Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe and often chronic psychiatric disorder causing substantial personal and societal burden from severe and long-term disability. Schizophrenia is characterised by positive (e.g. hallucinations, delusions), negative (e.g. alogia, avolition, anhedonia), and disorganized symptoms (e.g. speech, behaviour) (Dollfus & Lyne, Reference Dollfus and Lyne2017), and is also associated with cognitive impairment. The typical onset of schizophrenia occurs in late adolescence to early adulthood, with a peak in prevalence around 40 years of age (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, Ferrari, Santomauro, Diminic, Stockings, Scott and Whiteford2018). Individuals with schizophrenia have a 15–20 years shorter life expectancy in comparison to the general population (Tanskanen, Tiihonen, & Taipale, Reference Tanskanen, Tiihonen and Taipale2018).

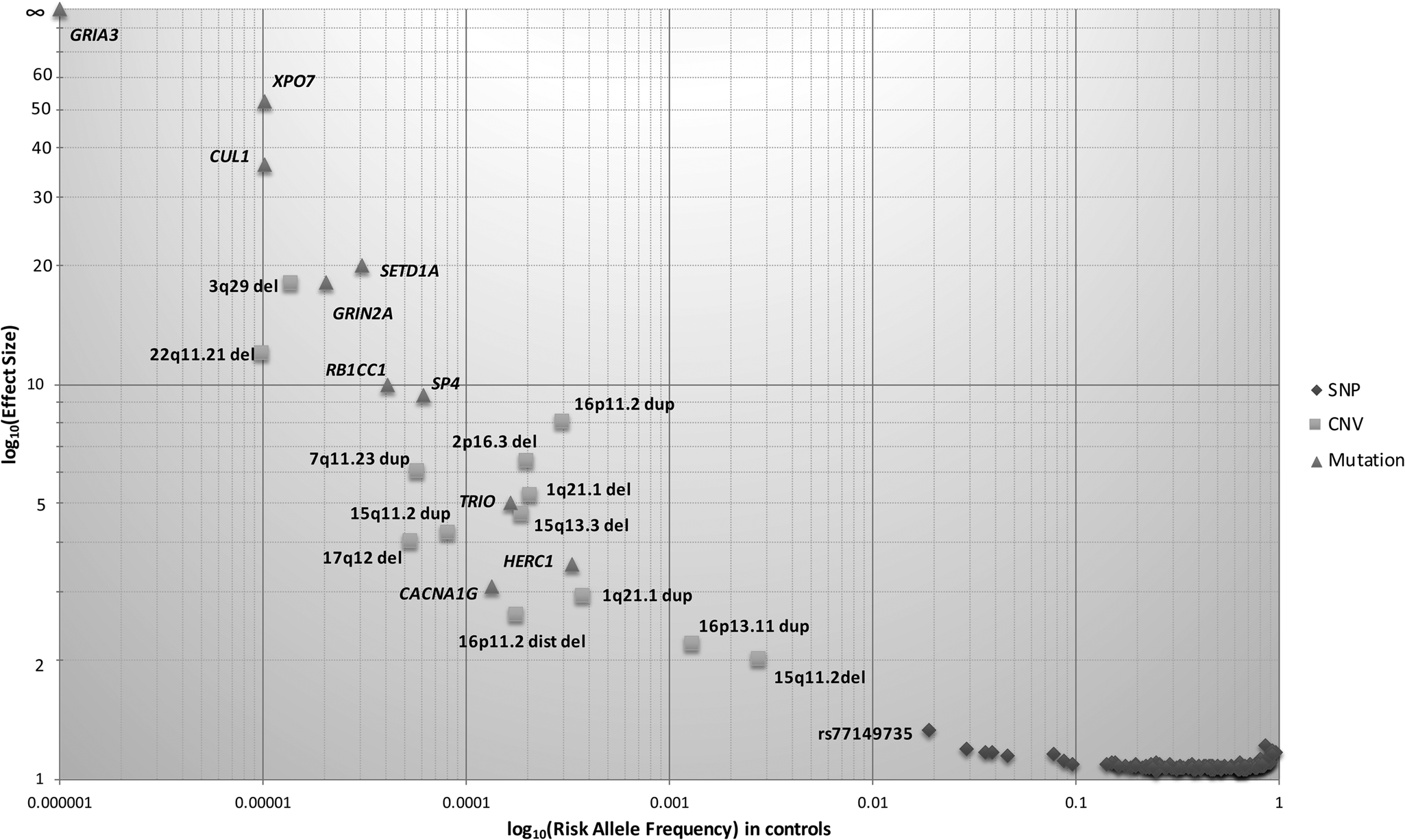

Schizophrenia is highly heritable and our understanding of the genetic architecture of schizophrenia has greatly increased over the past decade. This progress has arisen primarily through advances in molecular genetics technology, making feasible and affordable large-scale genotyping and sequencing, and through world-wide collaboration amalgamating research samples, exemplified by the Psychiatric Genetic Consortium (PGC). This collaborative effort has led to the identification of hundreds of common risk variants, rare variants and copy number variants (CNVs), providing key insights into the biological basis of schizophrenia (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Genetic architecture of schizophrenia. The risk allele frequency of SNPs and CNVs identified in Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) schizophrenia datasets are shown on the x-axis. The effect sizes of risk allele are shown on the y-axis. Many common alleles with small effect sizes have been identified (shown by diamonds), consistent with the common disease common variant hypothesis. Using genome-wide approaches, some rare copy number variants have also been identified (shown by squares), consistent with common disease rare variant hypothesis. Only a few less-common variants (0.01 < MAF ⩽ 0.05) have been identified due to large sample sizes. The effect size of identified risk allele is approximately inversely proportional to allele frequency.

Prevalence and incidence

The global age-standardised point prevalence of schizophrenia is estimated to be 0.28% (95% uncertainty interval: 0.24–0.31) (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, Ferrari, Santomauro, Diminic, Stockings, Scott and Whiteford2018). Globally, the number of prevalent schizophrenia cases increased from 13.1 million in 1990 to 20.9 million cases in 2016, with the largest increase occurring in Eastern sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa/Middle East triggered by high population growth in those areas (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, Ferrari, Santomauro, Diminic, Stockings, Scott and Whiteford2018). The incidence of schizophrenia has been reported to be 15.2/100 000 persons, with a median male: female rate ratio of 1.4 (McGrath, Saha, Chant, & Welham, Reference McGrath, Saha, Chant and Welham2008).

Morbidity and mortality

Although a low prevalence disorder, schizophrenia plays a major role in the global burden of disease, contributing approximately 13 million years of life lived with disability (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, Ferrari, Santomauro, Diminic, Stockings, Scott and Whiteford2018). Approximately 1 in 7 schizophrenia cases recover, based on clinical and social functioning indicators (Jaaskelainen et al., Reference Jaaskelainen, Juola, Hirvonen, McGrath, Saha, Isohanni and Miettunen2013). Poor outcomes are common and include premature mortality, long-term hospitalisation, treatment-resistance, and poor quality of life. The risk of suicide in those with schizophrenia is very high, with estimates of ~1 in 3 people with schizophrenia attempting suicide during their lifetime (Pompili et al., Reference Pompili, Amador, Girardi, Harkavy-Friedman, Harrow, Kaplan and Tatarelli2007). Individuals with schizophrenia are also subject to social disability (i.e. relationships with others, self-care), with research evidence including over 15 years of follow up time found that 25% have a severe social disability (Wiersma et al., Reference Wiersma, Wanderling, Dragomirecka, Ganev, Harrison, An Der Heiden and Walsh2000).

Individuals affected by schizophrenia experience a two- to threefold increased risk of death (median standardised mortality ratio for all-cause mortality = 2.6) (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Saha, Chant and Welham2008). Reasons for the excess deaths in schizophrenia include a high suicide and accident rate, poor health behaviours (e.g. smoking, substance abuse, obesity), adverse effects of antipsychotics, and under-diagnosis or under-treatment of general medical comorbidities (Bitter et al., Reference Bitter, Czobor, Borsi, Fehér, Nagy, Bacskai and Takács2017; Jerrell, McIntyre, & Tripathi, Reference Jerrell, McIntyre and Tripathi2010; Limosin, Loze, Philippe, Casadebaig, & Rouillon, Reference Limosin, Loze, Philippe, Casadebaig and Rouillon2007; Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal, & Stroup, Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup2015).

Environmental factors

Environmental factors act throughout life to influence the likelihood of disease, are not necessarily causative factors but can be largely grouped by timing into three categories: early development, proximal, and onset factors (Stilo & Murray, Reference Stilo and Murray2019). Early development factors include obstetric complications (Cannon, Jones, & Murray, Reference Cannon, Jones and Murray2002), and advanced paternal age (Sipos et al., Reference Sipos, Rasmussen, Harrison, Tynelius, Lewis, Leon and Gunnell2004). Proximal factors include social adversity, migration, and urbanicity. Meta-analyses have demonstrated migration as an important risk factor for schizophrenia in first- and second-generation migrants (Bourque, Van Der Ven, & Malla, Reference Bourque, Van Der Ven and Malla2011; Cantor-Graae & Selten, Reference Cantor-Graae and Selten2005), with a greater risk in migrants from developing countries (Cantor-Graae & Selten, Reference Cantor-Graae and Selten2005); pointing towards a role for psychosocial adversity in schizophrenia aetiology. Lastly, factors occurring around the time of schizophrenia onset include primarily drug abuse, trauma, and social adversity (Stilo & Murray, Reference Stilo and Murray2019).

Heritability

Heritability is a measure of the proportion of variation of a trait that is attributable to genetic inheritance (Young et al., Reference Young, Frigge, Gudbjartsson, Thorleifsson, Bjornsdottir, Sulem and Kong2018). Heritability estimates of schizophrenia are based on family studies (e.g. familial aggregation and twin studies) and vary based on the study methodology. While estimates have ranged from 41 to 87% (Chou et al., Reference Chou, Kuo, Huang, Grainge, Valdes, See and Doherty2017), the current estimate of heritability of schizophrenia is approximately 80% (Owen, Sawa, & Mortensen, Reference Owen, Sawa and Mortensen2016).

Common genetic variation

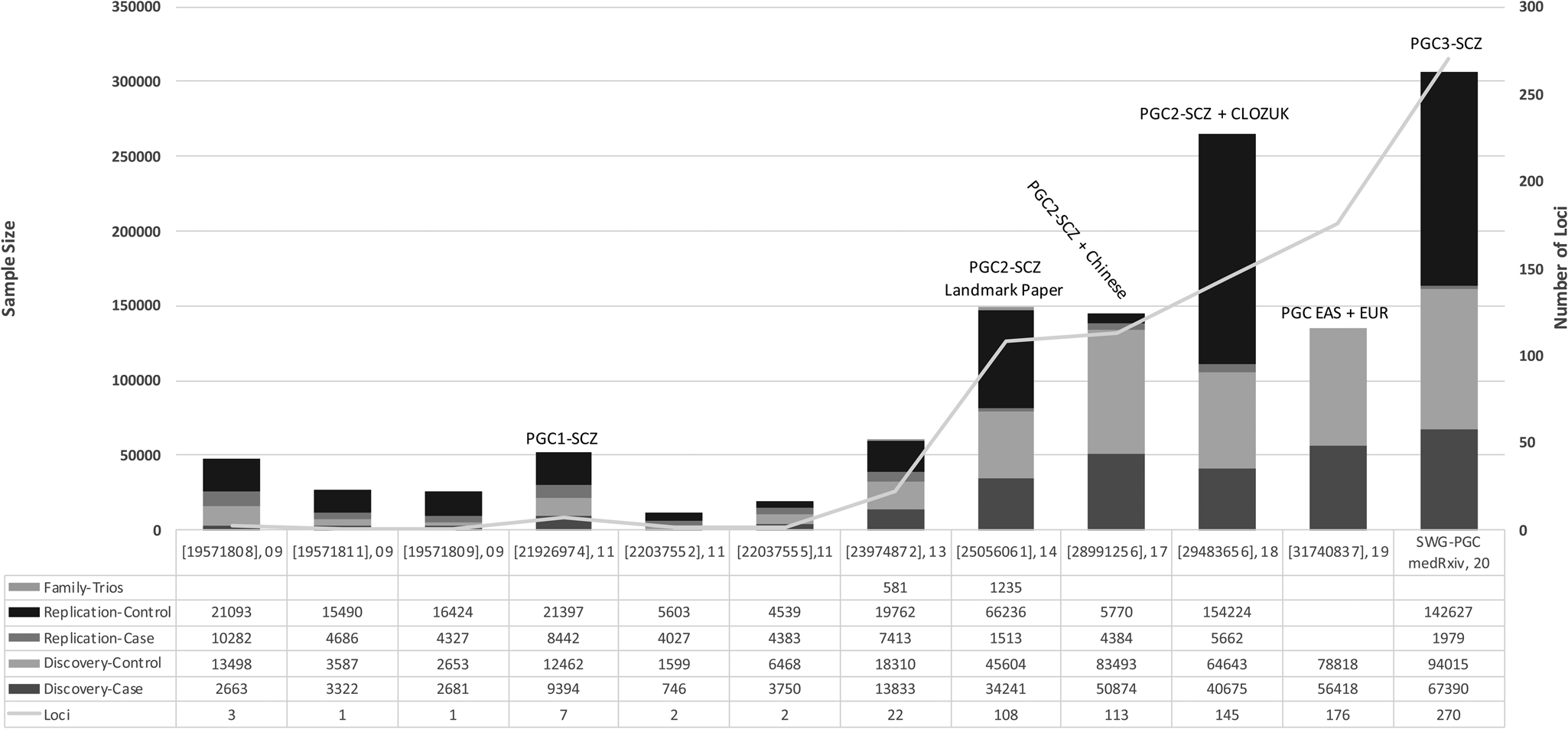

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) investigate millions of common genetic variants (or single nucleotide polymorphism, SNP) simultaneously to determine their association with a trait. Many of the early GWAS of schizophrenia were underpowered to identify common SNPs, which have typically been shown to have small effects in schizophrenia. Including the largest GWAS to date from the PGC, which is available as a pre-print, over 300 independent genome-wide significant variants (p ⩽ 5 × 10−8) have been associated with schizophrenia. Figure 2 visualizes the history of schizophrenia GWAS reported by key publications. In European populations, common variant associations identified from GWAS explain around one-third (24%) of genetic liability to schizophrenia (Lee, DeCandia, Ripke, Yang, & Wray, Reference Lee, DeCandia, Ripke, Yang and Wray2012; Ripke et al., Reference Ripke, O'Dushlaine, Chambert, Moran, Kähler, Akterin and Sullivan2013; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2014).

Fig. 2. The history of reported schizophrenia GWAS: The key publications (PMID, year of publication) since the initial discovery of schizophrenia genome-wide significant loci are shown on the x-axis. The sample size of reported schizophrenia GWASs is shown on the left-hand y-axis. The number of independent loci discovered in reported GWASs is shown on the right-hand y-axis. SWG-PGC, schizophrenia working group of the psychiatric genomics consortium.

The first reported genome-wide significant loci associated with schizophrenia came in 2009 (International Schizophrenia Consortium et al., Reference Purcell, Wray, Stone, Visscher, O'Donovan and Sklar2009; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Levinson, Duan, Sanders, Zheng, Péer and Gejman2009; Stefansson et al., Reference Stefansson, Ophoff, Steinberg, Andreassen, Cichon, Rujescu and Collier2009). In the subsequent decade, efforts by the PGC have spearheaded much of the common variant discoveries in schizophrenia genetics. The first GWAS by the PGC identified significant associations in seven loci, five of which were novel and two of which had been previously implicated (Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Consortium, 2011). The major breakthrough for schizophrenia GWAS came from the second GWAS by the PGC by identifying 128 independent associations in 108 loci, 83 of which had not been reported previously (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2014). A subsequent meta-analysis identified 179 independent associations mapping to 145 independent loci, 52 of which were not previously reported by the PGC (Pardiñas et al., Reference Pardiñas, Holmans, Pocklington, Escott-Price, Ripke, Carrera and Walters2018). Utilizing GWAS fine mapping, chromosome conformation capture, and summary-data-based Mendelian randomisation analyses, potential causal genes were mapped to 33 loci (Pardiñas et al., Reference Pardiñas, Holmans, Pocklington, Escott-Price, Ripke, Carrera and Walters2018). Among these genes that are potentially causally related to schizophrenia, SLC39A8 deficiency has also been associated with severe neurodevelopmental disorders supposed via impaired manganese transport and glycosylation. As oral galactose supplementation is a treatment option for complete normalization of glycosylation (Park et al., Reference Park, Hogrebe, Grüneberg, DuChesne, von der Heiden, Reunert and Marquardt2015), it emphasizes a therapeutic potential for schizophrenia. The largest GWAS to date is the third effort from the PGC, currently available as a pre-print, in 69 369 people with schizophrenia and 236 642 controls, identifying a total of 329 linkage disequilibrium-independent significant SNPs mapping to 270 distinct loci (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, Ripke, Walters, & O'Donovan, Reference Ripke, Walters and O'Donovan2020). Fine-mapping analyses refined these signals to 130 genes that are likely to explain these associations.

One of the most robust common variant associations with schizophrenia, among European populations, has been the 6p22.1 locus. This locus was first reported in 2009 in three independent studies as a genome-wide significant association (Purcell, Wray, Stone, Visscher, O'Donovan, & Sullivan, Reference Purcell, Wray, Stone, Visscher, O'Donovan, Sullivan and Moran2009; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Levinson, Duan, Sanders, Zheng, Péer and Gejman2009; Stefansson et al., Reference Stefansson, Ophoff, Steinberg, Andreassen, Cichon, Rujescu and Collier2009), and has been repeatedly confirmed since then in the major studies reported in Fig. 2. The association at this locus, in an extended region around the Major Histocompatibility Complex, is likely to reflect causal variants located in at least three independent regions, one of which involves alleles of complement component 4 (C4) (Sekar et al., Reference Sekar, Bialas, De Rivera, Davis, Hammond, Kamitaki and McCarroll2016). The associated alleles promote greater expression of C4A in the brain. This locus was also reported in studies in Chinese populations (Yue et al., Reference Yue, Wang, Sun, Tang, Liu, Zhang and Zhang2011; Li et al., Reference Li, Chen, Yu, He, Xu, Zhang and Shi2017), however, a subsequent meta-analysis of the largest East Asian schizophrenia GWAS (Lam et al., Reference Lam, Chen, Li, Martin, Bryois, Ma and Huang2019) did not replicate this finding.

Many genetic studies have demonstrated population-specific characteristics due to differences in underlying genetic architecture and environmental exposures, highlighting the importance of investigating trait/disease heterogeneity in population genetic studies. There have been GWAS studies reported in Indian (Periyasamy et al., Reference Periyasamy, John, Padmavati, Rajendren, Thirunavukkarasu, Gratten and Mowry2019), African American (Fiorica & Wheeler, Reference Fiorica and Wheeler2019) and Latin American (Bigdeli et al., Reference Bigdeli, Genovese, Georgakopoulos, Meyers, Peterson, Iyegbe and Pato2019) populations but, to date, large scale schizophrenia GWAS has primarily been investigated in people of European ancestry and more recently East Asian ancestries. The largest schizophrenia GWAS in individuals of East Asian ancestries reported 21 independent associations in 19 loci, which included the top three associations shared with the European studies, and an additional 14 associations compared to the previous study of Chinese ancestry (Lam et al., Reference Lam, Chen, Li, Martin, Bryois, Ma and Huang2019). The subsequent meta-analysis of East Asian and European ancestries reported 208 independent associations in 176 independent genetic loci, 53 of which were novel. These findings suggest that although the common genetic basis for schizophrenia is largely shared between populations, there are also likely to be population-specific risk variants driven by underlying differences in linkage disequilibrium and/or allele frequency.

Polygenic risk score (PRS) prediction of schizophrenia

PRSs have emerged as an informative tool for studying the effects of genetic liability and may potentially be a clinically useful application of GWAS results. PRS is a single measure of the cumulative effects of common variants associated with a disorder, with higher scores indicating higher genetic liability (Lewis & Vassos, Reference Lewis and Vassos2020). The variance explained varies depending on the GWAS p value threshold used for calculating the PRS (from all SNPs to only genome-wide significant SNPs); a p value threshold of <0.05 from currently powered GWAS explains the greatest amount of variance in schizophrenia case-control status (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2014; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium et al., Reference Ripke, Walters and O'Donovan2020). First demonstrated in 2009 (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Wray, Stone, Visscher, O'Donovan, Sullivan and Moran2009), PRS can currently explain around 7.7% of the variance in schizophrenia case-control status (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium et al., Reference Ripke, Walters and O'Donovan2020). However, the ability of PRS to explain schizophrenia case-control status is reduced in samples from a health care setting compared with the original GWAS research cohorts (Zheutlin et al., Reference Zheutlin, Dennis, Linnér, Moscati, Restrepo, Straub and Smoller2019). Although the ability of PRS to predict schizophrenia is currently insufficient for diagnostic purposes, there may be a greater promise for sampling individuals at the extreme ends of the PRS distribution. How schizophrenia PRS could be applied clinically remains unclear and in contrast to other common diseases that have benefited from PRS, such as coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes, there is currently no preventative strategy in place for schizophrenia (Lewis & Vassos, Reference Lewis and Vassos2020).

A key challenge in PRS analysis is the application across the major different ancestral populations. PRS derived from alleles discovered in GWAS of Europeans ancestries explain less variance when applied to African and Asian populations than in European ancestry samples, likely due to differences in allele frequencies and linkage disequilibrium structures (Curtis, Reference Curtis2018; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019). PRS prediction of schizophrenia computed from European ancestry populations has been reported to be only 45% as accurate in East Asians compared to European individuals, despite a broadly shared genetic aetiology (Lam et al., Reference Lam, Chen, Li, Martin, Bryois, Ma and Huang2019). The performance of PRS derived from a European ancestry GWAS applied to individuals with an African ancestry has been demonstrated to be particularly poor (Curtis, Reference Curtis2018; Vassos et al., Reference Vassos, Di Forti, Coleman, Iyegbe, Prata, Euesden and Breen2017). Given the vast majority of genetic studies are conducted in populations of European ancestry, greater diversity in GWAS must be prioritised to realise the potential of PRS (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019).

Dissecting the clinical heterogeneity of schizophrenia using PRS

PRS has been used to disentangle the clinical heterogeneity of schizophrenia by investigating the phenotypic markers of genetic liability, particularly in relation to treatment outcomes, symptom severity, and cognitive ability (Dennison, Legge, Pardiñas, & Walters, Reference Dennison, Legge, Pardiñas and Walters2020; Rees & Owen, Reference Rees and Owen2020). A higher PRS for schizophrenia has been associated with a more chronic illness course, indexed by the number and length of hospital admissions (Meier et al., Reference Meier, Agerbo, Maier, Pedersen, Lang, Grove and Mattheisen2016). Results from studies investigating an association between schizophrenia PRS and treatment-resistance to antipsychotics are conflicting, indicating that outcome specific PRSs are likely to be required (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Lang, Witt, Strohmaier, Rujescu, Cichon and Rietschel2015; Horsdal et al., Reference Horsdal, Meier, Wimberley, Agerbo, Gasse and MacCabe2017; Kowalec et al., Reference Kowalec, Lu, Sariaslan, Song, Ploner, Dalman and Sullivan2019; Legge et al., Reference Legge, Dennison, Pardiñas, Rees, Lynham, Hopkins and Walters2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Robinson, Yu, Gallego, Fleischhacker, Kahn and Lencz2019).

Schizophrenia PRS has been associated with negative and disorganised symptom dimensions in individuals with schizophrenia, although the reported variance explained is small (Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2018; Fanous et al., Reference Fanous, Zhou, Aggen, Bergen, Amdur and Duan2012; Jonas et al., Reference Jonas, Lencz, Li, Malhotra, Perlman, Fochtmann and Kotov2019). There is no evidence to suggest that schizophrenia PRS is associated with the severity of positive symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia, but it has been associated with the presence of psychotic symptoms in first-episode samples and bipolar disorder (Allardyce et al., Reference Allardyce, Leonenko, Hamshere, Pardiñas, Forty, Knott and Escott-Price2018; Ruderfer et al., Reference Ruderfer, Fanous, Ripke, McQuillin, Amdur, Gejman and Kendler2014). There has been conflicting findings from studies investigating the association between schizophrenia PRS and the cognitive deficits observed in individuals with schizophrenia (Dickinson et al., Reference Dickinson, Zaidman, Giangrande, Eisenberg, Gregory and Berman2020; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Pardiñas, Frizzati, Tansey, Lynham, Holmans and Walters2020).

A further area of interest has been the relationship between PRS and intermediate phenotypes relevant to schizophrenia such as neuroimaging measures. A higher schizophrenia PRS has been associated with lower connectivity in areas disrupted in individuals with schizophrenia (Cao, Zhou, & Cannon, Reference Cao, Zhou and Cannon2020). There does not currently appear to be any strong evidence for an association between PRS and brain structural changes relevant to schizophrenia (van der Merwe et al., Reference van der Merwe, Passchier, Mufford, Ramesar, Dalvie and Stein2019).

Shared common genetic heritability with other psychiatric disorders

Common genetic liability for schizophrenia has been robustly found to have pleiotropic effects on related psychiatric disorders (Fig. 3). Schizophrenia has significant genetic correlations with bipolar disorder (rg = 0.68), major depressive disorder (rg = 0.34), obsessive compulsive disorder (rg = 0.33), ADHD (rg = 0.22), anorexia nervosa (rg = 0.22), and autism spectrum disorder (rg = 0.21) (Brainstorm Consortium et al., Reference Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Walters, Bras and Murray2018). In addition, schizophrenia had a positive genetic correlation with neuroticism (rg = 0.19), negative correlations with subjective well-being (rg = −0.30), body mass index (rg = −0.10), and intelligence (rg = −0.20) (Brainstorm Consortium et al., Reference Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Walters, Bras and Murray2018). These results are also consistent in non-European populations (Lam et al., Reference Lam, Chen, Li, Martin, Bryois, Ma and Huang2019), and in a PRS analysis of a large real-world sample of patients from four US-based healthcare systems (Zheutlin et al., Reference Zheutlin, Dennis, Linnér, Moscati, Restrepo, Straub and Smoller2019). These findings indicate that a substantial proportion of the common genetic architecture among psychiatric disorders and cognition is shared and has implications for the validity of current clinical diagnostic boundaries. These findings are supported by the observation that schizophrenia is often comorbid with other psychiatric disorders, with the highest rates for substance use disorders (Regier et al., Reference Regier, Farmer, Rae, Locke, Keith, Judd and Goodwin1990) and mood disorders (Buckley, Miller, Lehrer, & Castle, Reference Buckley, Miller, Lehrer and Castle2009). Possible explanations for this pleiotropy include the presence of a general genetic psychopathology factor that increases the risk for multiple psychiatric disorders or that additional genetic and environmental factors influence the eventual clinical presentation (Dennison et al., Reference Dennison, Legge, Pardiñas and Walters2020).

Fig. 3. Genetic correlations (rg) of psychiatric disorders and related phenotypes with schizophrenia (Anttila et al., Reference Anttila, Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Walters, Bras and Murray2018). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

SNP-based heritability estimates

Current estimates place the SNP-based heritability, or the phenotypic variance due to genetic variation tagged by polymorphisms derived from array genotyping, at approximately 24% (Pardiñas et al., Reference Pardiñas, Holmans, Pocklington, Escott-Price, Ripke, Carrera and Walters2018; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium et al., Reference Ripke, Walters and O'Donovan2020). The disparity in heritability estimates from family studies and GWAS indicates there are susceptibility genes yet to be identified and has led to a search for the ‘missing’ heritability. There are several potential sources of missing heritability including common variants that current studies are not yet powered to detect, but also gene–environment interactions, epigenetic variation, and rare genetic variation.

Rare genetic variation

Rare variants are typically defined as those with a minor allele frequency <1% and include single nucleotide variants (SNVs), altering one or a small number of bases, and insertion-deletion variants, which can vary in size from those affecting single nucleotides to those classified as CNVs that affect thousands or millions of bases. CNV studies to date are typically based on the same genotyping platforms used to conduct GWAS, while other rare variants have largely been studied using whole exome sequencing (WES). Whole genome sequencing can capture both types of variants as well as other forms of structural changes, but to date, such studies in schizophrenia are small in scale. Rare variant studies are poised to be highly informative by pinpointing causal genes and understanding molecular and cellular aspects of the disease process (Sullivan & Geschwind, Reference Sullivan and Geschwind2019). Including the most recent exome sequencing effort reported in pre-peer reviewed format, 10 genes have been implicated through exome sequencing studies to date and eight rare CNVs have been associated with schizophrenia.

SNVs and small insertion deletion (indel) variants

The current sample sizes included in WES cohorts are insufficiently powered to detect significant associations at the single variant level. However, an alternative statistical strategy exists, whereby variants are pooled together at the gene or genome level and then the burden of those variants can be compared between cases and controls. A WES study demonstrated an enrichment of damaging ultra-rare variants in 2536 schizophrenia cases, compared with 2543 controls (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Moran, Fromer, Ruderfer, Solovieff, Roussos and Sklar2014). Similar findings were reported from an extension of the same Swedish cohort of 12 332 individuals (4946 schizophrenia cases, 6242 controls) analysed along with 45 376 whole exomes from the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), whereby an excess burden of disruptive and damaging (as predicted by bioinformatics) ultra-rare variants was found in cases [odds ratio = 1.07, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.05–1.09] (Genovese et al., Reference Genovese, Fromer, Stahl, Ruderfer, Chambert, Landen and McCarroll2016). However, no individual gene was found to have a significant excess of damaging ultra-rare variants, demonstrating the highly polygenic nature of schizophrenia.

Another WES study identified a significant association between SETD1A loss of function (LoF: variants predicted to result in the loss of protein-coding function) variants and schizophrenia by combining a whole-exome case-control sequencing study of 4264 schizophrenia cases, and 9343 controls, with de novo mutation analysis in 1077 parent-proband trios (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Kurki, Curtis, Purcell, Crooks, McRae and Barrett2016). A subsequent follow-up study found the burden of LoF variants was enriched in LoF intolerant gene sets in schizophrenia cases, compared to controls (odds ratio = 1.24, 95% CI 1.16–1.31), although no individual gene was implicated (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Walters, Johnstone, Curtis, Suvisaari, Torniainen and Barrett2017). Similarly, the recent population-specific WES studies of South African (Gulsuner et al., Reference Gulsuner, Stein, Susser, Sibeko, Pretorius, Walsh and McClellan2020) and Taiwanese (Howrigan et al., Reference Howrigan, Rose, Samocha, Fromer, Cerrato, Chen and Neale2020) ancestry did not identify any implicated gene but found the burden of LoF variants to be enriched in highly brain-expressed and evolutionarily constrained genes. Currently, the largest rare exome sequencing effort is from the Schizophrenia Exome Sequencing Meta-Analysis (SCHEMA) Consortium, which pooled data from 24 248 schizophrenia cases and 97 322 controls. As reported in pre-peer reviewed format, 10 genes (including SETD1A), reach genome wide significance for an excess of ultra-rare variants predicted to be damaging in cases compared to controls (p < 2 × 10−6) (Singh, Neale, & Daly, Reference Singh, Neale and Daly2020), and a further 22 reached suggestive levels of significance as defined by a false discovery rate of 0.05.

De novo variants (DNVs)

DNVs are variants that are present in offspring as a result of a new mutation event and are therefore absent in the parents. Schizophrenia is associated with a reduction in reproductive fecundity, leading to the hypothesis that DNVs with large effect sizes play a role in the genetic aetiology. In a recent WES study of 3444 schizophrenia parent-proband trios, LoF DNVs were found to be significantly enriched in LoF intolerant genes, but no gene individually achieved exome wide significance for the enrichment of LoF DNVs (Rees et al., Reference Rees, Han, Morgan, Carrera, Escott-Price, Pocklington and Owen2020). However, the burden of DNVs was significantly higher in genes previously associated with neurodevelopmental disorders, among which SLC6A1 encoding a gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transporter, was significantly enriched with missense variants. In gene-set analysis, DNVs were enriched in evolutionary constrained genes and in those implicated in multiple neurodevelopmental disorders. A separate study also noted that the DNV burden in schizophrenia is smaller as compared to early-onset neurodevelopmental disorders (Howrigan et al., Reference Howrigan, Rose, Samocha, Fromer, Cerrato, Chen and Neale2020).

Copy number variations (CNVs)

CNVs are either duplications or deletions, ranging from 50 base pairs to megabases in the genome and can span a whole gene or multiple genes in a region. CNVs have been consistently implicated in the aetiology of schizophrenia, with the first associated CNV for schizophrenia being a large deletion on chromosome 22q11.2, which confers a 20-fold increased risk, with approximately 25% of carriers develop schizophrenia. The largest CNV study to date in 21 094 cases and 20 227 controls found eight CNVs (six deletions and two duplications) to be significantly associated with schizophrenia (Fig. 1) (CNV and Schizophrenia Working Groups of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2017). These eight loci collectively explain 0.85% of the variance in liability to schizophrenia, with 1.4% of the cases carrying these risk CNVs. This is consistent with other studies demonstrating large effect sizes of CNVs, even though the absolute number of cases with CNVs is small (Rees et al., Reference Rees, Walters, Georgieva, Isles, Chambert, Richards and Kirov2014). Studies have shown that CNV penetrance (i.e. the proportion of CNV carriers demonstrating the phenotype of interest) in schizophrenia is lower compared with other neurodevelopmental disorders (Kirov et al., Reference Kirov, Rees, Walters, Escott-Price, Georgieva, Richards and Owen2014; Vassos et al., Reference Vassos, Collier, Holden, Patch, Rujescu, St Clair and Lewis2010). The penetrance of CNVs in schizophrenia seems to be additionally influenced by the burden of common risk alleles (Tansey et al., Reference Tansey, Rees, Linden, Ripke, Chambert, Moran and O'Donovan2016), with evidence supporting an additive joint effect between the two classes of risk variants (Bergen et al., Reference Bergen, Ploner, Howrigan, O'Donovan, Smoller, Sullivan and Kendler2019).

Functional annotation of genetic variants

The polygenic nature of schizophrenia imposes a challenge to understand how, where, and when genetic variation acts to increase the vulnerability of developing the disorder. Following up on the findings from genome-wide association approaches, the aim is to then gain biological insights by identifying genes, tissues, cells, and biological pathways associated with schizophrenia.

Enrichment of gene-sets

Gene-set analysis investigates whether sets of genes, grouped by biological pathway or expression in particular tissues, are enriched for variants associated with schizophrenia. Consistent with the hypothesis that schizophrenia is primarily a disorder of neuronal dysfunction, genes highly expressed in the brain, mainly in cortical inhibitory interneurons and excitatory neurons from cerebral cortex and hippocampus, are strongly enriched for SNPs associated with schizophrenia (Pardiñas et al., Reference Pardiñas, Holmans, Pocklington, Escott-Price, Ripke, Carrera and Walters2018; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium et al., Reference Ripke, Walters and O'Donovan2020). Other notable gene-set findings included an association within a target gene of antipsychotic drugs (DRD2), genes involved in glutamatergic neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity (e.g. GRM3, GRIN2A, SRR, GRIA1) and additional genes encoding voltage-gated calcium channel subunits (CACNA1C, CACNB2 and CACNA1I) (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2014).

Likewise, analyses of gene ontology classifications for schizophrenia have demonstrated enrichment in histone methylation and synaptic pathways, in particular, postsynaptic proteins and structures have been enriched for all classes of risk variants (Kirov et al., Reference Kirov, Pocklington, Holmans, Ivanov, Ikeda, Ruderfer and Owen2012; Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium et al., Reference Ripke, Walters and O'Donovan2020; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Neale and Daly2020). Notably, as the sample sizes have increased in genetic studies, enrichment analyses have shown convergence of rare and common variants findings, pointing to concordant genes (e.g. GRIN2A, SP4, STAG1, and FAM120A) and pathways, which strongly supports their relevance in schizophrenia.

Transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS)

TWAS use expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs – variants that affect expression) of genes in a specific tissue to predict the expression of that gene. Upon merging this information with GWAS summary statistics, we can infer which genes might be causally related to schizophrenia and whether they are up or downregulated. A TWAS using genetic data from the second PGC GWAS and expression data from brain, blood, and adipose tissues identified 157 genes to be associated with schizophrenia, with 42 associated with chromatin organization, highlighting that regions responsible for gene expression regulation can be potential targets (Gusev et al., Reference Gusev, Mancuso, Won, Kousi, Finucane, Reshef and Price2018). This was subsequently followed by another study reporting 107 genes, of which 11 were also differentially expressed and in the same direction as found previously in schizophrenia brain samples (Gandal et al., Reference Gandal, Zhang, Hadjimichael, Walker, Chen, Liu and Geschwind2018). A more recent TWAS evaluated 5301 genes with cis-heritable expression (variance explained by SNPs close to the gene) in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and identified 89 genic associations, 20 of which were novel (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Medway, Pain, Pardiñas, Rees, Escott-Price and O'Donovan2020).

Transcriptomic and single-cell studies

Although TWAS are able to indicate possible causal genes from GWAS results, TWAS cannot directly extract time-specific information of disease nor which kind of cell type is involved. As an initial step to rectify this gap, the Common Mind Consortium generated transcriptomic data from dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (258 schizophrenia cases, 279 controls) and intersected with 142 GWAS associations, to demonstrate an overlap of 20 variants potentially influencing gene expression of one or more genes (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Warrell, Won, Shi, Navarro and Gerstein2018).

Recently, single cell RNAseq data have offered a new interpretation of GWAS results. For schizophrenia, PsychENCODE-generated single cell RNAseq data identified spatiotemporal loci (Li et al., Reference Li, Santpere, Imamura Kawasawa, Evgrafov, Gulden, Pochareddy and Sestan2018) and mapped the associated genomic loci to pyramidal cells, medium spiny neurons, and interneurons in adult cortical cells (Skene et al., Reference Skene, Bryois, Bakken, Breen, Crowley, Gaspar and Hjerling-Leffler2018) and to neural progenitors (Li et al., Reference Li, Santpere, Imamura Kawasawa, Evgrafov, Gulden, Pochareddy and Sestan2018), oligodendrocyte precursors and fetal microglia (Polioudakis et al., Reference Polioudakis, de la Torre-Ubieta, Langerman, Elkins, Shi, Stein and Geschwind2019).

Future perspectives and increasing diversity

In the next few years, we should expect that larger sample size GWAS and rare variant studies will identify more genes and refine the biological processes implicated in schizophrenia. Similarly, efforts to improve functional annotations provided by newer iterations of consortia such as PsychENCODE, GTEx, CommonMind Consortium and others will aid further interpretation of GWAS results. It is hoped that these insights could contribute to drug discovery and personalised medicine efforts. Future research is also likely to focus on investigating how the different elements of genetic risk combine and how genetic risk interacts with environmental factors to ultimately cause schizophrenia.

As mentioned previously, it is of paramount importance to improve the diversity of schizophrenia genetic studies, by including non-European populations. By 2019, 79% of all GWAS samples (including non-schizophrenia studies) are from individuals of European descent (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019). For schizophrenia, the latest published GWAS pre-print included ~20% non-European samples, the majority of which were from East Asia (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium et al., Reference Ripke, Walters and O'Donovan2020). Increasing genetic diversity will ensure emergent clinical applications are applicable to all human populations, and at the same time, will increase the power to identify genetic associations and aid fine mapping (Li & Keating, Reference Li and Keating2014). As new ongoing consortia and biobanks are established, it is essential that ancestry disparities are addressed.

Conclusions

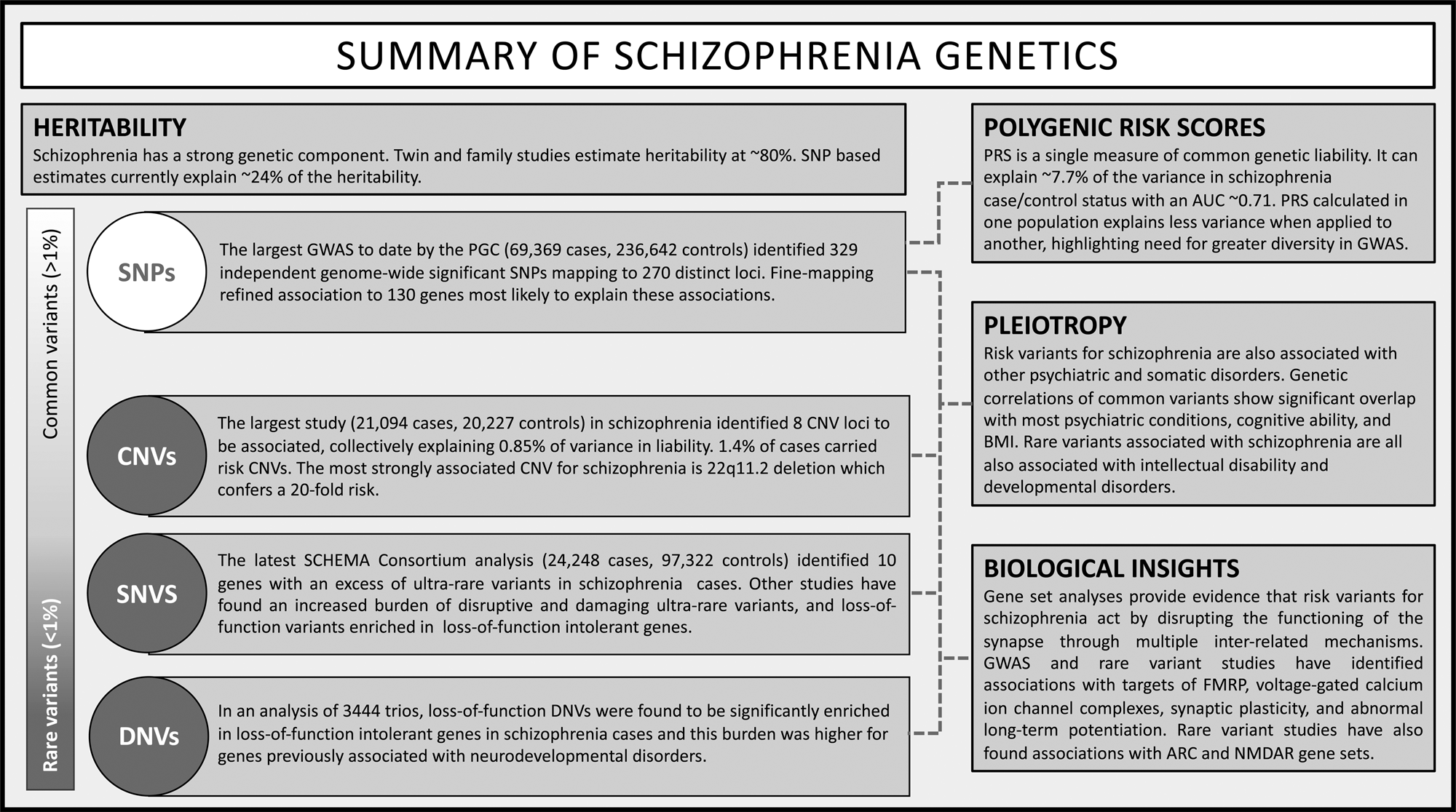

In the last two decades, the sample size for genetic studies of schizophrenia has increased from hundreds to hundreds of thousands of individuals, resulting in the identification of >300 common variants, 10 genes with a burden of rare coding variants, and at least 8 CNVs (Fig. 4). Genetic studies of schizophrenia provided the first compelling evidence of the value of GWAS in investigating common genetic risk for psychiatric disorders, which has led to an expansion of sample sizes and subsequently the identification of many genetic variants for other psychiatric disorders (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, 2014). Moreover, GWAS demonstrated the polygenic nature of psychiatric disorders and how hundreds or thousands of variants contribute to liability to schizophrenia. Rare variant studies in schizophrenia have also made important achievements, including identification of overlap of implicated genes and gene sets with other neurodevelopmental disorders. This pleiotropy further adds to the existing complex picture emerging out of these studies (Sullivan & Geschwind, Reference Sullivan and Geschwind2019).

Fig. 4. Overview of schizophrenia genetic findings.

For the coming years, we should expect not only an increase in the sample sizes but also an increase in diversity of genetic studies, which should identify new regions, improve fine mapping and increase our understanding of the biology and mechanisms of schizophrenia. Likewise, as sequencing prices decrease, larger whole genome sequencing studies should identify other rare variants that play a role in the disease. Now that many genes have been implicated with schizophrenia, functional studies will be critical to better understand how and when schizophrenia vulnerability acts during the neurodevelopment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professors Bryan Mowry, Sintia Belangero, Michael C. O'Donovan and James T. R. Walters for providing comments on this review article. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. KK received funding from the University of Manitoba. SL is supported by Medical Research Council Centre (MR/L010305/1) and Program (G0800509) grants to Cardiff University. MLS is supported by CAPES.

Conflict of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest pertaining to this review.