The next 2 years will see radical changes to the way medical training is delivered. First, the old apprenticeship and time served model will no longer be applicable. Second, from August 2004 the European Work Time Directive (EWTD) applies to trainees in the same way that it applies to all other grades (European Union, 1993, 2000). August 2005 will bring the first full intake into foundation programmes and will see the implementation of Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) (Department of Health, 2003). Further in 2005, the General Medical Council's (GMC's) new requirements for revalidation will come into force (GMC, 2003).

In order to begin meeting the complex problems linked with these changes, the Royal College of Psychiatrists has developed higher specialist competencies (currently on the College website for discussion), and will begin to address basic specialist competencies. Assessment forms a core component of this. The College examination as it currently exists may need radical reevaluation to meet these changes. In response to this, the Collegiate Trainees’ Committee (CTC) requested a document be produced to facilitate discussion within the Committee and the wider College about changing training needs. This article summarises the main areas of that document.

The current system

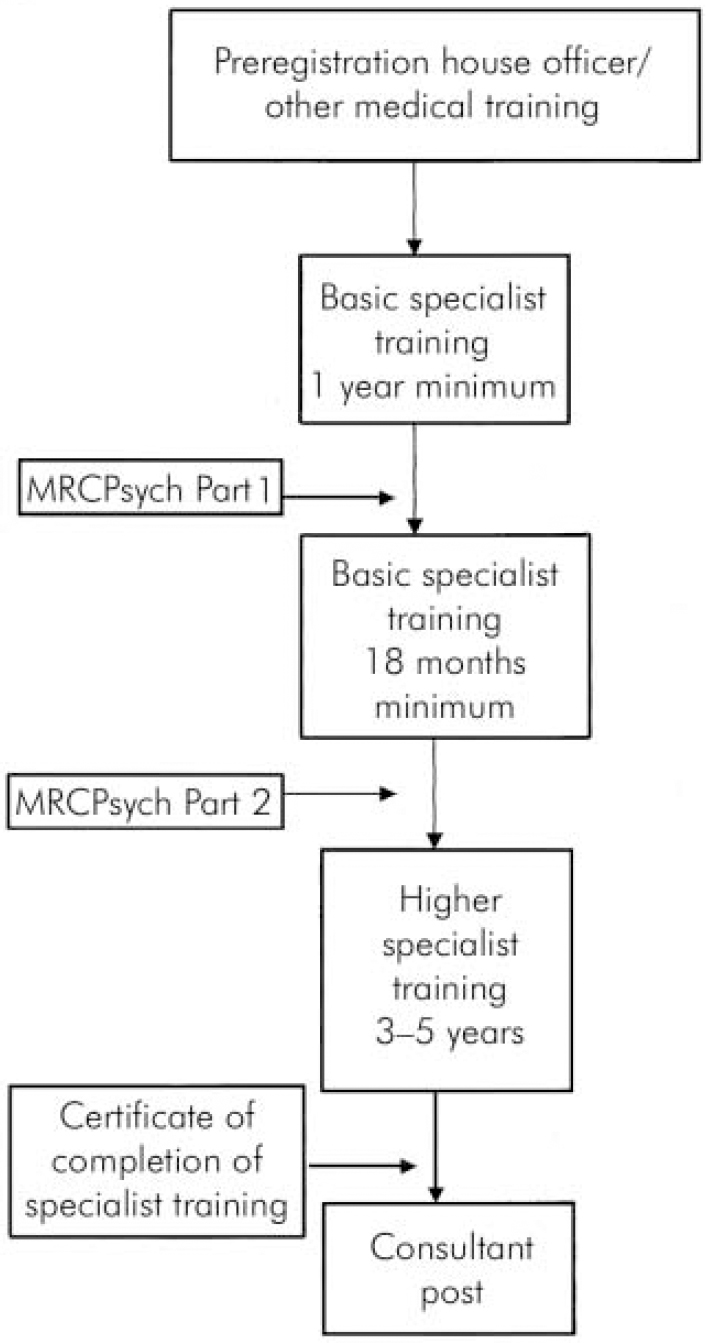

Figure 1 summarises the structure of medical training currently seen in psychiatry. The model is based on an experiential, apprenticeship model, with summative assessment of competency being the MRCPsych examination and the Record of In-Training Assessment (RITA) process. Currently there is no time limit to progression through the basic specialist grade; however, higher specialist training (HST) is limited to between 3 and 5 years. Progression is made by the adequate acquisition of skills leading to an eventual certificate of completion of specialist training (CCST).

Fig. 1. Current training structure in psychiatry.

The European Work Time Directive (Table 1)

The EWTD is a piece of health and safety legislation originally formulated in 1993 (European Union, 1993). It came into force in 1998 for all doctors with the exception of trainees. A revision statement later included trainees, which came into force in August 2004. The hours are limited to 56 initially with full reduction to 48 by 2009 (European Union, 2000).

Table 1. European Work Time Directive implementation timetable

| Maximum duty/actual work August 2004 | Maximum duty/actual hrs August 2007 | Maximum duty/actual hrs August 2009 | Minimum period off duty | Rest | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident | 58/56 | 56/56 | 48/48 | 24 h/7 days or 48 h/14 days | 11 h continuous in each 24 h and new deal regulations |

| Non-resident | 72/56 | 72/56 | 72/48 | 24 h/7 days or 48 h/14 days |

Associated European Court judgements (SiMAP and Jaeger; European Court of Justice, 1998, 2002) have introduced further restrictions. From August 2004 all time spent at work counted as work, in contradiction to the rest and work requirements of the new deal (Department of Health, 1998). Further, the Jaeger judgement specified that any compensatory rest must be taken immediately after a period of work. This has made derogations from the directive with regard to rest difficult to create.

These changes have meant that junior doctors are not available at work to the same extent as before. Thus, in the future, the process of gaining experience and acquiring knowledge will not be possible from experiential learning alone. Wider consideration of alternative methods of educational provision will need to be instigated. The developing use of online learning and the provision of modular learning are probable avenues to be explored.

Modernising Medical Careers

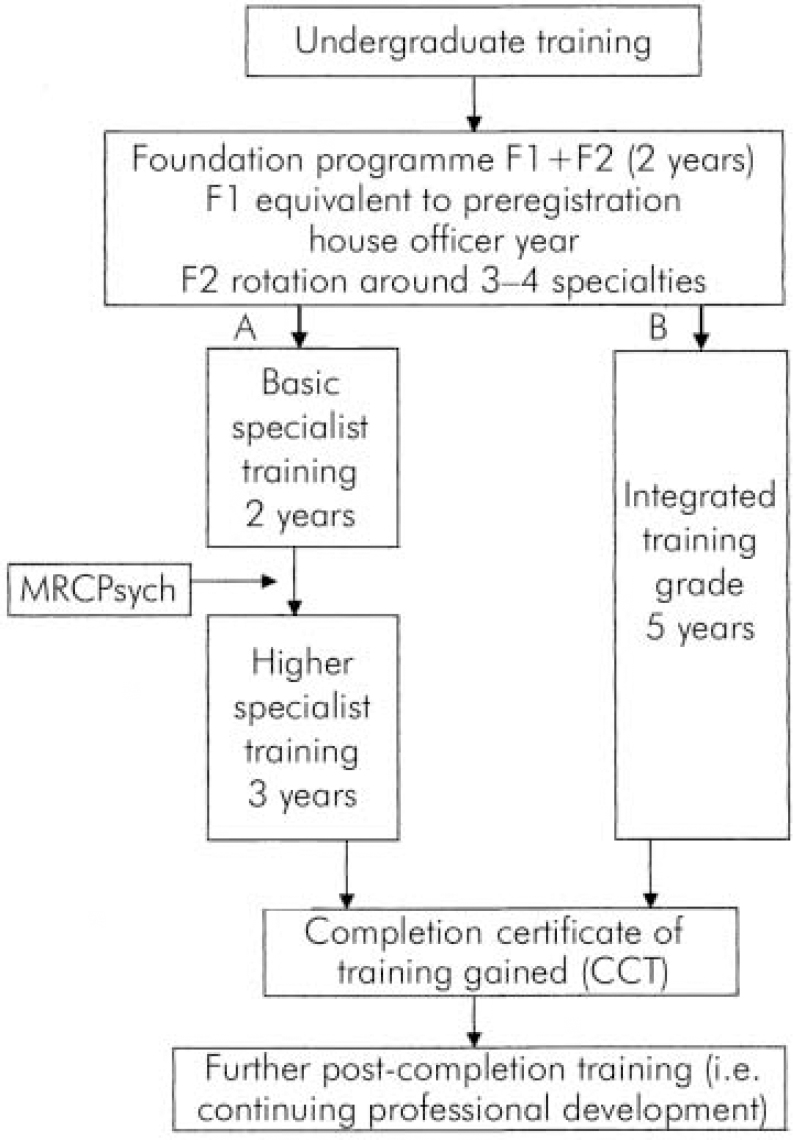

Modernising Medical Careers (Department of Health, 2003) has defined the changes to medical training that originally were discussed in Unfinished Business, Proposals for Reform of the SHO Grade (Department of Health, 2002a ). Figure 2 contrasts the two different models proposed. MMC introduces the foundation programme, comprising 2 years. The first year is essentially the same as the current preregistration house officer year. On completion of this year, full registration would be gained before entry into the second foundation year. This would allow the trainees to move between three or four posts from eight specialties such as general practice, accident and emergency, paediatrics and psychiatry.

Fig. 2. Modernising Medical Careers: proposed models of training.

Following this point the models diverge. The first model is consistent with that which currently exists in psychiatry with a reduction in time spent in basic specialist training (BST) (Model A). The second shows an integrated training structure (Model B), with trainees being allocated training numbers at the beginning of training, rather than on HST. Current staff and associate specialist doctors will also be encouraged to follow this route. At the end of the training a completion certificate of training is obtained (CCT). Currently, the level of competence that will be required for a CCT is unclear. Further, there is no clear direction for those who drop out of training for whatever reason.

With regards to Model B, there is no clear direction as to the role of the examination or the point at which further specialisation will be chosen. This has implications for the smaller psychiatric specialties. The document also alludes to post-CCT education and training. It is implied that specialism can and should be attained following CCT.

Core competencies

Core competencies for HST have been produced by the Royal College of Psychiatrists over the past 3 years. The process involved the current and previous Deans, Head of Postgraduate Education, the then chair of CTC, and the various college faculties. Currently, this is in a consultation phase on the College website prior to final versions being approved by the Court of Electors.

Each trainee will have to fulfil the general, as well as their specialty, competencies. The document acts as a guide by suggesting appropriate methods of learning and assessment. It does not try to be too directive thus allowing flexibility in different situations. The method by which the competency is assessed and attained will come down to interactions between the trainee, their educational supervisor, their programme directors and the RITA process. This process will have to be extended to BST in the near future.

Different methods of assessment are appropriate to different points of training. For example, objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) and multiple choice question (MCQ) parts of the examination are appropriate for testing a wide range of skills and knowledge, respectively, without going into great depth. Higher training requires the ability to test both competence and performance. Therefore, alternative, more appropriate assessment measures are required. There is an evidence base to suggest that using in-training assessment, chart-stimulated recall, critical incident reviews and other such methods as part of an ongoing process, combined with a more rigorous ongoing RITA process, would satisfy the requirements to define competency at the HST level.

Postgraduate Medical Education Training Board and revalidation

The Postgraduate Medical Education Training Board (PMETB) has evolved to take over the regulation of postgraduate medical education from the Specialty Training Authority (STA) (Department of Health, 2002b). It comprises a main board, which is subdivided into two further boards, one for training and the other for assessment. The assessment and training boards have been in existence for over a year. They have been offering guidance to the medical Royal Colleges as to what will be expected of them. The main board was appointed in late 2003 and has only just begun to define its role.

There is also the new requirement by the GMC for all doctors to be able to show evidence of ongoing appraisal for the purposes of revalidation. This is due to start in 2005. Recent clarification has shown that for those trainees participating in the RITA process this will suffice. There will be a need to extend this process to all doctors in training (GMC, 2004).

Discussion

The above summary highlights that medical training will have to change. The interpretation of these changes will affect whether or not those completing training in the future will be of the same standard as those completing training now. Time will be restricted. Instead of 7-8 years (on average) for post-completion of preregistration house officer posts, the time spent in training will be 5 years. Also, the actual time spent at work when seniors are also available will decline.

To remedy this, the process of education and the definitions of what is required are essential. The methods by which education can be delivered have yet to be decided. Traditional methods are unlikely to be appropriate and the Royal College of Psychiatrists will need to expand beyond those methods it currently employs. Proposed electronic education via the internet or distance learning may be necessary. Also, the educational supervisor will have to play a greater role in the actual education, training and assessment. The methods that exist are continuously being evaluated. In the past few years major changes have occurred to the MRCPsych examination. Further changes to this will have to be made. The nature and timing of these changes will also have to be defined. Any assessment must achieve expectations. Validation of competence prior to CCT must be part of an ongoing process. It is essential that deficiencies in competencies are identified prior to completion of CCT. With shorter training it becomes increasingly vital that under-achievement is identified and rectified as part of an ongoing process of training. This will be best done via an enhanced RITA process.

Modernising Medical Careers has meant that the College will need to define where training is delivered, when it is assessed and at what point specialisation will occur. Without this there are many possible dangers in recruitment to the smaller specialties. Generalist training will not only lead to a potential reduction in the number of people going into subspecialties, but also devalues the level of knowledge and skill required to practise general psychiatry.

There is an acceptance among trainees that changes have to happen. What they would rather see is continuous ongoing evaluation as stated above, with robust mechanisms to ensure objectives are achieved. To this end, there is a desire for trainees to participate in this discussion. The views of current trainees, who will become the trainers of the future, must play a part in shaping the future of medical education.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank Gareth Holsgrove, Head of Postgraduate Education, Royal College of Psychiatrists, Professor S. Hollins and members of the CTC for advising on this article.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.