food security, environmental sustainability, community resilience, social justice and cultural identity’( Reference Walter 7 ). Recent research has been increasingly addressing the influence of urban gardening, both community gardens and domestic gardens, on a variety of outcomes, such as quality of life and physical activity( Reference Sommerfeld, Waliczek and Zajicek 9 ), mental health( Reference Shiue 10 ), social relationships and sense of belonging to the community( Reference Teig, Amulya and Bardwell 11 , Reference Harris, Minniss and Somerset 12 ), income generation( Reference Ribeiro, Bógus and Watanabe 13 ), social inclusion( Reference Grabbe, Ball and Goldstein 14 ), self-reliance and empowerment( Reference Costa, Garcia and Ribeiro 15 ), and practising and sharing knowledge and skills with others( Reference Harris, Minniss and Somerset 12 ), among other benefits.

A close relationship between urban gardens and food and nutrition is evident, given that most garden-grown produce is meant for own consumption, sharing or sale at local markets, thus bringing benefits not only to the participants but also to the community( Reference Machado and Machado 16 ). Although results have already been reported on broader food-related outcomes, such as contribution to food security through enhanced access to culturally appropriate foods( Reference Harris, Minniss and Somerset 12 ), increased consumption of F&V is the most prevalent dietary outcome found in the literature and has been frequently reported for school gardens( Reference Ganann, Fitzpatrick-Lewis and Ciliska 17 – Reference Davis, Spaniol and Somerset 19 ). Considering that a growing number of scientific studies involve urban gardening, a substantial and heterogeneous body of literature is now available on food and nutrition outcomes in adults from experiences with urban gardens. Two systematic reviews on urban gardening and various dimensions of dietary outcomes conducted in recent years were found in the literature. However, both of these studies involved children and youth( Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Story and Heim 20 , Reference Masset, Haddad and Cornelius 21 ), hence there is a gap in studies in adults. Robinson-O’Brien et al.( Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Story and Heim 20 ), assessing the impact of garden-based youth nutrition intervention programmes on nutrition-related outcomes, reported increased willingness to try F&V, improved knowledge on nutrition, greater probability of cooking and other outcomes. Masset et al.( Reference Masset, Haddad and Cornelius 21 ), in a study that assessed the effectiveness of agricultural interventions for improving the nutritional status of children and other intermediate outcomes in developing countries, reported positive effects on dietary composition, with higher production and consumption of healthy foods.

To date, no systematic reviews have been published on which dimensions of food and nutrition-related outcomes are being reported in adults. Thus, the objective of the present literature review was to identify the impacts on food and nutrition-related outcomes of participation in urban gardens, and to use these data to answer the following research questions:

-

1. Is participation in urban gardens positively associated with healthy food practices?

-

2. Is participation in urban gardens positively associated with healthy food access?

-

3. Is participation in urban gardens positively associated with healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes?

Additionally, we used the results to assess whether the associations reported between participation in urban gardens and food and nutrition-related outcomes vary by type of study, type of garden (community or domestic) or population health status.

Methods

The current systematic review is reported using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) writing guidelines to guarantee the quality of the research process and assure transparent reporting of the review.

Selection criteria

The PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) method was used to devise the following research question for the systematic review: ‘What is the influence of participation of adults in urban gardens on food and nutrition-related outcomes?’( Reference Santos, Pimenta and Nobre 22 ).

For inclusion in the review, studies had to meet the following eligibility criteria: (i) study published as an original article in a peer-reviewed scientific journal in English, Spanish or Portuguese between 2005 and 2015; (ii) study population comprising adults living in urban areas, irrespective of whether other age groups were involved; (iii) study objective of participation in urban gardens; and (iv) assessing or reporting food-related outcomes in the contexts of health promotion and food security. For the purposes of the review, healthy diet was defined as a determinant of health, diet was considered culturally and socially constructed, and the dimensions of social determinants, access, environment and food systems were addressed( Reference Pinheiro 23 – 25 ).

Information sources

Five databases were used for the search conducted between January and February 2016: PubMed, LILACS, ERIC, Embase and Web of Science. Experts in the field of urban agriculture were asked, both by email and personally, to identify studies that might meet the inclusion criteria. Lastly, the reference lists of the selected articles were hand-checked.

Search

The search strategy consisted of descriptors of each database relative to intervention AND population AND outcome. In accordance with PRISMA guidelines, the search strategy used in each database included in the systematic review is given in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1.

Table 1 Characterization of studies regarding the impact of participation in urban gardens on food-related outcomes in the context of health promotion and food security, and key results

CG, community garden; HgA1c, glycated Hb; F&V, fruit and vegetable; DG, domestic garden; NR, not reported; NGO, non-governmental organization.

Study selection

With the aid of EndNoteTM reference manager, all hits were organized and duplications removed. By applying the previously outlined eligibility criteria, the articles were independently selected by two reviewers (M.T.G., S.M.R.), both with prior experience in food security and health promotion. Titles and abstracts of the articles were first selected to satisfy the selection criteria. Discrepancies were subsequently discussed based on reading of the full texts until a consensus was reached. Disagreements on inclusion were decided by a third examiner (C.M.B.). Finally, the potentially eligible studies were assessed by reading of the full texts.

Data extraction

Data extraction from the selected articles was undertaken by one of the authors and the completed spreadsheet, which had been designed to answer the research question, checked by another author to ensure accuracy and scope. The following information was extracted: (i) publication details (authors, year of publication); (ii) location; (iii) objective; (iv) design (duration); (v) participation; (vi) outcomes investigated; (vii) method of measuring outcomes; (viii) food and nutrition-related outcomes; and (ix) study quality, as assessed using the COREQ( Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig 26 ) (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research) for qualitative studies and using the instruments of the National Institutes of Health( 27 ) for quantitative studies.

The COREQ( Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig 26 ) is a thirty-two-item checklist for interviews and focus groups comprising three domains: ‘research team and reflexivity’ (eight items), ‘study design’ (fifteen items) and ‘analysis and findings’ (nine items). The following instruments of the National Institutes of Health( 27 ) were used: Quality Assessment Tool for Before–After (Pre–Post) Studies With No Control Group (twelve items) and Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (fourteen items). The following quality ratings were attributed to the studies: ‘strong’ where 66 % or more of the quality assessment criteria were satisfied; ‘moderate’ when 33–65 % of criteria were satisfied; and ‘weak’ when 32 % or less of the criteria were satisfied.

One of the studies used qualitative and quantitative approaches, and in this case quality assessment of both components was performed. Qualitative component ratings were decided by consensus because they were used to assess food-related outcomes. Inconsistencies in ratings were subsequently discussed until a consensus was reached.

Summary of results

Owing to the heterogeneous nature of the included studies, a narrative summary of included studies was prepared. The study outcomes were not directly comparable; therefore studies were read and the food and nutrition-related dimensions reported in the study outcomes were subsequently identified. Differences and commonalities between study results were identified, collated and described narratively. Statistically significant and non-significant results were reported.

Results

Study selection

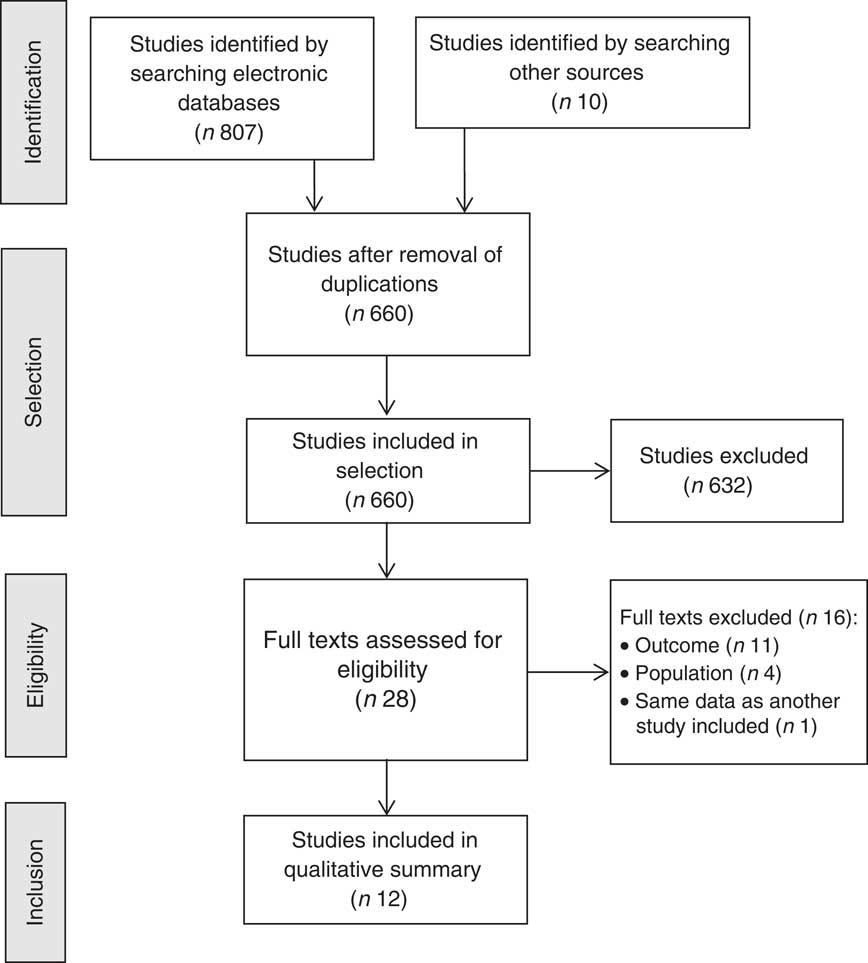

The search of the databases led to the retrieval of 807 studies (five in LILACS, 409 in PubMed, 338 in Embase, nine in ERIC and forty-six in the Web of Science). A further ten articles – derived from indication by researchers or hand-searching of the list of references of relevant studies – were also included. After exclusion of 158 duplications, 660 articles were considered eligible for the next stage of selection. Based on titles and abstracts, twenty-eight articles were short-listed for reading of their full texts. Sixteen publications were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria; thus, a total of twelve articles were included in the present systematic review( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 – Reference McMahan, Richey and Tagtow 39 ). Figure 1 shows the study selection process and the related flowchart.

Fig. 1 Flowchart of the study selection process in the current review on the impact of urban gardens on adequate and healthy food

Study characteristics

The majority of the studies involved existing gardens while only four studies assessed interventions( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 – Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 , Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 ). Of these interventions, three had pre- and post-intervention without a control group, and one was a cross-sectional qualitative study. The eight studies on existing gardens were observational, comprising seven cross-sectional (three quantitative and four qualitative) studies and one cohort study. The sample size of the studies varied considerably, ranging from twelve to 855 participants.

Table 1 provides an overview of the main characteristics of the twelve studies included in the current review.

The reported results were grouped into three categories representing food and nutrition-related dimensions: ‘healthy food practices’, ‘healthy food access’ and ‘healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes’. The studies and their outcomes by nutrition-related dimension are given in Table 2.

Table 2 Results reported by food-related outcome dimensions in the context of health promotion and food security

Studies reporting outcomes on healthy food practices

Seven studies reported outcomes on healthy food practices. Studies that reported outcomes on this dimension addressed increases in the amount and variety of F&V consumed( Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 , Reference Hale, Knapp and Bardwell 31 , Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 – Reference Alaimo, Packnett and Miles 35 , Reference Litt, Soobader and Turbin 37 , Reference McMahan, Richey and Tagtow 39 ), practice of a healthier diet( Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 , Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 ) and improved nutrition of the family( Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 ).

The study of Blair et al.( Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 ) reported an increase in intake of F&V servings/d and a positive impact on the family diet. Hale et al.( Reference Hale, Knapp and Bardwell 31 ) reported that participation in the gardens increased the amount and variety of vegetables consumed. Spees et al.( Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 ) revealed greater consumption of fresh foods, exposure to foods not previously tried, a more varied diet, and reduced consumption of red meat and ultra-processed foods. Wakefield et al.( Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 ) reported improved nutrition of the children and their family, and greater consumption of vegetables. Alaimo et al.( Reference Alaimo, Packnett and Miles 35 ) showed that individuals consumed F&V more times per day and were more likely to have consumed the recommended intake. Litt et al.( Reference Litt, Soobader and Turbin 37 ) showed higher F&V intake and a greater proportion of individuals consuming the recommended five daily servings. McMahan et al.( Reference McMahan, Richey and Tagtow 39 ) found that experience with gardening had a statistically significant relationship with F&V intake.

Studies of Weltin and Lavin( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 ), Giraldo et al.( Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 ), Scott et al.( Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 ), Wills et al.( Reference Wills, Chinemana and Rudolph 36 ) and Freeman et al.( Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ) did not report outcomes on healthy food practices.

Studies reporting outcomes on healthy food access

Eight studies reported outcomes on healthy food access. The studies that reported outcomes on this dimension addressed increasing access to healthy foods( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 , Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 – Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 , Reference Wills, Chinemana and Rudolph 36 , Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ), sharing produce( Reference Hale, Knapp and Bardwell 31 , Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 , Reference Wills, Chinemana and Rudolph 36 , Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 , Reference McMahan, Richey and Tagtow 39 ) and reducing food costs( Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 , Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ).

In the study by Weltin and Lavin( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 ), participants reported increased access to healthy foods, whereas Giraldo et al.( Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 ) noted an increase in availability of vegetable produce. Participants in the investigation of Hale et al.( Reference Hale, Knapp and Bardwell 31 ) regarded the foods grown as something to be shared with individuals and charities, in addition to reporting improved access to foods. Results of the study by Scott et al.( Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 ) showed that producing fresh F&V was one of the main reasons for gardening, where produce was for own consumption or to share with others. Other reasons for growing F&V included reducing food costs, as well as the satisfaction of sharing foods with friends and family members. Wakefield et al.( Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 ) reported better access to fresh and healthy foods, savings on food costs and sharing of foods. Wills et al.( Reference Wills, Chinemana and Rudolph 36 ) described greater access to vegetables and harvest sharing, while Freeman et al.( Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ) reported the strengthening of ties with neighbours through sharing foods grown and also the financial benefits of growing one’s own food. Individuals interviewed by McMahan et al.( Reference McMahan, Richey and Tagtow 39 ) reported F&V sharing.

Studies of Blair et al.( Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 ), Spees et al.( Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 ), Alaimo et al.( Reference Alaimo, Packnett and Miles 35 ) and Litt et al.( Reference Litt, Soobader and Turbin 37 ) did not report outcomes on healthy food access.

Studies reporting outcomes on healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes

Nine studies reported outcomes on healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes. Studies that reported outcomes on this dimension addressed greater interest in cooking and meal planning( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 , Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 , Reference McMahan, Richey and Tagtow 39 ), knowledge on the importance of healthy eating( Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 , Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 , Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 ), production and consumption of fresh pesticide-free foods( Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 , Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 , Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ) and strengthened connections with cultural roots( Reference Hale, Knapp and Bardwell 31 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 ).

Weltin and Lavin( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 ) reported greater interest in recipes and methods of preparing the foods grown. Blair et al.( Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 ) found that most participants reported that the experience had generally encouraged them to pursue a healthier diet and specifically to consume more vegetables, citing the importance of a healthy diet. Giraldo et al.( Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 ) reported that participants became knowledge multipliers within their families and communities. These authors also found assimilation of knowledge on the importance of daily consumption of vegetables as a protective factor against chronic non-communicable diseases and the application of the principles of urban agriculture to implement community and domestic gardens, without the use of products harmful to health, which are low cost and easy to set up. Hale et al.( Reference Hale, Knapp and Bardwell 31 ) reported that participants strengthened connections with cultural roots. According to Scott et al.( Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 ), one of the main benefits of the garden was better diet quality, and in particular the production of fresh pesticide-free foods. Outcomes reported by Spees et al.( Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 ) addressed greater interest in cooking and experimenting in the kitchen, given the enhanced ability for planning healthy meals and greater ability of the participants to consume a diet based largely on vegetables. Wakefield et al.( Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 ) highlighted greater consumption of culturally appropriate foods, growing of organic foods, knowledge on F&V and recipes containing these foods. Freeman et al.( Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ) found that growing vegetables was associated with the importance of consuming pesticide-free foods, contact with the Earth and environmental, social and political commitment. Individuals interviewed by McMahan et al.( Reference McMahan, Richey and Tagtow 39 ) cited greater frequency of serving meals made with F&V to others.

The studies of Alaimo et al.( Reference Alaimo, Packnett and Miles 35 ), Wills et al.( Reference Wills, Chinemana and Rudolph 36 ) and Litt et al.( Reference Litt, Soobader and Turbin 37 ) did not report outcomes on healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes.

Population health status, study types and garden types

Dividing the studies by population type revealed that three assessed individuals for health conditions( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 , Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 , Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 ), whereas the remainder did not report the health status of participants. Outcomes related to ‘healthy food practices’ were reported more often in studies involving individuals with diseases. Outcomes related to ‘healthy food access’ were more reported in the remaining studies.

Stratifying studies by design type showed that four studies investigated urban gardens as study interventions( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 – Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 , Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 ) and the remainder examined the experience of individuals in existing gardens. Proportionally, more studies in the group involving pre-existing gardens reported outcomes in the ‘healthy food access’ category. Outcomes for ‘healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes’ and ‘healthy food practices’ categories were reported more often among studies assessing interventions with urban gardens.

Dividing studies by urban garden type revealed that three assessed domestic gardens( Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 , Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 , Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ) while the remainder analysed community gardens. Studies on community gardens investigated more outcomes in the ‘healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes’ category. Outcomes related to the ‘healthy food access’ category were more frequently reported in studies analysing domestic gardens.

Quality analysis

The qualitative studies had better overall ratings than the quantitative investigations. The items of the COREQ checklist that contributed to low quality were related to omission of information on researchers, details about the data collection method, reference to data saturation, details on data analysis method and reference to participant feedback. For the quantitative studies, according to the National Institutes of Health instrument, the highest prevalence of non-compliance with criteria was related to measurement of previous exposure prior to measuring outcomes, measurement of level of exposure to gardens, and validity and reliability of measurements of exposure and of outcomes.

Discussion

The objective of the current review was to examine the impacts on food and nutrition-related outcomes as a result of participating in urban gardens by identifying positive associations with healthy food practices, healthy food access, and healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes. Taken together, the studies included in the review provide important information on the relationship between participation in urban gardens and dietary outcomes.

It is important to point out the origin of the studies included in the review and the journals in which they were published. Of the twelve studies assessed, ten were conducted in high-income countries, with seven from the USA, one from Canada, one from Australia and one from New Zealand, and they were published predominantly in North American and European journals. Notably, one of the databases holds indexed journals from Latin America and the Caribbean (LILACS) and although the preliminary search retrieved five studies, none were included in the review for failing to meet the eligibility criteria.

Among the quantitative cross-sectional studies( Reference Alaimo, Packnett and Miles 35 , Reference Litt, Soobader and Turbin 37 , Reference McMahan, Richey and Tagtow 39 ), none investigated the level of exposure to urban gardens, for example the definition of the type of garden (community or domestic) and participation time or frequency, hampering the generalization of results. Given that cross-sectional studies preclude the establishment of causality relationships between participation in community gardens and dietary outcomes of participants, it cannot be inferred whether individuals consuming healthier diets had greater interest in participating in community gardens or whether community gardens modified participants’ diets. All of the quantitative studies reported an increase in the amount and variety of F&V consumed, whereas the other outcomes such as sharing of harvest and knowledge on the importance of a healthy diet were reported less often. Other outcomes, such as cost savings on food and valuing of pesticide-free foods, were not reported. Perhaps owing to the nature of quantitative investigations, which should employ instruments for measuring predefined variables, the outcomes of quantitative studies covered fewer dimensions than those of qualitative studies. While quantitative studies reported mostly outcomes related to the ‘healthy food practices’ category, the majority of outcomes reported by qualitative studies pertained mainly to the ‘healthy food access’ and ‘healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes’ categories.

Eight studies used the qualitative approach( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 , Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 – Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 , Reference Wills, Chinemana and Rudolph 36 , Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ). Some of the studies did not set out to answer a pre-set question about dietary-related outcomes of participants; that information emerged spontaneously in reports when health benefits and behaviour changes were addressed, for example( Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 – Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 , Reference Wills, Chinemana and Rudolph 36 , Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ). Qualitative studies are fundamental for investigations in the field of food and nutrition, mainly because of the possibility of elucidating subjective output while contextualizing food as a mediator of relationships, since eating is not a fully measurable physiological act but involves social, political, psychic and aesthetic relationships( Reference Bosi, Prado and Lindsay 40 ).

The heterogeneity of settings, populations and assessment methods was high. In addition, the quality analysis of some studies indicated the need for greater methodological rigour. The methodological limitations reported in the current review had already been identified by previous reviews( Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Story and Heim 20 , Reference Masset, Haddad and Cornelius 21 ). These limitations may be due, in part, to the complexity of the theme. In view of the inherent subjectivity involved in collecting and analysing qualitative data, transparency is needed when presenting some components to demonstrate the methodological rigour required. According to Tong et al.( Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig 26 ), qualitative studies explore complex phenomena and can contribute with fresh knowledge and perspectives for health care, health policies and future studies. However, akin to quantitative studies, if poorly designed and with weak reporting of findings, qualitative studies may not be applicable in decision making( Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig 26 ). Particularly, information on the researchers, the theoretical basis of analysis, details on the data collection setting, the process of analysing the material collected and data saturation discussions were frequently omitted.

Different types of studies and approaches were included to gather distinct feelings and meanings about food, although they did not present the objectivity of parameters typically considered when systematic reviews are made. Among all the studies included in the review, outcomes related to increasing access to healthy food (‘healthy food access’ category) were the most prevalent, followed by the ‘healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes’ category and lastly by the ‘healthy food practices’ category. In fact, the process of promoting changes in dietary practices is complex and encompasses aspects such as beliefs, knowledge and attitudes. Among the ‘healthy food access’ category, the most reported dimension was perception of improved access to healthy foods( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 , Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 – Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 , Reference Wills, Chinemana and Rudolph 36 , Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ), followed by harvest sharing( Reference Hale, Knapp and Bardwell 31 , Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 , Reference Wills, Chinemana and Rudolph 36 , Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ). With regard to ‘healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes’, three dimensions were equally prevalent: assimilation of the importance of healthy food( Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 , Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 , Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 ), the valuing of cooking and planning healthy meals( Reference Weltin and Lavin 28 , Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 , Reference McMahan, Richey and Tagtow 39 ) and the valuing of growing and consumption of organic foods( Reference Giraldo, Torres and Cárdenas 30 , Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana 32 , Reference Wakefield, Yeudall and Taron 34 , Reference Freeman, Dickinson and Porter 38 ). Among the ‘healthy food practices’ category, the most reported dimension was greater consumption of F&V/fresh foods and more varied diet( Reference Blair, Madan-Swain and Locher 29 , Reference Hale, Knapp and Bardwell 31 , Reference Spees, Joseph and Darragh 33 – Reference Alaimo, Packnett and Miles 35 , Reference Litt, Soobader and Turbin 37 , Reference McMahan, Richey and Tagtow 39 ).

The fact that the ‘healthy food practices’ category featured more strongly in studies involving patients is congruent with the expectation that these individuals will change their dietary practices to exert a positive impact on their health conditions. Thus, it can be assumed that the actions implemented had this goal.

In the case of studies assessing domestic gardens, the issue of ‘healthy food access’ is closer, more relevant, readily achieved, perceived and reported. In community gardens, there is generally involvement of a larger number of individuals and greater likelihood of addressing aspects pertaining to the ‘healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes’ category, whereas access is reported less often because it is not necessarily sufficient.

The results also confirmed that the most recurrent focus of interventions in the food and nutrition-related area centred on the expectation of changes in dietary practices. This was evidenced by the greater presence of ‘healthy food beliefs, knowledge and attitudes’ and ‘healthy food practices’ categories in studies involving interventions than in those on pre-existing gardens.

Food behaviour is extremely complex and the product of interaction of multiple factors at individual (personal factors, such as motivation, expectations and self-reliance), social (networks, such as friends, family members and community), environmental (places where individuals consume or acquire food) and macro (more distal determinants such as food production and supply, prices and agricultural policies) levels( Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien 41 ). Adequate and healthy food in the context of food security and health promotion goes beyond the bounds of biomedical concepts that mainly assess the constituent nutrients of foods. Food is culturally and socially constructed and a basic human right; moreover, it is influenced by determinant processes relative to social aspects, access, the environment and food systems( Reference Pinheiro 23 , 24 , 42 ). In this respect, the findings of the present review confirm that interventions, such as urban gardens, are able to exert an impact on determinant processes at different levels and provide support for healthy choices, making them available and accessible to individuals.

Limitations

The present review has some limitations. First, the fact that the population studied comprised adults, which is a life stage that includes ages that differ in many aspects, may limit the interpretation of findings. Gardens may have different meanings and importance to people at different life stages or in different circumstances. Another limitation is the fact that both domestic and community gardens were included, two formats that have specific characteristics. Another limitation is the fact that the cut-off points adopted to attribute the concepts of strong, moderate and weak ratings to the studies were defined by the authors owing to the lack of consensus in the literature on this issue. However, various combinations of terms were employed on the relevant databases in a bid to retrieve as many studies as possible.

Conclusions

Based on the current review, the food and nutrition outcomes in adults who participate in urban gardens are promising. Analysis of the experiences with urban gardens revealed thematic patterns relative to adequate and healthy food in the context of food security and health promotion, such as greater F&V consumption, perception of improved access to healthy foods, harvest sharing, improved family diet, assimilation of the importance of adequate and healthy food, valuing of cooking and of planning healthy meals, and valuing of growing and consumption of organic foods. Although some studies indicated the need for greater methodological rigour, it is evident that participation in urban gardens, whether domestic or community, has a positive impact on important healthy food practices, access, and beliefs, knowledge and attitudes. The studies included in the present systematic review indicate that community interventions may produce changes in beliefs, knowledge and attitudes and can show broader reach and sustainability, by triggering the willingness for healthier food practices. Long-term studies on community gardens with these characteristics will be able to verify, by following more rigorous methodological aspects, the repercussions of changes in this direction; this will aim at indicating whether changes in beliefs, knowledge and attitudes can change practices, which is the expectation of results on healthy eating.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for the financial support. Financial support: This manuscript was supported by FAPESP (grant number 2012/21730-4). FAPESP had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper. Authorship: M.T.G. was involved in formulating the research questions, designing the study, carrying it out, analysing and interpreting the data, and elaborating the manuscript. S.M.R. was involved in carrying out the study, interpreting the data and the article revision. A.C.C.G.G. was involved in article revision C.M.B. was involved in formulating the research questions and article revision. All authors approved the final version for publication. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017002944